Much like the sauroter affixed to the rear of the hoplite doru, the large, heavy, metallic butt-spike on the rear end of the sarissa served a number of purposes. Its primary function was to provide the weapon with the correct point of balance. Additionally, the butt-spike protected the end of the shaft from the elements and its pointed end allowed the weapon to be thrust securely upright into the ground when not in use. This is quite easy to accomplish with the hoplite doru as its relatively short length and low weight allow it to stand unsupported in a vertical position simply by thrusting the sauroter into the ground.

However, such an action is much harder to accomplish with a sarissa. The weight of the sarissa (5kg) was considerably more than that of the doru used by the hoplite (1.5kg). Furthermore, the sarissa was considerably longer (some 5.7m compared to 2.5m). As such, it is much harder to get this weapon to stand up on its own. Only a minor deviation away from the vertical will cause the weapon to tip over – especially if the ground is soft and/or the spike on the butt is not thrust into the ground sufficiently. This is where many of the design elements of the sarissa butt, which differ from the hoplite sauroter, came into play and may partially explain the variances in design between the example of the winged sarissa butt found at Vergina and the traditional hoplite sauroter which came in the form of a conical or pyramidal spike. The wings on the sarissa butt recovered from Vergina would help stabilise any weapon thrust upright into the ground regardless of the consistency of the soil. If the earth was relatively hard packed, then the weapon could be thrust into the ground at least as far as the elongated spike on the end of the butt – a depth of 14.5cm. From here the small wings, acting almost like four feet splayed out on the corners of the butt, would then help keep the weapon vertical. If the soil was quite soft, sand for example, then a sarissa with a winged butt could be thrust even deeper. The splayed wings then provide a greater surface area for the soil to purchase onto – providing greater resistance against toppling and helping to maintain the weapon in a vertical position.

The Newcastle butt, while shaped in a conical spike similar to many examples of the hoplite sauroter, is considerably longer than the spear butts used in the Classical Period on the lighter doru. This means that more than half the Newcastle butt’s 38cm length is nothing but a spike that could be thrust deep into soft soil or as far as it could go into more hard packed surfaces. In either case, the sheer length of the spike would aid in supporting an upright weapon. Thus is seems that the design of the sarissa butt, and not just its weight, had an important role to play in the overall functionally of the weapon. However, were balance, protection of the end of the shaft, and the ability for the sarissa to be thrust upright into the ground when not in use the only functions of the butt?

Lucian outlines at least one defensive use of the sarissa butt in a combative situation. He explains that one of the tactical uses of the butt was to plant it into the ground so that the pike could be braced into position and then used defensively against an enemy horseman.¹ In his account of this action, Lucian describes how the pike transfixed both the horse and rider at the same time. Lucian also provides details of the position that the pikeman (in this case a Thracian) adopted and exactly where the pike pierced both the rider and his mount:

[A] Median (Arsaces) was charging with his 20 cubit (εἰκοσάπηχύν) lance in front of him; the Thracian knocked it aside with his peltē; the point glanced by; then he knelt, received the charge on his pike, pierced the horse’s chest – the spirited beast impaling itself by its own impetus – and finally ran Arsaces through groin and buttock.²

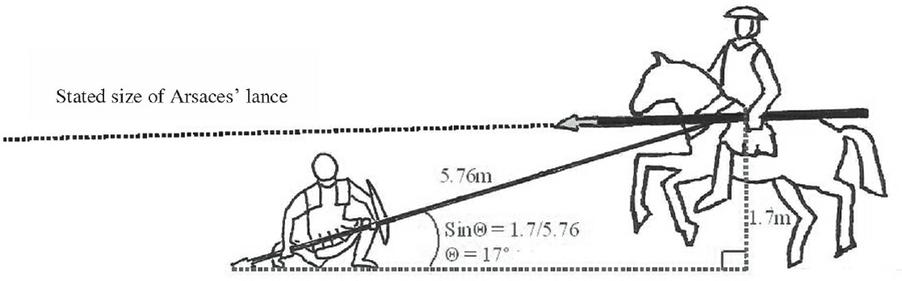

From such details we can gain a further understanding of how such an action was accomplished. Depending upon the exact breed and size of the horse being ridden, the region of Arsaces’ groin and buttocks would be approximately 1.7m off the ground as he sat astride his mount. If the pike being carried by the Thracian was, for example, the same length as the sarissae being carried by the phalangites of Alexander the Great (12 cubits or 576cm long), this then allows, using basic trigonometry, for the angle of the pike to be calculated so that it will pierce both the horse’s chest and the rider’s groin as is stated by Lucian (Fig. 19).

Fig. 19: Calculation of the angle required to impale a horse and rider with a 12 cubit sarissa.

The relatively small angle at which a pike of this length has to be deployed to be directed at the targets detailed by Lucian (17°) explains why the Thracian was required to kneel. Such an angle could not have been accomplished if the Thracian had remained standing. Furthermore, it becomes clear that, for a similar action to be taken against infantry, the angle would have to be decreased even further in order for the tip of the pike to descend below head height. This, in turn, suggests that such a position was not adopted to receive an attack of enemy infantry, and it is more likely that in such circumstances the sarissa would have simply been wielded at waist level so that the enemy could be engaged directly – as is shown on the Pergamon plaque (see Plate 7). Interestingly, the Pergamon Plaque shows phalangites engaging both infantry and cavalry. Consequently, it seems that it was not a necessity of phalangite combat for the combatants to kneel in order to engage mounted troops and either posture (standing or kneeling) would have been used depending upon the tactical situation of the engagement.

Additionally, in assuming such a defensive position as a kneeling posture, the hands do not have to be shifted from their correct placement. All the phalangite has to do to adopt such a posture is to step forward slightly with their left foot as they bend down and ram the spike of the butt into the ground. The kneeling posture means that, with the hands kept in their original position, the pike will automatically be repositioned at an angle of around 17°. The hands can then simply be used to maintain the angle of the pike and allow the momentum of the incoming opponent to do the rest. As the position of the hands does not have to be altered, and therefore no more of the pike extends behind the bearer than would have normally been the case, such a defensive posture could be adopted by every member of every rank of a phalanx deployed in an intermediate order of 96cm per man.

Some scholars have suggested that the butt of the sarissa could be used as an ancillary weapon if the head and/or shaft of the pike broke during the course of a battle.³ The use of the hoplite sauroter in such a capacity is also a part of many theories on the mechanics of hoplite combat, but this concept seems to be in error.⁴

Markle cites a passage of Polybius (6.25.9) as evidence for the use of the sarissa butt as a secondary weapon. Polybius states that the problem with the Roman cavalry lance is that it does not possess a spike on the rear end of the shaft and that, if the head, breaks off, the weapon becomes useless whereas the Greek lance, which did have a butt, could still be used. Polybius states that Philopoemen used the butt of his cavalry lance to kill the Spartan Machanidas at the battle of Mantinea in 207BC.⁵ However, Polybius’ description of the advantages of the Greek cavalry lance can in no way be interpreted as saying that, because the sarissa carried by infantry (rather than the cavalry lance as is specifically mentioned by Polybius) did have a spike on the end of its shaft, that it could therefore be used as a secondary weapon in the case of breakage. It must be remembered that the cavalry lance had a butt very different in configuration to the infantry pike – more like a large spearhead than an elongated spike (see Plates 3-4).

Furthermore, even though the Greek and Macedonian cavalry lance did have a large butt, it does not seem to have been regularly used as a secondary weapon anyway – even when the primary head broke off. When the lances carried by Alexander’s cavalry broke at the battle of the Granicus in 334BC, Arrian and Plutarch state that these broken weapons were abandoned in favour of swords or replacement lances; the butt-spike appears not to have been used as a secondary weapon.⁶ Diodorus, in his account of the battle, states that when the tip broke off the lance that Alexander himself was carrying, he continued to thrust the jagged end of the shaft at the faces of his opponents rather than turn the lance around and engage with the butt.⁷ This suggests that, despite what Polybius states, even when equipped with a weapon which would allow them to do so, Macedonian cavalry rarely resorted to the butt of the lance as a secondary weapon.⁸ Importantly, such a passage can in no way be extrapolated as being a reference to the use of the sarissa butt as a secondary weapon by phalangites in the massed confines of the phalanx as some scholars assert.

Any theory which proposes the use of the butt of the sarissa as a secondary weapon is reliant upon the assumption that the head of the weapon could break off during combat and force the bearer into a position requiring recourse to an alternative means of offence. The references in Arrian, Plutarch and Diodorus to the head of the Macedonian cavalry lance breaking clearly demonstrates that such a thing could occur to mounted troops. Cavalry, by its very nature, regularly charges into combat. Consequently, the momentum of the charge, and the collision with the enemy, would have been a contributing factor to the breakage of many cavalry lances. However, under what conditions, and how regularly, would this have occurred among the heavy infantry?

The ancient sources provide a few accounts of events where the front of the sarissa was broken off. Frontinus, for example, states that, at the battle of Pydna in 168BC, the Roman commander Aemilius Paulus ordered his cavalry to ride across the front of the opposing phalanx while covering themselves with their shields so that the heads of the Macedonian sarissae would be broken off.⁹ In this instance it can be assumed that the cavalry were riding from left to right, with their shields covering their left-hand side, and using the edge and face of the shield, in concert with the momentum of the moving horse, to hit the extended pikes of the phalanx and sever the heads.

In another example, Diodorus relates how, in the heroic duel between the Athenian Dioxippus and the Macedonian Coragus who advanced into battle with a leveled sarissa only to have Dioxippus, who was armed with a club, hit the end of the pike and shatter it.¹⁰ Similarly, Plutarch states how, again at the battle of Pydna, some of the Romans tried to grab the tips of the sarissae in their hands.¹¹ Plutarch says that the Romans had tried something similar against the pikemen of Pyrrhus’ phalanx at Asculum in 280BC.¹² During the battle of Plataea in 479BC, the Persians had similarly attempted to grab the tips of the hoplite spears arrayed against them, most likely in their left hand, and then use a one-handed weapon wielded in the right hand to try and hack off the end.¹³ Plutarch’s accounts of Pydna and Asculum may be a reference to something similar whereby some of the Romans may have been attempting to grab the sarissa in one hand and break off the end with a weapon held in another as he states that the Romans were also trying to ‘knock aside the sarissae with their swords’.¹⁴ Sheppard suggests that the large hacking macharia style of sword used by the Greeks and Macedonians was a post-Alexander addition to the panoply of the phalangite to be used to try and cut the tips off opposing pikes.¹⁵ Interestingly, in the Age of the Successors, much of the combat was pike-phalanx against pike-phalanx where a weapon capable of severing the tip of an enemy’s pike would have been of great benefit.

It is unlikely that Plutarch’s reference to the Romans trying to grab the sarissa in their hands at Pydna was an attempt to simply try and snap the shaft. Tests have shown that it is physically impossible for an individual to break a spear shaft 25mm in diameter, even when employing both hands in the attempt.¹⁶ It would be even more impossible to snap something thicker such as the 35mm diameter shaft of the sarissa. Thus any attempt to grab the sarissa and render it ineffective would need to make use of another means of severing the head such as striking it with a weapon.

In order to accomplish such an action, certain conditions have to be assumed. Firstly, the weapon used to try and sever the sarissa or spear would have been held in the right hand. Consequently, in order to grab the shaft of the weapon, it must be assumed that no shield was being held in the left hand. This would then allow someone to grab the shaft of the pike/spear with the left hand, pivot inwards and to the left, and bring down a weapon to hack up to the first metre off the end of the weapon. Grabbing hold of the shaft, while potentially dangerous to the person doing so, holds the weapon in a relatively rigid manner which then allows the end to be broken off through the force of the blow from the weapon in the right hand. If the shaft is not grabbed, any blow against the shaft is more likely to simply deflect it rather than break it – this is particularly so for the sarissa with its great length and inherent flex. However, the Romans at Pydna are unlikely to have abandoned their shields in order to undertake such a move. As such, Plutarch’s reference to the Romans trying to ‘knock aside the sarissae with their swords’ must be a description of attempts to parry the incoming weapons rather than an attempt to sever them.

Any attempt to sever the tip from an opposing sarissa with a hand-held weapon like a sword would have required speed – especially in a massed combat situation. It is unlikely that the Persians at Plataea, for example, grabbed the Greek weapons while they were held in their ‘ready’ position and then tried to cut through the shaft as this would have brought any grappling Persian dangerously within range of the spears of the second rank of the Greek phalanx. The Persians could only have attempted to grab the Greek spears at the moment when a hoplite of the front rank had extended their spear into the attack and before they withdrew it again (which would have pulled any Persian holding it onto the spears of the second rank). Consequently, any severing of the Greek spears would need to have been accomplished rapidly; again suggesting the use of a weapon to break the end off. For individual combatants like the duelists Coragus and Dioxippus, this was less of an issue. So long as Dioxippus could safely move outside the danger zone directly ahead of the sarissa (i.e. by either moving ‘inside’ its reach and hacking at the pike from the side, or stepping back as it was thrust forward and striking at it while it was at its full effective range) then he would have been both safe from potential injury and in a position where he could have used his club to snap the head off Coragus’ pike. The fact that Dioxippus is only armed with a club, and bereft of a shield, would have meant that, had he moved ‘inside’ the reach of the pike, he would have been easily able to grab the weapon and then bring his club down upon it. If, on the other hand, Dioxippus simply swung his club at Coragus’ sarissa, for it to shatter the end suggests that the wood had been weakened in some regard or that the head itself was simply knocked off the weapon.

Another possible way of interpreting Plutarch’s account of Pydna and Asculum is that some of the Romans may have been grabbing the Macedonian pikes in an attempt to detach the front half of the sarissa from the rear half. However, this could only be accomplished if a certain set of battlefield conditions were met. For example, in the press of a battle where, as Plutarch describes Pydna, the Macedonians had the tips of their sarissa pressed hard up against the shields of their opponents, it can be assumed that both sides were pushing forward to try and maintain their line and dislodge their opponent, and that the Romans were being held at bay by the length of the Macedonian pikes at the same time. What this would also mean would be that the men of the subsequent ranks on both sides would be pressed almost into the backs of the men in front as the intervals between the lines compressed and the formation as a whole strove to advance. If the intervals of the Roman formation were not compressed in such a way, then any Roman facing the advancing pikes of the phalanx would be simply forced backwards, as the pike was driven into his shield, onto the man behind him by the strength of the Macedonian advance. This would also cause the intervals between the Roman front ranks to compress. Alternatively, if the Romans were advancing and the Macedonian phalanx was attempting to hold its position, then the Roman ranks would still compress as the front rank was stopped in its tracks by the extended sarissae of the Macedonian formation and the rear ranks of the Roman formation continued to press forward. In any scenario, due to the compression of the Roman lines, any legionary in the front rank who managed to take hold of the forward end of a sarissa he was facing would not be able to step backwards in order to provide himself with sufficient room to try and pull the front half of the pike off. Additionally, the idea that an opponent would even attempt to pull the front half of the sarissa off a weapon he was facing must automatically assume that they had abandoned any weapon that they had been carrying in their right hand (and possibly their shield in their left as well). The unlikelihood of this happening, especially if that opponent was another sarissa-armed pikeman, makes such a prospect entirely improbable.

The only way in which such an undertaking would work would be if both formations were relatively static, and with the Romans deployed in something akin to the Macedonian intermediate order of 96cm per man or greater (see The Anvil in Action from page 374). This would then provide the legionary in the front ranks sufficient room to grab onto an opposing weapon which may be pressed against their shield, step back slightly and use the slight increase in room to separate the two halves of the sarissa thus rendering it unserviceable. However, such conditions were rare in phalanx warfare. In almost every engagement from the time of Alexander onwards, at least one (if not both sides) was in motion when the lines met regardless of whether the opponents were Persians, Macedonians, Greeks or Romans, and regardless of whether they were infantry, cavalry, chariots or elephants. Thus the configuration of the sarissa into two halves, while providing numerous benefits to logistics, could not be exploited as the conditions required for an opponent to be able to separate the two halves rarely materialized on the battlefield.

Another way in which the sarissa could lose its head would be if the head itself broke during the course of a battle. This was a fairly common occurrence with the head of the hoplite doru. Euripides states that spears could break as a result of a powerful thrust (ἀπὸ δ’ ἔθραυσ’ ακρον δόρυ).¹⁷ The Greeks at Thermopylae (480BC) resorted to using their swords only once their spears had been broken during the combat of the preceding two days.¹⁸ Xenophon’s account of the aftermath of the battle of Coronea (394BC) lists broken spears among the detritus of the confrontation.¹⁹ Diodorus states that the tip of the spear which pierced Epaminondas’ chest at Mantinea (362BC) broke off after it had entered his body.²⁰ All of these passages suggest that it was common for the hoplite spear to break during combat – most likely from impacts with a hard surface such as an opponent’s shield or armour, and that the force of these impacts would be enough to break the head off the weapon if resistance to penetration was high enough. Something similar is likely to have happened to the phalangite sarissa as well.

Unfortunately, such passages as those of Herodotus, Xenophon, Euripides and Diodorus do not detail what caused the spear head to break off. A spear, for example, may have splintered at a weak point that had developed in its wooden shaft. Alternatively, a rivet or adhesive that was holding the head in place may have weakened or broken through the actions of combat and this may have resulted in the head simply falling off. It has also been estimated that if the head of a spear was held in place (such as having it penetrate a shield or body), the application of a lateral force of 119ft lbs (160.7j) would be enough to wrench the shaft from the socket.²¹ Due to the length of the sarissa, and the leverage that this length and the rearward placement of the grip on the weapon creates, it would be very easy to generate this much force. Another possibility was that the spearhead itself may have broken at a weak point where the blade of the head meets the socket.²² Finds from Olympia contain several spearheads from the Classical Period broken in just such a manner suggesting that this was a common weak point in the design of many spearheads and may be what both Herodotus and Euripides are referring to.²³

If all of these conditions of hoplite warfare, spears breaking due to severing by an enemy or through the rigours of combat, are also taken as elements of phalangite warfare (and there is no reason to assume that they are not), then it seems that, under certain battlefield conditions, the phalangite’s sarissa could actually break, or be broken, in his hands. However, this does not automatically mean that, if this did occur, that the phalangite would resort to the use of the butt on the broken sarissa as a secondary weapon and an examination of how such a broken weapon could be used (or not) indicates the unlikelihood of it being used offensively.

Could a broken sarissa be of any use in the massed combat of the phalanx? Could the butt of a broken weapon actually be brought to bear against a target? And could it have reached that target? Due to the varied nature of how a sarissa could break or be broken, the remaining section of weapon could be of any length. Weapons that merely lost their head, either through it breaking or falling off, would lose between 20 and 30cm of their overall length. If the sarissa fractured at a weak point in the wood, the amount of remaining weapon would be dictated by the location of that weak point anywhere along the shaft. In the case of the spears hacked through by an opponent, the length of the weapon may have been reduced by as much as a metre.

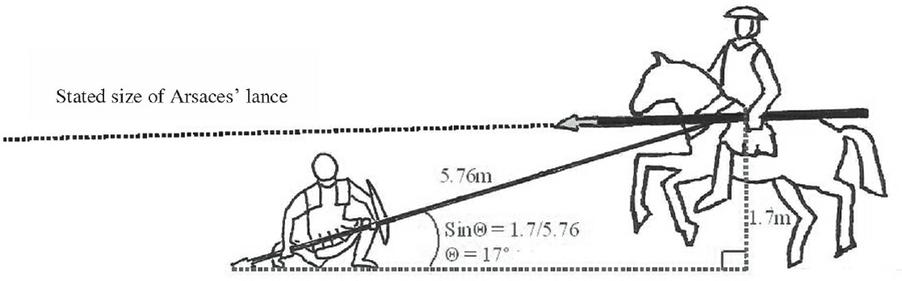

For the pikes from the time of Alexander the Great with an overall length of 12 cubits (576cm), if they were hacked through by an opponent, the remaining weapon would have been approximately 476cm in length, 45cm of which would be the length of the butt itself. The removal of the head and around 70cm of shaft dramatically alters the balance of the remaining section of the weapon which would weigh in the vicinity of 4.5kg. If this broken weapon was turned around so that the butt acts as the impacting tip, the sheer length and mass of the shaft (acting to offset the weight of the butt) relocate the point of balance to 204cm behind the new forward tip of the weapon, a shift of 108cm away from the butt and just behind the mid-point of the weapon (Fig. 20).²⁴

Fig. 20: Calculation of the point of balance of a broken sarissa.

A weapon such as this, if it were wielded correctly with the left hand placed at the point of balance and the right hand positioned about 96cm further back, leaves over 1.7m of shaft projecting behind the bearer and only 2m to their front. Due to the large weight of the butt which would now be acting as the forward tip, it is almost impossible to wield a broken sarissa by gripping it further rearward than its new point of balance as the muscular stresses caused by the pressure required to keep the weapon level for a protracted period of time become too great.²⁵ Thus even a sarissa which had only lost its head, leaving an extra metre of shaft attached to the broken weapon, could not be held much further back than 2.5m from the tip of the butt.

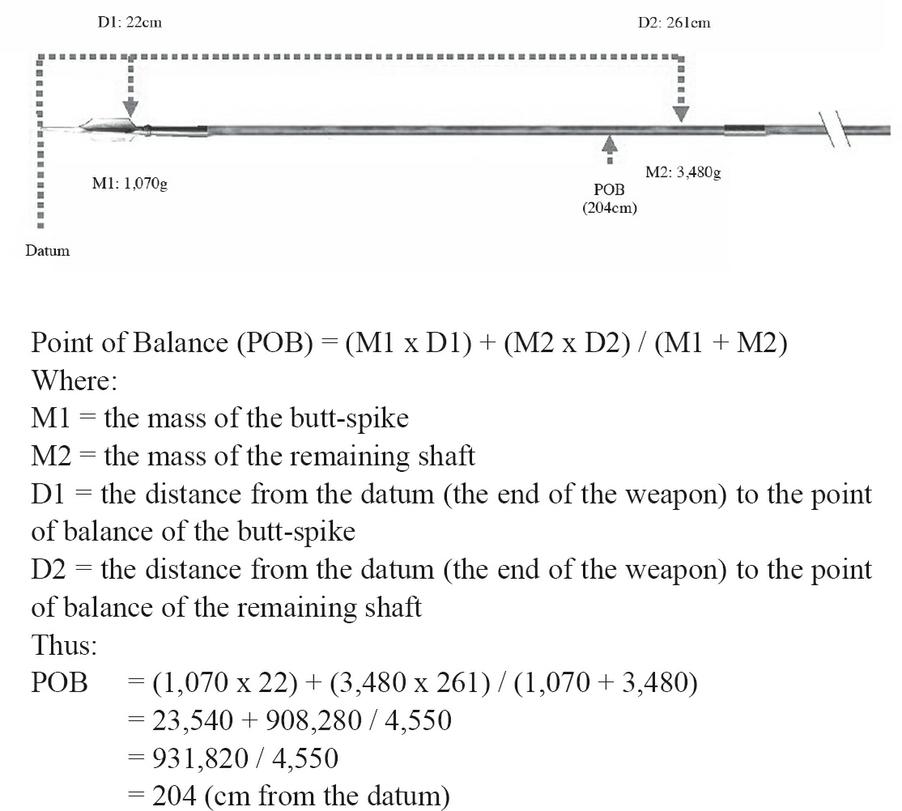

It is almost impossible to reposition a weapon balanced in this way so that the butt can be used offensively when deployed in a phalanx. Regardless of where and how the sarissa breaks, the butt will be pointing towards the rear when the weapon fractures. The leading left hand, holding the sarissa at its correct point of balance, will be approximately 96cm forward of the butt. In order for the butt to be brought to bear against a target as a secondary weapon, the broken sarissa has to be spun around 180° and the grip repositioned by more than a metre. It would require a considerable amount of room for a phalangite to rotate a broken weapon 476cm in length or longer, without it becoming entangled with his own equipment or that of the other members of the phalanx. This is much more space than is available in even the most open order described by the ancient military writers.

Nor could the broken weapon be raised vertically (so that the broken end of the shaft pointed up and the butt was towards the ground) and then reverse the grip on the weapon and feed the butt forward into a combative position. To do so would require a large amount of the shaft to be angled backwards as the weapon is fed forward – again risking entanglement with the weapons of those in the rearward ranks, especially those which were angled forward over the heads of those in front. In the confines of a phalanx, regardless of whether they were hard pressed up against an enemy or not, there is simply no way in which the phalangite would be able to bring the butt of a broken weapon to bear against a target.

Furthermore, even if a phalangite was able to somehow reposition his shattered weapon so that he could strike forward with the butt, a broken weapon 476cm in length and gripped at its new point of balance 204cm behind the tip, affords a combat range of only 240cm and an overall effective range of only 252cm when used in an intermediate-order formation. This is less than half the reach of an intact sarissa used in the same order (effective reach 540cm). Thus if the phalanx was facing an opponent with a short reach weapon (e.g. Romans or Persians), the opposing formation would most likely be held back at the distance that the fully intact pikes of the phalanx extend forward of the line (on a 12 cubit (576cm) weapon this equates to a distance of 10 cubits or 480cm). Consequently, even if a phalangite within this formation could thrust a broken weapon forward, if both he and his opponent maintained their positions in their respective formations, the reduced reach of the broken weapon would mean that any strike made by the phalangite would fall short of its target by more than a metre. If the phalangite with the broken weapon was facing another phalangite, who may have the tip of his weapon pressed into his shield, thus preventing any movement of the left arm, the phalangite with the broken sarissa would not be able to thrust at all and would only have a reach equivalent to the amount of broken weapon that projected (204cm) ahead of him. Thus, if those on either side of him were still using intact pikes, and engaging an enemy at a distance of nearly five metres, a phalangite would not be able to reach an opponent with a broken weapon unless he stepped forward of the ranks and advanced into the ‘no man’s land’ between the two formations in order to engage. It seems unlikely that a phalangite would have advanced forward of his position in the phalanx to attack, as the very basis of phalanx-based combat was the maintenance of the formation, nor could he advance further forward in order to engage if an opponent’s pike was pressed into his shield.

Additionally, due to the 1.7m of broken shaft projecting behind him, a phalangite wielding a broken sarissa at its correct point of balance could not maintain an intermediate order spacing of 96cm between himself and the man behind him. The jagged end of the shaft also makes wielding a broken weapon in any formation both dangerous to surrounding phalangites and liable to entanglement with the equipment of other members of the formation (Fig. 21).

The rearward projection of so much of the broken shaft, and the physical inability to wield a shafted weapon with a heavy tip any further back, clearly indicates that a sarissa broken in such a manner could not have been used as an improvised weapon in the massed confines of the pike-phalanx. Consequently, any suggestion that the butt of a broken sarissa was used as a secondary weapon in the press of battle can only be regarded as completely untenable.

At such a distance from an opponent, a broken sarissa could only have been used in a defensive capacity to fend off attacks. The sarissa could still be held in place with the jagged end of the shaft projecting towards an opponent simply to keep him at bay. In doing so the sarissa does not have to be rotated and only a minor adjustment to where it is held made to compensate for the altered point of balance. If the wooden shaft of the spear had fractured too close to the butt to make the weapon of any use in this capacity, it would have simply been abandoned on the field – much like Alexander’s broken lance was. In this case a sword may have been drawn if the phalangite possessed one, although he would be unlikely to reach his opponent with this weapon either, or be able to even swing it without becoming entangled in the weapons of the other ranks unless he simply slashed downward across his shield or just thrusted directly ahead. It is more likely that a phalangite in this situation, especially if facing another phalangite, simply stood his ground and absorbed or parried any opponent’s attacks with his shield.

Fig. 21: The rearward projection of the shattered shaft when a broken sarissa is held at its altered point of balance and the reduced effective range of a broken sarissa (dotted line = if the weapon can be thrust forward; solid line = if the left arm is pinned in place).

In a confused melee, such as when a formation began to break up and/or rout, either of which may not have conformed to the intervals of the phalanx, any phalangite who did not possess a sword would have clearly used any weapon available to defend himself. Under these conditions it is possible that the butt of a broken sarissa could have been repositioned and used in an offensive manner. Similarly, the jagged end of the shaft could be jabbed, thrust or swung at an opponent, although it is unlikely that it would penetrate a shield or armour and could only have been used against unprotected areas of an opponent’s body in the same way that Diodorus describes Alexander’s actions at the Granicus. In such a frenzied environment anything is possible. However, these would have been acts of desperation rather than a standard battlefield use of the butt as a secondary weapon.

Another thing to consider is whether or not the spike of the butt of a sarissa would be offensively useful, even if the broken weapon could be repositioned so that it could be used in such a manner. During the testing of the penetrative abilities of the sarissa, participants used the butt on the replica sarissa against a sheet of 1mm thick corrugated iron. The weapon used was not broken and was held in a location slightly forward of centre towards the front end of the weapon. This was not the exact location of the weapon’s point of balance, but accurately simulated a phalangite whose weapon had broken attempting to use as much of the length and reach of the remaining sarissa as possible.

Due to the amount of energy that can be delivered with a thrust made with the sarissa from the low position (see The Penetration Power of the Sarissa from page 225), it was found that even the spike of the butt, which has a much larger impacting point than the head does, could penetrate the 1mm thick plate with only minimal effort. The wing-like flanges of the butt prevented it from penetrating too far, however the butt still penetrated up to almost the entire length of the spike – an average depth of penetration of approximately 10cm. This would have easily resulted in severe injury to anyone who received such an impact regardless of whether the area of the body hit was protected by armour or not. This penetration occurred regardless of where on the corrugations of the plate the butt impacted, thus showing that even the curvature of any armour that a recipient of such an attack might be wearing was insufficient to resist this kind of impact. It is further likely that such impacts would cause considerable damage to shields and would penetrate the linothorax. This suggests that, if it was ever employed as a secondary weapon, the butt of the sarissa would have been rather effective as an offensive weapon. However, the difficulty of repositioning a broken weapon within the confines of the pike-phalanx so that the butt could be used in such a manner suggests that it was never designed to be used in such a way.

All of these considerations show that there is no basis of support for theories which propose a use for the butt of the sarissa as an alternative weapon. If the phalangite’s pike broke during combat there would be little reason to retain the broken section except for the possible eventuality that the combat may develop into a situation where a secondary weapon was necessary. If that did not occur, the butt on the end of a broken sarissa could not have been brought to bear against a target in the confines of the phalanx, and could not have reached a target even if it was done so. In these instances, any weapon which broke would most likely have been kept in place and used to fend off an attacker while the battle was continued by those whose pikes were still intact. It is the combination of these factors which make it unlikely that the butt was ever used as, or even designed to be, a secondary weapon.

Another proposed offensive use of the butt of the sarissa is for the dispatching of a fallen opponent who lay prone at a phalangite’s feet.²⁶ Similar to the use of the butt as a secondary weapon, the use of the butt to attack downwards at an opponent on the ground seems to have been extrapolated from a suggested use of the sauroter affixed to the hoplite doru – a theory that has no supporting evidence.²⁷ However, while the sauroter of the hoplite spear could not be used in this manner, was it possible for the butt of the sarissa?

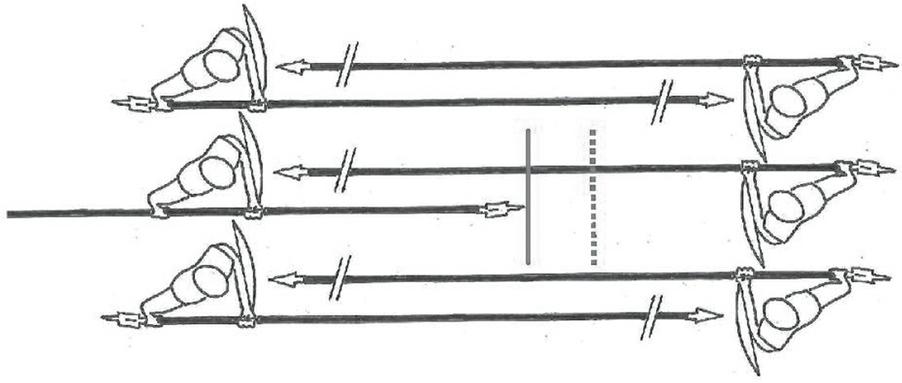

In order to effect such a strike, the sarissa has to be moved into a vertical position from where the butt can be thrust downwards at the target. However, would conditions which allowed this to happen easily manifest themselves on the field of battle? There are no literary descriptions or artistic representations of the use of the butt of the sarissa in this manner and whether it could have been used in this way or not can only be determined by examining who, if anyone, was able to engage a prone opponent in this manner. If the phalanx was deployed sixteen ranks deep, and with the pikes of the first five ranks leveled for combat while the remainder were angled at a 45° angle over the heads of the men in front as per the descriptions of the phalanx found in Arrian, Aelian, Asclepiodotus and Polybius, then hardly anyone within the formation would be in a position where they could easily use the butt of their weapons against a prone opponent.

The phalangite in the front rank, for example, may have had the tip of this sarissa pressed against the shield of his opponent – as the Macedonians are described as doing at Pydna in 168BC.²⁸ For an opponent to appear prone at the phalangite’s feet the phalanx must be advancing while the enemy is also moving under one of two possible scenarios: either the enemy formation is withdrawing – marching slowly backward, but still facing the enemy, in order to maintain the integrity of their line, or the enemy is simply in panicked flight – in which case the phalangite may not have the tip of his sarissa pressed against an opponent.

If the phalangite of the front rank was still engaged, he would be unlikely to raise his weapon to engage a prone enemy with the butt of the sarissa as this would provide the opponent he was facing with a momentary reprieve and an opportunity to move in on the phalangite. Due to the way that the sarissae of the first five ranks are serried and stepped back from each other by a distance of 2 cubits (96cm) per rank due to the size of the interval that each man occupies, an advancing opponent would most likely not be able to move forward any more than about a metre before the tip of the weapon held by the man in the second rank was thrust against his shield. However, once this had happened, even if the man in the first rank had used his butt to engage a prone opponent, he would now no longer be able to redeploy his weapon as the distance between him and the opponent was now less than the length of the weapon he was carrying.

Furthermore, it would be difficult for any member of the first rank to raise their sarissa vertically without the weapon becoming entangled in those held by the rear ranks that were angled over his head. The whole purpose of having the rear ranks deploy their pikes at this angle was to help shield the forward ranks from missile fire.²⁹ Thus it can be assumed that these weapons were positioned above the men of the front five ranks in order to provide such protection. However, this protection would then greatly limit the ability for the members of these forward ranks to use their own pikes in any manner other than having them pointed directly at an enemy or similarly angled upwards at 45°.

Similar problems would be encountered by those in ranks two to five, who would also have their pikes leveled for combat. Indeed, those in ranks four or five would experience even more difficulties in raising their pikes as those that were held at an angle over their heads by the more rearward ranks would, due to the angle, be even closer to them – in the case of those in rank five the angled pikes would literally be just above their heads and would greatly hinder any attempt to raise a pike vertically. Furthermore, as each man in the formation occupies a space of 2 cubits (96cm), and those of the rear ranks have their shields pressed hard against the butt of the sarissa held by the man in front, this greatly limits the amount of room available to members of the second to fifth ranks to raise their pike vertically and then bring it down at an opponent laying prone at their feet. It would be questionable, due to the press of men around them on all sides, whether members of these ranks would even see such a target until they were literally right on top of it. Finally, it must also be considered whether an advancing formation would simply step over a prone, but still living, opponent so that members of a more rearward rank could dispatch them with the butt of their weapon. This would run tremendous risk that that opponent would be able to use their position, and a short reach weapon like a sword or dagger, to attack the advancing phalangites from below (stabbing at the legs or groin, for example) as they advanced over them and while their pikes, extending both above and beyond them, were unable to be brought to bear.

This also makes it unlikely that the members of ranks six to fifteen, who were holding their pikes angled over the heads of those in the front ranks, were the ones who could have engaged a prone opponent with the butt of their sarissae. While pikes held in this angled position are easier to raise vertically, they would still run the risk of becoming entangled with all of the other angled pikes of the formation, and it is further unlikely that an advancing formation would allow the men of at least the first five ranks to pass over a prone opponent only to allow the man in rank six (or even further back) to engage.

The only member of the phalanx who was in any position to engage a prone opponent with the butt of his weapon was the file-closing ouragos in rank sixteen. Due to the lack of further pikes being positioned at an angle behind him, the man in the rear rank would encounter no impediment to raising his weapon vertically and then using the butt to try and dispatch an enemy lying at his feet. However, while such a move for the ouragos is physically possible the question still remains: would fifteen ranks of men simply walk over a danger such as a live opponent so that the man in the rear rank could then dispatch him? This seems highly unlikely.

Thrusts brought directly downwards can generate a great deal of force. Clearly this style of attack could do considerable damage against an unprotected area of the human body, enough to easily kill or at least severely injure, and could penetrate armour and damage shields. However, the inability of the members of most ranks of the phalanx to even move their pikes into a position where a downward attack with the butt could be made, indicates that any prone opponent had to be dispatched by another means.

In the standard deployment of the pike-phalanx, it can be assumed with some certainty that any enemy combatant who was knocked down during the course of a battle would have been done so by an attack delivered by the men in the front rank of the phalanx. If the opponent was knocked down but not killed, this would then make them one of the prone targets who would then be later dispatched with the butt of the sarissa in some modern theories. Yet, there would be no need for the target to be killed in such a way. If the phalanx was slowly advancing, the man in the front rank would not continue to engage an opponent who had fallen as the opponent would move inside the effective range and/or combat range of the front rank phalangite as the formation advanced. However, as the members of the more rearward ranks also had their pikes leveled, and staggered by 96cm intervals, the prone target could easily be dispatched by one of the members of ranks two to five simply by having them dip the tip of their sarissa downward to engage a target who was on the ground but still ahead of the formation and allow the slow momentum of the phalanx’s advance help impale him or drive him back.

Due to the serried nature of the weapons held by the first five ranks, if an opponent was knocked down and remained more or less where he fell, he could easily be dispatched by members of ranks two or three as the line rolled forward. If the opponent was knocked down, but crawled forward (i.e. towards the advancing phalanx in an attempt to get under their pikes) then the crawling enemy could be easily taken out by members of ranks four or five. This was the whole essence of having a serried line of pikes; those from the more rearward ranks could still engage an opponent who got ‘inside’ the weapons held by the forward ranks – regardless of whether that opponent was prone or standing. Thus the different ranks served different purposes in a combat situation: rank one to directly engage the enemy, or keep him at bay or push him back with the pike; ranks two to five to cover the gap between the files and to engage prone or standing opponents who got within the reach of the front rank; and ranks six to sixteen to provide protection for the formation against enemy missiles. Importantly, at no point is any member of the phalanx required to engage a prone opponent with the butt of their sarissa. It is possible that, if the file-closing ouragos did encounter a prone opponent as the phalanx moved forward who, although having already been engaged by members of at least two different ranks, was still alive, he could deliver a coup de grace with the butt of his pike to simply finish him off. However, there is no reference to this ever occurring and the chances of someone surviving being stabbed several times with pikes and then being trampled over by a whole file of phalangites would have been slim.

Modern theories suggesting the offensive use of the sarissa butt are not supportable. The mechanics behind the use of the butt as a weapon conflict with all models and accounts of phalangite combat. A broken weapon could not be reoriented to use the butt as the point of impact in most cases. A broken sarissa, with a heavy butt still attached, may have been used to parry blows under the most dire of close combat conditions, but is unlikely to have been consciously regarded as an alternative weapon. Similarly, there is little evidence to support claims that the spike could be used to finish off a fallen adversary. It can therefore be concluded that the butt was only designed to function in its other capacities: to protect the end of the shaft from the elements; to balance the sarissa correctly; to allow the pike to be thrust upright into the ground and to add weight to the mass of the weapon. All of these characteristics would play a part in how the sarissa was used in the massed formation of the pike-phalanx.