drYad hanging shelter

When you’re young and eager and tough, and the weather isn’t too perishingly cold, you do without a mattress. I did so all through the six months of my California walk (except for the first few days when, to cushion the shock of changing from soft city life, I carried a cheap plastic air mattress that I didn’t expect to last long, and which didn’t). I soon got used to sleeping with my mummy bag directly on all kinds of hard ground, but I often padded the bag inside with a sweater or other clothes. On that trip temperatures rarely fell more than a degree or two below freezing, though on one occasion I slept on stones at 25°F. (That night I had a floored tent and a few sheets of newspaper, which make a very useful emergency insulator.)

But failing to use some kind of insulation under your sleeping bag (unless it’s a foam bag) is, in all but consistently hot weather, grossly inefficient: your weight so compresses the down or synthetic directly beneath you that its air-holding and warmth-conserving property is cut almost to zero. And even when cold is no problem you’re liable to find that if you’ve grown used to an ordinary bed, the change to unpadded bag-on-the-ground ruins your sleep for at least a few nights. This reduces both your efficiency and enjoyment, and the saving in weight just isn’t worth it—unless you can be sure of finding soft, dry sand for a bed. Then all you need is a couple of wriggles to dig shallow depressions for shoulders and rump, and you’ve got yourself a comfortable sleep.

The traditional woodsman and Boy Scout routine was to build a mattress from natural materials: soft and pliable bough tips, or moss or thick grass. On the California walk I did for a while use branches from desert creosote bushes. But in today’s heavily traveled backcountry camping areas the cutting of plant life is not merely illegal but downright immoral—an atrocity committed only by the sort of feebleminded citizen who scatters empty beer cans along our roadsides. Besides, the method is inefficient. Even when you can find suitable materials, you waste time in preparing a bed. And the bed is rarely as warm or comfortable as any of the modern lightweight pads or mattresses.

For perhaps 20 years the standard equipment under almost all conditions was an air mattress. These traditional devices have now almost, but not quite, disappeared from mountain shops. I still use one occasionally, though, when I judge the night won’t be cold enough to make sub-sleeping-bag insulation a major problem but weight, or even just comfort, might be; when I think I might need it for a river crossing; when bulk poses a load problem; or if I want to spend a lot of time sitting and reading or writing, and like hell fancy the idea of an easy chair (though for a more comfortable chair, see this page).

If you decide you want an air mattress for some reason, avoid at all costs—unless you want it only for a night or two—one of the cheap, thin, plastic jobs. They puncture and tear almost without provocation, and often don’t get the chance to do either before a seam pulls open. Coated nylon does much better.

An air mattress amplifies the efficiency of your sleeping bag by keeping a cushion of air between it and the ground. The air can circulate within the tubes, though, and therefore passes heat by convection from warm body to cold ground—and especially to snow. But an air mattress also neutralizes the sharpest stones, supports your body luxuriously at all the right places, converts into an easy chair, and will if necessary float you and your pack across a river (this page). It also gets punctures.

An offshoot is the down-filled air mat (DAM). This unlikely device by Stephenson-Warmlite is an attempt to combine the sink-in comfort of an air mattress with the much greater insulation of small, trapped air pockets. A box-baffled, urethane-coated nylon shell, fitted with an air valve, is filled with goose down, as in a sleeping bag or jacket. The great gain compared with a self-inflating pad (see below) is reduced bulk for packing. But in case of a puncture you lose the backup of a conventional foam pad. And because your breath would soon soak the down you must inflate the DAM with a short plastic tube attached to a special sleeping-bag stuff sack that acts as pump. In addition, because DAMs are made in special conformations to fit specific Stephenson sleeping bags, they’re damned expensive: $140. All are 3 inches thick. Weights: from 1 lb. 4 oz. to 1 lb. 9 oz.

Foam pads succeeded air mattresses as king of the backcountry underbed, and they ruled for perhaps a decade.*10

Still air trapped in small enough chambers—less than (¼-inch diameter—forms an excellent barrier to heat transfer, and foam pads hold the air in just such small chambers and therefore insulate far better than air mattresses. They also tend to be lighter and cheaper—and puncture-immune. But they’re bulkier, and most of them are far less comfortable—except on snow or sand or a deep pile of leaves or other soft underlayer. In addition, they make inferior chairs and will help you precious little on river crossings. On balance, though, they proved better than air mattresses and superseded them for general backpacking, especially in cold places. For years no one in his right mind has carried an air mattress for snow work.

For 20 years now, you’ve been able, under almost all conditions, to have the best of both worlds.

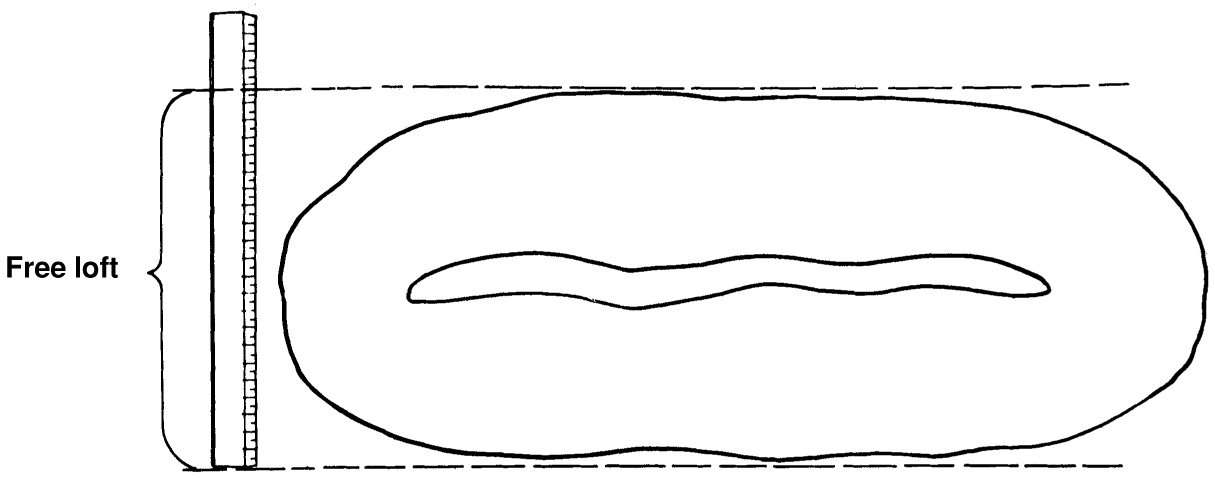

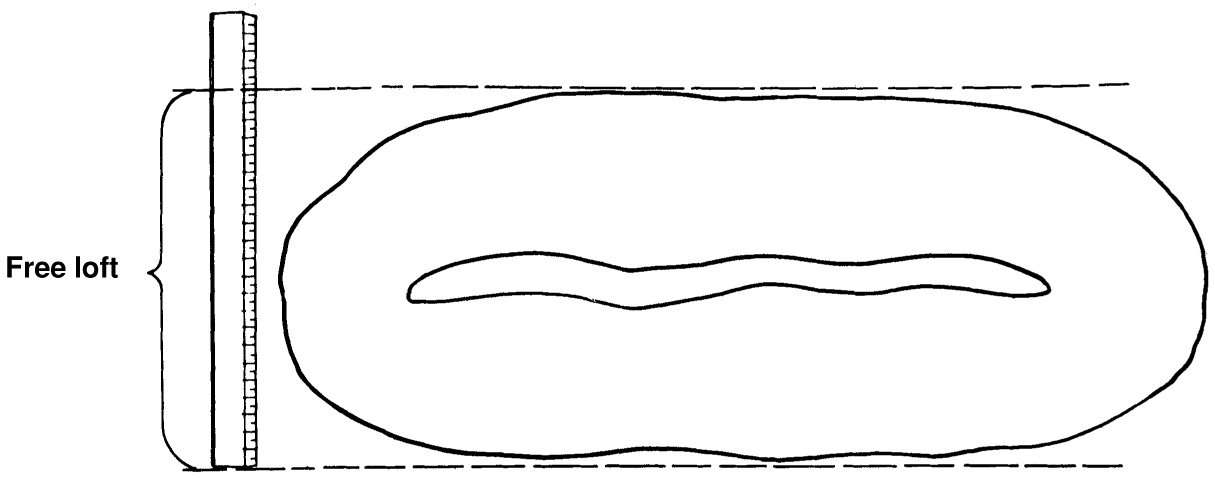

It’s very rare for a new piece of backpacking equipment to sweep aside, almost overnight, all the oldies. But Cascade Designs’s Therm-a-Rest mattress virtually pulled it off. A Therm-a-Rest—or one of the later competitors—is at least as comfortable as an air mattress and insulates better than most pads. The idea is simple: an open-cell foam pad that is covered with a tough, waterproof, airtight nylon twill cover bonded to the foam. A valve at one corner enables you to control the air pressure in the foam’s spaces. To deflate for packing you roll the mattress on a flat surface or your thighs, then close the valve. The mattress remains rolled and is reasonably compact. To inflate you simply open the valve: the mattress will slowly unroll, and within a few minutes—the time needed to erect a tent, say—it’s ready for use. You can simply close the valve or you can—as I almost always do—blow more air in and then close the valve. Inflated that way, the mattress is more comfortable as well as a more efficient insulator. Rather to my surprise, I find that the harder it’s inflated, the more comfortable it is. But you can experiment and then minister to your personal druthers.

Punctures occur only rarely (full instructions for repair come with each mattress, and there’s now a repair kit—Hot Bond, $5—said to be good); even a punctured Therm-a-Rest is still a serviceable open-cell foam pad (for open- and closed-cell pads, see this page). Faulty valves can be replaced fairly simply (spares, $5). It’s my experience, widely shared, that if you treat your Therm-a-Rest with anything less than brutality it will give good service. It is very well made and the makers stand sturdily behind their product—even, sometimes, beyond the two-year warranty.

I suspect that a Therm-a-Rest might even fill the special role of air mattress as flotation device for you or your pack (this page)—though if you ever got water in that open-cell foam…

Naturally, all this joy does not come cheap—in ounces or dollars.

CHIP: But, like a good sleeping bag, the cost is reasonable if you reckon the years of good service. I bought my first Therm-a-Rest mattress, an orange ¾-length, in 1980. It cost me $39—a vicious bite at the time. But divide that by the 21 years since and you get $1.86 per year for a decent night’s sleep. That’s quite a bit less than if I bought a new, cheap air mattress every year. My original Therm-a-Rest does have drawbacks. The nylon shell is slippery. I sprayed and resprayed it with Slip Fix, making it look as if I’d blown my nose on it 10,000 times, and even the anti-slip coating has grown polished with use. In 1987, I punctured it once, mysteriously, dead center, and applied a neat patch from the kit. So, in hard and constant use, that’s 0.05 punctures per year. About 1989, the original brass valve crapped out so I replaced it with a mitten-operable plastic one. All my pad lacks is a name.

The new Therm-a-Rest pads are topped with nonslip polyester and undergirded with a coated nylon oxford. The valve is long-lasting plastic. The repair kit is likewise improved, with a heat-bonded patch (you use a pan of boiling water) rather than the old glue-on type.*11

There are four Therm-a-Rest series: Luxury, Performance, Classic, and Discovery. The first three come in full- or ¾-length. But some full-length pads, at 77 inches, are fuller than others, at 72. The ¾-length pads are 56 inches or 47. Any pad with “Camp” in the title is both longer and wider (25 inches versus 20). Except for the CampLite I’m not listing the Camp-width pads, because they’re on the heavy side for backpacking.

The Luxury Edition pads (full: 2 lbs. 5 oz., $110; ¾-length: 1 lb. 9 oz., $82) have round, widthwise channels in the foam, for lightness and also cushy butt-hugging thickness (2 inches). Topped with Softknit fabric, these verge on the indecent—if you have hidebound notions of roughing it, that is. But if you’re heavy and bony, tending to bottom-out on regular pads, this one’s the ticket. Just don’t crow too loud, or your significant other will snag it (mine did).

The Performance Series is filled with LiteFoam, which is cut vertically with overlapping slots and then stretched across the width. The 1.6-inch-thick CampLite is both longer (77 inches) and wider (25 inches) than the standard 72-by-20-inch pad, while only weighing 4 oz. more (full: 2 lbs. 12 oz., $80; ¾-length: 1 lb. 15 oz., $70). After Linda selected my new Luxury pad for her personal suite, I adopted the 1-inch-thick UltraLite (full: 1 lb. 8 oz., $70; ¾-length: 1 lb., $54). Blown up taut, it gives me just enough flotation for comfort and packs beautifully—the ¾-length size rolls to a 4-inch diameter and is 10.5 inches long. In summer, I stick with ¾-length pads. In winter, I formerly used a ¾ pad and wadded up extra clothes under my feet. But, with the advent of ultralight models, I’ve switched to a full-length pad for snow camping, with a reflective layer beneath (this page).

The Therma-a-Rest Classic Series is the old reliable Standard, 1.5 inches thick with improved foam and a nonslip woodsy green top (full: 2 lbs. 8 oz., $65; ¾-length, 1 lb. 9 oz., $50). The Discovery Series Explorer weighs the same, has the same warranty, and costs less (full: $50; ¾-length, $40). A combination cover with straps and pillow sleeve called the Therm-a-Wrap has just risen from the waves.

I visited Cascade Designs in Seattle and watched the birth of a Therm-a-Rest UltraLite pad—or a whole herd of them, actually—laminated, pressed, and bonded. Kitty Graham, my guide, had two dogs curled up by her desk—it seemed like a pleasant place to work.

Other makers are trying hard to get into the bedroom-on-your-back. Artiach, a Spanish company, makes a pad covered in a glossy, nonslip polyester called the Skin Mat. The covering does feel disconcertingly like skin, though not human skin. It’s dark gray and crinkled, like those 1960s B-movie Martians that scared my smaller self. The Skin Mat’s not scary, though. Instead, it rolls up compactly and has a light protective cover. As pads go, it’s not bad, though it doesn’t fully inflate without some puffing and I did pinhole it first time out. But I repaired it by rubbing cement over the hole—didn’t need a patch. I have a regular 63-inch midlength pad (1.5 inches thick, 1 lb. 14 oz., $64). I’ve been using this as my winter pad, for several reasons. The length works out nicely, with a fat makeshift pillow of fleece. It’s rather thin-skinned, but snow covers the world’s horny hide. And there’s nonslip “skin” on both sides of the pad, so it doesn’t skate around on the Reflectix sheet I use underneath (which coated nylon does most annoyingly). Artiach also has a more conventional Confort Mat Series and a Compact Mat Series, all in long, ¾-length, and the distinctive 63-inch midlength size. Weights are from 1 lb. 5 oz. to 5 lbs. 5 oz. and prices range from $49 to $98.

Stearns takes a different tack with the Ergo Mat Series. The open-cell foam isn’t bonded to the casing. This means you can puff it up a bit extra and get the full floating-air effect, with enough foam to keep you from bottoming, shouldering, hipping, or heeling out. (My friend Paco, aka Jack’s Plastic Welding, has made river runner’s pads this way for years, and they’re the catfish’s pajamas, though a bit hefty for backpacking.) Anyhow, the full-length Ergo Mat’s tapered, mummy shape has three segments so you can vary the softness and thickness from back to bum to legs. There’s also an inflatable, foamless pillow. Once you get it right, it’s comfortable for the weight and bulk—combining the virtues of a self-inflater and a well-designed air mattress. The drawbacks are three plastic flap valves, but they’re located so that rolling up the pad exhausts the air and then more or less automatically closes each valve in turn. Two snap-on straps are included. The pad I tried a few years ago, the Ergo Mat Long (77 by 22 by 1.5 inches, 1 lb. 10 oz., $54) had a somewhat slithery top cover, though the current catalog lists all variations as having nonslip fabric.

Other semi-aerated pad purveyors are Backcountry Designs, Coleman, Mountain Equipment Co-op, Paramount Outfitters, Slumberjack, Sunny Rec, and Wenzel.

Before the trip, open the valve, let the pad uncrimp, and then blow it up tight and leave it overnight, to let the foam expand. (If it’s limp the next morning, take it back to the store.) To keep your pad in good shape, store it with the valve open so the foam doesn’t lose its bounce. To pack it, roll it once to get the air out, then unroll, fold double along the length, and re-roll for storage inside your pack. Or roll it up once and cover it with some sort of bag or sheath for transport outside your pack. Lashing a pad unprotected to the top or rear of your pack exposes it to sharp stubs, thorns, rock crystals, etc. Keep mosquito repellents with DEET (diethyl-whatever) way away: it melts the urethane used to coat (i.e., hold air inside) synthetic fabrics. That is, power lounging after applying bug dope can ruin your day (and night). All the generic finger wags about UV apply. The trick is not to sacrifice your enjoyment to preservation: your pad need not outlive you.

Pads that (intentionally) don’t inflate

COLIN: Naturally, not everyone will want a Therm-a-Rest. Some people are, for good, bad, or indifferent reasons, wedded to foam pads. These can be lighter and less bulky, not to mention cheaper. And cost may be a crucial factor, especially if you backpack only rarely.

Closed-cell foam pads have impermeable surfaces and trap tiny air pockets almost permanently. They therefore insulate extremely well and are mostly waterproof. But they compress very little and, although thin (⅜ through ½ inch), are bulky to pack. When a pad is new, indentations quickly disappear; but with age it becomes, like people, less resilient. And severe cold makes some foam stiff and brittle. The thinness and incompressibility mean that closed-cell pads do not cushion you well; but comfort can be increased—at considerable cost in weight and bulk—by laminating sheets together. Pads come in various hip- or full-length sizes, or in sheets you can cut to suit.

Most early closed-cell pads were Ensolite. It has been improved and joined by others, and we now have a spectrum of pads in a wide range of sizes, weights, costs, and resistance to cold and abrasion. For a few current spectrum points, see below. Others exist. More will assuredly follow—and wax and wane with the passing moons.

CHIP: Among the determined users of closed-cell pads are those who bivouac on puncture-rich ground: in talus caves, on desert pavement, or under snaggly scrub. (The more sybaritic members of the tribe also slip a ¾-length self-inflater inside the bivouac sack.) Generic single-layer slabs can be scooped up in discount stores for $5 to $10. Those in backpacking shops range from $10 to $20. Black Ensolite, which resists cracking in cold weather, comes in ½- and ¾-inch thicknesses and 6-foot lengths, for $30 to $45.

Wildly popular are two closed-cell pads from Cascade Designs. The Ridge Rest goes through a special press that leaves crosswise corrugations in the foam. This renders the pad slightly more compressible under body weight, for comfort. There’s probably no one in the developed world who hasn’t seen one of these, if only by the side of a highway, blown off the roof rack of some hapless soul. They’re superb, as 3-season pads, and I use one regularly. But winter’s a different story. If you don’t get every bit of snow off them before going to sleep, or if there’s frost falling from the inside of the tent, your body heat melts it and the neat little channels channelize it to the lowest point: right under your sleeping bag. The Ridge Rest Deluxe (two-tone purple and metallic green) is 72 by 20 by ¾ inches and 1 lb. 2 oz. for $29. The Ridge Rest Regular is ⅝ inch thick, 14 oz., and $20, with a ¾-length version a mere 9 oz. and $15.

The Cascade Designs Z-Rest goes into a different press, and comes out in a pattern you could call egg-crate (for hummingbird eggs). Rather than rolling, it folds up accordion-fashion, with the little eggules nesting into one another. This makes for compact, if rectilinear, packing. Even though it appears lighter, it weighs a bit more than the regular Ridge Rest: the 72-inch Z-Rest weighs 1 lb. and runs $30, while the ¾ size is 11 oz. and $24. Lighter people rave about how comfortable the Z-pads are, while bony heavyweights (me) tend to flatten the eggules at key points, and thus prefer the Ridge Rest. When I visited Cascade Designs, they were working on a new, ultraresilient, top-secret formula for Z-Rest foam. The enemies of these pads are solvents and heat: don’t leave them under the rear window of a parked hatchback. A tangential use is to stiffen up the mattresses in Third World hotels or student rentals.

COLIN: Open-cell foam pads compress easily and are therefore more comfortable than Ensolite and its cousins. But to achieve the same insulation they must be about three times as thick (normal range, 1½ to 2½ inches). So they’re bulkier, heavier, and more expensive. The bulkiness is more apparent than real: stuffed hard into a packbag, they compress halfway well. Open foam is often corrugated, in “egg-crate” or zigzag form, to increase comfort with minimum additional weight.

Because the open-cell structure soaks up water, the pads mostly come with covers—coated waterproof nylon underneath, with a nonslip blend on top to reduce slipperiness and permit perspiration to dissipate. A pleated pocket at the head of the cover may offer holding space for whatever pillow you choose to inject (this page). Before the advent of the Therm-a-Rest, I used a Sierra Designs version of such a pad for years under most conditions except snow and found it as warm and trouble-free as Ensolite and almost as comfortable as an air mattress. A Georgia reader suggests a cheap, do-it-yourself covered pad: open-cell foam, 25½ inches wide, 1 or 1½ inches thick, with two industrial-strength plastic garbage bags slipped over opposite ends, joined amidships with duct tape, and punctured at one end (for air escape and easier packing) with slits placed at ½-inch intervals.

Meanwhile, evolution pads on.

CHIP: Mountain Hardwear has a new series of tapered pads, 1.6 to 2.4 inches thick, in 50-, 60-, 72-, and 77-inch lengths. Weights range from 1 lb. 12 oz. to 4 lbs. 6 oz., and prices from $42 to $89. Not inflatable—by any normal means at least—they have wiggly open-cell foam laminated to a sheet of closed-cell foam and nonslip covers with nice pillow sleeves. Everything I’ve seen from the Mountain Hardwear folks has been top-notch, and early reviews on these pads are good, except for the rolled-up size, which is bulkier than that of a self-inflater.

Reflectix insulation is grand stuff: thin aluminum foil on both sides, bonded to a 5/16-inch sheet of bubble wrap. I got a roll to insulate my workshop, and liked the looks of it. So I cut off a 74-inch piece to take snow camping. The insulated part is 22 inches wide, with a 1-inch stapling strip on either edge. My pad liner weighs 10.5 oz. (or 1.7 oz. per foot). Camping in February, I noticed that I hadn’t melted out my usual body trough in the snow under the tent floor. That’s a first, since I radiate heat like a fresh-caught meteorite. The bubble wrap gives it minor effectiveness as padding: on snow, hardpersons can punch out hip and shoulder recesses and use Reflectix alone. It’s slickery under sleeping bags, though, and knees and elbows tend to pop a few bubbles each time you roll, so the life span is limited. But mine has survived its third winter. Reflectix and similar products can be found in eco-solar-type catalogs, or at the local home center. A 25-foot roll (four full-length pads) costs $25.

Last and most curious is a hybrid sleeping pad/chaise, the subinflationary PowerLounger, at 54 by 17.5 by ½ inches. The core is foam, while the nonslip cover has wing straps that elevate the upper third into a nearinstantaneous backrest. The PowerLounger (1 lb. 14 oz., $51) is built by Crazy Creek Products, who also originated the backpacker’s chair.

as Variety might put it, now do boffo biz with hike-happy hordes. Since Crazy Creek ranks first in time, let’s take them as somewhat representative. There are two main types. The fabric and foam chair (no inflation) buckets around your buttocks in a way that’s at first disconcerting. But once you get the way of it, you can be comfortable indeed. The Crazy Creek original weighs 22 oz. and costs $37. Variants exist for canoes, stadiums, and other presently unimaginable spots. I saw a young couple using one in a futile attempt to ensconce their unhappy child on the back of an unhappier llama. The second sort is a fabric shell, with wands or stays, that warps a self-inflating pad into chairlike form. Crazy Creek makes the ThermaLounger in various widths and lengths from Mini to Camp, and weights from 15 oz. to 1 lb. 14 oz. Not only must the width be compatible with your pad, but length figures in too.

In a moment of weakness I got a Therm-a-Rest Lite 20 Easy Chair, in a color called Grape. (Hail to thee, blithe nylon—grape thou never wert!) Despite every intention of testing it rigorously, I haven’t unwrapped it yet. It slumbers, vivid, beneath its plastic shroud. My fear is, I guess, that I’ll head off on a walking trip only to spend more time lounging than walking. In any event, Cascade Designs has Easy Chairs to fit all of their pads (except the Z-Rest). As do most other pad-forming entities.*12

I do rely, especially after lugging a heavy winter pack and being storm-cooped in a tent, on a self-supporting device. But it’s not a chair. It’s a construct of webbing, buckles, and modest pads called, in fact, the Nada-Chair (9.5 oz., $49). The back support, 6 by 20 inches, is crossed by 2-inch webbing loops that slip down over your knees and then buckle together, midthigh. It works the same way as a Crazy Creek Chair, but discreetly. You can’t plunk down in it. You have to sit in a conscious way. But you can get out of it more easily. I find it pleasanter, on the whole, than a butt-enveloping slab of nylon. And it’s certainly a lot lighter. Since you wear it rather than sit in it, it also works as a back brace for pounding a keyboard, as I’m doing now.

I’m not sure whether doubling up my sleeping pad in winter accords—philosophically at least—with my stringency in the matter of chairs. An eminent book reviewer once observed: “There is something of the anchorite in Rawlins.”

I leave it up to you.

COLIN: A reader once wrote from Liberia that he often used his army hammock from Vietnam for backpacking, “with no regrets…only a few reservations.” Now, most people shy away from the idea of sleeping in a hammock, especially after a long day with a heavy load. I certainly do. But you may not. And I guess a light hammock can be useful as a bed if you want to keep cool (air all around you) in a place as hot as Liberia; if the ground, every place, is soaking wet; if you’re petrified beyond sleep by the thought of rattlesnakes or scorpions or other things that might go chomp in the night; if the local ground insects are a ravenously hungry host; or if you’re an old-style sailor, landlubbering but pining. Other suggested uses: for slinging food and gear from trees, high above the ground, as protection against flood, bears, and other invaders; for rest, not sleep, at a base camp; and, with poles, as an emergency stretcher.

My Liberian correspondent’s hammock seemed to be of some solid fabric: he didn’t like or trust “the net-type sold for packers.” But sold they are—or at least offered: knotless synthetic-mesh jobs described as rolling into “a pocket sized ball” and damn nearly doing so (main body 32 by 72 inches, 12 oz., $15). Also sometimes seen: a Mayan Indian design, “made of miles of 100% pure cotton lace, hand woven and hand tied…so big and strong it’ll sleep three adults…. Easy to care for, will last and last” (10 by 11 feet, 3¼ lbs., $60). A selection of Mayan handwoven net hammocks and Brazilian cloth ones can be bought from a Boulder, Colorado, outfit called Hangouts.

CHIP: My uncle Sid, who spent an adventurous decade in South America, returned with a tribal hammock-for-two in which he’d slept regularly. According to him, the Indians, who practically live in their hammocks, bed down more or less crosswise. This greatly lessens the fundamental droop.

Two nylon models that I have actually seen and briefly occupied are the Blue Ridge Camping Hammock (4 lbs. 4 oz., $172, from Lawson Hammocks), which has two aluminum hoops to support the netting and fly sheet; and the Jungle Hammock (4 lbs. 3 oz., $169, from Clark Outdoor Products), which eschews hoops and uses separate rigging points for hammock and fly (four altogether). The Treeboat Hammock (3 lbs. 12 oz., $115), which I’ve heard about but haven’t seen, is made by New Tribe of Grants Pass, Oregon. It has four-point web rigging with raindrip-stopping rings at each corner and slip-in fiberglass battens. For cool nights, a Quallofil underside is 2 lbs. and $55, while mosquito net runs 15 oz. and $40. The Treeboat two-hoop rainfly is 12 oz. and $70, while a three-hoop tent top with zip doors is 2 lbs. 7 oz. and $100. The New Tribe catalog has a vast assortment of tree-scaling gear, including hardware, cordage, shot pouches, special arrows (for reaching extra-high branches), and books like The Tree Climber’s Companion by Jeff Jepson ($10.50) and Recreational Tree Climbing by Dick Flowers ($7.50).

Unfortunately, any bed that forms a catenary curve plays absolute hell with my back: I can’t sleep, and the next morning can barely walk. Which rules out the army/navy/marine-surplus models (and private variations) for me.

But hanging one’s bed from a tree does have a certain appeal. One April in southeast Alaska, I was looking for deer and brown bears with a biologically inclined friend. After boating to a snowcapped island, we walked for hours through a dank forest, clambering over roots and down trunks, all humped and festooned with soggy moss. The fact that I could scarcely walk, let alone run, on such stuff, along with the idea of horse-size bears emerging ravenous from their dens, made me mildly uneasy. There were occasional openings, called muskegs, nicely cushioned by organic muck, but our feet pressed down into groundwater at every step (imagine a floating sponge). There wasn’t a nice dry flat patch of mineral dirt for miles. The only half-decent place I could see to sleep was on bedrock points, lashed by waves, or on pebbly beaches above the tidemark. As I was pondering this aloud, my friend pointed out the bear trail that paralleled the beach, so well traveled that each pawprint was deeply indented. “Lots of edible goodies wash up, so the bears patrol,” he said. “Or at least the hungry ones do.”

“So, uhhh, Nels—where do you sleep out here?”

“On my skiff, anchored out in that little cove.”

For the skiffless, whether afoot or a-kayak, a ripe possibility is the Dryad DT 100 Suspended Shelter by the Canadian firm Terrelogic (7 lbs. 5 oz., $350). The photos in their brochure intrigued me, showing the Dryad hung between mangroves on an islet with no sand whatsoever, just interlaced roots. Another showed it 20 feet up (well out of claw range), hung from a single point. On a hike last spring down a narrow canyon, with the trail shelved on a timbered slope above a thundering creek, I’d thought: What a gorgeous place to camp, if you could just roost in a fir.

So I tested a Dryad (they render it drYad, which could conceivably be read as Dr. Yad. I do grow weary of strangely capitalized words). Picture a double-wall tent with a floor you can trust. The suspension is quite good—the floor, with tapered ends, is framed by fat aluminum tubing that plinks together with shock cord.

drYad hanging shelter

When you get it plugged together, a lengthwise nonstretch Dacron strap reefs it tight. Suspended from eight lengths of nylon cord connected to thick webbing loops, the floor is level, tight, and distinctly more habitable than a droopy-ass hammock. In cool weather you’d want an insulating pad, or better, Reflectix insulation (this page) trimmed to fit the floor.

My first night out was chill: 20°F. Even with the fly partly unzipped on both sides, there was condensation and frost. By morning the floor and the bottom of my sleeping bag were wet. Forests, the natural habitat of dryads, are both more humid and more still than open sites, so venting is crucial.*13 Double sliders on the door zips would help, and so would an overlap vent at the head. The rainfly could be made of a breathable laminate, tacking on further cost. Of course, in smiling weather, you can roll the rainfly up on one side or both, and lounge like a peeled banana on your airy, screened-in cot.

The built-in backrest was a surprise, adding great comfort for little weight. From a compact tuck it slips down two of the suspending cords. I also discovered that you can pluck bass-viol notes on the cords (the tone is quite good, for a tent). On my second—and considerably warmer—night out I rolled up the rainfly, plucked the cords, and sang “Bye-bye Blackbird” while rocking gently.

The Dryad is a camper’s rig. Hard-core climbers are best served by a single-point porta-ledge and matching fly (Terrelogic makes one, the DT 200). But most climbers’ ledges, while technologically awesome, are two or three times the weight of a tent and when folded are over 40 inches long. The Dryad, on the other hand, is sort of packable—once you get the hang of it. The frame disarticulates while remaining in its sheath, and the whole assemblage stuffs loosely into a sack that’s 26 by 9 inches. Fearing punctures, I used some emery cloth on the edgier parts of the frame, and am looking at further unauthorized (or maybe “author-ized” is the perfect word here) changes, so that I can pack the frame separately.

I’d rate the whole concept as promising. In steep, forested country, it could be a godsend. For casual use, I’d rig the thing close to the ground.

To rig from one point, on high, you need slings and an extra-cost spreader bar. Most trekking poles are too short—a 5-foot span is needed. (You also need a tether or two, to keep it from swinging or spinning—unless you enjoy that.) I had to build a 7075-aluminum eave-stretcher pole, having snapped the original fiberglass one during a complex maneuver I’d rather not describe.*14

If you need (or want) to suspend your bed more than a few feet off the deck, consult a book on big-wall climbing for relevant details and precautions. Get real carabiners (not those little keyholders) or steel rapid-links and use high-strength slings or cord. A safety harness and a pair of ascenders with etriers (stepladders of nylon webbing) and/or empirical knowledge of Prusik-loop technique is essential. Suspended camping needs to be practiced, since the inexorable effect of gravity can nudge the usual mishaps toward disaster.

Besides eco-activist tree sitters, the other prong of development for hanging shelters has been biologists who work in forest canopies. Dr. Nalini Nadkarni, of Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, the president of the International Canopy Network (www.evergreen.edu/ican [website is no longer active]), kindly gave me several leads. An article on safe rigging, with a diagram of a line-tossing apparatus that grafts a Wrist Rocket slingshot onto a spinning reel, is “An Improved Canopy Access Technique,” by Gabriel F. Tucker and John R. Powell, Northern Journal of Applied Forestry, 8 (1), March 1991. Tree-climbing gear is available from Forestry Suppliers and from New Tribe.

Once you attain a major branch, you can rig separate slings for the shelter, keeping the main rope for ascent and descent. (In brown bear country, all anchors should be out of reach—the bear’s that is.) My third time out, I rigged the shelter high, then hauled my pack up and hung it from a branch like a swinging cupboard. After which I cooked soup on my hanging stove. Other happy adjuncts were a mesh gear loft and a Sierra Designs coffee sling.

Obviously, I’m fascinated by the whole arboreal riff, and wonder whether human evolution took a wrong swerve.

COLIN: For good reasons, we’ll consider the fundamentals of warmth retention in the Clothes Closet, not here. See The Prime Purpose of Clothes, this page, and The Fundamentals of Insulation, this page. If you can’t be bothered to check those pages, at least remember that sleeping bags, like clothes, are not to “keep the cold out,” as the old saying goes, but to conserve heat from the only available source—you; also that (although the distinction is less important than with clothes) the bag is not meant to make you as warm as possible, but to maintain thermal equilibrium—a state in which your heat production roughly balances your heat loss.

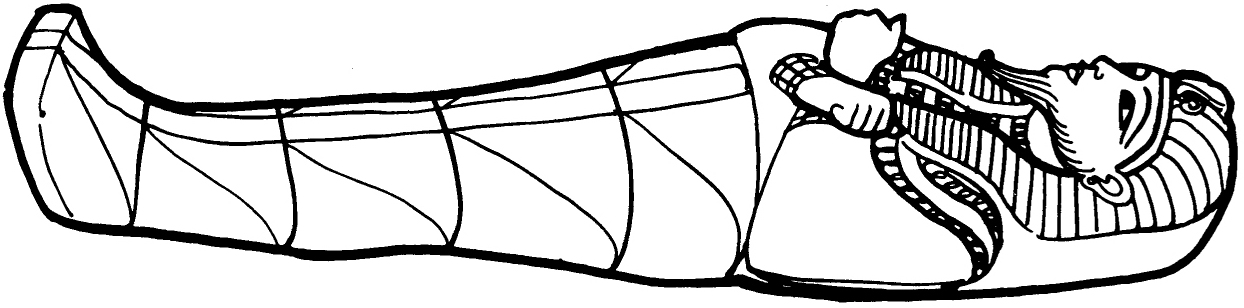

Ancient Egyptian mummy

Modern American mummy

Because the first sleeping bags clearly evolved from the idea of stitching two blankets together, they took the rectangular form of a bed. But most backpacking bags are now mummy bags—designed for human forms rather than for small upright pianos.

A few people say they feel uncomfortably confined in mummy bags. Claustrophobics may certainly face difficulties; but if you’ve given mummies a fair trial and just cannot get used to any real or imagined constriction, you don’t necessarily have to put up with the inefficiencies of the old rectangular piano-envelope. Although most backpacking bags are now distinctly form-fitting (in spite of a trend away from extreme sheathing), the catalogs still offer a continuum ranging from slim through mesomorphic to downright obese—some of these are tapered but unshaped—as well as old-style rectangular. Take your well-pondered pick. But remember that each size up means marginally greater weight and bulk. And, worse, that your body has to warm, all night long, a marginally greater volume of contained air.

CHIP: Between the strictly rectilinear and the infidel mummy lies a zone of compromise, known (depending on where you start) as either semi-rectangular or modified-mummy. Sensible persons once called these “barrel-shaped” bags, a term that now refers only to those without a permanently attached hood. The modified-mummy bags are tapered at head and foot, but not so closely as to be in any wise confining. But the enduring problem with all mummy bags is that real mummies, being dead, lie still on their backs. While backpackers, after a day of strenuous travel, don’t.

A significant change over the last decade is in the number of makers offering a line of sleeping bags designed for women; at present: Eastern Mountain Sports, Kelty, Lafuma, L. L. Bean, Recreational Equipment, Rokk, Sierra Designs, Slumberjack, The North Face, and Woods Canada Ltd. In general, women’s models have more insulation in the foot and/or torso. The cut is smaller in the shoulder and roomier at the hip. Linda gives high marks to the Sierra Designs Ella, a 0°-down bag with a womanly cut, and most of the women I ask who own these bags prefer them to unisex types, but there are also complaints. One athletic female friend bought (and returned) a bag that she claims was “overwomanized,” cut not for a kayaking, trail-running woman but for a steatopygous, Willendorfian Venus.*15

Rather than offering “womanized” bags, quite a few of the best companies urge you to look carefully not just at length but also at the girth measurements at the shoulder, hip, and foot. Once you’ve measured your own girth, the rule of thumb is to add 2 inches for a close fit, 4 inches for an average fit, and 6 inches for a loose one. For instance, my ultralight Western Mountaineering Iroquois Long has a close-fitting 60-inch shoulder, a 52-inch hip, and a 38-inch foot. While the cold-weather Puma Long measures 63-54-39: ample room for a layer of fleece inside.

COLIN: Some outdoor lovers complain that mummy bags don’t leave enough room for maneuver. Opportunists may face a problem here (though a local Don Juan advises: “You’d be surprised what has been achieved. As in all games, desire is very important”). Those who plan their amatory operations in advance should note that it’s now possible to order most mummy-bag models with zippers on opposite sides so that they’ll join convivially together. And any two bags with zippers of the same kind and length will conjoin—though the hoods will face opposite ways. See also doublers, this page.

A battened-down mummy bag is a very efficient heat conserver. Old-style rectangular envelopes gave your head no protection at all, tended to leave your shoulders exposed too, and let a great deal of precious body heat escape through the bag’s wide mouth. A mummy eliminates all these faults. When you pull on the drawstrings of the hood, the fabric curls around your crown and not only protects head and shoulders but also bottles the body heat. On a really cold night you pull on the drawstrings until the opening contracts to a small hole around nose and mouth. If, like me, you prefer to sleep naked because you wake feeling fresher you may sometimes find cold air seeping down through the hole and moving uncomfortably around bare shoulders. All you need do is wrap a shirt loosely around your neck (though see Hoods, Collars, Zippers, etc., this page). But this arrangement often holds the warm air in so well that you soon find you are too hot. To reduce the inside temperature (whether you’re using a neck wrap or not) simply slacken the hood tapes a little. That will make a lot of difference: your head dissipates heat more quickly than any other part of the body (also this page). (You won’t question this statement if you’re balding fast into coot country: you’ll probably, like me, have taken to wearing a balaclava at night.) In warm weather you can leave the tapes undrawn so that the mouth of the bag remains as open as in old-style envelopes. In hot weather you can go two steps further—if you have the right kind of bag. A mummy bag designed for use only in cold weather (that is, for polar exploration, high-altitude mountaineering, and winter hunting) may have no zipper openings. So do some ultralight bags. But although an uninterrupted shell is the lightest possible design and also conserves heat the most efficiently, such a bag is now very rare. It may do its special job well but it lacks versatility. In anything but chilly weather you’re liable to find yourself sweating even though the mouth of the bag is open—with no alternative except getting partly or wholly out. A zipper opening solves the problem, and nearly all bags now come with side zippers reaching the ankles or thereabouts. The modification is not pure gain. To prevent air passage through the closed zipper it has to be faced inside with a down-filled draft flap, or the zipper zone has to be blocked with a broad extension of the main wall that snugs in tight when you close the zipper. Or there may be two full-length zippers. But even a single zipper and its flap add several ounces to the weight of a bag, and, no matter how good the blocking device, there is bound to be a slight loss in heat-conserving efficiency, but if you expect to operate at times in temperatures much above freezing, then the very great gain in versatility is well worth such minor drawbacks. Some mummy bags have zippers that open all the way around the foot so that you can ventilate your feet as well as the rest of you—and can also convert the fully opened bag into a flat though markedly tapered down cover, very useful for warm nights in the bush and cold ones back home in bed. Almost all bags now have two-way zippers: you can operate the zipper from both top and bottom, and by opening it partway at shins as well as shoulders you gain a valuable aid in the almost nightly game of adjusting your bed to suit different and changing air temperatures (this page).

Of the major sleeping-bag components—fill, shells, and liners—

The fill

is what matters most. It must hold within itself as many pockets of air as possible, to act as an insulant between the warmed inner and cold outer air, and for backpacking purposes the best material is that which does this job most efficiently for the least weight. But there are subsidiary considerations: compactibility (the packed bag should not be too bulky); fluffability (the fill must quickly expand to its open, air-trapping state after being tightly packed); efficiency when wet; even, for a few people, possible allergic effects.

Traditional down-filled bags still dominate the high-quality field. But synthetic-filled bags, which have for years been nipping at their drawstrings, continue to make technical advances, and have just about caught up. Among high-quality bag makers, a few still stick exclusively with down. But most of the big producers have added synthetic lines or even gone all-synthetic.

Down is still the most efficient fill, warmth for weight. Compressed for packing, it’s markedly less bulky than any known synthetic fill. It also fluffs back to its open, air-trapping state more quickly and totally. When not compressed it free-flows, almost like a liquid, so that it continuously and evenly fills, in a way no current synthetic will, a space that’s always changing shape—as is a compartment in a sleeping bag. In addition, a good down-filled bag should, with real care, last 10 to 15 years, against 3 to 6 years for most current synthetics. On the other hand, down is useless when wet (synthetics retain at least some insulating property, and often most of it); once wet, it is difficult-going-on-impossible to dry in the field (synthetics dry much more readily); and over a long period of continual use, as in an expedition, dirt and repeated dampness tend to reduce its loft and therefore its efficiency (though see Gore-Tex shells, this page). Down, unlike synthetics, can also generate allergies in rare individuals. It demands rather more care in maintenance. And high-quality down is now murderously expensive: on the Asian wholesale market, 600-fill is $16 per lb., 700-fill is $27, and 775 is $30, versus $6 per pound for the best current synthetics.

It’s generally accepted that the best down comes from geese (mostly from China). Much learned discourse used to occur in catalogs and mountain shops—and to some extent still does—about the virtues of white versus gray goose down (probable ultimate verdict: the difference is either nil or very little), the adulteration of down with fluff (by law, “down” must be at least 80 percent down—that is, cluster and fiber rather than quills, beaks, etc.), and even the occasional perfidious sale of mere duck down under the name of “goose” (to be labeled “goose down,” 90 percent of the clusters must actually come from geese). All new bags bear a sewn-in label showing government specifications of the fill—the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) has ordained standards for down content and fill power. For some years, though, a generally accepted qualitative measure has been dampening this ongoing discourse. Fill power is not, thank God, yet another political rallying bleat: it shows the number of cubic inches an ounce of down will occupy. (The scale is not used for synthetics.) The best bag and garment makers use down with a fill power of 600, 700, or even 800, and somewhere in the blurb about their gear they will give the figure. Or should.

CHIP: Simply speaking, fill power comes from longer-tendriled, fluffier down clusters: 550-fill down has 56,000 clusters per ounce, while an ounce of 750-fill has 24,000. So good down takes up more space with the same weight of material. While there is no legal standard for fill power, the International Down and Feather Bureau recommends a test using a clear cylinder, marked with fill-power grades, with a 68.4-gram disk to gently compress the down. To reduce the variation owing to moisture content and packing methods, certified testing labs go through a five-day process of lofting and drying down samples, which means that the test batches are in optimal shape. Meanwhile, back at the plant, the down that goes into your sleeping bag is usually unconditioned. Thus, even down certified as 800-plus will give somewhat less than its rated performance after being crammed into a stuff sack and then lofted for a mere 10 minutes before you start butt-mashing it and sweating through it.

Even so, good down, in a well-made bag, has a distinctive resilience: poke it with your finger and it nudges back. Down also has amazing longevity. I have a bag made circa 1976 by Holubar of Boulder, Colorado, with 3 lbs. of down fill. I used it hard during 15 years of Forest Circusing, including six winters of snow sampling in the bitterly cold Wind River Range. I’ve washed it three times, always in special down soap, and except for a slight clumping in the hood, it’s still lofty and winter-fit after 25 years.

COLIN: Synthetic fills with fancy names and low prices have been around for years. For backpacking, I wouldn’t touch them with a walking staff. But the latest versions are a different kettle of fuzz.

Current trade names don’t matter too much: they’ll likely be gone tomorrow. But it’s worth knowing that there are three main kinds of fill presently in use and that at least one novel form lurks in the wings:

1. Long, continuous-filament fibers that cling together and are used in thick, cohesive sheets known as batts (usually rated by weight per square yard). A 5-oz. layer, uncompressed, is about 1 inch thick. Currently dominant: Polarguard (a solid-core fiber that depends on bounce for insulating capacity), Polarguard HV (with a triangular cross section that gives more insulating capacity and makes it more compressible), and Polarguard 3D (also triangular and hollow-core, but finer and softer). Other continuous-filament contenders include proprietary fibers such as Lamilite.

2. Much shorter, noncontinuous-filament fibers that can be used either in cohesive batts, much like the long-fibered layers, or in a more amorphous (i.e., chopped) form. Current trade names: Hollofil (a simple hollow-core), Hollofil II (with four channels), and Quallofil (seven channels and a silicone finish).

3. Even-shorter-fibered forms somewhat resemble down, though they may be partially bonded or come in batts. Names still being juggled include Lite Loft, Micro-loft, Primaloft, and Thermolite Extreme. Some get good reviews: Primaloft 2 is said to be “like down, but amazingly water-repellent.”*16

All three forms can be “lubricated” by spraying with silicone or other liquids to reduce the “boardlike” quality and make them feel more silky, more downlike.

It looks as if we are now not far away from a synthetic that warms and wears as efficiently as down, perhaps in a form that can also be blown into compartments. If so, it will revolutionize the sleeping-bag and down-garment field. As the R&D man for a leading maker told me years ago: “If and when we get the right synthetic it will destroy down—because of its price, because it stays warmer when wet, and because it will be easier to take care of.”

Thinsulate, a thin-fibered polyolefin/polyester synthetic insulation very popular in certain kinds of clothing (this page), did not prove suitable for sleeping bags. Ditto pile and fleece (this page), except for light, warm-weather bags. And foam bags seem to have faded into the night.

Two variations on the normal method of using fill now enjoy considerable vogue. Both appear mainly if not solely in down-filled bags.

One is simply to put 60 percent of the fill on top, 40 percent below—instead of the normal 50/50 division. Assuming a good insulating pad underneath, that makes theoretical sense: most of the heat you lose presumably escapes upward. But it seems to me that unless you tend not to move at all during the night, or always move the bag around with you when you do so (and some people apparently train themselves to do just that, even in mummy bags), then the “top” of the bag is by no means always on top. Most people lie at least part of the time on one side, and curled, so the underfilled portion tends to pull tight along your back—the most vulnerable area. That kicks a colander in the theory; but the fact is that many, perhaps most, down bags are now filled 60/40. Some, for mountaineering, even go 70/30 near the foot.

The second variation is to sew a shell with continuous baffles so that fill can be moved around, top to bottom. This is achieved by omitting the line of of blocking baffles that runs down the side of the bag opposite the zipper and keeps down from traveling, top to bottom, along transverse tubes (see next page). The idea is that in cold weather you shift down from bottom to top; in warm weather, vice versa. Satisfied users tell me it works, even when done in the dark. Frankly, I remain apprehensive of cold spots. But many bag makers now produce at least one model, usually a lightweight, built this way. Some, like Feathered Friends and Western Mountaineering, now use the down-shifting design for most of their bags, with block baffles reserved for the coldest-weather models.

The shell

Down demands one kind of internal construction; synthetics, quite another.

Down tends to move away from the points of greatest wear, notably from under your butt and shoulders (where it will be compressed and not very effective anyway) and also from the high point above your body (where, because heat rises, good insulation is vital). To minimize fill’s movement the shell is therefore divided into a series of self-contained tubes that keep the down from moving very far (see above). Because of a general tendency for down to migrate from the head toward the foot of a bag, transverse tubes work far better than longitudinal.

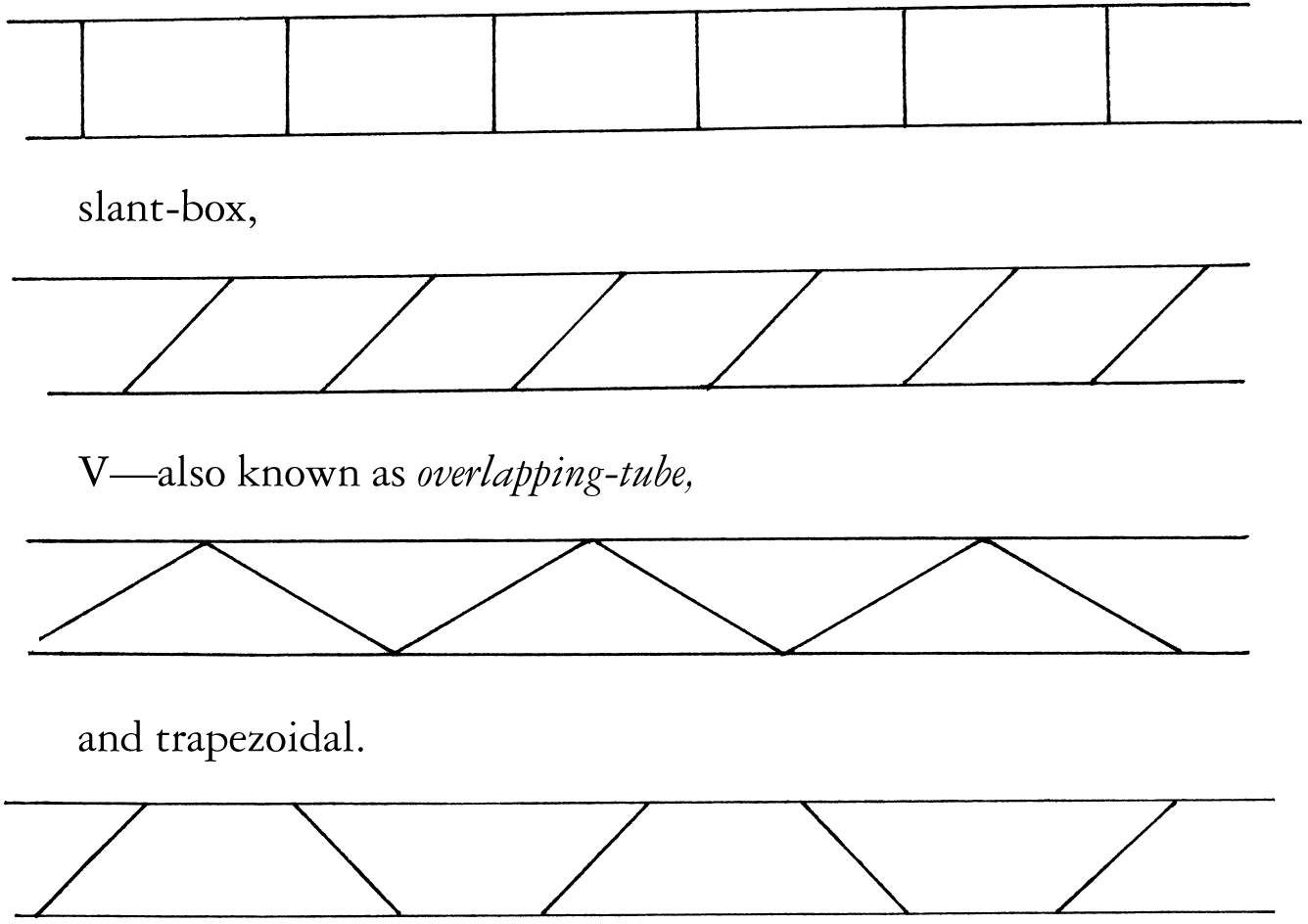

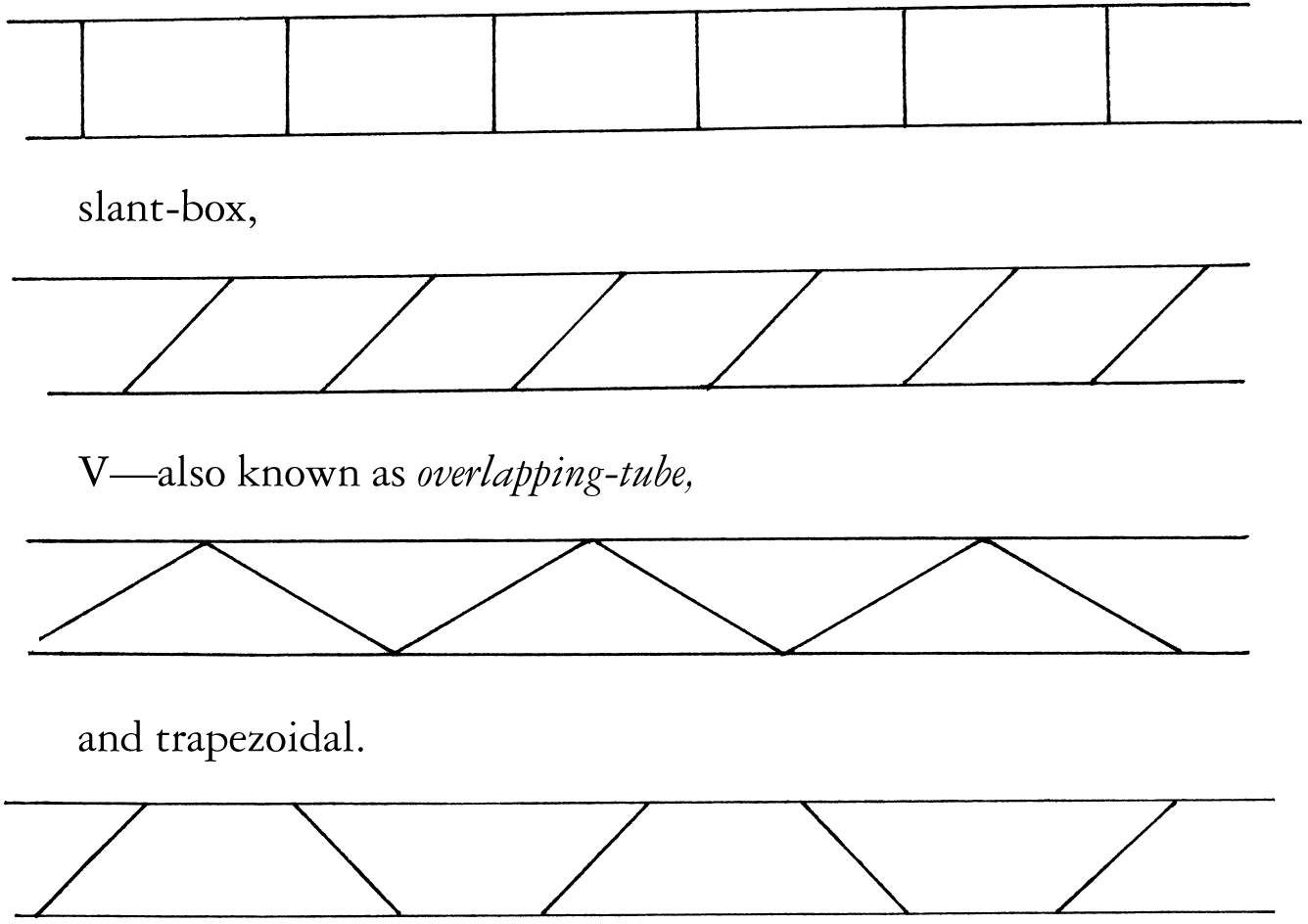

If tubes are made by simply stitching through the inner and outer walls of the shell you are left unprotected at the stitch-through points. If some form of batting is inserted at these points (a simple and cheap system) there’s some improvement. But not much. And except for a few ultralight models, all down sleeping bags now embody tube systems in which the tube walls—known as baffles—are constructed on one of four systems:

straight,

CHIP: These days, most top-notch bags have a differential cut (i.e., an inner layer with a smaller girth than the outer shell) with minor variations. The problem of maintaining the proper distance between the liner and shell around a tight curve—along the sides and at the head and foot—has made trapezoidal, or wedge, baffling popular. Yet another trick is for inner liners to be larger than outer shells, in what’s known as a reverse differential cut, for instance in a hood. The loose down-filled fabric liner is meant to expand around your face and forehead and seal out drafts. But one of my favorite bags is a box-quilted (that is, sewn-through) down ultralight, so when arguments rage over cut-and-bafflement, it pays to keep an open mind.

Simple transverse

Angled or chevron

As far as the visible geometry, transverse or chevron, the debate seems to have been resolved in favor of simple transverse tubes. The virtue of chevron-shaped baffles lies in preventing down shift while you sleep. But a chevron means more baffle material and longer seams, jacking up the cost. Canada’s Integral Designs makes high-quality chevron-style bags filled with Primaloft—a downy synthetic.

In good-quality down bags, the width (or spacing) of the baffles seems to have settled between 5 and 6 inches. Cold-weather bags with side-block baffles tend to use wider spacing. Several makers, Marmot for instance, vary the width, using narrower tubes through the heat-producing torso and wider ones in the heat-shedding head and foot.

The baffles themselves—invisible in a finished bag—are made of a light and usually unspecified synthetic. No-see-um mesh is often used, being tough, lightweight, and flexible. Recently, mildly elastic tricot baffles have been used by Marmot and others to add more give at the weak point—where the baffle connects to the inner shell. A high-stretch baffle first showed up on bags from Mont-Bell, a Japanese firm with elegantly functional designs that didn’t take hold in the U.S. But the idea was adopted under license by Sierra Designs. I’ve been testing one of these new bags and find that the flexy-stretchy system makes it more comfortable—for me at least.

COLIN: Long-fibered, continuous-filament synthetics, such as Polarguard, need no tubes. A single layer or combination of layers encircles the bag, with extra fill at the foot. Most such bags have quilt lines that look like baffle-tube seams, but in at least some cases they seem to be largely cosmetic: people are used to transversely sewn bags, say the makers, and demand “the down look.” Actually, the quilting of continuous-fiber synthetic to the shell increases costs and may slightly reduce insulation efficiency—though it can be argued that a floppy, unsecured shell would be a nuisance, especially on the inside. The important thing with such bags is edge stabilization, which simply means that the layers (or at least the outer layers) are sewn securely to the shell along their edges. Otherwise they tend to pull away and leave an insulation-ruining gap, and the insulation ends up twisting on itself.

Edge stabilization is equally important with shorter-fibered synthetics, such as Quallofil, when they’re used in batted layers. With such fills, quilting over the main surface is usually necessary—even when, as often happens, the batts have a lightweight scrim attached to one side to hold the material together structurally.

CHIP: Synthetic insulation is now arrayed in three main ways.

Quilting

1 .Quilting encloses the insulation liner and shell, then stitches through all three layers. This is okay on your bed in the house but productive of cold spots outdoors. A variation on the quilt method, used mostly in ultralight bags, is to stitch the insulating batt to the liner at regular intervals while sewing it to the outer shell only around the edges. An ultralight Austrian Gold-Eck bag I’ve used for some time is made this way, and it is far warmer than I expected it to be by the weight alone.

Shingling

2. Shingling laps one insulating batt over the next, like playing cards fanned out. This works on the same principle as slant baffles in down bags to eliminate cold spots. The drawback is that shingles can rip loose along the edges.

Layering

3. Layering follows the same principle as piling up blankets and quilts on your bed for a cold winter night. Potential combinations include two continuous batts, sewn at the edges; two quilted layers with the seams offset to prevent cold spots; or various hybrids: a shingled layer combined with a quilted one, or a quilted one with a continuous batt. Layered bags offer great warmth and durability—at a price. One of my favorite synthetic bags, the Cascade Designs Quantum O° (now sadly discontinued), had layers of Polarguard 3D under a seamless top.

Tuck-stitiching

Some makers tuck-stitch the seams: the fabric is tucked inside and stitched on the inside, so the thread is hidden—safe from abrasion, snagging zippers, cracked toenails, frayed clotheslines, and other destroyers. Tuck stitching, a mark of quality, also increases costs. But Sierra Designs reports that a change to tuck stitching reduced sleeping-bag seam repairs at the factory from one per week to about one a year.

I first heard about ground-level side seams from the original owner of Moonstone Mountaineering, who, like a circuit-riding preacher, visited retail stores himself. Early nylon-shelled bags had tops and bottoms the same width, with lengthwise seams halfway up the sides. But, for the same reason the top sheet and blankets on your bed need to be wider than your mattress, the upper insulating layers in a sleeping bag should reach ground level. This is critical in a down bag with side-block baffles, and no less in a synthetic bag with more insulation above than below. But, as Colin observes, the whole scheme depends on keeping the upside up. If you corkscrew all night, so do the rules of thermal engagement.

The materials used in sleeping-bag shells have changed more slowly than the insulation. Nylon taffeta still predominates, in the 1.6-to-1.9-oz.-per-square-yard range. Lightweight forms, with a fine denier thread (30) are indeed soft and sexy, and by virtue of a high thread count (300+ per inch) quite downproof and somewhat windproof as well. Found on deluxe bags, a light 1.4-oz. nylon taffeta called 30 Max (30d, 350 threads per inch) is treated with Teflon to increase water repellency. This is used for both shell and liner, or as the liner for bags with shells of Gore DryLoft or the new microfiber polyesters. Ultralite Ripstop, a 30-denier parachute nylon with 280 threads per inch that weighs a mere 1.1 oz. is showing up in sleeping bags from high-end makers like Western Mountaineering. It’s highly breathable and allows insulation to loft well but might tend to wear out more quickly.

A variety of polyester taffetas with trade names like Softech are available in shells and liners. Kelty’s warm Pepper Series Polarguard bags have all-polyester shells and liners. One advantage of polyester over nylon is that it feels warmer at first touch, easing those first shivery moments in a sleeping bag.

Gore DryLoft is a lamination of a PTFE (poly-tyranno-fluoridated egg whites?—see this page) membrane to a shell fabric. The original three-layer Gore-Tex was somewhat stiff and noisy for sleeping-bag shells, especially when cold. One dissenting reader compared it to “sleeping in a bag of popcorn.” Such complaints prompted the use of increasingly light and supple fabrics for the two-layer DryLoft. For instance, DryLoft 830 is faced with a 30-denier nylon fabric with 280 threads per inch, weighing 1.1 oz. per square yard, and complaints about noise now range from rare to nil. People who camp in drippy spots—the Maritime Provinces, the Pacific Northwest, snow caves—or who use partial shelters like tarps tend to revere DryLoft and equivalents. But it shouldn’t be thought of as a primary shield against the elements. One sticky problem with regular nylon taffeta is that it “wets out,” forming a vapor barrier that traps moisture in the insulating layer and at times freezes hard. Polar expeditions report progressive ice-ups that turned their sleeping bags into hard-shelled coffins weighing 30 lbs. or more. Since I often use a Gore-Tex bivouac bag, I’ve stuck to regular shell fabric for my sleeping bag. This comes from a suspicion (which a call to W. L. Gore & Associates did little to dispel) that it’s not a good idea to have more than a single layer of waterproof/breathable laminate. Now that Gore’s iron-clad patent has expired, a number of similar proprietary fabrics have appeared, This-Tex and That-Tex.

Internal reflective barriers like Texolite, Kodalite, and Orcothane have disappeared from sleeping bags as abruptly as they burst on the scene. Durability seems to have been an issue, along with moisture transport. Kelty’s Pepper Series bags have a silvery polyester inside (though I wonder if this doesn’t slow sun drying), and some vapor-barrier liners (this page), by definition nonbreathable, are reflective.

The newest trend in shells is microfibers. Also used extensively for clothing, the microfiber itself is a very fine nylon or polyester filament, a great many of which are combined to form a single thread. Thus, a 30-denier thread may incorporate 30 to 40 individual filaments. When the cloth is woven, the spaces between threads are so tight that the fabric is downproof, sheds water and wind, yet breathes. At around 1.7 oz. and 350 threads per inch, the microfiber used in sleeping-bag shells is lighter than what shows up in clothing. Pertex Microlight is a 1.3-oz. nylon microfiber (from Perserverance Mills in Padham, England) that spreads moisture over a broad area, to prevent nylon’s usual wetting out. Durable water repellent (DWR) treatments are applied to ducky it up.

A full go-round with fabrics would be incomplete without at least a bow to the question of color. Conventional wisdom is to make winter bags in the hottest colors, red and orange. Following the ROYGBV spectrum, yellow and green are 3-season models, with blue and violet for summer-weights. But color preferences are so stubbornly personal that retail stores tend to lobby makers vigorously for their favorite hues. At one company, Western Mountaineering, they got so tired of this that for a while they hung their booths at trade shows with all-black sleeping bags in protest.

My observations on color are two. Light shades quickly show dirt and body grime (especially unpleasing with liners), and dark ones, particularly black and dark green, help bags to dry out faster in the sun. So whatever opalescent hue the shell may be, I prefer (vigorously, reasonably) a jet-black liner.

COLIN: Hoods that encapsulate your head when drawn tight form an integral part of most modern mummy-bag shells. They are important: the human animal, with two of its major evolutionary features (brain and expressive face) housed in its head, naturally serves that member with a hugely complex blood-supply system. The capillaries often travel near the surface and are therefore subject to rapid cooling (the head, like a computer, requires a more or less constant temperature—which usually means it needs cooling). The old “facts”—that at 40°F it may, if unprotected, lose up to half your heat production, at 5° up to three-quarters—have been challenged; but there can be no doubt that it is the body’s prime heat-loss area. And perhaps too little attention has been paid to this problem in sleeping bags. Certainly, all hoods are not created equal, or even equal enough.

CHIP: The hood on my first down bag, an REI Skier, was a snap-on option. Like most hoods of that time, it was a flat U-shape edged with a drawstring that puckered it into a head shape. Sierra Designs (beginning with their Cloud Series) advanced the art with hoods shaped to surround the head. Warm-season bags may still have flat, U-shaped hoods or lightly contoured ones. But cold-weather bags, like the Kelty Serrano, have deeply contoured hoods with elastic brow bands or a second drawstring. Floating hoods, unconnected to the bag and thus allowing corkscrew sleepers some leeway, have faded out. The reverse-differential cut (this page), with more liner than shell, is often used. If you’re a wire-chinned chap, some nylon hood liners are so scratchy-noisy they actually keep you awake. Polyesters are quieter. Particularly silent (and warm-feeling) was the Microtherm polyester lining the hood of a Slumberjack Ranger I spent a few nights with. A new hood from Sierra Designs, called the NightCap, adjusts from a squarish fist-and-elbow-accommodating breadth to a rounded head shape with two drawcords. This combination does offer scope for eccentric sleeping styles. And it’s also a further step in resolving the mummy problem. In case you hadn’t noticed, most living people sleep not on their backs, faces toward heaven, but rather on their sides, with knees drawn slightly up.

COLIN: The drawstrings that pull the hood around your face and hold it there mostly come equipped with spring-loaded plastic toggles or other secure but quickly adjustable devices. Sometimes there are two such devices, one at each free end of the cord or tape, near the top of the zipper; but many bags now have a single toggle in the center of the hood on the opposite side from the zipper, so that you can adjust the hood with a single device instead of the two and need not loosen the drawstring if you want to open the top of the zipper (to cool off a little or to emerge briefly in the middle of the night to urinate). This arrangement means that the drawstring ends are anchored near the zipper top, one on each side, and when you tighten the hood you place strain on the zipper and may pull it open. The bag should therefore have a snap or Velcro fastener to take the strain and also keep the draft edge closed. (Velcro is easier to open and close than a snap but can, I hear, grab long hair or even beards.) One designer suggests that perhaps you really need two fasteners, each pulling at a slightly different angle.

CHIP: High on my list of unintended consequences is that sleeping-bag drawstrings and zipper pulls (often adorned with stiff, black nylon tabs) have a tendency to dangle inside the hood, poke me in the face, and summon evil dreams: for instance, kissing a porcupine’s arse. I cut these tiny assassins off and replace them with soft, light-colored cloth tape. The second unintended consequence is that the Velcro tabs used to keep zippers from gapping can damage light shell fabrics by hooking into threads and jerking them out of the weave. The only solution for this is to firmly engage all hook-and-loop fasteners before stuffing the bag, and to keep a weather eye when hanging the bag up to air: a loose tab flapping in the wind can wreak minor havoc.

COLIN: Built-in collars that fit across the sleeper’s chest and so reduce draft through the head opening are becoming more popular. They can be down-filled appendages or plain fabric. And while they may possibly reduce somewhat the bag’s flexibility in wide ranges of temperatures they undoubtedly help keep you warmer in real cold. Warmer, certainly, than any makeshift measures (this page).

CHIP: Here, the Mummy’s Curse strikes again—that is, the deeply lobed yokes seen on so many synthetic bags are designed for back sleepers (or the thermocouple-equipped manikins that companies use for tests). Those of us (the majority) who rest as we did in our maternal tummies do better with a simple, tubular draft collar that lets us roll freely from side to side without fussy realignments. Serious winter bags might have draft-collar tubes both top and bottom. But unless you summer on the summit of Denali, most above-freezing bags don’t need draft collars. One of my favorite hinge-season bags, the Sierra Designs Lewis, is a favorite precisely because it lacks one. My body heat tends to be low on retiring and to ramp up as the night proceeds, peaking about 3 a.m. At that point, I ventilate, which in a draft-collared bag means complicated yogic adjustments of the side zipper. And that in turn requires real thinking—sharply incompatible with renewed sleep. The draft-collarless Lewis lets me tug dreamily at the main zip and thrash my hands to open the top—back to sleep. So, despite the fact that at present this ranks with ranting against the probability of resurrection, I’d rather not have a puffy, air-blocking draft collar above 0°—Fahrenheit!*17

Zippers on bags, formerly gap-toothed nylon-eating marvels, are now almost all nylon-coil type. The best coil zippers are self-healing: if the teeth pull apart, you can zip down and back up and lo! you’re in business again (the first few times, anyway). For a diatribe on zippers-in-general see this page.

Where early saber-toothed zippers could chew their way through a considerable stretch of nylon, leaving plentiful exits for down fluff, the coil type merely snags and stops—so don’t force it. But ultralight fabrics can still get nastily gnawed, and thoughtful makers back the zipper with nonsnagging tape or sew a band of thicker fabric on the draft tube. Double sliders are standard, and desirable, letting you vent the foot without opening the entire flank to the elements. Also nice are swiveling pulls, with a U-shaped track on the slider to let one hangy-down serve both inside and out. Every zipper on every sleeping bag I’ve ever owned was made by YKK. But the WaterTight laminated polyurethane zippers showing up on parkas seem like a good match for DryLoft shelled sleeping bags, if they hold up.

Zippers have migrated. The infamous army duck-down mummies had a front-and-center zip that’s rarely seen these days. Early nylon bags tacked the zips along a side seam, halfway up. On bags with ground-level seams, zippers are mostly likewise, seeming always to end up underneath when you need a fast exit. Some designers now fetch the ground-level zips up toward your chin, for access reasons (but these are the worst as far as lip tickling). On at least one new bag (the Slumberjack Pumori), the zipper swoops clear across from right elbow to left shoulder—the sort of thing you either love or hate. Cascade Designs put the zip on their Quantum bags about 6 inches off the deck, where the side curves into the top. I’m a side sleeper, so this arrangement worked wonders for me, putting the zipper pull right at my fingertips though not right in my face and letting me vent freely without chilly gaps.

Current accessorizing includes upgrade hoods and insulated footsacks. On particularly bitter nights I’ve draped my down parka or vest over the foot of my bag, to the same effect. The new Sierra Designs bag I’m testing has four discreet loops sewn into the ground-level seams that mate up with the Pad Lock—four plastic clips and a lock on a length of light shock cord—to keep your pad where it belongs. Another clever extra is Mountain Hardwear’s zip-in expander, which adds 8 inches of girth—a boon to the pregnant (down or Polarguard, 12 oz., $50). Some bags have sprouted little Velcro-flapped goodie pockets. Mountain Hardwear’s Tallac bag includes a headnet that stuffs into a chest pocket, for rapid deployment. The only two items I’ve put in a sleeping-bag pocket are a flashlight and a handkerchief. Eyeglasses seem risky. Zip-together lovers might stash breath mints, tissues, and condoms. For the devout, the pocket could hold a compact Bible, Koran, etc. For the apprehensive, pepper spray.

Unless you hang your bag for storage, a necessary adjunct is a storage sack that protects without ruinously overcompressing the insulation, as a stuff sack does. These come with most high-quality bags, in cotton or mesh, or are easily found in shops. A king-size cotton pillowcase from a thrift store also serves.

Vapor-barrier linings (VBLs)

COLIN: VBLs have been around for years. But although embraced fanatically by a few they have not caught on. Some people, including me, still like them; others, including Chip, like hell do not.

For a brief summary of the theory behind VBLs, and some discussion of the practice, see this page. I have good reasons for attacking the matter there, in the Clothes Closet, rather than here; but understanding the theory so that you can practice properly is a major component of VBL usage, so I’m afraid you’ll have to read most of this page and this page if you’re to grasp the meat of what follows.

Both theory and practice are simpler with sleeping bags than with clothes, because in a bag you lie more or less still and your metabolic rate changes only very slowly (though the practice is complicated by your being mostly unaware of temperature changes, and the need to adjust, until cold or heat wakes you up). But even with VBL sleeping bags you must understand what you’re playing with—which is something very different from a conventional breathing-shell bag.

More than three decades ago I tried a VBL bag by Warmlite, a pioneer in the field, on a five-day test up to 12,000 feet and down to a windless 16°F. In a tent, wearing little or no clothing, I found I was far too hot, soon began to sweat, and simply could not adjust the rather complicated bag to an all-around comfort level. Now, the real trouble may have been the bag’s built-in foam pad. I normally lie first on one side, then on the other, moving the whole bag with me and thereby keeping any opened zipper to my front; but the built-in pad could not move with me and the opened zipper was, in one of my lying positions, bound to run close and cold to my curved back. (A reader later wrote that he’d had a similar unsatisfactory experience, and also thought the trouble was the built-in pad.) I had further minor difficulties too (though the makers assured me with heat that I had misused the bag). In the years since, I’ve met many people who have tried VBL bags and found them wanting. The reasons could lie in extraneous matters like that built-in pad or such personal idiosyncrasies as high metabolic rates. But I suspect that in many cases the bags were simply used in temperatures too high for the system. The maker of excellent VBLs once told me that he felt they were really not for use above 35°F. The difficulty is, of course, that many nights may begin much warmer than that but end up much colder. And one night may be much warmer, the next much colder, especially in the mountains. Bags with built-in VBLs are simply not versatile enough for such very common conditions.

The way to achieve versatility is fortunately simple: a removable VBL. I have for years carried one on all but the most guaranteed-warm trips. I’m convinced that it extends the low end of any bag’s comfort level by at least 10° and probably by 20°.

The price in weight and bulk is small; in money, very reasonable. I use a simple, coated ripstop half-sac (no longer available) by Moonstone of California that weighs 4.7 oz., takes up about as much room as a pair of jockey shorts, and cost $18. True, I normally also carry a matching VB shirt (6 oz., $35—see this page) and use it with the half-sac, but the shirt performs major daytime functions—and other warm torso clothing would often be enough in conjunction with the half-sac. By taking a bag that’s a tad on the light side for a given trip (or even several tads) and regarding the VBL as a reserve for cold occasions I can save considerable weight and bulk. And if temperatures drop markedly during the night I simply slip into the VBL, which I have put ready, inside the bag. My Moonstone half-sac extends up to my upper chest and is held there by an elastic “waistband.” Provided I wear polypropylene underwear (this page) I experience little or no damp or clammy feeling—and none of the uncomfortable wrapping around legs and torso that some people report with full-length liners. I find the half-sac particularly useful with a very light bag (this page).

Some sleeping bags have a snap or two to anchor an optional liner, and the makers tuck a VBL liner into the margins of their catalogs. Stephenson’s makes VBL items from a somewhat-stretchy urethane-coated 2.2-oz. nylon knit called Fuzzy Stuff, with the soft side skinward. Feathered Friends sells a VBL liner in four sizes (about 6 oz., $35–$37). For “extreme winter camping” Western Mountaineering sells the Hot Sac, 1.1-OZ. polyester with a shiny reflective lining (7 oz., $65), that can serve as an emergency bivouac bag. For a makeshift version, get an aluminized polyester “emergency bag” for $10 to $12, and try it with wicking long underwear and socks. (If the VBL aspect doesn’t thrill you, you can always use it as a groundsheet.)*18

But with removable liners we’re beginning to move over from traditional, more-or-less-one-purpose sleeping bags into

The idea is hardly new. One early approach was Warmlite’s “solotriple” bag that I described in The New Complete Walker (with two zipper-off topsides of different thicknesses that can be used alternatively or together, giving a solo sleeper three bags in one). Camp 7 for some years offered a lightweight synthetic-fill bag that could be used alone as a summer bag but would fit as an outer shell around any of Camp 7’s main line of down bags—boosting their warmth and also protecting the down from external moisture. A removable VBL greatly increased the cellar range of either bag or of both together.

CHIP: The zipper on my ultralight down bag is on the same side as the one on my 15°F model, so despite their being from different makers I now double them up—8 inches of loft—for really cold nights. But makers of real system bags offer a calculated fit, matching zippers, etc. Mountain Hardwear has a choice of a 40° down (2 lbs. 8 oz., $165) or 45° Polarguard HV mummy bags (2 lbs. 2 oz., $105), or a 50° Polarguard HV barrel-shaped bag (2 lbs. 10 oz., $115), to fit inside their 3-season models. The upgrade hood (6 oz.) seems like a necessary component. Feathered Friends, among others, make certain bags with systemic features: their Great Auk (2 lbs. 1 oz., $288) is a roomy 20° bag with a hood and a built-in pad pocket, designed to engulf a summer or 3-season model, with a 40° boost in its comfort rating. A slick 4-season combo is the Great Auk and a Feathered Friends Rock Wren (1 lb. 15 oz., $225), a unique summer bag with zippered armholes and a drawstring foot, that doubles as a full-body camp robe. With the Rock Wren, you can get up and make coffee without leaving your sleeping bag: scary. You can also augment the Rock Wren with a down parka and booties, for hard-core bivy sacking.

Any of four Wiggy’s sleeping bags, filled with a proprietary resin-bonded fiber called Lamilite, will fit into a hooded overbag that, alone, works to 35°F and adds roughly 40° to the rating of the inner bag. The Wiggy’s Ultralite (3 lbs. 8 oz., $146) is rated at 20° alone or to –20° with the overbag (2 lbs. 8 oz., $144).