Henry III’s Unfinished Crossing Tower

King Henry III devoted a substantial part of his long reign (1216–72) to the reconstruction of Westminster Abbey in the prevailing Gothic style, which was heavily influenced by contemporary building in France. The Confessor’s church represented Anglo-Norman architecture and liturgical requirements which, after two hundred years, no longer suited Benedictine needs and aspirations. It was impossible to accommodate the contemporary monastic liturgy in the very short, apsidal eastern arm, let alone find space there to create a shrine in honour of St Edward the Confessor. Reconstruction began in 1220 by adding a large Lady Chapel to the eastern arm, thus creating much more liturgical space. The chapel no longer exists, having been superseded in the early sixteenth century by Henry VII’s Lady Chapel [4], but its plan is reconstructible from archaeological evidence.4

The extent to which Henry was the initiator of the Abbey’s reconstruction is uncertain since the work was begun by the monks, but on such a lavish scale that they quickly ran out of funds. In 1240, Henry stepped in to rescue the situation, and in so doing embarked on what was without doubt the most ambitious and expensive church-building project in English history. The Lady Chapel was completed in 1245, after which the demolition and reconstruction of the eastern arm, crossing and transepts of the old building followed. The work progressed at a staggering rate, so that by the mid-1250s the masonry shell of the eastern parts of the church was complete. The master mason (architect) was Henry of Reyns, who was well versed in the vocabulary of the latest French Gothic architecture, but was possibly English by nationality.5 Thus he was presumably the designer of the new crossing tower that replaced King Edward’s.

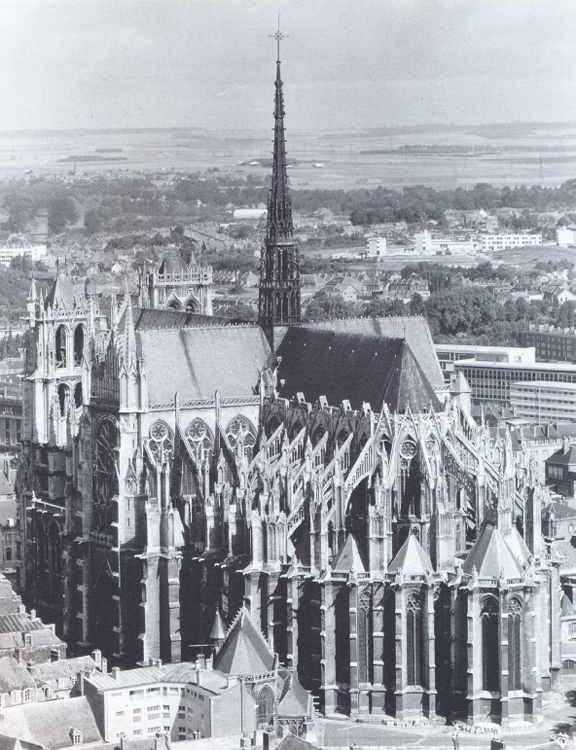

4 Westminster Abbey from the east in 1936, showing the emphasis placed on octagonal features in Henry III’s original scheme, and further elaborated by Henry VII, whose Lady Chapel appears in the foreground. Almost certainly the square base of the crossing tower was intended to support an impressive octagonal lantern. Henderson 1937

What form of Crossing Tower was envisaged?

It was the norm for major transeptal churches in the early thirteenth century to be provided with a crossing tower (see appendix). Most often in England that took the form of a low, stone-built lantern that did not project very far above the ridge-lines of the four abutting roofs. These lanterns, which were square in plan, had simple lancet windows in the sides, and were often provided with intra-mural passages and newel-stairs housed in turrets at the corners. Moreover, lanterns were open from the church floor upward, although stone vaults or ceilings were often subsequently inserted at the level of the crossing arches, thus eclipsing the lantern effect (as occurred at Wells, Lichfield and Salisbury cathedrals).

5 Various attempts have been made to reconstruct the appearance of Henry III’s church, and this one by A.E. Henderson shows it from the southeast. The tower and spire – copied from Salisbury Cathedral – are far too elaborate, and the easternmost polygonal apse (Lady Chapel) should project further. Henderson 1937

It is generally assumed that early Gothic lantern towers were topped by a pyramidal lead roof, or a timber and lead spire. In most cases, however, the towers have either been totally rebuilt, or raised in height – often in the fourteenth century – to form full-blown crossing towers, capped with stone or timber spires (e.g. Salisbury and Lichfield cathedrals), thus removing all evidence for the original termination. Almost certainly the roof structure at Westminster would not have been exposed to view from below, being hidden by either a flat ceiling or a timber vault.

The present diminutive lantern, which hardly peeps above the ridge-line at Westminster Abbey, clearly owes nothing apart from its square plan to Henry III or Henry of Reyns. So what were their intentions for the design of the crossing at Westminster? Moreover, how much of their tower was actually constructed, and what happened to it? Unfortunately, there is little solid evidence surviving to demonstrate the form of the structure, and none above the point where it emerged through the roof. However, various strands of architectural, archaeological and historical evidence, bolstered by comparanda from elsewhere, enable us to make both reasoned deductions and educated guesses. We must not, however, be seduced by some older artistic reconstructions which, though exquisite in themselves, are more representative of mid-fourteenth-century Salisbury than of Westminster a century earlier.6 [5]

First, we should consider the overall design of the thirteenth-century abbey church as an indicator of the type of lantern tower that it is likely to have borne. Not only were important elements of the monastic liturgy performed in the crossing but, uniquely in England, this was – and still is – also the location where the coronation of monarchs takes place. It is therefore inconceivable that Henry would have considered a squat lantern with a simple pyramidal roof as an appropriate treatment for the crossing, especially since he was attempting to outshine the contemporary Gothic architecture of France. Moreover, he was demolishing the lofty and clearly impressive tower raised by King Edward, and the successor to this needed to be no less worthy. The new nave was destined to be the tallest in England, and it needed to be surmounted by a lantern tower that made a clear architectural statement. This deduction is confirmed, a fortiori, when the Abbey is viewed from the east. [4] If we ignore the elaborate decoration of Henry VII’s Chapel – but not the physical presence of a large apsidal chapel here, since there was one from 1220 onward – the multi-tiered composition of the church’s architectural form is immediately apparent. More than that, all the higher elements point upwards to heaven in a most demonstrative fashion: the sanctuary roof, the high gables of the transepts and the pinnacled corner-turrets. They all demand a pointed centrepiece standing high above the crossing. The inadequacy of anything akin to the present stumpy lantern to provide that focus requires no emphasizing. Henry’s lantern tower needed to be both tall and capped by either a spire or a high-pointed roof.

Although up to parapet level the crossing was square in plan, it does not follow that the tower had to continue above the roof in the same form. Indeed, a large square tower would not have been congruent with the rest of the building, and outwardly would now give the appearance of being a later medieval addition. It can be ruled out as an option. One of the most striking features of Henry’s design was the ubiquitous use of octagons and half-octagons. The chapter house, described by the contemporary chronicler Matthew Paris as ‘beyond compare’, was octagonal. The terminations of the new Lady Chapel, and the presbytery and its ambulatory were all half-octagons, while the four two-storey chapels attached to the ambulatory had the form of octagonal apses. Even stair-turrets and pinnacles were eight-sided. It is therefore plausible to conclude that the lantern tower above roof level should have been octagonal too. The eastern view of Westminster must have borne a striking resemblance to that of Amiens Cathedral, although the latter was endowed with a greater chevet of apsidal chapels.8 [6] It is not certain what crowned the crossing at Amiens in the thirteenth century, the present two-staged lantern and needle-like flèche dating from 1528. But again the architecture demands an octagonal lantern or spire.

Existing Evidence

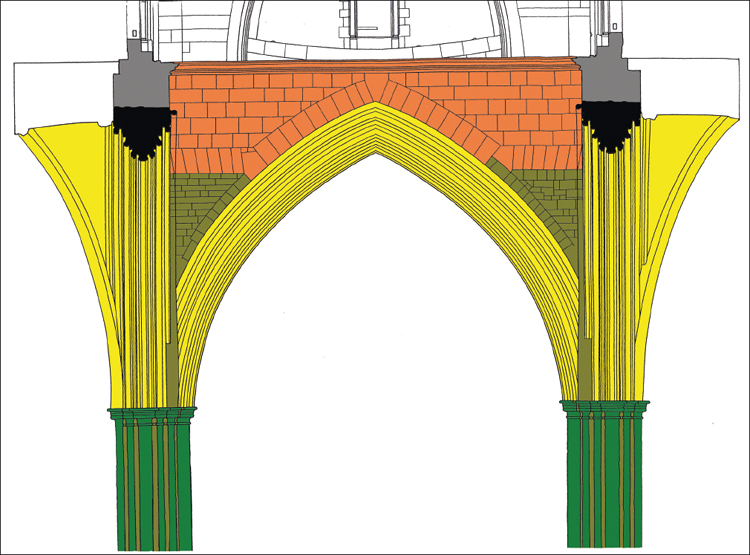

The Westminster crossing is square in plan, measuring 44¼ ft (13.5 m).9 [7, 8A] The piers comprise an octagonal core of Purbeck marble with four massive, attached shafts on the cardinal faces, and four smaller ones on the diagonal faces. Interspersed between these are eight further small shafts also attached to the core of the pier. [9] All the shafts have moulded bases, and the complete ensemble stands on a high octagonal plinth. The piers are freestanding for one-third of their height, i.e. up to arcade-capital level, whereupon they engage with the ashlar masonry of the triforium and above that the clearstorey. [8B, 12] A single shaft-ring marks the point of transition. [11] The shafts have well moulded capitals, also in Purbeck marble. Rising from these are the four huge, pointed crossing arches which are heavily moulded and probably of Caen stone.10 [10] This fine-grained limestone from Normandy was extensively employed for moulded and carved work in Henry’s abbey.

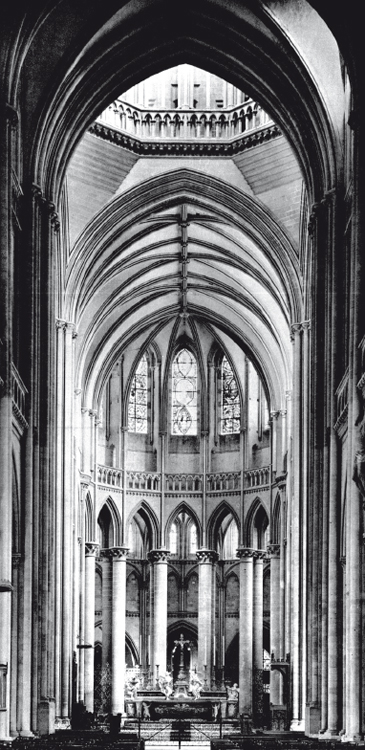

6 Amiens Cathedral from the south-east, showing an array of octagonal-apsidal components and the lantern and flèche of 1528. J. Feuillie/CNMHS/SPADEM

The slenderness of the crossing piers, relative to their great height, has suggested to some commentators that a massive tower rising several storeys above the roof, and crowned by a stone spire, was neither envisaged nor capable of being supported, although Sir Christopher Wren clearly thought otherwise: p. 29, and modern engineering calculations have confirmed that such a structure was sustainable (p. 90). Nevertheless, the emphasis was probably on providing a lantern tower, rather than a bell tower. In the thirteenth century many of the greater churches were augmented with a fashionable campanile, an entirely separate structure which housed the major bells. Westminster Abbey possessed one and it stood to the north-west of the church, on the site later occupied by the Middlesex Guildhall (now Supreme Court of the United Kingdom).11 It was an elaborate structure, square at the base and with a staged octagonal superstructure. The campanile, which was demolished in 1750, is shown in Wyngaerde’s view of Westminster. [30] There was a closely similar bell tower in a comparable location at Salisbury Cathedral, and that was demolished in 1790. Again on the north-west, Chichester Cathedral has a somewhat later campanile, which still stands.

7 Henry III’s crossing and north transept, viewed from the south transept. Author

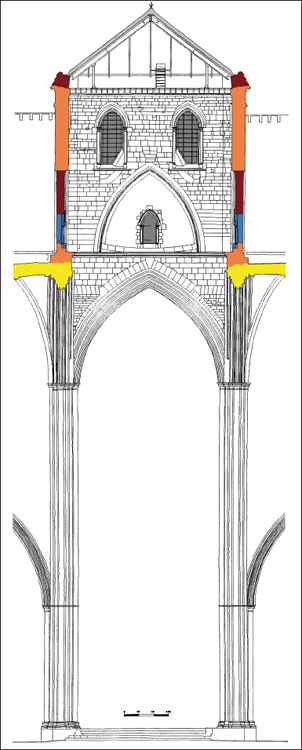

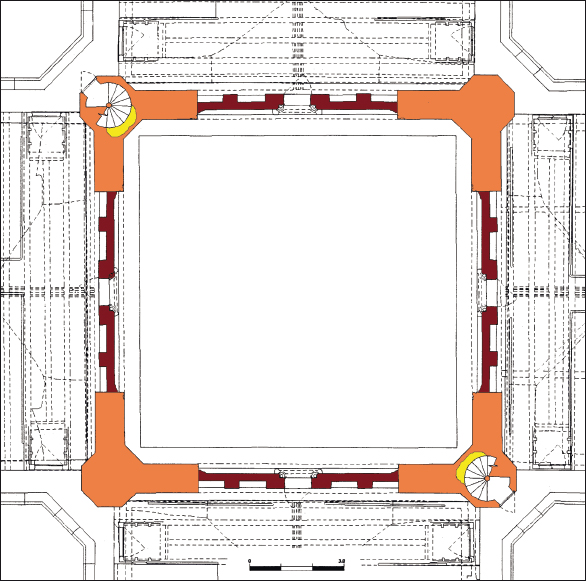

8 A (lower). Plan of the crossing at quire pavement level. B (upper). Plan of the northern side of the crossing and the first bay of the north transept at triforium level. North is at the top. Scale of 3 m. The Downland Partnership

9 Details of the Purbeck marble capital and base of the south-west crossing pier, drawn in 1822. Neale and Brayley 1823

All that remains today in the crossing of the mid-thirteenth-century work are the four great arches and some of the masonry comprising the internal angles of the tower at the lowest level. [10, 11, 12] Nothing dating from this period is visible externally. However, there are four original stone corbels in the form of human heads, set low down in the corners of the lantern, just above the point where the crossing arches meet one another.12 Each head supports a Purbeck marble base which was designed to carry a small, free-standing corner-shaft. [13] This confirms that the ubiquitous marble shafting in the Abbey was intended to continue inside the lantern tower, but that is as far as the physical evidence takes us. Doubtless there were capitals on the tops of the shafts, although how high they rose is indeterminable. Also, what did the capitals support? Most likely, they carried small vaults which decorated the underside of the corbelling or the squinches that would have been necessary at the corners of the crossing, if the lantern above was octagonal in plan (p. 13).

10 The upper part of the crossing and junction of the arches. View west. Author

11 East elevation of the interior of the crossing and lantern tower. The Downland Partnership

12 The top of the south-east crossing pier and springing of the arches. Author

13 Detail of the northeast crossing pier with a corbel in the form of a male head supporting a Purbeck marble base; the latter was intended to carry a detached shaft, rising in the angle of the lantern. Author

How much of the Lantern Tower was actually built?

The critical question is: was Henry’s tower ever built above roof level? Since nothing attributable to the thirteenth century appears to survive today at eaves level or above, there has long been a presumption of the negative. However, the crossing had to be finished, whether temporarily or permanently, in a way that provided a satisfactory, watertight junction between it and the four abutting roofs of the presbytery, nave and transepts.13 The framing of the four high roofs also relied on a solid central feature to retain the trussed-rafters in an upright position. If the intention had been to erect a square tower, then the masonry of the crossing would almost certainly have been taken up to ridge level, thus providing the essential abutments for the roofs. The resultant structure, if left unfinished at that point, would have had an appearance closely similar to what we see today. The fact that the present squat lantern does not have thirteenth-century walls provides a strong argument that it was not originally square in plan above eaves level. However, the possibility of an alternative scenario must be considered, namely that the square tower rose to ridge level, converting to an octagon thereafter, but a later modification involved lowering the corners and beginning the octagon at eaves level. Moreover, there is a further complication to take into account: two of the eighteenth-century corner-turrets embody vertical columns of medieval ashlar masonry that clearly belonged to earlier stair-turrets. [14] Whether that work dates from Henry III’s period, or slightly later, is uncertain, but it confirms unequivocally that a medieval tower once stood at least to the height of the present one.14

14 Plan of the lantern tower at main eaves level, with the adjoining parapet walks and high roofs. Key: yellow, medieval; orange, Hawksmoor, 1724–27; maroon, Wyatt, 1803–05. North is at the top. Scale of 3 m. The Downland Partnership and author

We know for certain that Henry III did not live to see his lantern tower finished, because a temporary ceiling had to be erected over the crossing two years after his death for the joint coronation of his son, Edward I, and Queen Eleanor, on 19th August 1274. What was described as the ‘new tower over the quire’ had to be ‘boarded up’.15 Henry’s failure to finish the lantern is easily explained in terms of building logistics. Having completed the crossing and transepts in the late 1250s, the priority in the 1260s would have been to press on with the reconstruction of the nave, and only when that had been completed would the masons have returned to build the crossing tower or lantern. Work on that could proceed at a later date from scaffolding erected externally, and the provision of a temporary ceiling over the crossing would ensure that building operations did not interfere with monastic observance below. Meanwhile, the emerging first stage of the lantern tower would simply have been provided with a temporary, low-pitched roof. A decorative ceiling may well have been inserted inside, even though it was a relatively short-term measure. The painted timber ceiling at Peterborough Cathedral, dating from the early part of Henry III’s reign, or that of his Painted Chamber in the Palace of Westminster (destroyed by fire, 1834), hint at what might have covered the crossing in the Abbey.

Hence, all the evidence points to the lantern having never been finished in the thirteenth century: the walls were taken up only to a sufficient height to form abutments for the four high roofs. We must return again to the question of the plan of the lantern tower, since that is not wholly resolved. The crossing piers and arches define a square up to eaves level, but what rose above that, to ridge level and beyond?16 If the first stage of the tower, from eaves to ridge level, was square, then how do we explain the absence today of thirteenth-century masonry at the four angles? Externally, all visible masonry is eighteenth century, as it also is internally, except for the first 2.0 m of Reigate ashlar above each of the corbels in the corners (already mentioned). The present interface is at such a low level (far below the eaves) [15] that it cannot conceivably represent the point at which Henry’s masons stopped building: it would have been impossible to weatherproof the structure at this level. Hence, it can only mean that some thirteenth-century masonry has been taken down, to well below roof level, and then the walls have been built up again. The interface between the two periods of work is so clear and consistent in all four corners that something much more fundamental than the repair of a localized failure is implied. [59] So what could have been the motivation for demolishing all four original corners of the tower?

15 East crossing arch, showing the survival of mid-thirteenth-century masonry. Key: green, Purbeck marble piers; khaki, spandrels; yellow, arch and vault mouldings. Hawksmoor’s masonry of 1725–27 is shown in orange. The disposition is similar in the other three crossing arches. The Downland Partnership and author

It has already been argued on stylistic grounds that the lantern stage is more likely to have been octagonal in plan than square. If this is accepted, then there is an inevitable corollary: the four salient angles of the crossing had to be merged into the diagonal faces of the lantern stage just above the level of the high vaults. In the Middle Ages, the transition from four to eight sides was normally effected either by corbelling or by constructing diagonal arches (squinches) across the corners of the tower; and upon those supports the four angled sides of the octagon were then raised. The level at which the surviving thirteenth-century masonry ceases coincides exactly with the position from which the squinches, or corbelling, would be expected to spring. The evidence that there was once an octagonal lantern tower, supported on the side-walls and the corbelled angles of the crossing, is thus compelling. The removal of those angled supports in the sixteenth century, and the subsequent making-good of the masonry at the corners of the crossing, gave us what we have today (below, p. 51). The transition from a square crossing to an octagonal lantern is well demonstrated by the corbelled arrangement at Coutances Cathedral in Normandy.17 [16, 17]

Hence, circumstantial, architectonic and archaeological evidence all combine to suggest that Henry’s masons constructed an octagonal base for the intended lantern stage on top of the walls of the crossing. Once that had been achieved, there would have been solid abutments for the high roofs, making everything complete and watertight up to ridge level. The open top of the octagon would have been given a temporary roof while building progressed on more urgent fronts elsewhere. When Henry III died in 1272, work on the new abbey was halted, and only the first five bays of the nave had been reconstructed in the Gothic style. The momentum was never regained and the nave was not finished for another two hundred years, and it was nearly five hundred years before the western towers assumed their present form under Nicholas Hawksmoor (p. 63). Small wonder, then, that work on the lantern tower was not resumed for a considerable time.

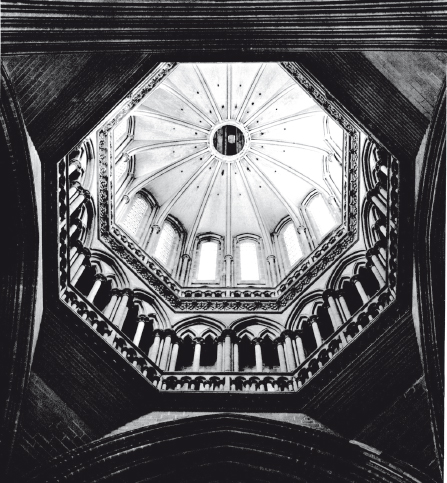

16 Coutances Cathedral. View east through the crossing, showing the base of the octagonal lantern and the corbelling that carries its diagonal faces. Bony 1951

17 Coutances Cathedral. The crossing tower viewed from below, showing the corbelled supports, galleried basement stage, lantern with sixteen windows and the ribbed vault with a bell-manhole. Bony 1951

Fortuitously, there is a potential illustration of the octagonal base of the Henrician lantern in a Tudor drawing of the Abbey. [20, 22] The architectural significance of this source seems to have been largely overlooked by previous scholars, or dismissed as imaginary.18 The drawing is discussed in detail in the next chapter, but here it is relevant to note that two periods of construction are potentially indicated, one being thirteenth century and the other late medieval. Stylistically, it is obvious from its architectural form that the crenellated upper part of the lantern and the cupola could not date from the mid-thirteenth century, but there is no reason why the octagonal base upon which they were founded should not have been of that era. Thus, we may propose with some confidence that when Henry III died the crossing of his new church was surmounted by an octagonal stone plinth, 13.4 m (44 ft) across, upon which it was intended to erect a lantern tower befitting the grandeur of the rest of the building.

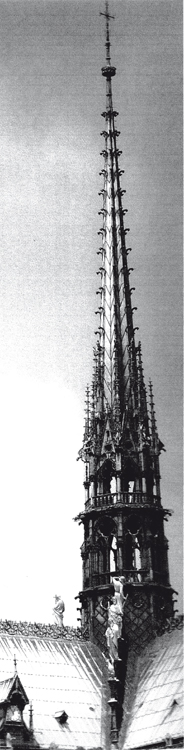

Like so much else at Westminster, the lost design was doubtless heavily influenced by contemporary French architecture. France already had a long tradition of building octagonal crossing towers, some of which were of extreme monumentality, such as Romanesque Toulouse, or early Gothic Coutances. At Westminster, aesthetics would probably have demanded that the tower comprised two lantern stages of stone construction (as in the Romanesque Notre Dame at Clermont-Ferrand). But here we run out of direct evidence and can only resort to speculation. Above the second stage might well have been a construction in timber and lead. The French were also noted for their predilection for crowning roofs and lanterns with lightweight openwork structures, often culminating in tall, needle-like flèches. The cathedral of Notre Dame, Paris, has just such a feature over the crossing: it comprises an octagonal basement, two openwork lantern stages and an immensely tall flèche. While the present structure is a mid-nineteenth-century recreation by Viollet-le-Duc, its medieval predecessor is depicted in a drawing of c. 1530.19 [18, 19]

18 Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris. Detail from a birds-eye view of the Ile de la Cité, from the west, drawn c. 1530. It shows the medieval octagonal lantern and a tall flèche rising above the crossing. © Musée Notre-Dame

Gaining Access to the Lantern Stage

Before leaving the subject of Henry III’s lantern, the issue of access needs to be addressed. There are newel stairs in the outermost corners of the transepts, rising to parapet level. Provision had then to be made for getting from the main parapet walks into the lantern, and thence into its roof or spire. French octagonal lantern towers were normally accompanied by four turrets rising from the corners of the crossing below, and one or more of these would contain a newel stair. The turrets could be either integrated with the diagonal sides of the octagon, or freestanding (with a short flier or other form of link to effect the stair connection). The Tudor drawing shows no stair-turret at the north-west corner, only the shouldering at the transition of the square to the octagon. Consequently, we can be certain that in the early sixteenth century the Westminster lantern was not flanked by a quartet of stair-turrets. But that does not imply that none were intended in Henry III’s church.

19 Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris. Viollet-le-Duc’s reconstructed two-stage lantern and flèche. Erlande-Brandenberg 1999

The resolution to this conundrum is happily provided through a combination of Sir Christopher Wren’s observations, and archaeology. In his report on the Abbey in 1713, Wren stated: ‘The original intention was plainly to have had a steeple [i.e. a tower], the beginnings of which appear on the corners of the cross[ing], but left off before it rose so high as the ridge of the roof ’.20 Remains of the thirteenth-century corner-turrets were still extant and had commanded Wren’s attention: confirmation of this appears in his drawing of 1715, showing the plan and internal elevation of the upper part of the crossing. He showed detached octagonal turrets at the corners, two of which (north-west and south-east) contained newel stairs.21 [31] Wren had intended to rebuild these. In the event, it fell to Hawksmoor to reconstruct them in 1726–27, although not as freestanding turrets: he incorporated them in the corners of a square lantern of his own design (p. 53).

Not only do the angle-turrets have their ancestry in the thirteenth century but, as noted above, careful examination of the ashlar lining inside both the south-east and north-west turrets has revealed medieval masonry in situ. [14] Part of the curving internal wall of the stair has survived, almost up to the level of the roof ridges, where it was incorporated in the later structure. This confirms that the lower sections of at least two – and presumably all four – of the detached corner-turrets were built. Thus, when Henry III died, the crossing of Westminster Abbey would have been crowned by the basement stage of an octagonal lantern and the stumps of four detached corner-turrets: all would have spawned temporary cappings.