THE ROYAL NAVY, NELSON, AND OPERATIONAL ART AT SEA1

This chapter looks at the commander of the British fleet at Trafalgar, Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson, baron of the Nile, and the campaign that led him to engage the French and Spanish combined fleet off Cape Trafalgar on October 21, 1805. As battles go, Trafalgar numbers among the most decisive in modern history and remains a monument to the superior training, tactics, organization, and—especially—leadership of the Royal Navy of the period. Nelson left a profound legacy to command of the sea that still affects how navies, and especially the United States Navy, operate today.2 Nelson’s career, both culminating and ending at Trafalgar, highlights basic truths of naval operations, truths that endure to this day.

Nelson’s “touch” codified for the Royal Navy and all other navies the guiding principle of centralized operational planning and decentralized, violent execution in combat. All of Nelson’s operations and battles highlight these simple principles, but none more so than his operational art masterpiece off Cape Trafalgar over two centuries ago. The campaigns of the Royal Navy, and especially of Nelson, leading to Trafalgar also reflect the role that naval strategy plays in war, especially between two empires whose sources of power differed so strikingly that the contest was supremely an asymmetric one—but this asymmetric character did not fully manifest itself until after French and Spanish sea power had been smashed over a period of 11 years, at which point it never recovered, despite the best efforts of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Ironically, the battle was not decisive in the ways some have characterized it—neither for its immediate impact on the general war in Europe in 1805 nor for its impact over the long term on strategic events.3 Simply, the Battle of Trafalgar was decisive because it both embodied the successful application of superior sea power by the major European maritime power and emphasized the necessary role that command of the sea by Great Britain would play in shaping the eventual defeat of Napoleon.

In and of itself the achievement of what Sir Julian Corbett referred to as general command of the sea through the mechanism of a decisive battle at Trafalgar was not sufficient to guarantee the British victory in their long struggle with France.4 Great Britain’s eventual victory relied on many other factors and agencies including the actions of Napoleon himself. However, command of the sea, based upon the Royal Navy’s blockade and its victories like Trafalgar, was a necessary condition without which Napoleon might not have been so frustrated that he felt compelled to counter British sea power with an ultimately self-defeating economic blockade—the Continental System.

In another sense, the road (or rather the cruise) to Trafalgar is far more interesting for the insights and explanations it offers on institutional culture, the importance of training and doctrine, and most importantly the British legacy of naval leadership and operational command and control at sea. The essence of this legacy encompassed centralized planning and decentralized execution and became the basis for modern U.S. naval doctrine.5 It will also highlight a command philosophy the U.S. Army of the present era labels mission command.6 This chapter will examine how Nelson prospered under this system at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent, executed the system as an operational commander in the campaign that led to his overwhelming victory at the Nile in 1798, and then how he ultimately helped bequeath it to those who followed after his death at Trafalgar.

* * *

The naval engagement off Cape Trafalgar is often presented as the culmination of an almost two-year-long naval campaign. In this sense it appears much in the same way as its land power counterpart, Austerlitz, an overwhelming defeat that decided not only the tactical, but strategic, issues that had been in play from the start. Nothing could be further from the truth. The great Chinese philosopher of war Sun Tzu (Sunzi) has said that “what is of supreme importance in war is to attack the enemy’s strategy”7 It is no exaggeration to say that the Royal Navy and British diplomacy—with not a little help from Napoleon himself—had undone Napoleon’s maritime strategy almost two months before Trafalgar. Nelson’s victory was not the reason that Napoleon cancelled his invasion of Great Britain in 1805—Napoleon’s inability to bring his fleet together to escort his invasion flotilla across the English Channel was instead the result of a highly sophisticated and aggressive blockade by the Royal Navy.

THE PROTAGONISTS

The chief players in the naval campaign of 1803–1805 were the French and Spanish navies on the one hand and the Royal Navy on the other. It is no exaggeration to say that the Royal Navy had established a tradition of dominance over both these navies during the preceding 100 years—having lost only a handful of engagements, most minor.8 During the period of the Wars of the French Revolution (1792–1802), the British had not only maintained this tradition but also improved upon it. In every major naval engagement during the period the Royal Navy not only won but also won decisively. The names of the great naval victories prior to Trafalgar roll off the tongue almost effortlessly:

As can be seen, the constant here was British—not just Nelsonian—excellence and dominance over the other major naval powers (and not just the French). The British strategic problem was to ensure that its enemies’ navies (composed of large ships-of-the-line or battleships) remained isolated and unable to mass superior force against the British.10 The best way to do this was with a blockade (or a preemptive attack as in the case of the Danes). If breakout and unification were attempted, the British actively sought battle to restore the blockade. Herbert Rosinski, a famous professor at both the German and American Naval War Colleges in the 20th Century, wrote that

In all narrow seas such as the Baltic, the North Sea, the Mediterranean or the West Indies, wherever fleets face each other at easy striking distance, there is and has been one and one way only for a naval commander to ensure the safety of his charges, and that is by sweeping his opponent from the board altogether obtaining against him undivided “command of the sea.” Nothing short of that will suffice.11

Rosinski concluded: “Nor is blockade merely a way to acquire ‘command’—by forcing the enemy to come out eventually and offer himself to battle—but it must be considered itself a form of command, because…it fulfills its function of excluding our opponent from the use of the sea [emphasis original].”12

J. C. Wylie, an American naval officer who was indirectly influenced by Rosinski, characterizes this sort of strategy as a cumulative strategy, and contended that attempts to employ what he called a sequential strategy against it are often inadequate, especially if the primary power is attempting to use land power against a sea power that does not share a land frontier with it.13 Cumulative strategies often employ protracted, distributed military operations whose cumulative result denies an enemy something valuable while often conferring to its practitioner something valuable in return. In the British case, their dominance at sea allowed them to deny their enemies the use of the sea for all but the most limited naval actions while at the same time retain the use of the sea as maneuver space against continental opponents. When Britain committed her small army in Spain and Portugal, this was a great advantage indeed (see chapter 6). These insights of the naval theorists apply to Napoleon’s attempt to counter Britain’s dominance at sea by invading Britain with his army and achieving the decision ashore, not at sea. But first he had to cross less than 30 miles of ocean to do it. This he was never able to do.

The key to British dominance lay in the combination of several factors. The first of these is training, or more appropriately, seamanship and gunnery training. This factor was closely tied to the second, which has to do with the British tendency to aggressively blockade enemy fleets in port and actively seek battle with adversaries at sea. Because of its operational policy of being a sea-going and active fleet, the Royal Navy naturally had highly developed skills in both navigation and seamanship. Additionally, the Royal Navy, and in particular, leaders like John Jervis, Horatio Nelson, and Samuel Hood, realized the advantage they had in being able to practice extensively with their guns in the unfettered environment of the open sea—a skill much harder to practice in the calm, cluttered waters of a port. Gunnery in that age involved an almost ballet-like level of orchestration and the British had managed to accomplish a superior firing rate over every other navy, but only through continual and relentless training and practice with live ammunition.

These skills, superior seamanship and gunnery, only got better as those of the enemy declined with the maintenance of a blockade. When battle did occur, the British often had more maneuverability and the enemy fleet often had the difficult choice of either accepting battle or running away. Oftentimes, British seamanship, particularly if the British ships had the advantage of being upwind (colloquially known as “having the weather gage”), made running away a difficult option.14 If battle was accepted, the opponents of the British now had to face, even if they had superior numbers, a struggle with an enemy that could outgun them and often fire three or more volleys of heavy cannon fire for every one of their own—a daunting prospect.

This disparity, almost asymmetry, in seamanship and gunnery led the Spanish and (especially) the French to develop countertactics over a period of generations. By the time of the French and Napoleonic wars, the French and Spanish were designing larger and often faster ships than their British counterparts. Speed enabled them to refuse battle more readily while the heavier weight of gunnery, it was hoped, would help balance the British rate-of-fire superiority. Further, the French, in particular, trained extensively on the accuracy of their long-range gunnery and focused on achieving what is referred to in today’s military terminology as a mobility kill. The French would aim at the British ships’ masts, rigging, and helm in order to disable their ability to close with them, or if closed, to get a maneuver advantage in order to negate British firepower in a slugging match.

In response, the British emphasized closing with the enemy fleet and boarding its ships if possible. Additionally, British gunners were trained to fire at the enemy hull in order to kill gun crews and personnel in preparation for boarding, and failing that, to sink the enemy vessel—but the goal was to try to capture the enemy vessel intact and then add it to the Royal Navy. The British also equipped their ships with the more destructive guns of the carronade type, which were meant for use at close range and used a composite load consisting of a large round shot and a keg filled with hundreds of musket balls. Nelson’s flagship often carried two of the largest type of carronade, which fired a 68-pound solid round shot combined with a keg loaded with 500 musket balls—clear the decks for action indeed! British long-range gunnery was thus not as excellent on its ships of the line (battleships) but rather on its smaller screening ships such as frigates and brigs.15

Finally, the issue of leadership and morale must be addressed. Despite the draconian discipline in the Royal Navy, much of which would mutiny at Spithead in the spring of 1797, morale in the Royal Navy was often superior to that of its opponents. Clearly this was the case during all of Nelson’s victories. This morale advantage was the result of a tradition of maritime victory and uniformly competent, and often superb, leadership. Another explanation can be found in the fact that the Royal Navy, despite its name, was not so much the King’s Navy as it was Great Britain’s navy. Just as the French Revolution had given the people of France a national army, so had the long evolution of the Royal Navy after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 given Great Britain a national or people’s navy. The Royal Navy was a strong national institution by the time of the French Revolution.

Not only this, but as an institution the Royal Navy’s officer corps consisted of a meritocracy, just as the French army had become after the Revolution. A career as an officer in the Royal Navy, while still related to patronage and privilege, was open to talent. The weak, stupid, lazy, and incompetent were, as often as not, weeded out by the physically harsh and difficult life. The officer corps for the Royal Navy came from a broader segment of the British population than did that of the British army—which was still very much the King’s army even though it was no longer called the Royal Army (because it had revolted against the King during the English Civil War). One example will suffice—Nelson. Horace, later Horatio, Nelson was squarely from the middle class, being the son of an Anglican preacher (parson). His title was earned in battle through merit and not hereditary.16 Napoleon employed precisely the same system once he became emperor, creating a nobility of merit.

NELSON’S APPRENTICESHIP IN OPERATIONAL ART—THE BATTLE OF CAPE ST. VINCENT

As we have seen, by 1797, the War of the First Coalition was going very badly for Austria, Great Britain, and their other minor allies. Prussia and Spain had left the war and in 1796 the Spanish decided to see if an alliance with the French might help them lay British pride low via the mechanism of sea power as well as lingering Spanish resentment of Britain’s expansion of her oversea empire, often at Spain’s expense, whether she was a neutral or an ally. Recall, too, that Spain had joined France during the American War of Independence, leading to her acquisition of Louisiana. More might again be gained since it appeared Britain was on the losing side. Spain’s belligerence could not have come at a worse time for Britain. With France triumphant in Italy and threatening gains in Germany, the combination of the Spanish, French, and now Dutch fleets might finally offer Britain’s allies the chance to combine and perhaps escort an invading armada across the English Channel.

Britain had held her own at sea, with the famous Admiral Richard “Black Dick” Howe punishing the French, in the battle on the “Glorious First of June.” But French sea power remained, as Sir Julian Corbett termed it, “in being.” If it could combine with new allies and the newly captured Dutch fleet, it might yet prevail. The Royal Navy had a huge job in 1797; it had to watch the French ports and fleets as well as those of Spain and the low countries where the Dutch fleet was gathered. It was actually a greater crisis than was to occur during the days of Trafalgar. However, British operations hinged on aggressive blockade and engagement. As Rosinski has written, the goal was to “sweep” the enemy fleet “from the board.” However, the Royal Navy had to remain ever vigilant, on patrol, and constantly seeking an opportunity to catch the enemy unawares if they left port. The British mariners had reached a point that if offered an engagement, even if outnumbered, they would engage in battle. Such battles often had inconclusive results because all too often the French and the Spanish, in their superior ships, either returned to port or ran away—they could refuse battle in most situations unless caught by surprise. It was just this situation that offered the commander of the British Mediterranean Fleet, Admiral Sir John Jervis, the chance to catch the bulk of the Spanish fleet. Jervis found the Spaniards escorting a convoy of mercury needed in Spain’s South American colonies to process silver at sea and precipitated an engagement of Cape St. Vincent in Portugal in February 1797.

Jervis was the ideal pick to command the fleet watching the Spanish. He had fought with General James Wolfe at Quebec, was aggressive, and a keen judge of character and talent in subordinates. Also, most importantly, when he recognized talent in his subordinates he was very enlightened about developing it and then delegating authority to the men he trusted—a key attribute of the philosophy of mission command.17 Jervis’s presence “transformed the spirit of the Mediterranean Fleet.” When Captain Horatio Nelson, the second youngest British officer ever to make post captain, was assigned to his fleet, Jervis immediately took to the fiery, intelligent young officer. Jervis also promoted Nelson to the most senior rank possible for a captain, commodore, since Nelson now routinely commanded more ships than just his own. As a result, Nelson would command the rear division of Jervis’s fleet, flying his flag aboard the battleship HMS Captain (74).18

As discussed, Jervis took over the Mediterranean Fleet at a critical juncture. With powerful Spanish and French fleets in play, the British pulled out of the Mediterranean as the Austrians suffered repeated blows from Bonaparte in Italy and pressure on the Rhine in early 1797. The war now assumed a principally naval character and Jervis’s fleet, including Nelson, now concentrated solely on the Spanish threat to combine with the French and ferry victorious French legions across the channel. However, a truce with Austria that would release French troops was still two months distant (see chapter 2).19

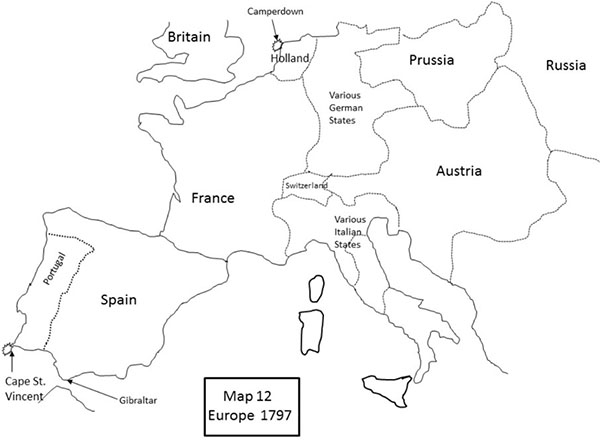

One of the last groups of British ships to leave the Mediterranean belonged to Nelson. Temporarily in command of two captured French frigates (La Minerve and Blanche), he had miraculously sailed through the main Spanish fleet at night in the fog. He then proceeded directly to Admiral Jervis whom he found on February 13, 1797 off Cape St. Vincent on the Portuguese coast (see map 12). He gave Jervis the critical news that the Spanish fleet had entered the Atlantic. The next day, Jervis made contact with the Spanish ships under the command of Admiral Don Jose de Cordoba. Cordoba outnumbered Jervis by almost 2–1 in battleships (27 to 15). Jervis formed line of battle and made straight for the approaching Spanish fleet, saying “The die is cast and if there are 50 sail of line, I will go through them.” This famous utterance highlights the British method of seeking battle in almost any situation except the most unfavorable. The Spanish fleet was still divided into two groups and trying to mass, one to windward (upwind) and one leeward (downwind) from the British. Nelson with his good friend Cuthbert Collingwood brought up the rear in Captain and Excellent (64).20

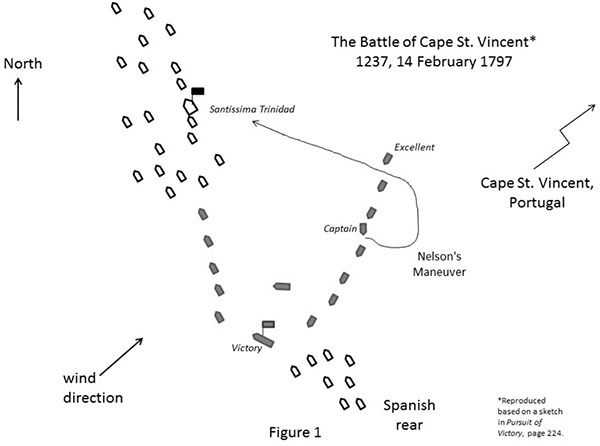

At the key moment in the battle, Nelson’s portion of the line was closer to the Spanish than the head of the column as Jervis took his ships into a turn to keep the Spanish divided. It was at this moment that the British style of mission command evidenced itself. Nelson, disobeying the famous standing battle orders, wore out of the line and sailed straight for the middle of the Spanish column. This was where the most powerful Spanish ships were positioned, including Cordoba’s massive flagship Santissima Trinidad (140). Nelson’s aggressiveness and ability to act independently had been known in the fleet, but now they were on display for all to see. Jervis aboard the flagship Victory (100) saw Nelson engage seven enemy battleships with his one. He approved the action and signaled Collingwood aboard Excellent to support him. He then sent out the same signal to the remainder of his ships that Nelson himself sent from Victory at Trafalgar, “Engage the enemy more closely”21 (see figure 1).

Map 12 Europe 1797

Jervis’s signal was the essence of decentralized execution, leaving to each captain his choice on how and which Spanish ship to approach. Nelson’s ship should have been obliterated as he endured the close but inaccurate fire of the Spanish. Elated by close combat, he rammed San Nicholas (80), which had become fouled close aboard with another Spanish battleship San Josef (112) and boarded her. Nelson personally led the boarding party aboard San Nicholas and took her in violent close quarters fighting. The next action he took was unprecedented and sealed his fame—with San Josef still close aboard, he continued with his boarding party across the captured ship and boarded and took the larger ship from his new prize. Meanwhile, Collingwood had pounded three more Spanish ships to pieces and taken one of them. Of the four Spanish ships taken, two belonged to Nelson. Cordoba’s flagship, the gigantic Santissima Trinidad had struck her colors, too, but was rescued by several other Spanish ships before the British could board her. Many of the Spanish ships that survived were badly damaged and thousands of valuable gun crews and sailors had been killed by the deadly British fires. The Battle of Cape St. Vincent highlights how absolutely decisive general engagements at sea can be, although they are much rarer than land battles because either belligerent often can refuse battle. In fact the Spanish were attempting to do just that when Nelson made his famous maneuver. It was a spectacular victory and earned Nelson a knighthood (of the Bath) and promotion to rear admiral. The King made Jervis Earl of St. Vincent in honor of the great victory, and Spanish sea power remained cowed until peace was signed in 1802 at Amiens.22

Figure 1 The Battle of Cape St. Vincent* 1237, 14 February 1797

There still remained French and Dutch fleets to fight as well as the Nore and Spithead mutinies of 1797. So great was British ascendancy that the Dutch fleet remained in port during the worst moments of the mutiny when Admiral Adam Duncan kept watch with two ships, deceiving the Dutch by signaling a fleet over the horizon that was not there.23 Once the mutinies were resolved, Admiral Duncan managed to demolish the Dutch fleet as a threat at Camperdown (October 11, 1797). This was a victory nearly as great as Trafalgar with the British capturing 13 enemy vessels and emphasizes the general excellence of Britain’s operational commanders at sea across the spectrum. Nelson, in the meantime, had been sent by Jervis on his first independent assignment as an admiral to seize the port of Santa Cruz on Tenerife in the Canary Islands. Disaster resulted. He made the classic mistake of underestimating his foes and overestimating his own power to prevail in an amphibious assault. He led his landing force into an ambush and Nelson almost bled to death when his right arm was shattered by a musket ball and later amputated.24 The wound did not heal properly and Nelson returned to England as an opium-sedated wreck who believed his career had ended with the loss of his right arm, writing to a friend, “I am become a burthen to my friends and useless to my Country.”25

NELSON IN OPERATIONAL COMMAND AT THE NILE

Although 1797 had seen Austria withdraw from the First Coalition, the British had calmed the worst fears of disaster by decisively defeating the fleets of France’s two allies—the Spanish and Dutch. With two fleets “off the board,” there still remained the most dangerous fleet of all—the French. Napoleon Bonaparte had proposed to the Directory that the best way to attack Great Britain was to threaten her lines of communication through the Levant with her Indian colonies, the crown jewel of the empire. To do this he planned to take an army composed primarily of veterans from his Italian campaign and sail to Egypt where he would land and establish a French colony, placing him astride the quickest British route to India. It was an ambitious plan, but in order for it to work the French had to slip by the Royal Navy. The Directory wanted to get rid of the political threat posed by Bonaparte and agreed to dispatch him with over 44,000 troops and the entire French Mediterranean Fleet to accomplish this task.26

One finds all the elements of mission command in Nelson’s pursuit and annihilation of the French fleet that escorted Napoleon to Egypt, although his goal had been to sink Bonaparte’s army while still embarked on its transports. Now in command of his own squadron, Nelson embodied for the Royal Navy the principles we have discussed but now with the new dimension of a command philosophy that empowered the tactical and operational initiative of his subordinates. His subordinates in turn relied on the teamwork and initiative of their crews. Similarly, we find that Nelson’s commander, Admiral John Jervis, also exercising operational mission command in how he “controlled” his talented subordinate. The campaign of the Nile thus demonstrates how the Royal Navy’s command philosophy at all echelons of command was a profound force multiplier. The period prior to the actual engagement in August 1798 has much to teach us about what Nelson himself called the “The Nelson Touch.”27

Nelson recovered rapidly after his disaster at Tenerife under the close care of his wife Fanny, and, less one arm, he returned to command. Nelson raised his flag on Vanguard (74) in late March 1798 and set sail for the Gulf of Cadiz. Admiral Jervis’s confidence in the younger admiral was unbounded. As soon as Nelson arrived to join the fleet on blockade duty off Cadiz, Jervis detached him on an independent command with a small squadron to enter the Mediterranean and keep an eye on the French fleet in Toulon. Jervis forwarded another 11 ships of the line to Nelson in May 1798, an unprecedented command for such a junior admiral, which caused much grumbling among the many admirals senior to him without sea command. Jervis instructed Nelson to stop Bonaparte’s invasion force, suspected to be bound for Egypt. Nelson’s plan was simple, to intercept the invasion fleet and destroy Napoleon and his army at sea.28

Meanwhile, Bonaparte’s invasion armada had set sail from multiple Mediterranean ports that May, but unknown to Nelson it proceeded first to Malta, which it captured on June 10, and then proceeded leisurely to Egypt. Bonaparte was extremely lucky, as a fortuitous storm damaged Nelson’s flagship and delayed his pursuit, while at the same time, the Malta diversion confused things a bit more. The slowness of the lumbering French armada probably saved it from being intercepted by Nelson at sea. Bonaparte landed at undefended Aboukir Bay on July 1–3 and then advanced and defeated the local Mameluks at the famous Battle of the Pyramids (July 21).29

Jervis’s faith in Nelson was rewarded, but not immediately. Nelson’s impatience almost did him in, but he was tenacious in pursuit of his quarry. As noted, on May 19, Bonaparte, escorted by the French fleet under Admiral Francois-Paul Brueys, had departed while Nelson collected his squadron after the storm. Nelson was desperately short of frigates (he had only three) to provide him intelligence and decided Napoleon’s destination must be Naples. Bonaparte instead went to Malta and conquered it, as we have seen. Nelson realized his mistake and decided that Napoleon’s next objective was Alexandria, Egypt. He rushed off arriving in the vicinity of Alexandria on June 29 and found nothing. Brueys and Napoleon had taken a different route north of Crete and sailed far slower than Nelson imagined. Nelson missed a great chance by not waiting off Alexandria, second-guessing himself and sailing north to Turkey. While Nelson sailed north, the French arrived and began to debark their troops. It seemed that Nelson had lost the game of cat and mouse and missed a golden opportunity to destroy both a French army and a French fleet.30

Nelson, like all great operational artists, did not give up. Off Sicily he learned of his mistake and doubled back as fast as his ships could sail to Alexandria. Late on August 1, he arrived and found the transports empty, but Brueys’ 13 battleships and many smaller warships were still anchored close in to shore in the shallow and treacherous waters of Aboukir Bay. Brueys had unwisely sent half of his gun crews ashore to assist Napoleon with the land campaign. He also thought himself unassailable so close in to the shore. The final nail in his coffin was the late hour of the day. Surely Nelson would not attack in such dangerous waters with the onset of night? Nelson, demonstrating his intuitive grasp of the weakness of the French, instantly decided to attack.31

Nelson had planned in advance for this moment, and so made the decision almost instantaneously to attack the vulnerable French ships. To understand how he had operationally prepared one must go back many years. First, Nelson actively fought for the welfare of his sailors from the beginning of his career until his death in combat in 1805. The sailors who served under him knew this, and their support generated a confidence in his decision-making and leadership. Second, Nelson’s rapid and seemingly “snap” decision-making in combat was not so much luck or intuition, although these certainly played a role, but more often “achieved by decisions made in the quiet of his cabin.”32 In other words, Nelson prepared himself intellectually at all times for decision-making, tactical and otherwise, through reflection during the often lengthy downtime that one experiences at sea (something the author of this book can attest to).

For this battle, Nelson had the complete confidence of his 15 battleship captains and this was rewarded by his confidence in them. Nelson also had the advantage of probably having some of the best captains, ships, and crews in the entire Royal Navy under his command at this battle. The 10 battleships that St. Vincent sent him under Sir Thomas Troubridge—who had served as a midshipman with Nelson—were later referred to by Nelson himself as, “the finest Squadron that ever sailed the Ocean.” He also knew most of their captains personally, having served with most of them in combat, knowing only three by reputation alone. He soon remedied this deficiency by proactive efforts. After barely missing the French at Alexandria and as he sailed about looking for them, Nelson instituted the policy of bringing his captains individually aboard the flagship to mess with him and to share their ideas with him and he with them. In the words of a contemporary observer, “he would fully develop them to his own ideas of the different and best modes of Attack…they could [as a result] ascertain with precision what were the ideas and intentions of their Commander without the aid of further instructions.” This, in short, epitomizes operational mission command, especially in a battle at sea where directing one’s subordinate in the heat of an engagement often proved difficult if not impossible.

On June 22, Nelson brought his four most senior captains aboard Vanguard and asked them for their opinion on which way the French might have gone. They voted for Alexandria—they were all thinking along the same lines as Nelson but this shows he trusted in their judgment. On July 17, just before turning the squadron back to Alexandria, Nelson brought all 14 captains to the flagship to ensure commonality of purpose and a shared understanding for what he expected from them in the battle he was convinced would occur soon—if he could only find the French fleet. Nelson’s only real “error” prior to the battle involved his reluctance to formally appoint a second in command since he was actually junior to several of them and did not want to upset the cohesion of the team in making one of them the object of jealousy by the others he did not pick. Perhaps he was thinking that if he were killed (a distinct possibility given his habit of being in the thick of battle), they would all continue to do their duty out of a sense of obligation to him rather than have their own fighting trim diminished by petty jealousy between themselves after he was gone.

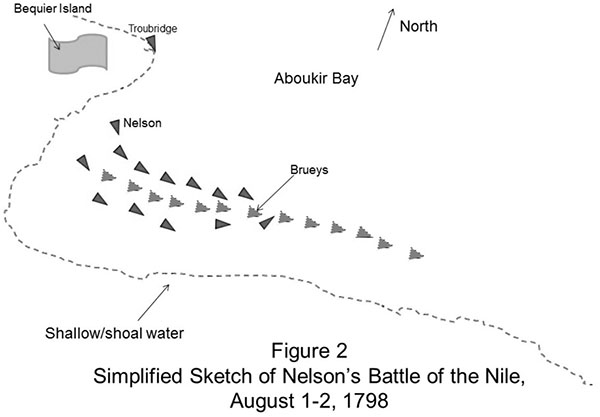

At the time of the battle, Nelson had 14 battleships to 13 of the French, but the French had the heavier weight of gunnery (bigger ships and bigger guns). Upon sighting the enemy fleet Nelson issued signals 53 and 54 from the Royal Navy’s official signal books. The first simply alerted all the crews of his fleet to “prepare for battle.” The second directed them to be ready to anchor at a moment’s notice by the stern of the ship, an evolution requiring the rigging of a very large anchor and cable at the rear of each ship since anchoring by the stern was not something the ships were normally rigged for. It meant, as well, that each captain and his crew would have to do this under enemy fire, during which time they would be unable to fire their guns while at the same time would have to furl (take down) the full load of sail while sailing in shallow waters. Obviously, a cohesive team and shared understanding had to be present for this unprecedented tactic to be executed properly. Its purpose was to suddenly stop the forward progress of the British ships so they could fire a full broadside into the French ships without waiting for the ship to stop moving, as one would when anchoring by the bow. Each captain, and more importantly their crews, knew exactly the risk inherent in this maneuver and welcomed it. Nelson’s ships did not waste time signaling an acknowledgment or request back to Nelson for any further guidance. This was because they all knew their commander intimately, they knew their ships, and they knew that their enemy was unprepared—not only for battle but especially for this unprecedented maneuver. Nelson intended for this to take place in a single battle line between the French line and the open sea.33

The second, we might say graduate, level of this decentralized-type command emerged in what the captains then did on their own initiative. Nelson effectively gave his captains free rein when he sent the signal to his ships at 1730 hours (5:30 p.m.) “to form line as most convenient,” leaving it to their discretion how to approach the French fleet since he was in the rear aboard Vanguard. The execution was not without some hiccups, such as when Captain Troubridge on Culloden ran aground just north of the French, but this also served to let the ships behind know where not to sail. Several ships performed the anchoring maneuver inexpertly and paid with heavy casualties as a result of being out of position. But most of Nelson’s other captains served him well. The aggressive captain of the lead ship Goliath was Sir Thomas Foley. He instantly made the decision to go behind the first French ships and inside the French line. About half the other captains followed his initiative while Nelson signaled the remainder in the last bit of daylight to follow Majestic (74) on the northern side (see figure 2). This resulted in a double envelopment of the French ships in the first part of the line. Their mates further down the line were anchored solidly and could not help them.34

To make matters worse, some of the French ships had not strung cable between their neighbors to counter the known British tactic of “breaking the line” and then shooting longitudinally into the aft and bows of the anchored French ships. Again, taking local tactical initiative, several British ships performed this maneuver, especially Leander (50) and Alexander (74), dealing out further bloody devastation against the hapless French ships that were their targets. The night sky of Alexandria was lit up with the din and spectacle of burning French ships as Nelson pounded the French fleet to pieces while his ships proceeded down the line. Brueys’ flagship L’Orient (120), surrounded on two sides in this manner and the second largest battleship in the world, blew up after absorbing incredible punishment, including combustible grenades that Captain Alexander Ball of the Alexander had specially prepared to set French ships afire if he could get close enough. Only Admiral Pierre Villeneuve in the rear escaped with two battleships and two frigates. The rest of the French fleet—including 11 battleships—was destroyed or taken. Nelson, in the thick of the fighting as usual, received a nasty head wound. 35

Figure 2 Simplified Sketch of Nelson’s Battle of the Nile, August 1-2, 1798

Nelson had not lost a single ship and had suffered fewer than 900 casualties, most of these in ships that had mishandled the anchoring maneuver. He had effectively checkmated Napoleon’s strategy by stranding his army in Egypt. When Napoleon attempted to fight his way through Ottoman (Turkish) territory in order to gain passage to Europe or even India, he was confounded again by another naval officer, Sir Sydney Smith, who successfully defended the Turkish fort at Acre, forcing Napoleon to return to Egypt. Later that year, Napoleon slipped through Nelson’s blockade, abandoned his army, and returned to France where he established the Consulate with himself as first consul.36

THE NAVAL CAMPAIGN OF 1803 TO AUGUST OF 1805

The renewal of war between Britain and France, which most accounts begin with the year 1805, actually began in May of 1803 with a rupture over multiple unresolved issues. These stemmed in part from the flawed Peace of Amiens signed some 15 months before.37 On May 14, 1803, Great Britain declared war on France. Nelson was appointed commander in chief of the Mediterranean Fleet assigned to watch the squadron of Admiral Latouche-Treville the same day. Two days later, he boarded Victory (100), Jervis’s flagship at St. Vincent, and hoisted his flag.38 He was back with the fleet he loved and that loved him.

Napoleon’s strategy remained focused on gaining temporary command of the narrow seas of the English Channel in order to cross with an army of over 150,000 of the finest troops in Europe (Le Grande Armée). However, gaining command of the sea meant that the French navy must defeat or evade the Royal Navy—or perhaps deceive it and draw enough of it away—so that the invasion would have a reasonable chance of success. Simply put, the French strategy relied on an invasion that would enable Napoleon to dictate terms to a conquered British nation. The British problem was now exacerbated by the reemergence of a capable Spanish fleet, which upon Spain’s declaration of war against Britain in December 1804 was added to that of the French. British strategy remained as it ever was, to blockade the French and Spanish navies in their ports so they could not escort an invasion flotilla.39

On August 26, 1805, Imperial French Headquarters issued orders to the Grande Armée (now some 210,000 troops) to turn east and abandon its positions along the English Channel for the invasion of Great Britain. Napoleon’s decision to do this had occurred even earlier. Why did Napoleon abandon his attempt for a decisive conclusion to his two-year-old war with Great Britain by direct invasion? Since Trafalgar was some two months distant in the future one can categorically state that naval defeat was not the reason. The Royal Navy’s blockade was the decisive element that defeated Napoleon’s strategy—given its art and elegance it was surely a military operation that the subtle Sun Tzu would have appreciated. The British strategy accomplished its successful result not with a phantasmagorical naval battle for the ages, but rather with the slow and steady application of superior sea power over a period of two years. This in turn was augmented by the relentless offensive energy of admirals like Nelson, who literally hunted any French or Spanish ships that managed to slip by the blockade into the open sea. In the end, it was a combination of the systematic effects of the British blockade combined with the superior training, tactics, and leadership of the Royal Navy that accomplished this result.

One must give both the French navy and Napoleon due credit for operationally creating the conditions that might have given the invasion force a fighting chance. The great operational problem for the French and Spanish fleets was their inability to mass due to the blockade. If the majority of the separate fleets at Brest, Toulon, Cadiz, and other points could only combine, they might be able to defeat, or at least drive away, the British fleet guarding the English Channel. The only way to do this would be to try to split that fleet and then during the period of separation enter the Channel and do battle with the remainder. This would be difficult, since the British had large squadrons of battleships blockading all the major ports under a number of very competent admirals, Nelson, Cornwallis, and Keith in particular. The main British force—the Channel Fleet—was not even under Nelson but under Admiral William Cornwallis with another strong squadron under Admiral Keith in reserve. Nelson’s task was to watch the French under Admiral Villeneuve, who were bottled up in the Mediterranean port of Toulon on the south coast of France. Villeneuve had replaced the more competent Latouche-Treville who had died in August 1804. Latouche-Treville’s active defense strategy involved a war of attrition against Nelson’s blockading squadrons by sailing out to sea and then dashing back to port, hoping to wear down his enemy while still maintaining the seamanship and morale of his crews. Unfortunately, the French admiral had a bad heart and died suddenly, although it is not certain that Napoleon would have left him in command given his caution and his preference for a protracted “fleet in being” defense whose results were not guaranteed. In any case, he kept the British on pins and needles for over a year and probably enabled Villeneuve’s later success in slipping past Nelson’s blockade to join the Spanish.40

Admiral Pierre Villeneuve had been in conflict with Nelson before—off the Nile. Recall that Villeneuve’s Guillaume Tell was one of only two battleships to escape Nelson after the battle. Upon the resumption of hostilities in 1803, Villeneuve was in command of a squadron in the West Indies. He later commanded the French squadron based out of Rochefort on the French Atlantic coast. He was actually junior to Admirals Denis Decrés and Joseph Ganteaume. Ganteaume had the main French fleet at Brest. However, despite Villeneuve’s junior status and deep respect and perhaps fear of Nelson, he was to be the primary instrument for obtaining command of the sea in the English Channel.41

Napoleon needed a way to diminish or remove the British naval dominance from the Channel and devised a daring plan to divide the British fleet. Nelson and the Admiralty believed that Napoleon would again try to disrupt their lines of communication to their key East Indies colonies by attacking either Malta or Egypt (as in 1798) as one way to distract the Royal Navy. Instead, Napoleon ordered Villeneuve to break out of Toulon and go west to threaten the British colonies in the West Indies, a tactic the French had employed with some success during the American Revolution. En route, Villeneuve would combine his fleet (11 battleships and 6,400 troops) with a Spanish fleet under Admiral Carlos Gravina. The French emperor hoped that Nelson would follow Villeneuve across the Atlantic. If all went well, Villeneuve would combine his force with whatever other French ships had broken out from Atlantic ports and made it to the Indies. In the meantime, the main fleet under Ganteaume would break out and proceed into the channel to cover the invasion. If Ganteaume did not escape on his own, Villeneuve’s return with a combined Franco-Spanish fleet might be the agent for concentration of all three fleets, which would then press into the Channel for either battle or to cover the invasion, whichever occurred first. Unfortunately, Napoleon never sat his admirals down and explained the entire scheme to them, so that they often only knew the bare minimum of the details only after they had put to sea and opened their sealed orders. This was a recipe for disaster.42

Napoleon’s plan, of which there were more than eight iterations, had many moving parts and relied on almost perfect synchronization between the various French and Spanish squadrons in order to mass in the correct place and at the correct time. It also relied on Nelson taking the bait and proceeding to the Indies in hot pursuit of Villeneuve. It came very close to success in achieving the desired concentration. By early 1805, many of the British ships had been at sea for over a year and were in need of repair and their crews were in need of rest. It was at this opportune time that Villeneuve made his first attempt to execute Napoleon’s instructions. However, foul weather and the poor condition of the French ships and crews forced Villeneuve to return to Toulon. However, Villeneuve’s first attempt had caused Nelson to make a grave error. He assumed that Villeneuve was sailing for Alexandria in Egypt as Napoleon had done in 1798. By February 7, 1805, Nelson and his 13 ships of the line had arrived off Alexandria, but they were in very poor condition. This was not only a result of their lengthy time at sea since the outbreak of war but also due to the Admiralty’s failure to perform hull maintenance on many of them during the respite offered by the Treaty of Amiens.43

When the French fleet was not found, Nelson pressed back across the Mediterranean, still convinced that Villeneuve’s objective was Egypt. It was because of this notion that Villeneuve’s second attempt to break out and join with the Spanish succeeded. Nelson had precious few frigates to watch for Villeneuve and he chose to use these to watch the routes to the east and only one route to the west. Villeneuve cagily slipped out of Toulon on March 30 and then passed north of the Balearic Islands. By April 9, his slow-moving ships were in Cadiz and had combined with the Spanish. This combined fleet of 18 battleships and over 5,000 troops now proceeded to Martinique in the French West Indies, arriving a month later. Nelson had again proceeded east to pursue a phantom French fleet he thought was bound for Egypt. He was in the Central Mediterranean when he finally received word that Villeneuve was bound for the West Indies. Nelson immediately gave chase and by May 4, 1805, he was at the Strait of Gibraltar taking on stores for an Atlantic crossing. Villeneuve had a month head start and it seemed almost certain that Napoleon’s plan must work. It was now that British seamanship and French indecision played their fateful roles. Villeneuve had secondary orders to attack Barbados but waited until June 9 to double back across the Atlantic and join up, hopefully, with Admiral Ganteaume to cross the Channel.44

Nelson and his fleet were in the meantime accomplishing the impossible, pressing across the Atlantic in three weeks in their leaky undermaintained ships—an act of incredible seamanship. They shaved off critical weeks from Villeneuve’s head start. In fact, Nelson arrived on June 4 and was already hunting for Villeneuve. Once Villeneuve learned of Nelson’s presence, he set course for the Bay of Biscay and a hoped-for juncture with Ganteaume. Although this was probably the right strategic move, it lowered the morale of the Franco-Spanish fleet, which only saw that it was again running away. Nelson soon learned of Villeneuve’s departure and immediately dispatched the brig Curieux across the Atlantic to inform the Admiralty of Villeneuve’s impending arrival, perhaps in the Channel itself. Luckily, the Curieux ran into the combined fleet and was able to report to the British Admiralty that Villeneuve was indeed heading for the Bay of Biscay. The British high command reacted decisively in positioning over 600 ships of various sizes to meet the Franco-Spanish threat. Again, superior British seamanship had prevailed. Curieux also passed word to the Admiralty of Nelson’s own return (He had provisioned and set sail about a week after he dispatched the Curieux.) It was at this point that Nelson temporarily disappeared from the story.45

With Nelson’s intelligence in hand, Admiral Cornwallis raised his blockade of Brest and dispatched a squadron of ships under Admiral Sir Robert Calder to intercept Villeneuve. Villeneuve collided with Calder in the fog off Cape Finisterre (northwestern Spain) on July 22 in a tactically indecisive action. Its results, however, were strategically decisive. Superior British gunnery caused the surrender of two French ships. This was enough to cause Villeneuve to pull back into the Spanish port of Vigo. Ganteaume, unaware that Cornwallis had raised the blockade, serenely remained in port so that by late July any hope of a juncture with Villeneuve was gone. Ironically, Calder was criticized for his strategic victory because he had not captured or sunk more enemy ships. He bore the stigma of having not destroyed Villeneuve’s fleet for the rest of his career.46

Not long after these events, Nelson, again sailing his fleet across the Atlantic more quickly than a French frigate might, returned to the European waters. He had been constantly at sea for over two years, sailing over 10,000 nautical miles in 1805 alone. Villeneuve and Gravina remained united but blockaded in Cadiz (to which they had moved on August 20) and Ganteaume remained under blockade in Brest. Nelson now took the opportunity to try to repair his worn ships and rest his tired seamen while maintaining vigil off Cadiz, keeping his fleet just over the horizon (as was his habit) and maintaining watch with a string of frigates.47

Finally, Napoleon’s aggressive actions in Europe had aroused jealousy and resentment among the other great powers of Europe. Napoleon’s aggrandizing actions in no small measure contributed to the achievement of a long-term goal of British diplomacy—the formation a Third Coalition composed of Austria, Russia, Great Britain and several lesser powers to renew the continental conflict with France [see chapter 5]. Had this coalition not formed, Napoleon might have remained with this army along the English Channel. However, he now had threats to his strategic backdoor, as it were, and completely recast his strategy in the light of new realities. The long blockade operations that stymied Napoleon’s strategy vis-à-vis Britain had contributed substantially to the favorable political environment of 1805. Nevertheless, the Royal Navy did not rest on its laurels, and Nelson, especially, planned for the destruction of Villeneuve’s Franco-Spanish fleet.48

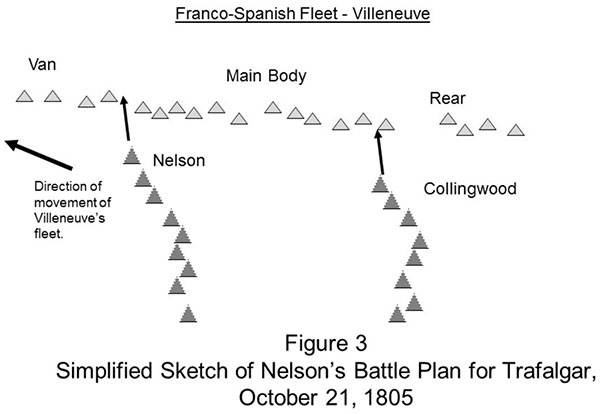

As he did before at the Nile, Nelson prepared carefully for battle. When he rejoined his fleet blockading the Franco-Spanish force off Cadiz in late September 1805 he immediately convened a meeting with his subordinate commanding officers onboard Victory. He had already sent a letter to all of them explaining his intention to attempt to trick Villeneuve into battle. Once battle was joined, he would attack with two columns of ships that would break the traditional battle line of the enemy into three groups: the van, the main body, and the rear. Of these groups, those in the van would be effectively unavailable for the initial phases of the fight since they would have to sail back into the wind (tack) to reach the battle, by which time Nelson intended to have defeated the other two groups of ships.

In this way Nelson would rectify any numerical superiority that the enemy might have as well as deny him the ability to refuse battle with the entire fleet (see figure 3). All of this was explained in further detail by Nelson in person aboard his flagship to his captains, usually at dinner. It was a supreme example of a commander making known his intent to his subordinates in a collaborative and accessible fashion. It bears many parallels to a similar dinner that Napoleon held with his marshals and officers on the night before Austerlitz.49

Figure 3 Simplified Sketh of Nelson’s Battle Plan for Trafalgar, October 21, 1805

Nelson reiterated his intent in a famous memorandum written after his conferences and dinners aboard the Victory on October 9. Nelson’s memorandum emphasized several keys to the victory that have already been mentioned: superior gunnery and seamanship. Nelson outlined for his captains that he did not plan to form new lines of battle once Villeneuve’s fleet was sighted. In order to take advantage of superior British seamanship and trap Villeneuve he intended to waste no time forming up for battle but rather his ships’ positions—what was called their order of sail—would also be their order of battle. This would give him speed. Second, he wrote that “no captain can do very wrong if he places his Ship alongside that of an Enemy.” This instruction emphasized his belief that his fleet was ship for ship and man for man superior to that of the French and Spanish. It was also written to emphasize to his captains that if signals could not be seen from the flagship then they had complete autonomy to engage the enemy as they saw fit. Nothing Nelson ever wrote has emphasized the principle of decentralized execution as cogently. Finally, his intention was no mere victory but rather “annihilation” of the entire enemy fleet.50

Nelson now turned his mind to the battle readiness of his fleet and detached several battleships to escort a convoy of supplies for the fleet bound from Malta through the strait of Gibraltar. In fact, procuring fresh meat and vegetables for his scurvy-weakened sailors consumed much of Nelson’s time as he attempted to get these items out to the fleet on station off Cadiz. Nelson’s care with logistics is a hallmark of the operational commander who knows that healthy crews are fighting crews. Nelson also employed what we might today call operational deception.51 Finding the fleet in a close blockade off Cadiz he decided to move it over the horizon so that the French and Spanish would not be aware of its precise location. He maintained watch on Cadiz with his frigates, which could also intercept and turn back snooping Spanish or French ships attempting to gather intelligence. Nelson meant to lure Villeneuve to sea, knowing that if the Frenchman could see his fleet he might not attempt a breakout for the Mediterranean. Once Villeneuve emerged, Nelson’s intention was to intercept and destroy him, but until he judged the wind and time ripe he would remain just out of sight over the horizon paralleling Villeneuve’s course.

Events conspired to cause Villeneuve to finally nerve himself to sortie from port. He knew the British force, through intelligence sources of his own, had been depleted by several battleships and was now inferior to his own. He also knew that if he did not sail, he might not have a fleet to command in any case since he knew a replacement was on the way to relieve him. Napoleon had removed Villeneuve from command but his successor (and rival) Admiral Rosily was still traveling via the overland route through Spain to Cadiz to take command.

Now all was in the hands of the weather, specifically the winds. On October 18, Villeneuve felt confident that the wind was favorable and ordered his fleet to unmoor. On October 19, the first ships began to leave the harbor, although the wind occasionally died, which caused Villeneuve to have several of his battleships towed out of port. Nelson’s frigates signaled the good news that Villeneuve was finally leaving port, bound for Toulon and the Mediterranean in accordance with Napoleon’s orders.52

Historians have argued that Trafalgar had been won before the first shot. This is probably hyperbole but contains much truth, nonetheless some hard fighting had to be done and so we return to Nelson’s masterpiece to see how it all played out in execution.53 Nelson had 27 battleships to 33 for Villeneuve, but this quantitative disadvantage was more than compensated for by the superior morale, leadership, planning, seamanship, and gunnery of Nelson’s fleet. Nelson continued to stalk Villeneuve the next day as the Frenchman proceeded east-southeasterly toward Gibraltar with the combined fleet, however the pace of the French and Spanish advance was so slow that Nelson outran Villeneuve and had to bring his entire battle line around 360 degrees in order to fall back into a correct position vis-à-vis the combined fleet. Villeneuve by now had learned he was being stalked. Despite his numerical superiority at 7:30 a.m. of October 21, he ordered his fleet to “wear” back toward Cadiz and began a gradual turn of the entire fleet back to port.54 He was literally running away from battle. This did not affect Nelson’s plan appreciably; the only difference would be that Nelson’s column would strike near the main body of the combined fleet’s line while Collingwood’s would now strike the rear.

Nelson had prepared for the light and variable winds that made the collision of the two fleets an agonizingly slow process. He had directed his captains to approach with all sail, including studding sails (auxiliary sails that take advantage of every last bit of available wind for motive force). In this way, Nelson would maximize his speed of approach to the enemy, which would minimize the amount of time his ships were under fire before they could respond. Once they pierced the enemy line of battle, the British sailors were to cut these sails away, which would have the double effect of slowing them down (for close engagement) and eliminating these sails from tangling up the standard rigging. Nelson also employed tactical deception by having his own column feint toward the enemy van of ships to confuse them as to his real intention and then turned at the last possible moment toward Villeneuve’s flagship (Bucentaure) in the main body. The result of this action forced the van to maintain its line ahead and to delay its turning back to come to the aid of the rest of the fleet (see figure 3).55

Nelson then added a final edge to his fleet’s fighting mettle when he sent, sequentially, two significant signals, neither of which were tactical but rather inspirational as a means to give his men a combat edge. The first signal elicited a spontaneous outbreak of cheering throughout the fleet: “England expects every man will do his duty.” This signal was passed a quarter of an hour before the first gunfire and nearly five hours after Nelson had ordered the turn toward the enemy. He followed this with a signal for his captains: “Engage the enemy more closely.” This signal might be regarded as Nelson’s final turnover of the battle to the discretion of his captains. After this point, the British fleet was now in the execution phase of the battle, which relied relatively little on Nelson’s personal direction and almost wholly on the actions of his subordinates.56

The last minutes of the approach were harrowing as the lead ships of each column traveled under the heavy and concentrated fire of the combined fleet. Nelson and Victory led the northwestern column and Collingwood was in Royal Sovereign (100) at the head of the southeastern one (the French were heading north toward Cadiz). This provides more evidence of the superiority of the British system since the loss of both ships would mean the loss of the two flag officers—however, they were no longer absolutely necessary for success in the overall battle and became more or less fighting members of the crew of the ship they were on. Collingwood won the race and Royal Sovereign crashed into the rear third of the French-Spanish fleet just past noon. He had minimized his casualties by having his sailors lie down during the final minutes of the approach so he would have every man possible to work the guns and deliver the first devastating broadsides, simultaneously, into the ships on his left and right as he pierced Villeneuve’s line, as his captains had done at the Nile. The French and Spanish could only reply with the relatively few guns mounted on the bow and stern of their vessels.57

The battle now became a melee as Nelson’s Victory plowed between Villeneuve’s flagship Bucentaure (80) and the battleship behind her, Redoubtable (74). The French gunners had had much better success against Victory, which lost many of her sails and had had her helm shot away, yet her momentum carried her ahead as planned. Victory’s point-blank broadsides, especially from her 68-pound carronades, caused horrendous casualties in the two French ships. Not long after, a sharpshooter aboard Redoubtable (74) sighted the bemedaled Nelson, who had refused to take cover below decks, took a bead, and fired. The ball hit Nelson in the left shoulder and then ricocheted through his lung, finally lodging in his spine. This mortal combination of wounds led to Nelson’s slow and painful death. Redoubtable now prepared to board the ailing Victory but her boarding party was wiped out by a devastating broadside from the Téméraire (98), following in line behind Victory.58

Much of the remainder of the battle followed this same pattern of devastating close combat, but in all cases the British had the better of it up and down the line. Meanwhile, Villeneuve was frantically signaling his van under the French Admiral Dumanoir to come about to assist in the battle. Dumanoir did not see the initial signals due to the smoke of battle and continued sailing toward Cadiz. It was only at 3:00 p.m. that he came about. By this time, about 15 ships of the combined fleet had struck their colors (surrendered), including Villeneuve aboard Bucentaure. Virtually all of them were blazing charnel houses full of dead and dying men. What remained of the French van, unable to affect the outcome of the battle, fled to Cadiz. Not a single British vessel had been lost. Nelson died around 4:30 p.m., but he died with the knowledge that his men had won the most complete victory at sea ever obtained by a modern sailing fleet.59

In total, the British captured 10 French and 10 Spanish ships, however, a subsequent terrific storm damaged or sank many of these and the British were only able to salvage 4 battleships to add to the Royal Navy’s order of battle. British casualties at Trafalgar numbered 449 killed and 1,241 wounded. French and Spanish casualties, including prisoners, were almost 10 times that of the British, including over 4,000 killed alone. Several days later, British admiral Sir Richard Strachan intercepted, attacked, and captured four of the surviving French ships that had escaped the battle intact.60 Thus the Royal Navy gained eight new battleships as a result of Nelson’s and Strachan’s battles.

THE LEGACY OF NELSON FOR NAVAL WARFARE

Prior to Nelson’s famous victory, other British admirals had indeed mirrored and even suggested his approach of centralized planning and decentralized execution. One recalls especially Admiral Rodney whose melee tactics against the comte de Grasse during the American Revolution foreshadowed those of Nelson.61 However, the Royal Navy’s institutional attitude toward Nelson’s methods, best highlighted at the Nile, was only occasionally and arbitrarily applied by the other admirals of the fleet prior to that battle. After the Nile, these methods became the norm, not the least because it was Nelson’s way as much as for their excellence from an operational standpoint. The results of subsequent history contradict those who argue for the uniqueness of the results of the “Nelson Touch” and its confinement only to the period of his executive leadership.

* * *

Despite Napoleon’s best efforts to rebuild and reanimate his navy, the French never again came close to challenging Britain at sea. Nelson’s heirs had no real difficulties maintaining their ascendance and even repeated Nelson’s destruction of Danish sea power at Copenhagen in 1807, this time in concert with the army. By 1813, Napoleon’s need for men and material, particularly trained artillerists and infantrymen, was so great that ships were denuded of their crews. These men were then formed into new batteries and regiments du marine that were promptly marched off to Central Germany to perish on land. The other great result of Trafalgar involved Napoleon’s imposition of the Continental System as a cumulative economic strategy against the cumulative sea power strategy of Britain. From this “paper blockade,” never realistically enforceable, flowed much that would result in Napoleon’s downfall, including his disastrous interventions in the Iberian Peninsula (see chapter 6) and Russia in 1812 (see chapter 7).62

Trafalgar was decisive, but mostly for the period after 1805 and not so much for the events that occurred on land and sea in 1805. The British naval campaign of 1805 and Nelson’s subsequent engagement at Trafalgar embodied the successful application of superior sea power by a major European power and highlight the necessary role that command of the sea by Great Britain would play in shaping the eventual defeat of Napoleon. Finally, Nelson’s style of command demonstrated the superiority of the principles of centralized planning, decentralized execution, and operational mission command for the successful prosecution of modern naval warfare.