Megaloprepeia

Il est difficile de vivre dans un monde dont le support productif est l’argent.1

Mephisto: Yes it is I who have been deceived I the devil who no one can deceive yes it is I who have been deceived.2

CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY

Economics originated in and has never completely broken with moral philosophy. A president of the American Economic Association recalled in 1968 that “when I was a student, economics was still part of the moral sciences tripos at Cambridge University.” On the grounds of the discipline’s history and its vocabulary (goods, utility, satisfaction) and because

the fundamental principle that we should count all costs … and evaluate all rewards … is one which emerges squarely out of economics and which is at least a preliminary guideline in the formation of the moral judgment,

“mathematical ethics” is a plausible name for the dismal science.3 So the explosion of finance mathematics, and its implication in the 2008 crash, has had the welcome, but unintended, consequence of establishing a common border between mathematics and morality. Somebody was to blame for the crisis, and primitive retribution was on the minds of many. Protestors against the September 2008 bank bailout invited Wall Street bankers to “Jump!” “Uncle Sam wants your money,” a Forbes headline screamed, “and the crowd outside the gate wants your head.” The newly elected President Obama warned a group of businesspeople that “My administration is the only thing between you and the pitchforks.”4

I had spent the spring of 2008 visiting Columbia University, adding monthly to my pension and watching its balance drift slowly back down to its previous value before the next month’s installment, in that spring’s market of slow decline. Manhattan mathematical geography was, therefore, still vivid in my mind when the collapse of the Lehman Brothers triggered the crash later that year, and was conspicuous in my own visions of retribution. All that fall and through the next spring, I would wake up having dreamed of crucified engineers of quantitative finance—the so-called quants—lining the 7.7 miles of Broadway joining the Columbia mathematics department with Wall Street, with a brief rally to the left at 34th Street, stopping at the CUNY Graduate Center, and then a dip to the right at 8th Street to NYU’s Courant Institute (“a top quant farm” since the 1990s), in an ironic class reversal of the suppression of the Spartacus slave revolt by the future triumvir Marcus Licinius Crassus.5

I’m not being completely candid: those weren’t quants up on the lampposts, they were mathematics professors. Hadn’t Warren Buffett, as early as 2002, referred to derivatives as “financial weapons of mass destruction”? Hadn’t former French prime minister Michel Rocard gestured at the border between mathematics and morality in 2008 and accused the “math professors who teach their students how to make a killing on the market” of “crime[s] against humanity”?6 It’s now routine to refer to much of what goes on in finance as criminal—“prima facie criminal behavior,” in the words of economist Jeffrey Sachs. Charles Ferguson wrote Predator Nation, subtitled Corporate Criminals, Political Corruption, and the Hijacking of America, in part “to lay out in painfully clear detail the case for criminal prosecutions”—“What is this,” he writes, “if not organized crime?”—and his point of view is hardly marginal; his documentary Inside Job won an Oscar in 2011, while in 2013 Britain’s Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards “envisages a new approach to sanctions and enforcement against individuals,” including the establishment of a “criminal offence” with “Senior Persons” liable to imprisonment.7

But the equation of finance with criminality is usually based on acts, not ideas. Though Rocard stopped short of suggesting that mathematics professors be hauled before the International Criminal Court,8 the notion that mathematicians could do something reprehensible was novel enough to generate six months’ worth of heated rejoinders. Three of my eminent Paris colleagues asked whether politicians like Rocard weren’t “much more guilty than mathematicians by not imposing real restrictions on the risks” taken by financial institutions.9 Even before Le Monde published Rocard’s accusation and again in the months that followed, French specialists in finance mathematics wrote articles and gave lectures in which they acknowledged the need for “a minimum of ethics,” but insisted that banking culture and lax public supervision were responsible for the use of mathematical techniques without regard to their manufacturers’ guidelines. “It’s clear,” wrote Marc Yor, professor at the Université Pierre et Marie Curie, better known as Paris 6, “that mathematicians have got caught in an infernal spiral,” but the creation of subprimes or the seventy-year mortgages in Spain “are not really the fault of mathematicians.” Nicole el-Karoui, also of Paris 6 and the École Polytechnique, suggested that a mathematical model may be “reasonable” at 100,000 € but not when the sums involved are much greater.10

Others found these arguments disingenuous. Two mathematicians claimed to have heard “students freshly sharpened by our university programs boasting of having created speculative products on stocks of basic necessities.” While Marc Rogalski argued that financial mathematics is “directed essentially toward acquiring techniques for increasing the rate of financial profits” and wondered whether “mathematics [should] be on the owners’ and stockholders’ side in the class struggle,” the late Denis Guedj, author of The Parrot’s Theorem, wrote in Liberation that he saw the mathematicians who chose to join “the camp of the powerful” as “enemies … working for the misfortunes of the majority….”11

One crash later, not much has changed. The Oxford-Man Institute for Quantitative Finance has been “going from strength to strength”12 since it opened its doors in late 2007, just down the road from Oxford’s Mathematical Institute. In Paris, you can read about the “explosion of the financial risk industry” on the Web site for the “Probability and Finance” program run by Karoui, Yor, and their colleagues at Paris 6 and the École Polytechnique; any allusions there to professional ethics are in print too fine for my eyes. There is no shortage of candidates. At the École Polytechnique, the most élitist of French engineering schools, 70% of mathematics majors aim at a career in finance; the École Centrale, only slightly less prestigious, had “become a school of managers,” much to the regret of an official responsible for mathematics education.13 Even the venerable École des Ponts et Chaussées (School of Bridges and Roads), one of the grandest of the Grandes Écoles, offers a masters program that diverts a sizable proportion of its graduating class onto the virtual highway of quantitative finance.

$ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥

During the 2012 French presidential campaign, economics minister François Baroin dismissed the opposition’s proposals on the grounds that “attacking finance is as idiotic as saying ‘I’m against rain,’ ” (or cold, or fog), while Prime Minister François Fillon advised the Socialist Party candidate to run his electoral platform by Standard & Poor’s.14 Rosa Luxemburg, criticizing the Russian revolution, wrote that “Freedom is always the freedom of those who think otherwise.” But what use is the freedom to be against lousy weather?

The equations of mathematical economics are peculiar in that their variables are already familiar as characters in a morality play, actors in a cosmic drama: Investor (Capital)—the prime mover, Finance, Industry, State, Labor, Consumer. Messieurs Baroin and Fillon distantly echo Margaret Thatcher’s motto—TINA: There Is No Alternative—rooted in a worldview that places market forces and natural forces on the same metaphysical plane.15 I have nothing to add to the rich literature on this topic and on the origins of the crisis of 2008 beyond a few reflections on the new mathematically trained member of the cast: Quant, the mathematical engineer whose job is to protect investments from the hazards of finance, just as Ponts et Chaussées graduates used to brace their bridges against the perils of gravity.16

The consensus is that, Rocard’s allegations notwithstanding, the quant is not a crook. Ferguson’s subtitle alludes to “corporate criminals” and “political corruption,” and most of his text is a scathing indictment of bankers; mathematicians get off the hook—as they do in Scott Patterson’s The Quants, a journalistic melodrama in four personalities and four overlapping mathematical models, which accuses financial engineers of hubris, greed, and misjudgment but not of criminal intention. Quant is merely one of the Evil Principle’s minions, like Goethe’s Mephistopheles, who defines himself in Euclidean fashion as “a part of the Power that always wills the Evil, and always creates the Good.”

How should finance mathematics define itself? Adam Smith anticipated the main source of instability of financial markets—leveraging—with his customary clarity:

The interest of money is always a derivative revenue, which, if it is not paid from the profit which is made by the use of the money, must be paid from some other source of revenue, unless perhaps the borrower is a spendthrift, who contracts a second debt in order to pay the interest of the first.17

Financial engineering makes life profitable for Smith’s spendthrifts by endlessly recombining their multiple debts into financial derivatives, obligations denominated in virtual money, in order to continue to rack up profits while postponing the day of repayment. The impossibility of exponential growth in the real world is what brings down all Ponzi schemes, and the real estate bubble whose bursting in 2007 led inexorably to the cascade of banking and insurance failures was no exception. But wealth was already largely virtual when Smith sought to reveal its guiding principles. Referring to Renaissance innovations in paper money and credit (“bills of exchange”), Fernand Braudel wrote that “this type of money that was not money at all, and this juggling of money and book-keeping to a point where the two became confused, seemed not only complicated but diabolical.”18 It’s a recurrent image in Braudel’s work, and he’s on to something. Here is Mephistopheles himself, in Faust, part II, explaining his invention of paper money to the emperor:

Such paper’s convenient, for rather than a lot

Of gold and silver, you know what you’ve got,

… Since the paper, in this way, pays for itself,

It shames the doubters, and their acid wit,

People want nothing else, they’re used to it.

The emperor thanks Mephistopheles for his innovation:

The Empire thanks you deeply for this bliss:

We want the reward to match your service.

We entrust you with the riches underground,

You are the best custodians to be found.

… your roles make the Underworld, and the Upper,

Happy in their agreement, fit together.19

Once Mephistopheles has his hands on “the riches,” he will not readily let go. But the Fiend’s inspiration was superfluous when it came time to price financial derivatives; a Nobel Prize–winning team of economists had inspiration enough.

The natural world is not always predictable; human beings don’t always keep their promises. Aristotle examined the first source of uncertainty in his Physics and Metaphysics, the second in his Nicomachean Ethics. The financial risk market provides instruments to protect against either form of uncertainty. Most readers know that an option is a kind of bet on the future value of an investment (such as a stock, a bond, or a commodity). They, and more complex derivatives, can be used to insure against unexpected changes in crop prices, or accidents, or the failure of borrowers to repay their debts. This sort of thing is at least as old as Greek mathematics itself. In his Politics, Aristotle recalls how Thales purchased options on the use of “all the olive-presses in Chios and Miletus” and “made a quantity of money” when the harvest was unusually rich. Aristotle’s conclusion, which the reader is encouraged to keep in mind while reading this chapter, is “that philosophers can easily be rich if they like, but that their ambition is of another sort.”20

Derivatives can also be used for purposes of pure speculation. “Thanks to mathematics, the financial risk market works, roughly speaking [à peu près].” That was Karoui, quoted in the French business press in 2005, explaining her fear that a “Tobin tax”—a small tax on financial transactions proposed (years before) by James Tobin to discourage parasitic speculation—would “collapse the fragile edifice patiently constructed over decades.”21 The foundation of the edifice was the Black-Scholes equation, invented (or discovered?) in 1973 by Fischer Black and Myron Scholes, soon joined by Robert C. Merton (son of the Merton who named the Matthew Effect). Patterson, with a flair for overstatement, describes what Black-Scholes wrought:

Just as Einstein’s discovery of relativity theory in 1905 would lead to a new way of understanding the universe, as well as the creation of the atomic bomb, the Black-Scholes formula dramatically altered the way people would view the vast world of money and investing. It would also give birth to its own destructive forces and pave the way to a series of financial catastrophes, culminating in an earthshaking collapse that erupted in August 2007.

Ten years earlier, just a few months after Merton and Scholes shared the 1997 Nobel Prize in Economics, Long Term Capital Management, which managed hedge funds in large part on the basis of the Black-Scholes model, had collapsed, along with the finances of much of East Asia and Russia. The catastrophe seemed earthshaking at the time, but the losses were a thousand times greater in 2008 (and they continue to mount).22

It’s not the equations that make it difficult for a mathematician like me to grasp quantitative finance. My problem is with adopting the psychology, the motivations, the persona of Investor, rational economic agent, and invariable protagonist of the allegory through which politicians, the mainstream press, and the finance math textbooks ram the moral lessons of public economic policy into popular consciousness. Someone who (that TIAA-CREF account notwithstanding) has never aspired to playing Investor, a figure whose cardinal virtue is maximizing returns, is at a distinct disadvantage. This is one reason I am grateful for sociologist Donald MacKenzie’s lucid deconstruction of the allegory, in an impressive series of articles and books. In an analytic history of Black-Scholes, MacKenzie called option-pricing theory performative: “it did not simply describe a pre-existing world, but helped create a world of which the theory was a truer reflection.” More precisely, “The availability of the Black-Scholes formula, and its associated hedging techniques, gave participants the confidence to write options at lower prices, … helping options exchanges to grow and to prosper, becoming more like the markets posited by the theory … the model [was] used to make one of its key assumptions a reality.”23 If we are tempted to view Ngô’s proof of the fundamental lemma as “performative”—both because it brought a stage of the Langlands program to maturity and because by borrowing the Hitchin fibration from its home in a different part of geometry, it revised our understanding of the interrelations among central branches of mathematics—we can say that the Black-Scholes model was performative in the latter sense, with incomparably more profound material consequences.

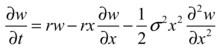

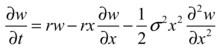

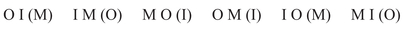

Figure 4.1. The Black-Scholes partial differential equation. Here x is the price of the underlying stock or other security, w is the price of the derivative as a function of x and time t, r is the riskless rate of return, and σ is a measure of volatility.

APPLIED STOCHASTIC ANALYSIS

[A]s the mathematics of finance reaches higher levels so the level of common sense seems to drop.24

“You’re in for it now” is what the Time Traveller told himself when he descended into the underground world of H. G. Wells’s Time Machine. And that’s what I told myself in 2000 at the European Congress of Mathematicians in Barcelona, when a speaker at a round table on the future of mathematics hailed the recent explosion of finance mathematics that providentially brought so many undergraduate and masters’ students to our departments’ lonely corridors.25 A visit to Columbia in 2004 revealed the full scope of the phenomenon. A colleague boasted that Columbia’s mathematical finance program was underwriting the lavish daily spreads of fresh fruit, cheese, and chocolate brownies, when other departments, including mine in Paris, were lucky to offer a few teabags and a handful of cookies to calorie-starved graduate students. I spent a month living on my own, and when I walked down the stairs after staying late at the office, even at 9 or 10 p.m., I could hear traders, sent up by their Wall Street offices, struggling with their late-night equations. It brought to mind Morlocks, the underground-workers Wells’ Time Traveller encountered at the bottom of his descent, toiling in the darkened basement of applied stochastic analysis to provide fresh fruit for the daily teas of the sunny Eloi of pure mathematics. A crater still disfigured lower Manhattan when I returned for a longer visit four years later, but the city’s economy had rebounded and traders were still staying overtime for basement classes. Then, in one of those ironic reversals that are much more entertaining when they take place in a novel set 800,000 years in the future than when they unfold in real time with us in the middle, the Morlock traders turned out to be too big to fail, which entailed not literally eating all the rest of us, but setting us to working for the foreseeable future to bail them out.

[Two colleagues, having read to this point, gently but firmly advised me to remove this chapter from the book, suggesting independently that this sort of talk is “more suitable for conversations over coffee” in the common room (with or without fresh fruit) “than for a serious book.” Regarding the seriousness expected of an author with my degree of charisma, the reader is directed to chapter 8. More troubling is that both my colleagues seem to have missed my disclaimers. So I repeat them here, more explicitly. My purpose is not to assign responsibility for the 2008 crash and certainly not to imply that mathematics professors are specifically to blame. Nor, as I write shortly, does this chapter aim to change anyone’s mind about fundamental questions of economic policy. Its primary purpose, rather, is to explain some of the context for a debate that is actually taking place, within and around mathematics, in connection with the growth of mathematical finance. The tensions between the internal and external goods, in MacIntyre’s sense, involved in the creation of mathematics, are well illustrated by this debate; to expose these tensions is not to take sides. Readers will have no trouble guessing what I believe, but I don’t necessarily expect them to agree with me.

The secondary purpose of this chapter is to provide a very brief introduction to the mathematical modeling of reality. Thus, we return to the main narrative.] Stochastic analysis is the marriage of probability theory with calculus, mathematics’ two main contributions to modeling physical reality. A deterministic model is one that allows exact prediction of the future state of a system on the basis of knowledge of the present, combined with relevant physical laws. Deterministic laws typically take the mathematical form of differential equations.26 Physicists represent the state of a physical system—like the global climate—by functions that encode the numerical values of relevant quantities. In the case of the global climate, these quantities would include (among many others) temperature, concentration of certain gases and particles in the atmosphere, surface reflectivity, and the earth’s position relative to the sun. Most of these quantities vary, depending on time and position, and when we assign the temperature (say) to every point on the earth’s surface at every time, we define a function of position and time. We can’t really measure temperature at every point and every time, but it is regularly measured at certain positions and times, and this measure provides a model of the abstract temperature function as well as an input for the daily weather report.

Physical laws predict how quantities of interest influence one another mutually, and this prediction takes the form of a differential equation whose solutions include the future values of functions that represent the state of the system: solving the differential equations determines how physical quantities evolve in time. This is the kind of information we want to know: the prediction of global warming is the claim that, with the passage of time, the average temperature at any given place is likely to increase, eventually with catastrophic consequences. This is read from the output of the model, which is an expression for the temperature function—call it T for temperature—that includes not only past values, which can be measured, but also future values, which we can also measure—but only when it’s too late to do anything about them. Solving the differential equation to find the function T is in every way analogous to solving a polynomial equation like y2 = x3 − x (cf. chapter β) except that (1) we are finding not a number or pair of numbers but rather a way to assign a number (temperature) to every point on the earth’s surface at a given time in the future and (2) the differential equation is not a simple algebraic expression but rather a means for determining how T changes in time and space as a result of interaction with the other factors.

Since these factors are changing simultaneously, in part in response to changes in T, there are multiple feedback effects, and the solution of differential equations is extremely difficult both conceptually and technically. A difference (rather than differential) equation, in which time is measured in discrete units, is simpler but works the same way. Here is Stable Equilibrium, a difference equation game you can play at your next dinner party. You are seated around a circular table; the initial conditions for the equation are the amount of money each of you has brought to dinner. At regular intervals, you give 10% of your money to each of your neighbors to the right and left, and the others do likewise. Since, at each move, each of you gives away a fixed proportion of what you have, you might expect that after enough time has passed, you will all have the same amount of money, and this is indeed what happens, though it may take many lifetimes (or play has to be exceedingly rapid) if the initial distribution is highly unequal.

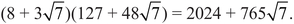

Stable Equilibrium is a discrete model of the diffusion of heat in a ring. It’s technically a difference equation on a graph (see chapter 7) and, although it’s analogous to some models in economics in that it demonstrates evolution to an equilibrium position, it’s clearly a silly example—experience shows that heat flows from warmer to colder bodies but that money trickles up from poorer to richer. Figure 4.3 illustrates the Matthew Effect difference equation game (rules based on Matthew 25:29; see chapter 2, note 27): instead of receiving from each neighbor 10% of his or her wealth, you receive 10% of your own. At the start, one player has $1.01 and all the others have $1.00. After 127 iterations, half the players are quadrillionaires and the other half are quadrillions in debt. In this game, initial conditions are preserved indefinitely if they are precisely equal, but this is an unstable equilibrium: a slight change of the initial conditions leads to an enormous change in the outcome.

Figure 4.3. The Matthew Effect difference equation game illustrates in simplified form the danger that leveraging on the basis of exponential growth will lead to a vicious circle of rapidly expanding debt. At some point Standard and Poor’s or some other rating agency casts doubt on the ability of some of the players to repay the quadrillions they owe, and the entire system unravels in short order.

Both games illustrate the kind of information differential equations provide, and both also exhibit an obvious circular symmetry: if all the participants straggled simultaneously one seat to the right, moneybags in hand, the rules of the game would not change.27 And both games are deterministic in the sense that every time they are played, the outcome is completely determined by the initial conditions; There Is No Alternative, as Thatcher would say. But how many times would you want to play a game whose outcome is known in advance, like tic-tac-toe?28 That would be boring! The soldier in Stravinsky’s A Soldier’s Tale becomes fabulously wealthy when he hands over his violin to the devil in exchange for a book that—deterministically—predicts the future; but such a book is only useful to an owner who possesses the unique (insider) copy. The Black-Scholes model, in contrast, is based on a stochastic differential equation: it doesn’t determine exact future values of a stock—that would be truly diabolical—but rather uses a probabilistic model of the range of possible values to calculate the “correct” price of an option.

We could incorporate stochasticity—randomness—into our deterministic party games. At each round, for example, each player might flip a coin: heads means hand over 10% of your neighbor’s wealth; tails, 10% of your own wealth. Some rounds are played like Stable Equilibrium, some like Matthew Effect, and most are a mixture of the two. Like a board game or like casino gambling, the randomness the coin toss introduces means the outcome will be different each time the game is played. Probability theory calculates your expected winnings—your average take if you play the game thousands or millions of times—but it can’t tell you whether you’ll have enough money left for cab fare home when the party’s over.

Generations of philosophers have racked their brains trying to reconcile the random aspects of life in human society with a deterministic worldview—or with free will, for that matter.29 A rational Ponts et Chaussées engineer will use deterministic models to design bridges to withstand extreme stress—a once-in-a-thousand-year earthquake, for example. But once in a thousand years is a probabilistic prediction that means only that the number of earthquakes will get closer and closer to the number of 1000-year periods that elapse as we march toward eternity: what is the philosophical status of such a claim? A rational agent at the investment casino will eschew philosophers and will look instead for a broker with a credible model to maximize expected winnings while minimizing risk. Being rational, the agent may prefer not to bet the pension on which his or her survival depends. But Wall Street culture loves risk! Patterson’s The Quants traces the dominant models in quantitative finance back to a 1962 book entitled Beat the Dealer and enlivens his narrative of investment house routine, not with dreary columns of figures (like figures 4.2 and 4.3) but with adrenaline-charged vignettes of high-risk poker games, extreme sports, and emotional volatility. “The greatest gambling game on earth is the one played daily through the brokerage houses across the country.”30

“It is not the least of the paradoxes,” writes David Steinsaltz in the AMS Notices, “that Patterson’s protagonists eagerly seek risk in gambling, while their core mathematical models presume that investors pay a premium to dispose of risk.” The Black-Scholes model is an equation expressing the insight of what Ivar Ekeland calls the “three fundamental theorems [of] mathematical finance,” all of which say exactly the same thing: “If you take no risk, you get the riskless rate.” The riskless rate is the marvelous feature of modern economies that lets money grow just by staying in the bank (not much these days). Since an option can be used to hedge against potential losses—for example, you can buy the option of selling a share of stock (or a ton of wheat) at a fixed strike price at a fixed date in the future—the price of the option should reflect just what is needed to compensate the risk of loss, compared to the riskless rate, so that “as the asset price increases (or decreases) the option value increases (or decreases) and the sum of the two, suitably weighted, will remain constant … equating the return on the … [riskless] portfolio with the bank rate of interest results in … the Black-Scholes equation.”31

Terence Tao devoted a lengthy blog entry to the reasoning that Black, Scholes, and Merton used to obtain the equation in figure 4.1, which calculates the price of an option as a function of the price of the underlying “instrument.” The Black-Scholes-Merton model caused quite a sensation at the time (1973) because the equation expresses a deterministic relation between option prices and stock prices, while the prices themselves vary stochastically in time. Tao emphasized that the model, while mathematically appealing, depends for its validity on a series of unrealistic hypotheses.32 Financial analyst Paul Wilmott agrees—“The world of markets doesn’t exactly match the ideal circumstances Black-Scholes requires”—but argues that “the model is robust because it allows an intelligent trader to qualitatively adjust for those mismatches. You know what you are assuming when you use the model, and you know exactly what has been swept out of view.” On the other hand, once the Black-Scholes paradigm made options pricing performative, common sense abandoned even the most intelligent traders. The modeling of CDOs—collateralized debt obligations, the derivatives most responsible for magnifying the mortgage crisis and nearly bringing the house down—is “confusedly elegant,” according to Wilmott. “The CDO research papers apply abstract probability theory to the price co-movements of thousands of mortgages…. all uncertainty is reduced to a single parameter that, when entered into the model by a trader, produces a CDO value…. over-reliance on probability and statistics is a severe limitation.” Like Aristotle, Wilmott favors causal over chance relations: “Statistics is shallow description, quite unlike the deeper cause and effect of physics, and can’t easily capture the complex dynamics of default.”33

$ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥

Aristotle sounds uncharacteristically cynical when he writes about debt, in the section of the Nicomachean Ethics devoted to friendship:

Benefactors are thought to love those they have benefited, more than those who have been well treated love those that have treated them well, and this is discussed as though it were paradoxical. Most people think it is because the latter are in the position of debtors and the former of creditors; and therefore as, in the case of loans, debtors wish their creditors did not exist, while creditors actually take care of the safety of their debtors … (Book IX, 7).

Proponents of finance math, in contrast to Aristotle, are upbeat when they insist on its utility and have no trouble justifying “mortgage-backed securities, the root of our present problems.” For everyone who wants to buy a home, there has to be an investor willing to provide the capital for the loan. “Today, foreign institutions have the big money—and they would not make deposits in U.S. Savings and Loans even if such institutions were available.” If Southwest Airlines has a long string of profitable quarters, it’s “because it used derivative securities to hedge against price increases” of jet fuel. Derivatives, we are told, allow international firms “to hedge currency risk” and insurance firms to “hedge against increases in longevity. The quants,” their defenders conclude, “did not create derivative securities … [they] help us understand them, price them, trade them and manage the risk associated with them.”34

Opponents also invoke utilitarian arguments but come to different conclusions. “Despite what some academics (primarily in business schools) claimed, the vast sums of money channeled through Wall Street did not improve America’s productive capacity by ‘efficiently allocating capital to its best use.’ ” On the contrary, their “financial chicanery, outrageous compensation packages, and bubble-infected stock price valuations” have actually “diminished the country’s productivity.” Another opponent adds: “It has been claimed that the increasing use of borrowing is an inevitable part of economic growth, and that the rise of global finance is necessary to sustain a globalised world economy. A more sceptical view is that much of the recent economic growth in the West is illusory, since it is based on the higher and higher levels of debt made possible by ill-conceived deregulation and financial experimentation.”35

That’s a nice summary of the massive literature that has been filling best seller lists since the crash. Readers will have decided for themselves which of the preceding accounts is most credible; this chapter does not aim to change anyone’s mind. What’s not in dispute is that the derivatives markets have grown to account for roughly ten times the total annual product of the entire planet36 and that this has been made possible by the mathematical innovations of the last few decades. How have future quants been prepared for the inevitable ethical challenges of the new situation?

Less than a year after they reacted to Rocard’s outburst, the directors of France’s leading financial mathematics program invoked the virtue of expertise favored by the markets. Quants engage in “two types of activity: developing “derivatives (options, warrants, swaps …)” where the quant “often participates along with … traders, structurers or … clients … essentially as an expert to assess amenability to mathematical treatment”; and “global risk management” for which “[h]e [sic] must … design (in part) and calculate an array of indicators of short-and medium-term risk….” Growth is anticipated in areas “such as energy and climate derivatives” and “the creation of markets in polluting rights.”37 A popular American textbook (now in its ninth edition at a list price of $333) explains no less technocratically that “derivative markets provide a means of managing risk, discovering prices, reducing costs, improving liquidity, selling short, and making the market more efficient” but does not shrink from addressing the underlying ethical questions, however briefly:

An important distinction between derivative markets and gambling is in the benefits provided to society. Gambling benefits only the participants and perhaps a few others who profit indirectly. The benefits of derivatives, however, extend far beyond the market participants. Derivatives help financial markets become more efficient and provide better opportunities for managing risk.38

After warning the student not to succumb to “the temptation to speculate when one should be hedging,” pointing to the “many individuals [who] have led their firms down the path of danger and destruction” as a result of “excessive confidence in one’s ability to forecast,” the text concludes with the reassuring words:

Fortunately, derivatives are normally used by knowledgeable persons in situations where they serve an appropriate purpose. We hear far too little about the firms and investors who saved money, avoided losses, and restructured their risks successfully.

To reinforce the lesson, students are asked to answer test questions:

Why is speculation controversial? How does it differ from gambling? What are the three ways in which derivatives can be misused?

Assume that you have an opportunity to visit a civilization in outer space. Its society is at roughly the same stage of development as U.S. society is now. Its economic system is virtually identical to that of the United States, but derivative trading is illegal. Compare and contrast this economy with the U.S. economy.

Storm clouds were already gathering over the mortgage markets in 2007, but publishing, with its built-in time lag, remained cheerful about quant prospects. In a book of accounts of personal success published under the alluring title How I Became a Quant, Neil Chriss, whom we already met in chapter 3, gave his view of how the profession became an option for mathematicians:

In the early 1990s, most of the people I know who went into finance started off going to graduate school making an earnest attempt to become academics. The ones who move to finance did so either because they discovered finance and found it an exciting alternative or because they discovered academia was not for them.

What I remember from that time is that even the most earnest new PhDs were having trouble becoming academics, in part because support for Russian mathematics evaporated when the USSR collapsed and the spectacular Russian mathematical school was emigrating en masse and taking many of the available jobs. The joke at the time was that those who failed to find university jobs could console themselves with starting salaries in finance significantly higher than those of their thesis advisers. Chriss goes on to describe how things had changed:

First, because of the rise in popularity of mathematical finance programs… many would-be math and physics PhDs are getting masters degrees in financial mathematics and going directly to finance. Second, many PhDs and academics looking to leave academia are going directly into quantitative portfolio management and not quantitative research…. It’s a change in perspective from “I want to do research for the firm” to “I want to trade and make money for the firm.”

I think that this change in perspective … is extremely good for financial markets.39

Cathy O’Neil, a mathematician who had recently left academia, published a first-hand account that same year in the AMS Notices. Offering guidance to those considering following in her path, she enumerated a few of the attractions of finance:

Finance is a huge and rapidly growing, sexy new field which combines the newest technology with the invention of mathematics to deal with ever more abundant data … finance has provided me with the opportunity to come up with good, new ideas that will be put into effect, be profitable, and for which I will be directly rewarded.

And its professional virtues:

For me and for many of my colleagues it is intrinsically satisfying to be in a collaborative atmosphere as part of a functional, productive, and hard-working team with clear goals.

She did not minimize the ethical challenges of being a quant, which she conceived in purely personal terms, without reference to “the path of danger and destruction” for the political process or the global economy:

Many mathematicians who talk to me about moving to finance are genuinely worried about the potentially corruptive power of money…. I think one can resist being corrupted by money by keeping a perspective and maintaining personal boundaries.40

O’Neil began to have doubts when the whirlwind hit:

Three months into her job, the stock market dipped, a hedge fund failed, and her firm lost a ton of money. She started to question many of the assumptions underpinning her work.41

Readers of the earlier texts had no inkling that those who followed the path would soon be accused of unspeakable crimes and much worse. “People assume that if they use higher mathematics and computer models they’re doing the Lord’s work.” (These are the words of Warren Buffett’s “longtime partner, the cerebral Charlie Munger,” quoted in The Quants.) He continues: “They’re usually doing the devil’s work”42 … THERE HE IS AGAIN!!! Readers who think I’m overworking the Faust motif should check out post-crash quant allegories—for example, this outline history sketched by a French colleague: faced with an “alarming” drop in enrollments, French mathematicians “implicitly” accepted a “Faustian pact: international finance would save our … departments from closure and in exchange we would offer the lion’s share of our best brains.” Or consider this quant, anonymously quoted in a 2009 New York Times article, speaking of “a thousand physicists on Wall Street”—physicists are implicated as deeply as mathematicians—who “talk nostalgically about science”:

“They sold their souls to the devil,” she said, adding, “I haven’t met many quants who said they were in finance because they were in love with finance.” “They [i.e., quants] get paid, a Faustian bargain everybody makes,” [added former trader] Satyajit Das.43

David Steinsaltz managed to review Patterson’s book for the AMS Notices without once invoking the devil’s name. He did say, with circumspection, just where mathematicians needed to acknowledge responsibility:

Economic historians teach us that one indispensable ingredient in a financial crisis is an excuse for ignoring the lessons of the past, … for believing that ‘this time is different.’ The most recent round of excuses was provided, if not directly by mathematicians, then under the banner of mathematics, and the crisis that ensued was of terrifying proportions.

To summarize moralistically: before the crash, How I Became a Quant was published in New York and the AMS Notices ran O’Neil’s article on the Transition from Academia to Finance; after the crash, The Quants was published in New York (as were many other titles in the same vein), and its AMS Notices review was the occasion for a scathing denunciation of a culture of finance that flourished “under the banner of mathematics.” Cathy O’Neil, meanwhile, was identified in a 2011 Mother Jones profile as organizer of “a branch of Occupy Wall Street known as the Alternative Banking Group.” Here’s what she wrote on her mathbabe blog on New Year’s Day 2013:

It’s our ideas that threaten, not our violence. We ignore the rules, when they oppress and when they make no sense and when they serve to entrench an already entrenched elite. And ignoring rules is sometimes more threatening than breaking them.

Is mathbabe a terrorist? Is the Alternative Banking group a threat to national security because we discuss breaking up the big banks without worrying about pissing off major campaign contributors?

I hope we are a threat, but not to national security, and not by bombs or guns, but by making logical and moral sense and consistently challenging a rigged system.

$ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥

[A] science is said to be useful if its development tends to accentuate the existing inequalities in the distribution of wealth, or more directly promotes the destruction of human life.*

Writing before the crash, Cliff Asness, one of Patterson’s protagonists, had attributed his decision to leave Goldman Sachs ten years earlier (in part) to “simple ambition and greed,” adding “[A]nyone who starts a hedge fund and doesn’t admit this motivation probably shouldn’t be trusted with your money.”44 It’s fascinating to unpackage this aside, starting with the “you” to whom it is addressed: if “you” are an individual who wants to hedge in the United States, “you” had better be a High-net-worth Individual (HNWI)—“your” net worth should exceed

one million dollars, enough, one hopes, to have given you a feeling for “simple ambition and greed.”45

Gordon Gekko’s “Greed is good” is an explicitly post-Aristotelian ethical stance. Greed, in the Nicomachean Ethics, is called pleonexia and is the vice responsible for injustice. Jesus, in Luke 12:13–21, also had harsh words for pleonexia. But Jesus and Aristotle didn’t know about Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand. Ayn Rand, founder of “Objectivism,” whose acolyte Alan Greenspan helped usher in the age of Gekko, would have explained to them that

[s]ince time immemorial and pre-industrial, “greed” has been the accusation hurled at the rich by the concrete-bound illiterates who were unable to conceive of the source of wealth or of the motivation of those who produce it.46

Were it not for greed, the argument goes, no one with access to capital would risk losing it on an uncertain investment, and there would be no growth; so the greedy are the motors of general prosperity. Hand in hand with Greenspan and Rand, the Hand has been working flextime, by day apportioning goods, capital, labor, and raw material where they are most needed in gentle equilibrium, by night rewriting Aristotle to retool the vice of pleonexia as the virtue of megaloprepeia, variously translated “magnificence” or “munificence.” Aristotle writes, “The magnificent man is like an artist [epistemon] in expenditure: he can discern what is suitable, and spend great sums with good taste.”47 For an Objectivist, investing to make oneself even richer is already a sign of taste, a work of art in the medium of wealth creation.

It’s often pointed out that the historic Adam Smith was not at all sympathetic to Gekko’s ethics. The Invisible Hand was first spotted in his Theory of Moral Sentiments dealing a version of the egalitarian Stable Equilibrium game of figure 4.2, making “nearly the same distribution of the necessaries of life, which would have been made, had the earth been divided into equal portions among all its inhabitants, and thus without intending it, without knowing it, advance the interest of the society.” Smith’s opening sentence is cited in a recent effort to prove that we are “a cooperative species”:

How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it, except the pleasure of seeing it.48

Studies of cooperative behavior may or may not be consistent with Objectivism. One study found most experimental subjects “generally cooperative or public spirited,” with the notable exception of “a group of first-year graduate economics students: the latter were less cooperative, contributed much less to the group, and found the concept of fairness alien … ‘Learning economics, it seems, may make people more selfish’ … [other experiments found that] students of economics, unlike others, tended to act according to the model of rational self-interest to which they are exposed in economics.” The conclusions: “exposure to the [economists’] self-interest model does in fact encourage self-interested behavior” and “differences in cooperativeness are caused in part by training in economics.”49

“When you find an innately hedged environment,” said a character in Neal Stephenson’s Cryptonomicon—a novel, one of whose premises is that number theory can make you rich—“you lunge into it like a rabid ferret going into a pipe full of raw meat.”50 This looks like an allusion to Eugene Fama’s Nobel Prize–winning Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), in the vivid imagery of Robert C. Higgins: “The arrival of new information to a competitive market can be likened to the arrival of a lamb chop to a school of flesh-eating piranha…. Very soon the meat is gone, leaving only the worthless bone behind….” Modern market theory has transmuted the Invisible Hand to efficient rows of Visible Teeth. EMH was celebrated as long as the party lasted—the quants in Patterson’s book saw themselves as piranhas rewarding themselves for keeping markets efficient—and widely criticized when it ended, some going so far as to blame EMH for “chronic underestimation of the dangers of asset bubbles breaking” that made the crash so severe.51 I wouldn’t presume to judge how well EMH or any other academic hypothesis fares as a model of “objective” economic reality. As a mathematician I can point out, however, that the information-devouring ferrets and piranhas restoring the market to equilibrium are in exactly the same line of work as the impersonal forces in the deterministic difference equations of figures 4.2 and 4.3.

The syllabi and textbooks don’t need to remind students that a good way for a quant to become an HNWI is to manage the fortunes of HNWI clients.52 For Cliff Asness, the “mandate” of the Quantitative Research Group he created in 1994 at Goldman Sachs came down to this: “let’s see if we can use these academic findings to make clients money.”53 I have seen the “best quantitative financial minds” of a generation drinking designer cocktails in theme bars in the Lower East Side neighborhood where my father’s parents met 100 years ago54 and saying things like

[w]e look for places where the math is right … [where] you get the kind of exponential growth that should get us all into fuck-you money before we turn forty.55

My colleagues around the world refrained from showcasing Asness’s “mandate” in the 1990s when, one after another, they welcomed financial mathematics programs into their departments, but it would have been a salutary challenge to the conventions of academic decorum to adopt something along the same lines as the new track’s motto: “let’s see if we can teach our graduate students to use what they learn here to make clients fuck-you money!”

$ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥ $ € £ ¥

Practically anyone can strive to perfect most of the Aristotelian virtues, like courage [andreia], truthfulness [alētheia], liberality/generosity [eleutheriotēs], and wittiness [eutrapelos], but “only the affluent and those of high status can achieve certain key virtues,”56 notably megaloprepeia, which is generosity on an order conceivable only to the richest 1% or 0.01%, or as we would say now, HNWI or UHNWI. “There is no virtue more suitable to a great man than liberality and magnificence,” wrote Sigismondo Sigismondi, “but magnificence is the greater of the two, because liberality can also be exercised by a poor man.”57 Marcus Licinius Crassus, who crushed the Spartacus rebellion, was definitely one of the late Roman Republic’s UHNWIs. Although Plutarch writes that as consul, he “made a great sacrifice to Hercules, and feasted the people at ten thousand tables, and measured them out corn for three months,” Plutarch saw Crassus as a model of pleonexia rather than megaloprepeia.58 In our time megaloprepeia has been transmuted into the cardinal capitalist virtue, the prerogative of the investor, the entrepreneur, the job creator, the HNWI to whose creative destruction TINA.

Magnificent display is still associated with megaloprepeia, which was already a motor of the arts when Lorenzo the Magnificent reigned in Florence.59 It’s no less true today. Muntadas’ interviews with art world movers give collectors a special prominence. For gallery owner Daniel Templon, “There’s no other way to evaluate a work of art than to put a price tag on it. And that’s how it’s been ever since art has existed.” Artist Hans Haacke, in contrast, stresses the calculations of corporate collectors: they “got involved in the arts because the arts were something with which they could polish their image, and through the arts, they became more forceful in their lobbying for interests very close to the bottom line.”

Some individual collectors allude to speculation (“that is a different type of collector”) but insist on their own spiritual link to the art and the artist. “My motivations,” writes one, “have very much to do with my own spirit and my own soul,” just like “the clothes you buy, the shoes you wear, the furniture you buy … the woman you love…. You love it or you don’t. And after you have loved it and you want it, you want to live with it.60

MacIntyre reminds us that “no practices can survive for any length of time unsustained by institutions….” which are “characteristically and necessarily concerned with” what MacIntyre calls “external goods” like “money, power and status.” These are contrasted with what MacIntyre identifies as the “internal goods,” the virtues on which a tradition-based practice is founded. “[C]haracteristically,” MacIntyre’s external goods “are such that the more someone has of them, the less there is for other people.”61 This is not the case for internal goods. Muntadas’s interviews point to the ambivalent relations between external and internal goods:

If you become successful in terms of the economic system that art is part of, you become automatically bound up with the value systems … of those who have the money to have leisure time and to purchase artwork. That’s a problem for a lot of us, because we don’t all share the values of those who have the power.62

The collector seems to have no mathematical counterpart in chapter 3’s table of parallels with the arts. Our practice’s relations of ambivalence are mainly with governments and university administrations. But times are changing. James Simons was one of the world’s most respected pure mathematicians, winner of the prestigious AMS Veblen Prize in geometry, before he became the man Patterson calls “the reclusive, highly secretive billionaire manager of Renaissance Technologies, the most successful hedge fund in history.” “I went into the investing business without any thought of applying mathematics at all,” explains Simons. “I had some ideas and they worked out well.” Ferguson devotes a page to his version of how Simons obtained “extraordinary returns by using powerful computers and proprietary trading algorithms to exploit tiny market trends invisible to humans, and which often last only a fraction of a second, … Normal investors who don’t own gigantic computer systems end up paying slightly more for stock trades and have slightly lower investment returns, while Simons and his imitators pile up micro-pennies by the billions.”

Ferguson concludes that such high-frequency trading has “no social benefit at all … no economic utility.” Simons disagrees:

[A]s the markets have become electronic and computers have been applied to generating prices and accepting trades and all the rest, the markets have grown tremendously more liquid. Spreads have come down…. So, is [high-frequency trading] socially useful? Well, if you think highly liquid markets are socially useful then I think so.63

Hedge funds, remember, are exclusively for HNWIs, and I leave it to them to debate the utility of “highly liquid markets” in a world of ferrets and piranhas; as this chapter’s title suggests, I’m still waiting for someone to convince me of the social utility of HNWIs. But Simons has devoted much of his personal fortune to supporting research in mathematics as well as physics and biology. The Simons Foundation sponsors fellowships and conferences and has made substantial donations to scientific institutions on every continent, including tens of millions of dollars to the IAS alone; the dining hall there now bears his name, as does the Simons Center for Systems Biology. Berkeley’s MSRI has a Simons Auditorium and the IHES outside Paris has a Marilyn and James Simons Conference Center; there is a Simons Center for Geometry and Physics on Long Island and a Simons Institute for the Theory of Computing in Berkeley. As one country after another has entered into crisis, as universities lose positions and libraries see their subscription budgets cut, I’ve lost track of the number of times colleagues looked for salvation to the “white-bearded wizard”: think Gandalf, not Mephisto.64

When the trader Satyajit Das disclosed to the New York Times that financial mathematics devises models for “[m]aking money” and that “[t]hat’s not what science is about,”65 he was saying that the work of quants does not conform to the internal goods, in MacIntyre’s sense, of the practice of science. But Simons is clearly as concerned as any mathematician, physicist, or biologist about the internal goods of their respective fields. His foundation bases its decisions on the advice of those within the fields who share these concerns. Other foundations—the Clay Mathematics Institute, the American Institute of Mathematics (AIM), and (on a much smaller scale) the charitable Fondations de l’Institut de France, are run along similar lines. And thus finance mathematics enters as part of a novel triangular trade, an exponentially virtuous circle: academic mathematics departments host finance mathematics programs that generate the UHNWI within financial institutions and they, in turn, provide the “external goods” necessary to maintain the practice of pure mathematics, a kind of perpetual megaloprepeia machine from which the Columbia math department even manages to extract a limitless cornucopia of fresh fruit.66

The philanthropy of Powerful Beings is not new in mathematics. Princes, counts, and kings financed prize competitions in mathematics starting in the eighteenth century. Mathematics was a state priority in Napoleonic France, and the German school grew to dominate nineteenth-century mathematics under the patronage of Prussian ministries.67 In a section entitled “the general mathematical market,” Mehrtens analyzes relations between science and industry in Germany at the turn of the twentieth century, focusing on Felix Klein’s work with the Göttinger Vereinigung.68 Even then, it was difficult to force mathematicians into the industrial mold. The ambiguities of mathematics were a handicap: “it was considerably harder to find funds” for mathematics than for chemistry with their “unequivocal and firmly established link to industry.” Natural scientists, unlike mathematicians, may have had closer personal relations to industrialists and bankers. Professionally speaking, Mehrtens thought, “mathematicians are neither economically nor technically especially interesting, nor are they particularly enterprising.” But funds could still be found for mathematics—“special encouragement of applied mathematics” and especially “prizes for outstanding work.” The IHP building in Paris was built in 1928, in large part with Rockefeller and Rothschild money.

National governments now provide the lion’s share of funding for mathematical research, even at private universities in the United States. Cutbacks to research budgets under current conditions of austerity are a source of anxiety, but no one complains about the ups and downs of private philanthropy—it’s “their” money, after all, and we are fortunate to be seeing any of it. The deeper irony is that the (ostensibly) democratically based social institutions of government are perceived as less sympathetic to the “internal goods” of mathematical practice than the structures of megaloprepeia endowed by Powerful Beings like Clay, AIM, or Simons. Whatever can be said about the sources of their generosity, the immediate effects of this kind of philanthropy on mathematics have been uniformly positive. Mathematicians fill the seats on foundations’ advisory boards and operate these structures as relaxed fields; in practice, their scientific decisions are answerable to mathematicians alone, within the budget the benefactors provide. There is no set format for proposals, but they should be short—one page for a Clay workshop, two to three pages for AIM—and the foundations are not expecting to hear about potentially useful applications. This is usually presented as a narrative about the generosity of certain Powerful Beings; but it could also be seen as a commentary on the state of democracy that is no less depressing for its homology to what has long been taken for granted in the art world.69

“RESPONSIBILITY SEEMS TO DISSOLVE”

[L]ike all the phenomena of our societies, the current financial crisis is only seen as a technical problem…. We reason solely in mechanical terms, as if living individuals were elementary particles subject to laws … conceived on the model of Galilean physics.70

In his lecture at the 2010 International Congress of Mathematicians in Hyderabad, Ole Skovsmose, a specialist in mathematics education, analyzed how the “symbolic power” of mathematics is exercised through “the grammatical format of a mechanical and formal world view.” Skovsmose puts his finger on the ethical danger: “Through mathematics in action, we are in fact bringing our social, political, and economic environment deeper into a mechanical format…. mathematics-based actions often appear to be missing an acting subject … to be conducted in an ethical vacuum.” Aspects of the ongoing crisis can be related to “mathematics-based avalanches of decisions” in financial markets and elsewhere. “But who could be held responsible? Somehow responsibility seems to dissolve.”71

In addition to our technical qualifications, mathematicians bring to finance a scorn for mere empiricism that under appropriate conditions can blossom into full-scale denial; as Diogenes the Cynic is said to have marveled that “mathematicians should gaze at the sun and the moon, but overlook matters close at hand.” Whether or not the data corroborate mathematical models, mathematics has the merit for decision makers of being perceived as “incorrigible”—“it provides the kind of truth with which there is no possible argument.”72 Economics is only the most politically influential of the fields that call upon mathematics to adjudicate potential conflict between alternative realisms: in this case, the TINA realism of the market and the ethical realism that provides the basis for democracy as an expression of human values.

By playing the role of provider of the appearance of scientific objectivity, mathematics indentures itself in turn to the model of scientificity that underpins the philosophy of Mathematics. Our truth flows outward, clutching its warrant of incorrigibility, into the larger society, where it is deployed by Powerful Beings in what is demonstrably the only way possible. As far as finance is concerned, Steinsaltz calls this process “legitimacy exchange” in his review of The Quants for the Notices of the AMS:

University mathematicians have served the finance industry with a steady stream of students trained … to accept models axiomatically, without skepticism. At least as important, we have participated in what G. Bowker … has termed “legitimacy exchange” (though with a view to the huge blow suffered by the reputations of both groups, perhaps it might be called a “credibility default swap”)…. In return for lending the reputation of their subject, academic mathematicians are compensated by sharing the financiers’ reputation as important people doing important work, and the enviable status as a conduit to high-paying careers.”73

“The observable economic facts,” thought Albert Einstein, correspond to “what Thorstein Veblen called ‘the predatory phase’ of human development.” Einstein saw socialism as a way “to overcome and advance beyond the predatory phase.”74 To believe TINA—There Is No Advancement—is to deny any positive role for ethics in politics; to believe TINA on the grounds that it can be proved mathematically is to hold mathematics responsible for the “ethical vacuum” of contemporary politics. A few more years of this and an Exterminating Angel will surely arise to cast out the Fiend. Remember that in the final pages of Goethe’s Faust, heaven reneged on the bargain Mephistopheles contracted in the opening scenes. Will this be good for mathematics? Don’t count on it.

* G. H.Hardy in 1915, quoted with an apology in A Mathematician’s Apology.

How to Explain Number Theory at a Dinner Party

SECOND SESSION: EQUATIONS

Everyone who attends high school learns to solve simple algebraic equations. A linear equation with a single variable x has exactly one solution;1 for example,

has the unique solution x = 2, by which we mean that (a) 3 × 2 + 1 = 7 and (b) if you put any other number in the place of 2, the two sides will no longer be equal.

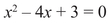

A quadratic equation can have two solutions, no solutions, or (more rarely) a single solution:

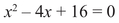

has the two solutions x = 3 and x = 1, whereas

has no solutions unless you allow imaginary numbers, such as  ; more about them later. But there are also cases like

; more about them later. But there are also cases like

whose solution,  , as we saw in the previous section, is an irrational number. (The distinct but no less valid negative solution,

, as we saw in the previous section, is an irrational number. (The distinct but no less valid negative solution,  , is irrational as well.)

, is irrational as well.)

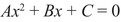

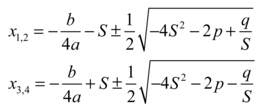

The quadratic formula taught in high school algebra solves the problem in all cases: if the equation is

with A a number different from 0, then the solutions are2

whose nature (rational, imaginary, or occasionally equal) can be determined by inspection: If D > 0, we don’t worry about taking its square root; if D = 0, the two roots are equal; and if D < 0, then its square root is imaginary (a paradoxical name if there ever was one, because the square root of D is the side of a square whose area is D, and who has ever imagined a square with negative area?) and the solutions are complex numbers.

Thus, if we are willing to allow square roots into our arithmetic, we can consider the quadratic equation a problem whose solution has been long understood (in some cases by the ancient Babylonians), though it might be argued that it was not until imaginary numbers were generally accepted that the preceding formula was established. Equations of degree 3 and 4, such as

were first solved in Renaissance Italy to great acclaim; the solutions are given by formulas involving cube roots and fourth roots.

Nils Henrik Abel and Evariste Galois both died tragically young in the early nineteenth century, contributing to the romantic image of mathematics still operative in certain quarters, after showing independently that there is no formula for the roots of general polynomial equations of degree 5 and up. Before he was killed in a duel at age twenty-one (see chapter 6), Galois did much more: he provided a method for understanding the roots even though they cannot be written down.

Galois’ work represents the starting point of modern algebraic number theory, which is probably the most accurate name for the kind of mathematics in which I specialize. In general, a polynomial equation of Nth degree in one unknown x has at most N solutions, or exactly N if some of them are counted more than once, as it is often useful to do. Galois theory does not provide a formula for these solutions but rather a way of looking at the solutions that is completely general and is more useful for answering most questions than a formula would be. In this sense the problem of equations in one unknown can be said to be completely settled, thanks to Galois theory, although many questions remain. Equations in more than one unknown are another matter. For example, in high school algebra one encounters linear equations in two variables, such as

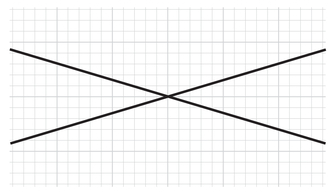

This equation has infinitely many solutions: for any number x, the equation provides a formula for y, and the choice of possible x is infinite. This is hardly surprising, because the solutions of the equation form a line in the coordinate plane, as shown in figure β.1, and the line is understood to have infinitely many points. The collection of rational solutions is just the set of pairs (x, 1/2x + 3) whenever x is rational.

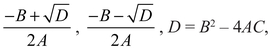

The coordinate plane represents pairs of numbers as points on the page (assumed infinite in all directions). To reach the point (x, y), one moves x units to the right and y units up (which means down if y is negative and to the left if x is negative), starting from the origin (0, 0), which is the point where the horizontal and vertical lines meet in figure β.1. The Pythagorean theorem then calculates the distance of the point with coordinate (x, y) to the origin (0, 0) as

Thus the solutions to the equation of degree 2,

are given by the points (x, y) at distance 1 from the origin (0, 0)—in other words, by the points on the circle of radius 1 around the origin. We can temporarily forget about the picture and look for solutions in whole numbers, but we quickly realize that there are only four, namely, (1, 0), (0, 1), (–1, 0), (0, −1)—the four cardinal points of the circle.

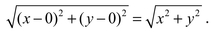

Solutions in rational numbers are more interesting.3 Write x and y as fractions with a common denominator:

where a, b, h are whole numbers, h ≠ 0. Then

is equivalent to

By the Pythagorean theorem, this is the equation for the lengths of the sides of a right triangle: the hypotenuse is h, and a and b are the two sides adjacent to the right angle.

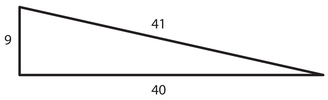

For example, a = 3, b = 4, h = 5 is a solution everyone has seen; so x = 3/5, y = 4/5 is a solution to the original problem. If your high school teacher was a bit more energetic, you will have seen a = 5, b = 12, h = 13 or even a = 9, b = 40, h = 41.

Figure β.2. A right triangle with integer sides.

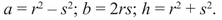

Thus x = 5/13, y = 12/13 is another solution using rational numbers. It turns out that there are infinitely many rational solutions of this kind, and there is even a formula for writing them all down. We start with two whole numbers r and s without common factors; then

We can also multiply all three terms by a common factor d:

Up to interchanging a and b, this gives all possible solutions in whole numbers, a fact proved in Book X of Euclid’s Elements in the third century BC and (in the preceding geometric interpretation) about five hundred years later by Diophantus of Alexandria. Anyone with sufficient patience can establish this result using elementary properties of even and odd numbers and the unique factorization of whole numbers as products of prime numbers, as mentioned in the previous session.

This problem is special because it is attached to two stories—the story of right triangles with integer sides, on the one hand, and the story of Diophantus’ formula for the solutions. One can consider equations of any degree in any number of variables. A theorem in logic4 tells us that there is no general way to find integer solutions or even to determine whether or not there are solutions. That is also a story—but not one with a happy ending. One suspects that a problem in the field of Diophantine equations—the problem of finding integer or (at least) rational solutions to equations with integer coefficients—is interesting to the extent that it forms part of a story. The story is naturally internal to mathematics but, like any story, is most interesting when the problem does not appeal only to specialists.

An equation like x2 + y2 = 1 or x2 − 3xy + 3y2 = 1 is called quadratic5 because the highest power of either variable is the second power and any monomial including both variables is a constant multiple of xy. Quadratic equations in two variables can be considered completely understood. There is the example x2 + y2 = 1 discussed earlier, but there is also the very similar example

This one has no solutions at all in which x and y are rational numbers or even real numbers. The square of a real number is positive, so for any real numbers x and y, the left-hand side of the equation is always at least 1 and, therefore, can never be equal to zero. This is analogous to the quadratic equations in one variable, discussed previously, with no roots that don’t involve imaginary numbers. It is to solve such equations that one introduces imaginary numbers. From the standpoint of imagination imaginary numbers pose special challenges:

We have never seen any curve or solid corresponding to my square root of minus one. The horrifying part of the situation is that there exist such curves or solids. Unseen by us they do exist, they must, inevitably; for in mathematics, as on a screen, strange, sharp shadows appear before us. One must remember that mathematics, like death, never makes mistakes. If we are unable to see those irrational curves or solids, it means only that they inevitably possess a whole immense world somewhere beneath the surface of our life (Ye. Zamyatin, We, Record 18).

… in that kind of calculation [involving imaginary numbers] you have very solid figures at the beginning, which can represent metres or weights or something similarly tangible, and which are at least real numbers. And there are real numbers at the end of the calculation as well. But they’re connected to one another by something that doesn’t exist. Isn’t that like a bridge consisting only of the first and last pillars, and yet you walk over it as securely as though it was all there? (R. Musil, The Confusions of Young Törless, trans. S. Whiteside, p. 82)

It takes a fictional character to restore all its pathos to the mystery of existence. As far as pure algebra is concerned, imaginary numbers are no more imaginary, and their existence no more problematic, than irrational numbers such as  .

.

Be that as it may, the quadratic equations in two variables fall into two classes: those with infinitely many rational solutions, like the Pythagorean equation, and those with no solutions at all. Given a quadratic equation in two variables, for example, there is a simple procedure for determining whether it has infinitely many or finitely many rational solutions.

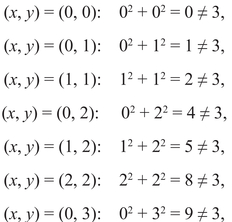

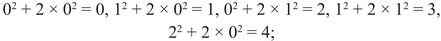

Look first for integer solutions, and start by testing small integers. It’s obvious that most of these won’t work because the left-hand side quickly becomes bigger than the right-hand side, but let’s carry out the calculation in the hope that this will help us with rational solutions.

We don’t need to check pairs like (x, y) = (1, 0) because x and y can be exchanged and the result on the left is the same. We notice that the sum is often an even number (0, 2, 4, 8, 10, not 6 and not 12 either). With more attention, one observes that the odd numbers that do occur have something in common:

The missing numbers on the list are

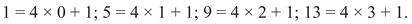

This suggests a pattern. Say a positive integer n is congruent to 1 modulo 4 if it is of the form n = 4k + 1, where k is a positive number; in other words, if n − 1 is evenly divisible by 4. Likewise, say n is congruent to 3 modulo 4 if it is of the form n = 4k + 3, in other words, if n − 3 is evenly divisible by 4. The terminology “congruent to” and “modulo” will be explained in chapter β.

Our calculations suggest the following hypothesis.

Two Square Theorem: An odd number that can be written as the sum of two squares must be congruent to 1 (and not to 3) modulo 4. An odd prime number can be written as the sum of two squares if and only if it is congruent to 1 modulo 4.

This hypothesis is correct and was proved by a number of mathematicians, notably by Gauss, and for that reason, it was promoted to the status of a theorem.6 With additional work one can show that this theorem implies that the equation x2 + y2 = 3 has no solution in rational numbers either.

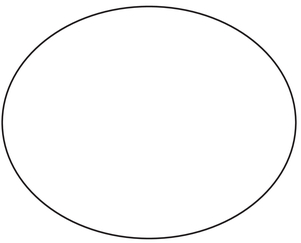

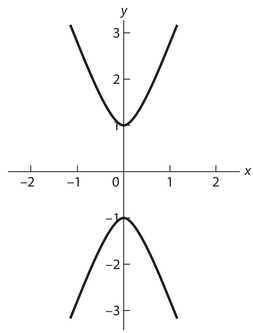

We have chosen for our example the equation for the circle with radius  , which (as we have already seen) is an irrational number; if the radius were rational, then Diophantus’ method would again give all the solutions. The two square theorem determines which circles with irrational radii have points with rational coordinates. This is the beginning of a long story. From the point of view of number theory, there is no essential difference between a circle and an ellipse, which you can think of geometrically as the collection of points in the plane, the sum of whose distances between two fixed points, the foci, is a constant. For example, the quadratic equation

, which (as we have already seen) is an irrational number; if the radius were rational, then Diophantus’ method would again give all the solutions. The two square theorem determines which circles with irrational radii have points with rational coordinates. This is the beginning of a long story. From the point of view of number theory, there is no essential difference between a circle and an ellipse, which you can think of geometrically as the collection of points in the plane, the sum of whose distances between two fixed points, the foci, is a constant. For example, the quadratic equation

is the equation of the ellipse with total distance  from the two foci

from the two foci  and

and

Figure β.3. The ellipse x2 + 2y2 = 5.

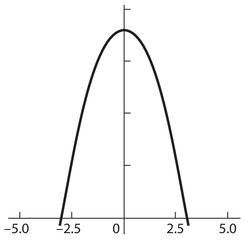

The quadratic equation

Figure β.4. The ellipse x2 + xy + y2 = 11.

is the equation of a tilted ellipse, with foci at  and

and

. Neither of these equations has any rational solutions. On the other hand, each of the equations x2 + 2y2 = 3 and x2 + xy + y2 = 7 has an integer solution—(x, y) = (1, 1) in the first case and (x, y) = (1, 2) in the second case—and, therefore, the general theory implies it has infinitely many rational solutions.

. Neither of these equations has any rational solutions. On the other hand, each of the equations x2 + 2y2 = 3 and x2 + xy + y2 = 7 has an integer solution—(x, y) = (1, 1) in the first case and (x, y) = (1, 2) in the second case—and, therefore, the general theory implies it has infinitely many rational solutions.

It’s easy to write down a complete list of rational solutions, using a procedure similar to the one invented by Diophantus to find Pythagorean right triangles. But it is even easier to write down a complete list of integer solutions, because squares of integers are positive, and after you have gone through the first few options, the sums on the left get bigger than the target on the right. For example,

after that, the sum x2 + 2y2 is bigger than 3. So (1, 1) is the only solution. One checks similarly that x2 + xy + y2 = 7 has exactly two integer solutions: (x, y) = (1, 2) and (x, y) = (2, 1).

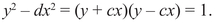

On the other hand, if you look at quadratic equations involving differences rather than sums of squares, you can’t use this kind of argument to terminate the search for solutions. In fact, an equation like

has infinitely many solutions with x and y both integers. The word like has to be understood appropriately. The general equation of the form y2 − dx2 = 1, where d is a fixed integer, is called Pell’s equation,7 and it has been known since the eighteenth century that it has infinitely many integer solutions provided d is not a square. If by mistake you choose d = c2, with c an integer, then you can write

But then both y + cx and y − cx are integers, both of which divide 1, and the list of integers dividing 1 is very short. For example, the only solution to y2 − x2 = 1 in nonnegative integers is given by x = 0, y = 1.

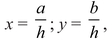

But when d is not a square, there is a method for finding all the solutions. I will not describe this method,8 but instead I will explain how from one solution you can derive infinitely many new solutions. The smallest solution to y2 − 7x2 = 1 is given by x = 3, y = 8. Take the number  and multiply it by itself: you get

and multiply it by itself: you get

and you can check that y = 127, x = 48 is also a solution to y2 − 7x2 = 1. Multiply by  again:

again:

and 20242 − 7 × 7652 = 1.

Figure β.5. The hyperbola y2 − 7x2 = 1.