FIT | 2

FITTING: THE BIG PICTURE

DRAPING MAGIC

Here, again, are the diagrams shown here, comparing rectangular and modern shaped shirts with the armholes and necklines further simplified into three connected ovals, which I hope you can see captures the essence of the difference between the two garment shapes at the shoulders.

Now imagine that you could capture the exact positions and shapes of your own unique neckline and armhole ovals simply by dropping floating circles of magic string around each oval and shaping the magic string as you wish, and then freeze all the ovals in place, by flowing some other magic substance over them all, capturing both the overall shape of the shirt and the inner contours of the shoulders that connect the ovals and their exact distances and orientations from each other…and then, with a finger snap, convert all this to a flat pattern.

This is exactly what we are going do with this drape-to-fit technique I’ve been referring to, allowing the very real flexibilities of fabric itself provide all the magic we’ll need. We’ll do it in a different order, with no finger snapping (sorry!), but the result will be almost as magical, I think.

The real-world “magical object” we’ll “float” onto our target body to locate the openings is a yoke. Think of the yoke as the fabric equivalent of the connected-ovals schematic for the shirt openings at right, as well as a fabric device for capturing the contours, widths, and orientations of the two shoulders in between the neckline and armhole ovals. So, our first step, described in detail shown here, is to trace a yoke pattern, either from the included multisize pattern, or from a favorite commercial pattern, or even from a favorite shirt.

Once we have a fabric yoke, the contour of the actual back neckline determines how the fabric yoke is positioned initially on the body or on the torso form (no need for a center back measurement!). If the fabric yoke is cut wider than the body or torso form, you can easily fold the ends under at the shoulder edges. Then you will record the shoulder lengths of the yoke on each side of the neck (which might possibly be asymmetrical measurements). And, in our floating example, we can then “float” the armholes at the exact ends of the shoulders, which means ultimately your shirt will have perfectly positioned armhole seams, with sleeves that hang from your exact shoulder points.

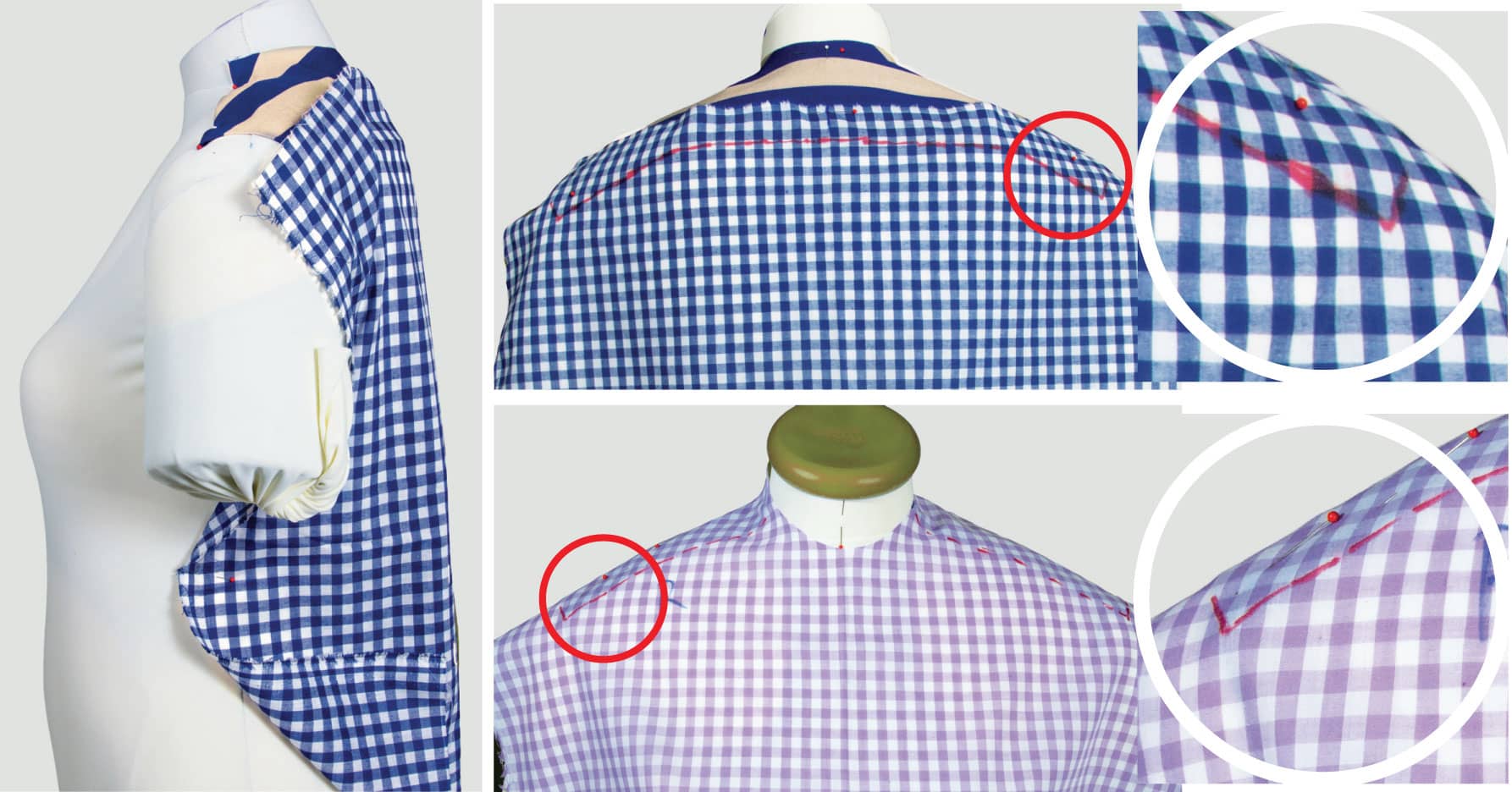

The “magic” for me starts with how this yoke, a completely abstract, symmetrical, geometrical, non-body-shaped, cut-out detail, can so easily and naturally mold itself to whatever shape it’s laid upon, while remaining quite smooth and relaxed. Here’s how the same yoke appears on six unique necks and shoulders. Each example shows how the yoke transforms without altering its pattern shape, except for a few straight folds, as needed to conform to the length and width of the actual body, along the edges of each shoulder and the front and back of the yoke.

AN “IN-A-NUTSHELL” INTRODUCTION TO MY DRAPE-TO-FIT PROCESS

Here’s a quick outline of my basic shirt-draping process. The step-by-step details, applied to various body shapes with various levels of fitting ease, follow in subsequent chapters, in which you’ll learn in detail, how to use the included multisize pattern as the source for your yoke pattern, front and back armhole-curve patterns, and a sleeve pattern with a cap length (the seam that gets sewn to the armhole) that matches the armhole curves.

1. Cut out the yoke, then position and mold it to a body or dress form as shown.

2. Next, cut two rectangles of gingham (the perfect draping fabric because its easy to see the fabric grain), each large enough to more than cover the front and the back of the body. For the front rectangle, guesstimate and mark a smallish neckline curve in the center. Drape the rectangles to fit the body or form front and back by placing the cut edges of the gingham pieces over and on top of the yoke. Pin both pieces to the yoke so the grain is perfectly vertical and square along all yoke edges. With permanent marking pen, mark the draped rectangles at the intersection of the yoke edges. Be sure to mark the shoulder ends of the yoke, too.

3. Remove the rectangles from the form or body. Allowing generous seam allowances, trim away the extra fabric along the markings.

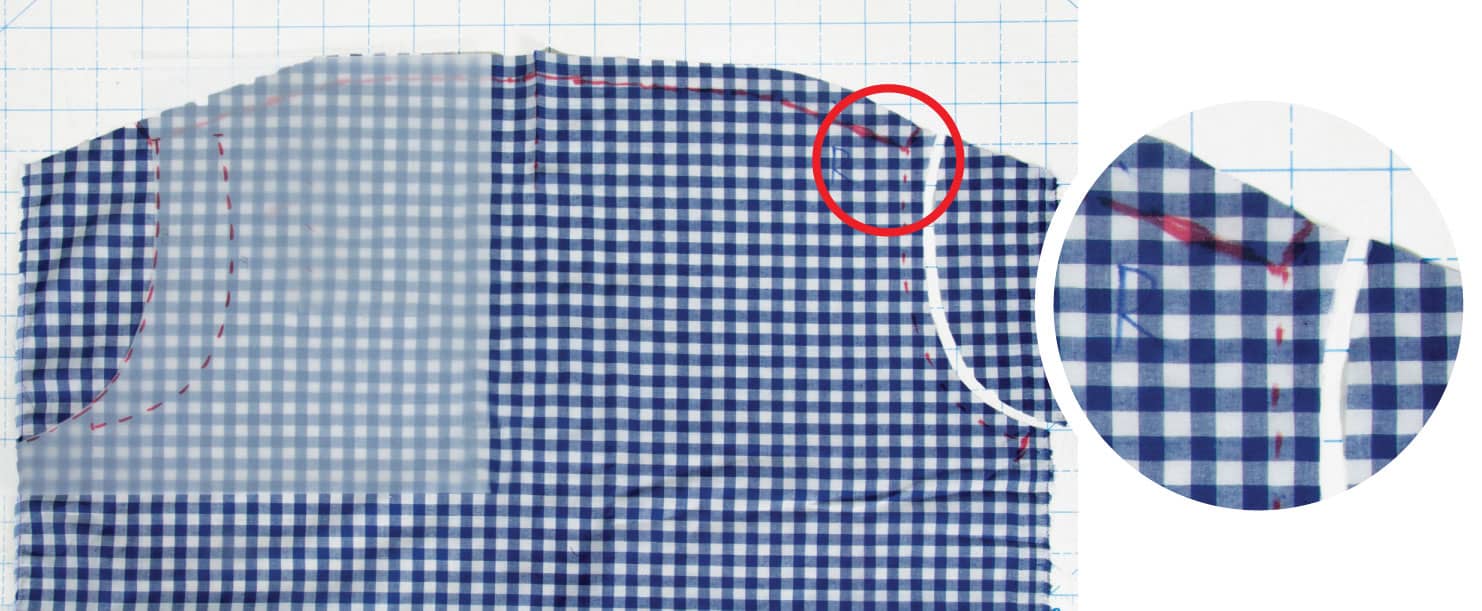

4. Trace the armhole design lines (from the multisize pattern) onto the front and back rectangles at the yoke-end marks and trim, allowing generous seam allowances.

5. Draw side seams straight down from the bottom of each of the armhole markings. Next, baste the rectangles to the yoke as marked and close the side seams, then put the drape back on the form or body to adjust the angle of the side seams and evaluate the general fit.

6. In this example, there’s a side-seam angle problem (because the front rectangle is shorter than the back one). By evenly folding out this excess across the back, we visually balance the front and back, but this also shortens the back armhole. But don’t worry, if the armhole looks okay with the shortened length, as this one does, just leave everything alone or simply choose a different armhole design line or redraw the first armhole design line to return to the back armhole curve to its original length (more on this later).

7. There seems clearly to be more fabric width in back than is needed or looks good, so I pinned it out vertically and then basted along the pin markings to reduce the width. The reduced armhole seemed to look good, so I measured the new length, and found a better-matching sleeve cap length from the multi-size pattern.

The horizontal tuck across the back permanently changes the back pattern and disappears into it, while the vertical ones at the back waist can become darts, or be converted to seams, or even be used to permanently reshape the side seams, as you’ll see later.

8. Next, stitch up a test sleeve and baste it into the armhole curve. In this example, the sleeve is straining against the arm, so it’ll be a good idea to check the real body this form represents.

9. I like to use a paper strip to represent any number of different neckline design lines. This shows a collar on a stand, but many other style lines are as easy to sketch on paper or directly on the fabric with a marker.

So, in just these few steps we’ve draped our way to a complete and fully customized basic shirt muslin. By tracing the marked seams from this to paper, we can easily create a pattern from it (see “Pin- and Wheel-Tracing,” and the additional online material).

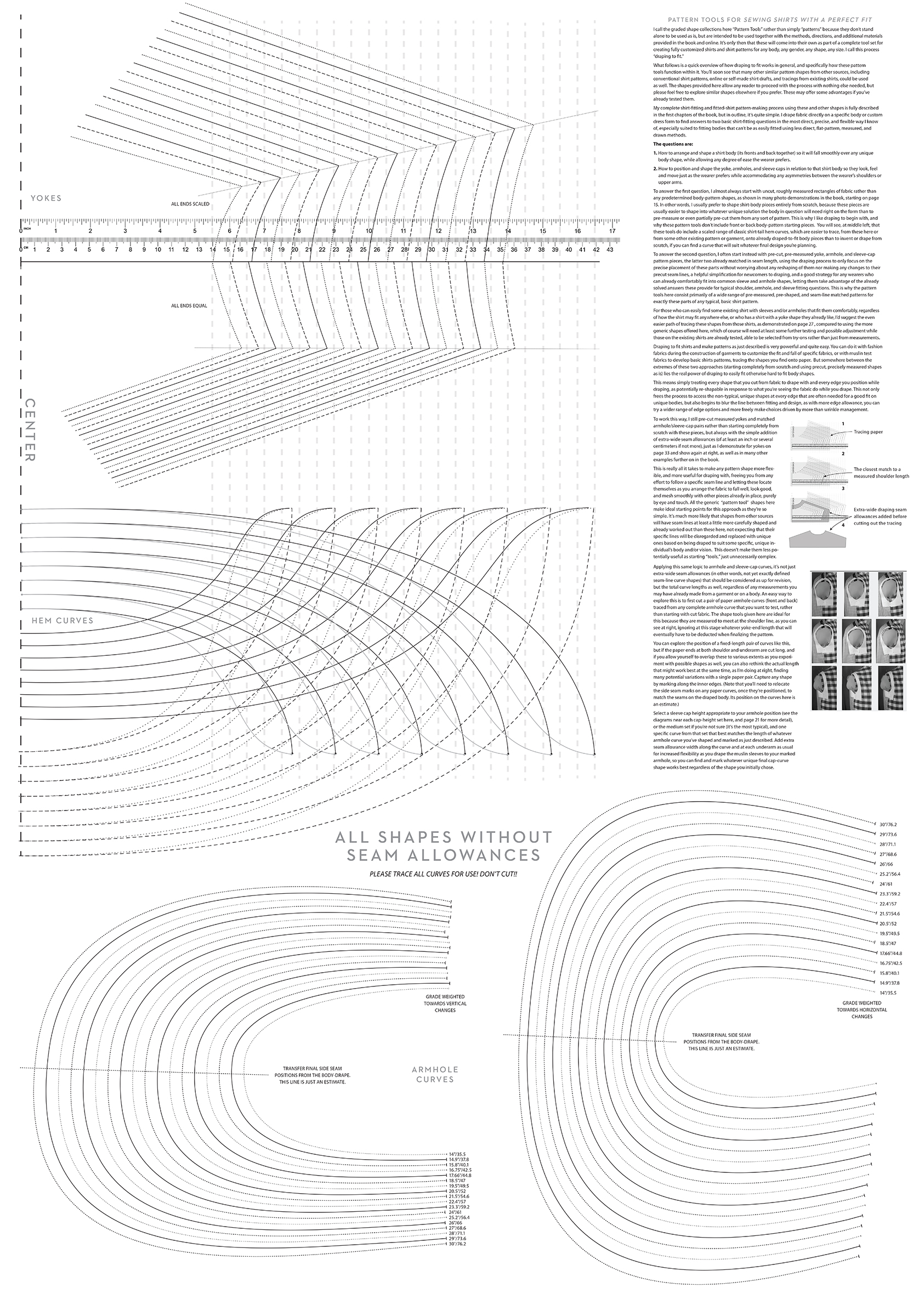

USING THE PROVIDED MULTISIZE PATTERN; WHERE’S THE BODY?

As my nutshell explanation proves, you can create a full test muslin with almost no measuring and no paper-pattern manipulation. And to do this, we needed only three pattern pieces, or more accurately, one piece (a yoke) and three seam line shapes (two armhole curves and one matching sleeve cap). Since these are provided in this book’s full-size pattern collection, shown below (and available for download at www.quartoknows.com/page/sewing-shirts), you’re good to go! And since yokes and curves are also provided in many millions of existing multisized shirt patterns or can be pin-traced from any comfortable shirt already hanging in your own closet, you have many options.

Your first reaction, if you looked at the book’s patterns before now, could well have been, “But where’s the body holding all those bits together?” Hopefully, now you can begin to see why the body isn’t there. For a personalized fit, it’s potentially easier, faster, and more accurate to drape the body pieces into shape than to start with the wrong shapes and to try to fix them.

MEASURE A FAVORITE SHIRT

A good first step when choosing your best three starting pattern shapes is to measure those three shapes on at least one shirt you can wear comfortably in the shoulders and, particularly, in the armholes and sleeves. It doesn’t matter if any other parts or details, like the neckline, body ease, hem or sleeve lengths, aren’t right, or even how well this shirt seems to fit overall. You don’t need to copy the yoke from the same shirt as for the sleeve and armhole lengths. We’re just looking for ballpark starting dimensions for each of these three critical elements, you aren’t committing to, or actually fitting anything at this stage, so there isn’t a right or wrong selection at this point.

Lay the shirt out flat:

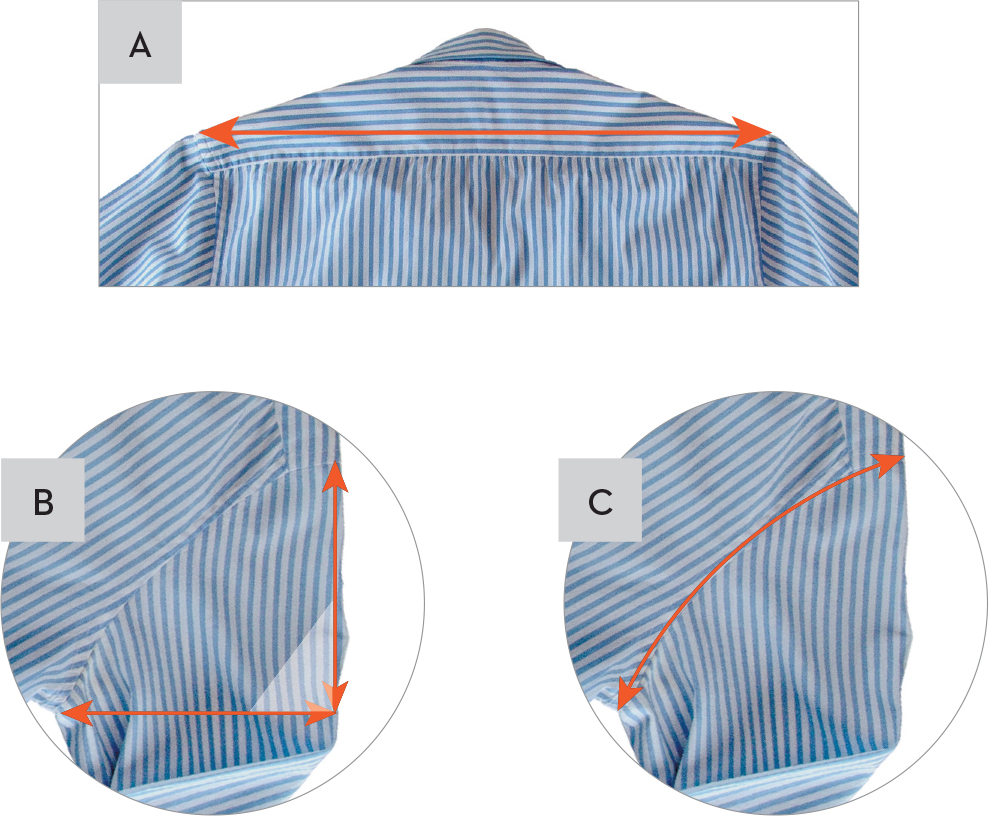

A Measure the yoke across the back about midway between the back/yoke seam and the neckline.

B Lay out one sleeve flat with the underarm seam at one edge. Measure across the sleeve width from the underarm/side seam (bottom of the armhole) to the opposite fold, keeping the measuring tape at 90 degrees to the fold. Pin-mark that spot on the fold, then measure the cap height from the pin mark, along the fold, up to the armhole seam.

C Measure both the front and back armhole seams by holding the measuring tape on edge. Add these two measurements to determine the total length. This measurement also represents the cap length.

You’ll need these measurements at the start of the first how-to-drape chapter, shown here. The sleeves and armholes raise several interesting points on using patterns when draping, so a brief discussion follows.

DRAPING WITH PATTERNS

A pattern for a shirt (or any garment) is a precise collection of flat, fixed-shape pieces with edges that fit together into garments with a known fixed shape. For this to work, each piece in the collection must be carefully matched to every other piece on all the edges.

When draping a shirt to fit, you’ll eventually need the same collection of flat pieces as the pattern provides, but you don’t start out with them. Instead, you begin with a single, not-yet-fixed yoke shape then cut front and back joining pieces and mold all these to the body. Only after this draping process do you discover the custom shape of the actual pattern pieces.

In other words, you don’t yet know the finished shapes of the pattern pieces before you cut them from the test fabric, nor do you know the final shape the garment until you have finished and the shirt fits well. For this to work, you need to proceed in a fixed, logical order (yoke, body, armholes, sleeves), rough-cutting fabric pieces when you are ready to drape the next pattern piece (example: back of shirt to the yoke). This way, any seam or design line adjustments ripple through the process in the same order.

Happily, it is easy to combine both garment-making approaches—flat-pattern making and draping—to join the precision of a pattern to the flexibility of draping. This happens by choosing to precut from an existing pattern some pieces from the collection of needed parts, leaving the rest to be cut roughly for draping/shaping. You can also choose to precut only some edges on any piece, leaving the other edges rough cut for draping. And you can always remold even precision-cut fabric shapes as they appear on the form, in context, and in drape-to-fit order.

Here’s an example: In the nutshell version of my process, (see here) I started with a yoke cut from a specific pattern. I also added a precise pair of armhole curves and a matching sleeve cap, all also traced from a specific pattern, so I’d have fabric versions of my three connected ovals shown here.

My original plan was that the only thing I’d be draping with these precut shapes was the shape of the yoke holding them together. I wouldn’t need to drape the sleeve and armhole shapes, just transfer the design lines for them, unchanged, from my pattern, regardless of how the yoke in between would be shaped, as shown. This draping would be little more than a way to capture the shoulder slope of the form (or body), based on how the yoke molded to it.

But note that the only thing that allows me to actually capture the draped yoke’s shape is the back and front pieces, which I didn’t precut at all. I have to drape those two pieces before I even get to the armholes.

You’ll recall that in the nutshell demonstration (see here) I did wind up changing the back armhole curves to correct the side-seam balance. To stick with my goal of not messing with the pattern-derived armholes or sleeve cap, I would just retrace or redraw each armhole curve, so together they’d regain the original overall length, but, in fact, I saw that a smaller armhole would probably work better. This is a good example of how draping often visually suggests new options worth considering as you progress. It also confirms how critical the order of progress is when draping, so you can be more flexible to making changes. I’d have been wiser to select my sleeve cap after I’d joined and balanced the side seams, and seen their impact on the armholes.

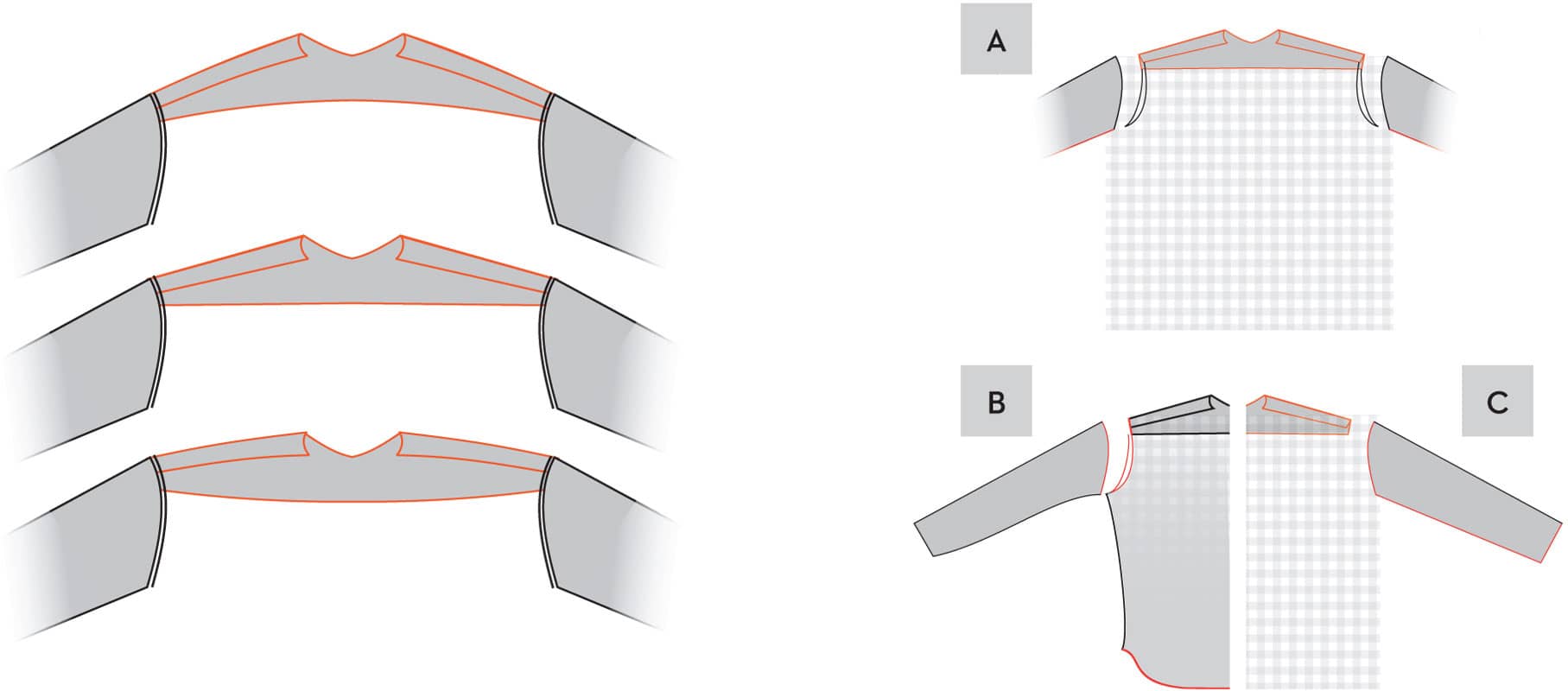

Here are a few more options for distributing the precut and rough-cut edges at the start of a shirt-draping process. In each diagram at right below, the black-outlined edges are the pattern curves I traced from a pattern with regular seam allowances and did not change; the red-outlined edges indicate those that I traced from a pattern but gave deep seam allowances, for maximum flexibility while draping. The gingham-like shapes are those I did not cut with edges from a pattern at all. Note that it’s perfectly okay to combine different methods in a single piece.

Let’s go over the options in detail:

A It’s ideal when you’ve got a pattern or copied garment you like a lot, and you just don’t want to mess with sleeves and armholes, but still want to drape to correct for your shoulder slope, and you’d also maybe like to experiment with the ease and shaping of the side and underarm seams below the armholes.

B This option preserves side and/or underarm shaping from a favorite pattern, favorite shirt, or previous drape, precutting those seams, while leaving both the armholes and sleeve caps cut loose for further adjustments and experimentation. Note that I’ve given the yoke here black outlines, to indicate that I’d retain edge placement to preserve some interesting shaping from a pattern or other inspiration. This won’t interfere with molding the yoke to conform to unique body contours; I just won’t need to refold the ends or edges. Also note that the rough hem edge is required whenever there’s uncertainty about where the front and back upper-body edges will wind up (and there almost always is uncertainty).

C This is my most common approach, the one in which I leave off any armhole or side-seam preshaping in favor of improvising when I get to them. I also cut the sleeve cap and underarm loose so they can be draped into shape.

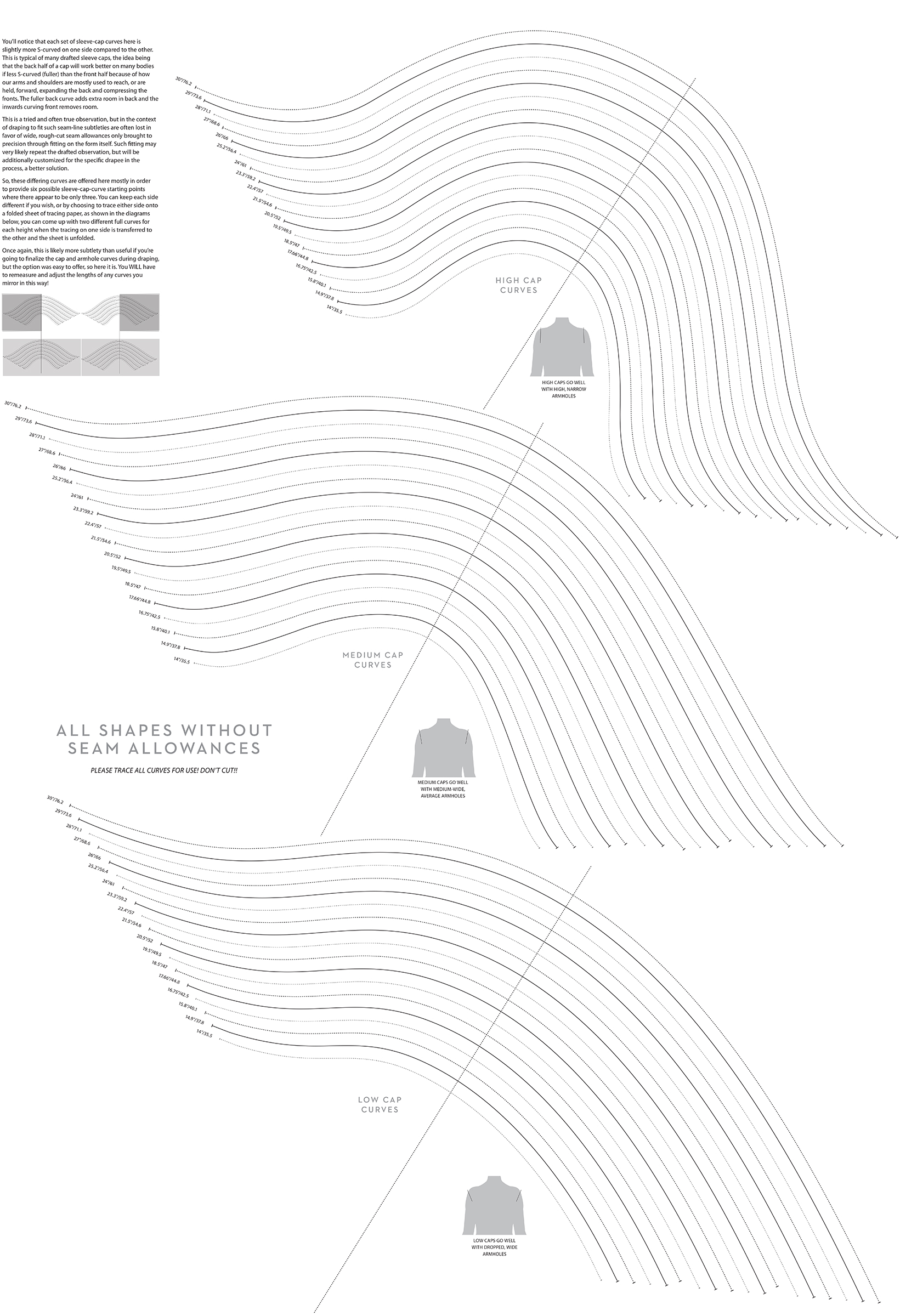

HOW TO USE ARMHOLE AND SLEEVE CAP CURVES

Being able to insert an already well-drafted, already-matched armhole and sleeve-cap shape (taken from a pattern) into a custom draped shirt with no changes needed is definitely a great thing, well worth taking advantage of, and perfect for beginners to the whole draping process. But because it is difficult to predict changes and further adjustments that might be made to the yoke and side seams as you adjust grain, balance, and fitting ease, it’s very likely that a precut armhole will need to be eventually redrawn or retraced.

New armhole curves can be easily marked directly on the still-draped fronts and back, after the side and yoke seams are finalized. This is why my list of required starting shapes for draping has shrunk to include a collection of only yokes and a set of sleeve cap curves.

If you don’t plan to start with an existing sleeve cap and armhole curve (from a pattern or traced from a shirt): mark an armhole on your drape, following the basic shape of the form. Once it appears to look like a well-shaped armhole, measure its total length, and check this against the measurement you took from your favorite shirt (see here). Adjust the shape of the curve, as needed to match the length measurements. Then, select the medium-height sleeve cap with the curve (from the multisize pattern provided or another source) that most closely matches the measurement. Trace the curve on to test fabric (with an inch (2.5 cm) or more of seam allowance at the cap) and stitch a sample sleeve with a softly tapered straight underarm seam, approximately 12" (30 cm) long. Pin the sample sleeve to the armhole, starting at the top—with the seam allowances pinned over the marked curve lines or fold the seam allowances to the wrong side and then pin the seamlines together.

With this very basic, and most typical, test sleeve, you’ll be able to drape a lot of sleeve style variations. This is exactly what you’ll see I’ve done throughout the following pages; I simply used the same red and white plaid sample sleeves over and over.

Here’s the interesting part: These same sleeves also worked fine even if I had to adjust the width at the underarms to get them to baste nicely into the often quite different armhole curves. This confirms the two most basic truths I know regarding shirt sleeves:

1. Any sleeve cap shape can be fitted to any armhole as long the lengths of the seams (sleeve cap and armhole opening) match.

2. Any sleeve you specifically drape or adjust to look or feel good on you (or any fittee) is as good, if not better, than any predrafted one.

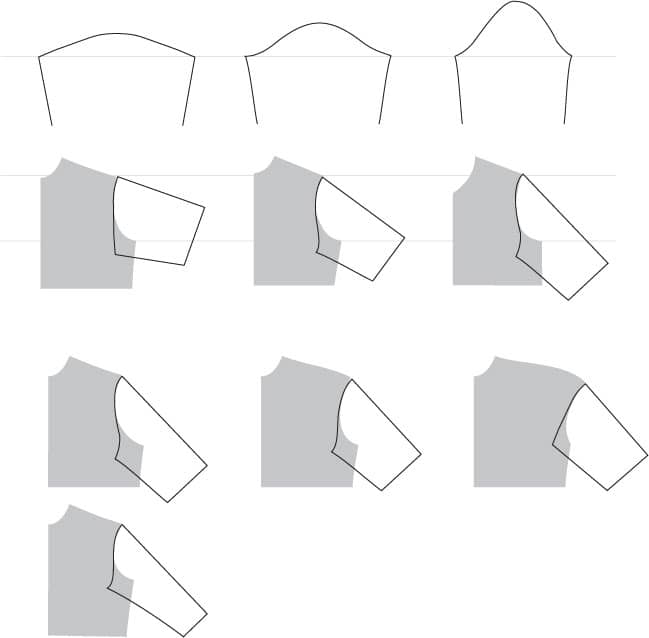

WORKING WITH CAP HEIGHT

The top three pairs of diagrams, below, illustrate one logic behind having a choice of sleeve-cap shapes such as I’ve provided on the book’s pattern sheet: The taller the cap, the steeper the sleeve angle, and the narrower the sleeve tube, if all else is equal. The steeper the sleeve angle when worn, the less excess fabric there will be to bunch up at the underarm when the arms are down, and the more strain there will be on the garment when the arms are raised. Thus, working or sport shirts tend to have shallow caps and dressier shirts taller ones. So, you can choose any cap you want without changing the armhole you’re comfortable with to get different sleeve angles. But only you can decide which you’ll like best once you’re wearing it.

However, there are factors other than sleeve angle to consider. The trio of diagrams, below, shows how the amount by which your armhole extends beyond your shoulder point is an equally useful determining factor for cap-height selection and has an equal impact on sleeve angle as well. The final illustration shows how a tall cap decreases in height if you make the sleeve tighter. Because the armhole is raised at the bottom to preserve the range of motion, bringing the sleeve’s underarm seams up at the same time, reduces the cap height.

Fortunately, we’re draping, not drafting our sleeves, so we can simply refine all these factors by adjusting the sample sleeve right on the form or body, finding the unique cap shape and height that will in fact work best regardless of whatever shape or curve is precut.

Ease around the arms at any point below the cap is controlled by shaping the underarm seam lines, which certainly don’t have to be straight, and rarely are on modern shirts. The illustration shows a variety of interesting underarm curves, pulled from a collection of sleeve patterns.

But because it’s very hard to find or make an accurate arm form, or to effectively evaluate any sleeve without actually trying it on and moving in it, fitting a sleeve is best done by pinning it onto the body drape and then slipping the test drape on to the actual body.

CAN I DRAPE PLUSSIZES AND WEIGHTLIFTERS, TOO?

One of the great features of this draping process is that it’s completely shape neutral. It’s about the ability to respond to the basic facts of gravity working on fabric when it is placed on a torso form or a body, any body—any shape. So, the main draping limitations you’re likely to encounter are your own preconceptions about what looks good. And you can be sure that there’s nothing about any particular body shape that would make draping a less intuitive or appropriate technique for fitting it. Just the opposite, I’d suggest!

The same goes for the body-wrapping technique I introduce shown here. There’s no method I know of that’s as fast a path to either (or both) a highly detailed and accurate dress-form cover or an equally accurate basic body-shaped flat pattern, both of which I’ve found to be essential tools for working with unique body shapes.

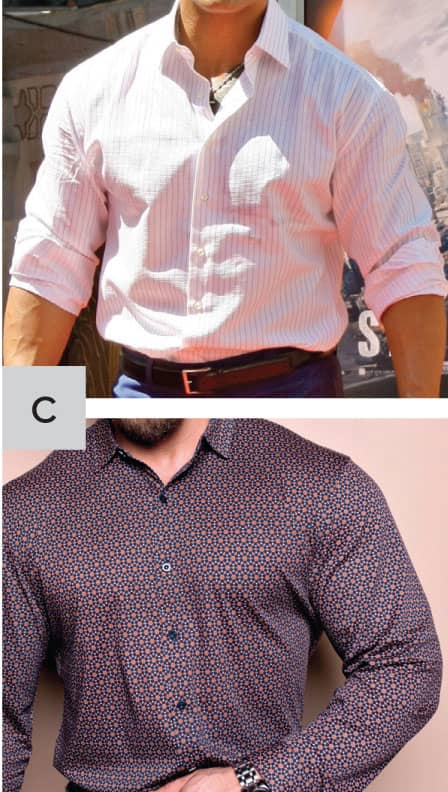

The images, below, well demonstrate a few facts about bodies, fit, and fabric that all fitters will benefit from considering.

A This shows how an adult body can only grow or shrink in width, not height, unlike how most pattern-size grading operates, which is to always add or remove height. Hopefully, you can now begin to imagine how easily sleeve draping could capture the unique upper-arm curves on each body shown.

B These photos confirm that the more a closely a garment is fitted in one position, the more poorly it fits when we take another position.

B and C Different fabrics have different effects. Crisp fabrics better conceal body shapes than softer fabrics, but wrinkle more dramatically in response to body movement.

WRINKLE BASICS

There are two kinds of garment-fitting wrinkles, excess length wrinkles and strain wrinkles. The body, below, is too short for the blue shirt where the horizontal wrinkles appear, and it’s too long for it where the vertical ones appear (so these wrinkles could just as well be called insufficient-length wrinkles). In this case, these conditions are probably temporary, simply caused by body movement, like most wrinkles in shirts. But also note that the body in the striped shirt is moving much more dramatically, yet relatively few wrinkles appear. This is simply because the fabric (possibly a knit) is stretched tight on it. There’s neither excess nor insufficient length to allow wrinkling in the sleeve, no matter how the wearer moves. But her reaching movement is temporarily reducing her body length in back, causing an excess length in the fabric and, thus, wrinkles just above her belt. By the way, notice how few wrinkles appear in the interesting vintage shirts she’s hanging on the line, and imagine how easy it would be to more carefully pin each one to drape even more wrinkle-free from the line.

WRINKLE REMOVAL

Instead of pinning shirts to fall smoothly from a clothes line, consider the possibilities of pinning (draping) a single piece of fabric to a flat vertical surface, supporting it only from the top, as most simple garments are supported on bodies. In other words, let’s look briefly at wrinkles in two-dimensions, without the 3D complexities of a body involved.

To arrange two-dimensional folds or wrinkles in some attractive, appealing way we have a lot of options, but little objective guidance, just our own opinions about what’s attractive to direct our draping.

But there are two possible and obvious moves: Compress the outer top edges of the fabric in towards each other to create some specific amount of excess fabric to begin with, and then lift selected points along the top edge to divide and distribute the excess fabric. Lifting just the right amount, and in the right location, may take some trial and error, but worthwhile to explore interesting ways to distribute the excess fabric.

To remove or reduce the folds we essentially have the same options: Stretch or smooth the upper edge so there’s little or no excess length to fall into folds to begin with, then lift and pin the upper edge wherever it’s drooping.

Removing folds or wrinkles is obviously easier than adding them. You see right way when the excess folds of fabric are gone, and whether you aligned the upper edge to be level, and if you put in enough well-positioned pins to keep any part of the upper edge from flopping over—no instructions needed, just paying attention and taking some care.

In short, no matter what draped or smoothed effects we explore, all we are doing is choosing points along the upper edge from which to let gravity arrange the fall of the fabric below. When choosing a smooth look, we have a clear limit (the width of the fabric) to work towards, while choosing to create drapey folds opens a host of possibilities.

You might be thinking that adding folds is like design, and removing them is like fitting, and I’d agree, while insisting that both adding and removing folds could as reasonably be considered both fitting or design. Either way, removing folds/wrinkles is the essence of the basic draping we’ll be doing with the main, large, rectangular pieces of fabric (fronts, backs) as we fit, that is: Smooth and Lift—it’s that simple. We’ll have real body shapes underneath to make the process seem more complex and the range of possible wrinkles more challenging, but our possible moves will remain the same. Smooth and lift.

When we add another large fabric piece to the project and attempt to join it to the first (like the shirt back to the shirt front or vice versa), in either two- or three-dimensions, we introduce the issue of how to join two pieces without spoiling the smooth, wrinkle-free drape of the first piece. We must first bring them together, or cut their joining edges, so there’s sufficient length to begin with, then smooth and lift one or both pieces in relation to the other so there’s no strain or ill-placed lifting introduced on either side. So, with more fabric pieces there are more edges to handle, but our possible moves remain pretty much the same—smooth and lift. Now we just have to balance these moves between multiple pieces: Smooth and lift, then balance. Repeat.

The bottom line: Whenever you’re draping to fit, and maybe feel stuck, just ask: “Where can I smooth, lift, or balance here?” And as you view all the draping demonstrations that follow, that’s basically all you’ll see me doing.

PIN- AND WHEEL-TRACING

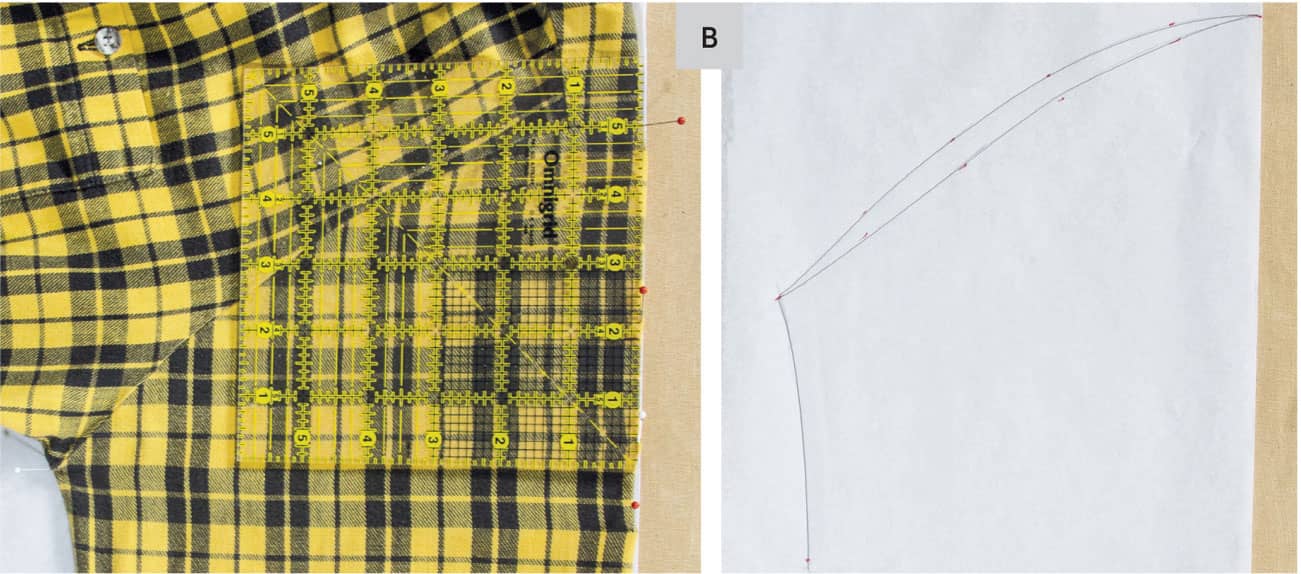

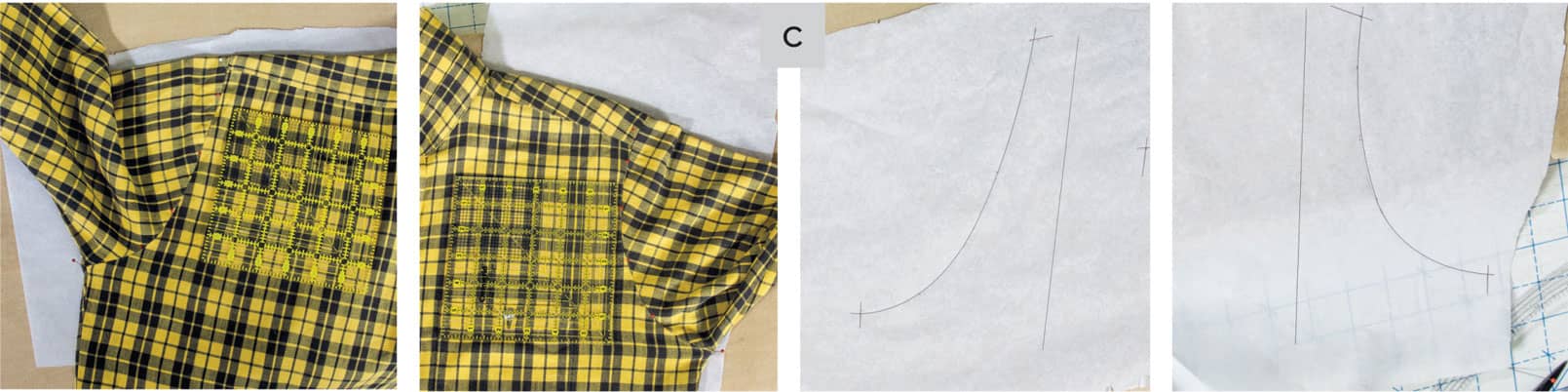

An essential fitting and pattern-making skill is the accurate transfer of marked, seamed, or cut fabric onto paper to create patterns. Wheel-tracing is how I transfer markings from draped fabric, like the marked lines on the blue gingham shown here. Pin-tracing, as shown on the yellow plaid shirt, is my process for transferring pattern shapes from existing garments onto paper.

In either case, I depend on large sheets of plain paper and an equally large soft, pinnable surface, because each process involves fabric laid smooth over the paper and the seams or markings traced by poking pins or wheel-teeth through all the layers into something soft underneath them all. A roll of pattern tissue and an ironing board serves well for small shapes, but for full-garment pattern-making my main supplies are a pad of plain flip-chart paper (easily stored with no curling from being rolled) and a sheet or two of foam core sufficient to fit under the full size of the top paper. For pin-tracing, I like to hold a heavy sewing-machine needle in a pin vise; and any sort of toothed tracing wheel will work for wheel tracing.

It’s easy to trace the yoke, sleeve cap, and armholes from an existing shirt for future draping into a custom pattern—and please note, once again, that these are the only parts of any shirt or pattern you need for this. The critical thing in every case is to confirm that the grain is straight and square on each garment part being traced before you begin. Plaid fabrics are obviously helpful for this, as are gridded quilting reference rulers, as are used in the sleeve and armhole photos at lower right.

To capture the full yoke width and shape (A) and the sleeve cap shape (B), align the folded centers of these pieces with a centered fold of a piece of paper as shown; pin to secure the layers, then trace exactly along all the seam lines by poking the pin or needle through the paper below.

Note the nonsymmetrical curves (between the front of the shirt and the back) often found on full sleeve cap seams (B); to accurately trace them, you need to feel through the layers to locate the hidden one, and pin trace that seam too. Each paper unfolds to reveal the full pattern, of course. You’ll need a front and back armhole, so label these carefully (C), and it’s a good idea to include a reference vertical grain line near each curve for easy alignment with centerfronts and centerback when transferring these to the draped front and back rectangles. But note: This amount of precision precut shaping is rarely needed or preserved when draping; it’s replaced with customized curves revealed when the draped test sleeve is transferred to paper.

To capture a full pattern from an existing shirt, see the links to my website at dirtk.

MEET THE FORM FAMILY

Initially, I hoped this book would feature lots of real-world bodies photographed in varying stages of draped projects, but it’s even more difficult to find fitting process-shot volunteers than it is for custom clothiers to find customers who like long fitting sessions. I required, not just willing fit-volunteers, but volunteers with classic fitting issues and body asymmetry. Eventually, I accepted the reality that the best way to study fitting—especially fitting by draping—is to have your own customized dress form. Fitting buddies are great, but are usually nowhere to be found at 1 AM!

In lieu of willing fit volunteers, I created four torso forms, each one heavily customized so, together, they display as wide and as likely an assortment of common shoulder and other postural variations as I found possible. Two are based on real bodies and two are fictional bodies with plausible fit problems (based on much people watching, especially via the television; bless that pause button).

I’ve detailed just how I built each form at my blog—each quite different—and describe in some detail exactly how you can leverage part of my tight-fitting shirt process into a dress-form project as well (see here). Please ignore any seams or pinned tapes that are visible on the forms themselves. These are not guidelines for draping, as they might be on commercial forms. They’re just random artifacts of making them easier to use.

The forms I use throughout the book are shown here, each with a short list of distinguishing shapes and characteristics. But as you’ll learn, the drape-to-fit process doesn’t require any such preliminary assessment because the process is not problem or shape specific. It simply responds, with equal effectiveness, to bodies of any size or shape.

#1, REAL MALE BODY (ME)

• Slouched posture

• Rounded, protruding upper back

• Sloped, uneven shoulders

• Forward hips

• Same circumference from hips up

#2, REAL FEMALE BODY

• Plus-size

• Straight posture

• Somewhat rounded, protruding upper back

• Not very sloped, even shoulders

• Full, protruding chest

• Largest circumference at hips

#3, FICTIONAL FEMALE BODY

• Erect posture

• Flat upper back

• Somewhat sloped, rounded, even shoulders

• Full, protruding chest

• About the same circumference from hips up

#4, FICTIONAL MALE BODY

• Athletic body

• Erect posture

• Very wide flat back

• Sloped, wide, deep, even shoulders

• Gradually protruding chest

• Less waist circumference than at chest

DRAPING ESSENTIALS YOU NEED TO KNOW

FABRIC-SMOOTHING REALITIES

While fitting loose garments traditionally is much less of a challenge than fitting tight ones, it’s easier to drape tightly than loosely, and easier to remove ease than to add it. This is another way of saying that smoothing away wrinkles is easier than creating them in the first place.

It’s generally true that diagonal or horizontal garment wrinkles are almost always indicators of poor fit, while vertical wrinkles, especially at the sides, can often be attractive, as well as helpful for easy arm movement; this sort of visible ease is in fact often called “drape.” But to create drape like this is not as easy to do when draping to create a snug, smooth fit. I’ll address this in the demonstrations to follow.

Similarly, convex shapes are easier to drape (and fit) than concave ones, so bodies with few concavities are generally easier to drape. You can allow enough extra length for the fabric to fall into a concave space, but how do you keep it there if gravity isn’t helping (as it definitely does on yokes, for example, which are more or less held in place by the weight of the body and sleeve fabrics)? Stretching fabric over and across concavities, which might occur between the center front and a forward shoulder on a stooped figure (one of my own issues), is an option to explore if the garment fabric is soft and heavy.

ASYMMETRY

Draping, by nature, is great at capturing unique body shapes, so it has no problem with asymmetry. In fact, it has more trouble with symmetry! It’s up to the draper to ensure symmetry, because draping on its own won’t; it will automatically capture asymmetry if it’s there, and if it isn’t, it’s still hard to ensure you’re draping perfectly identical sides. This is why draping for commercial, noncustom work is typically done on only half the form. The draped results are simply mirrored to create a full garment or pattern, which can be cut on a fabric fold or double layer. Custom fit, particularly when there are asymmetric issues, requires a full-body drape.

While almost all bodies are somewhat asymmetrical, many can be fitted perfectly well with symmetrical garments, which are a lot faster to cut than asymmetrical ones. So, it’s up to you to decide whether it’s worth your time and effort to correct the fit of asymmetrical pattern pieces from a full garment drape or to test the full drape and then decide which side fits best and simply mirror that side. This may well be different, depending on the garment and/or the fabric you are draping, since looser garments are more forgiving about matching the body exactly than tighter ones.

For the same reasons, draping isn’t easy to do exactly the same way more than once, so you’ll likely notice that a re-drape on the same body with the same starting shapes and the same test fabrics could easily turn out slightly differently each time, but in each case, fit just as well.

THE FABRIC REALLY MATTERS! AND YOU’LL NEED PLENTY…

Depending as it does so thoroughly on the flexibility of fabric, draping is most definitely a process for which different fabrics can make a huge difference in your results, to the extent, for example, of eliminating or requiring darts that other fabrics did or didn’t require. As you’ll see in the project chapters, I’ve often re-draped a previously draped basic muslin in a fabric more like one I want to use for a specific planned garment, just to be sure the same adjustments will work in the fashion fabric. I also, now that I know better, simply cut out the fashion fabric for each new shirt project with plenty of draping allowance, ensuring that I’ve got wiggle room when the drapability of the fashion fabric doesn’t fully replicate the draping fabric; keeping in mind that initial basic draping results for any particular project, even if very close, are typically still approximate starting points.

Clearly, all this draping means you’re going to have to increase your available stash of test fabrics! You’ll have noticed my preference for woven (as opposed to printed) plaids and ginghams, because their contrasting, crossing yarns provide essential grain information. I use unwashed lightweight, polyester-blend ginghams as my default crisp-fabric, drape-to-fit, full-body “muslins,” and usually only use traditional beige or solid-color muslin fabrics for smaller detail and design experiments for which grain is just as critical but doesn’t need to be as constantly visible or potentially distracting. I collect these fabrics in various weights and crispness and I don’t prewash any of them. Lightweight cotton flannel plaids are excellent for soft-fabric draping, and plaid or checked medium-weight woolens are great for outerwear draping. And I regularly re-sort my main fabric stash to further separate the test fabrics from the garment fabrics; it’s a great way to feel better about all those impulse buys that have lost their allure.

CONVERTING DRAPES TO PATTERNS

Assuming your goal is to have a precise paper pattern when you’re done, draping is, of course, only the start of the process. You’ll next need to use something like the tracing tools described in “Pin- and Wheel-Tracing,” to transfer and record the marked seamlines from your test-fabric drape onto paper. These tracings will then need further refinement to become patterns you can cut use, truing all the lines to match where they join and blending them smoothly where they cross. This is a very well-documented process, so I’ll refer you to the Resources for more information along with the online material.

What I didn’t expect before I started experimenting with draping-to-fit, is how much it would change the way I use paper shirt patterns altogether. I now cut all fashion fabrics with generous draping allowances at all side, armhole, and shoulder seams, knowing that I’ll find the exact stitching lines for these seams, not from the pattern, but by draping them afresh for each new project and in the chosen fabric. You’ll find specific examples of exactly how I do this in the project chapters, and you’ll find that it can vary considerably, depending on the details and fabrics involved. In general, my every shirt project now starts with a drape, to establish how much ease I want for the basic silhouette, around which I then arrange seamlines and allowances for whatever details I want to add, some of which, such as hems, can only be generously approximated. So, for me, draping is no longer simply a fitting and pattern-making first step. It’s become an integral part of the construction process, allowing me to better respond to individual fabrics and unique details as I craft them together, not constrained by precisely precut pieces.

QUICK OR SLOW?

Personally, this drape-to-fit process fits my tendency to work slowly and cautiously, being more concerned with flexibility than efficiency; in fact, I admit it has actually slowed me down, with a clear benefit to my results. Plus, as I worked through all the examples shown in this book, I’ve definitely erred on the side of multiple repeat test drapes, for the sake of my own doubled certainty. But rest assured, draping to fit can just as easily offer a very quick path to truly customized patterns especially if you don’t want or plan to re-drape every time. The choice is yours, and there are plenty of options between the two extremes.