9

Competing, Managing, and

Investing in the Intangible Economy

What will successful companies look like in an intangible-rich economy, and how can managers and investors create and invest in them? In this chapter we’ll look at what people thought the new economy might mean for companies and managers, and how it hasn’t quite worked out that way, due, we think, to the characteristics of intangibles. We’ll then look at whether the rules for sustaining competitive advantage have changed (they haven’t), if management is becoming more important (it is), and how suited current accounting measures are for investors to identify such advantage (they aren’t).

Back in the heady days of the late 1990s, when pundits began to be excited en masse about a new economy, there was something of a shared vision of what businesses would need to do to succeed in the new economy, and what that would mean for management and working life.

Charles Handy’s 1994 book The Future of Work forecasted, presciently, a future of portfolio jobs and careers for the well-educated and precarious subcontracting for others. Charles Leadbeater’s Living on Thin Air, published at the height of the dot-com bubble, begins with a portrait of the author as a portfolio knowledge worker and then identifies eight characteristics that successful new economy companies would have: they would be cellular, self-managing, entrepreneurial, and integrative; they would offer their staff ownership stakes; and they would need deep reservoirs of knowledge, public legitimacy, and collaborative leadership. The view of how businesses succeed blends Japanese management theory such as Nonaka and Takeuchi’s concept of the “knowledge-creating” company (in a book of the same title, 1991) with studies of entrepreneurial innovation observed from the Silicon Valley firms of the day.

Like many of the things in Handy’s and Leadbeater’s books—both of which have aged rather well—all of these predictions have to some extent come to pass. Drop into a coffee shop in any of the world’s major cities, and you will see peripatetic knowledge workers of the type that Handy described in the early 1990s. Look at the way people talk about the world’s most admired businesses (“What Would Google Do?”), and you will see praise for the kind of knowledge-intensive, collaborative, networked business innovation that would not have seemed out of place in 1990s California or Japan.

But some things have turned out somewhat differently, either because they buck the trend of knowledge-intensive, modular businesses and the nomadic, entrepreneurial knowledge workers, or simply because they were less obvious back in 1999.

A graphic illustration of this is the Amazon warehouse. Sarah O’Connor, writing in the Financial Times in 2013, painted a vivid portrait of working and managing in the Amazon warehouse in Rugeley, in the UK’s West Midlands.1 The word “autonomous knowledge work” is unlikely to figure on the employees’ job description. Warehouse staffers have GPS trackers that optimize their route to package an order: relatively straightforward if the order is just a book, but a formidable technical achievement if the order is a book, a vacuum cleaner, Junior Monopoly, and a pair of skis. Of course, the tracker also enables managers to keep an eye on where the workers are and how fast they are moving. O’Connor describes managers sending text messages to employees to speed up and advising them to put Vaseline on their feet to prevent blisters from all the walking (up to 15 miles per shift is quoted). So in the actually existing new economy, not everyone turned out to be a “self-facilitating media node” (as late 1990s knowledge workers were sarcastically described by satirist Charlie Brooker). The intangible economy is as much about Amazon warehouses and the Starbucks operating manual as it is about hipsters in Shoreditch and Williamsburg, or empowered Kanban production workers in Japanese-inspired factories.

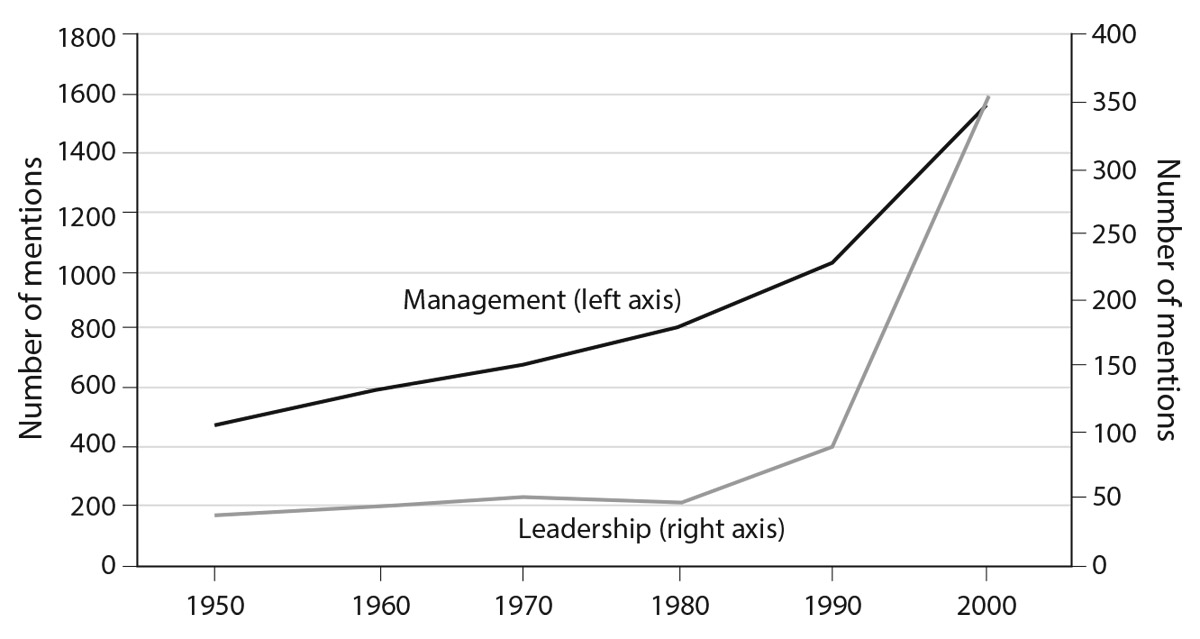

Perhaps a second way that the new economy has turned out unexpectedly is the emergence of the cult of the manager. Endless management hagiographies adorn airport bookshelves. Managers get invited to Davos. Jack Welch, the former CEO of General Electric, has an institute named after him. And, of course, CEOs are famously highly rewarded. Now this has been supplanted by the new cult of “leadership.” Figure 9.1 sets out by decade the number of times “leadership,” as against “management,” is mentioned as a subject in an article in the Harvard Business Review. References to management have grown steadily. But references to leadership have exploded since the 2000s.

This idolatry is in many ways a huge puzzle. Don’t we live in a much less deferential age? Aren’t we less willing to take instructions and less trustful of authority figures? Surely changes in social norms would appear to bias people away from these reverential attitudes to managers and leaders?

A third way that the new economy has turned out, perhaps not quite as expected, is what might be called a “rush for scale.” Alongside the small portfolio contractors and lean, networked businesses we see some behemoths: new multi-billion-dollar companies with big scale and bigger ambitions. As we have seen in chapter 5, the leading firms seem to have become even more leading: more profitable, more productive. Peter Thiel, the cofounder of PayPal, has written engagingly on these issues in his book Zero to One, stressing that commercial success is built on exploiting network effects and economies of scale: as he points out, Twitter can easily scale up but a yoga studio cannot.

We shall argue that these seemingly contradictory changes all arise from the essential economic characteristics of intangible assets. To tell this story, we start by arguing that the evolution of work and the cult of management come not only from changes in social norms and the like, but also from the evolution of companies. In turn, these companies are trying to compete in their market. Thus we start by setting out the pressures companies are under to compete and how the growth of intangibles changes what companies have to do. As we shall see, in an intangible-rich economy, the pressure to compete pushes companies toward large scale and an emphasis on management. This not only changes how companies compete and manage but also where investors should look for returns, so we conclude with some advice for them.

Competing

One of the most important practical questions put to experts in business strategy, management, accounting, and economics is “How can my firm get ahead?” Not surprisingly, such a question has elicited many answers.

The starting point is to refine the question, since it all depends on what you mean by “getting ahead.” One way to get ahead is short-term manipulation of accounting aggregates. As we observed in chapter 8, cutting R&D, for example, cuts current spending, and, if the firm already has a good stream of revenues from previous R&D, this may have no negative effect on revenues for years. Revenues the same, costs down, hey, presto: profits up. As we shall see later in this chapter, and as Baruch Lev and Feng Gu have pointed out (2016), accounting conventions make it very hard for outside investors to see if firms are doing this. But, for the moment, let us take from this observation that a more sophisticated version of “How can firms get ahead?” is to ask “How can firms improve performance that is sustainable?”—that is, not via short-term manipulation.2

The easiest way to see how firms might create sustained competitive advantage is to start by thinking about a world where they cannot. According to the US Department of Agriculture, in 2016 there were around 25,000 farms in Idaho, cultivating almost 12 million acres, with an average farm size of 474 acres (of which 60 percent were below 100 acres).3 That means that each single farm area is about 0.004 percent of total cultivated area. Despite the geographical advantages of Idaho, especially in potato production (southern Idaho has warm days and cool nights during the potato growing season), it’s pretty unlikely that any individual farm is going to have much advantage over another. Their outputs are going to be the same, and their inputs, the machines, soil, and expertise, are likely the same too.

All this suggests that sustainable competitive advantage comes if a company can do something distinctive, or if it owns a distinctive asset. An Idaho farmer cannot do better than their neighbor, but can do better than a farmer in Canada, since they own the distinctive asset of land in Idaho. Of course, a distinctive asset might not necessarily be an input, but it might be reputation or a network of customers (Swiss watches, say, or Facebook). The management literature calls these distinctive assets “strategic resources” and says they have three characteristics. They are (a) valuable (e.g., a patent), (b) rare (e.g., a landing slot at a busy airport), and (c) hard to imitate (e.g., Swiss watch reputation).4

So the advice to managers has always been: build and maintain distinctive assets. And to investors: look for firms that have these types of assets. Does that advice change in an intangible world? No. But the intangible-rich world is precisely a reflection of firms that are increasingly taking this advice. Why?

It’s pretty unusual that a tangible asset is going to be a source of distinctiveness. Perhaps a specially customized machine might be. But for the most part tangible assets are not going to be distinctive. A bank might build a grand head office with a soaring atrium, colorful fish-tanks, and minimalist desks in the lobby. But any other company can do that too. It’s much more likely that the types of intangible assets we have talked about in this book are going to be distinctive: reputation, product design, trained employees providing customer service. Indeed, perhaps the most distinctive asset will be the ability to weave all these assets together; so a particularly valuable intangible asset will be the organization itself.

These insights are implicit in Peter Thiel’s book Zero to One. His view is that commercial success is built on four characteristics: building a proprietary technology; exploiting network effects; benefiting from economies of scale; and branding. These recommendations are firmly in line with the strategy for an intangible-rich business, based on the four S’s that we discussed in chapter 4. So, for example, he rightly points out that Twitter can easily scale up: a prime example of economies of scale in action. By contrast, he uses a yoga studio as an example of a business that cannot scale up and so is destined to stay small. As we have seen, Les Mills International had to adopt a very different business model from traditional gym businesses in order to grow to the size it did.

The emphasis on network effects is an insight of Thiel’s that suggests that governments might become more important to company success in the future. One of Peter Thiel’s PayPal cofounders, Elon Musk, is currently involved in what might become one of the ultimate network businesses: self-driving, battery-powered cars. The network effect would be familiar to any nineteenth-century entrepreneur. Horses and carts needed a gigantic network of stables to feed and water the horses and repair the carts. Then gas-driven cars needed a gigantic network of garages and gas stations. Now, electric cars will need a network of charging stations. To implement all this requires state help, and Musk has been as much an entrepreneur in getting the support of governments as he has been in driving the technology in the business. The legal travails of Uber and AirB&B are similar examples.

But one characteristic of successful businesses that Thiel seems to omit is building a good organization. Wal-Mart and K-Mart are in the same industry, have more or less the same types of trucks and fixtures in their stores, and stock very similar goods. Yet even to the everyday observer, they are vastly different. What makes them different is in part their reputation, but also the very organization itself. So let us turn to the organization and, in particular, the role of management and leadership.

Managing

One reason for the celebrity status of managers is offered by the consistently fascinating blogger Chris Dillow,5 namely, the cognitive bias of “fundamental attribution error.” As we discussed in chapter 6, if people tend to relate the success of a company to its hero manager, rather than to general progress of technology or the state of the economy or the organizational capital embodied in the company itself, they may reward the manager too highly. Thus the manager or leader becomes the subject of a cargo cult. Boards, cowed by the social norms of the age, grant managers excessive salaries, which inattentive shareholders are apparently willing to put through on the nod. Outside observers fulminate as top managerial salaries, even in the public sector, become multiples of what a prime minister or president gets paid.

As the brilliant economist-educator Russell Roberts (2014) points out, chroniclers of the cult of celebrity have an extensive pedigree. Writing in The Theory of Moral Sentiments in 1759, Adam Smith points out, “We frequently see the respectful attentions of the world more strongly directed towards the rich and the great, than towards the wise and the virtuous.” This perfectly anticipates the modern day cult around Z list celebrities. He argues that a fascination with others who are loved is part of our natural desire to be loved ourselves. So a natural obsession with celebrities is funneled toward managers, regardless of their virtue.

Management and Monitoring

We’ve seen that the intangible economy will build more assets that are sunk, have synergies, can be scaled, and potentially confer spillovers. Can these characteristics explain the rise of reverence for management? To answer this question we need to step back and ask a much more basic question: What are managers for?

Maybe everyday life provides the answer: they manage. They provide leadership and strategic direction to companies. They inspire and motivate. They plan and execute. A moment’s reflection, however, makes one not so sure. They spend time in pointless meetings. They award themselves pay increases and don’t take the blame when things go wrong.

These observations are unhelpful because they are not answers to the question: they describe what managers do, but not what they are for. To begin to get an answer, let’s think about your relationship with your window cleaner. When the window cleaner comes around to your house, it’s a fair bet that you do the same thing as everyone else. You ask the price. The cleaner does the windows. You have a quick look at the windows and, if they are clean, you hand over the money.

Where is the management, leadership, and strategic direction in this transaction? Where are the management consultants? What about the financial, legal, and health and safety advisors? The answer, to economists, is that they aren’t needed because the market has taken care of the entire process: you have agreed on a price, the seller has delivered, the buyer pays.

But engaging a window cleaner seems different from running a firm. It’s true that workers in the firm have agreed on a price for their labor, but there is no (or there shouldn’t be) hour-by-hour haggling about prices and responsibilities. Instead managers within a firm have something else: they have authority. That is, they have the right to instruct their colleagues what to do in the execution of their tasks and to remove them if they don’t perform. Of course, you can refuse to pay your window cleaner if the task isn’t performed satisfactorily and get them out of your house, but that just says you can choose to stop any commercial relationship. But firms are different. In firms, managers have the authority to choose whether their workers work with the firm’s assets, using the firm’s machines or transacting on behalf of the firm, and so working with the firm’s reputation. You can’t stop your independent window cleaner from using their bucket since you don’t have the authority, but if you managed a firm of window cleaners you would be able to.

So to an economist, the question “What are managers for?” hides a deeper question: “What’s the role of authority in an economy?” Actually, this is a much harder question than it appears. To see why, start with an economy where we know the answer: North Korea. In a centrally planned economy authority decides everything: who gets food, when they get electricity, what jobs people do, is all decided by the planners. So authority simply decides.

So who decides in a noncentrally planned economy? Friedrich von Hayek was awarded the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1974 for coming up with a brilliant answer: nobody. To buy a pencil in a market economy, one simply goes into a shop to get it. Purchasers of pencils don’t know those who made the pencil—who mined the graphite, cut down the trees, or transported the pencil to the shop—so can hardly issue them with instructions. Those engaged in its production, the miners, the tree-fellers, and the truckers, take instructions not from the individual pencil buyers but via the price system. If pencil prices rise, more graphite is mined, more trees are felled, and more wood is transported. No personal authority is required, since the price system issues the instructions.

In light of this, in 1937 Ronald Coase (another Nobel laureate) asked a deceptively simple, but very profound, question: Why then do firms exist? If markets do a pretty good job coordinating the economy, what’s the need for firms? Coase’s answer was that firms did a cheaper job of coordination than markets. Inside a firm, Coase said, coordination by internal markets would be very costly since you would have to (a) discover what the market prices are and (b) negotiate a contract for each and every transaction.

This is where managers come in. If the market cannot coordinate activity but authority can, then someone has to exercise the authority. That person is the manager, where managers are defined as people in a firm who have authority. That’s quite a neat definition and is, indeed, used by statistical authorities when they run occupational questionnaires and ask people to self-report if they are managers.6

So, costs are avoided inside the firm via authority. Rather than haggling all the time, an employer tells an employee what to do and the employee does it. Hence, the role for managers. They perform the coordination activity within a firm that a market cannot, and they do so via authority.

Coase’s reasoning has considerable power. In 2014 the California courts delivered their verdict on whether FedEx drivers are contractors for FedEx or employees.7 Had Coase been alive (he died the year before, aged 102) he would have been the perfect expert witness. They decided that FedEx was an employer precisely because they told the drivers what to do: exactly Coase’s reasoning.

The exercise of authority seems like a good description of the Amazon warehouse above. A lot of careful process engineering has combined to allow a system where the optimal route around the warehouse can be computed very efficiently. As the economist Luis Garicano has pointed out (2000), enhancements in information technology have improved the flow of information around the organization. A fall in the price of information might lead to less authority: the breakdown of hierarchies, with autonomous workers e-mailing ideas up to the boss. However, monitoring has also become more efficient with the growth of IT, so, in the Amazon case, IT has reinforced a “command and control” type of organizational design.

Thus, part of the reason for the perhaps unexpected growth in this type of very nonautonomous work is that the intangibles of organizational development and software enable more and more effective monitoring. Thus they are substitutes for autonomy. Under the right circumstances (or should that be the wrong circumstances?), it automates autonomous labor in the same way a machine automates physical labor. Marxist economists have a name for this additional monitoring role: “power-biased technological change” (see, e.g., the discussion in Guy 2014). Other examples are the cash register and the tachometer in a truck (the “Spy in the Cab”). All in all, how work changes and, therefore, how the nature of management changes depends on where you sit in the intangible value chain.

Management in an Intangible-Rich World?

If management is just monitoring, then, of course, changes in monitoring technology, such as IT, change management. Indeed, there might be less need for management if authority can be exerted by anyone with tracking software. There doesn’t seem to be any special role for intangible assets and no reason why the cult of management and managerial rewards would get bigger. So, is there more or less need for management and authority in an intangible-rich firm than in a tangible-rich firm?

In a second wave of work following Coase, economists like Oliver Williamson thought harder about the haggling problems that Coase had said could be solved by monitoring and authority within firms. In particular, Williamson observed that haggling would be particularly costly where parties sink costs. Once a railway firm, let us say, has laid some track, the firm has committed capital to the business in general and the route in particular. This potentially puts such workers in a powerful bargaining position. The anticipation of such a disadvantageous position might then deter the firm from making an initial investment: known in economics as the hold-up problem.

Now, if intangible investments are particularly significant for a firm, and if those investments are sunk, then the opportunities for hold-up are potentially substantial. That puts the costs of haggling potentially very high. If managers of those firms can exert authority and avoid this potentially costly, wasteful haggling, those managers will be potentially very valuable. So, maybe one reason for the emergence of highly rewarded managers is that in the intangible economy, the stakes are much higher, so there’s a much higher demand for them.

The other features of intangibles would also raise the demand for internal coordination by managers. Much the same reasoning goes for synergy. If intangibles have lots of potential synergies, then to capture them effectively requires transacting within a firm and encouraging interactions with others who are similarly sinking costs. And if those combinations of intangibles can yield scale, then firms will get very large too, and their managers will be in high demand.

So even if all firms might need authority and coordination, the move to an intangible-rich firm will raise the demand for such coordination and so raise the demand for managers. But what will those managers do exactly?

One way to answer this question is to pose another: If the intangible economy will put a premium on good coordination by star managers, why isn’t the whole economy taken over by these great managers? Intangibles do indeed predict giant firms, as measured by revenues, since intangibles can be scaled (think of Facebook’s revenues). But what about giant firms, as measured by the number of employees? After all, if exploiting intangibles needs synergies then surely one needs giant firms with many employees to internalize all those benefits.

One answer is that intangibles, like routing software, make monitoring easier and so firms can get bigger. The countervailing force is that managing large firms is hard, and managing large intangible-intensive firms is even harder. Of course, the natural limitations of attention span and bandwidth make authority over giant firms very hard to manage, be they tangible or intangible. But in intangible-intensive businesses there are two particularly hard challenges.

The first arises from the synergies that are endemic in intangibles. Information-sharing is going to be very valuable, for when intangibles are combined with each other, the whole can be more than the sum of the parts. Is authority the way to organize these combinations? It depends on the structure of information in the firm: In other words, do managers or workers know better what’s going on?

The usual response for many firms is that the workers know what’s going on, since managers are remote and out of day-to-day touch. But with synergistic firms, precisely the opposite might hold. Maybe only the managers know what’s going on, since only the managers can see the big picture and realize how the synergies might link up. All this suggests that both sides need each other, and it’s not clear if authority is going to be the right way to organize information-building.

The second problem with managing an intangible business is that, as employment gets increasingly knowledge-intensive, the importance of key knowledge workers to the firm rises if their knowledge is tacit. And keeping those assets is harder than keeping physical assets. Tangible assets can be secured by lock and key: intangible assets not so.

All this means that in intangible-intensive firms there will be a premium on managers who can share information both up and down the organization and keep loyal workers sticking to the firm. That means using authority in a way that builds a good organization.

Building a Good Organization

Anyone who has spent time in more or less any workplace will probably recognize Milgrom and Roberts’s observations on the near-universal reputation of personnel departments as representing everything that’s bad about an organization:

In every organization with which we have been associated, and in most of those of which we have heard, the Personnel Department is viewed by line managers and employees as unresponsive, rule-bound, and bureaucratic. It takes forever to get a decision from Personnel, and the decisions seem aimed more at maintaining the Personnel Department’s precious rules, procedures, and job classification/earnings and experience/earnings curves than at attracting, rewarding, and retaining the best people for the organization. Moreover, protests fall on deaf ears: Personnel people are always in meetings when you try to reach them, and they do not return your calls. (Milgrom and Roberts 1988, S176)

If personnel departments are the problem, not the solution, what about star managers? Boris Groysberg, Andrew McLean, and Nitian Nohria studied twenty managers who left GE between 1989 and 2001 to become CEOs of other companies (Groysberg, McLean, and Nohria 2006). As it turns out, there are a lot of CEOs of major US companies who were from GE over their sample period: James McNerney at 3M and Robert Nardelli at Home Depot, for example. They studied profits (relative to a sensible comparator) in companies following three years of the new CEO’s tenure. The result was disappointing for the reputation of managers as uniform superstars—they found that the managers were by no means uniformly successful. In nine out of the twenty cases firms did much better than their competitors (on their measure, annualized abnormal returns, by 14.1 percent) but in the other eleven, firms did substantially worse (by −39.8 percent).

So, what makes a good organization? The Amazon warehouse suggests one answer: more coordination. Issue more instructions, write tighter employment contracts, and enforce noncompete clauses when workers leave the firm. Despite its overtones, one might see how this might be a good way forward for some firms, or divisions within firms. Amazon, for example, might take the view that their reputation for fast delivery needs close supervision of their dispatch workers. Starbucks might argue that their reputation for coffee means telling baristas exactly what to do.

And some systematic evidence supports this view. The economists Nicholas Bloom and John Van Reenen and their coauthors have extensively surveyed firms to ask about the quality of their management. Such quality is very hard to measure, and they use a series of questions, building on work by McKinsey, about management practices (see www.worldmanagementsurvey.org). This divides into monitoring (monitoring the firm and improving); targets (setting targets and acting upon them); and incentives (rewarding employees based on performance). As they nicely summarize: “Our methodology defines a badly managed organization as one that fails to track performance, has no effective targets, and bases promotions on tenure with no system to address persistent employee underperformance. In contrast, a well-managed organization is defined as continuously monitoring and trying to improve its processes, setting comprehensive and stretching targets, and promoting high-performing employees and fixing (by training or exit) underperforming employees.” (Bloom et al. 2011, 7)

But this might not be good management in all circumstances. Consider a firm that sets stretching targets, as in the Amazon warehouse, for example. For workers in it for the short term, maybe to earn extra cash for Christmas, they will work really hard and then stop. (Indeed O’Connor mentions that many workers are let go after the Christmas rush.) Good for them and good for Amazon. But what about workers in it for the long term? If they move fast around the warehouse before Christmas, their managers will crank up the target and require them to move even faster after Christmas. This is known as the “ratchet effect,” discussed by Weitzman (1980), who credits it to Berliner (1957), writing about Soviet planning. Thus dispatchers work less hard initially, defeating the object of the incentive scheme. Maybe not such good management after all.8

Another problem with having managers do lots of target setting, performance reviews, and the like is politicking. Suppose workers realize that they can do better for themselves by spending time not producing or innovating or helping, but by trying to persuade their manager. Maybe the manager might be persuaded that the task is very hard, and so setting relaxed targets is good. Or that a bonus is really needed. Or that performance really was very good. This time spent on what the economists Paul Milgrom and John Roberts politely call “influence activities” is time spent away from productive activity (Milgrom and Roberts 1988). Again, maybe not such good management after all.

In both of these examples, a good organization is about commitment. In the ratchet effect example, the organization benefits if it commits not to punish good performance now with over-stretching targets in the future. One way to do this is not gear high reward on day-to-day performance, but instead promise a steady trajectory of reward over the longer term. Likewise, reducing politicking means committing to not making minute-by-minute adjustments of terms and conditions, but, again, to look at performance over a longer run. And in Milgrom and Robert’s view, this design of the (caricatured) personnel department is one form of that commitment. If personnel bends rules instantly in response to any demand from any employee, everyone will spend their time lobbying. Having rules and being unresponsive commits to not being swayed by influence activities and so dissuades employees from them.

So how can managers build a good organization in an intangible-intensive firm? One answer to that question is to choose the right organizational design, and that choice depends on whether your organization predominantly uses or produces intangibles.

So, if you are predominantly a producer of intangible assets (writing software, doing design, producing research) you probably want to build an organization that allows information to flow, helps serendipitous interactions, and keeps the key talent. That probably means allowing more autonomy, fewer targets, and more access to the boss, even if that is at the cost of influence activities. This seems to describe the types of autonomous organizations that the earlier writers, like Charles Leadbeater, had in mind. And it also seems to describe the increasing importance of systemic innovators. Such innovators are not inventors of single, isolated inventions. Rather, their role is to coordinate the synergies that successfully bring such an innovation to market.

Similarly, the skills to manage the innovation process will be different than before. As we have seen, the rise of the intangible economy makes the innovation process itself more important. The management scholars Mark Dodgson, David Gann, and Ammon Salter (2005) describe how it has changed from what was the traditional taxonomy of “research” and “development” to a functional description of the process of “Innovation Technology,” as needing “thinking,” “playing,” and “doing,” stressing the new scope for easier exchange of ideas, experimentation, and faster implementation of ideas.

What if, by contrast, you are more a user of intangible assets: say, the Amazon warehouse, using the knowledge of the routing algorithm, or Starbucks, using the franchise book? For these firms, the organization and so management would look different. You probably want to have more hierarchies and short-term targets, since you are less worried about information flows from below and more concerned about low performance and stopping influence activities.

Leadership

If many of the visions of earlier writers on the knowledge economy have come to pass (such as organizations with peripatetic, autonomous workers), one thing they did not foresee is the seemingly growing importance of leadership. And as we have seen, management by authority may have some weaknesses such as not encouraging information flow or commitment. We shall argue that leadership is important in an intangible-intensive firm since it complements authority relations and organizational forms.

Why is leadership different from management? One approach is to try describing what a “good” and “bad” leader does: are they kind or heartless, tough or gentle, family-friendly or not, and so on. Since social norms and management fads change faster than most CEOs turn over, this approach is just endless speculation.

So it’s better to get to the heart of the matter, which is the simple observation that leaders have followers. In the military, the most obvious example of leaders and followers, followers follow as a matter of compulsion, so that is easy to explain. What’s much more interesting is when followers voluntarily stay loyal to their leaders.

Having voluntary followers is really useful in an intangible economy. A follower will stay loyal to the firm, which keeps the tacit intangible capital at the firm. Better, if they are inspired by and empathize with the leader, they will cooperate with each other and feed information up to the leader. This is why leadership is going to be so valued in an intangible economy. It can at best replace, and likely mitigate, the costly and possibly distortive aspects of managing by authority.

A good example of the importance of leadership in an intangible age can be seen in the phenomenon sometimes called systems or systemic innovation. Elon Musk is sometimes described as a systems innovator, aspiring to develop new products in a number of related fields (electricity storage, solar power, electric cars) or in complex systems (space procurement, carbon credits). Systems innovation is also widely discussed in the not-for-profit sector, particularly as large-scale funders such as the Gates Foundation and Bloomberg Philanthropies seek to change whole systems at once, such as public health in developing countries or city government. Since even rich organizations are not usually big enough to directly control major economic systems, systems innovation relies on leadership: the ability to convince other organizations, networks of partners, and even competitors to do what the systems innovator wants. We would expect to see this kind of systemic leadership becoming more important in an age in which most investment is intangible. One reason is that in an intangible economy, there are plentiful synergies to be exploited between different investments—a leader who can convince the battery industry to develop products and design systems in sync with the electric car industry will prosper. Similarly, if the difficulty of appropriating the spillovers of intangible investments ends up being resolved by greater public investment (as we suggest in chapter 10), then the ability to interact effectively with the complex systems of the public sector will be a commercial advantage too. The systems innovators who can do these things demonstrate an example of the importance of leadership in an intangible economy.

Thus the question is: How do leaders get followers to follow them? The precise answer depends on how you think followers think. As we mentioned in the introduction, if celebrity worship is common in your employees, your employees might follow you regardless. Another view is that followers are much more hard-nosed and will only follow if they think it’s in their interests to follow. The economist Benjamin Hermalin (1998) has shown that this might lead to a number of interesting features.

First, the leader will have to know more than the followers. Perhaps this explains the importance of the growth of mission statements. In some cases this is, perhaps, sheer puff. But it could be of great value if it convinces potential followers that the leaders know more than they do.

Second, leaders don’t just have to know more, but to convince followers that they know more. Leaders can do so in a number of ways. Of course, they will have to be good communicators. But more interestingly, followers will be more convinced if they see commitment by leaders. Hermalin suggests that leaders can show commitment in two ways. First, by example. If a leader stays really late at the office, or invests their own money, followers will have been shown commitment. Second, by sacrifice. Want to find out if the leader thinks that a project is going to succeed? See if they buy pizza for those who work late on it. If they do, that’s a signal the work is worth it.

Summary: Managers and Leaders in an Intangible Economy

What are the lessons for managers in all this? First, the intangible economy itself will place a premium on good organization and management. With more sunk costs, spillovers, and the opportunity for scale and synergies, the need for additional coordination rises, and so good organization and management will be in higher demand.

Second, what kind of organizations will this economy demand? The economic insights of wanting coordination and knowledge flows without encouraging influence activities suggest that different types of organizations will emerge, matched to the parts of the intangible economy they specialize in. Are you creating intangible assets (writing software, doing design, producing research)? If so, you probably want a flat organization with more autonomy, fewer targets, and more access to the boss. That will cost you time on influence activities, but will build an organization that allows information to flow, helps serendipitous interactions, and keeps the key talent. Are you using intangible assets (say, the routines in the Starbucks franchise book)? Then you probably want more control and authority to use the asset to its fullest advantage and stop influence activities.

Finally, the intangible economy will demand leaders in addition to managers. Management, in the simple sense of authority, will likely not be enough in most intangible-rich firms. To exploit synergies from knowledge-intensive workers and to scale up operations in these firms is too hard to manage by simply exerting authority. Leadership, in the sense of motivating loyalty and effort, will be needed.

If sufficient numbers of employees are convinced by puffery and conceit, then some leaders will gladly supply it. But we suspect that more enduringly successful leaders will have to earn respect by making sacrifices. They will have to work hard and show commitment to the company. And those leaders will, in turn, match the right organizational form to their needs.

All this suggests that the increased interest in management and leadership that we documented at the start of this chapter is real. It’s a consequence of fundamental shifts in the economy and not only attitudinal changes and social acceptance. But if the increasing demand attracts both the sincere and the charlatan, both the able and the huckster, then attitudes might change. Just as unworthy leaders are being rejected in politics, maybe the social acceptance of leaders in business might be attenuated if the perception is that such positions are dominated by the unworthy. That will make leadership of the good managers harder to earn but easier to sustain.

Investing

What about investors? As discussed above, returns are to scarcity. And scarcity, for firms, comes from building advantages that are distinctive and cannot be easily replicated. Little of that will come from tangible assets: anyone can rent a machine or delivery truck. But much might come from intangible assets. So the first question to ask is: How can an outside investor detect if a firm is building its intangible assets?

Accounting for Investment: Some General Principles

In a series of books and papers, the accounting scholar Baruch Lev and his coauthor have asked the very important question: Can investors get information about intangibles from accounting data? The answer to this question is hinted at strongly in the title of their most recent book, The End of Accounting (Lev and Gu 2016).

In compiling the profit and loss accounts (also known as an income statement), accountants are concerned with reporting the flows of revenues and their associated costs over the course of a financial period. And indeed, financial analysts spend an awful lot of time looking at profits or earnings—broadly, the difference between revenues and the various measures of costs.

Quite reasonably then, accountants try to match the revenues, in the last year, to the costs that have been incurred in generating them. For example, the cost of leather to produce shoes—that is, the cost of raw materials used up in production—are quite sensibly allocated as costs (“cost of sales”).

What about matching revenues with costs incurred when spending on assets? This is trickier, since, by definition, benefits will arise over more than the particular year in which the costs are incurred and so do not match with revenues of that year. How then does one achieve the matching of this spending with revenues? The answer is to capitalize these costs: that is, to recognize that tangible spending creates an asset. Once that is done, the expense of that asset can be reflected in its depreciation or amortization: that is, a year-by-year amount is treated as an expense, and that year-by-year amount reflects a charge for the using up over time of the long-lived asset.

The alternate to capitalization of spending on assets is to “expense” them, that is, charge the entire cost of the asset in one year to costs, rather than the implicit smoothing of costs in capitalization. As is well known, and as Baruch Lev has forcefully pointed out in a long series of books and papers (see, e.g., Lev 2001), expensing the cost of long-lived assets leads to distortions in profits, resulting from the “mismatch” of revenues and costs. In the year of incurring these costs a firm looks very unprofitable, as its costs are very large but revenues unchanged. But if the asset is useful and helps generate revenues (a truck, R&D leading to a successful patent, an increased consumer network, etc.), then in the future the firm appears to be highly profitable on the basis of very little costs incurred and very few assets acquired.

Accounting Treatment of Intangibles:

Expensing versus Capitalization

All this matters crucially if investors are very interested in detecting spending on intangibles. So how are they treated?

Accounting rules are broadly the same internationally in this case. If the intangible is purchased outside the company—for example, buying a patent outright or a customer list—it is an asset, not an expense, and so is capitalized. By contrast, if it is internally generated—an internal design or software, for example—it is treated not as buying an asset, but as an expense. There are exceptions to these general rules, but they tend to be rare. Internally generated software or R&D spending can be treated as asset investment but under special circumstances: essentially when such spending is on a proven process, such as the last development stages of an already-proven R&D project or software tool.9

It is remarkable that these rules are so asymmetric. One might reasonably object that the value of an intangible asset is so uncertain that it should not be capitalized, but that would mean not capitalizing it whether it is internally generated or bought.10 British American Tobacco reported in 2015 that it had almost £10bn worth of intangible assets (it had only £3bn of tangible assets, that is, property, plant, equipment). Most of the increase that year had come via the value of goodwill from purchases of other companies—for example, the brand name from buying Rothmans. A very small amount had come from internally written software. But if they had invested in building trademarks in-house, the additions to intangible assets would have been zero.11

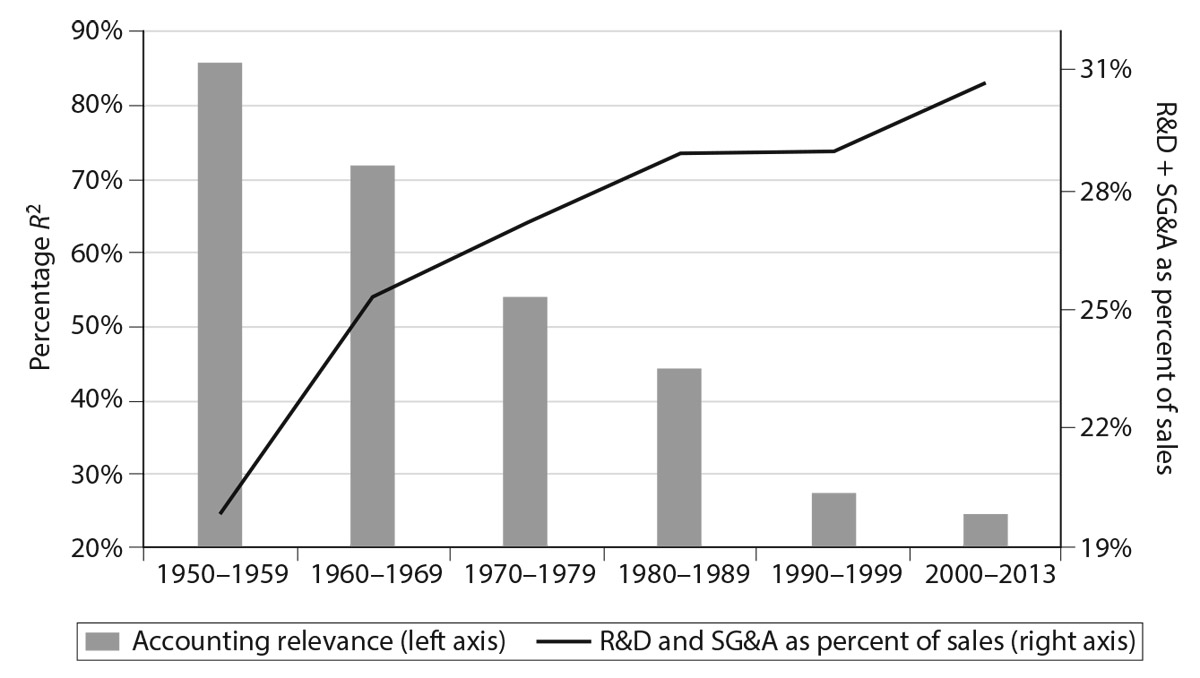

As a consequence, much (at least internal) investment in assets is hidden from view. Does that matter? Three tests suggest it is important. The first test is very broad brush, but revealing. Lev and Gu (2016) looked at companies that went public over each decade from the 1950s to the 2000s. For each of those decades/groups of companies, they asked: How correlated are book values and earnings to market values? Their results are very striking and set out in figure 9.2. The histogram bars show a very clear decline in the correlations over the decades, suggesting that financial accounts have indeed become much less informative of company earnings. This has occurred as R&D and SG&A (selling, general, and administrative expenses) as a percentage of sales has risen (see the solid line): the point being that many intangible investments, such as design, are allocated by accounting rules to SG&A.

Figure 9.2. The declining informativeness of earnings and book value reporting. Bars show fraction of variance in market values accounted for by earnings and book values for companies entering stock market in successive decade. Line shows average R&D and selling, general, and administrative expenses as a share of scales for companies. Source: Lev and Gu 2016, figure 8.2.

Second, Mary Barth, Ron Kasnik, and Maureen McNichols (2001) find that analysts are much more likely to cover firms with high intangible spending (measured by R&D and advertising). This too suggests that the accounts in intangible-intensive firms and industries are less informative, since it requires analysts’ know-how to ferret out additional information.

Third, the accountants Ester Chen, Ilanit Gavious, and Baruch Lev (2015) look at a sample of 180 Israeli firms over time that report using two different rules. The US-based GAAP compels firms to report R&D as expenses, but the IFRS, which is the norm for most European firms, allows the “D” in R&D to be capitalized. Thus the authors can do a direct test of whether the additional information on “D,” hidden from view under the GAAP rules, is informative. Sure enough, that additional information helps predict share prices.

What Should Investors Do?

In light of all this, equity investors have a couple of choices.

The first is to avoid the problem of finding out the information altogether, which is to buy shares in every company—that is, to diversify. That avoids an additional problem of spillovers. Consider the case of EMI and the CT scanner. If you were an EMI shareholder and cared only for your returns, you would have gladly seen investment in the CT scanner stopped—from EMI’s point of view, it was a colossal waste. But if you had also owned shares in General Electric and Siemens, the companies that got the spillover benefits of EMI’s research and came to dominate the CT scanning market, you would have been more than happy for the project to go ahead.

We can extend this example to a general principle. If shareholders owned stock in every company in the economy—in other words, if they were perfectly diversified investors—we would expect them to be totally tolerant of companies making investments with high spillovers. They would know that what they lost on swings, they would make up on roundabout, as the British saying goes. That is, what losses they incurred would be made up with offsetting gains.

But it seems there is a dilemma here. Diversified investors are the opposite of concentrated investors: if an institution owns stock in every company on an index, it will own much less stock in each company than if it owns stock in only a few companies. And, as we have seen, institutions whose shareholdings are concentrated in particular companies have a stronger interest in becoming knowledgeable enough about the business of those companies to know the difference between bad investments and good ones and, therefore, are more likely to back profitable but long-term investments by management. And this is the dilemma, from the point of view of anyone who is eager to see public companies making more long-term investments in intangible investments. On the one hand, investors with more concentrated stakes are a good thing, but on the other, so are diversified investors. Without concentrated investors, companies are less likely to invest in tamoxifens and Gigafactories; without diversified investors, they are less likely to invest in the CT scanner or in Bell Labs.

An alternative strategy arises if, as it seems, certain types of intangible investment tend to be systematically undervalued. This suggests there are opportunities for investors who can identify good intangible investments and back companies that make them over the medium term. What’s more, it suggests that time spent measuring and understanding the potential of various types of intangible investment may be worthwhile. While this might be too hard for individual investors, it seems like a possibility for asset managers in the future. They can serve investors by being much more canny about a firm, going beyond the information in the accounts. They are going to have to systematically gather much more information about the intangible-asset building that the firm is doing and the conditions for its success. Indeed, the demand for such expertise that understands the deep innards of the company and the way that external conditions will allow it to use its intangible assets will make these skills highly valued.

This vision is very much in line with the views of the economist John Kay in his book Other People’s Money (2015). As he says, stock markets, when first started, were the vehicles for raising finance often for large infrastructure projects (typically railways) from many dispersed shareholders. But markets no longer provide this function. Almost no new projects are financed via the stock market. (Indeed, the observation that few early-state companies come to the stock market for financing rather confirms the hypothesis that stock markets have significant problems dealing with them.) Rather, stock market trading is dominated by large asset managers trading with each other. In Kay’s view, they are searching for returns over and above those available to the market as a whole (searching for “alpha”) by trying to anticipate what others are thinking about the value of assets rather than the value of the underlying assets themselves.

A changed role for the financial sector, Kay argues, would be for finance to return to its core function of allocating capital via what he calls “search” and “stewardship.” Search is the finding of new opportunities and stewardship the monitoring of the long-term assets in the economy. Thus asset managers of the future, Kay suggests, might do much more of these functions for investors. Asset managers would do so by building trust and long-term relationships in the industries where they chose to make their expertise. With the building of intangible assets and the lack of information in company accounts, the pressures for this change are there.

Conclusion: Competing, Managing, and

Investing in an Intangible Economy

The growth of intangible investment has significant implications for managers, but it will affect different firms in different ways. Firms that produce intangible assets will want to maximize synergies, create opportunities to learn from the ideas of others (and appropriate the spillovers of others’ intangibles), and retain talent. These workplaces may end up looking rather like the popular image of hip knowledge-based companies. But companies that rely on exploiting existing intangible assets may look very different, especially where the intangible assets are organizational structure and processes. These may be much more controlled environments—Amazon’s warehouses rather than its headquarters. Leadership will be increasingly prized, to the extent that it allows firms to coordinate intangible investments in different areas and exploit their synergies.

Financial investors who can understand the complexity of intangible-rich firms will also do well. The greater uncertainty of intangible assets and the decreasing usefulness of company accounts put a premium on good equity research and on insight into firm management. This will present a challenge to investors, partly because funding equity analysis is becoming harder for many institutional investors as regulations are tightened, and partly because of the inherent tension between diversification (which allows shareholders to gain from the spillover effects of intangible investments) and concentrated ownership (which reduces the costs of analysis).