2The Goddess in Colonial and Postcolonial History

The celebration of the Śākta Pūjās to Durgā, Jagaddhātrī, and Kālī certainly predates the arrival of European merchant-traders and colonialists in Bengal, but not by a great deal. One could in fact argue that it was the presence of the British that provided the initial impetus for the festivals’ development into the characteristic forms we see today, with goddesses worshiped in temporary temples, or pandals, placed to the side of public urban thoroughfares. This chapter covers the entire period of British rule in Bengal—from the mid-eighteenth century until 1947 and beyond—illustrating the history of English–Indian relations in miniature, through the lens of the Pūjās. How did the various, and changing, British attitudes toward Indians, Bengalis, Hindus, Muslims, festivals, rulership, and intercommunity mixing affect their perspectives on the Pūjās? And how did Bengali choices regarding Pūjā sponsorship and organization reflect their views of British suzerainty in Bengal? As is indicated in the wealth of information to be found in old newspapers, English and Bengali, from the 1780s until Independence and after, attitudes to the Pūjās, whether by Europeans or Bengalis, varied considerably, not only over time but also across constituency.1 Newspapers reflecting the opinions of East India Company officials tended to differ from those of the mercantile, banking, and “pro-native” Englishmen, all of whom differed from each other and from Christian missionary publications. Likewise, Indian-owned and -run papers, printed sometimes in Bengali and sometimes in English, expressed a multitude of opinions: those of the Brāhmo Samāj; the orthodox, anti-reforming pandits; and nationalists, whether “Moderate” or “Extreme.” That there never was one monolithic “British” perspective on India, or one “Hindu” response to it, is amply demonstrated by a glance at the developmental history of the Pūjās. There is one constant, however, and that is the Janus-faced nature of the Pūjā symbol, which always looks both ways, reflecting to its British and Indian interpreters what is occurring in the public, political, and interethnic spheres.

Early Interactions: The Late Eighteenth Century to 1858

Uncontested Patronage, Unabashed Delight

On tables heaped, reveal their varied charms,

Porcelain from France and England glittering o’er …

And from the ceilings droop stupendous lustres,

And girandoles and chandeliers, that vie

With wall shades stuck around in sparkling clusters,

Which Doorga, often, for her annual nautches musters.2

A survey of Calcutta newspaper reports on Durgā Pūjā confirms the rough periodizations regarding the shifting relations between Indians and Europeans given by scholars such as David Kopf and Sumanta Banerjee3: in general, from the time of Plassey in 1757 until the coming of Lord William Bentinck (1828–1835) as the East India Company’s governor-general, British policy toward Indian religious and social customs was fairly relaxed. This period also coincided with the liberal, acculturative intellectual programs of Warren Hastings (1772–1784) and Marquess Richard Wellesley (1798–1805), who tried to encourage British civil servants to form friendships with Bengalis and to learn their languages and culture. Indeed, early Europeans were primarily military and mercantile in orientation, and were not themselves terribly religious; in fact, it was crucial to their trading and ruling concerns that matters of religion not jeopardize their relationships with the Hindus and Muslims in their territories. Accordingly, they resorted to various means to conciliate those with whom they traded and whom they ruled, among which was a readiness to patronize Hindu and Muslim religions. For instance, they took over the organization of Hindu temples, collected pilgrim taxes for their running, visited Hindu places of pilgrimage, and occasionally even worshiped Hindu deities. Such policies of appeasement are reflected in generally positive attitudes toward the Pūjās, characterized in an 1831 news item describing the visit at Durgā Pūjā of the vice president of the Company to the house of Nabakṛṣṇa Deb and his two grandsons at Shovabazar. “From these marks of favor conferred on the Rajas year after year by the Rulers … nothing is more clear than that the Government endears itself to his Britannic Majesty’s Hindoo Subjects.”4

As we have seen in chapter 1, the zamindars of this period welcomed—even fought with each other over—British visitations to their houses during the festivals. Pūjā hosts whose open invitations to their homes recur repeatedly in the British newspapers in these early decades include Gobindarām Mitra of Kumartuli; Shovabazar’s Nabakṛṣṇa Deb (as well as his sons Gopimohan and Rājkṛṣṇa and grandsons Rādhākānta and Kālīkṛṣṇa); Pathuriaghata’s Nīlmaṇi and Baiṣṇabdās Mallik; Borobazar’s Nimāicānd Mallik; Āśutoṣ De of Simla; Sukhamay Rāy and his son Rāmcandra of Shukhbazar; Darpanārāyaṇ Ṭhākur; Rūplāl Mallik of Chitpore Road; Bābu Benoylāl Tagore; and Prāṇkṛṣṇa Hāldār of Chinsurah. Interestingly, newspapers of the time never contain invitations from the Sābarṇa Rāy Caudhurī family, who apparently even in the early nineteenth century resented the British presence in Bengal.5

Up until the 1830s, Europeans enjoyed themselves thoroughly—and unabashedly—at the Pūjā celebrations in honor of Durgā and, to a lesser extent, Jagaddhātrī.6 As early as 1766, J. Z. Holwell described Durgā Pūjā as “the grand general feast of the Gentoos, usually visited by all Europeans (by invitation) who are treated by the proprietor of the feast with fruits and flowers in season, and are entertained every evening whilst the feast lasts, with bands of singers and dancers.”7 English papers such as the Calcutta Gazette, the Calcutta Journal, and the Bengal Hurkaru did not simply print invitations from the Hindu aristocracy; British reporters themselves announced the festivities and urged their compatriots to attend. “In a word, if the reader be one who has never witnessed the magnificent spectacle of a Doorgah Poojah in Calcutta, we can only assure him that he will find the splendid fiction of the Arabian Nights completely realized in the Fairy Palace of Rajah Ramchunder Roy, on the evenings of the 26th, 27th, and 28th instant.”8

Indeed, the British commented favorably, even enthusiastically, on the “pomp and magnificence,” the “splendid arrangements and well regulated expenses,” the food, drink, and dancing, and the “wonder mixed with delight” they felt upon seeing scenes “grand beyond description” in the “native” houses9 (fig. 2.1). They also appreciated the reverence and hospitality shown them by their Bengali hosts. Said Mary Graham about her visit to the “fine house” of Rājā Rājkṛṣṇa Deb in 1810, “I was pleased with the attention the Rajah paid to his guests, whether Hindoos, Christians, or Mussalmans; there was no one to whom he did not speak kindly or pay some compliment on their entrance; and he walked around the assembly repeatedly, to see that all were properly accommodated. I was sorry I could not go the nautch the next night.”10 In 1825 the Bengal Hurkaru printed an editorial in which a British gentleman commented, “I went the first night and assure you I was much gratified,” and then urged everyone else to go as well.11 This unselfconscious British pleasure in the Pūjās, in which opulence, grandeur, and occasions for excess were provided and enjoyed, extended late into the nineteenth century.

FIGURE 2.1. William Prinsep, “Entertainment during the Durga Puja,” 1840. Pl. 25 in J. P. Losty, Calcutta, City of Palaces: A Survey of the City in the Days of the East India Company, 1690–1858 (London: Arnold Publishers, 1990).

Although one can find occasional reference to Durgā herself in European newspapers or travel diaries—L. de Grandpre from 1789–1790 and Maria Graham from 1810 both note that the clay statues of “Madam Doorgah” and her children were placed on a stage or a raised verandah inside the mansions12—she was rarely the focus of attention and was treated as a quaint sideshow vis-à-vis the main entertainments. This was not, of course, true for the Hindu hosts who opened their homes to the British. In addition to garnering prestige among their peers for the lavishness of their festival arrangements and the number of European guests whose praise they earned, Pūjā-sponsoring zamindars, even if working for the British, also tended to be religiously traditional. Their British guests simply did not understand what Durgā meant.

The Impact of Missionary, Reforming, and Anglicizing Critiques

… Offering incense to a God

Nothing but a painted clod.13

Durgā and her sister goddesses, as well as a host of Hindu deities especially including Jagannātha at Puri, were very much at the center of the social and political changes evident in Bengal in the third decade of the nineteenth century. The Company’s early policy of noninterference, encapsulated by Gov.-Gen. Charles Cornwallis’s Regulations of 1793, in which he had promised to “preserve the laws of the Shaster and the Koran, and to protect the natives of India in the free exercise of their religion”14—in effect implying that the British could know the society they ruled without sharing in it or revolutionizing it—came under Christian critique almost immediately. Some Christians, like Charles Grant, were in the Company’s Court of Directors, but most were missionaries, like Baptists William Carey and John Marshman, who strove after 1793 to overturn the Company’s ban on missionary presence and to gain unrestricted entry into India.15 Carey and his fellow missionaries at Serampore near Calcutta used their English and Bengali papers, The Friend of India and Samācār Darpaṇ, to claim that the Cornwallis Code should not be taken literally. After 1805, when the Company imposed the pilgrim tax at Puri, supposedly for the upkeep of the Jagannātha temple, Christian missionaries, company chaplains, and former officials began to take their cause back to England, where public opinion was formed, nursed, and inflamed by letters, travelogues, exposés of returning military men, and even the circulation of public petitions. By 1813 Evangelical petitions to Parliament had resulted in a clause in the Company’s Charter Renewal Act that admitted the principle of missionary activity in India. But since this was not mandated, and was left up to the local government, missionaries continued to be liable to cold-shouldering in or deportation from India.16

By the 1830s Europeans associated with the British reform movement began to arrive in India, people like Thomas Macaulay (arrived in 1834), the Scottish missionary Alexander Duff (arrived in 1830), and Governor-General Bentinck, all of whom believed that what was progressive for the West should be exported to the East. However, change did not occur immediately. Even Bentinck, famous for his criminalizing of sati in 1829, attempted suppression of the Thugs, diminishment of Wellesley’s College of Fort William, and replacement of Persian with English as the language of the courts in 1835, decreed in 1831 that his duty was to protect, not interfere with, Indian custom; he refused to bend to missionary pressure to abolish either slavery or the pilgrim tax (the latter being quite lucrative for the Company), and he would not force Hindus and Muslims to work on their religious holidays. Declaring that the government ought to show “a friendly feeling and … afford every protection and aid toward the exercise of … harmless rites … not contrary to the dictates of humanity and of every religious creed,”17 Bentinck regularly attended the Pūjā celebrations at the Shovabazar Rāj estates.18

But at the end of the 1830s utilitarian and evangelical criticisms in London combined to mandate change in Company policy. After the famous Dispatch in 1838, spearheaded by the two sons of Charles Grant, who claimed that intervention in Indian religious custom implied tacit approval of those customs that was unseemly and hypocritical for Christians, Parliament insisted that the Company dissociate itself from religious festivals, temples, and endowments. Full separation of the British from “idolatrous” rites, however, was effected only in 1863, when the government, now the British Crown, passed an act that could be enforced.19

This gradually evolving sea change in British attitudes toward Indian religion is reflected as if by script in the Pūjā festivities. While one looks hard to find even one or two criticisms of the festivals in the period before 1820, after this an increasing crescendo of critique leads eventually to the problematization of European attendance at the nautches. New values, characteristic of Protestant sobriety and utilitarian moderation and simplicity, caused Britons in Calcutta to begin viewing the Pūjā extravagances in a different light. Now judged to be decadent, immoderate, without taste, and obsessed with the pursuit of name and fame through the wasteful squandering of wealth, Pūjā sponsors were challenged instead to spend their money on something socially useful, like philanthropic charity. Some British commentators remarked wryly that they themselves might be responsible for the “natives”’ gaudy opulence, since “the more general diffusion of wealth and security for property introduced by the English government has contributed greatly to this change.”20 But, they continue, there is fault on the Indian side as well, since the showy pretenses of the Pūjā belie the degradation of the Hindu religion: Hindus have forgotten “the monotheistic spirit of the Vedas” and have favored immoral ostentation over sincere devotion, ritual over scripture;21 moreover, in allowing “Moosulman singing women” (later called prostitutes) into their mansions, and in serving meat and liquor, which goes against their own creed, they had ruined their faith.22 One can immediately recognize these early British tropes, as discussed historically and theoretically by Bernard Cohn, Richard King, David Lorenzen, Arvind-Pal Mandair, Thomas Metcalf, Brian Pennington, and Sharada Sugirtharajah: the assumption that Hindus and Muslims have, or should maintain, separate and non-intersecting spheres, governed by “creeds”; the degeneration of religion; the nostalgia for the perceived Golden Age of Hinduism, partly constructed by the British through their selective search for the “classical” in Hindu history; and the valuation of the rational, ethical, and private over the ritualistic, effervescent, and public forms of religion.23

In addition to financial and moral profligacy and the departure from tradition, Hindus were accused of idolatry, their worship compared to outmoded “Old Testament” practices. Missionaries tried to impress upon the minds of their British readers that mixing with Hindus at the nautches was in effect doing Durgā honor.24 “We must not forget that the disbursement of money from the funds of Government to perform the worship of the ‘Belly God,’ however insignificant it may appear[,] produces an equally false and pernicious impression on the minds of the Natives. For the preservation of our national honor and our Christian dignity, the system of affording public patronage to idolatry must be entirely demolished.”25 This theme of dignity is ubiquitous in the late 1820s and 1830s, and accounts in large part for the strenuous attempts of missionary and other sober-minded Britons to stop their compatriots from shaming the entire foreign community in front of the “natives” by their bad behavior at the Pūjās. “We regret that these hospitable ‘spectacles’ given by the native gentlemen are so frequently abused. We are sorry to state that four Europeans carried off a buggy, which was yesterday morning found broken in pieces, and the horse discovered in a street tied to a post!”26 Although sometimes the scandalous behavior was exhibited by people who ought to know better—the Friend of India reported disapprovingly of a Mrs. Atkinson dancing publicly in the house of Gopimohan Deb of Shovabazar27—often English-newspaper editorials betray European class schisms, with “polite” society frowning upon the raucous and unmannered deportment of the lower orders.28

In a splendid poem from 1829, a British writer describes Britons who attend the festivals as idolaters, hypocrites, and low-class sops:

Infidels to England’s God,—

Doorgah’s mysteries may applaud—

Or, bowing, may before her stand,—

Lords of a holy Christian land.—

And others who would fairly go—

To Latin for a quid pro quo—

Religion, with such men as these

You may rely on is—Rupees …

Petty fops, with spurs and boots—

Uniform that any suits—

Pert un-civil clerks who then

Put aside for once their pen

Youngsters of all sorts and hues,

Indians, English, French and Jews

Saturated with champaign—

May we never meet again.29

Missionaries endeavored to suggest new ways of intercommunity mixing that did not lend themselves to shameful antics—“conversation parties,” for instance, in order that the “Natives be brought under the full power of the courtesy and intelligence of superior minds”30—and the anti-Indian, anti-missionary, pro-military Englishman tried to provoke its readers into eschewing the Pūjā festivities by printing a fabricated letter demonstrating the horrifying results of interracial mixing. Writes Ramchunder Chingree: “Then in few time no difference in country. Black people white people—black dancer, white dancer, all same. Glory to Bramah and Gopee Mohun Deb. Now all same equal people and Free Press is the great commission.”31 That even by the late 1830s there were varied British responses to the issue of Pūjā attendance is illustrated by a flurry of letter and counter-letter writing in 1839: a writer for the Englishman proffered the opinion that attending the nautches was an opportunity to reform the Hindu aristocracy, while the Bengal Hurkaru, often pro-Indian, urged the propriety of supporting the idolatry of the country through the resources of the state as a restitution for the murder and spoliation inflicted upon them by British governance. To both of these the Friend of India replied that “the best way to make up for wrongs, if there be any, is by giving India the blessing of a Christian Government.”32

Britons were not the only critics of the Pūjās. Indian Christian converts, Brāhmos, Vedāntins, Derozians, and members of the Hindu Theophilanthropic Society also joined in the attacks. Dakṣiṇrañjan Mukherjee (1814–1898), a Derozian reformer, led a crusade against Pūjā “vulgarities” in his paper, the Jñānānveṣan, and Ram Mohan Roy is said to have refused a Pūjā invitation by Dwaraknath Tagore. Dwaraknath’s son Debendranath (1817–1905) also later condemned idol worship. Representative of the Brāhmo viewpoint is an editorial in Debendranath’s journal, the Tattvabodhinī Patrikā, for 1846. Image worship is stated to be mere play-acting by childish people who wish to gain fame by their sponsorship.33 Point 2 of the Brāhmo Covenant, as formulated by Debendranath, avers, “I will never worship any created object as representing that Supreme Being.”34

Starting in mid-1820s, several Calcutta papers began congratulating their readers for the diminution in European attendance at the yearly nautches, resulting, they asserted, in a decrease in wasteful spending on the part of wealthy Hindus, purification of their religion, and safe-guarding of British respectability.35 However, other evidence undercuts their claims; indeed, one finds continuous reports of Britons enjoying themselves at Pūjā festivities all the way up to and even beyond the 1857 revolt. From 1846: “If the sermon, last Sunday, at the Scotch Kirk, has had any effect in deterring parties from attending the nautches given by the rajahs during the present native festival, it has been of an extremely partial nature. For the last two nights, the house of the Rajahs Radhakant and Shiva Krishna—but especially of the former—have been thronged by Christians, many of them men of rank and standing in Society…. The visitors, on both occasions, were equally numerous and respectable, members of the Military Service and the Legal Profession forming a large portion of the whole.”36 In an unsuspected twist, some British attendees even mourned the lavishness of the “old days,” the beauty and sensuousness of the former dancing girls—“Niku is lost, and lies in the cold grave without a successor … Where are [her] rich tones, [her] unequaled music?”37—while others, as late as 1855, are clamoring for invitations, so that they do not miss the Pūjā fun: “[P]eople of all classes are being responded to in the [Shovabazar] Rajahs’ usual kind and liberal spirit. We hear that the services of the ‘Wizard of the North’ have been engaged for both nights.”38

In spite of the continued enthusiasm into the mid-nineteenth century of much of British society for the most famed Pūjās, it does appear that Hindus whose celebrations were smaller or less noted did begin, from the 1830s, to close their doors to British guests.39 Some Indians appear to have been persuaded by British and Brāhmo arguments condemning opulence, religious degeneration, and debauchery; others, squeezed by British mercantile and business interference, and affected by the collapse of traditional patronage systems after the Permanent Settlement of 1793, simply became too poor to throw parties. Such impoverishment of the “natives” rarely finds acknowledgment in the British press, and when it does it is attributed not to the imperialist economy but to Indians’ “injudicious spending.”40 Hence the Pūjās were symbolic of the relations between Indians and Britons in several ways: they provided the means for intercommunity prestige and muscle-flexing; they represented, to both Hindu and Briton, the essence of Hindu tradition, either to be reformed, transformed, dissociated from, or protected; and they fell victim to ideological and economic changes wrought throughout the colonial state in Bengal.41

To illustrate just how central the Pūjās were to the continuing negotiations over Hindu–British relations in the early decades of the nineteenth century, we should briefly examine the controversy over vacation days that erupted in 1834. In 1793, when the judiciary courts were first introduced in Bengal, Cornwallis apparently consulted the relevant pandits and chose, in his Regulation III, section 1, of that same year, to “frame the list of holidays in the public offices according to the religious prejudices and customs of the inhabitants.”42 In July of 1834, however, the Bank of Bengal—allowing itself to be swayed by business and merchant petitions—announced that bank holidays would be reduced from 34 to 16, effectively cutting out, among other holidays, Kālī Pūjā.43 The Hindu reaction was swift: an outpouring of letters to the government, claiming that (a) the bank was bending to the wishes of a few merchants, (b) the government, in turn, was being swayed by the city’s financial institutions, and (c) since the bank had not consulted any pandits, how could it know which Hindu holidays were to be kept holy? “Is the religion of the Hindoos to be guided by the bank directors?” Further, the letter-writers countered that (d) such bowing to a Christian lobby was a violation of the impartiality to which the British government had pledged itself; it is barbaric, they stated, to think that “Might constitutes Right.”44 A slew of replies and counter-replies ensued: Englishmen claimed that Hindus too transacted business on holidays when the banks were open; Hindus retorted that their compatriots had been bribed to do so and thanked English merchants who had refrained from using the bank on the Hindu holiday; other merchants came forward to say that they and their agents had indeed been inconvenienced by there being so many bank holidays; Hindus accused the Hindu dewan of the Bank of Bengal, Rām Komal Sen, of pandering to his own Vaiṣṇava leanings by cutting out Kālī Pūjā but retaining Kārtik Pūjā; and Englishmen responded that “Kaly Poojah is not incumbent upon Hindoos.”45

The principles upon which the matter was contested were, for the British, Hindu authenticity and, for the Hindu protesters, British commitment to the ideal of neutrality. Both tried to hold the other to what they believed to be the other’s stated precepts, often founded on precedent. For instance, the vice president of the bank announced that the Kālī Pūjā order would be rescinded if it could be shown that to do business on the holiday was a violation of religion. Ultimately, in reply to a petition signed by four hundred Hindu inhabitants and merchants of Calcutta, the government replied that while it could not mandate the closing of all offices on all Hindu holidays, it could allow Hindus to take holidays on those days, provided they understood that in some cases they might have to work. And “we know that the transaction of business does not contradict Hindoo holiday law.”46

The tussle between productivity and the policy of noninterference in religious custom—between merchants and banks, on the one hand, and government officials (who tended to support “native” sentiment in this period) and Hindus, on the other—was never fully resolved. Although the 1834 proposals were defeated, a perusal of newspapers during the Pūjā season from the 1830s through the end of the nineteenth century indicates just how volatile the issue of holidays continued to be. Until 1861 the total number of Hindu holidays for the year remained at thirty-five days, with the usual twelve for Durgā Pūjā.47 Even in 1879, when the holidays were reduced to twenty-two days per year, or in 1900, when the Government of India issued orders that Christian holidays and Sundays were necessarily to be observed in all offices, but that Hindu holidays, such as Durgā Pūjā, were up to the discretion of employers, Durgā Pūjā stayed at its full length of twelve days—although some Hindus were required to work part or all of this time.48 Twice, in the October months of 1840 and 1860, Britons proposed that the Pūjās be moved to Christmastime, when the weather would be better, Christians would be more inclined to support the idea of long holidays, and “Madam Doorgah” would be pleased, as the increased coolness would help invigorate her worshipers.49 Interestingly, while missionaries occasionally sided with the mercantile position, they appeared to take very little interest in the length of the Pūjā festivities, preferring to concentrate their efforts on dissociating Europeans from attending such idolatrous functions.

The thirty-year period, then, prior to the uprising of 1857, was a time of testing, challenge, and debate, as Anglicizing, Utilitarian, Christianizing attitudes met and sparred both with more tolerant, pro-Indian British commitments and with Hindu conservatives, who themselves were working to defeat the anti-idolatry programs of the Brāhmo Samāj. The Pūjās were the nexus of these ideological and social fights, accommodations, and dissonances.

After the Transfer of Power: Evolutions of the Pūjās from 1858 to 1918

A Good Excuse for a Holiday: British Experiences up to the Close of the Great War

“We have won India, but we have not yet beaten Doorga.”50

After the government of India had passed from the East India Company to the British crown in 1858, a clearer, more explicit policy of noninterference in Indian religious and customary law was articulated and followed by Britain. And it appears that almost immediately the Pūjās reflect the new sociopolitical currents. While one can still observe British critiques of Hindu idolatry, irrationality, and the lack of social usefulness as demonstrated in the festivals,51 overall there is an astonishing change in British attitudes toward the holidays. One writer for the Bengal Hurkaru articulated the new rule in 1865: “Our friends would persuade us that absence from business for the period of ten days at the time of the Pooja is to them a necessity of the faith. It is thus that we, the ruling power of the country, have come to look upon the Pooja as a domestic institution, and arrange our own yearly holiday so as to accord with it.”52 Even more poetically, from 1870: “Doorga is supreme, high above all powers and potentates, banks, and custom houses—everything! … The holiday is of most importance to us Westerns, or to such of us as can make a holiday; and Doorga is strong enough to secure the holiday as if with a band of iron.”53

After 1860 evidence abounds that Britons, having accepted the policy of noninterference in the Pūjās, made them a welcome excuse to get away from Calcutta. Newspaper editors bemoaned the fact that they were marooned in the dull, “empty” city that has “gone to sleep for a fortnight in honor of the Doorga poojah festival; at least that portion of Calcutta society which has been unable to transfer itself from the ditch to the heights of Simla or Nynee Tal, or to go down to the Bay, braving a prophesied cyclone in the desire to inhale ozone.”54 Moreover, the English-language papers, such as the Bengal Hurkaru, the Englishman, and the Friend of India, sponsored aggressive advertising campaigns for travel and holiday goods, such as skates, insecticides, pruning knives, sparkling champagne, hats, rugs, picnic baskets, and English boots. There are fewer outcries from the nonmercantile community for the curtailment of the holidays;55 to the contrary, in 1861 one European inhabitant of Calcutta wrote to say that the fourteen-day office closing that had been granted by the Viceroy to Hindus should be granted to everyone, since even Christians looked forward anxiously to a chance to escape the killing climate.56

For those Britons who stayed in the city, interestingly, entertainments proffered especially by the Shovabazar rājās continued to be an attraction. The Englishman, the Friend of India, and the Statesman and Friend of India newspapers publicized invitations year after year from the early 1860s until the 1880s. As in the halcyon Pūjā years, writers praise their hosts’ music, dancing girls, acrobats, magicians, theater performances, and hospitality. By 1890, however, the mixing seems to have fallen off completely, with the Pūjā connoting vacations and law-and-order problems for the British, and something both more private and more publicly defended for the Hindu.

Hindu Defense and Reconstruction

“Who is she?”

“The Mother.”

“Who is this Mother?” asked Mahendra.

The monk answered, “She whose Children we are.”

“Who is she?”

“You will know her in time,” was the answer. “Now sing Bande Mataram, and follow me.”57

The post-1858 half-century was troubled for Britain’s Indian subjects. British suspicion of Indians as a result of the “mutiny” only deepened the lines of separation between the two communities, spatially and ideologically; the result was increasing racism and imperialism, coupled with a desire to order, control, and categorize, on the part of the British, and the generation of incipient nationalist feelings, on the part of Indians. For instance, by the 1880s public controversies raged over the 1883 Ilbert Bill, concerning the right of Indian judges to try European cases; the Bengal Tenancy Act, which attempted to redress some of the grievances felt by peasants as a result of the Permanent Settlement of 1793 (zamindars, represented by the British Indian Association, strongly opposed this act); and the growing feeling of political impotence, in spite of apparent advances in local self-government as embodied in the Bengal Municipal Act of 1884 and the Bengal District Board Act of 1885.

Indeed, many Indians were not persuaded by the rhetoric of neutrality and secularity as promulgated by the colonial state, and perceived the government to be Christian, biased, and patently dishonest in its rule. However, we do not get a full-blown nationalism in this period; post-1858 Bengali leaders tended to be bhadralok—elite, high-caste, and interested in cultural and religious revivalism. There was no Pūjā news coverage, in English or Bengali, of the years immediately following 1857 that made recourse to politicized Śākta imagery. With very few exceptions, newly formed political organizations, such as the Hindu Sabhā, founded in 1869 by men drawn from the Ādī Brāhmo Samāj and several aristocratic families of Calcutta for the glorification, unity, and improvement of Hinduism, could not yet conceive of complete independence and did not resort to the language of religion to whip up fervor or explain their platforms. The Hindu melās, or national festivals, established in 1867 to provide a space for the display of indigenous identity and virility, offered lectures, songs, agricultural produce, animals, birds, machinery, handicrafts, athletic competitions, and plays. But they claimed no overlap with the Pūjās, and did not utilize the language of śakti.58 Satyendranath Tagore’s famous song, “Mile sabe Bhāratsantān” (“All together, children of Bhārat”), which he composed for the first melā, evoked national pride, but did not yet express hostility toward British rule.

Even the Indian National Congress, founded in 1885 as a loyalist, moderate political institution, was not yet a vehicle for politicized religion. The closest connection I have been able to find between the Congress and the Pūjās is a metaphor from 1887 in which the Congress is a Pūjā to the Motherland, whose ten hands are the ten classes of Indians. She is fighting two anti-Congress demons, the orthodox and reformist Hindus. The English too must be beaten, but by the employment of their own methods and weapons, in a battle on English principles.59

That “for the most part, politics and religion were not yet intermingled”60 can also be seen by examining the overtly religious voluntary organizations that tried to influence the British for social change: the Ādī Brāhmo Samāj and the Sādharan Brāhmo Samāj of Debendranath Tagore and Sivanath Sastri (1847–1919), respectively, which eschewed image worship and, by extension, the Pūjās61; and the highly devotional and emotional practices of Keshab Chandra Sen (1839–1884) in his “New Dispensation,” where the veneration of the “Mother Divine” as a guiding inspiration was a personal outpouring, not the recourse to an image of a colonized Motherland.62 The same interiorized perspective on religion is evident in the life of Rāmakṛṣṇa (1836–1886), the Bengali saint of Calcutta; as a temple priest of the goddess Kālī, he performed the Śākta Pūjās yearly and encouraged his disciples to do so as well, all in a nonpoliticized arena of spiritual development.

Bankim Chandra Chatterjee (1838–1894), now considered one of the forerunners of early Indian nationalism for his 1882 novel Ānandamaṭh, its theme song, “Bande Mātāram,” and its likening of India to a goddess, may come closest to the sort of religious nationalist that we later find in the early twentieth century.63 The novel depicts a group of citizens-turnedrenouncers in the 1770s who are fighting the nawāb’s men, and the British, for control of Bengal. They revere both the martial figure of Kṛṣṇa from the Mahābhārata and the powerful Goddess, and in their leader’s cave they have erected three statues, representing India past (Jagaddhātrī), India present (Kālī), and India future (Durgā). “Victory to the Mother” (“Bande Mātāram”) is thus a conflation of the Mother and the Land.

Powerless? How so, Mother

With the strength of voices fell,

Seventy million in their swell!

And with sharpened swords

By twice as many hands upheld!

To the Mother I bow low,

To her who wields so great a force,

To her who saves,

And drives away the hostile hordes!64

Bhakti, image worship, and the ideal of active participation in society were essential to Chatterjee, and he was also a fervent advocate of Indian rights over British arrogance, as can be seen in his excoriating public letters published in the Statesman to one W. Hastie, who had critiqued the extravagant funeral ceremony performed at the Shovabazar Rāj estates in September 1882. Writing first under a pseudonym, Chatterjee defended the rituals and then challenged Hastie to learn something about India, not from Europeans but from a “believing Native.”65 Nevertheless, as scholar S. N. Mukherjee points out, Chatterjee was only constructed as the hero of “Extremist” nationalists thirty years after the publication of Ānandamaṭh66; the mood in the forty years after 1857 was defensive as concerned religion and still hopeful as concerned Moderate politics.

The wealthy Hindu doyen apart, most average Hindus had always, when possible, used the holidays as a time to visit their ancestral villages, but with the introduction of public train travel in 1853 and the birth in the 1850s and 1860s of various Bengali newspapers dedicated to chronicling the public sphere—the Bengalee, the Amrita Bazar Patrika, and the Hindoo Patriot—we get reports of such journeys. Now Calcutta is characterized as “empty” from a non-British perspective as well. The idea of the Pūjās as an opportunity to relax on holiday, an import from the British, also slowly began to catch on among the Hindu public. Noted the great Moderate politician Surendranath Banerjea (1848–1925) about his trip to England in 1868, where he watched Britons going south for the summer to seaside towns: “[O]ur people during the great Durga Puja vacation stayed at home, celebrating the Pujas and enjoying the festivities, but neglecting the golden opportunity that the holidays presented for rest and change. Later on a change to Madhupur and Baidhyanath, and sometimes to Darjeeling, grew to be popular, and I had the proud satisfaction of strengthening the popular feelings and the popular movement by helping to make Simultolla a health-resort for the middle classes.”67

In the post-1858 era, Pūjā coverage written about or from an Indian perspective was focused almost entirely on a vigorous defense of the holidays, on their own grounds. Some of this polemic was written to justify Hindu rituals in the face of British critiques, and indicates the self-identification of the colonized with the perspective of the colonizers, even as the former struggled to validate a separate self.

Answering the charge that they were socially irresponsible, several of the old aristocrats began to use their wealth for public welfare projects, educational endeavors, and the founding of hospitals. After the Rebellion, in 1860, the Bengal Hurkaru reported that the scion of the Shovabazar Rāj house, Rādhākānta Deb, issued invitations to a pyrotechnic display, “not in honor of Durgah, but to celebrate peace in India.”68 But even those who continued to celebrate the festival began to argue for its significance in a new way: as a social institution with a “benign and wholesome influence,” inculcating in Hindus what Christmas does in Christians: joy, charity, love of home, forgetfulness of toil, and the chance to reunite with loved ones.69 Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, in his essay “On the Origin of Hindu Festivals,” tried to trace the original impetus behind Durgā Pūjā to ancient Indian astronomical observations, separating the proto-scientific from the present superstitious elements of the festivals.70

Further explanation, justification, and implicit or explicit argumentation for the importance of the Pūjās as a national religious festival occur in a spate of mostly Bengali pamphlets that appeared in the 1870s. Several of them presented their material in an objective, descriptive manner, narrating what happens when and why during the four days of the celebrations, and omitting all references to nautches or secular entertainment; others were plays or poetry collections in which stories of the Pūjās were preserved for posterity; and still others presented satirical sketches of Bābu culture at the Pūjā season.71 One early play by Kirancandra Bandyopādhyāy, from 1873, Bhārat Mātā, is similar to Bankim’s Ānandamaṭh in that it foreshadowed a later explicit use of the Goddess-Motherland equation: Bhārat Mātā is a widow, with hardly a trace of her former beauty and auspiciousness.72

This defensive, apologetic, even proud attitude was certainly intended as a foil to British stereotypes and judgments. The other important interlocutors continued to be the Brāhmos, who in their various split branches maintained their critique of the festivities for idolatry, irreverence, and animal sacrifice. The Indian Mirror, in a very judgmental article about Durgā Pūjā from 1889, claims that people clamor for Western luxuries as basic necessities. “The Durga Pujah then, would seem to be the festival of English-fashioned shoes, the Chinese shoe-makers officiating as high priests of the ceremony! … The festival has become a shameful travesty of religion, a season for the selfish enjoyment of the rich, and a period for the lamentation of the poor. And nature herself resents the approach of the time, and famine and flood scourge the land. All round there is nothing but misery, and Durga deserts her votaries in disgust!”73

The Brāhmo position was influential but not triumphant; voiced alongside it were the opinions of Hindus who included the Pūjās within an emerging program of cultural revivalism, pride, and self-expression. By contrast, British Pūjā experiences, now zealously guarded and enjoyed in the hill stations, clubs, and mini-English enclaves of the country, showed the increasing separation between Indian and British during the half-century after 1857.

1905–1918: Partition, Pūjā, and the Rigors of War

The Mother’s worship can no longer be performed with fruit and flowers.

The Mother’s hunger can no longer be appeased with words only.

Blood is wanted!

Heads are wanted!

Workers are wanted!

Warriors and heroes are wanted!

Labor is wanted, and firm vows and bands of followers;

The Mother can no longer be worshipped with fruits and flowers.74

From the Bengali point of view, British insensitivity, arrogance, and imperialistic ambition reached intolerable heights at the turn of the twentieth century. Under Lord George Curzon’s administration (1899–1905), during which there was severe inflation and a steady rise in English-educated Indian unemployment, the British continued to disregard local sentiment by passing the Calcutta Municipal Bill and the Universities Act, in essence tightening control over the Calcutta Council and university education, even though Indians had strenuously protested. One sees in the Indian press evidence of a new emphasis on strength and manliness, associated now with the Goddess. In its lead article on Durgā Pūjā for 1903, the Bengalee stated that the Durgā image was “the emblem of our Indian nationality, not as it is but as it should be.” “Save thy suffering children, for life to them is an eternal anguish, save them from famine, from … pestilence, from … misery …, and teach them, O Dread Mother, above all things, teach them to be MEN.”75 This desire to prove wrong the British stereotype of the effeminate Bengali by infusing youth with physical pride found expression in the efforts of Śaralādebī Caudhurāṇi (Ghoṣāl) (1872–1945), a niece of Rabindranath, who in 1902 established the practice of celebrating heroes (bīras) on what she called Bīrāṣṭamī Utsab, on the eighth (Aṣṭamī) day of the Pūjās. She also founded an academy for martial arts in south Calcutta. These initiatives are evidence of all-India linkages and influences, as Śaralādebī had spent her young years in Western India with her uncle Satyendranath, where she witnessed B. G. Tilak’s revival of the Gaṇapati and Shivaji coronation festivals in the mid-1890s, as well as the organization of societies for physical and military training.76

The shock came on July 20, 1905, with the announcement of the partition of Bengal into two manageable administrative divisions, as a result of which Muslims would be in a majority to the east and Hindus to the west. Protest meetings were held at over three hundred cities, towns, and villages in Bengal. The tactic decided upon was a swadeshi boycott, where Bengalis would refuse to buy or use anything not made in India.

Sumit Sarkar has thoroughly summarized and analyzed the various Moderate, Constructive Swadeshi, Political Extremist, and Terrorist reactions to the partition77; for our purposes here it is sufficient to note that the increasingly aggressive Extremist factions made use of religious symbols for explicitly political and anti-British purposes. Moderate “beggars” like Surendranath Banerjea were mercilessly pilloried by new leaders such as Aurobindo Ghosh and Bipin Chandra Pal and in nationalist newspapers like the Amrita Bazar Patrika, Baṅgabāsī, Yugāntar, and Ghosh and Pal’s paper, Bande Mataram, begun in 1906. Revolutionary societies, such as the Anuśīlan Samiti, a countrywide organization for an armed revolution, often preached violence, and many gymnasia teaching wrestling, lathi play, and martial arts, following upon the example of Śaralādebī Caudhurāṇi’s academy, were formed for the purposes of armed resistance. In Mymensingh, she and Bipin Chandra Pal also founded a festival modeled on that for Shivaji; in searching for a Bengali hero, they settled upon Rājā Pratāpāditya of Jessore, who had headed an unsuccessful rebellion against Aurangzeb.78 They also celebrated Kālī, Pratāpāditya’s tutelary deity, consciously creating a parallel between Kālī and Bhavānī, Shivaji’s goddess. Wrote Pal, crediting his colleague for her inventiveness, “As necessity is the Mother of Invention, Sarala Devi is the mother of Pratapaditya to meet the necessity of a Hero for Bengal.”79 Another “first” associated with her name is the employment of “Bande Mātāram” as a national slogan: this occurred in 1905 under the auspices of the Mymensingh Suhrid Samiti, of which she was a member.80

Overall, as Barbara Southard has argued, Bengali militants in the 1905 partition upheavals used a Śākta idiom to rouse passion and support for their cause.81 Two images of the Goddess-Motherland equation alternated in public discourse: one drew upon the Goddess’s martial, all-conquering strength, or śakti; and the other focused on her frailty, weakness, and need for protection. Bankim’s Ānandamaṭh also contributed to this oscillating, complex construction of the Mother; her renouncer-children had to be strong both with her and for her.82

Aurobindo drew self-consciously from Ānandamaṭh, in his “Bhawani Mandir” of 1905, utilizing the trope of the Goddess-Motherland to awaken her sons to self-sacrificing obedience. “For what is a nation? What is our mother-country? It is not a piece of earth, nor a figure of speech, nor a fiction of the mind. It is a mighty Shakti, composed of the Shaktis of all the millions of units that make up the nation, just as Bhawani Mahisha Mardini sprang into being from the Shakti of all the millions of gods assembled in one mass of force and welded into unity.”83 Or, in a letter home on 30 August 1905: our country “is not merely a division of land, but it is a living thing. It is the Mother in whom you move and have your being.”84

Practical applications of this championing of Śakti-worship were many in partition years, and the uses to which the Pūjās were put changed considerably from those of the previous period. The Durgā Pūjā, which had symbolized harmony, mending of broken relationships, and joy, tended still to be the provenance of the Moderates85; more politicized valences were added by swadeshi politicians who wanted to fuse in the popular mind the identification of the Mother Goddess with the Motherland. Revolutionary Jogesh Chandra Chatterji recounts that when he was nine or ten in 1904–1905 a group of nationalists arrived in his village in Dacca district, clad only in khādi and singing, “[B]ow to the coarse cloth[,] as our poverty-stricken unhappy Mother India cannot afford to give us anything better.” Most of the children that year, he wrote, did not get Manchester-made clothes for the Pūjā season.86 The Bengali-owned papers of the period were full of gift advertisements “For the Poojahs. Nothing Bideshi, Everything Swadeshi”87: indigenous oils, silks, dhutis, saris, shoes, tea, sugar, and cigarettes with brands named like Vidyasagar, Sri Durga, and Durbar (fig. 2.2). Many people came to Kālī temples to take swadeshi oaths, and Bankim Chandra’s “Bande Mātāram” became the political slogan of the time throughout Bengal.

FIGURE 2.2. “For the Poojahs.” Bengalee, 3 Oct. 1909, p. 10.

Although all Bengali political groups participated in and supported the national Durgā Pūjā festival, organizations that condoned violence tended to emphasize Kālī over her sister goddess. Bipin Chandra Pal explained this preference in a lecture given at the Shovabazar Rāj estate on 25 May 1907. As a tribal war deity, he stated, Kālī is a symbol of race-consciousness; besides, Bankim Chandra had already established her as the symbol of India, the ravaged and hungry “Mother as She is,” and hence revolutionaries of his time should build upon Bankim’s image. Pal urged the establishment of Kālī Pūjās in every village every month, but counseled that she be given the heads of white goats, not the typical black ones. This, he felt, would energize Bengali spirits and demoralize British ones.88

Revolutionary societies such as the Anuśīlan Samiti in Dacca created small hand-held bombs called “Kālī Māi’s boma”s and made reverence for Kālī a signal part of their induction rituals: a person could become a full member only if he took a vow in front of a Kālī image that he would, in a manner parallel to that of the renouncers of Ānandamaṭh, sacrifice everything for the cause.89 The Samiti’s paper, Yugāntar, advocated this same self-sacrifice in prose; according to the 2 May 1908 issue: “The Mother is thirsty and is pointing out to her sons the only thing that can quench that thirst. Nothing less than human blood and decapitated human heads will satisfy her … On the day on which the Mother is worshiped in this way in every village, on that day will the people of India be inspired with a divine spirit and the crown of independence will fall into their hands.”90 Again, “Without bloodshed the worship of the goddess will not be accomplished … And what is the number of English officials in each district? With a firm resolve you can bring English rule to an end on a single day.”91

The British were certainly one object of Śākta-colored political aggression. The other “other” of the partition years was the Muslim community. After the announcement of partition on 16 October 1905, Muslims were taken by surprise at the virulence of Hindu opposition to the British fiat. The swadeshi boycott also hurt poor rural Muslim shopkeepers, who could ill afford to exchange their goods for swadeshi products and who resented being forced to join the movement.92 By October 1906, Muslims all over Bengal were celebrating the anniversary of the partition, and two months later the Muslim League was founded in Dacca, for the protection of Muslim interests. The communal antagonisms continued to worsen; in Mymensingh in eastern Bengal in 1906–1907, Muslim peasants, newly emboldened because they thought they had the British government’s backing, rose up against their Hindu landlords. Encouraged by religious leaders, they refused to render traditional acts of service and declined to participate in Hindu festival processions. In some areas there was vandalism of temples, in response to “Bande Mātāram”–chanting Hindu provocateurs.

It is important to realize that communal disturbances had been relatively rare in Bengal up until this point. From the 1880s on, political leaders among Hindus and Muslims would regularly meet in advance of their mutual festivals to discuss precautionary measures; very little occurred in Bengal that resembled the riots over cow-killing at Bak’r-Id in Bihar, the United Provinces (U.P.), or the North West Frontier Provinces in 1893. In what may seem to be an exception, Dipesh Chakrabarty, in a study of riots in Calcutta jute mills in the 1890s, demonstrates that communal tensions did arise in parts of the city in which large numbers of immigrant merchants and laborers had settled; agitations were sparked over the government’s proscription of cow-killing (korbāni) during Muslim festivals, and jute workers, Hindu and Muslim, began to assert their rights to observe their religious festivals without interference either from the other community or from the government. Nevertheless, Chakrabarty also argues that this communal culture was essentially imported, with the majority of the rioters hailing from precisely those districts of Bihar and U.P. that had seen cow-killing riots from 1889 to 1893. Most of the Muslims who petitioned the government to allow cow-sacrifice were Urdu-speaking, and the majority of the Hindu leaflets protesting the same were remarkably similar to those distributed in Bihar and U.P. a few months earlier.93

Why did controversies over language, cow slaughter, religious and social festivals, representation on consultative and legislative bodies, education, and government jobs not assume the same communally explosive proportions in Bengal as elsewhere? John R. McLane, in his analysis of the partition era in Bengal, notes that prior to 1900 and unlike in north and central India, there was no large-scale sense of a “Hindu community” in Bengal, nor a “Muslim community” defined in relation to pan-world Islam and against the influences of local Hindu culture.94 Indeed, in Bengali rural areas in the late nineteenth century Hindus and Muslims had more in common with each other than either did with their mainly Hindu bhadralok landlords. Moreover, the circumstances that gave rise to communal unrest in towns in U.P. in the 1890s, for instance, did not arise in Calcutta or in rural Bengal: what Nandini Gooptu calls “bazaar industrialization” among rapidly developing towns like Allahabad, Banaras, Kanpur, and Lucknow, with great influxes of migrant poor, a competitive labor market, especially between Śūdras, Untouchables, and poor Muslims, and the proliferation of unskilled work, did not arise in the more stable port towns of Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras.95

Another reason for the relative communal quiet in Bengal, before and even during the anti-partition struggles, is the position of the Moderate politicians. Sensitive to the need to keep Muslims and Hindus together, Moderates urged both communities to forget their political differences, blaming the British for their attempt to divide and rule. “The enemies of our race, the birds of prey and passage, are interested in fostering and promoting [dissension]. Let us not play into their hands … let us profit by the legend of the Bijoya Dasami ceremony, and once again let the voice of amity and good-will be heard among all [Hindu, Muslim, and Christian] sections of our great community.”96 In 1905 Rabindranath Tagore extended the symbolism of Brother’s Second, a ritual of bonding between brothers and sisters that is celebrated right after the Pūjās have concluded, to evoke friendship between Hindus and Muslims: members of both communities would tie red threads of brotherhood on each others’ wrists. All throughout the partition period, these rākhi-bandhan ceremonies were regularly announced in the Bengali and English papers. In addition, some landlords, even the British Indian Association, saw that the boycott and emphasis upon swadeshi items were disturbing peace with rural Muslims in their areas, and withdrew their support. Liberal Hindus also continued to offer a countervailing interpretation of the Pūjās: the Hindoo Patriot maintained its critique of idolatry and urged that the festivities be viewed as a time of social harmony and happiness that unites Hindus, Muslims, and Christians.97

Hence, while militant Hindus did draw upon Śākta imagery to whip up anti-British fervor, when it came to relations with Muslims, the Pūjās were sites of conflict, but not cited as symbolic of the dominance of a Hindu śakti over a Muslim demon. Instead, it is the festivities’ potential for social cohesion that is frequently employed in the effort to rein in communal tension.

The fervor of the partition period could not sustain itself. There are many reasons for this—the withdrawal of support by the landed classes and the British Indian Association in 1908; the split of Congress in 1907; the weakening of the Extremist lobby through the departure of Bipin Chandra Pal for England in 1908 (when he returned to India he sided with the Moderates) and the imprisonment of Aurobindo in connection with the Alipore bomb case of 1908 and then his departure for Pondicherry in 1910; British repressions of the press, illegalizing of many Samitis, and deportations of the movement’s leaders; and British attempts at conciliation through the Morley-Minto Reforms of 1909 and the 1912 reunification of Bengal. However, many of the tactics tried in Bengal at that time were later used to greater effect by Gandhi, and the politicizing of the Śākta tradition, particularly Durgā, Kālī and their Pūjās, now became a historical resource that could be drawn upon again, when the time came.

After the removal of the capital from Calcutta to Delhi in 1912, the next six to seven years were taken up principally with preparations for involvement in the First World War. During the war itself, there is little attention to the Pūjās, in either English or Bengali, mostly due to wartime restrictions, the bridling of newspapers, and the need for print space to provide maximal coverage of the war. Some Hindu sentiments carried on, seemingly unchanged: the anti-idolatry campaign voiced in the Tattvabodhinī Patrikā, and the concern to protect Hindu holidays from reductions and Hindu employees from being deprived of their chance to join their families. That even in the war years the British were still attached to the Pūjā is indicated by a complaint from one “Indian assistant” in the Amrita Bazar Patrika on 18 October 1917. He claims that Pūjās appear to cater to the Europeans, who cannot wait to get away to the hill stations and who leave their Indian workers in charge of their offices during the festival. “So it seems that the festival is for the Europeans!”98 The most belligerent the papers get in the war years is to moralize to the British about peace. “Jesus Christ preached the Kingdom of Heaven. His white followers, generally speaking, however, hunger for a different kind of kingdom. The result is, that they fly at and cut one another’s throats.”99 At the outbreak of war, the Amrita Bazar Patrika had this to say to its readers about the Pūjā: “The main object of Christmas, we believe, is also the same. But the Christian nations have clean forgotten it, and they are now behaving in a manner which makes every good man shed tears of bitter sorrow. How we wish that the Bijoya or Christmas spirit prevailed among the belligerents in Europe, so that they might lay down their blood-stained arms and embrace one another in brotherly love. The spirit of the Bijoya means the spirit of peace and goodwill, and nothing but this spirit can kill the demon which is carrying destruction and demolition among the so-called civilized nations of Europe.”100

The First World War to Independence

How can a person agitated by bombs, famine, and disease do the puja?101

The way to conquer fear is to worship Power.102

Much has been written about the decade after World War I in India: the Montagu-Chelsmford Reforms, which held out dyarchy as an intermediate step to self-governance, the repressive postwar measures of the Rowlatt Bills, and the massacre at Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar, all in 1919; the growing politicization of Indian Muslims, demonstrated in the early 1920s by the Khilafat movement to restore the Ottoman caliph; the rise of Gandhi as an all-India political leader and his recourse to satyāgraha as a political technique of nonviolent resistance, first tried in the Non-Cooperation movement of 1920–1922; Gandhi’s temple-opening movement for Untouchables; the popularity of C. R. Das (1870–1925), Bengal’s foremost nationalist spokesman, who led his Swaraj Party from 1922 and who spearheaded the Bengal Pact of 1923, which tried to forge links between Hindus and Muslims; and the growth of Hindu nationalism, with the founding of the Hindu Mahāsabhā in 1915, the leadership of V. D. Savarkar (1883–1966), and the creation of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) in 1925. Common themes in the political arena include increased urgency regarding the quest for independence from Britain and increased alarm on the part of certain Hindus and Muslims about each others’ political aspirations; this led both to conciliation and to the creation of strong protective communal boundaries. In the 1920s, then, one can speak of the first efforts to produce a “Hindu nation,” “an all-encompassing catholic national Hinduism overriding divisions of sect and caste.”103

In the Bengali papers in the early 1920s Durgā was importuned for her compassion in difficult times. Wrote the editor of the Ānanda Bājār Patrikā for 4 October 1922: “In the Pūjās we forget that we cannot speak, we have no land, no authority, no power, no royal glory. We forget that we are a race of servants, that the country has become a prison. We forget all this, but not the Mother’s love. That is why we see her smiling face piercing all our fears.”104 By 1923, the same paper was identifying broken Bengal as the Pūjā temple to which Durgā was invited. Then, employing an image from the first of the three stories from the “Devī-Māhātmya,” the author goes on to equate Bengal with Nārāyaṇa, lying asleep on the black shadow of suffering, the ocean of hopelessness, the serpent bed of domination. “Today please awaken Bengalis in order that they might save themselves from the pair of demons, Madhu and Kaitabha, which are domination and sycophancy.”105 This same theme is illustrated in a number of clever cartoons from the 1920s onward; Durgā is said to leave her temple for the streets, her weapons for compassionately open arms, and her elite patrons for her disconsolate children.106

The 1920s were momentous not only for the symbolic resonances of the Goddess but also for her Pūjās. Reacting both to a perceived need for Hindu solidarity in face of potential Muslim threat and to Gandhi’s exhortation to abolish Untouchability—ironically, a similar thrust toward unity but for opposite reasons—several Bengali Hindu leaders called for religious celebrations embracing everyone, from whatever caste or class background. Thus the birth in 1926 of the sarbajanīn, or “universal,” Pūjā, organized by locality rather than by clique, and open to all, regardless of birth or residence. For the first time, pandals, or temporary temples made out of bamboo or cloth, were constructed in public thoroughfares, alleyways, and cul-de-sacs and used as centers for people to come for darśan of the Goddess and her four children. The first such “universal Pūjā” was dubbed the “Congress Pūjā,” and was organized in Maniktola, in north Calcutta. The image of the Goddess was uncharacteristically unornamented and entirely militant.107 In 1927 one newspaper article explained to the public that these new festivals “will be celebrated in order to give facilities to Hindus of all classes and denominations without the least distinction of caste” “to bring about solidarity in the caste-ridden Hindu community.”108

Nationalists of the period who were jailed by the British often expressed their patriotism, even while incarcerated, by demanding the right to perform Durgā Pūjā. The most famous example of this is the Śākta-leaning Subhas Chandra Bose, who, after celebrating the Pūjā in Mandalay jail in September 1925, wrote to C. R. Das’s wife, Bāsantīdebī, “The Divine Mother is being worshipped today in many a Bengali home. We are fortunate enough to have Her in this prison also. The Mother probably did not forget us, and so it has been possible to arrange for Her worship even though we are away. She will depart day after tomorrow, leaving us in tears…. If the Divine Mother will make Her appearance once a year, I expect prison life will not be so unbearable.”109 Several months later he went on a two-week hunger strike in order to be compensated by the prison authorities for the expenses he had incurred in the worship.

After the Communal Award in 1932, the Untouchability Abolition Bill of 1933, and the Depressed Classes Status Bill of 1934, none of which pleased the Bengali bhadralok, the obsession with trying to forge a common identity, across caste lines, became imperative for Hindu leaders. “From the mid-thirties onwards, Bengal witnessed a flurry of caste consolidation programmes, initiated chiefly under the Hindu Sabha and Mahasabha auspices.” These included reconversion, or śudhhi, efforts; lobbying Nāmaśūdras and other very low castes to stop working for Muslims; enlightening Hindu zamindars about the necessity of separating Hindu from Muslim workers; constructing Hindu temples in villages; and introducing sarbajanīn Pūjā festivals.110

As might be expected, such communalization of politics, and of the Pūjās, led to tensions and even riots between Hindus and Muslims. “Festivals were a benchmark against which the changes in the local balance of power between competing communal groups could be measured,” writes Joya Chatterjee, who convincingly shows the degree to which Bengali Hindu and Muslim festivals in the 1930s and 1940s were public sites for the antagonistic display of community wealth, solidarity, and power.111 In his writings, Gandhi lamented that Hindus were playing music in front of mosques,112 and during the Pūjā season of 1926, in areas both west and east of the Hooghly River, the papers reported desecration of Durgā images and harassment of Hindu processions by brick- and bat-wielding Muslims from local mosques.113 Typically the quarrels broke out over street rituals—either Muslims celebrating Bak’r-Id by sacrificing a cow or Hindus playing drums as they processed their image of Durgā or Kālī either in front of a mosque at prayer time or during Muharram or Ramadan processions.114 The British responded by declaring that no one could be seen in public with a weapon, but it took some days for calm to return to the affected areas. The editors of the Ānanda Bājār Patrikā commented sadly on 19 October 1926, “[F]or the last five to six hundred years, Muslims have been joining in the Pūjā celebrations. In fact, Durgā Pūjā was not just a Hindu festival, but a Muslim one as well. But [now] such friendship has gone far away, and the country’s peace has been destroyed.” The writer assigned blame in all directions: to those whom he called the “new pirs,” responsible for stirring up communal hatred among Muslims; to the British, who did not exert themselves to keep the peace; and to Hindus themselves, whose cowardice in the face of the bricks and stones proved their weakness.

Hence by the late 1930s and early 1940s the Pūjās had shifted the focus of their reflective abilities: no longer perceived as a possible symbol to galvanize support in the struggle against the British (by this time Britain had lost the political will to hold onto India much longer), the festivities were now images, indications, signs of the times: mostly of the communal violence that would erupt at Partition in 1946–1947; but also of current events. In 1943, in the midst of the Bengal famine, a journalist in an article entitled Āgamanī invited, called, pleaded with the Mother to come home to save her children in their terrible distress.115

The communalization of politics in the 1920s and 1930s should be seen in a larger context. Indian towns during this period saw the growth of public arena activities through Britain’s gradual postwar devolution of power; as Nandini Gooptu phrases it, “the consequent expansion of representative politics and its flip-side, the need for popular political mobilisation, changed the entire nature of Indian politics.”116 Agitations, protests, political rituals, and the forging of alliances emerged as Indians sought to maneuver against imperial institutions on behalf of their own group interests. Such attempted strengthening of “the Hindu community” often led to anti-Muslim actions or rhetoric. Moreover, the phenomenon of the nagarkīrtan, or street procession, with large numbers of people marching through the streets parading their images or performing their vows and rites, was an innovation only of the 1920s, and resulted directly from the expansion and democratization of public arena rituals throughout India.117 Such public ostentation was also true of Muslim festivals, particularly Muharram.

This increased public-sphere activity also inflamed British fear of unruly crowds; police forces were enlarged to quell or deter communal violence at demonstrations, meetings, processions, and festivals, and preemptive curfews or arrests of suspected rowdies added to the perception of a dangerous, politicized street culture. Other regions outside Bengal also witnessed sarbajanīn-like festivals with widened access and scope: in 1924, the Allahabad Rāmlīlā processions included a live Brahman and sweeper sitting together, illustrating the putative integration of lower- and upper-caste groups.118 It is doubtful whether one should credit the “universal” Pūjās with true integration, however; in this vein I take Gooptu’s warning seriously, that we not presuppose actual social cohesion between elites and popular classes or think that communal conflict necessitates a completely shared sense of community identity.119 Indeed, as Anne Hardgrove also warns, “community” is “constituted by a set of practices, a series of ‘performances’ through which claims are made about collective and inter-subjective identities.” Yet “these claims may be contradictory, produced through relationships of power, and are open to resistance and contest…. The community, in other words, represents no consensus.”120 This is true in Bengal, from top to bottom, even among Hindus: neither the subordinate classes, whose presence was co-opted and necessitated by the new exigencies of political inclusiveness, nor the Hindi-speaking non-Bengali population, such as the wealthy and influential Marwaris, felt the Bengali Pūjās to be their own.121

Turning now to the British perspective on the period after World War I, British newspapers reported on the rise of the sarbajanīn Pūjās and on the communal disturbances that accompanied them; the British investigative police were wary of Bengali nationalists’ uses of seditious language and their ability to whip up anti-state fervor through recourse to religious, especially Śākta, imagery.122 However, the majority of Bengal’s British residents continued to think of the Pūjās in rather less political and, surprisingly, increasingly catholic terms.

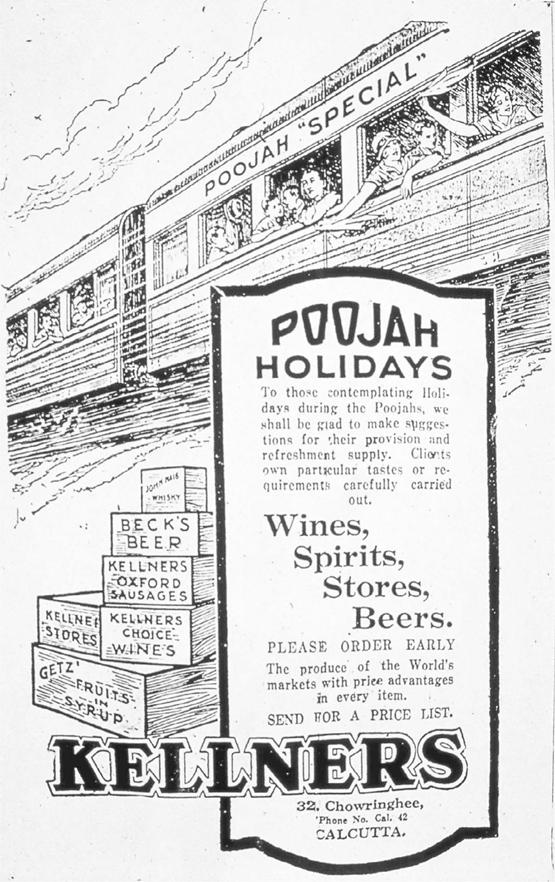

Just like the “average Hindu” who enjoyed returning to his village or, after the 1920s, decided to come from the village to Calcutta to sample the city’s entertainments,123 the “average Briton” still anticipated the Pūjās as a time of relaxation and travel (fig. 2.3). Indeed, the Pūjās were by this time an established industry. English newspapers introduced “Special Puja Holiday Pages” or “Puja Supplements” detailing holiday train schedules and fares to hill stations, seaside towns, and resorts; announcing seasonal concerts, theater shows, garden parties, and sport events; and publishing overviews of which stores were selling what for the festivities. After 1920 the English papers also began to include descriptive essays and human-interest stories about the holidays, the majority authored by Indian writers. Even the Englishman, that bastion of pro-British sentiment, began to show a more accepting attitude toward the Hindu festivals for Durgā and Jagaddhātrī, arguing that the Pūjās are like Christmas for the Bengalis, “offering hearty Pujah greetings to all our Indian readers,” lamenting the close of the Pūjā season, and complaining of “Puja-itis.”124

FIGURE 2.3. “Poojah Holidays.” Statesman, 1 Oct. 1929, p. 6.

In the late 1930s and 1940s, the British were taken up with World War II, the terrible famine in Bengal in 1943, and the last throes of planning for the transfer of power; the Pūjās command very little newsprint in papers of either community, except the stray comment on how the festivals have been curtailed by rain, blacked-out streets, economic problems, war, and famine. One Bengali monthly, Māsik Basumatī, includes in 1943 an essay modeled on a famous song to Kālī, “Śmaśān bhālobāsis bale” (“because you love cremation grounds [I have made my heart one]”). The author of the 1943 essay identifies the cremation ground not with his heart but with Bengal and asks his readers to shed their blood for independence and self-government from the bideśīs (foreigners).125 But the British, it appears, had ceased to fear such Śākta-derived nationalist symbols of anti-empire antagonism. What perturbed them more was the threat of communal riots. The Pūjā season after the Great Calcutta Killings, or Direct Action Day (August 16, 1946), was perceived as a potential stabilizer, if the British could police it properly. By September 30, 1946, in announcing a relaxation of curfew for the holiday season, the headlines were clear: “Government determined to see Pujahs pass off peacefully.”126

Pūjās in Post-Independence West Bengal

Peaceful Puja, Id Assured.127

Since 1947 the political situation in eastern India has changed dramatically. With no more British imperialists to oust, and a Communist-led government in West Bengal that has been virulent in its efforts to curb or even suppress communalism, how have the Pūjās fared? Is there any way in which they can still be said to mirror political events or express political aspirations?

The answer of course is yes, although in a changed fashion. The festivities still provide the impetus for nationalist sentiment, and the Goddess is still perceived by many as the foundation of the country’s strength (deś-śakti128).

In the years immediately after Independence, when violence had subsided, communal tensions somewhat abated, and prosperity partly returned, Pūjā organizers again gloried in the emancipation of the Mother; in patriotic zeal they decorated their pandals in the colors of the flag, hung pictures and created clay models of Vivekananda, Gandhi, Nehru, and Subhas Bose on the walls, and played “Bande Mātāram” in the background. One journalist in 1948 saw Gaṇeśa and Kārtik wearing Nehru caps.129 Such nationalism in the context of the Pūjās is, one might say, celebratory, self-congratulatory, and nostalgic, rather than exhortatory or revolutionary. It also builds upon a Śākta valuation of might, not a self-sacrificing exhortation to nonviolence. Said one Dr. Rameścandra Majumdār when inaugurating a Pūjā in 1951, “After Independence people are saying that our culture will be built up. But what is our culture? Not Vedic or Vedantic, but that built on Śakti-sādhanā; this is our uniqueness.”130 That the Pūjās are at heart a vehicle for the expression of muscle, prestige, and honor is shown through their patronage by soldiers and rulers: almost every year the Calcutta newspapers report on the traditional worship of Durgā by the Gurkha Rifles and the Assam Rifles, who vivify the Goddess with blood sacrifice and apply oil and vermilion to their weapons. And in spite of the outwardly anti-religious stance of the CPI(M) cadres, they too patronize the Pūjās, utilizing the occasion for the selling of literature and the disbursement of political favors.131

Of course, the British and local government aside, there are plenty of “others” for India to worry about, chief among whom are China and Pakistan. The Pūjā season in 1962 was full of patriotic fervor and lamentation; the same was true in October 1964, when China conducted its first atomic test: “China’s atomic explosion on this year’s Vijaya Dasami day—though coincidental—underlines, by a tremendous shock, the growing ascendency of the forces of evil and the retreat, as it were, of the forces of goodness and peace symbolized by the Divine Mother…. [W]e fervently hope that she will bring back those competitors in total destruction to sobriety and good sense before they have proceeded too far along the road to Calvary.”132 In 1965, during the Pakistani intrusion into Kashmir at the end of September, politicians asked people to pray to Durgā for national strength in the face of the “naked and wanton aggression by Pakistan.” “Pakistan and China are threatening to attack us … However formidable the aggressors might be, the people’s unflagging mood is that they will withstand and crush the enemies with the Mother’s blessings.”133 In 1971, during the birth pangs of Bangladesh, feelings of tremendous solidarity with East Pakistan caused pandal organizers to broadcast Sheikh Mujib’s speeches and sell his writings at their Pūjā stalls. In addition, East Pakistani refugees, living in camps in West Bengal, were given money to enable them to perform Durgā Pūjā in their traditional manner.

One of the chief elements that differentiates these types of politicized Pūjās from those in the colonial period is that the “others” or enemies are not in one’s midst and hence do not interfere with one’s processions or provide impetus for street fights, or worse. As mentioned above, the CPI(M) has been vigilant in policing the Pūjās, not only as a routine matter when they coincide with Id or Muharram but also when special national or world events occur that might lend themselves to communal, Hindu–Muslim unrest. Common compromises include assurances that Muslims will herd sacrificial cattle through specified routes only, and then quickly clean the refuse, and that Hindus will avoid blaring loudspeakers or planning procession routes near mosques. The police routinely mandate the cessations of Pūjā immersion rituals during Id or Muharram.

The West Bengal political atmosphere during L. K. Advani’s rath-yātrā for the “liberation” of the Babri Masjid in 1989 was tense, but although there were places in the city where bricks for the construction of the new temple to Lord Rāma were blessed, the local police reported with satisfaction that such rāmśila pūjās never occurred in the context of a Durgā Pūjā.134 In Pūjā season 2001, one might have expected the pandals or lighting exhibits to have reflected or represented the World Trade Center disaster. But CPI(M) workers prohibited artisans from sculpting the demon whom Durgā slays in the likeness of Osama bin Laden, and the bombing of the Twin Towers was almost nowhere depicted (but see p. 145 and figs. 5.4 and 5.5 below).