How did a phalangite employ his sarissa during the actual fighting of an engagement in the Hellenistic Age? What target areas, or ‘kill shots’, did the phalangite aim at on his opponent? Such questions themselves raise a number of other issues about the nature of phalangite combat. For example, were the major battles fought by Alexander the Great such one-sided affairs as the reported casualty statistics suggest and, if so, what part did the weaponry play in making these engagements so decisive? Were the phalanx versus phalanx encounters of the Age of the Successors little more than two formations of men armed with lengthy pikes simply hammering away at each other, or was phalangite combat something more ‘technical’? The identification of, and the examination of, the ‘kill shot’ of phalangite combat not only takes steps towards answering such questions but also provides a better understanding of the fundamental mechanics of the warfare of the Hellenistic Age. However, before any examination of the ‘kill shot’ of phalangite combat can begin, an understanding of two basic principles – how much of the phalangite was protected, or at least covered, by his panoply (this was especially important when the phalangite was engaged against another pikeman) and how much of an opponent a phalangite could actually see, and therefore target, when wearing his helmet – must be developed. The details of how well the phalangite was protected and how much he could see can then be compared to other sources of evidence to form the basis for the comprehension of the phalangite ‘kill shot’.

Unfortunately, the ancient sources provide no direct information as to how much of the body was protected by the armour of the time. This can only be determined using observations and calculations drawn from physical re-creation. A man 168cm tall and weighing 82kg presents a target area of approximately 6,241sq cm when not wearing any armour but with his lower legs and feet protected by the ‘Iphicratid’ style boots of the Hellenistic Age (Plate 18). This amount of exposed body area is then significantly reduced by the other elements of the phalangite’s panoply and the stance adopted to wield the sarissa.

One of the main sources of protection for vital areas of the body was the helmet. The all-encompassing Corinthian style helmet of the Greek Classical Age, for example, provided a high level of protection – leaving only 181sq cm of the head exposed by the openings for the eyes and the split down the front which facilitated breathing, speech and, to a lesser extent, ventilation.¹ This represents a reduction in the vulnerable surface area of the head by 75 per cent. In the fourth century BC, design advances to the Corinthian helmet, such as the incorporation of openings for the ears, improved hearing but did not reduce the amount of protection given to the rest of the head against attacks coming directly from the front. The elongated cheek flanges of the Corinthian helmet alone, which did not dramatically alter in size or shape from the fifth century BC to the fourth, more than adequately cover the throat and neck from the front while the rest of the head is protected within the rest of the helmet.

Similarly, Hellenistic Era helmets which possessed large sweeping cheek pieces which covered the neck, throat and lower face provided excellent protection to the head of the wearer. The so-called Masked Phrygian style helmet, for example, with its embossed cheek guards/face-plate which covers the lower face, neck and throat, leaves only the 77sq cm around the eyes and nose, and 44sq cm of the lower neck, between the lower edge of the faceplate and the upper edge of the armour, exposed. The more open area around the eyes on a Phrygian or Thracian helmet, which lack the nasal guard of the Corinthian, allows more air to circulate within the helmet, thus improving ventilation, and gave the wearer a natural range of vision (see below).² The openings for the ears common to the Phrygian-style helmet, as per the later types of Corinthian helmet, also improved hearing without significantly compromising the overall level of protection given to the face. This then agrees with the generalisation made by Warry who states that helmets developed to improve ventilation, hearing and vision without a reduction in the amount of protection provided.

Helmets like the Attic or Chalcidian, the cheek pieces of which did not sweep around the front of the face to protect the neck and throat, while increasing the amount of ventilation experienced by the wearer, came at the cost of leaving approximately 209sq cm of the face and neck exposed. This equates to an increase in the amount of area of the head that is unprotected compared to the Corinthian, Phrygian and Thracian styles of helmet. Other than the improved ventilation of the Attic and Chalcidian helmets, there was no improvement to hearing or vision in comparison to the Thracian/Phrygian or the Corinthian styles used in the fourth century BC. Thus it seems that the choice to wear an Attic or Chalcidian-style helmet would have been a conscious decision to offset protection against style and comfort.

For phalangites who may have had a basic pilos style helmet issued to them by the state, such aesthetic considerations were not an issue. While basic in design, easy to make en masse, and certainly less costly than more elaborate styles of helmet, the pilos had the greatest disparity in terms of the amount of ventilation given compared to the protection provided. Unless augmented with the attachment of cheek guards, which then give it very similar protective qualities to the Attic/Chalcidian or even the Thracian and Phrygian-style helmet, the basic conical pilos left the neck, throat and face of the wearer totally exposed. This would have allowed for a great amount of air to circulate around the head, but left many vital areas vulnerable to attack (see following). If the phalangite was just wearing the kausia as some scholars suggest, then the head would have been given no protection at all unless it is assumed that the cloth from which this item of headwear was made was able to resist impacts from weapons like swords, spears, arrows and other missiles. Thus enclosed helmets like the Corinthian, Phrygian and Thracian gave the best protection but at the expense of reduced ventilation, while more open helmets like the Attic, Chalcidian and pilos provided greater ventilation at the expense of protection.

The phalangite was also protected by body armour. The bronze ‘muscled’ cuirass which seems to have been worn by some phalangites, and which covers the body from collar bone to waist, further reduces the exposed surface area of the chest and torso to the 420sq cm region around the lower abdomen and groin and the 1,103sq cm of the arms. The lower parts of the body would have been protected to some extent by the addition of a set of leather or linen pteruges to the panoply, suspended from the lower rim of the cuirass. Similarly, the composite linothorax, with its incorporated sets of pteruges and double-layer protection for the shoulders, would have also provided the wearer with coverage from collarbone to just above the knee – leaving only 1,002sq cm of the arms and 1,020sq cm of the legs exposed between the boots and the pteruges.

When greaves, which the poet Alcaeus states provided protection against missiles, were worn to cover the shins, and in some cases the knees as well, the vulnerable areas of the legs were similarly lessened to the areas exposed above the greave and below the pteruges.³ If the high ‘Iphicratid’ style boots common to phalangites were worn without any greaves, as often seems to have been the case based upon the way they are depicted in Hellenistic art, these would have provided coverage to the lower legs from just below the knee and a certain level of protection for the feet. While possibly able to stop, or at least limit, the amount of damage received from missile impacts, it is unlikely that the leather of the Iphicratid boot would have withstood the impact of a strong spear thrust. However, the fact that these boots seem to have been regularly worn without the additional coverage of a greave suggests that the boots in themselves could provide a certain level of protection against some impacts (or that the lower legs were infrequently targeted areas of the body). Thus a phalangite wearing a panoply incorporating an enclosed type of helmet, such as the Thracian or Phrygian, linothorax-style body armour and Iphicratid boots had only 2,143sq cm of their body unprotected by their armour. This is a reduction in the amount of exposed areas of the body of 4,098sq cm or 66 per cent (Plate 19).

The protection of the phalangite in combat was also augmented by the positioning of his shield in a defensive position across the front of his body. A phalangite bearing a peltē with a diameter of 64cm in an oblique body posture, with the shield supported on the left arm, and wielding a sarissa in both hands at waist level, greatly reduces the amount of exposed flesh further still. Carried in this manner, the shield completely covers the left arm, the lower throat, and adds an additional layer of protection to the chest and abdomen. This removes a further 501sq cm for the left arm, and 44sq cm for the lower throat, from the amount of area that is not protected by some form of defensive armour.

The adoption of an oblique body posture to wield the sarissa also places the right leg to the rear and positions it well back from any strike which would impact with the shield, effectively removing a further 510sq cm from any calculation of exposed area. The use of an oblique posture to wield the sarissa at waist level additionally places the majority of the right arm in a protected position behind the shield and to the rear beside the body, removing the surface profile of the right arm (approximately 501sq cm) from the amount of body area directly exposed to attacks coming from the front. It is only the forward areas of the hands, extending beyond the protective covering of the shield in order to help wield the hefty pike, that are the most vulnerable part of the arms. However, the exposed hands still offer only a small target profile of around 45sq cm in total. Thus a phalangite wearing the full panoply, with the shield supported on the left arm and wielding the sarissa in a low position, has only the 77sq cm of the face, 45sq cm of the hands, and approximately 510sq cm of the left leg exposed. This equates to a total exposed area of only 632sq cm, or just over 10 per cent of the entire body (Plate 20).

How much protection was awarded to the phalangite by the various elements of his panoply was also very much dependent upon the type of opponent he was facing. If the phalangite was facing an opponent armed with a short reach weapon such as a sword, axe or even the spear of the traditional hoplite, then his main piece of defensive armament was the sarissa itself. For example, a traditional hoplite, who had the best range with his primary weapon of any infantry warrior engaged in hand-to-hand combat in the ancient world except for the Hellenistic pikeman, had a total effective range of just over 2m with his spear (the doru).⁴ Yet for the Hellenistic pikeman, even one armed with one of the shorter variants of the sarissa 12 cubits (576cm) in length, the pike projected ahead of him by around 4.8m even when the weapon was merely held in its ready position (See The Reach and Trajectory of Attacks made with the Sarissa from page 167). Thus the easiest way for a phalangite to defend himself against such an opponent was to press the tip of the pike into the shield of the man opposite him and use the length of the weapon to keep the opponent at a distance where he would not be able to bring his own weapons to bear. This is exactly what the Macedonians accomplished at the battle of Pydna in 168BC. Plutarch relates how the Macedonians used their pikes to hold the Romans at a distance where they were not able to engage with their short swords.⁵ Thus when fighting against an enemy armed with a short reach weapon, the phalangite’s primary offensive weapon also became his main defensive asset. With opponents unable to reach him under such conditions, the defensive attributes of the phalangite’s shield, armour and helmet (regardless of whether it was of a more exposed open-face style of not) were somewhat secondary, and only really needed to protect him against enemy missile fire or in the event of the phalanx breaking up.

The reduction of the size of the shield carried by the phalangite, reduced from the 90cm diameter hoplite aspis to the 64cm diameter peltē as part of the reforms of Iphicrates in 374BC, therefore posed no risk to the phalangite if the phalanx was facing opponents with short-reach weapons so long as the formation remained intact and with its serried rows of pikes presented forward. The all encompassing Corinthian-style helmet common to the Classical hoplite which, along with the offset rim of the hoplite’s aspis provided a double layer of protection to the neck, was also not a mandatory requirement for phalangite warfare due to the reduced chance of the phalangite being struck in the throat by an enemy melee weapon. It is because of these two basic facets of phalangite combat that more open-faced styles of helmet, such as the pilos, the Attic/Chalcidian and the Boeotian, were able to be used by phalangites so readily – especially in the early years of the Hellenistic Period when the enemies faced by the armies of Macedon were all armed with weapons that were easily outreached by the lengthy sarissa.

On the other hand, if the phalangite was facing another pikeman – such as occurred during the numerous battles of the wars of the Successors, the face and head was placed in considerably more danger. In such confrontations, a phalangite wielding a pike which extended ahead of him by 4.8m or more would easily find himself facing an opponent bearing their own sarissa with the exact same combat range – if not a greater range if the opponent carried a longer pike. It is in such instances that one would assume that protection to the head and lower face would have been paramount to the phalangite as the opponents he now faced were armed with weapons which could easily reach him. Interestingly, contrary to this initial assumption, helmets which provided a high level of protection to the face and neck, such as the masked Phrygian common to the age of Alexander, seem to have been less commonly used in comparison to more open styles such as the variants of the pilos. This in turn suggests that the regions of the neck and face were not regularly targeted areas in phalangite combat, particularly in the pike versus pike encounters of the Age of the Successors, otherwise a level of protection for these areas would have been retained. This in itself suggests that the main targeted areas on a phalangite, particularly in the later Hellenistic Period, were parts of the body other than the head.

When bearing a panoply of equipment which included a shield, body armour and helmet, how much of an opponent could a phalangite actually see when engaged in combat? Did this in any way affect what part of an opponent a phalangite would aim his pike at? Most helmets available to the Hellenistic phalangite were relatively open-faced (such as the pilos, Attic or Chalcidian) or had rather large apertures for the eyes (the Thracian, Phrygian and Corinthian of the fourth century BC). Julius Africanus states that, when wearing the basic pilos, ‘the face is uncovered and an unencumbered neck allows for an unhinded view of everything’.⁶ Africanus similarly states that ‘the vision of the combatants [within the pike-phalanx] was unobstructed through the use of the Laconian pilos in the Macedonian army’.⁷ However, how much the Hellenistic man-at-arms could see when wearing an openfaced helmet, and how this in turn dictated his actions on the battlefield, has not yet been examined (until now).

To examine the range of vision available to a phalangite a simple test was conducted. A test participant, wearing a replica masked Phrygian style helmet, faced a horizontal scale attached to an erected screen while extending a 12 cubit (576cm) sarissa forward from the ‘ready position’ with the pike held at waist level. This placed the participant at a ‘pike thrust’ length of just over five metres from the screen. The gaze of the test participant was directed beyond the tip of the sarissa; to where an opponent would be located during an engagement. While the participant maintained this line of sight, markers were moved in from both the left and right until they could be seen at the margins of the participant’s range of vision, as provided by the Phrygian helmet, without the participant averting their eyes from the point directly ahead. The angle from the markers to the centre of the face was then measured and combined to determine the overall range of vision.

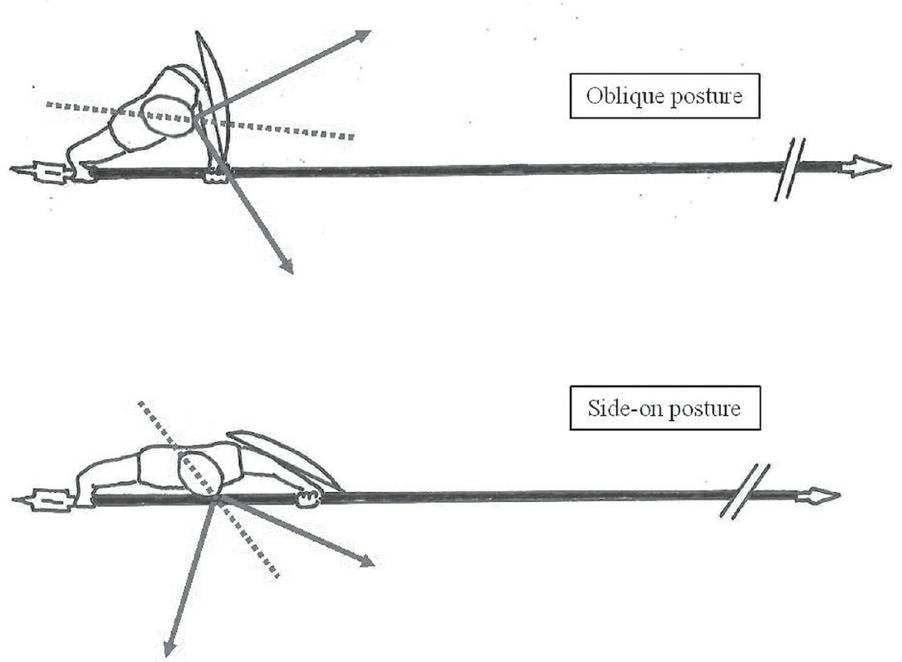

The results of this test showed that, even with the enclosed protection of the Phrygian style helmet, a phalangite would still possess a natural range of vision of approximately 90° (45° to either side of the axis of the head) – the same as if not wearing a helmet at all. Furthermore, it was found that with the adoption of an oblique body posture to wield the sarissa, the body naturally rotates slightly to the right, but the head can be turned so that the axis of the head (and the head’s line of sight) is directed towards the tip of the sarissa. With the body in such a position, the rotation of the head is stopped by the lower rim of the cheek guards connecting with the pectoral area of any armour being worn (see Plate 12). However, due to the rotation of the body and the angle of the lower rim of the cheek guard, this occurs when the head is looking directly towards the tip of the sarissa. As Africanus states, if a helmet with no cheek guards, such as the basic pilos, is worn, then there is no impediment to the rotation of the head at all other than the natural range of movement of the neck. This further demonstrates that a side-on posture could not have been used to wield the pike. When standing in this way, and wearing a more enclosed helmet, the head is prevented from being fully rotated to the left by the features of the helmet and so the phalangite’s vision is directed to his front-right, rather than towards the tip of his weapon (Fig. 16).

Fig. 16: The range of vision (solid arrows) and axis of the head (dotted line) of the side-on and oblique body postures.

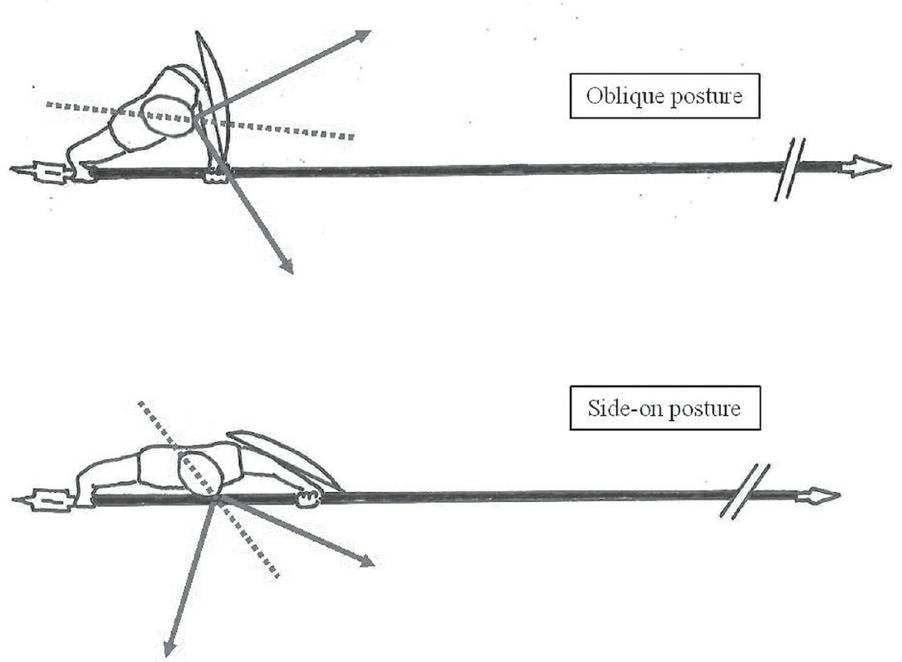

The range of vision provided by the adoption of an oblique body posture allows a phalangite to see, at a ‘pike length’ distance of around five metres, approximately 10m across the front rank of an opposing formation without either turning their head or averting their gaze from the point directly in front of them. This equates to the ability for the phalangite to see at least ten men across the front of an enemy formation if they were deployed, like the pike-phalanx, with an intermediate-order interval of 96cm per man or even more if the enemy formation was arranged in a closer order (Fig. 17).

Fig. 17: How much of an opposing phalanx a phalangite was able to see.

With the shield supported on the left forearm, the upper rim, which sits level with the left shoulder, in no way impedes this range of vision or the ability for the phalangite to look downwards. The visor of the Phrygian style helmet only marginally impedes the vertical range of vision unless the head is moved, but as an offset the visor shields the eyes from rain and sun, while still allowing for objects to be seen up to a height of 5m when they are a ‘pike length’ away.

It was found that the range of vision when wearing a replica fourth century Corinthian style helmet was the same as for its Phrygian counterpart. The nasal guard, a feature of the Corinthian helmet that is absent from many other styles, does not impede vision due to its close proximity to the face. The upper edge of the eye sockets of the Corinthian helmet only marginally impede the vertical range of vision, but also allows objects to be seen up to a height of 5m at a ‘pike length’ distance without moving the head while still providing a modicum of shielding against rain and sun. As the Corinthian is the most enclosed of the Greek helmets of the Hellenistic Period, it can be considered the ‘worst case scenario’ in terms of possible impediments to vision. Yet the wearer of such a helmet still possessed a natural range of vision. Tests were also conducted while wearing reconstructed versions of open-faced pilos, Boeotian and Chalcidian helmets. It was found that the range of vision available when wearing these helmets was the same as being bare-headed (due to the open-faced nature of the helmet) or when wearing either the Corinthian or Phrygian-style helmet. This means that a phalangite wearing any of the styles of helmet common to the Hellenistic Age would have had a natural range of vision and would have been able to see every part of an opponent, from the top of their head to their feet, without moving his head or redirecting his gaze when the two were standing a pike length apart.

A phalangite would have been able to register movement just beyond the margins of this range of vision, but would not have been able to recognize distinct features without turning his head or averting his gaze. Due to the slight rotation of the head to the right caused by the adoption of an oblique body posture, the phalangite would have seen slightly more to his right than to his left. This in no way endangered the phalangite as his left was covered, both physically and visually, by the man beside him in the formation unless he was at the very extreme left of the line. Even here, peripheral vision to the left would have only been required to recognize flanking manoeuvres by enemy troops and would not have been vital to the engagement of an opponent directly to the front.

This conclusion does not take into account atmospheric impediments to sight on the battlefield such as smoke, fog, dust, sun glare or precipitation.⁸ However it can be concluded that, despite such hindrances, all styles of helmet available to the Hellenistic phalangite provided a sufficient range of vision for him to adequately gauge what was going on around them on the battlefield. More importantly, these same helmets allowed the phalangite to observe all potential target areas, armoured or otherwise, on their opponent at a ‘pike length’ distance of 5m or more.

Attempting to correlate how well the phalangite was protected, and how much of an opponent he could see on the battlefield, with the concept of a primary target area in phalangite combat (or even if there was one) is problematic due to the very limited amount of available source material on this subject. Unlike the Greeks of the Archaic and Classical ages, both the Greeks and Macedonians of the Hellenistic Period have not recorded the same level of detail regarding armed conflicts as they had previously done. This dearth of information is consistent regardless of the medium employed.

In the art of the Archaic and Classical periods, combat and conflict, regardless of whether it was mythological, heroic or contemporary in its context, was a common illustrative motif in paintings, vase decorations and monumental sculpture. Within these images are found depictions of weapon impacts and wounds to various parts of the body ranging from wounds to the extremities (such as the vase illustration of Achilles bandaging the wounded left arm of Patroklos [Berlin F2278]) to injuries sustained to the chest, abdomen and upper thigh (the image on a krater showing the death of Sarpedon [NY 1972.11.10]) to hoplites piercing the armour of opponents (the image of a hoplite killing a Persian with a spear thrust to the body which penetrates the armour [NY 06.1021.117]). This rich corpus of artistic representations provides many insights into the dynamics of combat in the earlier ages of Greek history.⁹

However for the Hellenistic Period, this design element seems to almost completely disappear from the artistic record. There are very few representations of the phalangite within the art of the time, and those that do exist are primarily in the form of funerary stele and other grave monuments which generally show the individual being commemorated in a pose other than a combative posture (for example see Plate 8). Consequently, these representations are of little use in the examination of the broader mechanics of the fighting undertaken by the Hellenistic man-at-arms. The one clear depiction of the phalangite in action that does exist, the Pergamon Plaque, despite its combative context, also does not depict a moment of impact between the two opposing sides shown in the relief as the tip of the pikes wielded by the phalangites are obscured by other figures within the image. As such, this pictorial representation can only be used as a basis upon which to build an examination of the phalangite ‘kill shot’ by extrapolating where a weapon held in the manner shown on the plaque would point at an opponent standing directly opposite.

Additionally, there is little evidence available for the results of phalangite engagements in the archaeological record either. Details for the polyandrion at Chaeronea, the supposed burial site of the Theban Sacred Band, for example, was said to have contained many skeletons bearing signs of wounds when the site was excavated in the nineteenth century.¹⁰ Such evidence would have provided a wealth of information about phalangite combat. Unfortunately, the forensic analysis of the remains does not seem to have been a priority for the excavators, photographs of the finds have never been published, nor has the initial excavation report by Stamatakis, and the site has not been re-excavated since.¹¹

It is also not only remains of actual combatants from the Hellenistic Period that we have a lack of archaeological evidence for. During the time of the Peloponnesian War (431-404BC) the practice of dedicating arms and armour taken from a defeated enemy to religious sanctuaries seems to have gone into decline in Greece – possibly due to not wanting to glorify a conflict in which Greeks were fighting against fellow Greeks.¹² The depiction of combative scenes in Greek art also declines around this time, possibly for similar reasons.¹³ Consequently, by the time of the Hellenistic Period, there are no examples of pieces of armour, which may bear the marks of impacts made with the sarissa, dedicated to cult centres like Olympia and Delphi. This also hampers the examination of the ‘kill shot’ of phalangite combat. Due to the lack of artistic and archaeological evidence for the nature of conflict in the Hellenistic world, any analysis must primarily base itself on other forms of evidence – in particular the literary record.

Yet even here the accounts for the Hellenistic Age are much more limited than they are for the earlier Archaic and Classical Periods. As far back as the works of Homer, Greek writers seem to have gone out of their way to emphasize the bloody nature of fighting involving hoplites. The poetry of Tyrtaeus, the narrative histories of Herodotus, Thucydides and Xenophon, and the plays of Aristophanes, Sophocles and Euripides, all contain graphic references to wounds and fatalities suffered at the hands of the hoplite’s primary weapon – the doru. However, much like every other source of evidence available for the Hellenistic Period, the narrative histories recounting the events of the time contain a significantly reduced number of specific references to injuries inflicted by the sarissa. Instead, the ancient narratives mainly provide massed casualty statistics at the end of an account of a particular engagement – mainly because the focus of most narrative histories is on the key personalities of the time (who usually commanded cavalry rather than infantry), and/or because the sources used by the narrative historians, even if eye-witnesses to the encounters, were generally not part of the infantry engagement.

This is not to say that there is a complete lack of references to the actions of the phalangite in the ancient literature. In fact, while somewhat limited in number, the ancient literary record does contain a number of key passages which refer to the use of the sarissa against specifically targeted areas on an opponent on the battlefield depending upon the tactical circumstances and requirements of the engagement. Plutarch, for example, describes how, at the battle of Pydna in 168BC, the Macedonians pressed the tips of their sarissae into the shields of the Romans in order to keep them at a distance where they were unable to strike the phalangites with their shorter swords.¹⁴ Later, in the same engagement, opposing troops who charged against the phalanx suffered great losses as the pikes are described of having the ability to ‘pierce those who fell upon them, armour and all, as neither shield nor breastplate could resist the force of the sarissa’.¹⁵ Livy similarly states that had the Romans made a frontal attack against the phalanx, they would have impaled themselves.¹⁶ Earlier, in 327BC, Alexander’s pikemen engaged a contingent of lightly armed mercenaries and ‘thrust their sarissae through the pletae of the barbarians and pressed the iron point into their lungs’.¹⁷

Such references indicate a primary use for the sarissa, across the entire Hellenistic Period, where the weapon is held so that the tip points directly at the shield/chest of an opponent standing directly opposite. This correlates with the depiction of the phalangite in action shown on the Pergamon Plaque. Holding a pike at waist level, and using an oblique body posture to provide strong and stable footing, braces the weapon in position so that it can be more effectively used to hold an opponent back by pressing the tip into the opponent’s shield (as per the battle of Pydna). A weapon supported in this manner is also wielded with sufficient strength so that a charging opponent will impale themselves upon the presented weapon. Additionally, a pike wielded at waist level can also be used to deliver a strike with sufficient power to penetrate the shield carried by an enemy and continue on into their body (as per the accounts of Alexander’s men in 327BC). Such uses of the sarissa cannot be accomplished with a weapon held at shoulder height and/or carried in a side-on posture (see The Reach and Trajectory of Attacks made with the Sarissa [from page 167] and The Penetration Power of the Sarissa [from page 225]).

Furthermore, any weapon held at shoulder height will have the spike of its butt pointing directly at the face of the man in the rank behind. This would be extremely dangerous as any impact against the presented pike, such as an opponent charging upon it, runs the risk of forcing that weapon backwards with the result that the member of the second rank could actually be killed or severely injured by the weapon held by the man in front of him. This aspect alone indicates that it was unlikely that the sarissa was presented from shoulder height to engage in combat.

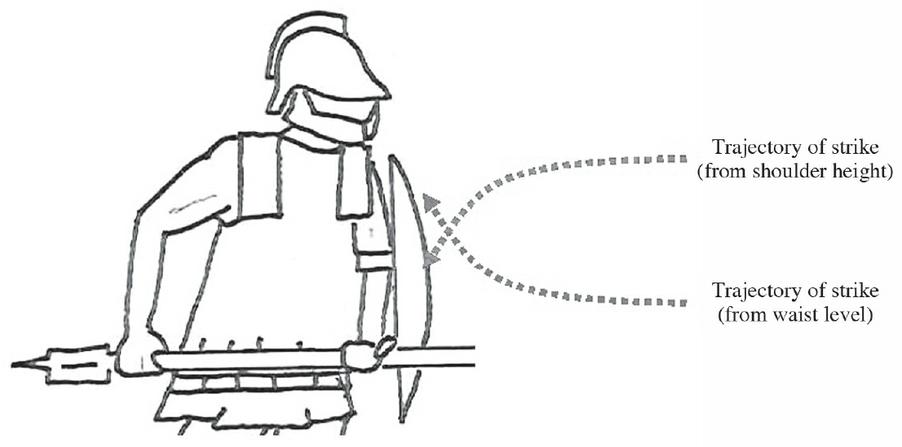

The only time in which a sarissa may have been held higher than waist level would have been if the phalangite was standing in an elevated position. Diodorus describes how Ptolemy, defending the Fort of Camels in 321BC, stood on the wall of the fortification and put out the eye of an attacking elephant with a sarissa.¹⁸ Similarly, at Thermopylae in 191BC, pikemen deployed along the top of a wall used their weapons to strike downwards at those who were trying to scale it.¹⁹ At Raphia in 217BC men fought with pikes from small towers mounted on the backs of elephants.²⁰ In such positions, it would be more likely that the sarissa was held higher than waist height as the more elevated deployment of the weapon would allow the phalangite to strike downwards at a rather acute angle, over crenellations and other protection, in order to engage targets that were below him. This would not be possible with sarissae held at waist level. However, it is important to note that a phalangite either on a wall or on the back of an elephant would not be part of a phalanx and, as such, his actions would not be dictated by the confines of that formation and he would be free to use the best means to attack his opponents. The weapons (in particular the butt) of phalangites in such positions would also pose little threat to those behind them (if indeed there was anyone positioned there). While the use of the sarissa in an elevated posture would have been the easiest form of offensive action for troops in elevated positions, it is unlikely that such a mode of deployment was used within the phalanx itself and weapons deployed as part of the standard battleline would have been wielded at waist height. Deployed at this level, the pike could then be used to either deliver an offensive strike to the chest, or used defensively to hold an enemy at bay by pressing the tip into the opponent’s shield.

According to the ancient texts, at other times the sarissa was aimed at a more elevated target area of an opponent’s body – the head. The references to surviving wounded visiting the Asclepion at Epidaurus, with wounds sustained from strikes delivered with the longche, which seems to be another term for the sarissa, suggests that the pike could be aimed at the face.²¹ Curtius similarly describes how, at the battle of Issus, Alexander’s phalangites, who were experiencing stiff opposition from the Persians as they tried to cross the river, ‘were so densely packed that the wounded could not withdraw from the front, as on other occasions, and so they could only advance by killing the man in front of them’.²² In order to quickly dispatch their opponents to expedite their advance, Alexander’s phalangites directed their attacks at the faces of those arrayed against them.²³ Despite what this passage and the inscriptions from Epidaurus state, it is important to note that because Curtius goes out of his way to emphasize that Alexander’s troops had to resort to striking at their opponent’s face in order to advance suggests that strikes to the head were not the standard battlefield practice for phalangites.

Another indicator that the face and head were not generally targeted in phalangite combat is the number of references to either ‘walking wounded’ or to individuals suffering numerous wounds, in the ancient texts. Many of these passages are in relation to people who had faced a pike-phalanx but survived. At Chaeronea in 338BC, the Athenian dead had ‘wounds all over’ (adversis vulneribus omnes loca).²⁴ At Halicarnassus in 334BC, many of the Greek mercenaries facing Alexander’s assault suffered ‘frontal wounds’ (τραυμασιν ἐναντίοις) while others were carried away from the battle unconscious.²⁵ Diodorus similarly says that the Spartan king, Agis III, received ‘many frontal wounds’ (πολλοῖς τραύμασιν ἐναντίοις) when facing the pike-phalanx of Antigonus at Megalopolis in 331BC, was carried from the field, but was still able to defend himself to the last.²⁶ Some 4,000 men of Antigonus’ army, wounded at the battle of Paraetacene in 317BC, were sent to a nearby town.²⁷ Walking wounded from the battle of Sellasia in 222BC returned home.²⁸ At Pydna, the Roman Marcus, son of Cato, received ‘many wounds’ (τραύμασιν ὤσαvτες).²⁹ Livy states that the number of Roman wounded at the battles of Magnesia (190BC) and Pydna (168BC) were somewhat greater than the number of fatalities he claims the Roman army suffered.³⁰

What suggests that many of these reported injuries were not wounds sustained to the head or neck is that the region of the face, neck and throat contains many vital areas such as the jugular vein, the carotid artery, the thyroid cartilage and the jugular arch, as well as the eyes and many other nerves and ancillary blood vessels. When wearing any of the open-faced styles of helmet common to the Hellenistic period, all of these features are left exposed. Injuries sustained to any of these areas are incapacitating at best – if not immediately fatal. For example, a relatively deep penetrating wound to the eye, even delivered with nothing but a finger, can pierce the thin layer of bone at the back of the orbital socket, enter the brain, and kill the recipient instantly.³¹ The severing of the carotid artery with a hit from a sharp implement like a pike-head will result in unconsciousness after approximately five seconds and the recipient of such an injury will be beyond medical help after about ten seconds – with death occurring shortly thereafter.³² The crushing of the thyroid cartilage, through even a reasonably light blow which may not even break the skin, will cause the windpipe to swell and cause a suffocating death in a matter of moments.³³ A stronger blow which pierces the trachea spills blood into the windpipe and makes breathing impossible due to a reflex gagging action. A victim of this kind of injury will choke on their own blood in a matter of moments.³⁴ The sensitive and vital nature of the neck was an aspect of human anatomy well known to the ancient Greeks as far back as the Archaic Age. In the Iliad, the Trojan prince Hektor is killed by a wound to the throat, an area of the body described by Homer as a place ‘where a wound is most quickly fatal’ (ἵνα τε ψυϰῆς ὤκιστος ὄλεθρος).³⁵

Due to the rapid lethality of most wounds to the neck and throat, the references to walking wounded found in the ancient accounts of Hellenistic battles can only be descriptions of individuals who have suffered an injury to another part of the body. The unconscious combatants who were pulled from the front line at Halicarnassus in 334BC, for example, are most likely to have suffered other wounds – such as a blow to the head which was strong enough to knock out the individual, but not strong enough to pierce the helmet, or wounds to the chest which have caused the recipient to pass out due to shock and/or blood loss. It is unlikely that the unconscious condition of these wounded soldiers was the result of a wound to the neck or throat (despite the fact that many such injuries do cause a loss of consciousness) as the short amount of time between unconsciousness and death in such cases would make it more likely that such combatants would be classed as casualties rather than unconscious individuals as is stated by Diodorus. Those wounded that either returned home under their own power, or were transported to another place, are even less likely to have suffered an injury to the neck or throat.

Despite this, undoubtedly armies who faced the Hellenistic pike-phalanx suffered casualties – whether quick kills to the face or neck, or incapacitating (if not fatal) wounds to the chest.³⁶ Diodorus states how corpses piled up at the battle of Chaeronea in 338BC.³⁷ Many combatants fell on both sides of the pike-phalanx versus pike-phalanx clash (φαλαγγομαχεῖν) at Paraetacene in 317BC – a struggle which had gone on for ‘a considerable time’ (ίκανὸν μὲν χρόνον).³⁸ A great mound of bodies and equipment is similarly said to have littered the field following the battle of Pydna in 168BC.³⁹ All of these passages show that the pike-armed phalanx could inflict considerable damage among those who faced it.⁴⁰ By correlating these descriptions to the other passages from the ancient texts which refer to a specifically targeted area in phalangite combat, aspects of the mechanics of these engagements can be better understood.

For example, the fact that the battle of Paraetacene is described by Diodorus as lasting ‘a considerable time’ suggests that the pikes employed by both sides were not primarily aimed at an area on an opponent such as the head which would result in a quick kill. If the sarissa was primarily used in such a manner, and almost every hit resulted in the death or incapacitation of a combatant on one side or another, it is hard to comprehend how a battle of pike-versus-pike could last so long as to warrant such a description. This, in turn, suggests that the pikes were being used in a manner that did not cause immediate injuries – most likely by pressing them into the shield of the man opposite to limit the advance of the enemy formation as occurred at the battle of Pydna. During such a struggle, pikes would have undoubtedly slid off some of the shields they were pushed into – either upwards into the opponent’s face, or downwards into their legs. At other times, if the opportunity presented itself, a phalangite would have exploited an opening in an opponent’s defensive posture or armour to direct a strike at a vital area of the body that was the least protected and which would result in a quick kill – such as the head as the Macedonians had done at Issus, or the chest as they had done at Pydna.

The sarissa was an effective penetrating weapon and could easily pierce the different types of armour common to the Hellenistic Period (see The Penetration Power of the Sarissa from page 225). Thus the chest, if the opportunity presented itself, was an easily targeted area on anyone facing a pike-phalanx. This is clearly illustrated by the account of the mercenaries fighting for the Persians who were faced by the Macedonians in 327BC, whom Diodorus states received wounds to the chest from weapons that passed through their shields. Diodorus also states that many of the Persian dead at the battle of Issus were not wearing any armour at all which suggests strikes delivered to the chest of lightly-armoured opponents.⁴¹ Consequently phalangite combat, at least from the perspective of the ‘kill shot’, does seem to have been a rather technical exercise rather than simply having two opposing formations of heavily-armed men hammering away at each other with a frenzied storm of undirected blows. Rather, it seems that the sarissa was used, first and foremost, to hold an enemy formation in place. As an engagement progressed, opportune shots against available and specific target areas like the chest or head would have been exploited to wear an opposing side down depending upon the armament of the opponent, while other elements on the battlefield came into play to bring the encounter to its climax (see The Anvil in Action from page 375).

This then provides another reason for why there is a distinct lack of references to injuries and fatalities inflicted by the sarissa in the ancient texts – basically because the sarissa is primarily not a strike weapon. Rather, it is used more as a defensive implement to hold an opponent back until an opportunity to kill him is presented. Thus there is not a specific ‘kill shot’ in phalangite combat as such. Instead the sarissa is used in a defensive manner until an opportunity presents itself where it could then be used in an offensive manner. Based upon the length of the sarissa and the manner in which it was wielded, the most opportune target areas on an opponent would have been firstly the chest and secondly the head.

Again, it seems unlikely that the pike was wielded at shoulder height or in a couched position. Weapons carried in such ways point directly at the throat of an opponent standing directly opposite. If the two opposing sides were only a ‘pike length’ apart (i.e. the opponent was abutted up against the sarissa when it was held in its ‘ready’ position), any strike delivered from shoulder height would almost always impact the face or neck – most likely resulting in the slaying of any opponent who did not deflect the blow with his shield. This then goes against most references to impacts made by the sarissa against lower areas such as the chest and shield and against references to walking wounded. While it is possible to allow the tip of an extended pike held at shoulder level to dip, and so point at the chest and shield, the very nature of the stance and position used to deploy the pike in such a manner makes it almost impossible for it to account for the details of pikes penetrating shields, breastplates and flesh or of the weapon being used to hold an opponent at bay. Additionally, a weapon held at shoulder height but angled down towards the shield becomes something of a redundant strike weapon as, due to the length and weight of the pike, and the muscular fatigue caused by holding it in an elevated position for any length of time, it is very difficult to quickly alter the pitch of the sarissa and exploit opportune shots to the head or neck.

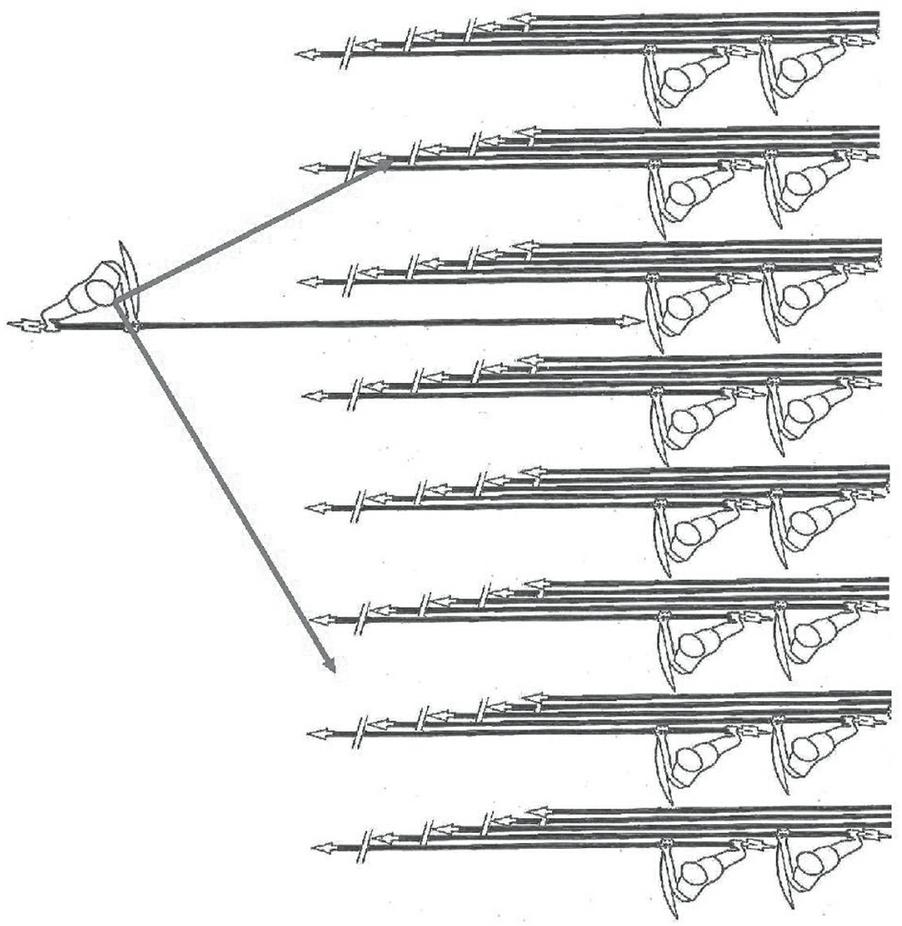

If the two opposing sides are separated by more than a ‘pike length’, and the combat is reliant upon individuals thrusting at their target(s), wielding the pike at shoulder height also presents problems. The accounts of walking wounded who had suffered impacts to the face would suggest that the pike was held level with this target area. However, whereas repositioning the tip of the pike from shoulder height to press into the shield of an opponent is unlikely, a sarissa held at waist level can easily be angled slightly upwards and still be an effective weapon against an opponent’s head – especially if he was wearing a more open faced style of helmet (see following). Furthermore, the slightly upward swinging trajectory of a thrust executed from the low position automatically means that any attack made will rise towards the head of an opponent as the attack reaches the full effective range of the action (see The Reach and Trajectory of Attacks made with the Sarissa from page 167). On the other hand, attacks made from an elevated position will follow a downward curving trajectory and therefore move the tip of the pike away from pointing at an opponent’s face to strike the shield or chest (Fig. 18).

Fig. 18: The trajectories of attacks made with the sarissa from different starting positions.

Thus weapons wielded at waist level can easily account for the two main target areas for which there are descriptions (the shield/chest and the head) whereas weapons held at shoulder height can only account for the head shots when both sides are abutted against each other. This then suggests that the sarissa was normally wielded for combat by carrying it at waist level.

The simple fact is that chest/shield of an opponent was the easiest area to target because this is what the sarissa points at when it is held in its ready position. By keeping the pike lowered in this position, it could be used to press into an enemy’s shield to keep him at bay, be used to probe his defences with small jabs to try an move the shield out of the way and then, should an opportunity present itself, a stronger thrust could be delivered to the area of the chest. Importantly, at no stage in this process does the grip on the weapon change, nor is the weapon elevated or its pitch altered. This results in a method of combat that is the least taxing on the muscles and joints of the arm which would then allow the phalangite to engage for an undetermined period of time.

Another point to consider is that the chest of an opponent is simply a much larger target area than the head – it is the ‘centre of the seen mass’ to use modern military parlance. An alteration of the angle of a weapon pointed at the head by only a few degrees would be enough to make the strike miss the target. However, a weapon aimed at the chest and torso, with its pitch altered to the same degree, would still most likely strike the opponent – albeit not in the desired area and possibly not in a vital part of the body. The required alteration of the pitch of a weapon held at waist height to strike at the head – particularly a heavy weapon like the sarissa – also takes a brief moment of time. Weapons pointing naturally at the chest can simply be jabbed forward quickly as a target area presents itself. However, adjusting the pitch of the weapon, accounting for any flex that this movement has caused, and then thrusting upwards towards the face, all adds to the amount of time needed to deliver the strike. While this added time can be measured in fractions of a second, it may still be enough time for an opponent to realize what was happening and meet the strike with his shield. Thus strikes made towards the chest, especially if the opponent’s shield has been forced out of the way and/or they are off balance, are the quickest and most efficient attacks to make with the sarissa.

At other times, again if the opportunity presented itself, the head would be targeted. Discounting ‘accidental’ strikes which were the result of pikes sliding up a shield into the opponent’s face, there would have been several other reasons for why an ‘opportune kill-shot’ of phalangite combat would have been an attack to the head. One of the main reasons would have been that the area of the neck and head is the most vital area of the body that is close to where the tip of the sarissa is pointing when it is deployed in its ‘ready’ position or when it is being used to hold an enemy back. Should a phalangite need to dispatch his opponent quickly, as occurred at Issus, then an area that would result in a quick kill would be targeted. In this instance the phalangite would need to alter the pitch of his weapon by around 5° in order to make the strike. With the forward left hand acting as the fulcrum for the weapon, its deployed angle can be adjusted either by pushing downward with the rearward right hand (which then raises the tip), raising the left hand and keeping the right hand in place (which also results in raising the tip of the weapon), or a combination of both. While placing a small amount of muscular stress on the arms, this was simply the cost of dispatching an opponent quickly. However, the cumulative effects of doing this too often suggest that the head was not regularly targeted. Weapons held at shoulder height, on the other hand, require the application of significantly more muscular force to alter the pitch rapidly. At no time when altering the pitch of a weapon held at waist height is the phalangite’s field of vision taken away from looking towards the tip of his weapon and the whole of the opponent remains visible while the pitch of the sarissa is adjusted and the strike delivered.

Additionally, very little force is needed for a bladed weapon, such as a pike-tip, to penetrate the flesh of the neck or the soft tissue of the eye to a fatal depth. Many of the vital blood vessels of this area are only millimetres below the skin. Some vital areas, such as the thyroid cartilage, can be fatally damaged with a blow so light that the skin is not even broken. It requires the application of only 2ft lb of pressure to cut flesh. Significantly more energy than this can be produced with a thrust made with a sarissa (see The Penetration Power of the Sarissa from page 225). This makes the regions of the neck and face quite susceptible to serious or fatal injuries. However, it is unlikely that this region was continuously targeted in combat as keeping the pike pitched upwards for a protracted period of time begins to make the arms fatigue much more quickly than simply holding the weapon level. Consequently, while a vital and vulnerable area of the body, the sheer weight of the sarissa, combined with how it was wielded at waist height, made it impractical for the region of the head to be the main target area in combat and attacks would only have been directed at the head sporadically. References to those who had suffered wounds to the jaw or cheek from the longche but survived can be considered accounts of those (lucky?) few who had received blows from this weapon to an area of the head that does not contain any vital blood vessels.

What further suggests that the head was only an ‘opportunity shot’, rather than the primary target of phalangite combat, is the nature of the protection given to this area. If the head and neck were regularly targeted in phalangite combat, then the use of open-faced styles of helmet like the Attic, Chalcidian and pilos would have been completely redundant – especially during the Age of the Successors when fighting was often pike-phalanx against pike-phalanx. In the warfare of Classical Greece, the neck was doubly protected behind the elongated cheek flanges of the common Corinthian helmet and the offset rim which ran around the circumference of the larger hoplite aspis. Yet in Hellenistic warfare, these two elements of protection to the head almost totally disappear. This suggests that the head was not the primary strike area for a phalangite in combat. The use of open-faced helmets and the reduction of other forms of protection for the neck and head also shows that the shoulder height position to wield the pike suggested by Smith could not have been used. In the confines of a phalanx, any sarissa held in this manner would have its spiked butt pointing directly at the face of the man in the rank behind. It is unlikely that such a comprehensive mode of warfare would develop where the weapons being used posed just as much danger (if not more so) to the rearward ranks of the formation as they did to the enemy.

However, it does seem that the Macedonians did recognize that the head could occasionally be struck as this would account for the continued use of certain styles of helmet which provided facial protection such as the so-called ‘Thracian’ helmet or the masked Phrygian helmet. The use of these helmets shows that, while the head/neck does not seem to have been the main targeted area on an opponent, it was clearly recognized by some that the area was both vital and vulnerable and therefore required some degree of protection.

Another point for consideration in relation to the reasoning behind a head ‘kill shot’ is that due to the small amount of penetration depth required to inflict a fatal injury to the area of the head or neck, the weapon used would be less likely to become lodged in the opponent if a quick kill was what was sought. If a bladed weapon is thrust into the chest, the elasticity of the skin causes the flesh to close around the penetrating weapon. Suction caused by the moist tissue of the body then causes drag on the blade and inhibits the extraction of that weapon. This is why modern soldiers are taught, once they have thrust a bayonet into an enemy, to twist the rifle (and therefore the bayonet as well) before attempting to extract the blade. By twisting the bayonet, the wound is ‘opened’, the suction is relieved, and the blade can be more easily withdrawn.⁴² Such techniques were also known in the ancient world. The Roman writer Vegetius, for example, advises Roman legionaries to thrust the tips of their short swords only 2in into the body of an enemy.⁴³ Vegetius goes on to describe that, no doubt due to the width of the blade of the Roman gladius, a penetrating wound delivered to this depth was generally fatal. However, another benefit of such a shallow wound is that there would have been less surface area of the blade susceptible to the suction of the opponent’s flesh, making the sword easy to recover.

Livy describes the horror experienced by Philip V and his army upon seeing the wounds inflicted by the gladius for the first time.⁴⁴ Livy states that Philip V’s men were accustomed to the sight of wounds inflicted by spears and arrows due to their prior campaigns against the Greeks. What scared these men the most was the sight of dismembered and disemboweled bodies which had been the result of attacks made with the Roman short sword.⁴⁵ This then suggests that the Greeks, and probably the Macedonians as well, did not regularly target an area of the body, or strike it to a depth, which would cause such injuries. The head of the sarissa was also smaller than the width of the average gladius. Thus the majority of the fatalities that were the result of actions involving phalangites were likely caused by relatively shallow strikes to a vital area of the body, either the torso or the neck and head, which did not leave wounds of a significant size.⁴⁶

Moreover, the Roman gladius, being a relatively short weapon, could also be twisted (much like the modern bayonet) to aid extraction. However, attempting to undertake a similar practice with a pike 5m in length or longer is somewhat more problematic. Due to the length and weight of the sarissa, it is difficult to apply enough rotational torque with the wrists to sufficiently rotate a blade embedded in a target. Additionally, as the sarissa seems to have come in two halves, applying any rotation to the rear half, which was gripped in the hands, would have little effect other than to make the rear end rotate within the coupling sleeve if the forward half was held rigidly in place. Consequently, it is impossible to twist a pike with such a configuration and so ‘open’ a wound on an enemy to help withdraw the weapon.⁴⁷ This again suggests that softer and/or thicker parts of the body such as the torso, and even fairly rigid pieces of armour like shields and breastplates, were not regularly struck deeply with the sarissa. This then corresponds with the concept of the sarissa being primarily a defensive weapon to help hold an opponent at bay unless they were very lightly armoured.

Furthermore, in the confines of a deployed phalanx there would be little or no room for a phalangite in the front rank whose weapon had become embedded in an opponent to step back and use his body weight to try and dislodge it. Due to the difficulties involved with attempting to recover a lodged weapon, it can only be assumed that enemies who impaled themselves on opposing pikes through the momentum of their charge, as occurred at the battle of Pydna, subsequently rendered those weapons completely useless as there would have been no means for a phalangite to extract a weapon which had sunk deeply into an opponent’s chest or abdomen, and who had then fallen to the ground when they were slain. Under such circumstances a phalangite would have had little recourse except to resort to using his sword as a secondary offensive weapon if he was unable to fall back to the rear of the formation.

For opponents facing a pike-phalanx, one way to inhibit the offensive actions of the phalangites would be to allow them to press the tips of their pikes into your shield (assuming that it was sturdy enough to withstand the force of the weapon). By doing so, the tip would penetrate the wood of the shield to a shallow depth. This would then hold the entire pike in place and so prevent both accidental deflection into either your head or legs, and prevent the opponent from altering the pitch of their weapon to deliver an opportune strike. Thus an effective shield for engaging a pike-phalanx had to be able to allow very shallow penetration, but be sturdy enough to withstand the pressures placed upon it. To counter this, the phalangite would have pushed his pike forward, attempting to drive the opponent back so that the tip of the sarissa could be withdrawn from the surface of the shield, and a quick strike to the opponent’s chest or head could be delivered while they were off balance.

A review of the evidence, combined with an understanding of the fundamentals of Hellenistic combat, allow for the questions over the concept of the main ‘kill shot’ of phalangite warfare to be addressed. It seems that the long sarissa, wielded at waist level, was primarily used to hold an opponent in place, preventing him from reaching the phalangite with a shorter reach weapon like a sword or spear. In engagements where a pike-phalanx fought against another pike-phalanx, these same initial principles applied with both sides using their weapons to keep their opponents at bay. During the course of the encounter the phalangite would have continued to use his weapon in the same manner – pushing forward with the weight of his body and the weapon to both hold the enemy at bay and to probe his defences by slightly adjusting the position of the pike to try and move the opponent’s shield out of the way or force them back. When this occurred, certain areas of the opponent’s body would become exposed for a brief moment. At this stage the phalangite could either direct an attack towards the opponent’s chest which would require no alteration of the pitch of the weapon and would be slightly quicker to deliver, or take a short moment to alter the pitch of the weapon and strike at the opponent’s head, to either kill or incapacitate him.