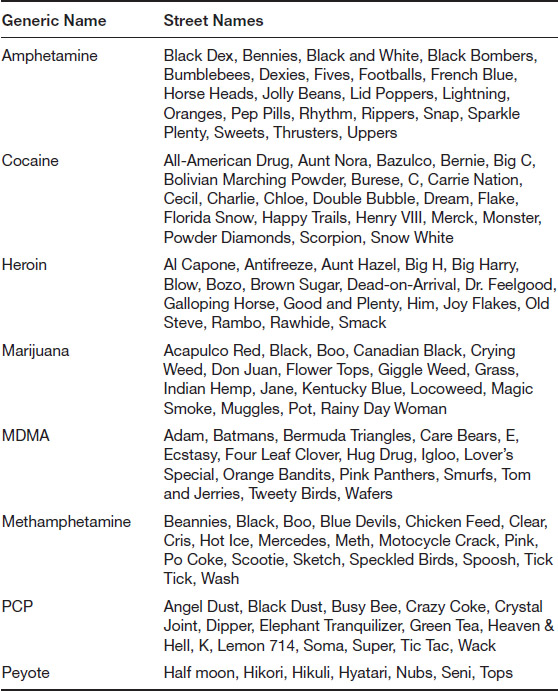

Table 1.1 Some Street Names for Illegal Drugs

The nation was startled by the news at the end of 2015. The U.S. National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) issued a report that the death rate among Americans had increased in the previous year, a trend that had not been seen in over a decade. Although progress in combating deaths from cancer, heart attacks, and other traditional disease-killers had continued to decrease for the most part, death rates began to move upward for a few specific conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease, suicide, and substance abuse. NCHS reported, for example, that the death rate for drug overdoses had increased by 137 percent between 2000 and 2015, a trend that reflected more than anything the growing epidemic of opioid abuse and addiction (Rudd et al. 2016). Ironically, the group most at risk for the increase in death rates was relatively well-to-do middle-class white males, a category of Americans that had been experiencing a drop in death rates for many decades. The country was shocked and baffled at the new trend. Had substance abuse become the new killer “disease” capable of sweeping through the nation in coming decades?

The use of natural and synthetic products that alter one’s consciousness has been part of human culture as far back as records exist. In some instances, it even predates any written or pictorial accounts that humans left behind. In 1992, for example, Jan Lietava, of Comenius University in Bratislava, reported on the discovery of a number of natural herbs with mind-altering properties, including ephedra, at a Neanderthal burial site in the Shanidar region of Iraq dating to at least 50,000 bce. Lietava wrote that the substances found at the site had “marked medical activity” (Lietava 1992). The discovery is thought to be the earliest evidence of drug use by humans.

Most other drugs with which humans are familiar today have long histories also. The first references to the cultivation of the cannabis plant, from which marijuana is produced, date to at least 10,000 bce. The precise use of these plants is not clear, however, as the plant is used not only for the production of marijuana but also for the manufacture of hemp, a valuable fiber used to make cloth. The earliest evidence of a cannabis product, in fact, is a piece of cord attached to pottery dating to about 10,000 BCE in China. The first reliable evidence that the plant was also used to make a product that could be smoked dates to somewhat later, about the first or second century CE, also in China. Myths dating to the period claim that the Chinese deity Shen Nung tested hundreds of natural products, including marijuana, to determine their medical and pharmacological properties (Iversen 2000, 18–19). These myths form the basis for a very early Chinese pharmacopeia, which describes the hallucinogenic properties of marijuana, which is called ma, a Chinese pun for “chaotic” (Iversen 2000, 19).

The use of marijuana as an intoxicant also has a long history in Indian culture, where its first mention dates to about 2000–1400 BCE in the classic work Atharvaveda (Science of Charms). According to legend, the Indian god Shiva became embroiled in a family argument that so angered him he wandered off into the fields, where he lay down and fell asleep under a leafy cannabis plant. When he awoke, he tasted a leaf of the plant and found that it so refreshed him that it became his favorite food. Thus was born the tradition of making and consuming a concoction of the cannabis plant known as bhang in honor of the Lord Shiva at many religious ceremonies, a tradition that continues today (Booth 2003, 24; see also Cannabis: India 1500 BC; Grierson [1894]).

The history of opium and other opiates (derivatives or chemical relatives of opium) is similar to that of marijuana and other psychoactive substances. Although there is some evidence that the poppy was cultivated and used by the Neanderthals, the first concrete, written evidence of its use dates to about 3500 BCE in lower Mesopotamia. Tablets found at the Sumerian spiritual center at Nippur describe the collection and treatment of poppy seeds, presumably for the preparation of opium. The Sumerians gave the name of hul gil, or “joy plant,” to the poppy, almost certainly reflecting the sensations it produced when eaten (Kritikos and Papadaki 1967). Thereafter, the plant and the drug are mentioned commonly in almost every civilization of antiquity, where they were used for medical and, apparently, psychoactive reasons, probably in association with religious ceremonies. Interestingly, opium was almost universally ingested by mouth rather than by smoking. In fact, the first mention of the drug’s use by smoking is not found until about 1500, when the Portuguese introduced the practice, then thought by the residents of all other nations as being a “barbaric and subversive” custom (Childress 2000, 155).

Although marijuana and opium were apparently not known in the New World, the Western Hemisphere had its own psychoactive drugs of choice, one of which was mescaline, derived from the peyote cactus (Lophophora williamsii). As in the Old World, this drug was apparently popular thousands of years ago, although it became known to Europeans only with the Spanish conquests of South America in the sixteenth century. One of the early chroniclers of the history of peyote was a Spanish priest, Bernardino de Sahagun, who estimated from extant documents that the drug had been in use for at least 1,800 years before the Spanish arrived in the New World. De Sahagun’s estimate is problematic, however, partly because the conquistadors so aggressively destroyed all historical documents of the natives on which they could lay their hands. Later ethnologists and archaeologists think his estimates are conservative, and that the drug was used at least a thousand years earlier. One writer has placed the first use of peyote in the New World of at least 8,000 years ago (Spinella 2001, 344). In any case, it was still being widely used for both religious and recreational purposes when the Spaniards arrived, and the conquerors’ efforts to abolish this practice were largely unsuccessful.

One of the most thorough and detailed observers of native practices in the region, Danish ethnologist Carl Lumholtz, described peyote ceremonies he observed during an extended trip to Mexico:

The plant, when taken, exhilarates the human system and allays all feeling of hunger and thirst. It also produces colourvisions… . Although an Indian feels as if drunk after eating a quantity of hikuli [native name for peyote], and the trees dance before his eyes, he maintains the balance of his body even better than under normal circumstances. (Lumholtz 1902, 364)

The other psychoactive plant native to the New World is the coca plant, Erythroxylum coca. Recent studies have shown that the plant was being used at least 3,000 years ago. Two of 11 mummies from a burial area in northern Chile contained small quantities of the drug, whose age was determined by carbon-14 dating. Historically, archaeologists had previously set 600 CE as the earliest date for which good evidence of the use of coca has been set. That evidence consists of mummies that had been buried with a supply of coca leaves and whose cheeks were deformed by a bulge characteristic of those who chew leaves of the plant (Peterson 1977, 17). As with peyote, the Spaniards attempted to abolish the practice of coca use but were entirely unsuccessful. As they discovered, coca provides the chewer with energy and stamina, qualities of considerable benefit especially to those who lived in the thin air of the high Andes, and also of use for the exhausting manual labor in mining and other occupations to which the natives were assigned by the conquistadors.

The use of psychoactive substances has often been the subject of dispute within nations and regions. Indeed, Chapter 2 of this book discusses in some detail some of the issues surrounding the use of such substances in the United States and the rest of the world today. An example of the historical controversies about the use of psychoactive substances is the Opium Wars of the mid-nineteenth century between China and Great Britain. Although opium had been known in China and used for medical purposes for hundreds of years, by 1800 it had been banned for recreational use. Coincidentally, however, Great Britain had just come into control of the world’s largest source of opium with its conquest of the Indian subcontinent. That situation was a tinderbox, with the British eagerly searching for a market for the massive amounts of opium they now controlled and the Chinese determined not to permit the importation of the drug to their country.

The British took advantage of this opportunity in 1836, when they bribed officials at the port of Canton to allow them to bring opium into the country. Before long, the drug was widely available throughout China, and the number of people addicted to its use rose to an estimated two million (Chrastina 2009). The Chinese government finally decided to take vigorous action against the smuggling of opium into their country by the British in 1839. Emperor Tao-kuang appointed a trusted bureaucrat named Lin Tse-hsü to lead an anti-opium campaign across the country. Lin was especially aggressive against British merchants in China who trafficked in opium and against merchant ships who were attempting to deliver the drug at the port of Canton. As the year progressed, skirmishes between the Chinese and British increased in number and severity, and war between the two nations broke out in mid-1840. The result of the conflict was a foregone conclusion, with the British then having one of the largest and strongest military establishments in the world. In 1842, the Chinese sued for peace, which was confirmed by the Treaty of Nanjing, signed on August 29 of that year. The treaty called for China to open five ports to foreign trade, to pay significant reparations to Great Britain, and to cede Hong Kong to the British. The treaty settled matters temporarily, but discord between the two nations continued, and war broke out again in 1856. As before, the British prevailed, and the war ended with the Treaty of Beijing in 1860. Again, the Chinese were required to open more ports to foreign trade (ten this time) and to pay very large reparations to Great Britain and its ally, France. (For an excellent overview of the Opium Wars, see Beeching 1975.)

Controversies over the use of psychoactive substances have extended to every material that might fit that description. Even a substance that hardly attracts opprobrium today—coffee—has been the subject of controversy at a number of times in the past. In 1511, for example, the governor of Mecca banned all coffeehouses within his district. His action was based on the belief that coffee is an intoxicant and therefore forbidden by Islamic law. To his misfortune, the governor was later overruled by his superior, the sultan of Cairo, and paid with his own life.

After a coffee craze swept through Europe in the seventeenth century, similar concerns about its use arose in a number of locations. In 1600, for example, a number of Christian clerics asked Pope Clement VIII to ban coffee because it came from the land of the infidels (the Islamic world) and it would cause drinkers to lose their souls. After tasting the new drink, however, Clement had a somewhat different take on the issue. He could not believe, he said, that such a delicious drink could be evil. Instead, he decided to “fool the devil” by baptizing coffee and allowing its free use among all Christians (Grierson 2009).

The pope’s decision did not, however, resolve the controversy over the use of coffee in many parts of Europe. The disputes that arose illustrate that fact that such controversies may or may not arise solely out of the medical or health effects of a substance. In some cases, for example, objections to the rapid spread of coffeehouses were raised by tavern owners, who probably cared little one way or another about the psychoactive effects of coffee, and a great deal more about the competition coffeehouses posed to their businesses. Like earlier Christian leaders, they argued that coffee was a product of unbelievers, and that good Christian men should drink only the brew that had been prepared traditionally by monks: beer.

Other efforts to close coffeehouses did focus on their supposed health risks. Perhaps the most famous of these efforts was the “Women’s Petition against Coffee,” published in 1674 in London. In this petition, a group of women asked the authorities to close coffeehouse because the drink was harming their sexual lives with their husbands. They complained of the “Grand INCONVENIENCIES accruing to their SEX from the Excessive Use of that Drying, Enfeebling LIQUOR” (Clarkson and Gloning 2003). (Some critics have observed that women’s greatest complaint about coffeehouses, to the contrary, was that they were not permitted to enter such establishments [Grierson 2009].) The Women’s Petition drew a comparable response from men, or at least a man purporting to represent the male position on coffeehouses. The “Men’s Answer to the Women’s Petition against Coffee” was a long harangue that insisted that the coffeehouse is “the citizen’s academy, where he learns more wit than ever his granmum taught him [and that] … ’Tis Coffee that … keeps us sober.” He continues: “[Let] all our wives that hereafter shall presume to petition against it, be confined to lie alone all night, and in the day time drink nothing but bonny clabber” (Clarkson and Gloning 2005). If there is any lesson to be learned from this contretemps, and the longer history of coffee itself, it is that virtually any substance with some effect on a person’s mental or physical condition is likely to be the subject of controversy at some point in history.

The aforementioned review provides only a modest introduction to the earliest history of drug use in the Old and New Worlds. Similar stories could be told for other naturally occurring psychoactive plants and their products, such as tobacco, alcohol, caffeine, and psilocybin, as well as a host of synthetic products developed in the last century, such as amphetamine, the barbiturates, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), and MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine). Those stories would require a series of books much larger than this work, however, although salient points in that history will be discussed in this and following chapters. (For more on the history of psychoactive substances, see also Austin 1978; Merlin 2003; Rudgley 1999.)

Any discussion of substance abuse makes use of a number of terms whose definitions are essential to a clear understanding of the subject. Some of the most important of these terms are the following.

Drug is probably the most fundamental term used in talking about substance abuse, but it is also the term with the greatest variety of meanings. According to Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary, for example, the two major definitions of the term refer to its medical use and its recreational use. In the former instance, the term drug is defined as:

(1) a substance recognized in an official pharmacopoeia or formulary (2) a substance intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease (3) a substance other than food intended to affect the structure or function of the body (4) a substance intended for use as a component of a medicine but not a device or a component, part, or accessory of a device.” In the latter instance, the term is defined as “something and often an illegal substance that causes addiction, habituation, or a marked change in consciousness. (Merriam-Webster 2016) (The terms pharmacopoeia and formulary refer to books or lists of drugs, usually prepared and issued by recognized authorities such as medical groups or governmental agencies.)

Legal and illegal are terms that describe substances that are or are not permitted by law to be manufactured, transported, sold, and consumed. The term legal drugs refers both to prescribed drugs, that is, drugs that can be obtained only with a medical professional’s prescription, and over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, which are freely available to any consumer without a prescription. A number of substances that produce psychoactive effects are also legal in the United States. These substances include amyl nitrite, betel nuts, caffeine, catnip, henbane, hops, a variety of inhalants, kava kava, ketamine, mandrake, nitrous oxide, nutmeg, and tobacco. Illegal drugs cannot be obtained legally except by clearly specified medical applications. Legal and illegal drugs are also known as licit and illicit drugs, respectively.

Substance abuse is a term now more widely used than the formerly popular drug abuse. The term has become more common at least partly because it can be used for a wider variety of materials that are not in and of themselves illegal, such as alcohol, tobacco, and caffeine, which may also be abused in much the same way as illegal drugs, such as marijuana, cocaine, and heroin.

The term substance abuse itself is somewhat vague, since it can refer to a variety of conditions ranging from relatively harmless to life-threatening. In his book Illegal Drugs, Paul Gahlinger describes four levels of drug abuse (Gahlinger 2004, 90). The first level he calls “experimental use,” because it involves the first exposure people have to drugs. They “try out” a glass of beer, a cigarette, or a lid of marijuana. For some people, that is as deeply as one becomes involved in “substance abuse.” They do not enjoy the experience or decide not to go any further. (Although, as Gahlinger points out, even this level of drug abuse is an illegal act for substances such as marijuana and cocaine, although not for alcohol and tobacco.) The next level of drug use is one that Gahlinger labels “recreational use.” It refers to cases in which a person takes a drink, has a cigarette, or uses an illegal drug from time to time “just for the fun of it.” The person’s life is not disrupted in any way by this occasional, low-key use of a substance. Gahlinger calls the next level of drug use “circumstantial use,” because it includes those occasions when substance use develops into a certain pattern: a person uses a drug to deal with a personal problem, because of the feelings the drug produces, or just to be sociable with others. Again, drug use at this level is not necessarily harmful, but it may be the gateway to the fourth level, “compulsive use,” or, as most people would describe the situation, an addiction.

Professional caregivers, such as physicians, psychologists, psychiatrists, and counselors, encounter this whole range of substance abuse behaviors, but usually provide a more detailed and sophisticated definition of the conditions they see. The standard reference in the field of psychiatry, for example, is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition, often referred to simply as DSM-5. DSM-5, released in 2013, differs substantially in the way it defines substance abuse disorders from its predecessor, DSM-IV. DSM-5 recognizes substance abuse disorders for nine categories of drugs: alcohol; caffeine; cannabis; hallucinogens; inhalants; opioids; sedatives, hypnotics, and anxiolytics; stimulants; and tobacco. It also defines four levels of impairment resulting from a substance abuse: impaired control (over use of the substance), social impairment (involving interruption of one’s normal daily activities), risky use (that results, for example, in a person’s placing himself or herself into physical danger), and pharmacological indicators (involving development of tolerance or withdrawal symptoms) (Gorski 2013; Horvath 2016).

Narcotics is a term that was traditionally used for opioids, drugs that are derivatives of or similar to opium. The word narcotics comes from the Greek term “narko-sis,” which means “to make numb.” Today, the term is used more generally for any substance that causes numbness or stupor, induces sleep, and relieves pain.

Psychoactive is an adjective used for any substance that acts on the central nervous system (CNS) and alters one’s consciousness or mental functioning. The word psychotropic is sometimes used as a synonym for “psychoactive.” A number of other terms with the prefix psycho- are also used to describe certain specific types of psychoactive drugs. Psychotomimetic drugs, for examples, are compounds that produce symptoms similar to (“mimic”) those of a psychosis. Psychedelic drugs are those that produce altered sense of consciousness or distorted sensory perceptions.

One large class of psychoactive drugs are the hallucinogens, which, as their name suggests, cause hallucinations, or perceptions of images and events for which there is no real stimulus. Psychoactive drugs have been used throughout history for a number of purposes: as medicines, as recreational drugs, and as a means for achieving spiritual experiences in religious ceremonies. Drugs used for the last of these purposes are sometimes called entheogen substances, from the Greek words for “to create,” “the divine,” and “within.”

Generic is a term used to describe a particular form of a drug, or the name given to such a drug. Most drugs have at least two names, and often, they have three. The first name is its systematic, or scientific, name. For example, the systematic name for the compound that we commonly call aspirin is sodium acetylsalicylic acid. The systematic names for compounds are derived from rules established by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and have the advantage of unambiguously identifying every different compound in the world. Such names are essential for researchers because they prevent any confusion whatsoever as to the substance about which a person is talking. The practical difficulty with IUPAC names is that they can be long and quite beyond the understanding of the ordinary person. The systematic name for the drug known as Ecstasy, for example, is (RS)-1-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-N-methylpropan-2-amine.

The generic name for a compound does not necessarily follow rules like those established by IUPAC. It is a simpler, shorter name to which one can more easily refer. The compound officially known as (±)-1-phenylpropan-2-amine, for example, is more commonly known by the generic name of amphetamine. Proprietary formulations of drugs always carry a specific brand name also that associates that formulation with the company that makes the drug. Some brand names for amphetamine (sometimes mixed with other compounds) are Dexedrine, Adderall, Biphetamine, Desoxyn, and Vyvanse.

Finally, illegal drugs almost always have a number of street names, nicknames by which they are known among substance abusers, professionals, and the general public. The list of street names is very long indeed. Table 1.1 shows only a sample of some of these names and the drugs for which they are used.

A much more detailed list of street names can be found on the Internet at White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, “Street Terms,” http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/streetterms/Default.asp.

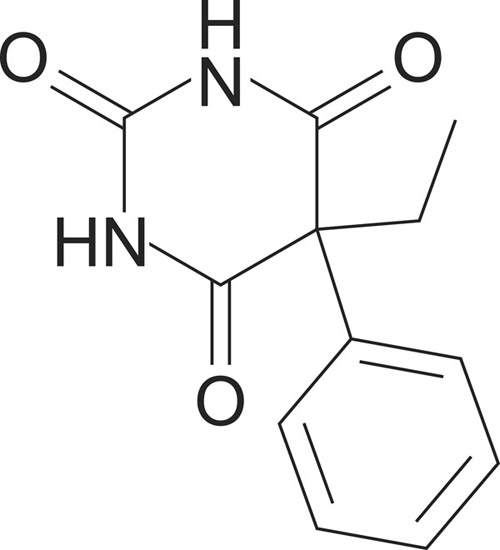

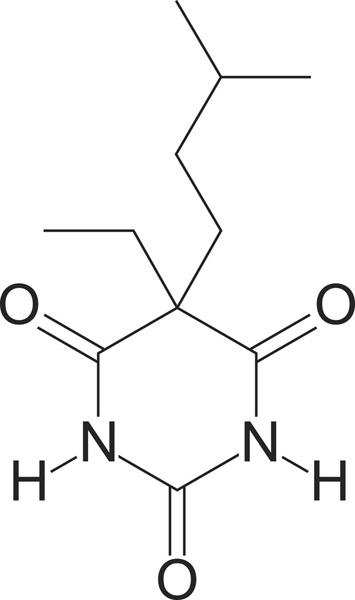

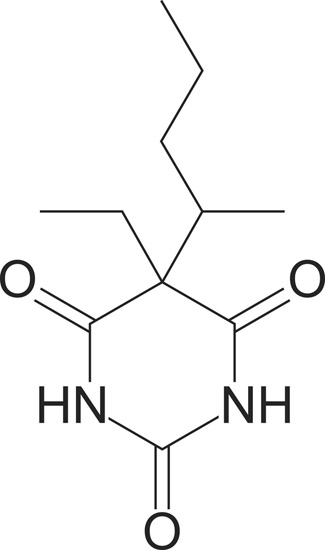

In many cases (as in the last part of this chapter), it may be useful to discuss the specific characteristics of individual drugs, such as cocaine, heroin, and PCP. In other cases, it is helpful to focus on the common properties of large classes of drugs. Drugs can be classified in a number of ways: on the basis of their chemical structures, as to their medical uses, by the mental and physical effects they produce, and on the basis of their legal status. A chemical system of classification organizes drugs according to their chemical structures. One might speak, for example, about the amphetamines, which are all derivatives of the specific compound, amphetamine; barbiturates, which are all derivatives of barbituric acid; and the benzodiazepines, which are all derivatives of the chemical compound by that name. Figure 1.1 shows three members of the barbiturate family with its parent compound, barbituric acid.

Another common system of classification is based on the effects produced by drugs. The most common categories included in such a system are depressants, stimulants, and hallucinogens. The first group of substances, the depressants, gets their name from the fact that they depress the CNS, reducing pain, relieving anxiety, inducing sleep, and, in general, calming a person down. Some common depressants are opium and its relatives, cannabis, alcohol, the barbiturates, the benzodiazepines, muscle relaxants, antihistamines, and antipsychotics. Depressants are commonly referred to as “downers” because they reduce the activity of the CNS.

Figure 1.1b Phenobarbital

Figure 1.1c Amobarbital

Figure 1.1d Pentobarbital

Stimulants have just the opposite effect. They increase the activity of the CNS, promoting physical and mental activity. Stimulants are used medically to treat a number of conditions that are characterized by depression, such as sleepiness, lethargy, and fatigue; to improve attentiveness and concentration; to promote weight loss by decreasing appetite; and to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and clinical depression. Because of their effects, compounds in this category are sometimes called “uppers.” Some common stimulants are amphetamine and its chemical analogs, caffeine, cocaine, Ecstasy (methylenedioxymethamphetamine), and nicotine. (In chemistry, analogs [or analogues] are chemical compounds similar in structure and function to other chemical compounds.)

Hallucinogens differ from stimulants and depressants in one important way. The latter classes of drugs amplify normal mental sensations, increasing those sensations in the case of stimulants and decreasing them in the case of depressants. Hallucinogens, by contrast, produce qualitatively different mental states, such as the perception of objects and events that do not, in fact, actually exist. The experiences produced by hallucinogens are, in some respects, similar to other kinds of socalled out-of-body experiences, such as those experienced during dreaming, meditation, and trances. Ironically, the one effect that is not produced by hallucinogens is hallucination, an experience in which a person completely accepts as real an event or object that has no basis whatsoever in reality. To someone who has taken a hallucinogen, by contrast, there is almost always some realization that the bizarre experiences he or she is having do have at least some basis in reality.

Hallucinogens can be subdivided into three groups: psychedelics, dissociatives, and deliriants. The term psychedelic comes from two Greek words, pysche, meaning “soul,” and delos, meaning “to reveal.” The term thus suggests a chemical that allows a person to look into her or his innermost self to discover his or her authentic person. For this reason, psychedelics (as well as other hallucinogens) have a very long history of use in religious and mystical ceremonies since they are thought to allow a person to go beyond the simple (and limited?) reality of everyday life. Dissociatives are chemicals that disrupt normal nerve transmissions in the brain so that one loses touch, to a greater or lesser extent, with the physical world. He or she literally “disassociates” from that world with the result, as with psychedelics, that one can focus on one’s innermost soul without the distraction of physical reality. Deliriants are a form of dissociative that have even more extreme effects on an individual. A person who takes a dissociative may be aware of the mental changes he or she is experiencing, while someone who has taken a deliriant is probably not aware of these changes. Of all hallucinogens, deliriants are most likely to produce true hallucinations.

Some categories of drugs in addition to stimulants, depressants, and hallucinogens are antipsychotics, used to treat psychoses because of their calming effects; antidepressants, used to treat depression and similar mood disorders; inhalants, abused by some individuals as a way of achieving some type of altered mental states, such as a “high”; and marijuana, which is often listed as a drug group in and of itself.

Finally, drugs can be categorized on the basis of their legal status in any particular nation. This method of categorization is of special interest and concern, of course, because it clarifies which substances are legal for individuals to use and which are not. The basis for classifying the legal status of drugs in the United States was established by the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. That law created five classes, or “schedules,” of drugs according to their medical use and potential for abuse. Drugs placed in Schedule I, for example, currently have no approved legitimate medical use in the United States and a high potential for abuse. Some Schedule I drugs include the stimulant cathinone, the depressant methaqualone (Quaalude), the psychedelic MDMA, and most opiates. Schedule II drugs include a number of substances that, while strongly subject to use as recreational drugs, do have some legitimate medical uses. These drugs include the amphetamines, most barbiturates, cocaine, morphine, opium, and phencyclidine (PCP). An excerpt of the law creating the drug schedules and a list of drugs in each schedule are to be found in Chapter 5 of this book.

Drugs produce their effects on the body by acting on the brain. Specifically, they alter in one way or another the mechanisms by which nerve messages are sent from one part of the brain to another part of the brain. The transmission of a nerve impulse within the CNS, of which the brain is a major component, is a two-step process, one of which is an electrical mechanism, and one of which is chemical. A nerve impulse passes along a neuron (nerve cell) by means of a constantly changing electrical charge on the membrane of that cell. When that electrical impulse, called an action potential, reaches the outermost edge of a cell, known as an axon, it initiates the release of chemicals from the axon into the space between that neuron (the presynaptic neuron) and some other adjacent neuron (the postsynaptic neuron), a space known as the synapse, or synaptic gap. These “message-carrying” chemicals are known as neurotransmitters. Some examples of neurotransmitters are acetylcholine, epinephrine (adrenaline), γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), dopamine, serotonin, and nitrous oxide. After a neurotransmitter has crossed the synaptic gap, it attaches itself to a section of the dendrite on a receiving cell. A dendrite is a short projection in a neuron designed for the acceptance of neurotransmitters from another neuron. The point at which a neurotransmitter docks is called a receptor site. A specifically designed receptor site exists for each different type of neurotransmitter. Once a neurotransmitter has bonded to a receptor site on a dendrite, it stimulates the dendrite to initiate an electrical impulse, similar to the one that traveled through the first neuron. That electrical impulse then passes through the dendrite and into the neuron cell body, repeating the process of nerve transmission from the presynaptic neuron. Meanwhile, the neurotransmitter is released from the dendrite, travels back across the synaptic gap to the presynaptic neuron, and is available for reuse in transmission of the nerve message. (For a visual representation of this process, see The Brain 2011; The Chemical Synapse 2012 [first half]; Nerve Conduction 2016.)

Most drugs exert their effects on the CNS by altering the action of neurotransmitters at some point in the process described previously. Stimulants, for example, tend to prevent the reuptake of a neurotransmitter at the very end of the process. As a result, neurotransmitters tend to accumulate in the synaptic gap and reinsert themselves into receptor cells on the second neuron, which is, as a result, restimulated over and over again. This repetitious stimulation is responsible for the increased activity observable in the brain after the ingestion of a stimulant.

Other stimulants have other modes of action. Nicotine, for example, causes its effects because its structure is somewhat similar to that of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Just as acetylcholine works by stimulating an acetylcholine receptor in a dendrite, so nicotine exerts its influence by stimulating a receptor similar to that for acetylcholine, called the nicotinic receptor. Caffeine operates in yet another way on the nervous system. It exerts its effects by acting as antagonist at a dendrite receptor site for the neuromodulator adenosine. A neuromodulator is a substance that affects the rate at which nerve messages pass through the brain. In the case of adenosine, the effect is to slow down this process. Thus, whenever an adenosine molecule locks onto one of its receptor sites in a dendrite, no other neurotransmitter can enter that site, and a nerve message is interrupted. The brain’s reaction rate slows down as a result of this event. If caffeine is present in the bloodstream, it may also enter the brain and dock at a receptor site normally reserved for adenosine molecules. A molecule that is able to act in a manner similar to some other molecule to produce a diminished response is said to be an antagonist for the second molecule. (By contrast, a molecule that acts like another molecule to produce an augmented response is called an agonist.) Thus, caffeine is an antagonist for adenosine. The only difference between the two substances is that caffeine has no effect on the rate at which nerve messages are transmitted. When it docks at an adenosine receptor, it prevents an adenosine molecule from docking there also, preventing a slowdown in the brain’s activity. A person who has had a cup of coffee, then, does not experience the “slow down” responses, such as drowsiness, that might typically result from the action of adenosine in the brain.

As one might expect, the action of depressants on the nervous system is quite different from that of stimulants. In most cases, the neurotransmitter most commonly affected is γ-aminobutyric acid, generally known as GABA. GABA is a somewhat unusual neurotransmitter in that it tends to reduce the rate at which nerve transmission takes place. (Most neurotransmitters increase brain activity.) That is, the flow of GABA from the presynaptic neuron to the postsynaptic neuron causes changes in the structure of the latter that tends to reduce the rate at which nerve transmission continues. Depressants tend to enhance this effect. For example, members of the benzodiazepine family, a group of depressants, are able to bind to GABA receptor sites on postsynaptic neurons, increasing the efficiency with which those receptors work. Thus, with benzodiazepine molecules present in the brain, GABA neurotransmitters operate more efficiently and tend to significantly slow down brain activity, resulting in drowsiness and slower mental activity.

Another process by which depressants work takes advantage of the body’s natural system for dealing with pain. Neurons contain receptor cells especially adapted to a group of natural opiate neurotransmitters called endorphins, enkephalins, and dynorphin. These neurotransmitters are often called endogenous opiates or endogenous opioids because they are opium-like compounds that occur naturally within (“endo-”) the body. By contrast, the class of drugs generally known simply as “opiates” are more correctly called exogenous opiates (or exogenous opioids) because they occur naturally outside of (“exo-”) the body (as in plants). Endogenous opiates exert their effect on a receptor in the presynaptic neuron that controls the release of GABA from that neuron. When an opiate neurotransmitter docks at this receptor site, it reduces the release of GABA. Fewer GABA molecules flow through the synaptic gap and stimulate the postsynaptic neuron.

The importance of this change is that the amount of GABA in a neuron affects the amount of a second neurotransmitter, dopamine, also present in the neuron. Specifically, the more GABA, the less dopamine (recall that GABA is an inhibitory neurotransmitter). Thus, with less GABA present in the postsynaptic neuron, the greater the amount of dopamine. The significance of this change is that one of the primary effects of dopamine is the production of feelings of elation and well-being. The effect in an endogenous opiate on the presynaptic neuron, then, is to produce a sense of euphoria. Scientists now believe that this system, beginning with the release of endogenous opiates from the pituitary gland, has evolved as a way for the body to deal with pain.

The action of depressants (exogenous opiates) is simply to enhance this process. If one ingests heroin, for example, there are simply more opiate molecules in the bloodstream, some of which reach the brain. Once in the brain, the heroin molecules act in a virtually identical fashion to the way endogenous opiates work. A person who has taken heroin, then, feels the same sense of pleasure and rapture that comes from the action of endogenous opiates.

The previous discussion might be taken to mean that scientists have now essentially solved the puzzle as to how drugs affect the CNS. Such is not the case. In fact, the mechanism(s) by which some drugs affect mental and physical behavior is still largely a mystery. The case of LSD is a case in point. For some time, scientists have known that LSD has a chemical structure similar to that of the neurotransmitter serotonin. Serotonin itself is a bit of a puzzle for neuroscientists because there are so few cells that produce the chemical in the brain (only a few thousand), but its influence is widespread, with each serotonergic (serotonin-making) cell activating at least 500,000 other neurons (Frederickson 1998). The presence of LSD molecules in the brain almost certainly means that the substance will dock with serotonin receptor sites, either in the presynaptic or postsynaptic neuron, exerting either an agonistic or an antagonistic effect. Theories have been developed around all of four these possibilities, with a number of variations. Thus far, however, no one theory has been shown to explain the bizarre physical and mental effects that occur as the result of the ingestion of LSD. In fact, it was only in 2016 that researchers at Imperial College London obtained the first high-quality images of brains from people who were “high” on LSD, the first real clue to how the drug may affect the human CNS (Sample 2016).

The rest of this chapter is devoted to a review of some of the most common and most important substances involved in substance abuse problems. Each section deals, where appropriate, with a brief history of the use of the drug in the United States, current and historical patterns of drug consumption, and health effects associated with each substance. Other considerations, such as legal, political, social, moral, and other issues for each substance, are discussed in Chapter 2.

Tobacco is a product obtained from the leaves of plants belonging to the genus Nicotiana, the most widely cultivated of which is the species Nicotiana tabacum. When dried and cured, tobacco leaves are used to make a variety of products, including cigarettes, cigars, snuff, chewing tobacco, dipping tobacco, and snus, a moist form of the powder placed under the lip. Tobacco was first grown in the New World, where it was used almost exclusively for religious ceremonies and other special occasions, such as the signing of treaties and the celebration of important life events such as birth and marriages. Tobacco was used for these purposes largely because of its mild hallucinatory effects. Europeans who arrived in the New World in the fifteenth century and later were introduced to the product and began using it for purely recreational purposes. When they returned home, they brought with them samples of tobacco, which soon became widely popular for chewing, smoking, and for use as snuff.

Chemically, tobacco is a very complex substance, with at least 7,000 discrete components having been identified as constituents. The most important of these components is probably nicotine, a toxic stimulant that produces the “high” for which tobacco is used and which also produces the substance dependence that results from tobacco use. The health effects of tobacco use were largely unknown or ignored until the second half of the twentieth century. At that point, a number of scientific studies began to show that tobacco and tobacco smoke contain a number of ingredients with possible health effects, ranging from respiratory disorders, to diseases of the eyes and nose, to heart problems, to cancer. Table 1.2 lists some of the most important constituents of tobacco smoke, with the health risks they pose.

Although the health effects of tobacco use were ignored for most of its history, such is no longer the case. Public health agencies, private groups, and nonprofit organizations now work diligently to advertise the harmful effects of tobacco products on the human body. In its most recent announcements about the health effects of smoking, the Office of Smoking and Health of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) pointed out that tobacco use is responsible for an estimated 480,000 deaths in the United States every year, about one out of every five deaths in the nation. That total is greater than the total number of deaths from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), illegal drug use, alcohol use, motor vehicle injuries, and firearms-related incidents combined (Health Effects of Cigarette Smoking 2016). The CDC report went on to note that tobacco use is responsible for cancer of a number of organs, including the bladder, blood (leukemia), oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, esophagus, cervix, kidney, lung, pancreas, and stomach. In fact, tobacco use is now implicated in about 90 percent of all cases of lung cancer in men and 80 percent of all cases of lung cancer in women in the United States. In addition, many diseases of the respiratory system are caused by the use of tobacco products, with an estimated 90 percent of all cases of chronic obstructive lung diseases based on the use of tobacco (Health Effects of Cigarette Smoking 2016).

In recent years, health authorities have become increasingly concerned about the effects of tobacco use—especially smoking—even among those individuals who do not use tobacco. Research has shown that the smoke emitted by cigarette use can affect individuals in close proximity to a smoker, and even, in some cases, those who are at some distance from a smoker. Evidence now suggests that approximately 41,000 deaths in the United States annually can be attributed to secondhand smoke, of which about 7,330 are caused by lung cancer and 33,950 by heart disease (Health Effects of Secondhand Smoke 2016). Secondhand smoke, also referred to as environmental tobacco smoke, involuntary smoke, or passive smoke, is a special problem for children, partly because their immune systems may not be fully developed, and partly because they may be less able to remove themselves from locations in which they are exposed to smokers (as when their parents smoke). According to some estimates, secondhand smoke may be responsible for as many as 150,000 to 300,000 cases of lower respiratory tract infections among children in the United States each year, and an estimated 202,000 children with asthma may have their conditions aggravated by exposure to secondhand smoke (Health Effects of Secondhand Smoke 2016).

The considerable health risks posed by tobacco use have led to increased regulation of the product and more aggressive campaigns to discourage smoking and other tobacco use in the United States and other parts of the world, a topic discussed in more detail in Chapter 2. The results of these efforts have begun to bear fruit in the United States, where the percentage of smokers has continued to drop over the past 50 years from a maximum of 41.9 percent of the general population (51.2% of men and 33.7% of women) in 1965 to an estimated 16.8 percent of the general population in 2012 (18.8% of men and 14.8% of women) (Health, United States 2013, Table 56, page 192; and Current Cigarette Smoking among Adults in the United States 2016). The only group for which this trend did not hold was high school students, among whom the proportion of smokers rose from 27.5 percent in 1991 (the first year for which data were available) to 36.4 percent in 1997, before falling back to a recent low of 15.7 percent in 2013, in line with patterns for older Americans (Trends in Current Cigarette Smoking among High School Students and Adults, United States, 1965–2014, 2016).

A new factor was introduced into the discussion over tobacco smoking in the early twenty-first century. In 2003, a Chinese pharmacist named Hon Lik invented a new way of smoking tobacco that consists of a metallic tube consisting of four basic parts: an inhaler, which contains a replaceable cartridge that holds a liquid consisting of nicotine, water, and other liquids; an atomizing chamber, in which the liquid is converted to a vapor; a battery, used to bring about the vaporization process; and an LED light to replicate the burning tip of a traditional cigarette. (For a diagram of an e-cigarette, see http://www.e-cig-bargains.com/HowItWorks.jsp.) This type of electronic cigarette, e-cigarette, or vaporizer allows a person to enjoy the experiencing of ingesting nicotine, as with cigarette smoking, but without having to inhale the numerous other unhealthy tobacco components.

E-cigarettes became very popular very quickly in the United States and other parts of the world. Studies found that by 2014, 12.6 percent of all adults in the United States had tried an e-cigarette at least once in their life, with 14.2 percent of all men and 11.2 percent of all women falling into this category. The product was especially popular with younger Americans. In the 2014 survey, 21.6 percent of all individuals between the ages of 18 and 26 had tried an e-cigarette at least once in their life, with 5.1 percent of that group reporting that they now smoke e-cigarettes on a regular basis then. The comparable numbers for adults age 25 to 44 was 4.7 percent; those 45 to 64, 3.5 percent; and adults over the age of 65, 1.4 percent (Schoenborn and Gindi 2015).

One of the most interesting aspects of the e-cigarette phenomenon is that many people had come to believe that e-cigarettes are safer than traditional cigarettes. This point of view is reflected in the fact that 9.7 percent of individuals questioned in this survey who had never tried a tobacco cigarette had decided to try an electronic cigarette (Schoenborn and Gindi 2015). In fact, the safety of e-cigarettes has not yet been adequately determined. Some evidence suggests that the devices deliver some of the same risky chemicals present in traditional tobacco smoke, although the total amount of harmful ingredients obtained from e-cigarettes is almost certainly substantially less than that obtained from traditional tobacco cigarettes (E-cigarettes and Lung Health 2016).

The production and use of alcoholic beverages dates to the earliest periods of human civilization. The first evidence of jugs designed to hold alcoholic beverages dates to about 10,000 BCE, while the world’s first winery was discovered in modern-day Armenia, dating to about 4000 BCE (Patrick 1952, 12–13; Owen 2011). The production of alcoholic beverages is generally thought to be one of the first chemical processes discovered by humans, at least partly because the fermentation of fruit and vegetable matter, a process that results in the production of alcohol, occurs naturally and commonly. It is not difficult to imagine early humans discovering that the taste and effects of fermented plant products were pleasant enough to prompt them to find ways of making such beverages artificially.

Today, alcoholic beverages of one kind or another are a part of every human culture of which we know. In some cases, they are used for religious or ceremonial purposes, but most commonly, they are enjoyed solely for recreational purposes. In the United States, the annual consumption of alcohol per person has tended to remain at 2.0–2.5 gallons for more than 150 years. In 1850, for example, the average consumption for all alcoholic beverages was 2.10 gallons, the largest proportion of which consisted of hard liquor, such as gin and whiskey (also referred to as spirits; 1.88 gal), with much smaller amounts of beer (0.14 gal) and wine (0.08 gal). In 2013, average consumption was 2.34 gallons annually, although the proportions of beverages had changed, with consumption of beer at 1.12 gallons, wine at 0.42 gallons, and hard liquor at 0.80 gal). Except for a number of years that include World War II and the years following Prohibition, when alcoholic beverage consumption fell significantly, Americans’ consumption of beer, wine, and hard liquor has remained remarkably constant (Apparent per Capita Ethanol Consumption, United States, 1850–2013 2016).

Alcohol consumption differs widely among individuals and has been classified in a variety of ways by researchers and specialists. For example, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism defines four levels of drinking:

(Note that differing standards for men and women are not an act of sexism, but a reflection of differences in the way the two sexes metabolize alcohol [Drinking Levels Defined 2016]).

Over the last decade or so, binge drinking has been of special concern among specialists in alcohol abuse and alcoholism. Newspapers and the Internet often carry stories about high school or college students who “go on a binge” that ends badly for the drinker and/or his or her companions. For example, a Stanford University student and star swimmer was convicted in June 2016 for raping a young woman, at least partly because he was under the influence of binge drinking (Xu 2016).

In fact, binge drinking affects all levels of American society. According to the most recent data available, 60.9 million people reported having engaged in binge drinking in the 30 days preceding the survey, accounting for about one-quarter of Americans over the age of 11. The age group with the highest percentage of binge drinkers (37.7% of the total population in that age group) was those between the ages of 18 and 25, or about 13.2 million young adults. By comparison, the rate of binge drinkers was lower among those over the age of 25 (22.5%) and those in the age group 12 to 17 (6.1%) (Hedden et al. 2015, Figure 26, page 20). Interestingly enough, these numbers for all age groups have remained relatively constant over at least the past decade during which records have been kept.

Whatever the specific numbers, the finding that tens of millions of Americans acknowledge to binge drinking on a regular basis is quite significant. And that fact is associated with a range of personal and social issues that can occur as a result of binge drinking. Studies have shown, for example, that binge drinkers are 14 times as likely as non-binge drinkers to report driving in an impaired state. The condition has now also been associated with a range of physical and mental problems such as unintentional injuries of all kinds; intentional injuries, such as domestic violence and sexual assault; transmission of sexual diseases; alcohol poisoning; unintended pregnancies; high blood pressure and other cardiac disorders; liver disease; neurological damage; and sexual dysfunction (Binge Drinking 2015).

Binge drinking is by no means the only form of alcohol abuse about which there is concern. Alcohol consumption at levels lower than those seen in binge drinking has also been implicated in a number of life-threatening diseases and conditions. Some of the medical and psychiatric problems that are associated with alcohol use include liver disease, pancreatitis, cardiovascular disease, malignant neoplasms, depression, dysthymia, mania, hypomania, panic disorder, phobias, generalized anxiety disorder, personality disorders, schizophrenia, suicide, neurologic deficits, brain damage, hypertension, coronary heart disease, ischemic stroke, and cancers of the esophagus, respiratory system, digestive system, liver, breast and ovaries (Cargiulo 2007, S5). Overall, alcohol consumption is the fourth-leading cause of preventable deaths in the United States, accounting for about 88,000 deaths (62,000 men and 26,000 women) each year (Alcohol Facts and Statistics 2016).

The news about alcohol consumption is not, however, entirely negative. Some researchers have found, for example, that moderate consumption of alcohol may have some health benefits, such as reducing the risk of coronary disease, dementia, and diabetes (Alcohol Facts and Statistics 2016). This evidence appears to be strong enough that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Agriculture included a comment in their 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans that “moderate alcohol intake can be a component of a healthy dietary pattern” (Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee 2015, 4; see also Table D2.3, page 43). Given the very serious health problems associated with alcohol consumption, however, most statements like this one are followed by a warning that consumption of alcohol should be restricted to adults, that excessive consumption can pose a serious risk to human health, and that, for some people, even moderate amounts of alcohol can be harmful.

As indicated earlier in this chapter, marijuana and related substances (such as hashish) have been used in some parts of the world for many centuries. The use of the drug in the United States, however, appears to have been relatively limited until the 1960s. Prior to that time, marijuana was largely the drug of choice of certain small, specialized groups, such as jazz musicians (Harrison, Backenheimer, and Inciardi 1995). The first public opinion polls in which Americans were asked about marijuana use apparently date to the late 1960s, when use rate was recorded as being very low. The first such poll, for example, was conducted by Gallup in 1967. The poll found that about 5 percent of Americans said that they had used marijuana at once in their lifetime. Usage was significantly higher among college students, 12 percent of whom reported having smoked marijuana in a similar poll conducted two years later. Those results began to change rapidly, however, possibly as a reflection of more general cultural changes associated with the Vietnam War and other protests occurring during the late 1960s and early 1970s. For example, a Gallup Poll in 1970 found that 43 percent of all college students queried said that they had tried marijuana at least once in their lives, with 28 percent saying that they had used it in the drug in the preceding year (Harrison, Backenheimer, and Inciardi 1995).

Gallup continued to track Americans’ use of marijuana for the next four decades; it is the best source of those data prior to the late twentieth century, when the U.S. government also began keeping such records. After its earliest survey on the topic in 1969, Gallup found in 1972 that the fraction of Americans who had admitted to trying marijuana at least once had risen seven points to 11 percent. That trend continued in succeeding polls, reaching 12 percent in 1973, 24 percent in 1977, 33 percent in 1985, 38 percent in 2013, and 44 percent in July 2015 (Illegal Drugs 2016).

Almost certainly the best information about the use of marijuana by high school students became available with the initiation in 1975 of the Monitoring the Future (MTF) study, conducted for the National Institute on Drug Abuse by the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan, a study that continues to the present day. MTF researchers have asked a sample of U.S. 12th grades annually about their use of and attitudes toward marijuana and a similar sample of 8th and 10th grades the same questions since 1991. Those studies indicate that the percentage of 12th graders who had used marijuana within the 30-day period preceding the study was 27.1 percent in 1975, before rising to its highest level ever in 1978, 37.1 percent. Marijuana use among 12th graders then dropped off over the next 15 years or so, reaching a low point of 11.9 percent in 1992 before beginning to rise once more. It reached another high of 23.7 percent in 1997 before falling once more, this time to around 20 percent, where it has remained ever since. In 2015, the rate of 30-day marijuana use among 12th graders was 21.3 percent. Data for 8th and 10th graders followed a similar trajectory from 1991 to 2015 (Johnston et al. 2014, Table 5–3, pages 227–228; Johnston et al. 2016, Table 7, page 72).

One of the most controversial issues in the field of substance abuse concerns the health effects of consuming marijuana. Even though literally thousands of studies on the topic have been conducted, experts still disagree as to the precise effects that result from consuming marijuana and the severity of these effects. In its own review of the research, the National Institute on Drug Abuse has listed the following acute and chronic effects of marijuana ingestion:

Research conducted for well over a century also suggests that ingestion of marijuana may also have some health benefits. Although a number of claims have been made for the use of marijuana in treating many medical conditions, strong scientific evidence is still somewhat more cautious. In one large review of studies on the medical benefits of marijuana, for example, researchers found what they called “moderate-quality evidence” for the use of marijuana to treat chronic pain and spasticity and “low-quality evidence” to support its use for the treatment of nausea and vomiting due to chemotherapy, weight gain in HIV infection, sleep disorders, and Tourette syndrome (Whiting et al. 2015, 2456). A significant number of experts in the field believe that marijuana has a much greater range of uses in treating medical problems, however, and, as of 2016, 25 states, the District of Columbia, and Guam have taken the step of legalizing the use of marijuana for medical purposes (Medical Use 2016; Welsh and Loria 2014).

Cocaine is obtained from various plants belonging to the genus Erythroxylum, most commonly the coca plant E. coca. Residents of the South American Andes Mountains have used the leaves of the coca plant for religious, recreational, and medical reasons for many hundreds (or thousands) of years. In Bolivia and Peru, for example, people chew coca leaves as a way of dealing with the lassitude that results from living in very thin air at altitudes of 3,000 meters or more. Once the plant was introduced to Europe by early Spanish conquerors, it became widely popular for medical applications and as a recreational drink. One preparation was a coca-infused wine, Vin Mariani, which apparently was a favorite of Pope Leo XIII (Malin 2016). Coca products were also imported to the United States, where they appeared in any number of preparations, ranging from toothache remedies to a popular soft drink to pills, liquids, and even an injectable solution from the drug firm of Parke-Davis (Cocaine 1885, 124–125; Parke-Davis & Co. Cocaine Injection Kit 2016).

By 1900, evidence of the health consequences of cocaine use had become widely known, and legal prohibitions on the drug’s use were being instituted. Illegal cocaine was still readily available, however, usually in the form of the salt cocaine hydrochloride, in the form of a white powder that users inhaled or dissolved in water and injected. Reports of serious damage to the nasal passages as a result of cocaine “snorting” appeared as early as 1910, although these studies appear not to have much effect on the use of the drug for recreational purposes (Coca Timeline 2016).

Until the 1970s, powder cocaine was the drug of choice among many substance abusers, especially among well-to-do individuals. Its cost was usually too high for low-or moderate-income persons, accounting for its common name “the champagne of drugs” (Gahlinger 2004, 242). In the mid-1970s, a new form of cocaine became available, so-called freebase cocaine. The name comes from the method by which the product is made: cocaine hydrochloride is treated with a base, such as sodium bicarbonate, which neutralizes the acidic cocaine hydrochloride, leaving behind free cocaine. The cocaine is extracted from the reaction mixture with ether, which is then allowed to evaporate, leaving behind pure cocaine crystals, which can then be smoked. (The one serious risk here is smoking crystals that still contain some ether, resulting in a fire when the product is lighted.) Freebase cocaine rapidly became very popular because it was generally purer than powder cocaine and, as a result of being smoked, reached the brain more rapidly.

About a decade after the discovery of freebasing, yet another form of cocaine was developed: crack cocaine. The process for making crack cocaine is essentially the same as that for making freebase cocaine. Powder cocaine is neutralized with sodium bicarbonate, sodium hydroxide, or another base and heated. When the excess water in the mixture has evaporated, pure cocaine and additional by-products remain in the form of a rocklike crystalline substance. The substance gets its name of “crack” from the sound it makes during the chemical reaction by which it is formed. Because it is much safer and cheaper to make than freebase cocaine, crack cocaine soon became very popular among low- and middle-income individuals, resulting in an epidemic that peaked between 1984 and 1990 in the United States.

The number of Americans over the age of 12 who have used cocaine “occasionally” or “chronically” was an estimated 6,000,000 and 3,984,000, respectively, in 1988, the first year in which such data were collected. Those numbers both decreased regularly over succeeding years until they reached an all-time low of 3,216,000 and 2,755,000 respectively in 1999. Since 2002, government agencies have been counting the percentage of cocaine (and other illicit drug) users, rather than raw numbers. Those data suggest that the percentage of 30-day cocaine users dropped only very slowly from 0.9 percent of the U.S. population in 2002 to 0.6 percent in 2013 (National Drug Control Strategy [2013], Table 7; Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings 2014, Figure 2.2; see also Drug Use Trends 2002).

Considerably more detailed information is available about cocaine use among young adults by means of the MTF study. According to the most recent version of that report, 1.9 percent of 12th graders used cocaine at least once in the 30 days preceding the survey. The number increased significantly in the following decade, reaching 6.7 percent in 1985. It then fell off rapidly until it reached 1.3 percent in 1992. Over the last 25 years, it remained close to 2 percent before dropping again to its lowest point in history, 1.1 percent in 2012 (Johnston et al. 2014, Table 5.3, pages 227–228).

Users of cocaine do so because of the heightened feelings of sensation they experience, which may be described as an increased sense of energy and alertness, a feeling of supremacy, an elevated mood, and a sensation of euphoria. These feelings may not be entirely positive, as they can be accompanied by more unpleasant reactions, such as a sense of anxiety or irritability or a sensation of paranoia. As with any drug, however, these short-term feelings are balanced by longer-term physiological and psychological effects such as an increase in heart rate that may lead to cardiovascular problems; irritation of the upper respiratory tract and lungs among those who inhale the drug; constriction of blood vessels in the brain, which may lead to seizures or stroke; disruption of the gastrointestinal system, which can result in perforation of the inner walls of the stomach and intestines; kidney damage that can be serious enough to lead to kidney failure; and impairment of sexual function among both men and women.

The terms opiate and opioid occur commonly in the literature of substance abuse. At one time, the two terms had slightly different meanings. Opiate was taken to refer to any compound that was derived from the opium plant, Papaver somniferum. The most common and best known of these products are probably morphine, heroin, and codeine. The term opioid was originally proposed to describe synthetic analogs of opium compounds, such as oxycodone (Oxycontin), hydrocodone (a component of Vicodin), meperidine (Demerol), hydromorphone (Dilaudid), and fentanyl citrate (Sublimaze). Today, experts in the field have chosen to use the term opioid for any analog of opium, natural, synthetic, or semisynthetic (Opiates/Opioids 2016).

Opioids are arguably the most problematic of all abused substances in use today. Throughout history, they have played a dual role of useful medical product and dangerous recreational drug. This pattern arises because of the way opioids act on the brain. They attach to opioid receptors in the CNS, reducing the perception of pain and producing drowsiness and a general sense of relaxation and apathy. Opioids are so successful in this regard that they tend to be the most popular drug for treating levels of pain for which aspirin, acetaminophen, and other pain-killers are ineffective. The problem arises when a person ingests opioids to achieve these same sensations—relaxation, a sense of ease, and euphoria—for non-medical purposes. The brain easily becomes dependent upon and addicted to the effects produced by opioids, leading to harmful and dangerous long-term psychological consequences (How Do Opioids Affect the Brain and Body? 2014; How Does the Opioid System Work? 2007).

Opioid abuse is a problem in the United States and other parts of the world today because the legitimate demand for their use for medical purposes has produced a flood of the products that then easily become available to individuals who use them for recreational, non-medical purposes. This pattern has led to the so-called prescription drug epidemic, in which legal, useful, effective substances are being diverted to individuals who have no medical problem, but often do become dependent upon or addicted to drugs such as oxycodone, hydromorphone, and fentanyl. According to the most recent data available, 4.3 million individuals 12 years of age and older in the United States in 2014 reported using one or more prescription drugs for non-medical purposes in the 30 days preceding the survey (Hedden et al. 2015, 1).

In some respects, the most difficult aspect of this problem involves finding a way of preventing prescription drug abuse. One obvious approach is simply to cut back on the quantity of opioids prescribed by health care professionals, thus reducing the amount of such drugs available to abusers. But that approach means that people who legitimately need opioids for the treatment of pain or other uses may find it more difficult to obtain the drugs they need. This complex problem is discussed in more detail in Chapter 2 of this book.

Amphetamine was first synthesized in 1887 by the Romanian chemist Lazăr Edeleanu while conducting research on ephedrine, one of the oldest psychoactive stimulants known to humans. Edeleanu’s discovery was largely ignored for four decades before British chemist Gordon Alles, working at the time at the University of California at Los Angeles, repeated Edeleanu’s work and decided to explore the effects of amphetamine on humans (using himself as a subject). Alles found that amphetamine worked as a stimulant, much as does ephedrine, but even more effectively. He decided to continue and expand his research, eventually synthesizing and studying the effects of two amphetamine analogs, 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) and MDMA. Alles soon realized the potential medical benefits of amphetamine and its analogs and sold the process for making the drugs to the pharmaceutical company of Smith, Kline, and French, who first marketed amphetamine for the control of high blood pressure and the symptoms of asthma under the commercial name of Benzedrine in 1932.

The potential use of the amphetamines for recreational use did not escape the attention of many individuals, and the drugs soon became widely popular for this purpose in the mid-twentieth century (Rasmussen 2008). Even national governments realized their potential benefits as stimulants during World War II, when the armed forces of both Allied and Axis nations distributed amphetamines in large quantities to improve the endurance and aggression of their troops (Borin 2003). One problem was that the end of the war did not mean a loss of interest in amphetamines by former members of the armed services, and amphetamine abuse became a major public health problem in the late 1940s and 1950s. Eventually, the U.S. government attempted to solve the problem by banning the over-the-counter sale of amphetamine products in 1953.

Although these efforts at controlling the production and use of amphetamines were moderately successful at first, they were only the beginning of a long war between users of the drugs and drug enforcement agencies, a history that will be told in more detail in Chapter 2 of this book. Suffice to say that the abuse of methamphetamine and its analogs still poses a serious problem of substance abuse in the United States and some other parts of the world. According to the most recent National Survey on Drug Abuse and Health, an estimated 569,000 Americans (about 0.2% of the general population) could be classified as regular users of methamphetamine in 2014, of whom about 45,000 (0.2% of the age group) were between the ages of 12 and 17; 86,000 (0.2%) were between the ages of 18 and 25; and 438,000 (0.2%) were over the age of 25 (Hedden et al. 2015, Figure 10 Table, and pages 9–10).

The immediate results of taking amphetamines result from stimulation of the CNS and include increased heart rate and blood pressure, a sense of euphoria, increased wakefulness and need for physical activity, increased respiration, and decreased appetite. An excessive dose of an amphetamine can lead to irregular heartbeat, respiratory problems, cardiovascular collapse, and death. Some long-term effects of amphetamine use are related to these short-term effects, as overstimulation of the body may result in more serious respiratory and cardiac problems. It may also result in the onset of psychotic episodes that may include anxiety, confusion, insomnia, mood disturbances, violent behavior, feelings of paranoia, visual and auditory hallucinations, and delusions.

Another category of substances that are being abused today includes medications that are legally sold without prescription, so-called over-the-counter, or OTC, drugs. A relatively small number of OTC drugs contain ingredients that can have psychoactive effects on an individual if taken in doses not recommended for their legal medical use. Probably the most commonly abused of these drugs are cough and cold medicines, which typically include the compound dextromethorphan (DXM) as an active ingredient. DXM is an ingredient in more than two dozen popular OTC medications including Alka-Seltzer Plus, Cheracol, Contac, Coricidin, Diabetic Tussin, Kids Eeze, Mucinex DM & Cough Products, Robitussin, Sine-Off, Sudafed, Triaminic, Tylenol Cough, Cold, & Flu Products, and a variety of Vicks products. Products containing DXM are also available on the street under names such as candy, drank, dex, robo, skittles, triple c, tussin, and velvet. The practice of using such products is also known commonly as robotripping.

According to the most recent data available, 2.0 percent of all eighth graders, 3.70 percent of all 10th graders, and 4.10 percent of all 12th graders in the United States reported using a cough medicine product for nonmedical purposes in the year preceding the study. At all three grade levels, these percentages represented significant decreases from data collected in 2011, 2012, and 2013 (Monitoring the Future Study: Trends in Prevalence of Various Drugs 2015).

DXM has an inhibitory effect on neuroreceptors in the brain. That is, it tends to bind to those receptors and interrupt the flow of normal neural messages through the brain. In this respect, DXM acts in the brain in much the same way as do hallucinogens. This process has the general effect of slowing down mental processes in such a way as to produce a sense that one is removed from his or her body, a dissociative effect. DXM abusers often say that they feel completely relaxed and at ease, with a sense that they are floating through the air, released from their bodies. It is these feelings of euphoria and escape for which abusers are searching when they take DXM products (Cough and Cold Medicine [DXM and Codeine Syrup] 2015).

But the nonmedical use of DXM may also have a number of other side effects that are not as pleasurable as those a user is hoping for. These side effects include nausea, numbness, slurred speech, dizziness, sweating, insomnia, and lethargy. At more advanced stages, a user may also experience more serious effects, such as delusions, hallucinations, hyperexcitability, and hypertension. With prolonged use, liver and brain damage may result, and physical dependence and addiction may occur.

Another OTC product that is sometimes misused or abused, especially by teenagers, is called bath salts. The term has only the most tenuous relationship with the legitimate commercial product that many people add to their bath water for the soothing and relaxing feeling it can produce. The “bath salts” described here contain one or more synthetic analogs of cathinone, an alkaloid found in the leaves of the Catha edulis (khat) plant. It has physiological effects on the brain similar to those produced by amphetamine and its analogs. The product is sold under a variety of names, of which “bath salts” is only one. It is also marketed as plant food, a jewelry cleaner, or cleaner for a cell phone screen. The package in which the product comes is usually labeled “Not for Human Consumption” to avoid having to deal with regulations for legitimate drugs (DrugFacts: Synthetic Cathinones [“Bath Salts”] 2012). When sold on the Internet, the product may carry trade names such as Bloom, Cloud Nine, Ivory Wave, Lunar Wave, Scarface, Vanilla Sky, or White Lightning.

Bath salt products are typically ingested in a variety of ways, including by inhalation, by injection, or orally. Individuals take bath salts because of the sense of euphoria they provide, along with feelings of greater sociability, increased sex drive, and higher energy levels. These feelings may be accompanied, however, by other side effects that are not as pleasant, such as shortness of breath, abdominal pain, abnormal vision, anxiety, confusion, fever, rash, drowsiness, confusion, and dizziness. More serious side effects include abnormal renal function and renal failure, paranoia, psychosis, abnormal liver function and liver failure, and cardiovascular disorders (Prosser and Nelson 2012, Table 4).

The use of psychoactive substances dates back to the earliest years of human civilization. Those materials have been used for a variety of purposes: religious and ceremonial, medical, and recreational. Because of the variety of uses to which tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, opium, and other products can be put, societies have almost always had mixed feelings about their use, encouraging the more positive applications and discouraging (sometimes strongly) their less desirable uses. That tradition continues today. In 2015, the federal government spent about $26 billion trying to prevent, control, monitor, and treat public and personal health problems and social issues arising out of substance abuse, with nearly the same amount ($25 billion) spent by states and local communities on the same problems. Chapter 2 provides an introduction to some of the most important problems and issues related to substance abuse and actions that have been and are being taken to prevent and treat related problems.

“Alcohol Facts and Statistics.” 2016. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/alcohol-facts-and-statistics. Accessed on June 18, 2016.

“Apparent per Capita Ethanol Consumption, United States, 1850–2013.” 2016. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/surveillance102/tab1_13.htm. Accessed on June 17, 2016.

Austin, Gregory A. 1978. Perspectives on the History of Psychoactive Substance Use. Research Issues 24, National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.32106001081378;view=1up;seq=6. Accessed on June 14, 2016.

Beeching, Jack. 1975. The Chinese Opium Wars. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

“Binge Drinking.” 2015. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/binge-drinking.htm. Accessed on June 18, 2016.

Booth, Martin. 2003. Cannabis: A History. New York: Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press.

Borin, Elliott. 2003. “The U.S. Military Needs Its Speed.” Wired. http://archive.wired.com/medtech/health/news/2003/02/57434. Accessed on June 20, 2016.

“The Brain.” 2011. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p5zFgT4aofA. Accessed on June 15, 2016.

“Cannabis: India 1500 BC.” Inity Weekly. http://inityweekly.com/mmj-india-1000-bc/. Accessed on June 14, 2016.

Cargiulo, Thomas. 2007. “Understanding the Health Impact of Alcohol Dependence.” American Journal of HealthSystem Pharmacy. 64(1): S5–S11.

“The Chemical Synapse.” 2012. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TevNJYyATAM. Accessed on June 17, 2016.

Childress, David Hatcher. 2000. A Hitchhiker’s Guide to Armageddon. Kempton, IL: Adventures Unlimited Press.

Chrastina, Paul. 2009. “Emperor of China Declares War on Drugs.” Opium. http://opioids.com/opium/opiumwar.html. Accessed on June 14, 2016.

Clarkson, Janet, and Thomas Gloning. 2005. “The Women’s Petition against Coffee (1674).” http://www.uni-giessen.de/gloning/tx/wom-pet.htm. Accessed on June 14, 2016.

“Coca Timeline.” 2016. The Vaults of Erowid. https://www.erowid.org/plants/coca/coca_timeline.php. Accessed on June 19, 2016.

“Cocaine.” 1885. St. Louis Medical and Surgical Journal. https://books.google.com/books?id=6xNYAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA124&lpg=PA124&dq=parke+davis+cocaine+injection+kit&source=bl&ots=8pQSXBYHPD&sig=Lg4FOC5I4xMyG5uTvkjPvuNM33Y&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwim37u9x7TNAhVM7mMKHTMtBns4ChDoAQgkMAI#v=onepage&q=parke%20davis%20cocaine%20injection%20kit&f=false. Accessed on June 19, 2016.

“Cough and Cold Medicine (DXM and Codeine Syrup).” 2015. NIDA for Teens. http://teens.drugabuse.gov/drug-facts/cough-and-cold-medicine-dxm-and-codeine-syrup. Accessed on June 20, 2016.