Chapter 7

Commitment and Consistency

I am today what I established yesterday or some previous day.

—James Joyce

Every year, Amazon ranks near or at the top of the wealthiest and best-performing companies in the world. Yet every year it gives each of its fulfillment-center employees, who helped the company reach these heights, an incentive of up to $5,000 to leave. The practice, in which employees receive a cash bonus if they quit, has left many observers mystified, as the costs of employee turnover are significant. Direct expenses associated with turnover of such employees—stemming from the recruitment, hiring, and training of replacements—can extend to 50 percent of the employee’s annual compensation package; plus, the costs escalate even further when indirect expenses are taken into account in the form of loss of institutional memory, productivity disruptions, and lowered morale of remaining team members.

How does Amazon justify its “Pay to Quit” program from a business standpoint? Spokesperson Melanie Etches is clear on the point: “We only want people working at Amazon who want to be here. In the long-run term, staying somewhere you don’t want to be isn’t healthy for our employees or for the company.” So Amazon figures that providing unhappy, dissatisfied, or discouraged employees an attractive escape route will save money in terms of the proven higher health costs and lower productivity of such workers. I don’t doubt the logic. But I do doubt it is Amazon’s sole rationale for the program. A significant additional reason applies. I know of its potency from the results of behavioral-science research and from the fact that I have seen it, and still do see it, operating forcefully all around me.

Take, for example, the story of my neighbor Sara and her live-in boyfriend, Tim. After they met, they dated for a while and eventually moved in together. Things were never perfect for Sara. She wanted Tim to marry her and stop his heavy drinking; Tim resisted both ideas. After an especially contentious period, Sara broke off the relationship, and Tim moved out. Around the same time, an old boyfriend phoned her. They started seeing each other exclusively and quickly became engaged. They had gone so far as to set a wedding date and issue invitations, when Tim called. He had repented and wanted to move back in. When Sara told him her marriage plans, he begged her to change her mind; he wanted to be together with her as before. Sara refused, saying she didn’t want to live like that again. Tim even offered to marry her, but she still said she preferred the other boyfriend. Finally, Tim volunteered to quit drinking if she would only relent. Feeling that under those conditions, Tim had the edge, Sara decided to break her engagement, cancel the wedding, retract the invitations, and have Tim move back in with her.

Within a month, Tim informed Sara that he didn’t think he needed to stop drinking, because he now had it under control. A month later, he decided that they should “wait and see” before getting married. Two years have since passed; Tim and Sara continue to live together exactly as before. Tim still drinks, and there are still no marriage plans, yet Sara is more devoted to him than ever. She says that being forced to decide taught her that Tim really is number one in her heart. So after choosing Tim over her other boyfriend, Sara became happier, even though the conditions under which she had made her decision have never been consummated.

Note that Sara’s bolstered commitment came from making a hard personal choice for Tim. I believe it’s for the same reason that Amazon wants employees to make such a choice for it. The election to stay or leave in the face of an incentive to quit doesn’t serve only to identify disengaged workers, who, in a smoothly efficient process, weed themselves out. It also serves to solidify and even enhance the allegiance of those who, like Sara, opt to continue.

How can we be so sure that this latter outcome is part of the Pay to Quit program’s purpose? By paying attention not to what the company’s public-relations spokesperson, Ms. Etches, has to say on the matter but, rather, to what its founder, Jeff Bezos, says—a man whose business acumen had made him the world’s richest person. In a letter to shareholders, Mr. Bezos wrote that the program’s purpose was simply to encourage employees “to take a moment and think about what they really want.” He’s also pointed out that the headline of the annual proposal memo reads, “Please Don’t Take This Offer.” Thus, Mr. Bezos wants employees to think about leaving without choosing to do so, which is precisely what happens, as very few take the offer. In my view, it’s the resultant decision to stay that the program is primarily designed to foster, and for good reason: employee commitment is highly related to employee productivity.

Mr. Bezos’s keen understanding of human psychology is confirmed in a raft of studies of people’s willingness to believe in the greater validity of a difficult selection once made. I have a favorite. A study done by a pair of Canadian psychologists uncovered something fascinating about people at the horse track. Just after placing bets, they become much more sure of the correctness of their decision than they were immediately before laying down the bets. Of course, nothing about the horse’s chances actually shifts; it’s the same horse, on the same track, in the same field; but in the minds of those bettors, their confidence that they made the right choice improves significantly once the decision is finalized. Similarly, in the political arena, voters believe more strongly in their choice immediately after casting a ballot. In yet another domain, upon making an active, public decision to conserve energy or water, people become more devoted to the idea of conservation, develop more reasons to support it, and work harder to achieve it.

In general, the main reason for such swings in the direction of a choice has to do with another fundamental principle of social influence. Like the other principles, this one lies deep within us, directing our actions with quiet power. It is our desire to be (and to appear) consistent with what we have already said or done. Once we make a choice or take a stand, we encounter personal and interpersonal pressures to think and behave consistently with that commitment. Moreover, those pressures will cause us to respond in ways that justify our decision.1

Streaming Along

Psychologists have long explored how the consistency principle guides human action. Indeed, prominent early theorists recognized the desire for consistency as a motivator of our behavior. But is it really strong enough to compel us to do what we ordinarily would not want to do? There is no question about it. The drive to be (and look) consistent constitutes a potent driving force, often causing us to act in ways contrary to our own best interest.

Consider what happened when researchers staged thefts on a New York City area beach to see if onlookers would risk personal harm to halt the crime. In the study, an accomplice of the researchers would put a beach blanket down five feet from the blanket of a randomly chosen individual—the experimental subject. After several minutes of relaxing on the blanket and listening to music from a portable radio, the accomplice would stand up and leave the blanket to stroll down the beach. Soon thereafter, a researcher, pretending to be a thief, would approach, grab the radio, and try to hurry away with it. Under normal conditions, subjects were reluctant to put themselves in harm’s way by challenging the thief—only four people did so in the twenty times the theft was staged. But when the same procedure was tried another twenty times with a slight twist, the results were drastically different. In these incidents, before leaving the blanket, the accomplice would simply ask the subject to please “watch my things,” something everyone agreed to do. Now, propelled by the rule of consistency, nineteen of the twenty subjects became virtual vigilantes, running after and stopping the thief, demanding an explanation, often restraining the thief physically or snatching the radio away.

To understand why consistency is so powerful a motive, we should recognize that in most circumstances, it is valued and adaptive. Inconsistency is commonly thought to be an undesirable personality trait. The person whose beliefs, words, and deeds don’t match is seen as confused, two-faced, even mentally ill. On the other side, a high degree of consistency is normally associated with personal and intellectual strength. It is the heart of logic, rationality, stability, and honesty. A quote attributed to the great British chemist Michael Faraday suggests the extent to which being consistent is approved—sometimes more than being right is. When asked after a lecture if he meant to imply that a hated academic rival was always wrong, Faraday glowered at the questioner and replied, “He’s not that consistent.”

Certainly, then, good personal consistency is highly valued in our culture—and well it should be. Most of the time, we are better off if our approach to things is well laced with consistency. Without it, our lives would be difficult, erratic, and disjointed.

The Quick Fix

Because it is typically in our best interests to be consistent, we fall into the habit of being automatically so, even in situations where it is not the sensible way to be. When it occurs unthinkingly, consistency can be disastrous. Nonetheless, even blind consistency has its attractions.

First, like most other forms of automatic responding, consistency offers a shortcut through the complexities of modern life. Once we have made up our minds about an issue, stubborn consistency allows us an appealing luxury: we don’t have to think hard about the issue anymore. We don’t have to sift through the blizzard of information we encounter every day to identify relevant facts; we don’t have to expend the mental energy to weigh the pros and cons; we don’t have to make any further tough decisions. Instead, all we have to do when confronted with the issue is click on our consistency program, and we know just what to believe, say, or do. We need only believe, say, or do whatever is congruent with our earlier decision.

The allure of such a luxury is not to be minimized. It allows us a convenient, relatively effortless, and efficient method for dealing with the complexities of daily life that make severe demands on our mental energies and capacities. It is not hard to understand, then, why automatic consistency is a difficult reaction to curb. It offers a way to evade the rigors of continuing thought. With our consistency programs running, we can go about our business happily excused from having to think too much. And, as Sir Joshua Reynolds noted, “There is no expedient to which a man will not resort to avoid the real labor of thinking.”

The Foolish Fortress

There is a second, more perverse attraction of mechanical consistency. Sometimes it is not the effort of hard, cognitive work that makes us shirk thoughtful activity but the harsh consequences of that activity. Sometimes it is the cursedly clear and unwelcome set of answers provided by straight thinking that makes us mental slackers. There are certain disturbing things we simply would rather not realize. Because it is a preprogrammed and mindless method of responding, automatic consistency can supply a safe hiding place from troubling realizations. Sealed within the fortress walls of rigid consistency, we can be impervious to the sieges of reason.

One night at an introductory lecture given by the Transcendental Meditation (TM) program, I witnessed an illustration of the way people hide inside the walls of consistency to protect themselves from the troublesome consequences of thought. The lecture itself was presided over by two earnest young men and was designed to recruit new members into the program. The men claimed the program offered a unique brand of meditation that would allow us to achieve all manner of desirable things, ranging from simple inner peace to more spectacular abilities—to fly and pass through walls, for example—at the program’s advanced (and more expensive) stages.

I had decided to attend the meeting to observe the kind of compliance tactics used in recruitment lectures of this sort and had brought along an interested friend, a university professor whose areas of specialization were statistics and symbolic logic. As the meeting progressed and the lecturers explained the theory behind TM, I noticed my logician friend becoming increasingly restless. Looking more and more pained and shifting about in his seat, he was finally unable to resist. When the leaders called for questions, he raised his hand and gently but surely demolished the presentation we had just heard. In less than two minutes, he pointed out precisely where and why the lecturers’ complex argument was contradictory, illogical, and unsupportable. The effect on the discussion leaders was devastating. After a confused silence, each attempted a weak reply only to halt midway to confer with his partner and finally to admit that my colleague’s points were good ones “requiring further study.”

More interesting to me was the effect upon the rest of the audience. At the end of the question period, the recruiters were faced with a crowd of audience members submitting their $75 down payments for admission to the TM program. Shrugging and chuckling to one another as they took in the payments, the recruiters betrayed signs of giddy bewilderment. After what appeared to have been an embarrassingly clear collapse of their presentation, the meeting had somehow turned into a success, generating inexplicably high levels of compliance from the audience. Although more than a bit puzzled, I chalked up the audience’s response to a failure to understand the logic of my colleague’s arguments. As it turned out, just the reverse was true.

Outside the lecture room after the meeting, we were approached by three members of the audience, each of whom had given a down payment immediately after the lecture. They wanted to know why we had come to the session. We explained and asked the same question of them. One was an aspiring actor who wanted desperately to succeed at his craft and had come to the meeting to learn if TM would allow him to achieve the necessary self-control to master the art; the recruiters assured him it would. The second described herself as a severe insomniac who hoped TM would provide her a way to relax and fall asleep easily at night. The third served as unofficial spokesman. He was failing his college courses because there wasn’t enough time to study. He had come to the meeting to find out if TM could help by training him to need fewer hours of sleep each night; the additional time could then be used for study. It is interesting to note that the recruiters informed him, as well as the insomniac, that TM techniques could solve their respective, though opposite, problems.

Still thinking the three must have signed up because they hadn’t understood the points made by my logician friend, I began to question them about aspects of his arguments. I found that they had understood his comments quite well, in fact, all too well. It was precisely the cogency of his claims that drove them to sign up for the program on the spot. The spokesman put it best: “Well, I wasn’t going to put down any money tonight because I’m really broke right now; I was going to wait until the next meeting. But when your buddy started talking, I knew I’d better give them my money now, or I’d go home, start thinking about what he said and never sign up.”

At once, things began to make sense. These were people with real problems, and they were desperately searching for a way to solve them. They were seekers who, if our discussion leaders were right, had found a potential solution in TM. Driven by their needs, they very much wanted to believe that TM was their answer. Now, in the form of my colleague, intrudes the voice of reason, showing the theory underlying their newfound solution to be unsound.

Panic! Something must be done at once before logic takes its toll and leaves them without hope once again. Quickly, quickly, walls against reason are needed, and it doesn’t matter that the fortress to be erected is a foolish one. “Quick, a hiding place from thought! Here, take this money. Whew, safe in the nick of time. No need to think about the issues any longer.” The decision has been made, and from now on the consistency program can be run whenever necessary: “TM? Certainly I think it will help me; certainly I expect to continue; certainly I believe in TM. I already put my money down for it, didn’t I?” Ah, the comforts of mindless consistency. “I’ll just rest right here for a while. It’s so much nicer than the worry and strain of that hard, hard search.”

Seek and Hide

If, as it appears, automatic consistency functions as a shield against thought, it should not be surprising that such consistency can be exploited by those who would prefer we respond to their requests without thinking. For the profiteers, whose interest will be served by an unthinking, mechanical reaction to their requests, our tendency for automatic consistency is a gold mine. So clever are they at arranging to have us run our consistency programs when it profits them that we seldom realize we have been taken. In fine jujitsu fashion, they structure their interactions with us so our need to be consistent leads directly to their benefit.

Certain large toy manufacturers use just such an approach to reduce a problem created by seasonal buying patterns. Of course, the boom time for toy companies occurs before and during the Christmas holiday season. Their problem is that toy sales then go into a terrible slump for the next couple of months. Their customers have already spent the amount in their toy budgets and are stiffly resistant to their children’s pleas for more.

The toy manufacturers are faced with a dilemma: how to keep sales high during the peak season and, at the same time, retain a healthy demand for toys in the immediately following months? The difficulty certainly doesn’t lie in motivating kids to want more toys after Christmas. The problem lies in motivating postholiday spent-out parents to buy another plaything for their already toy-glutted children. What could the toy companies do to produce that unlikely behavior? Some have tried greatly increased advertising campaigns, while others have reduced prices during the slack period, but neither of those standard sales devices has proved successful. Both tactics are costly and have been ineffective in increasing sales to desired levels. Parents are simply not in a toy-buying mood, and the influences of advertising or reduced expense are not enough to shake that stony resistance.

Certain large toy manufacturers think they have found a solution. It’s an ingenious one, involving no more than a normal advertising expense and an understanding of the powerful pull of the need for consistency. My first hint of the way the toy companies’ strategy worked came after I fell for it and then, in true patsy form, fell for it again.

It was January, and I was in the town’s largest toy store. After purchasing all too many gifts there for my son a month before, I had sworn not to enter that store or any like it for a long, long time. Yet there I was, not only in the diabolical place but also in the process of buying my son another expensive toy—a big, electric road-race set. In front of the road-race display, I happened to meet a former neighbor who was buying his son the same toy. The odd thing was that we almost never saw each other anymore. In fact, the last time had been a year earlier in the same store when we were both buying our sons an expensive post-Christmas gift—that time a robot that walked, talked, and laid waste to all before it. We laughed about our strange pattern of seeing each other only once a year at the same time, in the same place, while doing the same thing. Later that day, I mentioned the coincidence to a friend who, it turned out, had once worked in the toy business.

“No coincidence,” he said knowingly.

“What do you mean, ‘No coincidence’?”

“Look,” he said, “let me ask you a couple of questions about the road-race set you bought this year. First, did you promise your son that he’d get one for Christmas?”

“Well, yes, I did. Christopher had seen a bunch of ads for them on the Saturday-morning cartoon shows and said that was what he wanted for Christmas. I saw a couple of ads myself and it looked like fun, so I said, OK.”

“Strike one,” he announced. “Now for my second question. When you went to buy one, did you find all the stores sold out?”

“That’s right, I did! The stores said they’d ordered some but didn’t know when they’d get any more in. So I had to buy Christopher some other toys to make up for the road-race set. But how did you know?”

“Strike two,” he said. “Just let me ask one more question. Didn’t this same sort of thing happen the year before with the robot toy?”

“Wait a minute . . . you’re right. That’s just what happened. This is incredible. How did you know?”

“No psychic powers; I just happen to know how several of the big toy companies jack up their January and February sales. They start prior to Christmas with attractive TV ads for certain special toys. The kids, naturally, want what they see and extract Christmas promises for these items from their parents. Now here’s where the genius of the companies’ plan comes in: they undersupply the stores with the toys they’ve gotten the parents to promise. Most parents find those toys sold out and are forced to substitute other toys of equal value. The toy manufacturers, of course, make a point of supplying the stores with plenty of these substitutes. Then, after Christmas, the companies start running the ads again for the other, special toys. That jacks up the kids to want those toys more than ever. They go running to their parents whining, ‘You promised, you promised,’ and the adults go trudging off to the store to live up dutifully to their words.”

“Where,” I said, beginning to seethe now, “they meet other parents they haven’t seen for a year, falling for the same trick, right?”

“Right. Uh, where are you going?”

“I’m going to take the road-race set right back to the store.” I was so angry I was nearly shouting.

“Wait. Think for a minute first. Why did you buy it this morning?”

“Because I didn’t want to let Christopher down and because I wanted to teach him that promises are to be lived up to.”

“Well, has any of that changed? Look, if you take his toy away now, he won’t understand why. He’ll just know that his father broke a promise to him. Is that what you want?”

“No,” I said, sighing, “I guess not. So, you’re telling me the toy companies doubled their profits on me for the past two years, and I never even knew it; and now that I do, I’m still trapped—by my own words. So, what you’re really telling me is, ‘Strike three.’”

He nodded, “And you’re out.”

In the years since, I have observed a variety of parental toy-buying sprees similar to the one I experienced during that particular holiday season—for Beanie Babies, Tickle Me Elmo dolls, Furbies, Xboxes, Wii consoles, Zhu Zhu Pets, Frozen Elsa dolls, PlayStation 5s, and the like. But, historically, the one that best fits the pattern is that of the Cabbage Patch Kids, $25 dolls that were promoted heavily during mid-1980s Christmas seasons but were woefully undersupplied to stores. Some of the consequences were a government false-advertising charge against the Kids’ maker for continuing to advertise dolls that were not available, frenzied groups of adults battling at toy outlets or paying up to $700 apiece at auction for dolls they had promised their children, and an annual $150 million in sales that extended well beyond the Christmas months. During the 1998 holiday season, the least available toy everyone wanted was the Furby, created by a division of toy giant Hasbro. When asked what frustrated, Furby-less parents should tell their kids, a Hasbro spokeswoman advised the kind of promise that has profited toy manufacturers for decades: tell the kids, “I’ll try, but if I can’t get it for you now, I’ll get it for you later.”2

Figure 7.1: No pain, no (ill-gotten) gain

Jason, the gamer in this cartoon, has gotten the tactic for holiday-gift success right, but, I think he’s gotten the reason for that success wrong. My own experience tells me that his parents will overcompensate with other gifts not so much to ease his pain but to ease their own pain at having to break their promise to him.

FOXTROT © 2005 Bill Amend. Reprinted with permission of UNIVERSAL PRESS SYNDICATE. All rights reserved.

Commitment Is the Key

Once we realize that the power of consistency is formidable in directing human action, an important practical question immediately arises: How is that force engaged? What produces the click that activates the run of the powerful consistency program? Social psychologists think they know the answer: commitment. If I can get you to make a commitment (that is, to take a stand, to go on record), I will have set the stage for your automatic and ill-considered consistency with that earlier commitment. Once a stand is taken, there is a natural tendency to behave in ways that are stubbornly aligned with the stand.

As we’ve already seen, social psychologists are not the only ones who understand the connection between commitment and consistency. Commitment strategies are aimed at us by compliance professionals of nearly every sort. Each of the strategies is intended to get us to take some action or make some statement that will trap us into later compliance through consistency pressures. Procedures designed to create commitments take various forms. Some are bluntly straightforward; others are among the most subtle compliance tactics we will encounter. On the blunt side, consider the approach of Jack Stanko, used-car sales manager for an Albuquerque auto dealership. While leading a session called “Used Car Merchandising” at a National Auto Dealers Association convention in San Francisco, he advised one hundred sales-hungry dealers as follows: “Put ’em on paper. Get the customer’s OK on paper. Control ’em. Ask ’em if they would buy the car right now if the price is right. Pin ’em down.” Obviously, Mr. Stanko—an expert in these matters—believes that the way to customer compliance is through commitments, which serve to “control ’em.”

Commitment practices involving substantially more finesse can be just as effective. Suppose you wanted to increase the number of people in your area who would agree to go door to door collecting donations for your favorite charity. You would be wise to study the approach taken by social psychologist Steven J. Sherman. He simply called a sample of Bloomington, Indiana, residents as part of a survey he was taking and asked them to predict what they would say if asked to spend three hours collecting money for the American Cancer Society. Of course, not wanting to seem uncharitable to the survey-taker or to themselves, many of these people said that they would volunteer. The consequence of this subtle commitment procedure was a 700 percent increase in volunteers when, a few days later, a representative of the American Cancer Society did call and ask for neighborhood canvassers.

Using the same strategy, but this time asking citizens to predict whether they would vote on Election Day, other researchers have been able to increase significantly the turnout at the polls among those called. Courtroom combatants appear to have adopted this practice of extracting a lofty initial commitment designed to spur future consistent behavior. When screening potential jurors before a trial, Jo-Ellen Demitrius, reputed to be the best consultant in the business of jury selection, asks an artful question: “If you were the only person who believed in my client’s innocence, could you withstand the pressure of the rest of the jury to change your mind?” How could any self-respecting prospective juror say no? And having made the public promise, how could any self-respecting selected juror repudiate it later?

Perhaps an even more crafty commitment technique has been developed by telephone solicitors for charity. Have you noticed that callers asking you to contribute to some cause or another these days seem to begin things by inquiring about your current health and well-being? “Hello, Mr./Ms. Targetperson,” they say. “How are you feeling this evening?,” or “How are you doing today?” The caller’s intent with this sort of introduction is not merely to seem friendly and caring. It is to get you to respond—as you normally do to such polite, superficial inquiries—with a polite, superficial comment of your own: “Just fine” or “Real good” or “Doing great, thanks.” Once you have publicly stated that all is well, it becomes much easier for the solicitor to corner you into aiding those for whom all is not well: “I’m glad to hear that because I’m calling to ask if you’d be willing to make a donation to help the unfortunate victims of . . .”

The theory behind this tactic is that people who have just asserted that they are doing/feeling fine—even as a routine part of a sociable exchange—will consequently find it awkward to appear stingy in the context of their own admittedly favorable circumstances. If all this sounds a bit far-fetched, consider the findings of consumer researcher Daniel Howard, who put the theory to the test. Residents of Dallas, Texas, were called on the phone and asked if they would agree to allow a representative of the Hunger Relief Committee to come to their homes to sell them cookies, the proceeds from which would be used to supply meals for the needy. When tried alone, that request (labeled the standard solicitation approach) produced only 18 percent agreement. However, if the caller initially asked, “How are you feeling this evening?” and waited for a reply before proceeding with the standard approach, several noteworthy things happened. First, of the 120 individuals called, most (108) gave the customary favorable reply (“Good,” “Fine,” “Real well,” etc.). Second, 32 percent of the people who got the “How are you feeling this evening?” question agreed to receive the cookie seller at their homes, nearly twice the success rate of the standard solicitation approach. Third, true to the consistency principle, almost everyone (89 percent) who agreed to such a visit did in fact make a cookie purchase when contacted at home.

There is still another behavioral arena, sexual infidelity, in which relatively small verbal commitments can make a substantial difference. Psychologists warn that cheating on a romantic partner is a source of great conflict, often leading to anger, pain, and termination of the relationship. They’ve also located an activity to help prevent the occurrence of this destructive sequence: prayer—not prayer in general, though, but of a particular kind. If one romantic partner agrees to say a brief prayer for the other’s well-being every day, he or she becomes less likely to be unfaithful during the period of time while doing so. After all, such behavior would be inconsistent with daily active commitments to the partner’s welfare.3

READER’S REPORT 7.1

From a sales trainer in Texas

The most powerful lesson I ever learned from your book was about commitment. Years ago, I trained people at a telemarketing center to sell insurance over the phone. Our main difficulty, however, was that we couldn’t actually SELL insurance over the phone; we could only quote a price and then direct the caller to the company office nearest their home. The problem was callers who committed to office appointments but didn’t show up.

I took a group of new training graduates and modified their sales approach from that used by other salespeople. They used the exact same “canned” presentation as the others but included an additional question at the end of the call. Instead of simply hanging up when the customer confirmed an appointment time, we instructed the salespeople to say, “I was wondering if you would tell me exactly why you’ve chosen to purchase your insurance with <our company>.”

I was initially just attempting to gather customer service information, but these new sales associates generated nearly 19 percent more sales than other new salespeople. When we integrated this question into everyone’s presentations, even the old pros generated over 10 percent more business than before. I didn’t fully understand why this worked before.

Author’s note: Although accidentally employed, this reader’s tactic was masterful because it didn’t simply commit customers to their choice; it also committed them to the reasons for their choice. And, as we’ve seen in chapter 1, people often behave for the sake of reasons (Bastardi & Shafir, 2000; Langer, 1989).

The tactic’s effectiveness fits with the account of an Atlanta-based acquaintance of mine who—despite following standard advice to describe fully all the good reasons he should be hired—was having no success in job interviews. To change this outcome, he began employing the consistency principle on his own behalf. After assuring evaluators he wanted to answer all their questions as fully as possible, he added, “But, before we start, I wonder if you could answer a question for me. I’m curious, what was it about my background that attracted you to my candidacy?” As a consequence, his evaluators heard themselves saying positive things about him and his qualifications, committing themselves to reasons to hire him before he had to make the case himself. He swears he has gotten three better jobs in a row by employing this technique.

Imprisonments, Self-Imposed

The question of what makes a commitment effective has numerous answers. A variety of factors affects the ability of a commitment to constrain future behavior. One large-scale program designed to produce compliance illustrates how several of the factors work. The remarkable thing about the program is that it was systematically employing these factors over a half-century ago, well before scientific research had identified them.

During the Korean War, many captured American soldiers found themselves in prisoner-of-war camps run by the Chinese Communists. It became clear early in the conflict that the Chinese treated captives quite differently than did their allies, the North Koreans, who favored harsh punishment to gain compliance. Scrupulously avoiding brutality, the Red Chinese engaged in what they termed their “lenient policy,” which was, in reality, a concerted and sophisticated psychological assault on their captives.

After the war, American psychologists questioned the returning prisoners intensively to determine what had occurred, in part because of the unsettling success of some aspects of the Chinese program. The Chinese were very effective in getting Americans to inform on one another, in striking contrast to the behavior of American POWs in World War II. For this reason, among others, escape plans were quickly uncovered and the escapes themselves almost always unsuccessful. “When an escape did occur,” wrote psychologist Edgar Schein, a principal American investigator of the Chinese indoctrination program in Korea, “the Chinese usually recovered the man easily by offering a bag of rice to anyone turning him in.” In fact, nearly all American prisoners in the Chinese camps are said to have collaborated with the enemy in one way or another.

An examination of the prison-camp program shows that the Chinese relied heavily on commitment and consistency pressures. Of course, the first problem facing the Chinese was to get any collaboration at all from the Americans. The prisoners had been trained to provide nothing but name, rank, and serial number. Short of physical brutalization, how could the captors hope to get such men to give military information, turn in fellow prisoners, or publicly denounce their country? The Chinese answer was elementary: start small and build.

For instance, prisoners were frequently asked to make statements so mildly anti-American or pro-Communist that they seemed inconsequential (such as “The United States is not perfect” and “In a Communist country, unemployment is not a problem”). Once these minor requests had been complied with, however, the men found themselves pushed to submit to related, yet more substantive, requests. A man who had just agreed with his Chinese interrogator that the United States was not perfect might then be asked to indicate some of the ways he believed this was the case. Once he had so explained, he might be asked to make a list of these “problems with America” and sign his name to it. Later, he might be asked to read his list in a discussion group with other prisoners. “After all, it’s what you believe, isn’t it?” Still later, he might be asked to write an essay expanding on his list and discussing these problems in greater detail.

The Chinese might then use his name and his essay in an anti-American radio broadcast beamed not only to the entire camp but to other POW camps in North Korea as well as to American forces in South Korea. Suddenly he would find himself a “collaborator,” having given aid and comfort to the enemy. Aware that he had written the essay without any strong threats or coercion, many times a man would change his self-image to be consistent with the deed and with the “collaborator” label, which often resulted in even more extensive acts of collaboration. Thus, while “only a few men were able to avoid collaboration altogether,” according to Schein, “the majority collaborated at one time or another by doing things which seemed to them trivial but which the Chinese were able to turn to their own advantage. . . . This was particularly effective in eliciting confessions, self-criticism, and information during interrogation.”

Other groups of people interested in compliance are also aware of the usefulness and power of this approach. Charitable organizations, for instance, will often use progressively escalating commitments to induce individuals to perform major favors. The trivial first commitment of agreeing to be interviewed can begin a “momentum of compliance” that induces such later behaviors as organ or bone-marrow donations.

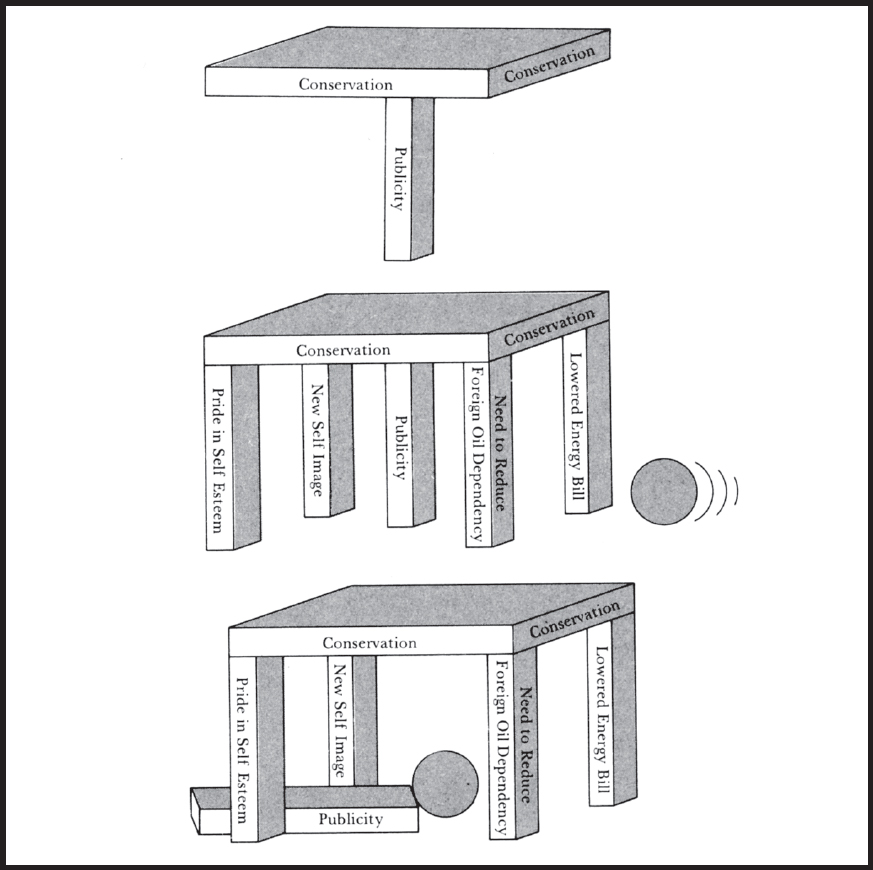

Figure 7.2: Start small and build.

Pigs like mud. But they don’t eat it. For that, escalating commitments seem needed.

© Paws. Used by permission.

Many business organizations employ this approach regularly as well. For the salesperson, the strategy is to obtain a large purchase by starting with a small one. Almost any small sale will do because the purpose of that small transaction is not profit, it’s commitment. Further purchases, even much larger ones, are expected to flow naturally from the commitment. An article in the trade magazine American Salesman put it succinctly:

The general idea is to pave the way for full-line distribution by starting with a small order. . . . Look at it this way—when a person has signed an order for your merchandise, even though the profit is so small it hardly compensates for the time and effort of making the call, he is no longer a prospect—he is a customer. (Green, 1965, p. 14)

The tactic of starting with a little request in order to gain eventual compliance with related larger requests has a name: the foot-in-the-door technique. Social scientists first became aware of its effectiveness when psychologists Jonathan Freedman and Scott Fraser published an astonishing data set. They reported the results of an experiment in which a researcher, posing as a volunteer worker, had gone door to door in a residential California neighborhood making a preposterous request of homeowners. The homeowners were asked to allow a public-service billboard to be installed on their front lawns. To get an idea of the way the sign would look, they were shown a photograph depicting an attractive house, the view of which was almost completely obscured by a large, poorly lettered sign reading Drive Carefully. Although the request was normally and understandably refused by the great majority of the residents in the area (only 17 percent complied), one particular group of people reacted quite favorably. A full 76 percent of them offered the use of their front yards.

The prime reason for their startling compliance was a small commitment to driver safety that they had made two weeks earlier. A different “volunteer worker” had come to their doors and asked them to accept and display a little three-inch-square sign that read Be a Safe Driver. It was such a trifling request that nearly all of them had agreed, but the effects of that request were striking. Because they had innocently complied with a trivial safe-driving request a couple of weeks before, these homeowners became remarkably willing to comply with another such request that was massive in size.

Freedman and Fraser didn’t stop there. They tried a slightly different procedure on another sample of homeowners. These people first received a request to sign a petition that favored “keeping California beautiful.” Of course, nearly everyone signed because state beauty, like efficiency in government or sound prenatal care, is one of those issues no one opposes. After waiting about two weeks, Freedman and Fraser sent a new “volunteer worker” to these same homes to ask the residents to allow the big Drive Carefully sign to be erected on their lawns. In some ways, the response of these homeowners was the most astounding of any in the study. Approximately half consented to the installation of the Drive Carefully billboard, even though the small commitment they had made weeks earlier was not to driver safety but to an entirely different public-service topic, state beautification.

At first, even Freedman and Fraser were bewildered by their findings. Why should the little act of signing a petition supporting state beautification cause people to be so willing to perform a different and much larger favor? After considering and discarding other explanations, the researchers came upon one that offered a solution to the puzzle: signing the beautification petition changed the view these people had of themselves. They saw themselves as public-spirited citizens who acted on their civic principles. When, two weeks later, they were asked to perform another public service by displaying the Drive Carefully sign, they complied in order to be consistent with their newly formed self-images. According to Freedman and Fraser:

What may occur is a change in the person’s feelings about getting involved or taking action. Once he has agreed to a request, his attitude may change, he may become, in his own eyes, the kind of person who does this sort of thing, who agrees to requests made by strangers, who takes action on things he believes in, who cooperates with good causes.

Figure 7.3: Just sign on the plotted line.

Author’s note: Have you ever wondered what the groups that ask you to sign their petitions do with all the signatures they obtain? Most of the time, the groups use them for genuinely stated purposes, but often they don’t do anything with them, as the principal purpose of the petition may simply be to get the signers committed to the group’s position and, consequently, more willing to take future steps that are aligned with it.

Psychology professor Sue Frantz described witnessing a sinister version of the tactic on the streets of Paris, where tourists are approached by a scammer and asked to sign a petition “to support people who are deaf and mute.” Those who sign are then immediately asked to make a donation, which many do to stay consistent with the cause they’ve just endorsed. Because the operation is a scam, no donation goes to charity—only to the scammer. Worse, an accomplice of the petitioner observes where, in their pockets or bags, the tourists reach for their wallets and targets them for subsequent pickpocket theft.

iStock Photo

Freedman and Fraser’s findings tell us to be very careful about agreeing to trivial requests because that agreement can influence our self-concepts. Such an agreement can not only increase our compliance with very similar, much larger requests but also make us more willing to perform a variety of larger favors that are only remotely connected to the little favor we did earlier. It’s this second kind of influence concealed within small commitments that scares me.

It scares me enough that I am rarely willing to sign a petition anymore, even for a position I support. The action has the potential to influence not only my future behavior but also my self-image in ways I may not want. Further, once a person’s self-image is altered, all sorts of subtle advantages become available to someone who wants to exploit the new image.

Who among Freedman and Fraser’s homeowners would have thought the “volunteer worker” who asked them to sign a state-beautification petition was really interested in having them display a safe-driving billboard two weeks later? Who among them could have suspected their decision to display the billboard was largely a result of signing that petition? No one, I’d guess. If there were any regrets after the billboard went up, who could they conceivably hold responsible but themselves and their own damnably strong civic spirits? They probably never considered the guy with the “keeping California beautiful” petition and all that knowledge of social jujitsu.4

Hearts and Minds

Every time you make a choice, you are turning the central part of you, the part that chooses, into something a little different from what it was before.

—C. S. Lewis

Notice that all of the foot-in-the-door experts seem to be excited about the same thing: you can use small commitments to manipulate a person’s self-image; you can use them to turn citizens into “public servants,” prospects into “customers,” and prisoners into “collaborators.” Once you’ve got a person’s self-image where you want it, that person should comply naturally with a whole range of requests aligned with this new self-view.

Not all commitments affect self-image equally, however. There are certain conditions that should be present for commitments to be most effective in this way: they should be active, public, effortful, and freely chosen. The major intent of the Chinese was not simply to extract information from their prisoners. It was to indoctrinate them, to change their perceptions of themselves, of their political system, of their country’s role in the war, and of communism. Dr. Henry Segal, chief of the neuropsychiatric evaluation team that examined returning POWs at the end of the Korean War, reported that war-related beliefs had been substantially shifted. Significant inroads had been made in the men’s political attitudes:

Many expressed antipathy toward the Chinese Communists but at the same time praised them for “the fine job they had done in China.” Others stated that “although communism won’t work in America, I think it’s a good thing for Asia.” (Segal, 1954, p. 360)

It appears that the real goal of the Chinese was to modify, at least for a time, the hearts and minds of their captives. If we measure their achievement in terms of “defection, disloyalty, changed attitudes and beliefs, poor discipline, poor morale, poor esprit, and doubts as to America’s role,” Segal concluded, “their efforts were highly successful.” Let’s examine more closely how they managed it.

The Magic Act

Our best evidence of people’s true feelings and beliefs comes less from their words than from their deeds. Observers trying to decide what people are like look closely at their actions. People also use this evidence—their own behavior—to decide what they are like; it is a key source of information about their own beliefs, values, attitudes, and, crucially, what they want to do next. Online sites often want visitors to register by providing information about themselves. But 86 percent of users report that they sometimes quit the registration process because the form is too long or prying. What have site developers done to overcome this barrier without reducing the amount of information they get from customers? They’ve reduced the average number of fields of requested information on the form’s first page. Why? They want to give users the feeling of having started and finished the initial part of the process. As design consultant Diego Poza put it, “It doesn’t matter if the next page has more fields to fill out (it does), due to the principle of commitment and consistency, users are much more likely to follow through.” The available data have proved him right: Just reducing the number of first-page fields from four to three increases registration completions by 50 percent.

The rippling impact of behavior on self-concept and future behavior can be seen in research into the effect of active versus passive commitments. In one study, college students volunteered for an AIDS-education project in local schools. The researchers arranged for half to volunteer actively, by filling out a form stating that they wanted to participate. The other half volunteered passively, by failing to fill out a form stating that they didn’t want to participate. Three to four days later, when asked to begin their volunteer activity, the great majority (74 percent) who appeared for duty came from the ranks of those who had actively agreed. What’s more, those who volunteered actively were more likely to explain their decisions by implicating their personal values, preferences, and traits. In all, it seems that active commitments give us the kind of information we use to shape our self-image, which then shapes our future actions, which solidify the new self-image.

Understanding fully this route to altered self-concept, the Chinese set about arranging the prison-camp experience so their captives would consistently act in desired ways. Before long, the Chinese knew, these actions would begin to take their toll, causing the prisoners to change their views of themselves to fit with what they had done.

Writing was one sort of committing action that the Chinese urged incessantly upon the captives. It was never enough for prisoners to listen quietly or even agree verbally with the Chinese line; they were always pushed to write it down as well. Edgar Schein (1956) describes a standard indoctrination-session tactic of the Chinese:

A further technique was to have the man write out the question and then the [pro-Communist] answer. If he refused to write it voluntarily, he was asked to copy it from the notebooks, which must have seemed like a harmless enough concession. (p. 161)

Oh, those “harmless” concessions. We’ve already seen how apparently trifling commitments can lead to further consistent behavior. As a commitment device, a written declaration has great advantages. First, it provides physical evidence that an act has occurred. Once a prisoner wrote what the Chinese wanted, it was difficult for him to believe he had not done so. The opportunities to forget or to deny to himself what he had done were not available, as they are for purely spoken statements. No; there it was in his own handwriting, an irrevocably documented act driving him to make his beliefs and his self-image consistent with what he had undeniably done. Second, a written testament can be shown to others. Of course, that means it can be used to persuade those others. It can persuade them to change their attitudes in the direction of the statement. More importantly for the purpose of commitment, it can persuade them the author genuinely believes what was written.

People have a natural tendency to think a statement reflects the true attitude of the person who made it. What is surprising is that they continue to think so even when they know the person did not freely choose to make the statement. Some scientific evidence that this is the case comes from a study by psychologists Edward Jones and James Harris, who showed people an essay favorable to Fidel Castro and asked them to guess the true feelings of its author. Jones and Harris told some of these people that the author had chosen to write a pro-Castro essay; they told other people that the author had been required to write in favor of Castro. The strange thing was that even those who knew that the author had been assigned to do a pro-Castro essay guessed the writer liked Castro. It seems a statement of belief produces a click, run response in those who view it. Unless there is strong evidence to the contrary, observers automatically assume someone who makes such a statement means it.

Think of the double-barreled effects on the self-image of a prisoner who wrote a pro-Chinese or anti-American statement. Not only was it a lasting personal reminder of his action, but it was likely to persuade those around him that it reflected his actual beliefs. As we saw in chapter 4, what those around us think is true of us importantly determines what we ourselves think. For example, one study found that a week after hearing they were considered charitable people by their neighbors, people gave much more money to a canvasser from the Multiple Sclerosis Association. Apparently the mere knowledge that others viewed them as charitable caused the individuals to make their actions congruent with that view.

A study in the fruit and vegetable section of a Swedish supermarket obtained a similar result. Customers in the section saw two separate bins of bananas, one labeled as ecologically grown and one without an ecological label. Under these circumstances, the ecological versions were chosen 32 percent of the time. Two additional samples of shoppers saw a sign between the two bins. For one sample, the sign that marketed the ecological bananas on price, “Ecological bananas are the same price as competing bananas,” increased the purchase rate to 46 percent. For the final sample of customers, the sign that marketed the ecological bananas by assigning the shoppers an environmentally friendly public image, “Hello Environmentalists, our ecological bananas are right here,” raised the purchase rate of ecological bananas to 51 percent.

Savvy politicians have long used the committing character of labels to great advantage. One of the best at it was former president of Egypt Anwar Sadat. Before international negotiations began, Sadat would assure his bargaining opponents that they and the citizens of their country were widely known for their cooperativeness and fairness. With this kind of flattery, he not only created positive feelings but also connected his opponent’s identities to a course of action that served his goals. According to master negotiator Henry Kissinger, Sadat was successful because he got others to act in his interests by giving them a reputation to uphold.

Once an active commitment is made, then, self-image is squeezed from both sides by consistency pressures. From the inside, there is a pressure to bring self-image into line with action. From the outside, there is a sneakier pressure—a tendency to adjust this image according to the way others perceive us.

Because others see us as believing what we have written (even when we’ve had little choice in the matter), we experience a pull to bring self-image into line with the written statement. In Korea, several subtle devices were used to get prisoners to write, without direct coercion, what the Chinese wanted. For example, the Chinese knew many prisoners were anxious to let their families know they were alive. At the same time, the men knew their captors were censoring the mail and only some letters were being allowed out of camp. To ensure their own letters would be released, some prisoners began including in their messages peace appeals, claims of kind treatment, and statements sympathetic to communism. Their hope was the Chinese would want such letters to surface and would, therefore, allow their delivery. Of course, the Chinese were happy to cooperate because those letters served their interests marvelously. First, their worldwide propaganda effort benefited from the appearance of pro-Communist statements by American servicemen. Second, for purposes of prisoner indoctrination, the Chinese had, without raising a finger of physical force, gotten many men to go on record supporting the Communist cause.

A similar technique involved political-essay contests regularly held in camp. The prizes for winning were invariably small—a few cigarettes or a bit of fruit—but sufficiently scarce that they generated a lot of interest from the men. Usually the winning essay took a solidly pro-Communist stand . . . but not always. The Chinese were wise enough to realize that most prisoners would not enter a contest they thought they could win only by writing a Communist tract. Moreover, the Chinese were clever enough to know how to plant in captives small commitments to communism that could be nurtured into later bloom. So, occasionally, the winning essay was one that generally supported the United States but bowed once or twice to the Chinese view.

The effects of the strategy were exactly what the Chinese wanted. The men continued to participate voluntarily in the contests because they saw they could win with essays highly favorable to their own country. Perhaps without realizing it, though, they began shading their essays a bit toward communism in order to have a better chance of winning. The Chinese were ready to pounce on any concession to Communist dogma and to bring consistency pressures to bear upon it. In the case of a written declaration within a voluntary essay, they had a perfect commitment from which to build toward collaboration and conversion.

Other compliance professionals also know about the committing power of written statements. The enormously successful Amway corporation, for instance, has a way to spur their sales personnel to greater and greater accomplishments. Members of the staff are asked to set individual sales goals and commit themselves to those goals by personally recording them on paper:

One final tip before you get started: Set a goal and write it down. Whatever the goal, the important thing is that you set it, so you’ve got something for which to aim—and that you write it down. There is something magical about writing things down. So set a goal and write it down. When you reach that goal, set another and write that down. You’ll be off and running.

If the Amway people have found “something magical about writing things down,” so have other business organizations. Some door-to-door sales companies used the magic of written commitments to battle the “cooling off” laws of many states. The laws are designed to allow customers a few days after agreeing to purchase an item to cancel the sale and receive a full refund. At first this legislation hurt the hard-sell companies deeply. Because they emphasize high-pressure tactics, their customers often bought, not because they wanted the products but because they were tricked or intimidated into the sale. When the laws went into effect, these customers began canceling in droves during the cooling-off period.

The companies quickly learned a simple trick that cut the number of such cancellations markedly. They had the customer, rather than the salesperson, fill out the sales agreement. According to the sales-training program of a prominent encyclopedia company, that personal commitment alone proved to be “a very important psychological aid in preventing customers from backing out of their contracts.” Like the Amway corporation, these organizations found that something special happens when people put their commitments on paper: they live up to what they write down.

Figure 7.4: Writing is believing.

This ad invites readers to participate in a sweepstakes by providing a handwritten message detailing the product’s favorable features.

Courtesy of Schieffelin & Co.

Another common way for businesses to cash in on the “magic” of written declarations occurs through the use of an innocent-looking promotional device. Growing up, I used to wonder why big companies such as Procter & Gamble and General Foods were always running 25-, 50-, or 100-words or less testimonial contests. They all seemed alike. A contestant was to compose a short personal statement beginning with the words, “I like [the product] because . . .” and go on to laud the features of whatever cake mix or floor wax happened to be at issue. The company judged the entries and awarded prizes to the winners. What puzzled me was what the companies got out of the deal. Often the contest required no purchase; anyone submitting an entry was eligible. Yet the companies appeared willing to incur the costs of contest after contest.

I am no longer puzzled. The purpose behind testimonial contests—to get as many people as possible to endorse a product—is akin to the purpose behind the political-essay contests in Korea: to get endorsements for Chinese communism. In both instances, the process is the same. Participants voluntarily write essays for attractive prizes they have only a small chance to win. They know that for an essay to have any chance of winning, it must include praise for the product. So they search for praiseworthy features, and they describe them in their essays. The result is hundreds of POWs in Korea or hundreds of thousands of people in America who testify in writing to the products’ appeal and who, consequently, experience the magical pull to believe what they have written.5

READER’S REPORT 7.2

From the creative director of a large international advertising agency

In the late 1990s, I asked Fred DeLuca, the founder and CEO of Subway restaurants, why he insisted in putting the prediction “10,000 stores by 2001” on the napkins in every single Subway. It didn’t seem to make sense, as I knew he was a long way from his goal, that consumers didn’t really care about his plan, and his franchisees were deeply troubled by the competition associated with such a goal. His answer was, “If I put my goals down in writing and make them known to the world, I’m committed to achieving them.” Needless to say, he not only has, he’s exceeded them.

Author’s note: As of January 1, 2021, Subway was on schedule to have 38,000 restaurants in 111 countries. So, as we will also see in the next section, written down and publicly made commitments can be used not only to influence others in desirable ways but to influence ourselves similarly.

The Public Eye

One reason written testaments are effective in bringing about genuine personal change is that they can so easily be made public. The prisoner experience in Korea showed the Chinese to be aware of an important psychological principle: public commitments tend to be lasting commitments. The Chinese constantly arranged to have pro-Communist statements of their captives seen by others. They were posted around camp, read by the author to a prisoner discussion group, or even read on a radio broadcast. As far as the Chinese were concerned, the more public the better.

Whenever one takes a stand visible to others, there arises a drive to maintain that stand in order to look like a consistent person. Remember that earlier in this chapter I described how desirable good personal consistency is as a trait; how someone without it may be judged as fickle, uncertain, pliant, scatterbrained, or unstable; how someone with it is viewed as rational, assured, trustworthy, and sound? Thus, it’s hardly surprising that people try to avoid the look of inconsistency. For appearances’ sake, the more public a stand, the more reluctant we are to change it.

EBOX 7.1

HOW TO CHANGE YOUR LIFE

By Alicia Morga

Owen Thomas wrote in an amazed tone in The New York Times recently how he managed to lose 83 pounds using a mobile app. He used MyFitnessPal. The developers of the app discovered that users who exposed their calorie counts to friends lost 50% more weight than a typical user.

It seems obvious that a social network can help you make a change, but it is less clear how. Many cite social proof—looking to others for how to behave—as influential, but what better explains transformation is commitment and consistency.

The more public our commitment, the more pressure we feel to act according to our commitment and therefore appear consistent. It can become a virtuous (or destructive) cycle as according to Robert Cialdini, “you can use small commitments to manipulate a person’s self-image” and once you change a person’s self-image you can get that person to behave in accordance with that new image—anything that would be consistent with this new view of herself.

So want to change your life? Make a specific commitment, use social media to broadcast it and use the internal pressure you then feel to get you to follow through. This in turn should cause you to see yourself in a new way and therefore keep you continuing to follow through.

While Mr. Thomas’ experience demonstrates the power of this theory as applied to dieting, I see the possible applications everywhere. Like say struggling Hispanic high school students (they have the highest high school drop-out rate). Why not get them to publicly commit to going to college? Might more then go? There should be an app for that.

Author’s note: In this blog post, its author judges correctly that even though peer pressure was involved, the principle that produced desired change for Mr. Thomas was not social proof. It was commitment and consistency. What’s more, the effective commitment was public, which fits with research showing that commitments to weight-loss goals are increasingly successful—in both the short and long term—when they become increasingly public (Nyer & Dellande, 2010).

An illustration of the way public commitments can lead to consistent further action was provided in a famous experiment performed by two prominent social psychologists, Morton Deutsch and Harold Gerard. The basic procedure was to have college students first estimate in their minds the length of lines they were shown. Then, one sample of the students had to commit publicly to their initial judgments by writing their estimates down, signing their names to them, and turning them in to the experimenter. A second sample also committed themselves to their first estimates, but did so privately by writing them down and then erasing them before anyone could see what they had written. A third set of students did not commit themselves to their initial estimates at all; they just kept the estimates in mind privately.

In these ways, Deutsch and Gerard cleverly arranged for some students to commit publicly, some privately, and some not at all, to their initial decisions. The researchers wanted to find out which of the three types of students would be most inclined to stick with their first judgments after receiving information that those judgments were incorrect. Therefore, all the students were given new evidence suggesting their initial estimates were wrong, and they were then given the chance to change their estimates.

The students who had never written down their first choices were the least loyal to those choices. When new evidence was presented that questioned the wisdom of decisions that had never left their heads, these students were the most influenced to change what they had viewed as the “correct” decision. Compared to the uncommitted students, those who had merely written their decisions for a moment were significantly less willing to change their minds when given the chance. Even though they had committed themselves under anonymous circumstances, the act of writing down their first judgments caused them to resist the influence of contradictory new data and to remain congruent with their preliminary choices. However, by far, it was the students who had publicly recorded their initial positions who most resolutely refused to shift from those positions later. Public commitments had hardened them into the most stubborn of all.

This sort of stubbornness can occur even in situations in which accuracy should be more important than consistency. In one study, when six-or twelve-person experimental juries were deciding a close case, hung juries were significantly more frequent if the jurors had to express their opinions with a visible show of hands rather than by secret ballot. Once jurors had stated their initial views publicly, they were reluctant to allow themselves to change publicly. Should you ever find yourself the foreperson of a jury under these conditions, you could reduce the risk of a hung jury by choosing a secret rather than public balloting method.

The finding that we are truest to our decisions if we have bound ourselves to them publicly can be put to good use. Consider organizations dedicated to helping people rid themselves of bad habits. Many weight-reduction clinics, for instance, understand that often a person’s private decision to lose weight will be too weak to withstand the blandishments of bakery windows, wafting cooking scents, and pizza-delivery commercials. So they see to it that the decision is buttressed by the pillars of public commitment. They require clients to write down an immediate weight-loss goal and show that goal to as many friends, relatives, and neighbors as possible. Clinic operators report this simple technique frequently works where all else has failed.

Of course, there’s no need to pay a special clinic in order to engage a visible commitment as an ally. One San Diego woman described to me how she employed a public promise to help herself finally stop smoking. She bought a set of blank business cards and wrote on the back of each, “I promise you I’ll never smoke another cigarette.” She then gave a signed card to “all the people in my life I really wanted to respect me.” Whenever she felt a need to smoke thereafter, she said she’d think of how those people would think less of her if she broke her promise to them. She never had another smoke. These days, behavior-change apps linked to our social networks allow us employ this self-influence technique within a much larger set of friends than a few business cards could reach.6 See, for example, eBox 7.1.

READER’S REPORT 7.3

From a Canadian university professor

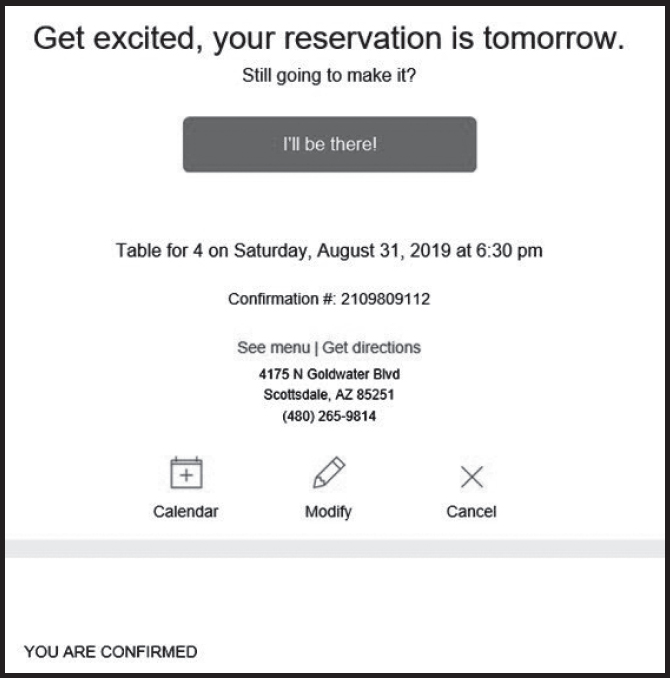

I just read a newspaper article on how a restaurant owner used public commitments to solve a big problem of “no-shows” (customers who don’t show up for their table reservations). I don’t know if he read your book or not first, but he did something that fits perfectly with the commitment/consistency principle you talk about. He told his receptionists to stop saying, “Please call us if you change your plans,” and to start asking, “Will you please call us if you change your plans?” and to wait for a response. His no-show rate immediately went from 30 percent to 10 percent. That’s a 67 percent drop.

Author’s note: What was it about this subtle shift that led to such a dramatic difference? For me, it was the receptionist’s request for (and pause for) the caller’s promise. By spurring patrons to make a public commitment, this approach increased the chance that they would follow through on it. By the way, the astute proprietor was Gordon Sinclair of Gordon’s restaurant in Chicago. eBox 7.2 provides the online version of this tactic.

EBOX 7.2

Author’s note: Today, restaurants are reducing reservation no-shows by asking customers to make active and public commitments online before the date of their reservation. Recently, my doctor’s office began doing the same, with one additional compliance-enhancing element. In the confirmation email, I was given a reason by the nurse for my active, public commitment: “By telling me if you can or cannot make it, you help make sure that all patients are getting the care they need.” When I inquired about the success of the online confirmation program, the doctor’s office manager told me it had reduced no-shows by 81 percent.

The Effort Extra

The evidence is clear: the more effort that goes into a commitment, the greater its ability to influence the attitudes and actions of the person who made it. We can find that evidence in settings as close by as our homes and schools or as far away as remote regions of the world.

Let’s begin nearer to home with the requirements of many localities for residents to separate their household trash for pro-environmental disposal. These requirements can differ in the effort needed for correct disposal. This is the case in Hangzhou, China, where the steps for proper separation and disposal are more arduous in some sections of the city than in others. After informing residents of the environmental benefits of proper disposal, researchers there wanted to see if residents who had to work harder to live up to environmental standards would become more committed to the environment in general, as shown by also taking the pro-environmental action of reducing their household electricity consumption. That’s what happened. Residents who had to work harder to support the environment via household-waste separation then worked harder to support the environment through electricity conservation. The results are important in indicating that deepening our commitment to a mission, in this case by increasing the effort required to further it, can inspire us to advance the mission in related ways.

More far-flung illustrations of the power of effortful commitments exist as well. There is a tribe in southern Africa, the Thonga, that requires each of its boys to go through an elaborate initiation ceremony before he can be counted a man. As in many other tribes, a Thonga boy endures a great deal before he is admitted to adult membership in the group. Anthropologists John W. M. Whiting, Richard Kluckhohn, and Albert Anthony described this three-month ordeal in brief but vivid terms:

When a boy is somewhere between 10 and 16 years of age, he is sent by his parents to “circumcision school,” which is held every 4 or 5 years. Here in company with his age-mates he undergoes severe hazing by the adult males of the society. The initiation begins when each boy runs the gauntlet between two rows of men who beat him with clubs. At the end of this experience he is stripped of his clothes and his hair is cut. He is next met by a man covered with lion manes and is seated upon a stone facing this “lion man.” Someone then strikes him from behind and when he turns his head to see who has struck him, his foreskin is seized and in two movements cut off by the “lion man.” Afterward he is secluded for three months in the “yard of mysteries,” where he can be seen only by the initiated.

During the course of his initiation, the boy undergoes six major trials: beatings, exposure to cold, thirst, eating of unsavory foods, punishment, and the threat of death. On the slightest pretext, he may be beaten by one of the newly initiated men, who is assigned to the task by the older men of the tribe. He sleeps without covering and suffers bitterly from the winter cold. He is forbidden to drink a drop of water during the whole three months. Meals are often made nauseating by the half-digested grass from the stomach of an antelope, which is poured over his food. If he is caught breaking any important rule governing the ceremony, he is severely punished. For example, in one of these punishments, sticks are placed between the fingers of the offender, then a strong man closes his hand around that of the novice, practically crushing his fingers. He is frightened into submission by being told that in former times boys who had tried to escape or who had revealed the secrets to women or to the uninitiated were hanged and their bodies burned to ashes. (p. 360)

On their face, these rites seem extraordinary and bizarre. Yet they are remarkably similar in principle and even in detail to the common initiation ceremonies of school fraternities. During the traditional “Hell Week” held yearly on college campuses, fraternity pledges must persevere through a variety of activities designed by older members to test the limits of physical exertion, psychological strain, and social embarrassment. At week’s end, the boys who have persisted through the ordeal are accepted for full group membership. Mostly, their tribulations have left them no more than greatly tired and a bit shaky, although sometimes the negative effects are much more serious.

It is interesting how closely the features of Hell Week tasks match those of tribal initiation rites. Recall that anthropologists identified six major trials to be endured by a Thonga initiate during his stay in the “yard of mysteries.” A scan of newspaper reports shows that each trial also has its place in the hazing rituals of Greek-letter societies:

- Beatings. Fourteen-year-old Michael Kalogris spent three weeks in a Long Island hospital recovering from internal injuries suffered during a Hell Night initiation ceremony of his high school fraternity, Omega Gamma Delta. He had been administered the “atomic bomb” by his prospective brothers, who told him to hold his hands over his head and keep them there while they gathered around to slam fists into his stomach and back simultaneously and repeatedly.

- Exposure to cold. On a winter night, Frederick Bronner, a California community-college student, was taken three thousand feet up and ten miles into the hills of a national forest by his prospective fraternity brothers. Left to find his way home wearing only a thin sweatshirt and slacks, Fat Freddy, as he was called, shivered in a frigid wind until he tumbled down a steep ravine, fracturing bones and injuring his head. Prevented by his injuries from going on, he huddled there against the cold until he died of exposure.

- Thirst. Two Ohio State University freshmen found themselves in the “dungeon” of their prospective fraternity house after breaking the rule requiring all pledges to crawl into the dining area prior to Hell Week meals. Once locked in the house’s storage room, they were given only salty foods to eat for nearly two days. Nothing was provided for drinking purposes except a pair of plastic cups in which they could catch their own urine.

- Eating of unsavory foods. At Kappa Sigma house on the campus of the University of Southern California, the eyes of eleven pledges bulged when they saw the sickening task before them. Eleven quarter-pound slabs of raw liver lay on a tray. Thick-cut and soaked in oil, each was to be swallowed whole, one to a boy. Gagging and choking repeatedly, young Richard Swanson failed three times to down his piece. Determined to succeed, he finally got the oil-soaked meat into his throat, where it lodged and, despite all efforts to remove it, killed him.