© Reprinted from Physiology of Man in the Desert by E. F. Adolph and Associates (Interscience Publishers, New York, 1947).

COLIN: You can if necessary do without food for days or even weeks and still live, but if you go very long without water you assuredly die. In really hot deserts the limit of survival without water may be barely 48 hours. And well before that your brain is likely to become so addled that there’s a serious risk of committing some irrational act that will kill you.

Too few people recognize the insidious nature of such thirst-induced irrationality. It can swamp you, suddenly and irretrievably, without your being in the least aware of it.*11

© Reprinted from Physiology of Man in the Desert by E. F. Adolph and Associates (Interscience Publishers, New York, 1947).

I described one such case in The Man Who Walked Through Time. In July 1959 a 32-year-old priest and two teenage boys tried to follow an old trail down one side of Grand Canyon to the Colorado. They carried little or no water. More than halfway down, hot and tired and already very thirsty, the priest made the barely rational decision to climb back to the rim. Before long the trio lost their way. Next morning, desperately dehydrated, they tried to follow a wash back to the river. Soon they came to a sheer 80-foot drop-off. The priest, apparently irrational by now, had all three take off their shoes and throw them to the bottom. Then he tried to climb down. A few feet, and he fell to his death. The boys soon found a passable route, but one of them died on the way down to the river. The other was rescued by helicopter a week later, 8 miles downstream.

I know only the bare outline of this story. But some years ago I interviewed many times, and eventually wrote a magazine article about, two boys who were trapped in the Mojave Desert. This is not a walking story, but it is the only case in which I know full details of the kind of irrationality that any dehydrated hiker could all too easily develop. The boys were Gary Beeman, 18, and Jim Twomey, 16. Their car bogged down near midnight in soft sand, 200 feet off a remote gravel side road. It was June. Daytime shade temperatures probably approached 120°F. Humidity was virtually zero. The only liquid foods in the car were two cans of soup and one of pineapple juice, plus 2 pints of water. By the end of the first day—during most of which the boys rested in the shade of some nearby rocks—they had finished all the liquid. That night, working feebly, they moved the car barely 15 feet back toward the firm gravel.

The second day, back among the rocks, both boys suffered delirium. At sunset Jim Twomey staggered toward the car. Suddenly he sank to his knees, pitched forward, and lay still. The older boy, Gary, saw him fall. In midafternoon he had staggered irrationally out from the shade of the rocks into blazing sunlight in order to “try to find some water,” and had finally dug himself into the cool sand. Now he felt less lightheaded. He went over to his friend and bent over him. Jim’s face was deathly pale. His mouth hung open. Dried mucus flecked his scaly white lips. Gary hurried to the car, searched feverishly through the inferno inside it, and at last found a bottle of after-shave lotion. He wrenched off the top and put the bottle to his lips. The shock of what tasted like hot rubbing alcohol brought him up short. He had a brief, horrible comprehension of his unhinged state of mind. Afterward all he could think was, “We need a drink. We both need a drink.”

Desperately he ran his eyes over the car. For a moment he considered letting air out of the tires and somehow capturing its coolness. Then he was thinking, “My God, the radiator!” He had always known that in the desert your radiator water could save you; yet for two days he had ignored it! Again he had that terrible momentary comprehension of his state of mind. Then he grabbed a saucepan, squirmed under the front bumper, and unscrewed the drainage tap. A stream of rust-brown water poured down over the greasy, dust-encrusted sway bar and splashed into the saucepan. “That water,” he told me later, “was the most wonderful sight I had ever seen.”

After he had drunk a little, Gary found himself thinking more clearly. He went back and poured some water into Jim’s open mouth. Quite quickly Jim revived. All at once Gary saw what should have been obvious all along: a way to run the car clear, using some old railroad ties they had found much earlier. He spent almost the whole night aligning the ties—five or six hours for a job that would normally have taken him 20 minutes. At sunrise he helped his half-conscious friend into the car and made what he knew—because they had now finished the radiator water—would have to be their last attempt, however it ended. Moments later, with wheels spinning madly and the bucking car threatening to stall at any second, they shot back onto the gravel road. Four hours later, after many sweltering halts for the now dry motor to cool, they hit a highway.

Since that day Gary has never driven into the desert without stocking up his car with at least 15 gallons of what he now calls “the most precious liquid in the world.”*12

Important: Note that I tell this story only to illustrate the quick onset and dangerous nature of thirst-induced irrationality. Today almost all cars come with coolant solutions containing ethylene glycol in their radiators, and ethylene glycol, even heavily diluted, is deadly poisonous to man. And the first symptoms resemble drunkenness or delirium, which in the desert could easily be misconstrued.

You can very easily, in your minute-by-minute behavior, take sensible steps to conserve your body’s precious water. People brought up in hot climates often train themselves, early, to reduce losses on torrid days by keeping their mouths closed. Talking is reduced to the minimum. The moist membranes of the mouth certainly lose a lot of water if exposed to free air, and such precautions are well worth taking.

Theory and folklore suggest you wear clothes that cover almost all your skin and so reduce perspiration loss. But other factors come into it, and in practice I tend to do exactly the opposite (this page).

For recycling of body fluids in a solar still, see this page.

For replacement of essential electrolytes lost through sweating, see this page.

When you’re backpacking you can’t play it as safe as Gary Beeman learned to do and carry 15 gallons of water (1 U.S. gallon weighs 8⅓ pounds); but in any kind of dry country you’ll have to carry more than you’d like to.

In the mountains you may not need to pack along any at all—though even in the mountains there are often long, hot stretches without a creek or lake or snowbank, and unless I’m sure of a regular supply I tend to carry at least a cupful in a canteen. In deserts, water becomes the most precious item in your pack—and often the heaviest. In the drier parts of Grand Canyon I left each widely spaced water source carrying at least 2 gallons. Together with the four canteens, that meant a 19¾-pound water load. At the start of several long dry stretches I carried a third gallon in a disposable plastic liquid-bleach bottle from a food cache. On such occasions I’d walk for a couple of hours in the cool of evening, drink copiously at dinner and breakfast, then leave in the morning, fresh and fully hydrated, on a long and waterless stretch that was now two critical hours shorter than it had been.

The amount of water you need under specific conditions is something you must work out for yourself. As with food, requirements vary a great deal (though see this page and its footnote).*13

For me, half a gallon is under normal conditions a comfortable ration for a dry night stop, provided I’m sure of finding more by midmorning. In temperatures around 90°F, and in near-zero desert humidity, a gallon once lasted me 36 hours, during which I walked a flat but rather soft-surfaced 30 or so miles with no appreciable discomfort, though with no washing or tooth cleaning either. But I was steely fit at the time, and well acclimated; I wouldn’t dream of attempting that stretch “cold” with so little water.

I always lean toward safety. I can recall only three occasions on which I’ve been at all uncomfortably thirsty, even in the desert; and lack of water has never even threatened to become a real danger. It pays to remember, though, that only a hair’s breadth divides safety from potential tragedy. If you’re alone, one moment of carelessness or ill luck could send you stumbling across the threshold: a twisted ankle miles from water would probably be enough; certainly a broken leg or a rattlesnake bite. I try to make some kind of allowance for such possibilities, but in the end you have to rely mostly on caution and luck. Perhaps the two are not altogether unconnected. An ancient Persian proverb has it that “Fortune is infatuated with the efficient.”

The old Spartan routine of drinking water at infrequent intervals, and rarely if ever between meals, is perhaps necessary for military formations: only that way can you satisfactorily impose group discipline. But for individuals the method is inefficient. For one thing, you tend to drink unnecessarily large quantities when at last you get the canteen to your lips. And although thirst may not become an actual physical discomfort, you often walk for hours with your mind blinkered by a kind of dehydrated scum that seals off any vivid appreciation of the world around you.

In well-watered country I take a drink, if I feel like it, at any convenient creek or lake. (At least, I used to. See the section on Giardia, below.) Up high or in winter I sometimes suck snow or ice as I walk along. In deserts I drink a few sips of water at each hourly halt, swilling it around my mouth before swallowing. I’m almost sure I use less water this way. I certainly know that the little-and-often system keeps washing the first traces of that blinkering scum away from the surface of my mind, and so rehones the edges of my appreciation. And appreciation, after all, is the reason I’m walking.

In assessing the purity of any water supply, the only safe rule is: “If in doubt, doubt.” In the years since early editions of this book appeared, things have deteriorated so badly that in most places you should now maybe doubt any source except fresh rain pockets and springs (and, as we shall see, there are certain dangers even with springs). You can blame mankind, exploding toward disaster, or find some other scapegoat, but the sad fact remains that—as suggested in an excellent article in the May 1981 issue of Audubon magazine, by Bert Newman—“the days of drinking directly from streams may be over.” It is difficult, standing beside a clear, cold, rushing mountain torrent in the Appalachians, Rockies, Cascades, or Sierra, to believe that such water is probably polluted. But the chances are, no matter how high you go, that it is. And the hazard now lurks there, too strong to ignore, almost everywhere in the U.S.—and, indeed, in the world.

The danger can stem from any one of many infectious organisms, but 9 or 10 of them (all except one transmitted by feces) account for most of the trouble. And in the U.S. the most common of these now seems to be a protozoan called Giardia lamblia. Giardia is most often passed from organism to organism in the form of a tiny oval cyst about 10 by 20 microns—though it may measure only 7 microns across. About 16,500 can fit on the head of a pin—to the exclusion of all angels in the vicinity. One stool from a moderately infected human can produce 300 million cysts—and the ingestion of as few as 10 or 20 of them can infect you. Once in the upper small intestine, the cysts hatch into active, wineskin-shaped trophozoites, then divide and multiply, and soon establish a ravenous colony.

Of the 16 million Americans who probably now have giardiasis (also known as “backpackers’ disease”), many may be only carriers who remain perfectly healthy, showing no sign of the disease—yet can excrete cysts for months or even years. It remains unclear why some infected people get giardiasis symptoms while others do not. But the unlucky ones discover that the disease is no laughing matter. After an incubation period of from 7 to 14 days you suffer “a fulmination of diarrhea, cramps, visible bloating, weight loss, nasty burps, and anorexia (loss of appetite).” Get a bad case, and you may vomit too. As soon as possible, consult a doctor. In the backcountry, even more than “outside,” the results can be serious. “Everything you eat promptly comes up or out,” says one victim. In 7 days his weight plummeted from 165 lbs. to 115. And weakness and other symptoms may persist for months. All this stems, by the way, from an organism that, although long known to occur in humans, was until 40 years ago thought to be harmless to them.

Unfortunately, humans are only the start of it. Other animals that are sufferers and carriers include several of our hangers-on—cattle, horses, and dogs—that also travel the backcountry and are even less particular in their sanitation habits than the most undisciplined human. Also susceptible: rabbits, coyotes, deer—and, probably, beavers, who routinely defecate in creeks and therefore spread the disease like wildwater (hence the alternative name, “beaver fever”). The wildlife carriers make it seem overwhelmingly likely that once an area has become infested, Giardia will be there to stay.

Reasons for the recent spread of infestation remain obscure. Most likely culprit: man, in increasing numbers, with decreasing discipline. But livestock, especially horses, could be culpable. (Few dogs and no cattle visit such recently infested areas as Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks in the Sierra Nevada.) As with other imbalances in today’s world, with its exploding human population, the root may be purely a matter of density. But, whatever the cause, the end result—and especially its probable permanence—is pretty damned sad.*14

For treating water suspected of harboring Giardia, see next section.

Even today most springs are safe—from Giardia and other contaminants. But mineral springs, especially in deserts, can be poisonous. One culprit is arsenic.

What you do if you suspect an unposted bitter-tasting spring, I really don’t know—though a lack of insect life would be good reason for doubting its safety. I would guess that if you’re in danger of dying from thirst you drink deep; and that if you’re not in danger you stand and ruminate for a few minutes, then walk on. Perhaps I should add that in out-of-the-way places I’ve come across some remarkably evil-looking springs, bubbling and steaming and reeking, and have discovered that the water was drunk regularly by some hardy local. But the only safe rule remains: “If in doubt, doubt.”

CHIP: Another watch-out, common in the arid western U.S., is selenium (in trace amounts a necessary nutrient), and surface water can contain toxic amounts. The water itself may bear no visible sign, but experienced friends tell me that selenium smells “garlicky” and that plants such as princess plume indicate high levels. A distinctly visible sign of trouble is a whitish crust at the water’s edge, indicating a high proportion of dissolved salts. If not actively poisonous such water may yet be highly laxative, with the same dangerous net dehydrating effect as giardiasis. So drink these waters only in direst need, and sample a small amount first.

In areas where mining took place, the acid drainage from tunnels or waste dumps can carry heavy metals (e.g., lead) into streams. Where there’s farming or ranching upstream, nitrates, phosphates, herbicides, and pesticides might be found. Some filters can remove dissolved chemicals—see this page.

COLIN: Don’t rely on maps, by the way, for information about springs. Even the excellent U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) topographical series often show springs that dry out each summer or have vanished altogether due to some subterranean change. Other springs may fail in extra-dry years. Rely only on recent reports from people you feel sure you can trust. If any doubts linger, carry enough water to take you not only as far as the hoped-for spring but also back to the last water source.

Sometimes, of course, snow will be your surest, or only, source of water (this page).

Water purification

CHIP: The following paragraphs might just as well be subtitled “Things You’d Rather Not Know.” Even the clearest, coldest stream can yield an unheavenly, invisible host, all poised to ruin your internal neighborhood. Meanwhile, from the makers of potions and devices there issues a flood of test results and counterclaims that must also be filtered before being swallowed. In 1996, Backpacker ran a special report by Mark Jenkins that’s still the most understandable treatment of the subject, paired with an exhaustive field test of water filters by Kristin Hostetter. A good book on the topic is Purification of Wilderness Waters by David O. Cooney. Cooney, a chemical engineer, provides detailed explanations of gazigglies and also charts the performance of chemical treatments and the most common filters circa 1998. I also consulted Medicine for the Outdoors by Paul S. Auerbach, M.D. (For a list of these and related titles, see Appendix IV.) To simplify a bit, I’ve compiled what I found as a table (see below).

Most belly vengeance involves three forms of gazigglies that spend part of their life cycle in your internal Shangri-la. Protozoa are free-living one-celled critters that form shelled oocysts (Oh, oh—cysts!) from 4 to 20 microns (a micron being one-millionth of a meter), so they’re smaller than the eye can see. Bacteria are one-tenth that size, from 0.3 micron to 2 microns, and come in spheres (cocci), rods (bacilli), and spirals (spirillia). Some occur naturally in your gut, including strains of E. coli, where they’re vital for digestion and general health. But in water they indicate contamination by other disease-causing types. Viruses are subcellular globs of nucleic acid coated with protein, from 0.02 to 0.1 micron (i.e., roughly one-tenth the size of bacteria). A whopping 97 percent of all waters harbored one of the three, Chuck Hibler, a Colorado parasitologist, told Backpacker‘s Mark Jenkins, in a study involving 10,000 samples “from streams all across America, Alaska to Arizona, and we didn’t find one without Giardia.” So why is it that some of us, me included, have imbibed largely of wilderness waters without getting sick? One reason is that low concentrations of organisms in pristine, high-altitude waters are less likely to successfully colonize your internal habitat. Another is that resistance varies a lot: the young, the old, and those with weak immune systems can be vulnerable to a single gazigglum. Another is that some of us are hosts: post-illness, we carry the little monsters around without any symptoms.

WATERBORNE DISEASES

This raises the probability issue. And the experts agree that the concentration, whether protozoans, bacteria, or viruses, is much greater in the host (and the waste products thereof) than when diluted in streams. So your chances of getting the Hollering Crud from direct contamination (food, hands, or shared utensils) are greater by far than those of getting it from the water—the freedom of the hills doesn’t include freedom from dishwashing.

Another major concern is temperature. The dormant, shelled oocysts are very tough little customers. In water near freezing, Giardia cysts can survive more than 80 days. Shigella bacteria can camp for long periods in ice, and so can viruses. Boiling, on the other hand, wipes all of them unquestionably out.

BOILING TEMPERATURE OF WATER BY ELEVATION

| Elevation (Feet / Meters) |

Boiling Point (Degrees F) |

Boiling Point (Degrees C) |

| 0 / 0 | 212.0 | 100.0 |

| 2000 / 610 | 208.3 | 98.0 |

| 4000 / 1220 | 204.7 | 96.0 |

| 6000 / 1829 | 201.1 | 93.9 |

| 8000 / 2439 | 197.4 | 91.9 |

| 10,000 / 3049 | 193.7 | 89.8 |

| 12,000 / 3659 | 190.0 | 87.8 |

| 14,000 / 4268 | 186.3 | 85.7 |

| 16,000 / 4878 | 182.7 | 83.7 |

The boiling temperature decrease per 1000 feet is 1.83°F or 1.02°C.

The thermal death point (TDP) is the temperature at which no organism can survive for five minutes. In Purification of Wilderness Waters, author David Cooney gives a TDP for Giardia of 147°F (64°C). Other protozoans have TDPs from 147 to 169°F (64–76°C). Sustaining a temperature of 170°F (77°C) for a minute or two kills ’em all.

The drawbacks are several. Boiling takes significant time and fuel. Cooling the water takes yet more time, and it tastes like hell unless it’s poured between two containers to aerate. Teas or drink mixes can cover this to some extent. And also, boiling won’t remove, and in fact may concentrate, nonvolatile poisons like arsenic.

The main types of chemical treatment are:

Chlorine. The amount of chlorine in city water supplies (less than 0.5 milligram per liter) won’t kill Giardia or Cryptosporidium cysts, and even higher doses aren’t very effective. Chlorine loses its punch in cold or alkaline water (with a pH above 7.5, found in lakes with limestone or dolomite bedrock and in desert “sinks” with no outlets). Neither does it work well in waters with high organic content (silt, algae, etc.). A contingent worry is that chlorine reacts strongly to organic matter in water, producing chloramines or trihalomethanes, both carcinogens. But for occasional use, liquid chlorine bleach (5 percent sodium hypochlorite) remains a cheap treatment, at 0.2 milliliter per quart with a 30-minute contact time—never use powdered laundry bleaches, nor any with additives. The former standby, Halazone, takes five tablets to treat a quart of water (30-minute contact) and is highly perishable, losing 75 percent of its chlorine after two days’ exposure to air. Newer chlorine treatments include Aqua Mira (two bottles, 1 oz. each, about $12), that treats 115 liters using chlorine dioxide and phosphoric acid. These must be mixed, seven drops each, and allowed to stand five minutes before going into the water bottle, with a 20-minute contact time. Chlorine-treated water can also be used to wash fruits and vegetables. After sufficient contact time, adding ascorbic acid (vitamin C) will reduce the hypochlorite to a colorless, odorless chloride. This also works with iodine, which changes to iodide. The taste improves, but chloride and iodide don’t kill gazigglies. So, since many drink mixes contain ascorbic acid, never add anything to the water before the full contact time has elapsed.

Iodine is cheap, lightweight, and thus much favored by mass-market outdoor programs, a circumstance that has brought a couple of problems to light. First, some people are rather allergic to it. (If you’re allergic to shrimp, you might be sensitive to iodine.) And this is something you should determine before setting out, either with the help of a doctor or through home trials: get bottled water and treat it, drinking nothing else for a day to see what happens. But for the majority who aren’t allergic, military testers claim that iodine is safe. Although other sources claim that it builds up to a toxic level in the body and shouldn’t be used continuously for weeks or months. Second, iodine won’t kill Cryptosporidium, perhaps the most common waterborne parasite of all. Third, it has a definite gag factor. And fourth, it is said to react with some foods and perhaps the aluminum in cookware: readers report purplish soups.

The most popular iodine tablets are Potable Aqua (tetraglycine hyperiodide, a bottle of 50 tablets; 1 ounce [0.2 ounce net]; $6). The tablets are only for treating water—they’re poisonous if swallowed—and must be kept dry, since they lose one-third of their effectiveness if exposed to air for four days. So don’t try to save weight by carrying them in a plastic bag; take the bottle along, always recap it tightly, and if it has been opened or is of indeterminate age, get a new supply. A yellow tinge is said to be a sign of deterioration. Potable Aqua Plus is a kit ($7) with the iodine pills as above and a neutralizer called PA (45 mg ascorbic acid per tablet) in a second bottle of 50. Similar, except for the green blister pack, are Coghlan’s Drinking Water Tablets and Neutralizer. A less costly iodine treatment with unlimited shelf life is Polar Pur (99.5 percent iodine crystals, about $10), which treats 2000 quarts. Each bottle holds about 7.5 grams of iodine in little beads, with an insert to keep them in the jar. You fill the bottle with water (5 oz. or so) and wait for the iodine to form a saturated solution. The bottle says one hour. But the first time out, David Cooney found that after an hour at rest, less than one-third of the iodine had gone into solution and that full saturation took 5 to 6 hours. So you should fill a new bottle the day before you leave home. He recommends shaking the bottle at intervals. The gentle motion of walking helps, but tucking it into a gaiter is a more vigorous option. Just make sure the cap’s tight. Once the bottle’s in play, you use only part of the contents, adding fresh water each time, so it’s easier to maintain the strength. On the side of the bottle are temperature-sensitive dots with a corresponding dosage scale, in capfuls. This works out nicely for clear water, but for cold, cloudy, or alkaline water you should double both the dose and the contact time.

Iodine can kill some protozoans, such as Giardia. But a published test using clear, cold (10°C/50°F) water showed that after 30 minutes virtually all commercial iodine treatments left more than enough Giardia cysts alive to make you sick, with some taking up to eight hours to kill all cysts. In the same tests, none of the chlorine treatments racked up a 100 percent kill.*15

In water 20°C (68°F) and above, an hour or two of iodine treatment might kill nearly all the Giardia cysts. Yet another caution is that the tannins released by leaves and other organic matter react to form iodide ions, which (I repeat) do not kill gazigglies. And since iodine doesn’t work on Cryptosporidium, many of these products bear labels urging the use of a filter.

If you’re on a Thoreauvian budget, you can buy tincture of iodine (crystals dissolved in grain alcohol—a 1-oz. bottle costs less than $1). But it has to be measured out, and the good Dr. Cooney suggests the small plastic bottle intended for eyedrops—carefully washed out and labeled IODINE with indelible marker—with five drops per liter as the starting point. You can also get food-grade ascorbic acid (vitamin C crystals) and dash in 1/10 teaspoon per liter after the contact time, with a good shaking, to neutralize the uck.

Other universals: For best results, turbid water should be settled and/or filtered through a paper coffee cone before going into your drinking bottle. After you add water treatment, shaking speeds up the process. And since you’ve just put untreated water in your bottle, before you drink loosen the cap slightly and upend the bottle, letting enough water leak out to rinse the rim and threads.

Water filters and purifiers

have the the same object—to clean up your drinking water—but there are significant differences in how they work. After having standards for purifiers for some time, around 1998 the U.S. Evironmental Protection Agency (EPA) published standards for water filters. Devices that pass the test display a registration number, but it still pays to learn the basics.

A filter works by passing water but trapping microorganisms and particles. So the vital measurement is pore size, which can be stated in two ways: nominal pore size is an average, meaning that there are both smaller ones and larger ones. A nominal 5-micron filter may have some pores large enough to let a Giardia cyst through. A 5-micron absolute pore size means that no pore is larger than 5 microns, so the filter will trap Giardia cysts. Some filter makers claim to meet two of the three parts of the EPA standard for purifiers (see below). But no mechanical filter can remove viruses, which is the third part of the standard.

A purifier, as certified by the EPA, is able to “remove, kill, or inactivate all types of disease-causing microorganisms from the water, including bacteria, viruses, and protozoa cysts…” It must remove 99.9 percent of the protozoans and 99.9999 percent of the bacteria, and also inactivate 99.99 percent of the viruses, which are too small to filter out.*16

To do this, the typical purifier combines a physical filter with chemical action: most have a resin matrix that releases iodine to inactivate bacteria and viruses. Others have a silver-impregnated element, or a bed of activated carbon. Silver inhibits bacterial growth in the filter itself, but doesn’t have much effect on water passing through. Activated carbon (or charcoal) takes up dissolved chemicals by adsorption (meaning their molecules stick to the carbon particles) and can remove pesticides, herbicides, chlorine, and iodine, as well as funky odors and tastes in general. So carbon is commonly used either as part of the filter element or in add-on cartridges.

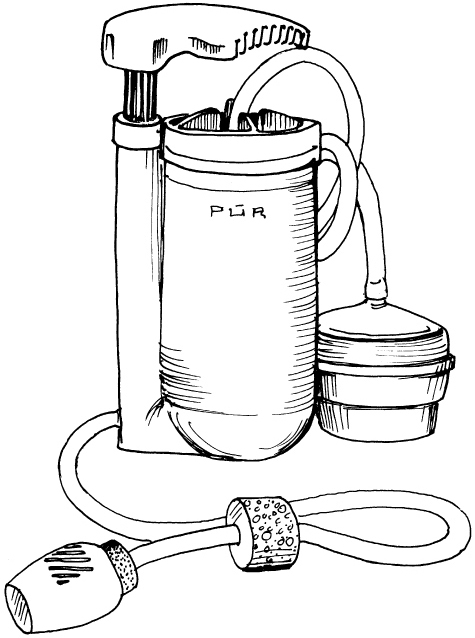

PUR Hiker

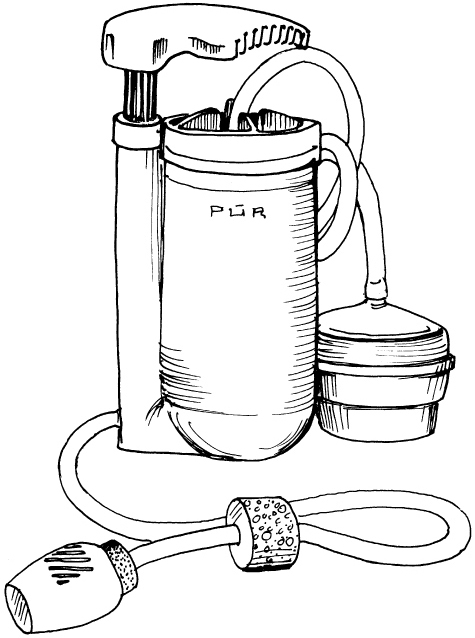

Sweetwater Guardian

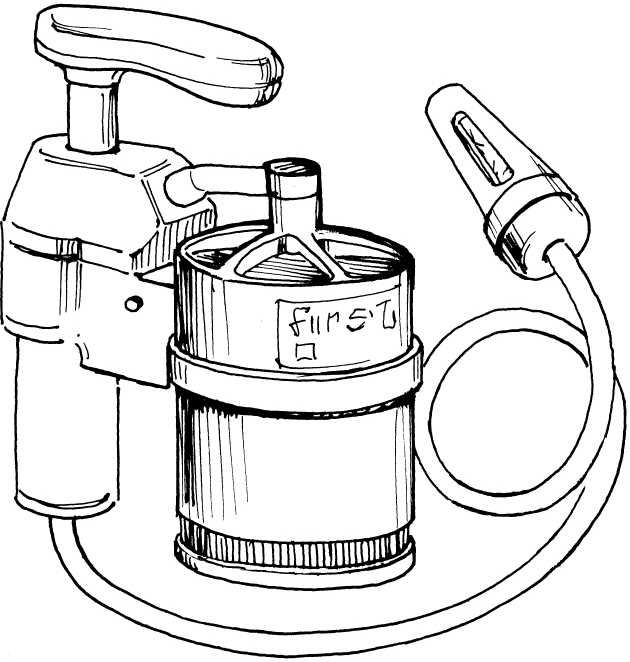

First Need Deluxe

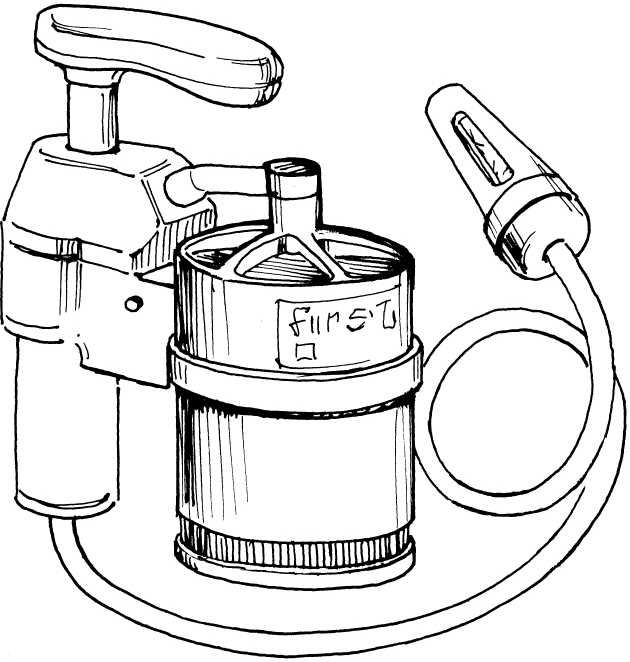

MSR MiniWorks

Katadyn Mini Ceramic

Coghlan’s

Filters for backpacking are made of ceramic, carbon, various fabrics or fibers, and plastic meshes or matrices. Because a filter with pores fine enough (2–3 microns) to trap small cysts will clog up very fast indeed when plastered with silt, algae, and other waterborne gunk, some filters deploy metal or fiber prefilters to catch the coarse material. The coarse screens can usually be brushed off when they clog. Then comes a midlayer of fibers or small-pored ceramic and backing that may be a core of carbon. Some fine-filter elements can be cleaned, by brushing, scouring, or backwashing, while others must be replaced. The carbon part retains chemicals and must be replaced. It’s very important first that you be able to clean or replace the element in the field, and second that you be prepared to. That’s the general poop. For specifics, we need to talk about makes and models. The following combines what the companies say, Backpacker tests, and my own subjective take after several seasons. (During which, as a matter of record, I experienced zero Belly Vengeance.)

The PUR Hiker (15 oz., $60, replacement filter $30) is sturdy, rounded, and easy to live with. Backpacker’s test crew rated it more than twice as high as the two runners-up. The body is a speckled plastic with a built-in pump and a thread-in filter cartridge that mates a pleated 0.3-micron absolute glass-fiber body (with a high 126-square-inch surface area) with an activated carbon core. Intake is via a plastic “acorn” with a removable (and easily cleaned) foam core. But you should be careful pulling the tube off to remove the foam—the little spurs that hold it break rather easily. A movable float lets you keep the intake off the bottom, which is smart. From the acorn, a flexible tube leads to the filter/pump unit. The pump has a well-shaped handle, a moderate (8-lb.) force, and a high output (1.24 liters per minute at 48 strokes). You can set it on a rock or your knee to pump, and the tubes are long enough to avoid a dunking. The filter resists clogging (it’s rated for 757 liters) but it can’t be cleaned, so carrying a spare might be in order for glacial melt, warm-water sloughs, or desert potholes. Replacement takes only seconds. The filter core seems resistant to freeze damage but can be fully drained and the innards dried out, just in case. The plunger comes out easily—for long trips a spare O-ring will cover you for maintenance. The outlet tube leads to a bottle adaptor that fits all but the popular 1-liter soda bottles. But you can pull it off and use the bare tube, saving ounces. Gripes are few: the main one is having to unscrew the filter and prime the pump, a matter of 10 seconds if you pull the outlet hose off first. Otherwise things get twisted. But if the filter is wet you might not need to prime it. The 0.3-micron pore catches protozoan cysts and almost all bacteria. PUR also makes a lighter, cheaper, lower-capacity filter, the Pioneer (8 oz., 0.75 liter per minute, $35) that threads onto a Nalgene widemouth bottle and comes with two replacement disks ($8, sold separately). But most backpackers will be happier with the Hiker or one of PUR’s purifiers: the similar Voyageur ($75; $40 replacement), or the double action, T-handled Scout ($90; $45 replacement), which Linda has used with great satisfaction, or the self-cleaning Explorer ($130; $50 replacement).*17

The Sweetwater Guardian (12 oz., $50; replacement cartridge $30) resembles those old iron homestead handpumps by virtue of its leveraction handle but is blessedly light in weight. Easy to hold and pump (only 2.0 lbs. of force), it nevertheless puts out a steady 1 liter per minute. The filter of glass fiber with a carbon layer has a 0.2-micron absolute pore size. It clogs more quickly than the PUR Hiker, but this is signaled by a squirt of water from the relief valve (see below) that prevents filter rupture or bacteria “push-through” when you pump too hard. Rated for 757 liters, the filter element can be cleaned in the field with a brush (included), taking only about 15 seconds. When it’s worn out, a black grid pattern shows up. The replacement cartridge is roughly the same size and weight as the one for the PUR Hiker. The inlet is a plastic capsule with a 75-micron stainless screen that plugs into a flex tube and is good for shallow water. A 5-micron prefilter, called a SiltStopper, can be added betwixt inlet and cartridge (>1 oz., $10, with a three-pack of replacement elements costing $13). The outlet tube is plenty long, and the plastic adapter does fit smallmouth soda jugs. The outlet nipple and tubing are smaller than those on most flexible bladder systems (see this page), though with some effort you can jam the stock outlet tube inside the tube from the bladder, and pump gently. Gripes: The handle needs to be deployed each time you pump, and some people report breaking the plunger, which can’t be fixed. The pump itself doesn’t come apart (as far as I could tell), so while the rubber washer is visible through holes, it can’t be replaced. If you pump too hard or the filter starts to clog, the relief valve squirts—if you catch it in the face, it rates 0.5 cougar screams: find it before it finds you. (Hint: turn the pump shaft so the exit hole points away.) A Viral Guard cartridge, to upgrade the Guardian to a purifier, was sold until 2000 when Cascade Designs’ own microbiologist found that “portable iodine resin bead technology, as used in the Viral Guard, does not meet the EPA standard for purifiers in a number of water conditions commonly found in the outdoors.” Since EPA tests are performed in the lab, not the field, this might have gone unnoticed, but Cascade Designs—commendably—pulled the Viral Guard off the market. The Guardian, which I ended up liking rather well, and the Walkabout microfilters (0.2 micron, 9 oz., $40; replacement $19) are unaffected by the problem.

General Ecology’s First Need Deluxe Purifier (15 oz., $80; replacement $36) is an amalgam of virtue and vice. It was the first filter (or purifier) I used. It was hard to hold and the cartridge clogged up quickly, but it was better than anything else around at that point. Further along, some friends invented a prefilter with stiff tubing and faucet strainers. I figured out how to backwash the cartridge before the company agreed that it could be done (now they give you directions). So this little beast has a history with me. The filter itself is a mysterious, blue plastic cartridge that can’t be opened. Called a “structured matrix,” it somehow removes 0.1-micron gazigglies with a 0.4 absolute pore size. It also captures dissolved chemicals with “molecular sieving” and “broad spectrum adsorption,” and removes colloids and the smallest particles by “electrokinetic attraction.” The rated life is 400 liters, which presumes relatively clear water and regular backwashing. This can be done in the field by pumping water slowly through the clogged filter into a liter or quart bottle, treating it with five drops of liquid bleach (or, according to the product engineer, with an iodine treatment). After the proper contact time (30 minutes) has gone by, disconnect the pump from the cartridge and clean it with a few squirts. Then connect the pump outlet to the outlet (i.e., the bottom) of the cartridge and pump the filtered water through gently. Little bits of stuff will come out of the cartridge inlet hole. Tapping the cartridge lightly against your hand between pumps will dislodge more bits. Pump all the treated water through and it’s done. Though it’s not a quick fix. A bottle of blue coloring is included to test the filter cartridge. Recent improvements are the ergonomic pump handle, a quick-release bracket that attaches the pump to the cartridge, and a self-cleaning mesh prefilter with a sliding float. The pump is double-action and fast (with a new cartridge) and can be taken apart for maintenance. The cartridge has gained a built-in set of adapters that thread onto a Nalgene widemouth bottle, and a small set for a Sigg (or equivalent) aluminum bottle. It won’t match up with 1-liter smallmouth soda bottles, but you can slip on an outlet tube or the tube of a bladder system (also the case with the PUR Hiker and MSR MiniWorks). Since my gripes have been aired, they need not be repeated. The First Need Deluxe also includes an auxiliary nipple that converts the stuff sack (with a plastic bag as a liner) into a gravity system. You fill the bag, hang it, plug a hose to the pump inlet, give a few strokes to start the flow, and sit back as your bottle fills—Nice-a-roo. The rate depends on the drop between bag and bottle—with the stock 3-foot tube, it filled a 1-liter bottle in less than 10 minutes. A double-action pump is required, it seems, or you can use the cartridge alone and suck heroically on the outlet hose to start the flow. If the cartridge is too clogged to pump through, you can still filter water with gravity flow. General Ecology also sells the Microlite System purifier (1 micron, 8 oz., $44; replacement two-pack $8) and the Microlite filter unit alone (7 oz., $33).

MSR makes a chunky, solid filter called the MiniWorks (15 oz., $60; Marathon ceramic element $30) that justifies its weight with some distinct advantages. Like the Sweetwater, it has a pump handle, but the plunger is horizontal: easy to hold, with moderate force required to pump. The plunger and a rubber O-ring are housed in clear plastic, so you can spot problems. The element, housed in black plastic, is ceramic with an activated carbon core (0.3 micron absolute), and is cleaned with a scouring pad. This takes off the surface, exposing clean ceramic, for a relatively long life. A built-in gauge lets you know when it’s worn out. The inlet has a spring weight over a plastic capsule with a dab of foam as a prefilter—easy to take out and clean, and also easy to lose. A float keeps it off the bottom. The outlet has a cap and threads that fit a widemouth Nalgene bottle or MSR’s Dromedary waterbags. But it also has a nipple, so you can slip on a flex hose and use the adapter of your choice. The pricier Waterworks II filter ($130) has the Marathon filter element in a clear housing and an added PES membrane filter (0.2 micron absolute) that screens out the smallest pathogenic bacteria. Both models are easy to work on—for long trips a maintenance kit ($8.50) is in order. Gripes were few, though the flow rate (0.7 liter per minute) seemed a bit slow for the size and weight, and the ceramic element can be damaged by freezing.

Katadyn’s Pocket Filter has been around for years and has the highest capacity (tens of thousands of liters), but I bypassed it for several reasons: a) at 1 lb. 10 oz., it’s heavy; b) the handle is small and pump force is high; c) having to direct the outlet stream into the bottle is a cramp; and d) it costs $250. Colin used one on his solo Colorado River descent and had clogging troubles. The Katadyn Combi costs less ($160) but it’s an ounce heavier. So I tried the Katadyn Mini Ceramic filter (8.5 oz., 0.2 micron, $90; replacement $60), which one of my friends called “a cute little booger.” Compact and mechanically simple, it fits the hand nicely. The single-pump O-ring is easily examined and replaced. The ceramic element has a small surface area that clogs rather quickly but is easily scrubbed with an abrasive pad for a long life (7000 liters). The tiny stainless inlet strainer also clogs, so an equally tiny brush might be in order. The inlet hose stows neatly under a trapdoor, which popped open—I used a thick rubber band to hold it closed. The pump force was high and the flow rate was slow. And the outlet hose was too short and springy to stay in my bottle (though it did jam nicely inside the tube of a bladder system). So why did I like it? Hmmm. It’s light and easy to pack. Has a long life. And it is cute.

The Coghlan’s Water Filter or the similar Timberline Eagle (6 oz., $25; replacement $13) can be found in discount stores and even in supermarkets. It’s neither durable nor easy to hold, but it gives me a certain Rube Goldberg–ish delight. The pump is the sort found in gallon jugs of shampoo, with the spout cut off to admit a skinny outlet tube. Into the inlet (the part that sticks down into the shampoo) fits a short tube with a sleeve inside that holds a 1-micron polyethylene and fiberglass element. This will catch Giardia and Crypto cysts (though not bacteria or viruses) and is rated for 400 liters, though it seems to clog quickly and can’t be cleaned: carry a spare. The pump is a surprise in terms of sheer volume, but the teeny outlet hose couldn’t accommodate the flow, and popped off in a magically off-pissing way (see below). Since this leads naturally to the gripes, the filter element itself is the inlet, so you have to immerse it in the creek. But the tubing tends to slip out of the pump, dropping the filter element. In fast water, that could be good-bye. Even in the event you don’t lose it, “wild” water will have contaminated the inside of the filter element. If this happens, you should disinfect it, or at least pump a few cups onto the ground to wash it out. The best course is to duct-tape the join of the tubing to the pump. The tubing fits the filter nipple securely, and you do need to take the element off to pack it. But if you plop the element wet into a plastic bag, dribbles can also contaminate the outlet. So you should shake the water out of the filter before packing it, and a little cap might be in order (search in the parts boxes at a hardware store—if you want to take the parts-bin riff a little further, read on). Besides the duct tape, another slight modification does wonders for both the performance and your temper, to wit: I trimmed off the plastic around the pump outlet until I could slip a larger (1-cm) tube over it. This ends the pop-out problem and thence, the pump filled a 1-liter bottle with the same 36 strokes, in half the time. The stock outlet tube has a copper weight, and it still comes rocketing out of the bottle if you pump hard, so I added a thick rubber band to hold it in. Once I started to tinker, I couldn’t quit—see the customizing section below.

Meanwhile, what with Mark Jenkins’s article and Kristin Hostetter’s field tests from Backpacker, supplemented by David Cooney’s minibible, I was swamped with data. So, besides carrying all of the above filters on wilderness trips and risking La Vengeance by pumping water directly below sheep fords and hunting camps—with no evil results—I wanted to compare what matters to me: How many strokes to fill my bottle? How long will it take? And last but not by any means least—am I likely to smash this thing against a rock? So after a festive evening, I ratcheted myself up at 5:00 a.m. for a predawn (and precoffee) test.

Conclusions. To generalize, ceramic filters (Katadyn, MSR) are harder to pump, have lower flow rates, and clog more quickly. They’re also likely to be damaged by freezing. But they’re fairly simple to clean and maintain, with exceptionally long life. Fibrous filters (PUR, Sweetwater, Coghlan’s), some backed up with carbon, have higher flow rates and higher maintenance costs, since the elements must be replaced at shorter intervals than those of ceramic.

A powerful pump and a thundering flow rate might seem like the Holy Grail, but some of the critters you’re trying to catch can slim down to ooze through pores smaller than their normal size (and pressure may help them do this). So in the field, pump slow and steady. While microfilters (absolute pore size smaller than 1 micron) seem to be sovereign against protozoans and bacteria in U.S. waters, EPA-certified purifiers (First Need, PUR, MSR) add protection against viruses. But since most depend on iodine resins or other time-sensitive means, once again it’s best to pump at a slow, steady rate. This also prevents forcing unwanted crap through the filter. You can dependably purify water microbiologically by treating with chlorine or iodine, then filtering. Or, of course, letting it boil for one minute. Since none of these methods removes dissolved chemicals, a post-filter with activated carbon might be an asset.

Exstream MacKenzie

Safewater Expedition

Bottle/filters. Bota of Boulder sells the Outback (2 microns, 5 oz., $18; replacement $9), a bike-type bottle with a filter cartridge that fits tightly inside the rim. You unscrew the top, take out the cartridge, then fill the bottle with “wild” water (leaving room for the cartridge, since otherwise, wild water spurts out around the edges and contaminates the tame side of the filter). You screw the top back on and tip it up, squeezing the bottle to force water into one of those push-pull nozzles. Unfortunately, the plastic of the bottle is stiffish and the filter offers enough resistance to make this an ordeal, especially with your arm cocked high. Those with a less-than-simian grip will be flummoxed.

Exstream Water Technologies outfits its MacKenzie bottle (9 oz., $45) with a 1-micron filter/EPA-registered penta-iodine purifier that will treat up to 26 gallons. This unit extends nearly the full length of the bottle, reducing the 1-liter volume somewhat. The bottle itself is a squeezable white plastic, demanding only moderate grip strength. The push-pull mouthpiece has a tiny outlet hole, probably to prevent overloading the filter, so it takes time to get a mouthful. Even so, the MacKenzie seems like a decent bet for overseas trekking and travel, where viruses are a concern.

Safewater Anywhere makes the Expedition bottle/filter of translucent plastic (1 liter, 6 oz., $40; and ½ liter, 5 oz., $35; replacement $25). The three-layered filter, of “medical-grade, micro-porous plastic,” has 2-micron absolute pore (which is claimed to catch smaller beasties by offering a “tortuous path,” in the manner of a Swiss cheese). It removes protozoans, bacteria, and a range of unsavory chemicals, but not viruses. Though small and lightweight, it’s rated for 750 liters (over 185 gallons). The bottles have a widemouth screw cap on the bottom and a drinking nozzle on top, under a conical flip-cap. You take off the bottom cap to fill up, and find a prefilter “sock” of 25-micron fabric with a tail so you can pull it out and swish it clean—without removing it from the bottle. Once again, you have to immerse the bottle to fill it (in shallow water this means you pick up silt, algae, grit, etc., which the sock is intended to catch). Recapping the bottom, you let the drips drain off, flip open the double-gasketed top, squeeze, and drink from the mouthpiece. The flexible bottle and low-resistance element reduce the effort—it’s grand to dip water from a cold, babbling brook and down it immediately. In places with plentiful streams and lakes you can save considerable packweight by dipping just enough to satisfy your thirst. But I had two quibbles, one specific and one general. Specifically, when I flipped up the cap to drink, I found droplets inside. Had the double gaskets leaked? (If you close it carelessly, they will.) But eventually I figured out that the mouthpiece was the guilty part. While this soothed my fears of contamination, it meant that the bottle had to be kept upright. The company promises a redesign and I wish them well.

So on to the general quibble: if you expose this, or any translucent container holding “wild” water to sunlight, things bloodywell grow in it. The company provides a mesh sleeve, encouraging you to sling it outside your pack. Naturally, this boosts the growth rate. All the zoo- and phytoplankters you’re culturing not only add unwelcome color notes but if allowed to proliferate also clog the hell out of the filter element. Frequent changes of water help. Regular cleansings and dry-outs do, too. So does keeping it out of the light. (More on this when we get to hydration bladders, this page.)

A slick little packet is Safewater’s 3-oz. in-line filter cartridge (with a stainless 25-micron prefilter and the 2-micron filter element specced on the previous page, at $35), which plugs into the drinking tube of a hydration system. The same low-resistance element as in the Expedition bottles allows you to drink without inordinate hollowing of the cheeks. And given the general catch about putting “wild” water in your hydration bladder, it’s not a bad system. Yet another application is gravity filtering. I rigged it to a bladder (a Platypus Big Zip, which opens for easy filling and cleaning). With a 5-foot drop, the Safewater cartridge filtered a liter in 58 seconds—no pump required. By the same token, since it has a built-in prefilter you could stick a tube on either end (upping the weight to perhaps 3.3 oz.) and simply suck up the blessed quench. This one goes into my ditty bag, for sure.

Safewater in-line cartridge

The newest development, and maybe a trend, is to minifilters that fit in the neck of a bottle or plug into the tube of a drinking bladder. This seems like a grand notion but in practice creates its own set of problems, some of which I stumbled upon. The Gatekeeper, from TFO, Inc. (0.6 oz, $12, two-pack $20), is a minuscule cartridge rated to filter 25 gallons. It snaps into the underside of a 28-millimeter cap/mouthpiece (included) that fits TFO and Platypus bladders (or the ubiquitous 1-liter soda bottle). A hearty squeeze—and patience—is required to get a mouthful. Nevertheless, the extraordinary lightness, low cost, and adaptability all make it attractive. I used a Gatekeeper–tonic bottle combo on a 70-mile trip during a prolonged drought, when I was forced to dip soupy water from beaver ponds and cow-flopped water pockets. Aside from the unsavory visuals, the only bad moment came when the teeny filter cartridge popped out of the cap as I unscrewed it and dropped into a creek—fortunately a mere trickle. Still, it bounced off downstream. I retrieved it, lashed the outside with rum, and then squeezed water through to flush out any stunned gazigglies—with no ill effects, except on the rum supply.

Customizing. Each of these models seems to have a particular advantage, which tempted me to try swapping things around. Needless to say, the makers do not condone this, and will curse me for even suggesting it. Understand—I’m not urging you to alter a single jot or tittle. But I can’t resist. So here are various irresponsible substitutions and field-grade tips.

Truly mucky or tea-colored water should be settled, but if you’re on the run you can rubber-band a coffee filter, etc., over the inlet boggle.

MSR uses a steel spring to weight their inlet hose, which, combined with a sliding float, gives you superior control of the depth. For squirrelly inlets, you can find a similar spring to slip over the hose. Or wrap some bare copper wire (10- to 14-gauge) tightly around a dowel, thence twisting it onto the errant tube.

The mighty bulk-shampoo pump (a mere 2 oz.), as modified above (this page) with a fat outlet tube, can be used handily with different cartridges and inlet screens. For instance, I stuck the Sweetwater 75-micron inlet screen on as a prefilter and tubed the shampoo pump’s outlet to the Safewater in-line cartridge, comprising a slick-and-thrifty system with two prefilters that weighs 6 ounces and will draw from the shallowest water pocket. A piece of foam pipe insulation (the kind with the slit) augments the grip—but don’t cover up the vent holes. The detachable, durable, double-action First Need pump also lends itself to this unhallowed approach. (Just remember to stroke gently.)

Water in an emergency

COLIN: Cunning ideas are always being propounded about what to do if you run out of water. Typical examples are “Catch the rain in a tarp” and “Shake condensed fog off conifer trees” and “Dig in a damp, low-lying place.” Then there are various crafty systems for distilling freshwater from the ocean. In an Armed Forces Research and Development publication I once ran across a description of what at first seemed a practical rig for seaskirting backpackers: a series of foil sheets between which you heated salt water, either in the sun’s rays or “by sitting on them.” But right at the end came the killer: “With additional sheets, a survivor can obtain about one pint of water in 16 hours.”

Unfortunately, the occasion on which you’re really in desperate straits for water is pretty darned sure to come just when there is no rain, no fog, no damp place, and no ocean (not to mention no sheets of special foil). In other words, in the desert, in summer.

For years the only advice I’d heard that sounded even vaguely practical was “Cut open a barrel cactus.” An experienced friend of mine says he rather imagines you’d “extract just about enough moisture to make up for the sweat expended in slashing the damned thing open.” But the Air Force Manual (no longer available) exhorted you, when in a desert fix, to “cut off top [of a barrel cactus], mash pulp, suck water through grass straw or mash the pulp in a cloth and squeeze directly into the mouth.”

The Manual also gave details of the desert still described in earlier Walkers.*18

The beauty of the device is that it works best in the time and place you’re most likely to need it: summer desert. The hotter the sun, the more water you get. And the water is as pure and clear as if it had been distilled in a laboratory. An Air Force medical colonel called this still “the most significant breakthrough in survival technique since World War II”—and the colonel headed a team that experimented with the still for 25 days in the Arizona desert. The team essentially confirmed the findings of the original researchers, and there seems no reason why this still shouldn’t save your life, or mine, if either of us ever gets into water trouble while backpacking in the desert—provided we have a clear understanding of what to do.

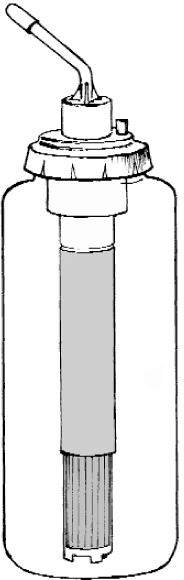

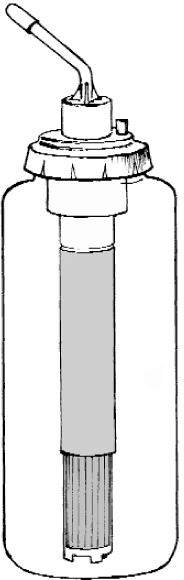

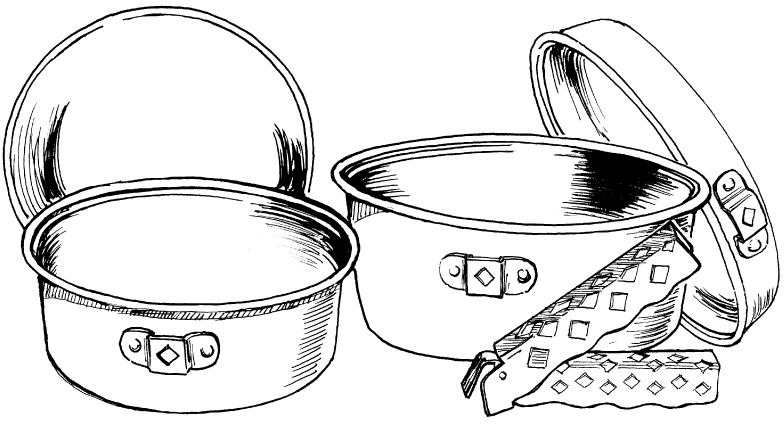

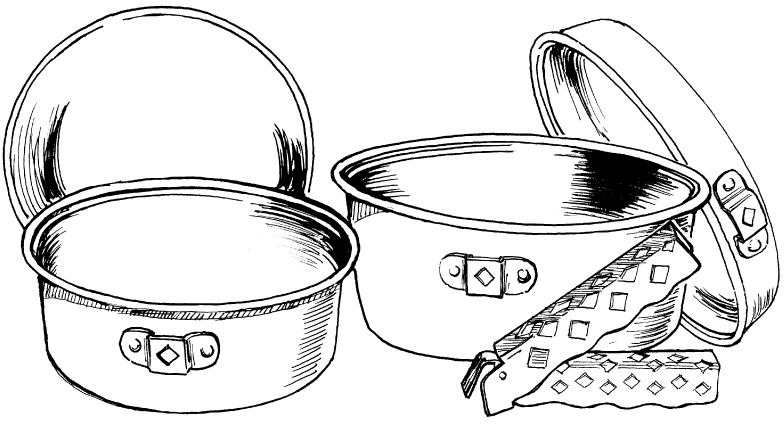

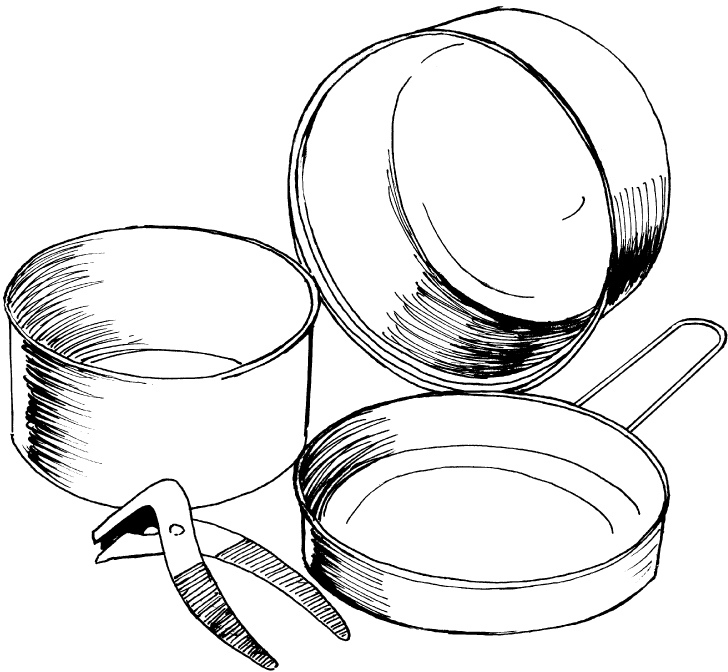

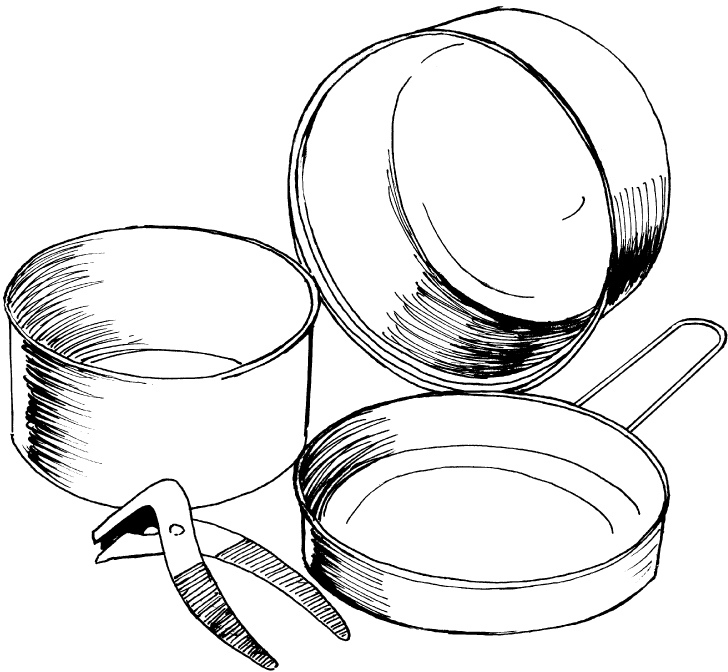

The still’s only essential components are two items we might seem reasonably likely to carry: a container to catch the water and a 6-foot square of clear or almost clear plastic sheeting. Up to a point, the container is easy: a cooking pot or cup or a plastic bag or even a small piece of plastic sheet or aluminum foil shaped into a hole in the ground. But the container should be wide enough to catch all drops falling from the sheet—as a cup would not. And a metal container will get very hot and “boil off” some of its precious water. So a cooking pot will do but a plastic bowl or bucket will do better. The plastic sheet raises unexpected problems, but as we’ll see there’s a way out.

A desirable but not essential component for the still is a piece of flexible plastic tubing, 4 to 6 feet long (the kind sold for aquariums is fine). For other reasons, you might consider taking some (see footnote on this page). Most water filters and drinking bladders (this page and this page) have suitable lengths of tubing.

Constructing the still sounds a simple enough job for even a weak and scared man, provided he has kept a modicum of his cool: Dig a hole about 40 inches wide and 20 inches deep. Dig the sides straight down at first, then taper them in to a central cavity (see illustration, this page). Failing a toilet trowel (this page) or a staff or stout stick, your bare hands will do the job, provided the soil isn’t too rocky. When the hole is finished, put your container in its central cavity. If you have plastic tubing you should tape it inside the container so that one end lies very near the bottom. Lead the other end up out of the hole and seal it by knotting, or doubling and tying with nylon. Next, stretch the plastic sheet over the hole and anchor it around the edges with soil. Alternatively, you can dig a circular trench, about 4 inches deep, a few inches beyond the perimeter of the still, in which to stuff the edges of the plastic—and so obviate any problem with dirt sliding down the sheet into the pit. Next, push the sheet down in its center until it forms an inverted cone with sides 25 to 40 degrees from the horizontal. The plastic should run 2 to 4 inches above the soil and touch it only at the hole’s rim. Place a small, smooth stone or other weight dead center to hold the conical shape and reduce wind flutter. Pile extra soil around the edge to hold the sheet firmly in place and block off all passage of air. In high winds, reinforce with rocks or other heavy articles. Leave the free end of the plastic tubing uncovered—and clean. Estimated construction time: 15 to 30 minutes.

This simple structure works on the same principle as a conventional still: solar energy passes through the clear plastic and heats the soil (or added plant material—see below); water evaporates, condenses on the plastic (which is cooled by wind action), runs down to the point of the cone, and drops into the container. It takes one to two hours for the trapped air to become saturated so that water condenses on the plastic and begins to drip into the container. With a plastic tube you can suck up water at any time; without it you have to keep removing the container—and each time you do so you lose one half to one hour’s water production.

The apparently simple business of the water running down to the point of the cone raises the first plastic sheeting difficulties. Clear plastic groundsheets are polyethylene, which is slick, especially when new; it sheds many drops before they reach the cone’s apex—and can reduce yield by about half. Any used groundsheet will be scratched, and water will adhere rather better. And scouring the sheet’s undersurface with sand might make a critical difference. (I don’t suggest you do it ahead of time: just file the idea away in your mind for emergency use.) But there are other groundsheet difficulties. A sheet punctured in any way, even with small holes, will drastically reduce the still’s yield. Possible remedy: patch with ripstop tape. Again, the thinner the sheet, the more efficient: 1 mil is ideal (dry-cleaner bags, for example—though they’re polyethylene). But a 1-mil groundsheet is close to useless; mostly, they’re at least 3 or 4 mil. Finally, any loss of transparency, such as accidental or deliberate scratching, will further reduce the still’s yield. In other words, a transparent groundsheet, somewhat scratched and with all holes patched, will do at a pinch. But a thin special plastic, such as Du Pont’s Tedlar, will do far, far better. Unfortunately, Tedlar is 20 times as expensive as polyethylene and is not readily available to the public. I don’t at present know where you can buy any—either alone or as part of the complete desert-still kit that used to be sold by a California firm. I regret to report that Du Pont has steadfastly ignored my inquiries on both counts.

A sandy wash makes the best site for your still. Next best is a depression where rain would collect: months after a shower such places still retain more water than does nearby high ground. The finer the soil, the better. Make every effort to site the still where it will get day-long sunlight.

After long droughts you may be able to collect only small amounts of water from even favorable soil; but—and it’s a gigantic “but”—you can probably save the day by lining the sides of the hole, under the plastic, with vegetation cut open so that its moist interior is exposed. Cactus is best. Prickly pear and barrel cactus yield most; saguaro comes next, cholla a poor fourth. Creosote bush helps very little.

The vegetation should not touch the plastic; it may flavor the water slightly. Small ledges made in the sides of the hole may make it easier to keep the vegetation in place.

Seawater or brackish water (as found in many desert lakes) can be purified by building the still where the soil is kept moist by the underlying water table. Or keep adding the polluted water—either into a trough (see below) or by pouring it well down in the hole, not up near the rim, where condensing water could touch the soil and carry impurities down into your container. If the soil is badly contaminated on the rim (by strong alkaline deposits, say) your precious harvest of water may be fouled, so raise the plastic slightly with small rocks placed underneath it, all around the hole. With these precautions you can even—cozy thought—operate in a region made radioactive by fallout.

Slightly modified, the still will purify water polluted by almost anything except antifreeze from a car radiator. So your body wastes become recyclable. To make full use of polluted material, dig a trough halfway down the hole (see illustration, this page), line it if possible with a plastic sheet, and pour the material in.

Yield will depend on many factors, but it seems reasonable to expect at least a quart a day from a properly constructed still dug in desert sand containing some moisture or lined with cut cactus. And although there seems to be an upper production limit of about 3 quarts a day for such stills, that yield can in relatively moist soil or with a good vegetation lining be maintained for four or five days. After that, make a new still or replace the vegetation. These 40-by-20-inch stills are the optimum size: if you need more water—and have the necessary materials—make more stills rather than a bigger one. Given fleshy plants or polluted water, two stills should provide adequate drinking water for one person for an indefinite period.

If rain falls, your plastic cone will naturally capture it. It may capture other things, too. In the desert, water always attracts animals, and the air force colonel’s team found that “many small rodents and snakes become trapped in the middle of the plastic”—unable to escape over its slick surface. If you’re hungry these poor little bastards are obviously going to end up in your gut. (For thoughts on rattlesnake steak, see this page.) And even if you don’t feel hungry, remember that the animals contain precious fluids.

A word of warning: it occurs to me that the quoted yields of water were achieved by men practiced in the technique and operating with minds and bodies in good shape. Don’t underestimate the possible effects of weakness and irrationality (this page). But you can take care of the technique problem by personal experimentation. (If you experiment, make sure you fill the holes afterward.)

I’m ashamed to say that I’ve still not followed my own sage advice and given the rig a trial run. But the idea sounds to me like a practical proposition. A reader who had her Sunday School class of five-to-nine-year-olds build a still, guided only by my instructions in an earlier edition of this book, reports that the children constructed one, “completely on their own, in 1 hour 15 minutes…. And when the first drops of water began to collect and run down into the bucket, they jumped up and down yelling, ‘It works! It works! WE DID IT!’ ”

For car and airplane users, it seems to me, the components should henceforth be standard emergency equipment, kept stowed aboard against a nonrainy day.*19

CHIP: Having come of outdoor age in the deserts of Nevada and Utah, and on the Colorado Plateau, my instinct is to constantly search the landscape for sources of water. The discipline required is to always think about where water might be, whether you need it or not. Picture the way water drains, and follow the signs of surface runoff downhill. If water has left its mark—damp sand, ripple marks, dried mud—where has it gone? The two controlling variables are gravity and evaporation. I look for bedrock traps in washes and dry streambeds, or dig in shaded undercuts along banks. If there’s damp sand or gravel, you’re on the right track. The groundwater table is closest to the surface at the low points of the landscape and also along sharp changes in slope, like the base of a cliff or mesa or even a dune field. On exposed slopes, look for aquifers (water-bearing layers of porous rock or gravel), which show up as dark stripes or bands of vegetation. There may also be dark water stains or white evaporative crusts below. Following such a layer to a shaded alcove may reveal a seep or pool. It also pays to learn what local plants are indicators of water on or near the surface. In my part of the Earth, cottonwoods, willows, sedges, bulrushes, cattails, reeds, and mosses all attest to a possible drink.

At sunrise and sunset, scan for the flash of water. It’s not always where you’d expect. In Wyoming’s Killpecker Dunes there are large ponds of meltwater from snowbanks covered up by drifting sand. Even in the deep desert, there are water pockets in the tops of some rock formations, while joints and crevices collect runoff and sluice it into hidden pools—Utah’s Waterpocket Fold is the best-known instance, but most exposed formations have more “tanks” than you’d expect from a casual glance.

One tantalizing puzzle I encountered was a deep pocket with overhanging sides. It was 20 feet down to the water, and if I’d fallen in I’d never have gotten out. I had a 60-foot coil of parachute cord and a cookpot without a bail. I considered rigging a sling, but if my only pot fell out I’d have been in real trouble. I also pondered using a stuff sack with a rock in the bottom, but then my eyes lit on a sack of mesh. It fit nicely over the pot, a rig that even a dehydrated idiot could manage—and the fine mesh made a nice prefilter.

COLIN: On both California and Grand Canyon walks I had to establish several water caches. Glass bottles, I discovered, kept the water clear and fresh. Whenever possible I buried them—as protection against the hoofs of inquisitive wild burros and the fingers of other thirsty, thieving, or merely thoughtless mammals.*20

Unburied bottles are liable to crack from extreme heat (if you leave them in the sun) or from extreme cold (wherever you put them, if temperatures fall low enough for the water to freeze solid). I worried a good deal about the freezing danger in Grand Canyon, but found the unburied bottles at both caches intact, in spite of night temperatures several degrees below freezing. The bigger the bottles you use, the less danger that they’ll freeze solid. One-gallon jugs, thoroughly washed, are good; 5-gallon bottles, though cumbersome, are better. Plastic bottles such as those used for liquid bleach or for distilled or spring water are lighter and perhaps stronger, but I’ve recently had some perforated by thirsty rodents. Big, strong plastic jerry cans (Igloo, Rubbermaid, etc.) used for river trips and car camping should be much safer.

Water left for even a few weeks in 5-gallon metal cans seems to take on a greenish tinge, apparently from algae, but can still be drunk with complete safety. And these 5-gallon cans are light and strong, and easily lashed to a packframe when caches have to be made on foot. Twice in the Grand Canyon I used 5-gallon cans in which my food had been stored (this page) to pack water a half day ahead and so break a long waterless trek into two much safer segments.

In buying canteens, take no chances. If you find one is leaking badly, miles from the nearest desert spring, it may well be about the last thing you ever find.

Metal canteens, which I used for years, are, for backpackers, essentially things of the past. But there is one feature of metal canteens that plastic cannot match. If metal canteens with felt jackets are wetted and put out in the sun, evaporation from the felt soon cools the water. You can rig a makeshift jacket for a plastic canteen with almost any article of wet-table clothing, but because plastic is a poor conductor of heat the cooling system doesn’t work very efficiently.

Today’s bottles, of various plastics, are far lighter and cheaper—and in many ways tougher. On the score of toughness, metal naturally impresses you with greater immediate confidence. But on my Grand Canyon trip the felt covers of both my metal canteens developed gaping holes, and when the canteens came on side trips—slung from my belt by their convenient little spring clips—the bared aluminum banged against rocks and developed seep holes. I fixed the leaks with rubber air-mattress patches—but my confidence had been punctured too. The polyethylene canteens I also carried on that trip showed no sign of wear, and since that time I’ve used only plastic canteens. They’ve proved astonishingly tough. Once, at a “dry camp” on a steep hillside, a full 1-quart plastic canteen holding my entire overnight supply tumbled more than 100 vertical feet down a steep but nonrocky canyon. It went in big bounces, emitting a dull, heart-rending thud at each contact. But I found it, lying in a dry watercourse, safe and sound.

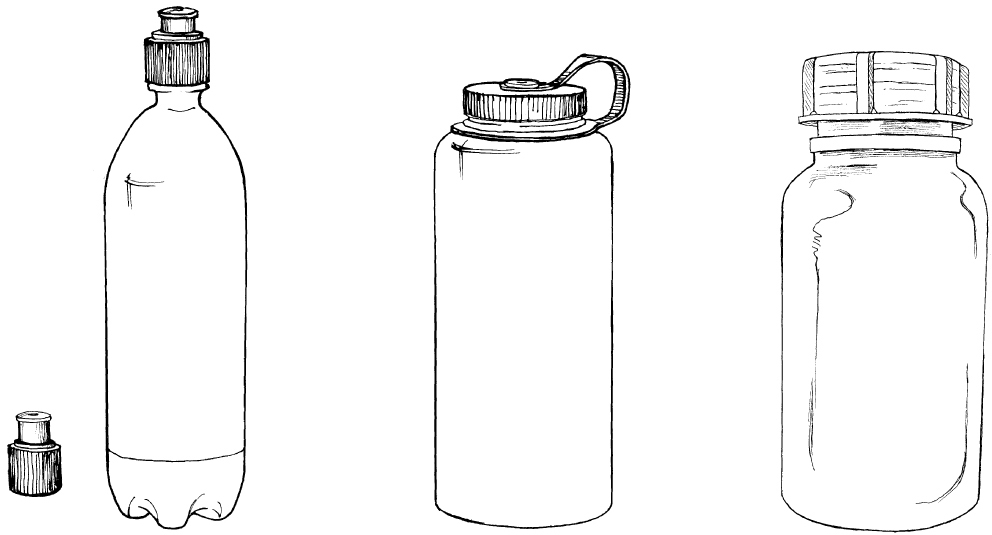

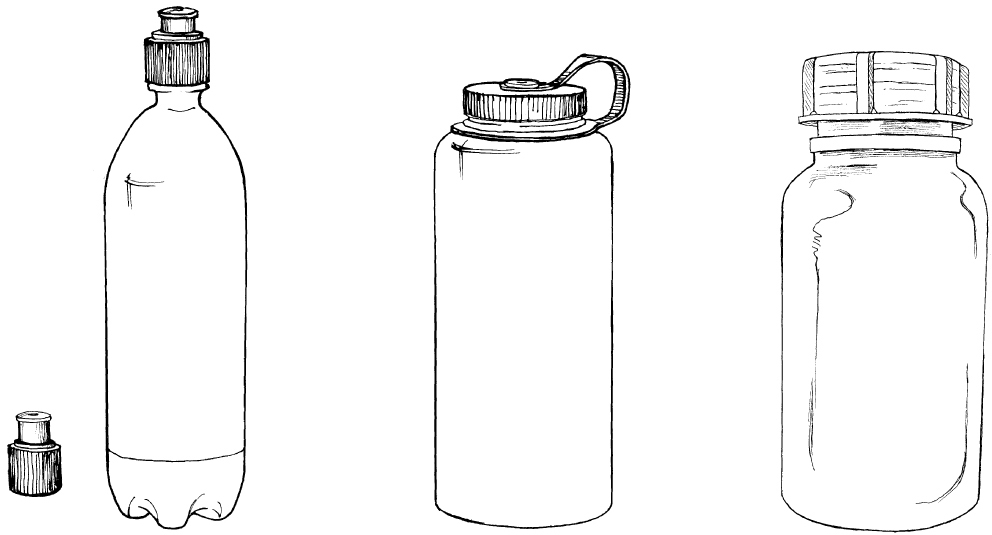

CHIP: For years I’ve used clear plastic soda bottles—the kind that contain anything from cola to mineral water. Having been sternly lectured in backpacking shops that the dire consequence of having one fail makes it mandatory to buy “real” water bottles at $6-plus a crack, I must respond with one well-chosen compound word. Soda bottles come in a range of convenient sizes, up to 2 liters, and various colors. Since high summer inspires in me a lust for gin and limes, my present standard is the 1-liter Schweppes Tonic. For testing, I randomly picked one out of my recycling bin, fitted it with a push-pull mouthpiece, filled it with water, and began to drop it from 90 inches—as high as my arm can reach. I dropped it 10 times on turf, 10 times on rocky soil, 10 times on boulders—not a single leak. So I started tossing it up in a spin and letting it come down on a concrete sidewalk, thwap! Twenty times. About every third thwap, the impact forced a small spurt from the mouthpiece, but it didn’t leak. After that, I climbed a tree and pitched the bottle down onto the sidewalk a few times—the lobes on the bottom crunched up and the mouthpiece looked as if it had been chewed by a badger, but no leakee. So I filled the poor thing to the top and left it out overnight to freeze hard. Again, some water oozed out of the mouthpiece, but the bottle—battered, buffeted, and iced—proved steadfast.

By dint of relentless abuse, I found that the cap is the most vulnerable part: mouthpieces can be forced open by impact or freezing, and plain caps will crack if struck at just the wrong angle (a few turns of duct tape can shockproof them). But if I’m fool enough to drop my water bottle repeatedly on the cap, then I deserve to die. And in that sad event, the bottle can at least be recycled into a fleece pullover.

Meanwhile, I tried the same series of drop tests with a $6 Lexan bottle. Thicker and more rigid, it held up as far as not leaking, but rocks gouged the rigid Lexan deeply enough (in the same way that aluminum canteens can be gouged) to worry me.

The metal vessel is not dead, however. Sigg, Markill, and other European companies make elegant aircraft aluminum bottles with interior coatings that resist the acids in drink mixes, juice, wilderness lakes, etc. These weigh about an ounce less than widemouth Lexan bottles of the same size (the 1-liter Markill weighs 5 oz.) and cost roughly twice as much (the 1-liter Sigg is $13). Both companies offer insulating sacks, but for evaporative cooling, make your own cover from the sleeve of a cast-off cotton knit shirt.

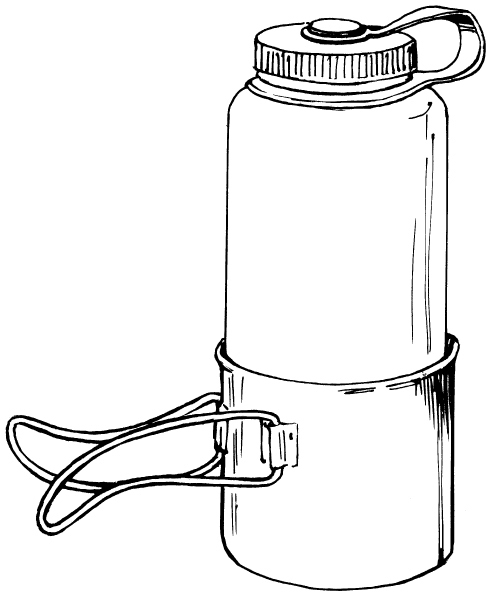

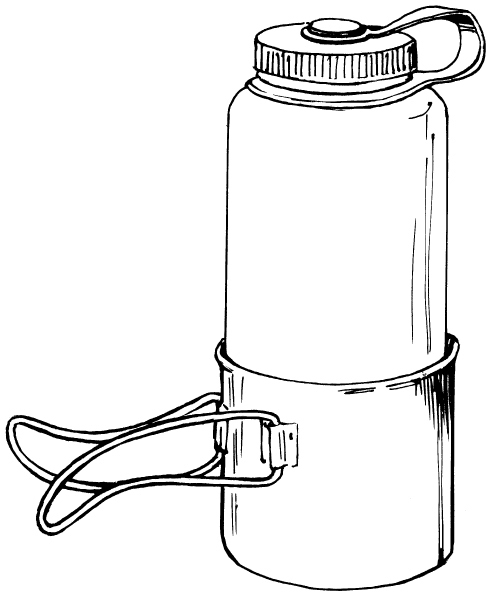

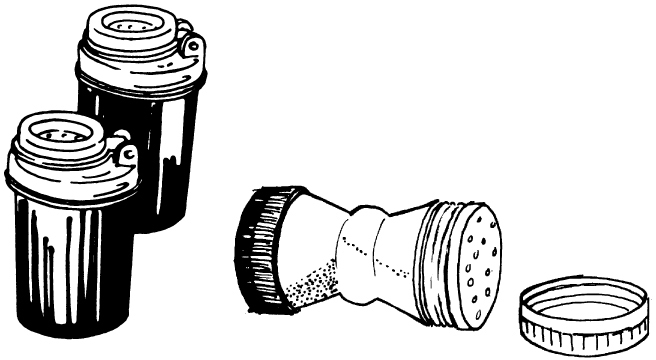

Most made-for-backpacking bottles come in translucent polyethylene (high or low density) or transparent Lexan. The Nalgene catalog has a handy reference chart on which material does what, as well as cautionary notes (don’t carry chlorine bleach, which makes plastic bottles leak). Polyethylene bottles get brittle with age and/or UV light: check them by flexing and look for hairline cracks. When buying a new bottle, look for refinements such as undroppable loop tops and measuring marks. If you have a water filter, then your bottle should fit the threads. Some makers pick a thread that matches only their products, forsaking all others. The closest thing to a standard is the 63-millimeter-wide mouth. I have a Nalgene widemouth of polyethylene—snatched from the water-quality lab I ran for years and converted (with Reflectix insulation and duct tape) for winter use—and a second one (repeatedly boinked in the torture test above) that came with a First Need purifier. Hunersdorf widemouth bottles (facing page, right), of lab-quality polyethylene with ribbed, easy-open caps, in sizes from 50 milliliters to 1.5 liters, are also favorites for their ruggedness and imperviousness to tastes and odors.

The faceted, polyethylene bottle with a loop top that Colin once favored (he’s now gone Nalgene) can be had in four sizes (1 pint, 1.5 pints, 1 quart, 1.5 quarts, at $2–$6) from most backpacking shops. The loop has been strengthened so the bottle can be safely hung thereby. But, unless you’re on a hanging bivouac, it shouldn’t be.

COLIN: I long ago rejected the traditional idea that in thirsty country you carried a canteen clipped outside your pack, readily available: thirsty country almost always means sunny country, and direct sunlight soon turns even cold spring water into a hot and unquenching brew. In thirsty country I carry my canteen near the top of the pack but insulated under a down or pile jacket. In any case, a canteen clipped outside your pack, especially if swinging loose, is pretty sure to be a poorly placed load. Unless weight is a real problem I mostly carry four 1-quart canteens. Even when I don’t expect to carry as much as a gallon for safety purposes, I feel it’s worth the extra freedom they give me, at 3 or maybe 4 ounces a shot: I can camp well away from water and, unless it’s very hot, stay for 24 hours without a refill.

Water bottles make tolerably comfortable pillows, especially if padded with clothing. Bladders, too. In weather no worse than cool, the pillow routine also keeps the stopper from freezing (and for an infuriating minor frustration few things equal waking up thirsty in the middle of the night and finding yourself iced off from your drinking water). Simply putting the canteens on air mattress or foam pad may be enough to keep the stopper ice-free, but in really cold weather take one canteen to bed with you. If you think there’s any danger at all of the others freezing solid, make sure they’re no more than three-quarters full. That way, they can hardly burst.

No matter how many large canteens I take, I now nearly always add an Evenflo baby-feeder bottle (.5 pint capacity; 1 oz., $.73). It does more than boost my carrying capacity. In hot weather, particularly if walking along a riverbank or lakeshore where the water is suspect, I often fill it at every halt, add a Potable Aqua tablet, and slip it into a pack pocket. At the next halt I have, immediately available, just enough safe water to see me through another hot, dry hour. In the desert I’ve found such a bottle invaluable for collecting water from shallow rain pockets, and I’ve often been glad to have it for collecting water from other small sources. At a pinch, you can even use one for rescuing a little water from seeps that no ordinary canteen will even begin to tap; but for a better alternative see this page. Baby bottles are also convenient for short side trips; one will slip into your pants pocket—though it can also slip out. These little bottles are tough too. Once, when mine held my last precious half pint of water and I dropped it on a boulder, it bounced quite beautifully. Warning: The two-piece lid (for fitting baby’s rubber nipple) is a mild nuisance. To hold it in one piece and so prevent the inner disk from dropping off every time you remove the lid, just slap a piece of tape on top. Renew it occasionally. The tape will allow the disk to turn a fraction when you replace the lid, and so jam into a watertight joint—provided you keep the rubber nipple in place. Know ye that without the inner disk—or the nipple—the damned thing will leak.

True, the bottle/filter combinations (this page) now let you do most of the baby bottle’s jobs; but I’m still a fan. Second childhood, you say?

CHIP: My experience with bladders (except, of course, my own) is limited. But Linda adopted the drinking-bladder-and-tube setup at the first glance. And she remains a proponent of the Hydration Way: suck as you go. I have an odd resistance to it—the vision of overaged infants snoozling away with tubes in their mouths doesn’t sit well. But there are sound physiological reasons for downing small amounts of water on a frequent basis, rather than taking huge, infrequent gulps, and equally sound ones for staying well hydrated. Sports physiologists claim that you’re more subject to stress injuries when your body is short on H2O. Another plus is sheer efficiency: you can hold a steady pace and sip without a stop. In bug-pestered areas, being able to drink without halting is a distinct advantage. Given all that, I might grow accustomed, sooner or later.

Platypus Thunderhead

Bladder

Meanwhile, I tried a Platypus Thunderhead that combines a slim day pack and a 3-liter bladder (1 lb., $75) while exploring an obscure range of mountains in the Mojave Desert. Days touched the 90°F range: hot but not killing. From a base camp with access to a spring, I chose a different canyon each day, approaching up sandy washes and climbing steep streambeds choked with boulders and prickly brush, past fantastic alcoves with signs of desert bighorn sheep (though I saw not one).*21