Priscilla Dean and Ben Wilson in Lois Weber’s Even As You and I, 1917.

AT THE TURN of the century, there was a word shocking to many Americans. That word was “novel.”1 The novel and the film were fictional, and thus untrue, and they shared an obsession with romance. Romance, as Puritans knew only too well, was simply a cloak for naked sex.

In case you think only bigoted farmers in the rural South felt this way, let me quote from Edward A. Ross, the leading sociologist of the Progressive era. In 1926 he declared that “conscienceless film producers and negligent parents” had allowed to be committed against children “one of the worst crimes on record.” Apart from the occasional sex film from which children were barred, as a publicity dodge to make adults anticipate something spicy, “children have been allowed to see everything which adults have had access to.”2

Ross blamed on the movies the fact that young people were more “sex-wise, sex-excited and sex-absorbed” than any previous generation. “Thanks to their premature exposure to stimulating films, their sex instincts were stirred into life years sooner than used to be the case with boys and girls from good homes.”

He accused producers of making hundreds of millions of dollars, yet of paying not the slightest concern to the effect of their films on children. “I fancy that if every juvenile movie habitué were to develop leprosy within ten years, most of the producers would still fight any movement to bar children from their shows. Never have we witnessed a more ruthless pursuit of gain.”3 (Now that the children have grown up and become grandparents themselves—often objecting strongly to what their grandchildren are watching—how many were corrupted?)

It is easy to laugh at the concern for the moral welfare of children in a distant era when the movies appear so harmless. But films then had a far stronger impact than they do today, when moving pictures are as available as tapwater. And parents had reasons for their concern, reasons which escape our eyes—partly because the films we see are often more heavily censored than the versions they saw at the time. Many have come down to us in 16mm prints prepared for home movie use by the Eastman Kodak Company, most were abridged from seven or more reels to five, and the cutting was done with an eye to the family audience. Anything remotely risqué was removed.

The most strenuous objections were made to The Wanderer (1925), an adaptation of the Old Testament story of the Prodigal Son, directed by Raoul Walsh. It was intended as a sequel to The Ten Commandments (1923), in which Cecil B. DeMille had used the Bible to provide censor-proof excuses for extremes of sex and violence.

At a hearing of the Committee on Education before the House of Representatives in 1926, Wilton Barrett, secretary to the National Board of Review, was asked if he approved of The Wanderer. Absolutely, he replied. His interrogator, Mr. Fletcher, had just seen the picture: “Mrs. Fletcher and I were very much interested in the reaction of the young people, when the draperies were drawn and he was with the woman, nude except for a few flowers.” (An exaggeration, of course!) “Their exclamations and observations were very interesting. And when he came out, fatigued, somewhat staggering, the next morning, after his experience with the woman through the night, their exclamations were again very interesting to observe; very audible were their exclamations. I was just wondering where you would begin to censor a picture of sex questionableness?”

Greta Nissen as the seductress in The Wanderer, 1926. (National Film Archive)

Mr. Barrett fell back on a quotation from Dr. Lovejoy Elliott to the effect that you cannot divorce a motion picture from the environment and training of the person attending it. “And it would be hard to tell where the motion picture was the stimulating influence and where it was environment and heredity.”4

Unusually, this moment survives in the otherwise heavily abridged 16mm version (nine reels to five), and while one can see what a mild bit of vamping it is by modern standards, one can also appreciate why it upset people at the time. A glamorous priestess, Tisha (Greta Nissen), ensnares the young man (William Collier, Jr.), and slave girls drape muslin around them. The film fades out on Tisha’s inviting expression and fades in the next morning as the young man, obviously exhausted, takes his departure. One can imagine a college audience sending it up with hoots of merriment.

But the big sex scene—even so sober a critic as Pare Lorentz described it as “one of the most salacious scenes ever put into a film”5—was cut very short indeed: “The temptress, barely covered by a leopard skin, receives the prodigal on a rose-strewn couch in no mild manner. Yet because the hero was chastened, punished and repented (in one short reel) this movie was hardly touched by the hands of the godly.”6

In any case, sex or no sex, The Wanderer was a flop with the public, and a sequel, The Lady of the Harem, made by the same team, lasted but a day at Loew’s New York.7

To modern eyes, the sex in American silent films is unbelievably tame. So it is in Victorian paintings, until you become aware of the symbolism, or view an Alma-Tadema, the DeMille of his day. But while the sex content of most regular releases was kept to one tenth of 1 percent, stronger stuff was available. Not on the open market, of course, but through the agency of bootleggers. Soft-core pornography could be purchased in 100-foot rolls for home movie projectors in the 1920s. The films tend to look innocuous and rather charming when seen today.8 In one, a girl in her bath sees a mouse, shrieks, and brings a man running in from the street. As she eyes him in alarm, he is transformed into a large version of the mouse that scared her. In another reel, schoolgirls play strip poker. The headmistress surprises the naked girls and announces, “Young ladies, may I remind you that this is a finishing school? And YOU ARE ALL FINISHED!”

The hard-core films were difficult to obtain then and difficult to see now. A few surviving examples going back to the birth of the cinema (and, I suspect, assisting at it) were included in a documentary called Ain’t Misbehaving (1974) made by Peter Neal and Anthony Stern.

I came across a print of A Free Ride at a collectors’ convention in Los Angeles. It was described, somewhat unfairly, as a pornographic Griffith Biograph of 1915! Judging by the fashions, the film was actually made around 1923. The three participants are disguised. The two girls wear wigs—one curled in Mary Pickford style—and the man wears a villain’s mustache. (During the subsequent excitement it falls off, and as he sticks it back on he shields his face with his arm against possible recognition.) The locale is Southern California; two girls are picked up on a lonely road by a man in a Model T and driven to the desert, where they prove that sex in the twenties was conducted in precisely the same way as it is today, whatever the movies would have you believe. And pornographic films were as crudely made; when a girl’s leg moves to the wrong position in a close-up, the cameraman’s hand appears in frame to push it back.

In the industry, you will hear rumors that famous stars began their careers in such films, that professional technicians made them after hours, and that blackmailers became rich from them. None of the examples I have seen betrays the skill of a professional, nor have I recognized any of the participants. (In a film shown in Ain’t Misbehaving, a man was dressed in an “Arab” headdress to resemble Rudolph Valentino in The Sheik.)

Pornographic films were known as “cooch reels” (after hoochie-coochie dancers), and they were astonishingly expensive. They sold for $100 to $200 per reel ($1,000 to $2,000 in today’s money). The police conducted raids whenever they were tipped off that a theatre owner or distributor was trafficking in them, for they were not always shown in private. One proprietor was arrested for showing obscene films to 300 patrons after hours—although, admittedly, he had the doors locked.9 Members of the Women’s Viligant Committee witnessed the destruction of such films.10

Since the police might raid a theatre showing a perfectly innocent picture on the word of some reformer, their view of cooch reels was as all-embracing as their idea of “Reds.” In 1919, a police captain marched into a theatre in Buffalo, New York, and ripped pictures of Annette Kellerman, the famous swimming star, from the walls, declaring that they were not fit to be exhibited.11

Much of the wrath directed at the movies was sparked off by the advertising displays which accompanied them. In some cases, attacks on movies were inspired by the billboards—which were detested anyway—the reformers not troubling to see the films they advertised. The titles alone were enough to cause apoplexy: Passion Fruit, His Naughty Night, The Married Virgin, Don’t Blame the Stork, Up in Betty’s Bedroom, Sex, His Pajama Girl.…12

Many of these titles were dreamed up to sell to exhibitors before the films were even made. Thus, the content was often at complete variance with the title. The Night Club (1925), a Raymond Griffith comedy about a man running away from women, contained no shot of a nightclub from start to finish. The Bedroom Window (1924) was advertised in the usual way—a face leering in at a bedroom—but it turned out to be a story of a middle-aged woman writer of detective stories without a hint of sex.

Producers lacked the daring to make their pictures actually indecent, suggested Motion Picture Magazine, so they injected enough suggestiveness into their titles to draw a crowd.13 And the advertising copy in the newspapers often suggested a film far more lurid than the one on display: “She lured men. Her red lips and warm eyes enslaved a man of the world … and taught life to an innocent boy! Hot tropic nights fanning the flames of desire. She lived for love alone.”14 This habit harmed the industry. It was not eliminated even under Hays, who was supposed to control advertising.

The real immorality of the photoplay, according to the intelligentsia, lay in its lack of reality, its sugary sentimentality, its specious philosophy, its utterly false values. Happy endings were far more likely to corrupt the mind than love scenes.15 One might have added, too, that melodrama encouraged people to regard their neighbors in terms of black and white—good or evil—a habit with potentially disastrous results politically. But as long as moral behavior was associated in the public mind exclusively with sex, such arguments were meaningless. The conflict was particularly harsh in the twenties, for Victorians and religious fundamentalists were living in the same communities with flappers and their sheiks. The industry had the impossible task of appealing to both extremes. The Victorians would attend the Biblical films, only to be shocked by the orgies. The flappers would flock to the sex films, to be maddened by the moralizing.

Before the war, a number of films featured nudity—such as Purity (1916), with Audrey Munson. But the censors clamped down on these, and picture men tried the “educational” ploy. The helping hand was more often outstretched for greed than guidance, but the films offered fascinating insights into the mores of the period.

When Theda Bara initiated the vamp cycle, playing temptresses who lured men to their deaths, people began to identify vamps they knew in real life. One woman, accused of murdering her lover, called upon Theda Bara to testify to the mental attitude of a jilted vampire.16 (Bara declined.) The vamp cycle was short-lived; before it passed, the Essanay Film Company tried to capitalize on it by making a film about a self-confessed vampire from Butte, Montana, called Mary MacLane.

Born in Winnipeg, Canada, in 1881, as a child MacLane had moved to Minnesota and later Montana. She found Butte the quintessence of ugliness and saw no romance in its mining camps or its desolate hills and gulches. Her life was an “empty, damned weariness,”17 although she found a little fulfillment from writing. She wrote every day, and described herself as a genius—“although not of the literary kind.” She completed The Story of Mary MacLane when she was nineteen, and it was published in Chicago (the home of Essanay) in 1902.

In her confessions she admitted to feelings of sexuality toward women, she longed for the devil to visit her, and she acknowledged that she was a liar and a thief. The book brought her “astounding notoriety,” fueled by reports of girls who killed themselves after reading it. Any sign of revolt among young ladies was called “MacLaneism.”18

A New York newspaper called the book “ridiculous rot,” while a Winnipeg paper, at her death, said, “the wonderful thing about this book is not that it was written, but that this child of ignorance wrote it. Coming from this young girl, it should rather inspire a feeling of awe. You can no more explain Mary MacLane than you can explain Charlotte Brontë. Shut up there in a bleak and lonely moor, she is the genius she proclaims herself.”19

She wrote three more books. The last, I, Mary MacLane, a diary of human days,20 described her life in Boston and New York: “She was careless toward men in their crude sex rapacity in ways no ‘regular’ woman would dare or care to be. No man could wring one tear from her, nor cause a quickening of her foolish heart, nor any emotion in her save mirth.”21

This sounded as good as Theda Bara, and Essanay had a brain wave. It offered the leading role not to a vamp actress, but to Mary MacLane herself. And even though she described herself as a “plain-featured, insignificant little animal,”22 she accepted. Her book revealed that above virtually anything else, she longed for fame. She even wrote the script, for she was an ardent admirer of the motion picture.23

Men Who Have Made Love to Me was directed in the summer of 1917 by Arthur Berthelet and released early in 1918. The title was “as shocking as the reputation of its star” to the Chicago Tribune.24 Yet it was not quite so startling then as it appears to our eyes, oddly enough. For the euphemism “making love” did not apply solely to coitus, as it does now, but referred to any romantic approach.* Nevertheless, Essanay intended it to be a thoroughly sensational production. The image of Mary smoking was used in the advertising; this was little more than a decade since women had been arrested for smoking in the street, and the image symbolized decadence throughout the silent era.

(Kobal Collection)

It was an episodic picture, an account of six affairs: a callow youth (Ralph Graves), who quickly bores Mary; a self-obsessed literary man (R. Paul Harvey); a depraved gentleman (Cliff Worman); a cave man (Alador Prince) she is forced to give up; a bank clerk (Clarence Derwent) who wants a baby and a cottage but loathes her smoking and drinking. The sixth is “the husband of another [Fred Tiden] who gave her a thrill one night by breaking down the bedroom door, but spoiled the ecstacy by having stale liquor on his breath.”25

Wid Gunning, reviewer and publisher, admired the playing, the treatment, and even Mary MacLane’s qualities as an actress, but he noticed one great defect—“it is absolutely cold.”26 Mary regarded each man as a specimen to be stuck on pins and examined under a microscope.27

Variety was contemptuous of the whole thing: “The Butte brand of vampire is nix.… The picture is replete with radical and ultra subtle subtitles which smack of Mary’s authorship.”28 The opening title was certainly hers: “God has made many things less plausible than me. He has made the sharks in the ocean, and people who hire children to work in their mills and mines, and poison ivy and zebras.”29

But James McQuade, in Moving Picture World, found the film utterly gripping and stressed its one indisputable asset: “It is the first time in my remembrance that I have seen on the screen author and actress concentrated in the same person, and that person acting over again love scenes in her own life with a matter of fact realism.… Mary MacLane never laid claim to being an actress and never before risked an appearance before the moving picture camera, yet in my opinion no other woman could take her place in these episodes … for the simple reason that the author appears as her very self. True Mary has no fine stage airs … and her stage walk shows … an inclination to what might be termed a waddle, yet we welcome these seeming defects because they are really part of herself.”30

The picture was banned in censor-ridden states like Ohio. And on August 1, 1919, while Mary was entertaining a friend at her home in Chicago, two detectives arrived, armed with a warrant for her arrest. She was accused of stealing dresses by Madame Alla Ripley, the designer of the gowns for the picture. “Dressed in an embroidered Japanese kimono and a feathered hat, Mary was escorted to the Women’s Detention Home, where she was forced to remain until her friends could raise bail—for although she was said to be living in ‘surroundings of comfort and luxury’ she had only 85¢ in her purse.”31

This sad episode was typical of her last years. She was addicted to gambling, her books were no longer in demand, and she seemed unable to write more. In 1929, she was found dead in “a lonely room on the fringe of Chicago’s poorest quarter.… No one was at her bedside when she died. Death was due to natural causes.”32 She was only forty-eight.

Divorce was another word for disgrace. Yet by 1908, it ended one in ten marriages. Those who went through with it were either very desperate or very brave. Women, economically dependent upon their husbands, were often ruined, alimony or no alimony. They could be driven not only from their homes, but from the very districts in which they lived. As The Social Leper (1917) pointed out, a divorced man was also a social outcast. “As a result of our picturesque laws,” said a reviewer, “[divorce] is always an exciting and dramatic theme.”33

Newspapers were the acid in the wound of divorce. Upton Sinclair recalled what happened to him: “the newspapers invented statements, they set traps and betrayed confidences—and when they got through with their victim, they had turned his hair grey.”34

In The Woman’s Side (1922), a B. P. Schulberg production written and directed by J. A. Barry, a newspaper issues a threat to publish details of a divorce and a woman warns of suicide unless it is retracted. Divorce sometimes did lead to suicide, but then such deaths were understandable: “after all, she was divorced …”

The husband of a successful actress in Cecil B. DeMille’s What’s His Name (1914) finds himself being divorced, to his intense surprise, losing his home and his furniture, which were in his wife’s name, and even his much-loved daughter (Cecilia de Mille, Cecil’s daughter). His attempt at suicide only fails when the gas man disconnects the mains. And this was in a comedy!

Based on a Eugène Brieux story about the effect of divorce on a child, The Cradle, 1923, featured Charles Meredith as a doctor who falls for one of his patients and Mary Jane Irving as the child maltreated by that patient.

Loss of affection was not legally recognized as sufficient reason for dissolving a marriage until the late twenties,35 yet newspapers complained that divorce was becoming too easy. In some places, it did become less complicated. A divorced man in Indiana told Robert and Helen Lynd: “Anyone with $10 can get a divorce in ten minutes if it isn’t contested. All you’ve got to do is show non-support or cruelty and it’s a cinch.”36 But elsewhere, if couples made the mistake of agreeing that they wanted a divorce, the judge was likely to deny them a decree.37 The entire system was described by Judge Ben Lindsey as “bungling, dishonest and putrid.”38

A generation or two earlier, divorce had been virtually unknown. “Our great-grandmothers and fathers got along very well without divorce to a great extent,” commented Variety, “contenting themselves with cheerfully throwing the china at each other. Divorce … does not flourish in the tenement districts because it is too expensive. But it thrives in elevator apartments with three or four baths and maids leashed to lap dogs.”39 (This was why most divorce scenarios dealt with the upper middle classes.)

Hollywood was depicted by the press as the divorce center of the nation. (It wasn’t—that was in the Midwest.) In California, divorce was regarded as an evil, but not a stigma, which had to be tolerated, for so many resorted to it. Yet it seldom affected the popularity of the stars. “Who can ever again see Mary Pickford or Douglas Fairbanks,” asked the Santa Ana Daily Evening Register, “without mentally recounting the destruction of family ties and ideals that lie back of their marriage?”40 But seldom was a divorce so quickly forgotten, and Pickford and Fairbanks were soon the respected leaders of the motion picture community.

Divorce was an obviously commercial subject; the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company made what was probably the first essay on the subject with Detected (1903), an episode from The Divorce (a stage play): a wife becomes suspicious of her husband, hires a detective, and the two of them ambush the husband in a private dining room, where he is living it up so energetically with his girlfriend that the wife faints in horror.

But it took more than a decade for the subject to be treated with concern and its victims with compassion. The Children Pay was a Fine Arts production of 1916 starring Lillian Gish and directed by Lloyd Ingraham, from a story by Frank Woods. “Parents, consider your children before you enter the divorce court” was its message. It caught the poisonous atmosphere surrounding a family torn by divorce. Millicent (Lillian Gish) and Jean (Violet Wilky) are sisters placed in the care of a nurse in a small town, who are shunned by all the neighbors and their children, while they await the outcome of their parents’ divorce action. Who will win custody of whom?

The mother wins Jean, the father Millicent. The father marries again; his new wife is a social butterfly. Millicent leaves home in the middle of her coming-out party and runs away with her sister. They turn for protection to their old nurse. An officer of the court discovers them and takes them back, and another custody battle ensues. The hero (Keith Armour), a young lawyer, solves the problem by marrying Millicent, who is then awarded custody of her younger sister.

The Children Pay, 1916. Loyola O’Connor, Ralph Lewis, Lillian Gish, and Violet Wilkie. The parents quarrel over which child will go with which parent.

“The entire theme is absolutely without foundation in law,” protested Variety, “for if the court had jurisdiction over the older girl in the matter of her guardianship, then she was not of age and could not marry without the consent of her guardian or parents. As a picture it will get by … but the law students will have a good laugh.”41

Julian Johnson in Photoplay considered the film “the sanest, most humanly interesting” feature of the month and praised Lillian Gish as a real, believable young woman. “There are those who say the final legal situation is impossible. I don’t know. I do know that the body of the play is a page of life, of which the screen shows far too little.”42 According to Anthony Slide, the film is an impressive work, told in the simple style perfected by Griffith at Biograph.43 Ironically, when the film was released in the 1920s for home movie use by Pathex in America, the story was altered; the divorce element was removed and the children became orphans.

“And they lived happily ever after.”

Most Hollywood romances ended with that idea, if not that title. The Hungry Heart (1917), a five-reeler from a novel by David Graham Phillips, directed by Robert Vignola, began where such films usually ended. Pauline Frederick played the wife, left to her own devices by a husband who treats her as a child, despite her college degree. She asks to assist him with his work in chemistry, but he simply laughs at her. She has a child; the couple drift apart; she has an affair with one of his handsome colleagues. The husband sues for divorce and only then realizes how much she means to him. He admits to having neglected her and agrees to her working with him. The lover offers to marry her, but she goes back to her husband.44

In an era when a woman’s adultery, on the screen, often had to be paid for by death or ruin, this was a refreshing treatment. Variety, however, could not stand it. “It is just an impossible hodge-podge, much tainted with the atmosphere of improbability.”45

The paper preferred William Fox’s Blindness of Divorce (1918,) written and directed by Frank Lloyd, which was designed to show divorce “as a work of the devil,”46 echoing Theodore Roosevelt’s declaration that easy divorce was “an evil thing for men and a still more hideous thing for women.”47

Suffering from the producer’s customary delusion that he had made the picture, Fox told the trade press, “I have aimed to show just what the 24-sheets [posters] represent—a fiend pushing apart a man and a woman whom God joined together. In my time I have seen a good many divorce cases, but I am convinced that there was not one in ten that was justified. Good people everywhere agree with me. Our clergy, our prominent thinkers, our judges are crying out against this shattering of family ties and sapping of our national life by the divorce decree—a decree that is all too often lightly granted. Therefore I have produced this picture in an effort to arouse the public against this curse to men, women and innocent children.”48

The Blindness of Divorce, 1918. Bertha Mann as the wife who takes up gambling and prostitution when her husband (Charles Clary) divorces her. The child is Nancy Caswell. (Museum of Modern Art)

In Blindness of Divorce, John Langdon (Charles Clary) prefers to spend his time with friends at the club rather than with his wife and child. A young lawyer called Merrill (Bertram Grassby) takes advantage of this neglect and forces his attentions on the unwilling wife (Bertha Mann). Returning home unexpectedly, Langdon catches his wife in Merrill’s arms, and, despite her protestations of innocence, divorce follows. Langdon wins custody of the child, and the disgraced mother is scorned by society.

Fifteen years later, Langdon is living with his daughter, Florence (Rhea Mitchell), in another city. Florence marries a district attorney (Fred Church), who is campaigning for a second term. Unknown to Langdon, his former wife runs a notorious house of gambling and prostitution in the same city. An opponent of the D.A. blackmails Florence, eventually sending her to see her mother’s establishment for herself. The mother pretends not to know her, although her heart breaks. That night, the police raid the place and Florence is rounded up with the others. The D.A. fears the worst and sues for divorce. At the trial, however, the former Mrs. Langdon makes an appearance, tells the whole story, and roundly accuses “man-made” laws. Florence and the D.A. are reunited.49

Photoplay described the film as an attempt to prove that divorce was a great evil by showing a lot of stupid people doing a lot of stupid things. “It is incomprehensible that Frank Lloyd, the one directorial genius in the Fox organization, wrote and produced [i.e., directed] this hodge-podge.”50

Whatever its aesthetic drawbacks, Blindness of Divorce created a sensation in Brooklyn, where people recognized the story. It paralleled a divorce case which had occurred in the neighborhood a few years before: “The rumor that Blindness of Divorce was practically a picturization of this case, and even explained some of the mysteries connected with the subsequent careers of the principal parties, quickly spread all over the district and combined with the regular clientele to crowd the theatre to its utmost capacity for the four days shown. A repeat is likely.”51

The divorce pictures did not develop into a cycle of sensation like, say, the white slave films; the subject was too close to that mainstay of regular releases, the love triangle. But during the twenties, about 200 features involving the subject of divorce were put into production,52 and of them all, perhaps the strangest was The Lonely Trail.

THE LONELY TRAIL The official attitude toward divorce was perhaps best crystallized in the furor which surrounded the release of this film. An incident celebrated as the Stillman case was exploited by an independent producer, who had the idea of casting the handsome corespondent, Fred K. Beauvais, in the lead. Beauvais worked as an “Indian guide” on camping trips, and he played the same role in the film. The trouble was that he had become famous—or infamous—as the Stillmans’ Indian guide in the real divorce case.

The New York State Motion Picture Commission passed the film, which, by all accounts, was innocuous. But in December 1921, in the wake of the Arbuckle scandal, the picture business became nervous about such films. Members of the Motion Picture Theatre Owners Chamber of Commerce held a meeting and stated that they would not play it. The trade press wholeheartedly condemned the producers (whom they resolutely refused to identify). Eventually, the film was offered to Lewis J. Selznick for $1,500. They chose the wrong man, since he was currently negotiating to hire Will Hays away from the post office. Selznick turned it down, and it wound up opening at the Shubert Theatre—a vaudeville house—on New York’s 44th Street. The Shuberts were not fussy about the content of pictures so long as they drew the customers.

Variety’s reviewer “Fred” went to see it and reported that it had been cut to a mere forty minutes. “As a picture it is one of the saddest bits of screen production shown anywhere in a long, long time.”53 He added that curiosity about Fred Beauvais was pulling in money, but it would not entertain. And “The girl with bobbed hair must have been picked with an eye to resemblance to Mrs. Stillman, but it ends right there. As long as the program did not give her name it must remain a secret.…”54 If left alone, he said, the picture would die before the week was out.

It was not left alone. It arrived in Washington, but the theatre owners refused to touch it, their inappropriately named spokesman, Sidney Lust, stating that as long as they could get clean plays, with respectable players, it would not be necessary to fall back upon persons who possess “absolutely no histrionic ability, but are featured solely because they have figured in a nauseous scandal.”55

The New York State Motion Picture Commission justified having approved the film, saying that Beauvais’s participation did not make the film immoral. It would be a different matter, said the chairman, if the advertising drew attention to the fact that the hero of the picture was involved in the Stillman scandal. Of course, the advertising did just that, so the commission was able to save a little face by ordering the removal of the name Stillman from all references to the film.56

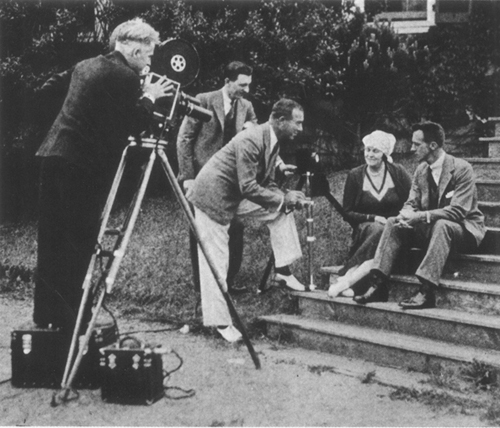

Mrs. James Stillman interviewed by A. A. Brown with her new husband, Fowler McCormick, at their honeymoon bungalow, Southampton, Long Island. A shot taken in the early days of talkies (and posed—the camera is so close to the microphone its noise would have drowned the interview!).

“If Clara Hamon and Roscoe Arbuckle are barred by popular sentiment from the screen,” declared William Brady of NAMPI, “the same holds good in the case of Fred Beauvais.… If one can become famous through murder, divorce or scandal, then encouragement only goes to spread the present wave of crime.”57 Clara Hamon† was accused of murder, Arbuckle of manslaughter; divorce was seen not as private grief, but as public crime, and bracketed with the most serious offenses it was possible to commit. The picture was banned in several states, and the incident culminated in a lawsuit, as the producers—at last revealed as the Primex Picture Corporation—sued the Shuberts in the U.S. Supreme Court for breach of contract.58 The only people to gain from such a case were the lawyers—as in divorce.

WHY CHANGE YOUR WIFE? To describe a divorce case as entertaining is perhaps unfortunate, but in the hands of William and Cecil DeMille it invariably was. Why Change Your Wife?, probably the best of the DeMille marital pictures, was shot in 1919 and released the following year. Written by William de Mille,59 it was graced with witty and elegant titles and a story packed with incident, and Cecil’s direction, although lacking the same elegance, conveyed his enthusiasm for the subject.

It would be a mistake, however, to regard it as a faithful portrayal of its time. Admittedly, DeMille directed it like a social historian, showing us details of perfume bottles, liquor decanters, razor sharpeners, shimmying dolls, and phonograph records. But he and his art director, Wilfred Buckland, created a land of the imagination, where a girl like Gloria Swanson could wear a bathing costume slashed to the thigh at the swimming pool of a big hotel, where the men clustering around her could include an aviator in leather coat and flying helmet.

Thomas Meighan plays Robert Gordon and Swanson plays Beth, his wife, “whose virtues are her only vices and who willingly gave up her husband’s liberty when she married him.” Like so many husbands, Robert is puzzled by the difference between his wife and the girl he married: “Molten lead poured on the skin is soothing compared to a wife’s constant disapproval.” Beth, whose pince-nez symbolize her frigidity, criticizes Robert ceaselessly, particularly his attempts to lay down a wine cellar.

“How can you spend money for all this,” she asks, “when you think of the starving millions in Europe?” Robert replies that they give constantly to the starving millions. “Why is it that anything I do for our personal pleasure robs people in Europe?”

He thinks a present might restore the smile to her face, but while buying a negligee in a fashionable store he meets his old friend Sally Clark (Bebe Daniels), “legally a widow and optically a pippin.” She sets out to ensnare him, and Beth does her inadvertent best to throw them together. She rejects the negligee and turns down his offer of tickets to the Follies, anxious instead to attend a musical soiree.

“Then I’ll dine at the club,” says Robert. “I’m sick to death of hearing that wire-haired foreigner torturing a fiddle.”

Sally calls, and they go to the theatre together. “When a husband has had his faults thoroughly and constantly explained to him at home, he listens more easily to an old friend tell him how wonderful he is.”

At Sally’s apartment afterward, he is invited in. “One teeny sandwich won’t take a minute.” An arm of her davenport hinges back to reveal a phonograph; the other contains a glittering decanter called Forbidden Fruit. (This was not a DeMille invention; it really existed.)60

This being a pre-Hays picture, DeMille manages to implant a genuine erotic charge into this scene, which is also very amusing. When Robert tries to light a match, Sally holds up her shoe, so he can strike it on the sole. She puts scent on her lips and his coat collar. Robert goes as far as a passionate kiss, but there he stops, to Sally’s (and the audience’s) disappointment.

Why Change Your Wife?, 1920. Bebe Daniels and Thomas Meighan, who is providing a remedy for Bebe’s headache in this risqué scene, which is not in the final film. (Museum of Modern Art)

He returns to his wife, who lies in bed, her book, How to Improve the Mind, beside her. She looks at the clock—1:45 A.M.—and demands to know where he has been. He shows her a ticket stub. Feminine intuition leads her to search his pockets for the incriminating companion to that ticket. “A friend went with me,” he says lamely. Beth is hurt and angry. He apologizes and calms her down, and she lays her head on his shoulder. It is then that she smells Sally’s perfume. This time, he confesses that the “friend” was female. Beth leaps out of bed, puts on her robe, and starts packing: “I don’t use vulgar perfume. I don’t wear indecent clothes. As you have evidently found someone who does, I won’t stand between you and your ideal.”

She is so implacable that Robert decides he should be the one to leave, and with that, at least, Beth agrees. “So when morning comes at last, merciless virtue proves stronger than love—and wrecks a home.”

Some time later, Beth overhears one gossip point out an item in the paper to another. “Oh look, Mrs. Robert Gordon has got her divorce. No wonder she lost him—she just wouldn’t play with him. Then she dressed as if she were his aunt, not his wife. Still, I’m terribly sorry for her, poor thing.”

“They pity me, do they?” sneers Beth. “Pity me because I’ve been fool enough to think a man wants his wife modest and decent. Well, I’ll show them!” Beth goes berserk; she tears off her sedate clothes and demands the latest styles—“sleeveless, backless, transparent, indecent—I’ll go the limit.” And after the divorce, she flaunts herself at a big hotel in Atlantic Beach, where she encounters Robert and his new wife. “When a woman meets her ex-husband she realizes all she has lost. When she meets his wife she realizes all he has lost.”

The story develops into a fight for possession of Robert. Injured in New York, he is taken home by Beth, and she and Sally fight for the door key like wildcats over his sickbed. Finally, Beth grabs a vial from a drawer and shouts, “Get away from that door, or I’ll spoil your beauty with this so that no man will ever look at you.” Sally cowers, and Beth wins custody of the invalid. But before she goes, Sally finds the vial and hurls the contents at Beth in a moment of vicious revenge. “It’s all right, dear,” Beth says to Robert. “It’s only my eyewash.”

Defeated in every way, Sally takes a roll of bills out of Robert’s trousers and stalks out with the remark, “There’s only one good thing about marriage and that’s alimony.”

Upstairs, the maid and butler reunite the twin beds, and a final title tells us, “And now you know what every husband knows; that a man would rather have his wife for a sweetheart than any other woman, but ladies, if you would be your husband’s sweetheart you simply must learn when to forget that you’re his wife.” Feminists then, as now, would have disapproved thoroughly of the whole dubious tale. But the moviegoing public adored it: the picture cost $130,000 and earned $1 million.61 If it was far-fetched, that was what they went to a DeMille picture for.

The final scene from Why Change Your Wife? The butler and maid reunite the twin beds and display the nightwear. This kind of touch would soon be associated exclusively with Lubitsch. (Museum of Modern Art)

Charles Higham claims in his book on DeMille that the fight at the end was based on a quarrel between two of DeMille’s mistresses, Julia Faye and Jeanie Macpherson. In this case, Jeanie threw not acid but ink.62

“DeMille caters for the sophisticated,” said Herbert Howe in Picture Play, “and, judging by the crowds patronizing this picture, we are a sophisticated nation. Why Change Your Wife? is a rouged, gemmed, silk, and sensuous reflection of the artificial life.”63 “Sophisticated and searching is the photoplay of 1920,” said Frederick James Smith. “Franker and franker does it become each month in dealing with that eternal theme—sex. The picture puritan may lift up his trembling hands in horror, but we see the photoplay as in its adolescent period.”64

Burns Mantle in Photoplay issued a prescient warning. He had no doubt the picture would be a best-seller, that women’s clubs would protest, and that the financiers would pay them no heed, but merely gloat over the night letters from exhibitors telling how they called the fire department to deal with the overflow mob. But sooner than we think, he said, we shall see a reaction against the society sex film: “Mr. DeMille and his studio associates know that the ‘moral’ they have tacked on to this picture—that every married man prefers an extravagant playmate-wife, dressed like a harlot, to a fussy little home body who has achieved horn-rimmed spectacles and a reading lamp—is not true of normal husbands anywhere in the world, however true it may be of motion picture directors. But there is enough hidden truth contained in it to make a lot of husbands and wives unhappy, and a lot of fathers and mothers uneasy. From which centers of observation the return kick is likely to start, and gather such momentum as it proceeds that when it lands the recipient will be surprised.”65

How right he was!

ARE PARENTS PEOPLE? One of the most sympathetic films about divorce was Mal St. Clair’s Are Parents People? (1925), based on a story by Alice Duer Miller, published in 1924. The story was radically different from the film, its attitude to divorce conveyed through clever dialogue. The charm of the film is that so much is conveyed visually.

The opening sequence gently observes the end of a marriage: love letters are torn up and thrown away. In a close-up of Mrs. Hazlitt (Florence Vidor), her eyes carry a hint of tears.

Next door, women’s slippers are emptied from a drawer by Mr. Hazlitt (Adolphe Menjou). His butler watches dolefully.

Mrs. Hazlitt opens a book and reads the inscription, “To my darling wife—may your love endure as long as mine.” She takes it next door, places it open on the table, and leaves without a word.

Hazlitt examines the inscription, grins ironically, and takes it back to his wife. He returns to his room and is followed by the book, which comes flying across the hall.

“I won’t need the car,” Hazlitt tells the butler. “I’ve decided to have dinner—alone.”

He spots a framed portrait of his wife which the butler has sneaked into his suitcase. Assuming his wife has placed it there, he enters her room and puts his own picture into her suitcase.

The maid sees this, and, thinking her mistress has packed it, is silently delighted. Hazlitt picks up the book, reads the inscription, and grins again. Mrs. Hazlitt, watching his every move, sees the grin and angrily slams her door. Hazlitt throws the book at the door. She opens it and slams it again. Cut to close-up of the exhaust pipe of the car. As the vehicle departs, Mrs. Hazlitt assumes her husband has left. “I’ve changed my mind,” she announces. “I’m going to have dinner alone.”

Hazlitt and his wife open their doors simultaneously and face one another, startled. Slam … slam. Hazlitt peers through his keyhole, then creeps out and turns the key in his wife’s door. Then, with a self-righteous nod of his head, he goes down to the dining room. Where he sees his wife, beginning her first course …

The film is concerned with the effect of the divorce on the Hazlitts’ daughter, Lita (Betty Bronson). “There’s nothing wrong,” her father tells her, “except your mother and I can’t agree. It’s what the lawyers call incompatibility.” Lita becomes a “grass orphan,” her only home a boarding school. When she is expelled, her parents meet and quarrel. “If you can’t cooperate about me, why bother about me at all?” demands the girl.

Lita has read in a book on divorce that parents may quarrel over trifles, but let danger threaten their children and the gulf is bridged. She runs away to the house of Dr. Dacer (Lawrence Gray). He is out, so she curls up in his reception room and inadvertently spends the night there. Dr. Dacer is furious when he discovers her in the morning. “I suppose you know you’ve compromised me … ruined my practice, my reputation?” Angrily, he drags her over to her anxious parents and rounds on the Hazlitts: “The trouble with you both is that you’re so busy being incompatible that you haven’t time to look after your own child. You ought to be ashamed.” The Hazlitts are abashed, the incident achieves the reconciliation Lita had hoped for, and the film ends with the suggestion that she will become Mrs. Dacer.

Are Parents People? appeared in the National Board of Review’s 40 Best of 1925, and several critics placed it in their Best Ten. All the reviews welcomed it, Picture Play calling it “one of the few good pictures of married life.”66 None of them criticized its attitude toward divorce, even though it portrayed it in such human terms. Perhaps, as William K. Everson said, this was because it was sparkling light comedy, “wagging an admonishing yet friendly finger at the audience for being possessed of the same human foibles that motivate the story.”67

Director Mal St. Clair managed to be warm and tender without waxing sentimental. To show the bond strengthening between the parents as they wait by the telephone for news of Lita, he has Hazlitt place his overcoat over his wife, who is half asleep on the couch. Mrs. Hazlitt touches it, then pulls it closer, smiling as she scents the familiar tobacco.

In an earlier scene, when both parents arrive at the school to take Lita on holiday, they are asked to wait in the anteroom. St. Clair builds up the tension with superbly played reaction shots, close-ups of Hazlitt’s swinging foot and, in the denouement to the scene, Hazlitt picking up his umbrella and sending a vase crashing to the floor. The headmistress smiles icily and politely inquires, “Accident?” St. Clair uses the query again to end the picture. Hazlitt knocks over another vase, and his wife asks the same question—with a smile. The shared joke is all that is needed to end the hostility between them.

Judge Ben Lindsey had aroused furious controversy over his juvenile court decisions in Denver, Colorado (see this page–this page). He aroused even more when he proposed something called “companionate marriage” in a book of that title, the sensation of 1927.68 Everyone assumed he meant trial marriage, but that was not quite what he advocated. A companionate marriage was one not primarily devoted to producing children, allowing the use of birth control and divorce by mutual consent. “People may live in the ‘companionate’ relation without enforced celibacy until they are ready to have children.”69

For this, he was beaten up in the Episcopal Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York, by churchgoers aroused by an inflammatory, anti-Lindsey speech from the pulpit.70 They also tried to have him jailed. He was eventually thrown out of his court in Denver and lampooned on the vaudeville stage. A song written for Al Jolson had a young man serenading a girl beneath her bedroom window:

Companionate Marriage, 1928, based on Judge Ben Lindsey’s notorious book, with Richard Walling and Betty Bronson. (National Film Archives)

“Oh, my darling, oh, my dear, will you try me for a year?”

The window flies open and a man leans out: “Go away, you crazy freak. I’m on trial here for a week.”71

Lindsey was treated more kindly by Hollywood. He admired the moving picture, considering it of great benefit to mankind. And it was inevitable that some company would buy the rights to his book and involve him in its production.

Companionate Marriage was a seven-reeler made in 1928, directed by Erle C. Kenton from a screenplay by Beatrice Van. It starred Betty Bronson, of Are Parents People?, and was made by a poverty row company called Gotham, although it was credited to the “C. M. Corp” (Companionate Marriage Corporation). Behind it were E. M. Asher, who had once been involved in Last Night of the Barbary Coast (see this page), agent Edward Small, and Charles R. Rogers, in association with Sam Sax of Gotham.

Sally Williams (Bronson), the product of poverty and a broken home, works as a secretary for wealthy James Moore, whose son, Donald (Richard Walling), proposes to her. Embittered and cynical, Sally wants no part of marriage and turns him down. Ruth Moore (June Nash), Donald’s sister, impulsively marries Tommy Van Cleve (Arthur Rankin) during a drunken party at a roadhouse and is herself quickly disillusioned. After the birth of a baby, Tommy deserts her and she commits suicide. Moved by Donald’s grief and anger, Sally offers to marry him. He refuses until Judge Meredith (Alec B. Francis), a family friend, draws up a legal contract whereby if, at the end of a stipulated period, either party is dissatisfied, the marriage is legally abrogated. Several years pass, and Donald and Sally find nothing but happiness and joy together.72

Judge Lindsey appeared at the opening of the picture, and he was present during its production, but, according to Photoplay, he was not crazy over the results. Said Photoplay, “Neither are we.”73

Erle C. Kenton made a film called Trial Marriage (1929), written by Sonya Levien, for Columbia. There were also several exploitation films which suggested that trial marriage was only a step from prostitution.

In Marriage by Contract (1928), a husband in a companionate marriage goes philandering on the first night after the honeymoon, and the wife finds that “no decent man of her class will marry her.”74 Patsy Ruth Miller played the wife; her gradual aging through the picture impressed the critics. According to Miss Miller, the studio bought the rights to an episode in Lindsey’s book. The judge came out to Tiffany-Stahl to discuss the project; she met him and received a copy of his book. The material was then rewritten and retitled.75 She was not aware that it ended up as an attack on his theories, but that’s what happened. Picture Play called it “claptrap,”76 but Irene Thiers gave it three stars for timeliness, for Miss Miller’s splendid characterization, and, above all, for being a direct argument against Judge Lindsey.77

Trial Marriage, 1929, directed by Erle Kenton, from a Sonya Levien scenario. Sally Eilers and Thelma Todd auction themselves for a charity dance. (Museum of Modern Art)

The very term “birth control” entered the language as a result of the work of Margaret Sanger. “I never could credit the power those simple words had of upsetting so many people,” she wrote.78 Her name is most closely associated with the subject, yet it is not generally known that she made a largely autobiographical film about her campaign and appeared in it herself.

Born Margaret Higgins, she was one of eleven children. Her father, an Irishman, was a supporter of women’s suffrage and a socialist. Yet he opposed his daughter’s crusade, as she was indeed bitterly opposed by Catholics generally. But she felt that happiness or unhappiness in childhood depended on whether one belonged to a small or a large family, not so much on the family’s wealth or poverty.79 While working as a nurse she became aware of the dilemma of working-class mothers, desperate to avoid having any more children. In many cases, their health depended upon it. “The first right of a child,” she said, “is to be wanted.”80

She met architect William Sanger and married him, and, despite her own ill health, had three children. Ordered to have no more, she returned to part-time district nursing, specializing in obstetrics. More and more of her calls came from the Lower East Side, where pregnancy was a chronic condition and abortion methods were either ineffectual or dangerous.

It was against the law in New York to give information on contraception to anyone for any reason. And yet wealthy people not only knew about it, they practiced it. “The doomed women implored me to reveal the ‘secret’ rich people had, offering to pay me extra to tell them; many really believed I was holding back information for money. They asked everybody and tried anything, but nothing did them any good. On Saturday nights I have seen groups of from fifty to one hundred with their shawls over their heads waiting outside the office of a five-dollar abortionist.”81

Sanger was helpless. But one case changed her outlook. She saved the life of a twenty-eight-year-old woman dying of a self-induced abortion. The woman was overcome by depression, knowing that another baby would finish her. All the doctor would suggest was that her husband sleep on the roof. The woman pleaded with Sanger to tell her the secret, but, obedient to the law, the nurse declined to do so. Three months later, pregnant again, the woman killed herself. “No matter what it might cost,” wrote Sanger, “I was resolved to seek out the root of the evil.”82

She started a magazine, The Woman Rebel, and Anthony Comstock barred it from the mails, classifying a mention of contraception as pornography. Facing a trial for an article she didn’t even write, Sanger slipped away to England. Comstock imprisoned her husband because of her activities, and although this case was dropped, she was arrested again and again. Charities were terrified of her, but at last, on October 16, 1916, she opened the first birth control clinic in America, in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn, New York. The vice squad promptly arrested her and her sister, Ethel (who was almost killed by forcible feeding). Sanger became concerned for the other inmates and, once she was free, set herself the task of changing the law through education.

One attempt to educate the public was the production of a motion picture, Birth Control (1917). With her associate Frederick A. Blossom, she wrote a scenario: “Although I had long since lost faith in my abilities as an actress, I played the part of the nurse.”83

Financed by an associate of Blossom’s and produced by the Message Feature Film Corporation, Birth Control was advertised with the kind of sensitivity that exhibitors appreciated: “You Don’t Have to Be a Film Buyer or Seller to Clean Up a Quick Profit on This. Everyone in the world will want to see it. It’s the Safest, Surest State Right Proposition Since Big Film Features Began, and We’ll Guarantee You It’s Law Proof and Censor Proof. Five Reels of Stirring, Varied and Picturesque Exposition of the Vital and Dramatic Phases of the Crusade That Sent its Martyr Heroine to a Prison From Which She Has Just Been Freed.”84

A statement by Sanger was included as a “certificate of genuineness”: “This is the only picture on Birth Control in which I shall appear. Part of the profits go to extending our cause.”85

Variety thought the title suggested a grim film with the atmosphere of a clinic: “The picture is anything but that. It is rather a combination of a New York travelog and the quite dramatic personal experiences of Mrs. Margaret Sanger, its heroine, who appears in almost every scene. The average observer is electrified with the intense convictions of the propagandist, taken hither and thither throughout New York’s teeming child streets, to the almost childless precincts of the informed wealthy.”86

One aspect of the film which struck the Variety reviewer was the pervasive sincerity of Sanger: “Playing a role that is herself, one looks for at least fleeting moments of artifice in the woman’s efforts to repeat for the screen the emotions she lived while conceiving her crusade and fighting for it until she fought herself into jail. But there’s no artifice in the Mrs. Sanger of the screen. She is the same placid, clear eyed, rather young and certainly attractive propagandist that swayed crowds at her meetings and defied the police both before and after her incarceration. And facts are given that if not making everyone who sees the picture a convert to her cause will certainly make everyone think twice before denouncing the movement.”87

The picture opened with a double exposure contrasting the struggling mother of the poor, lacking the money to buy the knowledge which would lessen her burden, and a middle-class woman with a small family. An interview with Sanger was illustrated by images of the weak and crippled children of exhausted, poverty-stricken mothers. There followed the story of the suicide of her patient, the persecution of Sanger by the authorities, scenes shot at her Brownsville clinic, and the trial. The film ended with shots of Sanger behind bars, with the subtitle “No matter what happens, the work must go on.”88

Birth Control was submitted to the National Board of Review, which passed it with the comment that it had been “handled with such a deft touch and intelligence” that there was no need to remove so much as a subtitle.89 It was this which encouraged the promoters to guarantee it as censor-proof. But just in case, they provided an alternative title, The New World, and issued alternative posters and advertising material.

Above: Margaret Sanger, 1916. Below: Margaret Sanger, in Birth Control, 1917. (Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College)

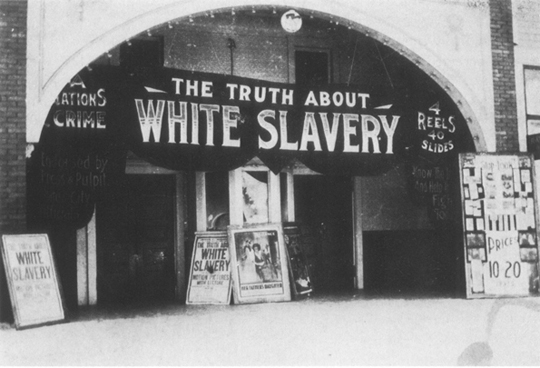

The day before the opening at the Park Theatre at Columbus Circle, New York City License Commissioner George H. Bell informed the licensee that the film was “immoral, indecent, and directly contrary to public welfare.” If it were shown, action would be taken. When the Park Theatre had exhibited The Inside of the White Slave Traffic, the police had arrested most of the employees, so the opening of Birth Control was cancelled.

Sanger staged a flamboyant coup twenty-four hours after the ban. She held a special showing of the film for newspapermen, so that they could decide whether or not it was “morally objectionable.” The distributors also applied for an injunction and Sanger sued the commissioner, to make him personally liable for damages suffered from the stigma placed upon the production and from the loss of receipts.90

Along with the press, 200 people came to the show, many of them concerned with social welfare. The entire audience voted emphatically in favor of the film, and they signed a letter to this effect.91

At the hearing, Bell held that the film should be suppressed because “it tends to ridicule the public authorities” and the state law. It also raised a class issue by “setting before the public the squalor, poverty and ignorance of the poor” compared to the luxury of the rich with their small families “[and] depicts the wealthy as contributing funds for the prosecution of those who attempt to enlighten the poor with respect to birth control and for the avowed purpose of maintaining the poor as the servant and laboring classes.”92 He added that it was going rather far to classify a birth control film as theatrical entertainment.93

Judge Nathan Bijur ruled that the commissioner’s action violated the constitutional right of free speech, but the Appellate Division of the New York State Supreme Court overturned this decision, citing the by now famous Mutual Film Corporation ruling that the business was not protected by the First Amendment.94

Sanger said that exhibitors, “fearful lest the breath of censure wither their profits,” were too timid to show the film,95 and it was only seen by those who attended her lectures. It would have been illegal to show the film in public until 1965, when the U.S. Supreme Court finally overturned state laws making the spread of birth control information a crime96—by which time the film had long since turned to dust.

WHERE ARE MY CHILDREN? “The scavengers of the screen,” said Photoplay in April 1917, “availing themselves of every fetid air which sweeps up from the sewers of thought, have successfully sailed the sea of maudlin popularity in the rotten bottoms of impossible adventure, white slavery, morbid romance and nakedness for its own sake. The present conveyance is birth control, for and against, under a variety of tissue guises and prurient titles of the She Didn’t Know It Was Loaded order. Lois Weber, with her very fine and sweet play Where Are My Children? opened the door to the filthy host of nasty-minded imitators, who announce obscenities and present bromides.”

Where Are My Children? (1916),97 however else you described it, could hardly be called “sweet.” It was an unpleasant but extraordinary film—expressing support for birth control, but abhorrence for abortion. The impact of the picture is strong enough today; what it must have been like in the age of innocence one shudders to think. Its strength derives not so much from its filmic qualities—it is no better made than many other dramas of its day—but from its subject matter.

There are two prints in existence, both incomplete, but complementing each other, the American version and the European version. Because the film was made while the war was on, but before America had entered it, there are distinct differences between the two.

The American version opens with this exposition, missing from the European:

The question of birth control is now being generally discussed. All intelligent people know that birth control is a subject of serious public interest. Newspapers, magazines and books have treated different phases of this question. Can a subject thus dealt with on the printed page be denied careful dramatization on the motion picture screen? The Universal Film Manufacturing Company believes not.

The Universal Film Manufacturing Company does believe, however, that the question of birth control should not be presented before children. In producing this picture, the intention is to place a serious drama before adult audiences, to whom no suggestion of a fact of which they are ignorant is conveyed. It believes that children should not be admitted to see this unaccompanied by adults, but if you bring them it will do them an immeasurable amount of good.98

Variety urged Universal to cut this long and muddled title.

It was not often that controversy began at the very opening titles of a film. The first sequence shows swirling clouds and massive gates opening. This special effect, which recurs frequently, is shabbily done, even for 1916, with smoke standing in for clouds and gates, columns, and celestial figures all looking as though they have been cut out of a book of Victorian lithographs.

“Behind the great portals of Eternity, the souls of little children waited to be born.” The souls are represented by the faces of infants, with cherublike wings. Among the souls are “chance children,” who descend to earth in large numbers, “unwanted souls,” who are constantly sent back, marked as morally or physically defective and bearing the sign of the serpent.

“And then, in the secret place of the Most High were those souls, fine and strong, that were sent forth only on prayer. They were marked with the approval of the Almighty.” Surmounting the smoke and the little faces with wings, a single bright cross appears. Then the story proper begins: Richard Walton (Tyrone Power), a district attorney, is a great believer in eugenics. Standing at the door of a court as a working-class couple is led out, he tells his assistant, “Those poor souls are ill-born. If the mystery of birth were understood, crime would be wiped out.”

It is a great disappointment to Walton that his wife (Helen Riaume) is childless. “Never dreaming that it was her fault, the husband concealed his disappointment.” Whenever his sister visits to show off her new baby, he is careful to conceal his delight in case his wife feels upset.

A case comes to trial that greatly interests Walton. Young Doctor Homer (C. Norman Hammond) is accused of distributing indecent literature advocating birth regulation. Walton reads passages from his book, which are shown on the screen:

“When only those children who are wanted are born, the race will conquer the evils that weigh it down.”

“Let us stop the slaughter of the unborn and save the lives of unwilling mothers.”

Dr. Homer describes to the jury the slum conditions that prove to him “the necessity of worldwide enlightenment on the subject of birth control.” Nonetheless, he is convicted.

Intercut with the trial we see Mrs. Walton guiding her best friend, Mrs. William Brandt (Marie Walcamp), to her own obliging Dr. Malfit (Juan de la Cruz), a villainous-looking foreigner in a piratical beard (although one suspects the producers were just trying to make him as unlike any other doctor as they could). Mrs. Brandt is ushered into the examining room; next we see a soul ascending to heaven, and the portals closing.

“One of the ‘unwanted’ ones returns, and a social butterfly is again ready for house parties.”

Mrs. Walton’s rakish brother, Roger (A. D. Blake), seduces the housekeeper’s beautiful daughter Lillian (René Rogers). The onset of pregnancy is conveyed by a child’s face, framed by wings, superimposed on Lillian’s shoulder. Roger seeks help from his sister, who recommends Dr. Malfit. But this time, the obliging doctor bungles the operation. Just before Lillian dies, she confesses to her grief-stricken mother, who begs forgiveness for not having told her what she needed to know.

Walton institutes proceedings against Dr. Malfit, whose defense is that he worked for the improvement of mankind by “preventing motherhood for vain, pleasure-seeking women and degenerates.” Malfit is sentenced to fifteen years hard labor. As he is dragged away, he shouts at Walton that before he sits in judgment on other people he should see to his own household. Walton examines Malfit’s account book. An invoice for fifty dollars to Mrs. Richard Walton leaps off the page. There are further bills for “services rendered”: fifty dollars … seventy-five dollars … Walton is horrified. He drives home and interrupts his wife’s tea party: “I have just learned why so many of you have no children. I should bring you to trial for manslaughter, but I shall content myself with asking you to leave my house.”

As the women depart, protesting, he advances on his wife: “Where are my children?” She collapses. “I—an officer of the law—must shield a murderess!” He staggers out, and she faints.

She visits a church. “Prayerfully now, Mrs. Walton sought the blessing she had refused, but, having perverted Nature so often, she found herself physically unable to wear the diadem of motherhood.”

The District Attorney (Tyrone Power, Sr.) ejects his wife’s friends—“I should bring you to trial for manslaughter”—when he discovers the reason for their childlessness. From Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley’s Where Are My Children?, 1916. (Museum of Modern Art)

The picture ends with a shot of the Waltons seated before the fire. “Throughout the years, she must face the silent question—‘Where are my children?’ ” Mrs. Walton sees in her imagination a little girl clamber into his lap. Then her husband grows old, and three grown-up children gather, smiling, behind his chair. The scene is beautifully lit, originally toned purple, and is surprisingly touching.

Although this film is very strong medicine, which one wants to like because of Lois Weber, one chokes on its disturbing sentimentality. The district attorney spends too much of his time kissing little children in the park—in a more modern film he would be an object of suspicion. At the same time, there is an implication that certain children are undesirable.

Nevertheless, it is handsomely shot, with a spaciousness and use of light appropriate to its upper-class milieu. The limousines are as beautiful and elegant as the women who ride in them. If the acting is on the heavy side, somewhat more theatrical than in Weber’s later films, the subject needed an extra layer of seriousness to get it by the censors, for there is no happy ending. That alone contributed to its disturbing effect.

Universal was terrified of it. The National Board of Review rejected it for mixed audiences,99 and the studio feared the local censorship boards. So Universal held it back from release and presented it in an exclusive engagement at the Globe Theatre in New York,100 risking a ban by the license commissioner. The studio hoped to secure enough endorsements to protect the picture on its journey across the country. The risk proved worth taking; the film did record business. Four shows a day were not enough, and people were turned away in large numbers.101

Where Are My Children? received excellent reviews, although the name of Mrs. William Brandt had to be changed after a protest by a well-known New Yorker of that name. Titles in the print in the Library of Congress use the name Mrs. Carlo. The National Board of Review was obliged to look at the film again, and this time sixty out of eighty-one members of representative organizations approved it for adult showing.102

Adverse criticism concerned questions of fact. As Moving Picture World pointed out, physicians like Dr. Malfit were not patronized by women like Mrs. Walton and her friends: “Safe means of checking child-birth are not a problem for the well-to-do. They are taken as a matter of course. The whole purpose of a campaign of the kind being waged by Mrs. Sanger and Emma Goldman is to place the same means within the reach of the less fortunate.”103

And why does the district attorney call his wife a murderess because she chooses to remain childless? “According to his reasoning she has committed a crime, yet in the first part of the picture he unmistakably favors the publishing of a book on birth control. Surely the principle involved is not affected by the methods adopted?”104

Released on a States’ Rights basis, the film ignited fiery indignation all over the country, sparking off court actions from which, surprisingly, it usually emerged unscathed. One place it did not survive was Pennsylvania, whose censor, Dr. Ellis P. Oberholtzer, declared: “The picture is unspeakably vile. I would have permitted it to pass the board in this state only over my dead body. It is a mess of filth, and no revision, however drastic, could ever help it any. It is not fit for decent people to see.”105

Catholics were placed in a quandary by the film, for while it was the strongest possible propaganda against abortion, it defended birth control—which was one of the reasons why the Catholic mayor of Boston, James Michael Curley, who also served as municipal censor, found himself the center of a scandal. His censorship commission virtually ignored the film; they were waiting, they said, for a “proper complaint.”106 The film had been running to enormous business in Boston for months, even though ex-mayor John F. Fitzgerald objected to it.107 The turnaway on opening night was estimated at 2,000.108

At the height of the war, the film arrived in Great Britain, where the authorities were opposed to birth control, especially since the conflict had taken such a toll of the young men and the birth rate had dropped so dramatically. So the film was recut to eliminate the sequence of the defense of Dr. Homer, and these shots were inserted into the trial of Dr. Malfit. Dr. Homer was now apparently giving evidence against him, equipped with such titles as “All incurable mental defectives, drunks, criminals and suchlike must be prevented from propagating their defects in their descendants BUT NEVER BY UNLAWFUL MEANS.”

Many other titles were altered, too. When Walton marches in to the tea party, he is made to say: “I have just learned why so many of you have no children. You avoid motherhood out of selfishness. You are a thousand times more evil than the poor girl who had to pay for her ignorance with her life.”

This meddling gravely upset the drama and by depriving the opening sequences of variety converted the first reels into a series of comings and goings of limousines.109

Despite, or perhaps because of the recutting, the reaction of the English press was excellent. Said the Pall Mall Gazette, “How the obvious difficulties of presenting such a theme for public exhibition have been overcome is a wonder. People who are used to photographic dramas will agree, one believes, that Where Are My Children? is far and away the most perfect film that has yet been exhibited. The usual weak sentimentality is absent, and in its place a fine and natural poem of the emotions.”110

Universal’s representative in England, John D. Tippett, made a deal with the National Council of Public Morals limiting exhibition of the film to adults in special halls; in return, it could be advertised with the council’s endorsement.111 Thirty thousand people paid to see it in Preston, Lancashire, and 40,000 in Bradford, Yorkshire.112 In Sydney, Australia, it played to 100,000 viewers in two weeks.113

In 1917, Lois Weber released another birth control picture, The Hand That Rocks the Cradle, perhaps because she realized the shortcomings of the first. The story was based on the imprisonment of Margaret Sanger and her sister’s hunger strike. Weber and Smalley appeared in the leads, which makes it all the more frustrating that the film is lost. Said Wid’s, “Both make their characters very impressive because they have poise, authority and repose.”114

“Many of the scenes are exceedingly painful,” said the New York Dramatic Mirror, “and a few seem to invade the privacy of domestic life with unnecessary frankness, but the production on the whole has been handled with the utmost delicacy and skill.”115

The New York license commissioner, who had restrained himself over the earlier film, pounced on this one. Apparently, persons of high standing had reported that it was “contra bonos mores” (against good morals). Universal did manage to secure a temporary injunction and the picture was able to play out its engagement at the Broadway Theater, but the ban prevented it being shown anywhere else in New York.116 The state supreme court later denied Universal a permanent injunction, the judge declaring: “If the ignorant and uninformed are to be educated by being told that laws which they do not like may be defied, and that lawbreakers deserve to be glorified as such, there would be a sorry future in store for human liberty.”117 And he referred to the precedent established in the case of the Mutual Film Corporation that moving pictures were a business, pure and simple, and were not to be regarded as part of the press.

Margaret Sanger’s name was not used in The Hand That Rocks the Cradle, but most of the reviews drew attention to the plot’s similarity to recent reports of her crusade. Variety accused the filmmakers of seizing the opportunity provided by the Sanger picture to make a quick dollar.118 But the fact that Lois Weber herself played the role so closely identified with Margaret Sanger is sufficient testimony to her admiration for the crusader.

The Hand that Rocks the Cradle, 1917. Lois Weber (center) plays a character based on Margaret Sanger, here being arrested on the platform. (Richard Koszarski)

GHOSTS At the pinnacle of the mountain of taboo subjects was what were euphemistically called “social diseases.” When the editor of Ladies’ Home Journal mentioned them in 1906, he lost 75,000 horrified readers.119 The less they were spoken of, the more they proliferated, for the majority of young people knew nothing whatever of the dangers. The result was that venereal disease became an epidemic without the public being aware of the fact. The obvious preventative, sex education, was regarded by many people, particularly the highly religious, as a crime: “The more we put such ideas into their heads, the more they will think of them.”120

In 1881, the great Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen published a play on the subject of hereditary syphilis, Ghosts. It was greeted with a torrent of abuse on the Continent and tight-lipped censorship in England, and that was before it had even been performed. (Chicago—of all cities—gave it that honor in 1882, albeit in Norwegian.)

When the Lubin Film Company stole the story and filmed it in America in 1911 as The Sins of the Father, Moving Picture World recognized its origin at once and printed what was probably the most vituperative editorial in its history: “If ever there was a case of perversion of genius it was Ibsen’s writing of The Ghosts [sic]. The ordinary human being would just as soon think of making himself comfortable in an asylum for incurables as deriving any pleasure or moral from looking at such a play. The subject is disgusting at best and Ibsen has used his marvelous dramatic powers to make it horrible and revolting. To film such an atrocity is to sin both against art and decency. A mother telling her ‘tainted son’ of the vicious life of his deceased father; the son developing ‘the taint’ by his undue indulgence in drink and his mild assault on a woman servant and the finish of a son asking the mother to help him in committing suicide—these are things that should have no representation either on the silent or the speaking stage.”121

D. W. Griffith’s Reliance-Majestic company released a version in 1915 which was described as “hardly Ibsen’s Ghosts, but a classic nonetheless.”122 Directed by George Nichols, and featuring Henry B. Walthall, this Ghosts omitted almost every reference to venereal disease. The play was so altered that denunciations of the film appeared in magazines like Current Opinion.123 Vachel Lindsay said that whenever in the play there were “quiet voices like the slow drip of hydrochloric acid, in the film there were endless writhings and rushings about, done with a deal of skill, but destructive of the last remnants of Ibsen.”124

Mary Alden and Henry B. Walthall in Ghosts, 1915. (John E. Allen)

Ghosts may lack the shattering impact of Ibsen’s play, but for anyone familiar with the subject it would have been disturbing enough. The visual emphasis is on Alving’s drinking, but Oswald, his son, suffers from “an hereditary taint” leading to blinding headaches; a title identifies the cause as “Locomotor ataxia.” He is only just prevented from marrying his half-sister. His mother has no part in his death in this version, but die he does, by suicide. The film is true to the spirit of Ibsen, even if the theme itself is a ghost.

DAMAGED GOODS Eugène Brieux, a French playwright, caused a similar sensation with his Damaged Goods (Les Avariés) of 1902. It was first presented in America at the Fulton Theater in New York, on March 14, 1913, under the auspices of the Medical Review of Reviews and its Sociological Fund. The star was Richard Bennett, who had brought the play to America and who had a hard job finding actors who did not consider a play about venereal disease to be professional suicide. Six actresses were rehearsed for the part of the prostitute; all six vanished. The role was eventually played by Bennett’s wife. “The effect of that single matinee performance was like a thunderbolt,” wrote Joan Bennett. “The ‘conspiracy of silence’ surrounding an objectionable subject had been lifted at last.”125

Bennett took the play on the road and had to fight the censors at every turn. He developed a curtain-call monologue which became famous. It concluded: “A respectable man will take his son and daughter to one of those grand music halls where they will hear things of the most loathsome description, but he won’t let them hear a word spoken seriously on the great act of love.… Pornography, as much as you please—science, never!”126