SEW | PROJECTS

BASIC SHIRT CONSTRUCTION

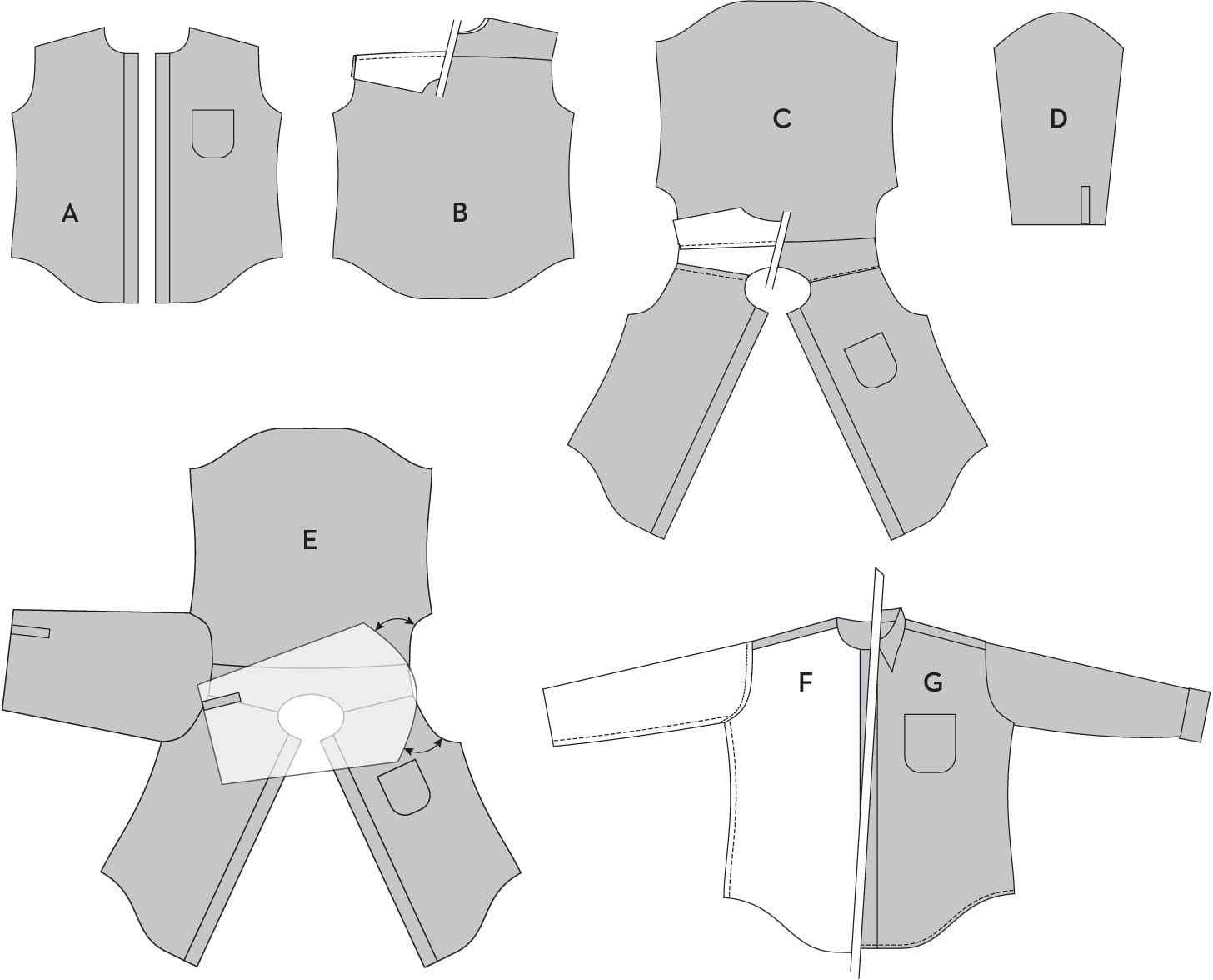

THE SEQUENCE

The diagrams on these pages provide a quick overview of the most basic sequence of steps typically used to put together the most basic sort of shirt, with a plug at far right for inserting sleeves after the side seams and underarms are complete, instead of flat. Obviously, there is an enormous range of different construction sequences that different garment details and finishes require, several of which you’ll see in the following projects, and many of which are covered in detail in the two previous books I’ve written that are entirely about shirt construction, with very little on fitting (see Resources). The point of these diagrams is to make sure that all readers, including those who may have never made a shirt, have the same baseline introductory look at the process. Be sure to check out the downloadable pdf’s www.quartoknows.com/page/sewing-shirts for more construction detail on the following projects and making shirts in general.

The logic here, as with most sewing projects, is to join all the smaller garment pieces, like pockets, cuffs, and bands, to the large main pieces while they’re still unconnected to other large pieces and are as easy to handle as possible.

The first step before joining either the fronts or back to the yoke layers is to add details to the fronts and back.

1. Add pockets and front bands (A) to the front; complete any pleats, tucks, or gathers you may want at the back-to-yoke seam.

2. Attach the yoke to the back next (B), sandwiching the back between the inner and outer yoke layers in one seam and then pressing all the layers forward.

3. Next, join the fronts to the inner yoke layer only (C), and press these seams towards the yoke. The front edges of the upper yoke layer should be pressed to precisely cover each seam line, so edge-stitching along these edges can both close the yoke and conceal the seams beneath.

4. Construct the plackets and sew them on the sleeves (D); then attach the sleeves (E) before stitching the side and underarm seams.

5. Stitch the underarm and side seams all in one pass (F).

6. Finish by attaching the collar, cuffs, and hemming the shirt (G). The collar could also have been added before the sleeves.

The most common variation to this sequence comes from different collar types, some of which are layered between the yokes, and different hem shapes, some of which need to be finished at the same time as the side seams.

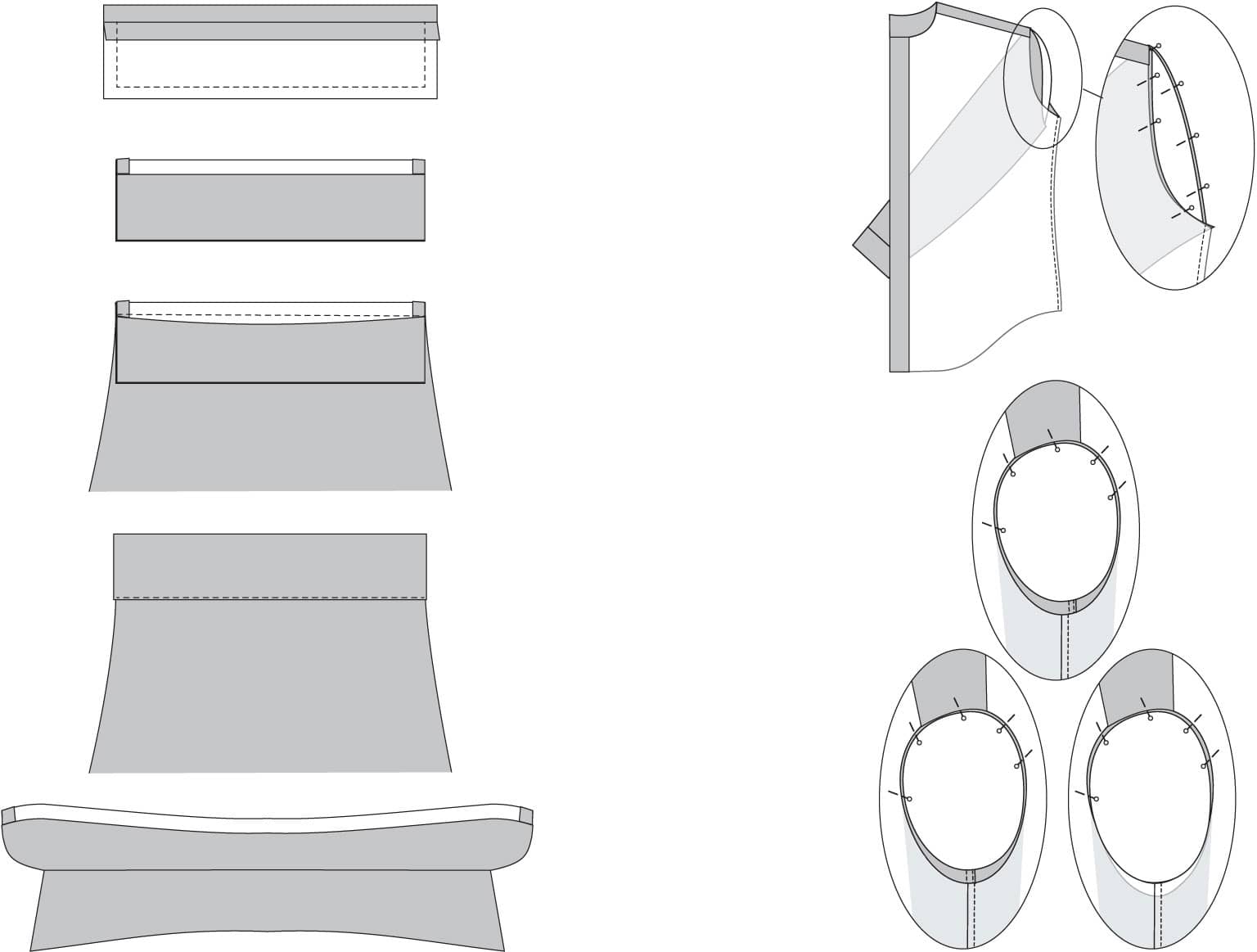

The diagrams, below left, show the common method for attaching cuffs and collars (or stands). These garment details are double layers, so, to start, you need to pre-fold the seam allowance of the inner layer to the wrong side along the edge that joins to the shirt or sleeve body, then sew the outer layers with right sides together with the garment edges. This makes it easy, once the piece is turned right side out and joined to the sleeve or shirt, to tuck the seam allowances inside and edge finish or hand stitch the piece closed.

The remaining sequence of diagrams shows how sleeves are inserted as tubes, not flat, as on the previous page. Turn the garment inside out and the sleeve right-side out, either with the raw edges matched as shown, or extended evenly to allow for joining with a flat-felled seam. Note, that this method of inserting a sleeve makes it much easier to adjust both the rotational alignment and the comparative lengths as you pin two already circular seams together, than to guess at how two linear seams might be similarly shifted before they’re turned into circles.

PROJECT

1

LOOSE, LINED SHIRT JACKET

This loose-fitting, lined, shirt-style jacket may appear to be a complex project, but it’s no more complicated than the basic shells we draped in the first half of this book, with no more extraordinary features beyond the shirts described in What’s a Shirt? (see here).

DRAPING FOR OUTERWEAR FIT

The inspiration for this project comes from the vintage Pendleton 49er shirt-jacket shown below on form #1. You can see the original garment doesn’t fit the form well, so I need to drape a test muslin to create a pattern or to correct the pattern I traced from the original, as described in the downloadable pdf, “Converting a Muslin drape to a paper pattern.”

The full lining that I decided to add to this unlined shirt is just a duplicate of the outer layer and cut from the same pieces; the only difference is I chose to separate the inner-layer front into a front facing and a lining section. There are no hidden layers or interfacing inside to control the fold of the lapels, which will just fold over, or not, depending only on how the shirt front is buttoned.

The most interesting challenge of this project from a drape-to-fit perspective, is how to drape it so the fit is not just loose, but loose even when worn as outerwear over other loose layers. The secret is to pad the form with an additional layer (or multiple layers, if needed); done by dressing the form in a typical garment or layers that you might wear under the shirt jacket. I added two padding garments and chose the thinner, more slippery one to go on last to help prevent the draping project from hanging up on the heavier, fuzzier, garment I put on first.

Here’s the original jacket back on the padded form, and it already looks better, in front anyway. Because the form doesn’t have arms, I can use the sleeves of the padding shirts as extra padding, instead of sliding them in the arms of the shirt jacket. And the sleeves fall right where I need the extra padding, along the side seams.

Seeing how nicely the padding filled out the jacket, I draped my first test on the padded form, again with the extra padding sleeves hanging inside, not outside, of the armhole.

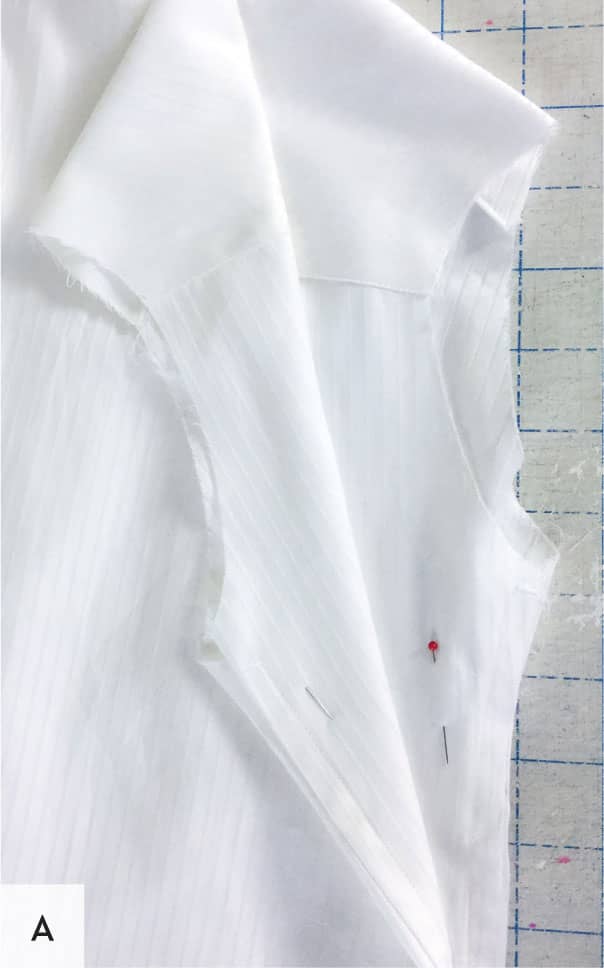

Knowing the asymmetry of this particular form (because it represents my body), I allowed extra fabric so the front muslin could be a bit wider to allow for a likely shift outward of the yoke width, and initially marked a front armhole to match (A).

Since the test drape now has the extra ease I need (from the padding shirts), I was able to remove the padding layers and proceed, knowing the extra ease they provided is now already built into the patterns I’ll be working with from this drape forward.

You can see a strain wrinkle forming from the low mid-chest area to my left shoulder (B), and the same thing, although less distinct, going toward the right shoulder. These are long familiar issues for my forward-shoulders posture, which tend to deform the front armhole curves forward just as they come into the yoke ends.

REFINING THE YOKE

To address this upper-chest wrinkle, I added length to the armhole curve at the front-to-yoke seam, by pulling more seam allowance into the seam from under the muslin where it crosses my knobby shoulder (A).

Once I was satisfied with the fit of the light cotton muslin, the next step was to trace the muslin and recut it in wool fabric to better evaluate how the actual garment would eventually work in a much heavier fabric. The yoke came first, and you can see the chalk lines I’ve drawn on it to address my first concern, the dramatic back curve that would need to match that deeply curved yoke-to-back edge (B). I decided that I’d rather reshape the yoke edge (no plaids or stripes in the garment fabric to make this too obvious) than straighten out the back.

The problem was that a straight line cut across the entire yoke width would result in yoke ends that were very different widths, given the asymmetry of my shoulder blades. The chalkline in the images shows how I finally determined to redraw the edge, with different width yoke ends at the expense of a straight seam (C) and (D). In retrospect, I’d certainly acknowledge that it might be wiser to favor a straight yoke seam, since a curved seam might be more noticeable than two different width yoke ends that that would never be seen together. Next time…

REDRAPING IN WOOL PRACTICE FABRIC

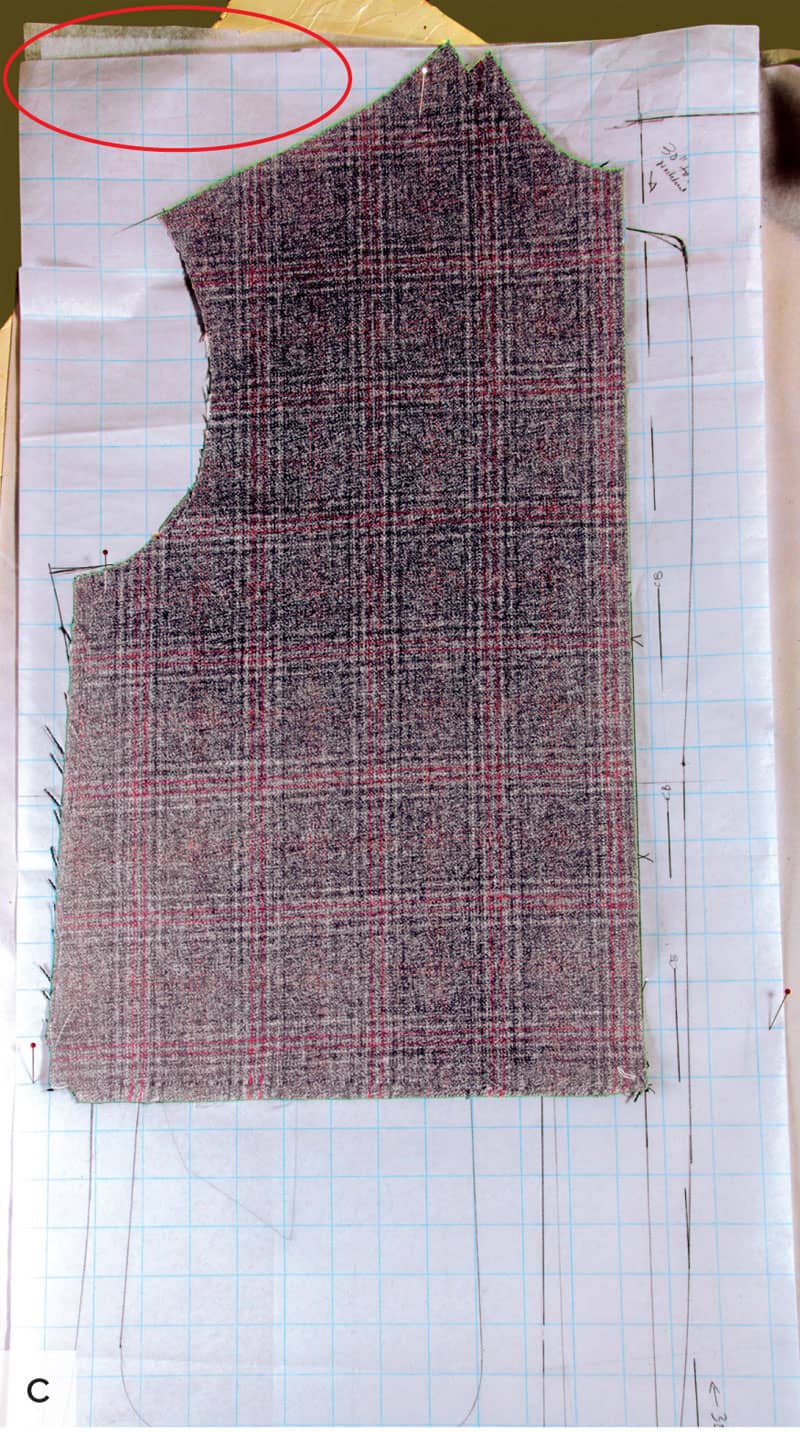

Now that I am working with these heavy nonraveling test fabrics, I decide that I can eliminate a difficult tracing step by trimming away the wool seam allowances. It is much easier to mark the fabric against a heavy cut edge than to try to trace through it, and I could possibly use this wool yoke muslin as a pattern guide. The chalk marking on the wool was frustrating because it brushed off too quickly, making it difficult to be precise. You can see how I started marking the seam lines in the circled details below, starting with the trimmed-off front seam allowances on the yoke. I continued carefully trimming the wool pieces exactly at the seam lines, at the armholes, and across the yoke ends at each armhole; I marked the side seam lines (didn’t trim the extra fabric away), since I would continue to adjust the side seams in future steps.

TURNING PARTIAL DRAPES INTO FULL PAPER PATTERNS

Below are the asymmetrical, trimmed woolen partial-muslin fronts and back pieces aligned at the centers with the right side of the fabric carefully marked (since it is difficult to determine right/wrong sides of this particular fabric) and the right and left sides also marked. If your front drape is symmetrical there is no need to cut both a right and left side, since they will be identical (A).

Also shown is the original traced front, with the facing shape copied from the source shirt-jacket, the inspiration for this project (B).

To trace the draped pieces (which I know fit well), I’ve positioned the still-aligned front pattern drapes against the original tracing (the one from the source shirt), using the centers and the shoulder seams to orient them. Circled on that image you can, I hope, make out the double layers of tracing paper I’ve slipped under the matched muslins and traced pattern (C).

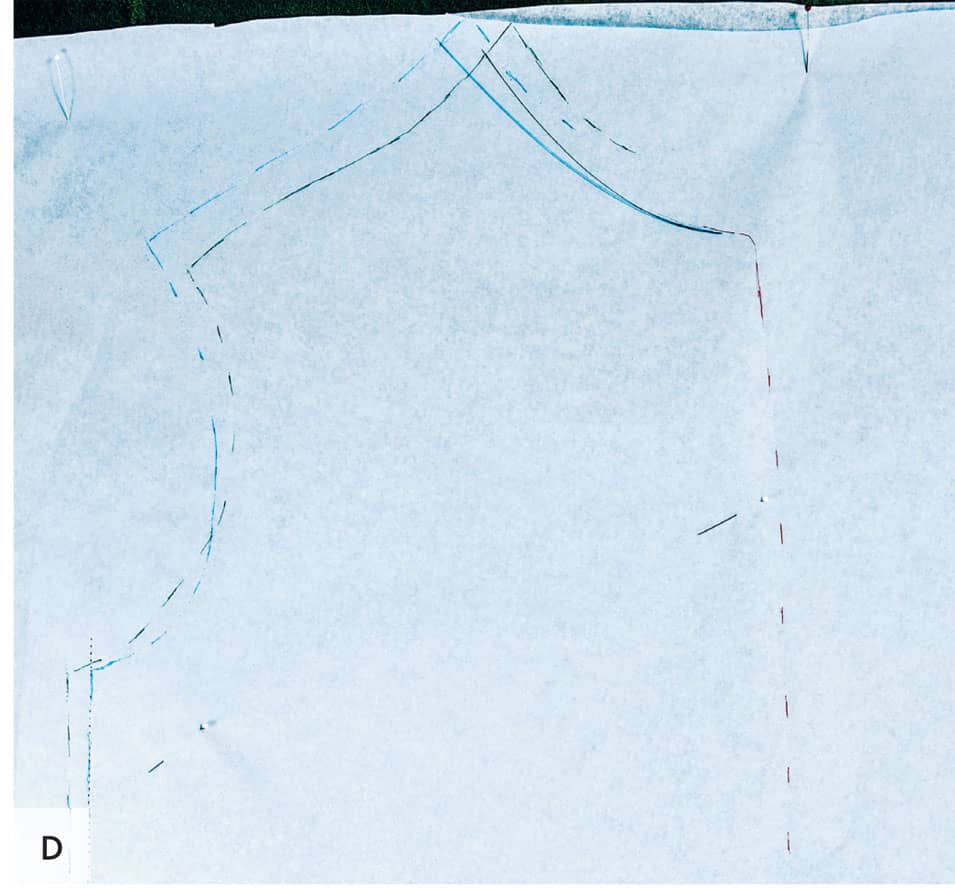

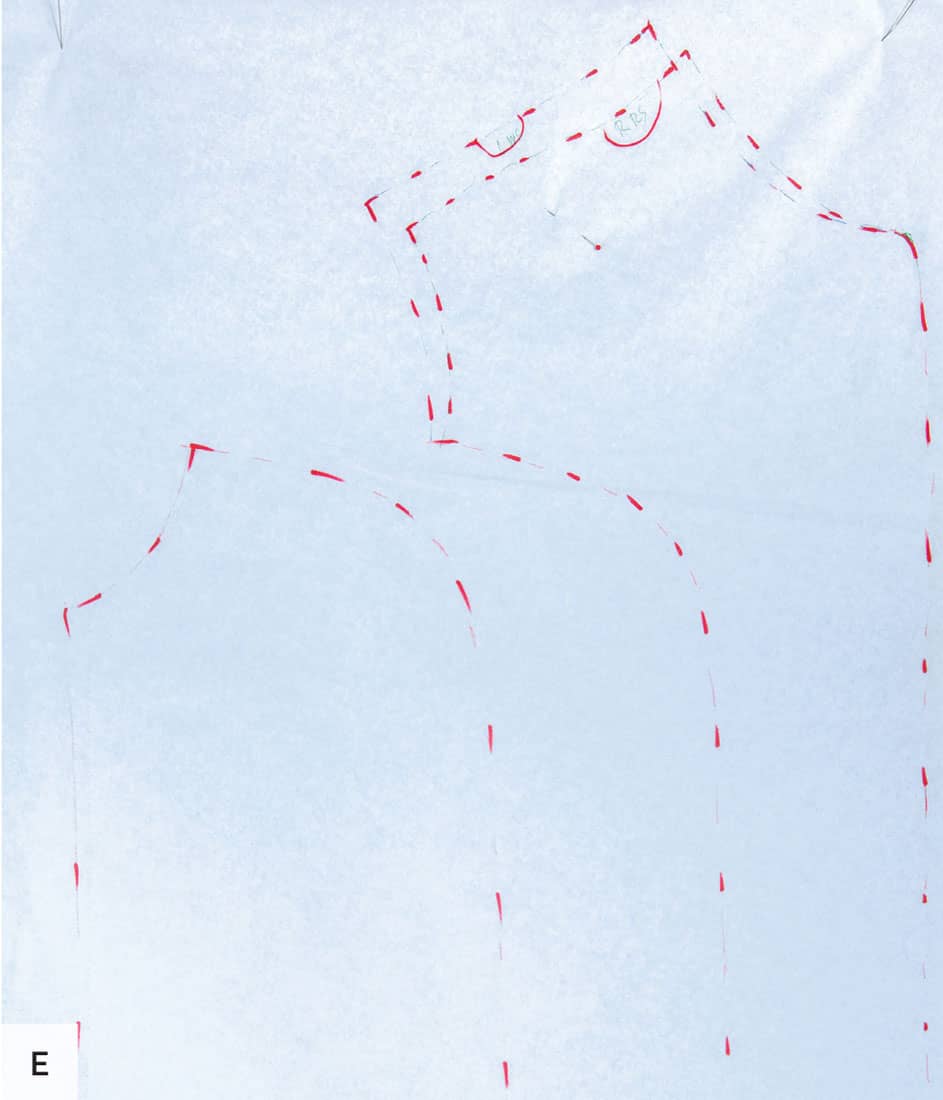

The next image (D) shows the two tracing-wheel-marked outlines I made onto those tracing-paper layers, one of each front aligned only at the front edge, which is the same on both fronts, and marked with red dashes. The differences between the two tracings are along the shoulder, neck, and armhole (where the asymmetries fall).

The bottom photo (E) shows, in red dashes, the same partially asymmetrical front pattern retraced to create separate patterns for the front facings and their identical lining inserts, again on doubled tracing layers so there will be one tracing for each of the asymmetrical facings.

At last, I’m ready to cut out the fashion fabrics.

SEWING YOKES TO OUTER AND LINING LAYERS OF FASHION FABRIC

Refer to the downloadable pdf, “Converting a muslin drape to a paper pattern” to confirm where and how to add seam allowances to the patterns, including the test-fabric yoke.

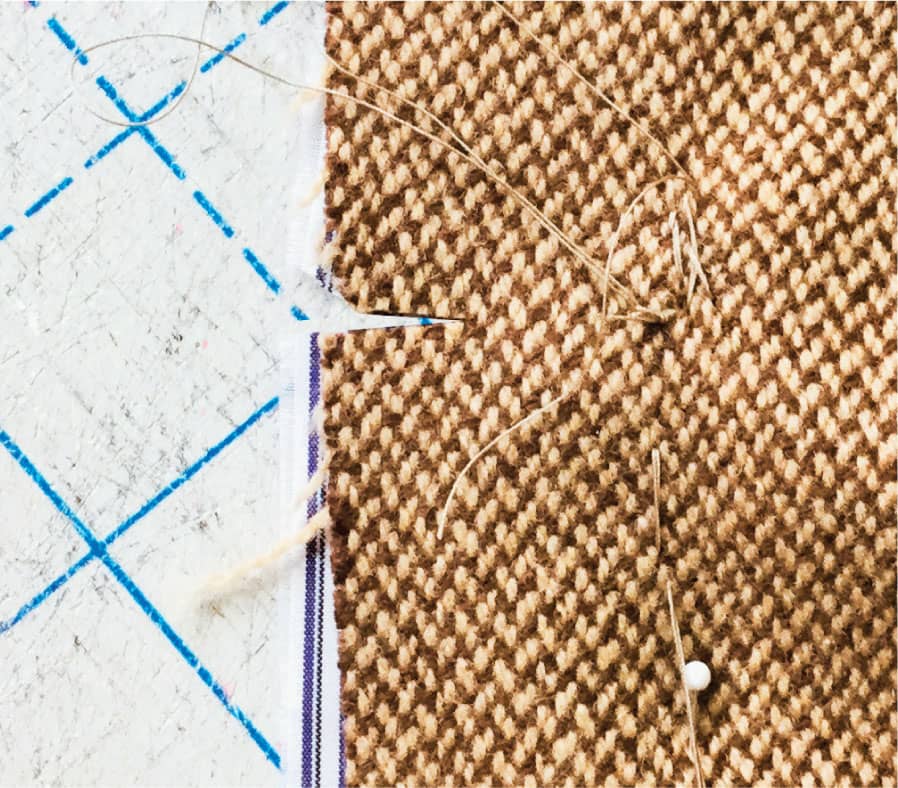

Right before cutting the outer layers of the shirt jacket (fronts, back, and yoke) from the fashion fabric, I decided I’d better thread-mark (since the chalk rubs off) the full front-edge stitching line (A), the start of the neckline, and the front armhole on each side (B). This way, I didn’t need to precision-cut those seam allowances since I had clear stitching guide lines and would be trimming the excess fabric away anyway. I did cut precise seam allowances for the already carefully fitted yoke and the edges joining them, but I allowed generous, rough seam allowances to all the edges below the armholes, knowing I’d need to be able to adjust them as I progressed with the actual fabrics. The yoke end in the middle image is longer than the front because I cut the yoke symmetrically, and the fronts and my shoulders are not symmetric, resulting in the uneven armhole curve that will need to be fixed.

Next, I joined each layer’s yoke to its respective front and back, after assembling the front facings with their respective lining pieces (C), taking great care to recall that right side out was different for each layer! I then tried both layers on the form, individually and then together, with side-seam pinning tests each time, to see how the outer layer and the lining were working together.

JOINING FRONT EDGES

Next up is finishing the front edges by sewing the facing to the garment front, with right sides together, starting from the facing’s width at the hem, around the hem curve (taken from the original garment) at the bottom, following the basting along the slightly curved edge, up to the most critical little curve (which is not a pivoted corner and which has to exactly match its opposite—careful marking and slow stitching!) where the front becomes the neckline, then onto the marked points where the two neckline seams would flip out to be joined together inside the collar layers. The little red mark on my form’s neck is, of course, the center.

TESTING COLLAR PATTERNS

I made a tracing of the original shirt jacket’s rather too-pointed collar, for my taste anyway (A), and a drawing (B) of a collar with ends long enough so they could easily overlap and button across my neck when the fronts were fully buttoned up. I created this collar pattern by basting a variety of single-layer heavier-muslin sample shapes to the collar allowances on the form and fiddling with them, as shown. The three images of different shaped collars in muslin tests didn’t make the cut, because I didn’t like their straight seam line at the neck edge, unlike the curve I’d borrowed from the original shirt jacket for the rather odd, but doing-its-job winning design.

MAKING AND JOINING THE COLLAR

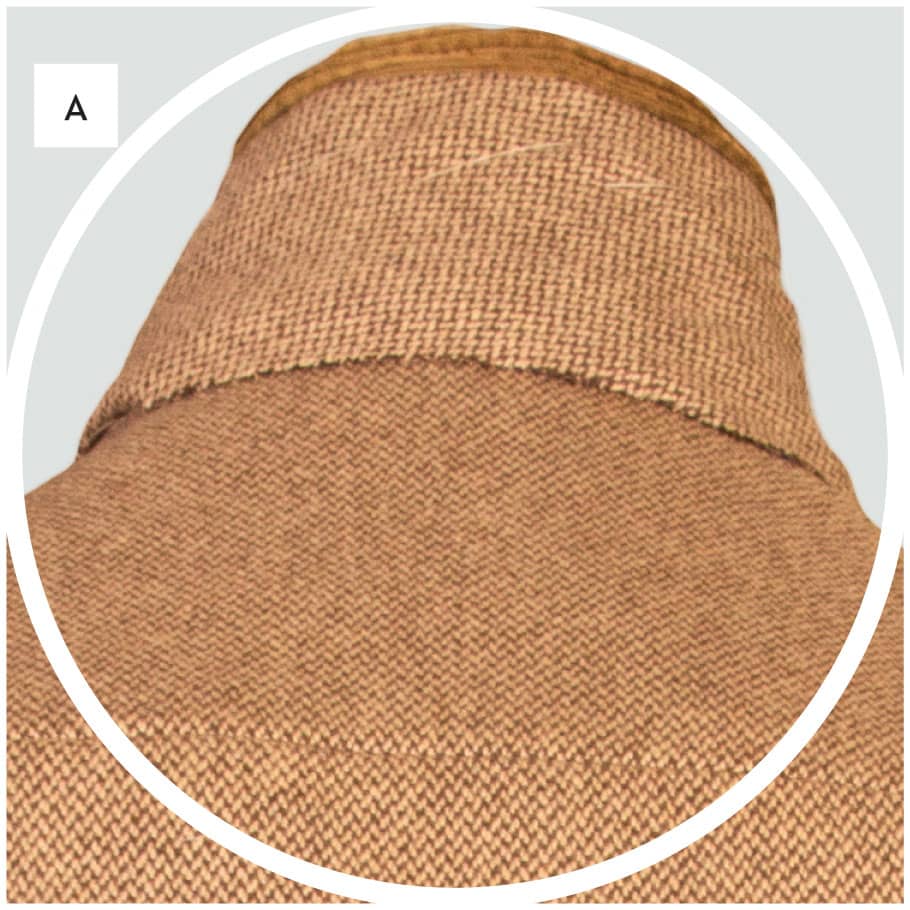

I’d been saving an old pair of corduroy trousers with a ripped-out back pocket (not made by me!) to swipe some of its nicely colored fabric, and this was just the opportunity for which I’d been waiting. And, as you’ll see in better detail in project 4, I’m currently on a “wrap, don’t turn corners” kick, so that’s the method I chose to use to make this collar. The idea is to cut the under-collar fabric and any interfacing (here, I used a simple muslin layer, same fabric as the test collar as interfacing) exactly at the outer collar seam lines, and only the outer collar layer with seam allowance (the seam allowance should be approximately twice the width necessary to fold neatly around the other layers; a test collar is required). This wrapping of the extrawide seam allowance on the outer collar is done in exactly the way described for princess-seam edges prep (see here), except the raw edge is folded under. Top- and/or edge-stitching holds the wrapped layers down. Fast, clean, and a-typical, what’s not to like? The inner collar layers get joined to the neck line—ends carefully positioned—just like a standard collar, and the woolen under-collar (nonraveling and bias cut in this case) edge is closely hand-whipped over the seam (A) to close it all up. For more step-by-step details, refer to the downloaded pdf, “Construction of the Loose-Fitting Shirt Jacket.”

SEWING THE SIDE SEAMS AND BASTING THE UPPER NOTCH

At this point, the outer layer and the lining are joined only at the front edges and around the neckline, and will stay this way until the final hemming, when they’ll get a few strategic tackings, to secure the lining sleeves to the outer layer at the armholes and perhaps a few actual joined edges along the hem or side seams; I am not sure yet. Sometimes, linings hang more smoothly if left separate at the hems.

It’s time to try on the partially finished garment, so I pin all the sides together separately, on the form, to smooth the layers to each other, mark the positions with a single clip, and then take a few strong, looping basting stitches right at the top of each side seam through all the layers…and slip it on for the first time.… Ah, it’s working!

ADDING SLEEVES

Because the outer layer and lining layer are still easily separated, it’s also easy to add the sleeves, once again taking care to keep wrong sides together. I choose to join the lining layer’s sleeves flat, so I can sew the sides and underarm seams in one long seam. Then, for the outer layer, I insert the sleeves in-the-round, after closing the side and underarm seams. I’ve used the sleeve pattern traced from the original garment, and the armhole curves, which were slightly altered during the initial draping (but remember, I trimmed the armhole curves in the wool-draping step so they’re already the correct shape). Refer to “Pin- and Wheel-Tracing” shown here. So, all looks good, and now the added benefits of a lining appear: I get to forgo any armhole seam finishing, and even get to press the outer layer’s seam allowances towards the sleeve, which looks more jacket-like than towards the body would.

And here I stopped.

READY FOR FINISHING

The remaining finishing steps, including a decision on outer-layer pockets—and buttonholes—will take much more time than I’ve got before I need to submit this book! Much to think about—at my leisure! Refer to the downloaded pdf, “Construction of the Loose-Fitting Shirt Jacket,” and to my blog for more finishing touches.

PROJECT

2

FITTED V-NECK DRESS SHIRT

The muslin for this project was originally draped on form #2 (see here), and as you’ll recall it was a fitted shirt with neckline darts, which we will now transform into a dress shirt with the darts hidden behind a V-neck collar.

Starting with the finished drape, I added extra width on the back-draping piece to allow for a small tuck on each side of the yoke (A). I positioned the tucks close to the sides to provide extra ease the entire length of the shirt, allowing deeper pin-outs through the waist area and more flexible shaping options. Notice how I was able to remove excess ease at the center back (B). And, those folds at the front neckline are ready for their dart conversion!

NECKLINE, DARTS, AND PATTERN PREP

Next, it’s time to finalize those collar-hidden darts, so I needed to first design the perfect collar. You can trace a collar from another pattern, a source shirt, or drape extra fabric to create your own design. I made a collar mock-up with a straight-edge neckline, and carefully centered and balanced it around the form’s neck until I was pleased with the shape of the collar and the garment neckline it established. By folding the collar up, I was able to mark one side of the drape with the new neckline. With the darts and neckline marked, and the collar shape looking good, I was ready to take the front drape off the form to create the front pattern. I folded the drape in half along the center and around two carbon paper sheets to wheel-trace, with a ruler, pattern lines for both the dart and neckline, including seam allowances. You can see the symmetrical stitching guides for both these details on the unfolded muslin (A). Note that I also marked symmetrical armhole curves and front-to-yoke edges, having decided that I could safely cut these, too, on a fold, since the fit didn’t appear very different as draped and would be draped again anyway. I need only the top, right half of the front drape going forward. As usual, I included extra-wide seam allowances. Refer to the pdf, “Converting a muslin drape to a paper pattern” for more details.

You can see how I used the folded drape to cut out two full-length fashion-fabric fronts (B). I added center-front closure seam allowances and extended the side seams with a ruler, aligned to the angle I’d draped earlier at the lower ends of the carbon-marked muslin and again I included wide draping allowances.

I stitched the darts about half way, leaving the rest to press to shape (C). I find it’s easier to curve these folds inward and more safely out of sight beneath the collar with my iron than by stitching. Perhaps, I should have better shaped the allowances at the dart ends to avoid those deep folds, but at least they fall outside the collar seam line.

REDRAPE THE FRONTS AND BACKS

Now begins the redraping for the front and back. I almost always feel compelled to redrape with new-to-me fabrics and/or a new pattern. The first step, as always, is to position and pin one yoke on the form; and in this case, it will be the inner yoke, wrong side up. I cut the yoke layers on the bias with a center back seam, so the striped patterns of the fashion fabric will mesh nicely when joined to the fronts—something I noticed in an earlier drape.

I’ve also cut out the back with just enough extra width so I can stitch out the entire vertical center-pinning from yoke to hem to add shape and style to the back. I pin the back to the yoke, matching centers and curves, and proceed to do the ease reductions, carefully and as symmetrically as I can manage, based on marks lightly transferred from the grey muslin drape, shown shown here. I then lightly mark the seam lines where the back and inner yoke will join later.

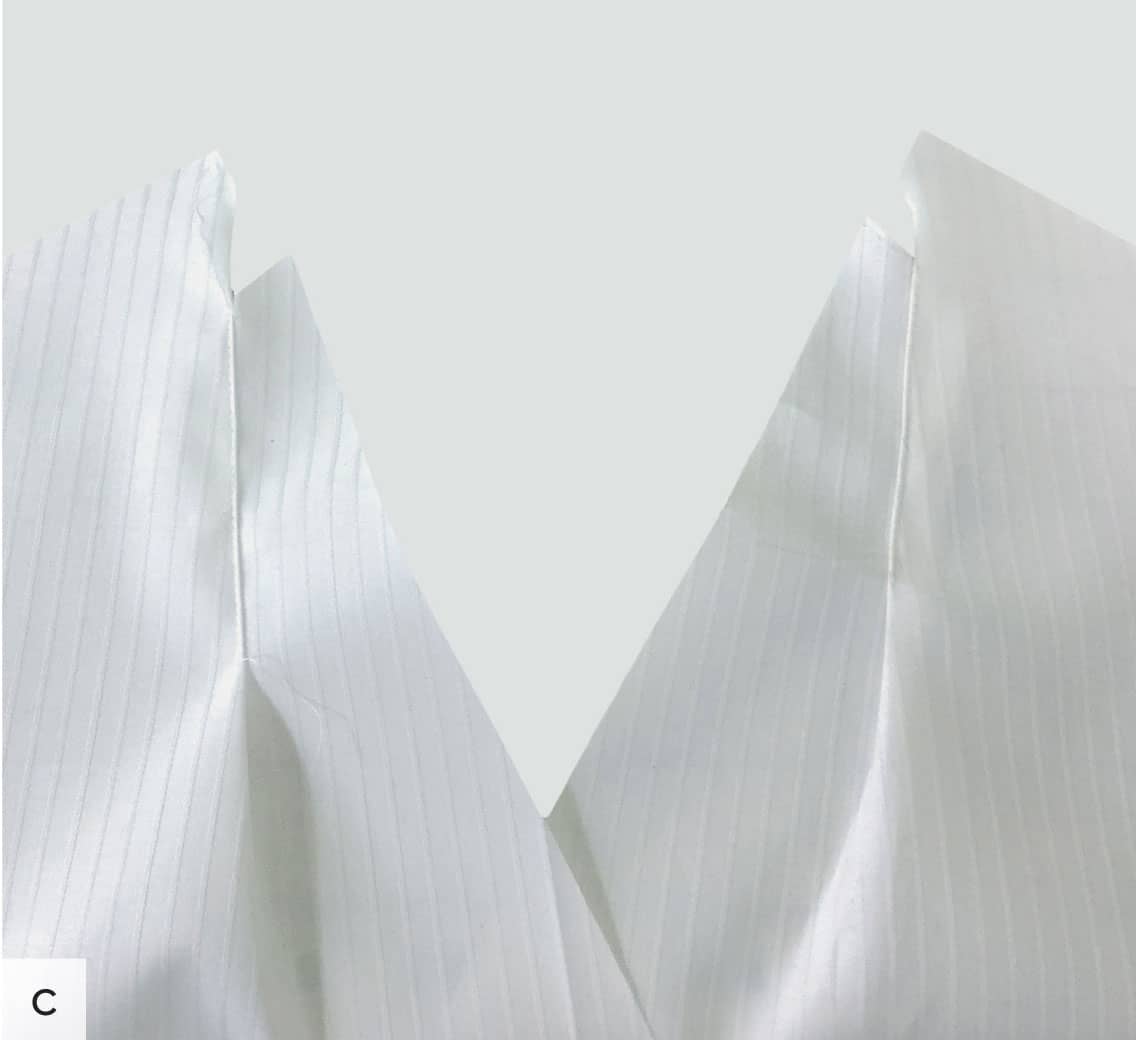

The rest of the images record my careful efforts to align the fronts to the inner yoke (A, B), and then to the outer yoke layer, pinned all together (C). Note how helpful it is to be able pin straight into this foam-filled, home-made form (see here). I can also bring my iron right up to the form, as needed, to create or remove a crease.

I aligned the folded-under edges of the fronts and outer yoke in much the same way that I butted the cut edges of the woolen yoke and fronts in the previous project (see here), and gently pin-marked match points and crease-marked seam lines once the draped pieces looked right. Now, I’ve got just enough information to take everything off the form, join the fronts as marked to the outer yoke, arrange the yokes right sides together without yet joining the inner layer to the fronts, and then insert the finished collar and neckline facings between them and stitch everything in place together along the neckline. But first, I need to drape the facings.

JOIN THE COLLAR BETWEEN THE YOKE LAYERS

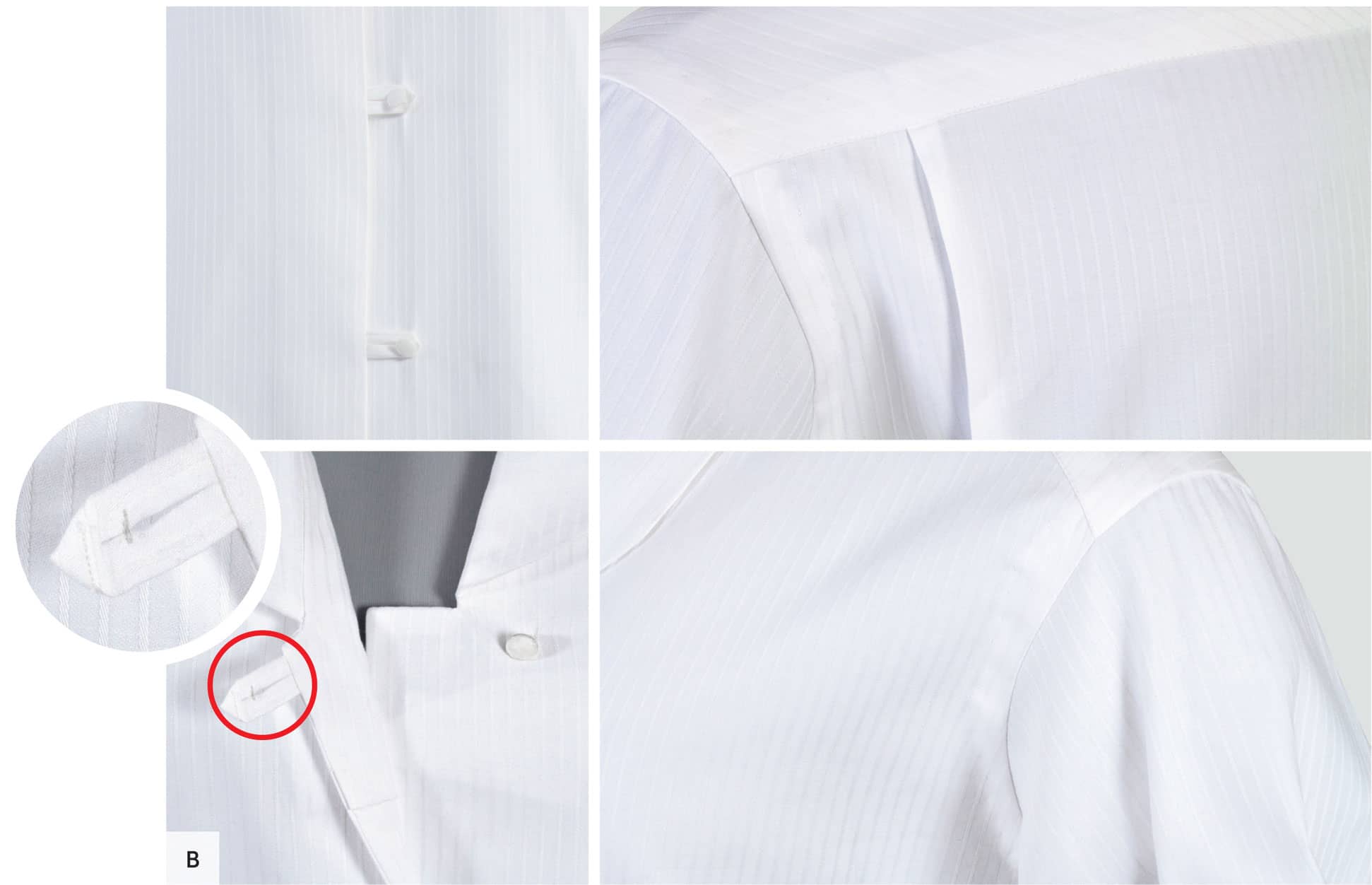

Rather than cutting complex one-piece yoke-to-hem facings, I chose to split the facings into simple separate neck and front facings so I could cut them both as on-grain rectangles with the lovely, smooth selvedges of the fabric serving as the edge finish. I started with the neckline rectangles positioned parallel to each front neckline, with the upper ends extended up and under the yoke fronts for about an inch (2.5 cm). I pinned and basted all the layers so the collar was sandwiched between the yoke layers in back, and the right side of the garment and the right side of the facing in front, making sure the collar was right side up on the garment front! I then stitched from the center front of the neckline, all around the neck to the opposite neckline center front. You can see the extended lower end of one neckline facing waiting to be joined to the lower facing (A). Unfortunately, once I was finished, I discovered that I hated the oval outer edge shaping I’d cut for the collar. It looked fine in orange gingham on green—and awful white on white it resembled a big platter!

So, off it all came, stitching removed, collar recut, turned and topstitched all over again, and reinserted. And after a well-deserved break, I was ready to add the front facing rectangles and secure the inner yoke front edges, still loose on the inside. But first, before stitching the facings in place, I needed to add the little fabric button loops (B). For more details about making fabric button loops and joining the facing pieces, refer to the downloaded pdf, “Construction of the Fitted V-Neck Dress Shirt.”

For the front yoke edges, I carefully rearranged the inner yoke layer back into marked place, folding and trimming the front edge so it aligned with the outer yoke’s edge, so I can catch both with a single line of edge-stitching from the right side. You can barely see the unfolded inner front seam allowance extending forward in the before detail (inset A), and in the after detail (inset B), you can now see the edge-stitched outer yoke front with only the single-layer front below it.

ADD THE SHIRT BACK BETWEEN THE YOKE LAYERS

As you can see, the upper and lower yokes are nicely aligned in back, ready for me to insert the back (A). I’ve by now decided on, and stitched down, the ease-reduction darts and tucks in the back fabric, so it’s ready to go. Notice the wide draping allowances on both the yoke edges and the back edge, now carefully crease-marked on the back and inner yoke following my earlier seam-line markings (shown here), which now need to be trimmed (A, B).

I am now ready to pin and join the inner yoke to the back with a standard seam along the pressed creases. Once stitched, it’s easy to press the edge of the outer yoke carefully over to align with the seam. As this is a curve, I pressed the seam on a tailor’s ham (D), tacking the edge in place sporadically with glue-stick dabs, and finally topstitching along the fold to finish the seam and hide all the construction bits.

ADD THE SLEEVES

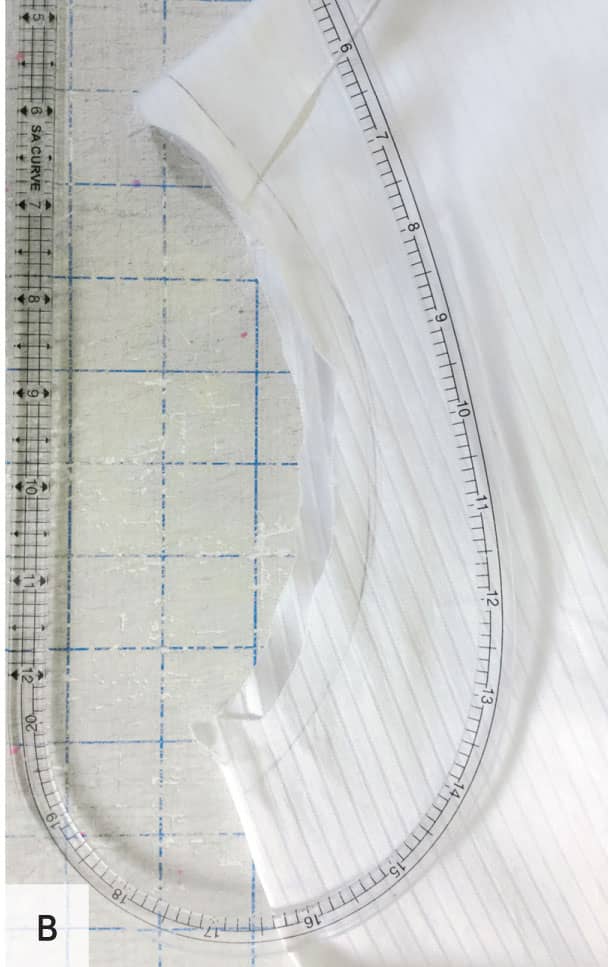

There’s a slight asymmetry to the armholes, as you can see (A), but they appear fine on the form, so I simply mark a uniform 3/8-inch (9 mm) seam allowance all around, using my curve ruler that’s perfect for this (see Resources) (B). I then cut basic sleeves from the provided medium-tall sleeve cap shapes, choosing the one with a cap-length that matches the length of these armholes, and cutting them with enough cap seam allowance width for a flat-felled seam. For more information see the downloadable pdf, “Flat-Felled Seams.” Once the sleeves are cut, it’s time to sew the sleeves into closed tubes, and then sew a continuous placket in each sleeve. Don’t attach the cuffs yet, but do insert the sleeves into the armhole openings. Refer to the downloadable pdf, Construction for the Fitted V-Neck Dress Shirt.”

As I folded under the felling seam allowance inside each cap seam line in preparation for the second stitching pass, the distortions from the pins I was using bothered me (C), so I tried something I’d not done before: I hand basted the to-be-felled edge onto the armhole (D). Except for the little knot near the bottom of the image, I loved how this looked, both the stitches and the seam itself. This was a lovely revelation, recalling the many reports I’ve read, and generally sniffed at, about the beauties of hand-finished custom shirts, even completely hand-sewn ones. Hand-stitched sleeve seams always come in for special praise, and I finally see why. Machine stitches have a hard look and add stiffness to the multiple layers. So, I ripped out the basting and redid the topstitching by hand all around, as the final finish.

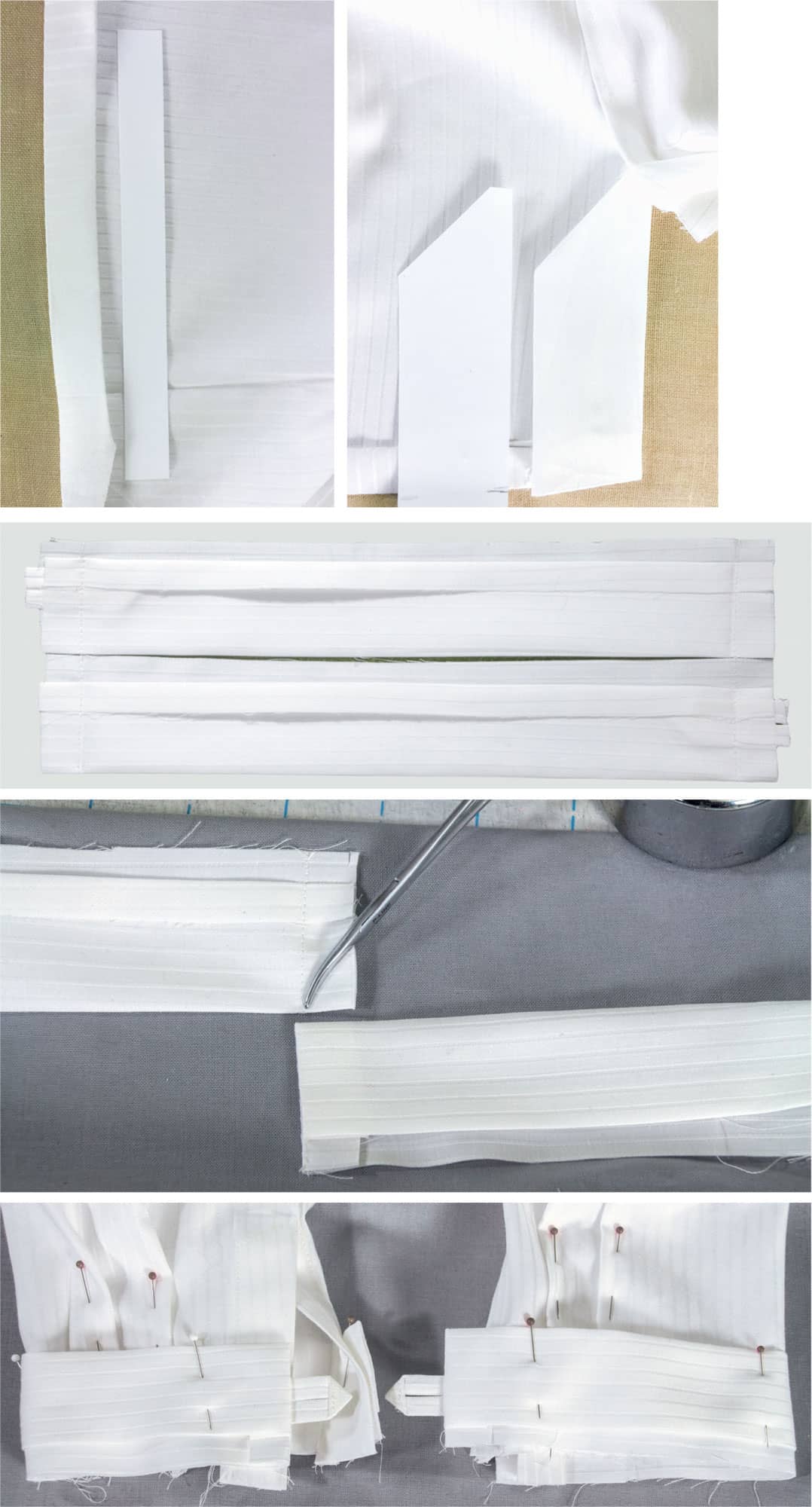

FINISH WITH THE HEMS AND CUFFS

The final edge finishing for this dressy shirt involves a lot of folding along straight lines, which demands accuracy and consistency. Here’s an easy solution: create custom folding templates, from moderately stiff paper, cut exactly to the shapes you want the final folding to create, then press the hem allowances around them before topstitching. The simple ones I made are shown here.

The cuffs I want for this shirt are narrow, squared off, and soft, so no interfacing; there is no interfacing anywhere in this project. The lovely satin-striped fabric is substantial enough and can easily be further stiffened, if so desired, with a little spray sizing You’ll notice I inserted another button loop into each cuff, but otherwise I am making them as described in the downloadable pdf, “Construction of the Fitted V-Neck Dress Shirt.” And I always bring out my indispensable, fine-tip forceps to ensure perfect points when turning corners; you’ll find detailed directions for this tip in the same pdf.

THE DETAILS

Working with white fabric is always a bit stressful, especially on a project that’s as much an ironing odyssey as this one. It is so important to stop and press after each step. I always rely on a tissue-paper press cloth. I use the same light roll-paper for this as for pattern tracing, and kept the iron temperature lower than the cotton setting.

Note the slight curve I nudged into the hidden dart ends at top right (A), and the tiny hand-stitched bartack I added to the back of the top-most button loop to fine-tune just where I wanted that button to rest (B). Again, the downloadable pdf, “Construction of the Fitted V-Neck Dress Shirt” is a wealth of detailed step-by-step guidance.

PROJECT

3

FITTED WRAPPED SHIRTDRESS

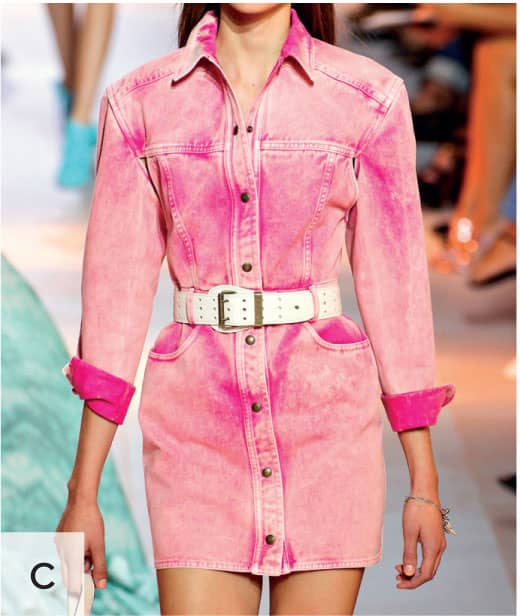

All it takes to turn any shirt into a shirtdress is lengthening the hem so it’s long enough that the wearer is comfortable wearing it as a dress, not just a top. These shirtdresses (A) and (B) are typical examples, although the pink one (C) is reshaped a little at the sides and below the waist to allow the skirt portion to be form-fitting. The belt makes it hard to tell just how loose it is at the waist, but there’s probably some shaping there, too—which is nothing more than what you’d do on the sides of a fitted shirt, starting above the hips and continuing as far down as you’d like.

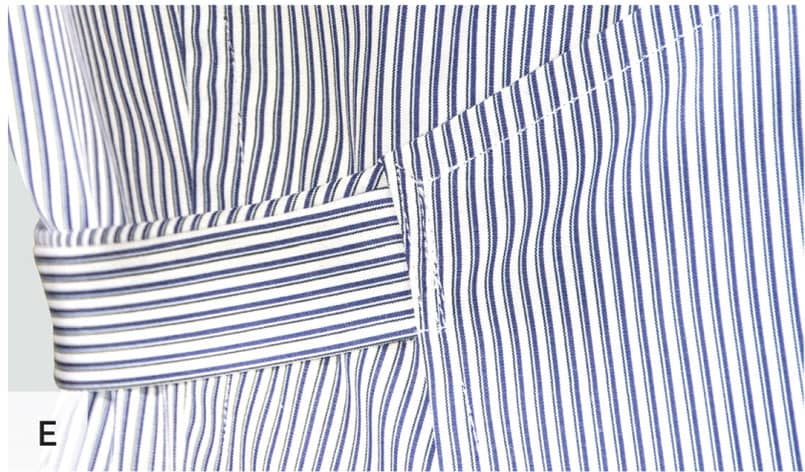

The remaining examples (D), (E), and (F) clearly represent another simple option: choose a skirt pattern you like and attach it to your chosen shirt with a waistline seam, allowing an abrupt change in total ease.

More interesting, I think, is to combine either skirt option (straight or full) with a complete restyling of the top, as for this shirtdress (G) with the deep V-neckline and wide collar which, becomes a wrap closure at the waist and down the skirt front. Typically, the front closure on any shirtdress extends all the way to the hem, but it doesn’t have to. And, the possibilities that different sleeves can add to the redesign of a shirt to a shirtdress are endless.

The wrap shirtdress (G), the inspiration for this next project, is where I found and borrowed the collar shape and the wrapped neckline, designed to close at the side waist. I did deplunge it a bit! I also decided that the wrap ties would be visible only in the back, and the front looked better to me falling smoothly without darts (H).

I was highly inspired by the fabric, a very fine cotton, that on close inspection revealed a much-minimized version of the striped pattern found on utility fabrics called ticking, and used to be the default covering on equally utility-level mattresses and pillows. This connection, utility fabric with elegant shirtdress, kept drawing me towards a more utility-oriented concept for the project garment, more smock or even apron, than dress.

INITIAL DRAPES

To mix as much fitting as possible into a silhouette that I wanted to feel casual and relaxed, I first draped a darted front on form #3, dividing the shaping almost equally above and below the bus (A).

I then released the pinned upper darts (B). Initially, I expected to retain the lower darts, but after I reshaped the front to create the V-wrapped neckline, constructed a wrapped test muslin, and fiddled with it for a while (of course), I eventually decided that the lower darts could be released, as well (C). (Refer to the downloadable pdf for detailed instructions for “Creating a V wrapped neckline from a one-piece front drape.”

I also draped a darted back (D), but decided to convert the darts to reshaped side seams, by tracing off the pattern with the dart ease pinned out and the drape laid flat as described in chapter 4 (see here); this allows me to arrive at the dart-free back muslin (E). Before I was sure how I’d eventually handle the wrapped front, I cut a long strip of extra fabric, about 2 inches (5 cm) wide and used it to simulate a variety of belt-tie positions and estimate final lengths. Then I cut out and pin-tested a few sample collar-shape muslins. There is downloadable version of the chosen pattern in the online content, but you can certainly trace a collar from an existing pattern or a source shirt.

JOIN FRONTS AND BACK TO OUTER YOKE

Satisfied with the shape and design of my wrapping muslin, I used it as the pattern for the fashion fabric, simply extending the straight, vertical side seams as long as necessary to allow a generous hem length, the final length to be determined later. I stitched the outer yoke to the fronts and back, and as you can see (A), I found some front-to-yoke tweaking was necessary with the new fabric and the bias-cut neckline, so I removed the stitches from the outer yoke seams I’d overconfidently stitched before checking the pieces in the fashion fabric on the form. I then restitched the front to outer yoke seams to reflect the pinned corrections. I needed at least one yoke layer in place to check and redrape all the other parts and seams, like the front waist-level darts (B) I’m still considering, and where to position the collar (C).

ADD THE COLLAR WITH THE INNER YOKE AND BIAS FACING

To attach the basic stitched-and-turned collar, add facings to the rest of the neckline (the yoke finishes the collar seam), and create the outer back waist tie and inner tie, I cut two bias strips for the facings, one of which was long enough to be included as part of the back-waist tie. I then reinforced one edge of each facing with a fusible strip of interfacing (A) before stitching the facings to the garment front (beyond the collar). The narrow interfacing helps minimize stretching along the bias neck edges but still allows the facings to easily mold over the many body contours they encounter from neckline to waist. The bias-cut helps prevent the fabric edges from raveling so I won’t need to edge finish the facings on this very tight fabric, but if the fabric was a looser weave, I’d have used a bias-cut interfacing and fused it over the full width of the facing. For more detailed instruction, refer to the downloaded pdf, “Construction of the Fitted Wrapped Shirtdress.”

You can see how I layered the inner yoke and facing strips, sandwiching the collar in between so the neckline is completely finished by those inner parts (B). I then folded under the front and back seam allowances on the inner yoke to match the existing seams for the outer yoke. These edges were carefully glue-stick basted in place on the inside, then secured by edge-stitching the upper yoke from the garment right side, just as in the previous project (see here).

ADD SLEEVES, TIES, AND HEM

Next, I stitched the side seams with hand-folded, flat-felled seams, leaving a roughly 3-inch (2.5 cm) waist-level break in the stitching on the left side seam for the inner wrap tie. I can easily shorten the gap in the stitching after seeing exactly how the inner tie extension fits through the opening.

With the sides closed, I made sleeve muslins using the medium-tall sleeve cap shape from the provided pattern collection, measured to fit the armholes. With the sleeves slipped onto the form and into the armhole openings, I was able to simultaneously find the final seam lines I’d use for both the armholes and the sleeves (A, B). I then used each marked test sleeve as the pattern to cut right and left, custom-draped sleeves from the fashion fabric, and inserted these as tubes, into the already closed, also custom-draped armholes.

A few distinctive and precisely made finishing details would be, I thought, sufficient to lift this very simple garment into something a little special. You’ll find detailed descriptions for everything shown here in the online material for this project, but here are the highlights.

I first made the short inner-wrap tie (A) from two pre-folded fabric layers simply edge-stitched together (B, C), and then joined this to the inner wrap edge with a top-stitched patch (D).

The longer neckline facing strip also faces the back wrap-tie, which is joined to the edge of the overlapping waist layer, so I arranged its bias-oriented stripes to peek out slightly above the outer wrap-tie layer, forming a sort of faux-piping (E).

And as you can see (F), I continued to exercise my fondness for folded buttonhole strips by adding one to the end of this more visible of the two wrap ties.

And, a double-fold machine stitched hem is the way to finish (G).

PROJECT

4

TIGHT DENIM WESTERN SHIRT

This was the one project that I had in mind to include in this book from the beginning, an obviously classic design, well-suited to a tight fit, and with many details I looked forward to exploring. The basic pattern came directly from the last test muslin developed in chapter 5 on form #4, the athletic male form, used at top far right on which to also evaluate the placement and shapes of the pockets, flaps, and Western yokes, initially drawn on pattern paper and tested here with muslin scraps.

Once I’m happy with each front detail shape, after having made a few slight design changes, I redraw the patterns, trace them onto manila-folder-weight paper to create custom folding templates, like for project 2 (see here). These templates, cut to the exact shape of the final, finished pieces, ensure the folding under of seam allowances accurately and symmetrically. The heavier paper reflects the heavier denim fabric used for this project. As usual, I use ironed-down glue from a glue stick to secure the pressed edges.

Templates also offer an easy way to line the pocket flaps: Just fold each layer (denim upper layer and contrast lining layer) around the same template separately (A), and join them right sides out with topstitching, instead of trying to perfectly turn all six points, which would be difficult). I use the same pressing-template process for the front yokes (B) and for each pocket, including the upper hemmed opening edge.

ASSEMBLING THE SHIRT FRONT

Once I’d cut the denim front, back, and yoke from the pattern from chapter 5, I assembled the pieces into testable shape, with front bands completed, and fronts and back joined to the yoke layers (the outer yoke not yet secured in front, to allow for placing and catching the add-on Western front yokes). I then discovered that, despite all my efforts to eliminate any darts at the chest, this heavier, stiff fabric insisted on folding into the inarguable armhole darts that are apparent in the close-ups below.

I simply pressed the dart folds down into actual darts to be dealt with later, and carried on with the final placement and marking for all those template-formed details, a long, painstaking process for which measuring tools were mostly unhelpful, given the slightly asymmetrical shoulders. Placement was all done by eye, and with so many microshifts and repinnings my chalk placement marks barely held and were mostly replaced with last-minute pins before they disappeared altogether.

The oddly extended fabric at the neckline center was also added at the hem (where it’s more useful than at the neck). It’s there to allow extra front band length to manipulate the collar placement and finish the rolled hem. The neckline extensions were a momentary whim, but the extra length did help with handling during the finishing steps.

Note that the finished, but as yet only pinned-on, pockets are only topstitched at this stage, leaving the edge-stitching until the pockets are stitched in place on the shirt front (after the darts are stitched!). I left the front-yoke edges unstitched because they didn’t have wide enough seam allowances to be caught in the topstitching and would need to be edge-stitched down first. All these details are explained step-by-step in the downloadable pdf, “Construction of the Tight Denim Western Shirt.”

MAKE THE COLLAR

As usual, I draped a custom neck line with a ring of paper dropped, fitted, and then marked along the bottom edge onto the drape.

Follow these steps to easily create sharp, symmetrical points for the collar, just as I described earlier for the collar in the shirt-jacket project, but didn’t as completely document.

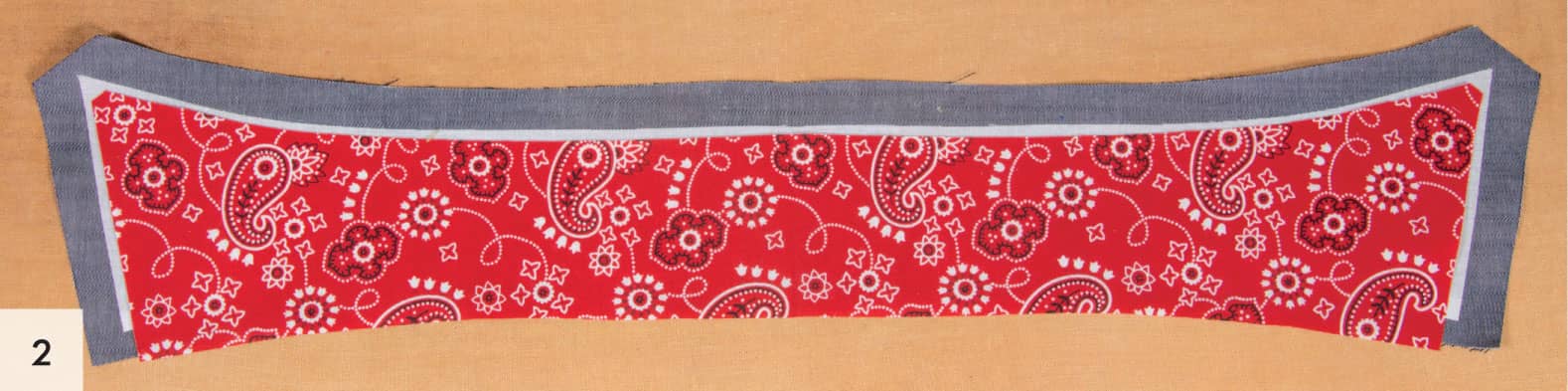

1 Cut appropriate interfacing to the exact finished shape of the collar’s outer edges so it extends into a seam allowance only at the edge that will be joined to the collar stand.

2 Fuse or baste (here, it’s fused) the interfacing to the outer collar, which is cut with enough folding allowance to make double folds that wrap around and over the interfacing and the inner collar layers, covering the edges.

3 Cut the under-collar layer a little smaller than the outer collar and so that it follows the interfacing edge closely (A). Trim off the points on both the collar layers to reduce bulk (B).

Follow the folding progression, as shown, using liberal glue basting and an iron. Carefully done, this process is the best path to really sharp, matching points (A) on less-than-square corners that I’ve ever found. I like the wrapped-edge effect as well.

My first test sample, with the pink inner layer (B), is shown both to encourage you to make at least one test sample and to point out a subtle detail. The garment collar above it shows how I wrapped the long collar edge after the short edges, while on the test sample I did the ends last, not noticing until too late that this order results in a miter that’s easier to catch securely with topstitching.

ADDING THE COLLAR AND CUFFS

To further prepare the collar for joining to the collar stand, I pressed its remaining unfinished edge to the wrong side, forcing the fold to follow the curve of the original collar pattern (A).

I machine basted along this fold using a zipper foot to get as close to the fold as possible without hitting it (B). This step holds in the excess length forced onto the outer collar, compared to the inner layers from the previous step, which I find makes for a smooth collar fold when worn. I then trim this seam allowance back to 1/4 inch (6 mm) after basting so it’s easier to match the stand seam allowance, also 1/4 inch (6 mm).

The other images show the steps I took to join the collar to the collar stand, which I’d previous attached to the neckline using a technique described in detail in my first shirtmaking book and the downloadable pdf, “Construction of the Tight Denim Western Shirt.” In short, it leaves the stand’s top edge open, ready to be joined to the prepared collar in just the same way as in the white-shirt project for joining cuffs to sleeves (see here). With the collar-insertion version, the stand is treated like a cuff, and the collar like a sleeve, with all the collar layers attached to one side only of the stand with the first right-sides-together seam. This leaves the remaining stand edge to be folded under (C) and caught with topstitching from the other side after you’ve tucked the collar allowances neatly inside the stand opening. The remaining images (D, E) show how to make the stitches of the first seam smoothly blend into the curve of the stand where the seam stops.

The remaining details show the cuffs arranged and pinned for stitching as described for the collar. Notice how the pinning can arranged to both hold the cuffs in place and the inner cuff layer out of the way of the subsequent stitching at the same time.

ADDING THE SLEEVES

Because I always choose relatively loose-fitting shirts when I make my own, I’ve never considered, nor even tested, the commonly repeated idea that shirt-sleeve caps should, like those of other set-in sleeve types, be at least slightly gathered or eased at the yoke edge before insertion. It’s always been obvious to me that this extra step is neither required for comfort nor needed for a smooth finish on my own projects, nor does it appear to have been done on any of my collected custom and ready-to-wear, mostly men’s, shirts.

For this tight-fitting project, I thought a slightly gathered sleeve cap might be worth trying, given the additional tension such a close fit subjects to every piece in the garment. So, this is what I’ve done for the three images below. My verdict (“Bah!”) is, I hope, understandable.

Unless I misunderstand how a gathered shirt-sleeve cap is to be done—and that’s certainly possible—it’s a clearly a mess. In the meantime, I’ll persist in ignoring this insertion method unless I’m working with fabric that can be iron-shrunk to make this sort of ease work more gracefully.

The tight fit does make draping a test sleeve in an armhole more difficult than with looser fits. After several failed attempts to position, adjust, and secure a measured cap to these draped armholes using just fingers and pins, I finally found a baste-on-the-form method that both drew the edges more snuggly together as I stitched and very securely held all in place. I even liked the look, in a sort of frontierish way, and have filed away the idea of using it as a finish on future shirt-like projects.

The images show how I the basted sleeve into the armhole, well pressed to smooth out the stitches, which were only applied to the top half of the armhole, since I couldn’t reach the underam area. The sleeves are now ready for machine stitching, or basting (to the inside of the stitches already there).

Note how the last image at right demonstrates the unpredictable, unmeasureable, but easily drapable, unique and varying seam lines that such a careful fitting can result in, on cap and armhole simultaneously.

Here, you can see my results after machine stitching the sleeves into place. Note that I’ve treated each side differently—this is a shirt for a fictional body after all—pressing the allowances out, in towards the body in the usual way (A) on the form’s right shoulder, and towards the sleeve (B) on the form’s left shoulder, just to see the differences. Subtle, to be sure, but clearly smoother when pressed out. Note the hand basting on the pressed-in side (lesson learned!) in preparation for the machine flat-felling to come.

You’ll also note the slight puckering along the seam that persists at the top of each sleeve. No doubt this is the problem cap easing is meant to solve, if I could only see how with nonshrinkable fabrics. It is, however, possible to carefully hand-stitch much of this away, pulling the slight excess lengths in from the wrong side, before going any further with seam finishing. If you’re willing to put in the effort…

STITCHING THE HEM

Here’s how I formed the hems, again slightly differently on each side, for comparison’s sake. Each edge was hand-folded twice, with glue-stick and iron in hand, on a padded surface so pins could help, just as described for princess-seam prep (see here). After thorough pressing, they were top- and edge-stitched as everywhere else on the shirt, with the front band ends out of the way, and then folded over these stitches and edge-stitched down symmetrically (lots of options are possible here) to provide a smoother and more interesting finish compared to trying to catch all their bulk in the hem roll (A), (C).

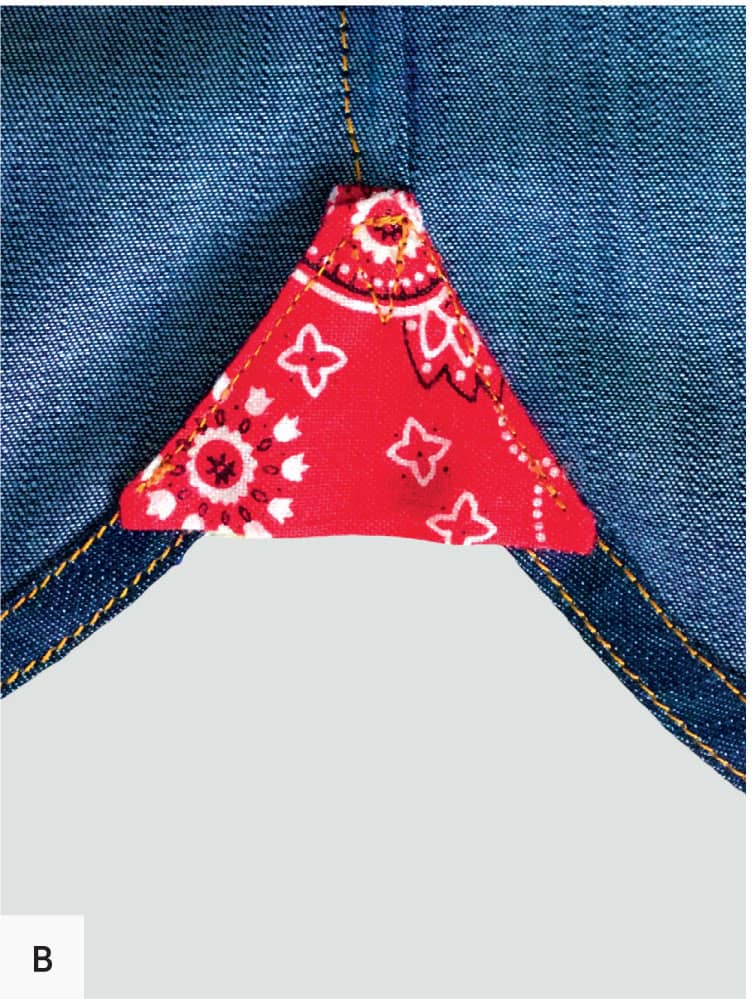

The little gusset attached on the other side depends on the hem curves blending into the side seam rather than across it, which requires that one of the side-seam allowances is clipped to roll the other way at the hem, which the gusset can neatly cover when it’s topstitched in place from the right side (B). The gusset itself is a turned triangle shape, folded at the bottom and left open at the top point, and then poked into the turned shape with the tip of my forceps, which nicely curve the stitched sides, as needed, to match the hem curves.

FINISHING DETAILS

The snap closures are, of course, the expected closure on a shirt like this, a bit hair-raising to install, but easier than buttons and buttonholes. I just couldn’t bring myself to do that to the collar stand ends—so I didn’t.

I hope something in all this will prove helpful in your shirt-making journeys. Let me know if any questions come up. I’m sure to have an opinion!