One of the myths of modernity is that it constitutes a radical break with the past. The break is supposedly of such an order as to make it possible to see the world as a tabula rasa, upon which the new can be inscribed without reference to the past—or, if the past gets in the way, through its obliteration. Modernity is, therefore, always about “creative destruction,” be it of the gentle and democratic, or the revolutionary, traumatic, and authoritarian kind. It is often difficult to decide if the radical break is in the style of doing or representing things in different arenas such as literature and the arts, urban planning and industrial organization, politics, lifestyle, or whatever, or whether shifts in all such arenas cluster in some crucially important places and times from whence the aggregate forces of modernity diffuse outward to engulf the rest of the world. The myth of modernity tends toward the latter interpretation (particularly through its cognate terms of modernization and development) although, when pushed, most of its advocates are usually willing to concede uneven developments that generate quite a bit of confusion in the specifics.

I call this idea of modernity a myth because the notion of a radical break has a certain persuasive and pervasive power in the face of abundant evidence that it does not, and cannot, possibly occur. The alternative theory of modernization (rather than modernity), due initially to Saint-Simon and very much taken to heart by Marx, is that no social order can achieve changes that are not already latent within its existing condition. Strange, is it not, that two thinkers who occupy a prominent place within the pantheon of modernist thought should so explicitly deny the possibility of any radical break at the same time that they insisted upon the importance of revolutionary change? Where opinion does converge, however, is around the centrality of “creative destruction.” You cannot make an omelet without breaking eggs, the old adage goes, and it is impossible to create new social configurations without in some way superseding or even obliterating the old. So if modernity exists as a meaningful term, it signals some decisive moments of creative destruction.

Figure 1 Ernest Meissonier’s painting of the barricade on the Rue de la Mortellerie in June 1848 depicts the death and destruction that stymied a revolutionary movement to reconstruct the body politic of Paris along more utopian socialist lines.

Something very dramatic happened in Europe in general, and in Paris in particular, in 1848. The argument for some radical break in Parisian political economy, life, and culture around that date is, on the surface at least, entirely plausible. Before, there was an urban vision that at best could only tinker with the problems of a medieval urban infrastructure; then came Haussmann, who bludgeoned the city into modernity. Before, there were the classicists, like Ingres and David, and the colorists, like Delacroix; and after, there were Courbet’s realism and Manet’s impressionism. Before, there were the Romantic poets and novelists (Lamartine, Hugo, Musset, and George Sand); and after came the taut, sparse, and fine-honed prose and poetry of Flaubert and Baudelaire. Before, there were dispersed manufacturing industries organized along artisanal lines; much of that then gave way to machinery and modern industry. Before, there were small stores along narrow, winding streets or in the arcades; and after came the vast sprawling department stores that spilled out onto the boulevards. Before, there was utopianism and romanticism; and after there was hard-headed managerialism and scientific socialism. Before, water carrier was a major occupation; but by 1870 it had almost disappeared as piped water became available. In all of these respects—and more—1848 seemed to be a decisive moment in which much that was new crystallized out of the old.

Figure 2 Daumier’s L’Emeute (The Riot), from 1848, captures something of the macabre, carnivalesque qualities of the uprising of February 1848. It seems to presage, with grim foreboding, the deathly outcome.

So what, exactly, happened in 1848 in Paris? There was hunger, unemployment, misery, and discontent throughout the land, and much of it converged on Paris as people flooded into the city in search of sustenance. There were republicans and socialists determined to confront the monarchy and at least reform it so that it lived up to its initial democratic promise. If that did not happen, there were always those who thought the time ripe for revolution. That situation had, however, existed for years. The strikes, street demonstrations, and conspiratorial uprisings of the 1840s had been contained and few, judging by their unprepared state, seemed to think it would be different this time.

On February 23, 1848, on the Boulevard des Capucines, a relatively small demonstration at the Foreign Ministry got out of hand and troops fired at the demonstrators, killing fifty or so. What followed was extraordinary. A cart with several bodies of those killed was taken by torchlight around the city. The legendary account, given by Daniel Stern and taken up by Flaubert in Sentimental Education, focuses on the body of a woman (and I say it is legendary because the driver of the cart testified that there was no woman aboard).1 Before largely silent crowds gathered in the streets, according to Stern’s account, a boy would periodically illuminate the body of the young woman with his torch; at other moments a man would pick up the body and hold it up to the crowd. This was a potent symbol. Liberty had long been imagined as a woman, and now it seemed she had been shot down. The night that followed was, by several accounts, eerily quiet. Even the marketplaces were so. Come dawn, the tocsins sounded throughout the city. This was the call to revolution. Workers, students, disaffected bourgeois, small property owners came together in the streets. Many in the National Guard joined them, and much of the army soon lost the will to fight.

Figure 3 Daumier hilariously reconstructs the moment when the street urchins of Paris could momentarily occupy the throne of France, while joyously racing around the abandoned Tuileries Palace. The throne was subsequently dragged to the Bastille and burned.

Louis Philippe hastily appointed first Louis Molé and then Adolphe Thiers as prime minister. Thiers, author of voluminous histories of the French Revolution, had held that position earlier in the July Monarchy (1830) but had failed to stabilize the regime as a constitutional monarchy along British lines. Thiers is thought to have advised the King to withdraw to Versailles and marshal forces loyal to himself—and, if necessary, to crush the revolutionary movement in Paris (a tactic later deployed against the Paris Commune of 1871). The aged and demoralized King, if he heard, did not listen. He abdicated in favor of his eight-year-old grandson, leaped into a coach, and fled to England with the Queen, disguised as Mr. and Mrs. Smith. By then the city was in the hands of revolutionaries. Conservative deputies fled, and a brief attempt to set up a regency for the new King in the National Assembly was brushed aside. Across town, a provisional government was declared at the Hotel de Ville. A group of eleven, including Lamartine, a Romantic poet with republican and socialist sympathies, and Louis Blanc (a longtime socialist) were acclaimed to head a provisional government. The population invaded the Tuileries, the King’s erstwhile residence, and sacked it, destroying furnishings and slashing paintings. Common people, even street urchins, took turns sitting on the throne before it was dragged through the streets to be burned at the Bastille.

Many people witnessed these events. Balzac, although anxious to get on his way to Russia to be with his beloved Madame Hanska, could not resist a trip to the Tuileries to see for himself. Flaubert rushed to Paris to see events at first hand “from an artistic point of view,” and wrote a lengthy, informative, and, some historians accept, accurate version of it into Sentimental Education twenty years later. Baudelaire was swept up in the action. But Georges-Eugène Haussmann, then subprefect at Blaye, near Bordeaux, and later the mastermind behind the transformation of Paris, was, like many others in provincial France, surprised and dismayed when he heard the news two days later. He resigned, and refused reappointment by a government he considered illegitimate.

The provisional government held elections in late April, and the Constituent Assembly met in May to officially proclaim the Republic. Much of provincial France voted right, much of Paris voted left, and some notable socialists got elected. More important, spaces were created in which radical organizations could flourish. Political clubs formed, worker associations sprang up, and those who had been most concerned about the question of work procured an official commission that met regularly in the Luxembourg Palace to look into social and political reform. This became known as “the workers’ parliament.” National workshops were created to offer work and wages to the unemployed. It was a moment of intense liberty of discussion. Flaubert brilliantly represented it thus in Sentimental Education:

As business was in abeyance, anxiety and a desire to stroll about brought everybody out of doors. The informality of dress masked the differences of social rank, hatreds were hidden, hopes took wing, the crowd was full of good will. Faces shone with the pride of rights won. There was a carnival gaiety, a bivouac feeling; there could be nothing such fun as the aspect of Paris on those first days.…

[Frédéric and the Marshal] visited all, or almost all, of [the clubs], the red and the blue, the frenetic and the severe, the puritanical and the bohemian, the mystical and the boozy, the ones that insisted on death to all kings and those that criticised the sharp practice of grocers; and everywhere tenants cursed landlords, those in overalls attacked those in fine clothes, and the rich plotted against the poor. Some, as former martyrs at the hands of the police, wanted compensation, others begged for money to develop their inventions or else it was a matter of Phalanstèrian (Fourièrist) plans, projects for local markets, systems to promote public well-being, and then there would be a flash of intelligence amid these clouds of foolishness, sudden spatters of exhortation, rights declared with an oath, flowers of eloquence on the lips of some apprentice lad wearing his sword sash next to the skin of his shirtless chest.… To appear reasonable it was necessary always to speak scathingly of lawyers and to make use of the following expressions as frequently as possible: every man must contribute his stone to the edifice … social problems … workshops.2

But the economy went from bad to worse. Debts remained unpaid, and bourgeois fears for their property rights as owners, rentiers, and employers fueled sentiments of reaction. (“Property was raised to the level of Religion and became indistinguishable from God,” wrote Flaubert.) Minor agitations in April and May deepened the fears, and the last of these ended with several radical leaders under arrest. Retribution against the left was in the making. The national workshops were failing to organize productive work but kept workers from returning to their earlier employments. The republican government, with the right wing in a clear majority, closed them down in June. Significant elements within the populace rose up in protest. In Guedella’s classic description: “The men were starving, and they fought without hope, without leaders, without cheers, shooting sullenly behind great barricades of stone. For four days Paris was alight with the dull glow; guns were brought up against the barricades; a great storm broke over the smoking town; women were shot without pity, and on a ghastly Sunday a general in parlay with the barricades was shamefully murdered; the Archbishop of Paris, with a supreme gesture of reconciliation, went out at sunset to make peace and was shot and died. It was a time of horror, and for four summer days Paris was tortured by the struggle. Then the rebellion broke, and the Republic survived.”3 The National Assembly had dismissed the government (Lamartine among others) and placed its faith in Louis Cavaignac, a bourgeois republican general with much experience in colonial Algeria. Given command of the army, he ruthlessly and brutally put down the revolt. The barricades were smashed.

Figure 4 This rare and extraordinary daguerrotype of the barricades on the Faubourg du Temple on the morning of June 25, 1848, illustrates what the forces of order were up against as they sought to reoccupy Paris.

The June Days did not put an end to matters. Centrist republicans were now discredited, and the National Assembly was increasingly divided between a monarchist right and a democratic socialist left. In between there arose the specter of Bonapartism in the guise of the nephew, Louis Napoleon. Still officially exiled in England, he had been elected to a seat in the Assembly in June. He refrained from trying to take his seat but indicated ominously in a letter that “if France called him to duty he would know how to fulfill it.” The perception began to take hold that he, and only he, could reestablish order. He was reelected in another election in September. This time he took his seat. With the new constitution creating a President on the American model, to be elected by universal suffrage, Louis set about campaigning for that position. In the election of December 10 he received 5.4 million votes against 1.4 million for Cavaignac and a derisory 8,000 for Lamartine. But the presidency was limited to four years and Louis did not command much support in the Assembly (only a smattering of Bonapartists were elected in 1849; the majority was conservative royalist). Louis began to display a capacity to keep law and order and suppress “the reds” while showing scant respect for the constitution.

Most of the socialist leaders (Louis Blanc, Alexandre Ledru-Rolin, Victor Considérant, etc.) had been driven into exile by the summer of 1849. Cultivating popular support particularly in the provinces (with the covert help of officials like Haussmann), and even more importantly among Catholics (by helping to put the Pope back into the Vatican against the revolutionaries in Italy) and within the army, Louis Napoleon plotted his way (with the unwitting help of the Assembly that foolishly abolished universal suffrage, reinstituted press censorship, and refused to extend the presidential term) to the coup d’état of December 2, 1851. The Assembly was dissolved, the main parliamentary figures (Cavaignac, Thiers, etc.) were arrested, the sporadic resistance was easily put down in Paris (though the death of a democratic-socialist representative, Baudin, on one of the few barricades was later to become a symbol of the illegitimacy of Empire). In spite of some surprising pockets of intense rural resistance, the new constitution (modeled on that of Year VIII of the Revolution) was confirmed by a huge majority of 7.5 million votes against 640,000 in the plebiscite of December 20. Louis Napoleon, to cries of “Vive l’empereur,” rode triumphantly around the city for several hours before entering and taking up residence in the Tuileries Palace. It took a year of further cultivation of popular support for the empire to be declared (and again confirmed by a massive majority in a plebiscite). Republicanism and democratic governance had been tried, and had failed. Authoritarianism and despotism (though whether benevolent or not had yet to be determined) constituted the answer.4

Haussmann, with clear Bonapartist sympathies, resumed his prefectural role in January 1849, first in Var and then in Auxerre. Invited to Paris to receive a new assignment, he just happened to be at a soirée at the Elysée Paris on the evening of December 1, 1851. Louis Napoleon shook his hand, informed him of his proposed new appointment, and asked him to present himself early in the morning to the minister of the interior to receive his instructions. That evening Haussman discovered that the existing minister had no idea what he was talking about. At 5 o’clock the next morning Haussmann presented himself and found the Duke of Morny, half brother of Louis Napoleon, now in charge. The coup d’état was in process and Morny correctly presumed that Haussmann was with them. Haussmann was reassigned first to the frontier region with Italy (a delicate problem because of border difficulties) but then to his favored region of Bordeaux. And as the Prince-President toured the country in preparation for the declaration of Empire, he culminated with a major speech at Bordeaux (“The Empire is Peace,” he proclaimed) in October 1852. Haussmann’s ability to mobilize spectacle to imperial purposes during the Bordeaux visit was duly noted (along with his Bonapartist sympathies and energies). In June 1853 he was reassigned to Paris. On the day that Haussmann took his oath of office, the Emperor handed him a map, so the legend spun by Haussmann in his Mémoires has it, on which were drawn in outlines of four different colors (representing the urgency of the projects) the plans for the reconstruction of the street system of Paris. This was, according to Haussmann, the plan that he faithfully carried out (with a few extensions) over the next two decades.

Figure 5 This photo by Marville (taken sometime in 1850–1851) shows the demolitions already under way around the Rue de Rivoli and the Palais

We now know this to be a myth.5 There had been considerable discussion about, as well as practical efforts (led by Rambuteau, who was prefect from 1833 until 1848) toward the modernization of Paris under the July Monarchy. During the 1840s innumerable plans and proposals were discussed. The Emperor, after being elected President in 1848, had already been party to urban renewal initiatives, and Berger, Haussmann’s predecessor, had begun the task in earnest. The Rue de Rivoli was already being extended, as was the Rue Saint Martin; and there are LeSecq’s and Marville’s photos and Daumier’s trenchant commentaries on the effects of the demolitions from 1851–1852, a year before Haussmann took office, to prove it.6 Furthermore, the Emperor appointed a commission under Count Simeon in August 1853 to advise upon urban renewal projects. Haussmann claimed it rarely met and produced only an interim report marked by banal and impracticable recommendations. It in fact met regularly and produced an elaborate and extremely detailed plan that was delivered to the Emperor in December 1853. Haussmann deliberately ignored it, though what influence it had on the Emperor (who consulted rather more frequently with Haussmann than the latter admitted) is not known. Haussmann, furthermore, did both more and less than the Emperor wanted. The Emperor had instructed him to be sensitive to existing structures of quality and to avoid the straight line. Haussmann ignored him on both counts. The Emperor had little interest in the delivery of running water or in the annexation of the suburbs, but Haussmann had a passion for both—and got his way. Haussmann’s Mémoires, upon which most accounts have hitherto relied, are full of dissimulation.

Figure 6 Daumier here takes up, as early as 1852, the issue of the displacement of populations by the demolitions. Interestingly, he never bothered with the issue again.

There is, however, something very telling about Haussmann’s denials. They reveal far more than egoism and vanity (though he had plenty of both). They signal in part what it was that Haussmann had to struggle against. He needed to build a myth of a radical break around himself and the Emperor—a myth that has survived to the present day—because he needed to show that what went before was irrelevant; that neither he nor Louis Napoleon was in any way beholden to the thinking or the practices of the immediate past. This denial did double duty. It created a founding myth (essential to any new regime) and helped secure the idea that there was no alternative to the benevolent authoritarianism of Empire. The republican, democratic, and socialist proposals and plans of the 1830s and 1840s were impractical and unworthy of consideration. Haussmann devised the only feasible solution, and it was feasible because it was embedded in the authority of Empire. In this sense there was indeed a real break in both thought and action after the disruptions set in motion by 1848 had done their work. Yet Haussmann also acknowledged, in an exchange of letters with the Emperor that prefaced the publication of the first volume of the Histoire Générale de Paris (published in 1866), that “the most striking of modern tendencies” is to seek within the past for an explication of the present and a preparation for the future.7

If the break that Haussmann supposedly made was nowhere near as radical as he claimed, then we must search (as Saint-Simon and Marx insist) for the new in the lineaments of the old. But the emergence of the new (as Saint-Simon and Marx also insist) can still have a not-to-be-denied revolutionary significance. Haussmann and his colleagues were willing to engage in creative destruction on a scale hitherto unseen. The formation of Empire out of the ruins of republican democracy enabled them to do this. Let me preview the sorts of shifts I have in mind.

Hittorf had been one of the main architects at work on the transformation of Paris under the July Monarchy. A new avenue to link the Arc de Triomphe and the Bois de Boulogne had long been mooted, and Hittorf had drawn up plans for it. The street was to be very wide by existing standards—120 feet. Hittorf met with Haussmann in 1853. The latter insisted there be 440 feet between the facing buildings with an avenue 360 feet wide.8 Haussmann thus tripled the scale of the project. He changed the spatial scale of both thought and action. Consider another instructive example. The provisioning of Paris through Les Halles had long been recognized as inefficient and inadequate. It had been a hot topic of debate during the July Monarchy. The former prefect Berger, under orders from Louis Napoleon as President, had made it a priority to redesign it. Figure 7 shows the old system (soon to be demolished), where merchants stored their goods as best they could under the overhanging eaves of the houses. Louis Napoleon suspended work on Baltard’s new building of 1852—known locally as “the fortress of Les Halles”—as a totally unacceptable solution (figure 8). “We want umbrellas” made “of iron,” Haussmann told a chastened Baltard in 1853, and that, in the end, is what Baltard gave him, though only after Haussmann had rejected (thereby earning Baltard’s perpetual resentment) several hybrid designs. The result was a building that has long been regarded as a modernist classic (see figure 9). In his Mémoires, Haussmann suggests he saved Baltard’s reputation (when Louis Napoleon asked how an architect who produced something so awful in 1852 could produce such a work of genius two years later, Haussmann immodestly replied “different prefect!”).

Figure 7 This lithograph by Provost depicts conditions in Les Halles in the early 1850s (it parallels a photograph taken by Marville; see De Thèzy, 1994, 365). The new Les Halles is on the right and the old system, in which merchants stored their goods under the overhanging eaves of the buildings, is on the left.

Figure 8 Baltard’s first design of 1852 for the new Les Halles (known as La Fortresse), here recorded in a photograph by Marville, was heartily disapproved of by the Emperor and Haussmann, and soon dismantled.

Figure 9 “Umbrellas of iron” is what Haussmann wanted, and eventually what Baltard gave him, in the classic modernist building of Les Halles from 1855.

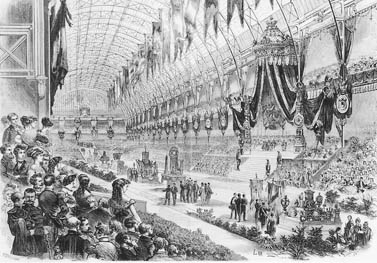

Then go to the Palais de l’Industrie, built for the Universal Exposition of 1855 (figure 10) and see a cavernous space that goes far beyond Baltard. Now compare these new spaces with the arcades that had been so important in the early 1800s (figure 11). The form and the materials are the same, but there has been an extraordinary change of scale (something that, incidentally, Walter Benjamin fails to register in his Arcades project in spite of his intense interest in the spatial forms of the city). The architectural historian Loyer, in his detailed reconstruction of architectural and building practices in nineteenth-century Paris enunciates the principle at work exactly: “One of capitalism’s most important effects on construction,” he writes, “was to transform the scale of projects.”9 While Haussmann’s myth of a total break deserves to be questioned, we must also recognize the radical shift in scale that he helped to engineer, inspired by new technologies and facilitated by new organizational forms. This shift enabled him to think of the city (and even its suburbs) as a totality rather than as a chaos of particular projects.

Figure 10 The Palais de l’Industrie, as portrayed by Trichon and Lix, achieved an even grander interior space than Les Halles, illustrating again a radical transformation of scale made possible by new materials, architectural forms, and modes of organization of construction.

Figure 11 This Marville photo of an arcade—the Passage de l’Opéra—illustrates the dramatic shift in scale (though not in form) that occurred in construction between the 1820s, when many of the arcades were built, and Les Halles and the Palais de l’Industrie of the 1850s.

In a seemingly quite different register, consider the radical break that Flaubert supposedly accomplished in his writing. Before 1848, Flaubert was a miserable failure; he agonized, to the point of nervous breakdown in the 1840s, over how and what to write. His explorations of Gothic and Romantic themes produced abysmal literature, no matter how hard he worked at polishing his style. Even his best friends (Maxime du Camp and Louis Bouilhet) considered the first draft of his Temptation of Saint Anthony a total failure, and in 1849 clearly told him so. Bouilhet then advised a shocked Flaubert that he should study Balzac and suggested, according to Steegmuller, “that if Flaubert were to write a novel about the bourgeois (a class that had always interested him and which he was wrong to believe unworthy of literary treatment), emphasizing their emotional rather than their material concerns and employing a good style of his own, the result would be something new in the history of literature.” Two years later (after Flaubert’s voyage to the Orient), Bouilhet suggested that Flaubert take up the tragic suicide of a provincial doctor’s wife and treat it (a scene from provincial life, as it were) in the manner of Balzac.

Flaubert swallowed his pride (Balzac, he had early on concluded, had not the faintest idea of how to write) and dutifully worked on this from 1851 to 1856. Madame Bovary, when published, was (and still is) widely acclaimed as the first major literary sensation and masterpiece in Second Empire culture.10 It is even sometimes depicted as the first great modernist novel in the French language. However that may be, Flaubert finally came into his own only after romanticism and utopianism were put to the sword in 1848. Emma Bovary commits suicide, the victim of banal romantic illusions, in exactly the same way that the revolutionary romantics of 1848 had, in Flaubert’s view, committed suicide on the barricades (in the senseless way he was to depict in Sentimental Education). Wrote Flaubert of Lamartine: “The people have had enough of poets” and “Poets cannot cope.” Flaubert downplayed his debt to Balzac (much as Haussman denied the influence of his predecessors), but he perceptively recognized the dilemma. “To accomplish something lasting,” he wrote, “one must have a solid foundation. The thought of the future torments us, and the past is holding us back. That is why the present is slipping from our grasp.”11

That apostle of modernity, Baudelaire, lived with this dilemma daily, careening from side to side with the same incoherence with which he slid from one side of the barricades to the other in 1848.12 He had already signaled rejection of tradition in his Salon of 1846, urging artists to explore the “epic qualities of modern life,” for their age was “rich in poetic and wonderful subjects,” such as “scenes of high life and the thousands of uprooted lives that haunt the underworld of a great city, criminals and prostitutes.” “The marvelous envelops us and saturates us like the atmosphere; but we fail to see it,” he then wrote. Yet he dedicated his work to the bourgeoisie, invoking their heroism: “You have entered into partnership, formed companies, issued loans, to realize the idea of the future in all its diverse forms.” Though there may be a touch of irony in this, he is also appealing to the Saint-Simonian utopianism that sought to harness the qualities of visionary poet and astute businessman to the cause of human emancipation. Baudelaire, caught in his own struggle against tradition and the “aristocrats of thought,” and incidentally also inspired by the example of Balzac, proposed an alliance with all those among the bourgeoisie seeking to overthrow traditional class power. Both, he hoped, could nourish the other until “supreme harmony is ours.”13

But that alliance was not to be. How, after all, could artists depict the heroism in those “uprooted lives” in ways not offensive to the bourgeoisie? Baudelaire would be torn for the rest of his life between the stances of flaneur and dandy, a disengaged and cynical voyeur on the one hand, and man of the people who enters into the life of his subjects with passion on the other. In 1846 that tension was only implicit; but 1848 changed all that. He fought on the side of the insurgents in February and June, and perhaps also in May. He was horrified by the betrayal wrought by the bourgeoisie’s Party of Order but equally distressed at the empty rhetoric of Romanticism (as represented by the poet Lamartine). Disillusioned, Baudelaire switched to the socialist Pierre Proudhon as hero for a while, then linked up with Gustave Courbet, attracted by the realism of both men. In retrospect, he wrote, “1848 was charming only through an excess of the ridiculous.” But the evocation of “excess” is significant. He recorded his “wild excitement” and his “natural” and “legitimate pleasure in destruction.” But he detested the result. Even return to the secure power of tradition then seemed preferable. In between the high points of revolutionary engagement, he helped edit reactionary newspapers, later writing, “There is no form of rational and assured government save an aristocracy” (Balzac’s sentiments exactly). After his initial fury at Louis Napoleon’s coup d’état, he withdrew from politics into pessimism and cynicism, only to confess his addiction when the pulse of revolution began to throb: “The Revolution and the Cult of Reason confirm the doctrine of Sacrifice,” he wrote.14 He even came to express sporadic appreciation of Louis Napoleon as someone cast in the role of warrior-poet as King.

There is a contradiction in Baudelaire’s sense of modernity after the bittersweet experience of creative destruction on the barricades and the sacking of the Tuileries Palace in 1848. Tradition has to be overthrown, violently if necessary, in order to grapple with the present and create the future. But the loss of tradition wrenches away the sheet anchors of our understanding and leaves us drifting, powerless. The aim of the artists, he wrote in 1860, must therefore be to understand the modern as “the transient, the fleeting, the contingent” in relation to that other half of art which deals in “the eternal and immovable.” The fear, he says, in a passage that echoes Flaubert’s dilemma, is “of not going fast enough, of letting the spectre escape before the synthesis has been extracted and taken possession of.”15 But all that rush leaves behind a great deal of human wreckage. The “thousand uprooted lives” cannot be ignored.

There is an eloquent evocation of this in his story of “The Old Clown” in Paris Spleen. Paris is there depicted as a vast theater. “Everywhere joy, moneymaking, debauchery; everywhere the assurance of tomorrow’s daily bread; everywhere frenetic outbursts of vitality.” The fête imperiale of the Second Empire is in full swing. But among the “dust, shouts, joy, tumult,” Baudelaire sees “a pitiful old clown, bent, decrepit, the ruin of a man.” The absoluteness of his misery is “made all the more horrible by being tricked out in comic rags.” The clown “was mute and motionless. He had given up, he had abdicated. His fate was sealed” (figure 12). The author feels the “terrible hand of hysteria: gripping his throat,” and “rebellious tears that would not fall” blur his sight. He wants to leave money, but the motion of the crowd sweeps him onward. Looking back, he says to himself, “I have just seen the prototype of the old writer who has been the brilliant entertainer of the generation he has outlived, the old poet without friends, without family, without children, degraded by poverty and the ingratitude of the public, and to whose booth the fickle world no longer cares to come.”16

Figure 12 Daumier’s touching The Clown captures something of the sentiments expressed in Baudelaire’s prose poem. With the crowd moving away from him and only a boy looking curiously on, he stares into the distance like some noble figure now left behind.

For Marx, 1848 marked a similar intellectual and political watershed. Experienced from afar in exile in London (though he did visit Paris in March), the events of 1848–1851 in Paris were to be an epiphany without which his turn to a scientific socialism would have been unthinkable. The radical break often evinced between the “young” Marx of the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and the “mature” Marx of Capital was, of course, no more radical than were Haussmann’s or Flaubert’s shifts, but it was nonetheless significant. He had been deeply affected by Romanticism and socialist utopianism in his early years, but was scathing in his dismissal of both in 1848. While there may have been a historical moment when utopianism had opened up new vistas for working-class consciousness, he wrote, it was now at best irrelevant and at worst a barrier to revolution. It is understandable, given the chaotic ferment of ideas produced in the 1840s in France (the subject of chapter 2, below) that Marx would have a strategic interest in boiling down oppositional thought to a much more rigorous and tougher synthetic science of socialism. But for the Marxist movement later to assume a radical break, as if nothing that happened before was relevant, has been a serious error. Marx took all manner of ideas from thinkers like Saint-Simon, Louis Blanqui, Robert Owen, and Etienne Cabet; and even when he rejected others, he shaped his conception as much through critique and opposition as through plucking thought out of thin air. His presentation of the labor process in Capital is shaped in response to Fourier’s idea that unalienated labor is defined solely by passionate attraction and the joy of play. To this Marx replies that it takes commitment and grit to complete major projects, and that the labor process, however noble, can never entirely escape the arduousness of hard work and collective discipline. Marx in any case held—and this he took from Saint-Simon—that no social order can change without the lineaments of the new already being present in the existing state of things.

If we apply that principle rigorously to what happened in and after 1848, we would see not only Flaubert, Baudelaire, and Haussmann, but also Marx himself, in a very particular light. But the fact that Haussmann, Marx, Flaubert, and Baudelaire all came into their own so spectacularly only after 1848 gives support to the myth of modernity as a radical break, and suggests that it was the experience of those years which had something vital to do with subsequent transformations in thought and practice in a variety of settings. This, it seems to me, is the central tension to be addressed: How far and in what ways were the radical transformations achieved after 1848 already prefigured in the thought and practices of earlier years?

Marx, like Flaubert and Baudelaire, was greatly influenced by Balzac. Paul Lafargue, Marx’s son-in-law, noted that Marx’s admiration for Balzac “was so profound that he had planned to write a criticism of “La Comédie Humaine” (“The Human Comedy”) as soon as he should have finished his economic studies.”17 The whole of Balzac’s oeuvre, in Marx’s judgment, was prescient about the future evolution of the social order. Balzac “anticipated” in uncanny ways social relations that were identifiable only “in embryo” in the 1830s and 1840s. In drawing back the veil to reveal the myths of modernity as they were forming from the Restoration onward, Balzac helps us identify the deep continuities that underlay the seemingly radical break after 1848. The covert dependency of both Flaubert and Baudelaire upon the perspectives he developed shows this continuity at work even on the terrain of literary production. Marx’s explicit debt spreads the continuity across political economy and historical writing. If revolutionary movements draw upon latent tensions within the existing order, then Balzac’s writings on Paris in the 1830s and 1840s stand to reveal the nature of such. And out of these possibilities, the transformations of the Second Empire were fashioned. In this light I examine Balzac’s representations of Paris in chapter 1.

Daumier’s art, of which I make considerable illustrative use here, exhibited similarly prescient qualities. Frequently compared to Balzac, Daumier produced incessant commentary on daily life as well as politics in Paris that forms an extraordinary source. Baudelaire once complained that viewers of Daumier merely looked at the joke and paid no mind to the art. Art historians have subsequently rescued Daumier from dismissal as a mere caricaturist and focused on the finer points of his art, though given his prolific output, the work is generally acknowledged as of uneven quality. But I am here more concerned with the subjects he chooses and the nature of the jokes that he (and others, such as Gavarni and Cham) shared with his audience. What Daumier so often does is to anticipate, and thereby render very visible, processes of change in an embryonic state. As early as 1844 he satirized the way the new dry goods stores were organized, and anticipated the experience of the department stores of the 1850s and 1860s. Most of his commentaries on clearances and demolitions (dismissed by Passeron as inferior art) are from 1852, before the more massive demolitions occurred. He had, then, an uncanny ability to see not only what the city was, but what it was becoming, well before it got there.18

This issue of how to see the city and how to represent it during phases of intense change is a daunting challenge. Novelists like Balzac and artists like Daumier pioneer ways to do it in interesting but indirect ways. It is a curious fact, however, that although there are innumerable studies and monographs on individual cities available, few of them turn out to be particularly memorable, let alone enlightening about the human condition. There are, of course, exceptions. I have always taken Carl Schorske’s fin-desiècle Vienna as the model to be aspired to, no matter how impossible to replicate.19 An interesting feature of that work is precisely how it manages to convey some sense of the totality of what the city was about through a variety of perspectives on material life, on cultural activities, on patterns of thought within the city. The most interesting urban writing is often of a fragmentary and perspectival sort. The difficulty then is to see the totality as well as the parts, and it is on this point that fin-de-siècle Vienna works its particular magic. This difficulty is pervasive in urban studies and urban theory. We have abundant theories as to what happens in the city but a singular lack of theory of the city; and those theories of the city that we do have often appear to be so one-dimensional and so wooden as to eviscerate the richness and complexity of what the urban experience is about. One cannot easily approach the city and the urban experience, therefore, in a one-dimensional way.

This fragmented approach to the totality is nowhere more brilliantly articulated than in Walter Benjamin’s study of Paris in his Arcades project.20 This has been the focus of considerable and growing interest in recent years, particularly after the appearance of a definitive English translation of the Arcades study in 1999. My aim is, of course, quite different from Benjamin’s. It is to reconstruct, as best I can, how Second Empire Paris worked, how capital and modernity came together in a particular place and time, and how social relations and political imaginations were animated by this encounter. Benjamin scholars should, I hope, find something useful in this exercise. I do, of course, make use of many of Benjamin’s insights, and I do have some rough ideas as to how to read (and even, as already suggested by the examination of the scale of spatial form, to critique) him. The fascination of his Arcades project for me rests upon the way in which he assembled a vast array of information from all sorts of secondary sources and began to lay out the bits and pieces (the “detritus” of history, as he called it), as if they were part of some giant kaleidoscope of how Paris worked and how it became such a central site for the birth of the modern (as both techne and sensibility). He plainly had a grand conception in mind, but the study was unfinished (perhaps unfinishable) and its overall shape (if it was ever meant to have one) therefore remains elusive. But, like Schorske, Benjamin does return again and again to certain themes, persistent threads that bring together the whole and render some vision of the totality possible. The arcades (a spatial form) operate as a recurrent motif. Benjamin also insists (as do some other Marxist writers, such as Henri Lefebvre) that we do not merely live in a material world but that our imaginations, our dreams, our conceptions, and our representations mediate that materiality in powerful ways; hence his fascination with spectacle, representations, and phantasmagoria.

The problem for the reader of Benjamin is how to understand the fragments in relation to the totality of Paris. Some, of course, would want to say it just doesn’t fit together and it is best to leave it at that; to superimpose thematics (be it Benjamin’s arcades or my own concern for the circulation and accumulation of capital and the pervasiveness of class relations) is to do such violence to experience that it is to be resisted at all costs. I have much more faith in the inherent relations between processes and things than to be satisfied with that. I also have a much deeper belief in our capacities to represent and communicate what those connections and relations are about. But I also recognize, as any theorist must, the necessary violence that comes with abstraction, and that it is always dangerous to interpret complex relations as simple causal chains or, worse still, as determined by some mechanistic process. Resort to a dialectical and relational mode of historical-geographical inquiry should help avoid such traps.

A work of this kind (and this was as true for Schorske and Benjamin as it has been for me) necessarily depends heavily on archival work done by others. The Parisian archive has, however, been so richly mined, and the secondary sources are so abundant (as the lengthy bibliography attests), that it takes a major effort to bring innumerable studies done from different perspectives into a dynamic synthesis. Reliance upon secondary sources (many informed by a completely different framework of concepts and theory than that which animates my own) is in some ways limiting, and always poses the question of reliability and trustworthiness, to say nothing of their compatibility. I have frequently read these sources against the grain of their own theoretical framework, but the archival work on Paris has, from no matter what perspective, been carefully done (Gaillard’s outstanding study,21 on which I rely heavily, is an example), and I have striven to retain the integrity of substantive findings.

To put things this way is also to go against the grain of much contemporary academic practice, which concentrates on the discursive constructions that permeate supposedly factual accounts in order to understand the latter as cultural constructions open to critique and deconstruction. Such interrogations have been invaluable. From this standpoint, to speak of the “integrity” of findings is highly suspect, since integrity and truth are effects of discourse. It is useful to know, for example, that the statistical inquiry into Parisian industry of 1847–1848 was riddled with conservative political-economic presuppositions that, among other things, classified workers subcontracted at home as “small businesses” and which sought to foreground the importance of the family as guardian of social order.22 And Rancière’s challenge to the “myth” of the artisan distressed at the deskilling, degradation, and loss of nobility of work as a prime actor in class struggle has to be taken very seriously.23

But a work of synthesis, of the sort I am here attempting, must perforce construct its own rules of engagement. It cannot stop at the point of endless deconstruction of the discursive elaborations of others, but has to press on into the materiality of social processes even while acknowledging the power and significance of discourses and perceptions in shaping social life and historical-geographical inquiry. For this the methodology of historical-geographical materialism, which I have for several years been evolving (and to which the original Paris study published in 1985 so signally contributed) provides, I believe, a powerful means to understand the dynamics of urban change in a particular place and time.24 I emphasize, however, my deep indebtedness to the long-standing tradition of serious scholarship that has mined the Parisian archive so well and reflected on its meanings for so long from so many diverse perspectives. The extraordinary facilities in the Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris (an institution that Haussmann set up) and the collection of visual materials (including Marville’s photos, commissioned on Haussmann’s watch to record what was being creatively destroyed) now assembled in the Photothèque des Musées de la Ville de Paris made the preparation of this work much easier as well as pleasurable.

The study of Paris in part II is a revised and extended version of the essay in Consciousness and the Urban Experience (published jointly by Johns Hopkins University Press and Basil Blackwell in 1985). The coda, “The Building of the Basilica of Sacré Coeur,” is slightly revised from the same volume; it had initially appeared in the Annals of the Association of American Geographers in 1979. The study on Balzac is a revised and extended version of earlier efforts separately published in Cosmopolitan Geographies, edited by Vinay Dharwadker (published by Routledge in 2001) and in Afterimages of the City, edited by Joan Ramon Resina (published by Cornell University Press in 2002). Chapter 2 and this introduction are wholly new.