Hikers on the trail to Frary Peak

Introduction

Hikes are pilgrimages. We do them to find solace, because others have done them, to mark them off our life list, because they are recommended, to prove something, to stay fit, to connect with the spirit of nature, and sometimes just because they are there. Hikes build memories with families and friends. They feed our souls and give us time for reflection and solitude. As John Muir said, “In every walk with nature one receives far more than he seeks.”

Each hiking trail near Salt Lake City offers its own treat. Climbing Mount Timpanogos and other 11,000-foot peaks provides 360-degree views across mountain ranges, the vast Salt Lake Valley, the Great Salt Lake, the cities that lie between, and a hundred other scenic details you will never see from your couch. Hiking Albion Basin offers visual candy—such as prolific wildflowers, some found only in the Wasatch. The Lake Blanche area takes you to glacially carved lakes that sit below a sundial-shaped formation. The hike to Donut Falls is an easy jaunt to a doughnut-shaped hole in the rock and the waterfall that pours through it. Each hike offers its own reward, and with this book you can begin to discover what each has to offer you: a personal treasure hunt.

The heart of Salt Lake City beats with business, culture, education, traffic, and all the accoutrements of metropolitan living. But unlike most other metropolitan areas, lush, beautiful mountains and canyons sit on the very borders of the city and offer hiking opportunities within minutes of its hustle and bustle. These trails lead into the depths of the glorious, green mountains and the respite they offer. The outdoor lifestyle available in Utah draws many to the area. Being able to take a quick hike or bike ride before or after work, get to a ski resort in half an hour, sit atop 11,000-plus-foot peaks outside your back door—proximity is but one of the reasons the outdoor lifestyle thrives in Utah. Each of the trails described in this guide lies within an hour of Salt Lake City, most much closer.

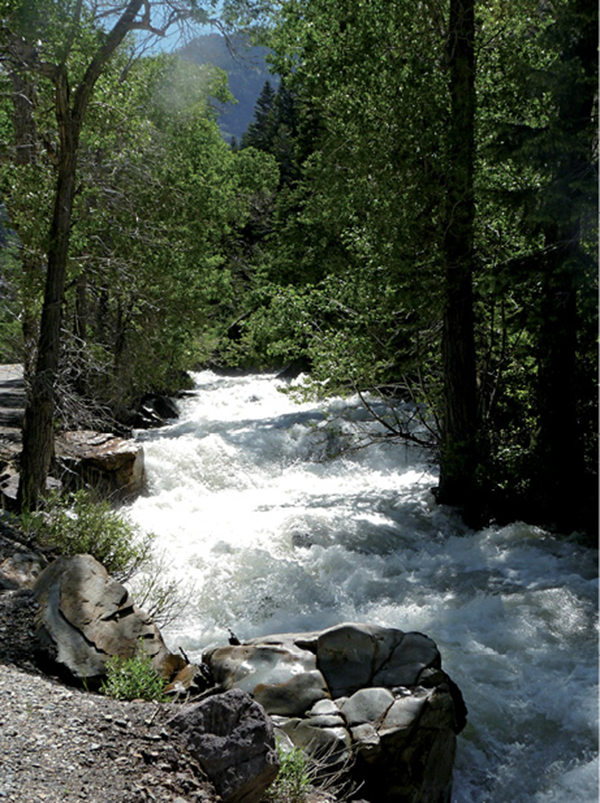

The Wasatch Mountains make up Salt Lake City’s eastern border and then continue north, bordering other northern Utah cities and up into Idaho. The range supports lush alpine forests, waterfalls, rushing streams, quiet lakes, grassy meadows dotted with wildflowers, and belt-notch-worthy peaks.

Hikers on the trail to Frary Peak

Just a glance at the Wasatch Range can leave visitors as well as locals in awe. Though I have driven past the range my entire adult life, I still can’t make it through the Salt Lake Valley without exclaiming on the majesty and beauty of the mountains.

Considered the western edge of the Rocky Mountains, the Wasatch Range stretches 246 miles from southeast Idaho to central Utah. Its slopes reach 73 miles from east to west. The range comprises three sections: The Northern Wasatch includes the Willard Peak (the highest peak in the Northern Wasatch) or Brigham City area and the Bear River Mountains running into Cache Valley and Idaho. The Southern Wasatch is home to the highest peak in the range—11,928-foot Mount Nebo—and ends approximately at the city of Nephi. The Central Wasatch Range, the primary focus of this book, runs along the Wasatch Front (the populated east side of the Wasatch Range) from Ogden Canyon to American Fork Canyon and makes its way into the Park City area known as the Wasatch Back.

Original inhabitants of the Salt Lake Valley included such Native American peoples as the Shoshone, Paiute, Goshute, and Utes. The Indian Trail via Cold Water Canyon (Hike 3) is one of the trails established by Native Americans as they forged a route past the waters of what is now called Ogden Canyon.

The Wasatch was first viewed by Europeans in 1776 when priests Francisco Atanasio Dominguez and Silvestre Velez de Escalante traversed the range. These were the first non–Native American explorers to lay eyes on much of New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, and Arizona. In the 1820s fur trappers and traders discovered the area and established trading posts and trapping systems to provide beaver pelts for the beaver-fur hats then in fashion. The trapping industry brought Peter Ogden, William Ashley, Jedediah Smith, Etienne Provost, and Jim Bridger—men for whom national forests, cities, and sections of land were named. You’ll recognize their names as you explore the area. Fur interests throughout the West dwindled in 1840 when silk replaced beaver fur as the height of fashion, and mining moved into Utah.

Hikers enjoying the trail up to Ogden overlook

In 1847 the first Mormon pioneers came to the valley. Their leader and prophet Brigham Young declared it “The Place,” and the Mormons began to establish their respite from the religious persecution that had tormented them in the East. Members of the LDS Church came from across the world to settle in the Salt Lake Valley. The hike up Mormon Pioneer Trail (Hike 32) revisits the last climb for the Mormon pioneers and their first view of the valley. The trek to Ensign Peak (Hike 14) takes you to the viewpoint from which the Mormon leaders decided upon the city’s layout.

During the Civil War, Col. Patrick Connor and his Third California Infantry entered Utah to establish Fort Douglas in Salt Lake City.

Californians prospected for minerals in the Wasatch and other areas near Salt Lake, and by the 1860s these prospectors had discovered silver, lead, and zinc deposits in the canyons and mountains southeast of Salt Lake City, particularly in Big Cottonwood, Little Cottonwood, and Parleys. The now-abandoned mines still sit within these canyons. You will pass old mines and tailings piles on many trails, though they are often unrecognizable. At Lake Solitude (hike 26) the trail takes you to the east side of the lake, where you can feel a breeze blowing through one of the old mine shafts that has been mostly filled in.

By 1870 towns like Alta and Park City had sprung up with all the usual mining town establishments. At one time Alta supported twenty-six saloons and six breweries, while Park City derived the majority of its revenues from saloon licenses and fines for prostitution. Today former brothels are used as homes, and in the Park City area, these small shanties cost a pretty penny. The trail to Cecret Lake and Albion Basin (Hike 30) and the trail option to Catherine Pass and Sunset Peak on Brighton Lakes Tour (Hike 21) explore the beautiful scenery and stark views surrounding Alta.

The Wasatch area is rich in history, natural resources, scenery, tall peaks, and the natural respite of trees, streams, mountain lakes, and wildlife. Whatever your personal reason for placing your feet upon the trails of the Wasatch Range, you are bound to find more than you seek.

Weather

The Salt Lake area has four distinct seasons with an average annual snowfall of 56.9 inches and average annual rainfall of 14.7 inches. Utah is considered desert and has low humidity. The air is dry, and temperatures are predictable. Spring (March–May) is often wet, and snow in the upper elevations does not melt some years until June or July. In April trails often tend to be muddy and wet as the snow finishes its melt. Hiking season officially begins in the lower elevations in May. By May the trees have filled in with green and the temperatures are in the 60-to-70-degree range.

July and August are the hottest months of the year, with temperatures ranging from 80 to 100 degrees. These are great months to hike the higher elevation because of the coolness to be found there. By this time the snow has melted out and the trails are dry and hospitable.

September is the ideal time for scenic fall hikes at all elevations. The temperatures drop into the 60-to-70-degree range, and the changing leaves turn the trails into bright, colorful routes. The Aspen Grove area (Hikes 38 and 39) is renowned as a scenic byway from the array of leaf color over the incredible Timpanogos area. By October the leaves have usually fallen and the alpine scenery has become barren in preparation for winter, but many hiking trails are still usable.

Trail use is not restricted, and trails are available year-round. During winter, when temperatures can range from 0 to 40 degrees, snowshoes can be used on many trails. However, the Wasatch Range holds some steep mountains, so check avalanche conditions before heading out for a winter hike.

Flora and Fauna

The flora and fauna of Utah is as diverse as the state. Change mountain ranges and you change flora and fauna. The hike to Deseret Peak is located in the Stansbury Range west of Salt Lake Valley, while the hike to Frary Peak is located on Antelope Island in the Great Salt Lake. Most of the trails near Salt Lake City are located in the Wasatch Range east of the city, but each of these areas have their own distinctive flora and fauna.

Antelope Island in the Great Salt Lake (Frary Peak, Hike 6) is home to a herd of bison introduced in 1893, antelope, and millions of migrating shorebirds such as white-faced ibis, gulls, trumpeter swans, and pelicans, to name only a few. The desertlike flora consists of grasses, sage, cacti, and juniper. The Farmington Bay Waterfowl Management Area (Hike 12) also is ideal for birding. This area boasts as many as 400 bald eagles during winter and is set up for viewing a large variety of birds.

The canyons of the Wasatch Front are filled with trees and shrubs such as box elder, willow, aspen, scrub oak, maple, and chokecherry. Higher up reside Douglas fir, limber pine, white fir, and Utah’s state tree, the blue spruce. At higher elevations (10,000 to 11,000 feet) in the Wasatch Range, spruce, bristlecone pines, and subalpine fir bravely live out their gnarled lives.

Twelve hundred species of wildflowers splash the Wasatch with bright hues all summer long, depending on elevation. Flowers begin to peak at lower elevations in April and May, and during August trails like Albion Basin to Cecret Lake and the Brighton Lakes hikes are in full and glorious bloom. According to the Cottonwood Canyons Foundation, there is one flower found only along the Wasatch. The Wasatch shooting star was known to grow only in a 1-square-mile area in Big Cottonwood Canyon until 2008, when populations were located in Little Cottonwood Canyon. This flower grows nowhere else in the world. A wildflower festival is held each summer in the Cottonwood Canyons.

Hiker in a hollowed out tree along the Adams Canyon Trail

Mountain animals tend to stay out of sight and out of the way of humans, but as we encroach upon their habitat, more human-animal encounters are inevitable. Though mountain lions are elusive and seldom seen, they live throughout the Wasatch Mountains. Black bears are the only bear species left in Utah, and though they’re relatively common in mountain forests, I have never personally run into one on these trails, though sightings have been more prevalent recently. Moose sightings are very likely, especially on the trails where boggy, wet areas and streams abound. Moose are not usually aggressive, but they can be very dangerous. Feel free to take photos, but keep your distance.

Rattlesnakes are a common snake in all five areas covered in this guide. They prefer the dry, south-facing foothill slopes and often sun themselves on rocks. Rattlesnakes don’t desire contact with humans and in most cases will slither out of your way. Trails like Adams Canyon (Hike 7) often have rattlesnake sightings.

Other animals you may see include squirrels, chipmunks, pot guts, deer, coyotes, foxes, elk, and mountain goats in the cliff areas such as White Pine Lake (Hike 27) and the cliffs in Little Cottonwood Canyon.

In all cases respect the circle of life, prepare for your safety, and don’t ever feed or touch wild animals—not even the cute, fluffy ones that beg for food.

Lake Catherine on the Brighton Lakes Tour Carla Lechtenwalter

Wilderness Restrictions/Regulations

Along many of the trails in this guide, including Red Pine Lake, Maybird Lakes, Deseret Peak, and Mount Timpanogos, you will cross into wilderness areas.

The majority of the trails near Salt Lake City lie within the majestic peaks and rugged backcountry of the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest. Encompassing nearly 2.1 million ecologically diverse acres, including seven wilderness areas, the forest is strewn with trails for exploring. These forests and wilderness areas hold the Wasatch Front watershed, which provides water for more than 75 percent of Utah’s population. Because the wilderness areas have also been designated to protect natural resources, certain use restrictions apply. For example, wilderness areas are closed to motor vehicles, commercial enterprises, roads and structures, the landing of aircraft or hang gliders, the use of motorized equipment, and motor or mechanical support. Horses are allowed, but mountain bikes are not.

Each wilderness area has its own unique regulations, but general guidelines include:

Specific guidelines for individual wilderness areas are available at www.fs.fed.us/r4/uwc/recreation/wilderness/restrictions.shtml. Watershed canyons require additional regulations for the safety of the community.

Sanitation and the Wasatch Front Watershed

Since the earliest days of settlement, the majority of Utah’s population has chosen to settle along the range’s western front. Here numerous river drainages exit the mountains, and in a desert with a giant salt-saturated lake, these freshwater sources are the hub of life. Guarding these resources is a watershed plan that encompasses the seven major canyons of the Wasatch Mountain Range (the Wasatch Canyons) and their drainages. From north to south these drainages are City Creek, Red Butte Creek, Emigration Creek, Parleys Creek, Mill Creek, Big Cottonwood Creek, and Little Cottonwood Creek. The Salt Lake City watershed comprises the waters of these creeks, the surrounding lands that support these water sources, and the groundwater recharge areas for the Salt Lake Valley.

Watershed restrictions are enforced in the following canyons: Little Cottonwood, Big Cottonwood, Parleys north and east of Mountain Dell Reservoir, Little Dell (toward East Canyon), Lambs, and City Creek. Domestic animals such as dogs and horses are not allowed in the watershed canyons. Camping is permitted in developed campgrounds only, and backcountry campsites must be 0.5 mile from any road and 200 feet from any water source.

When getting rid of human waste in these watershed canyons, follow a few simple rules:

Hiker above Red Pine Lake

Leave No Trace

Trails along the Wasatch Front are heavily used, especially during summer and fall. We, as trail users and advocates, must be especially vigilant to make sure our passage leaves no lasting mark. Here are some basic guidelines for preserving trails in the region:

Use maps to navigate (and do not rely solely on the maps included in this book).

Remain on the established route to avoid damaging trailside soils and plants. This is also a good rule of thumb for avoiding trailside irritants like poison ivy.

Pack out all your own trash, including biodegradable items like orange peels. Also consider packing out garbage left by less-considerate hikers.

Help keep water sources clean by using outhouses at trailheads or along the trail.

Don’t pick wildflowers or gather rocks, antlers, feathers, and other treasures along the trail. Removing these items will take away from the next hiker’s experience, plus it’s against the law on most federally protected land.

Be careful with fire, and build campfires only where permitted. Use an existing fire ring and keep your fire small. Remember to burn all the wood to ash and be sure the fire site is completely cold before leaving.

Use a camp stove for cooking.

Don’t approach or feed any wild creatures—the ground squirrel eyeing your snack food is best able to survive if it remains self-reliant.

Control pets at all times.

Be considerate of other visitors. Remember that you share the trail with others, and don’t make loud noises while hiking or camping.

Yield to other trail users when appropriate.

Getting Around

The Utah Transit Authority, or UTA, manages TRAX, a light rail system; the bus system; and the Front Runner, a train that connects Salt Lake City with the counties to the north. Park-and-ride lots are located across the Wasatch Front in conjunction with the TRAX, bus, and train stations for parking and carpooling. Buses make daily runs into the Cottonwood Canyons. For information on schedules and locations, go to www.rideuta.com or call (801) RIDE-UTA (743-3882).

Big Cottonwood Creek