The UNITEXT – La Matematica per il 3+2 series is designed for undergraduate and graduate academic courses, and also includes advanced textbooks at a research level. Originally released in Italian, the series now publishes textbooks in English addressed to students in mathematics worldwide. Some of the most successful books in the series have evolved through several editions, adapting to the evolution of teaching curricula.

More information about this subseries at http://www.springer.com/series/5418

An Introduction to Algebraic Statistics with Tensors

Cover illustration (LaTeX): A decomposable 3-dimensional tensor of type $3\times 5\times 2$.

This Springer imprint is published by the registered company Springer Nature Switzerland AG

The registered company address is: Gewerbestrasse 11, 6330 Cham, Switzerland

We, the authors, dedicate this book to our great friend Tony Geramita. When the project started, Tony was one of the promoters and he should be among us in the list of authors of the text. Tony passed away when the book was at an early stage. We finished the book following the pattern traced in collaboration with him, and we always felt as if his encouragement to continue the project never faded.

Statistics and Algebraic Statistics

At the beginning of a book on Algebraic Statistics, it is undoubtedly a good idea to give the reader some idea of the goals of the discipline.

A reader who is already familiar with the basics of Statistics and Probability is probably curious about what the prefix “Algebraic” might mean. As we will see, Algebraic Statistics has its own way of approaching statistical problems, exploiting algebraic, geometric, or combinatorial properties. These problems are somewhat different from the one studied by Classical Statistics.

We will illustrate this point of view with some examples, which consider well-known statistical models and problems. At the same time, we will point out the difference between the two approaches to these examples.

The Treatment of Random Variables

The initial concern of Classical Statistics is the behavior of one random variable

. Usually

. Usually

is identified with a function with values in the real numbers. This is clearly an approximation. For example, if one records the height of the members of a population, it is unlikely that the measure goes much further than the second decimal digit (assume that the unit is

is identified with a function with values in the real numbers. This is clearly an approximation. For example, if one records the height of the members of a population, it is unlikely that the measure goes much further than the second decimal digit (assume that the unit is

m). So, the corresponding graph is a histogram, with a basic interval of

m). So, the corresponding graph is a histogram, with a basic interval of

m. This is translated to a continuous variable, by sending the length of the basic interval to zero (and the size of the population increases).

m. This is translated to a continuous variable, by sending the length of the basic interval to zero (and the size of the population increases).

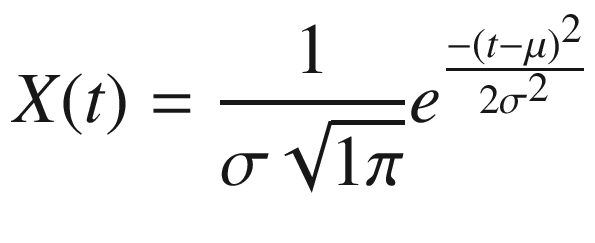

For random variables of this type, the first natural distribution that one expects is the celebrated Gaussian distribution, which corresponds to the function

where

and

and

are parameters which describe the

shape

of the curve (of course, other types of distributions are possible, in connection with special behaviors of the random variable

are parameters which describe the

shape

of the curve (of course, other types of distributions are possible, in connection with special behaviors of the random variable

).

).

The first goal of Classical Statistics is the study of the shape of the function

, together with the determination of its numerical parameters.

, together with the determination of its numerical parameters.

When two or more variables are considered in the framework of Classical Statistics, their interplay can be studied with several techniques. For instance, if we consider both the heights and the weights of the members of a population and our goal is a proof of the (obvious) fact that the two variables are deeply connected, then we can consider the distribution over pairs (height, weight), which is represented by a bivariate Gaussian, in order to detect the existence of the connection.

The starting point of Algebraic Statistics is quite different. Instead of considering variables as continuous functions, Algebraic Statistics prefers to deal with a finite (and possibly small) range of values for the variable

. So, Algebraic Statistics emphasizes the discrete nature of the starting histogram, and tends to group together values in wider ranges, instead of splitting them. A distribution over the variable

. So, Algebraic Statistics emphasizes the discrete nature of the starting histogram, and tends to group together values in wider ranges, instead of splitting them. A distribution over the variable

is thus identified with a discrete function (to begin with, over the integers).

is thus identified with a discrete function (to begin with, over the integers).

Algebraic Statistics is rarely interested in situations, where just one random variable is concerned.

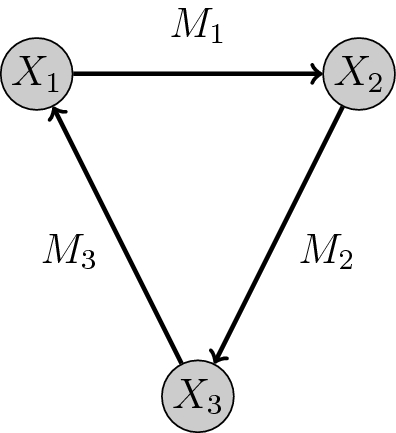

Are there connections between the two or more random variables of the network?

Which kind of connection is suggested by a set of data?

Can one measure the complexity of the connections in a given network of interacting variables?

Since, from the new point of view, we are interested in determining the relations between discrete variables, in Algebraic Statistics a distribution over a set of variables is usually represented by matrices, when two variables are involved, or multidimensional matrices (i.e., tensors), as the number of variables increases.

It is a natural consequence of the previous discussion that while the main mathematical tools for Classical Statistics are based on multivariate analysis and measure theory, the underlying mathematical machinery for Algebraic Statistics is principally based on the Linear and Multi-linear Algebra of tensors (over the integers, at the start, but quickly one considers both real and complex tensors).

Relations Among Variables

Just to give an example, let us consider the behavior of a population after the introduction of a new medicine.

Assume that a population is affected by a disease, which dangerously alters the value of a glycemic indicator in the blood. This dangerous condition is partially treated with the new drug. Assume that the purpose of the experiment is to detect the existence of a substantial improvement in the health of the patients.

In Classical Statistics, one considers the distribution of the random variable

the value of the glycemic indicator over a selected population of patients

before

the delivery of the drug, and the random variable

the value of the glycemic indicator over a selected population of patients

before

the delivery of the drug, and the random variable

the value of the glycemic indicator of patients

after

the delivery of the drug. Both distributions are likely to be represented by Gaussians, the first one centered at an abnormally high value of the glycemic indicator, the second one centered at a (hopefully) lower value. The comparison between the two distributions aims to detect if (and how far) the descent of the recorded values of the glycemic indicator is statistically meaningful, i.e., if it can be distinguished from the natural underlying ground noise. The celebrated

Student’s

the value of the glycemic indicator of patients

after

the delivery of the drug. Both distributions are likely to be represented by Gaussians, the first one centered at an abnormally high value of the glycemic indicator, the second one centered at a (hopefully) lower value. The comparison between the two distributions aims to detect if (and how far) the descent of the recorded values of the glycemic indicator is statistically meaningful, i.e., if it can be distinguished from the natural underlying ground noise. The celebrated

Student’s

-test

is the world-accepted tool for comparing the means of two Gaussian distributions and for determining the existence of a statistically significant response.

-test

is the world-accepted tool for comparing the means of two Gaussian distributions and for determining the existence of a statistically significant response.

In many experiments, the response variable is binary or categorical with

levels, leading to a

levels, leading to a

, or a

, or a

, contingency table. Moreover, when there is more than one response variable and/or other control variables, the resulting data are summarized in a multiway contingency table, i.e., a tensor.

, contingency table. Moreover, when there is more than one response variable and/or other control variables, the resulting data are summarized in a multiway contingency table, i.e., a tensor.

This structure may also come from the discretization of a continuous variable. As an example, consider a population divided into two subsets, one of which is treated with the drug while the other is treated with traditional methods. Then, the values of the glycemic indicator are divided into classes (in the roughest case just two classes, i.e., a threshold which separates two classes is established). After some passage of time, one records the distribution of the population in the four resulting categories (treated + under-threshold, treated + over-threshold

) which determines a

) which determines a

matrix, whose properties encode the existence of a relation between the new treatment and an improved normalization of the value of the glycemic indicator (this is just to give an example: in the real world, a much more sophisticated analysis is recommended!).

matrix, whose properties encode the existence of a relation between the new treatment and an improved normalization of the value of the glycemic indicator (this is just to give an example: in the real world, a much more sophisticated analysis is recommended!).

Bernoulli Binary Models

Another celebrated model, which is different from the Gaussian distribution and is often introduced at the beginning of a course in Statistics, is the so-called Bernoulli model over one binary variable.

Assume we are given an object that can assume only two states. A coin, with the two traditional states

(heads) and

(heads) and

(tails), is a good representation. One has to bear in mind, however, that in the real world, binary objects usually correspond to

biased

coins, i.e., coins for which the expected distribution over the two states is not even.

(tails), is a good representation. One has to bear in mind, however, that in the real world, binary objects usually correspond to

biased

coins, i.e., coins for which the expected distribution over the two states is not even.

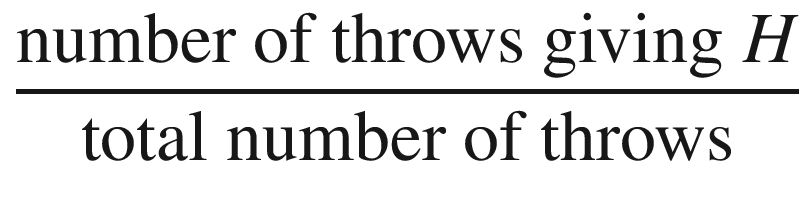

If

is the

probability

of obtaining a result (say

is the

probability

of obtaining a result (say

) by throwing the coin, then one can roughly estimate

) by throwing the coin, then one can roughly estimate

by throwing the coin several times and determining the ratio

by throwing the coin several times and determining the ratio

but this is usually considered too naïve. Instead, one divides the total set of throws into several packages, each consisting of

throws, and determines for how many packages, denoted

throws, and determines for how many packages, denoted

, one obtained

, one obtained

exactly

exactly

times. The value of the constant

times. The value of the constant

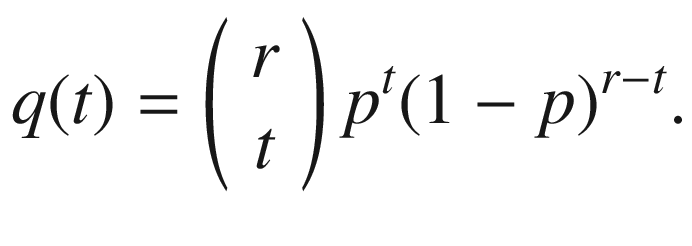

is thus determined by Bernoulli’s formula:

is thus determined by Bernoulli’s formula:

By increasing the number of total throws (and thus increasing the number of packages and the number of throws

in each package), the function

in each package), the function

tends to a real function, which can be treated with the usual analytic methods.

tends to a real function, which can be treated with the usual analytic methods.

Notice that in this way, at the end of the process, the discrete variable

Coin

is substituted by a continuous variable

. Usually one even goes one step further, by substituting the variable

. Usually one even goes one step further, by substituting the variable

with its logarithm, ending up with a linear description.

with its logarithm, ending up with a linear description.

Algebraic Statistics is scarcely interested in knowing how a single given coin is biased. Instead, the main goal of Algebraic Statistics is to understand the connections between the behavior of two coins. Or, better, the connections between the behavior of a collection of coins.

have a fixed combination of states. The distribution is transformed into a tensor of type

have a fixed combination of states. The distribution is transformed into a tensor of type

. All coins can be biased, with different loads: this does not matter too much. In fact, the main questions that one expects to solve are

. All coins can be biased, with different loads: this does not matter too much. In fact, the main questions that one expects to solve are

Are there connections between the outputs of two or more coins?

Which kind of connection is suggested by the distribution?

Can one divide the collection of coins into clusters, such that the behavior of coins of the same cluster is similar?

Answers are expected from an analysis of the associated tensor, i.e., in the framework of Multi-linear Algebra.

The importance of the last question can be better understood if one replaces coins with positions in a composite digital signal. Each position has, again, two possible states, 0 and 1. If the signal is the result of the superposition of many elementary signals, coming from different sources, and digits coming from the same source behave similarly, then the division of the signal into clusters yields the reconstruction of the original message that each source issued.

Splitting into Types

Of course, the separation of several phenomena that are mixed together in a given distribution is also possible using methods of Classical Statistics.

In a famous analysis of 1894, the biologist Karl Pearson made a statistical study of the shape of a population of crabs (see [1]). He constructed the histogram for the ratio between the “forehead” breadth and the body length for 1000 crabs, sampled in Naples, Italy by W. F. R. Weldon. The resulting approximating curve was quite different from a Gaussian and presented a clear asymmetry around the average value. The shape of the function suggested the existence of two distinct types of crab, each determining its own Gaussian, that were mixed together in the observed histogram. Pearson succeeded in separating the two Gaussians with the method of moments . Roughly speaking, he introduced new statistical variables, induced by the same collection of data, and separated the types by studying the interactions between the Gaussians of these new variables.

This is the first instance of a computation which takes care of several parameters of the population under analysis, though the variables are derived from the same set of data. Understanding the interplay between the variables provides the fundamental step for a qualitative description of the population of crabs.

From the point of view of Algebraic Statistics, one could obtain the same description of the two types which compose the population by adding variables representing other ratios between lengths in the body of crabs, and analyzing the resulting tensor.

Mixture Models

Summarizing, Algebraic Statistics becomes useful when the existence and the nature of the relations between several random variables are explored.

We stress that knowing the shape of the interaction between random variables is a central problem for the description of phenomena in Biology, Chemistry, Social Sciences, etc. Models for the description of the interactions are often referred to as Mixture Models . Thus, mixture models are a fundamental object of study in Algebraic Statistics.

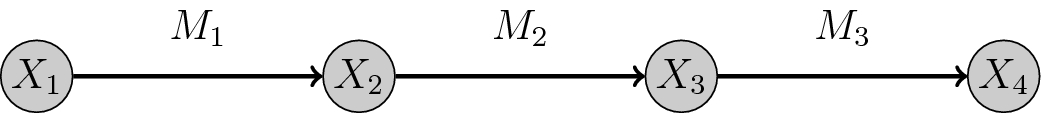

Perhaps, the most famous and easily described mixture models are the

Markov chains

, in which the set of variables is organized in a totally ordered chain, and the behavior of the variable

is only influenced by the behavior of the variable

is only influenced by the behavior of the variable

(usually, this interaction depends on a given matrix).

(usually, this interaction depends on a given matrix).

Of course, much more complicated types of networks are expected when the complexity of the collection of variables under analysis increases. So, when one studies composite signals in the real world, or pieces of a DNA chain, or regions in a neural tissue, higher level models are likely to be necessary for an accurate description of the phenomenon.

In Classical Statistics, the structure of the connections among variables is often a postulate. In Algebraic Statistics, determining the combinatorics and the topology of the network is a fundamental task. On the other hand, the time-dependent activating functions that transfer information from one variable to the next ones, deeply studied by Classical Statistics, are of no immediate interest for Algebraic Statistics which, at first, considers steady states of the configuration of variables.

The Multi-linear Algebra behind the aforementioned models is not completely understood. It requires a deep analysis of subsets of linear spaces described by parametric or implicit polynomial equations. This is the reason why, at a certain point, methods of Algebraic Geometry are invoked to push the analysis further.

Conclusion

The way we think about Algebraic Statistics focuses on aspects of the theory of random variables which are different from the targets of Classical Statistics. This is reflected in the point of view introduced in the book. Our general setting differs from the classical one and is closer to the one implicitly introduced in the books of Pachter and Sturmfels [2] and Sullivant [3]. Our aim is not to create a new formulation of the whole statistical theory, but only to present an algebraic natural way in which Statistics can handle problems related to mixture models.

The discipline is currently living in a rapidly expanding network of new insights and new areas of application. Our knowledge of what we can do in this area is constantly increasing and it is reasonable to hope that many of the problems introduced in this book will soon be solved or, if they cannot be solved completely, then they will at least be better understood. We feel that the time is right to provide a systematic foundation, with special attention to the application of tensor theory, for a field that promises to act as a stimulus for mathematical research in Statistics, and also as a source of suggestions for further developments in Multi-linear Algebra and Algebraic Geometry.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to warmly thank Fabio Rapallo, who made several fruitful remarks and suggestions to improve the exposition, especially regarding the connections with Classical Statistics.

References

- 1.

Pearson K.: Contributions to the mathematical theory of evolution. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. London A, 185 , 71–110 (1894)

- 2.

Pachter, L., Sturmfels, B.: Algebraic Statistics for Computational Biology. Cambridge University Press, New York (2005)

- 3.

Sullivant, S.: Algebraic Statistics. Graduate Studies in Mathematics, vol. 194, AMS, Providence (2018)

Contents

About the Authors

Prof. Cristiano Bocci

is Assistant Professor of Geometry at the University of Siena (Italy). His research concerns Algebraic Geometry, Commutative Algebra, and their applications. In particular, his current interests are focused on symbolic powers of ideals, Hadamard product of varieties, and the study of secant spaces. He also works in two interdisciplinary teams in the fields of Electronic Measurements and Sound Synthesis.

Prof. Luca Chiantini

is Full Professor of Geometry at the University of Siena (Italy). His research interests focus mainly on Algebraic Geometry and Multi-linear Algebra, and include the theory of vector bundles on varieties and the study of secant spaces, which are the geometric counterpart of the theory of tensor ranks. In particular, he recently studied the relations between Multi-linear Algebra and the theory of finite sets in projective spaces.