3Durgā the Daughter: Folk and Familial Traditions

In chapters 1 and 2 we focused on the grandeur of Durgā Pūjā: the martial goddess with her power to confer strength, status, and riches; the opulence of the displays, entertainments, and feasts hosted in her honor; and the political multivalence of her festival as a cipher for the colonial relationship between Britons and Bengalis. But Durgā Mahiṣamardinī is just one of the three important personalities, or threads, expressed in the rich tapestry of this festival. A second—just as prominent and, in fact, more vital to the emotional center of the Pūjā—is the daughter, Umā. Durgā is the protectress, the mother who slays demons and rids the world of obstacles. But she is not close to the heart. It is Umā, Śiva’s gentle wife and the daughter of Menakā and Himālaya, who, standing in for the missed daughters of youth, evokes real longing. In this chapter we review literary, ritual, and iconographic evidence for the importance of Umā to the Pūjā, attempt to account for her role in the history of the festival, and return to the theme of nostalgia to interpret her significance.

The Daughter’s Centrality to the Pūjā: Umā’s Life, Women’s Lives

Almost everyone who knows anything about the Hindu religious tradition has heard of Śiva and Pārvatī—the divine couple who live with their two sons on Mount Kailasa, and who are celebrated in myth and art as the embodiments of the male and female principles (puruṣa and prakṛti), on the one hand, and of the tension between the renouncer and householder lifestyles, on the other. This association between Śiva, the “Benevolent,” the erotic ascetic, the dancing lord of destruction, and Pārvatī, the daughter of the mountain, has a long history in Sanskrit literature, dating back at least as far as the epic period, in the centuries immediately preceding and following our Common Era.1 It is in Kālidāsa’s Kumārasambhava and in the range of Purāṇic literature spanning the fourth to the sixteenth centuries, however, where we see the real flowering of stories about Śiva and Pārvatī: here we get detailed accounts of Pārvatī’s former existence as Satī; Satī’s suicide in mortification over her father’s insult to her new husband, Śiva; Satī’s rebirth as Pārvatī in the home of the mountain Himālaya and his wife, Menā; her marriage, once again, to Śiva; and the descriptions of their wedded life on Mount Kailasa. It is not only the Sanskrit tradition which has delighted in the myths and personalities of this divine pair; Śiva and Pārvatī have also found a place in vernacular literatures, folktales, and folksongs all over India, where their stories gain regional flavors and meanings.

The Bengali regionalization of the Śiva–Pārvatī story has taken expression in a variety of narrative, poetic, ritual, iconographic, and political registers from the fifteenth century to the present. Here I mention five chief ways in which Umā can be seen to occupy center stage in the Pūjā experience.

First, the literary genre most germane to our study of Durgā Pūjā is a devotional poetry tradition that began to be composed at the end of the eighteenth century and that takes the relationship between Śiva and Pārvatī as a principal theme. Indeed, one of the most endearing characteristics of Durgā Pūjā in Bengal is the belief that during the three main days of the festival the goddess Umā, or Gaurī—the name Pārvatī is rarely used in this genre—returns home from her life with Śiva on Kailasa to visit her parents. Āgamanī songs celebrate her coming and bijayā songs, sung at the end of the three-days festival, lament her imminent departure.2 Together, these āgamanī and bijayā songs are referred to as Umā-saṅgīt, or songs on Umā.

Āgamanī and bijayā poems are essentially much-shortened versions of the stories about Umā and Śiva as narrated in the Bengali Maṅgalakāvyas of the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries. As their generic titles, maṅgala-kāvya or vijaya-kāvya, indicate, these long narrative poems celebrate the auspicious character or victory of a particular god or goddess. The divine heroes and heroines of such poems are manifold, but are principally female, and Umā figures prominently in the literature.

As a general matter, the deities of the Maṅgalakāvyas come close to humans. They do this through the medium of the vernacular Bengali, in poems whose scenes incorporate regional scenery and whose stories describe normal people in intense interaction with divine figures. Several of these poems include tellings of the Śiva and Umā story, but from a Bengali perspective. Here Śiva is a rustic figure who tills the soil, and he leads a vagabond, drug-addicted, irresponsible life. Moreover, he is old. In Bhāratcandra’s Annadāmaṅgal, Umā’s mother, Menakā, says, “Ai, ai, ai, is this old man Gaurī’s bridegroom?” Umā’s life with him is hard and unhappy—so much so that in one Maṅgalakāvya a human woman takes pity on the Goddess and offers to help her.3 Depictions more favorable to Śiva can be seen in voluminous and popular Śiva-centered Maṅgalakāvyas, the Śivāyanas. One, written by Rāmeśvara Bhaṭṭācārya in about 1750, shows fully Bengali-ized domestic scenes between Śiva, Umā, and their two sons in Kailasa. Here, in a family meal, Umā serves Bengali dishes.4

This humanization and regionalization of Umā and Śiva is also evident in the āgamanī and bijayā songs. The earliest poets to compose in this new genre were Rāmprasād Sen (ca. 1718–1775) and a few of his late-eighteenth-century contemporaries.5 In form, the poems are short, lyrical, rhymed vignettes, sung to a specified tune and meter. At the end of each is a bhaṇitā, or signature line, when the composer inserts his name into the action of the story. Probably since their inception these āgamanī and bijayā songs have been strung together to form a coherent story in several parts, similar in format to the Maṅgalakāvyas.

Though the Umā-saṅgīt style began in the last decades of the eighteenth century, it was composers of the nineteenth century who developed the story line and wrote poems of lasting artistic value. Kamalākānta Bhaṭṭācārya (ca. 1769–1820), Rāmprasād’s most famous follower, was a prime mover in this regard; he is the first Śākta poet to devote a substantial portion of his corpus to this theme, establishing patterns that were copied and elaborated upon by subsequent poets.

These poems tell the story of Umā’s return home to her parents, Menakā and Girirāj. Girirāj is actually the mountain Himālaya, although his abode in “the Mountain City” is usually understood to be somewhere in Bengal.6 Umā spends the entire year in Kailasa with Śiva, the dubious husband found for her by the unscrupulous matchmaker Nārada, and her parents miss her terribly, worrying over her welfare. Reports they hear abut Śiva are not reassuring: he is said to live in the cremation grounds, wear nothing except a tiger’s skin, be addicted to hemp and other intoxicants, and keep a second wife, the Ganges, who dwells in his matted hair. Umā’s once-yearly homecoming to Bengal, therefore, is anticipated with mingled concern and excitement: Menakā, Girirāj, and their friends will have her all to themselves again from the evening of the sixth day of the Durgā Pūjā festival until the morning of the dreaded tenth day, which robs them of their daughter and their joy for another year.

The story usually opens in the weeks before the autumnal Pūjā season, with Menakā pining for and dreaming of Umā. She hears the worst possible news through Nārada—namely, that her daughter is unhappy and blames her mother for her situation:

Hey, Mountain King, Gaurī is sulking.

Listen to what she told Nārada in anguish—

“Mother handed me over to the Naked Lord

and now I see that she has forgotten me.

Hara’s robe is a tiger’s skin,

his ornaments a necklace of bones,

and a serpent is dangling in his matted hair.

The only thing he possesses is the dhuturā fruit!

Mother, only you would forget such things.

What’s worse, there’s the vexation of a co-wife

which I can’t tolerate.

How much agony I’ve endured!

Suradhunī, adored by my husband,

is always lying on my Śaṅkara’s head.”

Take Kamalākānta’s advice.

What she says is absolutely true.

Jewel of the Mountain Peaks,

your daughter has become a beggar,

just like her husband.7

Horrified, Menakā nags lazy Girirāj to go to Kailasa to fetch their daughter home, but he procrastinates, or says that he has gone when he really has not. Bemoans his wife, constrained by social convention to depend upon a man for the permission and means to travel:

Tell me,

what can I do?

Unkind fate made me

a woman controlled and ruled by others.

Can anyone understand my mental pain?

Only the sufferer knows.

Day and night

again and again

how much more can I plead?

The Mountain, Jewel of the Hilly Peaks,

hears but does not listen.

Whom can I tell

the way I feel for Umā?

Who will be sad

with my sadness?

Let the Mountain King be happy;

he has no heart.

Friend, I’ve decided to forget my shame.

I’ll take Kamalākānta and go to Kailasa.

She’s my very own daughter—

I’ll fetch her myself.8

Meanwhile the same argument is going on in Kailasa, with Umā begging Śiva for the permission to go see her parents.

Hey, Hara, Ganges-Holder,

promise I can go to my father’s place.

What are You brooding about?

The worlds are contained in Your fingernail,

but no one would know it,

looking at Your face.

My father, the Lord of the Mountain,

has arrived to visit You

and to take me away.

It has been so many days since I went home

and saw my mother face to face.

Ceaselessly, day and night,

how she weeps for me!

Like a thirsty cātaki bird, the queen stares

at the road that will bring me home.

Can’t I make You understand

my mental agony at not seeing her face?

But how can I go without Your consent?

My husband, don’t crack jokes;

just satisfy my desire.

Hara, let me say good-bye,

Your mind at ease.

And give me Kamalākānta as an attendant.

I assure You

we’ll be back in three days.9

Eventually Śiva is persuaded, and Umā returns with her father to the Himalayan kingdom. Menakā, ecstatic, rushes out to greet her daughter.

The Queen takes Gaurī on her lap

and says sweet words to her.

“My Umī, golden creeper,

Mṛtyuñjaya lives in the cremation grounds.

I die in grief over him, and also over you

and me, being separated.

“My heart laments day and night,

but since I’m a mountain woman

unable to move

I can’t go see you.

Thinking over my life,

I stare in hope at the road;

I weep when I don’t see you.

“Shame, shame, shame!

Is this a matter for debate?

I’m mortified every time I hear about it:

the Mountain gave you away

to a man who doesn’t fear snakes

and who smears his body with ashes.

“You are all-auspiciousness,

a raft over the sea, able to ferry us

to the other side.

But when I see this suffering of yours

my grieving chest bursts;

for even you can’t destroy this suffering.”10

In some of the poems, Umā tries to calm her mother’s worries. In others, it is obvious that she is unhappy, but is attempting to spare her mother the truth of her condition.

After a joyful three days, it is time once again for Umā to leave her parents’ home. Menakā vows not to let Śiva take her away, and pleads with the day of her departure, asking it not to dawn. But the inevitable must occur. Umā leaves, and her mother is plunged into darkness. The following is a bijayā poem, sung as the Goddess is bid farewell.

What happened?

The ninth night is over.

I hear the beat beat beat

of the large ḍamaru drums

and the sound shatters my heart.

How can I express my agony?

Look at Gaurī;

her moon-face has become so pale.

I would give that beggar Trident-Bearer

anything He asked for.

Even if He wanted my life

I’d give it up.

Who can fathom Him?

He doesn’t know right from wrong.

The more I think of Bhava’s manners

the more stony I become.

As long as I live,

how can I send Gaurī?

Why does the Three-Eyed One crave Her so needlessly?

Take Kamalākānta along

and make Hara understand:

if You don’t behave honorably,

you can’t expect others to treat you with honor,

either.11

Viewed from a Sanskrit, Purāṇa-inspired perspective, there are many ways in which the portrayal of Umā and Śiva in these Bengali poems is strange and distinctly regional. While it can be argued that the cycle of Sanskrit myths that includes Pārvatī—the necessity for the birth of Skanda in order to slay the demon Tāraka, Pārvatī’s former birth as Satī, daughter of Dakṣa, and Pārvatī’s life with her erotic-ascetic lord12—focuses primarily on Śiva, and does so in context of Kailasa, the āgamanī and bijayā poems place Umā center stage and concentrate on her relationship with her parents, in the Bengali Himalayan city.13 Several important themes from the Sanskrit myth cycle are mentioned either only obliquely in the Umā-saṅgīt, or not at all. In particular, the action of these Bengali poems occurs after Śiva’s marriage to Umā, and derives its emotional force from the motif of waiting. There is no retelling of the Satī story, Umā is never depicted doing ascetic practices to gain Śiva’s hand, the wedding is never described, and Kailasa as a setting for the poems is rare. Śiva the erotic lover is nowhere to be found; there are no bed scenes.14 While Umā often returns home with her two children, Pot-Belly and Six-Face, the latter, Skanda, who is the whole reason for her marriage to Śiva in the Purāṇas—so as to kill the demon Tāraka—is never singled out for mention at all. The reason for Umā’s birth in the āgamanī and bijayā songs is to reward Menakā for her great devotion.

In other words, Umā is in the foreground. She is her parents’ only daughter, and they bitterly regret having been forced to give her in marriage to Śiva.15 Unlike the Sanskrit myths, in which the seven sages and Arundhatī negotiate on Śiva’s behalf with Umā’s father for her hand in marriage (note that it is Śiva who initiates in the Sanskrit Purāṇas), here it is Himālaya and Menakā, who because of their poverty seek out the services of Nārada, who finds them a match commensurable with their means.16 You pay for what you get—Śiva.

Indeed, in the Umā-saṅgīt Śiva is given almost no respect. This can be seen in the lack of details one receives about his heroic, godlike personality; though there are allusions to his Sanskrit alter ego in his Bengali epithets, there is no narration of his burning of Kāma, his defeat of the Triple City, or his various other exploits.17 Instead, his nakedness, homelessness, oddball ornaments, drug addiction, and the bad company he keeps (namely, his troupes of ghosts and ghouls) are primarily the results of his poverty; he has no money to buy clothes or pay rent, and he ate poison because he was hungry.18 Moreover, his keeping of a co-wife does not endear him to Umā’s parents, who resent him and never invite him home to spend the Pūjā holidays with them.

Bengali scholars have argued that the Umā-saṅgīt is built upon, mirrors even, the experiences of real Bengali families in the late medieval period. The circumstances of Umā’s family appear similar to a mild form of Brahman Kulīnism—that is, two to three wives living in the husband’s house, where the wives are considerably younger than their husband, their fathers having been constrained, often through the matchmaking services of people whom they did not trust, to give them away as children.19 According to the census of 1881 Kulīnism was widely practiced by one of the two largest groups of Brahmans in Bengal, the Rāḍhī Brahmans. “Of aristocratic or noble descent,” Kulīns practiced strict hypergamy: Kulīn women could only marry Kulīn men. The consequent surfeit of Kulīn women resulted in multiple marriages for Kulīn men, many of whom left their brides with their natal families and visited them only rarely, to collect the obligatory gifts from their fathers.20 The poetry about Menakā’s concern over Umā’s co-wife, the Ganges River, reflects the agony of such polygamous situations.

In addition, expectations that a father would give his daughter away (kanyādān) well before puberty led to increasingly tender marriageable ages; it was normative in early medieval Bengal for little girls to be married off at age eight, and for their husbands to be three times their age.21 One of the meanings of Umā’s name Gaurī is “eight-year-old girl”; hence the poignancy of the link between the Umā-saṅgīt and the lives of real women. Margaret Urquhart put it well in 1925: “From childhood a woman’s view is directed away from her own patriarchal group, in which she has little part to play, to the possible family tree on which she will be grafted. This is what makes the story of the marriage of Gaurī, the girl wife of the god Śiva, so popular and full of poignant meaning to the zenana women. The period of a girl’s connection with her father’s house is made as brief as possible…. A special traditional sanctity attaches to the age of eight as a suitable one for marriage, Gaurī, Śiva’s wife, according to general belief, having been married at that age.”22 From this vantage point, reading the descriptions of Śiva in the āgamanī and bijayā songs is like being introduced to a Kulīn mother’s worst fear: her little daughter married perforce to an old, totally unsuitable man.

Women’s lives in general were highly restricted in late medieval Bengal, with clearly delineated divisions between the male public world and the female domestic one. The only women who bridged that divide—those who danced in the “nautches” in the homes of the wealthy—were not considered “respectable” role models for daughters to emulate, and many of them, in any case, were Muslim dancers.23 Daughters-in-law in particular were largely confined: when inside, to the antaḥpur, zenana, or women’s quarters, and when outside, to the palanquin or covered bullock cart or boat. Education was not typically available for women, even for the wives of the traditional elite. Menakā’s laments that she cannot visit her daughter by herself, must rely on men for information from the outside world, and is hampered by her simple nature all reflect this cultural environment of eighteenth- to nineteenth-century Bengal.

Wherever the North Indian custom of marriage prevails—that is, between families whose members are not related by blood, as counted back to seven generations on the male sides—one finds rhymes, folksongs, and proverbs expressing the pain of losing a daughter to a family of strangers, away from the safety of her father’s village.24 The following Bengali rhyme poignantly conveys the anticipation of unbearable loss:

Granny, why are you crying, holding the basket full of sindūr?

Only yesterday you rubbed my hair parting with heaps of it!

Mā, why are you crying, holding that jug of milk?

Only yesterday you fed me heaps of milk.

Sister-in-law, why are you crying, holding a basket of rice?

Only yesterday you fed me heaps of rice.

Daddy, why are you crying, holding the beams of the thatched

roof house?

Only yesterday you used that stick to beat me!25

Some Bengali aphorisms do not bewail the pain of customary child marriage, but attack it for its cruelty. For instance, the following decries those who would cover up the heinousness of the Kulīn match—or the injustice meted out to any innocent: “You gave Gaurī into the hands of a forty-two-year-old. Saying mantras won’t lessen the fact that you have sacrificed her.”26

Given such conditions, daughters-in-law looked forward with anticipation to the Pūjā holidays, when they might be allowed to return home to their parents. At stake was both the joy of reunion with family and the pampered leisure time with fewer restrictions, and also the reliving of Pūjā holidays, remembered for their magic. For those who did not or could not go home to their fathers’ houses, Pūjās in their in-laws’ residences—as also marriages—gave women “a chance to participate in activities that had meaning beyond the immediate surroundings,” even if, in wealthy families, this meant no more than watching the festivities through screens. By the end of the nineteenth century, Pūjā vacations, affected by British attitudes to travel, leisure, and holiday, were “no longer only used as an opportunity to visit the ancestral village, but as a time to go away for a holiday. Sarasibala Ray described her excitement at the prospect of a trip to Murshidabad in the pūjā holidays of 1900, which she looked forward to as an escape from the normal conventions of the antahpur.”27

Through its reflection of contemporary Brahmanical customs of polygamy, child marriage, and the experience of mother–daughter bonding, the Umā-saṅgīt renders Durgā Pūjā meaningful on a whole host of levels not apparent merely from a glance at the image of Mahiṣamardinī. Āgamanī and bijayā songs are clear in their message: the goddess who comes is the daughter, not the demon-slayer. Moreover, she is the universal Bengali daughter of every house, and her coming transforms the life of Bengali Menakās everywhere.

A second indicator that the daughter-goddess is integral to the meaning of Durgā Pūjā is her inclusion, or that of references to little girls, in the festival itself. To begin with, the origin stories of many banedi bāḍīr Pūjās are centered around girls. Either a daughter asks her father to start celebrating the Pūjā at their home,28 or a founding father dreams of a devī in the form of a girl, who expresses her wish to be worshiped not as the martial Durgā but as the daughter Umā with her two children,29 or the Pūjā is founded by parents mourning the loss of their own daughter, for whom the goddess Umā substitutes. Sometimes this loss is due to marriage, as in the case of Gaṇeścandra Chunder, who married off his daughter in 1876, but missed her so much that he started a Pūjā, not only to remind him of her but also so that he could have an excuse to bring her home for the holidays.30 At other times the loss is more final; the historic Dawn family Pūjā was begun in 1760 by Rāmnārāyaṇ Dawn after his young daughter came home from her parents-in-laws’ house and, while there, died of cholera.31

The presence of Umā is also evidenced in rituals associated with the Pūjā. Mahālayā, the holy day that falls six days before the Pūjā on the new-moon tithi of devī pakṣa and whose primary function is to honor the ancestors (tarpaṇa), has been hijacked, so to speak, by Durgā Pūjā. For most Bengalis, Mahālayā is the day on which Umā sets out for Bengal from her home on Mount Kailasa; since the 1930s, generations of Bengalis have awoken at dawn to the voice of Bīrendrakṛṣṇa Bhadra singing the Caṇḍīpāth, or “Devī-Māhātmya,” story on All India Radio. That this new layer on the older Mahālayā festival is truly the undisputed harbinger of the Pūjās is demonstrated by what happened in 2001, when the almanac called for Mahālayā to occur one month and six days before the start of Durgā Pūjā: All India Radio decided to postpone the broadcast of its traditional radio show by a month.32

Apart from the singing of the āgamanī and bijayā songs, other rituals pointing to the importance of girls and daughters to the Pūjā include the kumārī pūjā, described in chapter 1, by which the majestic goddess is rendered irresistibly lovable and pure (fig. 3.1); homey customs particular to certain families, such as at the Bagbazar Sānyāl house at Kasi Bose Lane, Kolkata, where they feed the Goddess morning tea;33 and, most suggestive of all, the farewell rites for the Goddess on the tenth day, or Daśamī. The image of Durgā is treated exactly like the married daughter who, after spending time at home in her father’s house, is sent back to her husband’s place: she is adorned with vermillion, fed sweets (these are daubed onto the image’s mouth), and given betel nuts into her hands. After this, all the women of the locality daub each other with red powder, in a jovial ritual called sindūr-khelā, or playing with vermillion (fig. 3.2). Even the rite in which blue-throated birds are released at the moment of Durgā’s immersion in the river, and hence departure for Kailasa, expresses the belief that the goddess who has just left Bengal is Śiva’s gentle wife, not the martial demon-slayer. According to historian Mohit Rāy, the real purpose of these nīlkaṇṭha pākhīs was actually quite plebeian and woman-centered: in the Krishnanagar Rāj family these were pet birds set free at the waterside who flew back to their mistresses in the zenana, who otherwise would not have known when the immersion had occurred, since they were not allowed to go out.34

FIGURE 3.1. Feeding the Goddess in the shape of a little girl at kumārī pūjā. Kolkata, October 2008. Photo by Jayanta Roy.

A third gauge of Umā’s importance to the Pūjā is iconographic, and can be seen in the fact that she brings her four children home with her to her parents’ house. Indeed, the clay image of Durgā Mahiṣamardinī is typically flanked, on her right, by smaller images (mūrtis) of Gaṇeśa and Lakṣmī, and on her left, by Kārtik and Sarasvatī. I am not aware of any other Indian regional tradition in which Pārvatī/Umā is said to be the mother of Lakṣmī and Sarasvatī, but in Bengal this has been claimed—iconographically, at least—since the late seventeenth century. A few old family Pūjās substitute Umā’s friends, Jayā and Bijayā, for the four children, and others omit the demon-slayer entirely from their Pūjā tableaux, showcasing instead: a two-handed Durgā, with her lion but without the buffalo demon; Hara-Gaurī, the husband-and-wife team, where Gaurī is diminutive beside or on top of her lord35; or even Gaṇeśa-Jananī, where the only image displayed is a seated Umā with the chubby elephant-god in her lap.36 In general, those families who sponsor a Pūjā without explicit representation of the martial Durgā have something in their backgrounds that militates against sacrifice, blood, or fear. Sometimes they are Vaiṣṇava or Vaiṣṇava-leaning, and sometimes they simply do not wish to emphasize the Goddess’s death-dealing aspect. According to traditional stories of the Tripura Rāj family, for example, which claims to have been worshiping a two-armed goddess for five hundred years, she appeared to an ancestress, Mahārāṇī Sulakṣaṇādebī, and said, “I’m not going to harm you. There’s no cause for fear, so you don’t need all those hands.”37 At the other end of the spectrum in terms of elitism and the longevity of its Pūjā, but with the same proclivity to sideline Durgā for Umā, is the very recent tradition of sculpting Durgā at a remote tribal village near Santiniketan. Here Durgā arrives with lotuses rather than weapons in her hands. “Ma Uma is coming to her father’s house. Why will she come with arms in her ten hands?”38 No matter how the Goddess is represented—with or without children, with or without a buffalo-demon—the face of Śiva is almost always painted on the backdrop above and behind her, as if to remind her and the viewer that this is his wife, and that he expects her to return to him from her father’s house quite soon.

FIGURE 3.2. Sindūr-khelā at a house in Howrah city. October 2000. Photo by Jayanta Roy.

Fourth, Umā’s salience in the context of the Pūjās is demonstrated by her use by Bengali nationalists in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when, as we have seen in chapter 2, the Goddess herself became a lithe, needy, human figure, needing to be saved, like a daughter. R. K. Dasgupta, in an essay in 1980, describes this idea of the Divine Mother in bondage as a theologically ambiguous and essentially Bengali idea, for the Supreme Mother is also Umā in distress: “The Mother who will wipe your tears is herself in tears.”39 Hence the presence of the daughter within the Bengali goddess tradition has humanized the Divine, making her uniquely tender and affectionate, even weak.

Fifth, the importance of the daughter tradition is further indicated by the centrality of children to the Pūjā hoopla and excitement. All the major newspapers, in English and Bengali, run special inserts at the season for children, not only featuring articles on clothes, music, and food, but offering Pūjā quizzes and requesting children to send in their Durgā-centered pictures, poems, and experiences for publication. In 1999 the Statesman’s themes in such children’s sections were “When Durga was a Little Girl” and “When Durga was Young.” In 2006 a Behala Pūjā committee took children’s depictions of the Goddess (holding water guns or lightsabers from Star Wars) and employed an artist to patch them together to create murals to decorate the inside of their pandal; in 2008 the Santoshpur Lake Pally Committee made children’s fantasy the theme of its pandal, and asked the artist to sculpt her as he would have visualized her as a child.40

When the literary, ritual, iconographic, political, and contemporary evidence presented thus far is reviewed, it is abundantly clear that Umā is integral to Durgā Pūjā. The song cycle celebrating her return home to Menakā and Girirāj, the various ways in which the women’s rituals of the festival mirror or express the importance of daughters and the sadness of their departure at marriage, the visual impact of the images as worshiped in ṭhākurdālāns and pandals, and the theologically intriguing resonance in political discourse of the vulnerable Invincible—all these elements point to a strongly emotive attachment to the Goddess-as-daughter, and a longing to bring her home.41 One is reminded in this context of the work of William Sax, whose research on the goddess Nandā-devī in Uttarkhand demonstrates how a literary and ritual tradition of reenacting the Goddess’s return to her husband’s home helps women to enunciate, but not necessarily to change or escape from, the pain they experience through the Gahrwal system of out-marriage. Sax’s work also underscores the importance to women, despite the male emphasis on the husband’s house, of the father’s home and all that it represents: love, acceptance, leisure, and true belonging.42

Durgā the Daughter? The Interpretive Puzzle

It is not intuitively obvious why one would find Umā so prominently displayed in an agricultural festival used by the elite to aggrandize their wealth and position. When did Durgā Mahiṣamardinī gain four children? And when did Mahiṣamardinī/Umā become the universal Bengali daughter who returns exactly once a year, at the Pūjā holiday?

There are no easy answers. The Sanskrit Purāṇas and Tantras, and even Tantric digests such as Āgamavāgīśa’s Tantrasāra, say nothing about Gaṇeśa, Lakṣmī, Kārtik, or Sarasvatī, mentioning only the Goddess, her lion, and the buffalo-demon.43 The first allusions to Durgā’s children occur in ritual and narrative texts of the medieval period: Vidyāpati’s Durgābhaktitaraṅginī of the fourteenth to fifteenth century, Mukundarām Cakrabartī’s Caṇḍīmaṅgalakāvya of the sixteenth century, and Raghunandana’s Durgāpūjātattva of the late sixteenth to early seventeenth century.44 But it is not until the Umā-saṅgīt of the late eighteenth century that the explicit link is made between Umā, Durgā, daughters, and the Pūjā season. The same evidential lacuna is true of the iconographic evidence. Bengali sculptures of the Buffalo-Slayer, from the earliest discovered samples in the seventh century45 up to late Pāla period art in the twelfth century, mirror their famed predecessors from places such as Mahabalipuram, Aihole, and Udayagiri: they depict Durgā killing Mahiṣa. Indeed, prior to the Mughal period, no sculptures of Durgā Mahiṣamardinī anywhere in Bengal, whether free-standing or on temple walls, include the four children.46 When Gaṇeśa and Kārtik, or Lakṣmī and Sarasvatī, do appear in conjunction with a goddess in Bengali sculptures, the goddess in question is in her peaceful, gentle aspect as Pārvatī, or Pārvatī and Śiva, not in her manifestation as the battle queen. This of course makes sense, considering the popularity from the early Gupta period of Umā-Maheśvara statues of the husband-and-wife team, together with Kārtik or Gaṇeśa.47

By the late seventeenth century, however, terracotta temples were displaying Gaṇeśa, Lakṣmī, Kārtik, and Sarasvatī on engraved slabs together with Mahiṣamardinī, although their positioning was not always at Durgā’s side, but above and below her. In a few cases, the inclusion of children heralded the loss of Durgā’s martial aspect entirely: the Goddess was accompanied by her husband instead of her lion and buffalo enemy.48 In other cases, the children softened the Goddess; in 1910, members of the Jalpaiguri Rāj family added Gaṇeśa, Kārtik, Lakṣmī, and Sarasvatī to the previously lone image of Mahiṣamardinī, and her skin color became paler.49

Causes of this eventual iconographic change can only be surmised; as far as I am aware, no scholar in English or Bengali has attempted to construct a connected narrative that makes sense of all known evidence. With the rise of Sultanate power in the region after the thirteenth century, Brahmanical influence and culture were challenged and eclipsed, leading to the proliferation of folk forms of religion.50 Some of these were expressed in literature such as the Maṅgalakāvyas, discussed earlier, where local deities were humanized, their desires and powers portrayed through stories based in the Bengali environment. Maṅgalakāvyas eventually gave way to the āgamanī and bijayā songs on Umā, as well as to a genre of street entertainment known as kabigān, in which popular culture, including the marriage of little girls to aged husbands and their return once-yearly to the natal homes, was satirized by groups of musicians who vied with each other in extemporaneous versifying. The same regionalization and adoption into folk culture is also true of art, evidence of which becomes especially plentiful in the form of brick temples from the sixteenth century. Such temples to Brahmanical deities began to appear in western Bengal concurrently with the rise of Mughal power; their façades were covered with panoramic battle scenes; mythological friezes, on the life of Kṛṣṇa, Rāma, or Durgā’s battle with Śumbha and Niśusmbha; depictions of social life (hunters, soldiers, kings, etc.); divine or lay figures in rows; and floral and geometric patterns.51 Especially by the eighteenth century secular life makes its way onto these friezes: bearded priests and servers attend to Durgā, violinists serenade her, and her devotees are even dressed in European clothing. On other slabs, Gaṇeśa can be seen feeding from a bottle, zamindars are strutting about in Western dress, and European boats sail into Bengali ports.52

After the late seventeenth century some of the engraved slabs on the walls of terracotta temples displayed tableaux of Durgā that bear striking resemblances to other contemporaneous popular artforms, painted paṭs and clay lakṣmīsarāis. Paṭs were watercolor paintings done on scrolls or thick paper, and were used either for decoration purposes or in Pūjā contexts, sometimes prior to the adoption of clay images. Lakṣmīsarāis originally derived from the painted bottoms of clay pots but eventually attained their own freestanding autonomy as decorated clay dishes used during Pūjā time.53 Among the many examples of Durgā-centric paṭs and lakṣmīsarāis that I have seen, if the children are included at all they are stationed above each other, or above and below the Goddess. Sometimes even Śiva appears over her head. This spatial arrangement of the figures may reflect space considerations, but it also conforms with the pattern established for the clay image tableaux on display at Pūjā time in homes of zamindar families.

The temple slabs also closely resemble the ways in which the earliest-known clay images were being produced for the families of the wealthy from the early seventeenth century (see chapter 4): those slabs that included the four children arranged them in two groups of two, with Lakṣmī placed above Gaṇeśa and Sarasvatī above Kārtik, they often added sculpted copies of the painted backdrops, or cālcitras, used behind the clay images of the Goddess and her family, and the lion mounts upon which the Goddess sat frequently sported horses’ heads. Some scholars infer from these similarities that the temple slabs of Durgā with children were sculpted in imitation of what was visible already in the homes of the rich, Pūjā-sponsoring landowners—i.e., that elite ritual was influencing local popular art.54 Says Malavika Karlekar, “It is possible … that as Durga Puja became increasingly popular in the zamindari homes of Bengal of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the goddess was ‘domesticated.’ She symbolised the supreme mother who would destroy so as to protect her children and the children of forthcoming generations.”55

It is extremely difficult to know which of these artforms arose first or can be considered primary in influence, although, as we shall see in chapter 4, it is likely that the worship of Durgā with the two-dimensional paṭ preceded that with the clay image. Perhaps the best one can do is to postulate some sort of folk tradition reaching back into the fifteenth century through which, as Durgā Mahiṣamardinī’s festival was increasingly popularized and as her link with Śiva’s wife became more explicit, she inherited the deities iconographically (but not textually) portrayed as accompanying Pārvatī: her two sons, Gaṇeśa and Kārtik, and her two “sister goddesses,” Lakṣmī and Sarasvatī, who together provided the auspiciousness, learning, and fortune necessary for householder life. The next step in the process, however, the association between Mahiṣamardinī/Umā (and children) with the myth of her homecoming at the Pūjā season, may owe more to the influence of the zamindars than to popular custom.

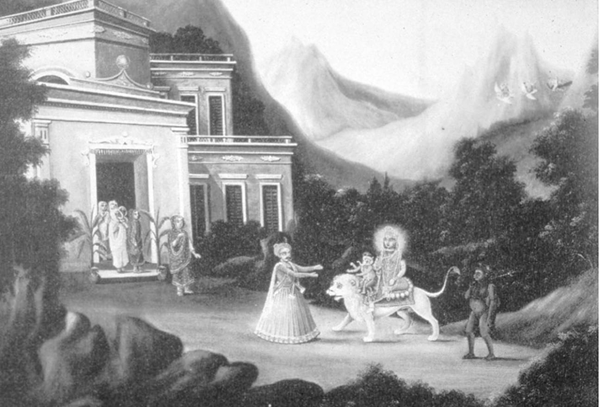

It is possible to conjecture that it was the rājas’ aggrandizement of the festival that led to the specific conjunction of (a) Durgā, (b) Umā the daughter of Menakā, (c) a festival during which daughters return home, and (d) the conception of Umā as the universal daughter of the land. Because there have never been many permanent Durgā temples in Bengal—still an interpretive mystery56—her festival represents a once-yearly chance to welcome and worship her. And since the Pūjās were originally organized under the jurisdiction of the elite, it was they who set the trends and built up the holiday during the annual event. So the tradition of bringing daughters to their natal villages would have occurred with the growth of the harvest festival, which was being lavishly patronized as Durgā Pūjā by the elite.57 Additional considerations include the following: nineteenth-century oils of Menakā and Girirāj depict Umā’s parents as affluent zamindars (fig. 3.3)58; it was the wealthy who patronized the composers and singers who made the Umā theme popular at the Pūjā season; these elite scions sometimes composed such songs themselves;59 and their estates were the site for the performance of all daughter–centered songs and rituals. In an English article from 1952 by noted historian Jadunath Sarkar, he says of the Pūjās of his youth seventy-five years earlier, “There was an artistic rivalry between village and village [in terms of boat immersions]. The zamindar’s pansay proudly rowed up and down (music playing on its foredeck) for some time.” As the boats went back, the rowers sang in chorus, “‘I have sent away my golden Gauri with the vagabond Shiva. The fair is broken up and Darkness has descended.’ … I can still feel this tragedy of the Dusserah day.”60 Many of the rituals emphasizing the daughter-goddess also bespeak confinement and prosperity; the poor probably could not have afforded pet birds, could not have presented their departing daughters with such gifts, and did not have the leisure time to listen to the āgamanī and bijayā song cycles.

FIGURE 3.3. Āgamanī ([Home]coming). Traditional iconography with a European landscape and distant horizon. Oil painting, ca. 1890. British Museum 1990.10–31.01.

Whether one traces the origin of the Pūjā’s daughter aspect to a folk or women’s stratum or to a set of practices fanning out from zamindari custom, the fact remains that the first explicit evidence we have for the Mahiṣamardinī-Umā-daughter-Pūjā confluence is the Umā-saṅgīt literary genre, which does not predate the mid-eighteenth century and was largely the product of poets writing under the patronage of zamindari courts. From where the original impetus for such a layering of ideas came, therefore, it is hard to tell. But once established, such multifaceted conceptions of the Goddess, social meanings of her festival, and domestic rituals connected with it were adopted and patronized by elite culture as its champions strove to publicize and popularize Durgā Pūjā.

Vātsalya, Even Viraha: Longing and the Pūjās

Although one can claim historically, visually, and textually that the primary meaning of the Pūjās relates to the conferral of strength, or śakti, the destruction of obstacles, and the consequent enjoyment of blessing, it is arguable that the real underlying feeling, or rasa, of the festival is one of tenderness for the returning beloved. Heads of old family Pūjās are proud to continue their traditions in part because, unlike the community pandals, erected yearly and then dismantled, their Durgā, the daughter, still has a home to return to.61 Artisans who create the clay images feel similarly: for months they have lovingly modeled, painted, and adorned their Durgās, and when the goddesses leave for the homes and pandals of the city, their makers feel bereft. Said the president of the Kumartuli Artisans Association, “For how long we have been decorating and dressing the girl. And at the start of the puja we feel as if our house’s daughter has gone. Believe me, when everyone else is rejoicing, we here are in the darkness of the cremation ground.” Mohan Bhanshi Rudra Pal agreed: “It’s a feeling of a pain that’s almost like bidding goodbye to your daughter when she leaves for her in-laws’ home.”62

For some Bengalis, the desire for the daughter completely overshadows the importance of the martial Mahiṣamardinī. This is reflected playfully and poignantly in certain nineteenth-century āgamanī songs, many of which refuse to accept that the darling daughter is really the slayer of demons. For the sake of comparison, recall that in the Sanskrit Purāṇas the primary mode of identifying Pārvatī with Durgā and Kālī is through battle scenes, when Pārvatī assumes the form of a warrior goddess to help the male gods slay demons. Moreover, the Sanskrit myths evince no distaste with such transformations of Śiva’s demure wife; in fact, her darker sides add to her glory.63 Here, in the Umā-saṅgīt, however, the opposite could not be more in evidence, for the Bengali poets portray Menakā accepting only reluctantly the equation of her daughter with Kālī and Durgā.

For instance, Menakā dreams that Umā has become black—i.e., Kālī—and this terrifies her.

Giri,

what a nightmare!

I dreamed I saw Umā in the cremation grounds.

She was black,

roaring with laughter.

Her hair was a mess,

and she was naked,

sitting on a corpse.

There were three eyes

on her terrible face;

a half-moon shone on her forehead.

She wandered about on a lion

with a group of yoginīs.

I got so scared

looking at her.

Get up! Get up, lazy Mountain!

I’m consumed with worry;

hurry to Kailasa,

and bring my ambrosial Umā home.64

In other poems, Menakā hears rumors from Kailasa:

I got some news from Kailasa!

Oh, my God!

What are you doing, Mountain Lord?

Go, go,

go see if it’s true.

Śiva has put on Umā

the burden of their household life,

while he does yoga on the cremation grounds!

Seeing him thus engaged,

people seize the chance, seize his wealth

and scatter to the winds.

Look what happened! His moon ended up

in the dome of the sky, the Ganges now

courses the earth, his snakes

live in the underworld, and his fire

endangers forests!

Umā thought so hard

about Śiva’s habits

that she turned into black Kālī!

My daughter, a king’s daughter,

deranged from hurt feelings?!

Now she wears strange ornaments—

completely shameless.

And this is the worst of it:

I hear she’s drunk!65

In these and other similar poems, Umā becomes black Kālī, or skin-andbones Cāmuṇḍā, because of her poverty, misery, and indifferent husband. It is only the mixed tears of mother and daughter that once a year wash away her darkness, at home.

Another poem of this variety depicts Menakā actually receiving her daughter at the Pūjā time but being unable to recognize her.

Mountain,

whose woman have you brought home to our mountain city?

This isn’t my Umā;

this woman is frightening—

and she has ten arms!

Umā never fights demons

with a trident!

Why would my spotless, peaceful girl

come home dressed to kill?

My moon-faced Umā

smiles sweetly, showering nectar.

But this one causes earthquakes

with her shouts and the clattering of her weapons.

Who can recognize her?

Her hair’s disheveled, and she’s dressed in armor!

Rasikcandra says,

If you recognize her,

your worries will vanish.

But it’s in this form

that the Mother destroys my fear of death.66

This ambivalence toward the Sanskritic Durgā and Kālī spills over into the Bengali presentations of the Sanskrit “Devī-Māhātmya,” or Caṇḍī, sung daily by Brahman priests during the Durgā Pūjā festivities. Menakā wants nothing of this dry, Sanskrit ritual text, when Umā, or the real Caṇḍī, is coming home.

Get up, Giri, get up!

Here, hold your daughter!

You see the Caṇḍī and teach the Caṇḍī,

but your own Caṇḍī has come home!67

Giri,

where is my Ānandamayī?

When is She coming?

How all the Brahmans bustle about,

installing pots at their posts!

I guess my Caṇḍī has gotten stuck somewhere,

listening to the Caṇḍī.68

Dāśarathi Rāy (1806–1857), a famous poet in this literary genre from the mid-nineteenth century, describes Menakā looking everywhere for Umā. She searches in the ritual ghaṭ, or water pot, and she also inspects the Sanskrit Caṇḍī, but cannot find her daughter anywhere.69 This is symbolic of how the Śākta poets prize the Bengali daughter goddess over the Sanskritic martial goddess. To the extent that it is Durgā Mahiṣamardinī who arrives on the sixth evening, Menakā’s fears have come true.

One way of describing or understanding the feelings expressed for Umā is to use language derived from the Vaiṣṇava context—a context extremely germane to Śākta religiosity, given the proximity and mutual influence of these two major groups in Bengal. Many of those who wrote poems on Śākta themes also wrote poems about Kṛṣṇa and Rādhā, and the six-century literary tradition associated with the latter deities colored Umā as well. For instance, Menakā’s motherly love for and attachment to her daughter Umā (vātsalya bhāva) can be compared to Yaśodā’s emotions for Kṛṣṇa, and Sucī’s for Caitanya. The myth cycles of all three include scenes of the mothers staring at the roads by which their children must return home, and having nightmares about danger to their loved ones. Just as Yaśodā occasionally glimpses the true nature of her son, but quickly retreats behind the veil of adoring motherhood, so also Menakā is frequently told about Umā’s real identity as the Mother of the World, but can rarely hold the knowledge. Moreover, when these children eventually leave their mothers—Umā for Kailasa, Kṛṣṇa for Mathura, and Caitanya for Puri—the plants and animals in their natal homes droop and faint. Some Śākta poets even copy Kṛṣṇa’s penchant for butter and cream, creating scenes in which Menakā feeds Umā hand-churned milk products.70 The most astonishing example of these Vaiṣṇavizing tendencies comes from Rāmprasād Sen, in an early composition called the Kālīkīrtan. Here his Umā is a cow-girl who takes her cows to pasture and plays to them on her flute. She and Śiva sport together in flower groves reminiscent of those belonging to Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa, and she even has a Rāsalīlā dance.71 Therefore, the sweetening and humanizing of Umā, as well as the desire to concentrate on her as a daughter, may well owe much to the influence of Vaiṣṇavism and its articulation of vātsalya bhāva. Although there is nothing overtly erotic in the Umā-centered story of Menakā’s longing, one could perhaps see a touch of viraha here as well—that is, the pain of love-in-separation that the mother endures for her distant girl.

The significance of this attachment to the daughter Umā, especially as rendered through the āgamanī and bijayā songs, is underscored by the degree of emotion expressed by those who sense its disappearance in modern Pūjā contexts. It is true, in fact, that the Umā-saṅgīt is far less noticeable in Pūjā festivities than it apparently once was. One can hardly find occasion to listen to the songs anywhere, in homes or in Pūjā pandals, the only exception being at public concerts or on cassettes and DVDs. In other words, the very songs that once heralded the coming of the Pūjā festivities are now strangely absent from their intended context. Bengali interviewees indicated several types of reason for this absence: the increasingly fast pace of community and even home Pūjās, where there is no time to stop for the lugubrious tunes of a mother’s heartache; the slow disappearance of singing troupes who would travel house to house, performing; the impact of urban culture, not only in cities but also in rural settings; the easing conditions of marital life, such that Menakā’s grief is no longer relevant to present-day women; and the lack of complementarity between the āgamanī and bijayā songs and the Sanskrit, “Devī-Māhātmya”–inspired ritual context of the Pūjā, which does not reinforce the presence of Umā.72

People looking back nostalgically on the Pūjā celebrations of their youths often cite the decline of interest in the Umā-saṅgīt as a major cultural loss. Even in the 1940s and 1950s their demise was being lamented: “The raucous gramophone blaring the latest cinema tunes brings a heartache for the Agamani songs, our counterparts of the carols and the Nativity songs.” Their haunting quality seems to “have gone with the mellow lamp-light, the street-singer and the unbought grace of life…. It is sad to think that these songs are no longer sung.”73 The Pūjā, now shorn of the Umā-saṅgīt, is a “lifeless, soulless, mechanical affair, … the logical conclusion to the process of urbanization” and loss of pride in [our] heritage. Nevertheless, because the āgamanī and bijayā songs are in [our] background, “we still find them moving.”74

When one hears Bengalis reminiscing or planning on how to bring back the true spirit of the Pūjās, it is this domestic, feeling, daughter aspect that is most often singled out for urgent attention. One can find notices of revival movements going back to the mid-twentieth century: village women are said to be coming to Calcutta to restore the emotional heart of the Pūjās by singing the songs of Gaurī’s return to her father’s place;75 various famed folk and devotional singers such as Rāmkumār Caṭṭopādhyāy and Amar Pāl always bring out Umā-saṅgīt cassettes at the festival season, hoping that they will catch on; and in 2001 a Delhi-based Bengali named Āśis Ghoṣ made it his mission to revive the art of kathakatā, narration interspersed with āgamanī and bijayā songs, in which one person acts all the different roles. In a number of newspaper interviews, he explains that the stories he has heard of women’s hardships creep into his telling of the tales. “The 80-minute stage show speaks almost entirely on behalf of the female folk,” he says. “Menaka and Uma’s story is still the story of contemporary India.”76

At its broadest level, one can interpret the sense of longing for the daughter Umā in terms of cultural nostalgia. Though first used in 1688 to refer to a medical condition of homesickness (nostos + algia) noticed in Swiss mercenaries, “nostalgia” is now considerably widened in semantic scope.77 It typically refers to a desire to return to a romanticized past conceived less in terms of place than of time—a time in one’s early life when certain experiences, feelings, places, or people are recalled with heartfelt longing. Nostalgia is not a simple memory of the past, for it carries with it a painful awareness of lack and a desire for (impossible) restoration. Roberta Rubenstein, in her work on the yearning for specific visions of “home,” calls nostalgia a “haunted longing” and describes its “painful awareness, the expression of grief for something lost, the absence of which continues to produce significant emotional distress.”78

Causes for nostalgia vary; at its most general, nostalgia is set in motion by present fears, anxieties, or uncertainties that would appear to be calmed by a memory of or a return to the past.79 In chapter 1 we saw a nostalgic craving among the middle classes for an aristocratic zamindari culture that connotes, in addition to family cohesion, leisure, and true faith, pride in a uniquely Bengali past. Place (or recreated place) and a displayed material artifact, the Durgā image, serve as the trigger for or site of the nostalgic sensibility. Here, in this chapter, the nostalgia is oriented less at architecture, custom, or artifact than at lost time, lost youth: one rues one’s own aging and that of one’s family and friends; one longs for childhood, whether one’s own, one’s children’s, or one’s culture’s. Indeed, the “universal exile from childhood” is what Jean Starobinski calls nostalgia.80 Rubenstein mirrors this in her discussion of mothers who mourn younger versions of themselves when they had not yet lost centrality in their children’s lives; they are pained by time’s passing and their own stagnation in it.81 Mr. Umazume, the man responsible for starting the revival of the nearly lost Awaji puppet tradition in Japan in the 1940s, commented to Jane Marie Law about his motivations: “A terrible sense of loss … Something slipping away. My childhood. The sounds … It was painful to feel something so meaningful sliding through your fingers, and yet do nothing but talk about the good old days.”82 Often related to the yearning for childhood is the identification of urbanization as the underlying cause of deplored change. Law found this as the operative reason for the dying puppetry in Awaji, and identified in her informants a bias toward the rural as the ultimate source of authenticity.83 Grief at the passing of an entire cultural tradition was therefore linked to a championing of “the old ways” as envisioned before industrialization rendered them seemingly obsolete.

If cultural mourning is “an individual’s response to the loss of something with collective or communal associations, a way of life, a cult, a homeland, a place with significance for a larger group, a history from which one feels exiled,” then the healing afforded by nostalgic thinking or artforms is—to borrow Rubenstein’s thoughtful phrasing—an imaginative fixing of the past by revising its meanings in and for the present.84 One can never return home or recapture one’s childhood, but a certain pleasure is derived by remembering it or even attempting physically to reproduce it. This is so even if—whether one is aware of it or not—the relived or recreated will always be censored, a false version of a once-complex experience.85

Theorists also note the degree to which the nostalgic sentiment can be used to generate lucrative rewards for the tourist and entertainment industries, can be co-opted by big businesses for advertising, and can even aid the candidacy of particular political parties. Nostalgia has made the past, says David Lowenthal, “the foreign country with the healthiest tourist trade of all.”86 Nevertheless, those committed to encouraging nostalgic renewal feel that the gains are worth these potentially undercutting side-effects. Mr. Umazume, for instance, believed strongly that reviving the Awaji Nongyō tradition for theatrical rather than ritual performances was far better than having it lost forever. Even in theater the puppets might transform people.87

Much of this elucidation of cultural nostalgia applies also to the case of Bengal. As the biggest yearly Hindu festival, no matter what one’s sectarian leanings, Durgā Pūjā evokes the same sort of passionate anticipation in children that Christmas does; if one is removed from those memories by increasing age, or by a forced emigration from one’s home, as in the case of refugees from Bangladeshi villages after 1947 and 1971, or by choosing to live in the diaspora, the Pūjā takes on a rosy hue and symbolizes the essence of what has been lost through the passage of time. Many urban Bengalis still speak of “home” as the village of their forebears, even if they have never visited it, and many of them who were brought up in the village recall with wistfulness the Pūjās as they occurred there. No matter how much one enjoys the hoopla of the urban Pūjās, one aches for the rural, truly “authentic” festivals in remembered villages. In new environments, joining in or even initiating the Pūjā celebrations is one way of adjusting. “Nostalgic memory, creatively reconfigured, [becomes] one source through which [refugees can build] a new communal culture and construct a new collective identity to serve their changed needs.”88 Refugees or immigrants also aim to engender in the second generation a nostalgia for their parents’ past through clubs, associations, cultural events, and educative programs. Hence the significance to Bengalis, wherever they live, of cultural soirees in which the Umā-saṅgīt is performed by professional singers: retrieved ritual, even in an entertainment milieu, is still important, still heartwarming and stirring.

Thus even if Durgā Pūjā had no association with Umā, as the national Hindu festival par excellence it would still provoke feelings of bittersweet nostalgic craving. As Benedict Anderson and many others after him have shown us, the nation is often conceived in the vocabulary of kinship or of home;89 the expectation that wherever one finds Bengali Hindus one will encounter Durgā Pūjā celebrations and Kālī temples implies that “home”—or Bengal or India—is intimately tied to the Mother, to Bhārat Mātā, as a means of self-expression. The fact that this festival, in addition, honors a mother–daughter bond built on feelings of loss and longing accentuates the love-in-separation, or viraha, at the heart of the event. Bengalis join Menakā in yearning for Umā as they yearn as well for their own daughters, for their own childhoods, pasts, homes, and Durgā Pūjās of old.