Understanding the Basics of Trump Suits

In Bridge, the bidding often designates a suit as the trump suit. If the final contract has a suit associated with it — 4♠, 3♥, 2♦, or even 1♣, for example — that suit becomes the trump suit for the entire hand. (See Book 5, Chapter 5 for a primer on bidding.)

Often, in Bridge books such as this one, a single card like the four of spades is written ♠4 because it saves space. Similarly, a bid made by any player, such as four spades, is written 4♠ (notice the difference). A final contract is written the same way as a bid, so a contract of three diamonds usually appears as 3♦.

Often, in Bridge books such as this one, a single card like the four of spades is written ♠4 because it saves space. Similarly, a bid made by any player, such as four spades, is written 4♠ (notice the difference). A final contract is written the same way as a bid, so a contract of three diamonds usually appears as 3♦.

When a suit becomes the trump suit, any card in that trump suit potentially has special powers; any card in the trump suit can win a trick over any card of another suit. For example, suppose that spades is the trump suit and West leads with the ♥A. You can still win the trick with the ♠2 if you have no hearts in your hand.

Because trump suits have so much power, naturally everyone at the table wants to have a say in determining the trump suit. Because Bridge is a partnership game, your partnership determines which suit is the best trump suit for your side or whether there shouldn’t be a trump suit at all.

In the following sections, we show you the glory (and potential danger) of trump suits.

Finding out when trumping saves the day

You can easily see the advantage of playing with a trump suit. When the bidding designates a trump suit, you may well be in a position to neutralize your opponents’ long, strong suits quite easily. After either you or your partner is void (has no cards left) in the suit that your opponents lead, you can play any of your cards in the trump suit and take the trick. This little maneuver is called trumping your opponents’ trick (which your opponents really hate). Your lowly deuce of trumps beats even an ace in another suit.

In contrast, if you play a hand at a notrump contract, the highest card played in the suit led always takes the trick (see Book 5, Chapters 3 for more information on playing at notrump). If an opponent with the lead has a suit headed by all winning cards, that opponent can wind up killing you by playing all those winning cards — be it four, five, six, or seven — taking one trick after another as you watch helplessly. Such is the beauty and the horror of playing a hand at notrump. You see the beauty when your side is peeling off the tricks; you experience the horror when your opponents start peeling them off one by one — sometimes slowly, to torture you.

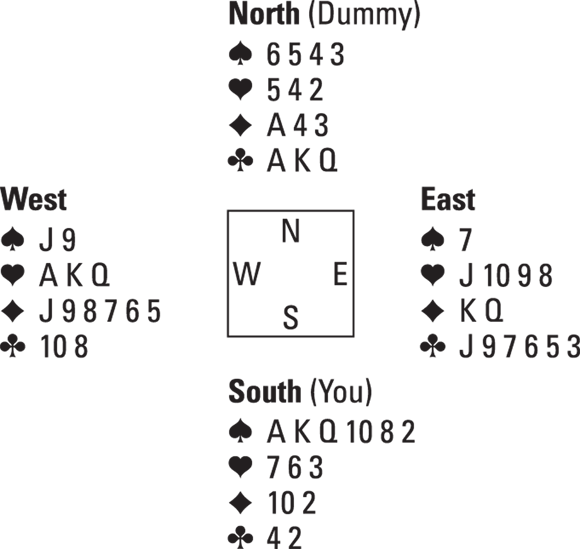

The hand in Figure 4-1 shows you the power of playing in a trump suit.

On this hand, suppose that you need nine tricks to make your contract of 3NT (NT stands for notrump). Between your hand and the dummy, you can count 11 sure tricks: five spades (after the ♠AK are played and both opponents follow, the opponents have no more spades, so ♠QJ2 are all sure tricks), three diamonds, and three clubs. (Book 5, Chapter 2 has details on how to count sure tricks.)

If you play the hand shown in Figure 4-1 in notrump, all your sure tricks won’t help you if your opponents have the lead and can race off winning tricks in a suit where you’re weak in both hands, such as hearts. Playing in notrump, West can use the opening lead to win the first five heart tricks by leading the ♥AKQJ2, in that order. To put it mildly, this start isn’t healthy. You need to take nine tricks, meaning you can afford to lose only four, and you’ve already lost the first five.

On this hand, you and your partner need to communicate accurately during the bidding to discover which suit (hearts, in this case) is woefully weak in both hands. When you both are weak in the same suit, you need to end the bidding in a trump suit so you can stop the bleeding by eventually trumping if the opponents stubbornly persist in leading your weak suit.

In Figure 4-1, assume that during the bidding, spades becomes the trump suit and you need ten tricks to fulfill your contract. When West begins with ♥AKQ, you can trump the third heart with your ♠2 and take the trick. (You must follow suit if you can, so you can’t trump either of your opponents’ first two hearts.) Instead of losing five heart tricks, you lose only two.

Seeing how their trumps can ruin your whole day

Bear in mind that your opponents, the defenders, can also use their trump cards effectively; if they hold no cards in the suit (called a void) that you or the dummy leads, they can trump one of your tricks. Misery.

Bear in mind that your opponents, the defenders, can also use their trump cards effectively; if they hold no cards in the suit (called a void) that you or the dummy leads, they can trump one of your tricks. Misery.

After you have the lead, you want to prevent your opponents from trumping your winning tricks. You don’t want your opponents to exercise the same strategy on you that you used on them! You need to get rid of their trumps before they can hurt you. This move is called drawing trumps, which we show you how to do in the following section.

Eliminating Your Opponents’ Trump Cards

If you can trump your opponents’ winning tricks when you don’t have any cards in the suit that they’re leading, it follows that your opponents can turn the tables and do the same to you. Instead of allowing your opponents to trump your sure tricks, play your higher trumps early on in the hand. Because your opponents must follow suit, you can remove their lower trumps before you take your sure tricks. If you can extract their trumps, you effectively remove their fangs. This extraction is called drawing or pulling trumps. Drawing trumps allows you to take your winning tricks in peace without fear of your opponents trumping them.

The dangers of taking sure tricks before drawing trumps

Send the children out of the room and see what happens if you try to take sure tricks before you draw trumps. For example, in Figure 4-1 (where spades are trump), after you trump the third round of hearts, if you lead the ♦2, West has to follow suit by playing the only diamond in his hand, the ♦8. You then play the ♦Q from the dummy, East plays a low (meaning lowest) diamond, the ♦3, and you take the trick. However, if you follow up by playing the ♦A, West has no more diamonds and can trump the ace with the ♠6 because the bidding has designated spades as the trump suit for this hand.

The same misfortune befalls you if, instead of playing diamonds, you try to take three club tricks. East can trump the third round of clubs with the lowly ♠4. Imagine your discomfort when you see your opponents trump your sure tricks. They, on the other hand, are thrilled over this turn of events.

You should usually try to draw trumps as soon as possible. Get your opponents’ pesky trump cards out of your hair. Then you can sit back and watch as your winning tricks come home safely to your trick pile.

You should usually try to draw trumps as soon as possible. Get your opponents’ pesky trump cards out of your hair. Then you can sit back and watch as your winning tricks come home safely to your trick pile.

The joys of drawing trumps first

To see how drawing trumps can work to your advantage, take a look at Figure 4-2, which shows only spades (the trump suit) from the hand in Figure 4-1. Remember, your goal is ten tricks.

Drawing trumps is just like playing any suit — you have to count the cards in the suit to know if you have successfully drawn all your opponents’ trump cards. For more about counting cards, see Book 5, Chapter 3.

Drawing trumps is just like playing any suit — you have to count the cards in the suit to know if you have successfully drawn all your opponents’ trump cards. For more about counting cards, see Book 5, Chapter 3.

In the hand shown in Figure 4-2, you and your partner start life with nine spades between you, leaving only four spades that your opponents can possibly hold. Suppose that you play the ♠A — both opponents must follow suit and play one of their spades. You win the trick, and you know that your opponents have only two spades left. Suppose that you continue with the ♠K, and both opponents follow. Now they have no spades left (no more trump cards). You have drawn trumps. See? That wasn’t so bad.

Refer to Figure 4-1 (where West begins with the ♥AKQ, and you trump the third heart with your ♠2). After you trump the third heart, you draw trumps by playing the ♠AK. You can then safely take your ♣AKQ and your ♦AKQ — you wind up losing only two heart tricks. You needed to take 10 tricks to fulfill your contract, and you in fact finished up with 11 tricks. Pretty good! Drawing trumps helped you make your contract.

Noticing How Trump Suits Can Be Divided

If you have eight or more cards in a suit between your hand and the dummy, particularly in a major suit (either hearts or spades), you try to make that suit your trump suit.

An eight-card fit (eight cards in a single suit between your hand and the dummy) gives you a safety net because you have many more trumps than your opponents: Your trumps outnumber theirs eight to five. Having more trumps than your opponents is always to your advantage. You may be able to survive a seven-card trump fit, but having an eight- or nine-card trump fit relieves tension. The more trumps you have, the more tricks you can generate and the less chance your opponents have of taking tricks with their trumps. You can never have too many trumps! The fewer trumps your opponents have, the easier it is for you to get rid of them.

In the following sections, we show you a variety of trump fits.

Scoring big with the 4-4 trump fit

During the bidding, you may discover that you have an eight-card fit divided 4-4 between the two hands. Try to make such a fit your trump suit. A 4-4 trump fit almost always produces at least one more trick in the play of the hand than it does at notrump.

During the bidding, you may discover that you have an eight-card fit divided 4-4 between the two hands. Try to make such a fit your trump suit. A 4-4 trump fit almost always produces at least one more trick in the play of the hand than it does at notrump.

At a notrump contract, the 4-4 spade fit in Figure 4-3 takes four tricks. At notrump, when you and your partner have four cards apiece in the same suit, four tricks is your max.

However, when spades is your trump suit, you can do better. In Figure 4-3, suppose that your opponents lead a suit that you don’t have, which allows you to trump their lead with the ♠3. By drawing trumps now, you can take four more spade tricks by playing the ♠A and the ♠K from your hand (high honors from the short side first) and then playing the ♠4 over to the ♠J and ♠Q from the dummy. You wind up taking a total of five spade tricks — the card you trumped plus four more high spades. (Flip to “Eliminating Your Opponents’ Trump Cards” earlier in this chapter for more on drawing trumps.)

A 4-4 trump fit is primo. You can get more for your money from this trump combination. Every so often you can take six (or more) trump tricks when you have a 4-4 trump fit, so keep your eyes open for one. They are magic.

A 4-4 trump fit is primo. You can get more for your money from this trump combination. Every so often you can take six (or more) trump tricks when you have a 4-4 trump fit, so keep your eyes open for one. They are magic.

Being aware of other eight-card trump fits

Eight-card trump fits can come in different guises. Consider the eight-card trump fits in Figure 4-4. The figure shows examples of a 5-3, a 6-2, and a 7-1 fit. Good bidding uncovers eight-card (or longer) fits, which makes for safe trump suits. There is joy in numbers.

Counting Losers and Extra Winners

When playing a hand at a trump contract, instead of counting sure tricks (discussed in Book 5, Chapter 2), a better strategy is to count how many losers you have. If you have too many losers to make your contract, you need to look in the dummy for extra winners (tricks) that you can use to dispose of some of your losers.

You may find this approach a rather negative way of playing a hand. But counting losers can have a very positive impact on your play at a trump contract. Your loser count tells you how many extra winners you need, if any. Extra winners are an indispensable security blanket to make your contract — extra winners help you get rid of losers.

You may find this approach a rather negative way of playing a hand. But counting losers can have a very positive impact on your play at a trump contract. Your loser count tells you how many extra winners you need, if any. Extra winners are an indispensable security blanket to make your contract — extra winners help you get rid of losers.

In the following sections, we define losers and extra winners and show you how to identify them. We also explain when to draw trumps before taking extra winners and when to take extra winners before drawing trumps.

Defining losers and extra winners

When playing a hand at a notrump contract, you count your sure tricks (as we describe in Book 5, Chapter 2); however, when you play a hand at a trump contract, you count losers and extra winners. Losers are tricks you know you have to lose. For example, if neither you nor your partner holds the ace in a suit, you know you have to lose at least one trick in that suit unless, of course, one of you is void (has no cards) in the suit. Extra winners may allow you to get rid of some of your losers. An extra winner is a winning trick in the dummy (North) on which you can discard a loser from your own hand (South).

Get ready for some good news: When counting losers, you have to count only the losers in the long hand, the hand that has more trumps. The declarer usually is the long trump hand, but not always.

For the time being, just accept that you don’t have to count losers in the dummy. Counting losers in one hand is bad enough; counting losers in the dummy is not only unnecessary but also confusing and downright depressing.

For the time being, just accept that you don’t have to count losers in the dummy. Counting losers in one hand is bad enough; counting losers in the dummy is not only unnecessary but also confusing and downright depressing.

Recognizing immediate and eventual losers

Losers come in two forms: immediate and eventual. Immediate losers are losers that your opponents can take when they have the lead. These losers have a special warning signal attached to them that reads, “Danger — Unexploded Bomb!” Immediate losers spell bad news.

Of course, eventual losers aren’t exactly a welcome occurrence, either. Your opponents can’t take your eventual losers right away because those losers are temporarily protected by a winning card in the suit that you or your partner holds. In other words, with eventual losers, your opponents can’t take their tricks right off the bat, which buys you time to get rid of those eventual losers. One of the best ways to get rid of eventual losers is to discard them on extra winners.

You help yourself by knowing which of your losers are eventual and which are immediate. Your game plan depends on your immediate loser count. See “Drawing trumps before taking extra winners” and “Taking extra winners before drawing trumps” later in this chapter for more about how to proceed after counting your immediate losers.

Because identifying eventual and immediate losers is so important, take a look at the spades in Figures 4-5, 4-6, and 4-7 to spot some losers. Assume in these figures that spades is a side suit (any suit that is not the trump suit) and hearts is your trump suit.

Figure 4-5 shows a suit with two eventual losers. In the hand in this figure, as long as you have the ♠A protecting your two other spades, your two spade losers are eventual. However, after your opponents lead a spade (which forces out your ace), your two remaining spades become immediate losers because they have no winning trick protecting them. Ouch.

In Figure 4-6, you have one eventual spade loser. With the spades in Figure 4-6, the dummy’s ♠AK protect two of your three spades — but your third spade is on its own as a loser after the ♠A and ♠K have been played.

In Figure 4-7, you have two immediate spade losers. Notice that you count two, not three, spade losers — you count losers only in the long trump hand (which presumably is your South hand). You don’t have to count losers in the dummy. Actually, when you are playing a 4-4 trump fit, no long hand exists, so assume the hand with the longer side suit (five or more cards) is the long hand. When neither hand has a long side suit, the hand with the stronger trumps is considered the long hand.

Identifying extra winners

Enough with losers already — counting them is sort of a downer. You can get rid of some of your losers by using extra winners. Extra winners come into play only after you (South) are void in the suit being played. Therefore, extra winners can exist only in a suit that’s unevenly divided between the two hands and are usually in the dummy. The stronger the extra winner suit (that is, the more high cards it has), the better.

Enough with losers already — counting them is sort of a downer. You can get rid of some of your losers by using extra winners. Extra winners come into play only after you (South) are void in the suit being played. Therefore, extra winners can exist only in a suit that’s unevenly divided between the two hands and are usually in the dummy. The stronger the extra winner suit (that is, the more high cards it has), the better.

Figure 4-8 shows you two extra winners in their natural habitat. The cards in this figure fill the bill for extra winners because spades is an unevenly divided suit, and the greater length is in the dummy. After you lead the ♠3 and play the ♠Q from the dummy, you’re void in spades. Now you can discard two losers from your hand when you lead the ♠A and the ♠K from the dummy. Therefore, you can count two extra winners in spades.

By contrast, the cards in Figure 4-9 look hopeful, but unfortunately, they can’t offer you any extra winners. They don’t fit the mold for extra winners because you have the same number of spades in each hand. No matter how strong a suit is, if you have the same number of cards in each hand, you can’t squeeze any extra winners out of the suit. You just have to follow suit each time. True, the ♠AKQ aren’t chopped liver; although this hand has no spade losers, it gives you no extra winners, either. Sorry!

The cards in Figure 4-10 contain no extra winners, either. The dummy’s ♠AK take care of your two losing spades, but you have nothing “extra” over there — no ♠Q, for example — on which you can discard one of your losers. In Figure 4-10, your ♠A and ♠K do an excellent job of covering your two spade losers, but no more. You can’t squeeze blood out of a turnip.

Drawing trumps before taking extra winners

After counting your immediate losers (see “Recognizing immediate and eventual losers” earlier in this chapter), if you still have enough tricks to make your contract, go ahead and draw trumps before taking extra winners. That way, you can make sure your opponents don’t swoop down on you with a trump card and spoil your party. Figure 4-11 illustrates this point by showing you a hand where spades is your trump suit. You need to take ten tricks to make your contract. West leads the ♥A.

Before playing a card from the dummy, count your losers one suit at a time, starting with the trump suit, the most important suit. You can’t make a plan for the hand until your opponents make the opening lead because you can’t see the dummy until the opening lead is made. But as soon as the dummy comes down, try to curb your understandable eagerness to play a card from the dummy and first do a little loser and/or extra winner counting in each suit instead:

Before playing a card from the dummy, count your losers one suit at a time, starting with the trump suit, the most important suit. You can’t make a plan for the hand until your opponents make the opening lead because you can’t see the dummy until the opening lead is made. But as soon as the dummy comes down, try to curb your understandable eagerness to play a card from the dummy and first do a little loser and/or extra winner counting in each suit instead:

- Spades: In your trump suit (spades), you’re well heeled. You have ten spades between the two hands, including the ♠AKQ. Because your opponents have only three spades, you should have no trouble removing their spades. A suit with no losers is called a solid suit. You have a solid spade suit — you can never have too many solid suits.

- Hearts: In hearts, however, you have trouble — big trouble. In this case, your own hand has three heart losers. But before you count three losers, check to see whether the dummy has any high cards in hearts to neutralize any of your losers. In this case, your partner doesn’t come through for you at all, having only three baby hearts. You have three heart losers, and they’re immediate losers.

- Diamonds: In diamonds, you have two losers, but this time your partner does go to bat for you with the ♦A as a winner. The ♦A negates one of your diamond losers, but you still have to count one eventual diamond loser.

- Clubs: In clubs, you have two losers, but in this suit your partner really does come through. Not only does your partner take care of your two losers with the ♣AK, but your partner also has an extra winner, the ♣Q. Count one extra winner in clubs.

Your mental score card for this hand reads as follows:

- Spades: A solid suit, no losers

- Hearts: Three losers (the three cards in your hand)

- Diamonds: One loser, because your partner covers one of your losers with the ace

- Clubs: One extra winner

Next, you determine how many losers you can lose and still make your contract. In this case, you need to take ten tricks, which means that you can afford to lose three tricks. (Remember, each hand has 13 tricks up for grabs.)

If you have more losers than you can afford, you need to figure out how to get rid of those pesky deadbeats. One way to get rid of losers is by using extra winners — and you just happen to have an extra winner in clubs.

If you have more losers than you can afford, you need to figure out how to get rid of those pesky deadbeats. One way to get rid of losers is by using extra winners — and you just happen to have an extra winner in clubs.

Follow the play: West starts out by leading the ♥AKQ, taking the first three tricks. You can do absolutely nothing about losing these heart tricks — which is why you call them immediate losers (tricks that your opponents can take whenever they want). Immediate losers are the pits, especially if they lead that suit.

After taking the first three heart tricks, West decides to shift to a low diamond, which establishes an immediate winner for your opponents in diamonds and an immediate loser for you in diamonds when the ♦A is played from dummy. You may be strongly tempted to get rid of that loser immediately on the dummy’s clubs — just looking at it may be making you nervous. Don’t do it. Draw trumps first. If you play the ♣AKQ from the dummy before you draw trumps, West will trump the third club, and down you go in a contract you should make.

You need to draw trumps first and then play the ♣AKQ. West won’t be able to trump any of your good tricks, nor will East — they won’t have any trumps left. You wind up losing only three heart tricks — and making your contract!

The most favorable sequence of plays, after losing the first three heart tricks and winning the ♦A, is as follows:

- Play the ♠AK, removing all your opponents’ trumps.

- Play the ♣AKQ and throw that diamond loser away.

- Sit back and take the rest of the tricks now that you have only trumps left.

Any time you can draw trump before taking your extra winners, do it.

Any time you can draw trump before taking your extra winners, do it.

Taking extra winners before drawing trumps

Sometimes your trump suit has an immediate loser. When you have more immediate losers in a side suit than your contract can afford but you also have an extra winner, you must use that extra winner immediately before you give up the lead in the trump suit (or in any other suit, for that matter). If you don’t, your opponents will mow you down by taking their tricks while you still hold too many immediate losers. Of course, if you can draw trumps without giving up the lead, do that first and then take your extra winner as in Figure 4-11.

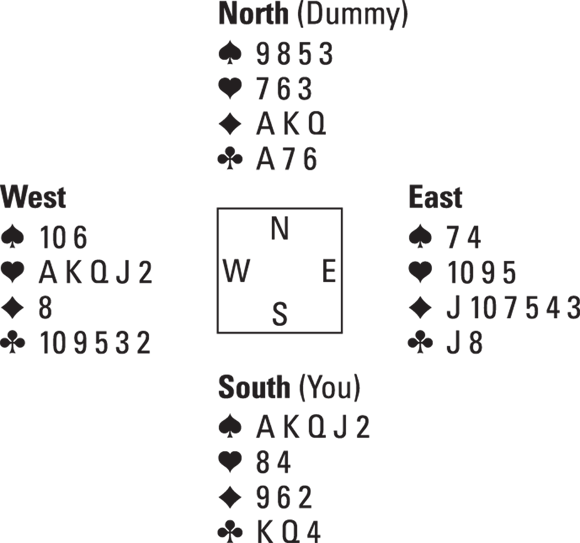

Figure 4-12 shows you the importance of taking your extra winners before drawing trumps. In this hand, your losers are immediate — if your opponents get the lead, you can pack up and go home.

In the hand in Figure 4-12, your contract is for ten tricks, with spades as the trump suit. West leads the ♦K, trying to establish diamond tricks after the ♦A is played. After dummy’s ♦A has been played, West’s ♦Q and ♦J are promoted to sure winners on subsequent tricks.

After you count your losers, you tally up the following losers and extra winners:

- Spades: One immediate loser — the ♠A

- Hearts: One extra winner — the ♥Q

- Diamonds: Two losers, which are immediate after you play the ♦A

- Clubs: One immediate loser — the ♣A

You win the opening lead with the ♦A. Suppose you lead a low spade from dummy at trick two and play the ♠K from your hand, intending to draw trumps — usually a good idea. (See “Eliminating Your Opponents’ Trump Cards” earlier in this chapter for more information on drawing trumps.)

However, West wins the trick with the ♠A and takes the ♦QJ, and East still gets a trick with the ♣A. You lose four tricks. What happened? You went down in your contract while your extra winner, the ♥Q, was still sitting over there in the dummy, gathering dust. You never got to use your extra winner in hearts because you drew trumps too quickly. When you led a spade at the second trick, you had four losers, all immediate. And sure enough, your opponents took all four of them.

If you want to make your contract, you need to play that extra heart winner before you draw trumps. You can’t afford to give up the lead just yet. The winning play goes something like this:

- You take the ♦A at trick one, followed by the ♥AKQ at tricks two, three, and four.

-

On the third heart, you discard one of your diamond losers.

This play reduces your immediate loser count from an unwieldy four to a workable three.

-

Now you can afford to lead a trump and give up the lead.

After all, you do want to draw trumps sooner or later.

If you play the hand properly, you wind up losing one spade, one club, and one diamond — and you make your contract of ten tricks. Congratulations.

You may think that playing the ♥AKQ before you draw trumps is dangerous, but you have no choice. You have to get rid of one of your immediate diamond losers before giving up the lead if you want to make your contract. Otherwise, you’re giving up the ship without a fight.

You may think that playing the ♥AKQ before you draw trumps is dangerous, but you have no choice. You have to get rid of one of your immediate diamond losers before giving up the lead if you want to make your contract. Otherwise, you’re giving up the ship without a fight.

Often, in Bridge books such as this one, a single card like the four of spades is written ♠4 because it saves space. Similarly, a bid made by any player, such as four spades, is written 4♠ (notice the difference). A final contract is written the same way as a bid, so a contract of three diamonds usually appears as 3♦.

Often, in Bridge books such as this one, a single card like the four of spades is written ♠4 because it saves space. Similarly, a bid made by any player, such as four spades, is written 4♠ (notice the difference). A final contract is written the same way as a bid, so a contract of three diamonds usually appears as 3♦. Bear in mind that your opponents, the defenders, can also use their trump cards effectively; if they hold no cards in the suit (called a void) that you or the dummy leads, they can trump one of your tricks. Misery.

Bear in mind that your opponents, the defenders, can also use their trump cards effectively; if they hold no cards in the suit (called a void) that you or the dummy leads, they can trump one of your tricks. Misery.

Drawing trumps is just like playing any suit — you have to count the cards in the suit to know if you have successfully drawn all your opponents’ trump cards. For more about counting cards, see Book 5,

Drawing trumps is just like playing any suit — you have to count the cards in the suit to know if you have successfully drawn all your opponents’ trump cards. For more about counting cards, see Book 5,