Figure 4.01: Phase plans of the granary building, at 1:500.

Grid squares: F08, F09, F10, F11, G08, G09, G10, G11, H08, H09, H10, H11

The granary posed the particular problems of interpretation because it was excavated in three separate stages: 1977 (southern end only); 1981 (remains exposed but little excavation); 1983 (full excavation). Moreover it appears the excavators in 1983 were largely unaware of the results of 1981. It should be emphasised that this is virtually the only instance, in what was a huge programme of excavation, spanning ten years, whereby the process of excavating and re-excavating particular areas over several seasons became uncoupled in this way and the results of a previous season’s work were not fully taken into account. The ‘decoupling’ in this instance caused particular problems in analysing the area immediately to the south of the granary. It also led to the 1981 discovery of a secondary sleeper wall and associated flagging over the layers of the floor base in the west granary being ignored in 1983, which in turn resulted in the base layers being interpreted as successive floor levels. It would appear that the excavators in 1981 were principally focussed on uncovering the remains of the headquarters building, with the work on the granary and adjacent area to the south forming a peripheral element of that season’s investigation. There was a hiatus in 1982, when no excavation was undertaken in the fort, and, consequently, when work resumed in 1983, largely with different personnel (although Charles Daniels was still involved), the significance of the 1981 season’s results for interpretation of the granary was not recognised.

On excavation the granary (numbered Building 7 by the excavators) was found to have been severely damaged. The outer walls were extensively robbed and the deposits associated with the internal layout of the structure, particularly its western half, had been truncated. Furthermore there were very few finds.

Remains of cord-rig cultivation were revealed beneath the granary in a section cut across the centre of the building and in further, smaller spit cut towards the south end of the west granary (G09:35, G10:37, F10:53 – see Chapter 3). Blackened patches of clay amongst the rig features suggested burning on the site, probably prior to construction. These deposits were covered by a spread of redeposited yellow/red clay and small stones (F10:54, G10:36, G11:77). In the south-west corner of the granary this clay was in turn overlain by a layer of small/medium sized stones set in sandy yellow clay (F10:41, F11:76, G10:38, G11:76), which was interpreted as a possible laid surface.

In its primary phase, Building 7 comprised a rectangular, double granary measuring 26m × 11.40m. The structure was orientated north-south. The floor of the east granary was supported by three longitudinal sleeper walls. The west granary had a solid base composed of several layers of clay and stone. This again supported a series of longitudinal sleeper walls of which only a small fragment of one wall survived when uncovered in 1981. The two halves of the granary were separated by a north-south spine wall, which has been entirely removed by later robbing (G08:29, G09:15, G10:32, G11:64). The outer walls, too, were heavily robbed down to their foundations after the Roman period, the outline of the building being defined by robber trenches, with only two short stretches of actual masonry surviving on the north and west sides (G08:12, F09:14). These were constructed of roughly squared sandstone facing stones with a rubble core and varied in thickness between 0.80m and 0.65m. They were set on rubble foundations. The outer walls were externally buttressed along each side. On the north and south walls buttresses were provided at the terminals of the three main longitudinal walls, whilst the west wall was furnished with ten buttresses, but only nine were attached to the east wall. These buttresses survived better than the outer walls themselves, with several along the west and, to a lesser extent, the east sides being missed by the stone-robbing trenches.

The east granary was characterised by three, parallel, north-south sleeper walls, which would have supported an elevated floor composed either of stone flags (as at Corbridge) or timber joists and planking. Raising the floor in this way was designed to reduce problems of damp and vermin. The easternmost of the sleeper walls (H08:24, H09:19, G08:30, G09:05, G10:24, G11:57) was relatively well-preserved, surviving to two courses for much of its length, but the others were severely robbed (G08:25, G09:11, G11:59; G08:27, G09:13, G11:61) with only short stretches of surviving masonry remaining near the centre of the building (G10:19, G10;22). Flags were laid on the ground surface in the 0.50m wide channels between the walls and measured up to 0.50 by 0.50m in size. Again these survived only in a central strip across the width of this half of the granary and at the southern end of the easternmost channel (G10:20, 21; G10:18, G11:56). (See Hodgson 2003, 173–4 for re-excavation of the flagging in 1997–8.)

Figure 4.02: Granary and Alley 8 from the north. Note the robbed outer walls, the NW loading steps and the well preserved sleeper wall G08:30.

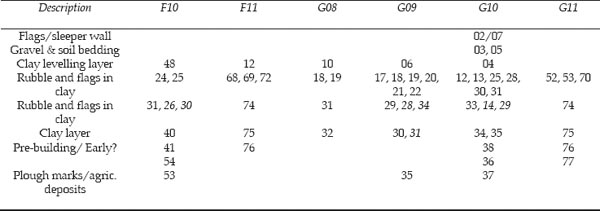

The arrangements in the west granary differed quite markedly from those in the east granary. A series of distinct makeup layers, composed of clay or rubble, cobbles and flags, were identified when the building was fully excavated in 1983 (see Table 4.01; Fig. 4.04) . These were interpreted by the excavators as successive floor levels, each representing a different structural phase, which were integrated into the overall fourperiod framework envisaged at that stage. In actuality these layers of clay and stone provided a base or raft on top of which were constructed a set of sleeper walls and flagging. Only a fragment portion of one sleeper wall (G10:07) and a small area of flags (G10:02) survived when these features were recorded in 1981 (see Fig. 4.03). These were broadly similar in form to, but differed in detail from, those recorded in the east granary. No equivalent levelling deposits were reported in the east granary, though the likely existence of some kind of clay construction deposit under both granaries may be suspected, as the photographs and plans make it clear that the pre-fort cultivation furrows were only revealed at the base of the shallow trench cut across the centre of the granary following the removal of the structures (see Fig 3.9).

Table 4.01: Sequence of west granary ‘floors’

Italics = ‘Partitions’

The lowest of the levelling deposits was composed of clay (F10:40, F11:75, G08:32, G09:30, G10:34, 35, G11:75) with a wide darker band running east-west approximately one third of the way down (G09:31) – see Figs 4.04 (left) and 4.05. The latter was originally interpreted as evidence for some kind of floor partition. The clay band was narrower at its west end (0.30m) than its east (1.30m), and rather irregular in its course. Its significance remains unclear. It is rather too wide and irregular for a timber and wattle partition. Also a possible post-hole (G09:33), filled with clay and coal (G09:32), was identified 1.00m north of the clay band and 2.30m from the west wall of the granary. This post may have been associated with the construction of the building.

Next a clay and cobble level (F10:31, F11:74, G08:31, G09:29, G10:33, G11:74), which incorporated areas of flagging within it, was deposited over the clay level (Figs 4.04 right; 4.06–4.08). Slight traces indicating the presence of two ‘partitions’ (neither of which was visible in the levels above or beneath) were noted in this layer, dividing it into unequal thirds, with the smaller areas situated at the north and south ends of the Granary and a larger undivided area in the centre. The southern partition was indicated by a rough edge or face to a line of stones (F10:26, G10:14) clearly differentiated from a small area of flag stones to the south (F10:30, G10:29). The northern one was marked by a straight edge where an area of flagging (G09:28) butted against a spread of cobbles (G09:34). Two possible post-holes were also noted in the northern half of this surface (G09:24; G09:27), one actually being set on the line of the northern partition (G09:24). The lines of stones and edges of flagging probably simply reflect the manner in which the layer was constructed, perhaps in three discrete dumps. The stone and clay may have been dumped from either end of the granary first, perhaps packed up against a vertically set plank or beam, in much the same way that modern concrete surfaces are often laid. Once stabilised the planks would have been removed and the central dump of clay and stone deposited. The post holes, too, might be functionally related to the actual construction process. The flags incorporated in this layer may conceivably have been deposited deliberately, in order to facilitate access during the dumping of the stone and clay.

Figure 4.06: The flag and rubble make up for the west granary viewed from the west in 1983. Note the exceptional preservation of the sleeper wall G08:30 in the east granary.

A further layer of rubble set in clay (F10:24, F11:68, G08:19, G09:18, G10:12, G11:52) with patches of flagging (F10:25, F11:69, 72, G08:18, G09:17, 19–22, G10:13, 25, 28, 30–31, G11:53, 70) was laid over the previous layer. The rubble used in this layer was more angular, in contrast to the rounded cobble stones employed in the first dump, and no evidence for any divisions was recognised in this surface. Again the deposition of patches of flagging may have had a deliberate purpose.

The upper level of rubble and flags was itself completely covered by a further clay layer (F10:48, F11:12, G08:10, G09:06, G10:04), which formed a level bedding for the flagged floor and sleeper walls above. The site context records are not very informative, but the summary descriptive ‘Buildings Notes’, compiled in 1984 following excavation, indicate that this layer of clay, observed covering the entire western half of the granary (apart from the robbed area at the north end of the structure in grid square G08), was 0.10m thick. Only a small area of flagged flooring (G10:02) and a portion of one sleeper wall (G10:07), on a bedding of soil and gravel (G10:03, 05), survived over clay layer F10:48, but they are sufficient to confirm that the different layers of clay and cobbles plus flagstones in the western granary did indeed represent a sequence of makeup deposits for the granary rather than a series of floors as first believed (Fig. 4.03). The deposits were in any case too low to represent granary floors, given that the existence of stepped loading platforms shows both the east and west granaries were entered at a similar, elevated, level. The makeup layers had the effect of raising the base for the sleeper walls in the west granary to a higher level than that in the east granary. However, as the full height of the sleeper walls in either half of the structure is not known, the actual floor supported on the sleeper walls need not have differed from that of the east granary. The surviving sleeper wall (G10:07) was orientated longitudinally, roughly north south, like its primary counterparts in the east granary, but its position shows that the spacing was rather different and there were perhaps two or four such walls rather than the three of the east granary layout. A possible break was identified in the west granary sleeper wall, which may originally have formed one of a whole series of such ventilation gaps deliberately inserted to facilitate the circulation of air beneath the floor. That this break was not simply a reflection of the partial survival of the wall is suggested by the fact that a flag was laid in the break. In the east granary, the sleeper walls are abutted by flags laid in the intervening channels, but no flagging underlies the walls and there are no evident breaks in the walls.

Figure 4.07: As 4.06. A modern drain trench has cut a section through the make up. The large posthole towards the north end of the structure is a colliery era intrusion.

At either end of both the eastern and western granaries were substantial stone steps, termed ‘loading platforms’ by Daniels, which led up to the granary entrances at the level of the raised floor. There was definite evidence of one bay at the southern end of the western granary and another at the northern end of the eastern granary. There were traces of possible robbed bays at the other ends of both. There was no stratigraphic link between any of these stepped platforms and the remainder of the granary structure since the adjacent outer walls had been removed by robbing trenches. None of the steps survived higher than lowest tread.

The north-eastern loading platform (G08:03) was the best preserved and was c. 2.40m long and 1.4m wide. It was constructed of rubble, revetted on the east and west sides by small, roughly-cut blocks, tapering inwards to key them in. The north face, however comprised a pair of large, well-cut, oblong slabs (G08:13), each measuring 1.20m by 0.30m. The northern lips and corners of the two slabs were rounded either by extensive wear or more probably by design (see below), whilst the southern edge of the stones was rebated, to take two further slabs forming the next step. This demonstrates (if demonstration were needed) that the ‘platform’ was originally stepped and the threshold and floor of the east granary were at a somewhat higher level than the building’s surviving remains. The dimensions of the south-west platform (F11:09) were virtually identical to those of its north-eastern counterpart and the form of construction very similar, though this platform was less well-preserved (Fig. 4.09). In this case no trace of a rubble core remained, but a rectangular spread of clay formed the base for the platform (F11:56). Again there were two stone slabs on the outer (southern) edge of the platform but neither was as long as the north-east pair and there was a gap where at least one additional slab had been removed. The inner edge of the surviving slabs was rebated, exactly like their counterparts on the north-east platform, and presumably similarly once held the slabs which formed the next tread of the steps. Parts of the side walls of the platform also remained. The south-east and north-west platforms had been virtually totally robbed away or demolished, the former only being represented by a spread of small-medium sized stones set in dark brown silty clay (G11:81) in the corresponding position. A similar platform-shaped stone scatter (G08:16) represented the robbing residue of the north-west platform, but here, beneath the spread, the trench (G08:39) cut to rob out the facing stones were recognised, enclosing the clay base of the platform.

Figure 4.09: Close up of the SW loading steps serving the west granary. The NE corner of Building AV is also visible.

Evidence for a portico on the south side was identified in the form of a single pier base (G11:21; TWM 7907), on the same north-south line as the central dividing wall of the granaries. The base was a large, wellshaped block of coarse-grained green sandstone, 0.90m square and 0.10m high (dimensions recorded by TWM: 0.94m × 0.92m in plan with a maximum height of 0.23m), very neatly cut with rounded top edges, very like the lips of the loading platform steps. It was set in the primary gravel surface (F11:53, G11:20, G12:23, G12:16?) of the via quintana, which was composed of small cobbles c. 005m in diameter interspersed with flags up to 0.20m in diameter (F11:73, G11:71). No evidence was identified in 1983–84 for the other two bases which originally stood opposite the south-east and south-west corners of the granary, but the substantial oblong foundations (TWM 7496, 7499 and 7655) for all three piers were identified in 1997–8, along with a number of other pits and post holes probably associated with the construction of the portico (see Hodgson 2003, 172–3 for a detailed description). One of the pits (7442) was interpreted as having held an upright post for a crane or similar device associated with the erection of the south-eastern pier. The three foundation pits were filled with sandstone fragments and cobbles capped with red clay. The westernmost pit (7497), which was emptied, had dimensions of 1.80m × 1.16m with a maximum depth of 0.21m.

The area of the corresponding portico north of the granary was investigated by Tyne and Wear Museums in 1997 (see Hodgson 2003, 172, for full description). The earliest Roman deposits encountered in this area were dumps of clay and layers of sand and crushed white and yellow sandstone similar to the crumbled sandstone spreads found immediately to the east of the south portico (south of Alley 8 – G11:82–83, H11:69–70). These layers were connected with the construction of the fort. They rested on the Iron Age cord rig and the clay dumps filled slots which had been dug in the furrows by the native farmers. The foundations for the two flanking piers of the north portico (TWM 5321, 5303) were cut from the surface of these deposits whilst the foundation for the central pier (5320) was cut from the level of the underlying, prefort soil horizon (5302). The foundations comprised deposits of sandstone fragments packed in brown clay filling roughly square pits. Each foundation pit had postholes to the north and south which also cut the construction dumps and which were probably connected with raising the columns on the tightly packed foundations. Layers which were laid down during fort construction covered the southern edge of the fill of the central foundation pit and its associated postholes. All the pits and other postholes were sealed below an extensive layer of blocks which were the bedding for a street surface. As this was the lowest street surface on the via principalis it was probably primary to the building of the fort.

Figure 4.10: The south end of the granary viewed in 1983. Note the SW loading steps, the central pier base of the portico, the remains of Building AV and drain F11:63/G11:51. In the background sleeper wall G11:57, drains G11:07 and G11:79 and the crosswall foundation trench of AW can also be seen.

FINDS

West granary make up layers

Samian stamp: 130–50 (no. S8, F11:12)

Coin: Trajan, 103–11 (no. 52, G09:30)

Lead: disc (no. 33, G09:29)

Stone: whetstone (no. 12, F11:12)

Quern: beehive (no. 8, G10:12)

Most of the make-up layers in the west granary produced only a few sherds of pottery, including two sherds of second-century mortaria and a few sherds of reduced wares. The largest group came from context G10:35, which was still approximately only 20 sherds in total, most of which was made up of the locally produced second-century grey wares.

The floor of the east granary produced only six sherds of pottery in total, including two BB2 sherds (G10:18), which appears in small quantities from the 160s, but only in any quantity in the third century. The sleeper wall produced a further two sherds of BB2 (G10:19). One sherd of possibly intrusive thirdcentury Nene Valley ware (G10:02) was associated with the west granary floor.

The structural evidence all points to this being the primary granary and therefore presumably Hadrianic in date. No trace of an underlying timber granary was identified comparable to the timber phase of the hospital. The small quantity of coarse pottery in the granary makeup deposits and pre-fort levels was consistent with this dating, being predominantly composed of the second-century grey ware vessels, found in clay layer F10:40 (context G10:35) and in the underlying pre-fort plough furrows (G10:36). The little-worn Trajanic coin of 103–111 from layer F10:40 (context G09:30) would also be consistent with a Hadrianic construction date and may provide a closer indication of the date of the primary granary.

None of the material from the east granary floor or sleeper wall can be regarded as deriving from sealed contexts. Similarly, the flagged floor in the west granary (G10:02) from which a single sherd of third-century Nene Valley ware derived, also yielded early modern pottery demonstrating that the thirdcentury sherd could be intrusive.

The granary entrances may have undergone a secondary remodelling, occasioned by the erection of the stone forehall (Building AO) along the north front of the principia and granary. Construction of this massive piered structure over the via principalis must have entailed the demolition of granary’s northern portico. From the surviving remains of the loading platforms it may also be inferred that both halves of the horrea were modified to become singleended structures, with the east granary now being entered from the north end only, whilst the west granary retained its south entrance, but lost its north one. Thus, whilst substantial elements of the base course of the north-east and south-west platforms remained (Fig.4.12), their south-east and north-west counterparts were only represented by stone spreads of robbing residue (G11:81; G08:16) in the appropriate positions and, in the case of the north-west platform, the trench (G08:39) cut to remove the facing stones enclosing the clay base of the platform (Fig. 4.13). Five, large, well-cut blocks, measuring 0.65–0.80m × 0.25–0.35m (height not recorded, but c.0.20 to judge from photographs) and very similar in form to those used for the granary steps, were incorporated in the masonry of one of the piers (G07:03) of the forehall (Fig. 4.14). It is tempting to interpret these blocks as representing the reuse of material from the northwest steps, only 6.00m from pier G07:03 (which was the nearest of any of the AO piers to that platform – Fig. 4.15). If correct this would not only imply that the removal of at least one of loading platforms occurred during the Roman period, rather than simply representing post-Roman robbing, but would also indicate that the demolition of the two loading platforms and the construction of the forehall were essentially contemporaneous, linked structural events. It should be noted however that if this is the case some means of entering the west granary at its north end must have been re-established later on when all access to the southern end of the building was blocked off by a row of timber buildings (see Chapter 6). Perhaps the original doorway was reopened and a simple set of wooden steps resting directly on the ground surface were installed at that point. Doorways may also have been inserted between the two halves of the building, if none existed previously.

FINDS

North-west loading steps robber trench

Architectural stonework: pier base (no. 23, G08:39)

Grid squares – AU: F08, F09, G08; AV: F11

Two small buildings, labelled AU and AV, were attached to the north- and south-west corners, respectively, of the granary. Certain structural relationships and features suggest the building of AU and AV may be connected with the remodelling of the horrea entrances and the construction of AO.

Building AU took the form of a small, rectangular room, measuring 5.20m north-south by 3.90m eastwest, and was tacked onto the north-western end of the granary (Figs 4.11, 4.16). Its floor (F08:17) was composed of small packed stones which showed some signs of wear. This was overlain by a rubble spread (F08:16) which may relate to the period after the building had gone out of use and reflect post-Roman disturbance. The excavation revealed the full length of the south and west walls, which survived up to two courses high and were evidently of one build (F08:06, 63, F09:33). The walls were 0.60m wide with no trace of foundations and may simply have been sleeper walls supporting a half-timbered superstructure. The south wall of Building AU (F08:63, F09:33) clearly butted up against the south face of granary buttress F08:12/G08:17 and presumably, therefore, also against the west wall of the granary (which served as the east wall of AU), although the exact relationship between these two walls has been obscured by robbing. The north wall of the building was shared with Forehall AO, forming the southern wall of that part of the forehall extending to the west of the granary. Only a one metre length of this wall’s masonry survived (F08:13), the remainder having been robbed out (F08:51), but, at 0.75m broad and set on rubble foundations 1.00m wide (F08:61, G08:43), it was clearly more substantially built than the south and west walls of AU. Wall F08:13 was probably therefore integral to Building AO rather than AU, implying the construction of AU was subsequent to that of the forehall. In effect Building AU was created simply by building its western and southern walls in the preexisting corner formed by the junction of the granary and the forehall.

Figure 4.12: Granary SW loading steps, seen from the north in 1977, showing the rebate for the next step clearly. Fragments of the west wall of Building AV can be discerned but are not yet fully exposed.

Figure 4.14: The piers of the forehall (AO) from the east, in 1983. Note the location of the robbed out piers (G07:08, G07:12) and the long blocks, incorporated in the pier (G07:03), in the background which may have been reused from the NW loading steps of the granary.

Figure 4.15: The north end of the granary and the forehall seen in 1983. Note the proximity to forehall pier (G07:03) to the robbed out NW loading steps.

Figure 4.16: Building AU at the NW corner of the granary viewed from the north in 1983. The remains of the drying/ malting kiln are also visible.

A second small rectangular building, labelled AV, was built at the south-west corner of the granary (Figs 4.11, 4.17). Slight traces of the north (F11:64) and east (F11:65, 81) walls of this building run across and appear to be set on a layer of cobbling which was identified by the excavators as the primary road surface (F11:73), immediately to the south and west of the granary. The north-east corner of AV sat in the angle formed by the granary’s south wall and the west face of the south-west loading platform, butting up against these pre-existing structures. The north wall of AV must have incorporated the westernmost buttress on the granary south wall. There was no trace of the south wall of AV, which had presumably been entirely removed by later activity. However, AV clearly extended southwards beyond the steps of the south-western entrance, though probably no further than the line of the existing granary portico. Similarly, no evidence for a western wall was recovered. It is possible that the east wall of the hospital was used for the purpose, with the north and south walls of AV butting directly up against it. If that was the case, the positioning of Building AV would have interrupted the line of the gutter (F10:50, F11:77), which ran alongside the hospital wall, and the building’s construction would therefore have to have been secondary to the erection of the stone hospital (Building 8 Phase 1). This would represent a useful piece of relative chronology, even though the two structural events need not have been separated by any great interval of time. However it is not certain that Building AV did extend right up to the hospital wall. It may conceivably have stopped short of the hospital east wall leaving sufficient space for the gutter to pass between. The west wall of AV could conceivably have been robbed in its entirety, like the south wall. Judging from the photographic record (Fig. 4.17) the gutter lining incorporated a couple of large, neatlysquared oblong blocks which resemble those used in the granary loading platforms. It is conceivable that these blocks derived from the redundant south-east loading platform and were reused to line the gutter alongside the hospital wall at this time. However they appear to lack the distinctive rebates present on the surviving in situ blocks so it is impossible to verify now whether this was their original purpose.

Figure 4.17: The remains of Building AV viewed from the west in 1983, comprising fragments of the building’s north and east walls next to the SW corner of the granary. Note the gutter alongside the east wall of the hospital.

The relationship between AV and the adjacent road surfaces implies that the building was broadly contemporary with the initial phase of the stone hospital (Building 8 Phase 1). The later phases of the hospital (Building 8 Phases 2–4) were associated with a series of rutted road surfaces which overlaid the original east wing of the hospital and extended to the east of that building into the area occupied by AV. Although the stratigraphic relationship between the fragments of wall belonging to Building AV and the rutted road surfaces is not explicitly documented in the site records, the fact that AV was not recognised when these surfaces were investigated in 1977 and indeed was not identified until the 1980–81 season strongly implies that the remains of the building underlay the later road surfaces and predated the hospital building phases with which those layers were associated. Furthermore, the southern fragment of AV’s east wall (F11:81) was recorded as overlying the lowest layer of metalling noted in the area south of the granary (F11:82 – described as ‘road foundation?’). The next layer of cobbling was interpreted by Daniels s the primary road surface (F11:73 = F11:53?). The relationship of F11:73 to the surviving walls of AV is, again, not explicitly defined in the context records, but examination of the site plans and photographs suggests the walls were probably set on this surface.

Figure 4.18: The remains of the wall closing off the south end of Alley 8 (Building AW), plus the drains and surfaces in the area to the south, at 1:200.

Only three sherds of pottery were recovered from Building AU. This includes a sherd of BB2, and two sherds of samian, one of which was Antonine (F08:17).

The remodelling of the granary entrances, which converted the twin granaries into single-ended structures, facing in opposite directions, formed part of a larger phase of building work in the central range that included the construction of the forehall and the stone hospital (Building 8 Phase 1). The alterations to the granary may have been intended to separate the stored supplies of the two main components of the garrison. This remodelling was probably also associated with the addition of small buildings (AU and AV) at the north- and south-west corners, respectively, of the double granary, which was perhaps designed to establish tighter control over the issuance of supplies to the troops.

Thus the six infantry centuries of the equitate cohort, which were lodged in the northern part of the fort (praetentura), were probably provisioned from the north-facing, east granary, whilst the cavalry turmae, which were evidently housed with their horses in the four stable-barracks in the southern part of the fort (retentura), were presumably supplied from the south-facing, west granary.

The excavators cautiously, but plausibly, interpreted Building AU as a quartermaster’s office, and a similar identification might apply to AV, with the implication that each half of the granary was provided with an attendant office intended to house an official monitoring deliveries to and issuance of supplies from the horrea. On this basis, Building AV, which directly abutted the south-west platform, could have served the west granary, whilst AU might relate to the east granary. Physically locating officials close to the granary entrances in this way would have provided tighter control over access to that building. The construction of AU and AV may therefore be seen as contemporary episodes forming part of the wider reconstruction of the granary, rather than representing two consecutive phases, as suggested in the Tyne and Wear Museums report (Hodgson 2003, 174). There it was argued that AU may have replaced AV when the east wing of the hospital was demolished and replaced by a thoroughfare, which also impinged on the area of AV. This possibility cannot be excluded, and it must be admitted that both suggestions are ultimately based on interpretations of the likely causal sequence of events.

Figure 4.19: The south end of the granary (Phases 3 and 4) showing the south wall of AW and the surrounding storm drains F10:23/F11:63/G11:51 and G11:07/H12:33, at 1:200. Also shown for reference are the flagged floors of the third-century timber buildings in this area.

Grid squares: G10, G11, H08, H09, H10, H11

A further major alteration to the granary is signified by the construction of a wall blocking off the southern end of the alley to the east of the building (alley 8). Much remains uncertain regarding the form of this remodelling, as its remains had largely been robbed out or removed by later activity. However, several features suggest that it involved more than simply closing off the end of the alley and may have entailed enclosing and roofing over the alley space to convert it into a third chamber for the granary. This structure was labelled Building AW by the excavators.

The southern end of the alley was blocked off by a wall which continued the line of the granary south wall (Figs 4.18, 4.19). This blocking wall was represented by a pitched, rubble foundation (G11:91, H11:78), up to 1.3m wide, overlain by yellow clay, which abutted the most southerly buttress of the granary east wall. The superstructure of this wall has been entirely removed by robber trench H11:71, which, in so doing, has also obscured the original relationship between the wall and the adjacent surfaces. However, in the ‘Building notes’ compiled following the 1983–1984 seasons it is stated that the foundation was clearly added against the most southerly buttress of the granary east wall, and was therefore a secondary feature. On the south side of the robber trench, roughly midway along its length, the remains of a possible buttress (G11:46) survived. Site plan P278 also shows a very similarly shaped, rectangular depression, 1.5m further east, perhaps marking the outline of a partially excavated robber trench for another buttress, although this is not identified in the context records. Robber trench H11:71 also apparently cut the northern edge of a large shallow pit (G11:92, H11:77), which itself cut into the layer of dark brown soil interspersed with small stones (G11:86, H11:74) that covered much of the area south of the alley (this was the lowest level investigated in this area in 1983). The pit fill was not fully identified in the context records, but would appear to correspond to a spread of cobbles and flags (G11:48, H11:57) which site plans and associated sketches from the 1981 season show covered this same area. Indeed the ‘pit’ uncovered in 1983 may simply represent the feature left by the excavation and removal of the cobbles and flags in the 1981 season. The cobbles and flags were, in turn, covered by a layer of coal dust and chippings (G11:47, H11:56a). Two further patches of well-worn flagstones (G11:84/ H11:72; G11:85/H11:73), which may be contemporary with this phase, were revealed further south, close to the south-west corner of the principia. These were explicitly interpreted as deliberately laid surfaces rather than random scatters of flagstones.

Table 4.02: Equivalence table of surfaces in Alley 8

| Alley 8 surfaces | Context numbers |

| Alley surface 4 | G10:10, G11:42?, H09:14, H09:46 (patch of resurfacing), H10:26, H11:32 |

| Alley surface 3 | G10:39, G11:87 (?), H08:46, H09:15/47, H10:27, H11:35 |

| Alley surface 2 | G11:94, H10:47, H11:76 |

| Alley surface 1 | H11:75 |

Up to four clay and cobbled surfaces were laid in the alley (see equivalence table 4.02), although the relationships and equivalences between the lower examples were not always clearly expressed in the site records. CMD noted that these surfaces looked weathered, but not worn, and the context descriptions are indeed more characteristic of road metalling rather than internal building floors which would imply the area served as an enclosed yard. A drain or gutter (H08:18, 19, H09:49, H10:46, H11:10, H12:10), which was probably a primary feature, was constructed beside the west wall of the principia and ran the full length of the alley. This was comprised two lines of thin slabs set vertically on edge, the eastern line being laid right up against the west wall of the principia. The drain fill (H08:21, H09:48, H10:48, H11:34, H12:11) was not fully described, but included rubble blocks in its uppermost level, perhaps representing demolition debris from the adjacent buildings. None of the surfaces in Alley 8/Building AW extended over the remains of the granary’s east wall which would imply that the wall remained standing and formed the eastern edge of that area throughout the period represented by the four clay and cobbled surfaces, whether the area functioned as an alley, an enclosed yard or a covered storehouse.

There were no definite remains of a corresponding blocking wall at the north end of the alley, but a modern drain (H08:08/09) had removed most of the stratigraphic evidence at precisely this point. The Building Notes indicate that CMD did recollect finding a tiny fragment of a wall somewhere in this area. This may be a reference to a short section of the granary north wall (H08:31), found here, or to the scatter of dressed facing stones, which are depicted clearly on site plan P244, clustered on either side of the modern drain, but not identified as a separate context.

Further evidence is provided by presence of a series of drains to the south of the granary. Most intriguing was a very substantial drain (G11:07, H12:33; TWM 7687), as much as 1.0m wide at the top, which was constructed using thin sloping slabs to form the side walls and covered by similar flat slabs. This appeared to run from the southern end of the east granary past the south west corner of the principia and thence down the via decumana and perhaps exited the fort through the south gate where a similarly constructed drain was encountered. It appeared to cut another drain (G11:49; TWM 7215), which was only 0.15m wide and some 2.50m in length, its side walls being composed of small stone blocks, of which only a single course survived (Figs 4.19, 4.20). A further branch of the main drain joined the previously described section just south of the granary. This branch extended around the south end of the granary, starting from a point not quite half way along the length of the building (F10:23, F11:63, G11:51). Virtually all its side walling and cover slabs had been robbed out at some point. The position of drain G11:07 in relation to the granary is puzzling. It certainly ran right up to the south end of the building. However the drain could not easily have collected rainwater falling from the roof of the primary granary. It terminates at a point immediately west of the granary’s east wall, opposite the line of flagging (G11:56) which separates that wall and the most easterly of the sleeper walls (G08:30, G09:05, G10:24, G11:57, H08:24, H09:19) in the east granary. The position of the drain instead suggests that there was a roof valley between the two walls and further implies that the internal wall was rebuilt to form a partition wall supporting one side of the roof valley.

Figure 4.20: Drains G11:49 (foreground) and G11:07/51 (mid left to bottom right) at the south-east corner of the granary, viewed in 1983.

The evidence regarding the form and function of the structures grouped together under the label ‘Building AW’ is somewhat contradictory and was not fully resolved by the excavators. Charles Daniels considered it unlikely that the alley was incorporated within the granary, but other comments in the postexcavation archive imply that AW was reckoned to be a building of some sort. Several pieces of evidence need to be reconciled. Both the extent and the location occupied by the cobbles and flags (G11:48), which were set in shallow pit G11:92, would be consistent with their interpretation as foundations for another set of loading steps giving access to an elevated granary floor. However the absence of any other evidence for such raised internal flooring within the alleyway north of the cross wall implies that the area never formed part of a conventional granary structure (even if some caution may be merited in this respect, bearing in mind how little survived of the sleeper walls and associated flagging in the west granary). Indeed the surfaces present in the alleyway would be more consistent with an open yard rather than a roofed structure. Yet the clear evidence that the wall across the southern end of the alley was furnished with one or perhaps two buttresses provides decisive confirmation that the wall formed part of an enlarged structure, integrated to a significant degree with the existing granary (though not necessarily performing an identical function), and was not intended merely to close off access to the alley. Accordingly a third storehouse chamber must be envisaged, but one equipped with a cobbled hard-standing, rather than an elevated floor, and presumably intended to house non-perishable items such as tools, carts, or stores which could be hung from internal roof beams. In these circumstances the spread of cobbles and flagging south of the cross wall is most plausibly interpreted as a metalled approach to an entrance through the wall, all trace of the actual threshold having been robbed away with the rest of the wall’s masonry. It is uncertain whether there was a wall across the north end of the alley. A wall may not have been necessary here in any case since the forehall to a large degree closed off access to the area.

Finally, the location of drain G11:07 also points to a significant remodelling of the granary, which not only involved enclosing and roofing over the alley, but conceivably also heightening the eastern sleeper wall (G08:30) to serve as the new east wall for the pre-existing granary chambers, whilst the granary’s former east wall now served as the west wall of a chamber enclosing the former alley. Between the two walls an eave-level valley presumably discharged rainwater into drain G11:07 at the south end of the building. This valley would have covered a narrow space separating the old and new chambers, an arrangement which may be paralleled at Housesteads where there appears to have been a similar enclosed space between the two third-century horrea which replaced the double-width Hadrianic granary. It must be admitted that there is no evidence that the former sleeper wall was strengthened in any way to perform its new function, but it is otherwise difficult to explain the positioning of the drain which was evidently one of the principal stormwater channels in the fort.

FINDS

Building AW – S wall robber trench

Copper alloy: loop (no. 375, H11:71)

Drain F10:23/F11:63/G11:51 south and west of the granary

Coin: ‘Constantius II’, 353+ (no. 207, G11:51)

The area south of Building AW

SOIL G11:86/H11:74

Dark brown soil G11:86/H11:74 contained a more sizeable combined group than other contexts in this area, which could be either late second or third century in date (all the coarse ware of G11:86 is BB2 and allied fabric, but there is too little material from this context on its own for this to be significant).

FLAGGING G11:84/H11:72

Flagging H11:72 was associated a small group of only a few sherds and therefore of limited use.

Alley 8

ALLEY 8 SURFACE 2

There was a single sherd of mid- to late Antonine samian (H11:76).

RUBBLE OVER ALLEY 8 SURFACE 3

There were only a few sherds of pottery in the material over alley surface 3 H09:15, including third-century BB2, and an intrusive Huntcliff-type calcite-gritted ware rim (H09:16).

ALLEY 8 SURFACE 4

The uppermost surface produced reduced Crambeck ware of the late third century or later (H09:14, H10:26).

Alley 9 and the drains south of the granary

DRAIN F10:23/F11:63/G11:51 SOUTH AND WEST OF THE GRANARY

The substantial drain extending around the west and south sides of the granary contained a large group of pottery of third-century date from its northern end, in Alley 9, with almost all of the coarse ware made up of sherds of BB2 and allied fabrics, including a G151 rim (F10:23). Nene Valley ware made up the fine wares. There were very few sherds of pottery in the upper fill in this stretch (F10:18), and nothing later in date than in the lower fill.

Further south, where it curved round to run along the south side of the granary, cutting the via quintana, three sherds of Antonine samian and a Colchester mortarium rim dated 130–70 were recovered from the drain (F11:63), whilst the section continuing eastwards along the south side of the granary contained a few sherds of BB2 and allied fabrics of third-century date (G11:51).

DRAIN G11:49 IN THE VIA QUINTANA (ROAD 3)

The north-south aligned drain G11:49, south of the granary, contained a few sherds of BB2, plus Nene Valley ware of third-century date.

DRAIN G11:07/H12:33

Much of the material was made up of BB2 and allied fabrics, with a single sherd of Crambeck reduced ware and a BB1 flanged bowl providing a late third century date (G11:07).

The short stretch of drain G11:49 (TWM 7215) was assigned to Period 1 or 2 by the 1997–8 excavators who re-exposed the feature. It was presumed to have continued northward to the south wall of the granary, following much the same course as the north end of drain G11:07 (Hodgson 2003, 174). The much more substantial drain which ran around the south end of the granary and continued past the southwest corner of the principia, was assigned to Period 2/3 (ibid., 175). It was suggested that the northern end of G11:49/7215 running south from the granary was recut and realigned at this time to feed into the new drain, though it is so much wider and deeper that it should surely be treated essentially as a new structure (G11:07).

The sequence of these drains was never properly established during the Daniels excavations and some key stratigraphic relationships are unclear. F10:23/F11:63/G11:51 certainly ran through the area of Building AV and most likely post-dated it (the surviving fragments of the building’s north and east walls do not continue across the line of the drain and may have been cut by it). This drain also traversed the area covered by the south portico and it is likely this had already been dismantled by the time the drain was dug. The portico would not have been needed once all access to the southern end of the granary was closed off, which may have coincided with the demolition of AV. Indeed the drain’s most plausible interpretation is as a kind of ring ditch, collecting runoff from the truncated granary roof and helping to keep the area around the lower, southern end of the building relatively dry. The northern end of G11:07 extending up to the granary south wall would have completed this ‘ring ditch’. Although it may have been constructed before the three timber buildings, Q, R and AX(S) were erected, the latter do not impinge on the ‘ring ditch’ drain and it is likely that it was still operating during at least part of their lifetime (see Chapter 6 for a description of the timber buildings). Indeed it would have been essential in helping to keep the north ends of these structures dry, preventing them from being flooded by runoff from the granary roof and it is not impossible that it formed part of the same structural programme.

The location of drain G11:49 corresponded to the narrow alley between the two easternmost timber buildings, R and AX(S). Its function may have been to drain rainwater from that alley into the ring ditch. Unfortunately the stratigraphy relating to this drain is very uncertain. It appears in site plans of 1981 and the subsequent plans and photos of 1983 standing proud, set on top of earlier road surfaces. Hence it was assigned to Period 1/2 in 1997–8. It was not recorded in 1977, but it lay on the periphery of that year’s excavation site to the east of timber building R where there was relatively little investigation and the layers described in the site notebooks are very difficult to interpret.

In contrast to F10:23/F11:63/G11:51 and G11:49, which apparently respected the positioning of the timber buildings, the course of drain G11:07/H12:33, running south-eastwards from the granary past the south-west corner of the principia, cut diagonally across the northern half of the easternmost timber building. Whereas F10:23/F11:63/G11:51 was devoid of cover slabs when first exposed, those of G11:07/ H12:33 remained in situ at the time of initial excavation in 1981. The site plans drawn at that stage, plus photographs taken in 1977 when the drain was first exposed at the edge of the Site 6 excavation area, but not otherwise recorded, show that stone surfaces which can now be associated with timber building AX(S) did not then extend over the drain cover slabs, though they did survive on either side. It is possible that the cover slabs were incorporated to form part of the building’s stone floor or that the overlying floor surface had already been removed by the excavators, perhaps inadvertently, to expose the slabs. However it is also conceivable that the drain was constructed across the site of the timber building after the latter had gone out of use, perhaps in the late third century, cutting through the building’s floor.

Thus ring ditch F10:23/F11:63/G11:51/G11:07 (north) may been constructed in the early third century (Period 3) or perhaps somewhat later in that century, in association with the timber buildings of Row 20 (Period 4), to which stage drain G11:49 can also be assigned. G11:07/H12:33 may have been associated with the ring ditch from the start, designed to carry away the collected stormwater, but the possibility that it was a later modification inserted after the abandonment of all or part of Row 20 cannot be excluded. The inclusion of some late third century pottery in that drain would be consistent with the latter hypothesis, but the quantity is small – a single sherd of Crambeck reduced ware and a BB1 flanged bowl – and it could simply represent material which found its way into the drain later in its life. The overall character of that assemblage, being dominated by BB2 and allied fabrics, would imply a date earlier in the third-century and, on balance, suggests that G11:07/ H12:33 was constructed at much the same time as F10:23/F11:63/G11:51 and may have been an integral component of the latter.

The traces of a possible corn-drying or -malting kiln (F08:05) were identified tucked in the angle created by the west side of AU and south-west corner of AO (Figs 4.21, 4.22). The kiln took the form of a squarish, clay platform, with two parallel flue channels, orientated roughly north-south, set in it. The easterly of the two flues was the better preserved, comprising two facing lines of flat, roughly worked stones, roughly parallel to the west wall of AU (F08:06) to the east. The two walls were c.0.40m apart and 2.20m long, although only seven facing blocks remained in situ, three belonging to the western ‘wall’, at the southern end of the kiln, and four at the northern end belonging to the east wall (B91/2a–4a, B93/36–37). The north end of the structure, where the two walls may originally have joined, must have abutted the south wall of the forehall AO (F08:13/58). The structure sat on a layer of dark-brown clay with traces of burning (F08:39). The strip of clay and tile between the two walls was heavily burnt, with traces of coal also present, particularly towards the north end. In the case of the western flue, masonry side walls did not survive, but the channel in the clay base shows up clearly as a darker line on photographs (cf. Fig 4.23 here). It was of similar length and form to the east flue, and there was much reddening of the clay on the west side of the channel. A black deposit, rich in coal and ash, covered the stones of surface F08:18 outside the southern end of the kiln and was assumed to represent the stoking area. Within the very southern end of the eastern flue there was a circular hole (F08:54), 0.10m wide, which was interpreted as a possible vent or crucible, though it is unclear precisely how it could have served either function. The hole could not be excavated to its full depth, which was clearly in excess of 0.25m. Despite the apparently deliberate and precise placing of the hole right within the southern end of one of the flues, it is possible that it simply represents a much later, post-Roman post hole.

Only a single course of the side walls survived and the form of the kiln superstructure is therefore very uncertain, though it may be presumed that the walls originally stood somewhat higher and were perhaps covered by the same clay upon which the structure was bedded. One of the wall stones had a groove cut in, perhaps for an iron shelf, but the block may well have been reused. Along the western limit of the clay spread F08:39, two squarish post-holes (F08:27–28), respectively 0.27m and 0.36m wide and roughly 1.00m apart, may have held timbers supporting a lean-to roof over the kiln, giving the whole structure an east-west dimension of c.2.50m. The northern of the two post settings (F08:27) incorporated a quernstone (F08:29; see Chapter 25) amongst its packing- or prop-stones. The form of the kiln remains and their proximity to the granary suggest that it was used as a drying platform, perhaps to malt barley or wheat required for the production of beer as an alternative to the garrison’s wine ration. Although no carbonised grain was noted in excavation, no environmental sampling was undertaken here. Certainly there is no mention in the site records of any metalworking slag being found, nor does the masonry of the side walls appear to have been subjected to the kind of intense heat which would be expected if the structure had been used for metal working or processing. It was uncertain whether this represented a single structure with twin flues or perhaps two successive single-flue ovens or kilns, with the eastern one succeeding the western example, however doubled flued structures are certainly known on Romano-British agricultural sites. Comparison with corn dryers uncovered at such sites (cf. For example Morris 1979, 170, fig.13 c–d – Hambledon) suggests that the east and west sides of the structure may have extended further southwards than is now apparent, to enclose a single stoking area, from where the hot air could flow along both flues.

The kiln superstructure produced only 0.024kg of pottery, mostly BB2 cooking pot sherds (F08:05). The clay base produced the scattered sherds of the lower part of a burnt reduced ware cooking pot, and two sherds of a storage jar, possibly of third-century date (F08:39). The fill of the post-hole (F08:27) included three sherds from a BB1 plain-rimmed dish and a sherd of decorated samian dated 160–200 (no. D21/ S14).

The walls of the granary were extensively robbed. This was probably a post-Roman event. Two of the robber trenches contain early modern material – clay pipes and early Black ware providing a late sixteenthor early-seventeenth century terminus post quem. The pattern of robbing has two slightly puzzling elements. Firstly, the masonry of the eastern sleeper wall in the east granary masonry displays exceptional degree of preservation, with one or two courses of the wall surviving along virtually its entire length. As described above, this wall may have played a more significant structural role later in the life of the building, perhaps being raised to support one side of a roof valley, rather than functioning simply as a sleeper wall supporting the elevated floor. Nevertheless it is difficult to explain why this should be so much better preserved than the other sleeper walls or the original outer walls of the building. Secondly, the masonry belonging to several walls which were otherwise entirely robbed out, plus adjacent strips of flagging, did survive in the centre of the building, forming a band of better-survival extending across the width of the granary. Was this area covered by a building when the main phase of stone-robbing was underway, rendering it inaccessible to those quarrying the stone?

FINDS

East granary flagged floor – robbed areas

Coin: ‘Gallienus’, 260+ (no. 146, G09:14)

Flint: blade (no. 15, G10:18)

East wall robber trench

Samian stamp: 140–70? (no. S19, H09:18)

South wall robber trench

Mortarium stamp: 110–40 (no. 37, F11:07)

Glass: window (no. 42, F11:07)

The demolition material over the granary remains contained relatively little pottery, but there was one sherd of late third century or later Crambeck reduced ware (G09:07). The robber trenches produced about 40 sherds of pottery, mostly dating to the third century, but including four body sherds of calcite-gritted ware of the late third or later.

Horrea have perhaps been subject to more extensive and detailed analysis than any other type of building within Roman forts, with the possible exception of barrack blocks. Major surveys covering, respectively, Roman horrea in general and stone-built military granaries in Britain, in particular, have been compiled by Rickman (1971) and Gentry (1976). More recently, the evidence relating to the building type has been reexamined by Wilmott (1997, 132–41), in the light of the excavation results from the especially well-preserved pair of horrea at Birdoswald. That study placed particular emphasis on assembling the data to enable the pictorial reconstruction of the two buildings. In contrast, the poor preservation of the Wallsend horreum inevitably means its remains are much less informative, although this is to some extent balanced by the fact that its entire area was excavated. The following discussion provides comparative analysis of the building and its various structural features in the context of similar examples, especially from the northern frontier.

The provision of granaries in auxiliary forts typically conformed to three basic patterns, a single granary, a pair of separate single granaries (Fig. 4.24) or a conjoined double granary (Fig. 4.25), with Wallsend falling into the last category. Double granaries were less prevalent than pairs of separate horrea, but they were not uncommon. In some cases these structures were divided midway along by a wall running across the width of the building, as at Birrens, for example, which was also furnished with two single granaries (cf. Gentry 1976, 60–62, fig. 6; Christison 1896). More often the partition wall ran down the length of the building, as was the case at Bar Hill, Brecon Gaer, Hardknott, Lyne and Slack, as well as Wallsend itself (Gentry 1976, 58, 62, 80–81, 84–5, 90; Charlesworth 1963 and Bidwell et al 1999, 39–41 (Hardknott)). Perhaps most significantly with respect to Wallsend, examples of this type are found at the neighbouring forts of Benwell and South Shields (Fig. 4.25), the former dated by its dedicatory inscription (RIB 1340) to 122–126, whilst the latter was associated with the Antonine fort (Gentry 1976, 59, 92; Simpson and Richmond 1941, 17–19; Dore and Gillam 1979, 29–32, fig. 9). Indeed they seem to be characteristic of the Tyneside forts, whereas the next two forts along the line of the Wall, Rudchester and Haltonchesters, both appear to have contained a single granary in their primary, Hadrianic form (Gentry 1976, 80, 90; Dore 2010, 9–14). The Benwell granary was substantially larger than Wallsend’s, but it was relatively similar in overall proportions, as reflected in the ratio of its length to width. It is also worth noting that some single granaries, such as the Hadrianic structure at Housesteads, resembled a double granary in overall proportions, but were divided into two aisles by a row of piers rather than a longitudinal spine wall (Crow 2004, 56). Table 4.03 compares the overall dimensions and ratio of length to width of the most closely comparable of these horrea.

The variation in scale of granary provision in forts may be assumed to reflect the anticipated food storage requirements of the garrison, which in turn was presumably a consequence of the size and type of unit(s) present. In some cases further granaries appear to have been added, perhaps in response to an increase in the size of the garrison. It is tempting to suppose that the decision to erect a double granary instead of two single horrea was taken when there was judged to be insufficient space for a pair of buildings. However pairs of freestanding granaries could be very closely spaced indeed (Fig. 4.24). Thus, the two exceptionally well-preserved granaries at Corbridge, were positioned so close to one another that their buttresses were touching in places though they were demonstrably separate buildings (cf. Dore 1989, 5–7; Gentry 1976, 72–5). The same cannot be said in some other instances where it is unclear whether the horrea should be classified as twin granaries or a double granary. In the case of Templeborough, for example, which Gentry (1976, 93–4) categorises as a double horreum, a flagged drain ran between the two halves of the building, each of which was furnished with its own side wall, implying they were roofed separately. This arrangement of separate side walls is paralleled in the two double granaries revealed at High Rochester in the mid-nineteenth century and was essentially the same as that adopted in the second phase of the Housesteads horreum, when distinct north and south granaries were apparently created by the construction of longitudinal partition walls on either side of the primary, central row of piers (Crow 2004, 56–7). A second longitudinal partition wall was added in the double granary at Hardknott, resulting in a similar layout (Charlesworth 1963, 148, Gentry 1976, 81). A puzzling feature at Housesteads (and at Hardknott for that matter) is the lack of a drain between the north and south granaries to collect and carry away rainwater running off the roof eaves, or even of any opening at the east end of intervening passage to allow the water to escape and thereby prevent ponding. Perhaps the two longitudinal walls were not in fact the side walls of independent buildings, but were simply intended to support a combined upper floor spanning the full width of the horreum, with the weight of the roof above that still being carried by the central piers. This may have appeared preferable to tying the upper floor joists into the piers as well. The piers would in that case only have been dismantled when the northern part of the building was abandoned, perhaps during the third century.

Table 4.03: Double granaries – overall dimensions and ratio of length to width

| Fort | Overall dimensions (after Gentry 1976, except Wallsend) | Ratio of length:width |

| Wallsend | 26.00m × 11.40m | 2.28:1 |

| Benwell | 45.72m (max) × 18.29m; 34.75m (min) × 18.29m | 2.5:1 |

| South Shields | 22.86m × 15.24m | 1.5:1 |

| Brecon Gaer | 29.26m × 14.00m | 2.09:1 |

| Housesteads | 25.60m × 14.50m | 1.765:1 |

| Hardknott | 16.45m × 13.48m | 1.22:1 |

The problems faced in attempting to understand the form of the Housesteads horreum – one of the very best preserved on the northern frontier – only serves to emphasise the limitations of the evidence when only an outline ground plan can be retrieved, as at Wallsend. However the degree of variety evident from the foregoing might imply that localised similarities in form – as typified by the adoption of the double granary in Hadrianic/Antonine forts on Tyneside – could reflect accepted ideas of what constituted a properly laid out castra, within a particular military community or cluster of adjacent communities. There was plenty of space to construct a pair of separate granaries at Wallsend, for example, if the fort builders had believed it appropriate to do so. The same appears to have been true at South Shields. Indeed the close resemblance of the overall plans of Wallsend and South Shields, despite the three or four decades separating the initial construction of the two forts, has been noted elsewhere (Bidwell and Speak 1994, 18).

In his analysis of the height and architectural form of the forehall, Hodgson (2003, 180–81) considered the relationship of that building to the granary and principia which it fronted and the implications for the form of the granary itself. He concluded that the height of the forehall roof must have been determined by and have matched the height of the pre-existing granary and principia forecourt roofs. Based on the building’s likely proportions, given the known width of its arched openings, Hodgson estimated that the forehall, and by implication the granary, must have had an absolute minimum eaves height of 6m, with 7–8m being more likely. This would make the granary two storeys high, probably spanned by a single overall roof which was later extended forward to connect with the slope of the forehall roof. This in turn accords with more recent thinking regarding the height and overall mass of granaries, the evidence for two storey horrea, as a whole, having been reviewed by Wilmott, with particular reference to the two Severan examples at Birdoswald (1997, 137). Thus, the possibility that the aisled horreum at Housesteads had an upper storey has been noted, based on the solidity of its external walls and its overall proportions (ibid; Crow 2004, 56, fig. 30). Similarly the likelihood that the Severan east granary at Corbridge had two storeys has long been acknowledged, on the evidence of the row of seven large pillar or column bases running down its central axis (Richmond and Gillam 1950, 157; Gentry 1976, 75; Dore 1989, 5; see Fig. 4.24 here). Moreover civil and commercial horrea standing to two storeys in height have survived elsewhere in the Roman world, at Rome, Ostia and Trier, for example (Rickman 1971; Eiden 1949; Wilmott 1997, 137.)

The two halves of the Wallsend granary differed in their layout and construction in a number of ways, but this is not unparalleled. Some of these differences were relatively minor, for example the number of buttresses along their long external faces – nine and ten for the east and west granaries respectively. Much more significant is the different form taken by the internal floors in the two halves of the building, with the sleeper walls which supported an elevated floor in the east granary being laid directly on the ground surface whereas a substantial, carefully constructed clay and stone raft or platform was laid down in the west granary. The raft was in turn surmounted by flagging and sleeper walls which supported the west granary floor (see Figs 4.03 and 4.04). Such stone and clay platforms, forming a raised, solid floor base, were not uncommon in Roman fort granaries. At Haltonchesters the raft consisted of broken limestone overlain by a layer of stiff yellow clay bounded by a stone kerb one or two courses high (Dore 2010, 9). At Benwell too, a massive base of yellow clay and pitched stone was recognised in the southern part of the building (Simpson and Richmond 1941, 19; Gentry 1976, 59; Holbrook 1991). Solid floors of flagstones were laid on the clay and stone base, both at Benwell and at Haltonchesters, with a network of sleeper walls, surviving up to three courses high, being erected on top of the flagging in the latter case. No traces of equivalent sleeper walling were found sitting on the flagged floor at Benwell. Instead the foundations of eleven transverse sleeper walls, situated at intervals of 0.5m to 1.6m, were identified further north, beyond a transverse partition wall, where the clay-bonded rubble platform was not present. The transverse partition was located some 15m from the building’s south wall, hence perhaps roughly a third of the way along the granary, assuming that the latter extended northward, more or less the full distance to the edge of the via principalis, in which case the building would be approximately 46m long (or perhaps c. 43.5m if there was a portico at the north end as well as the south). Like the sleeper walls the partition was only seen in the trench for a gas main cut through the eastern half of the granary in 1990 and it is unclear whether the west granary was similarly subdivided and whether there were other partitions further north in the unexcavated parts of the building. In other cases raised floors were converted to solid ones either by infilling the ventilation channels, demolishing the sleeper walls or removing pilae and laying new flagged floors. Thus, around the mid-third century, the sleeper walls in the two granaries at Birdoswald were partially removed and infilled to create a solid floor at the western end of the north granary and a solid, though partially ventilated floor in the west-centre of the southern granary (Wilmott 1997, 122–26, 136, fig. 91). The alteration of raised floors to solid ones was also recognised at South Shields, where some of the supply base granaries were converted to barracks c. 300 (Bidwell and Speak 1994, 35, and 43–4 for later floor replacements). Also probably of late Roman date were the changes to the western half of the south granary at Housesteads (Crow 2004, 95), where the stone pilae were removed and a flagged floor laid on the interior ground surface, again perhaps associated with the conversion of this part of the building to living accommodation (the eastern half of the granary probably retained its raised floor accessed by a new stepped east entrance).

By comparison, the Wallsend granary appears relatively simple with no evidence for partitions other than the longitudinal one dividing the building into two halves but two different types of flooring were recognised. As at Haltonchesters there was evidence that a network of sleeper walls was constructed on top of the clay and rubble base in the west granary, however it is noteworthy that this walling survived only in a very fragmentary state in one small area. It could quite easily have been entirely destroyed and the 1983 excavators were in fact unaware of its existence following its removal in 1981. By analogy it is not inconceivable that a system of sleeper walls was originally set on the stone platform in the Benwell granary and were later removed either as a result of later modifications or post-Roman robbing. The level of the flagged surface over the clay and rubble base at Benwell was as much as 0.5m above the top of the sleeper wall foundations in the adjoining in part of the granary, but the floors at Corbridge and Birdoswald were significantly higher (1.1m in the case of the third phase of the Corbridge west granary for example, cf. Gentry 1976, 74).

The use of different sub-floors at Wallsend is somewhat puzzling. At Benwell, less perishable foodstuffs might have been kept in the parts of the building with solid flooring, assuming that was indeed their finished state, whereas grain was perhaps stored in the sections with the raised floors where it would be less vulnerable to damp. However it is more difficult to appreciate the reasoning behind the arrangements at Wallsend where both halves of the building had raised floors supported by sleeper walling, but only in the western half did this rest on a solid base. The benefits of a clay and stone platform of this kind, in terms of raising the entire floor substructure, keeping it clear of any flood damage caused by stormwater runoff and ponding, would appear to apply whatever was being stored above. There is no indication that the sleeper walls in the west granary were a later addition, constructed on top of an original, flagged, solid floor, since the flagging and the sleeper walls appear to have belonged to the same phase. They were set on top of the same soil and gravel bedding layer with the flagstones surrounding and abutting the base of walls rather than underlying them, just as the flagging in the east granary was laid between, but not beneath the sleeper walls there. Indeed, the solid base would have been too low to have served as a floor on its own as its upper surface must have lain well below the level at which entry was gained to the building via the broad stone steps positioned at either end. Perhaps the west side of the building was judged to be more exposed to storm water flooding and it was calculated that, if its raised floor had been supported on sleeper walls alone, the structure would have been at risk of water penetrating beneath the raised floor and ponding there. Construction of the solid raft lifted the whole western half the building clear of such ponding water.

The Wallsend granary preserved clear evidence with regard to the treatment of the narrow ends of the building, including the provision of porticos and the means by which access was gained, which adds significant information to our understanding of this building type. This relates both to the initial layout of the building and the changing pattern of provision over time as the orientation of the two halves of the granary was altered.

The Daniels excavations found the remains of a portico pier at the southern end and evidence for sets of steps at either end of both halves of the double granary, two of which had been completely robbed out. All trace of any door thresholds had of course been lost when the granary walls were demolished and robbed. Following completion of the excavations, the question of whether the building was originally single- or double-ended and, if the former, whether it faced north or south provoked considerable discussion, which is reflected in the research archive. This discussion revolved around the number and position of access steps, or ‘loading platforms’ as they were generally termed in the archive. Since there was no stratigraphic relationship between the steps and the remainder of the granary structure, as a result of later wall-robbing, the original layout and sequence of use of the loading platforms – and hence any change in the orientation of the building – could only be inferred on the basis of the relationship of the granary to adjacent structures and road surfaces. Thus it was tentatively suggested that there were originally two platforms on the southern side and perhaps none on the north, with the implication that grain wagons entered and left the fort through the south gate and porta quintana originally, rather than the west or east gates. The latter two gates are both situated to the north of Hadrian’s Wall and, it was therefore assumed, would not have been used for grain deliveries. Underlying this argument was the apparent absence of any evidence for a portico to the north of the building, which clearly pointed to a single-ended south-facing structure.

However, the discovery of the pier foundation pits to the north of the granary in 1997, in a demonstrably primary context, proved that the granary was indeed furnished with a northern portico and associated stepped entranceways in its initial phase. Moreover the near identical form, dimensions and construction of the surviving north-east and south-west steps, plus the manner in which their rounded lips and corners echo those of the surviving pier base on the south side of the building, strongly imply the granary was initially double-ended with both the eastern and western halves possessing entrances at either end of the building.

Three piers made up the porticos at either end of the Wallsend horreum, lying directly opposite the two side walls and the central longitudinal partition. Elsewhere, however, four piers or columns were more typically encountered. Best known is portico fronting the two principal granaries at Corbridge from the late second century onwards, composed of eight substantial columns, four in front of each building. Examples have also been found associated with the south faces of the double granaries at Benwell and South Shields and Templeborough, all somewhat better preserved than was the case at Wallsend. The portico at Benwell consisted of six piers constructed of two courses of small dressed stonework capped by a course with a rounded chamfer on which the pier proper or column would have sat. The three central bays were wider than those at either end of the façade (Simpson and Richmond 1941, 18, pl. V). Four piers were in evidence at South Shields, with square chamfered bases surviving in three cases (Richmond 1934, 93, pl. xiii fig. 1; Dore and Gillam 1979, 29–30, fig. 9). At Templeborough there were four columns along the south façade and a further seven small ones along the east side probably supporting a veranda lining the via principalis (Gentry 1976, 93–4). Elsewhere the evidence is more tenuous, with no remains of actual portico columns or piers surviving, but indications that they can be restored. Thus the wall forming the perimeter of a rectangular extension at the south end of the granary at Haltonchesters may have supported a portico around the edge of a loading platform (Dore 2010, 9–10, 86–9), as may the similar structures at either end of the two horrea at Gelligaer where the position of the individual piers or columns was perhaps indicated by the pattern of worn and unworn flagstones (Gentry 1976, 78). It would not be surprising either if a portico was set along the edge of the massive masonry platform measuring 9.75m by 3.05m attached to the south end of the granary at Rudchester, spanning its full width (Gentry 1976, 90). Indeed porticos may have been much more common than generally recognised, as the areas in front of granaries have not always been explored very extensively and in any case obvious traces of column bases might have been swept away by later remodelling or post-Roman robbing.