Sexual propagation comes down to the seed. Shake a few seeds into the palm of your hand and behold the essence of creation. This dazzling feat of packaging compresses all the genetic information necessary to reproduce an entire plant, plus opportunities for travel and, often, some sustenance for the journey.

A seed is one of nature’s most ingenious gifts. The spirited cosmos starts from seed, as does the giant redwood.

The acquisition of a startling new plant for the garden is one of the most compelling reasons to sow seeds. Producing a great number of plants is another. Scores of seeds can be sown, frequently at low cost (and sometimes for free).

Seeds can be shipped around the world with minimal packaging and handling. (Begonia seeds come about a million to the ounce.)

The next phase of the seed sower’s career might be to discover and select a distinctive variety from a mass sowing. There is also the potential to “invent” a new plant by interbreeding two plants or a succession of plants, although such manipulation may be controversial. Agribusinesspeople, native-plant enthusiasts, plant purists, and explorers have strong opinions on the subject. A good case is made by the seed savers, who promote the old-fashioned heirloom varieties. The gardener’s plea for “new” varieties should be balanced by efforts to perpetuate the old varieties of vegetables and flowers. The possible loss of an entire crop grown in a monoculture, for instance, might be staved off by promoting horticultural and agricultural diversity.

Nature doesn’t necessarily need new plants, either, just safe places for indigenous ones to grow. Conservation is another reason to propagate plants from seeds. Stealing plants from the wild is just plain wrong; the theft may contribute to a mini-ecosystem’s demise. The best way to stop people from digging plants in the wild is to make those plants available from nursery-propagated stock; the home gardener can obtain seeds of a wildflower from a native-plant society and grow them to help a species persist, even if its homeland does not survive.

There is one more incentive for sowing seed: it is so much fun. There is the challenge of the hunt for seeds of the species or variety, the thrill of watching them sprout, and the satisfaction of nurturing the seedlings. Ultimately, the joy of propagation is seeing the results in first flowers, or basking in the shade of a tree that will live on beyond the length of our own lives.

A strain of deep mahogany sunflowers was encouraged by collecting and sowing seeds from the darkest blossoms of the season.

For the highest volume at the lowest cost, bedding plants are grown commercially from seeds.

The last wild Franklinia alatamaha was seen in 1790, but it exists today because seeds were grown by John Bartram, who named this shrub for his friend Benjamin Franklin.

Hybridizing for desired characteristics is another reason to sow.

It is said that good luck is simply taking advantage of opportunity. Cultivars, varieties of plants that can be cultivated and introduced to the nursery trade, are found in intentional mass sowings all the time. More frequently, however, they are simply discovered by someone who spends a moment taking a second look. Careful scrutiny of flats of seedlings on the benches at the nursery in spring, or of seedlings sown at home, often reveals something special. The more seeds sown, the greater the chances of discovering a unique plant.

Hostas are among the most popular herbaceous perennials, with new introductions appearing each year and vying for the top spot on the annual list of favorites chosen by the American Hosta Society. A hosta with the brightest golden leaves, sweetly perfumed flowers, or a shapely leaf with a wave or a wiggle can command hefty prices: $200 or more. Gardeners can search for their own. Instead of deadheading all your hostas after flowers fade, let one stalk form plump fruits. When the fruits are still green but the stalk turns brown, cut the stem and bring it to a safe place indoors. It could be stood in an empty vase set in a box where the warm air can dry the pods so any seeds that drop when the pods split open will be collected. Hosta seed can be sown fresh and will come up quickly (see chapter 5, “Sowing”).

The signs of something different will show quickly. Seedlings with promise can be potted up to be grown on in the garden, and the rest can be discarded. Thankfully, the seedlings that don’t measure up do not have to go to the compost heap. There’s a gardener born every minute, so the surplus should easily find homes.

The popularity of hostas demonstrates the growing interest in plants for foliage. Coleus, for instance, have never been grown for flowers. These plants —formerly familiar in dish gardens made to brighten the sickroom —offer an incredible range of leaf colors, and that has led to the plants’ dramatic comeback. Today’s coleus barely resemble their forebears. They have even gotten an up-market name change, to Solenostemon scutellarioides. The current crop includes individuals with striking leaf shapes, intricate color patterns, or vivid solid shades in every hue but blue. The vegetatively propagated cultivars have also been given evocative monikers such as ‘Inky Fingers’, ‘India Frills’, ‘Purple Duckfoot’, ‘Ella Cinders’, and ‘Evil’.

John Beirne, a young horticulturist and self-described “foliage freak,” discovered a distinctive variety in a batch of mixed seedlings. A gardener at Wave Hill, the public garden in the Bronx, New York, where John worked one summer during college, named the incredible coppery-pumpkin discovery ‘Beirned Orange’.

A sampling of autumn oak leaves represents some of the fifty varieties grown by Nigel and Lisa Wright in Pennsylvania. The oaks begin as acorns received through the mail from commercial seed suppliers, botanical gardens, and fellow members of the International Oak Society.

Unusual varieties can be selected from mass sowings of “open pollinated” seeds as John Beirne found with pumpkin-colored coleus—dubbed ‘Beirned Orange’ by a fellow gardener.

Sean Conway plucked a distinctive coleus seedling from his nursery row—shown with its namesake, son Emmett. Cuttings have to be taken each year to have new plants of coleus ‘Emmett’ and ‘Beirned Orange’.

Betty Sturley made a dense sowing of fresh hosta seeds in a flat, hoping to find something wonderful. Distinctive traits, such as variegation, appeared early.

A plant name with the designation “X,” such as Abelia X grandiflora, denotes that it is more than a selection among the progeny of a species.

The plant is the product of either an accidental mingling of independent species or an intentional one. The “X” notes that this plant is a “cross,” or hybrid. While a hybrid is commonly thought to be made from two different but closely related species, it is actually the result of interbreeding any two distinct individuals, either within one species (an intraspecific hybrid), between two species of one genus (an interspecific hybrid), or, in the rarest cases, between genera (an intergeneric hybrid). In the latter case, the plant’s name usually begins with the symbol X —as in X Mahoberberis (a hybrid of the genera Mahonia times Berberis).

With all this crossing going on, seedlings often exhibit characteristics that might make them attractive additions to the ornamental garden. Blossoms with extra rows of petals (double flowers) may appear, as they do in roses. A seedling may be stockier than its brethren, what we call compact. Plant breeders frequently predict the results by choosing parents for particular characteristics.

The process begins when the pollen from one plant is brought to the female stigma of another. The fertilized flower is then sheathed in gauze or a paper covering to ensure that the cross will not be contaminated by undesired pollen. From generation to generation, selections are made and interbred. The final cross produces a seed that will result in a plant with predictable attributes.

The familiar seed packets of “F1” hybrid annuals indicate a first-generation crossing of two inbred lines. These “improved” versions have hybrid vigor (as opposed to inbred depression). However, if a gardener likes the hybrid and wants to grow it again, more seeds will have to be purchased, if possible. A newer introduction may already have taken its place. Although overblown double-petaled marigolds might seem better than the comely single types to some gardeners, others find something missing in these manufactured, and sterile, products (figuratively, and sometimes literally).

A maroon Helleborus orientalis flower chosen to be “father” was cut and floated in water in the refrigerator for a few days to keep its pollen fresh for “mother” (this page).

A hybrid is the product of any cross-pollination, but when many gardeners hear the word, they picture something like this mix of annual impatiens. The latest offerings from commercial houses are usually “F1” hybrids, or first-generation seeds produced in highly controlled conditions. A debate rages on as to whether there is a need for ever more “new and improved” plants. There’s a worry, too, that flashy introductions might supplant species, replace favorite heirloom varieties, or threaten to dominate agriculture. However, producing your own hybrid should be guilt-free when the subject is not invasive and just for your own garden.

While the thought of big-business breeding seems unnerving, keep in mind that hybrids occur in nature all the time. It may be prudent to remain wary of some manipulative agriculture —especially in the production of food crops —but on the small scale of the home garden, the interest in creating a “new” plant can be benign —just for fun. Consider the daylily.

One wonders whether with 50,000 named varieties of Hemerocallis, there is any point to making another one. But daylilies are popular candidates for amateur hybridizers because the male and female floral organs are large and accessible. The seeds that form are easy to handle, and in just three years (fast for hardy perennials), the characteristics of the new creations will be revealed in the first flowers. And every now and again an introduction appears with honestly original traits.

All of the Hemerocallis in our gardens today originated from only a handful of species. Crosses between the resulting hybrids and species or hybrids and hybrids led to the proliferation. For instance, a cross between the lavender-flowered Hemerocallis cultivar ‘Prairie Blue Eyes’ and the fragrant old favorite cultivar ‘Hyperion’ yielded a variety of offspring. A few plants had spidery, lavender-pink petals. Another bore blooms that stayed open late into the evening, and its mauve-pink and yellow flowers faded to tan and taupe. The nameless hybrid offspring may not have “improved” upon their father by having bluer flower color, but they all were fragrant and unique.

To create your own daylily hybrid, select parents with characteristics you think would produce something special. For example, choose a plant with very fragrant flowers to match with one that blossoms in an unusual color; or, perhaps, join a plant with low foliage with another that produces a funnel-form bloom on slender, tall scapes.

Visit the chosen mother-to-be early in the morning, when the dew still glistens on the leaves and the flowers are just opening. The anthers will be evident but will not have split open to reveal their pollen. Self-pollination is unlikely, but for safety’s sake, snip the anthers off with scissors. In half an hour or so, the anthers on the father plant will ripen and they should be used at once. A small artist’s paintbrush is an efficient tool for collecting the pollen. Just as the brush picks up pigment and then deposits it on the canvas, so too will it collect and release pollen. The drawback with a brush, however, is that unless you are pollinating several flowers by one male, you will need to scrupulously clean the brush between procedures. Alternatively, you can pinch a bit of pollen between your fingertips or simply pluck the entire anther to bring to the stigma of the mother-to-be.

Daylily blossoms last only a single day, and the pollen begins to “grow” at once. It is unlikely that unwanted pollen from another flower will ruin the cross, since the race is over as soon as the first batch is delivered and pollination has begun. So coverings of gauze or paper will not be necessary. Tie a tag labeled with names of the father and mother and the date of the cross. The petals will soon fall and the ovary containing the developing seeds will swell. A paper bag should be lowered over the fruits and tied shut. (For information on harvesting, see this page.)

Most Hemerocallis species have yellow or orange flowers, but a pink variety, H. ‘Rosea’—discovered in Kiangsi Province, China, and imported to the New York Botanical Garden in 1939—presented the opportunity to breed hybrids in shades from pink to red; for example, H. ‘Prairie Blue-eyes’.

In a recent cross for fragrance, shape, and color, this broad-flowered lavender hybrid contributed pollen to the sweetly scented yellow introduction from 1925, H. ‘Hyperion’.

The half-dozen progeny included a rose-pink flower with spidery petals, one with mauve petals and contrasting ivory midribs, and one with broad recurved petals, thin sepals that curl at the ends, a dark “eye,” and a yellow throat that deepens to lime green at the center. None of the flowers were as “blue” as their father or as fragrant as their mother, but the one shown stays open late into the evening, when the sparkling colors turn tan.

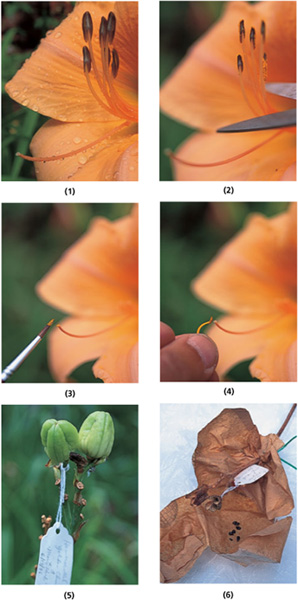

There are 50,000 named varieties of daylily, and no wonder: the sexual components are accessible and results can be seen in as little as two years—quick for a long-lived perennial. The process includes these steps: When the mother-to-be opens early in the morning but its anthers have not yet split to reveal the pollen (1), snip off the stamens (2). Shortly thereafter, pollen is collected from the father, and if several crosses are to be made with contributions from this single parent, a clean artist’s paintbrush may be used to gather and deliver the golden grains (3). Or simply pick one ripe anther and touch it to the stigma (4). Label the cross with the parents’ names and the date of the merger (5). Very soon, fruits will appear. Cover the swollen fruits with a paper bag before they begin to shrivel and turn brown, so when the capsule splits open, the seeds can be retrieved (6).

Where are the hollyhocks that grew in the farmhouse yard? Who can recall the redolent fragrance of violets or remember pears you could eat with a spoon? These were plants once grown in quantity, but for whatever reason —perhaps because they fell out of favor, or there were difficulties in large-scale production and shipping —are uncommon today.

Advocates of “heirloom” varieties generally oppose modern genetic fusion. The fear is that old-fashioned “strains” will be ignored and ultimately lost in the ongoing quest for “new and improved” ones. If you harvest and sow seeds from a modern F1 hybrid flower, the result will revert to something that resembles one or both original parents —not the hybrid you began with. On the other hand, when a propagator perpetuates individual plants with desirable characteristics by cultivating them in relative isolation and collecting their seeds to sow again each year, a strain may emerge. Although a plant from a strain is not a species, it will “come true” from saved seed.

Producers of heirloom seeds often work on a somewhat small scale. They enclose their crops with frames covered with screening on the top and sides to keep insects from introducing the genes from other varieties in the species. If gardeners continue to segregate these strains, usually annuals or biennials, they will retain their traits. For example, seeds harvested from the antique ‘Brandywine’ tomato will grow to produce that fruit again.

Although it is too late for the lost varieties, other plants are making a comeback because of the growing number of “seed savers,” gardeners dedicated to preserving heirlooms as essential resources. More than nostalgia is driving this movement. Heirlooms, grown from seeds that have been handed down through generations or rescued and resurrected from an abandoned plot of ground, help maintain diversity within our natural world.

Unlike F1 hybrids—first-generation products of a specific cross—a strain such as hollyhock ‘Chater’s Double Apricot’ is a variant that “comes true” from seed as long as it is segregated from similar plants.

This method is used to perpetuate heirloom tomato varieties.

Forms, subspecies, or strains of plants may develop when individuals in a species interbreed. On a hillside in Quebec, Frank Cabot promotes the white-to-blue lupines that naturalize throughout his apple orchard.