OPERATIONAL ART AND THE CAMPAIGN OF 1813

CHRONOLOGY

| Dec 30, 1812 | Convention of Taurrogen, Yorck neutralized his Prussian Corps. |

| Jan 30, 1813 | Austria secretly declared neutrality. |

| Mar 1, 1813 | Treaty of Kalisch: Prussians joined the Russians to create the Sixth Coalition. |

| May 2 | Napoleon won battle of Lützen/Gross-Görschen. |

| May 20–21 | Napoleon won battle of Bautzen. |

| Jun 4 | Napoleon agreed to cease-fire at Pleischwitz. |

| Jun 21 | Wellington defeated Joseph Bonaparte at Vitoria. |

| Jul 9–12 | Allies met at Trachenberg. |

| Jul 25–30 | Wellington defeated Soult’s counteroffensive in the Pyrenees. |

| Aug 13 | Austria declared war on France. |

| Aug 15 | Austria, Prussia, Russia, and Sweden resumed active operations against Napoleon. |

| Aug 23 | Marshal Oudinot was defeated at Grossbeeren. |

| Aug 26–27 | Napoleon defeated Allies at Dresden. |

| Aug 26 | Blücher defeated Marshal Macdonald at the Katzbach. |

| Aug 29–30 | Vandamme’s French corps annihilated at Kulm. |

| Sep 6 | Bülow defeated Marshal Ney at Dennewitz. |

| Oct 15–19 | Napoleon was defeated at Leipzig. |

| Oct 30 | Napoleon defeated Bavarians at Hanau and retreated into France. |

On December 30, 1812, General Hans David Yorck, commander of the Prussian component of Marshal MacDonald’s corps completed extensive negotiations with a Prussian in Russian service—Carl von Clausewitz. Yorck agreed to neutralize the 17,000 Prussian troops under his command for a period of two months. With this agreement, signed at Taurrogen in Lithuania (not far from Tilsit), Clausewitz effectively inaugurated the Sixth Coalition against the Empire of France (see map 24). The Convention of Taurrogen served as the catalyst the Russian Tsar Alexander had hoped for to continue his holy crusade against Napoleon, who had despoiled his nation the previous year.1 The outgrowth of this event was the subsequent rebellion of Prussia against Napoleon in early 1813. For the first time since 1807, two major continental powers, Prussia and Russia, were united in arms against Napoleon’s Empire. In the spring operations that followed, Napoleon emerged tactically victorious despite the military improvements of his opponents, the weaknesses of the new Grande Armée, the wavering of Napoleon’s allies in the Confederation of the Rhine, and the unexpected (to Napoleon) neutrality of Austria.2

The campaign by the Sixth Coalition against Napoleon in 1813 in Germany offers a particularly lucrative case study by virtue of its sheer scope of operations. The coalition’s operations in Germany were only one of many theaters with a strategic bearing on the situation; but the liberation of Germany was by far the most important strategic goal when compared to the liberation of Spain and Italy (the latter still not completely “liberated” at the time of Napoleon’s abdication in 1814).3 It was in Germany in 1813 that we see the employment of the mass coalition-conscript armies by the Allies—Prussian, Austrian, and even Russian. We have seen the improvements effected by all the nations that comprised that coalition save one—Prussia. It is to that nation that we now turn before continuing to examine operational art in 1813.

PRUSSIAN REFORMS

Like the Russians and Austrians, the Prussians implemented reforms in response to the threat posed by Napoleon. The course of these reforms was by no means a smooth one for Prussia—in the interim Napoleon reduced her to a second-rank power by constraining the size of her army to approximately 42,000 troops total.4 The Prussians, however, became a true nation in arms in the manner of France and came up with innovations of their own, perhaps the greatest being their general staff.5 Of all the opponents of France the Prussians were probably the ones who most completely and competently absorbed the new ways of warfare.6 The visceral incorporation of these methods had already begun prior to the Prussian catastrophe of 1806, which was to rapidly accelerate an already established reform movement within the Prussian army. Its genesis was, as with the Austrians, the defeats of the early Revolutionary Wars. In 1795, after Prussia withdrew from the First Coalition, the War Ministry in Berlin established a commission to “investigate and ameliorate the defects that had appeared” during the recent conflict with France. Aside from an increase in light infantry (termed fusiliers or jaeger by the Prussians) nothing of real importance was accomplished.7 Two events then occurred that helped the Prussian reform movement gain momentum: a new king interested in military affairs was crowned in 1797 (Frederick William III), and Gerhard von Scharnhorst was accepted into the Prussian army for service as a quartermaster general (chief of staff).8

According to Scharnhorst’s protégé, Baron Karl von Müffling, “Scharnhorst had made Napoleon’s mode of warfare, and the means of resisting him, the chief object of his study, and endeavored accordingly to prepare young men for the war…with this dangerous opponent.”9 The catastrophe of 1806–1807 provided the reformers, led by Scharnhorst, with the opportunity to completely revamp the Prussian army. Clausewitz summarized the gist of Scharnhorst’s reforms:

These recommendations were adopted along with a purge of nearly 5,000 officers.11 Finally, Scharnhorst implemented a policy of pairing battle tested commanders such as Yorck and Blücher with professionally trained staffs headed by himself (and after his death Gneisenau) and the cream of the Kriegsakademie (war academy)—Hermann von Boyen, Müffling, and Clausewitz. This resulted in an operational command system second to none by 1813.12

Scharnhorst’s response to Napoleon’s limit on the size of the Prussian army involved an ingenious system of training that created a trained reserve—the Krümpersystem. During every training cycle, trained cadre were released (but kept track of) and new recruits called up to replace them. Gneisenau estimates that after three years as many as 150,000 men had been trained in this way.13 However, only some 16,000 of these would be young enough for recall in 1813. The beauty of the system was that the ineligible trained men could serve in the landwehr (trained militia) that the reformers planned for in a national emergency. Additionally, the 16,000 trained reserves that were called up to service became cadres for other regiments and this resulted in an overall increase of around 40,000 additional trained troops to the Prussian army in early 1813.14

The published tactical doctrine for this army, finalized in the 1812 Reglement, earned the praise of Frederick Engels as “the best in the world.”15 A multiauthored document developed by Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, among others, its final form was due principally to an officer often regarded as a reactionary, Hans David Yorck. Napoleon’s invasion of Russia served as the final element that honed the Prussians for the campaign of 1813. When Napoleon demanded that Prussia provide an auxiliary corps to support his invasion, many of its best officers, including Clausewitz, left the Prussian service for the Russian and thus gained valuable experience in fighting the French. Gneisenau reported that the efforts to rebuild the Prussian army via the Krümpersystem were in effect “paralysed [sic].” Nevertheless the final verdict of Gneisenau was that the loss of 10,000 trained men in Russia was “outweighed by the military experience gained.”16

In summary, the Prussian army was now a trained all-arms “army of the people,” albeit small, but with an excellent command system. Its “brigades” were roughly equivalent to the French divisions in size and superbly trained with a thoroughly up-to-date tactical doctrine. In turn these brigades were amalgamated into combined arms corps, each with an operational staff supporting the commanding general with separate artillery and cavalry reserves at the corps level. This army, thanks to British supplies would soon be excellently equipped in 1813 and was capable of expanding from about 30,000 veterans in January of 1813 to some 80,000 trained troops by the time of the spring campaign.17

OPERATIONAL ART IN THE SPRING 1813 CAMPAIGN

Yorck’s defection at Taurrogen had far-reaching effects. Because he had neutralized his corps in Prussian Lithuania, Wittgenstein’s leading elements crossed the Niemen River, effectively invading the Napoleonic domain. Shortly thereafter Yorck abandoned his neutrality and joined Wittgenstein, leaving Clausewitz among others to organize the landwehr and landsturm as well as replacement conscripts and volunteers for the regular regiments.18 Subsequent operations can be divided into two distinct phases. The first phase began with Yorck’s defection at Taurrogen and ended approximately at the time that Napoleon rejoined his reconstituted Grande Armée (named the Army of the Main) on April 25 at Erfurt.19 The second phase began with Napoleon’s active campaigning and encompasses the battles of Lützen and Bautzen, terminating with the signing of a cease-fire at Pleischwitz on June 4. This cease-fire was soon followed by a formal armistice.

Overlapping these two phases were other military operations that had a bearing on the operational situation. The first of these encompassed the masking and sieges of the fortified cities (e.g., Danzig) that Napoleon left along the Allied lines of communication. Other operations consisted of Allied attacks against Napoleon’s lines of communications using partisans, friekorps, Cossacks, regular units, and the various combinations of all of these—in Soviet terms deep operations. U.S. Army doctrine from the 1990s defined deep operations as those that “engage enemy forces throughout the depth of the battle area and achieve decisive results rapidly.”20 Because of the vast geographic extent of these operations—one might call them distributed—their bearing on the campaign will also be examined.

Wittgenstein’s invasion after Taurrogen completely changed the strategic fabric of the Russia’s war against Napoleon. Until this point the war for the Russians was a defensive one. Its strategic aim was, in Clausewitzian terms, negative—expel the invaders from the sacred soil of Holy Russia. This was where the campaign would have reasonably ended. Let us first examine the situation as it appeared immediately prior to Taurrogen and then after to gain the context of the strategic and operational decisions that followed. For the Russians the year of 1812 had been more than just a French military catastrophe. One account estimates that the Russians had lost at least a quarter of a million soldiers killed alone. Because of these losses the Russians had just over 150,000 men left, including reserves and replacements, with only about 62,000, including Cossacks, available to carry the fight into Napoleonic domains. Additionally, Russia’s military commander Prince Kutuzov, whose prestige was now immense, opposed a continuation of the pursuit of the French beyond Russia’s borders (although it included the Grand Duchy of Warsaw). Russia had historically experienced great difficulties in projecting and supplying forces beyond its borders. With manpower “melting away,” the Tsar ordered another massive round of conscription on December 12, 1812. To understand this act we must look at the resources of the French. Alexander’s conscription was a precaution intended to provide additional resources to fight a defensive war. As contemporary observers made clear, a negotiated settlement was forecast, but what had Napoleon done? He had returned to France to raise another army. The Russians knew this and wanted to be able to negotiate from a position of strength. Even Gneisenau freely admits in his account that the Russians were not physically capable of maintaining themselves beyond the line of the Vistula River (see map 24).21

Napoleon had good reason to believe that he might return to Poland instead of several hundred miles further west. He could theoretically field more troops than the Russians, some 190,000. Napoleon’s instructions to Murat, in command once the Emperor departed after crossing the Beresina, were to defend along the Niemen if possible.22 However, the balance of troops in this total came from the Prussian and Austrian contingents—Murat’s strength derived from the corps of two former enemies. If we subtract Yorck’s 17,000 and Schwarzenberg’s 25,000 troops from Napoleon’s forces, the French Imperial forces for defense totaled 148,000, including those in garrisons. Napoleon, enraged by Yorck’s action and underestimating the duplicity of the Austrians, further compounded his shortage of veteran manpower by directing Murat and his successor Prince Eugene to leave major fortresses garrisoned as the French gave up ground in their retreat west.23 Instead of gaining power as they collapsed on their lines of communications, the French lost strength.

In mid-January, Yorck openly declared for the Russians and placed his forces at their disposal. Six weeks later, King Frederick William III fled to Silesia and secretly signed a treaty with the Russians at Kalisch. This treaty laid the cornerstone for the Sixth Coalition with the goal of liberating Germany based on the territorial configuration of Prussia in 1806. Great Britain rapidly concluded separate agreements subsidizing the Prussians and Russians and attempted to bring Swedish forces to Germany for use in a spring campaign. Austria remained neutral but began a massive mobilization, offering mediation to both sides.24

At this point we must digress before proceeding to the final military moves that ended this first phase of the campaign. Prussia had lost heavily during the Russian campaign. When her 17,000 are added to the Russian total, we find that the Allied field force was too weak to “liberate” Poland, much less Germany. Napoleon knew this. What he did not know about was Scharnhorst’s secret mobilization system, which now went into effect. Mobilizing reserves and Landwehr, and with British armaments, the Prussians fielded an army of 110,000 men prior to Napoleon’s return to Saxony in April 1813. Of this total, the rawest recruits were diverted to help the Russians cover the fortresses occupied by the French. However, the best-trained, some 55,000, marched to join the main Russian army.25

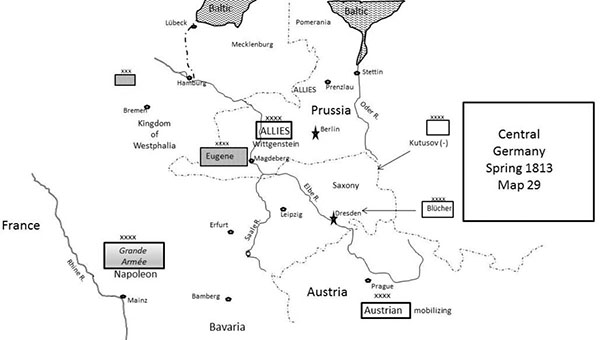

Map 29 Central Germany Spring 1813

The 1813 campaign up to this point had been one of operational pursuit. The frozen rivers of Germany provided Prince Eugene, now in command, no defensible barriers. He fought delaying actions as best he could as Germany exploded into revolt around his tired and demoralized troops. However, he was helped in no small measure by Kutuzov’s lackluster pursuit. The Allied forces consisted of three field armies: one to the north under the Russian general Wittgenstein, one in Silesia under General Blücher, and the main Russian army under Kutuzov still in Poland (see map 29). Wittgenstein’s army included his own corps and Yorck’s Prussians—about 50,000 men. Blücher’s army included a Russian corps under General Winzingerode. Other Prussian corps under Generals Friedrich von Bülow and Friedrich von Kleist were forming but not yet ready for operations.26 The Allies planned the liberation of as much of Germany as possible, which by April meant as far west as the Elbe River. Here Kutuzov wanted to stop. In the meantime, Wittgenstein conducted a flank march along the Elbe to join Blücher who had captured Dresden. Eugene attacked Wittgenstein near Mockern, which threatened to upset the Allied plans to concentrate. However, after this indecisive combat Eugene withdrew and informed Napoleon of his intention to abandon the upper Elbe and retreat as far as the more defensible Saale River.27

We must take a moment to understand, briefly, how Napoleon reconstituted his new Grande Armée. First, he called up massive quantities of young conscripts, both from France and his allies, to make up his losses in veteran infantry. However, given the very common practice of “draft-dodging” in France, Napoleon took the drastic expedient of denuding his navy of its sailors and gunners, creating an entire army corps of regiments de marine. He remanned his artillery wholesale with experienced gunners from the fleet. Finally, his biggest weakness was his cavalry and with the loss of half of Spain that theater no longer had need for as many horsemen. Accordingly, he transferred regiments wholesale from there, both as entire units as well as cadres for new regiments destroyed in Russia. Many of these did not arrive until after the armistice in June. It was a feat of organizational genius, but its costs were heavy and only partially solved Napoleon’s problems in recreating the sort of force he was used to wielding. Its chief advantage was its size, which was out of all proportion to what the Allies anticipated. Its chief disadvantages were its fragility, lack of cavalry, and overall lack of endurance—as we shall see, Napoleon’s adolescent conscripts were unable to sustain the high rate of operations exhibited by his previous armies.28

The second phase of the spring campaign might properly be entitled the “battle phase.” It was characterized by two fierce but indecisive engagements between the main armies of Napoleon and those of the Sixth Coalition. While Napoleon marshaled his forces at Erfurt for a resumption of the offensive, the Allies were thrown into a command crisis over Kutuzov’s poor health. The Tsar appointed Wittgenstein as nominal commander in chief, but his authority only extended over his own corps and Winzingerode’s. The Prussians, in a move to solidify unity of effort, generously placed their forces under Wittgenstein’s control.29 The corps of Miloradovitch and Tormassov, both senior to Wittgenstein, remained under the personal command of the Tsar. This confusing command structure was exacerbated by an operational dispute between the Prussians, led by Scharnhorst, acting as chief of the Prussian General Staff, and the Russian peace party formerly led by Kutuzov. Scharnhorst wanted to maintain the initiative and advance beyond the Elbe and disperse the French between the defiles of the Thuringian mountains and the Saale River before they gained strength—a lesson he had learned during the Jena campaign (see chapter 5). There were political imperatives as well: Austria was in contact and wanted the coalition to operate contiguous to her borders so that when she joined she would not have Napoleon between her and the main Allied forces. Obviously, the further west the Allies advanced the more time Austria would have to rearm and join them. Austria fully expected Napoleon to vigorously attack the Allies and wanted no part of any defeats until she was sufficiently rearmed.30 This Austrian imperative wielded a significant influence over the remainder of the Allies’ campaign and can be considered the dominant factor in the decision by the leaders of the Sixth Coalition to keep the bulk of their field forces in the southern part of the theater in southern Saxony and eventually Silesia.

Another consideration that weighed heavily in the short term involved the disposition of the Kingdom of Saxony, which had declared itself neutral despite its king’s desire to throw in his lot with the Napoleon.31 Kutuzov’s death, Blucher’s capture of Dresden and passage of the Elbe, and Wittgenstein’s successful flank march persuaded Scharnhorst and the Prussians that a continuation of the offensive to the Saale was the best course. Baron Müffling, part of Scharnhorst’s staff at the time, wrote, “We…placed our confidence in acting vigorously on the offensive, before Napoleon could unite with the Viceroy of Italy and fully develop his strength.” The ambitious and aggressive Wittgenstein, backed by the Tsar, concurred and the decision was made to advance. They underestimated Napoleon’s combined strength with Eugene by over 50,000, such were Napoleon’s organizational skills in generating new armies.32

The Battle of Lützen resulted from Napoleon’s resumed offensive. Napoleon’s plan was to incur a battle or induce the Allies to retreat across the Elbe, either of which he was convinced would give the initiative and momentum back to him. To do this he planned to turn the Allied position by making “a movement exactly the opposite of the one I carried through during the Jena campaign” by marching on Leipzig then down the Elbe behind the Allies to Dresden.33 The Russo-Prussian army surprised Ney’s isolated corps south of Lützen at the little village of Gross Görschen on May 2 (see map 30). Ney managed to hold on until Napoleon arrived with the bulk of his army of 110,000 men versus the 73,000 of the Allies. The Allied assumption that their veterans might provide the edge over Napoleon’s conscripts proved incorrect and Napoleon forced his opponents to retreat. Each side lost approximately 20,000 casualties. Napoleon was unable to fully capitalize on his tactical success due to his paucity of cavalry. As if to underscore this deficiency Blücher led a furious cavalry counterattack that stopped the French pursuit cold and served as a postscript to this bloody battle. In reference to the fighting abilities of the Prussian, Napoleon allegedly muttered, “These animals have learned something.” Unfortunately, Scharnhorst received a wound in the foot and died of blood poisoning some weeks later after turning over his duties as overall Prussian chief of staff to the capable Gneisenau.34

Napoleon had regained the initiative and the Allies retreated across the Elbe, but he had no operational reserves to press the issue, especially the “hell for leather” cavalry reserve of his heyday. The Allied plan remained, in Gneisenau’s words, to “dispute every inch…to convince the Austrians that they were resolutely determined not to spare their powers nor…leave the deliverance of Germany entirely at the discretion of Austria.”35 The line of operations remained along the Austrian frontier and a defensive position was chosen in the foothills of the Bohemian mountains adjacent to the town of Bautzen from which to impede Napoleon’s advance. Napoleon employed a classic operational manoeuvre sur les derrières against this position. His goal was to fix the Russo-Prussian army with his main army while Marshal Ney, whom he had dispatched to the north to threaten Berlin, moved south with two corps to arrive in the Allies’ rear. Ney, or more probably his chief of staff Baron Jomini, directed all four corps (80,000 troops) against the Allied flank and rear at Bautzen. This fortunate accident was offset by Jomini’s orders to the corps to march along the same route in column, thus limiting the coup de grâce to one narrow line of approach to the Allied vulnerable right flank commanded by the intelligent and resourceful Barclay de Tolly.36

The battle began on May 20 and all initially went well, with the Allies advancing deeper into Napoleon’s trap. On the second day, Ney’s four corps arrived with plenty of time to cut the Allied line of retreat and defeat their army in detail. But Ney further bungled the tactical execution by placing himself with the leading elements of the attack bogged down in the village of Preititz. Barclay informed Müffling of the impending disaster and weakness of his position and that officer convinced Gneisenau to persuade the Allied high command—Wittgenstein, Tsar Alexander, and King Frederick William III—to retreat. As the Allies retreated into Silesia they inflicted a series of sharp rebuffs to Napoleon’s cavalry-deficient pursuit, particularly at Hainau on May 26 where one of Napoleon’s infantry divisions was ambushed and effectively wiped out.37

In the aftermath, recriminations on the French side ran deep and Marshal Berthier preferred charges against Jomini (but not Ney). Jomini, in a huff, deserted to the Allies where the Tsar added him to his growing group of personal military advisors.38 On the Allied side, Wittgenstein lost his job to Barclay de Tolly, whose conduct during the battle had earned him the laurels he long deserved. On the northern front, Napoleon peeled off another army under Marshal Oudinot to capture Berlin, a prerequisite to advancing to the Oder and relieving the French garrisons there. Oudinot’s opponent was General Bülow who now had a sizable corps, well-armed with British equipment flowing through the Baltic and Hamburg. Oudinot and Bülow fought each other to a stalemate in the plains and forests southeast of Berlin, their last engagement occurring at Luckau on June 4. Thus, at the end of May, the Allies seemed to be in hopeless shape, their main forces had retreated into Silesia with Napoleon in pursuit and another force had narrowly averted the capture of Berlin. In the words of one observer the Allies were “absolutely in a cul de sac.” Additionally, the coalition itself seemed in danger of breaking up over the issue of in which direction to retreat.39

However, Napoleon’s new Grande Armée had no more offensive power left, being composed of many young recruits with little training and almost devoid of effective cavalry. Napoleon had robbed “Peter to pay Paul” by weakening his Spanish armies and had no more operational reserves on hand to finish the campaign. On June 4 at Pleischwitz the representatives of Napoleon and the Allies signed a cease-fire which later resulted in an armistice that was to last most of the summer. Why had Napoleon, on the verge of trapping the Allied armies in Silesia, settled for an operational pause? He explained it as, “lack of cavalry…and the hostile position of Austria.” Napoleon’s army was just as exhausted as the Allies and his experience in Russia had taught him the dangers of a protracted campaign beyond the capabilities of his army.40 To fully understand Napoleon’s problems we must address the other aspects of this campaign that had contributed to the French exhaustion.

The first of these, the problem of the fortresses Napoleon left along the Allied lines of communication, is disposed of rather quickly, but its bearing on Napoleon’s problems is part of the entire mosaic. Napoleon’s tasks for his fortresses were threefold: they were to tie down Allied forces; interrupt their lines of communication; and finally, because most of them were at major road and bridge centers, facilitate his own rapid movement when he advanced eastward. As far as the first task the reverse situation was true, Stewart remarks that the French garrisons were “nearly double the blockading force.”41

Not only did the Allies mask these fortresses with minimal forces but also the troops used were often the least trained. These fortresses interfered relatively little with the Allied lines of communications during the critical period when the French withdrew for the reason that most of the rivers were frozen, rendering the bridges located at the fortresses irrelevant. By the time the rivers had thawed, the front was far to the west and the Allies had opened up new lines of support for their armies. Additionally, Napoleon’s line of operations in the spring, in pursuit of the main Allied army, took him south from most of the fortresses. The example of Thom, which surrendered on April 16, provided other serendipitous benefits; captured artillery was immediately put to use in the Allied artillery park while the German partners of the French inside the fortress were paroled, many of them enlisting in the ranks of their former enemies (including a unit being formed by Clausewitz known as the Russo-German legion).42

The second set of operations involved the employment of numerous Cossacks, partisans, and friekorps by the Allies against Napoleon’s communications. One Napoleonic historian credited these operations with shifting a balance of some 53,000 troops away from the French main forces for a cost of approximately 5,000 troops, mostly Cossacks. Their effect contributed measurably to Napoleon’s operational problems. The first phase of these operations was an outgrowth of the way in which the Russians had been employing their Cossacks all along. Wittgenstein initiated these operations, which were a response to a request by emissaries of the Hanse cities and Eugene’s withdrawal across the Elbe.43

The initial raid, by a mixed force of regular Russian cavalry, Cossacks, and expatriate Germans, succeeded beyond the Allies’ wildest dreams. Its commander, Colonel Tettenborn, boldly advanced into Mecklenburg to secure the safety of Swedish Pomerania and gain the allegiance of the Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin to the Allied cause. However, the most stunning result was the withdrawal of the cowed French from Hamburg and the occupation of that strategic city by Tettenborn on March 18. Hamburg was later recaptured at the end of May, but while it remained in Allied hands, the British off-loaded tons of war material. These arms equipped the numerous Hanoverian, Mecklenburger, and other levies forming in this district under Count Wallmoden (formerly commander of the Hanoverian army).44 The importance of the capture of Hamburg, the anchor of the French position on the lower Elbe, can be judged by Napoleon’s response. He assigned possibly his most capable Marshal Davout the job of recapturing Hamburg and securing the lower Elbe. Davout, whom Napoleon could ill afford to do without, held down this assignment for the remainder of the war. Secondly, Napoleon held back a large percentage of his scarce cavalry, desperately needed for his campaign in Westphalia to protect that puppet kingdom from falling.45 Following Wittgenstein’s example, General Bülow detached Cossack forces under his control to cooperate with partisans and friekorps beyond the Elbe. These forces, led by General Doernberg (another Hanoverian) and the Russian general Czernicheff, proceeded to Luneberg where they destroyed the French division of General Joseph Morand on April 2–3. The Saxon troops of Morand’s division, after the action, deserted en masse to the Russo-German legion of Czernicheff’s command.46 Wallmoden was appointed the commander of all these disparate forces in April and not long after Clausewitz became his chief of staff.

A final example of these raiding operations was the capture of Leipzig three days after the signing of the Armistice of Pleischwitz. Czernicheff, who had just destroyed a Westphalian column at Halberstadt, learned from his Cossacks that Leipzig, garrisoned by 5,000 French cavalry and infantry, contained numerous magazines and wounded. Czernicheff contacted the Russian General Woronzov, who was observing Magdeberg, and proposed a raid. Woronzov agreed to this plan and they were joined by the celebrated friekorps of Major von Lützow. In a brisk action on June 7, the combined forces of Woronzov, Lützow, and Czernicheff dispersed the French cavalry outside Leipzig and proceeded to occupy the city, only to learn that an armistice had been concluded three days earlier.47 Woronzov’s raid reveals just how tenuous Napoleon’s lines of communication through Saxony were. If we wonder as to Napoleon’s weakness in cavalry, the above operations show that a good portion of it was employed guarding the lower Elbe and the French rear, and not very effectively either.

In review, one sees in this campaign the standard Napoleonic format: a search for decisive battle along a single line of operations, in this case north of the Bohemian mountains. However, a cursory examination reveals a more complicated picture. The operations of the Allied forces during this phase of the campaign were distributed, displaying a level of sophistication not previously seen in central Europe. The most compelling proofs of operational distribution were these raids, harassment, and the taking and holding of key cities by the forces of Tettenborn and others. That these operations were the outgrowth of the Russian experience, and largely opportunistic, does nothing to diminish their operational effect. Napoleon now had another front that he had to honor—in his strategic and operational rear. The events leading to the armistice following Pleischwitz provide the evidence that both sides were exhausted and meet the criteria of modern operational campaigns being exhaustive in the Delbrück sense (see chapter 1).48

The Allies did not rest on the serendipitous results of the first raids, but continued to press the French and bring a new level of organization to these forces by appointing Wallmoden to command and synchronize their operations. Finally, the commitment of substantial French forces for security—including much of their cavalry—can be considered evidence of operational art because it denied Napoleon the tool he needed to engage the Allies throughout the depth of the battlefield following his tactical victories at Lützen and Bautzen. Also, the Allies employed continuous logistics and distributed deployment, which can be said to have “arrived.” Witness the mountains of British equipment the French captured when they retook Hamburg. This equipment gives only some indication of the far larger amounts that made it into the hands of the Hanoverian, Mecklenburger, and Prussian levies to say nothing of the rearmament of the Cossacks with better equipment.49 The British not only armed the Germans, but they did so on the Germans’ home ground, thus integrating the processes of mobilization and deployment by avoiding the classical practice of marching unarmed levies to a depot or collection point. Napoleon performed the same extraordinary task, arming and training his young conscripts on the march—and without the advantages conferred on the Allies by command of the sea to transport supplies.50 The battles of Lützen and Bautzen show that the Allied armies had reached new levels of operational durability. This durability was admittedly immature; they were exhausted after six weeks of fighting—but so were the French. However, when we factor in that the Russians had been fighting for almost a year without pause, we realize that the Russians may have been more durable than their Prussian ally. Imagine the coalition army of 1805 holding together after a Bautzen or a Lützen? Thus, the Allied coalition had become more politically durable.

Two areas that superficially appear less mature than the others discussed are operational vision and instantaneous command and control (C2). Instantaneous C2 is the more problematic of the two. The only medium of “instant” communications was that of the shared vision of the participants. All wanted to fight the French, hurt them as much as possible, and ostensibly liberate Germany. This led to an environment that favored commanders willing to make independent decisions. Such rapid decision-making in response to opportunities yielded the most fruit in the deep operations along the Elbe and in Napoleon’s rear. As for operational vision, the Allies were hurt by the deaths of Kutuzov and Scharnhorst, particularly Scharnhorst if we are to believe Müffling, Clausewitz, and Gneisenau. But we catch a glimpse of Scharnhorst’s operational vision as we see the product of his creativity in action—the mobilization and performance of the Prussian army.51

The survival and will to fight of the coalition army after Lützen and Bautzen and the shared vision remaining in force after Scharnhorst died provide further evidence. Perhaps the true measure of operational vision is the ability to pass it along to one’s peers and subordinates, rather than merely to rely on electronic communication. We must also recognize that the coalition itself had improved and was improving.52 The effort the Sixth Coalition expended in maintaining its unity was unique for the Napoleonic Wars. Blücher’s willing subordination to Wittgenstein is but one example. Even the choice of the line of operation, south away from the threatened capital of Berlin, was a departure from the classical strategy of the past. It would be like Kutuzov retreating toward Kiev instead of Moscow after the battle of Borodino. The signing of the armistice in June 1813, too, has a modern flavor. The Allies could well have kept fighting, which might have kept Austria out of the war, or done as Austria did after Wagram and negotiated an unfavorable peace. Instead they chose the best solution, an operational pause in the form of a cease-fire and then armistice. This represented a collective vision; coalition unity for the sake of ideals—liberation for Germany and the restoration of the balance of power. This vision provided fertile soil for operational commanders, but the harvest was yet to come.

One must also give “the God of War” his due.53 Napoleon was learning new ways of war, despite his ongoing search for the decisive battle that ended the campaign. The battle of Bautzen provides the best evidence of Napoleon fighting in a distributed fashion and further evidence of his continued mastery of operational maneuver. Napoleon, like Robert E. Lee at Chancellorsville, assigned himself the job of fixing the Allies, while Ney delivered the coup de grâce from the flank with another entire army. Napoleon had been effectively fighting as an army group commander since Russia and this campaign shows that his sophistication at maneuvering armies was increasing despite the degradation of his tools. Finally, Napoleon recognized that he must respond to the operational threat to his rear and flanks, another lesson from Russia. The Emperor allotted his precious cavalry and arguably his most capable marshal to these tasks. However, Napoleon’s own distributed efforts against the Allied rear failed primarily because of the sophistication of the Allies’ response. His strategy of retaining fortresses evoked a nonclassical response from the Allies—they simply masked these fortresses. Nevertheless, Napoleon, too, was evolving, and fighting in a more distributed manner.

THE OPERATIONAL PAUSE—TRACHENBERG AND REICHENBACH

On October 9, 1813, Napoleon arrived with 150,000 troops opposite the town of Duben on the Mulde River. He had made the decision two days earlier to march west from his position at Dresden in order to intercept two coalition armies that had united and moved into his rear south of the Elbe River; one under Field Marshal Blücher and the other under the former marshal Bernadotte. Napoleon’s advance guard had engaged the rear guard of Blücher’s army (Sacken’s corps) for most of the day and as these combats died down and darkness closed in, Napoleon realized that the Allies had refused battle. Where had the Allies gone? More importantly why had two Allied armies, both recently victorious in combat against Napoleon’s flank armies and with approximate numerical parity in numbers of troops, refused to give Napoleon battle?54

Historical hindsight provides a clue. One week later, these same Allied armies, particularly the aggressive Blücher’s Army of Silesia, effectively united with an even larger Allied force, the army of Bohemia (180,000 troops), advancing from the south in the sprawling Saxon countryside around the city of Leipzig. During a bloody battle of attrition from October 14–19, these forces, in Europe’s largest battle to date, defeated Napoleon and forced him to withdraw completely from Germany west of the Rhine. This result was no accident, and had in fact been outlined in an operational plan for the campaign developed earlier that July in Silesia. The Allies had refused battle in order to maneuver as planned to gain more favorable conditions for an engagement in the future.

The situation after the armistice, it will be remembered, was one of acute exhaustion on both sides. Gneisenau freely admitted as much, stating that “Austria had given Russians and Prussians to understand that such a period of time was necessary to complete her armaments.” He additionally listed eight objectives that he felt needed to be accomplished in order to renew the combat with Napoleon: reinforce the Russians, principally through a new army forming in Poland under Count Bennigsen; complete the manning of the Prussian line regiments; obtain arms and ammunition from Great Britain and Austria; prepare “accoutrements” (uniforms); arm, form, and discipline the landwehr; provision and repair fortresses; establish bridgeheads on the Oder river (the main crossing sites were in French hands); and procure and collect provisions.55

The advent of Austria as an active belligerent against Napoleon was by far the most important development during the armistice. Ironically, this goal, and many Gneisenau listed, was shared by Austria’s foreign minister Clemens von Metternich who commented upon the armistice as follows: “An Armistice will be the greatest of blessings…it will give us an opportunity to get to know each other, to concert military measures with the Allies and to bring reinforcements to the most threatened points.”56 From this quotation it appears that Austria’s participation was a forgone conclusion. However, as Charles Stewart observed, “It is difficult to give an adequate idea of the anxiety that prevailed [on the part of Great Britain, Russia, and Prussia]…with respect to the decision of Austria.”57 Metternich’s master, Francis I, was not as committed to war with Napoleon as his minister and hoped that the armistice might give Austrian diplomacy the opportunity to negotiate a lasting peace. The terms to establish a peace comprised: the return of Illyria (the Dalmatian coast) to Austria, the territorial aggrandizement of Prussia via the dissolution of the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, the break-up of the Confederation of the Rhine, and the reestablishment of France’s eastern boundary along the Rhine. The acceptance of these terms by Napoleon would have guaranteed Austrian neutrality and certainly freed Germany geographically from French influence. On June 26, 1813, Metternich had presented these terms to Napoleon at Dresden and was rudely rebuffed; Napoleon would accept the Illyrian concession only. Metternich departed Dresden convinced that peace with Napoleon was not possible.58

From Dresden Metternich proceeded to Allied headquarters in Reichenbach, Silesia, where he committed Austria to join the Sixth Coalition should Napoleon remain intransigent. Since Napoleon had already made clear his intent, the Treaty of Reichenbach was in effect Austria’s declaration of war. Now the Allies proceeded to plan in earnest for a resumption of hostilities with Austria as a cobelligerent (the armistice had been extended into August). It was at this moment that Wellington’s summer offensive in Spain climaxed. He engaged King Joseph’s army at Vitoria with his Anglo-Spanish-Portuguese army and routed it. Although French troop losses were not that large, the material and moral consequences of Wellington’s victory had the strategic effect of expelling the French once and for all from Spain. It could not have come at a worse moment for Napoleon and galvanized the Sixth Coalition, increasing Emperor Francis’s conviction that he must throw in his lot against Napoleon. However, no single treaty of grand alliance linked all the players together.59

Against this backdrop the Russian, Prussian, and Swedish high commands met at Trachenberg in Silesia to decide the command structure and work out a plan of operations. Barclay, still the nominal commander for the Russo-Prussian army, had been working off a series of plans that resembled some of the elements of Russian plan of the year before. Not surprisingly, he built on the idea that as Napoleon advanced against one army, the other—a Russo-Prussian force—would attack his flank. Underestimating Napoleon’s ability to organize, Barclay predicted a clear superiority over the French.60 As it turned out, the accession of Sweden to the coalition resulted in three armies. A “galaxy” of diplomats and leaders of the Sixth Coalition descended upon the castle of Trachenberg in Silesia on July 9–12 to discuss acting “in concert in the distribution of their forces” and create “a…general plan of operations.”61 Attendees included the Tsar, King of Prussia, and Crown Prince of Sweden (Bernadotte) and their personal military advisors. Gneisenau, Blücher, Schwarzenberg, his chief of staff Josef Radetzky, and the expatriate Jean Moreau, who advised the Tsar, were not there—but their input was. The names of the generals who were actually there are not as well known: Lowenhielm (Swedish), Toll and Volkonsky (Russian), and Knesebeck (Prussian).62 According to Baron Müffling, the conference resulted from the Tsar’s desire to resolve command issues revolving around Bernadotte.63

Bernadotte was still awaiting Prussian and Russian ratification of the treaty he had signed in April that guaranteed Sweden compensation in Norway at the expense of Napoleon’s Danish ally. He had not been notified of the cease-fire and subsequent armistice and had threatened to withdraw from the coalition. Bernadotte’s terms now included command of one of the principal Allied armies. In addition to the approximately 110,000 Swedes, Prussians, Russians, British, and North German troops already under his command, Bernadotte demanded command over Blücher’s Army of Silesia.64 Bernadotte’s “demands were too great, and could not be conceded by the sovereigns. They wished, however, to see him return satisfied from Trachenberg…and admitted that circumstances might [italics added] render it necessary for him also to take the command of…the Silesian army.”65 This compromise could have had a negative impact during the upcoming operations because it created an environment for conflict with Blücher over combined command of the armies. However, Blücher and the dynamic Gneisenau conducted upcoming operations with little reference to Bernadotte; part of their success would be due to that factor as well as the fact that Bernadotte’s chief subordinate, General von Bülow, often initiated engagements that his master would have avoided had he commanded von Bülow’s corps!66

Blücher’s Silesian army was to be the smallest of the three because nearly 100,000 troops, Russians and Prussians, were to accompany the Tsar of Russia and the King of Prussia to join the Austrian army of Bohemia—this latter conglomeration eventually came to a strength of over 220,000 men and can rightly be considered an army group.67 Tsar Alexander hoped for the appointment of Archduke Charles as the commander of the main Austrian field army, who would thus also serve as commander of the combined army formed when the Russians and Prussians joined forces with the Austrians in Bohemia.68 In May, Francis and Metternich appointed Prince Schwarzenberg as the Austrian commander in chief. The Tsar subsequently nominated himself as supreme commander of the combined armies in Bohemia. Metternich countered with the argument that the country with the preponderance of force should command the main army. On August 6, the issue came to a head. Metternich threatened to maintain Austrian neutrality should Alexander replace Schwarzenberg as supreme commander. The Tsar reluctantly acquiesced in this decision.69

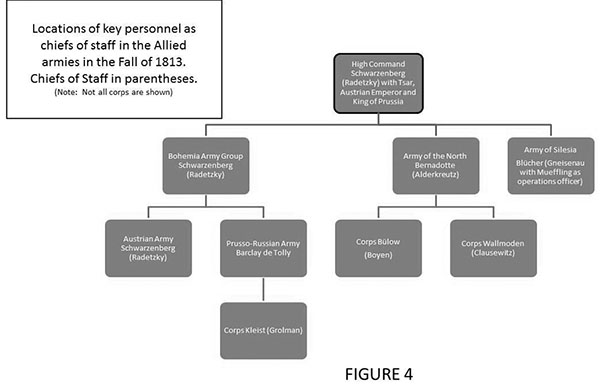

The problem with this arrangement was that Schwarzenberg assumed command at three levels with only one undermanned staff led by Radetzky, the Austrian chief of staff (see figure 4). The first level was that of the Austrian field army—nearly the same size as Charles’s army at Wagram. The next level up—the Army of Bohemia—added the Russo-Prussian army commanded by Barclay. This force was effectively an army group, but no additional staff was provided to control it. This was a problem the Allies never resolved; as with the Swedish issue, command of the Army of Bohemia raised its ugly head repeatedly during the upcoming campaign. Finally, Schwarzenberg and Radetzky were nominally responsible for the operational direction of Blücher and Bernadotte’s armies, a task far beyond their means or inclination and that they wisely left to the expedient of decentralized execution, much as the Russians had done in 1812. The choice of Schwarzenberg proved a good one despite critics of his generalship. It was Schwarzenberg who had recommended attaching Russian and Prussian corps to the Austrian army to further improve unity of effort.70 Historian Gordon Craig’s evaluation of Schwarzenberg summarizes his suitability for a multinational command:

Figure 4 Locations of key personnel as chiefs of staff in the Allied armies in the Fall of 1813. Chiefs of Staff in parentheses.

(Note: Not all corps are shown)

The new supreme commander’s talents were…more diplomatic than strictly military, and it was probably a good thing that this was so. Like Dwight D. Eisenhower in another great coalition a hundred and thirty years later, his great gift was his ability, by patience and the arts of ingratiation, to hold together a military alliance which before Napoleon was finally defeated comprised fourteen members, and to persuade the quarreling monarchs and their field commanders to pay more than lip service to the alliance’s…plan.71

The plan agreed to at Trachenberg envisioned three main armies. The two larger armies, under Bernadotte (90,000) and Schwarzenberg (220,000), would threaten Napoleon’s flanks from the north and south. Blücher’s smaller Silesian army (50,000) would face Napoleon to the east but had specific instructions to “avoid committing itself except in the case of an extremely favorable situation.” Any two armies not engaged by the French main effort were to attack the French flank, rear, and lines of communications.72

The Convention of Trachenberg (see appendix) was forwarded to Schwarzenberg and Radetzky after the conference in July. Radetzky was another reason that decision to give the supreme command to the Austrians proved fortuitous. Up to this apoint, Radetzky had been a quiet but effective force for reform in the Austrian army and led Austria’s mobilization and planning once the extent of Napoleon’s disaster in Russia became known. When Radetzky saw his initial operations plan, which assumed a successful advance to the Rhine, obviated due to the sledgehammer blows of Napoleon during the spring of 1813, he began work on a new plan to defeat Napoleon.73

Radetzky explained his plan to the British envoy Sir Robert Wilson as a “system of defense combined with offensive operations on a small scale over a general offensive movement which might win much, but also might lose all.”74 Radetzky modified the Trachenberg Convention in the following important ways. First, the plan he received predicted an immediate offensive by Napoleon toward Bohemia. It therefore directed Bernadotte to energetically advance south and combine with Blücher to form a second army in Napoleon’s rear of about 120,000 men. This was done to make Bernadotte happy but Radetzky wanted three independent field armies operating against Napoleon until he could be engaged with a clear superiority (presumably by the Bohemian army group). Secondly, no allied army would go on the offensive against Napoleon initially. Neither of the two smaller armies was to engage him, but rather retreat energetically, causing French forces to make forced marches in pursuit. This meant that the Allies would react to Napoleon’s movements as they employed a strategy of exhaustion, making his forces march and countermarch until battle could be accepted on favorable terms. It ceded to Napoleon his favorite principle of war—initiative. However, the Austrians intended to use Napoleon’s strength against him, to have him spend his initiative and energy on the offensive, thereby reaching, as he had in Russia, a culminating point of victory far from France, resources exhausted, and surrounded by hostile armies. Radetzky and Schwarzenberg forwarded their changes from their headquarters to Reichenbach on July 19 and these were adopted verbally, although never finalized in written form. Thus the Trachenberg Convention became, properly, the Reichenbach Plan.75 The Sixth Coalition’s leaders created military history’s first modern operations order for a multinational army group. There were other inputs that affected the plan’s operational execution. General Jean Moreau, one of the Tsar’s many advisors, for example, advised: “Expect a defeat whenever the Emperor attacks in person. Attack and fight his lieutenants whenever you can. Once they are beaten, assemble all your forces against Napoleon and give him no respite.”76 Jomini, now one of the Tsar’s aides, cautioned against underestimating Napoleon—stating that he remained “the ablest of men.”77

Finally, the equipping and training of the Allied armies during the armistice, including a 10-week rest for the veterans, yielded an immense force for the coming campaign. The Army of Bohemia passed in review on August 19 outside Prague for the monarchs of Austria, Prussia, and Russia. The British observers, whose government had largely paid for much of what was on display, noted that the funds had been well spent and were satisfied with the state of the soldiers and equipment.78 In central Europe alone the coalition deployed over 570,000 soldiers against approximately 410,000 troops of the reconstituted Grande Armée.79 This disparity is even greater given the more than 50,000 veteran French troops cut off in fortresses by lesser numbers of second-line troops. Napoleon’s Grande Armée of August 1813 was a more potent force than the one he had marched and fought to exhaustion in the spring. His Imperial Guard and cavalry had been reconstituted by extraordinary efforts, especially by the expedient of denuding the armies in Spain. Napoleon’s artillery was also numerous and excellently served (often by former sailors)—but not nearly as mobile. However, his army remained overwhelmingly young—two-thirds of his troops were between 18 and 20 years of age. About 90,000 of these troops would be on the sick lists before hostilities began.80 The many foreign troops, especially Germans, exacerbated these factors because they composed a significant number of Napoleon’s veterans. Napoleon compounded his problems by apportioning the majority of these German troops to his flank forces, just as he had in Russia. These forces predominantly opposed fellow Germans instead of the more ethnically diverse force of the Bohemian army. Finally, Napoleon was forced by circumstance to employ the best of his remaining independent commanders elsewhere: Eugene in Italy, Soult and Suchet in Spain, and Davout holding the lower Elbe. The only exception was Marshal St. Cyr, who kept guard at Dresden.

One more command arrangement must be discussed before proceeding to the operations—the Prussian General Staff system. Although the Prussians commanded the numerically smallest of the field armies, they wielded a significant operational influence across the coalition. Gneisenau took what might be seen as a disadvantage, the breakup and distribution of the four Prussian army corps among the three armies, and turned it to his advantage. He did this by assigning competent Quartermaster General-trained staff officers as chiefs of staff to all of the main corps and even some of the non-Prussian ones. For example, Clausewitz, still in a Russian uniform, served as chief of staff to Count Wallmoden, commanding the corps observing Davout in Hamburg.81 Hermann von Boyen, a major reformer of 1807, was assigned to the critical corps of General Bülow serving under Bernadotte. In the same manner, Karl Grolman, also a reformer and former Prussian minister of war, was assigned to the corps of General von Kleist serving with the Bohemian army (see figure 4). Both Grolman and Boyen had been protégés of Scharnhorst and part of his intimate circle. Gneisenau instructed these men to coordinate, as much as possible, their actions with his in Silesia. If problems arose the chief of staff “had special avenues open to him. He communicated any complaints or doubts directly to the chief of the General Staff himself.”82 They overcame the difficulty of communication over the vast theater that spread around Napoleon’s salient in Saxony by this shared understanding, which was transmitted in the Reichenbach Plan and managed in execution by Gneisenau.

Meanwhile, the sham “peace talks” in Prague collapsed on August 10—despite Napoleon’s agreement to most of the Allies’ terms. Three days later, Austria declared war on France.83 By this time, the Allies had a second operational echelon approaching under Bennigsen, the Army of Poland with 60,000 recently raised Russian troops. Napoleon had to act before these arrived in the theater. Instead of advancing directly on Bohemia as the Allies expected, however, he had Marshal Oudinot advance on Berlin with 90,000 troops while Napoleon remained in two operational lines around Dresden and just to the northwest of Dresden with 250,000 men, including his Guard and cavalry reserves.84 Napoleon’s apparent inaction caused the Allies to reconsider their plan. They had not allowed for an inert defense by their opponent, but anticipated a move on his part in order to react with the armies not opposed to him. A “general offensive” movement, contrary to Schwarzenberg and Radetzky’s desires was agreed to by a council of war. Schwarzenberg had planned the logistics for the Austrian army to support an eventual advance on Leipzig, and now that an offensive was to be conducted, he naturally recommended Leipzig as the objective. Orders were sent and the Anny of Bohemia began to advance. The Tsar, advised by Moreau, now interfered with the arrangements of the nominal commander in chief. Alexander and Moreau felt a move closer to Blücher in Silesia warranted, and indeed that was where Napoleon had gone in response to an advance by the Prussian firebrand. The Tsar’s view prevailed, despite the opposition of Schwarzenberg, and Dresden became the new Allied objective. Schwarzenberg had considered moving on Dresden as well but had wanted to take advantage of his logistics preparations and wheel on the city after advancing through the Bohemian mountains. Metternich, responding to Schwarzenberg’s consternation over these events, wrote, “the most sincere understanding between us and our allies is so important that we cannot offer too great a sacrifice” (see map 31).85

Logistics support, set up for an advance on Leipzig, soon broke down in the advance to Dresden. The effects of countermarching and the wet, rainy weather further fatigued and slowed the advance of the Allies. The lead elements of the Army of Bohemia arrived, cold, tired, wet, and hungry, south of Dresden on August 25. Napoleon was not yet there. Instead of attacking while Napoleon was still absent, another war council was held by the “military college” accompanying the army.86 Schwarzenberg and Jomini supported the Tsar’s recommendation for an immediate attack, but Moreau and Toll advised against it.87

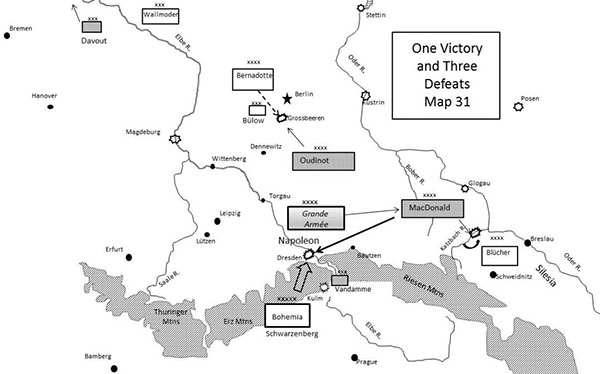

Map 31 One Victory and Three Defeats

The attack was put off until the next day (August 26). Marshal Gouvion St. Cyr faced the Allies at Dresden. He had earned his marshal’s baton in Russia at Polotsk fighting just the type of battle the Allies now contemplated. Allied skirmishers had already found Dresden’s walled houses and gardens fortified for the impending attack. As the initial combat into these fortified suburbs began, Napoleon dramatically arrived. With Napoleon’s arrival the mood at headquarters rapidly changed and Moreau advised Alexander to withdraw. The Prussian King uncharacteristically asserted himself and urged that the attack continue. While the supreme command bickered, the assault went on in response to orders already issued. The result was a defeat for the coalition as Napoleon crushed the wings of the Bohemian army group. Already half-beaten, the Allies compounded their mistake and fought a second day until forced to withdraw on August 27. Their losses were significant: 38,000 Austrians, Prussians, and Russians were casualties, including many prisoners, versus 10,000 French casualties.88

Dresden was the exception that proved the rule. The Reichenbach plan had not intended an offensive battle against Napoleon and his main force by one army—particularly against a defensive position like Dresden. The Allied leaders, partially as a result of the ponderous command process of the Bohemian army, diverted in spirit from the agreed plan, and fought Napoleon on his terms. Moreau, whose legs were shot off by a cannonball, tried to put a bold face on the defeat as he wrote to his wife with his dying hand, “That scoundrel Bonaparte is always fortunate…. Though the army has made a retrograde movement, it is…from want of ensemble, and in order to get nearer General Blücher.”89 The British observer Wilson was less charitable in his assessment; he called the battle “an ill-advised enterprise executed with great vigour.”90 Dresden validated Napoleon’s improvements to his army during the armistice. His Young Guard had resolutely defended the city on August 26 and his cavalry and horse artillery had been critical in the counteroffensive that forced the Allied withdrawal the following day. However, Marshal Marmont had earlier (August 16) expressed to Napoleon his concern about fighting on such a widely extended front with the prophetic words, “I greatly fear lest on the day on which Your Majesty gains a great victory, and believes you have won a decisive battle, you may learn you have lost two.”91 These concerns literally came true.

The Allies’ operational scheme now paid handsome dividends on other fronts. Recall that Marshal Oudinot, opposed to Bernadotte, had been assigned the mission of taking Berlin. He began his advance on August 18. He initially gained some minor successes but was forced to divide his army into three corps-sized columns as he advanced in the rain through the heavily wooded terrain south of Berlin. At the same time, Davout advanced in support from the west, including Girard’s division from Magdeburg. Bernadotte’s reaction was typical of a sovereign whose chief concern was the preservation of his army—he built additional bridges over the Spree River to facilitate a withdrawal to the north with the intention of abandoning Berlin.92

Bülow, the commander of Bernadotte’s Prussian corps, refused to abandon Berlin, possibly as a result of previous coordination with Gneisenau.93 Oudinot’s separated columns offered Bülow an opportunity to attack the French while they were dispersed with wooded country to their rear. Oudinot’s right-hand column under General Bertrand successfully repulsed an attack by General Tauenzien’s Prussian landwehr at Junsdorf on August 22. Bertrand pursued on August 23 and was in turn repulsed by Tauenzien at Blakenfeld. This defeat prevented Bertrand from coming to General Reynier’s aid when Bülow attacked his Saxon Corps, Oudinot’s central column, in a driving rain at Grossbeeren on August 23. Reynier withdrew before Oudinot, personally leading the left-hand column, could come over in support. Oudinot’s entire army was forced to fall back as a result. The domino effect also extended to Davout, now exposed by Oudinot’s retreat, and he withdrew to Hamburg. Girard was most unlucky in these series of setbacks; he was caught in an isolated position and savaged by the ubiquitous Czernicheff and his Cossacks on August 27, losing almost half of his division in the process.94

Likewise, in Silesia, Blücher’s adherence to the Reichenbach plan led to victory on a larger scale. As in the north, difficulties between the commander and his subordinates caused problems. The situation in Blücher’s army was the reverse of that in Bernadotte’s—it was his subordinate, the French émigré General Louis Langeron, who was the more cautious. Blücher was under the nominal command and control of Barclay de Tolly, who had been delegated the responsibility of coordinating the operational movements of the Army of Silesia with respect to the Army of Bohemia by Schwarzenberg. Barclay and Blücher had met on August 11 at Reichenbach to ensure the proper coordination and understanding prior to the Russian’s departure for Bohemia. Blücher’s instructions were not to become decisively engaged with the force facing him. He proposed a more aggressive role for his army that involved attacking the French if Napoleon was confirmed not present and if the French had not attacked first. This course of action was approved by Barclay. However, Barclay neglected to inform Langeron of this change. As a result, Blücher’s energetic advance on August 20 against the French was robbed of success when Langeron refused to cooperate in an effort to cut off an isolated corps under Ney near the Bober River.95

Meanwhile, Napoleon arrived on August 21 with considerable reserves to confront Blücher. Blücher, greatly outnumbered, retreated according to plan to a previously prepared defensive position on the Deichsel stream. Advancing beyond this position, Langeron undermined Blücher’s plans yet again by falling back as soon as he was attacked on August 22. This precipitate retreat undermined the integrity of Blücher’s position and he again withdrew to a position behind the Katzbach River. Blücher denied Napoleon a major battle and French casualties roughly equaled those of the Allies—attrition this manner favored the Allies. Almost 5,000 Allied troops were lost as a result of these misdirected actions.96

When Schwarzenberg’s lumbering advance on Dresden pulled Napoleon and his reserves away to assist St. Cyr, Napoleon left Marshal Macdonald in command of his own corps and three others (including Sebastiani’s cavalry corps) with strict orders not to advance beyond the Katzbach. Heedless of these instructions, Macdonald pursued Blücher beyond the Katzbach on August 27.97 It was at this time that Blücher noted a lack of aggressiveness in the French approach and pursuit, correctly deducing that Napoleon had departed. He and Gneisenau resumed the offensive in accordance with their agreement with Barclay. The result was a meeting engagement along the Katzbach, which a driving rain had swollen into a raging torrent. Blücher waited until about half of Macdonald’s army was across before attacking in force on the plateau above the stream. The portion of Macdonald’s army on the Prussian side of the river was totally defeated and thrown into the river. Many French drowned as they attempted to recross and Macdonald lost over 15,000 men and many cannon. Worse, the army disintegrated in the cavalry pursuit that followed, although many of these men later returned to the colors. Gneisenau’s comment on the operations of the Silesian army illuminates the perceptions of those present: “In the course of eight days [Blücher] had fought [Macdonald] in eight bloody encounters, not to mention trifling affairs; beat him completely in a pitched battle and directly afterwards made three serious attacks upon him.”98

The results of the Katzbach and Grossbeeren clashes validated the Reichenbach Plan, despite the serious setback at Dresden. Local disunity in both of the smaller armies had threatened failure: Bülow’s conflict with Bernadotte and Langeron’s insubordination vis-à-vis Blücher. Nevertheless, operational unity due to general adherence to the operational framework yielded two significant victories that effectively negated the results of Dresden, just as Marmont had predicted. More victories followed. Despite the pounding at Dresden, the Army of Bohemia conducted a fighting withdrawal south through the forests of the Bohemian Mountains. Partly due to tenacity, and partly due to luck, a victory was obtained on this front, too. After Dresden, Schwarzenberg complained bitterly to Metternich and wrote that either the Russo-Prussian Reserve Corps be placed “under my immediate orders, or someone else be entrusted with the command.” While Schwarzenberg vented to Metternich, he and Radetzky resolved to halt the French pursuit by General Vandamme that threatened to cut off major portions of the Allied army group. On August 29, at Preisten (just south of Kulm), Schwarzenberg turned and fought, sacrificing the Russian Guards in a vicious counterattack that halted Vandamme for the moment. The next day, Vandamme renewed his assault, but Kleist’s Prussian Corps, which had been cut off by Vandamme, unexpectedly debouched on the Frenchman’s rear at Kulm. Vandamme was taken prisoner and more than half his large corps annihilated or captured—crushed between Allied forces advancing both up and down the narrow valley.99

On the northern front, Bernadotte, encouraged by Bülow’s victory, cautiously advanced toward the Elbe on Napoleon’s northern flank. Napoleon preferred to face his former marshal personally, but had to rescue Macdonald in Silesia. Accordingly, he replaced Oudinot with the aggressive Marshal Ney who immediately resumed the offensive toward Berlin. On September 6, Ney stumbled into a trap that Bülow laid for him north of the Elbe at Dennewitz. The fighting followed a characteristic pattern: energetic Prussian and Russian attacks with Bernadotte holding his precious Swedes in reserve. Nonetheless, the Allies won the battle, shattering Ney’s army in the process.100 Because of the fragility of his young conscripts, the durability of Napoleon’s corps and armies proved far less than that of earlier campaigns and at times it seemed that only he could rally the troops and put his humpty-dumpty armies together again.101

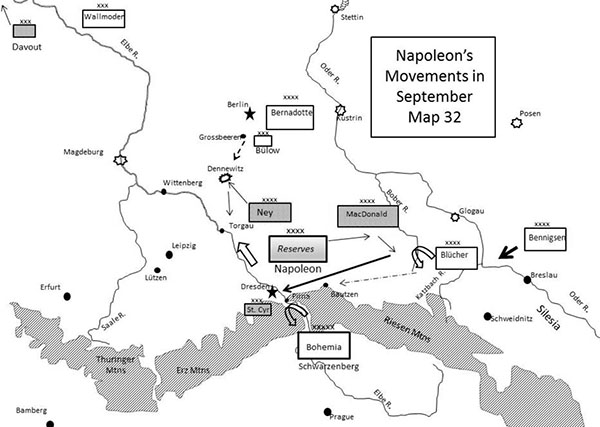

To appreciate Napoleon’s operational problem one only need follow his movements in September. Early that month he had moved from Dresden east to Macdonald’s army to halt, and hopefully defeat, the advancing Blücher. That general reacted by conducting a fighting withdrawal, correctly assessing that Napoleon and his operational reserves were once again with Macdonald. Napoleon then proceeded again to Dresden in response to St. Cyr’s call for help against the Army of Bohemia, which was again advancing after having recovered and reorganized. The Bohemian army had effectively split into two separate maneuver columns; one under Schwarzenberg and one under Alexander and his advisors. However, they had learned from Dresden and they separately withdrew once Napoleon’s presence was known. Napoleon considered pursing Alexander’s Russo-Prussian column, which was just out of supporting range from the Austrians, but he was again called away after the disaster at Dennewitz. Before he could deal with Bernadotte, he learned that Schwarzenberg was advancing again, this time to Pirna—and rushed there to contain the threat. He stabilized that situation only to learn of a renewed advance by Bernadotte to the Elbe. While Napoleon hurried north to deal with this problem he was further diverted to the east to again deal with Blücher. On September 22, he repulsed Blücher’s advanced guard in the vicinity of Bautzen (see map 32). Blücher again withdrew in response to Napoleon’s presence.102

In this manner the Allies prevented Napoleon from regaining the initiative. Napoleon’s comings and goings included a corresponding movement of his reserves. These marches and countermarches had the impact of another defeat by detracting from the strength of the Grande Armée. Thousands of Napoleon’s young conscripts dropped out of ranks, including in the Guard. Hunger also became a serious problem as the rapidly shifting moves outstripped Napoleon’s logistical arrangements. The Allies were well informed of Napoleon’s deteriorating situation. The ubiquitous Allied cavalry and raiding Freikorps obtained vital intelligence on the Grande Armée’s dispositions, intentions, and morale. Wilson referred to this lucrative information source as “an infinity of intercepted official and private letters.”103

In previous campaigns Napoleon had usually had the advantage in operational intelligence, but not in 1813. As in the spring phase, Allied raiders wrought havoc on Napoleon’s communications, causing him to detach major formations to deal with them. A few examples suffice to illustrate that this phase of the campaign included many, if not more, of the deep operations seen earlier that year. Blücher “harassed the rear of the French Army” using the Cossacks attached to the Russian corps in his army. One enterprising Cossack leader captured an entire French infantry battalion at Wurschen on September 2. These Cossacks also provided Blücher a wealth of intelligence including the condition and intentions of the Poniatowski’s Polish corps.104 Both Stewart and Gneisenau emphasize the importance of these operations on Bernadotte’s front. They included Cossacks, raiding Freikorps, and partisan activity. One such force under General Thielmann bagged 1,300 prisoners at Weissenfels, west of the Saale River. The booty also included dispatches relating “the most doleful details of the French Army.”105 Napoleon’s communications were so disrupted by this activity that he detached a cavalry division from the Imperial Guard under General Charles Lefebvre-Desnouettes to deal with it. On September 30, Lefebvre-Desnouettes ran into Schwarzenberg’s raiders led by the Cossack Hetman Platov raiding from the south. According to Stewart, the French had the worst of this encounter, losing more of their precious light cavalry in the process.106 Meanwhile, in the relatively quiet area of the lower Elbe near Hamburg, Clausewitz and Wallmoden destroyed a weak French division belonging to Davout on September 16 with their hodgepodge corps. Napoleon would receive no help from that quarter.107

Map 32 Napoleon’s Movements in September

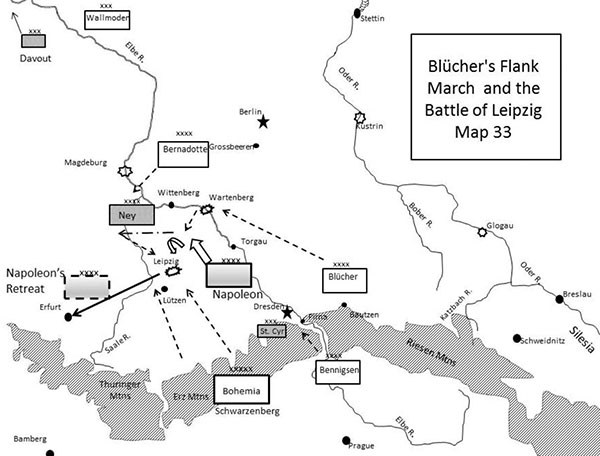

By late September, Bennigsen’s Army of Poland—60,000 fresh troops—had arrived in Bohemia and the time appeared ripe for an audacious coordinated move by the Sixth Coalition’s armies. Schwarzenberg requested Blücher join him for a concerted drive on Leipzig. Blücher instead recommended a flank march by his army to unite with Bernadotte and Schwarzenberg endorsed Blucher’s course of action.108 In a rare spirit of cooperation, Blücher and Bernadotte both proceeded to force the line of Elbe River. Bernadotte had established a bridgehead at Rosslau in the final days of September. Blücher’s appearance and crossing the Elbe took Napoleon and Ney completely by surprise. On October 3, Blücher’s lead corps under General Yorck conducted a successful opposed river crossing against Bertrand’s IV corps at Wartenberg further upstream (see map 33). A Prussian victory against a well-led French force did much to increase the momentum on the Allied side.109

Napoleon responded swiftly to this new threat. He marched on Blücher with the mass of his army, 150,000 men, leaving St. Cyr to hold Dresden with 20,000. This move exposed the instability of the relationship between Bernadotte and Blücher and also the general problem of synchronizing the movements of these massive armies. When Bernadotte learned of Napoleon’s approach, he pulled back, out of supporting distance of Blücher. Worse, Blücher had counted on Schwarzenberg to resume his offensive to distract Napoleon. The Army of Bohemia moved slowly in the south, allowing the Emperor a chance at an operational counterstroke against the now-isolated Army of Silesia. However, timely intelligence of Napoleon’s advance and excellent staff work by Gneisenau in developing a new line of operations prevented Blücher’s demise. Taking a page from Napoleon’s playbook, Blücher abandoned his line of communications with Berlin and dodged Napoleon’s counterstroke at Duben on October 9 by retreating to the west. General Gneisenau wrote:

Map 33 Blücher’s Flank March and the Battle of Leipzig

The offensive movements of the Allied powers…by their execution exposed their richest provinces to…the enemy and by attempting to throw themselves between Napoleon and France left close in their rear an army of 200,000 men, headed by an enterprising military genius and a number of strongholds well garrisoned while they themselves had no fortified place to serve them as a rallying point or as a position to rest upon.110

The stage was now set for the climactic battle of Leipzig. While Napoleon attempted to trap Blücher, Schwarzenberg executed the plan that the Tsar had thwarted in August. Emboldened by the arrival of Bennigsen, the main army group advanced on Leipzig. They received the good news on October 8 that the King of Bavaria had deserted Napoleon and joined their coalition and the Austrians had pushed forward into Bavaria to join forces with them. Napoleon now had two armies across his communications: Blücher’s and a combined Austro-Bavarian army under the Bavarian general Karl Philippe von Wrede. Napoleon lost the equivalent of 50,000 men with the defection of Bavaria and now realized that the 20,000 troops in Dresden were probably lost as well. Nevertheless, he concentrated his forces at Leipzig for the final battle—perhaps he could smash the Austrians before Blücher and Bernadotte arrived.

Leipzig was the largest battle in history until World War I, lasting four days and pitting Napoleon’s 180,000 troops against the Allies’ 200,000 (which grew by another 145,000 with the arrival of Bernadotte and Bennigsen on October 18).111 The Allies had 1,500 cannon, over twice Napoleon’s number. The battle was, in many ways, a microcosm of the entire fall campaign. All the elements were there on a tactical level—Blücher’s aggressive offensive into the northern suburbs around Mockern on October 16; Bernadotte’s belated advance that avoided combat the first two days of the battle; and the clash between Schwarzenberg and the Tsar over when and where to fight, finally conducting almost two distinct battles on either side of the Pleisse river, neither achieving success. The similarities were not accidental. The Allies just kept doing what they had done all along. While Schwarzenberg’s army group was attacked by the bulk of Napoleon’s army in the south and east, Blücher’s efforts in the north, along with a direct threat to Napoleon’s line of retreat by the Austrian corps of General Guylai, sealed the tactical victory by denying Napoleon the reserves he had counted on to exploit his local successes. The Army of Bohemia was pushed back, but it was not defeated. A relative lull in the battle occurred on October 17—analogous to the period of inactivity in September after Dennewitz. The Allies were content to bring up their operational reserves—the armies of Bennigsen and Bernadotte. With the arrival of these forces Napoleon realized he was only buying time to secure his retreat.112