Ground Plan

COLIN: As long as you restrict your walking to one-day hikes you’re unlikely to face any very ponderous problems of equipment or technique. Everything you need can be stuffed into pockets or if necessary into a convenient little pouch slung from waist or shoulders. And if something should get left behind, why, home is always waiting at the end of the day’s road. But as soon as you start sleeping out you simply have to carry some kind of

A house on your back.

Obviously, there’s a difference between the kind of house you need to carry for a soft, summer weekend in the woods and for a month or more in wild mountain country. But it’s convenient and entirely possible to devise a standard structure that you can modify to suit a broad range of conditions. In the first two editions I tried to instruct mainly by describing in detail the fairly full-scale edifice, very simply modifiable, that I had evolved over a considerable number of years. If some of the architecture seemed too elaborate for your needs, all you had to do was simplify toward harmony with those needs. By the third edition, things had grown more complicated. An avalanche of new equipment meant that my house tended to get more markedly modified for different kinds of trips. And I was more likely to switch from one kind of pack to another—thereby altering not only what went inside but some details of how I operated. As in earlier editions, I discussed most techniques as they applied to trips of at least a weekend, and often in terms of more ambitious journeys. Again, if my suggestions were too intricate for what you had in mind, you simply simplified.

Basically, this method stands. But for the packful of reasons I’ve listed in the preface (this page), most current specifics will in this edition be written by Chip Rawlins, and will describe his gear.

In spite of these changes, the book remains highly subjective (well, bi-subjective)—and therefore should give many experienced walkers a whole slew of satisfying chances to snort with disagreement. I make no apologies. Backpacking is a highly subjective business. What matters to me or to Chip is what suits us, individually; but what matters to you is what suits you. So when we describe what we’ve found best, try to remember that we’re really saying that there are no truly objective criteria, and the important thing in the end is not what we or other self-styled experts happen to use or do, but what you find best. Even prejudice has its place—a technique or piece of equipment that you’ve devised yourself is much more satisfying to use than an “import”—and in your hands it may well prove more efficient. In fact, the whole game lacks set rules. Different backpackers, equally experienced, may under the same conditions carry markedly different gear. And I’m always being amazed at the very wide variation in the ways people operate. Again, one of the most important things for a backpacker to be able to do is extemporize—mostly in the field but sometimes also in planning. And extemporizing is something that can’t really be taught—though the right mind-bent can, I think, be encouraged. Given all this, then, the most a book can do is suggest guidelines.*1

Guidelines are all we can offer for another reason too:

The current state of the mart.

In 1968 I wrote in the first edition that backpacking was “in a stimulating if mildly confusing state of evolution—or perhaps I mean revolution—in both design and materials” and also in distribution methods. In the second edition I noted that “the ev- or rev-olution continues.” By the third edition the process had spun into high gear. Boot making had begun to throw off century-old traditions. Cold-weather clothes were slanting out in new directions. So was raingear. And almost all fabrics—for tents, sleeping bags, and packs as well as clothing—were stronger and lighter and came with more effective coatings. Drastic changes had swept through the peripheries too, from compasses to flashlights.

For this edition, change has shifted into overdrive. So our choices and practices are, like everybody’s, in a state of flux—and some of our solemn, carefully updated advice will soon be outmoded again. But that matters less than it may seem to. Although we’ll often be describing specific items, the essence will once again lie not so much in the items themselves as in the principles that govern choice—those vital factors an intelligent backpacker should keep his or her eyes skinned for.*2

After Walker III appeared, a Utah reader of earlier editions reported that he had already made several of the changes to new equipment that I’d now suggested. “See,” he wrote, “you were successful in teaching not just specifics but the underlying function of equipment and the ideas behind choosing it.”

Custom suggests that we avoid trade names. But only by discussing brands and models can we adequately indicate the details. And if we recommend one pack or jacket over another it’s because we find it suits our needs better, not because, for crying out loud, we’re mad at Mr. Madden or starry-eyed for Ms. Moonstone.

And now, gratefully and thankfully, over to

CHIP: When Colin and I first theorized about this update, we despaired somewhat. That is, the sheer range of outdoor gear available is stunning, though if you’re trying to describe it comprehensively, “daunting” is a better word. In the last decade, not just the amount but also the rate of change has accelerated. Boot making leapt away from leather and tradition and has since made a partial leap back. Some raingear now s-t-r-e-t-c-h-e-s. New cold-weather clothes make lightweight winter trips (once oxymoronic) a brisk possibility. Whole classes of things such as water filters have flashed into existence and are diversifying into subclasses. And what one reader calls DMS (Digital Madness Syndrome) has added global positioning units, cellular phones, and electronic watches that also perform as alarms, timers, altimeters, barometers, compasses, and address books.

To get a feel for this, let’s start at ground level. When the Complete Walker was first issued, I rushed out to get boots with soles made by Vibram, the original waffle-stompers. There were two sorts: the Montagna and the Roccia. I chose Montagnas. Now the Vibram flyer on my desk lists 32 different flavors. Besides the Montagna and Roccia (chocolate and vanilla), they range from the flattish #7510 Grip (for optimum traction) to the toothy #1450 Clusaz (a highly technical self-cleaning style for aggressive outdoor hiking). And these 32 soles are only a small part of what Vibram now offers.

In matters of gear, my practice was to swap with friends, dig deep in bargain bins or find part-time work in an outdoor shop to gear up at a discount. Thus, I tended to acquire things that were returned, scuffed, discontinued, or oddly colored, and to hang on to them until they were thoroughly tattered, bent, and delaminated. That’s still my basic instinct.

But for purposes of this book, I had to augment my usual process of slow-destruction-in-the-field and explore the terra incognita of New Stuff. To be honest, I get a buzz in the presence of New Stuff. So at first the trade shows were like bushwhacking the American Dream. I fondled Eco-fleece and Powerstretch, hitched hipbelts and crawled into tents, and got a howling bellyache from bulk latte and free samples of energy bars. And each day I stuffed my faithful, faded Lowe pack with what salespersons are wont to call “literature.”

I returned from that first show with 135 lbs. of catalogs, workbooks, and flyers. At the second show I pulled on seams, counted stitches, and cut the “literature” load to 60 lbs. By the third, a reaction had set in: I was tired of seeing New Stuff. After that, I found excuses not to go (and avoided a tornado that struck the trade show in Salt Lake City in August 1999). And I also returned to familiar ground: the fact is, even the most dedicated walker can break in only so many pairs of boots and still have feet left to walk on. So how can any one person hope to keep track?

Don’t worry about it. To keep track is human—to make tracks, divine. As Colin observes, the essence lies not so much in a thing itself as in how it fits into your life afoot. So rather than trying, theoretically at least, to cover the universe of gear (for publications that attempt this, see this page), instead we’ll focus on how you can assemble (or refurbish) your portable house in a coherent way. There are decisions to be made at the outset. Just as even the most perfectly built igloo will never be much use in the Sonoran Desert, so some suites of gear are suited to a certain climate or landscape. And your own character and bent are crucial—some of us are minimalists by nature while others are maximalists or even hypermaximalists. Given your chosen landscape and yourself as benchmarks, the choices are not so difficult as they may seem.

When I was inspired by the first edition of this book to take up a staff and stride forth, most equipment was made and sold by backpackers with a knack for design who learned business as a necessity. Some owned shops, like the original Ski Hut in Berkeley, or were mountain guides. By the third edition that was not necessarily so. Success had forced many into roles as manufacturers and executives. Some, like Patrick Smith, “founder and grand pooh-bah designer” who has parted from Mountainsmith, still spend much of their lives outdoors. But the companies have passed into other hands. For instance, Mountainsmith now belongs to Western Growth, a venture-capital firm. Likewise, the present “outdoor industry” employs ranks of perfectly decent yet thoroughly un-outdoorsy folk. Thus, at trade shows one hears more of “high-touch shoppers,” “specialty doors,” and “big-box shifts” than of wild weather and narrow escapes.

COLIN: On a purely intellectual level, of course, results have often been beneficial. Fierce competition has generated more varied products of keener design at a larger number of sources. Technological and workmanship standards have, by and large, risen to new high levels. The pressure is so great that virtually every product niche has been filled and you’re pretty sure to be able to find something appropriate to your particular needs. In fact, it’s now easy to find good equipment, while to pick up really bad stuff you almost have to put your mind to it, at least in reputable “mountain shops”—that pleasant and useful misnomer for “backpacking stores.” Of course, some models are better than others—and probably more expensive. In other words, we are better served—economically, anyway. This state of affairs is known, I understand, as capitalism. And the organizations that implement capitalism inevitably reflect, in their natures and structures, the sea changes of the past decade (though “reflect” may possibly be the wrong word). I don’t mean only internal adjustments, such as a growing tendency to concentrate corporate energies on production and to rely for technical design, especially of such complicated items as tents, on outside consultants—who may also design for competitors. The most far-reaching change has been the rush to conglomeration (aka merging). The accelerating rush. Rumor has it that AOL Time Warner already plans takeovers of Microsoft, Madagascar, Wales, and Asia.

CHIP: The trend has spread as business in general has globalized (or perhaps “globularized” is a better word). It’s not just the decisions made by profit-minded CEOs who wouldn’t be caught dead with a backpack, but a deeper and more fundamental separation. Recently I set up a new tent and found what I first thought was excess dark thread sewn into the seams. But this turned out on closer inspection to be someone’s long black hair. Did it belong to a woman supporting her children, or a young farm girl from the hills of southern China? What was her life like? Where did she sleep? I spent part of that long winter night thinking hard about the effects of globalization on human beings.

For the sake of fact, I visited a local shop to find out where gear comes from these days. Going From the Skin Out (FSO), much of the underwear and insulating fleece was made in the U.S. (or overseas possessions thereof), and likewise the socks, except for some excellent ones from Northern Ireland, with much of the wool coming from New Zealand. Shorts, shirts, and midlayers had a mix of U.S. and Far Eastern origins. The parkas and shell pants were made in China, Taiwan, and Bangladesh. Shoes and boots were by far the most polyglot: Italy, Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania, Morocco, Korea, Vietnam, and China. Packs were made in the U.S., Canada, Korea, and Indonesia. Without exception, down sleeping bags were made in China, with some synthetic-fill bags from the U.S. The tents were split between Taiwan and China. Thus, we backpackers are as globalized as anyone else, and should face up to it.

Another long-playing irony has been the effect of the outdoor industry on the outdoors. Over the years some companies have tried hard to reduce their environmental impact, and among them Patagonia deserves particular credit for tackling this in a straightforward way, with reports in their catalog. The effort has met with some genuine success. Fabric mills now use recycled soft-drink bottles to spin synthetic fleece and seek out dyes that aren’t active poisons—in the U.S., Japan, and western Europe at least. But since the conversion of private costs into public liabilities is one of the cornerstones of capitalism, some firms have relocated their toxic habits to the “developing world.” And those at companies that have spent millions to clean up their acts are disheartened by a general lack of recognition, let alone practical support in the form of sales.

But rather than speaking in general terms, let’s look at two companies known for their excellent gear, and two different approaches to the capitalist game.

The North Face started out as a Berkeley, California, shop run by two backpackers who made some of the packs and sleeping bags that they sold. Their gear gained a devoted following, which over the next 20 years grew to national and international proportions. But as the present CEO, William Simon, told the New York Times, “They were dedicated to making good products, but they weren’t profit-oriented.” So the company passed through various hands and in the early 1990s was sold in a management-backed buyout. In 1996, The North Face raised $56 million with the sale of stock, which was used to pay debts and build a test lab with chambers capable of producing rain, hail, snow, winds, and temperatures of −40°F (as the outdoors is rumored to do). The firm also moved its basecamp from Berkeley to Carbondale, Colorado, announced a new footwear line, and bought up La Sportiva, the highly esteemed maker of mountain boots.

I used North Face packs during seven years of wilderness monitoring and found the quality superb. You could stake your life on their tents, and I did. So while I hoped to test some new gear of theirs for this book, my letters went unanswered and I never made it through the automated phone system. At the trade show they ran the door to their large display room like a border post. So—I gave up.

The Times quotes Bob Woodward, who started out in Berkeley with Sierra Designs and who now publishes an outdoor trade newsletter, as saying that The North Face “is going as fast as it can to become a street apparel company.” Tents such as the VE-25 are still in the lineup, along with functional packs and other “real” gear. The company has a sterling record of honoring warranties, fixing, and replacing. But the bottom-liners who make decisions seem to be slouching toward fashions with the “outdoor look.”

Under a photo of a squeaky-looking chap barking into a cell phone, the New York Times also quotes Ed Schmults, formerly at Patagonia, now president of Moonstone Mountaineering: “The industry is in a particularly aggressive process of change right now. It’s an attractive market, and the big-money companies see an opportunity here.” Unsurprisingly, outfits such as Polo Ralph Lauren and Tommy Hilfiger are busily cranking out parkas, fleece vests, hiking boots, and even backpacks. Is the stuff any good? According to Kristin Hostetter, equipment editor for Backpacker magazine, the answer is mostly no. Among outdoor hard-liners, fashion is known as the “F-word.”

If commuters choose to look like Everest climbers, at considerable expense, neither Colin nor I dare say them nay. But here’s the rub: the entry of the Fashion Monsters into the field might skim the cream from the market, the cream being those who dash out to buy high-end products at full retail price. And this skimming makes it harder for the companies that make real gear to survive.

Are we at the mercy (such as it may be) of a decreasing number of corporate leviathans? Generally speaking, yes. But perhaps not in every case. Here’s a counterexample. In 1974, Mike Pfotenhauer and Laurie White started making custom packs under the Osprey label. I saw a few on the trails—plain old blue, but with a distinctive cut. By 1986, Osprey was wholesaling packs to shops, with competitors offering to buy the company. This is the route taken by many owner-designers: build it up, then cash it out. But instead, Pfotenhauer moved to Colorado, hired a small group, mostly Navajo, to sew packs and then settled in for the long haul.

In April 1998, I visited Osprey headquarters in Dolores. Up front, in a room with zero decor, I met the sales crew. They were getting ready for a meeting that would be held out of backpacks in a remote sandstone canyon. Despite the crunch, marketing manager Erik Hamerschlag took me back to the cutting room. Likewise zero-decor, it held huge tables flanked with bolts of bright fabric, sheets of foam, and hanging patterns. A computer program fit the patterns like puzzle pieces into the width of the fabric, to cut down on waste. The cut materials were trucked down the hill to the plant in nearby Cortez. Operating over short distances and on a monthly schedule, Osprey’s staff could respond quickly to shifting demand. That was better, Erik said, than having to hustle huge advance orders, with the production work contracted overseas a year or two ahead. At Osprey, if someone came up with a bright idea, they could change an existing design at relatively short notice.

We returned to the front, where a striking young woman wobbled on platform sandals, clutching a sheaf of scrawled lists and getting things set for the campout. “Time to go,” Erik said, and sent me down the hill to the plant. It was a nondescript sheet-metal building on the outskirts of town, where another Erik, Erik Wegener, walked me through. We began where the fabric was unloaded and traveled in handcarts to clusters of sewing machines and assembly tables. Most of the workers were women, Navajo and Ute, and they were friendly and talked in an unconstrained way. Others listened to portable radios. It seemed a decent place in which to work.

As I watched the pieces become packs, one woman showed me a trick she’d developed in order to sew a hipbelt more easily. Farther along, someone was cutting a piece of foam. “This is Mike,” Erik said, introducing me to Mike Pfotenhauer, the founder and CEO.

Folding, peering, and trimming off minute slices, he was figuring out a way to cut the pads for a hipbelt so that when it was stitched it would take on a complex curve, like molded belts that cost a great deal more to produce. Besides the hands-on design process, he explained, they’d devised ways to use common pieces in several different packs and to streamline the physical work. So, despite their sophisticated design, the packs were simpler to make.

Finally, Wegener took me to his own area, where finished goods were lined up on ceiling-high racks. “We ship tomorrow,” he said, “and this’ll be a madhouse.” Osprey, he explained, had gained momentum quickly, and they were operating at the limit. Later, on the phone, Erik Hamerschlag filled me in. Rather than going offshore to “sourcing” companies or assuming the debt for a large, new plant they’d decided to hold the line through other means: “Our dealers hang banners and our packs get reviewed. But at this point we aren’t placing ads.” That’s hardly the sort of thing one expects to hear from a marketing manager.

In the Osprey catalog, everyone, from Mike Pfotenhauer to the cleanup crew, fits without crowding into a single photo. The differences between The North Face and Osprey are many, but the crucial distinction in my mind is that one has become a global enterprise while the other is still a maker of packs.

But—while I like dealing with small to midsize companies, I can’t say that “small is beautiful” as far the gear itself goes. As Colin has observed over the years, size, success, and quality don’t necessarily bear a consistent relation to one another.

Just as gear has changed, so have the paths by which it travels from maker to walker. And given the burst of computer commerce, these promise to shift even more quickly in the near future. My preference (perhaps sentimental) is to step into a local retail shop like Trailhead Sports in Logan, Utah, where I worked part-time. I like looking someone in the eye, asking questions, and arguing the fine points. The enduring virtue of the independent, local shop is that those who work there tend to be active hikers.

But times are increasingly tough for such local havens. One reason over the years has been mail-order catalogs, which have the advantages of buying in quantity and not having to maintain a retail store. More than once, I had people come into the Trailhead to try on a parka or pack and then breeze out, announcing that they could get it from a catalog for 10 percent less.

Recreational Equipment, Inc. (REI), one of the largest catalog sellers, began in 1938 as a co-op for Seattle climbers who had trouble getting quality mountain gear. When I joined, about 1970, the co-op had a catalog that offered packs, tents, and so forth from makers like Sierra Designs. There were also REI-brand products that tended to be sturdy yet Spartan: my first good sleeping bag was an REI Skier on which I gladly blew my food budget for two months, having nearly frozen to death in one of those flannel hunting-dog sacks. Good gear at a reasonable price continues as an REI staple, but under the leadership of a former Sears executive, the co-op embarked on the Way of Hugeness, extending its mail-order reach and opening retail stores (50 at last count). It has also engulfed a number of the companies that supply it with gear. And these days, the opening of a new REI outlet often signals the closing of independents.

A related trend among high-end makers is a shift from distributing only through backpacking (or specialty) shops to “big-box” sporting goods chains, which can command discounts in return for huge advance orders. While it boosts short-term profits, the practice is likely to hurt, if not kill, a great many specialty stores. One populist (and encouraging) trend is the appearance of stores selling “recycled” backpacking gear, though the amount of unscuffed gear for sale is perplexing.

Other long-running channels for backpacking gear include the colossus of the East, L. L. Bean, the Campmor catalog (still in endearingly trashy black-and-white), Canada’s Mountain Equipment Co-op, and Japan’s Snow Peak (for addresses, see Appendix III). Meanwhile, some local shops have expanded their reach with ads in national magazines and with mailings of flyers and catalogs. Some also produce their own gear. Others, such as Sierra Trading Post, focus on overstocks, seconds, or surplus. Along with its regular on-line catalog (which reported a “fivefold increase” in sales for 1998), REI has started its own Web site outlet, as have many other makers and suppliers of outdoor gear.

Sales via backpacking catalogs are still climbing, but the catalogs have changed noticeably. Besides daydream potential, a catalog should display tables of weights, volumes, boiling times, and such. But these comparative tools are now perishingly rare, having lost out to ever-glossier photos and fatuous sales pitches.

Another tack has been taken by Eastern Mountain Sports (EMS), which opened new retail stores across the U.S. and set up on the Web, but stopped printing a catalog. Instead, they offer separate brochures for each class of products and for techniques such as first aid. Given the rising costs of printing and mailing, and the frenzied lurch of computer commerce, the mail-order catalog might soon follow the way of the fiercely partisan, hole-in-the-wall backpacking shop.

Catalogs are the most fleeting form of

Again, a comprehensive list is neither possible, nor, given the volume of the flood, likely to do much except sweep you off your feet. So let’s hop from one boulder to the next. One of the most provocative books is Beyond Backpacking, a guide to lightweight hiking by the protean Ray Jardine: engineer, climber, and through-hiker. Besides a wealth of practical lore and serious rethinking, it has plans for making ultralight gear. Karen Berger has written useful how-to books, most recently Advanced Backpacking, and Bruce Hampton’s and David Coles’s updated Soft Paths: How to Enjoy the Wilderness Without Harming It is a practical guide to new techniques. Other instant classics include How to Shit in the Woods by Kathleen Meyer and How to Have Sex in the Woods by Luann Colombo. Backpacker magazine and The Mountaineers Books launched a series that so far includes books on backcountry cooking, first aid and medical treatment, making camp, Leave No Trace techniques, and tips from experts (for a list of books, see Appendix IV).

Fortunately, dear old Backpacker survived engulfment by Ziff-Davis and is now under the sign of Rodale Press, which publishes Organic Gardening and Men’s Health. But the days of strict advertising guidelines and a policy of not giving detailed directions are so long gone that they aren’t even a memory. So in a recent issue, along with ads for packs, boots, and other staples, is a speeding Cadillac Catera (whatever the hell that is), with a command to “Think about more horsepower than a BMW 328i.” I’d rather not. The content is more encouraging, with a contentious lead article on trailguides, a piece on camping with Mom, and a too-brief guide to repairing old gear, with a list of cobblers and tinkers, in itself worth the cover price. The ads in the Marketplace section in the back are a prime source for gear.

Backpacker gear reviews are consistently one of the best parts of the magazine. My own results agree with theirs about 75 percent of the time, with differences owing to stature, pain threshold, and boneheadedness. Editor’s Choice Awards (not only for Backpacker but for other magazines) seem less reliable, since they tend to be given in advance for striking new concepts, some of which don’t bear out. For instance, an award-winning boot felt great in the house, but after a week in the Big & Scratchy the revolutionary coating peeled off and one of the lace lugs tore out. Plus, it flexed in a way that chewed skin off the tops of my toes. (The maker claims that these troubles have been fixed, but after three strikes I remain wary.) In any event, Backpacker also publishes an annual Gear Guide in March, including the tables of weights, measures, and such gone missing from catalogs, along with useful introductions, brief comments, and the dates of review. They also maintain an extensive Web site with listings of gear, a women’s page (including potential hiking partners), and other things not in the paper version. Above all, Backpacker is the only national magazine devoted entirely to backpacking.

Another survivor is Outside. While it has grown glossier and zoomier, with more attention to extreme and frenzied pursuits than to backpacking, there is still a core of excellent writing (Mark Jenkins, for instance) and concern for the outdoors. In the 1980s, Outside carried tests, a function now corralled in the annual Spring Buyer’s Guide. This has comparative tables, but is more notable for flashy photos and breezy reviews that verge on sales-chat. It also includes kayaks, canoes, mountain bikes, cameras, watches, and sunglasses from other planets.

A genuinely new entrant (from the publishers of Outside) is Women Outside, which debuted in 1998. But despite ads for packs, boots, etc. (and the infamous Catera) the content is even less foot-to-earth than that of Outside. (Though I did enjoy the piece on cheerleaders.) A rough-and-tumble newsprint equivalent is Wilds Woman (subtitled “Women Getting Wild Outside”) that also rounds up reviews of gear, rock groups, and “grrlz on film.” Stray pieces on hiking and backpacking show up in Men’s Journal (which also publishes an annual gear guide), and in Women’s Health and Fitness, Men’s Health, and Walking (a women’s magazine on fitness and grooming rather than the outdoors).

A solid annual treatment of gear is published by Climbing, with coverage of tents, boots, crampons, packs, and stoves. While the range is limited (27 stoves versus 43 in the Backpacker guide) the accompanying text is full of hard-won details, for instance a sidebar on modifying a stove to hang. If you don’t mind photos of people in tights with agonized looks on their faces, it’s a valuable supplement.

From its former hook-and-bullet status, Sports Afield now courts backpackers with a focus on hiking and camping sans kill, and environmental coverage. The ads are a curious mix of packs, tents, parkas, sport utility vehicles, guided hunts, rifle scopes, and chewing tobacco.

Besides the perennials, any well-stocked newsstand will yield more specialized and considerably stranger magazines, focused not so much on backpacking as on the sort of person who might occasionally backpack. Mountainfreak, from Telluride, Colorado, is goofy and eclectic, with rock climbing, Forest Service misdeeds, the impact of trekking on Nepal, per-maculture, alpine herbs, fly-fishing, Tibet, tattoos, music, and yoga (or what a friend calls “Pasta-farian culture”). Orion looks at our relationship to nature in a penetrating way, with fine writing and beautiful design. In that line, Colin likes Resurgence, a magazine published in England that hails itself as “an international forum for ecological and spiritual thinking.” The refreshingly plainspoken Wilderness Way covers do-it-yourself gear, foraging, and primitive skills.

Regional tabloids, subtitled “sports guide” or the like, abound with articles on destinations, personalities, controversies, resource politics, and ephemera-in-general. Since most are ad-supported, they take few risks with gear reviews.

Adventure travel (or eco-tourism, a term with the same effect on my hackles as “wilderness management”) is served by such as Adventure Journal and Global Adventure (from the U.K.). Along with gear reviews, these run ads from guide services and resorts.

A monthly newsletter, Expedition News, has sprung up to gauge the flow of sponsorship dollars and track the success or embarrassment of various industry-supported adventures. The publisher claims that such subsidized expeditions “are a way for people to learn about the world,” which is in a certain way true.

Further publications (e.g., books on first aid or backpacking with children) are covered in the sections dealing with each subject or listed in Appendix IV.

The current state of the Ms.

During 16 years with a backpacking woman, Linda (Baker, then Rawlins, and now Baker once more), I’ve noticed significant changes. Between bouts with formal education, she worked outdoors as a surveyor, a forest researcher, a mapper of lost trails, and then as leader of a trail crew. Early on, she talked about the lack of essential gear—not cute sleeveless tops, but boots, packs, and long underwear—to fit her form. She discovered the Lowe Contour pack, a bisexual design that soon led to the womanly Sirocco. Accurately proportioned women’s parkas, wind pants, and the like appeared from Patagonia and others. But boots lagged, as makers thriftily relabeled men’s styles with equivalent women’s sizes.

However, as the 1990s progressed, those who took the measure of contemporary women and redesigned their products accordingly have been rewarded. With a great many women not only active in backpacking but seeking outdoor careers, the bush telegraph quickly spreads the word on what fits.

Now, Lowe Alpine reports that 59 percent of its clothing is labeled for men (or unisex) and 41 percent for women, a shift from the prevailing ⅔ to ⅓ mix. Some rising stars like Mountain Hardwear emphasize that their clothes and sleeping bags are “designed by women for women.” But men still run the show: a random sampling of sales and design personnel (based on the business cards I kept) yields 63 percent male to 37 percent female (with Gardner, Hadley, Drew, Paige, and Sam being, as I recall, women). There’s no doubt that CEO-types are still predominantly male, and production stitchers mostly female.

But there are other concerns. One of these could be called a rise in trail fear. Violent crimes on popular trails, vandalism at trailheads, and thefts from unattended camps have made trail crime a subset of street crime, as one reader writes “in a manner most blasphemous.” This breaks my heart. I do see more women on the trails, but few of them are hiking solo. A bronze-goddess friend even carries a .44 magnum pistol “for bears.” (Though for both inter- and intraspecies self-defense, pepper spray might work better.) One male reader who came to a shelter on the Appalachian Trail in a storm found a party of women reluctant to let him in, and wrote “I do not yet know how to cope with the look.”

Still, despite media-borne waves of apprehension, the backcountry is safe. Compared to interstate highways, shopping malls, parking lots, kitchens, and bathrooms, the genuine hazards are few. But the sense of being alone and far from help—fear itself—can be hard to shake. Simply, one of the best ways to shake it is spend more time outdoors. Working for the Forest Service, Linda mapped so many trails by herself that she thinks nothing of tossing her gear in a pack and heading out alone for a few days of fishing in the high country. And I’ve met many other women who take challenging solo trips. The deeper the well of outdoor experience, it seems, the less fear.

One spring I hired a woman named Robyn Armstrong as field assistant and we spent the summer camped in remote places. The first thing we established was that she was safe with (and from) me. We had rough going at some points, but the result was a lasting friendship. So, despite the great divide between the sexes, if men err on the side of kindness and women in the direction of trust, our prospects out-of-doors are bright.

Colin got much of his early outdoor experience in the British marines and I had mine with the U.S. Forest Service. So our shared preference for solitude might owe in part to that. But some of our closest cousins—chimps, gorillas, and baboons—do nearly everything in company, and aboriginal people travel in bands. Thus, the group-bonding approach of Outward Bound and the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) is a natural one. And, in a culture where vital outdoor skills have been lost, it’s a necessity.

Still, my first sight of outdoor-school students was a neat line of 20 orange dots (their packs) up a snow-and-talus gully. I recall thinking that a loose rock or a slip up top could wipe out all below. And over the years I’ve seen organized groups do magically dumb things in that same imitative way. On organized trips the greatest hazard seems to be not Unforgiving Nature but an unskilled or careless instructor. Still, for those who haven’t the patience for trial and error, schools are a reasonable shortcut.

“If nothing else, school has prepared me for a lifetime of backpacking.”

There are also a great many boot camps and survival schools for “at-risk” youth, collectively nicknamed “hoods in the woods.” The worst of them have killed their charges in the name of reform and profit. But there are other quite different nonprofit groups, such as Wilderness Inquiry and Big City Mountaineers, that offer disabled people and disadvantaged youth a chance at the green world, and these deserve more popular support (see Appendix V).

But it’s time to get our eyes back on the trail.

When planning a house on your back, the weightiest matter is

Weight.

COLIN: The rules used to read:

Basically, these rules still stand. But a tide race has set in toward ultralightweight gear, and emphases have shifted:

1. Strive to reduce to a minimum the number of items you carry (often by sensible multiple usage).

2. Gossamerize every item toward vanishing point.

Result: loads that by old standards are featherweight.

CHIP: Of course there are strong crosscurrents. Countering the tug toward Unbearable Lightness is a tendency to seek Total Comfort. Devotees of the former vie for increasingly longer trips with spookily light loads, while the latter bake focaccia in trail ovens and take calls on their cellular phones.

Earl Shaffer, in 1948 the first to hike the entire Appalachian Trail, still hews to low-tech essentials. When he repeated his feat 50 years later and finished just before his 80th birthday, he carried a military-surplus rucksack with the sidepockets and hipbelt removed. Inside were a down sleeping bag; a down vest; a plastic poncho (which also served as groundcloth and tarp); extra pants, shirt, undershorts, and socks in plastic bags; a recycled plastic jug for water; and widemouth plastic jars for oatmeal, crackers, and peanut butter. He was crowned with a pith helmet and headnet (with stocking cap for chill nights) and wore a long-sleeved plaid shirt and cotton workpants. On his feet were Red Wing 8-inch leather workboots with the heels pared down.

But Shaffer seems like a raving gearhead compared to Emma “Grandma” Gatewood (1888–1975). In Beyond Backpacking, Ray Jardine describes her as hiking in plain, black sneakers and wearing a plastic rain cape and an old shower curtain for weather protection, with her food and spare clothing in a cloth sack slung over her shoulder. In 18 years of hiking she traversed the Appalachian Trail twice, walked most of the long trails in the eastern U.S., and then hiked the 2000-mile Oregon Trail in less time than the original wagon trains took for the trip. “Most people are pantywaists,” said Grandma G. “Exercise is good for you.”

Foraging and scavenging can also lighten your load. In a Backpacker article, Andy Dappen tells of a trip he and brother Alan took on a 47-mile coastal trail in British Columbia. The coast being rich in both sea wrack and hiker discards, they scrounged cans to make cookpots and a stove, found a fry pan on a sea-stack, slept on foam padding from a deck-chair cushion, caught cod, netted crabs, and picked berries. They also scavenged T-shirts, shorts, socks, gloves, bandannas, rope, bottles, utensils, and plastic sheeting. Given a food- and trash-rich environment, this sort of trek can broaden your thinking and enrich your repertoire of skills. The big sacrifice, Dappen admits, is comfort. For three nights before finding the cushion they slept poorly. The other sacrifice is time. In spare environments, the desert or alpine tundra, one can spend much of the day foraging and still go hungry.

All of which our hunting-and-gathering ancestors proved for uncountable millennia, though there is value in proving such things for oneself, even in an elective way.

Technological tides have made lightness more bearable: warm 1.8-lb. sleeping bags, 10-oz. water-shedding breathable parkas, and 3-oz. stoves make it possible to float without suffering. While on the other hand, internal-frame packs with padding like that of Mercedes bucket seats have made it equally possible, in the short term at least, to hump foolish loads in return for luxury. Of course, in the long term gravity always wins.

A purist approach is self-reinforcing. For instance, the Ray Jardine—style pack is 2600 cu. in (with an 1100-cu. in. extension collar), lacks padding, frame, or hipbelt, and weighs about 14 oz. So it is beautifully adapted to very light loads, and performs less well as the weight increases. (But, says Ray, so do you.) For the ultralight through-hiker, intent on covering as many miles as possible with the least effort, it’s revolutionary. Yet in my case, with occasional payloads of such unwieldy things as a 100-foot tape, bank stakes, and a current meter, it just won’t do.

In the same way that you might launch yourself on the curve of Unbearable Lightness, you might also opt for a cushy 0° sleeping bag (no chance of the slightest chill), not three layers of clothing but six (likewise), and, gee, why not bring the espresso pot (and matching cups). Not sure which fly rod to take? How about both? Of course to contain these ample furnishings you’ll need one of those Mercedes-upholstered packs, at 7 or 8 lbs. And given the accumulated poundage, your feet will cry for stout, supportive boots with springy insoles. So it goes. One of my self-indulgingest friends is fond of quoting Blake: The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.

Having enjoyed it both ways, I tend to choose the Light. Though not for abstract reasons. For seven years I did field hydrology in a wilderness, which meant that my pack might hold a 40-lb. payload of float tube, drysuit, fins, meters, cables, bottled lake samples, and other things that I could neither eat nor wear. Since a normal heft of food and camping gear would top me out at an unbearable 80 lbs., I sought out the lightest equipment and shaved ounces madly.

The Forest Service wouldn’t buy light gear, so I did. And when I took my light gear on fun trips, I thought my feet had grown wings. But I didn’t achieve Unbearable Lightness without tears, and frozen ones at that. A late-season solo into the Wind River Range of Wyoming dealt me a science-load of about 35 lbs. Since it was 10 miles in with a forecast of snow flurries and moderate (30°F) temperatures, and I knew of a sheltered camping spot just above 10,000 feet, I minimalized with a 1.8-lb. synthetic sleeping bag, a 1.2-lb. bivouac bag, and a dinner of curry ramen. I hiked in through intermittent snowfall, got my samples jugged, and set up the snow collector. Then I cooked my Spartan meal and kipped into my bivy sack, as spindrift hissed from the overhangs. But then it quit snowing. The sky cleared and the temperature plummeted to a thrilling 3°F.

At that point (2:00 a.m.) the curry ramen kicked in. I woke up cold, with a volcano in my guts. I erupted from the bivy sack, dug a quick pit, and hunched under a diamond-hard sky while my entire body turned inside out. Returning to the bivy, I shivered for a half hour and then repeated the process. Emptied out, I donned my entire inventory of clothing and dove back into my bag, but by then I was deeply, tooth-chatteringly chilled. So I rose again and built a small fire, with a flat reflector stone behind and converging rockfaces at my back. It took an hour to get warm (and sleepy). Then I crept into the bivy sack and blinked out until the sun woke me.

The lesson (beyond forevermore avoiding that brand of curry ramen) is this: never, never, ever place your entire trust in gear. If you aspire to lightness, whether high-tech or low-, you need an array of primitive backup skills. The point is not to live in a rabbity state of fear, but to stay somewhat flexible in your approach.

Given a preference for lightness, I don’t always practice it. A recent late-October trip took me into a trailless part of the Wind Rivers, where I expected to see no one for five days. It had snowed and melted off, except in the shade, to about 10,000 feet. Besides testing gear, I was studying a stream and needed to wade. I wasn’t sure whether I could follow the stream out or would have to climb back out of the gorge and retrace my route. The clouds promised a storm. So I took a 4-season tent, plenty of backup clothing, and extra food. Being large and bony, I also took a self-inflating foam pad. Because I expected foraging bears trying to put on a last coat of fat before denning, I also took a Garcia Cache (2.5 lbs.). And I indulged my spirit with a good, thick (1-lb.) book. Thus, my pack weighed 41 lbs. 7.5 oz., and From the Skin Out (FSO) my load was 46 lbs. 13.4 oz. The storm hit the first night, with strong winds and 4 inches of wet snow. It snowed on and off during the trip, and in the bottom of the gorge the leafy undergrowth held sodden clots of white. The wading was slick and the water icy. I misjudged one crossing and had to swim with the pack, which made me glad for the waterproof stuff sacks and extra clothes. My route was choked with brush and deadfall and at last narrowed to a pulse-pounding drop-off, so I had to reverse course, climb out, and camp on an exposed ridge with clouds roaring past. No hungry bear visited. But in other respects, I not only used what I brought, but was glad of it.

Not long before, in mid-September, I’d been seized by Unbearable Lightness. Despite freezing nights, I decided to see whether I could pull off a working trip, collecting stream data, with a fanny pack. In (and on) it, I managed to load a good ultralight sleeping bag, a titanium pot and spoon, an insulated mug shorn (Fletcher-fashion) of the handle, and a pellet stove. Underwear, socks, a knit cap, an anorak, and shell pants were tucked in the corners. Having to wade, I packed sandals and neoprene socks. On top went a pad and a bivouac bag in a single tight roll. One mesh sidepocket held a 1-quart water jug while the other held a canister (single-malt Scotch) with two days’ food, both sprayed blaze orange so a hunter wouldn’t blaze away at my trophy hindparts.

Ultralight fans tend to use the term packweight, which doesn’t include water or food. So my packweight was 14 lbs. 14.1 oz. With the food and a full quart of water, I was actually carrying 18 lbs. 8.2 oz. What with clothing and boots, my FSO weight was 21 lbs. 1.6 oz. (the Mountainsmith fanny pack had auxiliary shoulder straps, which I used). The route, much of it off-trail, undulated for 15 miles between 9000 and 10,500 feet. Having a light load and low center of gravity eased the bushwhacking, so I sloped off into the tangles and saw some country I hadn’t visited before. During the night it snowed lightly, but I slept warm and dry. The only lack was food—with 1.1 lbs. for two very long days I stayed hungrier than usual. For an overnight jaunt that’s not a problem, but for longer trips and through-hikes it most certainly is. For load lists and weights for these and other trips, see Appendix II.

COLIN: Yes, Unbearable Lightness offers huge advantages, but it’s easy to gloss over uncomfortable facts. Although the lighter load helps—helps a ton—that’s not the whole truth, so help me God. Backpacking isn’t all traveling. It’s also sleeping and loitering and eating, for example. So backpacking pleasure is also comfortable sleep, cozy warmth at all times, and perhaps a few heavy luxuries—short of the complete works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (this page)—not to mention a full belly. I note that many light-gear enthusiasts seem to skimp on the food. Yet there’s general, though not total, agreement that to stay healthy and fully active the average person needs a daily ration of around 2 lbs. of dehydrated food, and some stories of ultra-Spartan rations frankly sound harder to swallow than the food.

CHIP: Of course, one of the benefits of lightening up your gear is that it allows you to carry good food: I regularly pack fresh fruits, vegetables, even potatoes, which were a major dietary item on Mark Jenkins’s epic bike ride across the Soviet Union, which he describes in his book Off the Map. Even with dire loads on winter expeditions, and a largely freeze-dried regimen, I usually take fresh garlic, an onion, carrots, bell pepper, and similar whole foods to gnaw raw or add to the pot. I’ve long dried my garden produce, including such delights as plum tomatoes and scallions, for backpacking use. And the olive oil and vinegar I carry for mixing hummus dresses wild-green salads. In the course of hundreds of trips, I’ve noticed that an unrelieved diet of freeze-dried meals, energy bars, and the like results in a sense of deprivation. In my cowboying years, I saw that horses fed on bagged pellets and grain still had an ardent need to graze. Lacking grass, they would chew the tops off pine fence posts.

That is, beyond a mere slate of proteins, fats, and carbohydrates, we poor beasties need something to chew that resembles food. So—be pound-wise, but don’t skimp.

Both approaches, the Road of Excess and the Gossamer Gallop, have been around for some time. Most backpackers choose neither exclusively but instead adopt some of the best elements from both. For instance, at the Total Preparedness end is a Coleman Pro-Lock pocket tool, with which I could probably rebuild a radial aircraft engine, that weighs 8.4 oz. My Victorinox Tinker (i.e., Swiss Army knife), with a 2½-inch blade and scissors but no pliers, is fine for most repairs at 3.2 oz. But I just got a Coast Micro-plier pocket tool with both pliers and scissors (small but usable), and a knife blade just long enough to clean a fish, at a snappy 1.8 oz. That gives me 6.6 oz. to play with: the weight of a medium-size potato. Or two paperback mysteries. Or, God help us, a mini espresso maker.

Having suffered exquisitely under expeditionary loads of 85 lbs. or more while traversing icy logs, swollen streams, and breakable snowcrust, I think that any residual toughness so gained was simply not worth the wear and tear. Really, the only good part is having lived to tell the story. Preferably from a good, deep chair, with stiff drink in hand.

The maximum for backpacking as an enjoyment is perhaps one-third of body weight. A well-conditioned body can handle more weight, if necessary, and training routines can help (this page). A reasonable load would be one-fourth or one-fifth of body weight. Unbearable Lightness would kick in down around one-eighth.

Age is another ponderable. A good way to make children (or dogs, for that matter) hate backpacking is to load them too heavily. Young people are also somewhat awkward; that is, they have more resilience but less in the way of grace. As aging makes us less resilient, it can also make us—given any luck at all—far more efficient and graceful. As they say in the Hindu Kush: An old goat has the surest step.

For old goats as well as aspiring ones, the process of refining your game is part of the fun. Along with choosing one item of gear or another, you can follow the Fletcherist practice of lopping your toothbrush and tearing the labels off tea bags: set aside all your trimmings and then triumphantly weigh them all together. If you’re serious, you’ll soon acquire a good set of scales. I use a Hansen Commercial 860 for loads up to 60 lbs. and a Chatillons Improved Spring Balance for weights below 18 oz., with a Pesola Spring Balance for nitpickery under 100 grams (all available from Forestry Suppliers; see Appendix III). A further note on weight: while I’m bound by convention to pounds and ounces, given any good sense whatsoever you’ll do your reckoning in grams and kilos.*3

Again, the paring process is a profound sort of fun. At each pass of the blade, you can choose whether to drop your total weight or keep it neutral by adding some prized indulgence. The range of gear now available offers so many opportunities that it’s hard, unless you throw caution (and your savings) to the wind, to exhaust them all. For instance, clothes and sleeping bags should be in waterproof sacks. But cookpots are quite happy in mesh bags at half the weight. Should you wear mountain boots, at 3 lbs. 6 oz.? Or trail-running shoes, at half the weight? To go up on the glaciers, you’ll need boots. But what about aluminum crampons, at half the weight of steel ones? There are also radical shifts, such as choosing a solar-powered campsite for long trips (for an explanation, see this page). If you’re replacing worn gear, you can refine your outfit, piece by piece. But don’t be in too much of a hurry: let things wear out. Then see if you can get by without them. A good way to know the worth of a thing is to do without it for a while. If you find you can, then not only do you shed weight, but it costs nothing at all.

Cost

It’s not just a fantasy but a verifiable fact that the cost of good backpacking gear has risen much less steeply than the price of—a car, for instance. In 1980 the MSR model G stove, not including fuel bottle, cost $60.75. You could get a reasonably equipped Saab sedan of that era for about $7500. The current XGK Expedition stove will nip you for $90, not bad as inflation goes, while the postmillennial Saab rolls out at $30,000-plus. And in the backpacking realm, some prices have remained nearly the same. The 1980 Bleuet (the company is now known as Campingaz) Globetrotter cartridge stove cost $21; the present Twister 270 fires up for $22, with a built-in piezoelectric lighter. Has the quality gone to hell? In a word, no. It’s a great little stove.

But in 20 years, vast frontiers of expenditure have opened: computers and video systems to name just two. (Not to mention cosmetic surgery.) So while today’s average backpacker probably spends less as a percentage of income, we tend to whine a great deal more. The pricing system that’s evolved in response falls into three categories. The best off-the-shelf gear is called high-end. An example is the MSR Dragonfly stove, which roars, simmers, and burns everything but walrus blubber, at a cool $100. Then there is the solid, though not necessarily stolid, midrange. The Coleman Peak 1 Apex II is a good multi-fuel stove at roughly the same weight for $65. Still lower there lurks what is called price-point gear. While the term implies that low price is the only factor, there are surprises waiting for those unblinded by snob appeal. Such as the cute little Markill Devil stove, which claims a quicker boiling time than either of the above, at half the weight, for $20. If you don’t need to melt cubic yards of snow, the Devil might suit you fine.

There is also the realm of the specialized and hair-raisingly expensive, like the Primus Titanium stove—a 3-oz. blowtorch for $200—that is generally called trick. Beyond trick is custom, the sweet stratosphere of McHale Packs and Limmer boots. True custom gear might set you back now, but also might last a lifetime.

In specialty shops, the high-end is high indeed but is generally worth the bite in terms of durability. The midrange is likewise good. While the price-point is usually decent. But if you venture into a “big-box” chain store, you might find that its high-end barely touches the specialty midriff. The midrange falls at knee-level. And the low end can be subterranean indeed. Having worked with outdoor programs that plumbed the depths of cheap gear, I tend to avoid it. It’s harder to use, breaks down fast, and is often not worth fixing. Some conglomerates field one line for specialty shops and another for discounters, so brand name isn’t necessarily the key. If you want to spend less, then bone up on the basic materials (e.g., Polarguard fiber for sleeping bags) and take the time to count stitches and slide zippers. If something looks useful, pounce. For many years, my 3-season bag was a screeching yellow beast I plucked off the trash pile at a firefighting camp. The zipper was blown, so I duct-taped the foot closed and used it that way for years. Then Linda (bless her) replaced the bad zipper. That scrounged bag (originally costing 20-some dollars) was home base for almost a decade. The moral? If the pudding tastes good, don’t worry about the price.

Still, if you’re working out your trajectory, or thinking about a one-shot winter camping trip, the answer might be

Renting.

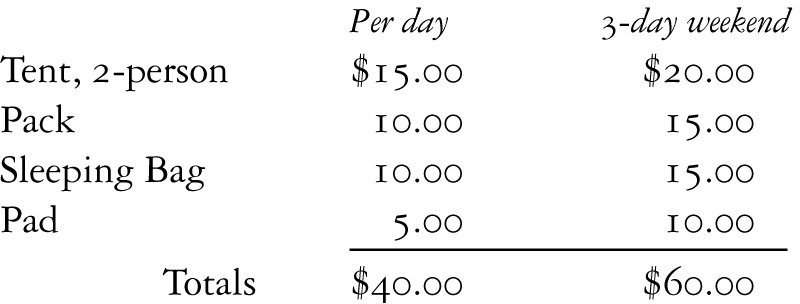

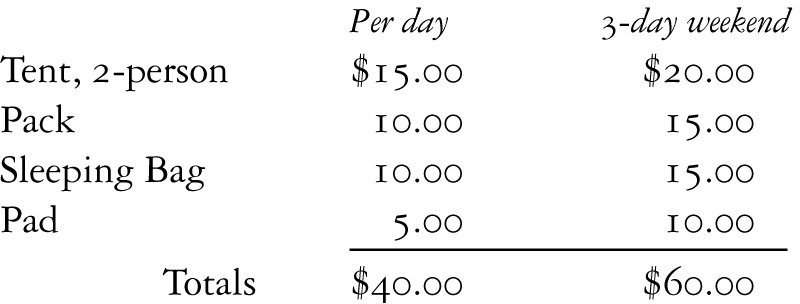

Trailhead Sports, in Logan, Utah, where I worked for some years, had an active rental program. I learned a lot by fitting, maintaining, and fixing rental gear. Quite often, we sold it at the end of the season at a steep discount. Some shops give a credit based on rental fees if you buy as a result. Some chains, Eastern Mountain Sports (EMS) being perhaps the best example, maintain strong rental programs. As of this publication, the rates average:

Of course, at 60 bucks a pop, renting is not a way to go for very long. And there are risks attached. Deposits are usually the daily rate times 10. If you return gear dirty or trashed, despite the fact that it wasn’t really your fault, etc., etc., most shops will whack you for cleaning, repair, or replacement. So rent if you must, but keep your eyes pegged—for the same outlay you can score heavily at a garage sale or gear swap. There are also “recycled” outdoor shops where moderately good deals can be haggled. Another good bet is to find a thrift shop in a capitalist haunt like Jackson Hole. At season’s end (when the colors of both leaves and fashions change), you can reap such shocking bargains as to feel positively guilty.

Of course, in an age of oversupply and hyperdemand, it’s also possible to get burdened with bargains. So it always makes sense to think in terms of

EQUIPMENT FOR A SPECIFIC TRIP.

COLIN: Most decisions about what to take and what to leave behind will depend on the answers you get in the early stages of planning when you ask yourself “Where?” and “When?” and

“For how long?”

We have already looked (on this page) at the kinds of differences that can arise in equipment choice for a weekend as opposed to a week. Beyond a week the problems change. Food is the trouble. For 10 days, most people need around 20 pounds of it; for two weeks, almost 30. And such weights reach toward the prohibitive. I don’t think I’ve ever traveled—as opposed to operating from a base camp—for more than 10 days without food replenishment. (For replenishment methods—by outposts of civilization, caches, airdrops, etc.—see this page.)

As far as equipment is concerned, then, even a very long journey boils down in essentials to a string of one- or possibly two-week trips. Besides replenishable items, all you have to decide is whether you’ll be aching too badly before the end for a few extra comforts. A toothbrush, a paperback book, and even camp footwear may be luxuries on a weekend outing, but I imagine most people would think twice about going out for two weeks without them.

What makes a very real difference is that the longer the trip, the greater the uncertainties about both terrain and weather; but here we begin to ease over into

“Where and When?”

The two questions are essentially inseparable (see, again, this page and this page; and for planning from maps). Terrain, considered apart from its weather, makes surprisingly little difference to what you need carry. The prospect of sleeping on rock or of crossing a big river may prompt you to take a self-inflating mattress, as opposed to a closed-cell foam pad for snow, or nothing at all for sand (this page). In cliff country you may elect to take along a climbing rope, even when on your own (this page). Glaciers or hard snow may suggest ice axe and crampons (this page). But that’s about all. And snow and ice, in any case, come close to being “weather.”

In the end it is weather that governs most of the decisions about clothing and shelter. Now, weather is not simply a matter of asking, “Where?” and answering, “Desert,” “Rainforest,” or “Alpine meadows.” You must immediately ask, “When?” And from the answer you must be able to draw accurate conclusions.

In almost any kind of country the gulf between June and January is so obvious that your planning allows for it automatically. But the difference between, say, September and October is not always so clear—and it may matter a lot. (One of my advisers calls it “transition weather.”)

A convenient source of accurate information is the U.S. National Climatic Center; above all the series of booklets Climatography of the United States. Each booklet (one per state) has a general climate summary and a map showing weather station locations. For each station it tabulates monthly averages of temperature and precipitation: means and extremes, highs and lows. Also, mean number of days with temperatures above 90°F and below 35°, 12°, and 0°. And snow and sleet data, including greatest depths. For some stations there are data on relative humidity, wind speed, barometric pressure, and hours of sunshine and heavy fog. The tables tend to be printed rather fuzzily, but they’re peer-hard legible. Booklets run $2 each (plus a service and handling charge of $5, or $11 for orders over $50) from the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC), 151 Patton Ave., Room 120, Asheville, NC 28801-5001, 828-271-4800, fax 828-271-4876.

CHIP: Libraries might have a compilation (in huge format) called Climatic Atlas of the United States. Found in the Government Documents section, it reports daily maximum, minimum, average, and extreme temperatures, along with temperature ranges. It also includes frost-free dates, solar-heating indices, rainfall, snowfall, percentage of sunshine, and wind speed and direction. Some of this information is displayed on tables, and some on maps of the U.S. But look at the dates—the weather is changing significantly in some parts, and older data may be misleading.

COLIN: The NCDC also generates a blizzard of other information, including a climatic map of the U.S. and data on freeze/frost incidence, hourly precipitation, and storms. There’s some worldwide information, too. A single-sheet list (free) summarizes what’s available. A 132-page booklet, Products and Services Guide (also free) gives greater detail, including the many Web systems available through its home page, www.ncdc.noaa.gov—including such goodies as Climatic Extremes and Weather Events, Temperature Extremes, El Niño/La Niña, Global Measured Extremes of Temperature and Precipitation, Summary of the Day (8000 U.S. sites), U.S. Monthly Precipitation, and Global Climate Model (100-year run).

Many larger national parks, such as Yellowstone, Yosemite, and Death Valley, have weather data available on their Web sites, and those of other parks have links to weather information. Almost all national parks can provide some weather information through their listed phone numbers.

In Canada the prime equivalent to the U.S. Climatography Series is 1961–90 Canadian Climate Normals, available on paper or diskette. The books cover six regions and give average and extreme monthly values of temperature and precipitation for all stations in Canada with 20 or more years of information, and monthly average wind, sunshine, and moisture for stations that record them (prices in Canadian dollars: British Columbia, $30.95; North, $19.95; Prairies, $37.95; Ontario, $26.95; Quebec, $32.95; Atlantic, $22.95; full set, $200. Diskettes for each region are $40; for all of Canada, $200). All of the information in the books/diskettes plus monthly data for the period of need from more than 6900 sites across Canada is compiled on a CD-ROM disk: Canadian Monthly Climate Data and 1961–1990 Normals, with enabling software for MS-DOS or compatible systems, $200. A list of the available information for Canada may be found at www.msc-smc.ec.gc.ca/climate/index [website is no longer active].

The Canadian Climate Normals Atlas covers 1961 to 1990 and gives mean daily temperatures, mean daily maximum and minimum temperatures, total rainfall, total snowfall, and total precipitation. The set of two diskettes—temperature and precipitation—come in two versions: PXC graphics files that can be used with several off-the-shelf software packages, and CUT and MAP formats intended for Geographic Information Systems (GIS) such as SPANS. (Both versions are $50 Canadian.)

To order any of the above, or for more Canadian information, contact the Climate and Water Products Division, Environment Canada, 4905 Dufferin Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M3H 5T4 or e-mail Climate.Services@ec.gc.ca. (Make checks payable to the Receiver General for Canada.)

Monthly figures can never tell the whole story, but these booklets (certainly the U.S. ones, which I’ve used for years) can be a great help in planning a trip. In deciding what night shelter you need, it may be critical to know that the lowland valley you intend to wander through averages only 0.10 inch of rain in September (20-year high: 0.95 inch) but 1.40 inches in October (high: 6.04 inches). And decisions about what sleeping bag and clothing to take on a mountain trip will come more easily once you know that a weather station 8390 feet above sea level on the eastern escarpment of the 14,000-foot range you want to explore has over the past 30 years averaged a mean daily minimum of 39°F in September (record low, 19°F) but 31° in October (low, 9°); by applying the rough but fairly serviceable rule that “temperature falls 3° for every 1000-foot elevation increase,” you can make an educated guess at how cold the nights will be up near the peaks. Remember, though, that weather is much more than just temperature. See especially the windchill chart.

A wise precaution before any trip that will last a weekend or longer is to check on the five-day forecast for the area. Such forecasts are given every few minutes on National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) VHF radio stations that now form a network covering most of the country. You can buy small sets that receive them, starting at a few ounces and $29. Or, for taped, local reports check the telephone book under “U.S. Government, Department of Commerce, National Weather Service.”

CHIP: For the computerized, a wide array of weather reports and data banks can be found on the Internet by activating a search for “weather.” Some interesting Web sites I found (all prefixed by http://www) were Weather Satellite Views, which displays satellite images and forecasts for North America at aerohost.com/weather-satellite.htm; the Interactive Weather Information Network, with continuous updates from the National Weather Service, at iwin.nws.noaa.gov/iwin/main.html; and The NOAA Weather Page, which lists sources of weather information at esdim.noaa.gov/weather_page.html [website is no longer active]. Many server home pages have links for weather reports. To hone your personal forecasting skills, a good, portable book with over 300 photographs is The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Weather ($19). Also good (though not packable) are a Global Climate Chart and an Atmosphere Chart (both $20) available from Forestry Suppliers (see Appendix V).

COLIN: But the finest insurance of all is to have the right friends. I have one who is not only a geographer with a passion for weather lore but also a walking computer programmed with weather statistics for all the western United States and half the rest of the world. I try to phone him before I go on even short trips to unfamiliar country. “The Palisades in early September?” he says. “Even close to the peaks you shouldn’t get night temperatures much below twenty. And you could hardly choose a time of year with less danger of a storm. The first heavy ones don’t usually hit until early November, though in 1959 they had a bad one in mid-September. Keep an eye on the wind, that’s all. If you get a strong or moderate wind from the south, be on the lookout for trouble.” By the time he has finished, I’m all primed and ready to go.

For keeping an eye on the weather during trips, see this page.

Unless you have the only infallible memory on record, you ought to have a couple of copies of a

It should be a full list, covering all kinds of trips, in all kinds of terrain, at all times of year. On any particular occasion you just ignore what you don’t want to take along.

Eventually everyone will probably evolve his own list. But many local and national hiking organizations (see Appendix V) are happy to supply beginners with suggestions. So are some commercial firms. Appendix I is a full list that might be a useful starter. You can photocopy it and check from the loose pages, conveniently buttressed by a clipboard. But as soon as experience permits, draft your own list.

FURTHER PLANNING

Unless you are fit—fit for backpacking, that is—you should, at least as early as you start worrying about equipment for a trip, worry like hell about

The only real way to get used to heavy loads is to pack heavy loads—though what you mean by “heavy” will depend on your experience, ambition, frame, muscles, and temperament. I certainly try to fit in one or two practice hikes in the week or two before any long wilderness trip. Sometimes I even succeed. Whenever possible, I make this conditioning process seem less hideously Spartan by stowing lunch in the pack and eating it on a suitable peak, or by adding work papers and setting up temporary office under a tree. Or I may carry the pack on one of the walks I regularly take in order to think, feel, sweat, or whatever. As far as the exercise goes, I find that it makes no difference—well, not too much difference—whether I walk in daylight or darkness.

Even if your regimen doesn’t permit such solutions, make every effort to carry the pack as often as you can in the week or two before you head for wilderness, if only to prepare your hips for their unaccustomed task. Details of distance and speed are your affair, but take it easy at first and increase the dose until at the end you’re pushing sweaty hard. If possible, walk at least part of the time on rough surfaces and up hills. Up steep hills. Not everyone, of course, has the right kind of terrain handy, but at a pinch, anywhere will do. The less self-conscious you are, the freer, that’s all. You may blench at the thought of pounding up Main Street with a 40-pound pack (all those damned traffic lights would wreck your rhythm anyway), but, pray, what are city parks for? And many big metropolitan areas now have nearby hiking trails.

If the pressures of time, location, family, and amour propre combine to rule out fully laden practice hikes, attack the problem piecemeal. Your prime targets are: feet, legs, lungs, and shoulders.*4

Legs are best conditioned by walking, jogging, or running. Especially running. And especially up hills. For those with limited time at their disposal, running is currently the most popular and perhaps the most efficient answer. I suspect that a not inconsiderable number of those pent-up citizens who pant around Central Park Reservoir at their various rates and gaits may be preparing for a week or weekend along the Appalachian Trail. I know at least one who often is. Nowadays there are “par courses” in some cities: you run from one exercise station to the next, do your chosen stint there, and discipline and improve yourself by monitoring the overall torture time. Frankly, I find a much more pleasurable, though possibly less effective, regimen is tennis—singles, not doubles—played often and earnestly. An alternative, gentler on knees and backs, is running in place (and doing other fun exercises) on a small trampoline, indoors or out.

The finest conditioner for your lungs—probably even better than carrying loads—is, once again, running, especially up hills, up steep hills.

Because all the weight of a pack used to hang from the shoulders, people still connect backpacking with “sore shoulders.” There’s a certain residual truth in the idea: any but the very best modern packframes, properly adjusted, can leave unready shoulders a mite stiff. But with the hipbelt that is the crux of today’s pack suspension, it is on your hips that the real load bears. And, brother, does it bear! I go for sumptuously padded belts and I’m fairly often in harness, but I still find, on the second morning of most trips with heavy loads, that I wince as I cinch the belt tight—the way it must be cinched—on hip muscles still complaining about yesterday. And on that second morning, if not earlier, any hips that have never undergone the waistbelt trauma under a heavy load, or have not done so for a long time, are just about guaranteed, I hereby warn, to complain fortissimo.

CHIP: Besides sore muscles, another lookout is pressure sores. These appear where your bones protrude, often at the points of your pelvis, and are slow to heal on the trail. Padding helps, but having a hipbelt and yoke of the right size and cut helps even more (see this page). So does reducing your packweight.

When I was young I endured slings, arrows, and sores, and healed quickly, ready for more. But such wear and tear is cumulative. The present tendency (risking what threatens to become a minor jeremiad) is to think that you can simply buy your way out of this. Pressure sores? Get more padding. Aching feet? Buy stouter boots. But the practical limits of this strategy are clear, unless you also choose to hire a sedan chair, porters, and a cook.

The best course, which I discovered at length and Colin confirms, is to maintain a steady level of condition, whether through tennis, jogging, or climbing stairs, and then pile on a bit extra before a big trip. Not being much for running or tennis, my current favorite is pedaling a mountain bike on dirt roads at a heart-pounding clip.

When we last hiked, Colin would occasionally interrupt our rather brisk pace by excusing himself to dash up a hill, snorting like a bull, at an age when most men can only fart like one. So this is not a case of ipse dixit, but a well-proven pudding indeed.*5

COLIN: I’m afraid all these strictures end up sounding ferociously austere. But Arcadian ends can justify Spartan means. Many a beautiful backpacking week or weekend has been ruined at the start by crippled, city-soft muscles—because their owners had failed to recognize the softness, or at any rate to remedy it.

Harbor no illusions about how much difference fitness makes to backpacking. A study conducted at the University of Texas, El Paso, in 1974 indicated that physical fitness appears to be more closely related to pack-carrying performance than is either age or weight. I buy that.

There’s a certain forest to which I retreat from time to time for a two- or three-day think-and-therapy walk. Normally I go when mentally exhausted from work and muscularly out of practice. I start, mostly, in the evening. I am glad to camp a little way up the first, long hill and then to plod on next morning until I reach a little clearing on the first ridge, where I often stop to brew tea. Sometimes it is by then time for lunch. But once, in order to think out the shape of a book, I went to my forest only 10 days after returning from a week spent pounding up a Sierra Nevada mountain. I was fit and alert. And that purgatorial first hill flattened out in front of me. I stayed in high gear all the way; although I had as usual started toward the end of the day, I reached the ridge clearing in time to choose a campsite by the last of the day’s light.

So even if you can’t manage practice hikes, try to do something. Start early. Start easy. Work up. You may find that you actually enjoy what you’re doing, especially if you organize the right palliatives (hilltop lunches, subarboreal offices, daydreams, tennis). And when you stride away from the roadhead at last, out into Arcady, you will very likely discover that getting in shape has made the difference between agony and ecstasy.

Up high, your body works less efficiently, especially at first. There is wide variation: some people tolerate high altitude well, others poorly. And the more practiced you are, the better you tend to play the game. But current gospel maintains that physical condition has no effect—at least on the more serious forms of distress, known as “acute mountain sickness.” In fact, fitness may make you drive too hard, and so overtax your body.

Symptoms of what could properly be labeled “acute mountain sickness” rarely occur below 8000 feet. (For much, much more on that subject, see this page.) But if your body is tuned to operate at sea level you may well experience as low as 6000 feet enough mild initial distress, such as shortness of breath, to impair your efficiency and enjoyment. And a little higher you may begin to suffer headaches. You can dampen such distress almost to extinction if you acclimate correctly—that is, give your body time to make adjustments (mainly increasing the depth and rate of breathing) so that it can perform properly under the new conditions. If you’re making your first energetic trip into high mountains and don’t know what your threshold of tolerance will be, pay particular attention to this acclimation process.

The body does most of its adjusting in the first three days, with the first two the most important. So those are the days to watch. I seem to tolerate high altitude fairly well, at least up to 16,000 feet, but if I’m going over about 10,000 I take pains to arrange that I cannot get out of the car and immediately, with my body still tuned for sea level, start to walk toward those beckoning peaks. When checking gear at home I leave such details as rebagging food and waxing boots to be done at the roadhead. Other things being equal, I choose a roadhead as high as possible—at 6000 or 7000 feet or more. And I tend to drive until late at night to reach it. Sometimes I drive clear through the night. Then I more or less have to sleep up high for at least one night, or part of a night (or day); and by the time I’ve slept late and then gotten all my gear ready there’s normally only an hour or two of daylight left—just enough for a leisurely walk and then another night’s sleep up high before I can even begin serious walking.

Not everyone will want or even be able to apply my particular built-in brakes at the roadhead, but try to devise your own version. If time and terrain permit, it’s naturally better to start low and let the body adjust slowly, as you gain elevation. But the slope must be reasonable or the pace slow, or both. I know one family that on its first Sierra backpack trip ignored warnings and tried too much, too high, and too early, so that everyone suffered headaches and the other malaises of “mountain sickness” and came down vowing never to set pack on back again.