Furniture and Appliances

No matter how grimly you pare away at the half ounces you always seem to burden your house with an astonishing clutter of furniture and appliances. At least, I do. Each item, of course, is a necessary aid to some necessary activity. For example, there’s the vital matter of

SEEING.

To lighten your darkness you almost always need to carry a small, lightweight

and you now have a wild and plastic selection to choose from: a flock of handheld models and a growing number of practical headlamps.

CHIP: Both hand- and head-held lights are changing fast, with leaps in the design of batteries and bulbs. Since there’s determined competition for the favor of backpackers, you’re ever more likely to find a light that suits you. Meanwhile, two classics survive.

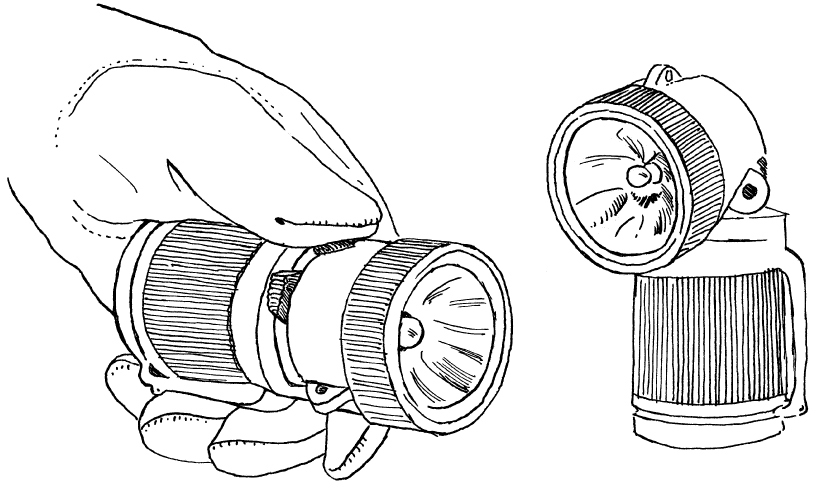

The old, angular plastic Mallory still lives in many pack pockets, with the current model being sold as the Durabeam DFC Compact (empty, 1.5 oz.; with two alkaline AA batteries, 3 oz.; all told, $7). It’s bright, but not waterproof, with a tapered grip that fits into some elastic and Velcro headbands, for handsfree operation. The Durabeam light costs little and will last for decades—I have a tooth-marked 1970s survivor in my glove box.

Durabeam flashlight

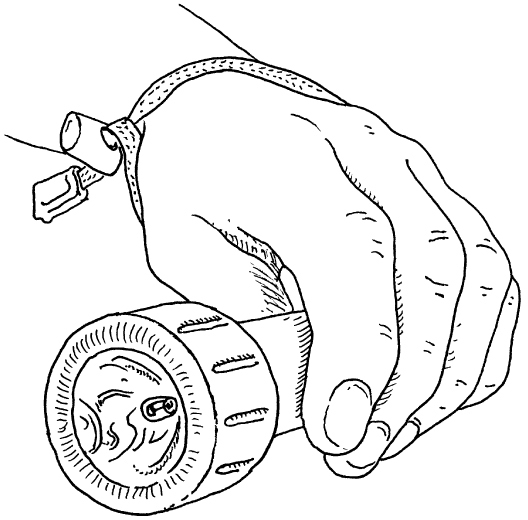

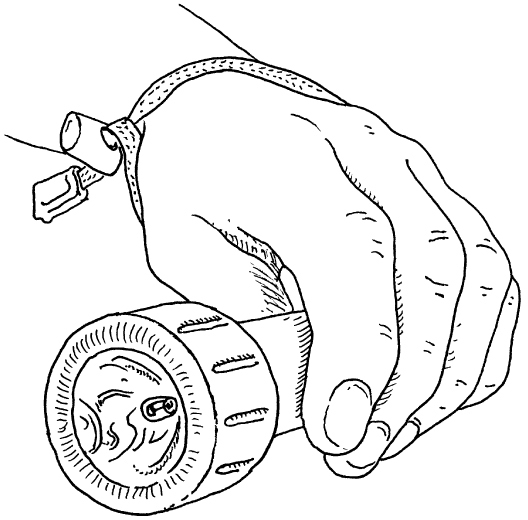

The other classic is the Mini Maglite (with two AA cells, 4.1 oz., $14.50).*1 Machined not of magnesium but of aluminum (Alulite just doesn’t have that same ring, I guess), these are nearly indestructible. The key feature is a machined thread sealed by a rubber O-ring (water-resistant rather than -proof) that not only switches the light on but focuses the beam, from a diffused flood to a tight, brilliant spot. A semikey feature is a selection of anodized jewel-toned cases. Linda’s Mini Maglite (red) is a 1980s model and, with a couple of cleanings and one new bulb, it shines on dependably. The reason I didn’t adopt one was that at low temperatures—repairing a stove, etc.—I’d get a headache from holding what amounted to a metallic cigar between my teeth. But there’s now an astonishing range of accessories for the Mini Maglite: headbands, holsters, wrist straps, belt clips, and, yes, plastic bite sockets. The Maglite Solitaire (with one AAA cell, 2 oz., $9.50) is popular for ounce paring. Extra-bright bulbs can be had ($5) if you don’t mind their battery-gulping habits.

Mini Maglite with hand

Maglite-style switches that work by rotating the bezel (beh’-zel: the front part that houses the lens, reflector, and bulb) on a molded set of threads are the overwhelming choice these days. They’re mechanically simple—you literally screw the bulb down into contact with the batteries. They’re easy to waterproof with a rubber O-ring. But switching one on is a two-handed operation. You can accomplish it single-handedly by gripping the barrel of the light with three fingers while rotating the bezel with forefinger and thumb, though this takes practice. But—if you ease the procedure by keeping the switch/bezel near the turn-on point, the light can light up inside your pack. This happens not just from rotation but also pressure. When you take the light out the pressure is relieved and it will be off. To check, turn the bezel until the light goes off, then press down on it. Many rotary-thread models will come on for up to a half turn (180 degrees) past the apparent off-point. If your light relentlessly and mysteriously devours batteries, this might be your problem (see this page).

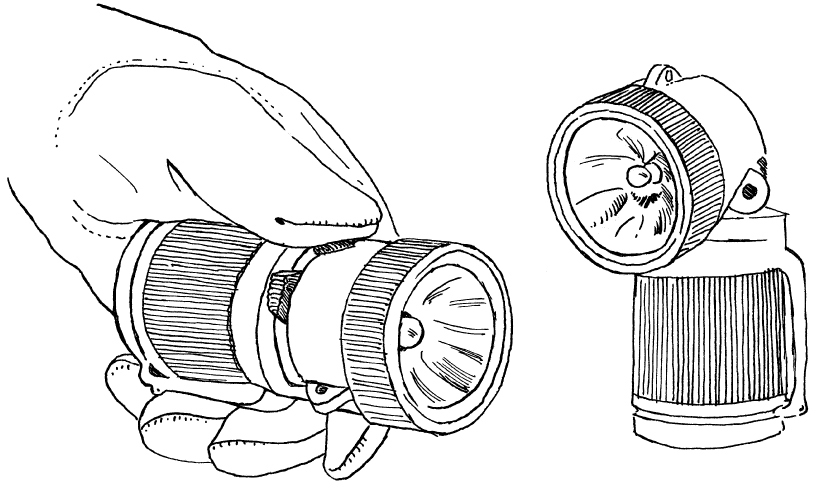

Eveready Sport light

Sorting the current crop of flashlights by type—and sticking for the most part to lightweight models—let’s start with some that don’t have rotary-thread switches. Like the classic Mallory, the Eveready Sport Compact (with two AA cells, 4.5 oz., $6) has a rectangular reflector, but it’s waterproof (and floats). The switch is a unidextrous push button clad in soft plastic; the case has molded ridges for grip; the lens is shatterproof; and there’s a lanyard.

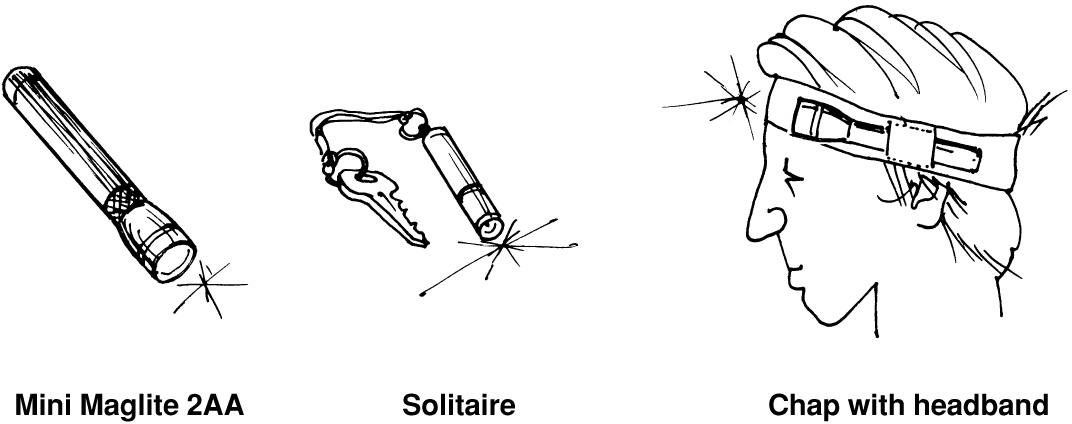

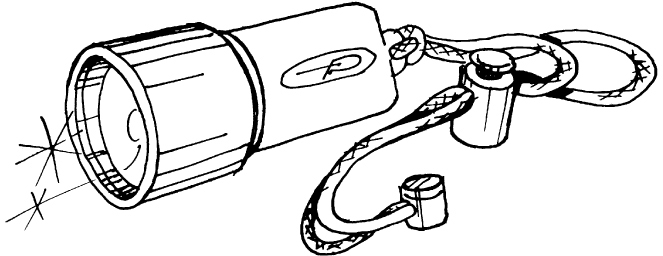

The following, unless noted, are all rotary-switch types that have been used for backpacking with some success. Pelican makes a series of handheld lights, flagshipped by the popular MityLite (two AAA cells, 1.7 oz., $13). Rated as waterproof to 2000 feet, it boasts a xenon seed bulb and dioptic reflector that throws a sharply focused beam. Also xenon-lamped and H2O-proof with a longer burn time is the Pelican Magnum (two AA cells, 4 oz., $17). It has a plastic “shirt clip” that works on the bill of a cap, to free up your hands for cooking, fixing, and groping.

Princeton Tec 20

Princeton Tec, originally a maker of scuba divers’ lights, now offers impressively waterproof and exceptionally rugged handheld models with noncorroding metal parts—the two-AA version is called the Tec 20 (3.2 oz. with batteries, $14). Princeton Tec is in New Jersey—near sea level—and when you first open the battery compartments of these lights at high elevations there’s a distinct whoosh, which means the O-rings are good. With batteries side by side in a flat-oval cross section, the Tec 20 fits the hand nicely and also slides into most headbands, belt clips, etc.

Another compact light recommended by readers is the Streamlight Scorpion (4.4 oz.; $60 with batteries, $50 without) that runs on two 3-volt lithium cells (sold for auto-wind cameras, and hence widely available). It has a rubber-clad aluminum body and, if wallet chomping, is also bright and long-lived: a perfectionist’s flashlight.

Streamlight Scorpion

A recent and well-thought-out contender is the Bison Sportslight 2AA (3.4 oz., $15), a polymer-cased handlight with a click (rather than screw-thread) rotary switch. The focusing reflector is shaped to avoid bull’s-eye voids without stippling or diffusion. Two teeny bi-pin bulbs (that connect with two stiff wires) are supplied, one a high-power xenon type, with the spare nested in a semi-obscure internal cavity. The bulb change should not be done by feel in the dark, nor after encounters with John Barleycorn, Lord Ganja, or other fumble inducers. The original Bison 2C model (7 oz., $20) slings as much light as those long-barreled aluminoid cop flashers, but with better ergonomics (unless you want to club demonstrators, that is). Bison also makes a better-than-average stretch wrist-loop and belt-clip combo ($5).

Bison 2AA

Discount-store racks have a surprising number of blister-packed two-AA flashlights with rotary-thread switches, claimed to be waterproof or -resistant, for $3 to $5 with batteries. Their weak point seems to be rapid wear on the bezel/switch/O-ring seal, causing the light to flick off without warning when jogged, or not to turn on at all. Since the mechanism resembles that of the new LED lights, see below for fixits. If you’re scratching your head, “LED” is short for

a new and Fairy Godmotherish gift to backpackers—especially those of us who like to read at night. Unlike a bulb in which a metal filament is heated to incandescence, an LED gives off light without generating much heat. The device is made by combining a layer of semiconductor that has a small excess of electrons and a negative charge with a second layer that has electron vacancies called “holes” and a positive charge. When electron and hole meet, a photon bursts out: light. Each LED sandwich is mounted in transparent polycarbonate, which directs the light, and the resulting unit is (unlike bulbs) shock- and vibration-proof. This means extremely long life (10 or more years of continuous use) while needing only 10 to 20 percent of the power used by an incandescent bulb. The newest LED flashlights, with internal power-saving chips, can give hundreds of hours of useful light on a set of batteries. That’s the revolutionary part.

Now, the liabilities: relative dimness, fuzziness, short throw, and chilly looking hues, along with some odd special effects.

Some years ago, intrigued by the possibilities, I located a single yellow LED that was soldered into a standard brass bulb-base. On rechargeable nicads it glowed a full 24 hours but was too faint for walking at a normal pace. So I used it for tenting-up and reading during storms (dim lights, thick snow, and nature’s music). Recently, makers have bumped the brightness by teaming up better diodes in two-, three-, and four-LED arrays. But since the diodes themselves vary somewhat in hue, you might get a mix of bluish and yellowish haloes—a bother for reading.

Though costly (now) an LED array can save you tremendous weight and cost in batteries. A neat three-LED model in a standard 9-millimeter flange base that will drop into your favorite two- or three-cell light comes from Real Goods ($30). I tested one in a two-AA headlamp and had plenty of light for tent pitching, cooking, reading, and normal walking. After 38(!) hours the light was still bright enough for reading but too dim for confident walking. The batteries (Duracell alkaline) started fresh at 1.55 volts and ended at 1.36, so there was probably another three to four hours of useful light left. This means you can do a fairly long trip on one set of batteries. For average use—cooking and gear fiddling—you don’t need much light, but for route finding and rescues, you do. So a kit of standard and extra-bright bulbs is a wise (and lightweight) backup.

LEDs arrived in a flood of Chinese-made flashlights with the diodes soldered to a flat piece of circuit board. These seem to crap out in fairly short order, first flickering when bumped, then failing to light up. A lick with a pencil eraser or fingernail file on the contact point—a blob of solder under the circuit board—might get them working again. Another caveat is that LEDs have a voltage threshold and some won’t light up with even mildly depleted nicad rechargeables. In fact, many present LED configurations need three batteries (4.5 volts) to work right, so the flashlights are either long (7 inches) or wide. But not all.

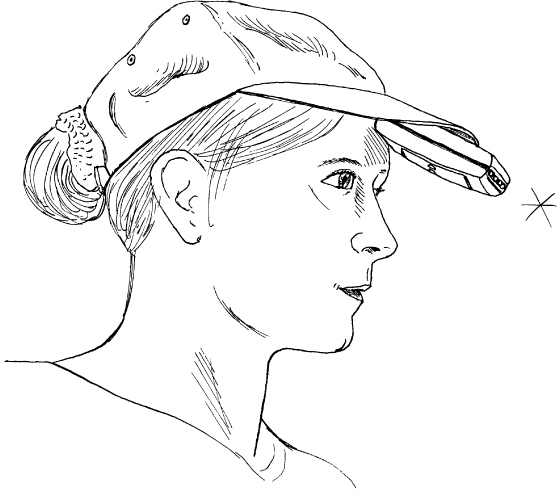

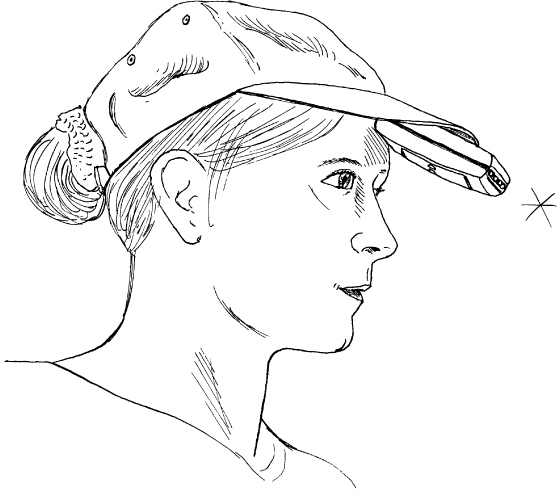

The lightest useful LED backpacking light is the C. Crane Lithium Trek Light (1.6 oz. with special 3.6-volt AA cell, $40). A mere 3.5 inches long, it has a three-LED array in a rotary-switch bezel. The 3.6-volt lithium Hawker Eternacell ($11) is rated for 50-plus hours—a very long trip or even a season—and it works in cold temperatures when alkaline cells flag and nicads are hopeless. I suggested that they include a black shield with the light as a standard item, since side glare is a problem. But as always, a wrap of duct tape works. A keen accessory is the light holder that clips to the waistband of your shorts or the lantern loop in your tent. But with careful microsawing and filing, a molded side slot on the Trek Light (ostensibly for a wrist loop) becomes a clip for a cap visor, giving you a strapless headlamp. In crash tests (I jumped out of a tree) it stayed on the cap, although the cap itself tended to fly off. The drawback with this system is that you can’t adjust the angle of the beam—for walking I unclip the light and hold it low. Anyhow, at roughly the same weight as a fast-dying penlight, the Lithium Trek is a welcome surprise for determined ounce parers.

Crane Lithium Trek Light and holder

Almost as light, with the option of rechargeable batteries, is the C. Crane Mini Trek Light (3 oz. with three AAA cells, $35) in the usual black and also easy-to-find yellow. The three batteries nest in a tricky triangle, so the light’s only 4 inches long, with a combination lanyard mount/bite tab and a sturdy clip for the bill of a cap—the necessary lens shield comes with it.

Brightest of the stick-type LED flashlights I tested, the Lightwave 2000 (4.5 oz. with three AA cells, $30), has a four-LED array. It also has a chip to keep the power level constant and prevent overdriving the LEDs (which accounts for the bright and dim phases of unchipped models). The chip allows three alkaline cells to yield 300 to 400 hours of illumination (I left it on for a week—168 hours—and finally got tired of checking it). The case has grip grooves, and the black bezel doesn’t need a light shield. Like other lights of this sort, it’s water-resistant, not -proof. The importer, LED-Lite of California, also handles a curiouser item, called the EternaLight.

Although lights play a role in entertainment they usually aren’t the whole of it. But the EternaLight is entertaining as hell. In fact, you should be wary of lending it to impressionable tentmates, who will sit up late playing with it. Designed by Wayne Gregory, of I-frame fame, the EternaLight (4.3 oz. with three AA lithium cells, $80) has four LEDs. I tested the marine model that’s watertight to 100 feet, floats (with lithium cells), and is bright enough to be useful. But the interesting part is the 18-prong internal chip, controlled by three push buttons. ON/OFF does what it says. MODE switches seven ways, between timer (a 10-minute dimming to shutoff), on/dim (10 power levels, from 100 percent giving 50 hours to 6 percent giving 785 hours), flasher (all LEDs blink), strobe (adjustable speed), dazzle (LEDs wink in an attention-getting pattern), SOS (the Morse code signal), and pulse (for other signaling). The third button, RATE, controls both the power levels and the speed of the special effects. The prototype had a few glitches—foam padding that stuck to the batteries and tiny screws that fell out—and after a hearty cougar scream, I ended up stroking the rug with a magnet. When I called LED-Lite with feedback (“already changed,” they said), they promised weirder and better things in the near future, including bike mounts and a headlamp. For the present, they have a nice forest-green ball cap (2 oz., $20) with Velcro loops under the bill, and a strip of hook tape for the EternaLight, making it a viable headlamp. Crash tests (jumping out of that tree again) revealed that while the light remains firmly attached to the cap, the cap—weight tripled by the light—may depart the head. In any event, I scampered out and bought an extra length of 2-inch Velcro tape for my bike helmet and am pondering other sticking points.

EternaLight

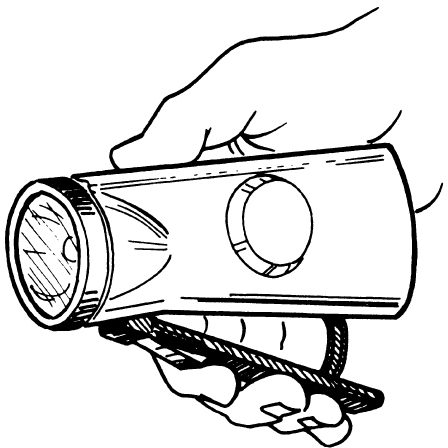

The business end of the Streamlight Syclone (7.6 oz., $30) pivots—fans of the old army right-angle flashlights will find it a much-improved update. A four-AA model, the Syclone mounts a bright krypton bi-pin bulb (see this page) and a single amber LED. On alkaline cells, the krypton bulb burns for 3.5 hours and the LED (for reading, fumbling, and careful walking) for 72. Rugged, waterproof, and only 4¾ inches long, the Syclone has a strong, rotating belt clip and a top-mounted hanger hole, so light can be directed at any angle.

Streamlight Syclone

Another swivel-headed model is Pelican’s VersaBrite (5 oz. with two AA cells, $19) that mounts a bright and focused xenon bulb. Burn time is 5 to 6 hours. With an array of clips and slots, the polycarbonate body attaches to pockets, visors, straps, and, via the Velcro tape included, to other loopy surfaces (Chesapeake Bay retrievers). There’s also a magnetic mount—of limited use to backpackers, unless you have a steel plate in your head.

Pelican VersaBrite

The Streamlight WOW (5.4 oz. with two AA cells, $14) straddles the gap between flashlight and headlamp, with a pair of battery-holding legs that close to form a rubberized handgrip, or spread wide to encircle your brow. In like fashion, the elastic wrist lanyard becomes—voilà!—a headstrap. The lamp assembly, with a pebbled reflector and rotary switch, swivels 80 degrees up or down in either mode. The WOW light gives me mixed emotions: it looks like a gimcrack but turns out to be a somewhat bulky but really pretty good light (for the gadget lover, at least).

Streamlight WOW

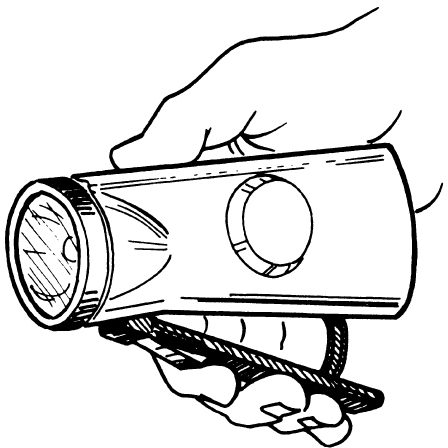

COLIN: Dynamo lights—which I remember as popular in the Netherlands during World War II—are interesting and economical alternatives to battery-powered flashlights: you squeeze a handle slowly and rhythmically and generate a steady light. Dropping one of these gizmos in water apparently does no damage, the handle locks away for packing, and a spare bulb sits tucked in behind the reflector. The sturdy kind of model you need (avoid flimsy lightweight versions) weighs 8 ounces; but remember you need carry no spare batteries. And although I don’t dote on the whirring noise it makes, and am underwhelmed at the thought of having to keep squeezing it for camp chores, I purr at having a surefire backup. I’ve used it occasionally, and with reasonable success, for following a trail at night. Real Goods still sells the kind I use (8 oz., $13), and sometimes stocks, primarily for kids, a clear plastic version ($14) that needs assembling but then—wait for it—lets you watch the wheels whir.

Dynamo light

Many backpackers—and especially snow campers—favor

over hand-held models, even though they tend to be heavier. You always have both hands free—for erecting a tent, cooking, and every other chore or delight. (Along this line, a Rhode Island reader recommends, for setting up camp after dark, taping your flashlight to your knife and sticking it in a tree.)

Headlamps come in two conformations: those with the whole unit, including batteries, up on the headstrap—thereby eliminating troublesome cords but putting more weight on the head and sometimes inducing headaches, especially if you walk at night; and those with only a light bulb-and-lens unit on the headstrap and a separate battery unit, often with a built-in additional light, that can clip on clothing, travel in a pocket, or even stand alone—thereby necessitating a cord but holding headaches at bay and also keeping the batteries warm (often an important matter with all but lithium cells, as anyone who has dropped a flashlight in snow will attest).

CHIP: By the light of a flailing beam I’ve done things I might well have regretted: skiing out of high peaks in the December dark over snow-covered granite, with sparks spraying from the edges of my skis. For such tricks, a headlamp is mandatory (and a headache optional).

The first one I used was a Justrite Head Lantern, a steel-bezelled biggie with a lamp cord leading to a hinged steel case and four D cells (weight: a ton). Fatigued by our heroics, we forest-fire fighters often forgot to return them. In latter days, Justrite updated the beast with a polypropylene battery case and a focusing beam (1 lb. 11 oz. with four D cells, $36.50, Forestry Suppliers). About that time there were all-plastic headlamps around with basic electrical problems, odd features, and underpants-quality headstraps. Some weren’t bad—Linda has a four-AA Panasonic that continues to work. I used a French Wonder Light with three brow-mounted AAs and a rotary switch, which tended to short out in rainstorms. And when I hit bumps on skis, the weight of the batteries converted it to a blindfold. So I rewired it to run off a lantern cell stowed in the top pocket of my pack. But one night when I abruptly shed my pack, the thing flew off my head and was terminally impaired by a rock.

At that point, Chouinard Equipment began selling the industrial Hartford Headlite (13.4 oz. with four AA cells, $21.50, Forestry Suppliers) of unbreakable plastic with a hole-punched rubber strap and a D-battery holder astern. With the newly available lithium D cell and matching bulb, it was the best thing going. But it was heavy and bulky, and the rear battery holder was uncomfortable for tent-bound reading. So when I saw the Petzl Micro, I pounced.

Petzl Micro headlamp

The Petzl Micro (5.2 oz. with two AA cells; $24) is a sweetly functional backpacking headlamp (though not waterproof) with a rotary bezel switch on a swiveling head, and a top strap to hold it aloft. The soft-rubber battery cover tucks a spare bulb in. It was my standby for half a decade.

Hard-core types prefer the Petzl Zoom (9 oz. with battery, $35). The flat 4.5-volt battery costs $7, for 17 hours of really bright light. An optional halogen bulb throws a 300-foot beam but cuts battery life to 6 or 7 hours. A three-AA adapter costs $5 and gives 8 to 9 hours on a krypton bulb, 3 hours on halogen—but you can also use lithium cells for longer burn time and cold conditions. C. Crane Co. sells the Petzl Zoom for $40 with a special screw-in LED array ($20 alone) that gives 35 to 40 hours of bright light and 20-plus hours of diminished output. The Crane package includes a regular krypton bulb, plus the AA adapter. Demerits: the Zoom’s rear-mounted battery pack is trying if you like to read with your head propped, as I do; and for backpacking it might simply be overkill. Still more so is the NiteRider series of digitally controlled headlamps, sophisticated artifacts that start at $100-plus and rise steeply.

Petzl Zoom headlamp w/adapter, LED array

Princeton Tec Solo headlamp

My current love-pet is the Princeton Tec Solo (5.5 oz. with two AA cells, $28) with the same good points as the Petzl Micro, as well as waterproof (to 2000 feet) lamp and battery cases and an easier bulb change. The Solo comes with two reflectors, a tight-beam one and a stippled one that eliminates the bull’s-eye (for reading and contemplation). It also comes with two bulbs, krypton (8 hours) and halogen (2 hours), and is packed in a fleece pouch to prevent lens scratches. Now that 1.5-volt lithium AA cells (with four to five times the capacity per oz. of alkaline cells) are widely available, two-AA lamps like the Solo are nicely feasible for deep-freeze weather.

So I asked the Princeton Techies when they planned to scoop the market with an LED headlamp. Enter the Matrix (basically a Princeton Tec Solo in silver gray, 5.8 oz., $40) with a three-LED array in a plastic mount that replaces the conventional reflector/bulb assembly. It burns 40 hours on two AA alkaline cells, meaning that you can do a week’s trip on a single set. The LED assembly ($30 alone) fits only Princeton Tec lights. I use it for general fumbling while keeping a spare lamp unit (a reflector/base, a spring, and a krypton bulb, included) ready to go. The changeover to tight, bright beam takes—I just timed it—18 seconds. There’s a little guide groove that makes it impossible to goof up. Of course, it helps to practice the lamp change in the dark, standing up, lying down, and also to rehearse swapping batteries—in a tight situation, it’s well worth the effort.

If you bash around in the dark enough to need a bright, focusing beam, another good two-AA model is the new Bison Headlamp (5.1 oz., $25). It boasts the same polymer body, battery-saving bi-pin bulb, and void-free reflector as other Bison lights. In Rimrock Purple and Aspen Yellow, it verges on fashion—without compromising function. The brightness and phenomenal throw of the beam compare favorably with much heavier lights such as the Petzl Zoom.

Bison headlamp

There are further dozens of perfectly good two-AA headlamps with top straps and other desirable features: the L. L. Bean Lightsource (5 oz. with two AA batteries, $29) has an optional recharging kit with two nickel-metal hydride batteries and a 110-volt charger that plugs directly into the headlamp ($20). There are also decent two-AA headlamps in the $12 to $15 range, like the Panasonic Taskmaster (8 oz., $13). Below $10, they tend to be cranky and short-lived.

L. L. Bean Lightsource headlamp

I’ve spent much of my adult life unplugged, with kerosene lamps and candles; for some years I even swore off flashlights, learning to negotiate the steep trail to the cabin where I lived in full, leafy dark. So I’m happy with less light than most folks. On the other hand, if you require 100-watt reading lamps and shudder between streetlights, then by all means use halogen or xenon bulbs and pack more batteries. That way you can fully illuminate your freeze-fried satay and also scan the woods for Lurking Presences.

Though, for the most part, the only Lurking Presence will be you.

COLIN: Naturally, you must always know exactly where your light is. During the day mine used to go into the inside pocket of the pack, where it was reasonably well protected and tolerably accessible. But my present pack has no inside pocket, and for some years the flashlight has traveled without damage in an upper outside pocket, protected by scarf or balaclava. For storage at night, see this page.

CHIP: The time to put your light in order is somewhat before dark—if it doesn’t work you’ll have ample time to tinker. First, check the position of the switch. Slide switches and push buttons can turn on while being stuffed. Of course you can stuff the light so the switch is always pushed in the off direction. Or you can tape the switch down. The easiest way is to stick fresh tape to the body of the flashlight, with the tail extending a good 1 to 2 inches past the switch, then tab the last ¼ inch over so you’ll have something to grab. New trip, new tape. For problem push buttons, keep your light on top of the load or devise some guard, like a scrap of cardboard tubing or PVC pipe. Rotary bezels can be foiled by pressure—this page.

Putting a scrap of cardboard between a battery and contact point can prevent drainage, if the battery compartment opens easily. Reversing one cell can apparently damage batteries. Reversing all the batteries has no effect: the bulb still goes on. On new LED lights with battery-saving chips, reversing cells can ruin the chip.

Besides accidental turn-ons, another problem might be bad contact: try lightly scouring the batteries and the internal contacts with a pencil eraser or some other mild abrasive. Cleaning with alcohol (not beer) can remove scum. Moisture is another culprit. Swabbing with dry cloth or paper, or a cautious pass near (not directly above) a stove burner, can dry things out.

If none of that works, try the spare bulb. (If you don’t have a spare, you deserve to suffer.) The chance that both bulbs will be bad is infinitesimal. For critical trips, new bulbs are not an unreasonable investment.

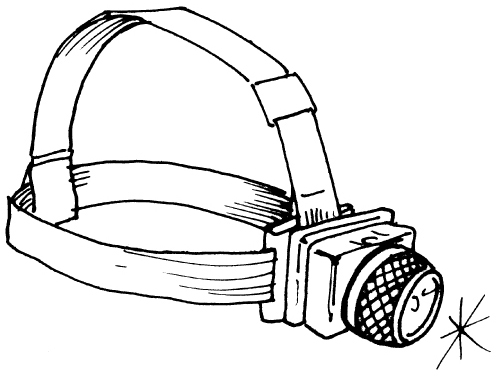

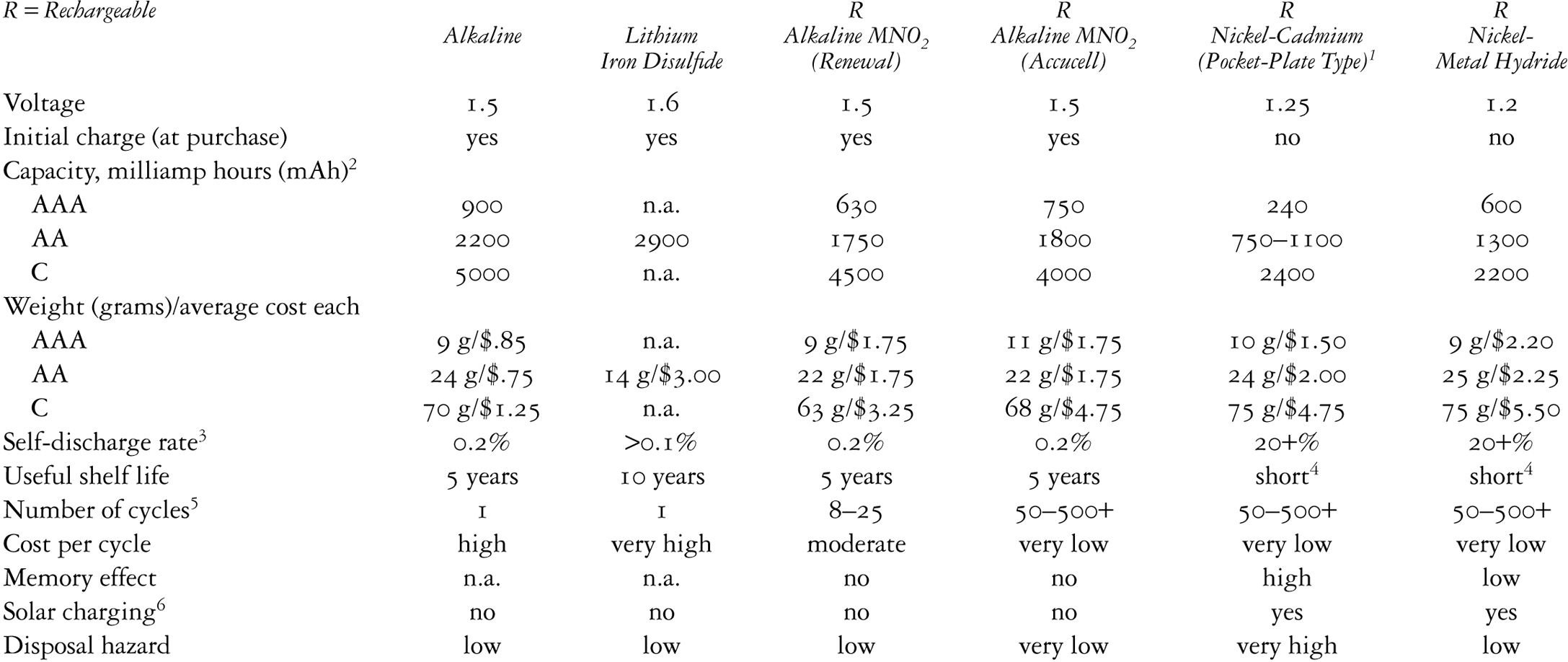

Throwaway alkaline cells are now the choice of most backpackers. But the light weight, high power, cold-resistance, and long shelf life of lithium cells—newly available in the AA size—have made them semi-competitive.

The real contest now is throwaways versus rechargeables. Rechargeable nickel-cadmium cells have been around for a long time, mostly disdained by backpackers for their short life (though I use them—this page). New rechargeable alkaline cells are gaining ground, and nickel-metal hydride (NiMH) cells also show promise.

Electricity being invisible, mostly, it’s tough to sort out all the whats and wherefores. So for a table on the batteries most used by backpackers, compiled from various sources, including catalogs, manufacturers’ Web sites, and consumer ratings, see this page.*2

To follow up on the table, we should brush through how each type of battery performs for backpacking. Which, for me at least, doesn’t include cell phones, portable CD players, or GPS receivers. We’ll look first at non-rechargeable cells.

Carbon-zinc cells have a carbon anode (+) surrounded by ammonium chloride paste (the electrolyte) with a zinc shell, the cathode (–). A chemical reaction causes electrons to flow, thus converting chemical energy directly to electrical energy. This is the magic all batteries do, in various ways. If the chemical reaction is reversible, then the battery can be recharged. But carbon-zinc cells can’t be. Long the mainstay, they have now been supplanted by

Disposable alkaline cells, introduced in 1958. With a higher potential storage, they caught on, but because of their mercury content, multiplied by the sheer volume of batteries tossed out, they were soon recognized as an environmental problem. The late 1980s saw low-mercury alkaline cells, and since 1990 alkaline manganese dioxide cells (the popular Duracells, Energizers, and Rayovacs) have been mercury-free. Even so, they are discarded in such immense quantity (now 2 billion per year in the U.S.) that they still constitute toxic waste. Though the makers discourage it, it has long been known that these cells can be recharged, sort of. But they also might heat up and vent (i.e., blow up). If they’re only partly discharged, the new microchip-controlled chargers can pump them up for a few cycles, with diminishing capacity. So, despite their popularity, they’re expensive for the power you get, and given the drop-off in cold weather, far from ideal.

1New high-capacity AA nicads are rated at 1000 to 1100 mAh. 2The differing internal chemistry of the batteries listed makes mAh values hard to compare—most makers rate them for medium-drain devices like a small cassette player. 3At 70°F/21°C. 4Should be fully charged before use. 5The cycle life of a rechargeable battery depends on the average depth of discharge and the rate of recharging. 6Direct charging with a small, portable solar panel.

Lithium cells first slipped into our packs in industrial headlamps. The Chouinard-marketed Hartford Headlite, with a 3-volt bulb, used a D battery called the Eternacell, made by Power Conversion, that retailed for a stiff $20. This battery (lithium sulfur dioxide) would work in extreme cold and last for a whole expedition. But it was illegal to carry or ship it in aircraft, which put a cramp on the fun. The company, now Hawker Eternacell, has developed a lithium thionyl chloride cell that’s ideal for low-drain devices like LEDs, is legal on aircraft, comes in the AA size (3.6 volts/2500 milliamp hours [mAh]), and is somewhat affordable at $9 to $11, considering that it can last a season or more. It comes with the C. Crane Lithium Trek Light (this page) and is also available through electronic specialty houses.

Recently, Eveready Energizer has unleashed a flood of lithium-iron disulfide batteries in the 1.5-volt AA configuration. Designed for auto-wind cameras, these are now a runaway choice for camp lights. The advantages are seductive: light weight (about 60 percent of that of an alkaline cell), and a 10-year shelf life. But the word from battery specialists is that the internal chemistry of lithium cells diminishes their performance in low-drain devices such as flashlights—the exception being the use of a high-power bulb in cold weather. There seem to be few or no restrictions on shipping, air travel, and disposal. The sharpest disadvantage is cost: currently $3 each. And more significant, given that to build a small battery consumes up to 50 times the energy the battery itself can store, is the sad fact that lithium batteries can’t be recharged. So while I carry lithium spares, I seldom actually use them.

Nickel-cadmium cells (nicads) combine the two metals with potassium hydroxide and water. They’ve been in use since the 1950s, and the best ones can deliver hundreds of cycles. But most backpackers hate them—as I did, after running head-on into their peculiarities. First, they are chemically “stiff” and need to be charged and discharged completely (unto blackout) for a few cycles to break them in. Otherwise they develop a “memory” and will take only a partial charge—a vicious, downward spiral. Not that they last a long time even when perfectly charged: a nicad stores about half as much as an alkaline cell, and yields 1.2 volts to an alkaline’s 1.5. Another befoozler is that the nicad discharge curve is flat from 90 percent capacity down to 10 percent, so those little built-in voltmeters don’t give you a clue as to how much power is left. The only way to get it right was to run them stone-dead, then time the charging process—which could take 15 to 16 hours. So they also tended to get forgotten and overcharged: they heat up and are ruined. I also started out with cheap sintered plate nicads, which are easily damaged by overcharging—the powdered cadmium flakes off the nickel plates. And cadmium is poisonous as hell. Why bother?

Simply, if a nicad is treated right you can recharge it hundreds of times. Ten years ago, I got some quality pocket plate nicads (Golden Power AA, 0.8 oz., now $2.25 from Real Goods), that hold 700 mAh compared to 500 or less for sintered plate cells. I got serious about timing the charge. I also changed my battery habits, thinking of them as vessels to be filled and then emptied, like the tank of a tiny stove. I charged them before trips (they lose 1 percent per day on the shelf). And since the sun shines bright in Wyoming, I started packing a tiny solar charger to fill them up on the trail (see Solar Campsite, this page).

Once I’ve conditioned a good nicad, I can count on 60 to 90 minutes from a krypton-bulbed headlamp—with the batteries kept warm by my general hotheadedness. Other AA cells I use are from Power Sonic ($2.75) and C. Crane Co. ($2). I just got some Radio Shack Hi-Capacity nicads rated at 1000 mAh ($3.50) that hold up well, and the new Panasonic P-3GPA, rated at 1100 mAh, is said to be better still, though it’s hard to find (look at Costco or BJ’s Wholesale for a pack with four AA cells and a charger, at $15). Though formerly a butt cramp, recharging has been made easy: new microchip-controlled home chargers analyze each battery and vary the power, with a tiny “float” charge to keep the voltage topped up. So overcharging’s a thing of the past. And so is buying batteries. I haven’t bought a throwaway cell in 2 or 3 years. Amazingly, after 10 years I still use those original Golden Power nicads for all but the bitterest cold. And when they do at long last go belly-up (the new chargers inform you), Real Goods will recycle them so the cadmium doesn’t get loose.*3

Rechargeable alkaline batteries were introduced in the U.S. in 1993 by Rayovac with a companion charger as the Renewal system. Sold elsewhere under the names Pure Energy and ALCAVA, they’re properly known as rechargeable alkaline manganese dioxide zinc (RAM) cells. They have the same voltage, 1.5, as single-use alkalines and last about 85 percent as long—the first time out, at least. With each cycle, the capacity drops. Even with perfect handling, by cycle 10 it’s about 60 percent. By cycle 30 it’s 40 percent, and falling. (User consensus gives them 8 to 25 cycles.) So while the Renewal battery really burns out of the box, it can’t match the longevity of a nicad. For longest life you should charge Renewal cells frequently and not run them to the bitter end. The required Rayovac charger (which rejects worn-out cells) costs around $20.

A promising new RAM battery from Germany is the Accucell (Real Goods, AA, 0.8 oz., two-pack, $4; 4 pack, $7). In the AA size these pack more capacity than the Renewal, with the same constraints: frequent charging while avoiding deep discharge and heavy loads. The shelf life is the same as toss-away alkalines: 5 years or so. But Accucells are rated for hundreds of cycles—a big plus that’s led me to adopt them for general use. Like the Renewal cells, they need a special charger—see below.

Nickel-metal hydride (NiMH) batteries have a capacity about halfway between that of nicads and rechargeable alkalines, and contain no toxic chemicals. Like nicads they yield 1.2 volts and can be recharged hundreds of times, but unlike nicads they have no “memory” effect. They have a short shelf life, self-discharging 1 to 4 percent of their capacity per day. Tech wizards tell me that NiMH cells work best with high-drain devices such as the Sierra Stove (this page), and with frequent recharging. I tried some years ago and killed them off with a crude home charger. But chargers have vastly improved, and new NiMH cells are hitting the market, so I’ll give them another try in my solar campsite (this page).

Given the sheer number of batteries and bulbs now available—and my dislike for killing off batteries on the test bench—the comparison tests in the last edition are omitted from this one. For full technical details the best sources (given a healthy skepticism) are magazines such as Consumer Reports and the Web sites of battery makers that have OEM (original equipment manufacturer) sectors. Intended for designers and buyers, these have detailed tables, graphics, and other techno-babble, some of it in printable or downloadable forms (for fireside contemplation).

Given the considerable impact of manufacturing and dumping 2 billion batteries each year, we backpackers need to switch to rechargeable cells now. And that brings up the question of

Since the chargers sold in discount racks tend, unless carefully watched, to wreck batteries, the first step is to get one that won’t. For some years, I depended on a Saitek Eco Charger (from Jade Mountain, $56). It takes AAA to D cells (no 9-volters), works with nicads and alkalines, rejects dead or damaged cells, discharges nicads to beat the memory effect, and tells you how many hours each cell will take to recharge. It runs on 6 volts, via a house-current adapter. The Eco Charger reconditioned some old nicads that were marginal, and over two years saved me about two or three times what it cost.

Last year I started using the Innovations Battery Manager Ultra (C. Crane Co., $50) with a new pulse-charging circuit. It handles zinc chloride, alkaline, rechargeable alkaline, nicad, and nickel-metal hydride cells, AAA to D, in any combination, and rejects bad cells. Rather than telling you how long each cell will take to charge, it displays the voltage—by far the best measure once you get the feel of it—and works on a 24-hour cycle. It charges like a dream, but has a not-very-portable wedge shape. The input voltage (via adapter) is 9 volts.

Innovations and Accucell chargers

I’m now trying yet another marvel, the Accucell ACL 200 (Real Goods, $99), a German-made device that mates with Accucell highperformance RAM batteries. It does all of the above tricks, with Accucell alkalines, nicads, and NiMH cells, and also charges 9-volters. It can take up to eight AA cells at once. It lacks a voltage readout, giving you a red or green light instead—the only thing I didn’t like. But it charges remarkably fast, e.g., 80 minutes for a AA nicad. It’s also a portable, fat-pocketbook shape and weighs 1 lb. The input is 12 volts, via the AC adapter, and it comes with an automotive plug for use in a car.

Most people will like the Innovations charger for its charge-anything design and reasonable cost. But if you’re starting from scratch and intending to spend a lot of time both outside and on the road, the Accucell charger, with a set of matching batteries, is a farsighted choice. For expeditions or groups, the Accucell charger and a 12-volt solar panel might work out. I’ve got a 10-watt Solarex PV210 that’s 17.5 by 10.5 inches (about the same width as my shoulders, 2 lbs. 2 oz., $135) that can ride on top of a pack. New fiberglass-mounted 10-watt panels weigh only 1 lb. 2 oz. (Real Goods, $119). Solo artists will naturally want something smaller. For which, consult Solar Campsite, this page.

To find the voltage of the bulb you need, multiply the number of batteries by 1.5. Thus, a light with a pair of alkaline AA, C, or D cells in series needs a 3-volt bulb. Three cells need a 4.5-volt bulb, and so on. The amps are also a factor: a light with D cells (two, three, or four) will use a 0.5-amp bulb, while two AA or two C cells need 0.25 amp or thereabouts. If you don’t know what volts, amps, and watts are, for heaven’s sake look it up—and in the meantime, stop babbling about e-this and e-that.

The bulb must also fit the hole. Regular incandescent bulbs with a number prefixed by “PR” are prefocused and have smooth, flanged bases; those identified by a plain number have screw bases. Another increasingly common type is the seed, or bi-pin, bulb of much smaller diameter, with two bendable wire connectors. These come in packs of two, possibly because you always drop the first one and lose it. To further complicate matters, all these types—flange, screw, and bi-pin—are now made in various forms, to vary both brightness and power consumption.

Krypton bulbs are the common run, filled with (Superman, look out!) krypton gas. They have a warm yellow hue, like candle flame. With long use, the vaporized tungsten of the filament gets deposited on the inside of the glass, so they dim about 25 percent before burning out. They cost $2 to $3.

Halogen bulbs have a tungsten filament in a smaller quartz-glass envelope, filled with halogen gas. They’re bright, throw a long beam, focus well, and have a white light that trues up colors and details: it’s a damn sight easier to field-strip a stove with a halogen bulb. The tungsten particles evaporated from the hot filament don’t stick to the quartz glass—they stay with the gas and are redeposited on the filament, lengthening the life and lessening dim-out to 10 percent. (But the oils in your fingertips react with quartz glass, killing the bulb prematurely—so install halogen bulbs with tweezers or the clean corner of a bandanna.) Cost is $5 to $7.

Xenon bulbs are also very bright and focus well, so they’re showing up in specialized lights like the Pelican Super MityLite LMX Laser Spot Xenon Watertight—a mouthful—claimed to be “600% brighter than ordinary pocket lights” (3 oz. with two AAA cells, $11). The catch: batteries get used up quickly and the xenon bulb itself lasts only 20 hours. Cost is $4 to $6.

LED arrays (nonbulbs—see this page) are now raising their wee polycarbonate heads. They’re generally dimmer than incandescents while greatly multiplying battery life. But the price is a gasp: a PR (flange-base) array of three is $30 from Real Goods, and a screw-in base array of three for Petzl lamps is $20 from C. Crane. Still, the long life and the reduced weight of spare batteries in your pack make an LED array a worthwhile investment.

A last word: pack at least one spare bulb of the type you most use. For my favorite headlamp I carry three: an LED array, a standard krypton, and a high-intensity halogen or xenon (one, of course is always in the light). Some flashlights have places for storing spares, but mine travel in a plastic film can marked “Monkey Wrenches and Dynamite.”

COLIN: A chemical lightstick such as the Cyalume, Omniglow, and Snaplight (about 1 oz., $1–$2 each) is a nontoxic, nonflammable, waterproof, and windproof device that you “switch on” by just bending and shaking the plastic case and thereby mixing two chemicals. Unfortunately, you can’t switch the thing off. But its surprisingly bright greenish yellow light, said to last 8 to 10 hours at around 70 to 80°F, really does so. The light is said not to attract bugs and doesn’t seem to.

One stick lights a tent adequately and even lets you read smallish print—though because the all-around light, left unshielded, contracts your eye pupils it’s advisable to block off the light directed toward your eyes with finger, hand, stick, shoe, or some other handy and opaque item. In some ways a lightstick outperforms a candle lantern: it cannot set a tent or anything else on fire; knocking it over won’t put it out; neither will wind or rain; and you can hold it in your mouth. If, after balancing weight and cost, you decide to take lightsticks, make sure you pack out all spent ones.

Although its nonswitchoffability rules the lightstick out for general “flashlight” use, I find to my surprise that one will light your way down a faint trail that you know well, and would certainly do so on a well-defined trail. But you must use the stick properly. Tie or tape it to the end of a staff or stick and push it ahead of you like a mine detector. It’s essential that, to eliminate the pupil-contracting glare, you hold staff or stick at the right, blocking angle.

CHIP: A battery-powered version, the Krill Lightstick, is a 5-inch, 3-oz. tube of “micro-encapsulated phosphors” with a 3000-hour life span. It comes in six hues, from a bright pale green to a soft red. With two AA cells, the regular model lasts 120 hours ($25) and the brighter Extreme for 50 hours ($30)—candle lanterns without candles.

Other good backups are single LED penlights (legion) and keychain lights, like the molded Photon II (1 oz., $20) with two button-type lithium cells, a single LED, and a tiny switch to keep it on without having to squeeze. A pair of obsessed chums took Photon IIs as their sole light sources on a fairly serious mountain traverse. (That it was near the summer solstice proves they’re not entirely devoid of cunning.) But those Brand X ovoid keychain lights with advertising behind a wrap of clear plastic are chancy, though often free. I somehow acquired a Lumatec Flash Card, a sub-ounce battery/LED unit, 3½ by 3 by 3/16 inches ($5), which throws enough light to walk by but isn’t mouthable. Being flat, it slips in behind the signal mirror in my office-on-the-yoke (see this page). But for those times when you’re changing a headlamp bulb and the spring springs out, a mostly overlooked source of backup light is a digital watch. Mine, a Casio Alarm Chrono (0.8 oz., $14) casts a bluish phosphorescence just sufficient to get oriented and find important things, such as toilet paper and zipper pulls.

COLIN: When nights are long, and particularly if I expect to do evening reading or note taking, I sometimes carry a candle lantern. It will illuminate a decent-size tent pretty well and a small tarp shelter even better, especially if the tarp is white. You get enough light to write by, just about enough to read by if you have big print and good eyes, and more than enough to cook and housekeep by, even if you go roofless, provided you hang the lantern high so that household goods don’t cast too many concealing shadows. Theoretically, candle lanterns present a fire hazard, so I take care. For roofless camping the danger is nillish, and even out in the open the best candle lanterns generate a surprisingly practical light and will withstand a certain amount of wind.

You can suspend the lantern by tying a nylon cord to its hanging bail without fear of burning the cord—and with an auxiliary sideways-pulling cord, and perhaps some such convenient handle as a staff (this page), can adjust the sector of light so that it illuminates what you want to see while the blanked-off sector shields your eyes from bedazzlement. In good lanterns, the enclosed foot collects rather than distributes hot tallow.

You can replace a candle at night, while the wax is still hot and malleable, without too much grief—given a flashlight and reasonable familiarity with the device—though a pair of asbestos hands would help. You can replace a candle in daylight, even when the wax is cold and hard and intractable—given a stout twig to depress the candle platform, a wax-cleaning instrument such as the nail file on a small Swiss Army knife, plus a good deal of determination and patience.

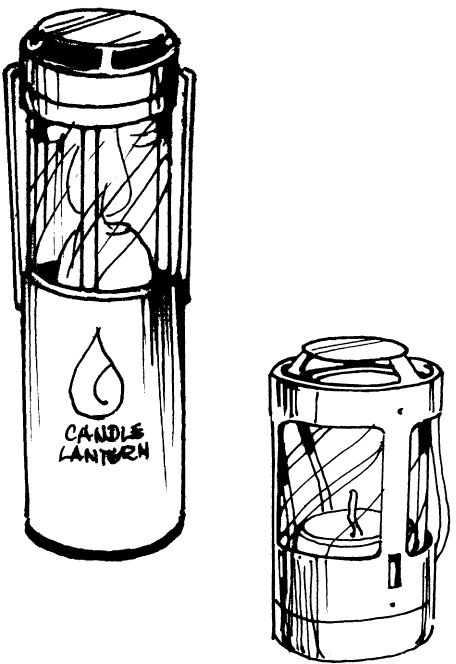

CHIP: Since 1985, Northern Lights (not Lites, thank heaven) of Truckee, California, has upgraded the traditional candle lantern with innovative models such as the anodized aluminum Flip-Top (easy lighting, 7 oz. with candle, $24–$29) and the Alpine 2 (6 oz. with candle, $14.50) of thermoplastic with a glass chimney that slides, upside down, into the lantern body for transport.

Northern Lights also designed a clever oil lantern, the Ultralight (5.5 oz., $24) that either hangs or sits on a springy, stable tripod base and burns up to 17 hours per 3-fl.-oz. filling. A new variant is the Compact Oil Lantern (5.3 oz., 3 oz. fuel, $24), which resembles the Alpine candle model (above), and burns 12 hours per filling. A leakproof cap covers both the wick and vent hole. It takes fiddling with tweezers to get the wick adjusted (barely showing above the brass tube), and the resulting flame is about half that of a candle. With the wick set for a steady, smoke-free flame, it was somewhat hard to light, so I aimed a butane lighter at the brass part for a five-count, which helped. It came with a surprisingly clunky chain, which I replaced (see lantern chains, below). Northern Lights also makes a Candoil insert ($10) of heat-resistant plastic to replace candles, with a 9-hour burn time. All these units will burn lamp oil (brightest flame—8-oz. bottle, $2.75), deodorized kerosene ($6 per gallon) found in paint stores, or regular old stinky kerosene (cheap), available worldwide.

Good candle lanterns are also made by Uco, including a slide chimney classic (7 oz., $18–$25) and a mini (3.2 oz. plus candle, $9.50) that burns tealight tub candles lasting 4 to 5 hours. The same candles fire the Olicamp Footprint Lantern, which has an unobstructed glass chimney and tripod base (3 oz. plus candle, $9.50). These newer candle and oil lanterns cast few shadows, with the metal struts thin or lacking around the glass. But if you like a one-sided light, a reflector that fits Uco and perhaps other lanterns can be had for $3.75. Lanterns with multiple candles are unwieldy for backpacking.

Uco Candle Lantern and mini Candle Lantern

Lantern candles are shorter and stouter than the common household type sold in groceries, are formulated for longer burning times, and cost from $.25 to $.60 each. Since all lantern chimneys are glass, cases of neoprene or fleece reduce breakage (1 oz., $3–$5). I use candle lanterns mostly for deep-winter trips, where their warm light is a comfort and the heat helps to keep frost away.

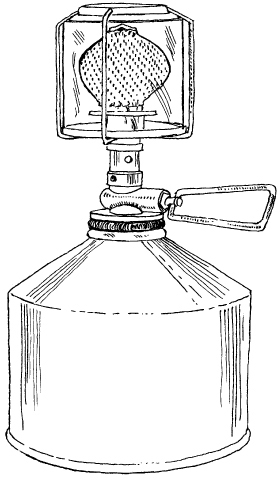

COLIN: These big, heavy, fragile lanterns are hardly normal backpacking ware, but in dead of winter they lengthen an otherwise very short day and also generate a wonderful amount of heat. On short-haul, permanentcamp trips at any time of year I guess they become feasible, even desirable. They certainly have uses at roadhead camps (also known, sort of soixanteneuf, as trailhead camps). But remember that in backcountry a lantern screens you off from the night even more drastically than does a fire (this page). And that although it doesn’t roar the way a stove does, the damned thing hisses all the time, right there by your bloody earhole.

The most popular lantern is probably the white-gas-burning Coleman Peak 1, with a base similar to that on the most recent incarnation of the stove (this page). It burns for three hours at 75 watts—“like a floodlight,” says one backpacker I know. “It’ll blast all your neighbors out of the backcountry.” The current Peak 1 Dual Fuel 229 weighs 28 ounces and costs $40. Spare mantles (#20, $2 a pair) are best found where the lanterns are sold but can now be ordered from a Web site: www.coleman.com. Like all pressure-lantern mantles, they’re very fragile for backpacking. Some years ago, reports alleged that the mantles emit dangerous radioactive material on burn-off; but Coleman assured me that, although their mantles indeed contain a small amount of thorium, users “receive at least 50,000 times more radiation due to natural radiation and about 20,000 times more radiation from radium dial watches during a normal year. The average individual dose due to eating a mantle is only 1% of the environmental annual dose.” The company also says that independent physicists and the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission have both concluded that normal use of mantles presents no radioactive hazard.

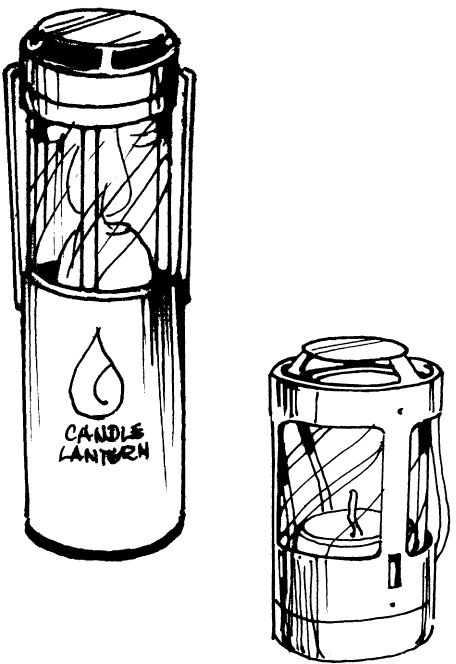

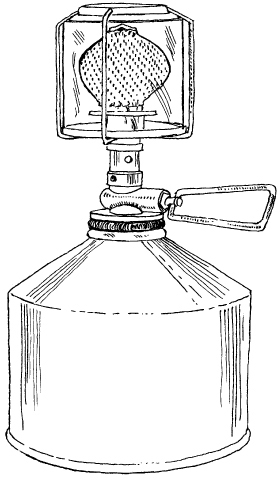

CHIP: In ever smaller and brighter designs, gas-cartridge lanterns are seeing more backcountry use, especially for group camps and snow caving. New piezoelectric ignitions make them a snap to light. And if you carry a cartridge stove, you can run a lantern on depleted cartridges that will no longer boil water (see this page). Most use slip-on (or double-tie) mantles with a drawstring at either end that are mostly interchangeable—but those labeled by the maker of each lantern are usually better quality than discount-store brands. While safer than liquid-fuel models, cartridge lanterns still present hazards when used in a tent or other enclosed space (see this page). And they still hiss.

Before we run down some new models, here are things to avoid. Most lanterns have a bail or chain for hanging, and if the spots where it clips are attached to the heat shield on top or in the path of the flame, then the chain will get hot enough to burn your hand or melt through a nylon loop. The now discontinued Peak 1 Micro lantern had this problem. Given the rage to miniaturize, other watchouts are that the glass chimney (or globe) fits into its cage without scratching and that the silk mantle doesn’t touch the tip of the piezo lighter, which will poke a hole in it. The third deadly sin is a noisy or wavering flame.

The well-proven Primus Trekklite (8.3 oz. sans cartridge, $75) has a wire bail that hinges below the glass chimney, and a clip-in heat shield above. It has a piezo igniter and casts a steady 80 watts of shadow-free light with a medium-low noise level. A younger brother, the Primus Alpine Easy PTL, also burns at 80 watts, is lighter (7 oz.), and less of a bite ($50). Both use Primus screw-on cartridges that are widely available in outdoor shops.

Mildly updating the popular Bleuet Bivouac 270 lantern shown above, the new Campingaz Lumostar lantern is bright (80 watts) and, like its cousin the Twister 270 stove, has a blue plastic housing that locks onto the Campingaz cartridge (not compatible with other brands) and a large, cool control knob. A red button keys the piezo igniter, which works consistently. The frosted chimney casts a nice but slightly wavering light, medium noisy. While the chain doesn’t get meltingly hot, I used a tent stake to handle it.

I like the well-made and affordable Markill Astro Lantern (9 oz., $30) for its steady and relatively quiet 80 to 100 watts of light. The clips are well out of the flame so the chain heats up less than others I tried. Still, I wouldn’t hang it in a small backpacking tent—like lantern makers in general, Markill advises no flammable material within 4 feet above or 2 feet to the side. The reliable piezo lighter is keyed by pushing the control knob, a nice touch, though I had to trim off some scraggy wires that tore holes in mantles. But on the whole, the Astro is a good pick for roadhead/trailhead/snow-cave outings.

Snow Peak GigaPower

Two smaller lanterns crossed my path. The Primus Himalayan Mesh Lantern (5 oz., $62) resembles the mini-burner unit that comes paired with a stove (this page). It has a chimney of stainless-steel screen instead of breakable glass but includes a hang-up rig and gives a wavering 15 to 25 watts of light. A stronger step in the same direction is the Snow Peak GigaPower Lantern GL-100, companion to their tiny and well-wrought stove (this page). It’s a spare design with a folding wire control stem and no provision for hanging; it gives a mildly wavering 80 watts of light. The brass screw-on base is compatible with Primus and Peak 1 cartridges—easier to find than Snow Peak’s own. The lightest of the gaslights (4 oz., $70), it comes in a tidy plastic case 2 inches square and 4 inches high. A piezo igniter adds $17 and half an ounce. Other accessories are frosted and stainless-steel mesh globes. I took the Snow Peak lantern on a hinge-season trip, with no tent, when I bivouacked in talus caves and under overhanging boulders. It’s a good little hand warmer but so bright that it regularly blinded me when I turned my head without thinking. And, too, it made me feel conspicuous, as if the cold, blue eyes of the mountains were on me.

Exponent Powermax Xcursion

A wild card is the new Coleman Exponent Powermax Xcursion lantern, with a built-in tank that refills like a butane lighter. A 20-second squirt from a full Powermax cartridge (this page and, for the matching stove, this page) gives 5 to 6 hours of light. It burns quiet and bright with a full tank, but after a while a ticking pulsation sets in, going from fast to slow, followed by a drop in the output. Still, looking over the prototype (the Coleman folks cautioned me that it isn’t the final production model) I’m struck by its cunning design. A front shell slides up to guard the glass globe and hide the ON/OFF control, preventing accidental turn-ons. The rear shell is mirrored within and can be left up or slid down to cast a full circle of light. Folded, the bail fits close for compact packing. The black base unthreads to reveal the brass filler nozzle, with room to stash a mantle or two, which you should do as a matter of course. The mantle on the lantern they sent me got pulverized in shipping, so I wouldn’t count on its holding up forever in a pack. The Xcursion mantle, #9970, a small sock-type with a metal push-on fitting, is different from the #20 tie-on mantle needed for the Peak 1 Dual Fuel lantern. (Yet another type, a tube mantle with open ends, is required for the Primus, Snow Peak, and other cartridge gassers.) Given the Xcursion’s innovative design, I was surprised to find that it lights via the traditional match hole—though a butane lighter with a lengthy flame does the trick. Weight, empty, is 12 oz. and the cost about $40.

Lantern chains. Some lanterns—the Markill Astro for instance—come with chains that are both light and strong, but others either have clunky chains or none. To make one, go to a hardware store and get the lightest chain they have (with twisted figure-8 links—no sharp ends poking out). You also need a small S-hook and a split ring. Crimped onto one end of the chain, the S-hook should fit through the split ring—which is rung onto the other end (total: 0.6 oz. and less than $1). The split ring can hold the bail of the lantern securely while the S-hook mates with webbing loops, etc. Or you can slip the S-hook around a tree limb and through the split ring, to swing the lantern from the hook. Length can be jockeyed by moving the split ring to another link. A lantern chain is also a useful adjunct for a hanging stove (see this page).

If you feel like trying a radically new approach to the whole game of light and heat, you might try a

This amounts to giving up fossil fuel as your immediate source of heat and light. You sacrifice some convenience (or at least some longstanding habits). But you gain considerable freedom. With even moderate sunshine, and any sort of natural combustibles, you can extend your walking range tremendously. The equation is simple: subtract the weight of the fuel you normally consume, plus bottles or cartridges, and add the same weight of food (or an extra book).

The basic solar-camp kit is simple. First comes storage—not a fuel bottle, but AA-size rechargeable batteries, either workhorse nickel-cadmium or perhaps nickel-metal hydride, both covered a few pages back (this page and this page). The light department consists of a flashlight or headlamp (this page) using the same AA cells, enhanced with an electron-stretching LED array. Heat comes from a Sierra Zzip Stove (this page), which uses a single AA battery to blow air through a small fire in a combustion chamber, fueled with virtually anything that burns: wood chips, yak dung, or charcoal from old campfires. Finally, and the key, is a solar charger that’s small and light enough to ride on top of a pack, and powerful enough to charge a pair of batteries in a day or less.

Solar campsite

The first solar goodie I used was a Stearns Sun Shower (see this page). They’ve been around forever and we all know they work. But my first inkling of a broader strategy came years ago, when poet Gary Holthaus told me of his walking several hundred miles with a Sierra Stove from Zzip Manufacturing. In crossroads stores, he said, batteries were easier to find than white gas, besides being a lighter load. After a while, he began to enjoy scrounging fuel for each meal. So I got a Sierra Stove (the new titanium version is pictured above—9.9 oz., $125) and learned how to use it—a simple process. It also didn’t take long to realize that if I could recharge the stove battery en route, fuel was no longer a limiting factor.

The problem with solar energy is that you get far more than you can use—sweating up a steep snowfield and sunburning your nose—and then at sunset are plunged into an energy deficit, cold and dark. So the key is storage. I use rechargeable alkaline cells for short hops, but drawing them down shortens their life and they can’t be properly charged with my small solar panel. So I settled on nicads and recently added a pair of nickel-metal hydride cells for the stove. Both types give out 1.2 volts compared to 1.5 for alkaline cells, so the fan in the Sierra Stove runs a bit slower—but not aggravatingly so. I depend on an LED headlamp with two nicads for hours of diffused-but-sufficient light for following a trail, cooking, reading, and other things I tend to do at night. For off-trail travel by dark, I switch to a halogen bulb and NiMH batteries, and keep two lithium cells handy for backup.

For long walks, with recharging en route, I now carry four high-capacity nicad AAs for my two-cell headlamp and two NiMH cells for the single-cell Sierra Stove. This means I’m doubled up on batteries, with a pair of lithium cells for emergencies (eight AA cells, total weight 6.1 oz., or less than one small gas cartridge).

Portable solar chargers. If you’re serious about solar camping, you need a good home charger that will handle different types of cells (see this page). Harder to find is a portable photovoltaic (PV) charger small enough to ride on your pack and capable of pumping up a pair of batteries with 4 to 6 hours of full sun or 8 to 10 hours of partial clouds. Some small PV panels simply lack the juice. I put a meter on a Solar 4-AA Battery Charger from Stearns/Basic Designs (3.5 oz., $17) and at high noon it put out 3 volts at 48 milliamps, for 0.14 watt of power. That’s not enough. A Universal Solar Battery Charger (from C. Crane Co. or Liberty Mountain Sports, 8.5 oz., $15) put out a useful 5.1 volts at 150 milliamps, for a strong 0.75 watt of power. It charges two cells at a time (AAA, AA, C, or D), but if you intend to use AA cells, the extra capacity is simply added weight. My favorite so far, the Solar World SPC-4 AA Pocket Charger (1.6 oz., $36) yielded 6.6 volts at 67 milliamps, for 0.44 watt. While the size of the solar panel provides a rule of thumb regarding output, the Stearns and the Solar World chargers have the same size panel. They’re also wired differently: the Solar World puts the batteries in series and requires “jumpers” (hollow brass conductors the length of a battery, included) if you charge fewer than four cells. The Stearns/Basic Designs charger is wired in parallel, so you can charge a single cell without jumpers. (The fewer cells the more juice each one gets.)

None of these chargers will strap to a pack as is. To mount the Solar World SPC-4, I got a $.69 flexible plastic drill box from a hardware store, sliced off the internal drill holders, and cut an opening so I could siliconeseal the panel on top with the battery pack inside (see previous page, right). Then I riveted a pair of webbing loops to the bottom so it rides happily on my pack, more or less rainproof, at 3.5 oz. If the charger you find is already in a plastic case, you can stick a strip of Velcro to it and sew a corresponding patch on your pack.

The main thing is not to shade the panel with a hat, towering hair, etc. For stationary use, I now prop the drill box open with a rock (not a twig as shown), which also ensures that it won’t blow over. The Solar World SPC-4 has a tiny red LED to indicate charging. A teeny built-in digital voltmeter would be great, but for now I estimate the discharge of each cell and keep track of the charging times. With power-saving tactics—an LED light and canny stove use—you can easily bridge a few cloudy days.

If you love to tinker, you might want to build your own custom charging rig. A plastic-covered mini-panel with 6-inch lead wires, rated at 6 volts and 50 milliamps, costs $18 from Solar World. You can make, or buy at stores such as Radio Shack, a “rat pack” to hold the batteries. A short length of cable with a plug lets you mount the panel on your pack and stow the batteries in the top pocket, out of the weather. But before buying anything, bone up on the electro-basics (volts × amps = watts). You need to match the solar panel to the type and number of batteries you intend to charge. Four 1.5-volt batteries = 6 volts. To charge a battery takes more voltage than the rated output, but too much juice can ruin or even explode it. I keep batteries of a single brand and type rubber-banded in pairs. Cells of different type, brand, or depth of discharge shouldn’t be charged (or used) together—the weaker cell will drag the stronger one down. Since the Sierra Stove uses only one cell at a time I use one to cook dinner and the other for breakfast, to keep the discharge on a pair of batteries even.

If your home charger lacks a voltmeter, it doesn’t hurt to get a simple multimeter (analog $10, digital $20) to check solar-panel output and battery voltage at home.

Not wanting to run out of juice on a long trip, I’ve run tabletop tests. For instance, a Power Sonic AA nicad (mid-1990s model) fresh from the home charger ran the Sierra Stove for 105 minutes. Charged with three others in the Solar World SPC-4 (8 hours in cloudy weather), it pushed the stove 55 minutes. The next day it snowed lightly. After recharging for 8 hours in low light, that same battery ran the stove for 25 minutes, a case of diminishing returns. But since the Sierra Stove can boil a quart of water in 6 to 8 minutes, I was sure that I could collect enough sunlight for my basic needs even on cloudy days.

The new Princeton Tec Matrix LED array (or equivalents, see this page) is bright enough for confident walking and gives 18 to 20 hours on good nicads—at 3 hours per night, that’s a week of Sherlock Holmes. Meanwhile, rechargeable batteries are improving so fast it’s hard to keep up: a new Radio Shack Hi-Capacity nicad (1000 mAh) runs the Sierra Stove for 3 hours 30 minutes—at my usual hour-per-day of stove use, that’s a bit more than three days’ cooking on one AA battery. A new Rayovac NiMH cell (1300 mAh) runs the Sierra Stove for a stunning 4 hours 31 minutes—four days plus breakfast. So potentially at least, four AA rechargeables (two high-capacity nicads for the headlamp, two NiMHs for the the stove, 3.4 oz.) can power a week of walking. And the whole packet—batteries, stove, headlamp, and charger—weighs 23 oz., which strikes me as at least mildly amazing.

Of course, this monkey-tinkering is food and drink to me. And more: solar camping cuts us loose from the fossil-fuel chains that bind us to drilling rigs and unsavory politics in Third World energy colonies like Nigeria and Wyoming. (Or somewhat loose, given the petrochemistry of our beloved synthetic fibers.) But a solar-powered walkabout is several thousand long steps in the right direction.

A solo, solar-ized trip

After furious tinkering I had the Solar World charger mounted and all batteries tested and charged. At midday I drove the dirt road to a familiar trailhead. Without the usual burden of fuel bottles, my pack felt pleasantly light—full speed ahead. An hour and a steep climb from the trailhead I topped a cloud-floating pass. The trail dipped into a canyon, and I left it to pick my way upstream along a glacier-scoured bench, over a patchwork of thin turf and bedrock. The last mile or so before reaching a camp I was on the lookout for fuel and noticed a sheep bedground (i.e., where domestic sheep sleep, or have slept), so I loaded a plastic bag with dry dung before making my camp farther on.

I enjoy scouting for fuel: old, gray chips of wood, winter-range moose dung (nice, compact ovoid briquets), or charcoal from old camp- or forest fires. Resinous wood and especially conifer bark and cones will tar your pot with sticky black. If you persist, it’s possible to glue the pot down (one cougar scream when you pick up the pot and the stove comes along for the ride). The best fuel is dense and nonresinous—worth stashing. It’s also smart to keep some tinder and small kindling handy in your plastic bag for rainy days.

I found a good camp and unpacked: odd not to be fumbling with a fuel bottle. Firing up the Sierra Stove with dried sheep flop, like an electrified Bedouin, I cooked my pot of soup with a grin. Then I watched the sunset burn bright on 13,000-foot peaks and settled down with a book and a headlamp.

The second day I cooked breakfast and slotted the used batteries into my little pack-topping charger. The red LED glowed as I climbed up a high valley between ranks of silvery summits. I scrounged dry wood chips and some charcoal from a firepit I passed—insurance for my above-timberline camp. The trees grew stunted, then hugged the rocks, then disappeared. A bright stream dashed down a rocky fold, pooling in a chain of chill, blue lakes. At 11,000 feet, I made camp on alpine tundra, amid tussock and grit, with a great, flat, frost-spalled plinth for a table. Scouting, I found dead willow stems and also, at the base of a cliff, more sheep dung—wild bighorn, perhaps. The old black pot boiled more merrily, or did I imagine it? Replenished by hot rock-belly stew, I read for an hour by headlamp and then slept to the music of a cascade that changed pitch with the shifts of night air.

In the morning, under a light frost, I changed the battery in the stove and discovered that after boiling up for coffee, I could toast bagel halves, perfectly, on the point of my knife over the glowing coals in the Sierra Stove. It beat hell out of a gas flame. After cleaning up, I set the charger on a sunny rock, stowed my pack under talus, and set off with a dual mission: to find the highest source of the stream and to climb a peak in my sandals. The stream, a thread, tumbled out of a snowfield on a windswept col. The peak loomed above, a scary-looking blade of granite that proved to have sandal-friendly ledges and ramps all the way to the summit.

Later, as I descended, high clouds tailed in from the west, boding a change in the weather. Deciding to camp in a lower, less-exposed spot, I caught up the charger and strapped it to my pack. Taking a lower line back down the valley, and still solar-charging away, I found a troll haunt ringed by krummholz and windbreaked by a natural parapet of rock. Weathered wood, a mere double handful, with some charcoal from the plastic bag cooked my meal and brewed black tea for the evening chill.

The sun rose but the sky was occluded, clouds lowering, and the air tasted of rain. I brewed up and toasted, reloaded the batteries—still the original four—and strapped the charger to my pack to head downvalley. The clouds parted and re-formed, and I wondered whether I’d catch enough light. For the rest of the trip it stayed cloudy, raining at times with a light morning brush of snow on the highest peaks. But those same four batteries, charged by day, continued to spin the fan on my stove and light my headlamp. I never even touched the spares, let alone the emergency set, though I ate and drank heartily, and by night devoured Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons. With the charger riding my pack I felt lighter on my feet and while scouting for fuel, goofily happy. Toasting a bagel, I beamed back at the morning sun. There’s no explaining such things.

Recharge-ability can transform your notion of camping in unexpected ways. On the semifrivolous end of the spectrum, I picked up a Coghlan’s 2-AA Mini-Fan (3 oz. with batteries, $3, Campmor) for a stint on a panel at a book fair. But I’ve ended up carrying it on summer backpacking trips, since it makes those midday, dead-air halts less deadly. A whirring minute or two dries the sweat prickles on my face and neck. Suspended with the elastic belt-clip thingie that came with a flashlight, it also makes a hot tent tenable—for the half hour or so that the batteries last (were it not for rechargeables I’d not be tempted). But with them, the Mini-Fan softens the neopuritanical aspects of solarizing with a luxurious microbreeze.

Chip and mini-fan

Direct solar heat. If you’re cold, go sit in the sun—that much is obvious. But further tinkering has given mixed results. I made a snow melter for high elevations or winter camps by cutting a Maltese cross out of a discarded forest-fire shelter (reflective cloth) and duct-taping it into a tapered box-shape (18 by 9 by 5 inches, 2.5 oz.) that holds two pots. At one edge, I stuck on Velcro tabs to attach a flop-top of clear plastic (2 oz.), the stuff used for windows in tent flies, to boost the efficiency. A simpler dodge is to use a clear plastic “oven bag” that can’t blow off. When it fogs up, the water’s hot. To catch low winter sun, I cut a reflector (20 by 14 inches, 1.5 oz.) of the same reflective cloth, which can be stretched between sticks or pinned to a wall of packed snow. The whole thing folds flat and weighs 6 oz.—less than one gas canister. To hold the device, I carve out a recess in the snowpack, which softens surprisingly little as melting goes on. Using an MSR Blacklite Cookset (this page), I’ve melted a gallon or more on sunny winter days, adding and emptying. If you pack the pots with snow and leave them alone, the yield is less but still enough to make the effort worthwhile. On a bright day, a pot packed with snow and ice at 11:00 a.m. was completely melted by 2:00 p.m. Clouds rolled in, but by 3:00 p.m. the water had heated to 95°F. (Setting a black pot on a dark rock gives similar results.) The melter is also a cooker: rice and red lentils simmered tender in 6 hours of bright sun. If you plan to occupy a base camp for several days, it can save gobs of fuel. But if you’re on the move with a new camp each night, neither the solar melter nor any of the lightweight solar cookers available will do you much good—either process takes hours. Another problem is that solar cookers in the lightweight/cheap category are made of foil-coated cardboard or lightweight plastic, so the slightest gust tips them over. Carving out a recess or using stakes can help, but in any event you need to stay close by. And being tethered to a stove—even a solar one—rather defeats the purpose of being out there.

On the whole, though, solar-powered trekking is not just practical and range-extending, but actively pleasing. In regions of dependable sunshine it may in the long run prove more fail-safe than fossil-fueled stoves.

My main sources for portable solar gear (full info in Appendix III) have been C. Crane Co., Jade Mountain, Solar World, and Real Goods. In particular, Real Goods publishes a wide range of material on solar and remote living and a catalog that lists many items (LED lights, water filters, even a hiking staff with a built-in flute) of interest to backpackers. Meanwhile, I’m perennially on the lookout for new sun-driven schemes—if you have one, write. And good luck tinkering.

While you’re catching bright sun on your PV charger, for your eyes’ sake you should temper it with

COLIN: Dark glasses are a comfort and convenience just about anywhere, almost indispensable in deserts, totally so in snow or at high altitudes.

If you find your eyes bothered by glare in low, snow-free country, any sunglasses that are optically true should nip the trouble, even in deserts. (Notes: Blue eyes tend to be more affected than brown. And you can check the optics of sunglasses by looking at reflections of straight lines—such as fluorescent store lights—in the concave surfaces: if the lines curve near the outer edges of the lenses there is distortion.) Polaroid glasses protect eyes and also let you look through the surface glare of water—often a big advantage in fishing. Sunglasses come in various tints, and choosing between them is often a matter of personal psychological preference rather than optical efficiency: some people like the world rose- or blue-gray-tinted, others rebel.

If you wear eyeglasses all or some of the time, prescription sunglasses will do the best job. But clip-ons or a large pair that fit over your normal glasses will do, and they certainly make good spares. (Other useful spares: the frameless, flimsy, but ultralightweight plastic affairs that oculists give you to protect your eyes after dilation; for permanence, patch with ripstop tape at the bends.) Once you’ve graduated to bifocals, clip-ons or big overglasses are the only practical answer if you want to read a map or indeed to see anything close up. I like clip-ons (though they’re fragile and must be protected when not in use) because I can just flip them up when I walk from sunlight into shade—a surprisingly valuable bonus. You can sometimes get ordinary sunglasses big enough to wear over your prescription pair.*4

At high altitude—above about 6000 feet, say—and especially in snow, your eyes, of no matter what hue, need protection from ultraviolet and infrared rays. Ultraviolets are the “tanning” rays: the skin recovers from their effects, but your retinas may not. Infrareds can also cause permanent retinal damage but, long before that, may produce fatigue and, eventually, excruciatingly painful snow blindness—which may not develop until hours after you’ve come in out of the sun. So up high, where the earth’s atmosphere filters out far less of these rays than it does lower down, you need protection from both UV and IR. Glass of any kind filters out UV, but you need special darkened glasses to deal with the IR. Plastic clip-ons or overglasses that filter neither may do more harm than good: they allow your pupils to open up and admit more light to the retinas. Plastic-over-plastic guards against neither UV nor IR; plastic-over-glass at least eliminates UV.*5

In snow, even low down, and especially in sun, your eyes are about as much at hazard as at high altitudes. For treatment of snow blindness, see this page and also the first-aid references, this page.

The standard high-altitude sunglasses were for some years those made by Vuarnet. The glass lenses are so tempered that even if broken they shatter into harmless round blobs, not lacerating shards. And the cadmium-coated lenses have green zones at top and bottom to filter glare from sky and underfoot snow, and an amber zone amidships. They work well in both sun glare and flat light. Frames are so pliable and tough that you can tie a knot in the temple and let it spring back to normal. The excellent Vuarnets became something of a fad, especially among skiers, but many viable alternatives are now cheaper or lighter or offer other advantages. The spectrum is too broad to detail here, but the names include Bollé, Bouchet, Cébé, Galibier, Julbo, Loubsol, Ray-Ban (Bausch and Lomb), and Ski Optics. Catalogs—especially REI and EMS online—teem with others. Average weight: around 2 ounces. Cost range: $35 to $150-plus. Those with polycarbonate lenses (treated to remove all or most UV as well as IR light) are lighter and less liable to fog but need greater care to prevent scratching.

Adjustable elastic restraining straps will hold glasses in place no matter what you do. The original neoprene Croakies (¼ oz., $5) are said to keep your glasses floating in water. Other styles in cotton or nylon cord (by Chums, Hotz, et al.) merely keep them on or, if slacked off, secure but resting on your chest.