Chapter 3

Didactic Sources of Musical Learning in Early Modern England

Jessie Ann Owens, in her book Composers at Work: The Craft of Musical Composition 1450-1600, mentions that the subject of musical education is one that is badly in need of more investigation.1 Although a number of younger musicologists are working in the area of music education in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, examining such topics as musical institutions, didactic sources, and compositional practice, at the present time, there does not exist a comprehensive scholarly source on the subject. There have even been two symposia, both coincidentally held in 1987 in Europe, on various topics relating to music education in the medieval era and in the Renaissance. One of these was the opening round table of the 14th Congress of the International Musicological Society in Bologna. A veritable cornucopia of topics was addressed, ranging from music curriculum to treatises to what was being taught within and outside the university and also in the surrounding schools, in the dance halls, in private lessons, and with or without manuals or texts. The question asked by Craig Wright, the session chair, was whether the bulk of those treatises were actual texts of lectures given within the universities. The obvious follow-up to that would be a question about the innumerable other books of musical learning that appeared following the advent of printing, everything from children’s primers to manuals for amateurs on how to sing, compose, and play a variety of musical instruments. It is one matter to know whether and what materials were used in musical instruction and yet another to know what actually went on in music lessons. We also need to determine where the lessons took place: in the classroom, on a one-to-one basis, within or outside of a school or institution. Beyond that, we must attempt to discover what was actually learned. This essay will begin to shed light on some of these issues by examining a number of didactic sources that contributed to the musical education of men, women, and children in early modern England.

In the first part of the sixteenth century in several places in Europe, children received their early education in various types of schools. We know, for instance, that children at the so-called ‘free song schools’ in England in the early sixteenth century learned music as singing and playing upon instruments, along with reading, writing, and the ABC’s in Greek and Hebrew. We have few, if any, actual texts. In the so-called English grammar schools, musical studies were not a priority, as teachers believed that music should be taught to choristers for practical reasons, not for its intrinsic value, but to fulfil the need for accompaniment to the liturgy. In the choristers’ schools, where music was included with other subjects such as grammar and rhetoric, boys alone were mainly prepared to take part in music of the divine service. Many composers were recruited from the ranks of these trained vocalists and a number of them became teachers, but probably few of these professional musicians taught at the universities.2 One famous English composer/teacher was Thomas Morley.3 Charles Burney writing in 1789, almost two hundred years after the publication of Morley’s A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musick, states that the treatise was still the best in the English language.4 At a conference held in April of 1939, presided over by the well-known musicologist Francis W. Galpin, a question was asked as to the best book for the study of pricksong.5 The answer was of course, Morley’s A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musick.6 Thurston Dart writing in 1962 at Jesus College, Cambridge, said that the book ‘contained all the ingredients – in three parts of course – for a student who wished to become a musicologist, the rudiments of music, counterpoint and canon and how to improvise, and a tract on how to compose.’7 There remains a void in our understanding of the educational landscape that set the stage for the publication and subsequent popularity of Thomas Morley’s musical primer. We need to determine how and for whom this and other didactic texts, which may have served as source material, assisted in providing a means of musical instruction in the Elizabethan times. Along the way, I hope to create a picture of musical literacy and learning in early modern England.

The well-known dialogue between Hortensio and Bianca from Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew, was written in 1596, a year before Morley’s treatise was published. In it, Bianca describes one of the most famous didactic images of music in use from the Middle Ages through the seventeenth century, the so-called Guidonian hand.

Hortensio: Madam, before you touch the instrument,

To learn the order of my fingering,

I must begin with rudiments of art;

To teach you gamut in a briefer sort,

More pleasant, pithy, and effectual,

Than hath been taught by any of my trade;

And then it is in writing fairly drawn.

Bianca: Why, I am past my gamut long ago.

Hortensio: Yet read the gamut of Hortensia.

Bianca [Reads]: ‘Gamut I am, the ground of all accord

A re, to plead Hortensia’s passion

B mi, Bianca, take him for thy lord,

C fa ut, that loves with all affection

D sol re, one cliff [clef], two notes have I.

E la mi, shew pity, or I die.’

Call you this gamut? Tut, I like it not:

Old fashions please me best; I am not so nice,

To [change] true rules for [old] inventions.8

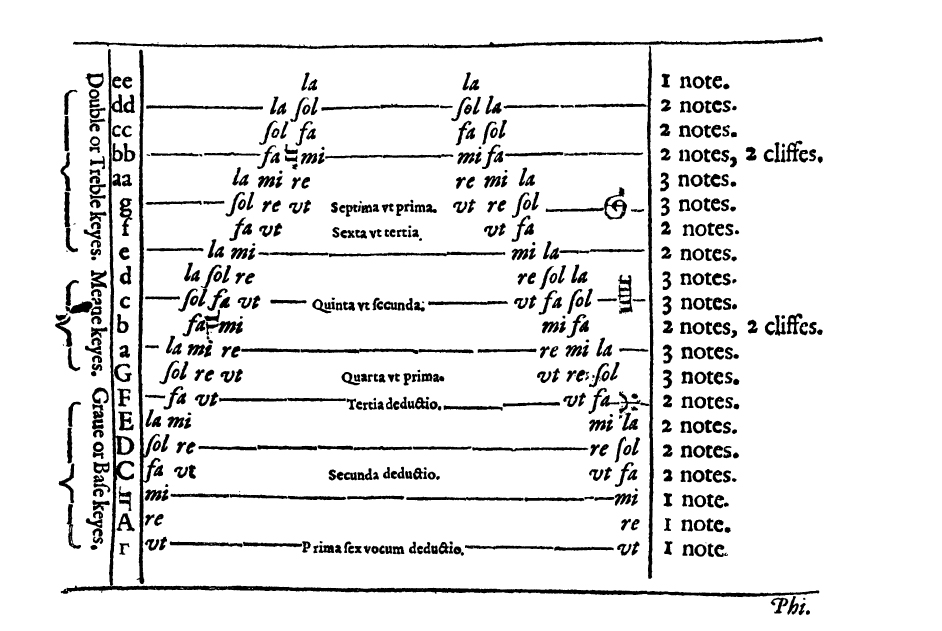

Shakespeare’s play is mimetic, meant to maximize human interest and give artistic pleasure to the audience. The nine-line jingle has only two ‘didactic’ lines, the first and the fifth. The others are interpolations for the sake of the play. The fifth line, ‘D sol re, one cliff, two notes have I,’ is an indication that Shakespeare undoubtedly knew his gamut (musical scale). Morley’s book is didactic, filled with theoretical, moral, and practical knowledge. Through his characters, a teacher and his two pupils, Morley proceeds in dialogue to set down the precepts of the gamut with carefully crafted rules and exercises accompanied by illustrations. One of these demonstrates how each cliff (clef) or alphabetic name is accompanied by a note or sol-fa name from the lowest gamma ut to the highest ee Ia (Plate 3.1).

Plate 3.1 Thomas Morley, A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practical/Musick (London, 1597), p. 2. British Library shelfmark 59. c. 16, by permission of the British Library.

The so-called Guidonian hand as a mnemonic for learning musical intervals (the distance between notes of the scale) via syllables known as solmization developed in the early Middle Ages.9 The Benedictine monk Guido of Arezzo (c. 991-after 1033) is credited with developing this system of teaching young choristers to read music and not have to rely on rote learning.10 The system was still in use in the late sixteenth century, although it was in the process of being supplanted by a newer and less complex methodology. Shakespeare could have learned the principles of the gamut and sight-singing from a domestic music teacher or from one or another music psalters, or from one of the little books that circulated in London prior to the publication of Morley’s treatise.

Morley and Shakespeare are products of the same rich educational system that was very likely set in place during the Carolingian era. Charlemagne sent the celebrated Yorkshire theologian, scholar, and teacher Alcuin to spread his love for learning and music throughout England and across the channel to continental Europe at the beginning of the ninth century. Changes in musical composition, the development of musical notation, and the need for systematic instruction in singing and playing forced some musical theorists to think differently about the art of music. It was not until the ninth century that a written tradition began to augment the aural/oral approach to the teaching and learning of music. Universities, founded in the twelfth century, promoted musical literacy and were among the organizations that saw a need for song schools. These schools were often affiliated with cathedrals, collegiate churches, chantries, and sometimes guilds and hospitals. In addition to the singing of liturgical music, an interest in instrumental and secular music developed in the late twelfth century. We find numerous references to practical music-making and learning in literature and vernacular poetry, works such as the Roman de Ia Rose, Boccaccio’s Decameron, and Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.11

Paradoxically, the growth in secular education led to both a decrease in emphasis on music within the curriculum of the grammar schools and in the musical training afforded young persons. Nor is an interest in practical music making revealed in the curriculum of the university. On the contrary, musical studies at the university were centred on their place within the mathematical quadrivium portion of the seven liberal arts, and were devoid of current considerations of practical matters. Music was considered one of the four ‘sciences’ along with arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy, while the trivium included the ‘arts’ of grammar, rhetoric, and dialectic. Emphasis was placed on Pythagorean relationships between music and the movement of the solar system, as well as on Boethius’ tripartite classification of music into three strata: musica mundana, the harmony of the universe, musica humana, the harmony of the human body and soul, and musica instrumentalis, the harmony produced by all sounding music.12

The requirements for the bachelor’s degree in music at Oxford between the years 1431 and 1565 reveal an increasing number of academic courses. By the late sixteenth century, in some English universities, students began to circulate petitions for the discontinuation of the music lectures (and a substitution of arithmetic) due to a lack of interest and poor attendance.13 The famous English composers of the time – Robert Fayrfax (1464-1521), Christopher Tye (c. 1505-c. 1573), and John Bull (c. 1562-1628) – did not lecture at the universities and this may have contributed to the lack of popularity in the courses. Ironically, Bull needed special dispensation to lecture in music at a new college in London so he could teach in the English language (as he knew little Latin).

Practising musicians, not university-trained pedagogues, probably trained these composers, ex cathedra. The texts in use, if any, were more likely to be the more practical treatises by Guido of Arezzo and others, rather than the academic texts in use within the university. The composers undoubtedly received their early education in music in the song schools of the private chapels of the gentry, where they were being trained as choristers.14 Training in these schools until the middle of the sixteenth century included lessons in grammar and chant, much of which stressed memory skills, followed by lessons in reading notes in pricksong.15 Music (singing, especially) was considered an aid to learning and was essential in teaching Latin, reading, and other subjects.16 The masters incorporated phrases consisting of proverbs, as well as classical, and sententious sayings into songs, to teach grammar and morality.17 Standard Latin grammar books, such as Robert Whittington’s (c. 1490-1558) and William Lily’s (c. 1468-1522) contained texts that were grave, didactic, and philosophical, but the sayings, especially set to music, made the memorization easier. Moral training based on Christian teaching was a significant part of children’s education. The young choristers also studied secular and instrumental music. Many of the songs they learned were part of choristers’ plays and are known to have been accompanied by instruments. A number of compositions in the Mulliner Book (British Library Add. MS 30513), compiled between 1558 and 1564, may have had connections to the pedagogical training of choristers. Jane Flynn suggests that the book’s contents and organization illustrate teaching methods used at cathedral and chapel song schools in sixteenth-century England.18

On the continent – particularly in Italy where the effects of humanism were felt much earlier than in England – treatises emphasized the more practical applications of musical knowledge. Pedagogy began to be directed at children, not as small adults, but as learners with different needs.19 François Rabelais set up an educational system that would prepare youths for practical endeavours. Rote learning and memorization was supplanted by thinking and problem solving through fun activities, such as singing, dancing, playing instruments, and card games. The Spanish humanist Juan Luis Vives (1492-1540), a pupil of Desiderius Erasmus at the trilingual College of Louvain, advocated theoretical and practical musical instruction for young men. Vives made several trips to England where he introduced his views at several grammar schools.20 Richard Mulcaster, the headmaster at the Merchant Taylors’ School in London, developed a curriculum in music that included singing and instruction in playing the lute and virginals.21

Although Henry VIII was a musician and a trained composer, his own son, Edward VI, was in large measure responsible for inhibiting the spread of musical learning. His Act for the Dissolution of the Chantries in 1547 did away with over two thousand song schools. At the choristers’ schools that managed to survive the dissolution – at Oxford, Cambridge, St. George’s Chapel and a number of other foundations – boys learned to sing in order to take part in the music of the divine service. In the years leading up to the Reformation choristers received their training in monastic schools in return for which they participated in the services. For a variety of reasons, some perhaps related to the influence of Erasmus (who himself may have had a bad experience at a choristers’ school), the third type of English elementary school, the secular urban grammar schools, did not emphasize musical studies.22 Another difficulty in the dissemination of new ideas and methods of teaching music in England stemmed from the expense of paper and the fact that it had to be imported from the continent, making printed books rare and costly. Many of their musical instruments also had to be imported, and often the tunes, dances, and treatises, as well as the musicians were foreign. Indeed, many of these imports were products of the German Lutheran educational system, which emphasised a systematic musical instruction for all children.

We have documentation from a variety of sources and can gain additional insights from literature, such as Shakespeare’s plays, as to how Morley’s music lessons might have been structured.23 Morley, himself trained as a chorister and organist, was a student of William Byrd (c. 1540-1623), although it is not known for how long and when.24 He received a Bachelor of Music degree from Oxford in 1588, was a Gentleman of Queen Elizabeth’s Chapel, was accomplished in Greek, Latin, and Italian and was said to have had a vast library. In addition, he was a printer, publisher, and politician. We also know that he was employed to teach the children of a wealthy and musically educated squire named Edward Paston (c. 1550-1630). Paston’s enormous library afforded Morley an opportunity to cull from all sorts of English and continental sources, one of which may have been British Library Lansdowne MS. 763, a collection of musical treatises. This manuscript includes some of the earliest writings in the vernacular from the early fifteenth century and it had been the property of the great English Renaissance composer Thomas Tallis (c. 1505-1585).25 Included is a tract referred to by the noted antiquarian Sir John Hawkins as the ‘John Wylde treatise’, a manual devoted to the general fundamentals of music and to the art of solmization.26 Another is by Leonel Power and was intended to instruct the singer to extemporize by visualizing a note in his part as against a note in the plainsong as written at a particular interval below it.27 Power stated that his treatise was ‘for hem that wil be syngers, or makers, or techers.’28 Rob Wegman has pointed out that English vernacular treatises contain rudimentary mental aids that do not presuppose musical literacy of the kind obtained in choristers’ schools. These manuscript handbooks or primers (a name aptly derived from the first part of the daily Office)29 were intended to enable singers to extemporize various parts contrapuntally to a written plainsong. In that sense they are practical manuals.30

Plate 3.2 Frontispiece from the tenor partbook, Whole Psalmes in Four Partes (London, 1563). British Library shelfmark K.l.e.2, reproduced by permission of the British Library.

Following the closing of the free song schools, more and more practical books, such as the Sternhold and Hopkins Psalter, which made its way to America in the seventeenth century, did much to educate the average English citizen.31 One of these, Whole Psalmes in Foure Partes, printed in London in 1563 by John Day, contains a frontispiece woodcut to the tenor partbook that depicts a gentleman, possibly the father of the house, giving a music lesson, pointing with his left hand to the extended thumb of his right. He is facing a woman and several young children. One of the children is holding a small book, perhaps the discantus partbook (Plate 3.2).32 Although there is no attempt made in the preface to explain the gamut, the notes of all the tunes in the psalter are printed with sol-fa names underneath. For some amateurs from the poorer classes, these psalters provided the only instruction in singing available at that time.

The attempt to make the learning of music more accessible to nonprofessionals was not new to Morley. A number of other treatises on musical instruction were published in the sixteenth century and used by English university students. Many of these were written in Latin and published on the continent, but some were translated into English.33 John Dowland’s translation of Ornithoparcus’ Micrologus (Leipzig, 1517) was published in London in 1609. The following paragraph from chapter three of this tract reveals that the frustrations over the complexities of Guido’s gamut and so-called hand were neither new nor were they exclusive to the English:

Seeing it is a fault to deliver that in many words which may be delivered in few (Gende Readers), leaving the hand, by which the wits of young beginners hindered, dulled, and distracted, leame you this fore-written scale by numbering it. For this being knowne, you shall most easily, and at first sight know the voyces, keyes and all the mutations.34

One of Morley’s aims and that of a number of other authors of published sixteenth-century textbooks of music, was to discover a less complicated system that would eventually replace the gamut, using sol-fa names for the rising major scale. While Morley still believed in the need for learning the gamut, he set out to enable the students to progress to an easier scheme – the fasola method. Morley undoubtedly knew the work of his immediate predecessor William Bathe. The first music primer printed in English, William Bathe’s A Briefe Introduction to the Skill of Song (1587) proposed scrapping the gamut altogether in the early stages of teaching. He referred to it as filled with ‘manifold, crabbed, confuse[d], and tedious rules’.35 He suggested a new method of sight-singing that used a fixed sequence of sol-fa names permanently related to the notes of the mixolydian scale (that beginning and ending on the note G). In this new system, the student had only to identify the position of ut on the staff in order to read a tune. Bathe, like his contemporary Francis Bacon, was influenced by a belief in empirical attitudes and boasted that he could, in the space of a month, teach a child of eight to sing difftcult ‘crabbed’ songs (referring to pieces with up to three sharps and three flats), to sing at sight, and to read in four clefs (C, F, G, and D).36 Bathe’s text heralded a new era in English texts that offered solutions to the beginner’s problems in learning music, a harbinger of changes to come in terms of the new approach to the teaching of sight-singing. This was followed by the anonymous Pathwaie to Musicke, published by William Barley in 1596, a compilation of various Latin and German treatises and more traditional in approach.37 The anonymous Pathwaie ends with what may be one of the most important tenets of teaching in the Renaissance: learning by imitating great teachers.

For we more regarding that whiche doth to the learner bring most facilitie and whiche are to be observed guid, have laid doune suche breiff rules as we thought most necessary to that effect, leaving the rest to the Imitatione of guid authors, as M. Tallis, M. Byrd, M. Tailor and others.38

Others followed Bathe, the anonymous Pathwaie, and Morley, such as Ravenscroft’s A Briefe Discourse on the True Art of Charact’ring the Degrees (London, 1614), Charles Butler’s The Principles of Musick (London, 1636), and John Playford’s A Breefe Introduction to the Skill of Musick (London, 1654).39 The books written by Christopher Simpson, Thomas Mace, and Italian and German theorists contain echoes of Morley’s methods and techniques.40

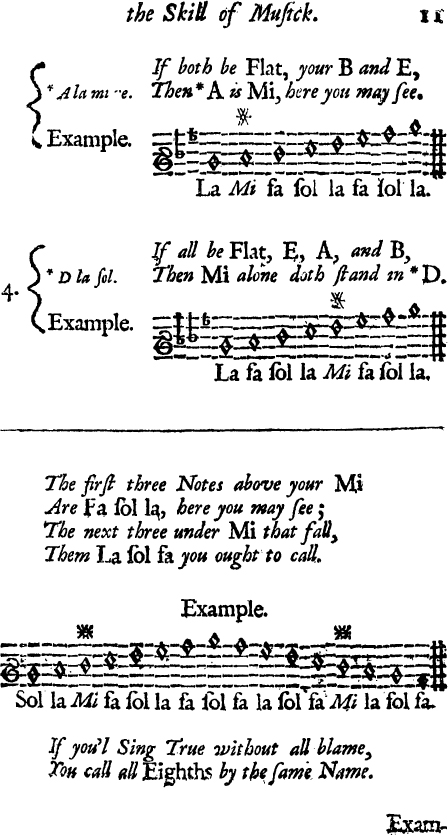

Some fifty years after Morley’s treatise, Playford included pieces like Morley’s madrigal ‘Now is the Month of Maying’. Playford wished to serve both the psalm-singing Puritan and the ordinary amateur. His treatise pointed more and more toward the rise of middle-class interest in domestic music-making, which by the eighteenth century, with the advent of equal temperament and advances in instrument-making, finally abandoned the hexachord system. Almost in homage to Shakespeare and Morley, Playford included the following mnemonic (see also Plate 3.3):

The first three Notes above your Mi

Are fa sol la here you may see

The next three under Mi that fall,

Them la sol fa you ought to call

If you’ll sing true without all blame

Plate 3.3 John Playford, A Breefe Introduction to the Skill of Musick (12th edn, London, 1694), p. 11. British Library shelfmark 1042.e.11(1), reproduced by permission of the British Library.

You call all Eights by the same name.41

The borrowing inherent in the compendious practices of didactic literature reflects the Renaissance practice known as imitatione.42 Morley and Shakespeare and other great imitators like Michelangelo and later J. S. Bach, took the best of what preceded them, used them as models and converted them into something perhaps even more sophisticated. Morley recorded the practices of others in a way that makes his text a perfect compendium for those wishing to learn music in his own and in succeeding generations. It was for many students of music in the early seventeenth century a more practical guide to the theory and science of music than any existing work.

The book has also been studied for its social significance as much as for its importance musically.43 A cultivated English gentleman, according to Morley, must be able to bear his part by sight in a madrigal, as well as being able to sustain a point of view in a debate on music.44 In his lesson on composition in five parts, Morley weaves some contemporary sayings into his lesson, such as

And though the lawyers say that it were better to suffer a hundred guilty persons escape than to punish one guiltless, yet ought a musician rather blot out twenty good points than to suffer one point pass in his compositions inartificially brought in.

A little later on, in response to Philomathes’ question about the excellence of his lesson, he answers ‘No, but except you change it all you cannot correct the fault which like unto an hereditary leprosy in a man’s body is incurable without the dissolution of the whole.’45 Philomathes asks his Master ‘What do you call going out of key?’, to which Morley (the Master) replies, ‘The leaving of that key wherein you did begin and ending in another.’ Philomathes asks again ‘What fault is in that?’ and receives the following response:

A great fault, for every key hath a peculiar air proper unto itself, to that if you go into another than that wherein you begun you change the air of the song, which is as much as to wrest a thing out of his nature, making the ass leap upon his master and the spaniel bear the load.46

The use of questions and answers like these were already in use in grammatical texts. Unquestionably the dialogues could be transplanted from the text to the classroom. The pairing of musical or grammatical concepts with sayings or proverbs served as memory aids that combined moral lessons with the subject at hand.47

The organization of Morley’s book has been compared to a musical composition, but it has also been described as mathematical, not surprisingly since Morley was trained in mathematics. Early in the book Morley indicated that the arithmeticians set down many kinds of proportions, but that he would only deal with three, those common in the works of Plato and Aristotle: geometrical, arithmetical, and harmonical.48 The first part teaches singing, the second, counterpoint, and the third, composition in two to six voices with a discussion of musical forms. Once the students learn to read music and are able to sing the chant in measured notes or in rhythm, they are ready to improvise in what Morley calls ‘ftguration’ and he describes three ways of doing this. The examples Morley uses seem – in terms of today’s standards – quite sophisticated for a so-called primer.

Morley’s source materials, as well as the educational system that trained and inspired him, are subjects of great interest. Morley relies heavily on his German, Italian, and even English predecessors. He argues for originality, criticizing the 1596 Pathwaie to Musicke as being a copy of works by two Germans.49 Among those authors he does credit are the German theorists, such as Nicolas Listenius (b. c. 1510), Johann Cochlaeus (1479-1552), and Heinrich Glarean (1488-1563), and the Italian Franchino Gaffurius (1451-1522). Many of these authors’ works were published in a number of editions and disseminated widely throughout Europe. Morley nonetheless fails to mention the debt he owes to the Italian Orazio Tigrini (c. 1535-91) and some of his information and tables – from sources like Gioseffo Zarlino (1517-90) and Alexander Agricola (1446-1506) – appear without citation. He shows his disregard for the German students who while studying at the Italian universities transmitted what he refers to as the ‘slightest kind of musick (if they deserve the name of musicke)’, vinate, to be sung during their drinking.50

In the late seventeenth century, Anthony Wood described Thomas Morley’s A Plaine and Easie Introduction as ‘admirably well skill’d in the Theoretic part of music.’51 Burney said Morley was a theorist first and then a practical musician. Morley’s book is not a school text, but one geared to the general public. Dedicated to Morley’s own teacher William Byrd, it was designed for private students, probably youthful, adolescent skilful beginners studying with a private master. Youths like Morley’s two students Polymathes and Philomathes, may have been from the rising middle class or from the aristocracy, boys on their way to becoming gentlemen. One part of this process involved studying music privately in an effort to take part in social activities, such as dances and parties.52 The book was not intended for the choirboys or university students. Morley aims the work at non-professionals, at gentlemen and gentlewomen who were amateur musicians, such as those portrayed by Shakespeare. The second edition, published in 1608, contains a list of errata in an appendix, mostly errors in spelling and punctuation; it generally presents an easier-to-read text.

It must have been a welcome text for those critics of private music teachers. The loss of the song schools in England did establish a need for private teachers and enabled many men and women to eke out a fairly good living giving music lessons.53 Prior to Morley’s text, the musical culture of the sixteenth century owed most to teachers who were employed as household musicians for well-to-do families. These practitioners provided instruction in secular and instrumental music.54 One of these, the minstrel teacher Thomas Rede, is known to have given lessons in lute, harp, and dance to George Cely, an English wool merchant.55 Another is James Renynger who was engaged by the abbot of Glastonbury in 1534 to ‘teach six children in prick song and descaunte, and two of them to play on the organ.’56 But some private instructors were better than others. The unevenness in teaching ability is described by Thomas Ravenscroft, in his preface to A Brief Discourse of 1614. Ravenscroft complained that by the early seventeenth century, teachers of music, ‘common kinde Practitioners [G truly ycleped Minstrells, though our City makes Musicians of themD]’, brought music down to its basest, most mechanical functions.57 He advocated a return to the medieval practice of learning measured music.

That editions of Morley’s text were used for over three hundred years cannot be denied. How it was used and by whom leads to other questions. One of the best ways to find answers is to examine some of the extant copies found in libraries in the English-speaking world for evidence of use.58 Recalling that ‘irony of book history’ mentioned in the introduction to this volume that didactic materials ‘survive today that were often little used or preserved in libraries or closets,’ it should not come as a surprise to find so few annotations in the surviving copies of Morley’s book.59 Of course, that finding can be explained in a number of ways. Books were valuable commodities in the early modern era. The very first printed book of music – Petrucci’s Odhecaton A (Venice, 1501) – was not yet one hundred years old. Bibliophiles might purchase Morley’s book with little intention of consulting it. Accomplished musicians probably could have used the book and been able to master its contents by committing the rules and tenets to memory. One of these was probably Samuel Pepys, who owned both a copy of Morley’s A Plaine and Easie Introduction (London, 1597: Pepys Library 2031) and also presumably John Playford’s A Breefe Introduction to the Skill of Musick.60 In an entry to his diary on 22 March 1667 Pepys stated that he read Playford’s book while walking to Woolwich from Greenwich one evening. He claimed to use the Morley when he was sick with a cold and had to retreat to his bed.61 While it is doubtful that one could write in a book while walking, it seemed possible that Pepys, while lying in his bed, might have annotated his copy of Morley.62 He did not, but fortunately, other Englishmen did.

A 1597 copy of Morley’s book in the Wren library at Trinity College and a 1608 copy held at Cambridge University Library have been examined by Anna Rees-Jones. Rees-Jones’ work, concerning keyboard manuscripts written by or for amateurs, led her to these sources for signs that linked one of them to a manuscript now located in the Bibliotheque Nationale (F-Pc MS Res 1186), probably copied by Robert Creighton (1593-1672), sometime Bishop of Bath and Wells. This manuscript contains transcriptions for keyboard of vocal pieces from Morley’s manual. Rees-Jones has identified the annotator of the Trinity copy of Morley as John Hackett (1592-1670), a close contemporary of Creighton who also retained a fellowship at Trinity before the Civil War, and became Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield after the Restoration. Jones was struck by the amount of printed music Creighton had access to in compiling his manuscript. Had he owned copies of everything he used, Creighton would certainly be considered an example of a non-professional consumer of written music. There is, of course, always the possibility though that printed copies of music were shared around, and that derivative manuscript copies reveal more evidence of borrowing rather than of ownership.63

Notably, the annotations in Hackett’s copy of the Morley are all related to the list of errata printed at the back of the 1597 edition. Every error acknowledged in the printed version is corrected by hand in the main sequence of the text. Although there is no evidence that Hackett himself attempted to discover errors, which would indeed be interesting from a musical literacy perspective, he did, at the very least, correct those that had been discovered at the proof-reading stage and acknowledged by the printer on the last sheets before the book was issued.64

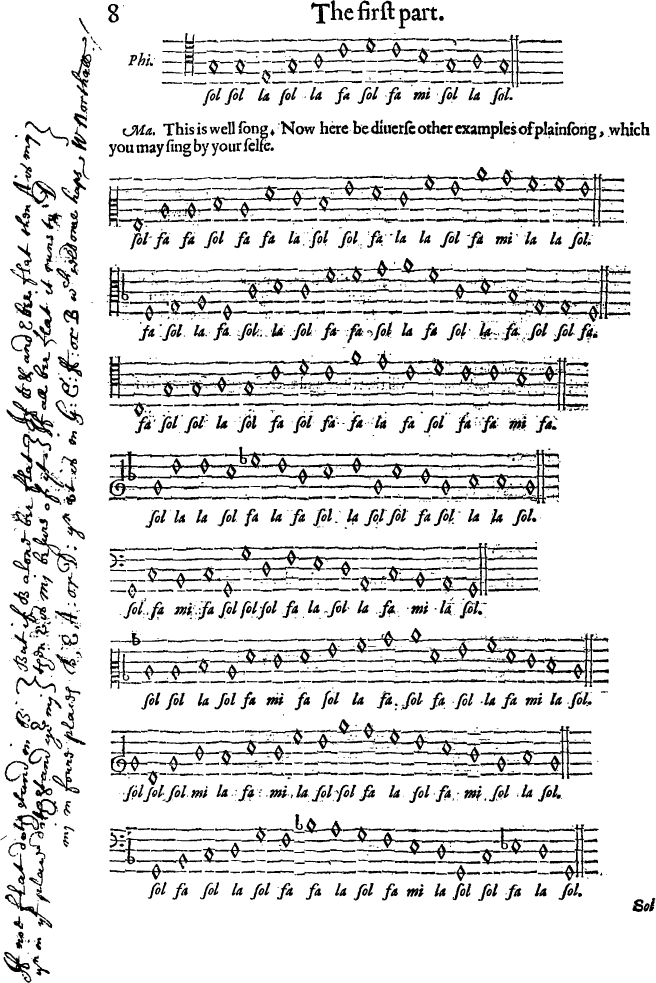

The Folger Shakespeare Library holds two copies of the 1597 edition and tow of the 1608 printing.65 Most of the annotations in these Morleys are ownership inscriptions of the same sort as those found by Rees-Joes, but one reveals more about the owner’s usage of the book. One of the two copies printed in 1597 (STC 18133 copy 1) belonged at one time to a ‘W. Northall’ whose name is written in the margin on page eight, alongside some rules he copied from previous pages and whose same hand made the changes called for on the errata page, systematically crossing each out and entering the corrections within the body of the text (Plate 3.4). Northall undoubtedly copied these rules as an aid to help him sing the song that appears on the page following Morley’s comments, ‘This is well song. Now here be diverse other examples of plainsong, which you may sing by your selfe.’ Here is some evidence that an attempt was made to execute a musical exercise. Of perhaps equal interest and significance is the observation that the reader made no further annotations.

Plate 3.4 Thomas Morley, A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musick (London, 1597), STC 18133, copy 1, p. 8. Reproduced by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

This author’s experience with a number of annotated German and Italian music textbooks, such as those mentioned above, as well as many others of this same period, reveal some important differences in patterns and stages of musical learning.66 Clearly, some of the German and Italian owners were amateurs or young beginners whose marginalia reflect difficulty with the material or waning interest after the first few pages, but others were perhaps students with a more academic background in music. In a few cases, the glosses reveal critical skills, not the least of which include the discovery of errors on the part of the authors, which point to ownership by professional musicians. At least one of these has been identified as a famous eighteenth-century music teacher.67 Morley’s text, with its scholarly material reserved for the ends of chapters, was not aimed at the serious music student, but at members of the English upper or rising middle classes. It appeared at a time when Sir Thomas Hoby’s English translation of Baldassare Castiglione’s The Courtier was enjoying widespread popularity.68 Morley’s book was specifically aimed at youths who wished to become gentlemen or ‘perfect courtiers’ and would have very possibly enlisted the help of a tutor. Although an annotated Morley that can be identified with a teacher has yet to be uncovered, it seems reasonable to assume that W. Northall is the student and not the tutor. He seemed to be making a valiant attempt at following Morley’s instructions, only to give up in vain after page eight, reinforcing the age-old notion that Morley’s book is neither quite so ‘plaine’ nor ‘easie’ nor ‘practicall’ as he might have hoped it to be.69

1 Jessie Ann Owens, Composers at Work: The Craft of Musical Composition 1450-1600 (New York, 1997), p. 12, n. 2 and 3. She cites a number of contributions to the field of music instruction and education including works by Nan Cooke Carpenter, Richard Rastall, Thomas D. Culley, Jeremy Yudkin, Bernarr Rainbow, K. W. Niemöller, Jos Smits van Waesberghe, Craig Wright, Kristine Forney, John Kmetz, John Butt, Jane Flynn, and Edith Weber. In 1998, a number of colleagues and I formed a consortium that meets annually to further the cause of historical musical pedagogy and literacy. In August 2002, we presented our most recent findings and the latest research in the field at the 17th Congress of the International Musicological Society in Louvain.

2 Foster Watson, The English Grammar Schools to 1660 (London, 1908, repr. edn, 1968), p. 205ff. As secular influence grew, music’s place in elementary education became less secure. With the growth of contrapuntal music, church leaders complained that music was preventing people from understanding ‘what was thus foreign, and to maken men wery and undisposed to studdie goddis lawe for aking of hedis’ (quoted by Watson on p. 206).

3 Philip Brett, ‘Thomas Morley’, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd edn, 29 vols, London, 2001), xvii, pp. 126-33. Morley was born in Norwich in 1557 and died in London in 1602.

4 Charles Burney, General History of Music (1776-1789), ed. F. Mercer (2 vols, London, 1935), ii, pp. 86-7.

5 Mensural notation, that is, measured music composed in two or more parts as opposed to plain chant.

6 David G. T. Harris, ‘Musical education in Tudor times (1485-1603)’, Proceedings of the Musical Association, 65 (1938), 109-39.

7 Ibid., p. 139. Dart admits that there were some omissions in Morley’s book, such as instruction on underlay, ficta, the sharp, and performance practice (whether to use words or instruments).

8 William Shakespeare, The Taming of the Shrew, III:1, lines 64-81, in The Complete Plays and Poems of William Shakespeare, eds William Allan Neilson and Charles Jarvis Hill (Cambridge, MA., 1942), pp. 148-78, p. 163.

9 Solmization is the general term for the use of syllables such as ut re mi, fa sol Ia. It derives from sol-mi.

10 Claude Palisca, ‘Guido of Arezzo’, New Grove Dictionary, x, pp. 522-6. Sigebertus Gemblacensis (writing c. 1105-10) credits Guido with assigning the letters or syllables of the hexachord to the joints of the fingers on the left hand in his treatise Chronica.

11 Leonard Ellinwood, ‘Ars Musica’, Speculum, 20 (1945), 290-9. See also Nicholas Orme, Education and Society in Medieval and Renaissance England (London, 1989), pp. 230-2.

12 Harris, ‘Musical education’. In addition to Boethius’ De institutione Musica (Venice, 1491/92) and Ornithoparcus’ more practical Musicae activae Micrvlogus (Leipzig 1517), two tracts by William Chell, a secular chaplain at Hereford Cathedral and a B.Mus. from Oxford (1524), were published, one entided Musicae practicae compendium and the other De proportionibus mathematicis. In 1586, John Case, trained at St. John’s College, Oxford, published the first of two treatises, The Praise of Music and two years later, the Apologia Musices tam vocalis quam instrumentalis.

15 A. Hamilton Thompson, Song Schools in the Middle Ages, Church Music Society Occasional Paper 14 (London, 1942), pp. 6-8.

17 Jane Flynn, ‘A reconsideration of the Mulliner Book (British Library, Add. MS 30513): music education in sixteenth-century England’, Ph.D. thesis, Duke University (1993), and Jane Flynn, ‘The education of choristers in England during the sixteenth century’, in English Choral Practice, 1400-1600, ed. John Morehan (Cambridge, 1995), pp. 180-99.

19 There are many books on the subject of how children learned and were taught, notably Nicholas Orme, Medieval Children (New Haven, 2001), especially chapters 4-8; on music per se, see pp. 190-1, 226-31, 260. See also Shulamith Shahar, Childhood in the Middle Ages (London, 1990), particularly pp. 187 ff for a description of the curriculum at the various categories of grammar and song schools. See also Danièle Alexandre-Bidon and Didier Lett, Children in the Middle Ages: Fifth-Fifteenth Centuries, transl. Jody Gladding (Notre Dame, 1999).

20 Erasmus’ treatise, De Ratione Studii (Strasbourg, 1511) formed the basis of fundamental philosophy of the English grammar schools: Eugene R. Kintgen, Reading in Tudor England (Pittsburgh, 1996), pp. 18-57.

21 Mulcaster had a spirit of national pride and urged the use of the vernacular as a sign of England’s emancipation from Catholic and papal dominance: see Kenneth Charlton, Education in Renaissance England (London, 1965), pp. 89-130.

23 Such as Anthony Wood, Athenæ Oxonienses … To which are added, the Fasti or Annals, of the said university (London, 1691), an important source for Burney and Sir John Hawkins in the eighteenth century.

25 Philip Brett, ‘Edward Paston’, New Grove Dictionary, xix, pp. 216-17. Paston was a Roman Catholic country gentleman who was known to have been proficient on the lute. His large collection of music manuscripts also contains some of the sole sources of compositions by William Byrd, as well as sacred and secular music written by continental composers.

27 Sanford Meech, ‘Three musical treatises in English from a fifteenth-century manuscript’, Speculum, 10 (1935), 235-69, p. 263.

28 Rob Wegman, ‘From maker to composer’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, 49 (1996), 409-79. Wegman suggests that such manuals – with musical notation for those who could not read mensural – catered to the growing workforce of nonclerical singers. Churches that lacked the funds to pay professionals were able to teach local citizens to sing discant on a voluntary basis. Methods of teaching singing in England must have worked well for there are many reports of continental musicians being impressed by English singing in the fifteenth century (p. 417).

30 In some German manuals of this same period, however, there is evidence of practical instruction in performance. Students were encouraged not only to strive for accuracy in pitch, but also to make an effort to sing with proper breathing and articulation. See Conrad von Zabern, ‘De modo bene cantand’ (transl.), in Readings in the History of Music in Performance, ed. Carol MacClintock (Bloomington, 1982), pp. 12-16. Von Zabern was a professor of music at Heidelberg around 1470.

31 Sternhold and Hopkins included a preface of theoretical instruction in many editions of their Whole Books of Psalms from 1548 onwards. By 1600 there were 74 editions and by 1700, another 235. By 1868, 601 editions of the Sternhold and Hopkins Psalter had been published: Sir John Stainer, ‘On the musical introduction found in certain metrical psalters’, in Proceedings of the Musical Association. 27th Session. 1900-1901 (London, 1901), pp. 1-50. See also Watson, English Grammar Schools, p. 207.

32 The image may also be intended to symbolize the natural harmony of the family, as well as the importance of psalms in a domestic setting.

33 Several other instruction books were English translations of continental sources, including some ‘how to’ books for playing the lute and cittern from tablature, such as John Alford’s translation of Adrien Le Roy’s 1557 treatise on lute playing, A Briefe and easye instrution [sic] to learne the tableture to conducte and dispose thy hande unto the Lute (London, 1586), and Anthony Holbome’s The Cittharne Schoole (London, 1597). See Nan Cooke Carpenter, Music in the Medieval and Renaissance Universities (Norman, 1958), p. 208; and Hiroyuki Minamino, ‘Sixteenth-century lute instruction books’, Ph.D. thesis, University of Chicago (1988), pp. 197-215.

34 John Dowland (transl.), Andreas Ornithoparcus his Micrologus (London, 1609; repr. edn, Amsterdam, 1969), Chapter 3, p. 9.

35 William Bathe, A Briefe Introduction to the Skill of Song (London, c. 1587; repr. edn, Kilkenny, 1982). An earlier version, Brief Introduction to the True Art of Musicke (London, 1584), written while he was still a student at Oxford, was never published.

36 Francis Bacon, Novum Organum, with other parts of the great instauration, transl. and ed. Peter Urbach and John Gibson (Chicago, 1994), Book I, para XC.

37 Pathwaie to Musicke, ed. Cecil Hill (Colorado Springs, 1979; 1st edn, London, 1596). The translation is by Melville, a Scotsman, and Hill retains the Scottish spelling and punctuation. Were it not for Melville’s copy, the treatise would be lost, the last known copy having belonged to Sir John Hawkins in 1778, when he gave it to the British Museum (where it had not been found in the 1970s, but may have been since).

39 Butler was the first English writer to replace ut and re in solmisation with sol and la in his treatise of 1636. There are a number of annotated copies of this treatise in the British Library. One of these is at shelfmark 52.d.30, and although I cannot be certain as to when the annotator lived, s/he is clearly familiar with music theory, as the marginalia reveal an understanding of the complexities of musical proportions.

40 See Christopher Simpson (d. 1669), The Principles of Practical Musick (London, 1665), and Thomas Mace (d. 1709?), Musick’s Monument; or, a Remembrancer of the Best Practical Musick (London, 1676). Among the continental authors who reflect on Morley are Michael Praetorius in his Syntagma musicum in quatuor tomos distributum (3 vols, Wittenberg, 1615/19) and Giovanni Battista Doni in his Compendio del Trattato de’ Generi de’ Modi della Musica (Rome, 1635); Susan Forscher Weiss, ‘The singing hand’, in Writing on Hands: Knowledge and Memory in Early Modern European Culture, ed. Claire Richter Sherman (Seattle, 2000), pp. 35-43.

42 Honey Meconi, ‘Does Imitatio exist?’, Journal of Musicology, 12 (1994), 152-78, is one of a number of articles on this subject in music. In 1532 the German theorist Johannes Frosch (c. 1470-after 1532) linked the term imitatione with composers in his Rerum musicarum opusculum rarum ac insigne (Strasbourg, 1532). Writers were encouraged to keep a notebook to write down choice excerpts from their reading and to use these in their own writing. Frosch recommends this to composers and provides examples.

45 Thomas Morley, A Plain and Easy Introduction to Practical Music, ed. R. Alec Harman (2nd edn, New York, 1963), p. 272.

49 Lucas Lossius (or Lotze: 1508-82), in his Erotemata musicae practicae (Nuremberg, 1563) and Fredericus Beurhusius (Friedrich Beurhaus: 1536-1609), in his Musicae erotematum (Dortmund, 1573) are the two German writers Morley refers to as having been the templates. Beurhusius uses Petrus Ramus (1515-72) as his model, as did his friend Johann Thomas Freig in Basel, who is also cited by Morley in his list of authors. Elizabeth Crownfield is currently writing a dissertation at New York University on the intellectual and cultural context of Morley’s Plaine and Easie Introduction, and includes a chapter on his interest in Ramus.

50 Morley (Harman edn), Plain and Early Introduction, p. 180. Drinking songs were a very popular genre in German-speaking lands, but many English children’s plays also contain a wide variety of these songs, some as rounds or catches, some as part-songs, and others as fiddlers’ tunes. The songs become part of a game where the one who missed a word or note would pay for the next round of drinks.

52 Carpenter, Music in the Universities, p. 345. One can speculate that Morley’s complaint about German students singing ‘vinate’ (see Carpenter, p. 37 and n. 48) serves as a kind of moralistic warning to his two young English gentlemen (and to all readers of his book).

55 Alison Hanam, ‘The musical studies of a fifteenth-century wool merchant’, Review of English Studies, 8 (1957), 270-4.

57 Thomas Ravenscroft, A Briefe Discourse on the True Use of Charact’ring the Degrees (London, 1614; facsimile edn, Amsterdam, 1971), sig. A.1v, See also Andrew Hughes, ‘Memory and the composition of late medieval office chant: antiphons’, in L ‘Enseignement de Ia musique au Moyen Àge et à la Renaissance (Asnieres-sur-Oise, 1987), pp. 53-73.

58 A search through the English Short Tide Catalogue yielded dozens of copies in libraries in the United States and the United Kingdom. According to Thurston Dart in his foreword to the Harman edition of Morley, a German translation was known to have been made by Caspar Trost in the early seventeenth century. Unfortunately, this never seems to have been published, a fact that is surprising in view of the popularity of Morley’s music and the numbers of German contrafacts. There may be English copies in European libraries and those would reveal further clues as to the widespread popularity and significance of Morley’s contribution to music learning.

59 See above, pp. 14-15. Several scholars are working with annotated music texts. One recent reference to an annotated copy of Morley is in Christle Collins-Judd, Reading Renaissance Music Theory: Hearing with the Eyes (Cambridge, 2000), p. 9, where she refers to some writing in the Library of Congress copy. These annotations she believes to be in a seventeenth-century hand and provide points of reference in reading the music. She suggests that the infrequency of these annotations may be an indication that certain skills were assumed; yet this is a suggestion that cannot be substantiated and one which calls for further documentation.

60 None of the various editions of Playford (1664, 1666, 1667) survives in the Pepys library. Although not every book once owned by Pepys is contained in the Library, the librarians tell me they have never heard of a Pepys copy of John Playford’s book. There is doubt whether he owned a copy, despite his friendship with Playford and his possession of a number of books published by Playford (see Pepys Diary, x, p. 337 and xi). The first edition of A Breefe Introduction is 1654, by which time Pepys was an accomplished musician and had left university, where he might have had the leisure to learn from the book. It is striking that in his accounts of his struggles with the principle of composition he makes no references to the digest of Morley contained in A Breefe Introduction.

62 I wish to thank Richard Luckett, the Pepys librarian and Aude Fitzsimons, the Assistant Librarian at Magdalene College, Cambridge for supplying me with this information. Pepys’s copy of Morley’s A Plaine and Easie Introduction contains no marginalia. This is, unusually, specifically noted in the Pepys Library Catalogue (vol. iv, Music, Maps and Calligraphy); they do not normally note the absence of marginalia, because they scarcely occur in Pepys’s books, and with two exceptions, are not by him. ‘W’hy they note ‘no marginalia’ in this instance is because of a persistent impression, which must derive from some published source, that these exist.

63 Anna Rees-Jones, personal correspondence, 30 April 2001. Jones is a graduate student at Cambridge working on music script and print, and musical instruction books in England in the seventeenth century. She has been working on two annotated copies of Morley, which are in the Wren Library, Trinity College. I wish to thank her for sharing her notes with me. See also Harold Love, Scribal Publication in Seventeenth-Century England (Oxford, 1993), pp. 23-46 for a description of how consort music first circulated and was sold in manuscript before finding its way into print.

64 Rees-Jones reported also on her examination of the 1608 Cambridge copy of Morley. She found no verbal annotations in this volume (signed by ‘R. Bulstrode’ [Sir Richard Bulstrode, 1610-1711]), though a few occasional pencil marks occur in the margin, presumably to highlight the text alongside. Most contemporaneous annotations were made in pen, so anything appearing in pencil is assumed to date to a later era.

65 My thanks to Rachel Doggett, Curator of Books and Exhibitions, and to Heather Wolfe, Curator of Manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library, for allowing me access to these works and other works, among them the Dowland lute manuscript (V.b. 280), described by John Ward in his article ‘The So-Called “Dowland Lute Book” in The Folger Shakespeare Library’, Journal of the Lute Society of America, 9 (1976) 5-29, and the printed volumes of Dowland’s ‘songes or ayres’, published between 1597 and 1603. Mr. Folger acquired the manuscript in 1926 at a Sotheby’s sale. For many years it was assumed that it belonged to Dowland and had remained in his family until that date in the twentieth century. John Ward argued that the annotations in the manuscript were probably not made by Dowland, but perhaps by a student, as they are not the kind of details for performance that would have been made by an accomplished musician. In fact, the name of the student, Anne Bayldon, can be seen on several pages within the manuscript. Some of the annotations in another of the copies of Morley’s A Plaine and Easie Introduction owned by the Folger appear to be the markings of a child (STC 18133 c. 2).

66 Among these are Flores musicae omnis cantus Gregoriani (Strasbourg, 1488) of Hugo von Reutlingen (c. 1285-c. 1360) the De musica (1490) of Adam von Fulda (1445-1505), Bonaventura da Brescia (fl. 1487-97) in his Breviloquium musicale (Brescia, 1497), Orazio Scaletta (c. 1550-1630) in Scala di musica molto necessaria per principianti (Venice, 1585), and Adam Gumpeltzhaimer (1559-1625) in his Compendium musicae latino-germanicum (Augsburg, 1591). See Susan Forscher Weiss, ‘Musical pedagogy in the German Renaissance’, in Cultures of Communication from Reformation to Enlightenment: Constructing Publics in the Easy Modern German Lands, ed. James Van Hom Melton (Aldershot and Burlington, 2002).

69 Heather Wolfe has examine the writing – looking closely at the letters e, h, r and superscript r, as well as -es at the end of a word – in STC 18133, copy 1, page 8 and is certain that it is a fairly standard secretarial hand of the seventeenth century. The identity of W. Northall is uncertain; there are a number of references in the online catalogue for the Public Record Office for William Northalls who would have lived in England in the sixteenth and seventeenth century, including one reference to a William Northall, plaintiff in a Star Chamber case under Henry VIII (STAC 2/17/155). It is possible that this Northall is an ancestor of the annotator of the Folger STC 18133, copy 1, but any attempt at matching the owner with one of these W. Northalls would be conjectural at this time.