Chapter 7

Modern readers seem to have an inexhaustible appetite for gardening books: bookshops display an astonishing bounty of texts in the gardening section (usually located near the interior decorating and cooking areas). The overwhelmed booksellers categorize these books differently in every store: for example, you will find sections with books on annuals, perennials, vegetables, or roses (grouped by plant types), but also areas on container gardening, shade gardening, or organic gardening (grouped by type of garden practice). Writers, publishers, and booksellers alike face questions not easy to answer: why do gardeners need books? How do they use them? How does a book shape gardening practice, and how, in turn, is it shaped by practice or use?

Every gardener knows that reading about gardening and doing it are very different experiences and not just in the volume of sweat generated. The knowledge gained by reading books is not the same as that generated by practice in the garden. Practice and the knowledge gained from experience are always local and time-bound. Experience may generate a rule that holds true for a succession of seasons, but even then, an individual garden climate can change over time, as trees grow or fall, or structures rise. The rules in books may try to address variation, but in the end, these rules depict an ideal, rather than real, garden, one that exists only in the mind and between the covers of the book.

This essay explores several aspects of the complex relationship between book and practice that were in play when the gardening book developed in England in the early modern period. My concern here with printed books is quite deliberate, for, indeed, while writers had long produced herbals and gardening instructions in manuscript, the growth of the horticultural advice business cannot be separated from the history of the printed book. In his study of early modern secrets books William Eamon has argued that print technology profoundly influenced the organization and dissemination of all kinds of ‘popular’ knowledge and instruction: as he writes, ‘one of typography’s most important contributions to sixteenth-century literature was to produce a barrage of how-to-do-it manuals and of technological treatises detailing the manual side of the arts’.1 Eamon argues that in this case,

It should be stressed that printers, not craftsmen, created the Kunstbüchlein and were largely responsible for disseminating technological information in the early sixteenth century. Although these works had their origins in the workshops, the information was gathered, assembled and distributed by printers who recognized the needs of a new body of readers. To the random assortments of recipes that had formerly circulated among craftsmen, printers added tide pages, tables of contents, glossaries of technical terms, and prefaces bringing them to the attention of a new public.2

As in other how-to books, the gardening book used the apparatus of the printed book – title pages, prefaces, woodcuts, tables of contents, and indices – to shape the rhetoric of instruction; at the same time market pressures influenced how the books were formatted and produced for different sorts of gardeners.

The first part of this essay examines some of the ways in which garden books self-consciously described their own use, in pointing to their size, comprehensiveness, style, and cost. The second half focuses on the role of illustrations in the seventeenth-century English horticultural manual, which was designed to instruct the readers in the cultivation of flowers and fruit (as opposed to the herbal, a book about plants that focused more on their medicinal uses than their cultivation, or the florilegium, which served only to depict flowers and plants). The use of illustrations was linked in contradictory ways to the market, insofar as illustrations affected both the cost and accessibility of books. However, I would also argue that technology of the woodcut illustration conveyed a distinct image of practice to the gardener: the woodcut’s restrained form suggests the cutting, binding and shaping of plants to what William Lawson calls their ‘perfect form’. In this sense, above all, the early gardening book’s form as a book represented the profession’s belief in the power of the gardener’s technique and mastery over the organic forms of nature.

Books as tools

As the gardening book took shape in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, writers, together with the printers, disputed what it meant to design such a book. The extremes are marked at one end by John Parkinson’s Paradisi in Sole (1629), and at the other end by William Lawson’s The Country Housewifes Garden (1617). Parkinson’s book is a compendious and amply illustrated folio volume, dedicated to the Queen Henrietta Maria; Lawson’s book is a slim quarto design for use by the generic ‘country housewife’.

Parkinson’s massive volume is prefaced by numerous letters of commendation, comprehensive in its coverage of the known plants of his time, and generously illustrated with woodcuts. In this sense, the book resembles most of the folio herbals of its time. The first printed herbal, Banckes’ Herbal, first published in 1525, was small and modest in style; almost at the same time (1526) appeared The Grete Herbal (translated from French), a folio volume of 372 pages, with abundant illustrations. From this point on, buyers of herbals could choose from amongst small quarto books and larger folio editions, but it was the large folio editions such as John Gerard’s Herbal that set the standard for the genre.

However, Parkinson took care to distinguish his Paradisi in Sole from a herbal, expecting that his distinct audience would require a new kind of book. His letter to the reader complains that

none of them [the herbals] have particularly severed those that are beautifull flower plants, fit to store a garden of delight and pleasure, from the wilde and unfit: but have enterlaced many, one among another, whereby many that have desired to have faire flowers, have not known either what to choose, or what to desire. Divers Bookes of Flowers also have been set forth, some in our owne Countrey, and more in others, all which are as it were but handfuls snatched from the plentifull Treasury of Nature, none of them being willing or able to open all sorts, and declare them fully; … To satisfie therefore their desires that are lovers of such Delights, I took upon me this labour and charge, and have here selected and set forth a Garden of all the chiefest for choyce, and fairest for shew, from among all the severall Tribes and Kindreds of Natures beauty, and have ranked them as neere as I could, or as the worke would permit, in affinity one unto another.3

Parkinson’s book thus promotes at once its own selectivity and its comprehensiveness, appropriate for a reader interested in garden aesthetics but not for the physician or householder interested in using plants to cure diseases. The herbal’s form was highly conservative, organized around the description of plants for their human uses and detailing the kinds, the description, the place, the names, the temperature, and the ‘virtues’.4 When John Gerard published his herbal in 1597, he saw himself as following William Turner, while improving and amplifying his approach. When Thomas Johnson came, in turn, to prepare a new edition of Gerard’s herbal in 1636, he presented his book as setting out the latest word in herbals (while it was really an overlay onto the text, with additions and corrections marked by a double cross mark) – a typical way of marketing a herbal as ‘new and improved’ yet not substantially different. Parkinson, however, imagines his reader as needing a new book not just because it has more items but because he has organized plants according to their ‘beauty’ and ‘affinities’, not for their medicinal uses. Further, he asks his reader to appreciate that he has presented his plants in ‘ranks’ in both senses of the word: both by affinity group and in a hierarchy. The book’s large size, the accumulation of letters of dedication, the comprehensive index including both Latin and English names, all add up to fashion a book meant to shape an aristocratic garden aesthetic: one that is refined, exclusive, authoritative and orderly.

In contrast, William Lawson’s The Countrie Housewifes Garden, containing rules for herbes of common use is a brief quarto pamphlet. Its few illustrations are ten patterns for knots, and the rules of cultivation are succinct. It also includes a section on the ‘husbandrye of Bees, published with secrets, very necessary for every housewife’. The book has no letter of dedication or epistle to the reader; it also lacks an index (the very short table of contents appears at the end of the book). Aware of the book’s conspicuous brevity, Lawson does offer a short note of explanation:

I recken these hearbes onely, because I teach my Country Housewife, not skilfull Artists, and it should be an endles labour, and would make the matter tedious to recken up, Landibeefe, Stocke-July flowers, Charvall, Valerian, Go-to-bed-at noone, Pyonye, Licoras, Tansye, Garden-mints, Germander, Centaurie, and a thousand such Physicke hearbes. Let her first grow cunning in this, and then she may inlarge her Garden, as her skill and ability increaseth. And to helpe her the more, I have set her downe these observations.5

The implication here is that in fact the country housewife hardly even needs or wants a book, since first she should learn through the experience of growing those things for which true ‘skilful artists’ do not care. Indeed, while he does offer designs for garden forms, Lawson also assumes that the housewife will be busy with her own practice, and less concerned with books:

The number of formes, mazes and knots is so great, and men are so diversly delighted, that I leave everie Housewife to her selfe, especially seeing to set down many had bin but to fill much paper, yet lest I deprive her of all delight and direction, let her view these few, choyce, new formes[.]6

Again, the writer betrays some impatience with writing too much for this reader, even as he displays his trust in her instinctive knowledge of what is delightful and his awareness of her possible attraction to novelty.

Lawson concludes his gardening section by emphasizing, once again, that his book is only as good as the housewife who uses it:

Thus have I limmed out a Garden to our Country Housewifes, and given them rules for common hearbes. If any of them (as sometimes they are) be knotty, I refer them to other Writers. The skill and paines of Weeding the Garden with weeding knives or fingers, I refer to her selfe, and her maides, willing them to take the opportunity after a showre of raine; with all I advise the Mistresse, eyther to be present her selfe, or to teach her maides to know hearbes from weedes.7

It is apparently not gender that differentiates Parkinson’s grand volume and Lawson’s slim pamphlet, since both of them imagine a female reader: but the one was a queen, who stood in for ‘the Lover of these delights’ of the garden, whereas the other was a country housewife (albeit one equipped with servants), concerned with the productivity of her own plot of land. For Parkinson’s reader, the garden book was both a treasury and an image of an ordered and ranked society of nature; for Lawson’s housewife, it was a supplement to her practice, and thus as casual and unsystematic in form as that practice itself.

The flower gardening books of the second half of the seventeenth century often self-consciously react to the example set by Parkinson’s folio volume, as well as the folio herbals. In his Flora: seu, De Florum Cultura. or A Complete Florilege (London, 1665), John Rea tells the reader that he looked at Parkinson’s book and thought about revising it. However, he came to the conclusion that an entirely new book needed to be written, because Parkinson’s lacks ‘the addition of many noble things of newer discovery, and that a multitude of those there set out, were by Time grown stale, and for Unworthiness turned out of every good Garden’.8 In fact, his effort is not unlike Parkinson’s. But other later books emphasize the novelty of their useful form, especially with regard to size and cost, and their own accessibility to the ‘general reader’. This difference is explicitly set forth in Samuel Gilbert’s Florist’s Vade Mecum of 1682 (Gilbert was Rea’s son-in-law). As Gilbert describes it, his is a small book, ‘the whole fitted for a pocket companion to all Lovers of Flowers and their propagation’. This text, which provides a month-by-month description of flower cultivation, represents itself as closely modeled on practice, ‘this Tract being really designed for the benefit of the meanest Florist, that perhaps understands not how, or hath not the conveniency in searching a Dictionary to know the meaning of Esculent, Horti culture, Sterilize, … irrigate,&c.’.9 That is, the book is imagined as sufficient unto itself; it is not to be consulted in a library with the aid of a dictionary. Instead, its function as a pocket companion means that it may be literally carried into the garden. Further, its provision of month-by-month advice fashions it in the image of the garden year: it is less a ‘reference book’ and more a story of the gardener’s lived year, day by day.

Gilbert’s notion here of his audience as the ‘meanest florist’, inexpert in technical terms yet at the same time a specialist in flowers, and of his book as entirely oriented toward practice is echoed elsewhere. For example, William Hughes, in The Flower Garden (1672), notes that he does not

intend this first part to Flowrists, Gardeners, or others, who have experience in this recreation, though to them also it may be useful, but chiefly for more plain and ordinary Country men and women as a perpetual Almanack or Remembrancer of them when, and which way, most of their Flowers are to be ordered[.]

On this basis, he justifies his book’s brevity, as ‘the price thereof is small, and therefore within the most ordinary reach which larger books are not’.10 This rhetoric justifying the smaller, pocket volume and accessibility was hardly new in how-to and garden books, but here it became allied with something different, which is ‘scientific’ education for the common gardener.

Let me note, of course, what should be obvious, that much of this rhetoric of accessibility is exactly that: rhetoric. Given what David Cressy and others have told us about the literacy levels of husbandmen and labourers in this period, it is unlikely that these books were widely read by those ‘mean’ folk and workmen of which the prefaces of how-to books so often speak.11 It is maddeningly difficult to establish in fact who were the readers of these books, since they tend not to be the kind of volumes that survived in private libraries. One can at best speculate that the readers of these books were for the most part the literate middling sort, who were the greatest consumers of such artifacts of popular culture, as well as the professional estate gardener and the gentleman interested in the cultivation of his own garden.

In any case, one cannot always conclude that smaller books were more popular. An example from. the history of the herbals themselves may prove a cautionary tale. In 1578, Henry Lyte published his translation of Rembert Dodoens’ herbal as A Niewe Herbal, Or Historie of Plants in a large, amply illustrated folio edition of 779 pages (plus front matter). The front matter includes Lyte’s coat of arms and a letter of dedication to Queen Elizabeth, which states that he is publishing this translation for her pleasure and the country’s profit and to show himself a thankful subject.12 At the same time, his preface to the reader does proclaim that he wanted to translate the text for the good of his country including the ‘unlearned’ if literate reader. In 1606, William Ram decided to publish a ‘digest’ of Lyte, called Rams little Dodeon: A breije epitome of the new herbal, or history of plants, which advertises the virtue of its brevity and little cost in the letter to the reader:

So, as where the geat [sic] booke at large is not to be had, but at a great price, which canot be procured by the poorer sort, my endevor herein hath bin cheifly, to make the benefit of so good, necessary, and profitable a worke to be brought within the reach and compasse aswell of you my poore Countrymen & women, whose lives, healths, ease and welfare is to regarded with the rest, at a smaller price, then the greater Volume is:13

Further, in marked contrast to the dedication to the Queen in Lyte’s book, Ram decided that he should dedicate his version directly to ‘thee my poore and loving countryman whosoever, and to whose hands soever it may come. For whose sake I have desired publication of the same, beseeching Almighty God to blesse us all’.14

Despite Ram’s intentions in writing a popular book, however, the Lyte book seems to have sold better; only one edition of Ram’s book seems to have been published, whereas Lyte’s had achieved four editions by 1619. Wright concludes that a wider range of people were more interested in botany and more willing to spend the money on a folio: ‘Expensive as the large herbals were, the interest of the public was such that many a citizen who would have begrudged a few pence for any lesser book, parted with the price of one of the huge illustrated folios’.15 It is also possible that the audience at which Ram’s book was directed did not in fact exist as he describes it, whereas Lyte’s introduction, which includes the rhetoric of public service to the meaner sort, shows a better sense of how the market worked.16 If we accept Wright’s argument, this story thus suggests that it cannot necessarily be concluded that more people bought cheaper books.

However, it is also true that it was not just the poor, in turn, who benefited from smaller and cheaper books. In his conclusion to his epistle of his Adam in Eden: or, Natures Paradise. A History of Plants, Fruits, Herbs and Flowers, William Coles deliberately defined his book’s readership as that of both professionals (‘Physicians, Chirurgions & Apothecaries’) and the ‘Nobility and Gentry’, as opposed to the ‘poore countrymen’ to whom Ram had dedicated his book. When he then commends his own book for its brevity and low cost, in this case, it appears it was not to increase its accessibility to the unlearned; rather it was a mark of the book’s professional value:

When I undertook this work, I was not insensible of the meanenesse of mine own endowments, neither did I, without a modest reflection upon my selfe, survey those larger gifts which Mr. Gerard, Mr. Johnson, and Mr. Parkinson present unto the World: Not to mention many other Writers: for they stood on the shoulders of others, as I am sometimes faine to do: I thought it no adventure, but a necessary endeavour to do my Country further service: and, without arrogance I avouch it, I determined my selfe happy in these my undertakings and that more especially for these following Reasons. 1. As their Volumes are too chargable for every common Buyer, so they are fraught with divers passages that tend not to edification, all which I have waved.17

By the middle of the seventeenth century, it appears that brevity and smaller cost were less marks of a class distinction than a standard for books of science that were intended to be kept in hand.

In the earlier period, then, one can argue that the status of the folio books was a firm selling point to the better sort; in the latter period, however, a smaller book was just as saleable to the better sort, in this case because it was brief, practical and up-to-date. When John Worlidge declared in his Systema Horticulturae that ‘my principal design [is] not only to excite or animate such that have fair estates and pleasant Seats in the Country to adorn and beautifie them: But to encourage the honest and plain Countreyman in the improvement of his Ville, by enlarging the bounds and limits of his Gardens as well as his Orchards, for the encrease of such Esculent Plants that may be useful and beneficial to himself and his Neighbours’, he is explicitly fitting his project into the broader aims of the Royal Society and men such as Samuel Hartlib. He tells the reader that he has shaped his books for this broad audience according to the guidelines set by Ralph Austen in his book on The Spiritual Uses of Orchards:

I hope therefore that this objection will have no place against this tract, the rather because it hath the characters (that Mr. Austin hath proposed in his Epistle dedicatory, before his Treatise of Fruit-Trees) that books of this nature should have viz. I. That they be of small bulk and price, wherein I hope I have conformed, considering the variety of matter herein discoursed of.18

The strictures to which Worlidge refers come from the second edition of Austen’s treatise’s epistle dedicatory to Robert Boyle (which replaced a letter to Samuel Hartlib in the earlier edition). In that letter, Austen cites the following requirements of the characters of books that will serve the new husbandry:

First, that they be of small Bulk and Price; because great Volumes (as many are upon this Subject) are of too great Price for mean Husbandmen to buy, as also take up more time to peruse then they can spare from other Labours. Secondly, that the Stile and Expressions be plaine and suited to the Vulgar (even to the Capacities of the meanest, for these (Generally) must be the Workmen and Labourers thereabout.19

The size and format of these books are thus tied to the notion of broader readership and accessibility for the ‘mean husbandman’ that is brought up in the case of earlier books. But there is also something new in Worlidge’s adoption of Austen’s strictures for a book designed for both estate owners and honest countrymen. Just as these new books commend themselves on the basis of their accessibility (both in terms of price and readability), they also present themselves as physically useful – as field companions – designed for the character of the people who use them and the nature of their lives. It is very likely that, despite this rhetoric of serving the ‘workman’, these books would fall into the hands of the professional and gentleman reader whose tastes they now suited. The self-image offered here to the owner of this book is that of the practical man who works as much as he reads, even though in reality he might do very little of the work himself.

Picture plants

We now expect any garden book to be lavishly illustrated with full-colour photographs; it is all the more surprising then, to see the bare pages of early gardening manuals (even the herbals have pictures, however crude). Many histories have been written of flower painting and botanical illustration, but this essay focuses on illustrations in horticultural manuals, which few scholars have discussed. In the husbandry and general gardening books, the figures tend to depict tools and horticultural practices (watering, grafting, or weeding) or designs for garden knots, but not flowers or plants. What were these illustrations meant to do?

Some prefaces for the earlier books suggest that illustrations could increase the book’s accessibility. Reynolde Scot, or rather his printer, suggested in his book on growing hops that he included pictures as an aid to the unlettered reader: ‘I also pray you to take somewhat the more paines in conferring the wordes with the figures, which will mutually give lyght one to the other, and finallye will assist the understanding of you the Reader, but cheiflye of him that cannot reade at all, for whose sake bee devised and procured these Figures to be made’.20 Such would also seem to be true of the figures of tools and gardening practices that supplement the texts in books like Gervase Markham’s English Husbandman and William Lawson’s A New Orchard and Garden. For example, Markham’s book pictures the assembling of a plough, piece by piece, as an accompaniment to the text describing the parts of the plough.

At the same time – then as now – illustrations added to the book’s cost, and thus conflicted with the professed aim of accessibility. In his New Orchard William Lawson praises the woodcutter’s art and the printer’s generosity: ‘The Stationer hath (as being most desirous with me, to further the common good) bestowed much cost and care in having the Knots and Models by the best Artizan cutte in great varietie, that nothing might be any way wanting to satisfie the curious desire of those, that would make use of this booke’.21 Apparently the expense of illustrations prevented John Rea from including engravings in his Flora, despite his own desires. In his preface to the reader Rea dismisses the need for pictures:

As for the cutting the Figures of every Plant, especially in Wood, as Mr. Parkinson hath done, I hold to be altogether needless; such Artless things, being good for nothing, unless to raise the Price of the Book, serving neither for Ornament or Information, but rather to puzzle and affright the Spectators into an Aversion, than direct or invite their Affections; for did his Flowers appear no fairer on their stalks in the Garden, than they do on the leaves of his Book, few Ladies would be in love with them, much more than they are with his lovely Picture. I have therefore spared myself and others such unnecessary Charge, and onely added some draughts for Flower-Gardens.22

There is a story behind this argument that woodcuts are unnecessary and indeed undesirable: apparently Rea did want to have illustrations in his book, but the prospect ‘so affrighted the stationers, that they offered him but thirty pounds for his pains. This displeased him so much that he brought home his manuscripts’.23 In this case, it is the writer himself who could not afford to have pictures in the book, even though in his preface he avers that he omitted them, not because they raised the price but because they are unsighdy and crude.

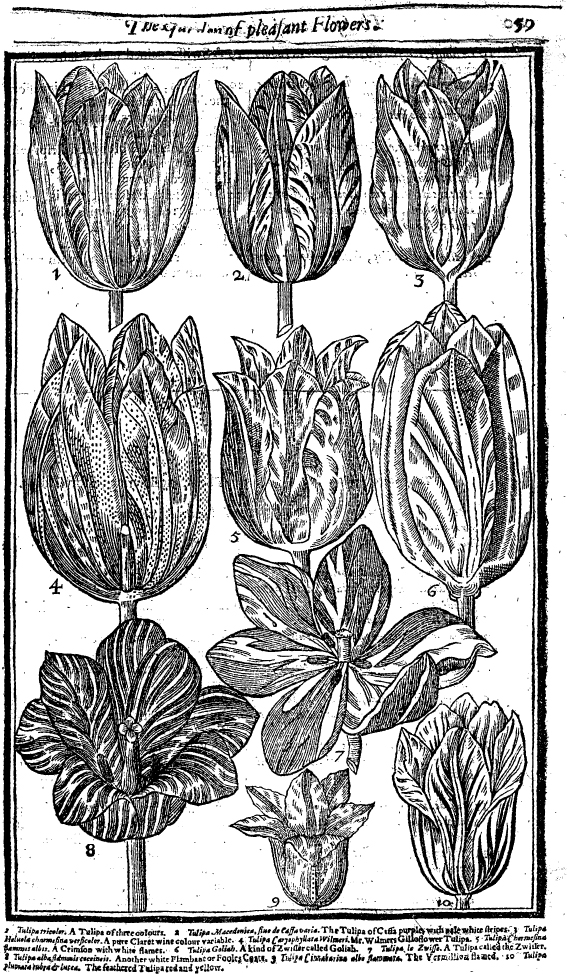

Plate 7.1 ‘Tulips’, in John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole: Paradisus Temstris (London, 1629), p. 59. Reproduced by permission of the Annenberg Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania.

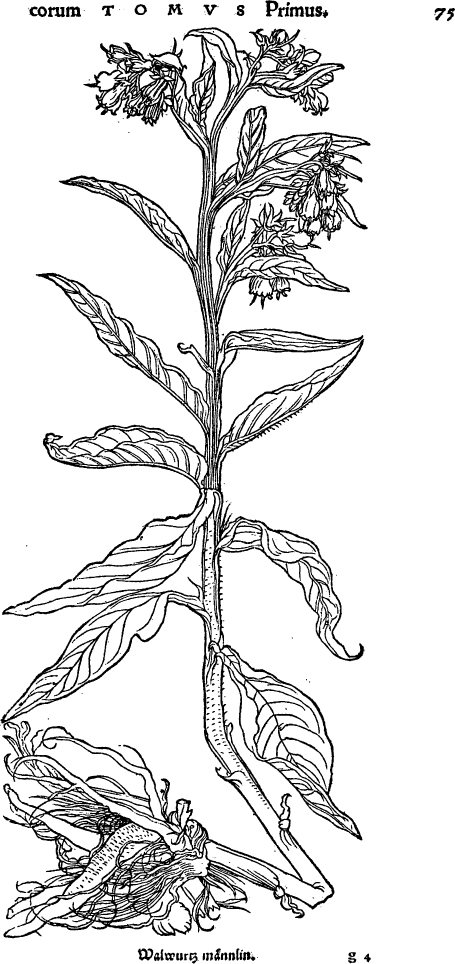

Plate 7.2 Illustration of ‘Walwurz’, in Otto Brunfels, Herbarum vivae eicones (Strasbourg, 1532), p. 75. Reproduced by permission of the Annenberg Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania.

Even while these remarks are thus disingenuous, since Rea would have included illustrations if he could have afforded them, his dismissal of the inadequacy or ‘frightful’ nature of Parkinson’s woodcuts, which cannot show ‘the true beauty of flowers’ (Plate 7.1) suggests a new self-consciousness about the style of such woodcuts, which functioned less to represent plants themselves than an idea of a plant. It is well known that in early herbals crude and inaccurate woodcuts of plant and flower images were used repeatedly (and inappropriately) and reworked. Historians of botany recount how Hans Weiditz in Otto Brunfels’ Herbarum vivae eicones (Strasbourg, 1530-36) and Leonhart Fuchs in his De historia stirpium commentarii insignes (Basel, 1542) broke new ground in representing plants as drawn from life (Plate 7.2).24 Gill Saunders has recendy reframed this narrative by arguing that the traditional herbal woodcuts were intended less to depict the plants than they were to function as elements of the books’ design:

Their value and significance varies with each publication, but generally the illustrations in the earliest printed herbals are little more than decorative motifs breaking up the blocks of text: the Grete Herbal (1526) with its images contained within a framing line, is printed to look like a manuscript, including illuminated initials. The strongly symmetrical illustrations resemble printers’ devices, decorative motifs, ciphers or pictograms of the plants they ‘represent’. With the exception of Fuchs, and some plates in Brunfels, the illustrations in these early herbals are small, cut from the same block as the text (Grete Herbal) or fitted into the text in a cramped and rather arbitrary fashion.25

In line with this function in the book, then, the image of the plant was made symmetrical and rectangular to fit into the woodblock shape.26 If the book was often imagined to be like a garden at this time, these woodblocks convey an image of a garden as a book.27 This regularity and abstraction are, of course, in line with the geometric design of flower plots in general in the period. Markham includes in his books models of ‘the fashion of the garden-plot for pleasure’: ‘the Plaine Square’, ‘the Square Triangular or Circular’ (a square with four triangles and circle inside), ‘the Square of eight Diamonds’.28 It is a world in which the organic is subdued at every level by the knife and the surveyor’s rod.29

Despite the innovations of continental illustrators such as Weiditz and Fuchs, English books continued to use this kind of patterned illustration of plants throughout the seventeenth century. Saunders notes of Parkinson’s Paradisi in Sole, which has the only significant images of flowers in any English gardening manual at the time, that, ‘though most of the illustrations are original they did not gain thereby; they are crude, stiff, schematic … The plant forms are much simplified, stiff and formal; they are often reduced to almost geometric regularity, or to formulaic structures’.30 As Rea suggests, they might not evoke desire in the ladies or aesthetic pleasure; what they do serve to do, however, is to further Parkinson’s aim to represent the natural world as defined by place, order, and rank.

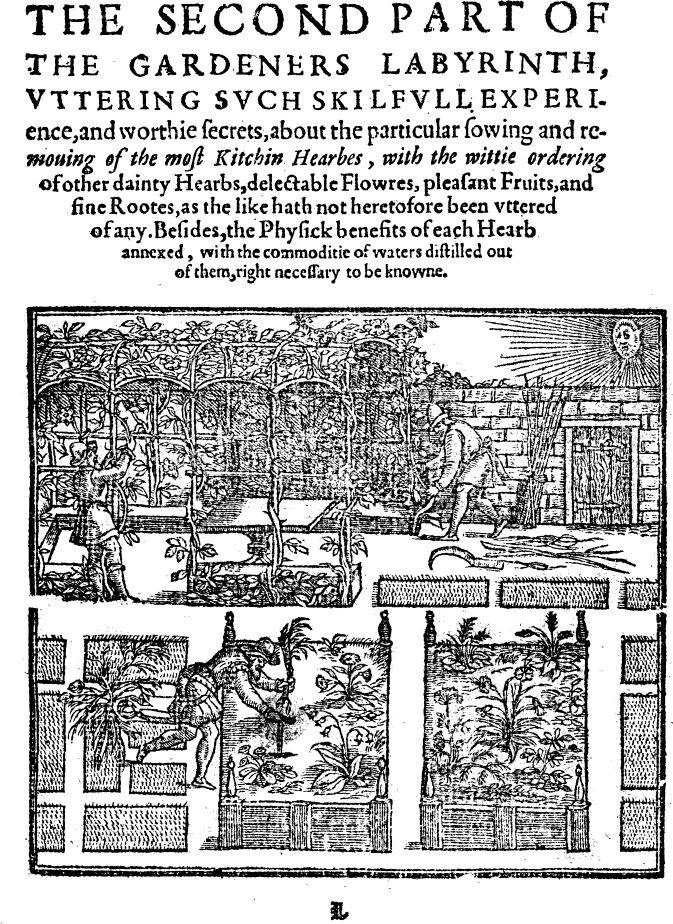

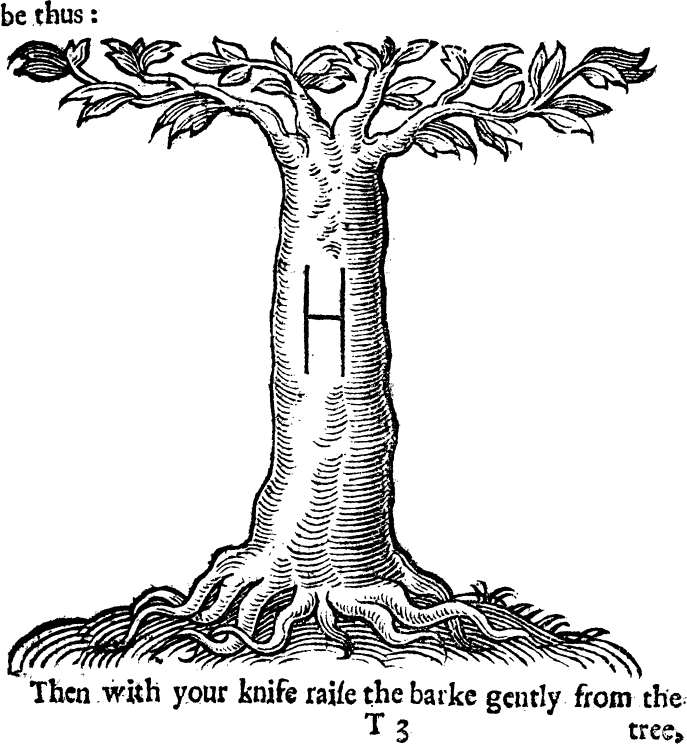

Among horticultural books of the period Parkinson’s book is unusual for having pictures of identifiable plants: for the most part figures are used to illustrate garden practice. Thomas Hill’s Gardener’s Labyrinth (reprinted under several names in the sixteenth and seventeenth century) set the example by offering pictures of appropriate tools with their use in a garden setting, including the second part’s title page image that shows men working in an enclosed garden (Plate 7.3). In this image, some of the plants in the bed are differentiated and possibly identifiable, including what looks like a single gillyflower or dianthus in the bed on the right. However, the woodcut foregrounds the gardener’s technique, rather than the plants themselves. In Markham’s The English Husbandman, even where pictures of plants appear, they are included to depict the uses of tools or garden design. For example, the book includes figures to guide grafting, where the plant bends to the will of the illustrator, as well as to the hand of the gardener (Plate 7.4). In such figures the plant itself is generic and cut to fit the size of the woodblock, bringing it into line with the other ‘model’ and mechanistic illustrations in the rest of the book.31

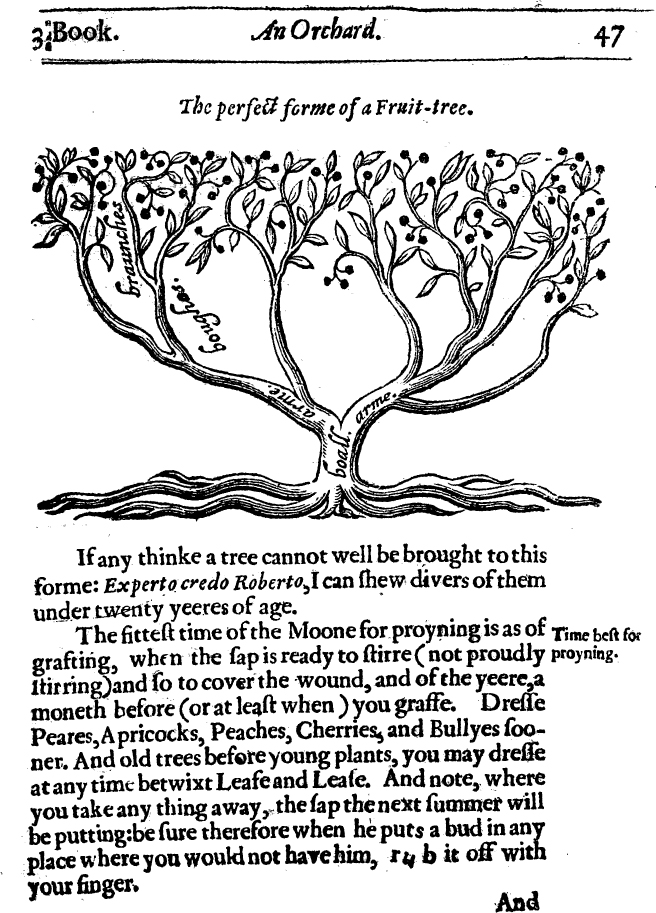

Thus, not only do the regularity and geometric form of the plant’s image reproduce garden geometry, but they also convey the gardener’s confidence in his or her technique and mastery of nature. William Lawson’s entire New Orchard and Garden celebrates the gardener’s regulation of plants. On page 35 Lawson boasts that he ‘can bring any tree (beginning by time) to any forme. The Peate and Holly may bee made to spread, and the Oake to close’.32 This boast is followed by a block print of the ‘perfect forme of an Apple tree’ (Plate 7.5). In this illustration, the ‘perfect forme’ is made to conform to the rectangular shape of the block itself. In the text Lawson does apologize for what he calls the ‘deformity’ of the drawing, but only ‘because I am nothing skilfull eyther in painting or carving’, not because it might be a ‘deformed’ shape of a tree.33 There is a symmetry then, between the body of the book and the shape of the plant (even while the author is conscious of the difference).

Plate 7.3 Frontispiece from the ‘Second Part’, Dydymus Mountain [Thomas Hill], The Gardeners Labyrinth (this edition, London, 1608). Reproduced by permission of the Special Collections Department and the Bush-Brown Horticultural Collection, Special Collections Department, Temple University Libraries.

Plate 7.4 Illustration of a graft, in Gervase Markham, The English Husbandman (London, 1613; this edn, 1635), p. 141. Reproduced by permission of the Special Collections Department and the Bush-Brown Horticultural Collection, Special Collections Department, Temple University Libraries.

Plate 7.5 ‘The perfect forme of a Fruit-tree’, in William Lawson, A New Orchard and Garden (London, 1617/18; this edn, 1648), p. 47. Reproduced by permission of the Special Collections Department and the Bush-Brown Horticultural Collection, Special Collections Department, Temple University Libraries.

The format, shape, typography, and illustrations of a garden book, as much as the content, thus embody a message about garden practice. First, and most critically, their size and paratextual matter send a message about where and how the book is to be used: as a reference tool, an authority, or an accompaniment to work out in the garden – no matter if many of those who consulted the pocket companions may just have been ‘armchair’ gardeners, or masters of others who actually worked in the garden. The illusion they project is of a book itself as a working tool. Further, just as the full-colour illustrations of modern gardening texts evoke desire for a garden that one cannot ever hope to produce, so the early books, too, reveal a fantasy of control and mastery of nature. A successful garden book, then as today, is able to persuade us that, indeed, reading about gardening is close to the act of working in the garden – but it is so much easier.

1 William Eamon, Science and the Secrets of Nature: Books of Secrets in Medieval and Earjy Modern Culture (Princeton, 1994), p. 113.

3 John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole: Paradisus Terrestris (London, 1629; repr. edn New York, 1976), ‘The Epistle to the Reader’, n.p. [p. 3].

4 As Gill Saunders notes, ‘Systematic botany – the process of cataloguing all existing species – has its foundations in the herbal tradition with its practical needs for description and discrimination, but there was no “scientific” method of classification available to the herbalist. Plants in herbals are ordered according to a variety of principles (often within the same book), many of which relate to their medicinal properties. Some followed Dioscorides, Theophrastus and Pliny in distinguishing them according to taste, smell and edibility, or by those parts of the body which they were used to heal’; Gill Saunders, Picturing Plants: An Analytical History of Botanical Illustration (Berkeley, 1995), p. 24.

8 John Rea, Flora: seu, De Florum Cultura. or A Complete Florilege (London, 1665), ‘To the reader’, sig. b1r.

11 It has often been argued, in the case of the history of printing and the book trade, that in the early period of printing in England, the evidence of more books being published means more readers were reading them and that there were more people with sufficient surplus wealth to buy books. See Louis B. Wright, Middle Class Culture in Elizabethan England (Chapel Hill, 1935), p. 81. Since Wright, a great deal of discussion has ensued over the question of the level of literacy in England in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. H. S. Bennett also argued that ‘while the growth of literacy cannot be exactly measured by the output of books from time to time, the two things are not altogether disassociated. The increase in the number of printers must be linked to the growing demand for their wares’; H. S. Bennett, English Books and Readers 1457-1557 (Cambridge, 1952), p. 29. David Cressy, in his important work on literacy, has criticized this kind of argument, noting that ‘a relatively small number of regular book-buyers could absorb most of the output of the London press, and when output increased it is at least conceivable that the same people bought more’; David Cressy, Literary and the Social Order: Reading and Writing in Tudor and Stuart England (Cambridge, 1980), p. 47. Cressy argues for a much lower level of literacy across English society, especially among those who lived in the country and who could be classified at the rank of yeoman or husbandman.

13 Rams little Dodeon [sic]: A breife epitome of the new herbal, or history of plants … Collected out of the most exquisite newe herball, or history of plants, … by … D. Reinbert Dodeon, … and lately translated into English by Henry Lyte, Esquire: And now collected and abridged by William Ram, Gent. (London, 1606), sig. A2r.

15 Wright, Middle Class Culture, p. 576. In the case of Gerard, Wright notes that in the Huntington copy of Johnson’s 1633 Gerard, a note on the flyleaf tells us that it cost £2 8s, on 1 September 1654 (p. 577). See also Bennett, English Books,’Up to about 1550 most herbals were of little consequence … The herbalists of the second half of the century had a high standard to keep, and the day of the cheap, ill-informed little book was over. The few herbals that were printed were for the most part large and well-illustrated volumes, and also for the most part translations’ (pp. 187-8). Terry Comito compares the ‘predominantly middle class audience’ of the gardening manuals to the ‘aristocratic patrons of the herbals’, but it is unlikely that the audiences can be separated so distinctly (since the herbals varied so much in format and size); Terry Comito, The Idea of the Garden in the Renaissance (New Brunswick, 1978), p. 21.

16 At the same time, there is evidence that people thought that the market could only support the publication of a few of such large folios at a time: in 1635, John Parkinson’s massive herbal Theatrum Botanicum, was entered by its printer Richard Cotes into the Stationer’s Register (on 3 March) but it did not appear until 1640, presumably because of the competition offered by Thomas Johnson’s reissuing of Gerard’s Herbal in 1633 and again in 1636. See Blanche Henrey, British Botanical and Horticultural Literature before 1800 (2 vols, London, 1975), i, p. 80.

17 William Coles, Adam in Eden, or, Natures Paradise (London, 1657), sig. (a)1v. Coles also insists that ‘neither have I persued this imployment only for the private contentment that I received thereby, much lesse out of greedinesse of gaine, but from a Zeale to the publique good, as having observed, that through the ignorance and negligence of pretenders to the knowledge of this art, sundry unhansome dysasters to have happened to the ruine of many, and amonge those, to some that deserved most of their Country’ (ibid.).

18 John Worlidge, Systema Horticulturae. or, The Art of Gardening (London, 1677; repr. edn, New York, 1982), sig. A5v.

19 Ralph Austen, A treatise of fruit-trees … The third impression, revised with additions (Oxford, 1665), sigs A4v-A5r.

20 This note comes from ‘The Printer to the Reader’, a letter in the 1574 edition, omitted from later editions: A Perfite platforme of a Hoppe Garden, and necessarie Instructions for the making and maytenaounce thereof, with notes and rules for reformation of all abuses, commonly practiced therein, very necessarie and expedient for all men to have, which in atry wise have to doe with Hops. Made by Reynolde Scot (London, 1574), sigs B3r-B3v.

22 Rea, Flora, sig. b2r. See also Coles’ critique of the cuts in herbals of his time: ‘Though their Cutts do take up much roome and render their Books much more abundantly deare, yet they are so much inferior to those of Matthiolus and Dioscorides, in respect of the smallnesse of their Size, and the false placing of them, that the Botanick is as commonly puzzled as satisfied, and thereby disabled to give an ingenious account of them.’ (Adam in Eden, sigs a1 v-a2r).

23 See Henrey, British Botanical Literature, i, p. 195, citing a letter to Samuel Hartlib (repeated in one of Hartlib’s letters to Boyle).

24 See Saunders, Picturing Plants, Chapter 1.

26 ‘The obsessive impulse towards symmetry and rectangularization was disrupted by Brunfels and Fuchs’: Ibid., p. 32.

27 See Rebecca Bushnell, A Culture of Teaching: Easy Modern Humanism in Theory and Practice (Ithaca, 1996), Chapter 4.

29 I am grateful to Crystal Bartolovich for sharing with me her presently unpublished work on the subject of surveying. See also Andrew McRae, God Speed the Plough: The Representation of Agrarian England, 1500-1660 (Cambridge, 1996), Chapter 6.