It would seem reasonable to suppose that you can escape from the man-world more easily if you walk out into wilderness without a

But the stratagem may backfire. Without a watch you may find yourself operating so inefficiently (as can happen if you go without maps) that ways and means begin to obscure the things that matter. It’s not simply a question of knowing the time of day (provided the sun shines, you can gauge that kind of time accurately enough—though in dank or snow-clogged weather or in country so precipitous that the sun sets soon after noon, even that may prove a problem): you have lost the sharp instrument that keeps prodding you forward. That’s what I find, anyway, because if time and distance are important I often mark on my map the time I stop for each halt—or at least note the time mentally. Without a watch, too, I can’t work out times and distances for the way ahead. And that, for me, means a loss rather than a gain in freedom. Some people find the precise opposite. But the fact remains that after a single weeklong trip without a watch I went back to wearing one and have never rewavered.

Even without a watch, by the way, you can figure out the time at night, roughly—if you know what you’re doing, which few of us do—by watching the position of the star Kochab: it circles the nearby North Star counterclockwise once every 24 hours. Or so they say.

CHIP: Unless you’re one of those Rolex types, with a porter to support your wrist, or the possessor of a new multifunctional whizbang such as the Suunto Vector Wristop Computer (this page), you probably take your everyday watch backpacking. Traditional dial types have certain advantages: they can be used as a sun compass or a signal flasher (this page). But digital watches, in all forms, are ever more common. Colin straps on a batteryless, solar-powered, water-resistant Casio (1 oz., $27). I have a yet more basic one, the Casio Illuminator (cool name, 0.8 oz., $12) with a button-activated backlight bright enough to find a roll of TP at relatively short notice. It also has a stopwatch, a timer, and an alarm with a tortured-mouse skreek that wakes me up if I really want it to. The neo-plastique band stretches little and never stinks. I persuade myself that even H. D. Thoreau might grudgingly approve. But he’d probably write an essay decrying what I intend to replace it with: some micro-devilbox like the Suunto Vector. Still, I have to break the Illuminator first. Don’t hold your breath.*19

COLIN: A cruder kind of time figuring is almost always essential:

Even if you have no vital commitments to meet in the outside world, you should before leaving roadhead give somebody a time and a date beyond which it can be assumed that, if you have not shown up, you’re in trouble (this page). Or you may have arranged an airdrop, or a meeting with packers or other walkers. In any of these cases a mistake in the day can cost you dearly. And the mistake is remarkably easy to make.

I always prepare a table on a page near the end of my notebook (not the last page, because it may pull out). I block out the days and leave room for writing in the name, actual or fancied, of the place at which I camp each night. This detail, I find, is the one that my mind distinguishes most clearly in identifying the days. Without my calendar table I would often—perhaps most often—not know for sure what day it was. The table also makes it much easier to figure out, days ahead, whether I really need to hurry or can afford to amble luxuriously along.

Having a watch that reports day and date has not made me forgo the calendar-table habit. But then, I’m a cautious s.o.b.

Theoretically, this instrument is a valuable item. But although I own one I’ve never got past the finicky job of trying to calibrate it to my normal stride. Perhaps that’s because I question how useful such calibration would be over any but smooth, level ground—and because I regard wilderness mileage figures as being, in most cases, singularly meaningless (this page).

It’s many years now since I began taking a thermometer on walks, and I still have no reasoned explanation of why it makes such a beguiling toy. I have to admit, I suppose, that it’s primarily a toy. It has taught me any number of intriguing facts: the remarkably tenuous relationship that exists between air temperature and what the human body feels (this page); the astonishingly hot surfaces your boots often have to walk on and can sometimes avoid (this page, footnote); and the actual temperature of a river I needed to swim in (the body is a miserable judge here too, and the temperature can be critical if you have to swim far [this page]). But the sort of information my thermometer has given me has more often been interesting than practical.

One February I took a three-day hike along Point Reyes National Seashore, just north of San Francisco. On the last day a cold, damp wind blew in from offshore fog banks. At lunchtime I sheltered from the wind in a little hollow on the edge of the sand dunes bordering the beach. Down in the hollow, the wind barely rustled the thin, tough blades of beach grass. And the sun’s reflected warmth beat up genially from pale sand. After a few minutes I felt sweat beginning to trickle down my face. Idly, I checked the temperature in the shady depths of the densest grass: 64°F. Then I moved the thermometer out into the sun, on open sand. The mercury finally stopped at 112°.

For no clear or logical reason I for years checked and noted temperature readings: in shade and sun; in the air, on and below the surface; above, on, and below different neighboring surfaces; in rivers and hot springs. Once I found myself delighted by the singularly useless information that it was still 55°F in my boots half an hour after I’d taken them off, when the ground temperature had already fallen close to freezing.

I suppose I gradually gained from such readings, in an untidy and diffuse sort of way, some new and rather tangential understandings of how our fascinating world works, but I doubt that this is really why I went on with the measuring and figuring. Mostly, I think, it’s just that I enjoy my thermometer. And although I play with it less nowadays I rarely go without it. It clips into my yoke office, alongside pen and pencil.

I used to carry an ordinary mercury-filled thermometer, but the glass stem regularly broke, scattering freelance blobs of mercury—now recognized as highly and persistently hazardous. One benign alternative: an Enviro-Safe model with citrus-based filler and plastic armor (1 oz., $13). But for many years I’ve used a nonliquid, bimetallic dial model by Taylor, with clip-equipped plastic sheath (0.5 oz.; not sure of price—they’re now hard to find). In spite of the dial’s being set at right angles to the stem, it’s tough. Forestry Suppliers sells the similar Taylor Bi-Therm Pocket Case thermometer, −40° to 160°F (2 oz., $15). You can also get cunning little plastic thermometers, hangable “from pack or parka” (1 oz. or less, $3–$5), and thermometer/compass combinations abound at $5 to $10. For all I know, they may work.

Practical hints: Try to calibrate a new thermometer against a reliable and preferably official one. For a quick “shade” reading when there’s no shade, twirl the thermometer around on the end of a length of string or nylon cord that you leave knotted to the carrying loop; but check the knot first (see knots, nylon cord, this page). In hot weather be careful where you leave the thermometer: in the sun, surface temperatures can easily exceed 130°F; and much beyond that, if you use a glass-stemmed model, you may find yourself with an empty one. I haven’t experimented to find out if a bimetallic dial goes monometallic or something.

Of course, real cognoscenti scorn thermometers. They calculate ambient temperature instantly by counting the number of times any neighboring cricket chirps in 14 seconds, then adding their age next birthday.

Windmeter

CHIP: Under certain conditions, especially in winter, knowing the wind speed might be useful as well as interesting. The Dwyer Wind Meter registers up to 66 mph (2 oz., $13.95) by means of little colored beads in a plastic tube—no batteries required. Toward the high end, the Brunton Sherpa digitally registers wind speed, windchill, temperature, barometric pressure, and altitude—to 30,000 feet (2 oz. with 3-volt lithium battery, $155). As we go to press, some makers are threatening to combine weather functions with GPS receivers, for a new generation of micro-devilboxes.

Mending beats spending. But for laborious, blood-boiling fixes, like replacing zippers, the first step is to check the warranty. Lowe Alpine Sports and Sierra Designs have repaired fairly ancient packs and tents for me (though in one case my rezippered pack came back with a note reading “Please!!! Get a new one!!!”). Most good mountain shops will ship warranty items to companies whose gear they sell. The disadvantage is considerable downtime. Some shops also do backroom repairs or will refer you to local fix-meisters. There are also mail-order repair outfits, like Rainy Pass Repair, that specialize in hard-to-fix things like ripped Gore-Tex, and some now offer quick estimates via the Internet (see Appendix III). But you’ll often want or need to do your repairs at home.

I keep swatches of fabric, repair tape, grommets-and-setting tools, plastic buckles, and other oddments in my workshop, jumbled in a cardboard box. Memory being a porous vessel, I inspect gear after—soon after—each trip, and fix things before stowing them away. This approach was not inborn but learned. Repairs made under pressure late at night before a trip can be sketchy at best, and that missing gaiter hook—how did I forget?—will haunt you.

My emergency repair kit, an Altoids box I call Gremlin-Smasher, weighs 3 to 4 oz., and holds:

Tape

Repair tape comes in a rainbow of colors and most outdoor-type fabrics: Cordura, ripstop, taffeta, clear, and duct. Tape in rolls and patches from Eureka, Kenyon, and W. L. Gore (black only) can be found in shops. Mostly, the stuff sticks—and will withstand a certain amount of washing but not dry cleaning. Sewing the edges makes it permanent (see this page). If you worry about matching colors, makers sometimes include repair kits or can supply swatches, if you act while the fabric or product is in stock. New stick-ons include Scotch netting repair patches (from Moss Tents and others) for holes in no-see-um mesh. Gremlin-Smasher (my fixit kit) holds mini-rolls of regular and reflective duct tape, with light and dark ripstop tape and three mesh patches Scotch-taped under the lid. If you don’t mind the fuzz, moleskin works too.

Colin stores needles in his matchsafe with short lengths of strong thread threaded through three or four needles and wrapped around them like pythons. A longer reserve of thread, wrapped around a small piece of paper, goes into his “odds and ends” can.

An Alaskan reader suggests “glovers’ needles,” with #7 a good starter size. Glovers’ needles have triangular points, and Eskimos apparently use them for skin sewing. I have a piece of cardboard scalloped at the ends, with white and black thread pythoned around it and four needles run through: two regular ones, a glover’s needle for tough fabrics and leather, and a leather or canvas needle with an extra-large eye, for waxed-linen boot maker’s thread (in a separate hank). For heavy sewing, the pliers on a pocket tool or a chunk of bare wood can help get the needle through.

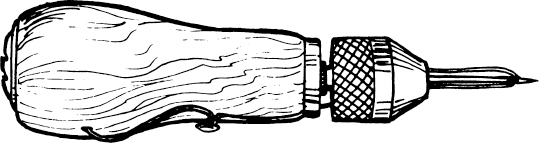

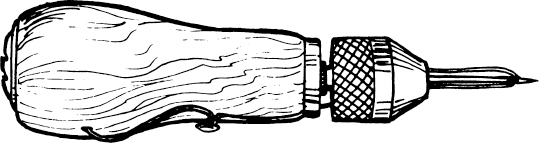

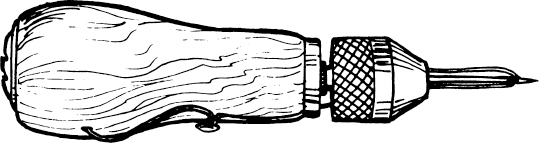

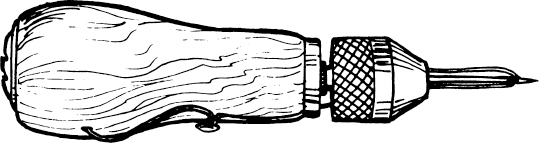

Speedy Stitcher

For heavy repairs, the Speedy Stitcher Sewing Awl is invaluable (3-plus oz., $10). The strong wooden handle houses a replaceable bobbin of waxed thread and two interchangeable needles (straight and curved #8) with eyes near their points. With brief practice you can make a precise lockstitch even through leather, packcloth, or webbing straps. I don’t cart it while backpacking, but for large groups or remote expeditions it could save the day, particularly if pack animals are involved. And if you and the yak-wrangler hit it off, it makes a thoughtful parting gift.

You can’t carry spares for everything. But some items depend on one small piece or two whose loss or damage could screech your trip to a halt. If the maker includes a tent-pole repair sleeve or spare clevis pin, that’s a strong hint. Gearheading with friends and local shop staff can provide further clues. If there are parts that need adjustment or removal en route, think about what might get dropped (God forbid!) in the snow. Plastic buckles are high on my list.

My life is a makeshift, so my repairs tend to be pretty-damn-good. Fixing things settles my mind, and Gremlin-Smasher (my repair kit) is like a snapshot album of mishap and ill fortune, mostly resolved. It’s a repository for the obvious, like safety pins, and also for all those wee trip savers that experience reveals: rivets, washers, grommets, brass tacks, teeny screws, cable ties, twist-ties, heat-shrink tubing, a precut leather patch, emery cloth (outlasts sandpaper and doesn’t fall apart when wet), stainless steel, brass wire, ad monkey-tinkerum. Further resources such as duct tape (for everything), dental floss (for sewing), and repair compounds such as Aquaseal and Shoe Goo (for boots, sleeping pads, tent floors, etc.) are found elsewhere in my pack.

Prebagged kits are available for common horrors, like dentally impaired zippers. In fact, complete—perhaps overcomplete—repair kits are now on sale from Gear Aid and others. These tend to be well thought out, with nice surprises like a hot-melt glue stick. If you have zero, such a kit is a good start. But the drawbacks are the same as with prepacked first-aid kits. Things you already have are duplicated, at considerable expense. Quantities are overgenerous (a full-size tube of Seam Grip?). Sizes can be off, as with a generic tent-pole repair sleeve. And the total weight soon catches up with you. The Gear Aid Basic is a solid repair kit, no mistake, but it costs $25 and weighs 8 oz. And if you’re overburdened with spares and repairs and quick cures, you’re far more likely to need them.

Repair hints for specific items are scattered throughout this book.

COLIN: For many people, perhaps for most, a walk is rarely a self-fulfilling operation, whether it lasts an hour or a summer. Alone, with an agreeable companion, or in a group, they walk as a means to some such specific end as hunting, fishing, photography, birdwatching, sex, or geology.

Generally speaking, I regard the equipment for such activities as outside the scope of this book. There are a few exceptions.

Fishing

An orthodox 2- or 3-piece rod is a perishing nuisance on a backpack trip. (I’m thinking primarily of trout fishing, because that’s what you usually find in the wilder areas still left for backpacking. And I’m thinking above all of fly-fishing, because in most remote areas that’s the way to get the most pleasure from your fishing—and sometimes to catch the most trout. But what I have to say applies to most kinds of rods.)

If you lash an orthodox rod to a pack upright—the best place for it—the risk of damage is high, though a dowel or stick rubber-banded to the uncased rod may help. If you tote along an aluminum rod case, the wretched thing tends to get in the way, especially if you use an I-frame pack. When fishing is your overriding object, the inconvenience may be worth it; but if fishing is really an excuse for escape, and even more if it’s just a possible bonus, the solution lies in a portmanteau rod—4- or even 6-piece.

The difficulty with this kind of rod is always its action: the perfect rod is a 1-piecer, and every metal ferrule marks another step down from perfection. Each ferrule also used to add critically to the weight, but new alloys have pretty well solved that problem. On this count, even some cheaper fiberglass rods now score high. And the very best dispense with metal ferrules: fiberglass fits into hollowed fiberglass. The results are featherweight wands with smooth, lively actions.

Many portmanteau rods, some of them ferruleless, now appear in outdoor catalogs. Among the best known: those by Fenwick and Daiwa. Some have reversible grips for fly-fishing or spinning.

My 4-piece, 7½-foot ferruleless fly rod, custom-made by The Winston Rod Company, formerly of San Francisco, now of Twin Bridges, Montana (2 feet, disassembled; 3 oz.; cloth cover, 2 oz.; aluminum case, 7 oz.) fits snugly down one side of the packbag, close beside the packframe. It mostly travels in the cloth cover and has never come to any harm. When using an I-frame pack I tend to carry the protective aluminum case.*20

The rest of my backpack fly-fishing tackle fits into a small leather reel bag: the reel itself, six spools of nylon (2-, 3-, 4-, 6-, 8-, and 10-lb. test), a small can of flies, line lube, and fly flotant. Total: 11 oz..

Anyone with enough wit to resist the widespread fallacy that you go fishing mainly in order to catch fish will understand that spinning is a barbarous way to catch trout. But I have to admit that there are places, such as certain high mountain lakes, where fly-fishing may be useless. And there are times, of course, when you’ll want to fish purely for food. For such occasions I have once or twice carried a little closed-faced abomination of a spinning reel (9 oz.) that takes most of the pleasure out of fishing but does not demand a large butt ring on the rod and can therefore be used with a fly rod. Into the abomination’s little bag went some lead shot and weights, a few lures and bait hooks, and a bobber.

There are times when fly-fishing is plainly impossible. (Often, for example, when the fish are not trout.) So I have a 4-piece, 4-oz., 6-foot spinning rod that breaks down to 20 inches. It was made to my specifications nearly 30 years ago from a hollow-glass blank that I selected from stock. My other spinning tackle is standard.

You can fish purely for fun—and get it—with emergency tackle (this page) and a light switch cut from the riverbank—if cutting it seems acceptable in that place.

I’m aware that many people condemn fishing as a barbarous pursuit, lumpable with hunting. Seen from the outside, it may be—especially if the view includes close-ups of those pitiless (or, more likely, unthinking) rodmen who wrench their catch off the hook and leave it to gasp to death by inches. Even intellectually, though, I think it’s possible to unlump fishing from hunting. Fish, for example, have simple nervous systems that don’t seem to register pain as we mammals know it: I once hooked a small brook trout, brought it in almost to my feet before it came off the hook, and watched it swim back a few yards to its original position, then take my fly again within a minute or so. But hunters shoot birds or fellow mammals, with fellow nervous systems: a shot rabbit that just makes it back down its burrow, shattered leg gushing blood, is hardly likely to come back, like my brook trout, for another sample. Again, provided you wet your hands first and then work gently, you can, especially when fly-fishing, return without harming it almost any fish you don’t want for food. (Dry hands remove protective slime and leave a fish vulnerable to disease.) But you cannot by any known means set free a doe once it is lying there with its eyeball hanging and brains spattered—even if you had thought it was a buck, or if your natural hot hunter’s blood has drained away and left only chill once you stand over your twitching victim. Furthermore, I see a fly rod as a delicate wand, a gun as an instrument of war. Here we may be closing on the nub. In the end, I think the difference is aesthetic. I find fishing a gentle and artistic pastime that calms me. And I see hunting otherwise. (I speak only of hunting as a sport. I have no quarrel with hunting purely for food, as a necessity. I’d do it anytime.)

A Wisconsin reader who hunts wrote in response to the above, disagreeingly but agreeably. He asserted that hunters as a whole are “a group of dedicated, aware conservationists” but readily admits they are “severely plagued by slobs in their ranks.” He also claims, with considerable reason, that we have in many cases caused overpopulation—as with deer—and that “it is therefore the responsibility of man, who threw the monkey wrench in, to correct the situation by ‘removing nature’s intentional excesses.’ ” He sounds a sincere and likable guy. And I’ve become increasingly aware that certain men whom I like and respect, men whose knowledge of and even veneration for wildlife is at least as great as mine, find hunting a satisfying and natural pursuit consonant with their veneration. Furthermore, I often feel more comfortable in the company of men who I know are hunters—even though I deplore what they do in that role—than I do in the company of many “ecologically aware individuals” who share my concerns but who never for one moment, by God, let you forget that they are the Chosen Defenders of the Earth. It’s all very difficult—yet another instance of the not easily digested fact that you can like a man but dislike what he does. And vice versa.

For the first 44 years of my life I thought of birdwatchers, when I thought of them at all, as a frustrated and ineffectual bunch of fuddy-duddies, almost certainly sex-starved, who funneled their energies into an amiable but pointless pursuit. My competence in their field was naturally close to zero. (“Naturally,” because the firmest and most comfortable base from which to make sweeping judgments about any group of people is total ignorance.) But 35 years ago, on a return visit to East Africa, I bought an identification book of the astonishingly prodigal birdlife of that astonishingly prodigal land. And at once I began to understand about birdwatching. It wasn’t merely that birds, really looked at, turned out to be startlingly beautiful, nor even that individual birds, like individual humans, engaged in funny, solemn, bitchy, pompous, brave, ludicrous, sexy, revolting, and tender acts; after my first real attempt to identify individuals from the book, I wrote excitedly: “Fascinating. Not just collecting species. This business makes you see.” Within days I was a full-fledged convert, always eager to try out the new plumage by reaching for my birdbook.*21

My conversion stuck (though it was maimed, and has never fully recovered, when someone broke into my car and stole, among other things, my American birdbook with its records of 10 years’ sightings). And I long ago learned that, from a practical backpacking point of view, a convert to birdwatching will find that if he didn’t take binoculars before he will certainly do so now; that he will have even more difficulty than before in not stopping and staring when he should be pounding along; and that, everywhere for a while, and in new country forever after, he will at least consider carrying a birdbook.

CHIP: Among practitioners, the preferred term is now “birding.” This accords with “boating” and “biking,” although watching a film is not “filming,” nor is dining in a restaurant “fooding.” In any event, the semi-hallowed U.S. standards for birders are two books illustrated by Roger Tory Peterson, published by Houghton Mifflin: A Field Guide to the Birds: A Completely New Guide to All the Birds of Eastern and Central North America (4th edition 1998, 384 pages, paperback, $18) and A Field Guide to Western Birds (reissue 1998, 431 pages, paperback, $18). The criticism one hears of these guides is that the illustrations are separated from the text, so you have to flip nimbly.

Some people prefer the Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds—Eastern Region (Alfred A. Knopf, 2nd edition 1994, 796 pages, paperback, $19). The western region guide is presently out of print. There are so many other birdbooks, each with its clamor of partisans, that we’ll stick to well-trodden ground. Birds of North America by Chandler S. Robbins et al. (Golden Press, revised edition 1983, 360 pages, paperback, $13) is another favorite of birders. It has range maps that Colin once described in this book as “excellent” but which he was told could more accurately be designated “colorful.” Another book with range maps, about which users likewise disagree, is The National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America by Jon L. Dunn (revised and updated 3rd edition 1999, 480 pages, paperback, $21). Linda, a devout birder, prefers this last, with illustrations facing the text. She has the second edition, and the third has drawn fire for quality problems like poor color printing.

There are scads of good regional guides and also natural histories, such as the voluminously titled Birder’s Handbook: A Field Guide to the Natural History of North American Birds; Including All Species that Regularly Breed North of Mexico by Ehrlich, Dobkin, and Wheye (Fireside, 1988, 785 pages, $20).

The Audubon Society and other birdophilic groups sell a range of belt cases, shoulder bags, book covers, tea sets, and such that is simply indescribable. Readers have suggested simple open-top bags or pockets, stitched to clothing or hanging from neck straps, possibly with extra room for protecting binoculars. One even urges the use of a “birding vest” on the order of a fly-fishing or photographer’s vest, to neatly transport a full assortment of field guides plus checklists, notebook, birdcalls, sunglasses, sunscreen, lip balm, repellent, and energy bars.

COLIN: However you carry your birdbook, it may pay, if it’s green like the hardback Peterson, to stick a strip of bright red ripstop tape around at least half its cover so that it will, if lost, stand out from surrounding vegetation. I learned this lesson several years ago, the hard way. At 4:00 p.m. one day I discovered that my Peterson had slipped from its makeshift, nylon-cord sling somewhere in the course of a long, rough traverse across a desert slope; at 2:00 p.m. the following day, after many sweaty retraverses, I found the book lying in the open, green and inconspicuous, in a place I had already passed at least four times. Note that I not only learned about putting red ripstop on green books but also confirmed yet again that ancient proverb: “A birdbook in the hand is worth twenty-two hours in the bush.”

CHIP: Boating and backpacking were for years mutually exclusive, unless as Colin observes, you consider the canoe portage a species of backpacking.

Having used a fisherman’s float tube to sample alpine lakes—with ice floating in them—I’m acutely aware not only of the weird rush of freedom I felt but also of the very real hazards. First, the cold—while float-tubing-for-science I wore a full-body drysuit that was both heavy and expensive, with a distinctly anti-recreational feel. Neoprene waders (for fishing) have the same drawbacks while offering less protection. Second, the fins you wear to propel the tube don’t give you enough power to move against the wind: I had to stroke like a Viking just to stay in place. Third, you can’t reasonably transport a pack. You can tow gear in a drybag, but if the wind comes up, forget it. And fourth, since your legs hang down into the water (in my case, far down) it’s hard to negotiate streams of any less depth without banging, bruising, stumbling, and perhaps getting caught between rocks. A float tube is okay for a short fishing trip, on small lakes, given a sharp weather eye. But it’s not reliable transportation.

In Walker III, Colin suggested that the inexpensive, light-enough-to-backpack inflatable kayaks then available were “essentially toys. And, in backcountry, dangerous toys. Any wind could quickly blow them just where you didn’t want to go. Even given exquisite care, their durability must be suspect. And if they let you down suddenly in a mountain lake or river the cold water would give you about five minutes’ survival time.

“I mention them for two reasons. People may see them and should be cautioned. And it is just possible to envision a situation in which a single, short, unhazardous water barrier, blocking off seductive terrain, might justify humping one along.”

That’s still the case, concerning discount-store inflatables—like floating tube-tents—that sadly end up plastered on rocks and shredded on shorelines. But there’s a better way to combine backpacking and paddling in one trip. Call it

To do it right, you need a boat that’s light enough to be packed, yet sturdy and stable enough to convey not only you but your chattels for some distance. I’ve seen those first-descent photos of hardpersons lugging hardshell kayaks down tooth-gritting trails. But any rigid kayak with the volume to stow much gear weighs at least 45 lbs. and is probably twice as long as you are: significant drawbacks. Folding kayaks are heavier still, dauntingly expensive, and likely to be destroyed on rock-studded whitewater runs.

The vastly improved heavy-duty (of coated fabric rather than a single layer of polyvinyl chloride) inflatable kayaks come closer to the mark: the lightest ones now weigh about 25 lbs. and are sturdy enough to carom off several thousand rocks without expiring. Aire’s Caracal I (26 lbs., $650) is a good example. It paddles nicely and you can roll it up (with the additional 6–8 lbs. of life vest, paddle, and pump) and add it to a pack with camping gear and food for several days—without red-lining, weightwise.

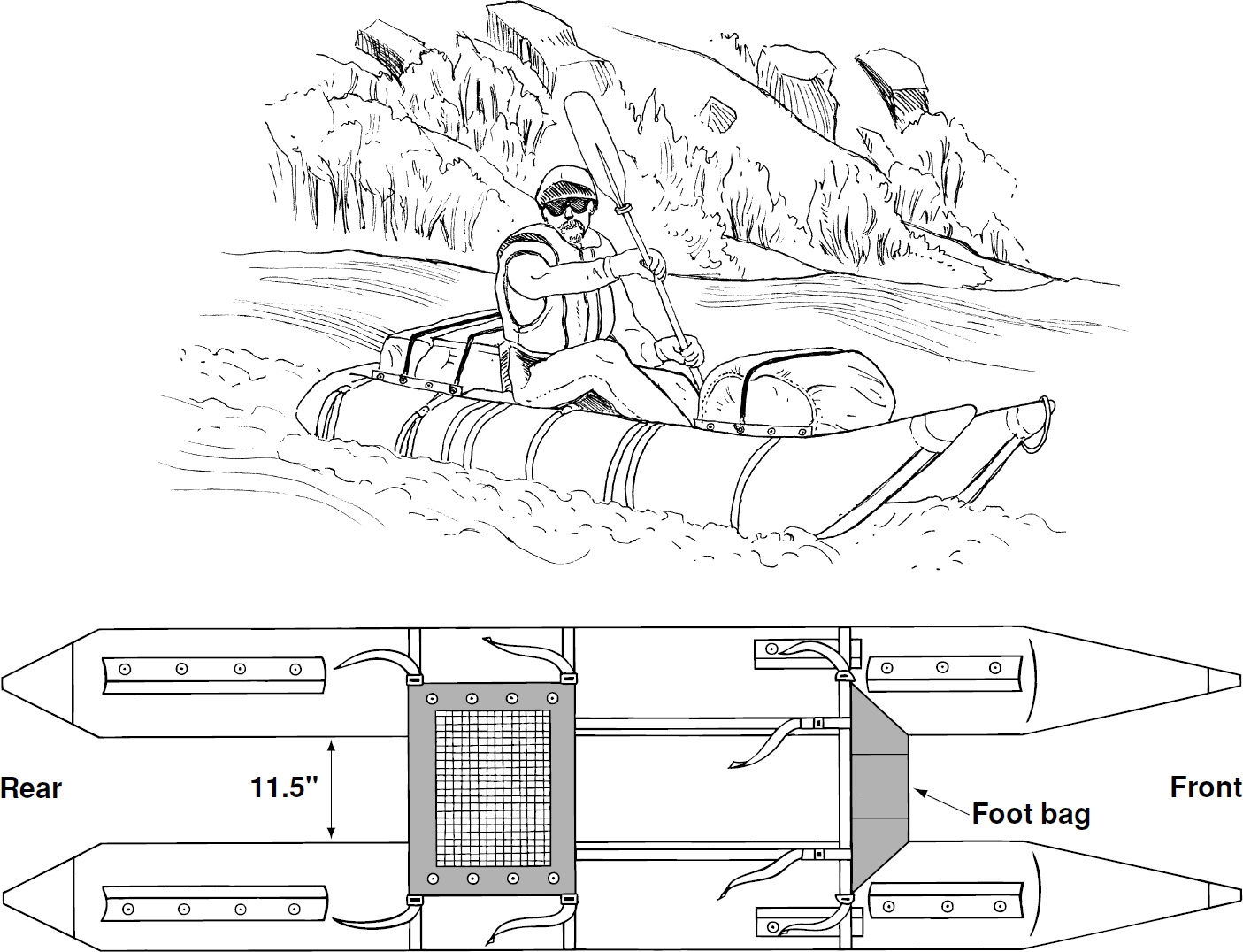

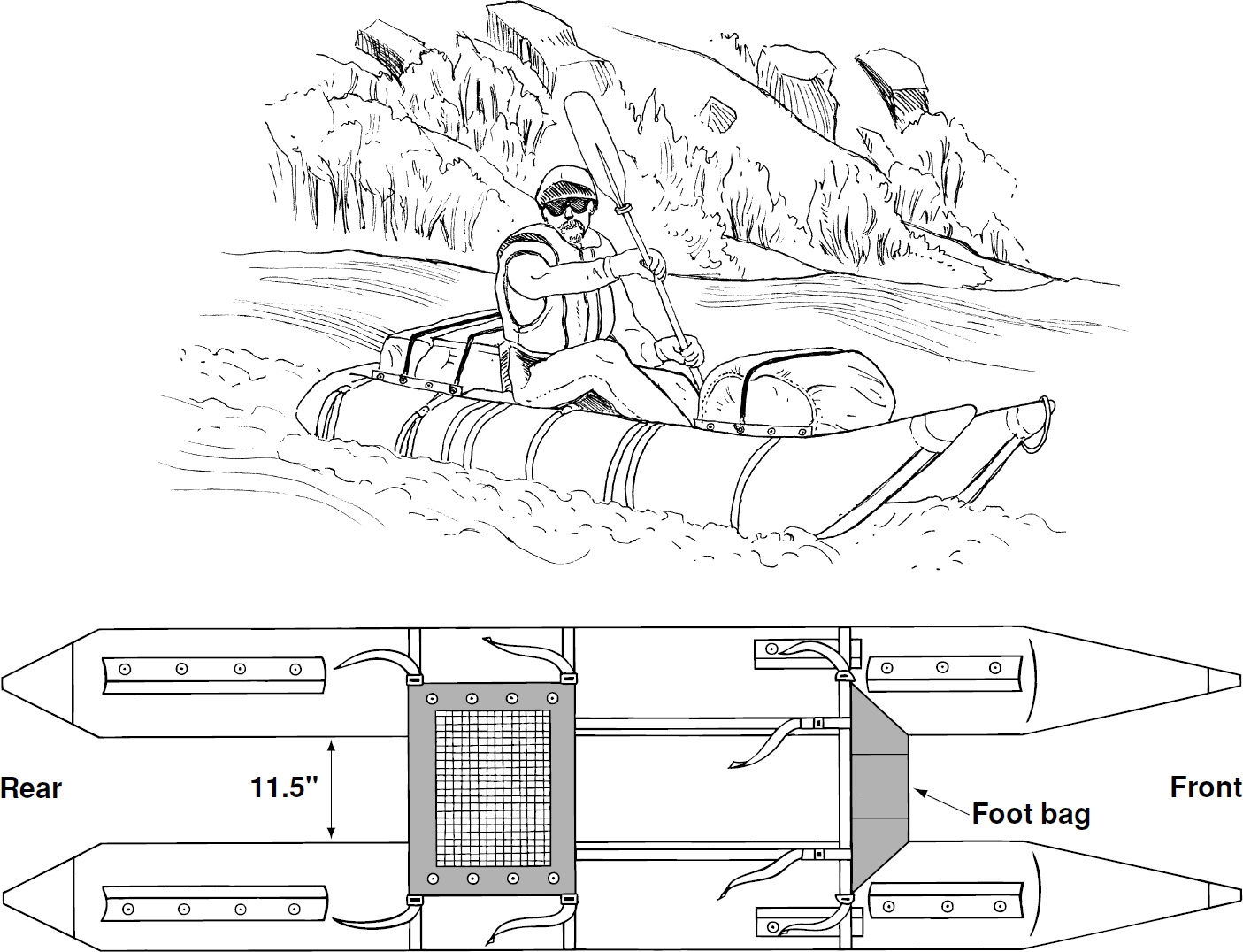

Even better for boatpacking is a felicitous hybrid known as the Jack’s Pack Cat. Developed by Jack “Paco” Kloepfer, it’s a pared-down cataraft with two 1-by-10.5-foot tubes. The two high-pressure tubes weigh 17 lbs. while the seat frame and footbar weigh 7.8 lbs., totaling 24.8 lbs. (and $935). The seat and footbar attach to the tubes with cam-buckle straps, comprising a minimalist frame. The mesh seat has an inflatable (i.e., infinitely adjustable) backrest. The footbar has a fabric guard, so you can’t get trapped. You can loosen the straps and slide both seat and footbar to adjust your body position or trim the boat. While it looks odd at first gape, the Pack Cat’s the most comfortable boat I’ve paddled—by several orders of magnitude. The two-tube design makes it strikingly stable. Add a 3-lb. kayak paddle, 2-lb. life vest, and 1.5-lb. pump, and the package is 31 lbs. I’ve carried a Pack Cat up steep trails and roared down rockbound creeks that would destroy a canoe. And you can rig a week’s worth of gear without seriously damping the performance.

Being four pieces rather one, the Pack Cat can be loaded and carried more handily than a one-piece inflatable. I’ve lugged the whole thing, plus camping gear, in a huge drybag-with-straps, and that was Sisyphean. My present tactic is to use a Coleman plastic E-frame (light, rugged, now out of production—this page) to pack the boat and a big drybag stuffed with camp gear and food. Reaching the creek I remove the yoke and waistbelt and rig the bare packframe between the Pack-Cat tubes to support the drybag. In the event I have to hump boat-and-all back up a sidecanyon to a roadhead, presto-reverso!

After backpacking across superheated slickrock and dusty sage flats, it’s heaven to reach a stream. And then, to float off downcanyon like cottonwood fluff is heaven cubed: amphibious bliss.

With the scorch marks of Colin’s fulmination on guidebooks still fresh about my ears, I’m not about to publicize my favorite boatpacking runs. You’ll hear tales, no doubt, or see things written up in magazines. But don’t be rash. Knowing how to paddle helps like mad. On rocky streams, so does a helmet. Besides poor technique, the major hazards are unexpected drops (holes and falls) and strainers (tree trunks or brush that catch boats and bodies, while letting the water through). So vigilant scouting and an occasional sweaty portage are necessary parts of the game. Meanwhile, the essence is to sit down with a map and figure out where you can boatpack into some remote headwater—and then float (merrily, merrily) on out again.

COLIN: The remaining furniture and appliances can best be departmentalized:

The old white “parachute cord” has largely been replaced by “static accessory cord”—also with core fibers and a braided sheath—in sizes from 3 millimeters ($.19 a foot) and up. It may come in solid colors or, more often, speckled; and it’s strong, low-stretch, doesn’t seem to ravel too badly when carried in hanks, and has “high knotability.”

I always carry four or five hanks, in 3- or 4-millimeter sizes, from about 2 to about 15 feet; and occasionally a 100-foot length (6 oz., $19).

No matter what lengths and thicknesses you choose to carry, remember that cut nylon always frays at the ends. To prevent fraying, simply fuse the ends into unravelable blobs by holding them briefly in the flame of match or stove. Hanks of all sizes can travel, easily available, in an outside pocket of your pack. Mine, for some reason, always go in the flap-top pocket.

Despite echoes from earlier pages, I think it’s still worthwhile listing here—tidily bundled—some of the cord’s proven multifarious uses:

• Rigging tents and allied shelters (this page)

• Clotheslines (this page)

• Fish stringers

• Measuring lengths of fish and snakes, for later conversion to figures (mark with a knot)

• Tying socks to pack for drying

• Securing binoculars and camera—or, alternatively, hat—to pack by clip spring, so that if dislodged they cannot fall far (this page)

• Belt for pants or for flapping poncho in high wind (this page)

• Lowering pack down difficult places (this page) or even pulling it up (Don’t try to pull hand over hand; bend knees, pass cord belay-fashion around upper rump, straighten legs, take in slack, and repeat and repeat and repeat….)

• Replacement binocular strap

• Chin band for hat (this page)

• Lashing tent poles, fishing rod, or what-have-you to pack

• When there’s no wire, hanging cooking pots over a fire, from a tree, for melting snow for water (This way you can build up a really big fire and keep warm at the same time. You do so, of course, in the uneasy knowledge that the cord may burn; but in practice, if you wet it occasionally, it doesn’t seem to.)

• Wrapping around a jammed camera-case screw fitting, pulling, and so unjamming the screw for film changing

• Ditto with a jammed stove stopper (this page)

• On packless side trips, tying poncho into lunch bundle (food, photo accessories, compass, etc.) and securing around waist (this page)

• Makeshift loop sling for birdbook (this page)

• On river crossings:

(a) Lashing sleeping pad to pack

(b) Lashing plastic sheet into virtually watertight bundle for protection of valuables, either as sanctum sanctorum of pack (this page) or as lone floating bundle to be pushed ahead or towed on packless crossings (this page), and

(c) Towing walking staff along behind

• Attaching flashlight to self at night with loop around neck (this page)

• Replacing frayed gaiter underpinnings

• Spare bootlaces

• Lifting water from well in cooking pot—or from deep-cut creek (especially in snow)

Among uses I’ve had in mind for years but have never had occasion to try:

• Doubled or tripled or quadrupled, as “carabiner-type” loop for ensuring that doubled climbing rope used for rappeling (or roping down) can be recovered from below (this page). Also (in extreme emergency only) as main rope for roping down low cliff: the cord might be weakened to danger point by knotting at top and by possible wear and would in any case be viciously uncomfortable even if used doubled or quadrupled.

• In river work, for pulling yourself back up against slow-to-medium river current—in case you find it necessary to float a short way past a blind headland to see if a safe land route lies ahead around dangerous rapids.

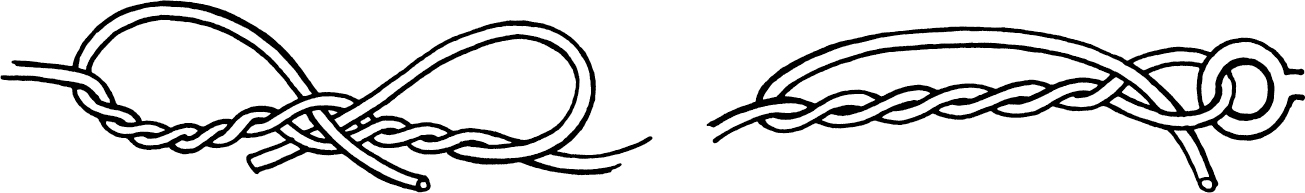

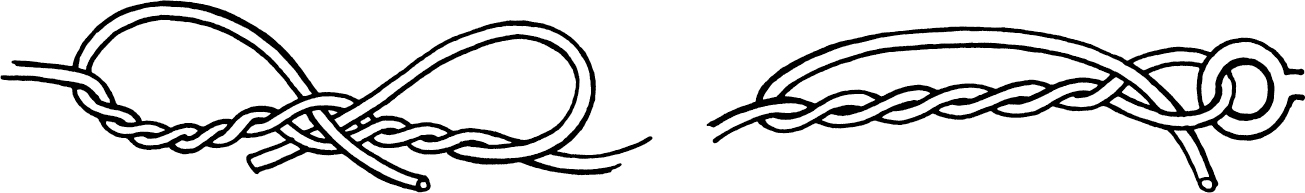

Most ordinary knots in nylon cord eventually slip. The only safe knot I know—and it’s less difficult to tie and less bulky than it looks—is the fisherman’s blood knot:

For permanent knots, burn-fuse all ends.*22

Several readers have extolled the virtues of waxed nylon

Dental floss.

Acclaimed uses include: “most everything that nylon cord can be used for—plus fishing line”; attaching line guides to fishing rods; binding around-the-neck nylon-cord loop to flashlight that lacks convenient hole; sewing thread; and toothbrush-eliminating dental care.

The only cavil: “low resistance to abrasion.”

Most easily carried, primarily for teeth, in very small, ¼-oz. plastic caddy or wrapped around a card or in one of the larger tubes that it comes in—and which make good homes for needles. To prevent slippage, burn-fuse knot ends.

For all-round usefulness, rubber bands rank second only to nylon cord. Their most vital function in my regimen is as weak and nonrestrictive garters for my turned-down socks, to keep stones and dirt out of the boots. Other uses: resealing opened food packages; closing food bags that are too full to be knotted at the neck; holding onionskin paper (for notes) to its rectangle of stiffening cardboard; and keeping notebook instantly openable at the current pages, front and rear (this page).

Rubber bands have a habit of breaking and also of getting lost, and I recommend that if you use an E-frame pack and it has protruding arms, you wrap around them as many bands as you think you need ready for immediate use. Then add the same number again. Then put into a small plastic bag about 10 times as many as are on your packframe and put this reserve safely away inside the pack. Mine go into my “office” (this page).

I sometimes wonder what backpackers used as the interior walls of their houses before the days of plastic freezer bags. I use ordinary freezer, Ziploc, and OneZip bags in various sizes, including sandwich size, not only for almost every food item, but also, copiously and often double thickness, for wrapping many other things: camp moccasins, clothes (especially in wet weather), dirty socks, cooking pots, frying pan, book, rubber bands, matches, toilet gear, first-aid kit, film, camera accessories, toilet paper, spare flashlight cells, can opener, stove-nozzle cleaner, signal flare, fishing tackle, certain spare pack attachments, tarp clamps for plastic shelter, car key, and unburnable garbage. Also, sometimes, as a wallet, and even as a stove container bag. I often take along a few spare bags. Standard marine sample bags give extra-strong protection for special articles.

For details of bag sizes and uses, and hints on packing, see this page. Ziploc and OneZip bags can double as pillows (this page). And household trash bags can serve not only as food bags, pack liners (this page), sleeping-bag protectors, foam-pad covers, and kilt (this page) but also as a poncho (with arm and neck holes cut) and even bivouac bag and emergency shelter.

The old screw-top metal film cans made excellent containers. Current clip-on-top plastic versions look distrustable and are: I had one pop open in my pack at around 10,000 feet and spread Mautz Firepaste thin but wide. I also hear reports of squashings under pressure. And their blackness makes them eminently losable—though a red encircling tape helps. For most uses I now find the very small Nalgene bottles much safer.

Among candidate items for one or other of such small containers: salt tablets, salmon eggs for bait, and oil for lube jobs on hair and beard and even boots, not to mention for cooking. Also for odds and ends, including spare flashlight bulbs (if there’s no place for them in flashlight), some strong button thread wound around a small piece of paper, and water-purifying and vitamin C tablets.

Film cans for 120 film are said to make useful makeshift matchsafes.

Swivel-mounted snap hooks on small woven nylon loops are useful for carrying certain items suspended from either your belt or the built-in waistband of your pants: a cup, in good drinking country (this page); occasionally, your hat; the camera tripod or other light equipment, on packless side trips. Formerly brass or steel, such clips now come in highimpact plastic (Duraflex with nylon loop, ⅓ oz., $2–$3), alone or as an accessory with flashlights. But they seem to have given way to very small carabiners (about 2 inches long, 1 oz., $4).

If you use a belt clip while carrying the pack (for a cup, say), make sure you pass the hipbelt inside it; otherwise the belt’s pressure may force the spring-loaded clip open. After a little while you find yourself flipping the cup outside automatically every time you put the pack on.

Strictly-personal-but-you’ll-probably-have-your-own department

Everyone, I imagine, has little personal items that go along; they’ll vary according to individual interests and frailties. Two very experienced friends of mine always carry small pliers. In addition to items I’ve already mentioned, such as “office” and prospector’s magnifying glass, my list includes spare eyeglasses (sometimes) and (always) one or two wraparound elasticized bandages, Ace or similar. The bandages are primarily for a troublesome knee and for emergency use in case of a sprained ankle, but they’ve seen most use in thornbush and cactus country, wrapped puttee fashion around my bare and vulnerable lower legs (this page).

Generally, the last thing you want to do out in wild country is to carry any item that helps maintain a link with civilization. But there are exceptions. For example, when it’s more convenient and even cheaper to fly rather than drive to and from your chosen wilderness, you have to carry, all the way, some kind of suitable lightweight

The simplest and lightest is a small plastic bag. If that dissatisfies you, look in stores or catalogs for the now-popular Cordura versions. Into your choice you may want to put, according to the needs of the moment, some form of identification (driver’s license is best, in case you need to drive), fishing license, and fire permit. Also some green money (although it’s the most useless commodity imaginable once you’re actually out in the wilderness). Consider traveler’s checks too, and perhaps one or two bank checks as reserve. A credit or debit card may also be worthwhile: I once used mine to pay in advance for a short charter flight that put me down on a remote dirt road, and also for an airdrop of food that was to follow a week later.

A little cash may be worth taking along even when you’ll be coming back to your car: late one fall, after a week in the mountains that ended with a fast, steep, 10,000-foot descent, I emerged with very sore feet onto a road 50 miles from my car, quickly hitched a ride in the right direction, and managed to persuade my benefactor that it was worth $5 for him to drive me several miles up a steep mountain road to where my car was parked.

Nowadays I always carry a few coins—in my “wallet” or taped to the cardboard stiffener of my “office” (this page) or to my first-aid booklet. Few things are more frustrating than to emerge into man-country at last with a message heavy on your chest and find yourself at a remote telephone booth, coinless and therefore mute. Not all public phones can be dialed without coins and the charges assigned to a credit card or home phone number.

The obvious place to leave your car key is at the car—taped or magnet-attached to some secret corner of it, or simply hidden close by. But I once came back from a winter mountain trip and found the rear bumper of my car, with the key craftily magnet-attached inside it, buried under a 10-foot snowdrift. Fortunately, a freak of the wind had left a convenient alley along one side of the car and I was able to get at the key without too much difficulty. After that, rather to my surprise, I found that, at least on short trips, I tended to avoid vague worries about snow and torrential rain and landslides and thieves (human and other) by packing a key along with me, even though there’s always one at the car, secreted away but attainable. Cached or carried, the key gets wrapped in the inevitable plastic bag.

Nowadays, burglar-alarm-and-unlocking remotes pose a mildly weightier problem. I find I normally pack mine along.

CHIP: So far I’ve not yet seen anyone talking to their broker on a cell phone while walking a trail—but then I don’t spend much time in Grand Teton National Park. When that unhappy event occurs, as I’m sure it will someday all too soon, I hope I don’t react with any undue savagery. Still, as cell phones get smaller and cell-phone talkers more oblivious, one begins to wonder if it would be possible to swallow one. It could happen.

Already, rangers at Mount Rainier report a growing glut of cell-phone calls from high on the mountain itself. Along with electro-bleats for rescue, there are also a great many more asking for step-by-step route information or routine advice (e.g., my stove won’t start). The problem, non-technologically speaking, is that many people call for assistance when they are not really in danger, placing an unfair burden on dispatchers and rescuers. And the concern, beyond burning out wilderness rangers—in general a solitude-loving group—is that such devices as GPS receivers and cell phones lend a false sense of security. The purpose of such electronica is to extend both our senses and our faculties. But the illusion of control, in turn, leads the techno-believers to stumble blindly into situations far beyond their experience and skill.

When I carried a Forest Service radio—exactly the size and weight of a brick—I found that to contact headquarters I usually had to be on a peak or ridgetop. I experimentally packed a cell phone on a recent trip into the wilderness where I’d rangered, to see if it was similarly ineffective. My route followed alpine valleys and canyon streams, and I found I could very seldom make a connection—I still had to climb to a ridge or peak, and have a line of sight to a receiving antenna. And if I can accomplish that—hell’s bronze bells—I don’t need to be rescued.

But with the dramatic calls from the doomed on Everest and a constant barrage of news items about dial-a-rescue incidents, the idea of the wireless phone as being a wilderness asset is now firmly embedded in the popular mind. Meanwhile, the towers required for wireless phone networks are desecrating high points all over the U.S., and demands are heard to place them in ever-remoter spots—even overlooking Grand Canyon. Networks using satellites rather than towers might solve the line-of-sight problem. But the emotional problem remains.

Being a pragmatical ape, I am not in any wise arguing about the utility of digitalia such as the tiny thermohygrometer I used to measure humidity in tents (this page). Nor am I even doubting, really, the wisdom of carrying a wireless phone for that true—and fortunately very rare—backcountry emergency. In that situation, only a fool would not use one. Rather, my objection is to the inexorable (and insidious) enclosure of our senses in an ever-present electronic net.

Even in the howlingest remoteness, you can now get a precise set of directional coordinates from your GPS receiver, as you note the exact time on your digital watch. If the watch is one of those whizbang wrist computers, you can punch through a sequence of tiny buttons to find out the altitude, barometric pressure, temperature, and number of minutes since you last found out all the same things. But then what do you have?

You’ve got data—for the most part, numbers. Electronic gadgets are great at spewing numbers: you can, if you wish, record the air temperature at one-second intervals, with extreme precision. And by the same time the next day you have 86,400 extremely precise readings: a choking mass of data. But data, however useful, is not the same as experience.

Most of us who leave our homes to undertake long walks do so for the sake of experience. Of course, bellying down on a shag carpet in front of a television is also experience. So what we are seeking is not the mere passing of time, but something deeper. We seek the experience of walking, of course. But go to any city park and you can see your fellow citizens power walking, a sort of revved-up military march—around and around the asphalt strips that circle the close-cropped grass, and around.

So, healthful and virtuous as it may be, the physical act of walking itself is not the object.

The walk for which we go to such ends to undertake is not the dutiful circumambulation of a gym or a park, nor yet the preoccupied stroll of the window-shopper. Rather we choose a place that is passable yet only lightly marked by human works and pomps: seminatural, or perhaps comfortably wild. Our object in this is not that it passes us by like a movie, untouchably. Rather we hope that as we walk our chosen place will act on us in turn—a light wind at dawn, the scent of pine pitch, the roar of the creek.

When you’re data-fying—checking a set of coordinates, a bearing, an altitude, a temperature, a barometric pressure—in physical point of fact you’re hunched over staring at digits on a tiny screen.

If you step off the trail to unfold your pocket computer and uplink through your cell phone to check your e-mail for a message from your broker, your heart is a thousand miles away.

And the wilderness can have no part in you.

*1Our weights for flashlights, headlamps, etc., all include the weight of the necessary batteries. For purposes of comparison, we’ll choose mercury-free alkaline cells (Duracells, Energizers). But batteries vary in weight, storage capacity, and so forth—see this page.

*2The OEM (original equipment manufacturer) sections of company Web sites often contain such things. Duracell’s OEM site has a marvelous glossary of battery-related terms, but you can’t print it out.

*3The Rechargeable Battery Recycling Corp., a nonprofit company funded by battery makers, has a list of stores and drop-off sites for spent nicads: 1-800-8-BATTERY; e-mail—<rbrc@rbrc.com>; Web site—www.rbrc.com.

*4CHIP: Opticians are now able to supply bifocals, trifocals, and continuous-focus lenses—I have a type called Vari-focals—with full UV/IR-proof coatings in both glass and plastic. The custom lenses are in a French nylon frame labeled BREVETE SDGD that has stood so many years of daily use that it is now “retro,” or so I’m told. The new domed, rainbow-hued wraparounds with polycarbonate lenses increase peripheral vison while making you look like a predatory insect. Some of these are adaptable to corrective lenses, at extra cost. Multisport goggles, while good for biking, skiing, and paddling, tend to become tiny steam chambers while backpacking—on me at least.

*5CHIP: Ultraviolet radiation is now sorted into three types: UV-A, UV-B, and UV-C. Both glass and polycarbonate lenses can absorb 100 percent of all three UV frequencies. While glass can also block 100 percent of infrared (IR) as well, the best polycarbonate lenses only block about 75 percent.

*6For consistency, all prices I’ve quoted here—and later for cameras—are “list.” But list prices in this field are a chimera. Almost anywhere, anytime, you can buy “name” instruments at 30 or 40 percent below list (except that the higher-quality units tend to be more like 20 percent off). This is known as merchandising. In other fields, parallel behavior is labeled bullshit, stupidity, or deceit.

*7Do not underestimate the importance of such a bursting free. There is a cardinal rule of travel, all too often overlooked, that I call The Law of Inverse Appreciation.

It states: “The less there is between you and the environment, the more you appreciate that environment.”

Every walker knows, even if he hasn’t thought much about it, the law’s most obvious application: the bigger and more efficient your means of transportation, the more severely you become divorced from the reality through which you’re traveling. A man learns a thousand times more about the sea from a kayak than from a cruise ship; euphorically more about space at the end of a cord than from inside a capsule. On land you remain in closer touch with the countryside in a slow-moving old open touring car than in an air-conditioned, tinted-glass-window, 80-miles-an-hour-and-never-notice-it behemoth. And you come in closer touch on a horse or bicycle than in any car; in closer touch on foot than on any horse or bicycle.

But the law has a second and less obvious application: your appreciation varies not only according to what you travel in but also according to what you travel over. Drive along a freeway in any kind of car and you are in almost zero contact with the country beyond the concrete. Turn off onto a minor highway and you move a notch closer. A narrow country road is better still. When you bump slowly along a jeep trail you begin at last to sense those vital details that turn mere landscape into living countryside. And a few years ago, on the East African savanna—where it was at that time not considered destructive to drive cross-country over the pale grasslands—I discovered an extending corollary to my law: “The farther you move away from any impediment to appreciation, the better it is.”

These secondary discrepancies persist when you’re traveling on foot. Any blacktop road holds the scrollwork of the country at arm’s length: the road itself keeps stalking along on stilts or grubbing about in a trough, and your feet tread on harsh and sterile pavement. Turn off onto a dusty jeep trail and the detail moves closer. A foot trail is better still—and a barely discernible one far better than a trampled wilderness thoroughfare. But you don’t really break free until you step off the trail and walk through waving grass or woodland undergrowth or across rock or smooth sand or (most perfect of all, in some ways) over virgin snow. Now you can read all the details, down to the finest print. They differ, of course, in each domain. Drifting snow crystals have barely begun to blur the four-footed signature of the marten that padded past this lodgepole pine. Or a long-legged lizard scurries for cover, kicking up little spurts of sand as it corners around a bush. Or wet, glistening granite supports an intricate mosaic of purple lichen. Or you stand in long, pale grass and watch the wave patterns of the wind until, quite suddenly, you feel seasick. And always, in snow or sand or rock or seascape grass, there is, as far as you can see in any direction, no sign of man.

That, I believe, is being in touch with the world.

*8I actively sought criticism of and counterarguments to this section. On the whole I was pleasantly surprised. For example, the two friends who rose up in arms against my open-fires denunciation (this page) both endorsed this one. “It rests in my gut warmly and well,” wrote one of them. “At this time, when the regulatory agencies—Park Service, Forest Service, etc.—are progressing rapidly towards a requirement of designated campsites and rigid itineraries, the philosophy you present here and in the section on maps very much needs equal time.”

A request for counterarguments to a leading publisher of trail guides—before this section was written—unfortunately elicited only points that to me seem either to apply to backpacking books rather than trail guides (“guides raise the level of hikers’ ecological awareness…help develop a reverence for the wilderness…help in the fight to defend the land”) or to cling blindly to the straight-line, man-world coordinates (“guides help hikers enjoy the country more by acquainting them with the flora, the fauna, the geology, the history, etc. of the places they go…help the Park and Forest Service get their messages to users of their lands by listing rules and regulations”). Another argument was: “…guides spread out hikers…help prevent the ruination of the best-known places by all these new people.”

But another author of trail guides made a cogent point. “I spent a great deal of deliberating time before writing the first guide,” he wrote. “I ultimately concluded the choice lay between the North Cascades being logged, mined and otherwise resource-extracted vs. being used or, if you will, overused recreationally…. It seems that most of our current decisions involve choosing the lesser of two evils rather than choosing between black and white…. In my opinion, only enough people who are aware of an area have the political clout to keep it reasonably safeguarded.”

On the other hand, Michael Parfit, writing in the New York Times Magazine in 1976, described guidebooks as “fine for daydreams, but destructive of mood and mystery in the manner of fluorescent tubes hung in catacombs. This way, ladies; please mind the abyss.”

Readers’ opinions on this section in earlier editions have varied.

One—who violently opposed my views on hunting (this page)—supported me. He compared a dedicated trail-guide user to “the poor soul who can only look at the woods through his camera viewfinder.”

A Texan admitted equivocality: he recognized that trail guides could “help keep novices out of trouble.”

An Easterner protested that trail guides perform a necessary function in such places as the Appalachians, where trails mostly follow crests and water is rare and secretive. Maybe. But surely a map would do the job at least as well? And a map, though undeniably based on man-world coordinates, can be a wonderful and tickling thing.

Two friends suggested—with reason, I think—that a trail guide is a boon to a family on its first trail trip. But “perhaps Daddy could use the suggestion that he keep his burden of information under his own hat so as not to diminish the joys of exploration and discovery for the small fry.”

And a stern but valued critic wrote: “It seems to me here that you fall into a particular trap: you’re confusing the elements of a how-to book with your own idiosyncratic way of dealing with the world.” Sure.

Chip, I’m relieved but hardly surprised to learn, votes as I do.

*9CHIP: I call this the “grain” of the country, like the pattern grown into wood. The overlapping intricacies of bedrock, drainage, landform, weather, plants, and animal life are as fascinating and variable as music, or human personality. If you can sense the grain of the country—lucky for you—you tend to avoid the traps and trials of those who can’t, or won’t.

*10“Yes, Aunt Josephine, the sun rises in the east. Well, kind of in the east. In summertime, if you’re well north of the Equator, it’ll actually rise quite a ways north of east. And in the winter, quite a ways south of east. In flat country, anyway. But at noon—standard time, not daylight saving—it’s always due south. Unless, of course, it’s overhead. No, that isn’t very helpful, is it? And if you’re in the Southern Hemisphere it’ll naturally be due north at noon…. Yes, Auntie, unless it’s overhead…. And yes, you’re right again, it always sets in the west. Well, kind of in the west. In summertime, if you’re well south of the…”

*11CHIP: I just spent a week in an obscure and precipitous canyon where so few humans have gone that the trails are free of engineering talents—except those of moose, elk, and deer. Despite having to high-step or duck under fallen trees (back scratchers for elk) and wade soggy spots (moose trails run from bog to bog) I found passable trails going practically everywhere that I wanted to go. A general principle: animal trails blunder through endless petty irritations and undertake seemingly aimless detours in order to skirt major problems, like V-cut stream gorges and bottomless talus fields. That is, they tend to piss you off while keeping you out of real trouble.

*12If this little scene seems familiar, maybe you’ve read The Thousand-Mile Summer.

*13COLIN: I just hate having to report that I’ve found the effect of herbal and other natural repellents on really mass mosquito attacks to be approximately nil.

*14CHIP: Inspired by the hand-carved gear of Costa Rican fishermen, the Tidelands Casting Handline (that weird object above the ice axe in the cover photo) is a pocket-size goodie in fiberglass-reinforced plastic with a rubber handgrip. After practice I could cast farther and retrieve more easily than with the short pine stick I formerly used—with the potential to land larger fish. It’s made by Streamlines (see Appendix III) and comes with 140 feet of line and a practice plug (2.5 oz., $17).

*15CHIP: This is tempting, when you come to one of those overhanging rims with a gorgeous canyon opening below. But before slithering down, remember that you can’t rappel back up. Further, overhangs are tough to surmount even for a practiced climber with a partner to belay (or winch) you up. A great many people get badly stuck this way. For the highly relevant details of descending and ascending ropes, consult a mountaineering text. And get some hands-on-rope instruction.

*16CHIP: My reading tastes are impossible to track, let alone predict. In the Poetry Department, though, some favorite companions have been: Cold Mountain: 100 poems by the T’ang Poet Han-Shan, translated by Burton Watson (Columbia University, 1970, 4.5 oz.); the Iliad and the Odyssey, Homer, translated by Robert Fitzgerald (Anchor, 1974 and 1963, about 500 pages and 10 oz. each); Narrow Road to the Interior by Matsuo Basho, translated by Sam Hamill (Shambhala, 1991, 108 pages, 3.5 oz.); The Essential Clare: Poems of John Clare, selected by Carolyn Kizer (Ecco, 1992, 4 oz.); the Laurel Emily Dickinson (Dell, 1960, 3 oz.); and 100 Great Poems by Women, edited by Carolyn Kizer (Ecco, 1995, 8 oz.).

*17CHIP: A compact deck of playing cards (also needed for cribbage) lightens stormed-in sojourns with solitaire or high-stakes games of poker for M&M’s, lemon drops, or sips of rum. Dice also provide weight-efficient amusement (with knife fights optional). For ramblers who aren’t gamblers, wholesaler A-16 carries jacks, marbles, pick-up sticks, juggling games, and such. For aggravation games such as Headlamp Tag and Scarf-the-Gorp, see Sky’s Witness: A Year in the Wind River Range.

*18CHIP: The margins or backside of a topographic map are a grand place for trip notes, drawings, and poems, at least for pencil scratchers like me. Transformed by art, the map becomes a topo-keepsake.

*19The problem with such micro-devices is remembering all the modes and subroutines. I’ve been on trips with persons whose digital wonders were set for alarms at odd times, and they couldn’t remember how to shut the damned things off.

*20CHIP: Colin asked what I fish with. I’ve done well enough hand-lining small creeks with a piece of leader and a stick, or more recently a Streamlines casting hand-line rig (this page, first footnote). But for serious fish-hunting I take a Sage Graphite II 4-piece fly rod, 9 feet long, that takes a 5-weight line and a Sage #106 reel (6 oz., with line), given to me as gifts. The rod and cloth case weigh 5.5 oz., and I often carry it thus, with a stout rubber band top and bottom to hold the bundle tightly together. I slip it down the side of the pack, under the compression straps and into the wand pocket, or employ the ice-axe loop and strap, aft. I’ve also packed it in the slim nylon bag with tent poles. All I can say is that I haven’t broken it yet. The aluminum-tube case weighs 12.5 oz., and I take that only when I expect to be bushwhacking—but always use it for transport in cars.

*21Echo trouble, you say? Maybe. See The Winds of Mara, page 190.

*22CHIP: We once again considered a section on knots for all backpacking uses but rerejected the idea. It seems safe to say that people are either fascinated or turned off by knots. If you’re fascinated, some basic books are: The Essential Knot Book by Colin Jarman (McGraw-Hill, 2000, $10); Knots for the Outdoors by Cliff Jacobson (Basic Essentials, 1999, $8); or The Book of Camping Knots by Peter Owen (The Lyons Press, 2000, $13).