Politics and Religion in the Pūjā

Prologue: Jesus in a Hospital

Imagine that it is midnight, December 23, and you and your friends are strolling around your neighborhood.1 You have a map in your hand, prepared by the police, to guide you. You are looking for crèche scenes. Everywhere—on rooftops and building facades—neon lights brighten the sky with their colored designs. One depicts Santa sailing through the sky on his reindeer chariot. In another, candidates in recent election battles are heatedly arguing. Down the street you see a lighted display of a melting glacier forming a torrential river that sweeps away mountain villages. Your first crèche scene is in a school playground under a stunning thatch-roofed stable. Outside, the benign face of your city mayor welcomes you to the festivities on behalf of St. Paul’s Catholic Church. Three days ago the neighborhood was abuzz because he had inaugurated the nativity scene by placing Jesus in the manger. You approach. The holy family seems traditional enough, but the three kings look remarkably like the U.S. president, vice president, and secretary of state. This St. Paul’s crèche is apparently in fierce competition with that of the Methodist church, a few blocks away, whose sponsors support the opposition political party. There, instead of a stable, you see a replica of a makeshift U.S. military hospital in Iraq. In order to see the baby Jesus and his parents, you enter the building and pass by lifelike images of wounded men lying prostrate in beds. Fastened to the walls of the rooms are anti-war slogans and pictures of grieving parents. Back outside, you are handed an ad by a representative from AOL: Use the Internet to vote on your favorite crèche scenes, and win a sport utility vehicle!

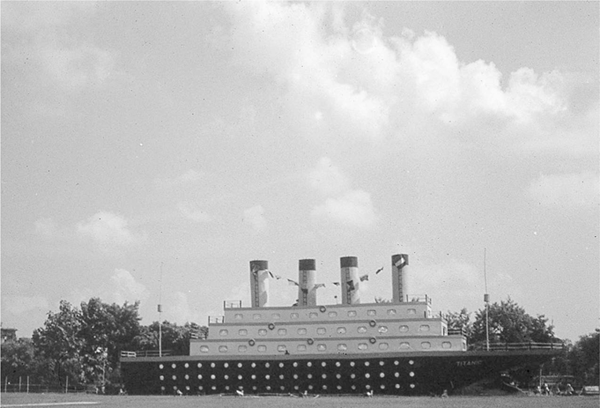

This is of course preposterous, in a United States setting. Public crèche scenes, decorated to reflect contemporary events, with the hope of attracting viewers and prizes, is not a part of American Christmas traditions. However, this is precisely what one finds in Bengali celebrations of Durgā, Jagaddhātrī, and Kālī. In what follows I describe these festivals and their fusion of religious, social, and political themes, and then try to account for why, and how, they have taken such a form. Keeping the chapter title in mind, is Durgā really on the Titanic? What does that mean? And why is it acceptable?

The Growth of the Public Pūjās from the 1920s to the Early Twenty-first Century

Anyone who has had the good fortune to experience recently (since 2004) the public Pūjās in Kolkata can probably not imagine that they were not always this way: extravagantly creative houses for the Goddess that exquisitely replicate actual buildings or structures, sometimes in mammoth proportions. And yet when I sought to determine through interviews when such pandals arose (“What were pandals like in the 1970s, for example?”), no one could quite remember. The overview of the developmental evolution of the pandals as presented below has thus been made possible only by archival work amid more than eighty years of Calcutta newspaper reporting and photography.

Apart from the continuation of private, elite home Pūjās, the nineteenth century was the era of bāroiyāri Pūjās. In 1820 the Calcutta Journal explained the mechanism of such celebrations—five to six Brahmans get together, form a committee, collect subscriptions, set up a “temporary shed,” construct an idol, and engage singers2—and the Rev. Alexander Duff, in 1838, attested to the prevalence of temporary images being made for ordinary people’s homes. But as yet there were no street festivities.3 All of this changed in the 1920s, when public festivals of the sarbajanīn variety, with their illuminations, temporary houses for the Goddess, processions and gatherings, and free musical entertainments, were initiated and celebrated with great enthusiasm. The newspapers of the time, however, seem to evince little interest in anything apart from the new iconographic styles of Goddess depiction, as discussed in chapter 4, and the illuminations in the streets.4 Indeed, not until the 1950s do the papers comment at all on pandals or their shapes, and even then the coverage is minimal; when pandals are photographed they are not labeled, which indicates that there was not yet any competition between named clubs.

What seems to attract most attention are the people chosen to organize and inaugurate the festivities, the outside illuminations, athletic performances, like lathi duels and boxing, and the associated displays inside or near the pandal. Prior to the late 1970s, if a group wanted to make a political or social statement, its members would typically decorate the inside of the pandal with hanging pictures or have an adjoining tableau of images reenacting a particular event. In 1952, for example, the Simla Byayam Samiti exhibition used clay figures and posters to illustrate the one hundred years from Plassey to the Mutiny; Indian Independence; the speech by Swami Vivekananda at the 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago; Gandhi’s death; and starvation.5 Clues to future direction are the film studio backdrops—temple scenes, mountains, lakes, and maps of India—placed behind certain images inside the pandal.6 The only descriptions or photos of pandals I have seen for the entire 1950s decade reference decorated gateways and columns.7

Looking at the Pūjā dates in the news of the 1960s and 1970s reminds one that the festivals are vying for coverage in an increasingly troubled world: in newspapers for the Pūjā dates in 1962, for example, reporters discussed Kennedy and a possible war with Cuba; bloody riots in Mississippi over the admission of the first “Negro” to the University of Mississippi; Nehru and India’s relation with China; and anti-Hindi riots in the South. In 1965, the Pūjās coincided with the Pakistani intrusion into Kashmir; fighting in Vietnam; and the Beatles. Early 1970s Pūjā reporting occurred on the same pages as news articles about Naxalites in West Bengal, the war between East and West Pakistan, and the continuing U.S. bombing of Hanoi. In 1976 Muhammad Ali beat Ken Norton on the eve of Durgā Pūjā, and Jimmy Carter defeated Gerald Ford at Kālī Pūjā. But even during such momentous events, the Pūjās continued their trajectory forward, for the 1960s saw several innovations: the police begin to publish “road maps,” showing where traffic was being diverted during the congestion of the Pūjās; the papers record crowds in the act of “pandal-hopping” to prominent named clubs (but give no description of the pandals’ shapes8); “information stalls” are set up adjacent to pandals by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) [the CPI(M)], the Jan Sangh, and even Maoist Naxalites9; and in 1966 some large structures introduce the custom of separate entrances for men and women.10 The first time one finds the effort to simulate a real-life structure is in 1969, when the pandal at 27 Palli, designed like the Mīṇākṣī Temple, is said to draw large crowds.11 But in the festivals throughout the 1960s and 1970s, even such modeled pandals appear quite crude in comparison with what one is used to in the twenty-first century.

Suddenly in the 1980s several new, and long-lasting, components enter the festivities: open competition between neighborhood committees; the mention of “big budget” pandals that are now dependent upon sponsorships by commercial companies; the replacement of mercury lights with neon lights in the outside illuminations; the open worship of the Goddess by military units such as the Assam Rifles and the Gurkhas12; and the increasing number of pandals now shaped as copies (ādalṭis) of real buildings or structures—Belur Maṭh at Calcutta, Paśupatināth Temple in Kathmandu, the Sun Temple at Konark, and the crash of Air India’s Kanishka jet, which broke up in mid-air in 1985. I can only find one example of a site replicated from outside India: the Olympic Coliseum in Los Angeles, from 1984. Though not expressed in external pandal construction, during this decade some Pūjās reflected political events; in 1984, Jagaddhātrī Pūjā coincided with the assassination of Mrs. Gandhi; several committee organizers, in all parts of the state where the Pūjā was celebrated, affixed photographs of her on their pāṇḍāl walls or positioned Mrs. Gandhi next to the Goddess herself.13 However, as stated in chapter 2, it is noteworthy that although Calcutta was host in 1989 to many blessing ceremonies (rāmśila pūjās) of bricks to be used in the building of the proposed new Rāma temple at Ayodhya, not a single one occurred in the context of a Durgā, Jagaddhātrī, or Kālī Pūjā.

All of these aspects and characteristics of the Pūjās burgeon in the 1990s and early 2000s. Almost every committee that could afford it employed builders to create a pandal in the shape of something beautiful, innovative, and reflective of Indian social or political life. By 2000 the creativity was dazzling: we find pandals representing recent events such as new Indo-Bangladesh train connections, the Amarnath pilgrimage attacks, the Bhuj earthquake, and the Nepal palace murders. At yet another site Durgā resides in a flooded village, complete with real stream and (not real) dead carcasses of animals; she is also welcomed into the Leaning Tower of Pisa, the Golconda Fort, a tree stump with an entrance portal, an Egyptian pyramid complete with scattered sand, Ajanta Caves (fig. 5.1), and Alibaba’s Cave, where the door opens to a spoken mantra.14 In 2006 one could visit Durgā in St. Isaac’s Cathedral in Leningrad, in one of Khajuraho’s temples, inside Lord Jagannātha’s temple chariot at Puri, in Vatican City, in the ruins of Harappa, and next to Swami Vivekananda at Vivekananda Rock in Kanyakumari.15 That the scope is as large as the world is indicated by a cartoon from 2001, in which a man says to his wife, in the Pūjā crowds: “I have seen all of India, now let’s go to America. Let’s start with the White House.”16

FIGURE 5.1. A Durgā Pūjā pandal shaped like Ajanta Caves. Muhammad Ali Park, Kolkata, September 1998. Photo by Rachel Fell McDermott.

The most recent innovation in pandal construction occurred in 2004, with the “Theme Pūjā”—that is, a total package where the lighting displays, the pandal shape, and the Goddess’s attire or physiognomy cohere in the representation of a single theme, whether artistic, social, media-derived, or crisis-related. This development carries forward the desire for accolade and crowd-dazzling that had been steadily growing since the 1980s: already pressured by the need to introduce novelty (abhinabatva)—“If we don’t think up something new every year, people won’t take it. And sponsorships won’t come, either,” said an exasperated chair of one Pūjā committee in 2006—the move toward overall coherence is meant to bag prizes, wow competitors, and charm the darśan-seekers, who are now called rasiks, or those who are expert in aesthetic taste.17 Examples abound: a pandal designed like Berlin’s Olympiastadion, where Mahiṣa is sculpted in the likeness of Zinedine Zidane, the French soccer star, head-butting the lion, while Gaṇeśa acts as the referee18; a pandal made of more than ten lakh pencils, in the interior of which are panels portraying people committed to education and the development of writing19; a spacey-looking ethereal Durgā arriving from above into a spaceship pandal and blessing the illiterate asura with the light of knowledge20; an Egyptian theme, with Durgā in the form of Isis, Mahiṣa as the god of death, and her four children as other Egyptian gods, all inside a pandal shaped as the Luxor temple, decorated with ancient Egyptian art21; and a host of pandals where the coherence is achieved through the raw materials chosen to construct the pandal and the Goddess: special wood brought from Manipur; silkworms, silk, and cocoons; even postage stamps. In 2008 the Suruchi Sangha in New Alipore decided to focus its pandal on Assam. Five artists toured Assam for over a month and came back ready to make copies of various temples, including Kamakhya, decorated with Assamese handicrafts. Durgā was placed on a platform in the mountains. Outside the pandal, stalls sold Assamese food and musicians played Assamese music.22 Other pandals from 2008 include the theme of the Goddess’s third eye (the pandal was constructed in the shape of a huge eyeball, and darśan-seekers, once inside the ocular structure, could pledge to donate their eyes after death to the blind23); and the dense forests of the Sundarbans, from which fallen wood was brought both to create and decorate the pandal and to carve the image of Bonbibi, the local forest goddess.24 In 2006 two pandal committees made a splash when they hosted press conferences, where each screened a short film to explain their focus and their creative process.25

Along with the increased complexity and size of the community Pūjās, the scope and cost of the displays have also increased. Although comparative statistics are hard to assess with accuracy, it seems that in Kolkata alone the number of street pandals has grown from about six to seven hundred in the 1950s to about 1,300 in 2008 (the number of permitted street pandals has remained constant at least since 2000). In 1953 a typical sarbajanīn Pūjā cost anywhere from Rs. 4,000 to Rs.14,000, where the lion’s share of the expense went to the outside illuminations and lighting shows. In 1976 artisans charged Rs. 3,000 for a good-sized image; in 2008 the price was Rs. 20,000. The six top-notch committees in 2004 spent Rs. 5 million each, for their total packages. Hence the Pūjās are big business, and connect major cities, especially Kolkata, to areas throughout the state; local industries that the festivities support are legion, from the growers and conveyers of lotus flowers, and traditional Muslim wig-makers and drummers, to the coolies who travel into the cities to carry images from the artisans’ districts to pandals or homes, and then from there to the immersion sites at the conclusion of the festival.

The same growth is true for Jagaddhātrī, especially in her home territory of Hooghly and Nadia districts. The number of Central Committee–approved Pūjās in Chandannagar has risen steadily every year since 1956: in 1968 there were 44, in 1977 89, in 2002 132, and in 2008 142.26 Only 64 of these 142, collectively taking 240 trucks from four zones of the city, are permitted to join the śobhāyātrā to the river. Krishnanagar has its own procession traditions; first, each of its 126 Pūjā committees takes the ghaṭ, or pot of water that officially houses the spirit of the Goddess, to the Jalangi River for immersion, and then, later in the evening, the committees return to the river with their images. All processions must pass by the Nadia Rāj estate, where at one time the rājā and his wife viewed the images and awarded prizes.27

Hence, as commercial ventures that capitalize on human enterprise and creativity, the Śākta Pūjās as a unit have burgeoned since the 1920s into a festival period that dwarfs all others in allotted vacation time, hoopla, cost, grandeur, and Bengali pride.

Prestige and Politics in Pūjā Contexts

Mine Is Better than Yours

Two interrelated aspects of the Pūjās deserve closer scrutiny: the craze for competition, common to both old family and street pandal settings; and the intersection, particularly in the pandals, of religion, social concerns, and political commentary.

Rivalries come in many forms. As we have seen in chapter 1, for the monied classes of Pūjā organizers, this is a muted, rather polite battle. I interviewed the heads of about fifteen such aristocratic families in Calcutta in 2000, and most were very aware of the other traditional Pūjās in the city, ranking their own celebration against them in terms of age, adherence to custom, expenditure, and inherited prestige. Although there seem to have been rivalries between such families and the organizers of the “new” bāroiyāri Pūjās in the nineteenth century, the former disdaining the latter as “low and common beggars,”28 by now the community festivities are so accepted and beloved that the chief rivals of the aristocratic classes are each other. Some interviewees told me that they scour the newspapers at festival time, seeing how often their family celebration is written about, in comparison with those of their peers.

Matters are more urgent and more extreme for the soldiers in the public contests, where the language of war pervades all aspects of the festivities. Sarbajanīn Pūjā organizers freely admit that they want to fight, beat, and trounce their competitors, and many of them employ “think-tanks” to come up with new ideas and succeed in the “ṭāg ab oyār” (tug of war) between pandals. Novelty, size, the ability to confer notoriety: these are the coveted values. Organizers approach artisans and lighting experts who have won prizes in the past. They invite celebrities—politicians, authors, sportsmen, movie stars, and even national figures such as the now-late Phoolan Devi and Mother Teresa—to inaugurate their Pūjās. Multinationals such as Bata, Coke, Goodrich, Heinz, Hindustan Lever, Maruti, Pepsi, Phillips, Proctor and Gamble, and Whirlpool donate money to particular pandals with the stipulation that their products be advertised near the gates or in recorded songs played on loudspeaker. In the struggle to garner such company sponsorships, Pūjā committees defame one another, and during the celebrations they anxiously watch the papers. Who is drawing the biggest crowds? Who is giving most to charity? Who pays the bigger electric bills? How do we stop spies from rival committees stealing our ideas? In 2006 certain Pūjā clubs began handing over the construction and running of their pandals to event management companies, in the hopes of further professionalism, and hence notoriety. There has even been physical violence and death associated with inter-Pūjā rivalries.29

Prizes—which bestow funds but, more importantly, prestige—form the coveted material core of the Pūjā industry. Begun in 1969 by the West Bengal State Tourist Bureau, originally the conferral of prizes was designed to increase Pūjā development for the sake of tourism; in the same year the bureau also announced its first tourist launch to watch the immersions in the river.30 By 1975 the Public Relations and Information Department of the Government of West Bengal was awarding a total of eight prizes: three for the best overall sarbajanīn Pūjās, and one each for the best traditional image, best solemnity and atmosphere, best decoration, best new forceful image, and best traditional rituals.31 By 2008 so many different prize-awarders had come forward, ranging from companies to newspapers to charities, that it has become difficult to keep count. The newest prize categories include the best apartment building Pūjā (Bāḍīr Serā Pūjā), since 2001; the best priest (to be judged on his correct pronunciation and ritual precision), from 200232; the most child-friendly in safety and accessibility, since 200233; the most “green,” from 2004;34 and the most caring. In 2006 the Telegraph newspaper offered the distinction of a “True Spirit” Pūjā badge to pandals that provide a caring, clean, and fire-proof atmosphere, together with safe drinking water, toilets, and a special gate for the handicapped.35 In general, the mania for prizes, together with increasingly stringent police regulations, in order to manage the crowds and ensure safety, have encouraged an upscaling of the festivities, as no committee wants to have its permit rescinded or to receive negative publicity.36

There are as yet no major prizes for social outreach, but many committees band together to raise money for worthy causes, like flood relief, lifesaving operations for poor children, and gifts of food or new clothes for the city’s marginalized. Such generosity underlines one of the fault lines of the Pūjās: although ostensibly created in their public form in the 1920s to appeal to both rich and poor, the festivities are not truly universal. The newspapers publish photos of street families or people living inside abandoned drainage pipes, unable to join the festivities or being fed once a year by a Pūjā committee. “Puja is another world to us,” said one such person to a Hindustan Times reporter in 2001.37 The pandals themselves might decorate their interiors with displays exhorting kindness to the poor, ill, or out-caste, but in spite of some integrative success stories there are as many reports of prejudice, fear, and refused inclusion in Pūjā committees or pandals.38 Those who do minister to the needy, however, use their altruism as yet another weapon in their arsenal of victory over their rivals.

Not simply neighborhoods, but even towns vie with one another for recognition. Krishnanagar and Rishra have both attempted to supercede Chandannagar, the traditional star of Jagaddhātrī Pūjā, Krishnanagar through the financing of a Mumbai business, which has started a Jagaddhātrī Web site and announced the awarding of prizes, and Rishra, which extends its Jagaddhātrī festival three days after the conclusion of its rival’s. Even Pūjās appear to do battle. Naihati, an hour by train upriver from Kolkata, tries to prove, by its gigantic Kālī images over 50 feet high, that its Kālī Pūjā is superior to Kolkata’s Durgā Pūjā.

To me one of the interesting types of local sparring—some of it deadly—is political. The Communist Party of India (Marxist) has been in power in the state of West Bengal uninterruptedly since 1967, for thirty years without significant political rival. In 1997, however, a woman named Mamatā Banerjee founded the Trinamul Congress, or Grassroots Congress, in order to overthrow the Communist stranglehold. To this end she has been willing to ally herself with anyone powerful; until April 2001, for instance, she was a minister in the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)–led government, responsible for railways and transportation. After the embarrassment over the Centre’s bribery scam in March 2001, Mamatā quit the BJP government and formed an alliance with the West Bengal State Congress Party. In 2008, as a result of her anti-industrialization protests, Tata Motors withdrew its proposed Nano car factory from the state, exacerbating the already acrimonious relations between Mamatā and Buddhadeb Bhaṭṭācārya, the state’s CIP(M) chief minister (see fig. 5.2). Mamatā’s alliance with the Congress in the 2009 elections caused the Left Front to suffer its worst setback in years; in fact, it did not retain a single parliamentary seat in Kolkata. Moreover, in summer 2010 the Trinamool Congress inflicted a crushing blow to the ruling Left Front Party in the Kolkata civic elections, as a result of which Mamatā predicted that she would sweep West Bengal in the 2011 Assembly elections. In general, then, Mamatā’s party threatens Communist hegemony in Bengal, and since the year 2000 the state has witnessed politically motivated mutual violence, property destruction, and evictions; in such contexts, the ability to hold Pūjās is a symbol of peace and normalcy that is coveted by both parties in the districts under their jurisdiction.39

FIGURE 5.2. A Durgā Pūjā pandal in the shape of a Tata Motors factory, after it was stopped from producing Nano cars. Kolkata, October 2008. Photo by Jayanta Roy.

In Kolkata, where there has been posturing but less violence between Communists and Trinamul workers, pandals organized by Trinamul members sport pictures of their leader, sell her literature, and festoon their displays with political slogans. Some of the big-budget Pūjās are backed by politicians close to Mamatā. They not only rival one another, but in particular enjoy attempting to humiliate the “Congress Pūjās”—even though after 2009 the Congress Party is the third, and weakest, claimant for power in the state.

It is noteworthy that there is no Communist Pūjā, no pandal allied with a name in the state government. This is because, strictly speaking, the Communist ideology does not permit an acknowledgment of religion, devotion, or grandiose spectacles of piety funded by the elite.40 Even now, Communist Party members are publicly admonished against taking part in the Pūjās. But there is also a countervailing trend. After the mid-1990s, perhaps because Jyoti Basu was nearing retirement, valued pragmatism, or desired to combat Mamatā Banerjee on her own turf, he began practicing lenience and even indulgence toward the Goddess. “As I grew up, party ideologies alienated me from the simple fun of Durga Puja. For a very long time, I did not actively take part in celebrations. Things are different now. I have grown old and the memories come rushing back.”41 Since 1995 I have seen newspaper articles and even photos of CPI(M) chiefs inaugurating pandals, offering flowers to the Goddess, and wandering the streets of their neighborhoods, enjoying the season’s delights. This is in addition to the over 4,500 seasonal bookstalls, strategically placed throughout the city, for the spread of Marxist teachings. One CPI(M) minister explains that the political costs of turning down requests to cut ribbons at the festivals can be very high. “Don’t forget these are the people who vote for us and stay with us year round as many of the puja organizers are our workers,” he told a newspaper reporter bluntly.42 While the new breed of liberal Communist justifies his behavior by claiming that the Goddess is the śakti of Communist rule, that Durgā Pūjā is a secular, national, artistic festival, not a religious one, that Durgā Pūjā is a form of “social communism,”43 or even that “theme pandals” can convey the truths of communism (one committee in 2006 illustrated the CPI(M) slogan, “agriculture is our base, industry our future,” by erecting a factory and a farm in the same pandal structure44), many others censure what they perceive to be a sellout of the Party to hypocrisy, opportunism, and social pressure.45

The urge to best rivals through the creative use of the festivities extends beyond West Bengali contexts. The West Bengal State Tourist Bureau, continuing its efforts to project Durgā Pūjā as a national and even international visual event, has put together a Kolkata Mahotsava five-star, five-day package of fun and excitement that is aimed at placing the festival in the same league as the Mardi Gras of Rio and the Carnival of Goa.46 We return to this theme below.

Before leaving the topic of rivalry and challenge (even Bengali newspapers utilize the transliterated word “cyālenj”), it is important to note that competition based on the quest for novelty inspires nostalgia for the simplicity of old, which is often replicated in an “authentic” manner that ironically feeds the revival of traditional artisanry. Starting in 2006, I have noted the use of the word “Bāngāliyāna” in characterizations of the craze to go back to one’s cultural roots in the creations of pandals and their designs. Committees search out and bring to Kolkata folk or tribal artists, who weave their traditional bamboo or shape pots with special Krishnanagar clay, in situ, on the pandal site. Other committees hire art college graduates or even professional filmmakers in order to create their pandal sets; they also secure cinematographers to design their outside illuminations. Such realistic, professional efforts toward inculcating nostalgia, even if nostalgia for a way of life never experienced by the onlooker, Arjun Appadurai reminds us, is a central theme of modern merchandizing: “The much-vaunted feature of modern consumption—namely, the search for novelty—is only a symptom of a deeper discipline of consumption in which desire is organized around the aesthetics of ephemerality.”47 The more outlandishly gorgeous and, to some, garish the pandals become, the more the newspapers are filled with poignant, longing reminiscences of “the Pūjā Days of Old,” when simplicity and faith supposedly reigned.

And yet very few Bengalis, I infer, would want actually to go back to the simple pandal structures of the 1950s or lose the carnivalesque enjoyment of the total event that grips the state during the festival days. And nor, as we shall see below, was there probably ever a time when competition was absent from the atmosphere of the Pūjās. Indeed, I would claim that Bengali Goddess worship is inextricably bound up with competition, be it artistic, social, or political. A few years after Independence, in the midst of the Nehruvian five-year plans, one newspaper commentator, worried about what would happen to the Pūjās in the face of increasing industrialization, suggested that the state government should take over their sponsorship. He obviously need not have worried about the drive of private enterprise.48 Said an astute observer thirty years earlier, in 1924, noting that even Indian Christians and Brāhmo Samāj reformers were moved by the festivities, “You cannot underestimate the power of Durgā Pūjā on a Bengali!”49 One is practically compelled to join the fray.

Durgā on the Titanic

The second striking element of the Bengali Śākta Pūjās is the manner in which the street festivities act as barometers of social and political events and controversies. To be sure, Durgā, Jagaddhātrī, and Kālī are often installed inside pandals that look like temples or shrines, and the associated lighting displays frequently depict scenes from religious texts. One can see woodcuts, paintings, or lighting shows depicting Durgā’s akāl bodhan, or untimely awakening, when Rāma entreated her help in autumn before his war with Rāvaṇa; her war with Mahiṣa; and the dream in which Jagaddhātrī appears to Rājā Kṛṣṇacandra Rāy in the mid-eighteenth century and orders him to establish her worship. Religious scenes are not confined solely to the Śākta sampradāya, however. Equally popular are illustrations from the Rāmāyaṇa and depictions of Kṛṣṇa’s play with Rādhā.

Most temple-pandals are what is called “kālpanik,” or imaginary, but some, as seen above, are copies of actual temples—all magically transported to the streets and alleyways of Bengali towns. Other sorts of pandals are those which simulate some natural environment, such as a Bengali village or a Rajasthani desert (with two camels shipped in especially for the occasion); those which replicate civic buildings, locally important sites like Kolkata’s Victoria Memorial, distinguished buildings in other parts of South Asia, like the parliament building in New Delhi, and eminent places in Europe or America, like Buckingham Palace, the Eiffel Tower, and Harvard University; and those which parrot some theme or image from the popular media. I have seen goddesses housed in a huge mailbox, a computer, a house of cards, and, of course, the Titanic (fig. 5.3). This was all the rage in 1998, after the release of the blockbuster movie, and every Bengali city of any size could boast at least one ocean liner in its precincts.50 The same was true of Jurassic Park dinosaurs, soccer and cricket stars, and even Harry Potter’s castle.51 The subjects of the neon lighting vary with the whims of the time. For children there is Humpty Dumpty, Mickey Mouse, Godzilla, and vampires. For larger children and adults, the Hindi version of “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?,” and the Olympics.

FIGURE 5.3. A Durgā Pūjā pandal in the shape of the Titanic. Salt Lake, Kolkata, September 1998. Photo by Rachel Fell McDermott.

Disasters, accidents, and social problems are also popular themes for pandal designers and electricians. A group in Calcutta made the floods of 2000 in West Bengal the center of their pandal, depicting homelessness, lack of clean water, and the threat of flood-borne poisonous snakes. Too, the hijacked Indian Airlines plane at Kandahar in 2000 became a shelter for Durgā and her family, who were—like the actual trapped passengers—unable to see outside during the course of their confinement. Other themes of this ilk are the 1999 sinking of the Russian submarine Kursk and the crash of the Concorde in Paris in 2000. Mother Teresa and Princess Diana died all over again in the lighting shows of 1998, and several organizations have used the festivities as an occasion to raise consciousness about women—in particular, dowry abuses, child marriages, and bride-burning.52 Other pandals advertise the necessity of wildlife preservation (one 2000 pandal depicted Durgā as a tree, crying), the problem of political corruption, and the fight against disease.53 Two of my favorite reflections of popular culture are lighting shows, one from 1995 in which a fat Gaṇeśa drinks milk, and another from 1999 in which Bill and Monica carry on. I have even heard of, but never seen, a Durgā whose face was Monica’s.54

And then there are the nationalistic and patriotic pandals and lighted scenes. Although politics was reflected inside Pūjā pandals in the early to midcentury—in 1939 Gopeśvar Pāl apparently placed Durgā against backdrop that resembled a World War II battlefield55—whole pandals reflective of political themes made a splash only really in the 1990s. In 1991 such structures depicted the Gulf War and the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi, in 1995 the skirmishes between India and Pakistan in the Siachen heights, and in 1999, Kargil. For those wanting to experience the battles on Tiger Hill, one only had to go to Shealdah Athletic Club in Calcutta, where Bofors guns sounded in the background and Indian soldiers resisted Pakistani shelling, or visit Santosh Mitra Square to see a replica—160’ high, 140’ long, and 80’ wide—of the INS Vikrant, India’s aircraft carrier, equipped with an MiG fighter plane and a Chetak helicopter. In 2001 Durgā was still in Kargil, seated on a Bofors cannon in a mountain cave and surrounded by army personnel and dead bodies. She can also be depicted more symbolically—as Bhārat Mātā, as a map of India, or as residing in a map, with India at its center. In these exhibitions, the best way to indicate one’s “enemy” is to give Mahiṣa, the demon killed by Durgā, his likeness. Demons of recent years have been Nawaz Sharif, the LTTE chief Veerappan, Fiji’s George Speight, and even Bill Clinton and Tony Blair. Although not everyone approves of such patriotic and congratulatory propaganda at Pūjā time, I have seen or heard of very few groups choosing to criticize the prevailing sense of national pride through the medium of such pandals.56

Interestingly, although one might have suspected that the bombing of the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in the United States would have provided ample scope for both lighting displays and creative transformations of Mahiṣa into bin Laden during the 2001 Pūjā season, such was not tolerated by the CPI(M), whose cadres expressly prohibited Pūjā committees and artisans from creating any human representation of the disaster that might stir up communal discord in the state. Lighting shows and even an occasional pandal structure were permitted to depict the crash of the planes into the World Trade Center (fig. 5.4), but artists who began to sculpt Mahiṣa in the likeness of bin Laden (fig. 5.5) were ordered to destroy their work because of its sensitive nature (sparśakātar biṣay). Even with such preventative measures, however, Hindu–Muslim tensions were palpable in the closing months of 2001. The implication of such proscriptions appears to be that Pūjās may reflect delights, concerns, or problems common to all, but that Muslim feelings (manomālinya / manakaṣākaṣi) must be protected from perceived slight.57 Post-2001 nationalist pandals have concerned themselves with terrorism, not only by depicting Mahiṣa, for example, as a would-be suicide bomber, with a gas cylinder strapped to his body,58 but also by strengthening police surveillance squads in the streets.

FIGURE 5.4. Plane crashing into the World Trade Center. Illuminations at the College Square pandal. Kolkata. Hindustan Times, Kolkata, 22 Oct. 2001, p. 3.

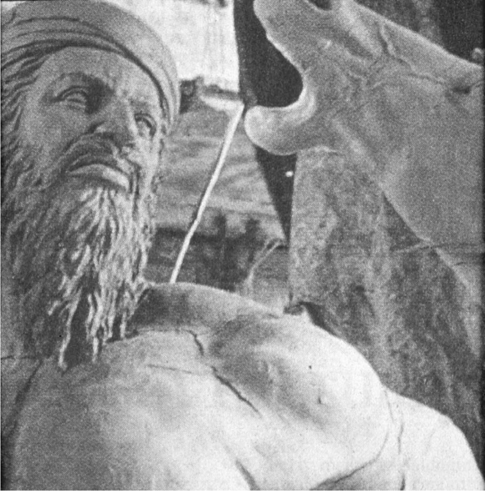

FIGURE 5.5. Mahiṣa in the shape of Osamabin Laden, before he was smashed. Hindustan Times, Kolkata, 26 Sept. 2001, p. 3.

The association of Durgā Pūjā with social, national, and patriotic concerns is reinforced in the public sphere by seasonal newspaper cartoons that depict Durgā in battle with various evils. In 1962 she is being chased by five bull-Mahiṣas, bearing the titles Casteism, Corruption, Communalism, Linguism, and Disintegration; in 1984 Mahiṣa is inflation; in 1987 the demon swims ahead of Durgā and her children in the midst of a flood to reach the relief supplies first; and in 2001 someone approaches the Goddess, sitting at a desk, and informs her that there are two new demons for her to combat: the Twin Towers tragedy and the threat of anthrax.59

Making Sense of the Melee

To recapitulate: the two aspects of this public religious festival season that appear to be most prominent are competition and the exuberant embracing of sociopolitical themes. Certainly there are a few analogues in the history of Western holiday celebrations—for example, department store rivalries at Christmas time in late-nineteenth-century Britain and America—but there is something distinctly surprising about these Pūjās, especially if one does the mental exercise I suggested at the outset. How then to explain, or trace the lineage of, these aspects of the Śākta Pūjās?

The Fate of Aristocratic Competitiveness

The first component—the Goddess as an occasion for battle over prestige—is not hard to understand, given the context of the festivals’ inception. None of them, as we have seen in chapter 1, is very old. We have evidence for their performance only as far back as the late sixteenth century, and from the very beginning they were sponsored by the wealthy—landowners and rent collectors under the jurisdiction of the Mughals and then the British—who resorted to them as signs of status and power. Ever since the Gupta period, Durgā Mahiṣamardinī has been associated with royalty, and the early Bengali landowners adopted her public worship as a substitute for an aśvamedha, as prescribed in the medieval Devī Purāṇa.60 By the early nineteenth century Britons were commenting on the bellicose nature of Pūjā sponsorship. “The natives have given themselves up to unlimited extravagance in all that relates to their public festivals, vying with each other…. Calcutta is the arena in which the various combatants for fame, assemble to adjust their claims; and it is astonishing to behold the immense sums which are annually squandered in order to acquire a name, and to attract ephemeral popularity.”61

Competitive feelings carried over even into the newly democratized forms of the festival, the bāroiyāri and sarbajanīn. A Bengali spoof from 1852 describes the Pūjā frenzy and then concludes poignantly: “[A]fter it’s all over, people discuss, ‘whose image was best?’ or ‘who had the best clothes?’ or ‘who had the best arrangements?,’ but no one asks, ‘whose bhakti was best?’” 62 The famed historian Jadunath Sarkar, thinking back to his childhood in the 1870s, described the rivalry within villages over their boat immersions, each family trying to outdo the others, even in terms of the music played as the Goddess was being lowered overboard.63 The new sarbajanīn format also gave tremendous new scope for creativity and rivalry. For the constituents of the sarbajanīn Pūjā were now “Everyman,” whose pockets could be plumbed for subscription money and whose entertainment tastes had to be satisfied. What we see, then, is a widening of sponsorship and audience, but the same opportunities for prestige, and hence the same scope for inter-Pūjā competition.

Such rivalry, and its changes in outward expression as the Pūjās devolved from the hands of the zamindars to those of the middle class, can also be placed in a larger comparative framework. Scholarship during the past three decades on the emergence of the consumer market in Europe—particularly France and England—indicates that similar paths were traveled in societies where an aristocratic ethic of taste and consumption gave way, though revolutions of swords or industry, to bourgeois values. The nobility, who were close to the monarch and wanted to remain that way, vied with each other in the acquisition of furniture and tapestries for their stately mansions and in the display of courtly politeness, taste, and restraint. Imitation of the king or queen and the maintenance of traditionalism were the keys to honor and social standing, and noblemen outspent themselves, often to financial ruin, in their pursuit.64 Holiday festivities, such as masques and Christmas celebrations, were encouraged by both monarch and nobility as occasions not only to show off their own wealth and prestige but also, by allowing the “public” a time of feasting, revelry, and even antinomianism, to undergird social order and royal authority.65

After the French Revolution in France and the victory of Puritanism in England, when the aristocracy lost its financial and feudal privileges, abandoned its control over public rituals, and even suffered exile or execution, the focus of economic activity switched to the cities and to the bourgeoisie, who in the eighteenth century in both France and England were the prime beneficiaries of the Industrial Revolution and the increased prosperity and mass-produced goods it generated. For our comparative purposes here, the two chief characteristics of this democratization of culture, in France and in England, were, first, the fact that the upper middle classes continued, like the aristocracy before them, to vie with others in their peer groups. To use the words of Rosalind Williams in her study of eighteenth-century France: “The social terrain was leveling out. Instead of looking upward to imitate a prestigious group, people were more inclined to look at each other. Idolatry decreased; rivalry increased.”66 People consumed conspicuously, using goods as symbolic markers to new status and power, but not—and this is the second useful comparative point—in the manner of the nobility before them, whom, after all, they had swept away. No, the new middle classes did not emulate the specific lifestyle patterns of the old nobility—patterns in which a closed, traditional set of prized goods and codes of conduct, patterned on those of the monarch, were the basis for social competitiveness. However, certain general characteristics of the noble lifestyle—luxury goods, leisure activities, and a “culture of refinement”—were desirable, even the object of middle-class nostalgia, and all of these were undergirded by an insatiable need for newness. Colin Campbell, in his brilliant study of the roots of modern consumerism and in particular of its unquenchable thirst for novelty, sees in the very foundations of Puritanism itself an assertion of the individual, a romantic longing for unfulfilled ambition, which lends itself to mobility, initiative, and the quest for innovation. This sensibility, he says, combined with new opportunities for variety through mass production, created the conditions for modern forms of mass consumer appetites.67

Studies of medieval to modern urban Indian economies reveal similar trends. The transition from courtly rule to societies governed more by mercantile elites occurred at different times in different Indian states, depending on the impact in their regions of Mughal and then British power, but one can trace a common pattern of assimilation by the nouveaux riches to courtly expectations of consumption. C. A. Bayly discusses such lavish expenditures by North Indian trading communities in the late eighteenth to late nineteenth centuries, noting that these often theologically ascetical (and Vaiṣṇava) merchants justified their opulent displays of wealth because they were occurring in overtly religious contexts.68 Sandria Freitag, also writing about North India, finds the same devolution of power from the courtier classes in the eighteenth century to the Hindu merchants and their allies in the nineteenth, but notes that because the Raj restricted free access to state institutions, these new leaders frequently resorted to the only domain left to them—what she calls “public arena activities,” such as public festivals and charitable functions—to demonstrate their status and prestige.69 The public arena, then, “the realm in which status had come to be defined,” “provided a structure through which … social and religious competitions could be expressed.” “The style of Hinduism most characteristic of revivalist and merchant-dominated cities quite consciously aimed at public time and public space.”70 For Rajasthan, Lawrence Babb analyzes the ways in which Rajasthani merchants overcame the disjunction they felt between the courtly Rājput norms of ostentatious spending, which in some sense they were attempting to emulate, and their own ethic of resource “husbanding”;71 and for south India, Joanne Waghorne notes that the mercantile period there began with a new round of temple building—not by the royal houses, but as a result of new merchant wealth and control, “fully part of a global interchange of goods and people.”72

Bringing the discussion back to Bengal, one can see some parallels. Before the Permanent Settlement Act of 1793, the mostly Hindu zamindars under the nawābs and then under the British imitated and fought with one another to gain the favor of their Mughal and East India Company overlords. They had more freedom of cultural expression than did the nobles under Louis XIV or Queen Elizabeth I, since they had no Hindu king providing them with a behavioral model, but it is arguable that they had much less political and social maneuverability. In any case, as argued in chapter 1, they sponsored religious festivals with great pomp, establishing a uniform model that is still today followed by their financially diminished heirs. In Bengal the aristocracy was not killed or forced out of power, but squeezed into financial bankruptcy. As soon as the sponsorship of the Pūjās was taken over by larger groups of successful merchants, banyans, and urban landlords after 1793, its character changed. Still the site for intense rivalry between Bengalis of more-or-less equal status, such rivalry now began increasingly to rest on the endless search for originality and novelty. After the revolution of the “universal” Pūjās in the 1920s, the base of sponsorship widened still further, opening out from the control of elite families to the shared, more democratic, and more politicized patronage of the middle class. While it is beyond the scope of my project here to delineate in a Campbellesque fashion the historical foundations of such an openness to novelty, one can say, generally, following Walter Benjamin and others, that mass production releases art from ritual into politics, from elite contexts into a display culture, where the exhibition of novelty is valued over the repetition of cultic rites.73

What one sees, then, in the streets of Kolkata and other Bengali towns today are modern forms of competition that stand squarely upon those derived from the eighteenth-century zamindars. And all such rivalries, whether zamindar or middle class, bespeak a more global phenomenon: the use of goods, behaviors, and special occasions to mark and claim status.74

Accounting for the Political, Looking for Analogues

Here we turn to the second phenomenon, the use of the Pūjās as arenas for the voicing of sociopolitical concerns. How is one to interpret this? Here I look at six different vantage points: Śākta theology; the history of the festivals themselves; the tradition of satire in Bengal; the impact of economic liberalization; the family resemblance between the Bengali Pūjās and other, similar festivals in India; and the parallels between the Pūjās and festivals outside the subcontinent, such as carnival.

Theologically speaking, the mixing of the sociopolitical and the religious is not a problem at all, for we know that from as far back as the sixth-century “Devī-Māhātmya,” Durgā is the Goddess of both bhukti and mukti, enjoyment and liberation.75 Śāktism values the world and looks for the divine within it; as such, the centrality of Durgā, Jagaddhātrī, and Kālī to rituals of opulence and sociopolitical relevance seems appropriate. We also know, to put it very generally, that the mixing of religion and politics has always been characteristic of Indian history; moreover, “the very idea of Indian secularism is ‘equal respect for all religions,’ thus encouraging religion in the public sphere as a repository of cultural legitimacy.”76 Americans might not be able to countenance their president as one of the three kings in a neighborhood nativity scene, but this speaks mostly about their monotheistic upbringing, separation of church and state, and sense of the inappropriateness or even blasphemy in combining sacred and secular in iconic depiction.

A second method of approaching the cosmopolitanism of the Śākta Pūjās, this turning outside to other parts of India and the world for ideas to enhance the Goddess’s worship, is to look, once again, at the history of the festivals. The original sponsors of the festivities, the landowning zamindars who curried favor with the British, filled their opulent houses with foreign objects and entertained their British guests at Pūjā time with English songs, even bagpipes and “God Save the King.” In other words, the importation of the exotic and different was a sign of prestige and “culture.” The situation is no different now: “Since the colonial era, the upper levels of metropolitan Indian society have been conscious of the importance of operating on an international scale as a means of preserving their impermeability to the classes below.”77 Newspapers in Kolkata carry stories of artists reading up on the exact dimensions of the Royal Albert Hall in London, or of a Bofors gun in Kargil. If, as was argued in the last section, one is in search of novelty in order to trounce a rival pandal, then one needs a field as wide as the world for thematic inspiration.

The public artistic tradition of satire provides a third parallel. Durgā and Kālī, especially, have always lent themselves to appropriation by Bengalis wishing to reflect, lament, or censure current events. This use of the Goddess has its roots in the medieval Bengali Maṅgalakāvyas, long narrative poems in honor of local, humanized deities, but it explodes in popular culture in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, with watercolor paintings, ribald poetry contests, and a whole host of dramatic farces and satires. One could marshal literally scores of examples, but three may be taken as representative here. First is a Kālīghāṭ paṭ from the mid-nineteenth century, in which Kālī is shown trouncing Śiva—except that the scene is really poking fun at the Memsahib-influenced woman who dominates her foppish, weak, Bābu husband.78 The second is a cartoon from 1875, lampooning Īśvarcandra Bidyāsāgar’s Society for the Prevention of Obscenity; Kālī is demurely covered in Victorian clothes.79 The third is a satire called Bodhan Bisarjan by Ahibhūṣaṇ Bhaṭṭācārya, from 1895. The scene is the Himalayas, where Durgā and her children are getting ready to come to Bengal for the Pūjā holidays. Śiva has the “flu,” and Durgā, who appears in a Memsahib’s dress with a nurse’s cap on her head, tells him that the best doctors are in Calcutta. Sarasvatī wants to go to Calcutta to get her veena, or lyre, repaired and flyers printed for her agitation on behalf of women’s rights in heavenly Vaikuntha. Kārtik, the perfect Bābu, is keen to sample Calcutta’s selection of towels, toiletries, silk handkerchiefs, cigars, and British pump shoes. Gaṇeśa, on the other hand, is afraid to go, lest he be deposited in the new zoo!80 In this light, dressing Durgā like a movie star or even like Monica Lewinsky is perfectly in keeping with former trends.

Indeed, visual art intended for a popular public audience—whether cartoon, painting, sculpture, drama, or poetry—has never been aimed simply at illustration; it acts as a forum for pressing concerns, making arguments, and debating about culture. Sandria Freitag has proposed that it was the religious and political procession (an obvious and purposeful public mixing of politics and religion) that allowed for the creation of the public sphere in colonial India; following the lead of Christopher Pinney, Ajay Sinha, and Joanne Waghorne, we could also claim the same for mass-produced visual arts that, despite their ephemerality, respond to a demand for relevant commentary on the part of the enjoying or purchasing audience and represent not kitsch but a process of democratization.81

Frank Korom, in his recent study of Bengali scroll painters and performers (paṭuās), notes this exact same showcasing of current events in their two-dimensional art: Osama bin Laden fleeing to Tora Bora, the crashing of the planes into the World Trade Center, the threat and decimation of AIDS, the Titanic, the funeral of Mother Teresa, George Bush ordering the American invasion of Afghanistan, and famines, birth control, floods, and the 2006 tsunami. According to Korom, while the paṭuās have always been innovators and indigenizers, their recent spate of political scrolls may be viewed in the context of audience requests for what Susan S. Bean might call “edutainment.”82 In one paṭuā’s depiction of the World Trade Center disaster, the couple at the center of the tragedy was a Bengali husband and wife.83

Fourth, even though the Pūjās have always been politicized, as argued above, one can situate the rise of the newly opulent, outlandishly creative pandal decorations of the last twenty years in India’s relatively recent liberalization policies. In answer to my request of my Bengali interviewees that they try to pinpoint when the goddesses’ temporary shrines began to take on thematic coherence, and why this change was effected, one astute woman observed that the austerities and uncertainties of the post-Partition period, coupled with the rise of the Naxalites in Bengal in the late 1960s and early 1970s, probably account for the relatively reserved Pūjā decorations of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s.84

Nehru’s five-year plans had assumed a virtually closed economy, the prioritizing of heavy industry over consumer goods, and the massive involvement of an overbureaucratized government in trade and industry; by contrast, the consumer goods revolution, started by Rajiv Gandhi in the early 1980s but pushed ahead by Narasimha Rao after 1991, spurred at least the upper echelons of Indian society to new growth. The spread of satellite television and the entry of India into the global market “transformed the face of many Indian cities, as advertising, fancy shops, new cars, televised soap operas, luxury goods, and still more visible youth culture proliferated.”85 Ravi Srivastava sees such liberalization as partly responsible for the increasing regionalization of India’s politics, as communities press for favor from the Union government or compete for foreign investment.86 One could make a related point for the Pūjās: the more universal and democratic they become, the more local, neighborhood-centered, and political their focus.87 In this sense the post-1980s market openness has not only served to provide Pūjā committees with access to global influences and products; it has also enlarged the arena, scope, and terms of their local rivalries. A small but pertinent example of this is the impact on the 2006 Pūjās of the World Cup Soccer games. Some pandal organizers, in protest against the near-monopoly of Italy’s colors, players, and stadia in Kolkata’s pandals, decided to showcase local football players instead. For instance, the Kasba Kheyali Sangha made their theme “Bānglār Football.” “Everyone is ready to stay up late for matches abroad but no one thinks of local football any more,” lamented a club organizer.” Commented the newspaper reporter rhetorically, “Which side will you roll, local or global?”88

A fifth way to gain insight into the particular melding of sociopolitical themes in the Bengali Śākta Pūjās is to compare them with similar festivals in India, to see whether there are any unifying features. In India, three regions immediately come to mind: the area around Varanasi, especially Ramnagar; Maharasthra, particularly the urban center of Mumbai; and Tamilnadu, especially Chennai.

The first example coincides, in fact, with Durgā Pūjā: the Rāmlīlās, or reenactments of the life of Rāma, performed during Navarātrī in North India, the most famous site being Ramnagar, across the river from Varanasi. Although the līlās employ live actors to replay the adventures of Rāma and Sītā, and not sculpted images, and while the action moves from site to site, not being situated in a stationary pandal, like Durgā Pūjā the Rāma festival has been built up by virtue of its royal or elite character. Environmental theater and performative theory expert Richard Schechner explains the enormous popularity of Ramnagar’s theatrical spectacle. “The most direct answer is that since the early nineteenth century, the Ramlila has been the defining project of the Maharajahs of Benares. The current line was established in the mid-eighteenth century and, caught between a failing Mughal power and an emergent British presence, was not secure on the throne. Sponsoring a large Ramlila was the way for the Maharajahs of Benares to shore up their religious and cultural authority at a time when they were losing both military power and economic autonomy.”89 Festivals that legitimate and provide scope for the advancement of elite aspirations have a certain family resemblance in India.

Two examples that come closer to the external form of Durgā Pūjā are connected to each other in their celebration of Gaṇeśa Pūjā, also called, in Mumbai, Gaṇapati Utsav and, in Chennai, Vināyaka Caturthī. Both festivals have forms very similar to what one sees in Bengal: urban epicenters, with Mumbai influencing trends in Maharasthrian towns and villages, and Chennai, Madurai, and Coimbatore doing the same for the Tamil countryside; hundreds or even thousands of images displayed in temporary neighborhood pandals; group sponsorship, financing, and advertising of such pandals; competition for prizes; public processions; controversies over the polluting of the environment by the dumping of the images and their paraphernalia into rivers and seas; and the borrowing of cultural themes for the decoration of images and their temporary homes (although neither region appears to approach Bengal’s exuberant reflection of social and national events in their festival displays). Researchers doing work in Maharashtra, for instance, report a wide range of innovations in the depiction of Gaṇapati: photographer Stephen Huyler saw the elephant-headed deity as the lead singer in a band of pop stars, accompanied by Elvis and Madonna;90 and in a more political twist, Thomas Blom Hansen reports a 1992 pandal in which Gaṇapati is surrounded by a tableau of the freedom struggle featuring the hero B. G. Tilak—whose unfinished work is being carried on by the Sangh Parivar and the BJP.91 Christopher Fuller, who is working on the Tamil Vināyaka festivals,92 found the Vināyaka of 1999 often worshiped amid replicas of Kargil scenes and accompanied not by his traditional rat vehicle but by an Indian army tank. Although, like the Bengali case, “unconventional innovations are particularly common in Chennai, where novelty is at a premium,”93 Fuller thinks that there is, as yet, nothing comparable in Tamilnadu to the lavish and creative pandal arrangements one finds in Kolkata.94

The histories of both Gaṇeśa festivals have also been embedded in political nationalism. Prior to the 1890s, when B. G. Tilak and others propagated the public form of the Maharashtrian Pūjā, the festival had been confined primarily to the temple and the house.95 But Tilak intended for it to encourage Hindu revivalism and mobilize culture for a political purpose. Like Durgā’s festival, Gaṇapati’s also underwent a change in the 1920s, when Pūjā associations emerged to link classes and neighborhoods. According to Gérard Heuzé, such mass Pūjās—with their street culture and their elite management—have become a “powerful but ambivalent medium for expressing popular opinion,” and “constitute one of the strongest sources of melting-pot effects.”96 Although it was regulated and de-politicized during certain periods under the British and again after Independence, since the 1980s the Shiv Sena / BJP combine has employed it for nationalistic, anti-Muslim purposes97; after 1995, when the BJP came into power in the Centre in alliance with the Shiv Sena, about 60 percent of the images of Gaṇapati had as a backdrop something to do with Shivaji’s martial exploits.98 Partly in imitation of this, since 1983 the VHP equivalent in South India, the Hindu Munnani (“Hindu Front”), has consciously popularized and sponsored the Vināyaka festival, using it to promote nationalism and assert Hindu muscle. In this they have been phenomenally successful; what started with a few images in 1983 had expanded in 1999 to 6,500 in Chennai alone.

In both Maharashtrian and Tamil cases, however, what gained impetus fifteen or twenty years ago under right-wing groups for political purposes has also caught on among independent groups (businessmen and professionals, particularly the proliferating middle classes), who are either non- or less politicized but who nevertheless join in to finance and enjoy the festivals as expressions of regional identity. Fuller refers to this expansive quality of the Caturthī as the “normalization of Hindu nationalism,”99 and claims that it is largely (though not entirely) a middle class, urban phenomenon. Even in Right-dominated Maharasthra, where it seems that representations of the (Muslim) “Other” are more allowable in the Pūjā context, in 1999 the Mumbai police requested one organization to take down the Pakistani flag from a dragon-like beast whom Gaṇapati was fighting, for fear that it might disturb the “sensitive fabric of the multi-religious demography of south Mumbai.”100

Joanne Waghorne, a scholar of Tamil urban space, comes to similar conclusions in her ongoing studies of modern-day temple construction in Chennai. She describes the impulse to build lavish temples with humanized deities on the śikharas—deities whose features often model contemporary political or theatrical icons—as deriving from what she calls “middle-class religion.” For her, such gentrified religion seeks to soften, humanize, and dignify; to forge links between religious and consumer realms; and to offer strong statements of national identity in religious ritual contexts. Although Waghorne does not discuss public festivals per se, her work nicely dovetails with that of Fuller and his research team: when religion enters an urban, middle-class–dominated public space, social and political concerns get reflected in its manifested forms.

Perhaps one can see in the Kolkata, Mumbai, and Chennai cases something of a similar history: in each, a festival is consciously aggrandized, universalized, and politicized by leaders tuned in to national politics and ideological thinking, for an initial purpose of religious solidarity and definition.101 However, although in all three instances the initiators had nationalistic, political motivations, subsequent history has shown the festivals to have been taken over in large part by a wider spectrum of the non-or differently politicized public, which, over time and in a global environment, has used the festivals for their own purposes. The fact that Durgā Pūjā is the least politicized and most ostentatiously and creatively celebrated of the three may be explained by the facts (1) that Durgā Pūjā was the public cultural icon of Bengali Hindus long before 1926, and hence was woven in myriad ways—some satirical and even playful—into the public and private lives of ordinary people, and (2) that the CPI(M) has consciously striven to downplay communalism in the public arena. One does not see the sort of explicit propagandizing of the Durgā Pūjā by the CPI(M) in Bengal, for instance, that we do of Gaṇapati Utsav by the Shiv Sena in Maharashtra. Although Vināyaka Caturthī is too new in Tamilnadu to offer any lasting comparisons as yet, it is interesting to note that the Munnani has not gravitated toward Murugan, the indigenous mascot of Tamil identity, but toward a deity linked with pan-Indian nationalism. And one suspects that the more tightly controlled a festival is, by a nationalist state or political agenda, the more wary individual organizers become in choosing to communicate countervailing platforms through their pandals. One wonders, for instance, whether Munnani-sponsored Vināyaka Caturthī celebrations could occur in pandals depicting churches from Europe or Goa (fig. 5.6), the Taj Mahal, or the proposed Ayodhya temple, surrounded by a mosque, a church, and other places of worship102—all of which have been created in Kolkata over the past two decades.

Still looking within India for parallels, we find another striking similarity in the cohesive national iconism of the Republic Day Parades. Jyotindra Jain writes, “[In] India’s post-Independence … systematic structuring of the Republic Day Parade, the pageant and performances comprise … cultural tableaux depicting highly romanticized versions of landmarks in Indian history, essentialized representations of tribal and village communities, [and] traditional handicrafts.” For instance, Mysore’s palace goes by on a float, as do Meghalaya’s tribal peoples, Gujarat’s artistry and ethnic culture, Sravanabelgola’s giant Jain statue, and Orissan Pipli applique craft. Such a “performed archive” presents “authentic” tribal peoples and their dances and culture as living examples of India’s ancient roots.103

Lest one get the mistaken impression that all public festivals in India conform to a style similar to that of Durgā and her sister goddesses in Bengal and Gaṇeśa in Maharashtra and perhaps Tamilnadu, it is worthwhile briefly to consider the additional examples of festival culture given by Paul Younger in his book, Playing Host to Deity: Festival Religion in the South Indian Tradition. While his survey of several South Indian festivals, Hindu and Christian, mentions the festivals’ independence from official political and clerical authorities, their warm, playful type of religion, their inclusion of social castes and communities, and their creative genius—all of which could be said of the Pūjās—several of the deities studied by Younger also inspire trance, possession, exorcism, and bodily mortification, none of which appears to obtain in the Bengali cases.104 Why this is, I surmise, has to do with the middle-class sponsorship of the Bengali festivals, which brings with it a middle-class concern for respectability, self-control, and emotional tidiness.

FIGURE 5.6. A Goan church model being dismantled at the conclusion of Jagaddhātrī Pūjā, Circus Math Sarbajanin. Chandannagar, November 2000. Photo by Rachel Fell McDermott.

Let us, lastly, briefly take the discussion even further afield, from India to the carnival societies of Europe, South America, and the Caribbean. Carnival celebrations in Spain, Mexico, and Trinidad are strikingly similar to the Bengali Śākta Pūjās—and to the Gaṇapati Caturthīs of Mumbai and Chennai. First, they are public, galvanize almost all of society, and act as markers of national identity. Second, the characteristic features of Durgā, Jagaddhātrī, and Kālī Pūjās are replicated here as well: the democratization of masquerade, calypso, and music costs over wide sections of the population, who compete with each other in fierce rivalries for coveted prizes; an emphasis on thematic novelty as the chief element of a successful bid for recognition; and the incorporation of contemporary life in the artforms created for the celebrations each year. Peter Mason, in his book on carnival in Trinidad, notes the following themes in the costumes, floats, and lyrics composed for the occasion in the mid-1990s: fantasy, outer space, insects, ghosts, vampires, government ineptitude, male/female relationships, West Indian unity, problems with the national highway, the lottery, and even haircut trends.105

Moreover, all scholars of carnival note that, in whatever society it is celebrated, it goes through periods of greater or lesser distanciation from politics. For example, although the Trinidadian festival began in the 1800s during the planter days, it became highly politicized from 1940 to 1962, when it functioned as an outlet for anti-British sentiment. Nowadays, increasingly patronized by the middle class and by women, it has become more mainstream and socially acceptable.106 To quote Peter Stallybrass and Allon White, theorists of carnival culture, “for long periods carnival may be a stable and cyclical ritual with no noticeable politically transformative effects but … given the presence of sharpened political antagonism, it may often act as catalyst and site of actual and symbolic struggle.”107

To bring all of this back to the Bengali Pūjās: It appears that what we are seeing right now in Bengal is a politicized but not communal stage in a national holiday season that has, many times in the last two hundred and fifty years, been used for communal purposes—first, by the zamindars in their articulation of political strength against the Mughal representatives and then against the British, and second, by Hindu nationalists of the pre-Independence era who resorted to the public festivals as occasions to educate and whip up Hindu sentiment, often against the minority communities. In a fairly prosperous modern Bengal, where middle-class wealth and consumerism have built up Kolkata, the urban center of all Pūjā trends, the Pūjās reflect a pan-Indian glorying in national pride, but do not, as do the Shiv Sena or the Hindu Munnani, pick on “enemies” (read: Muslims) within the state. In this sense, the goddesses can be seen as mascots of national, not narrowly religious, honor; and what Svetlana Boym calls the “danger of nostalgia”—namely, that we confuse the actual past with the imaginary one, being ready to die or kill to protect it—is averted for the present.108 One wonders to what use Durgā, Jagaddhātrī, and Kālī Pūjās would be put, were a Hindu nationalist party to gain ascendancy in West Bengal.109 Note, however, that neither Jyoti Basu and nor Buddhadeb Bhaṭṭācārya has been immune to seeking the Goddess when she could advance his own agenda. As an example, the pandal that demonized Bill Clinton and Tony Blair was organized by a neighborhood of CPI(M) supporters. Although too much bhakti may be discomfiting, these multivalent Pūjās can also be useful to—and stabilizing of—the status quo.

The claim that the Pūjās are at base “secular” serves not just the Communists; it is also integral to a common lament by the older generation, who rue the passing of a faith-based age (and note that this grievance can be found as far back as the early nineteenth century, and probably earlier110), as well as to a spirited defense of Pūjā hoopla by those who read history differently and who celebrate the festival’s effervescence. Reminding their readers that the zamindars exulted in “pomp and wildness” and that the nineteenth-century bāroiyāri Pūjās met the entertainment needs of the masses as well as of the “Fast Bābus” (people who enjoyed amusements),111 such writers exhort the shedding of “nasṭyāljik” feelings: “Durgā Pūjā is far more than a ritual to us; it is a people’s festival … [it is] secular. Durgā Pūjā is much greater in dimension, and its appeal will increase manifold if it can shed its ritualistic strictness and inhibitions.”112

In sum, to link both halves of this chapter: The modern Bengali Śākta Pūjās represent the transformation of an aristocratic mode of self-promoting self-expression by goddess worship, in which, though democratized through the influence of urbanization, the consumer market, and expanding middle-class participation, the same rivalries and opportunities for self-definition still exist today, if on a widened scale. At the moment, in the early decades of the twenty-first century, the festivals are relatively locally integrative, their sponsors aspiring to a national and even international arena of public, visually dazzling notoriety.

Why Pūjā Isn’t Christmas

Every holiday the world over has a history, a sort of flavor or rasa—one might even say a dominant tone, or a bīja mantra—that gives it distinctiveness. I do not mean to imply that festivals such as Durgā, Jagaddhātrī, or Kālī Pūjā are unchanging or static. However, I do believe that both of the characteristics I have mentioned—the entwining of religious rituals with (1) a competitive search for prestige and (2) a mirroring of social and political themes—have a common origin and make sense given their developmental history and their status as urban, largely middle-class festivals expressive of cultural identity. In 1906, during the furor over the first partition of Bengal, one Bengali author tried to differentiate between Christmas and the Pūjās. Christmas, he said, values individual humility and repentance, whereas Durgā Pūjā is a national sacrament, and “self-assertion is the essential method.”113 Although this author may have been too kind to Christmas (after all, like Durgā Pūjā, Christmas partly owes its success as a state tradition to its perceived secularism and its unabashed engagement in commercial extravagance114), and although, as we have seen, Christmas may be less appropriate as a measuring rod for the Pūjās than carnival, I think the 1906 description of the Śākta festivals is apt. From their beginning, status and reputation have been the prizes of these celebrations. And at their center is a Goddess whose humanization and symbolic malleability allow her to stand for and against, inside and outside, the social contexts of her votaries. Hence she appears aboard both the Titanic and an aircraft carrier, tacitly blessing those who, whether in the fields of artistry or arms, assert themselves for honor.