Chapter 4

Seventeenth-Century Didactic Readers, Their Literature, and Ours

In their call for papers, the organizers of the 1998 conference ‘Expertise Constructed: Didactic Literature in the British Atlantic World, 1500-1800’ offered a list of works considered ‘didactic literature’: ‘from vade-mecums of bee-keeping to grammars, from “compleat” cookery courses to universal manuals on arithmetic.’ Although this list sketches a range of labours that might be described and prescribed by early modern didactic works, the list also offers examples where early modern and current assumptions about ‘didactic literature’ overlap; early modern authors, stationers, and readers and twenty-first-century scholars might all agree that these works are ‘didactic’. But because of historically-specific pressures on early modern texts and practices, the boundary was not always so clear between what we now call ‘didactic literature’ and what we call simply ‘literature’, between books for practical use and books for aesthetic appreciation. In mid-seventeenth-century England, the lasting influence of humanist pedagogy, the emerging conventions of literary authorship, and the anxiety about the material stability of print all make the distinction between ‘didactic literature’ and ‘literature’ more complex than a list of didactic works implies. Volumes that now seem most clearly literary were in fact immediately practical works for some seventeenth-century readers, and volumes that seem clearly didactic were in fact often literary exercises. Specifically, one seventeenth-century reader’s response to an influential single-author book of poetry suggests how a volume’s signs of aesthetic quality can enhance its practical utility, and collections of posies published in the mid-seventeenth century suggest how a volume’s signs of practical utility enhance its aesthetic quality. Together, these case studies begin to map the didactic potential of apparently literary books and the literary potential of apparently didactic books in the middle decades of the seventeenth century.

To start at the end rather than in the midst of the seventeenth century, in 1694, an aspiring professional worried that his product did not conform to prescribed standards. The aspiring professional was John Oldham, and his product was a literary collection entitled Poems and Translations, to which he prefixed the following explanation:

The Author of the following Pieces must be excused for their being hudled out so confusedly. They are Printed just as he finished them off, and some things there are which he design’d not ever to expose, but was fain to do it, to keep the Press at work, when it was once set a going. If it be their Fate to perish, and to the way of all mortal Rhimes, ‘tis no great matter in what method they have been plac’d, no more than whether Ode, Elegy, or Satyr have the honor of Wiping first. But if they, and what he has formerly made Publick, be so happy as to live, and come forth in an Edition all together; perhaps he may then think them worth the sorting in better Order. By that time belike he means to have ready a very Sparkish Dedication, if he can but get himself known to some Great Man, that will give a good parcel of Guinnies for being handsomly flatter’d. Then likewise the Reader (for his farther comfort) may expect to see him appear with all the pomp and Trapings of an Author; his Head in the Front very finely cut, together with the Year• of his Age, Commendatory Verses in abundance, and all the Hands of the Poets of Quorum to confirm his Book, and pass it for Authentick. This at present is content to come abroad naked, Undedicated, and Unprefac’d, without one kind Word to shelter it from Censure; and so let the Criticks take it amongst them.1

By drawing attention to where his book falls short of readers’ expectations, Oldham also draws attention to his understanding of those expectations. However worried Oldham may be about his book, he can at least be confident, writing as he does near the end of the seventeenth century, about what constitutes ‘all the pomp and Trapings of an author’. Oldham here ticks off a catalogue of bibliographic features that ‘pass [a book] for Authentick’, but from where did he learn these features? What prescriptions from what didactic works does he refer to? What grammar explains proper use of this set of signs?

While no specific didactic work seems to have taught Oldham how to construct an authoritative book, he could have learned as other authors and publishers of the seventeenth century seem to have learned, by professionally informed reading of other books that seem, if not necessarily stable or definitive models of literary authority, at least successful accommodations of emergent conventions. This professionally informed reading resembles the ‘reading for action’ that Lisa Jardine and Anthony Grafton have described in their article “‘Studied for action”: how Gabriel Harvey read his Livy’. Jardine and Grafton chronicle how Harvey read Livy over the course of his career as a text practically and immediately useful for furthering that career. Of his method of reading, they

argue that scholarly reading (the kind of reading we are concerned with here) was always goal-oriented – an active rather than a passive pursuit. It was conducted under conditions of strenuous attentiveness; it employed job-related equipment (both machinery and techniques) designed for the efficient absorption and processing of the matter read.2

Neither early modern editions of Livy nor seventeenth-century literary books seem to belong among the list of didactic works such as grammars and cookery books. But subjected to the process of reading that Jardine and Grafton describe – and which marginal evidence records in many extant early modern books – a broad range of texts seem to have had practical utility for their readers. In particular, Harvey’s reading Livy as an instruction book for his own professional activity and Oldham’s reading the apparatuses of contemporary literary books as instruction books for realizing his own literary ambitions exemplify how reading in early modern England complicates the category of ‘didactic literature’. The examples of Harvey and Oldham indicate that didactic force does not simply reside in texts severed from contemporary practices.

Of course, Oldham would seem to belong to a tiny minority of readers who might approach single-author books of poetry didactically. After all, those books provided clear models for his own volume. In his preface, however, Oldham imagines his suitably ‘Authentick’ book less as a realization of his own ambition than as a reassurance for his late seventeenth-century readers, who had come to expect the indicators of an authorized edition: the ‘pomp and Trapings’ of authorship, Oldham claims, will ‘comfort’ ‘the Reader’. If by 1694 readers had become comfortable with bibliographic signs of authority, those expectations were formed in part by single-author poetry collections published in the mid-seventeenth century, when the ‘Trapings’ of literary authorship in printed books were still being actively negotiated. Examples from the mid-seventeenth century show that not only would-be professional authors like Oldham read single-author collections of poetry didactically. Beyond a few careerist readers such as Oldham was a vast field of anonymous readers who seem to have had no ambition for public authorship as it was coming to be defmed, but who participated in the long-lasting humanist tradition of approaching published texts as practical guides for their own discourse. These readers could have consulted many published compendia of brief, pithy passages considered worthy of imitation, compendia such as this book published in a revised edition in 1630 with a decidedly unpithy title page: A helpe to memory and discourse with table-talke as musicke to an banquet of wine: being a compendium of witty and useful propositions, problems, and sentences, extracted from the larger volumes of physicians, philosophers, orators, and poets, distilled in their assiduous and learned obseroations.3 But in addition to such obviously didactic works, and as further evidence of the sometimes blurry boundary between ‘didactic literature’ and ‘literature’, readers at mid-century also looked to single-author collections of poetry for practical guidance. In fact, the more seemingly ‘literary’ a book, the better suited it may become as a resource for writing. The signs of authorial legitimacy in which many single-author books of the mid-seventeenth century are packaged – the engraved frontispieces, the letters from the printer, the commendatory poems – not only establish the status of the author and the aesthetic value of the texts enclosed, but also establish those texts as worthy resources. Gestures toward presenting a work as monumental, then, can paradoxically be gestures that open the text to use by didactic readers.

Because the array of conventions that establish the authority of early modern printed books can also make those books attractive resources for writing, some of the books discussed as crucial events in the intertwined histories of print and authorship seem also to have been useful works for contemporary readers. For example, the first printed collection of John Donne’s poems, Poems by J. D. (1633) is often cited as a foundational artifact for the establishment of print authorship. Arthur F. Marotti writes that

[t]he virtually simultaneous, posthwnous publication of John Donne’s Poems and George Herbert’s Temple in 1633 however, was a watershed event that changed the relationship of lyric poetry to the print medium, helping to normalize within print culture the publication of poetry collections by individual authors … After the publication of Donne’s and Herbert’s poems, and certainly after the appearance of the nwnerous single-author collections whose publication was partly authorized by the Donne and Herbert editions, lyric poems themselves were perceived less as occasional and ephemeral and more as valuable artifacts worth preserving in those monwnentalizing editions that were among the most prestigious products of print culture.4

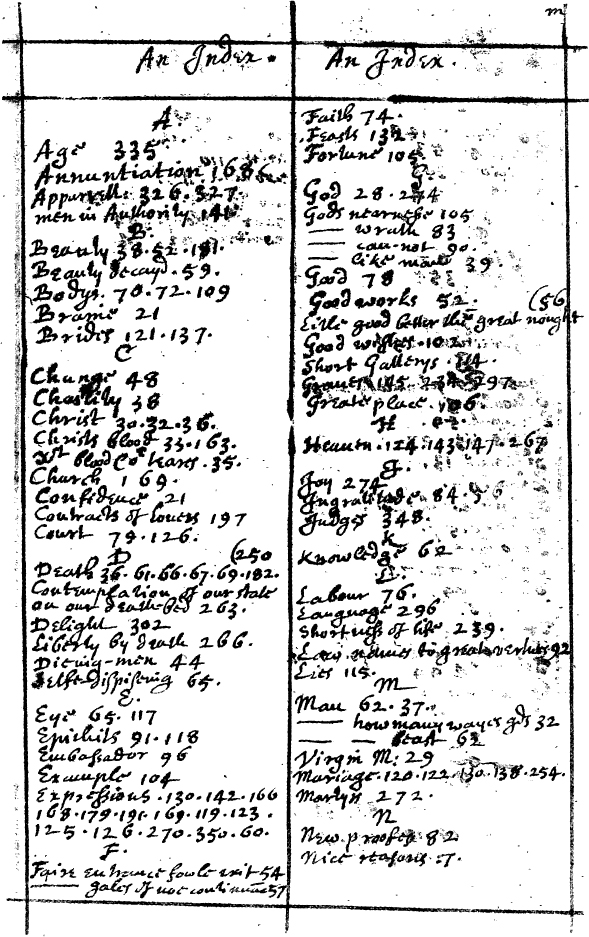

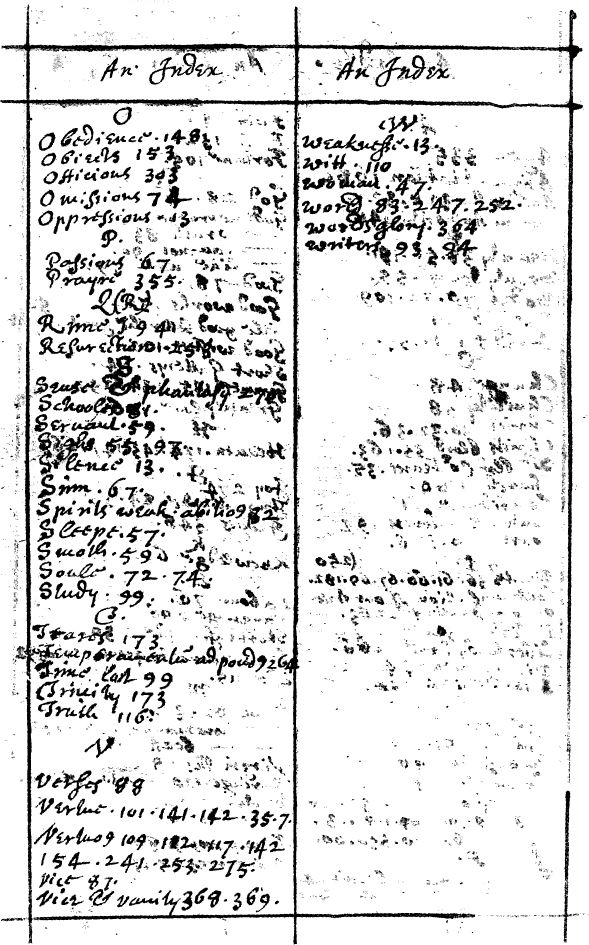

Although current scholarship valorizes Donne’s Poems as a ‘prestigious product’, the volume seems to have held particular didactic appeal for at least one seventeenth-century reader, and for that reader, Poems seems to have been not only a prestigious product but also useful raw material. At the end of one copy of the book (held at the Folger Shakespeare Library), a reader has written ‘An Index’, a collection of alphabetized topics, from ‘Age’ to ‘Writers’ (Plate 4.1).5 By doing so, the reader has attempted to impose an order on the collection that will allow the reader to find useful phrases quickly to incorporate into the reader’s own writing or speech. Consequently, the topics listed in ‘An Index’ seem determined at least as much by the reader’s own anticipated needs as by the topics of Donne’s verses. For instance, the reader has gathered far more page numbers for the heading ‘Expressions’ than for any other heading: ‘God’ gets two references, ‘Expressions’, fourteen. Because they seem partially shaped by the anticipated needs of this particular reader, the items listed in ‘An Index’ can be unabashedly idiosyncratic. Many readers might pick items like ‘Church’, ‘Bodys’, and ‘Woman’, but how many would single out for attention a heading on ‘Short Gallerys’? (The reference leads to a conceit in ‘A Letter to the Lady Carey and Mrs. Essex Riche’, where Donne attempts to make his brief episde seem larger by putting two mirrors of virtue in it, just as owners of ‘Short Gallerys’ make them seem larger using mirrors.) Such items emphasize that the compiler of ‘An Index’ may have thought of this list more as a personal and personalized resource than as a definitive reference tool for wide use – ‘An Index’ instead of ‘The Index’.

Donne’s poems are usually not included among the examples of ‘didactic literature’, but this particular copy of Poems by J. D. seems to have served as a writing reference for its owner. And by reading didactically, this owner has reinforced the claim to ownership, because as the marginalia in instructional works often demonstrate, didactic reading can be a powerfully appropriative process of making one copy of one book the individuated property of its reader-owner. This owner of this copy of Donne’s Poems seems much less concerned with how Donne might express his own subjectivity than with how these ‘Expressions’ might be taken from Donne’s book and used in some other personalized context. Who is speaking sometimes seems to matter less to this reader than what is said. As a result, some of the reader’s references under ‘Expressions’ point to exacdy the kind of witty figures that we might expect a reader to harvest for later writing. For example, ‘An Index’ sends us to page 119 for one expression, and on that page the reader has marked this passage from Donne’s ‘An Epithalamion, or Marriage Song on the Lady Elizabeth and Count Palatine being Married on St. Valentine’s Day’:

Up, up, fair bride, and call,

Thy stars, from out their several boxes, take

Thy rubies, pearls, and diamonds forth, and make

Thyself a constellation, of them all.6

This comparison between jewels and stars, and by extension, the comparison between a bejewelled bride and a constellation, is just the type of fragment that humanists might have encouraged their students to gather a century before Donne’s book was published. ‘An Index’, like many other and later compilations, indicates how long related practices survived among English readers.7

Plate 4.1 ‘An Index’, written on the final leaves of a copy of John Donne’s Poems by J. D. (1633), held at the Folger Shakespeare Library (STC 7042, copy 2). By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

At other times, though, the compiler of ‘An Index’ points to expressions that would not transfer easily to other contexts. The most surprising of these may be the reference to page 350, ‘A Hymn to God the Father’, where Donne puns on his name and perhaps on his wife’s name at the end of each stanza (e.g., ‘When thou hast done, thou hast not done,/ For, I have more’).8 Where the bride/constellation figure does not seem tighdy or specifically bound either to the author or to the addressee, these puns would seem highly individual and personal – only another writer named ‘Donne’ could use these puns as Donne himself has. Even what seems most individual in Donne’s book is marked for appropriation or imitation – maybe precisely because it does seem most individual and, to use Oldham’s word, ‘Authentick’.9 That the compiler is drawn to this passage in this book, just where Donne announces his proprietary authorship most explicidy, suggests that the compiler understands Poems by J. D. as a book that will help the compiler to become not simply a better writer, but a writer who is more like an author. In this particular copy of Donne’s Poems, established practices of humanist reading and emerging conventions of print authorship collide.

Any number of English books available in the 1630s could have supplied the compiler of ‘An Index’ with a list of ‘Expressions’, and some books, like the more explicidy didactic A help to memory and discourse, were developed primarily to provide such lists. But this reader, unlike humanist readers of the preceding century, seems to want more than a collection of free-floating, endlessly iterative ‘Expressions’. Rebecca Bushnell has shown that by the mid-sixteenth century humanists alternated between approaching books as collections of (re)usable fragments and approaching books as organic wholes. This transition, she writes, is captured in the differences between describing a book as a garden and describing a book as a body:

The book imagined as a body … especially the body constructed in its emergent ‘classical’ conception, was quite different from the ‘garden’ book. The visitor passed from one garden ‘room’ to another, all the while admiring and perhaps gathering the various and abundant plants. By analogy, the reader’s experience of the book was like that of the intelligent consumer who could appropriate the best parts from the larger arrangement. The body, however, was conceptualized as a unified structure from which no element could be removed without injuring the others.10

The writer of ‘An Index’ culls from Donne’s book as from a garden, but the same writer also carefully restores controversial lines omitted from Donne’s poems. The printer of the 1633 collection omits some controversial passages of Donne’s poetry, for instance, substituting dashes and blank space for Donne’s bitterly ironic lines in ‘Satyre 2’: ‘Bastardy abounds not in Kings titles, nor/Symony and Sodomy in Churchmens lives.’11 The same hand that wrote ‘An Index’ also wrote those lines into the blank spaces left by the printer, assuring that even if the bodies of kings and churchmen may be suspect, the body of this book (a trope often deployed in posthumous editions like Poems by J. D.) will be whole. To mix the sixteenth-century metaphors terribly (because indeed, the concepts were mixing in the mid-seventeenth century), for this reader, only a body can be a worthwhile garden. Only the complete body of an ‘Authentick’ book can teach the reader what earlier books could not: how to channel some of the nascent forms of authority into the reader’s own writing. The characteristics that make Poems by J. D. an important book in critical histories of print and authorship also make it a useful didactic work for this reader.

‘An Index’ marks the permeable boundary between ‘didactic literature’ and ‘literature’ in mid-seventeenth-century England, demonstrating how the characteristics that make a book authoritatively literary could also open the book to practical use. While authors, printers, and publishers were changing the status of literary authorship and hence were changing the signs by which aesthetically valuable writing might be recognized, some readers who aspired to write well turned for guidance to the ‘Authentick’ books that were redefining good writing; such literary books were uniquely positioned to serve as didactic literature. Consequently, by the time Oldham published his apologetic preface in 1694, readers so expected authenticity that they had themselves become, at least in Oldham’s imagination, powerful enforcers of literary authority. By reading didactically, they too had learned what an author ought to do.

The compiler of ‘An Index’ demonstrates how early modern reading practices trouble the neat separation of ‘didactic literature’ and ‘literature’. Some of the most popular poetic forms of mid-seventeenth-century England similarly show the difficulty of that separation. For instance, the posy, a short poem often associated with inscription in rings, on cutlery, and other surfaces, has often seemed too slight for serious literary study, even though many early modern volumes of poems include sections of posies.12 How should we view a collection of very short printed poems gathered in a group entitled ‘Posies’? As portable discourse to be engraved into rings and other goods, or as little poems to be appreciated in printed form rather than actually transcribed? As ‘didactic’ or as ‘literary’? These questions of appreciation and appropriation arise with special force in the 1640s and 1650s, when posies regularly appeared in printed books such as Cupids Posies, For Bracelets, Handkerchers, and Rings (1642); the significantly enlarged second edition of Loves Garland: or, Posies for Rings, Handkerchers, & Gloves: And such pretty Tokens that Loves send their Loves (1648); The Card of Courtship, or The Language of Love (1653); and finally, The Mysteries of Love and Eloquence; or, the Arts of Wooing and Complimenting (1658). If, as Joan Evans shows in her catalogue of English Posies and Pory Rings, posies proliferated in seventeenth-century England, their appearances in printed books were concentrated in the 1640s and 1650s.13

Of these four printed books, Loves Garland and Cupids Posies are collections exclusively of posies, and the other two at least purport to be how-to books, namely, how to succeed in love. These books claim to address readers across lines of class and gender. The title page of The Card of Courtship directs the volume ‘To the longing Virgins, amorous Batchelors, blithe Widows, kinde Wives, and flexible Husbands, of what Honour, Title, Calling, or Conversation soever within the Realm of Great Britain.’ The prefaces to The Mysteries of Love and Eloquence, written by Edward Phillips, attempt to be similarly inclusive. Although it is clear what the longing, amorous, blithe, kind, and flexible might do together, how, exactly, the books might help them is less clear, because these books package apparently literary texts in the framework of how-to manuals. For instance, The Card of Courtship begins with a series of ‘Complemental Dialogues’, presumably exemplary conversations to guide novices in love. But a number of these dialogues are in rhymed couplets, and all present dramatic situations that illustrate how some of the impulses impeded by closed theatres have been diverted into model dialogues. The first dialogue begins this way: ‘A Virgin licensed by her Father to make choice of whom she likes best for her husband, Imagine you hear one who affects her, courting her after this manner: with their names suppose to be AMANDUS, and JULIETTA.’14 Rather than directing virgins who have the freedom to choose their spouses, perhaps a tiny minority of the volume’s readership, the dialogue is forthright about engaging readers in an imaginary situation; even readers who are in the position of neither Amandus nor Julietta might enjoy access to this private conversation. The prefatory poem ‘To the Reader’ in The Card of Courtship accordingly extends the book’s appeal beyond the purely practical and promises that readers already happy in love will also enjoy the book:

Here read, how beauty to command,

Though rugged, like the Panthers skin;

Here thou maist leame to love and win.

Or if so happy’s thy condition,

Thou of thy love hast the fruition:

Here such pleasures thou mayst find,

So sweet, and of so various kind,

That rockt into a pleasing dream,

Thou’lt wish I’d had an ampler theam.15

As the appeal of this prefatory poem makes clear, instructional and literary material are not always separable in volumes of the period; a given complemental dialogue may be framed as providing practical assistance to a narrow audience and offer aesthetic pleasure to a broad audience. The stationer selling The Card of Courtship was, after all, Humphrey Moseley, whom Ann Baynes Coiro has justly called ‘the leading purveyor of high literary culture in the seventeenth century.’16 Customers of Moseley’s stall could have found the appeal of The Card of Courtship similar to the appeal of Moseley’s other, now more famous, literary volumes. Just as The Card of Courtship shared shelf space with elaborately prepared single-author volumes of poetry by Cartwright, Milton, Shirley, and Waller, the section of posies in The Card of Courtship is tucked between a section entitled ‘Odes’ and a section entitled ‘Songs and Sonnets.’ Because the posies themselves resemble those on extant early modern rings, this context suggests the blurring of ‘literary’ and ‘practical’ throughout the volume. Wedged between the ‘Odes’ and the ‘Songs and Sonnets’ are posies that would not be out of place carved into a lover’s token – from the perspective of later categorization, the practical, or at least the practicable, nestled within the literary.

The posies in Mysteries of Love and Eloquence appear in what seems to be a more obviously practical reference work. Mysteries of Love and Eloquence is a heterogeneous volume that includes such practical guides as a rhyming dictionary and a list of epithets under the title ‘A Garden of Tulips.’ But many of the book’s posies vary markedly from the posies in extant rings. Some are limited because they depend upon specific names: ‘My dearest Betty/Is good and pretty’; ‘I did then commit no folly,/ When I married my sweet Molly.’ Although such couplets might provide general examples of how one might play on the beloved’s name, they would be directly useful only to someone giving a token to Betty or Molly. Other posies in Mysteries of Love and Eloquence are bawdier than anything inscribed in extant rings surveyed by Joan Evans: ‘Dorothy this Ring is thine,/ And now thy bouncing body’s mine.’ When the posies present a female voice, that voice attests to the virility of a male partner: ‘My Henry is a rousing blade,/ I lay not long by him a maid.’ The posies in Mysteries of Love and Eloquence are thus a mixed lot, some feasible as posies for rings, and others posies only more generally, more consistent with contemporary jest-books than with contemporary jewellery.

Besides the posies in ostensibly instructional books such The Card of Courtship and Mysteries of Love and Eloquence, a few small octavos consist entirely of posies. One of the first of these books was published in 1642, and as its title demonstrates, it encompasses a variety of inscribable surfaces: Cupids Posies, For Bracelets, Handkerchers, and Rings. With Scaifes, Gloves, and other things. Where Mysteries of Love and Eloquence puts implausible posies in the context of an instructional book, Cupids Posies puts plausible posies in the context of a seemingly literary volume ‘with all the pomp and Trapings of an Author’. The title page states that the volume was ‘Written by Cupid’, and the volume parodically represents Cupid’s authority with some of the emerging signs of print authorship: a frontispiece portrait of Cupid, a dedicatory poem from Cupid to Venus, a prefatory poem to readers, and a concluding poem in which Cupid states that he will publish more verses if these find favour. But even given these rudimentary displays of literary authorship, the volume emphasizes the utility of its posies. The prefatory poem makes clear that, properly inscribed on love tokens, the ensuing posies can help lovers:

These same Posies which I send,

And to Lovers do commend;

Which if they be writ, within

The little circle of a Ring,

Or be sent unto your Loves

With fine Handkerchers [or] Gloves:

I do know that like my Dart,

They have power to wound the heart:

For instead of Flowers and Roses,

Here are words bound up in Posies.17

The reference to flowers at the end of this poem implies that posies of words can be more effective than posies of roses, and readers are invited to select from among Cupid’s selection as they might gather from a garden. A number of Cupids Posies also appear on rings catalogued by Joan Evans – for example, ‘Loues delight is to unite.’18 Regardless of the exact relation between poems in the volume and on the rings, regardless whether book or ring or some other text(s) came first, the reappearance of these posies in such seemingly different material settings hints at the expansive range of inscribable surfaces in early modern England, a range analysed more fully in Juliet Fleming’s study of sixteenth-century graffiti.19 Of course, most of the posies in Cupids Posies exist now only as printed texts, and despite the book’s insisting upon the utility of these posies, some seem to exist primarily as texts that evoke a speciflc situation. Consider this posy, with a telling title: ‘A Lover coming into a Maidens chamber in her absence did write this posie on her looking glass’:

In this same Looking-glass,

my watry eyes I see:

But I do wish that thou could shew

her cheerful eyes to me:

Yet why do I accuse thee here,

tis not thy fault for thou art clear.20

The paratextual function of the title is all-important; if the title did not place the posy within a social and material setting, it would make little sense. Although Cupids Posies promises – and delivers – posies that can be made suitable engravings for love tokens, this posy seems more concerned to narrate a past event, not so much encouraging readers to trespass and vandalize, as encouraging them to imagine a poem on a printed page relocated to a mirror.

The other book of posies published in the 1640s is the signiflcantly enlarged second edition of Loves Garland: or, Posies for Rings, Handkerchers, & Gloves: And such pretty Tokens that Lovers send their Loves. Like Cupids Posies, Loves Garland includes several posies that also appear on extant rings.21 But unlike Cupids Posies, Loves Garland never promises assistance to the lovelorn but instead presents posies of extraordinary material and social specificity. The title of this posy, for example, is longer than the great majority of posies in rings: ‘The posie of a pitifull Lover writ in a Riban Carnation three penny broad, and wound about a fair branch of Rosemary, upon which he wittily playes thus.’ This pitiful lover’s token is not a vague ring, but a ribbon of a specific width and a specific colour twisted around a specific plant. The posy calls for an even more specific situation:

Rosemary Rose, I send to thee,

In hope that thou wilt marry me.

Nothing can be sweete Rose,

More sweeter unto Harry,

Then marry Rose,

Sweeter than this Rose mary.22

This posy only works if a man named Harry sends rosemary bundled as the title describes to a woman named Rose as a proposal of marriage. And in Loves Garland, Rose responds in kind, with a posy entitled, ‘The sweet reply in a conceit of the same cut, sent by Rose with a Viall of Rose-water of her own making’:

Thy sweet commends againe,

my sweetest Harry,

And sweet Rose water

for thy sweet Rosemary,

By which viall

sweet Rose doth let thee see,

Thy love’s as sweet to her,

as hers to thee.23

Although this posy provides a relatively rare example of a posy supposedly designed and sent by a woman, it seems more concerned with completing a narrative than with providing models for female readers. A number of the posies in Loves Garland require similarly specific conditions, while others are brief, portable fragments like those inscribed in rings.

This overview of posies in printed books underscores the difficulty, even impossibility, of distinguishing posies offered as practical assistance from those offered for appreciation. Again, ‘literary’ and ‘didactic’ seem thoroughly intertwined in many early modern texts and practices. The question, however, is not simply whether the posies in printed books were meant to be actually carved into other objects or only enjoyed on the page, but how those possibilities are entangled: how and why does imagining a poem in a book scratched onto a ring or woven into a scarf enhance the value of the poem on the page? How and why might a printed book be a valuable source for mottoes to be inscribed on other surfaces?

The interplay of these questions reveals the complex position of printed verse collections in seventeenth-century England, especially at mid-century: on the one hand, they can function as repositories of authority, and on the other hand, their material fragility requires that they constantly be re-imagined as something else – metal, wood, stone, cloth. Scholars have shown how seventeenth-century literary books could become monumental assertions of authorial will, a process often said to start with Ben Jonson’s Workes of 1616, but the century’s lingering doubts about printed pages have been less often discussed.24 Many of the events of mid-century seem to have exacerbated those doubts: if marble monuments can be destroyed in tumultuous times, what will become of paper monuments? Posies of the 1640s and 1650s suggest how the promise of didactic utility could project literary texts beyond the fragility of printed books, imaginatively transferring poems from pages to rings, from ‘literary’ to ‘didactic’.

In both the case of posies and the case of ‘An Index’, the fluctuating relation between the didactic and the literary corresponds to the unclear status of printed books in mid-seventeenth-century England: a book of poems could offer a new mode of authority and hence provide a new resource for didactic appropriation, or a book of poems could emphasize its own fragility and hence project didactic uses for its poems. In the first case, an apparently literary apparatus frames didactic texts, and in the second, an apparently didactic apparatus frames literary texts. Before John Oldham worried in 1694 that his Poems and Translations did not flt readers’ expectations for literary books, his predecessors at mid-century worried that readers – and worse, nonreaders – would have no informed expectations and would not be able to see the differences between a literary work and a useful commodity. For example, scholars have recognized the literary ambition of Robert Herrick’s Hesperides (1648), but as one of several poems entitled ‘To His Book’ shows, Herrick seems particularly concerned about how tradesmen might use his book:

Make haste away, and let one be

A friendly Patron unto thee:

Lest rapt from hence, I see thee lye

Torn for the use of Pasetrie:

Or see thy injur’d Leaves serve well,

To make loose Gownes for Mackarell:

Or see the Grocers in a trice,

Make hoods of thee to serve out Spice.25

Herrick fears that his book will be put to practical use as a material object, so that his words are not only wrested out of context, as in ‘An Index’, but become irrelevant. Herrick’s cooks and grocers have not yet learned that some books are for appreciating and some are for using in their daily labour, but Herrick’s representation of these thoughtless, possibly illiterate tradesmen contributed to the valorization of the literary book as a special artifact, properly separate from the workaday world. In 1648, however, that separation had not yet prevailed, so that what we now call ‘didactic literature’ cannot always be easily distinguished from what we call ‘literature’.

2 Lisa Jardine and Anthony Grafton, ‘”Studied for action”: how Gabriel Harvey read his Livy’, Past and Present, 129 (1990), 30-78, pp. 30-1.

5 The following discussion refers to a specific copy of Poems by J. D. (London, 1633) held at the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington D.C., STC 7042, copy 2.

7 For rich discussions of seventeenth-century practices of gathering textual fragments in commonplace books, see Peter Beal, ‘Notions in garrison: the seventeenth-century commonplace book’, in New Way of Looking at Old Texts: Papers of the Renaissance English Text Society, 1985-1991, ed. W. Speed Hill (Binghamton, NY, 1993), pp. 131-47 and Max W. Thomas, ‘Reading and writing the Renaissance commonplace book: a question of authorship?’ in The Construction of Authorship: Textual Appropriation in Law and Literature, eds Martha Woodmansee and Peter Jaszi (Durham, NC, and London, 1994), pp. 401-15.

9 The word ‘Authentick’ is a rich marker at the intersection of didactic literature and the history of authorship. According to the OED, meanings of ‘authentic’ ‘seem to combine ideas of ‘authoritative” and “original.”’ Because both meanings are operative in seventeenth-century England, an ‘authentic’ book can suggest both a trustworthy resource and an accurate representation of an author’s achievement, a book thus suitable both for appropriation and appreciation.

10 Rebecca W. Bushnell, A Culture of Teaching: Easy Modern Humanism in Theory and Practice (Ithaca, 1996), p. 138.

12 See George Puttenham’s definition of the posy in The Arte of English Poesie (London, 1589), p. 47. According to Puttenham, his contemporaries ‘do paint them [posies] now a dayes upon the backe sides of our fruite trenchers of wood, or use them as devises in rings and armes and about such courtly purposes.’

16 Ann Baynes Coiro, ‘Milton and class identity: the publication of Areopagitica and the 1645 Poem’s, Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 22 (1992), 261-89, p. 277.

19 Juliet Fleming, ‘Graffiti, grammatology, and the age of Shakespeare’, in Renaissance Culture and the Everyday, eds Patricia Fumerton and Simon Hunt (Philadelphia, 1999), pp. 315-51.

22 Loves Garland: or, Posies for Rings, Hand-kerchers, & Gloves: And such pretry Tokens that Lovers send their Loves (London, 1648), sig. A7v.

24 For a discussion of print authorship that emphasizes the foundational status of Jonson’s Workes, see Richard C. Newton, ‘Jonson and the (re-)invention of the book’, in Classic and Cavalier: Essays on Jonson and the Sons of Ben, eds Claude J. Summers and Ted-Larry Pebworth (Pittsburgh, 1982), pp. 31-55. For a more inclusive history that traces the rising status of poetic authorship in seventeenth-century England, see Marotti, Manuscript.