‘Training is patient safety for the next 30 years’1

‘Training is patient safety for the next 30 years’1The Foundation Programme

Applying to the Foundation Programme

The FP curriculum and assessment

Starting as an F1

Communication

Quality and ethics

When things go wrong

Boring but important stuff

Your career

Specialty training applications

‘Training is patient safety for the next 30 years’1

‘Training is patient safety for the next 30 years’1

The UK Foundation Programme (FP) was established in 2005 as part of a series of reforms to UK medical training, known collectively as Modernising Medical Careers (MMC). The intention was to provide uniform, 2-year structured training for all newly qualified doctors working in the UK, to build upon medical school education and form the basis for subsequent training. Sadly, much of the introduction of MMC was a shambles. In relative terms the FP fared well, although the early days were not without problems and in 2010 it was still criticized for lacking a clearly articulated purpose.2 Two reports gave a number of recommendations that were taken forward through a series of workstreams that were reviewed in 2015.3 Though the FP continues to evolve, this review did find progress in a number of important domains, including trainee empowerment, assessment outcomes, and the variety of rotations available to trainees. Nationally, a new curriculum was introduced in 2016 (for review in 2021); however, locally the changes necessary to deliver better training are still filtering through. This process is an iterative one that trainees are encouraged to get involved in. Significant changes have been afoot since the 2013 ‘Shape of Training report’ (see Box 1.18,  p. 45).

p. 45).

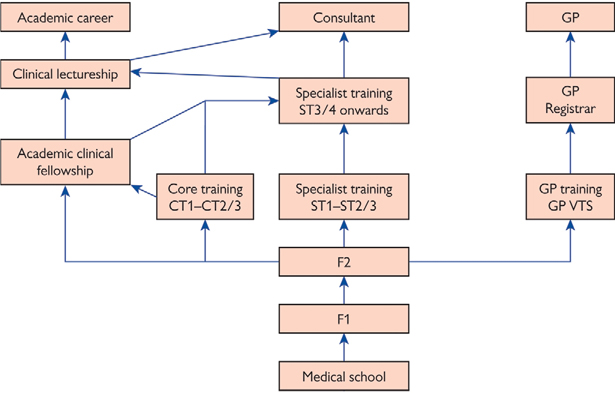

The FP lasts 2 years, and in >90% of programmes, each year involves rotating through 3 different 4-month placements, which may be in hospital or community-based medicine. About a quarter of programmes involve a placement in a ‘shortage specialty’ (where the number of current trainees is likely to fall short of future consultant needs), and despite a shift towards the management of chronic disease in the community, much of the FP emphasis remains on the acute care of adult patients in a hospital setting. At the start of the FP, you will be required to hold ‘provisional registration’ with the General Medical Council (GMC) (Table 1.1;  p. 3). Strictly, the first FP year (F1) represents the final year of basic medical education and your medical school remains responsible for signing you off; this responsibility may be delegated for those doctors completing F1 in a different region from their medical school. After successfully completing F1, you will be issued with a Certificate of Experience, which entitles you to apply for full GMC registration and start F2. Successful completion of F2 results in the awarding of a foundation achievement of competence document (FACD) which opens the door to higher specialty, core, or GP training (

p. 3). Strictly, the first FP year (F1) represents the final year of basic medical education and your medical school remains responsible for signing you off; this responsibility may be delegated for those doctors completing F1 in a different region from their medical school. After successfully completing F1, you will be issued with a Certificate of Experience, which entitles you to apply for full GMC registration and start F2. Successful completion of F2 results in the awarding of a foundation achievement of competence document (FACD) which opens the door to higher specialty, core, or GP training ( p. 45).

p. 45).

All administrative aspects of the FP are overseen by the UK Foundation Programme Office (UKFPO) which provides many important documents at  www.foundationprogramme.nhs.uk, including the application handbooks, reference guide (the ‘rules’), curriculum (list of educational objectives), and advice for overseas applicants.

www.foundationprogramme.nhs.uk, including the application handbooks, reference guide (the ‘rules’), curriculum (list of educational objectives), and advice for overseas applicants.

Table 1.1 The FP hierarchy

| The GMC | Overall responsibility for setting the standards for medical practice and training in the UK |

| The UKFPO | Manages applications to and delivery of the FP |

| Local Education Training Boards (LETBs) | Part of the Department of Health’s ‘Health Education England’. Deliver the FP regionally and support financial costs of training and trainee salaries ( p. 38) p. 38) |

| Foundation schools | Deliver the FP locally. May overlap with the LETB |

| Director of postgraduate education | Responsible for overseeing all medical training in a hospital ( p. 39) p. 39) |

| Foundation training programme director (FTPD) | Responsible for the management and quality control of the FP in a hospital. Oversees the panel that reviews your annual progress. Responsible for signing off on successful completion of each foundation year |

| Acute Trust/Local Education Provider | Acute trusts provide the employment contract, salary, and HR for foundation doctors. For community placements (eg GP practice), the responsibility for education passes to this ‘Local Education Provider’ but the contract of employment remains with the acute trust. There can be conflicts between the needs of the acute trusts (doctors on the wards delivering services to patients) and some of the educational requirements of the FP ( p. 59) p. 59) |

| Educational supervisor | Doctor responsible for the training of individual foundation doctors. Ideally for a whole year but occasionally for a single attachment. Will review your progress regularly, check that your assessments are up to date, and help you plan your career |

| Clinical supervisors | Doctors who supervise your learning and training, day to day, for each attachment. In some posts (often your 1st) the roles of the educational supervisor and clinical supervisor may be merged |

| Academic supervisor | Those undertaking an academic FP (which includes a designated period of research) will be assigned an individual to oversee academic work and provide feedback |

| Local administrator | Individuals in each trust and Foundation school who help with FP registration and administration |

| FP representative | Leadership position(s) where willing trainees voluntarily facilitate two-way feedback between their peers and their local or regional educationalists |

| The Foundation Doctor | This is you! You are an adult learner with responsibilities for your own learning. You are expected to integrate with the educational processes of the FP, including providing feedback on the programme to your supervisors, trainee representatives, and via local and national training surveys |

All applications to the FP are through the online FP Application System (FPAS) at  www.foundationprogramme.nhs.uk. There are several stages.

www.foundationprogramme.nhs.uk. There are several stages.

Registration for FPAS You will need to be nominated. For final year students in the UK your medical school will do this for you. Those applying from outside the UK should contact the UKFPO Eligibility Office in good time to allow checks to take place.4 Before nomination you can register for an account but cannot access the application form.

Completing the application form Within a designated window each year (usually in early October), nominated applicants will be able to access the application form. This has a number of parts:

Personal Name, contact details, DoB, and relevant personal health.

Eligibility GMC status, right to work in the UK, and immigration status.

Fitness Criminal convictions and fitness to practise proceedings.

Referees Details of 2 referees (1 academic, 1 clinical). Their knowledge of your performance is more important than their seniority because they contribute to your pre-employment checks (re suitability for work) rather than your actual programme allocation.

Competences Educational qualifications ± postgraduate experience.

Evidence You will be asked to list any additional degrees for scoring against a very specific system and to upload a copy of certificates; 5 total percentage points are available for your degree, with 2 further points for publications (proof is required and will be assessed).

Clinical skills You will be asked to self-assess against a list of practical skills—this does not form part of the assessment process but will be used by Foundation schools to coordinate training.

Academic selection If applying to the academic FP ( p. 6).

p. 6).

UoA preferences Foundation schools are grouped into Units of Application (UoA) that process applications jointly. You will be asked to rank all UoA in order of preference, with successful applicants allocated to UoA in score order (you will be allocated to your highest preference UoA that still has places when your turn comes). Tables showing vacancies and competition ratios for previous years are available on the UKFPO website but these do tend to vary between years (see Box 1.1).

Equal opportunities To monitor NHS recruitment practices.

Declaration You are required to sign various declarations of probity.

Linked applications Two applicants can join their applications ( pp. 6–7).

pp. 6–7).

Scoring Your application will be scored based upon 2 components:

Educational Performance Measure (50 points) This comprises a score between 34 and 43 based upon which decile your medical school decides your performance falls in, relative to your peers (this is locally determined) with 7 further points for education achievements detailed on the application form as previously mentioned.

Situational Judgement Test (50 points) See Boxes 1.2 and 1.3.

Box 1.1 Units of Application and 2017 competition data

The 21 UoA shown are the Foundation Schools for the 2017 application. Note, in April 2017 NC and NE Thames merged into the North Central and East London Foundation School. Vacancy numbers for 2017 are shown, with figures in brackets representing the number of applicants ranking the UoA as their first preference, expressed as a percentage of this number of jobs. Source: data from  www.foundationprogramme.nhs.uk

www.foundationprogramme.nhs.uk

Box 1.2 Situational Judgement Test (SJT)

Box 1.2 Situational Judgement Test (SJT)

These computer-marked tests of 70 questions sat under examination conditions over 2h 20min confront you with situations in which you might be placed as an F1 doctor, and ask how you would respond. There are two basic response formats: (i) rank five possible responses in order and (ii) choose three from eight possible responses. Marks are assigned according to how close to an ‘ideal’ answer you come, with marks for near misses and no negative marking. Raw scores are subject to statistical normalization and scaling to generate a final mark out of 50. Officially, you cannot ‘revise’ for the test, as it is an assessment of attitudes, but there is a strong weighting on medical ethics which can be revised, and you can familiarize yourself with what is expected and try to understand model answers.5 When introduced into FP selection for 2013 appointments, problems with SJT marking led to hundreds of altered offers. Ongoing controversy surrounds SJTs as a means of selection, the thin evidence base behind them, and the heavy weighting they receive. One prominent researcher and SJT advocate closely involved in the pilots is also a director of a company that provides SJTs, as well as being a key figure behind the selection process that so spectacularly failed during the 2007 MMC reforms. Nonetheless, it is difficult to argue that previous systems based upon answering generic questions or students competing to get references from a few blessed Professors were any better. Our advice for now: ‘Get studying!’

Box 1.3 The Prescribing Safety Assessment (PSA)

Box 1.3 The Prescribing Safety Assessment (PSA)

Prescribing is a fundamental part of the FP and it is now a requirement for UK FP applicants to demonstrate their knowledge of the safe and effective use of medicines through completion of this national pass/fail prescribing skills assessment. Piloted in 2010 in response to a GMC-sponsored survey which showed that 9% of hospital prescriptions contain errors, applicants are tested on common prescriptions, medications, drug calculations, and monitoring regimens that are encountered during the FP. Exams take place at UK medical schools between February and June each year, and non-UK trainees can sit it during F1.6

For those interested in research, teaching, or management, the Academic FP offers 7450 programmes with time set aside for academic work (either a rotation or time spread across the year) ( p. 12, p. 66).7 Aside from extra sections on academic suitability, the application form is the same, ranking up to 2 ‘Academic’ UoAs (which differ slightly from standard UoAs) and some Academic FPs within them. Shortlisted candidates are interviewed and offers made in advance of the main FP selection process, so that unsuccessful applicants can still compete for a regular FP position.7

p. 12, p. 66).7 Aside from extra sections on academic suitability, the application form is the same, ranking up to 2 ‘Academic’ UoAs (which differ slightly from standard UoAs) and some Academic FPs within them. Shortlisted candidates are interviewed and offers made in advance of the main FP selection process, so that unsuccessful applicants can still compete for a regular FP position.7

Your total score will be used to determine your place in the queue for matching to a FP, and you will be offered a place in your highest preference UoA which still has FP vacancies when your turn comes. Results will be communicated by email and you will have a limited window to accept this. Allocation to an individual programme is done based on your total application score and your ranking of individual programmes. Some UoAs (eg those with more programmes) have a two-stage match process where you rank groups of trusts before ranking the programmes within the group to which you have been allocated. However, most UoAs use a one-stage process where you simply rank all of the individual programmes from the outset. Further information is available on each UoA website.

A typical F1 year usually consists of three placements of 4mth: one in a general medical specialty, one in a general surgical specialty; options for the third specialty vary widely in just about all areas of medicine. F2 posts also typically consist of three 4mth jobs; for 80% of F2s one of these will be a GP placement. Allocation to F2 posts varies between UoAs, with some assigning all F1 and F2 posts at the outset, while others may invite you to select F2 posts during your F1 year. Once you are appointed to the FP, you are guaranteed an F2 post in the same Foundation school, but often in a different acute trust. If you do not get an F2 post in a specialty you are particularly interested in, most will allow individual FP doctors to swap rotations, providing they have the support of their educational supervisors. Some Foundation schools will organize ‘swap shops’ to facilitate this process, but swapping can be notoriously difficult. You can also arrange ‘taster weeks’ in another specialty to help plan your career; to arrange these talk to your educational supervisor, clinical supervisor, and a consultant in the relevant specialty.

During the FPAS application process, it is possible for any two individuals to link their applications. In this case, you must both supply each other’s email addresses in the relevant section of the application form, and rank all UoAs in identical order. The score of the lower scoring applicant will then be used to allocate both applicants to the same UoA. Although policies vary between UoAs, linking does not necessarily guarantee appointment to the same trust or town—check individual UoA websites for their policies. Note also that if one of you accepts a place on an Academic FP or is put on the reserve list, the link is broken.

In recent years, the supply of applicants has threatened to exceed places on the FP. Those whose FPAS scores place them below the cut-off to be guaranteed a FP post will be placed on a reserve list and are often able to gain a training post when an unexpected event befalls another candidate. If you are not successful in securing a post first time round do not give up hope! If you feel you have been unfairly marked you may be able to appeal; discuss this with your medical school dean. Try to seek feedback from the application process in order to identify weaknesses that you may be able to amend in case you have to wait to reapply the next year. Should you still be without a post after you know you have qualified from medical school, contact LETBs and hospitals directly; some of your peers may not be able to take up their posts due to exam failure so you may be able to apply directly to these standalone posts.

Another option is to consider taking a year out, either to strengthen your application by doing research, further study, or other activities that add to your skills. Also consider applying overseas; it has been possible in previous years to do some or all of foundation training in Australia or New Zealand with prior approval of posts from a UK LETB. Alternatively, it is possible to apply to any post within the EU or to consider equivalency exams for other countries.

Finally, there is always the option of a career outside of medicine. Advice on this and other options will be available from your university careers office, from websites such as Prospects ( www.prospects.ac.uk) or certain courses/conferences (eg

www.prospects.ac.uk) or certain courses/conferences (eg  www.medicalsuccess.net).

www.medicalsuccess.net).

For those who meet the very specific criteria, it may be possible to be pre-allocated to a specific Foundation school, regardless of your FPAS score. These cases include if:

• You are a parent or legal guardian of a child <18yr, for whom you have significant caring responsibilities

• You are a primary carer for a close relative

• You have a medical condition or disability for which ongoing follow-up in the specified location is an absolute requirement.

If any of these apply to you, discuss with your medical school dean or tutor well in advance of the application process opening.

Those wishing to train less than full-time should apply through the FPAS alongside other candidates; upon successful appointment, they should contact their new Foundation school to discuss training opportunities and plans. Programmes have good arrangements for LTFT, whereby trainees are paid on a ‘pro rata’ basis for all work done, as a proportion of the full-time salary.

The FP Curriculum acts as a guide for what you will be expected to achieve over the 2 years of the FP, how you will get there, and how you will be assessed. There are 20 Foundation training outcomes (Box 1.4) that are grouped according to the GMC’s ‘Good Medical Practice’. To complete the FP you must keep a record of your experiences, reflections, and study (the NHS ePortfolio) to demonstrate that for each of the outcomes you have acquired the minimum level of competence required.

Box 1.4 Foundation Professional Capabilities

Source: data from  www.foundationprogramme.nhs.uk

www.foundationprogramme.nhs.uk

NHS ePortfolio The ePortfolio is an electronic record of your progress through the FP. The syllabus lies at its centre, to which you can link evidence of achievement of competence using a number of tools. Alongside this lies your supervisor and end-of-year reports. The ePortfolio may also be used for specialty training interviews to show competence and achievement and as a library for a wide range of support material (see Boxes 1.4, 1.5, and 1.19,  p. 8, p. 10, p. 57). It is vital that you engage with your ePortfolio early on and keep it updated, as it is the primary measure by which you are assessed. While the effort required is not small, the time and energy your supervisors need to review your ePortfolio should also not be underestimated. You are both helped by keeping your electronic and paper portfolios organized, current, and complete (Box 1.19,

p. 8, p. 10, p. 57). It is vital that you engage with your ePortfolio early on and keep it updated, as it is the primary measure by which you are assessed. While the effort required is not small, the time and energy your supervisors need to review your ePortfolio should also not be underestimated. You are both helped by keeping your electronic and paper portfolios organized, current, and complete (Box 1.19,  p. 57).

p. 57).

Assessment Assessment is based on observation in clinical practice, your ePortfolio evidence supporting curriculum competence (see Table 1.2), evidence of engagement in learning, and proficiency in the GMC’s core procedures. Direct observation comes from your supervisors but also other work colleagues in the form of a Team Assessment of Behaviour and feedback from your Placement Supervision Group. Formative assessments are ways of seeking feedback whereas summative assessments are to demonstrate competence—both are equally important. The burden of what many see as a tick-box exercise is still significant, though improving slowly with each FP curriculum revision. Assessment culminates in the Annual Review of Competence Progression (ARCP), which determines your eligibility to move on to training.

Meetings There are a number of meetings you need to record in your ePortfolio. These are detailed in Box 1.6.

Table 1.2 Supervised learning events (SLEs) and assessments

|

|

||

|

Direct observation of doctor/patient encounter: Mini-clinical evaluation exercise (mini-CEX) Direct observation of procedural skills (DOPS) |

≥9 per year—including ≥6 mini-CEX (≥2 per attachment)* | |

| For mini-CEX, you will be observed speaking to and/or examining a patient and receive feedback on your performance. For DOPS, you will be observed performing a clinical skill and receive feedback on your interaction with the patient. | ||

| Case-based discussion (CbD) | ≥6 per year (≥2 per attachment) | |

| You will present and discuss a case (or an aspect of a complex case) you have been closely involved in and discuss the clinical reasoning and rationale. | ||

| Developing the clinical teacher | ≥1 per year | |

| This requires you to deliver an observed teaching session—you will receive feedback based on your preparation, teaching, knowledge and audience interaction. | ||

|

|

||

| Core procedure assessment forms | 1 per procedure during F1 | |

| By the end of F1 you need to be signed off as competent in 15 core procedures: | ||

| Team assessment of behaviour (TAB) | 1 per year | |

| You will be required to engage in a Maoist process of self-criticism, then select a minimum of 10 colleagues who will be invited to provide anonymous feedback, including at least 2 consultants/GPs, 1 other doctor >FY2, 2 senior nurses >band 5, and 2 allied health professionals/other team members (eg ward clerks, secretaries, and auxiliary staff). Similar feedback comes from your Placement Supervision Group but they are nominated by your supervisor rather than by you. Your educational supervisor will then collate all the results and share them with you. | ||

*There is no minimum number of DOPS required per year.

Box 1.5 Keeping the ePortfolio

Box 1.5 Keeping the ePortfolio

As well as recording your structured learning events, you can upload a wide range of other documents to your ePortfolio to serve as evidence of your progress. Some suggestions include:

• Copies of discharge/referral letters (anonymized)8

• Copies of clerkings (anonymized)8

• Attendance at clinic (date, consultant, learning points)

• Procedures (list of type, when, observing, performing, or teaching)

• Details of any complaints made against you and their resolution

• Incident forms you have been involved in (useful for reflective practice and demonstrating that you have learned from mistakes)

• Copies of presentations given

• Details of teaching you’ve done (with feedback if possible)

Box 1.6 Meetings during the FP

Box 1.6 Meetings during the FP

There are a number of required meetings which you should record in your ePortfolio. The onus is on you to schedule and prepare for these meetings: you and your supervisors are all busy clinicians, and it can sometimes be difficult to arrange these in a timely manner. Be flexible but persistent!

Induction At the start of each placement you should meet with both your educational and clinical supervisors9 to agree learning objectives and review what opportunities are available during the placement.

Midpoint Meetings in the middle of each placement with your supervisors to review progress are encouraged, particularly where you or they have concerns, but are not compulsory. You may also decide to have a mid-year review with your educational supervisor.

End of placement Both your supervisors should meet with you separately to review your achievements, pass on the observations of the team, provide advice, and listen to your feedback.

End of year You should meet your educational supervisor to discuss your total progress. Your supervisor will complete a report for the panel performing your annual review to inform their decision to sign you off.

The NHS is the world’s 5th largest employer and while impossible to appreciate fully, a general understanding helps contextualize your role. Since its inception in 1948, the NHS has aimed to provide quality care that is free at the point of use and based on clinical need alone. It is an important part of our UK identity and by global standards, per capita, is good value for money.

Government Since 1999, devolved governments in Wales, Scotland, and N Ireland have had control over their NHS and healthcare budgets. Funding comes almost entirely from taxation, totalling £120bn/yr in England. Department of Health Government department led by the Health Secretary responsible for healthcare policy and overseeing the NHS in England. Health and Social Care Act A 2012 parliament act and the largest NHS reorganization since 1948, legislated for more healthcare regulation and patient involvement, and decentralization of healthcare/budget responsibility. Allowed business to compete with NHS providers for service provision. Commissioners With two-thirds of the total NHS budget, GPs, nurses, hospital doctors, and lay members now lead >200 clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) in buying (commissioning) local services (including secondary care, mental health, and community services). GPs themselves as well as highly specialized services are still commissioned nationally. Providers Commissioners purchase services from providers, which can be GPs, the private sector, voluntary sector, or hospitals. Most trusts are ‘Foundation’ Trusts, that is, have more financial and managerial freedom (the intention being to provide more flexibility to better suit local patient needs).

Arm’s-length bodies Non-departmental public bodies that are associated with but have some independence from the Department of Health. Health Education England Ensures the workforce has the skills to support healthcare and drive improvements. Coordinates training locally through 4 LETBs and 13 deans, including the 20 Foundation schools ( p. 3). Healthcare regulators The Care Quality Commission (for care quality) and NHS Improvement (for finances) are responsible for monitoring, inspecting, and reporting on providers to ensure they provide quality care within the resources available. Both have powers to advise and intervene if necessary. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) By balancing the potential gains in quality and quantity of life against financial costs, NICE provide guidance to patients and providers on the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of new treatments and technologies over previous ones.

p. 3). Healthcare regulators The Care Quality Commission (for care quality) and NHS Improvement (for finances) are responsible for monitoring, inspecting, and reporting on providers to ensure they provide quality care within the resources available. Both have powers to advise and intervene if necessary. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) By balancing the potential gains in quality and quantity of life against financial costs, NICE provide guidance to patients and providers on the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of new treatments and technologies over previous ones.

Outside agencies ( p. 3, p. 12)

p. 3, p. 12)

Trade unions Represent doctors and if supported by members can call for industrial action over employment disputes. Campaign for better conditions and comment on health issues. British Medical Association The largest doctors’ trade union, for GPs and hospital doctors alike. Hospital Consultants and Specialists Association Focuses on the needs of hospital doctors. General Medical Council An independent regulator responsible for maintaining the official register of UK medical practitioners, controlling entry onto the register, and removing members where necessary. The GMC sets the standards that doctors and medical schools should follow. Medical Royal Colleges Independent professional bodies that develop and provide training in the various medical specialties. 21 are members of the Academy of Royal Colleges which promotes and coordinates their work. Faculty of Medical Management and Leadership A faculty of the Academy of Royal Colleges that is dedicated to medical leadership. A good resource for trainees interested in medical leadership and management.

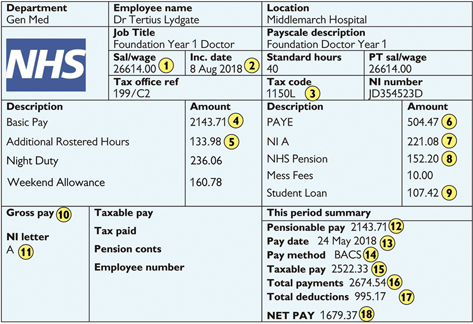

The prices quoted change frequently; they are intended as a guide.

General Medical Council (GMC) To work as a doctor in the UK you need GMC registration with a licence to practise; £50 for F1 (provisional registration), £150 for F2 (full registration), and £390 thereafter.

NHS indemnity insurance This covers the financial consequences of mistakes you make at work, providing you abide by guidelines and protocols. It automatically covers all doctors in the NHS free of charge.

Indemnity insurance This is essential; do not work without it. These organizations will support and advise you in any complaints or legal matters that arise from your work. They also insure you against work outside. There are three main organizations; all offer 24h helplines ( pp. 614–615):

pp. 614–615):

• Medical Protection Society (MPS)—£10 for F1, £20 for F2

• Medical Defence Union (MDU)—£10 for F1, £20 for F2

• Medical and Dental Defence Union of Scotland—£10 for F1, £35 for F2.

British Medical Association (BMA) Membership benefits include employment advice, a contract checking service, a postal library, and a weekly subscription to the BMJ. Annual costs are £115 for F1s and £226 for F2s.

Hospital Consultants and Specialists Association Alternative trade union for those planning a career in hospital medicine. Benefits include employment advice, contract checking, personal injury service, and legal services. Annual cost is £100 for foundation trainees.

Income protection Pays a proportion of your basic salary ± a lump sum (rates vary) until retirement age if you are unable to work for health reasons. Check if it covers mental health problems, and if it still pays if you are capable of doing a less demanding job. NHS sickness benefits are not comprehensive (providing F1s 1mth full pay, 2mth half pay, and F2s 2mth full pay, 2mth half pay): Available from various providers, typically starting at £24/mth as an F1, rising according to age, pay, illness, and risks.

2015 NHS Pension Scheme A proportion of your pay is put into the scheme to be returned, with additional interest and employer contributions, during your retirement. Despite bringing the retirement age in line with the state pension, an increase in the cost of personal contributions, and a shift from final salary to career-averaged earnings, the 2015 NHS Pension Scheme remains the best pension available; do not opt out.

P45/P60 tax form When you leave a job you will receive a P45; if you continue in the same job you will receive a P60 every April. These need to be shown when starting a new job.

Bank details Account number, sort code, and proof of address.

Hepatitis B You need proof of hep B immunity and vaccinations. You should keep validated records of your immunizations and test results.

GMC registration certificate This proves you are a registered doctor.

Disclosure and Barring service (DBS) certificate (formerly CRB checks) It is the employer’s responsibility to perform these checks. You must complete all paperwork in good time, but payment is the responsibility of the trust.10

Preparation for professional practice This mandatory week of paid induction is usually online and face-to-face but there is a difference between what you want to know before starting and what trusts are obliged to tell you. The best people to talk to are your predecessors, but a little background reading about your first rotation specialty also helps. To reduce the cost of face-to-face induction there is a trend towards eLearning, but the BMA is clear: induction is work and if done outside of work should be reciprocated financially or with time off in lieu.

Pay roll It can take over a month to adjust pay arrangements so it is vital to give the finance dept your bank details on or before the first day if you want to be paid that month. Hand in a copy of your P45/P60 too.

Parking Check with other staff about the best places to park and ‘parking deals’; you will probably need to get several people to sign a form.

Cycling Trusts usually provide safe storage for bikes and sometimes you can save money on repairs/new purchases with ‘cycle to work’ schemes.

ID badge Used to access secure parts of the hospitals. If you need more access than most (e.g. crash team members) then request ‘access all areas’. If the card doesn’t give access then return it or get it fixed.

IT Computer access allows you to access results, the Internet, and your trust email. Also ask for an NHS.net account so you can access it securely from home and keep the same email when moving between trusts. Memorize all the passwords, usernames, etc and keep any documents handed out. Ask for the IT helpdesk phone number in case of difficulty.

Rota coordinator You should get to know your medical staffing department well as they can make your life a lot easier. If you haven’t received your rota in advance then get in touch with them.

Mobiles and social media Induction may be the last time for a while you are all in one place. Exchanging numbers makes social activities, rota swaps, and learning opportunities easier to organize, but there will usually be rolling, trust-wide WhatsApp groups you can join. If not, create one/ask your FP representative to coordinate efforts (Box 1.7).

Try to get a map; many hospitals have evolved rather than been designed. There are often shortcuts.

Wards Write down any access codes and find out where you can put your bag. Ask to be shown where things are kept including the crash trolley and blood-taking equipment.

Canteen Establish where the best food options are at various times of day. Note the opening hours—this will be invaluable for breaks on-call.

Cash and food dispensers Hospitals are required to provide hot food 24h a day. This may be from a machine.

Doctors’ mess Essential. Write down the access code and establish if there is a fridge or freezer. Microwave meals are infinitely preferable to the food from machines. For problems, contact the mess president.

Most hospitals have an occupational health department that is responsible for ensuring that the hospital is a safe environment for you and your patients. This includes making sure that doctors work in a safe manner. You can find your local unit at  www.nhshealthatwork.co.uk

www.nhshealthatwork.co.uk

During the FP, your contact with occupational health is likely to be one of the following:

Initial check Depending on the procedures you will be undertaking, you may require a blood test to show you do not have hepatitis C or HIV; they will need to see photographic proof of identity, eg a passport.

Hepatitis B booster This depends on local policies and your antibody levels.

Needle-stick/sharps injury/splashes ( p. 108).

p. 108).

Illness Illness that affects your ability to work may require a consultation.

Patients are commonly infected by pathogens from the hospital and ward staff. The infections are more likely to be resistant to antibiotics and can be fatal. It is important to reduce the risk you pose to your patients:

• If you are ill, stay at home, especially if you have gastroenteritis

• Keep your clothes clean and roll up long sleeves to be bare below the elbows in clinical areas

• White coats, ties, and long sleeves are generally discouraged

• Avoid jewellery (plain metal rings are acceptable) and wrist watches

• Clean your stethoscope with a chlorhexidine swab after each use

• Wash your hands or use alcohol gel after every patient contact, even when wearing gloves; rinsing all the soap off reduces irritation. Clostridium difficile spores are resistant to alcohol, so always wash your hands after dealing with affected patients

• Be rigorous in your use of aseptic technique

• Use antibiotics appropriately and follow local prescribing policies. For more information, contact your local infection control team.

As a doctor you will come into contact with bodily fluids daily. It is important to develop good habits so that you are safe on the wards:

• Wear gloves for all procedures that involve bodily fluids or sharps. Gloves reduce disease transmission if penetrated with a needle—consider wearing two pairs for treating high-risk patients

• Dispose of all sharps immediately; take the sharps bin to where you are using the sharps and always dispose of your own sharps

• Vacutainers are safer than a needle and syringe. Most hospitals now stock safety cannulas and needles for phlebotomy, use of which decreases the risk of needle-stick injuries yet further

• Mark bodily fluid samples from HIV and hepatitis B+C patients as ‘High Risk’ and arrange a porter to take them safely to the lab

• Consider wearing goggles if bodily fluids might spray

Black pens These are the most essential piece of equipment. Carry a few as people often lose theirs. Blood bottles are usually labelled with printed stickers but specimen bottles may still need a ballpoint pen.

Stethoscope A Littmann® Classic II or equivalent is perfectly adequate, however better models do offer clearer sound.

Money and cards Out-of-hours loose change is useful for food dispensers but most places will take cards.

ID badge Should be supplied on day 1 and may come with a printer fob.

Bleep Often at switchboard, in handover, with colleagues or on the ward.

Mobile phone A plethora of medical apps can make your life much easier; however, signal can be variable so don’t forget your bleep. Always check who has written your apps and whether it is a reliable source. Most Oxford Handbooks, including this one, are now available as an app. Although previous rules restricting their use have largely been eased, it does not look good to be always on your phone, and it remains the case that they can interfere with monitoring equipment in ICUs, CCUs, and surgical theatres.

Clipboard folder  p. 18.

p. 18.

Pen-torch Useful for looking in mouths and eyes; very small LED torches are available in ‘outdoors’ shops or over the Internet and can fit onto a keyring or be attached to stethoscopes to prevent colleagues borrowing and not returning them.

Tendon hammer These are hard to find on wards. Collapsible pocket-sized versions can be bought for £12–15.

Alcohol gel Clip-on alcohol gels are cheap, will mean you never have to go searching, and can be more ‘predictable’ than those on the ward.

Patients and staff have more respect for well-dressed doctors, however it is important to be yourself; be guided by comments from patients or staff.

Hair and piercings Long hair should be tied back. Facial metal can be easily removed while at work; while ears are OK, other piercings draw comments.

Shoes A pair of smart, comfy shoes is essential—you will be on your feet for hours and may need to move fast.

Scrubs Ideal for on-calls, especially in surgery. Generally they should not be worn for everyday work. Check local policy.

Box 1.7 Social media

Box 1.7 Social media

The GMC, BMA, and individual trusts publish guidance for doctors regarding their use of social media. While Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp have many benefits for us as professionals and individuals, all blur the line between public, private, and professional life and none guarantee confidentiality. In using them we must remember our duty of confidentiality, to treat colleagues fairly, and to maintain trust in the profession. Any posts should consider the impact on patients, yourselves, and the profession, avoiding derogatory or offensive comments. Misuse can lead to action by trusts or the GMC.

Being an F1 involves teamwork, organization, and communication—qualities that are not easily assessed during finals. As well as settling into a new work environment, you have to integrate with your colleagues and the rest of the hospital team. You are not expected to know everything at the start of your post; you should always ask someone more senior if you are in doubt.

As an F1, your role varies greatly (ask your predecessor) but includes:

• Clerking patients (ED, pre-op clinic, on-call, or on the ward)

• Updating patient lists and knowing where patients are ( p. 18)

p. 18)

• Participating in ward rounds to review patient management

• Requesting investigations and chasing their results

• Liaising with other specialties/healthcare professionals

• Practical procedures, eg taking blood ( pp. 528–529), cannulation (

pp. 528–529), cannulation ( pp. 532–533)

pp. 532–533)

• Administrative tasks, eg theatre lists ( p. 114), TTOs (

p. 114), TTOs ( pp. 80–81), rewriting drug charts (

pp. 80–81), rewriting drug charts ( pp. 171–172), death certificates (

pp. 171–172), death certificates ( pp. 98–99)

pp. 98–99)

• Speaking to the patient and relatives about progress/results.

Discharge letters are your responsibility and without them patients cannot leave the hospital. Not only are well patients very keen to be at home, unwell patients needing admission also need to leave the Emergency Department and come into their bed. This process is called patient flow and is vital in the day-to-day running of the hospital and making sure patients are being cared for in the right environment. While there are many factors that slow down patient flow, patients, clinicians, and management staff will thank you if high-quality discharge letters are prepped well in advance. Keeps tabs on estimated discharge dates and if you’re not sure, enquire with your colleagues about who may be going home tomorrow.

Missing breaks does not make you appear hard-working—it reduces your efficiency and alertness. Give yourself time to rest and eat (chocolates from the ward do not count); you are entitled to 30min for every 4h worked. Use the time to meet other doctors in the mess; referring is much easier if you know the team you are making the referral to.

If you are unsure of something, don’t be embarrassed to ask a senior, particularly if a patient is unwell. If you are stuck on simple tasks (e.g. cannulation), take a break and either try later or ask a colleague to try.

F1s may have to make difficult decisions, some of which may have potentially serious consequences. Always consider the worst-case scenario and how to avoid it. Be able to justify your actions and document everything carefully.

For all patients under your care, seniors will reasonably expect you to know the current problem list, medication, and the details of any recent procedures or investigations, including key recent blood results. Initially this may well seem impossible, but with time and careful practice, your memory for such details will improve.

What at first seems like a badge of having ‘made it’ quickly becomes the bane of your existence. When the bleep goes off repeatedly, write down the numbers then answer them in turn. Try to deal with queries over the phone; if not, make a list of jobs and prioritize them, tell the nurses how long you will be, and be realistic. Ask nurses to get useful material ready for when you arrive (eg an ECG, urine dipstick, the obs chart, notes, equipment you may need). Encourage ward staff to make a list of routine jobs instead of bleeping you repeatedly. The bleep should only be for sick patients and urgent tasks. Learn the number of switchboard since this is likely to be an outside caller waiting on the line. Crash calls are usually announced to all bleep holders via switchboard. If your bleep is unusually quiet, check the batteries. Consider handing over your bleep to a colleague when breaking bad news, speaking to relatives, or performing a practical procedure.

Dropping the bleep in the toilet This is not uncommon; recover the bleep using non-sterile gloves. Wash thoroughly in running water (the damage has already been done) and inform switchboard that you dropped it into your drink.

Other forms of bleep destruction You should not have to pay for a damaged bleep, no matter how dire the threats from switchboard; consider asking for a clip-on safety strap.

You need to be proactive to learn interpretation and management skills as an F1. This is especially true when most of the decisions you make will be reviewed by a senior almost immediately. Despite this, ‘Bloods, CXR, senior r/v’ is not an adequate plan and represents a failure to engage with a learning opportunity. Formulate an impression, differential diagnosis, and management plan for each patient you see and compare this with your senior’s version; ask about the reasons for significant differences. See Box 1.8.

Box 1.8 Service provision vs training?

Box 1.8 Service provision vs training?

Acute trusts need doctors to see patients so that they can be treated, discharged, and the trust reimbursed. Behind this simple fact lies an important point of tension between the aims of the trust and those of the individual doctor who will want to develop and acquire new skills. As a foundation doctor, you are in an educationally approved post, for which the LETB releases funds to the trust. It is therefore important that you should be given the opportunities to train and develop, and that you should be released from routine ward work to attend all dedicated training sessions. At the same time, the discharge summaries need to be typed, the drug charts rewritten, and a seemingly endless number of venflons resited. The challenge for all involved is to achieve educationally useful outcomes within these constraints. This situation is not unique to the FP—all doctors within the NHS have to balance these demands and some of those tasks you aspire to be able to perform will be the same tasks that have become routine and even frustrating for your seniors. There are no magic answers, but a preparedness to work hard, a keenness to seize educational opportunities whenever they present, and a supportive educational supervisor will all go a long way.

Your organizational abilities may be valued above your clinical acumen. While this is not why you became a doctor, being organized will make you more efficient, ensure you go home on time, and free up time to make the most of learning opportunities as and when they arise.

Your ward All departments have different ways of working and these will usually have evolved this way over time for good reason. Equally, some things may have become out of date and may need updating. If you have an idea, discuss it with your predecessors and seniors and consider taking the lead on an audit or quality improvement project.

Folders and clipboards These are an excellent way to hold patient lists, job lists, handbooks, and spare paperwork along with a portable writing surface. Imaginative improvements can be constructed with bulldog clips, plastic wallets, and dividers.

Contents Spare paper, drug charts, DNAR forms, phone numbers, job lists, patient lists, theatre lists, spare pens, and ward access codes.

Patient lists Juniors are often entrusted with keeping a record of the team’s patients (including those on different wards, called ‘outliers’) along with their background details, investigation results, and management plans. With practice, most people become good at recalling this information, but writing it down reduces errors. They are usually electronic and may be manually or automatically generated, allowing every team member to carry a copy. Lists can be invaluable for discussing/referring a patient while away from the ward but must be kept confidential and disposed of securely ( p. 83).

p. 83).

Job lists During the ward round make a note of all the jobs that need doing either on your list or on a separate piece of paper. At the end of the round, these jobs can be distributed among your other team members.

Serial results Instead of simply writing blood results in the notes, try writing them on serial results sheets (with a column for each day’s results). This makes patterns easier to spot and saves time.

Timetables Along with ward rounds and clinical jobs there will be many extra meetings, teaching sessions, and clinics to attend. There are three blank timetables at the end of this book to use for this purpose.

Important numbers It can take ages to get through to switchboard so carrying a list of common numbers will save you hours (eventually you will remember them). At the end of this book there are three blank phone number lists for you to fill in. Blank stickers on the back of ID badges can hold several numbers.

Ward cover equipment Finding equipment on unfamiliar wards wastes time and is frustrating. You can speed up your visits by keeping a supply of equipment in a box. Try to fill them with equipment from storerooms instead of clinical areas. Alternatively, if you are bleeped by a nurse to put in a cannula, you could try asking them nicely to prepare the equipment ready for you for when you arrive (it works occasionally).

Despite the years spent at medical school preparing for finals and becoming a doctor, being efficient is one of the most important skills you can learn in the FP and one that you will value throughout your career.

Working hours While you are contracted to work a fixed number of hours you will usually work more, especially towards the beginning of your career. To make your day run as smoothly as possible consider arriving early, before your seniors, to prepare for the day (e.g. review unwell patients, overnight events, nursing concerns, patient lists, and latest test results).

Time management You will nearly always seem pressed for time, so it is important to organize your day efficiently. Prioritize tasks in such a way that things such as blood tests can be in progress while you chase other jobs. Requesting radiology investigations early in the day is important as lists get filled quickly, whereas writing blood forms for the next day and prescribing warfarin can wait till later on. Prepare discharge summaries and TTOs well in advance to avoid being the rate-limiting step in getting patients home.

On-call It will seem like your bleep never stops going off, especially when you are at your busiest. Always write down every job, otherwise you run the risk of forgetting what you were asked to do. Consider whether there is anyone else you could delegate simple tasks to, such as nurse practitioners or ward staff while you attend to more urgent tasks.

• Make a list of common bleeps/extensions ( p. 622)

p. 622)

• Establish a timetable of your firm’s activities ( p. 623)

p. 623)

• Make a folder/clipboard ( p. 18)

p. 18)

• Prioritize your workload rather than working through jobs in order. Try to group jobs into areas of the hospital. If you’re unsure of the urgency of a job or why you are requesting an investigation, ask your seniors

• If you are working with another foundation trainee, split the jobs at the end of the ward round so that you share the workload

• Run through the patient list throughout the day to review progress

• Submit phlebotomy requests at the start/end of each day (find out what time the phlebotomists come); if a patient will need bloods for the next 3 days then fill them all out together with clear dates

• Be aware of your limitations, eg consent should only be taken by the doctor performing the procedure or one trained in taking consent for that particular procedure

• Bookmark online or get a copy of your hospital guidelines/protocols, eg pre-op investigations, anticoagulation, DKA, pneumonia etc.

• Get a map of the hospital if you haven’t got your bearings

• Remember the names and faces of your colleagues and patients

• Talk to your predecessors to get hints and tips specific to your ward.

The traditional medical model made the patient a passive recipient of care. Healthcare was done to people rather than with them. Many patients were happy with this.

Our task as clinicians is to find out our patients’ expectations of their relationship with their doctors and then try to fulfil these. From ‘whatever you feel is best doc’ to reams of printouts and self-diagnoses from the Internet, neither extreme is wrong and our task is to help.

Find out whether your patient wants guidance regarding what treatment may be best.

Respect their right to make a decision you believe may be wrong. If you feel that they are doing so because they do not fully understand the situation or because of flawed logic, then alert your team to this so that things can be explained again.

Find out their other influences, these can be very powerful. Examples include: religious beliefs, friends, the Internet, and death/illness of relatives with similar conditions.

Patients may have clear expectations of their treatment (eg an operation or being given a prescription). These expectations are important sources of discontentment when not fulfilled. Find out what their expectations are and why. Useful questions may include: ‘What do you think is wrong with you?’ ‘What are you worried about?’ ‘What were you expecting we’d do about this?’

Make time to imagine yourself in your patient’s shoes. Isolation or communication difficulties will heighten fear at an already frightening time. Long waits without explanation are sadly common. Aggression from friends or relatives is often simply a manifestation of anxiety that not enough is being done. Ask yourself ‘How would I want my family treated under these circumstances?’ then do this for every patient.

Hospitals can rob people of their dignity. Wherever and whenever possible help restore this:

• Keep your patients covered (including during resuscitation)

• Ensure the curtains are around the bed on the ward round

• Make sure they have their false teeth in to talk and glasses/wigs on whenever possible

Patients are often clerked over four times for a single admission. This is frustrating for them and often seen as indicative of a lack of coordination within the hospital. Patients may need to be clerked and examined more than once, but the context of this should be explained carefully—is this to gain more insight about their condition or to allow a training doctor to learn? People rarely mind when they understand the reasons. Keep examinations which are invasive or cause discomfort to an absolute minimum.

Good communication with patients and colleagues is a vital part of the job.

Whenever you are communicating with another health professional (see Box 1.9), include your name and role, the patient’s name, location, and primary problem, what you would like them to do and how urgently, and how they can contact you if there are any problems

Box 1.9 Handover

Box 1.9 Handover

Reductions in working hours, a move towards shift-based rotas, and the increased cross-cover between specialties mean the number of doctors caring for a patient during their stay has increased, making the effective transfer of information more important. Handover occurs at the start and end of every shift, and it is vital that it is given enough time and thought. Some are formal handover meetings chaired by a senior while others are more informal. Either way, the incoming doctor must get a clear idea of the situation including the names, locations, and clinical details for unwell patients and those needing review, as well other outstanding tasks that need going. Giving and receiving a good handover is a key skill and one you should pride yourself on perfecting.

Clinical notes p. 76.

Clinical notes p. 76.

Referral letters p. 84.

Referral letters p. 84.

Sick notes p. 82.

Sick notes p. 82.

Self-discharge If your patient wants to discharge themselves, speak to them, ask why, manage their concerns, and explain why they need hospital management and what may happen if they leave. If they have capacity, then ask them to sign a ‘self-discharge form’ and do a TTO as normal.

As a doctor you are a respected member of society and a representative of the medical profession, and people will expect you to act in a certain way. While this does not mean you cannot be yourself, there is a big change from medical school and you must be aware of expectations:

• Always introduce yourself, especially over the telephone or when answering a bleep; ‘Hello’ is not enough

• Wear your ID badge at all times in hospital

• Never be rude to colleagues/ward staff; you will get a bad reputation

• Never be rude to patients, no matter how they treat you

• Never: shout, swear, scream, hit things, or wear socks with sandals

• Do not gossip about your work colleagues; address any problems you have with a colleague directly and in private

• When you do something wrong, apologize and learn from your mistake; it’s a natural part of the learning curve

• If you are going to be late, let the person know in advance especially for handover or ward rounds

• If you think it is not appropriate for you to do a job then run it by the ward staff or your seniors. Ask for help if you feel overrun with tasks.

Communication with relatives can be difficult if done badly, or rewarding if done well. They may be scared, assuming the worst and be in the frustrating position of not knowing what is going on. They could have a full-time job that prevents them coming in during the day:

• If you are on-call and do not know the patient well then be honest about this, but attempt to answer simple questions as best possible using the notes; explain what times the usual ward staff will be present

• Try to arrange a time when you can discuss the patient’s progress in a quiet room (ask a colleague to hold your bleep)

• To avoid repeating yourself, speak to the family collectively or ask them to appoint a representative

• Check the patient is happy to have their confidential medical details discussed ( p. 29) and encourage them to be present if possible

p. 29) and encourage them to be present if possible

• Address concerns and answer each question in turn

• Be honest about your limitations and involve seniors where necessary

• Document the date, time, what was discussed, and who was present.

A patient’s perception of your abilities as a doctor depends largely on your communication skills. Remember that patients are in an alien environment, often feel powerless, and are worried about their health.

Introductions Always introduce yourself to patients and clearly state your name and position. Ask your patient how they wish to be addressed (eg Denis or Mr Smith). Patients meet many staff members daily so reintroduce yourself each time you see them (see Box 1.10).

General advice Try to avoid using medical jargon. Be honest with your replies to them, and give direct answers when asked a direct question. If you do not know the answer, be honest about this too.

Results Explain why a test was done, what it shows, and what it means.

Diagnosis Try to give the everyday name rather than a medical one (heart attack instead of MI). Explain why this has happened. A patient who understands their condition is more likely to comply with treatment.

Prognosis Along with the obvious questions about life expectancy ( p. 86), patients are most interested in how their life will be affected. Pitch your explanation in terms of activities of daily living (ADLs), walking, driving (

p. 86), patients are most interested in how their life will be affected. Pitch your explanation in terms of activities of daily living (ADLs), walking, driving ( p. 619), and working. Bear in mind that patients may want to know about having sex, but are often too embarrassed to ask.

p. 619), and working. Bear in mind that patients may want to know about having sex, but are often too embarrassed to ask.

Box 1.10 Hello my name is…

Box 1.10 Hello my name is…

Kate Granger was a geriatrician, patient, and campaigner for compassionate and personalized care who sadly died at the age of 34 in 2016. She was diagnosed with terminal cancer in 2011 and spent her subsequent years campaigning for better communication between doctors and patients. Frustrated at the lack of introductions from healthcare staff caring for her in hospital, she started the #hellomynameis campaign in 2013. Founded on the simple idea of reminding staff that a confident introduction is often all that is needed to put patients at ease, the campaign raised £250,000 for cancer charities and has received widespread public and professional support. It is a reminder to us all never to forget something as simple as introducing ourselves properly.

Ideally, breaking bad news should always be done by a senior at a predetermined time when relatives and friends ± specialist nurses can be present. In reality, you are likely to be involved in breaking bad news, often while on-call. It can be a positive experience if done well.

Preparation Read the patient’s notes carefully and ensure that all results are up to date and for the right patient. Be clear in your mind about the sequence of events and the meaning of the results. Consider the further management and likely prognosis—discuss with a senior.

Consent and confidentiality ( p. 31, p. 29) A patient has a right to know what is going on or to choose not to know. Ask before the investigations are done and document their response. If a patient does not want their relatives to know about their diagnosis you must respect this. Always ask, do not assume—many families have complex dynamics.

p. 31, p. 29) A patient has a right to know what is going on or to choose not to know. Ask before the investigations are done and document their response. If a patient does not want their relatives to know about their diagnosis you must respect this. Always ask, do not assume—many families have complex dynamics.

Warning shot Give a suggestion that bad news is imminent so it is not completely out of the blue, eg ‘I have the results from … would you like anyone else here when I tell you them/shall we go to a quiet room?’.

How to do it The SPIKES model is often used:

Setting Ask a colleague to hold your bleep, set aside suitable time (at least 30min), silence your mobile phone, use a quiet room, and invite a nurse who has been involved in the patient’s care. Arrange the seats so you can make eye contact and remove distractions. Introduce yourself and find out who everyone is.

Perception Find out what the patient already knows by asking them directly; this will give you an idea of how much of a shock this will be and their level of understanding to help you give appropriate information.

Invitation Explain that you have results to give them and ask if they are ready to hear them. It helps to give a very brief summary of events so they understand what results you are talking about.

Knowledge Break the bad news, eg ‘A doctor has looked at the sample and I’m sorry to say it shows a cancer’. Give the information time to sink in and all present to react (shock, anger, tears, denial). Once the patient is ready, give further information about what this means and the expected management. Give the information in small segments and check understanding repeatedly. Prognosis can be difficult; never give an exact time (‘months’ rather than ‘4 months’). Be honest and realistic. Try to offer hope even if it is just symptom improvement or leaving hospital.

Empathy Acknowledge the feelings caused by the news; offer sympathy. This will take place alongside the ‘Knowledge’ step. Listen to their concerns, fears, and worries. This will guide what further information you give and help you to understand their reactions.

Summary Repeat the main points of the discussion and arrange a time for further questions, ideally with a senior and yourself present. Give a clear plan of what will happen over the next 48h. Document the discussion in the patient’s notes (diagnosis, prognosis, expectations) with your name and contact details.

For patients who can’t understand or speak the same language as you, the consultation can leave them feeling isolated, frustrated, and anxious. You may have to rely on a third party to translate for you (see Box 1.11).

Professional interpreters can be arranged before the appointment—ask ward staff or phone switchboard.

• Allow extra time for the consultation and check the interpreter is acceptable to the patient

• Address both the patient and the interpreter and look at the patient’s non-verbal response to gauge their level of understanding

• Ask simple, direct questions in short sentences to avoid overloading or confusing the interpreter; avoid jargon

• Use pictures or diagrams to explain things wherever possible; provide written/audiovisual material in the patient’s own language to take away

• If you cannot organize an interpreter, you may be able to contact a telephone interpreting service who can translate for you and the patient directly over the phone (ask nurses or switchboard)

• Document that a trained interpreter has been used with their name and contact details so that the same interpreter can accompany the patient for future appointments.

Never assume you know what the patient wants without asking them.

There are many reasons why family members and friends should not be used as interpreters. Nevertheless, in emergency situations, this may prove necessary. Address the patient directly and look carefully at the patient’s response to gauge their understanding. Record the fact that a family member was used for interpretation in the notes.

Friends and relatives They are commonly used as informal interpreters. The main drawbacks are the lack of confidentiality and the bias the relative may have on the patient’s decision-making—particularly when underlying family issues are present (you may be unaware of these).

Children They can interpret for their parents from an early age, but again their views can bias the consultation and its outcome (eg sexual health and vulnerable adults) and even routine clinical questions can be very frightening or inappropriate for children. Use only as a point of last resort.

Conflict of interests If you think the relative is biasing the conversation or it is an important issue, then explain that you are professionally obliged to request a trained interpreter.

Consent Relatives cannot consent on behalf of adults ( p. 31).

p. 31).

Box 1.11 Who can interpret?

Outside agencies who could enquire about your patients include: police, media, solicitors, fire brigade, paramedics, GP, researchers, and the patient’s employer. Patient confidentiality must be respected.

• Do you really know who you are talking to?

• Check and arrange to call them back unless certain

• Do they have any right to the information they are seeking?

•GPs, healthcare professionals, and ambulance staff may well do, police have limited rights (see later in this topic), many others do not

• Should you be the one discussing this or should it be a more senior member of the team?

• Do not talk to the media about a patient/your hospital unless:

• You have the patient’s permission, and

• You have permission from your consultant/management (for trust issues), and

• Do not ‘chat’ to a police/prison officer about a patient, no matter what the alleged circumstances; all patients have an equal right to privacy

• Breaching a patient’s confidentiality without good cause is treated as misconduct by the GMC.

Immediate investigation of assaults The police may well ask the clinical condition of an assault victim. ‘Is it life-threatening, doctor?’ The purpose of this question is to know how thoroughly to investigate the crime scene. It is reasonable to give them an assessment of severity.

In the public interest In situations where someone may be at risk of serious injury, disclosure is permitted by the GMC. This should be a consultant-level decision.

The Road Traffic Act Everyone has a duty to provide the police with information which may lead to the identification of a driver who is alleged to have committed a driving offence. You are obliged to supply the name and address, not clinical details. Discuss with your seniors first.

Inform your clinical supervisor; they should accompany you to court. Remember you are a professional witness to the court so your evidence should be an impartial statement of the facts. Do not get rattled by the barristers—stick to the facts, do not give opinions, explain the limits of your knowledge/experience. Address your remarks to the judge. Dress smartly. Get an expenses form from the witness unit to claim your costs back.

You may be asked to provide patient details for research. Ask the researcher to provide you with ID and if they have consent from the patient. Unless the researcher has specific permission to screen medical notes, they may ask you to seek initial permission from any potential participant before passing on the patient’s details to the researcher.

DH definition: ‘Clinical governance is the system through which NHS are accountable for continuously improving the quality of their services and safeguarding high standards of care, by creating an environment in which clinical excellence will flourish.’

• You are responsible for your clinical practice which you should be aiming to continuously improve

• You need a mechanism for assessing the standard of your practice

• While in training, this is done for you by your consultant/trainer as part of your regular appraisal process. Additionally, you may have audits and regular departmental meetings

• You should be aiming to continuously learn and improve your care for patients. Again, while still in training, this almost goes without saying; revising for endless examinations and diplomas helps too.

• You should ensure you stick to departmental or hospital protocols and don’t undertake procedures for which you have not been trained

• You will be asked to participate in regular departmental audits, usually of morbidity and mortality. These are used to ensure consistency of practice and to pick up problems early

• You should attend departmental and hospital-wide audit meetings and grand rounds to keep up to date with changes

The clinical governance structure in every hospital includes:

• Audit of practice (eg reattendances within 1wk or wound infections)

• Appraisal and revalidation structures

• Regular departmental meetings (eg morbidity and mortality) to allow clinicians to compare their care and highlight common concerns

• Clear routes of accountability for all staff. It can be obvious when these have broken down, leading to problems which everyone can identify but seemingly no one is responsible for fixing

• A risk management structure to identify practices which jeopardize high-quality patient care (critical incident reporting,  p. 34)

p. 34)

• A complaints department to respond to complaints and ensure lessons are learned from them; may be part of the risk management department

• A clinical governance/quality committee structure which oversees and ensures compliance with all of the above.

Compliance with clinical governance/quality mechanisms are measured both regionally and nationally through quality boards.

Ethics are moral values, and in the context of medicine are supported by four main underlying principles:

Autonomy This is the right for the individual to make decisions for themselves, and not be overtly pressurized or swayed by others (namely doctors, nurses, relatives, etc). Patients should be allowed to contribute when decisions are made about their care. If an individual lacks capacity ( p. 30) then it might not be appropriate to let them make important autonomous decisions.

p. 30) then it might not be appropriate to let them make important autonomous decisions.

Beneficence This is concerned with doing what is right for the patient and what is in their best interests. This does not necessarily mean we should do everything to keep a 90-year-old patient alive who has widespread metastatic disease. There will be times when it is beneficent to keep a patient comfortable, and allow them to die naturally.

Non-maleficence This ensures care-givers refrain from doing harm to the patient, whether physical or psychological. An example of a breach in nonmaleficence would be if a patient came to harm as a result of a doctor performing a procedure in which they had inadequate training or supervision.

Justice This requires that all individuals are treated equally and that both the benefits and burdens of care are distributed without bias. Justice also covers openness within medical practice and the acknowledgement that some activities may have certain consequences—specifically legal action.

Two further principles are important to consider:

Dignity This should be retained for both the patient and the people delivering their healthcare.

Honesty This is a fundamental quality which doctors (as well as other care-givers) and patients should be expected to exhibit in order to strengthen the doctor–patient relationship.

Ethical dilemmas frequently arise in clinical practice and are probably not discussed enough. While the principles listed do not necessarily provide an immediate answer, they do create a framework on which the various components of the conflict can be teased out and addressed individually. All doctors should be able to discuss common ethical dilemmas by analysing how each principle is relevant and weighing them up against one another. In ethics there are no right answers, but careful thought and discussion of situations can allow a harmonious solution to be found.

It is quite common that apparently complex ethical issues arise because of a failure in communication between the patient or their loved ones and healthcare professionals. The solution to most of these conflicts is the establishment of effective and transparent lines of communication.

To breach patient confidentiality is unlawful and unprofessional; several doctors are disciplined and even struck off the medical register each year for this. You should be careful when talking about patients in public places, including within the hospital environment, and only disclose patient information to recognized healthcare staff as appropriate. Pieces of paper with patient information on must never leave the hospital and should be shredded if they are no longer required. Do not leave patient lists lying around. Personal electronic databases of patients should be disguised so individual patients cannot be identified. Electronic devices on which patient information is stored outside of the hospital should be encrypted and registered under the Data Protection Act. You avoid giving any information (names or nature of injuries) to the police, press, or other enquirers; ask your seniors for advice when dealing with these ( p. 26).

p. 26).

Publications Medical journals will often insist that any article which involves a patient must be accompanied by written consent from the patient for the publication of the material, irrespective of how difficult it would be to track down and identify that patient.

Presentations and images If you are talking about a patient to a group of healthcare workers in your own hospital you do not need to obtain consent, but doing so is courteous. If you are talking to an audience from outside your hospital it is advisable you seek the patient’s consent unless the patient is fully anonymized. Equally, if you want to keep copies of radiographs or digital images, ensure these are made anonymous and if this isn’t possible obtain the patient’s written consent. Bear in mind that presentations can easily end up online and be accessed by those other than your original audience.11

Relatives Your duty lies with your patient and if a relative asks you a question about the patient, it is essential you obtain verbal consent from the patient to talk to the relative; alternatively offer to talk to the relative in the presence of the patient. Relatives do not have any rights to know medical information. If the patient lacks capacity then seek senior advice before talking to the relatives. Document all conversations in the notes.

Children As described for adults, if the child has capacity to give consent (see ‘Gillick competence’/Fraser guidelines  p. 30), you must seek verbal consent from the patient to tell the relatives (parents) about their health. If the patient refuses, then offer to talk to the patient about their condition in the presence of their relatives. If you sense the situation will be difficult, seek senior advice/support.