FIT | 5

DRAPING THE TIGHT SHIRT

WHAT ARE TIGHT SHIRTS?

In this chapter, we explore how to use the drape-to-fit process to create custom-fitted shirt patterns for shirts with these features:

• Extreme shaping at side and body seams

• Darts—visible and invisible

• Fitted shoulders

• Optimized, but possible limited freedom of movement in the arms and shoulders

• Minimum body ease, garment follows the shape of the body, possible strain wrinkles

Tight shirts follow the shape of the body everywhere. As with the fitted shirt, the easiest path to greater ease reduction, so that the shirt becomes “tight,” is simply to continue pinning ease away from a fitted drape until the muslin is as tight fitting as desired. As before, there are options and variations involved in the drape-to-fit process, including adding body seams, such as “princess” seams. We’ll examine these options in the following pages, as I demonstrate how to drape a tightly-fitted shirt. And remember, once you have the perfectly draped muslin, to create the paper pattern, download the pdf, “Converting a muslin drape to a paper pattern” at www.quartoknows.com/page/sewing-shirts.

It’s possible you can make a tight-fitting shirt by scaling down an already customized fitted shirt, like the “grading” process used by manufacturers. This means that ease is reduced for every part of the shirt equally, so you would have to take care not to make the sleeves too short (or too tight) or move the neckline too close to the neck.

The most direct path to a customized, tight-fitting shirt might be to start completely from scratch with a customized upper-body drape that makes no effort to be a shirt, but instead create a “ruthless record” of whatever shaping is needed to mimic the upper body so closely as to still be wearable and to allow for movement, but no looser. Then, you could simply add a few classic shirt details to the drape. On the next few pages, I demonstrate how to drape-to-fit a tight-fitting shirt, starting with the fitted drape. Then, I’ll share a quick way to drape a tight-fitting body pattern from scratch. (This method also creates a highly accurate custom dress-form cover, ready to pad out to duplicate your identical body shape).

DRAPING A TIGHT-FITTING SHIRT FROM A FITTED TEST MUSLIN

This demonstration begins with the fitted muslin that we last used in the beginning of chapter 4 (on form #4, male with athletic build). In that process, to create a fitted shirt, I repositioned the side seams by pinning out ease in the back, at the location where the extra ease appeared (instead of at the side seams), and traced the still-pinned muslin drape (see here) to make a new muslin. Back on the form here, with the side seams basted and armholes trimmed, the shirt muslin looks snug, but there’s still plenty of ease to remove from the back and waist, as you can see at the hem (A). Here, you can also see a strain wrinkle from chest to side seam. For a fitted shirt, simply releasing the seam near the end of that wrinkle (in other words, allowing extra length) will fix this on this form (B). But for a tight fit, that solution won’t work because it increases the ease at the release area (C). Since I’ve already taken out about as much ease as the pin-out-and-retrace method can manage, I’ll now have to continue with some combination of direct side-seam repinning and dart shaping, both better suited to the more exacting shaping and ease reduction needed here.

Note: If you are wondering about the black tube-like appendages occasionally seen protruding from the form’s arms—these are the part of my home-made form that makes the arms flexible.

The images on this spread document various draped attempts to find the least wrinkled combination of side seam repinning and pinned-out dart shaping in the shirt back as I take the fitted muslin from the previous page into tight territory. They offer another example of how to use draping to manage subtle adjustments that you would never be able to zero in on with flat-pattern adjustments, and how the process itself is one of trial and retrial. I don’t say “…and error,” as judgement and personal preference are always the deciding factors, not “correctness.”

The first image with the sides returned to their lowered position shows the muslin as we finished with it on the previous page (A).

Note the width and angle of the brown vertical stripe in each subsequent image as I reposition the same folded edge of the blue gingham over the back piece, taking in or letting out ease, with or without back-dart pinning, always looking for the smoothest results in the body and the straightest, most parallel grain lines I can manage at the side seams. Of course, the solutions I’m finding are entirely dependent on the shape of the form, so it is important to remember that different body shapes will require different pinning and repinning.

Images (B) and (C) show my finished test drape and the side seams I settled on. I left a little diagonal strain from the chest on each side and moderate looseness in the center back, deciding that, in this case, I preferred this to perfect smoothness. The next step is to take the muslin off the form and trace it for what I expect will be the final muslin.

Here’s the new version of the earlier drape from the previous page, with the back pinning converted to symmetrical seams rather than darts, although darts would have been equally effective, but not as suitable or as attractive for the specific project I have in mind (see project 4). I also created a center front opening for the front of this drape. No doubt I should just own up to basically disliking darts on shirts, in general, and accept this as mere prejudice. I have no intention of trying to infect others with dart dislike; please go ahead and use darts if you like them! And, rejoice with me in recognizing how personal taste is an essential aspect of your designer’s vision.

I cut the new muslin fronts with an overlapping opening because project 4, which is made from this tight-fitting drape, has a center front opening and because I thought I might need asymmetrical adjustments to the front pieces. Notice that in the upper-right chest area, I’ve pinned away a little ease at the exact location where the excess fabric appears (only on the right side) and redrew the armhole (A). I traced the pinned right front drape (B). To test the new fronts, I made another test muslin; see how much better the armhole fits now (C). When creating the final front patterns, it will be important to mark right front and left front, since they are different, as they are on almost all draped patterns.

CONVERTING DART SHAPING TO SEAMS FOR A TIGHT-FITTING SHIRT

As we’ve seen, the closer we bring basic shirt shapes in towards the body, the more likely we are to create excess dart folding, in all the expected places, front and back, at the bust, shoulders, shoulder blades, and the waist and hips below the chest.

A very helpful and commonly used shirt-design tactic is to convert these folding excesses of fabric into seams rather than darts as I did on the previous pages. This is the same thing we automatically did when the yoke and back seam line curved near the armholes; that excess fabric could have been turned into shoulder darts, but we were able to transfer the excess fabric into the back/yoke seam and thereby cause it to disappear (see here).

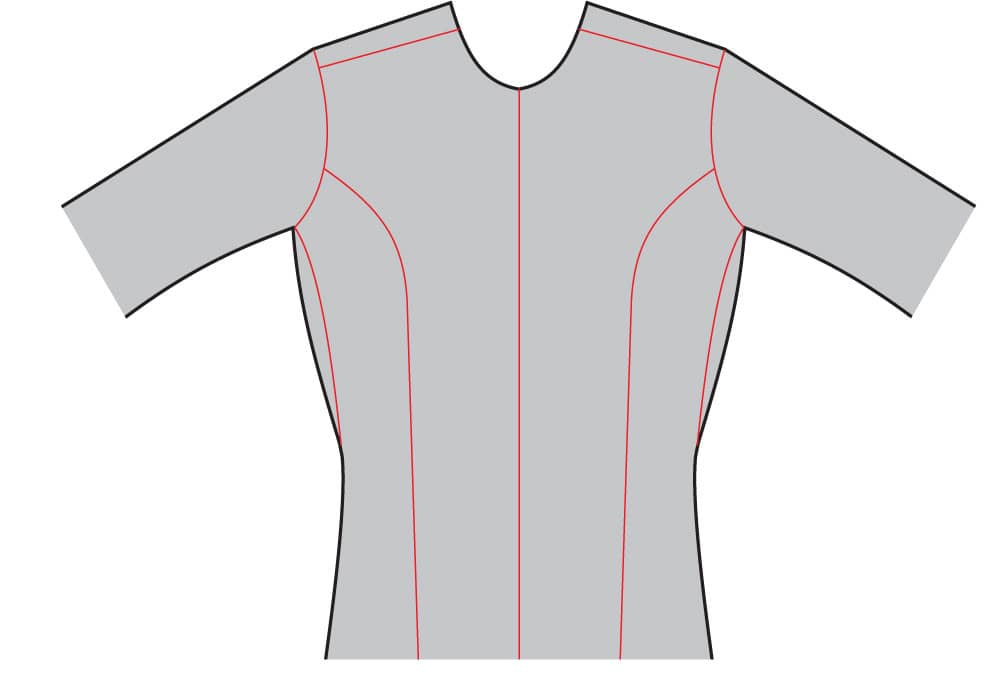

Additional seaming through the area where the darts end, and where the dart fullness can be pivoted, results in princess seams. The princess seam is a useful way to eliminate excess ease for both men and women who want a little more structure than a dart would provide on a sculpted garment.

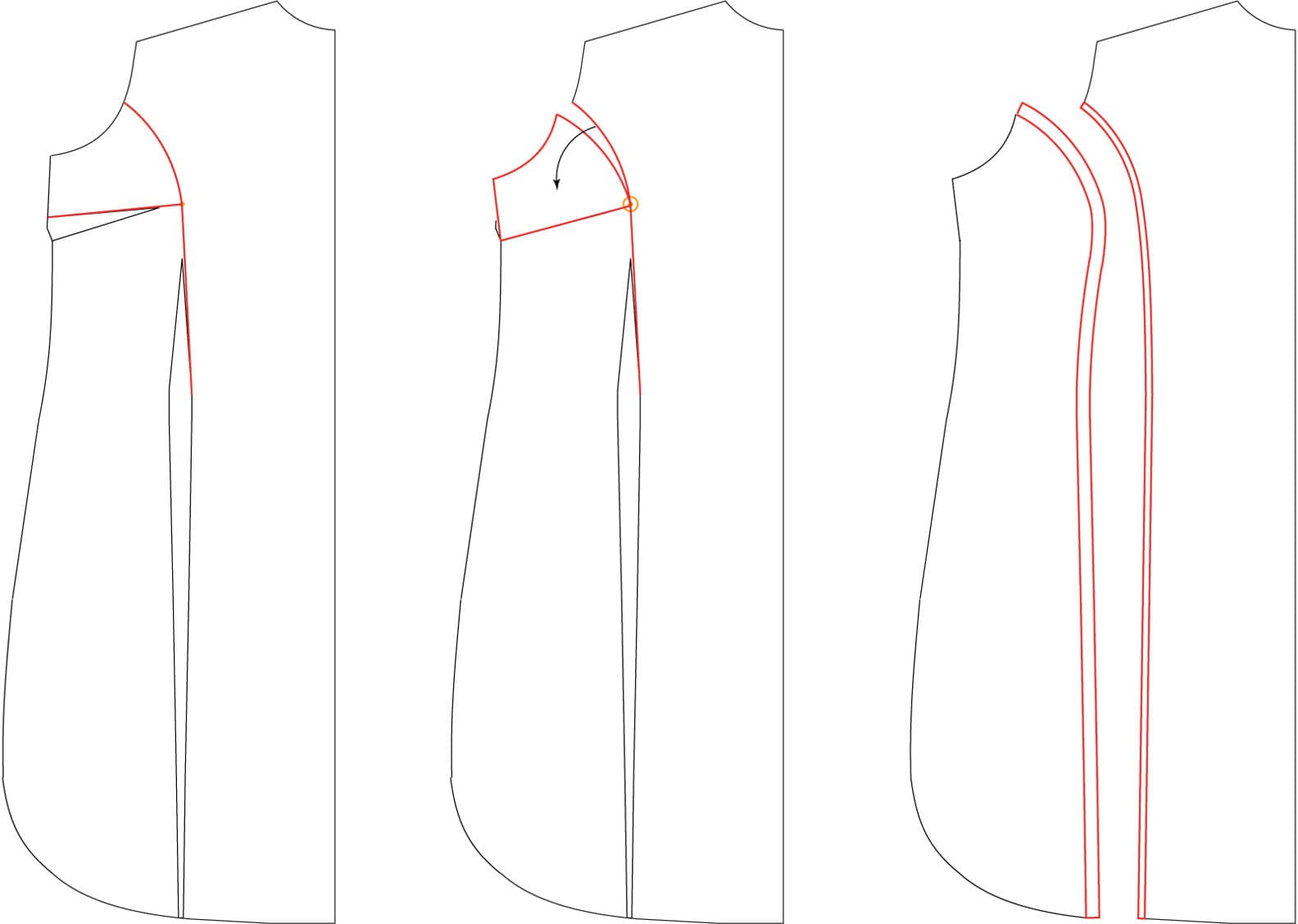

The series of diagrams, below, shows how to convert a bust dart and a lower dart into a seam from hem to armhole; this can be done in the garment front and by the same method in the garment back. Remember though, from chapter 4, shown here, you can pivot, the upper front dart anywhere around the bust point and still blend it into the below-bust dart, or you can pivot the below-bust dart elsewhere, but it is usually left where it appears in the diagram. This is typical flat pattern-making dart manipulation (for more information, see the downloadable pdf for “Dart manipulation”).

You can sew a standard seam here, but to form the seam and clean finish it at the same time, it is a good idea to use a two-pass flat-felled seam. These seams can be tricky to sew on tight curves. Take note of the final illustration, which shows how a flat-felled seam requires uneven seam allowances, and on which side to put the wider one for typical results. Flat-felled seams are described in detail in the downloadable pdf, “Flat-felled seam.”

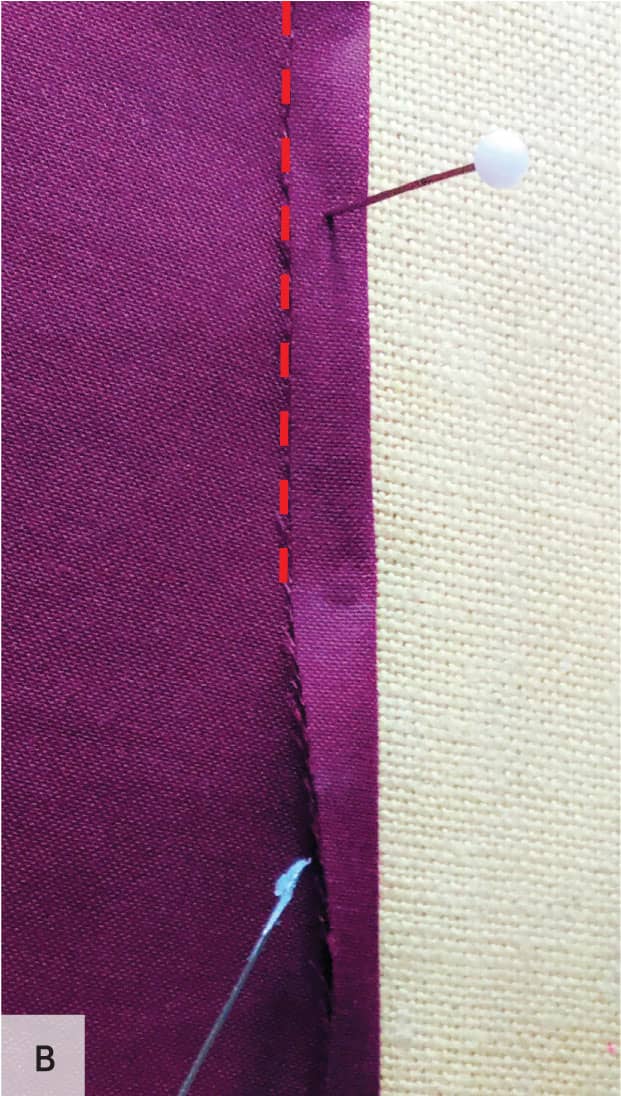

To align shaped seams that are curving in opposite directions when layered for stitching, it can be very helpful to pin them onto a padded surface both as they’re brought into alignment and as you prefold the wider allowance over the narrower one (A). Tiny dabs of glue stick on the point of a pin, as shown at top right, perfectly secure the arrangement and folds when the pins are removed for stitching (B).

Such curves are, with some fabrics, easier to handle with a felling foot (C), but even if this proves challenging and multiple pins are needed, a felling foot of the right width can still be the perfect tool for edge-guiding both the first and second pass the seam requires, as indicated by the dashed lines. Note that the point at which any curve must align with the foot is directly opposite the needle, here, it’s offset to the left to create the required width, not at the front of the foot, which sometimes needs to ride over the edge as it does here (circled), for the edge to be perfectly placed when it gets to the needle.

FOIL WRAPPING FOR BODY CLONING

Here’s that promised alternative technique for developing a “ruthless record” of any body shape, from the neck down, torso or full length! (I’ve made several torso forms, through to the hips, but that’s all I’ve tried, so far!) This body-cloning technique is not specific to making shirts, and it could certainly be useful in pattern-making for very tight-fitting garments, since it results in a complete pattern collection for making a skin-tight, body-molded fabric garment.

The idea is, to first wrap the “victim” or “volunteer” as snuggly as possible in foil, holding the loose pieces in place with light taping as you mold the layers. Then you secure the molded layers with wider and stronger clear tape, applied liberally so there are no loose foil edges. You’ll also see I’ve molded the foil over onto the arms a little so I can draw in an armhole, but I’ve yet to find these armlet pieces useful after cutting them off to define a clear armhole, and I eventually toss them, perhaps prematurely.

Use a marker to indicate basic pattern lines, but you don’t want the marker to poke through the foil, so make sure the tape completely covers any areas to be marked. Some people use plastic wrap instead of foil, but I find foil much lighter, cooler, and less suffocating, as well as easier to mold without overcompressing, and faster, too.

Once wrapped and taped, the next step is to mark cutting lines on the body clone. The marks should be made just where you’d expect to find seams on a similarly tight garment or basic fitting shell; that is, at vertical centers, using a plum line to mark vertical center; directly across points of maximum protrusion as where princess seams would go; around the neck and arms where necklines and armholes would naturally fall; and along the shoulders. For shirt-making purposes, I suggest drawing in yoke seams, as I’ve done in these photos.

Once you’ve marked the foil clone, cut it off the body along the marked lines and then flatten the pieces for tracing, eliminating the less-dramatic three-dimensional curves. It’s relatively easy at any stage to change design lines; for instance, if you decide you don’t want armhole princess seams, simply tape the pieces back together and redraw the seam to go to the shoulder. Trace the foil pieces onto pattern paper, carefully marking alignment points across matching pieces, but don’t attempt to true any of the seamlines you’ve just so carefully captured; use them exactly as is. You’ll refine them during the next step.

With the patterns made from traced the foil pieces, I always cut muslin pieces to make a test drape. To make a wearable garment from a foil wrap, you’ll very likely need to add ease, not pin more out, especially below the arms. This is most easily done by pinning the muslin tests more loosely at the side seams if these are cut with extrawide allowances, but can also be done at any other seam, including the center front.

To make a form cover instead of a test muslin, baste the front, back, and yoke together, and then proceed to our usual ease-reduction pinching-out where needed (here it’s across the yoke and at the side bust, both sides), followed by more tracing to capture all the further reduced pieces. Then, of course, you will want make a new muslin test, shown at the bottom center and right.

For my purposes, I have only used these foil patterns to make form covers to slip over a smaller form and then pad out to make a perfect torso form, duplicating the exact body shape of the volunteer you wrapped. Or even better, use the test muslin as the shell, inside of which you build up the form itself, assuming you don’t already have a form it’ll fit over without distorting—which if you’ve got anything but picture-perfect posture is quite unlikely.

MAKING A FORM FROM A FOIL WRAP

It’s a lot easier than it may appear to go from foil wrap pattern to a form like this one. As you can see, I made the final muslin out of actual muslin, with a center-front separating zipper, which certainly simplified the foam-stuffing part of the process. There’s a more detailed account of the whole process at my blog, including a list of a few helpful tools.

A key feature of the finished form is the second cover, made from a smooth and somewhat slippery dancer’s leotard stretch knit, also listed at the blog, which not only makes the cover presentable, but very usefully smooths out the angularity of the rough-cut foam inside. This second cover was not made from a pattern, it was just roughly shaped and stretched to fit. The soft, pinable lightness of the finished form is a blessing, compared to any other forms I’ve used, so what started as a quick-and-dirty form project has turned into my first choice, form-making method, since these forms are so pleasant to work with, and so easy to store. They’re more like pillows than furniture!

The hard—well, harder—part of the whole project is the slow, future refining of your form so it really does help with fitting and draping. This doesn’t mean necessarily that the form needs to become more exactly like the body it serves, but it does mean you will need to adapt the form to your fit-to-drape process, so that the garments you drape on it come out as you wish. For example, if there’s a level of ease reduction that you’re rarely going to want to exceed, the most useful thing your form can do is to match that, not your no-ease shape. But whatever you want from it, your dress-making clone will very likely need to be massaged over time. Details at the blog!