Housekeeping and Other Matters

ORGANIZING THE PACK

COLIN: Every backpacker eventually works out his own way of stowing gear into a pack, and it will probably be the one that best suits his equipment and techniques. But beginners may find some usable guidelines in the solutions that Chip and I have evolved. Although many of these solutions have appeared in earlier chapters it seems worthwhile to mention them here, more neatly gathered together. What we’re trying to do, remember, is only to offer hints that may help beginners drift in the right direction: to provide guidelines, that is, not perpetuate idiosyncrasies.

The best way to stow your gear into your pack is to pursue, all the time, a reasonable compromise between convenience and efficient weight distribution.

For the main considerations in weight distribution and also the more precise requirements with I-frames, see this page.

Common sense and a lick or two of experience will soon teach you the necessary refinements: after some angular item such as the stove has gouged into your back a couple of times you’ll make sure, almost without thinking, that flat or soft articles pad the forward surface of the packbag’s main compartment; and once you’ve put both the full canteens that you’re carrying on the same side of the bag and found that the load then rides like a one-armed gorilla you’re unlikely to repeat the mistake.

If you use a compartmented packbag your ideas on where things should go will clearly differ from those of a bloody-great-sack addict like me. But as my experience is almost entirely sackish, and because on the rare occasions I’ve used compartmented bags I found that the general principles held good, I’ll speak purely from experience.

The most convenient way to stow gear varies from trip to trip, from day to day, from morning to evening. Obviously, the things you’ll want first at the next halt should go in last. So the groundsheet will normally travel on top. In dry country, so will one canteen—though in sunny weather it should be covered with a down jacket or some other insulator. And the balance-of-the-week’s-ration bag, the signal flare, reserve or empty canteens, and refills for a cartridge stove should—on the score of sheer convenience—languish down in the basement. Otherwise, the important thing is not where each item goes but that you always know where it is.

There’ll be variations, of course. If rain threatens, your raingear must be on top and perhaps even sticking out, ready to be plucked into use. On cold evenings, have your heavy clothing ready to put on even before you start to make camp. If it looks as though you’re going to have a long, torrid midday halt, make sure you don’t have to dig down to the bottom of the packbag for plastic sheet or poncho before you can rig up an awning. But all this is just plain common sense.

I pad the forward side of my packbag with the polyethylene sit pad, or a small clothing item, or the “office,” or with my camp shoes (soles facing out). In one forward corner of the main sack, fitting snugly against the packframe, go the gasoline container and usually, on top of it, the stove. If I’m carrying a second gasoline container and/or a portmanteau fishing rod, they fit into the opposite and similar corner.

There are few other firm rules for the main sack. Cooking pots and the food-for-the-day bag normally go side by side on the same level (because when I want one, I want the other), and they almost always ride high up. If space poses a problem a few small, allied, and relatively unharmable objects may travel inside the inner cooking pot, along with or in lieu of cup and spoon. Candidates include sugar and margarine containers, salt-and-pepper shaker—even my stove in its stuff sack. Otherwise, the packing arrangements depend largely on what items I expect to need next—given, of course, that I try to pack heavy articles close to the frame (see, again, this page).

Many smaller items in my pack—particularly in the kitchen—travel in plastic bags (this page). For stuff sacks, see this page and—for The Small-Stuff-Sack Fallacy—this page. Some people house almost everything in these light and convenient little bags; their packs become stuff-sack condominiums.

CHIP: Since, like Colin, I prefer undivided packs, the challenge is to assort the contents in some way other than a wholesale rummage. One good reason for stuff-sacking is that you can unload in rain or snow without wetting your payload. Having pitched camp several thousand times, I have a definite routine, as follows. First, I make sure of shelter. Quite often, I pack my sleeping bag, pad, bivy sac or groundsheet, and ultralight shelter (like the Integral Designs SIL-tarp, this page) in a single stuff sack or in the lower compartment (usually oversize for the lightweight sleeping bags I favor) of the I-frame pack. Beweathered, I can slide the shelter sack out and rezip the pack—no digging around. I keep dirt-magnet tent stakes in their own sack in an outside pocket. Then come food and drink. Pots, utensils, windscreen, and such have their own sack, with the fuel bottle in an outside pocket or plastic-bagged low and forward in the pack. The main food stash (subsacked in three or four 1-gallon zip-top bags) now occupies a Kevlar bear bag (Ursack, this page). Spare clothes go in an Outdoor Research Cell Block, a rectangular zippered sack perfect for flat-folded duds. Puffy bits like fleece pullovers fill space at the top of the pack, rendering them accessible. Small things from snacks to water filter to toilet tissue that I need en route go in the top pocket, while raingear and other bulk items go in the rear pocket. Constant needs, like notebook, pencil, bug slather, sunscreen, and lip balm, in the Possum Pocket office-on-the-yoke.

The three levels of access are: IMMEDIATE (Possum Pocket or front pockets, tucked into yoke straps, or in the mesh water-bottle sleeves that can be reached without taking off the pack), QUICK (top and outside pockets), and SECURE (protected inside the main packbag).

Aside from conventional weight-distributive wisdom, the precise placement also depends on the pack I’m using. Panel-loading or hybrid packs, with their easy access, give more latitude to arrange gear for optimum weight distribution. Mountaineering packs—tall, tubular, and top-loading—should be packed with a gimlet eye to the order in which things come out. Some packs have pockets perfectly tailored for awkward stuff—the Arc’Teryx Bora 95 I use for winter struggles has a full-length rear pocket that holds (and drains, via a bottom grommet) an iced-up tent and fly. These would otherwise get snagged, if tied on the outside, or melt-moisten all else, if stuffed in the main bag. Other problem gear best stowed outboard includes tent stakes, tent poles, ice axes and crampons, and fishing rods. Since these things most often come with their own sacks, stitching on a tab with paired D-rings or Velcro can wed them to your pack.

The ideal is to evolve a seamless relationship between your pack, your gear, and the sort of trip you prefer. The corollary is that the more variation you take on in gear and trips, the more likely you’ll be to have several packs. Which in turn means you’ll be constantly juggling the whats and wheres. If there’s a stunning disadvantage to testing many new packs, as this book demands, it’s that lack of stumble-around-in-the-dark familiarity with the house on your back.

COLIN: The only radical changes in organizing the pack come at

RIVER CROSSINGS.

Crossing small creeks is mostly a simple matter, and raises no problems. You can often make it across dry-shod, on the tops of boulders that are clear of the water or slightly awash. A staff to aid balance is often a godsend. If you’re wearing boots with no tread on the insteps you must make every effort to avoid the natural tendency of beginners, uncertain of their balance, to plant the instep of the boots on the curving summit of each boulder. Boots with treaded insteps make the need for such avoidance less obvious; but I still believe the ball of the foot is, in most cases, the part to plant—because it keeps you more delicately on balance.

Sometimes, of course, failing a natural log bridge or stepping-stones, you have to take off your boots and wade. At least, I do. Some people keep their boots on, but I mistrust the effect on boots and feet. Or perhaps I just mean that I abhor the idea of squelching along afterward. On easy crossings, carry your boots, with socks pushed inside. Knot the laces together and twist them around one wrist. On deeper crossings, hang the lace-linked boots on the pack. In really difficult places it’s safer to stuff them inside the packbag. Sometimes you can wade in bare feet, with safety and reasonable comfort; but if your camp shoes have good-grip soles and also dry out quickly you’ll often be glad to protect your feet in them.

A friend once suggested a method he uses regularly for fast and rocky rivers: take off socks, replace boots, wade river with well-protected feet, replace socks, and go on your happy and reputedly unsquelching way. Somehow, I’ve yet to try it out. I unfancy wet boots. If you’re fishing and have waders, the problem vanishes. A possible lightweight substitute: large plastic trash bags loosely tied over each leg.

CHIP: I’ve tried the socks-off/boots-on method. In shallow streams, if you dash across, it works well enough—if your boots are well waterproofed and also snug enough around the tops that water doesn’t funnel in. Otherwise, or in the event of repeated crossings, the insides of your boots will get wet: Blister City. A slicker approach is to carry synthetic-webbed sandals as camp shoes (this page) and use them to wade creeks, bogs, and other water hazards. Where coarse cobbles, continuous wading, and chill water combine to peg your pain meter, a pair of neoprene or waterproof/breathable (this page) socks will save not only your feet but in the long run your boots, which can ride high and dry in your pack.

COLIN: Provided you choose the right places you can wade surprisingly large rivers. (Fast rivers, that is, where the depth and character vary; slow, channeled rivers are normally unwadable.) It often pays to make an extensive reconnaissance along the bank in order to select a good crossing point. In extreme cases you may even need to detour for a mile or more. Generally, the safest places are the widest and, up to a point, the fastest. Most promising of all, provided the water is shallow enough and not too fierce, tend to be the fanned-out tails of wide pools. Boulders or large stones, protruding or submerged, in fairly shallow water may also indicate a good crossing place: they break the full force of racing water, and you can ease across the most dangerous places on little mounds of stone and gravel that have been deposited in the slack water behind each boulder. But always, before you start across, pick out in detail, with coldly cynical eyes, a route that looks tolerably safe—all the way. Try to choose a route with any questionable steps early, not over where you would, if turned back, have to recross most of the river. And avoid getting into any position you can’t retreat from.

Experience is by far the most important aid to safe wading (I wish I had a lot more), but there are a few simple rules. Use a staff—particularly with a heavy pack. (It turns you, even more crucially than on dry land, from an insecure biped into a confident triped.) In fast current the safest route for walking, other things being equal, is one that angles down and across the current. The faster and deeper the water, the more sharply downstream you should angle. The next-best attack is up and across. Most hazardous of all—because the current can most easily sweep you off balance—is a directly-across route.

Unless you’re afraid of being swept off your feet (and in that case you’d almost certainly do better to find a deep, slow section and swim across), wading doesn’t call for any change in the way you pack. But before you start across you should certainly undo your waistbelt. Always. The pack (at least until it fills with water) is much more buoyant than your body and should you fall in it will, if held in place by the belt, force you under. It’s easy enough to wriggle out of a shoulder yoke, particularly if it’s slung over only one shoulder. At least, I have always liked to imagine so, and a reader’s letter confirms my faith. She and her husband were wading a turbulent stream in Maine—waistbelts undone and hanging free—when she lost her bare footing and was swept downstream. She quickly squirmed free of the harness and within 50 feet, still hanging on to the pack, grabbed a boulder and pulled herself to safety. Afterward she realized that having her waistbelt undone had been “a great thing.”

The only other precaution I sometimes take when wading, and then only at difficult crossings, is to unhitch camera and binoculars from the packframe and put them inside the pack.

But if you have to swim a river you must reorganize the pack’s contents.*1

The first time I tried swimming with a pack was on my Grand Canyon journey, in 1963. Because of the new Glen Canyon Dam, 100 miles upriver, the Colorado was then running at only 1200 cubic feet per second—far below its normal low-water level. Even for someone who, like me, is a poor and nervous swimmer, it seemed comparatively easy to swim across a slow, deep stretch with little danger of being swept down over the next rapids. I adopted the technique developed by the one man who had been able to help me with much information about hiking in remote parts of the Canyon. Harvey Butchart was a math professor at Arizona State College in Flagstaff. He was also, his wife said, “like a seal in the water.” And he had found that by lying across his air mattress with the pack slung over one shoulder, half floating, he could, even at high water, dog-paddle across the Colorado—third-longest river in the United States and muscled accordingly. I tried his method out on several same-side detours, when sheer cliffs blocked my way, and by degrees I gained confidence in it.*2

The air mattress made a good raft. Inflated not too firmly, it formed a reassuring V when I lay with my chest across it. I used it first on a packless reconnaissance. Remembering how during World War II we had crossed rivers by wrapping all our gear in waterproof anti-gas capes and making bundles that floated so well we could just hang on to them and kick our way forward, I wrapped the few clothes and stores I needed in a white plastic sheet (this page) and lashed it firmly with nylon cord. It floated well. I found that by wrapping a loose end of cord around one arm I could tow it along beside me and dog-paddle fairly freely.

With the pack—an E-frame—dog-paddling turned out to be a little more restricted but still reasonably effective. The pack, slung over my left shoulder and half-floating, tended at first to keel over. But I soon found that I could hold it steady by light pressure on the lower and upper ends of the packframe with buttocks and bald patch. It sounds awkward but worked fine.

My staff floated along behind at the end of 3 feet of nylon cord tied to the packframe. Everything else went into the pack. I had waterproofed the seams of the packbag rather hurriedly, and I found that water still seeped through. So into the bottom of the bag went bulky and buoyant articles that water couldn’t damage: canteens, cooking pots, and white-gas container. Things better kept dry went in next, wrapped in the white plastic sheet. Items that just had to stay dry went on top, in what I thought of as the sanctum sanctorum: camera and accessories, flashlight and spare batteries, binoculars, watch, writing materials, and toilet paper. I tied each of these items into a plastic bag, rolled them all inside the sleeping bag, and stuffed it into the big, tough plastic bag that usually went around the cooking pots. Then I wrapped the lot in my poncho. Before strapping the packbag shut I tied the ends of the poncho outside the white plastic sheet with nylon cord. (On one trial run the pack had keeled over and water had run down inside the plastic sheet, though the sanctum had remained inviolate.) On the one complete river crossing that I had to make, nothing got even damp.

This system, or some variation of it, should prove adequate for crossing almost any river that is warm enough, provided you don’t have to go through heavy rapids. I am more than half-scared of water and a very poor swimmer, and if I can succeed with it almost anyone can. The great practical advantage of this method is that you don’t have to carry any special equipment. All you need is an air mattress, a poncho, and a plastic sheet or a groundsheet.

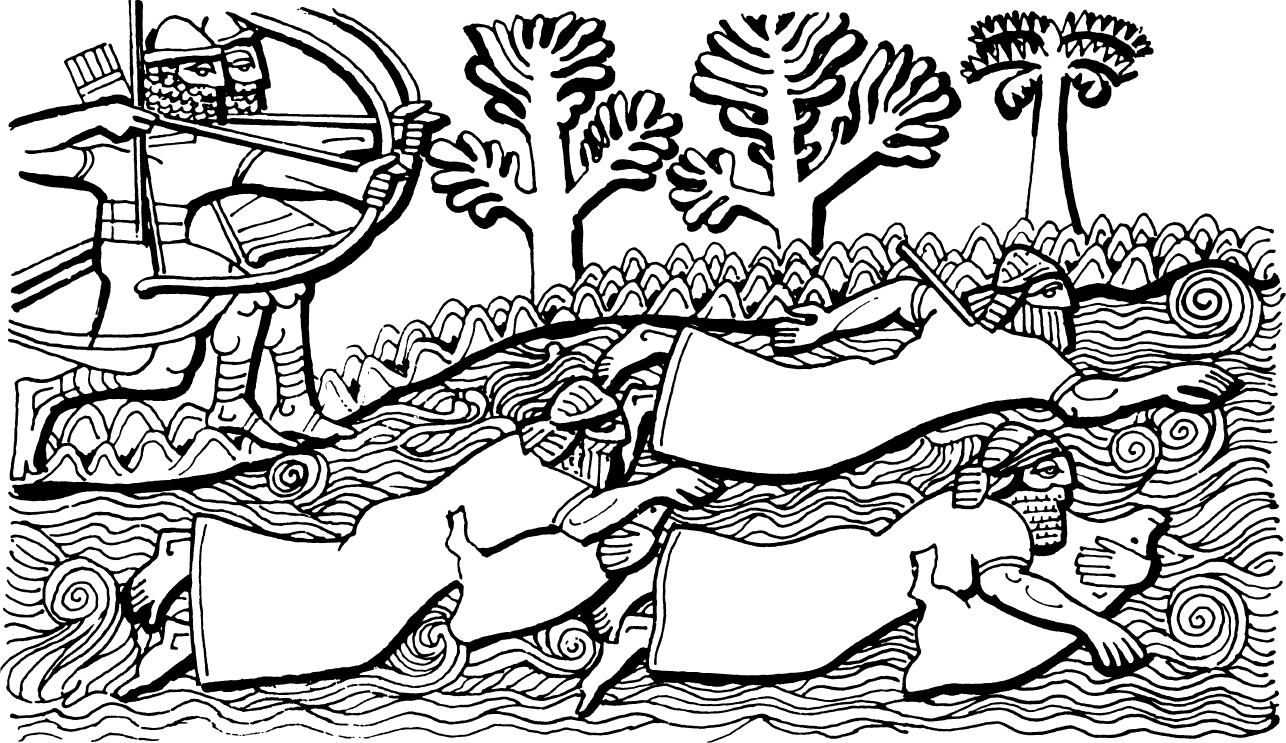

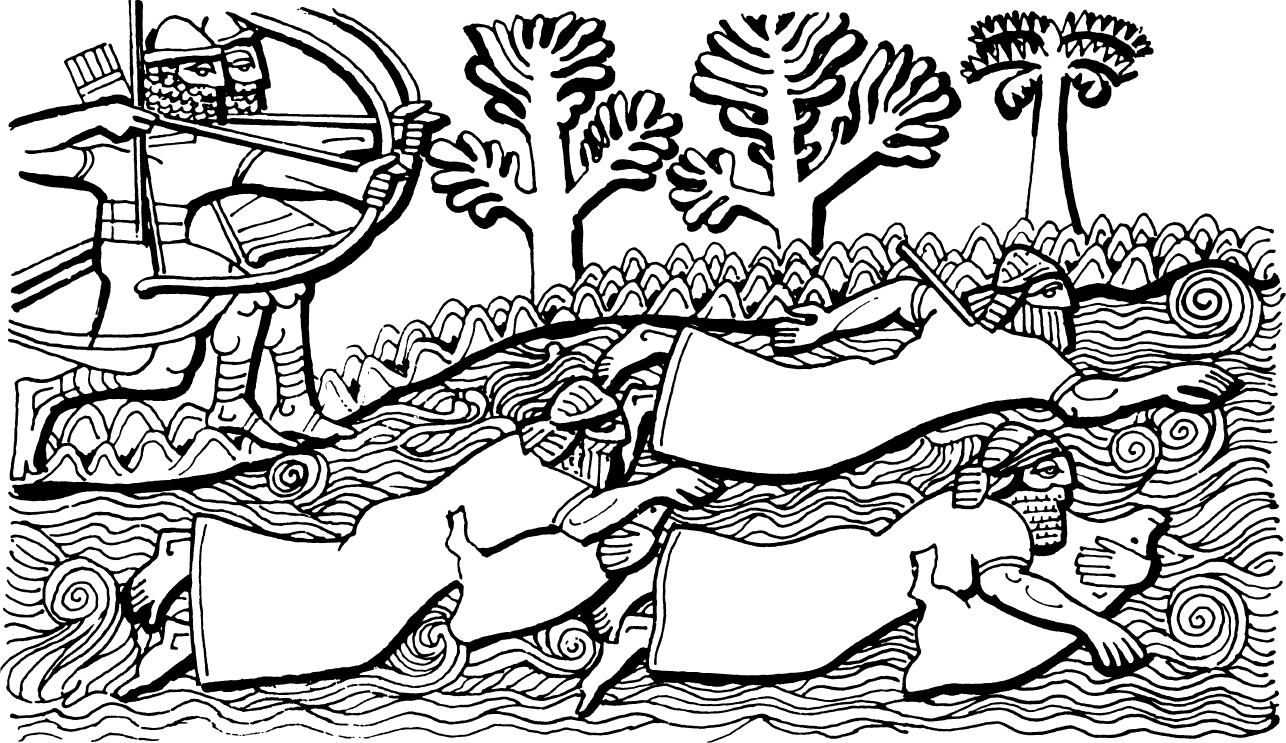

The method, by the way, turns out to be less than brand-new. A Washington State reader has shared this depiction of troops crossing a river on inflated skins—from an Assyrian relief of about 800 B.C.

Heavy rapids present a different problem. In May 1966 I took a two-week hike-and-swim trip down 70 miles of the Colorado, in Lower Grand Canyon. Although many people had run the Canyon by boat it seemed that everyone had until then had the sense to avoid attempting this very enclosed stretch on foot; but I knew from boatmen’s reports that even if the route proved possible I would almost certainly have to make several river crossings. I also knew that, with the reservoir now part-filled behind Glen Canyon Dam, the river was racing down at an average of about 16,000 cubic feet per second—more than 12 times its volume on my 1963 trip. That meant I would almost certainly be carried far downstream each time I attempted a crossing. Even the calmer stretches would be swirling, whirlpooled horrors, and I’d probably be carried through at least some minor rapids. Under such conditions I wasn’t willing to risk the lying-across-an-air-mattress technique, and I evolved a new method, more suitable for a timid swimmer.

Just before the trip I bought an inflatable life vest (by Stebco—no longer available). It was made of bright yellow rubberized cotton fabric, with a valve for inflation by mouth and also a small metal cartridge that in an emergency filled the vest with carbon dioxide the instant you pulled a toggled cord. The vest yoked comfortably around the neck so that when you floated on your back your mouth was held clear of the water. When I tried it out in a side creek as soon as I reached the Colorado, I found that I could also swim very comfortably in the normal position. From the start I felt safe and confident.

I’d already decided that rather than lie across the air mattress I would this time rely solely on the life vest to keep me afloat—partly because I was afraid the vest’s metal cartridge or its securing wire might puncture the mattress, but even more because I didn’t fancy my chances of staying on the mattress in swirling water. (A young fellow crossing the Colorado on a trip with my math-professor friend had been swept off his mattress by a whirlpool and had drowned.) I decided that in fast water the trick would be to make the pack buoyant in its own right, and just pull or push it along with me.

The coated nylon fabric of the packbag was fully waterproof but, although I’d applied seam sealant, water still seeped in. So I decided to try to keep the pack as upright as I could in the water and stow the really vital gear, well protected, up near the top. First, for extra buoyancy high up, I put one empty plastic quart-size canteen in each of the upper sidepockets. Into the bottom of the bag as ballast went the two cooking pots and two half-gallon canteens, all filled with water. Next I lined the remaining space in the main sack with my transparent polyethylene groundsheet and left the unused portion hanging outside. Like all groundsheets, mine had developed many small holes, but I figured it would ward off the worst of any water that might seep in from the upper seams or under the flap, and that what little did get through would collect harmlessly in the bottom of the pack. The items that water couldn’t damage (this page) went in first. Next, those preferably kept dry. Then I made the sanctum sanctorum. Into the white plastic sheet (because rain was unlikely, I carried no poncho this trip) went all the things that just had to stay dry (as on this page). Most of them were additionally protected inside an assortment of plastic bags. I lashed the white bundle firmly with nylon cord, put it on top of everything else, then folded over the unused portion of the groundsheet that was still hanging outside and carefully tucked it in between the main portion of the groundsheet and the packbag itself. I knotted down the pack flap, tight. Then I partially inflated my air mattress and lashed it securely with nylon cord to the upper half of the pack, taking care to keep it central. Finally, I took the 4-foot agave-stem walking staff that I’d cut at the start of the trip (this page) and wedged it down into the cross-webbing of the packframe, close beside one upright.

I held the pack upright in the water for several minutes, forcing it down so that water seeped in and filled the bottom 7 or 8 inches—thereby helping, I hoped, to keep the pack upright. Then I slid down into the river beside it. With my left hand I grasped the lowest crossrung of the packframe and pulled downward. Provided I maintained a slight downward pressure (see illustration) the pack floated fairly upright, though tending to lean away from me, and I was free to swim in any position with one arm and both legs.

In addition to the inflatable vest I wore my ultralightweight nylon swimming trunks (this page). I’d brought them because at the start, at the side creek in which I practiced, there was a possibility of meeting people. But I found that I actually wore the trunks on all crossings—to give me at least some protection from the sun if I became separated from the pack. And so that I could still light a fire in that unlikely event, I tied the waterproof matchsafe (this page) onto the vest.

The whole rig worked magnificently. I made four crossings. The white plastic sheet hardly ever got damp, even on the outside, and the sanctum remained bone-dry, every time. So, mostly, did all other items stowed near the top of the pack. Because I could swim freely, I always got across the river reasonably fast. Each time I could have landed within half a mile of my launch site; but twice I allowed myself to be carried a little farther down to good landing places. (And as I floated down the calmer stretches on my back, with both feet resting on the packframe in front of me—my mind and body utterly relaxed, and an integral part of the huge, silent, flowing river—I found that I had discovered a new and serene and superbly included way of experiencing the Grand Canyon of the Colorado.)

I also made two same-side river detours around impassable cliffs. And one of these detours was the high point of the trip.

For the first 50 feet of the rapid I had to go through (Lower Lava Falls), the racing water battered on its left flank into a jagged rockwall. I knew that the thing I absolutely had to do was to keep an eye on this rockwall and make sure that if I swung close I fended off in time with arm or pack or legs. From the bank, the steep waves in the heart of the rapid didn’t look too terrifying: not more than 3 or 4 feet high at most. But throughout the double eternity during which I swirled and wallowed through those waves—able to think of nothing except “Is it safe to grab a breath now, before I go in under that next one?”—I knew vividly and for sure that not one of them was less than 57½ feet high. And all I saw of the rockwall was a couple of split-second glimpses—like a near-subliminal inner-thought flash from a movie.

I missed the rockwall, though—through no effort of mine—and came safely through the rapid. A belch or two in midriver cleared the soggy feeling that came from the few mouthfuls of Colorado I’d shipped; and once I got into calmer water and had time to take a look at the pack it seemed serenely shipshape. (In the rapid, frankly, I hadn’t even known that I was still hanging on to it.)

The only problem now, in the fast water below the rapid, was getting back to the bank. It took me a full mile to do so.

At first I had to stay in midriver to avoid protruding rocks at the edge of another and only slightly less tumultuous rapid. Then, after I’d worked my way close to the bank, I was swept out again by tailwash from a big, barely submerged boulder. Almost at once I saw a smooth, sinister gray wave ahead, rising up out of the middle of the river. I knew at once what it was. Furiously, I swam toward the bank. A few strokes and I looked downstream once more. The wave was 5 times closer now, 10 times bigger. And I knew I could not avoid it. Just in time, I got into position with the pack held off to one side and my legs out in front of me, high in the water and slightly bent. Then I was rising up, sickeningly, onto the crest of the wave. And then I was plummeting down. As I fell, my feet brushed, very gently, over the smooth, hard surface of the hidden boulder. Then a white turmoil engulfed me. But almost instantly my head was out in the air again and I was floating along in calmer water. For a moment or two the pack looked rather waterlogged; but long before I made landfall, a couple of hundred yards downstream, it was once more floating high. When I unpacked I found the contents even drier than on some of the earlier and calmer crossings.

After those rapids and that boulder, I feel I can say that my fastwater river-crossing technique works.

That trip was something of a special case, but it taught me a useful lesson: if you have to swim a river, and have no air mattress and no inflatable vest, rig your pack somewhat after the manner I did. It will float buoyantly, and vital items will travel safely in the sanctum sanctorum. (I’m fairly sure my air mattress didn’t “float” the pack, but only helped hold it upright at stressful moments.) Pull down on the bottom crossbar of the frame and swim alongside or in front or behind (in swirling water you’ll do all three within seconds). A fair swimmer would have no difficulty, I imagine, in any reasonably unbroken water. And if, like me, you’re a weak swimmer you could almost certainly keep yourself afloat and moving across the current by just hanging on to the pack and kicking. But if it’s at all possible, try out unproven variations like this beforehand—preferably well ahead of time; or, failing that, in calm, safe water before the main attempt.

A reader suggests that for short emergency swims “a pair of tough (3 mil) plastic bags, blown up and tied or secured with rubber bands or nylon string, are very handy” for pack or person.

Don’t forget that water temperature can be treacherous in river crossings. Even when you’re wading, cold water can numb your feet and legs to danger point with astonishing speed. And no one can swim for long in liquid ice—can’t even live in it for very long. Yet your body will work efficiently for a considerable time in 50°F water. During my 1963 Grand Canyon journey the Colorado River temperature was around 60°. On the 1966 trip it averaged about 57°, and although the water always felt perishing cold when I first got into it (which was hardly surprising, with shade temperatures rising each day to over 100°, and precious little shade anywhere) I was never once, even on the longest swim, at all conscious of being cold.

CHIP: There’s an ingenious what-the-hell streak in Colin’s tale that appeals to me, especially in these times of prefabricated solutions and trumped-up adventures.

In any event, nouveau gear has made deepwater crossings a lot less laborious. Available from paddling and rafting suppliers are waterproof drybags that will swallow a large pack. Cascade Designs and others make drybags with straps and hipbelts that can stand in for a regular pack (sort-of-ly anyhow—the ones I’ve tried are bad monkeys with any load over 35 lbs.—see this page). And VauDe, a German firm, makes a comfortable full-suspension internal-frame backpack with waterproof roll closures (also this page).

Along with river crossings, the application is canyoneering, a specialized form of backpacking through narrow canyons where pools, cascades, and even waterfalls are part of the route. Besides tumbles, flash floods are the major hazards. Several mass drownings—of Boy Scouts and guided parties—have recently made the news. Most who died resolutely ignored both weather warnings and common sense—I’d study a map of the entire watershed and err on the side of caution. I’ve relished some multiday walk/wade/swims on the Colorado Plateau with no mishaps, except mild tendinitis from cold spring runoff. The Fletcher pack-floating method holds true, with a drybag much more buoyant and rugged than a wrapped E-frame (most drybags float a damn sight better than they carry). If you wear a neoprene wetsuit for cold water, you can also use it to cush up your sleeping pad at night (direct contact, though, will dampen your sleeping bag).

Since people throw in a rope for stream crossings without much idea how to use it, the other observation is that it’s screamingly easy to get into trouble, especially where there’s a fast current and any sort of obstruction: boulders, down trees, or brush. If you lasso a tree, tie the rope around your waist, and launch straight across, you can get jerked off your feet and end up spinning like a trolling lure, unable to disengage. A short course in belay technique or whitewater rescue can hone your applied-physics grasp of what’s what.

Two friends who carried a rope on a go-for-broke snowmelt traverse in the Wind Rivers ended up using it only once: to lash a log between the top fork of a cottonwood tree and a cliff, about 30 feet above a raging creek. There was just enough rope left to belay the scary balance-beam steps across. “Falling wasn’t an option,” said one afterward.

SANITATION

COLIN: (Note: Except for the paragraph on trowels, this section stands much as I wrote it 30-odd years ago. But it’s now 30 times as important: our burgeoning numbers have had hideous impact. See, sadly and specifically, giardiasis, this page. The ignorance of some newcomers about how to operate in wilderness has made a sad, self-righteous mockery of my words about the respect normally accorded the earth by those who undertake demanding journeys, but I’ll let the words stand, as a goad.)

Sanitation is not a pleasant topic, but every camper must for the sake of others consider it openly, his mind unblurred by prudery.

At one extreme there’s the situation in which permanent johns have been built. Always use them. If they exist, it means that the human population, at least at certain times of year, is too dense for any other healthy solution. (The National Park Service calculates that 500 people using a leach-line-system permanent john will pollute a place no more than one person leaving untreated feces, even buried.)

A big party camping in any kind of country, no matter how wild, automatically imposes a dense population on a limited area. They should always dig deep latrine holes and, if possible, carry lime or some similar disinfectant that will counteract odor, keep flies away, and hasten decomposition. And they must fill holes carefully before leaving.

A party of two or three in a remote area—and even more certainly a man on his own—must make simpler arrangements. But with proper “cat sanitation” and due care and consideration in choice of sites, no problem need arise.

“Cat sanitation” means doing what a cat does, though more efficiently: digging a hole and covering up the feces afterward. But it must be a hole, not a mere scratch. Make it at least 4 or 5 inches deep, and preferably 6 or 8. But do not dig down below topsoil into inert-looking earth where insects and decomposing bacteria will be unable to work properly. In some soils you can dig easily enough with your boots or a stick. I used to carry my sheath knife along whenever I went looking for a cat-john site, and used it if necessary for digging. Then I came across one of the plastic toilet trowels (10 inches long, 2 oz., $2) that now appear in many catalogs. At first I was merely amused. But I found that the trowel digs quickly and well and means you can cat-sanitate effectively in almost any soil. Now I always pack it along. Because these little trowels remind as well as dig, I’m tempted to suggest they be made obligatory equipment for everyone who backpacks into a national park or forest. I resist the temptation, though—not only because (human nature being what it is, thank God) any such ordinance would drive many worthy people in precisely the undesired direction but also because blanket decrees are foreign to whatever it is a man goes out into wilderness to seek, and bureaucratic decrees are worst of all because they tend to accumulate and perpetuate and harden when they’re administered, as they so often are, by people who revel in enforcing petty ukases. Anyway, a rule that’s impossible to enforce is a bad rule. And this one has been tried: a young reader of 89 has drawn my attention to Deuteronomy 23, verse 13 (see Appendix VI, this page).

Your kosher plastic paddle can come in useful, by the way, when you have to melt snow for water (this page). Conversely, a 10-inch, angled aluminum snow-peg (this page) makes a fair toilet trowel: for digging in hard soil, pad it at the top with your ubiquitous bandanna.

In the double plastic bags that hold my roll of toilet paper lives a book of matches. I tear one match off ready beforehand and leave it protruding from the book, so that I need handle the book very little; and unless there’s a severe fire hazard, when I’ve finished I burn all the used paper. The flames not only destroy the paper but char the feces and discourage flies. Afterward I carefully refill the hole. Unless the water situation is critical I have soap and an opened canteen waiting in camp for immediate hand-washing.

A hardy friend of mine suggests as substitutes for paper “soft grass, ferns, and broad leaves, and even the tip of firs, redwoods, etc.”

In choosing a john site, remember above all that you must be able to dig. Rock is not acceptable. Rock is not acceptable. Rock is not acceptable. I am driven to reiteration by the revolting memory of a beautiful rock-girt creek in California, a long hour from roadhead but heavily fished and traveled. And that raises the only other absolute rule: always go at least 50 feet, and preferably 500, from any watercourse, even if currently dry. Soil filters; but it demands time and space. The rest is largely a matter of considering other people. Wherever possible, select tucked-away places that no one is likely to use for any purpose. But do not appropriate a place so neatly tucked away that someone may want to camp there. A little thoughtful common sense will be an adequate guide.*3

All other things being equal, choose a john with a view.

In deep snow there’s unfortunately nothing you can do except dig a hole, burn the paper, cover the hole, and afterward refuse to think about what will happen come hot weather. There’s not much you can do, either, about having to expose your fundamentals to the elements. Actually, even in temperatures well below freezing, it turns out to be a surprisingly undistressing business for the brief interval necessary, especially if you have a tent to crawl back into. Obviously, blizzard conditions and biting cold may make the world outside your tent unlivable, even for brief intervals, but a good-size vestibule would solve this problem. For footwear when scrambling out of a tent in snow, see this page.

It’s horrifying how many people, even under conditions in which cat sanitation is easy, fail to observe the simple, basic rules. Failure to bury feces is not only barbaric; it’s a danger to others. Flies are everywhere. And the barbarism is compounded by thoughtless choice of sites. I still remember the disgust I felt when, late one rainy mountain evening several years ago, I found at last what looked like an ideal campsite under a small overhanging rockface—and then saw, dead center, a cluster of filthy toilet paper and a naked human turd.

That rockledge was in a fairly remote area. The problem can be magnified when previously remote countryside is opened up to people unfit to use it. Powerboats now cruise far and wide over Powell Reservoir—officially Lake Powell—behind the Colorado’s Glen Canyon Dam, and the boats’ occupants are able to visit with almost no effort many ancient and fascinating Indian cliff dwellings. Before the dam was built these dwellings could be reached only by extensive foot or fastwater journeys. Now people who undertake such demanding journeys have usually (though not always) learned, through close contact with the earth, to treat it with respect—and powerboats do not bring you in close contact with the earth. I hear that most of the cliff dwellings near Powell Reservoir have now been used as toilets.*4

Urination is a much less serious matter. But dense and undisciplined human populations can eventually create a smell, and although this problem normally arises only in camping areas so crowded that you might as well be on Main Street, it can also do so with locally concentrated use, especially in hot weather and when the ground is impervious to liquids. During my first Grand Canyon journey I camped on one open rockledge for four days. As the days passed, the temperature rose. On the fourth day, with the thermometer reaching 80°F in the shade—and 120° in my unshaded camp—I several times detected whiffs of a stale odor that made me suspect I was near the lair of a large animal. I was actually hunting around for the lair when I realized that only one large animal was living on that rockledge.

But urination is usually no more than a minor inconvenience—even for those who, like me, must have been in the back row when bladders were given out. An obvious precaution is to cut down on drinking at night. No tea for me, thank you, with dinner. Yet I rarely manage to get through a night undisturbed. Fortunately, it’s surprising how little you get chilled when you stand up for a few moments on quite cold nights, even naked. I go no farther than the foot of my sleeping bag, and just aim at the night (hence the “animal lair” at that rocky Grand Canyon campsite). A distaff reader wrote asking if I have any useful advice for her on this subject. Regretfully, I could offer only commiseration. But technology has now leapt into the breach (or breeches—see Chip’s portion below).

And a man wrote reminding me of the Eskimo who “reaches for his urinal and without leaving the bag captures another increment for tomorrow’s emptying ceremony.” I duly bought a widemouth plastic bottle and have used it with total success, kneeling up, in a tent. But not, oddly enough, lying down in my bag, à la Eskimo: I find I plain fail to produce. Such a block is apparently not uncommon among the house-trained.

CHIP: The pee-jug is a winter-mountaineering institution—and so are tales about leakage, explosion-by-freezing, and the like. Meanwhile Campmor carries the Little John portable urinal for $6 and the Travel John with an “absorbent pouch that turns urine…into a biodegradable, odorless, self-contained Gel Bag for spill-proof disposal,” also $6—reader comment invited. For womyn and grrrls, two devices in the Campmor catalog offer, if not perfect delicacy, at least some distance: the Freshette system is a form-fitting funnel that can be used with a tube for stand-up gigs or with special disposable bags in a tent (with pouch and 12 bags, $20). Similar but bagless is the Lady J, “for situations where restroom facilities are unavailable or unsanitary” ($7).

Only a minority of women readers seem to have tried these devices, and those I asked either raved (awesome!) or abominated (disgusting, never again!). The problem, one user informs me, is this: “If your rate of flow into the thing exceeds the outflow through the nozzle, you’ll wet yourself—and then have to deal with both a dripping funnel and dripping pubes.” My questions about aim were shrugged off.

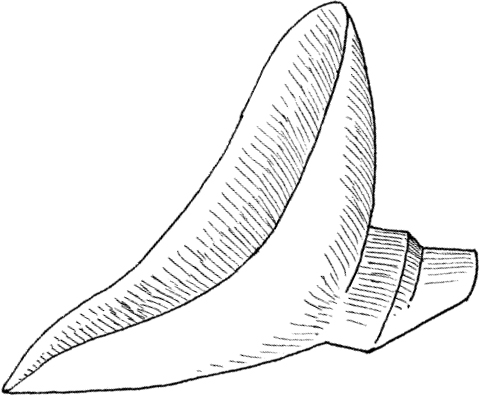

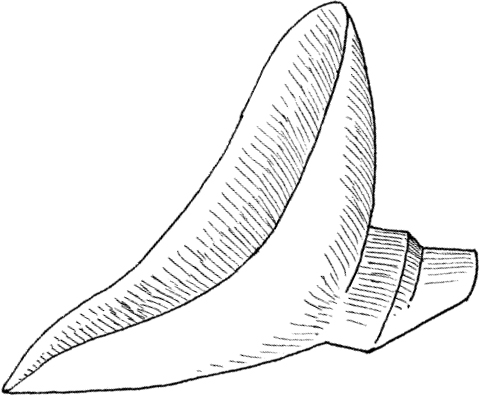

Lady J

A related and more popular development is clothing with strategically placed zippers, such as the P-System tights and pants from Wild Roses (this page).

A full-monty technical update (and light scatological humor) can be found in Kathleen Meyer’s instant classic How to Shit in the Woods: An Environmentally Sound Approach to a Lost Art.

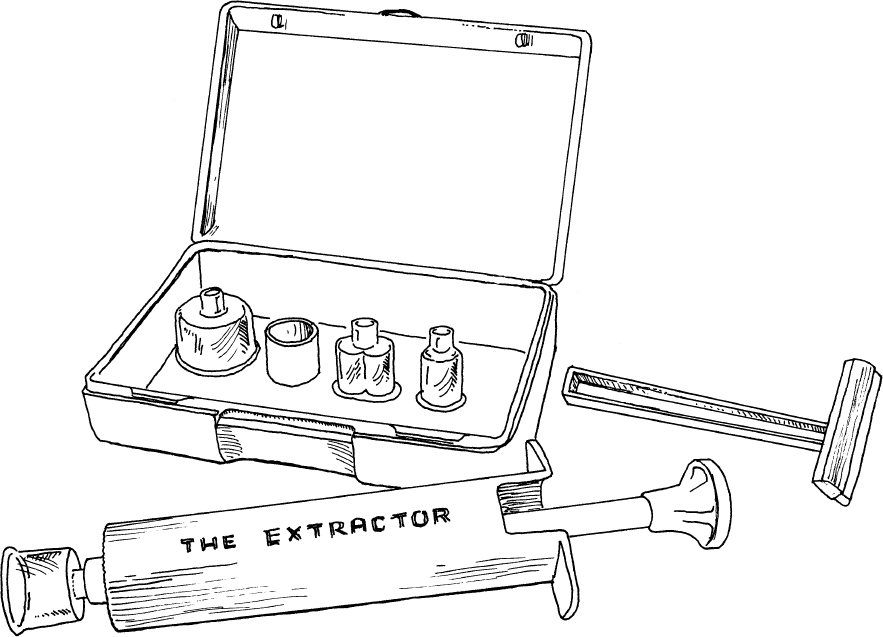

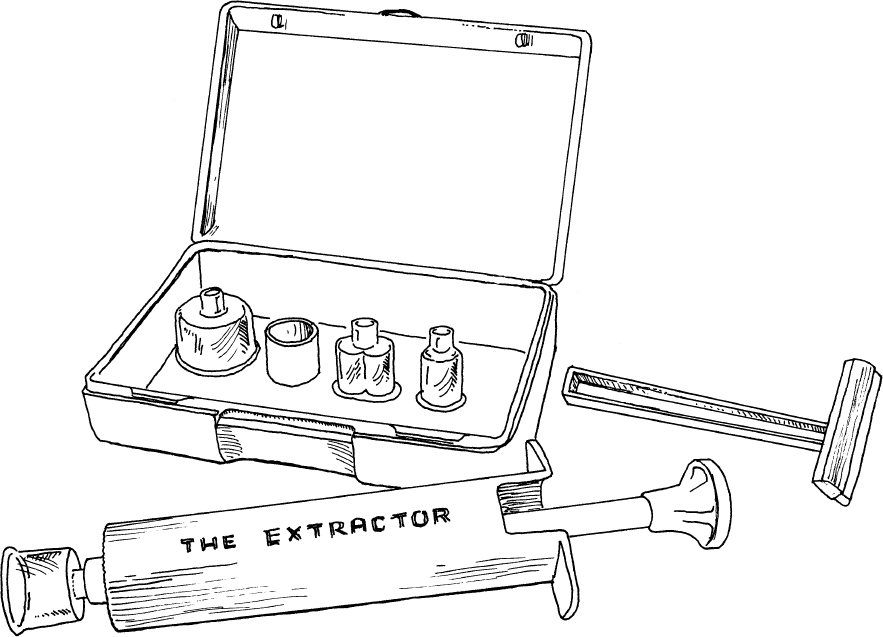

If you flinched at my (footnoted) mixmaster routine, you’ll attain full shudder at this: in some heavily used areas the fecal blizzard has gotten so bad that you are now required to collect and pack out your own. A “poop tube” developed by Mark Butler of the National Park Service consists of 4-inch PVC pipe with a cap on one end and a threaded plug at the other (look in the plumbing section of your local hardware store), retained by a duct-taped piece of webbing. You poop in a paper bag and then load it into the tube (like those Civil War cannoneers in the movies). This is not as bad as it sounds, and the Germans are way ahead of us Yanks in this department. I tested one of VauDe’s Wilderness Waste Systems, a 26-by-11-inch drybag with a roll closure at either end, in a 10-liter model (8 oz., $23). There’s also a 15-liter size (11 oz., $30)—designed not only for terrestrial waste scenarios but also for kayakers who can’t cram a river potty in. One end (IN) has a white plastic tab, the other (OUT) a black one. The instructions urge you to deploy a paper sack, dump in some sand to absorb moisture, excrete, drop in the tissues, and then file it. Unless you have pinpoint aim, the best bags are wide and short (get produce bags and trim off the tops—about 2 per oz.). Producers of polished pellets can, I suppose, deposit them on the ground and then scoop them into the sack. Since sand is both heavy and not very absorbent—and I was camping on snow—I carried sawdust in a zip-top (8 oz. lasts five days or so). Kitty litter also serves. Of course, any dry organic litter does the trick.

Most people hang the thing outside the pack using the plastic Ds on the white end. The one I used didn’t seep (the horror, the horror), but if the sun is hot, the bag may inflate somewhat with methane—also known as natural gas—and you’d be wise to vent it promptly, away from fire or flame. (To suffer the explosive combustion of your toilet bag would indeed be a wretched fate—a piece of reflective space blanket or a box-wine bladder with the ends cut off will keep things cooler.) Back at the trailhead, you get a jug of water, find the nearest appropriate facility, unroll the black end—carefully, carefully—and dis-bag the contents. Then undo the white end and sluice water through to rinse and drain, resealing for transport. An eventual scrub and sanitizing is recommended.

Has it come to this?

Jawohl!

REPLENISHING SUPPLIES

COLIN: On extended trips you always face the problem of how to replenish your supplies. Generally speaking, you can’t carry food for more than a week, or maybe two (this page). Other items also need replacement: stove fuel, toilet paper, other toilet articles, perhaps powder and rubbing alcohol for your feet. You’ll probably need additional film too, and new maps and replacement equipment and even special gear for certain sections of the trip.

On my six-month California walk I was able to plan my route so that I called in every week or 10 days at remote country post offices. Before the trip I had mailed ahead to each of these post offices not only a batch of maps for the stretch of country ahead but also items of special gear, such as warm clothing for the first high mountain beyond the desert. I wrote each postmaster explaining what I was doing and asking him to hold all packages for me until at least a reasonable time after my estimated date of arrival. At each post office I mailed to the old Ski Hut, back in Berkeley, a list of the food and equipment I wanted to pick up two weeks later; and a list of film and personal requirements went to a reliable friend. So at each post-office call-in I found waiting for me everything I needed for the next leg of the journey.

These calls at outposts of civilization provided a change of diet too: there was always a store near the post office, and usually a café and a motel. I often stayed a day or two in the motel to write and mail a series of newspaper articles (and also to soak in several hot showers and cold beers). Exposed film went out in the mails, and completed notes, and sometimes equipment I no longer needed. All in all, the system worked very well. It could be adapted, with modifications to suit the needs of the moment, for many kinds of walking trips. (I used it successfully on my six-month, 1700-mile raft trip in 1989–1990. See River: One Man’s Journey Down the Colorado, Source to Sea.)

In wild areas you have to replenish by other means. One way is to make

On the California walk I put out several water caches at critical points, and at one or two of them I also left a few cans of food. Later I realized that I should have left at least a day’s nondehydrated food, for a treat—and possibly some dehydrated food for the way ahead so that I could have cut down my load.

I was able to put those caches out by car, on little-used dirt roads, but on most wilderness trips you have to pack the stuff in ahead of time. On the two-month Grand Canyon trip I put out two caches of water, food, and other supplies. From the purely logistic standpoint I should have carried these caches far down into the Canyon so that on the trip itself I wouldn’t have to detour. But there is, thank God, more to walking than logistics. I’d been dreaming about the Canyon for a year, and one of the prime concerns in all my planning was to shield the dream from familiarity—that sly and deadly anesthetic. As I wrote in The Man Who Walked Through Time, “I knew that if I packed stores down into the Canyon I would be ‘trespassing’ in what I wanted to be unknown country; but I also knew that if I planted the caches outside the Rim I would in picking them up break both the real and symbolic continuity of my journey. In the end I solved the dilemma by siting each cache a few feet below the Rim.”

Such delicate precautions should, I think, always be borne in mind when one of the aims of a backpacking trip, recognized or submerged, is to explore and immerse yourself in unknown country. You must avoid any kind of preview. Before my Grand Canyon trip several people said, “Why not fly over beforehand, low? That’s the way to choose a safe route.” But I resisted the temptation—and in the end was profoundly thankful I’d done so.

The best way to make, mark, and protect a cache will depend on local conditions. Rain and animals pose the most obvious threats. But extreme heat has to be avoided if there’s film in the cache, and extreme cold if there is water. (For the protection and refinding of water caches, and the best containers, see this page; for precautions when caching dehydrated food in damp climates, this page.)

A cave or overhanging rockledge is probably the best protection against rain. Burying is the simplest and surest protection, especially in sandy desert, against temperature extremes and also against animals. For animals that can read, leave a note. On the California walk I put one with each cache: “If you find this cache, please leave it. I am passing through on foot in April or May, and am depending on it.” Similar notes went on the Grand Canyon caches. But I feel fairly sure that none was ever read.

At each Grand Canyon cache all food and supplies went into a metal 5-gallon can. These cans are ideal for the job. Provided the lid is pressed firmly home, the cans are watertight, something close to airtight, and probably proof against all animals except bears and humans. I find that by packing the cans very carefully I can just squeeze in a full week’s supply of everything. They’re useful, too, for packing water ahead (this page). They’re also excellent for airdrops—and having them interchangeably available for caches or airdrops may help keep your plans conveniently fluid until the last possible moment. But metal cans are no longer easy to find. A good substitute for food caches: a 5-gallon plastic bucket with clip-on plastic lid of the kind now used for some foodstuffs and such construction materials as paint, adhesive, and tar (about 1.5 lbs., and anything from free to $8 for unused ones).*5

Airdrops

Prearranged parachute airdrops are a highly efficient means of replenishment. But they’re noisy. And I’m glad to know that in today’s heavily used wilderness areas they’ve been banned as a normal supply method—as should all administrative, nonemergency overflights. After all, an object of going into such places—perhaps the object—is “to get away from it all”; and surely no one in his senses would want to inject “it” routinely in the form of low-flying aircraft. I’ve found, oddly enough, that the disturbance you suffer personally by having an airdrop is very small indeed; but once low-altitude flights—for any purpose at all—became anything more than very exceptional incursions they would disturb for everyone the solitude and sense of freedom from the man-world that I judge to be the essence of wilderness travel. As with sanitation, it’s a matter of density.

But there are still places—especially in Alaska, Africa, and South America—in which an occasional airdrop remains a reasonable supply method as well as the only practical one. So I retain almost intact this section from earlier editions.

Although airdrops are efficient, they aren’t perfect. On the ground, a practical disadvantage is that they tie you down to being at a certain place at a certain time. They’re more dependable than most people imagine, but uncertainties do exist—above all, the uncertainty of weather—and I would prefer not to rely on an airdrop if there were any considerable danger that the plane might be delayed more than a day or two by storms or fog.

Airdrops have one important advantage over other means of supply: they act as a safety check. Once you’ve signaled “all’s well” to the plane, everyone concerned soon knows you are safe up to that point. And if the pilot falls to locate you or sees a prearranged “in trouble—need help” signal, then rescue operations can get under immediate and well-directed way.

Airdrops are not cheap—but neither are they ruinous. Most small rural charter outfits now seem to charge around $150 to $300 for each hour of actual flying. If the base airport is within, say, 50 miles of the drop site you ought to get by on about an hour’s flying time—provided the pilot has no trouble locating you. You may have to add the cost of the parachute—but see this page.

Establishing contact is the crux of an airdrop operation.

First, make sure you’ve got hold of a good pilot. Unless there was no alternative I’d hesitate to depend on a man who had never done a drop before. Above all, satisfy yourself that you’ve got a careful and reliable man. Make local inquiries. And try to assess his qualities when you talk to him. Distrust a slapdash type whose refrain is “Just say where and when, and leave the rest to me.” I admit it’s a problem to know what to do if you decide, after discussing the minutest details with a pilot, that you just don’t trust him. It’s not easy to extricate yourself without gashing the poor fellow’s feelings. The solution is probably to approach him first on a conditional basis: “Look, I find that I may need an airdrop at—.” But perhaps you can dream up a better gambit.

Success in making contact depends only in part on the pilot. The recipient has a lot to do with it too. So make sure you know what the hell you’re doing.

The first time I arranged an airdrop I was very conscious that I had no idea at all what the hell. The occasion was the long Grand Canyon trip. I wanted three airdrops. The pilot and I, talking over details beforehand, decided that under expected conditions the surest ground-to-air signal was mirror-flashing. I would carry a little circular mirror, about 2 inches in diameter—the kind you could then pick up for 15 cents in any variety store. The pilot, who had been an Air Force survival instructor, assured me that such a mirror was just as good as specially made mirrors with cross-slits—and, at barely an ounce, was also appreciably lighter. The trick was to practice beforehand. I soon picked up the idea. You hold the mirror as close to one eye as you can and shut the other eye. Then you extend the free hand and aim the tip of the thumb at a point (representing the plane) that’s not more than about 100 yards away. You move the mirror until the sun’s reflection, appearing as a bright, irregular patch of light, hits the top of your thumb. Then you tilt the mirror up a bit until only the lowest part of the patch of light remains on your thumb. The rest of it should then show up exactly on the object that represents the plane. If it doesn’t, keep practicing with fractional adjustments of mirror and thumb until you know precisely where to hold both so as to hit your target. You’re now ready for the real thing. Ready, that is, to flash sunlight into the pilot’s eyes.

“It’s the surest way I know,” said my Grand Canyon pilot. “On survival exercises I’ve located guys that had nothing to flash with except penknife blades or even just sunglasses. When that flash hits my eye just once, the job’s done. That’s all I need to know: where to look. But without something to start me off, the expanse of ground I can see, especially in broken country like the Canyon, is just too damned big.”

After a few minutes’ practice I had complete confidence in the mirror routine; but we also arranged that I should spread out my bright orange sleeping bag as a marker, and would have a fire and some water ready so that when the plane had located me and came over low on a trial run I could send up a plume of smoke to indicate wind direction.

Because I wasn’t sure how far I could travel across very rough country in a week, and because I didn’t want to be held back if I found I could move fast, we arranged primary and alternate sites for the first drop. We set zero hour at 10:00 a.m. on the eighth morning after I left an Indian village that would be my last contact with civilization. The chances were good that at ten o’clock no clouds would obscure the sun and that the day’s desert winds would not yet have sprung up.

I made the alternate, farther-along site in time and, with complete confidence in the mirror-signaling technique, decided for various reasons to take the drop about 2 miles from the prearranged place, out on a flat red rock-terrace. The plane arrived dead on schedule. But it failed to see my frantic flashings and, after an hour’s fruitless search around the prime site and back along the way I’d come, was heading for home and passing not too far from me when I poured water on the waiting fire and sent a column of smoke spiraling up into the clear air. Almost at once the plane banked toward me, and within minutes my supplies were sailing safely down, suspended from a big orange parachute.

Later, a park ranger in the plane told me that he’d seen the smoke the moment it rose in the air. “But we didn’t see the flashing until we were almost on top of you. At a guess, I’d say you didn’t shake the mirror enough. You’ve got to do that to set up a good flashing. Oh, and your orange sleeping bag didn’t show up at all against the red rock. We could hardly see it, even on the drop run.”

So my first airdrop taught me a valuable lesson: unless it’s absolutely unavoidable, don’t change your prearranged drop site, even by a short distance. For the two later drops on that trip we’d picked only one site, and each time I was in exactly the right place. I also had the white 8-by-9-foot plastic sheet (this page) in my pack, and I spread it out beside the sleeping bag. Each time, the pilot saw the white patch as soon as he came within range, and although I had begun to flash with the mirror, the plane rocked its wings in recognition and I therefore stopped flashing before there was time to assess the mirror’s worth. Both these later drops went off without a hitch.*6

Three years later, on my 17-day hike-and-swim trip through Lower Grand Canyon, I had another airdrop. Because the route was untried I couldn’t guarantee to be at the clearly defined riverside ledge that was the prime drop site, and on the scheduled morning I was still 3 miles upriver, on the most obvious and open ledge I could find—which was neither very obvious nor very open. Our plan was that if the pilot didn’t see me at the prime drop site he’d fly upriver to my starting point and then return, still down in the Inner Gorge, between rockwalls more than 2000 feet high and, at their foot, barely 200 yards apart. It worked. The pilot missed me on the upriver run—because the early-morning sun was in his eyes and because I didn’t have time to generate much smoke from the fire I had ready. But on the return run he saw the now healthy smoke column from far upriver, and when he turned some way below me and came back for the drop, into the blinding sun, he had no difficulty knowing where I was because of the cloud of orange smoke from a day flare that I’d carried for that specific purpose and had ignited as soon as I heard him returning downriver. The orange cloud persisted well and showed up clearly, he told me later. The parachute he used, by the way, was one he’d made by stitching together two plastic windsocks. It worked fine.

Several people have written asking what I did in the Canyon with the parachutes and other garbage. I packed the chutes and everything else into the metal 5-gallon cans that the supplies had been packed in (this page); and I tucked the cans away out of sight. (Years later, separate people found two of them—and actually returned one to me.)

Useful as they may be, helicopters are—at least in wilderness—disgusting bloody machines. And I feel sure that having one land and offload supplies—and also bring you into contact with “outsiders”—would be a far more disruptive event than an airdrop. What’s more, the ’copters’ fiendish clatter and the way they can mosey into every corner make them even less desirable as wilderness suppliers than conventional planes. Still, I suppose there are times and places…

Average charter rates for a small helicopter operating no higher than about 5000 feet start at around $250 an hour. Supercharged ’copters for mountain work may cost $500 an hour, and the newer light-turbine versions as much as $800. (Comparable rates for small conventional plane: around $150 and up.)

It’s worth knowing—not so much for supply purposes but because most wilderness rescue work is now carried out by helicopters—that they can’t put down just anywhere. A slope of more than about 10 degrees isn’t a feasible landing place for even a small machine. In good conditions, though, on a clear surface, an expert pilot may be able to hover with one skid on a steeper slope long enough to pick up a casualty. But even for this method (known as a “toe-in”) the slope can’t be more than about 25 degrees.

In lake-rich places—notably Alaska—floatplanes are a common means of shipping backpackers into wild and largely roadless country. My only use of one worked well. See Secret Worlds, Chapter 5.

A couple of times, I’ve also chartered small wheeled planes to get quickly into remote places. Once, near Lower Grand Canyon, we achieved an interesting touchdown on a narrow dirt road.

Charter rates for small rural-based planes—for ferrying, as for parachute drops—now run around $150 to $300 for each flying hour.

CHIP: A support backpacker is, in the largest sense, a pack animal. And having backpacked loads in to support friends on wilderness routes where caching was banned, I’m an honorary beast of burden. One method is portering, in which you accompany the main party in and then pull out, leaving your load. But what I’ve done more often is to rendezvous with someone a week or more along their route. As with airdrops, the key is having your meeting place and time absolutely riveted—and having the patience to stay put. In one sad case I watched from a rocky summit as an outdoor leadership class and their resupply train of packhorses circled my vantage point repeatedly—following, as it turned out, one another’s tracks.

COLIN: Indoorsmen often ask why I never use a pack animal such as a burro on any of my long walks. Blame for the thought probably lies with Robert Louis Stevenson and his Travels with a Donkey—or maybe with TV prospectors who amble across parched western deserts escorted by amiable burros.

Frankly, I’ve never even been tempted. For one thing, I can go places a burro can’t. And I blench at the prospect of looking after a burro’s food and water supply. Also, although I know nothing at first hand about managing the beasts, I mistrust their dispositions. Come to think of it, I don’t seem to be alone in my distrust. Precious few people use burros these days. It’s perhaps significant that on one of the only two occasions I’ve come across this man-beast combination, the man was on one side of a small creek pulling furiously and vainly at the halter of the burro, and the burro was planted on the far bank with heels dug resolutely in.

CHIP: Climbers and some backpackers hire horse-and-mule outfitters to haul loads in, a practice known as spot-packing. (A drop-camp by contrast means that the outfitter hauls in tents, etc., and sets them up, leaving you there for a specified time.) Rates in the U.S. for a one-day spot-pack are generally a flat fee, $100 to $200, plus a charge ($50–$75) for each pack animal. If the pack animals must be trucked to the trailhead, the cost increases. If the packer stays overnight the price goes up again, steeply. And if you expect to be packed out, it costs the same again.

A recent alternative is to hire llamas or pack goats. Both can handle rougher terrain than can horses while doing less damage to trails. They might come with a handler or alone. The backpacking shop in Pinedale, Wyoming, had a rental pair of llamas and a trailer—solidly booked from June through September. For two field seasons of wilderness monitoring, I leased my own pair of llamas and found them stalwart—the larger of the two could carry 125 lbs.—and easy to handle (for more llama tales, see Sky’s Witness: A Year in the Wind River Range). Having the snooty aloofness of their camel cousins, llamas are tractable rather than friendly. In fact, too much fussing and petting is the surest way to make them spit or kick, which they mostly do only to one another. Pack goats are incredibly agile and also friendlier, though they travel somewhat low to the ground. For more goat-lore, consult The Pack Goat by John Mionczynski (Pruett, 1992, $16) and, for goat-related philosophical insights, Goatwalking by Jim Corbett (Viking, 1991, $20).

In far-flung lands you might find reindeer, camels, or yaks for hire. Since packers can be a rough lot and large animals more so, shoving their loads into rocks and occasionally rolling over on them, things do get broken. To forestall damage, wrap your pack in a cheap Ensolite sleeping pad and/or enclose it in a duffel. Always carry cameras and such yourself.

DANGERS, REAL AND IMAGINED

COLIN: For many wilderness walkers, no single source of fear quite compares with that stirred up by

Rattlesnakes.*7

Every year an almost morbid terror of the creatures ruins or at least tarnishes countless otherwise delightful hikes all over the United States and Canada. This terror is based largely on folklore and myth.

Now, rattlesnakes can be dangerous, but they’re not what so many people fancy them to be: vicious and cunning brutes with a deep-seated hatred of man. In solid fact, rattlers are timid and retiring. They are highly developed reptiles but they simply don’t have the brain capacity for cunning in our human sense. And although they react to man as they would to any big and threatening creature, they could hardly have built up a deep-seated hatred: the first human that one of them sees is usually the last. Finally, the risk of being bitten by a rattler is slight, and the danger that a bite will prove fatal to a healthy adult is small.*8

In other words, ignorance has as usual bred deep and unreasoning fear—a fear that may even cause more harm than snakebite. Some years ago, near San Diego, California, a hunter who was spiked by barbed wire thought he’d been struck by a rattler—and very nearly died of shock.

The surest antidote to fear is knowledge. When I began my California walk I knew nothing about rattlesnakes, and the first one I met scared me purple. Killing it seemed a human duty. But by the end of the summer I no longer felt this unreasoning fear, and as a result I no longer killed rattlers—unless they lived close to places frequented by people.

Later I grew interested enough to write a magazine article about rattlesnakes, and in researching it I read the entire 1500-odd pages of the last-word bible on the subject. As I read, the fear sank even further away. Gradually I came to accept rattlesnakes as fellow creatures with a niche in the web of life.

The book I read was Rattlesnakes: Their Habits, Life Histories and Influence on Mankind by Laurence M. Klauber (University of California Press, 1997; 1580 pages; $108. Abridged edition, 1982, 350 pages, $50; paperback, 1989, $17). Dr. Klauber was the world’s leading authority on rattlesnakes, and in the book he sets out in detail all the known biological facts. But he does more. He examines and exposes the dense cloud of fancy and folklore that swirls around his subject. I heartily recommend this fascinating book to anyone who ever finds his peace of mind disturbed by a blind fear of rattlesnakes—and also to anyone interested in widening the fields in which he can observe and understand when he goes walking. You should find the book in any university library, and in any medium-size or large public library.

Among the many folklore fables Dr. Klauber punctures is the classic “boot story.” I first heard this one down in the Colorado Desert of Southern California—and believed it. “There was this rancher,” the old-timer told me, “who lived not far from here. One day he wore some kneeboots belonging to his father, who had died 10 years before. Next day the rancher’s leg began to swell. It grew rapidly worse. Eventually he went to a doctor—just in time to avoid amputation from rattlesnake poisoning. Then he remembered that his father had been struck when wearing the same boots a year before he died. One of the snake’s fangs had broken off and lodged in an eyehole. Eleven years later it scratched the son.”

Essentially the same story was read before the Royal Society of London by a New World traveler on January 7, 1714. That version told how the boot killed three successive husbands of a Virginia woman. Today the incident may take place anywhere, coast to coast, and the boot is sometimes modernized into a struck and punctured tire that proves fatal to successive garagemen who repair it. Actually, the amount of dried venom on the point of a fang is negligible. And venom exposed to air quickly loses its potency.

Then there’s the legend of the “avenging mate”: kill one rattler, and its mate will vengefully seek you out. Pliny, the Roman naturalist who died in A.D. 79, told this story of European snakes, and it’s still going strong over here. In 1954, after a rattlesnake had been killed in a downtown Los Angeles apartment, the occupant refused to go back because a search had failed to unearth the inevitably waiting mate.

The legend probably arose because it seems as though a male may occasionally court a freshly killed female. Some years ago a geographer friend of mine and a zoologist companion, looking for specimens for research, killed a rattler high in California’s Sierra Nevada. The zoologist carried the snake 200 yards to a log and began skinning it. My friend sat facing him. Suddenly he saw another rattler crawling toward them. “It was barely four yards away,” he told me later, “and heading directly for the dead snake; but it was taking its time and seemed quite unaware of our presence. We killed it before it even rattled. It was a male. The first was a female.” An untrained observer might well have seen this incident as proof positive that the second snake was bent on revenge.

Toward the end of my 17-day foot trip through Lower Grand Canyon I saw with my own eyes just how another myth could have arisen. I was running very short of food, and after meeting four rattlers within four days I reluctantly decided that if I met another I’d kill and cook it. I duly met one. It was maybe 3 feet long—about as big as they grow in that country. I promptly hit it with my staff a little forward of the tail, breaking its back and immobilizing it; but before I could put it out of its pain by crushing its head, it began striking wildly about in all directions. Soon—and apparently by pure accident—it struck itself halfway down the body. It was a perfect demonstration of how the myth arose that wounded rattlers will strike themselves to commit suicide. (Quite apart from the question of whether snakes can comprehend the idea of a future death, rattlesnakes are little affected by rattlesnake venom.)

After I’d killed that snake I cut off the head, wrapped the body in a plastic bag, and put it in my pack; but I couldn’t for the life of me remember what Dr. Klauber had said about eating rattlers that had struck themselves. As I walked on, thinking of the venom that was probably still circulating through the snake’s blood system, I grew less and less hungry. After half an hour, feeling decidedly guilty about the unnecessary killing, I discarded the corpse. Later I found that although people are often warned against eating a rattler that has bitten itself there is in fact no danger if the meat is cooked: the poisonous quality of snake venom is destroyed by heat. It’s as well to cut out the bitten part, though, just as you cut away damaged meat in an animal that’s been shot. Back in the 1870s one experimenter got a big rattler to bite itself three or four times. It lived 19 hours and seemed unhurt. The man then cooked and ate it without ill effect.

According to Dr. Klauber, rattler meat has been compared with chicken, veal, frog, tortoise, quail, fish, canned tuna, and rabbit. It is, as he points out, useful as an emergency ration because it’s easily hunted down and killed, even by people weakened by starvation. But there’s only 1 lb. of meat on a 4-foot rattler, 2.5 lbs. on a 5-footer, and 4.5 on a 6-footer. The one small and skinny rattler I’ve eaten tasted of nothing in particular. And stringy.

Even straightforward information about rattlesnakes often gets hopelessly garbled in the popular imagination. For example, the only facts about rattlers that many people know for sure are that they grow an extra rattle every year, revel in blistering heat, and are fast and unfailingly deadly. Not one of these “facts” is true. Number of rattles is almost no indication of age. A rattler soon dies if the temperature around it rises much over 100°F. It crawls so slowly that the only dangerous rattler is the one you don’t see. Even the strike isn’t nearly as fast as was once thought. Tests prove it to be rather slower than a trained man’s punching fists. If you move first—as fast as you can, and clean out of range—you may get away with it, though avoiding the strike, even if you’re waiting for it, borders on the impossible.

Accurate knowledge will not only help dispel many unreasoning fears (it’s nearly always the unknown that we fear the most) but can materially reduce the chances that you’ll be bitten.

Take the matter of heat and cold, for example. Rattlesnakes, like all reptiles, lack an efficient mechanism such as we have for keeping body temperature constant, so they’re wholly dependent on the temperature around them. In cold climates they can hibernate indefinitely at a few degrees above freezing, and have fully recovered after four hours in a deep freeze at 4°F. Yet at 45° they can hardly move, and they rarely choose to prowl in temperatures below 65°. Their “best” range is 80 to 90°. At 100° they’re in danger, and at 110° they die of heat stroke. But these, remember, are their temperatures—that is, the temperatures their bodies attain through contact with the ground over which they’re moving and with the air around them. These temperatures may differ markedly from official weather readings taken in the shade, 5 feet above ground level. When such a reading is 60°, for example, a thermometer down on sunlit sand may record 100°, and in the lowest inch of air about 80°. (See this page.) In other words, a rattler in the right place may feel snugly comfortable in an “official” temperature of 60°. On the other hand, in a desert temperature of 80° in the shade, the sunlit sand might be over 130° and the lowest inch of air around 110°, and any rattler staying for long in such a place would die.

Once you know a few such facts you find after a little practice that your mind almost automatically tells you when to be especially watchful, and even where to avoid placing your feet. In cool early-season weather, for example, when rattlers like to bask, you’ll tend to keep a sharp lookout, if the sun is shining but a cold wind is blowing, in sunlit places sheltered from the wind. And in hot desert weather you’ll know that there’s absolutely no danger out on open sand where there’s no shade. On the other hand, the prime feeding time for rattlers in warm weather is two hours before and after sunset, when the small mammals that are their main prey tend to be on the move; so if you figure that the ground temperature during that time is liable to be around 80° to 90° you keep your eyes skinned. I don’t mean that you walk in fear and trembling. But you watch your step. Given the choice, for example, you tend to bisect the space between bushes, and so reduce the chances of surprising a rattler resting unseen beneath overhanging vegetation. Once you’re used to it, you do this kind of thing as a natural safe operating procedure, no more directly connected with fear than is the habit of checking the street for traffic before you step off a sidewalk.*9

You’ll also be able to operate more safely once you understand how rattlesnakes receive their impressions of the world around them. Their sight is poor, and they’re totally deaf. But they’re well equipped with other senses. Two small facial pits contain nerves so sensitive to heat that a rattler can strike accurately at warm-blooded prey in complete darkness. (Many species hunt mainly at night.) They’re highly sensitive to vibration too, and have rattled at men passing out of sight 150 feet away. (Moral: in bad rattler country, at bad times, tread heavily.) Two nostrils just above a rattler’s mouth furnish a sense of smell very like ours. And that’s not all. A sure sign that a snake has been alerted is a flickering of its forked tongue: it is “smelling” the outside world. The tongue’s moist surface picks up tiny particles floating in the air and at each flicker transfers them to two small cavities in the roof of the mouth. These cavities, called “Jacobson’s organs,” interpret the particles to the brain in terms of smell, much as do the moist membranes inside our noses.

In Biblical times, people wrongly associated snakes’ tongues with their poison. Nothing has changed. Stand at the rattlesnake cage in any zoo and the chances are you’ll soon hear somebody say, “There, did you see its stinger?” or even, “Look at it stick out its fangs!” It is true, though, that an alarmed snake will sometimes use its tongue to intimidate enemies. When it does, the forked tips quiver pugnaciously out at their limit, arching first up, then down. It’s a chillingly effective display. But primarily, of course, a snake reacts to enemies with that unique rattle. Harmless in itself, it warns and intimidates, like the growl of a dog.

The rattle is a chain of hollow, interlocking segments made of the same hard and transparent keratin as human nails. The myth that each segment represents a year of the snake’s age first appeared in print as early as 1615. Actually, a new segment is left each time the snake sheds its skin. Young rattlers shed frequently, and adults an average of one to three times each year. In any case, the fragile rattles rarely remain complete for very long.

In action the rattles shake so fast that they blur like the wings of a hummingbird. Small snakes merely buzz like a fly but big specimens sound off with a strident hiss that rises to a spine-chilling crescendo. Someone once said that it was “like a pressure cooker with the safety valve open.” Once you’ve heard the sound you’ll never forget it.

The biggest rattlers are eastern diamondbacks: outsize specimens may weigh 30 lbs. and measure almost 8 feet. But most of the 30 different species grow to no more than 3 or 4 feet.

People often believe that rattlers will strike only when coiled, and never upward. It’s true that they can strike most effectively from the alert, raised-spiral position; but they’re capable of striking from any position and in any direction.

Rattlers are astonishingly tenacious of life. One old saying warns, “They’re dangerous even after they’re dead”—and it’s true. Lab tests have shown that severed heads can bite a stick and discharge venom for up to 43 minutes. The tests even produced some support for the old notion that “rattlers never die till sundown.” Decapitated bodies squirmed for as long as 7½ hours, moved when pinched for even longer. And the hearts almost always went on beating for a day, often for two days. One was still pulsating after 59 hours.

A rattlesnake’s enemies include other snakes (especially king snakes and racers), birds, mammals, and even fish. In Grand Canyon I found a 3-foot rattler apparently trampled to death by wild burros. Torpid captive rattlers have been killed and partly eaten by mice put in their cages for food! Not long ago a California fisherman caught a big rainbow trout with a 9-inch rattler in its stomach. But only one species of animal makes appreciable inroads on the rattlesnake population. That species is man—to whom the warning rattle is an invitation to attack. If humans had existed in large numbers when rattlesnakes began to evolve, perhaps 6 million years ago, it’s unlikely the newfangled rattlebearers would have succeeded and flourished.