Chapter 6

French Conversation or ‘Glittering Gibberish’? Learning French in Eighteenth-Century England

The idea that French is a frivolous and ‘showy’ female accomplishment has beleaguered the study of French in England for over a hundred years. It has meant that for English men to speak French is somehow effeminate.1 But it has not always been so. What tends to be forgotten is that for centuries, no English gentleman would have been considered accomplished if he did not speak French. French had long been central to the education of the English nobility of both sexes, and was considered essential not just to the social, but to the public career of young men of rank. But it was in the eighteenth century that French cultural practices and the French language became central to the fashioning of the gentleman.2 This is related to the rise of ‘Politeness’, a ‘complete system of manners and conduct based on the arts of conversation’.3 Since French was thought to be the most polite and refined European tongue, it was not just fashionable for gentlemen to learn it, but also necessary. Thus, though both sexes were expected to speak French, it was actually more important for men to know it than for women. Indeed, as educationalist Vicesimus Knox remarked in 1781, for a gentleman ‘to be ignorant of [French] is both a disgrace and a disadvantage’.4 By the middle of the nineteenth century, this had all changed. “While the fashion for learning French had increased for girls, English gentlemen either knew French but pretended not to, or did not know it at all. Prime Minister Melbourne who, according to Queen Victoria spoke French ‘very well’, ‘took pleasure in the affectation that he spoke French badly’.5

The aim of this chapter is to trace this remarkable transformation by looking at grammars for teaching French in England over the eighteenth century.6 These texts reveal that there was a shift from an emphasis on speaking and conversation in the early part of the century, to a stress on grammar at the end of the century. This shift, importantly, downgraded speaking, though this is not obvious from what is being said about the aims of French instruction. It also entailed, eventually, a gendering in the study of French, so that by the middle of the nineteenth century ‘French conversation’ had become the female accomplishment par excellence, while French was taught to males as if it was a dead language.7

The authors of the texts were not ‘grammarians’ as such but more or less renowned teachers who wrote up their methods.8 Abel Boyer is one exception, publishing political pamphlets and The English Theophrastus (London, 1699), as well as a famous Dictionnaire Royal (London, 1699).9 His Compleat French Master for Lzdies and Gentlemen was a highly popular grammar, running through sixteen editions between 1694 and 1767. Francis Cheneau, on the other hand, was a well-known teacher who attracted the young nobility and gentry for French instruction at his house in Westminster as well as Bishop Sprat’s sponsorship. Yet another author, Claude Mauger, was ‘the most popular French teacher in the late seventeenth century’.10 Teacher and author Lewis Chambaud’s grammars were recommended by Erasmus Darwin in his Plan for the Conduct of Female Education in Boarding Schoofs.11 Pierre de Lainé was French tutor to the British royal family, while James Fauchon taught French at Cambridge and Philip le Breton was master of the academy in Poland Street, London.

In the introduction to his article on the teaching of French pronunciation in eighteenth-century England, J. S. Spink provided unequivocal evidence of the growing popularity of French study throughout the century. He calculated that ‘between 1694 and 1800 no fewer than 88 different grammars, dictionaries and methods … of the French language were published in England’, 47 of the 88 being published after 1780.12 Where was French instruction available? The ‘great schools’ (such as Eton and Westminster) did not include French in their curriculum, as they concentrated on Latin and the classics.13 Grammar schools were usually classical as well, though, as John Roach has argued, they might also offer ‘modern’ subjects, including French. Modern subjects generally constituted the curriculum of the various private schools, academies and boarding schools that flourished in the eighteenth century, since anyone who so wished could establish one.14 Their advertisements typically vaunted their French instruction in more detail than their other offerings.15 Thus, the boarding school for young gentlemen established in 1747 at Theobald’s House near Cheshunt, claimed that ‘for the Ready Attainment of French, a Native of the Country attends Youths from Morning till Night, both in School and at their Diversions’. The boarding school for young ladies run by Mr and Mrs Phillips in Lawrence Street, near Chelsea, advertised in 1750 that ‘for the better and more speedy Accomplishments of the Boarders, Lectures on Religious Subjects and the Social Virtues, in French and English alternately, are given twice a week gratis, in a new Method, never practised before in a Boarding School for young Ladies’.16 These schools were likely to be attended by the middling classes, though debates over the ‘promiscuous’ mix of middling and upper classes, especially in girls’ boarding schools, suggest that the issue is quite complex.17

Elite males and females were both taught mainly at home, especially in the first part of the century, and learned French with a private tutor or governess. There was however a major difference in the way they might achieve fluency. Boys might learn the rudiments of the language at home but they were expected to perfect their French in France, when travelling on their grand tour.18 This was so common a practice that a model letter in a French grammar book has a girl writing to her brother travelling on his grand tour, apologising for her errors: she is only learning French ‘en Angleterre’ while he, à la source in France, is certain to attain perfection.19 Advertisements placed by tutors offering their services took account of this difference. Mr Mack Gregory could teach ‘the French of Paris and Angers’ not just to ‘gentlemen who have not Travel’d’, but to ladies ‘who can’t easily Travel’, promising that they might ‘be as well Accomplished here at Home’.20 Paris and Angers were two cities on grand tourists’ itineraries, where they might have stopped for a while to study French with the local accent. Advertisements also addressed the anxiety that one might be taught a ‘popular’ accent by a teacher or governess of the wrong social class.21 Some authors actually claimed that they would teach the pronunciation of the polite.22

The main difference between pupils was not social class as such, but rather whether they were learned – that is knew Latin – or not. This mattered because at the time, French grammatical categories, like those of English, were stretched onto the frame of Latin grammar. One consequence is that nouns were declined. For example,

Nominative: | une chanson | a song |

Genitive: | d’une chanson | from/of a song |

Dative: | à une chanson | to a song |

Vocative: | O chanson | O song |

Ablative: | d’une chanson | of a song |

Texts sometimes specified whether they were designed for the learned and/or for the unlearned as well. It was not until 1750 that Lewis Chambaud declared that there were ‘no such things as cases and declensions’ in French and English.23 Even then, it took more than fifty years for the practice to be abandoned. Boys from elite families studied Latin and were therefore familiar with both grammar and the vocabulary of grammar, but their sisters were not. However, though Abel Boyer had claimed that females were ‘cloy’d and puzled, by the long intricate Rules which are commonly set down in Grammars’, their lack of Latin grammar training was not generally treated as a serious problem.24 A dialogue in Claude Mauger’s French Grammar shows how they could be taught grammar while learning French – or at least, how French masters thought they would teach them.

Entre une Dame et le Maitre de Langues.

Monsieur, je n’ay pas apris la Langue Larine, je ne sçay pas ce que c’est que Grammaire, qu’un Nom, qu’un Verbe … je voudrais pourtant bien apprendre par Règles … Je vous prie de m’en informer.

Il est très raisonnable … il faut sçavoir les fondemens. La Grammaire est l’Art de bien parler.25

[Sir, I haven’t learned the Latin tongue, I do not know what Grammar, Noun, Verb mean, and yet I would like to learn by rule. Would you please teach me about them.

It is a very reasonable request It is necessary to know the foundations. Grammar is the art of speaking well.]

The lady then asks what is a syllable, then a phrase, then how many parts language is composed of, and so on. At no point is her ignorance used to denigrate her, on the contrary. At mid-century, author James Fauchon even claimed that his female pupil (to whom his book is dedicated) had made more progress ‘without any previous knowledge of Grammatical Rules’ than someone trained ‘of a Scholastick education’.26 While this obviously served to advertise the efficacy of his own method, it also provides evidence that in the eighteenth century, French instruction was not gendered, unlike in the nineteenth century, when females were thought unable to cope with grammar.27

Easy eighteenth-century texts were usually constructed on the following model: a short grammar section which included pronunciation, prosody, the parts of speech, syntax and verbs, and a large section I call ‘language’: vocabulary, ‘Familiar Phrases’, ‘Dialogues’, Gallicisms, Anglicisms and proverbs, poems, ‘Jest and Repartees’, a choice of ‘letters upon Gallantry’ and even songs.28 My discussion of these early texts will focus on ‘Familiar Phrases’ and ‘Dialogues’, as these were considered the main means of achieving the ‘Habit of speaking’.29 ‘Familiar Phrases’ were brief exchanges intended to provide pupils with phrases or sentences which modern language teachers would now call ‘functional’: how to thank, agree, consent and deny, get angry, what to say when playing cards or billiards, how to inquire about the health of one’s interlocutor:

Bonjour Madame | Good day Madam |

Bonjour Mademoiselle | Good day Miss |

Comment vous portez-vous? | How are you? |

Fort bien, à votre service, | Very well, at your service |

D’où venez-vous? | Where are you coming from? |

Je viens de chez nous | I have come from home |

Avez-vous déjeuné | Have you had lunch? |

Pas encore | Not yet |

Voulez-vous déjeuner | Would you like to have lunch? |

Je vous remercie | Thank you |

Je n’ay pas d’appétit | I have no appetite |

Qu’avez-vous? | What is wrong? |

J’ay mal à la tête | I have a headache30 |

and so on.

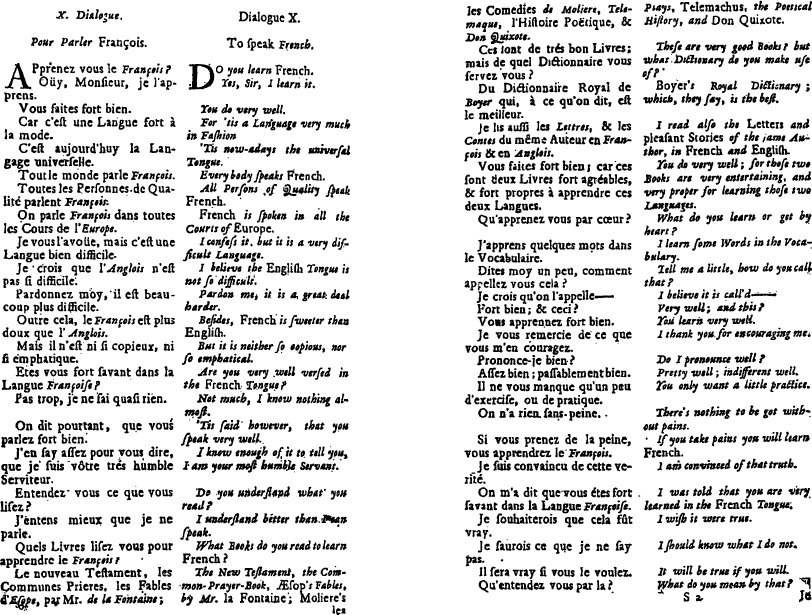

‘Dialogues’ consisted of longer exchanges often depicting the dramas of everyday life. These ‘discourses by way of conversation, both upon serious and delightful Matters’ included dialogues such as ‘between a gentleman and his tailor’, ‘between two young ladies’, ‘between a lover and his mistress’, ‘between a father and a daughter whom he wants to marry off to a much older man’, about the English countryside and the English nation, and, often, a conversation on learning French and how pleasant and important it is to learn this ‘universal’ language.31 ‘Dialogue X: Pour Parler Frans;ois’ (Plate 6.1), concerns the importance of learning French, a universal language and spoken at European courts; the interlocutors compare French and English and which is more difficult to learn; the best method for learning French is to speak it, even if one knows only a few phrases.32

Neither ‘Dialogues’ nor ‘Familiar Phrases’ were graded for difficulty, nor were they designed to illustrate grammatical points. They were intended to be memorized. Dialogues could also serve to advertise an author’s publications – Boyer refers to his own Dictionnaire Royal in the dialogue cited above – or his method; Francis Cheneau, who opposed the memorizing of dialogues, has a character declare that he wants to try Cheneau’s method because learning by rote is so difficult and time-consuming. In another dialogue, someone’s sister has reached the stage of being able to ‘tourner tout I’Anglois en Franrois’ [translate all English into French] quickly and easily because she has followed Cheneau’s method. Dialogues could also be used to make a dig at the competition. Two characters discuss how difficult it is to find a good French teacher. One reason is that he should be both sçavant [learned] and speak French fluently but there are many French teachers who claim to know Latin even when they do not; ‘they use all the same Mauger’s Grammar’ which not only does not explain everything, but is full of errors.33

In addition to memorizing ‘Dialogues’ and phrases for conversation, pupils were encouraged to write ‘compositions’, that is, to translate texts from English to French with a dictionary, referring to rules as the need arose. We learn from Boyer’s ‘Dialogue X’ quoted above what books might be used for such composltions: the common prayers, La Fontaine’s edition of Aesop’s Fables, Molière’s Comedies, Telemachus, Don Quixote. Though some moralists objected, it seems to have been common, especially for girls, to read prayers or psalms in French as part of language practice. Mrs Delany, for example, advised her niece to ‘read the Psalms for the morning in French, and some French lesson’ before breakfast, if there was time.34 Composition was Cheneau’s favourite and much advertised method, as he explains in the introduction to his French Grammar.

Plate 6.1 Excerpt from ‘Dialogue X’, in Abel Boyer, The Compleat French Master for Ladies and Gentlemen (10th edn, London, 1729). British Library shelfmark 1607/249, reproduced by permission of the British Library.

At first, read over all [the grammar] rules two or three days, stop a little to the Articles, and see the Appellative Nouns which take always le, la, les, … and du, de, de la, des … Contrary to the proper names which take not; See the Tables of all the Verbs Regular, and Irregular … Begin the third day to compose by the help of a Dictionary; without which you shall never have the French. Continue every day to turn what English you can into French, and it will not be past a month but you shall find a great Improvement.35

Not surprisingly, a character in a dialogue remarks that one learns much more when one has to find words oneself in a dictionary, as Cheneau recommends. Composition, however, also required that masters spend time correcting the translations. This is perhaps why Cheneau defines a bad teacher as one who just gives his pupils dialogues to learn by heart and not enough compositions.

In the first part of the eighteenth century, there was only one way to proflciency – constant oral practice: ‘La Méthode la plus facile pour apprendre le Franrois, est de le parler souvent’ [The easiest method for learning French is to speak it often].36 As Cheneau tells us, ‘I [have] always caused my Scholars, after their Compositions were perfected, to get them by Heart, and take every Opportunity to speak and hold Discourse; for it is Practice only that can make the greatest Scholar perfect in Conversation of every Language’37 Most authors nevertheless also recommended a foundation in grammar and joining rules to practice.38 Without grammar, wrote Guy Miege, learning a language is ‘properly building in the Air’,39

A comparison of French language teaching texts published in the first and the second half of the eighteenth century reveals that a major shift was taking place. Comparing what two authors said was the best way to learn to speak French highlights the nature of this shift. For Cheneau in 1723, it was by constant practice; for Chambaud in 1758, it was by understanding the rules of the language. The impetus to learn French grammatically rather than by conversation originally lay in the concern to achieve and maintain a standard of correctness, and it would seem that at least until the mid 1770s, there were controversies about whether French should be studied mainly by memorizing texts and practising them orally, or by rules. But the trend towards grammar is clear. For example in the first (1694) edition of Abel Boyer’s Compleat French Master, the number of pages allocated to grammar is 127 and to vocabulary and language is 254; in the eighth edition of 1729, the number of pages allocated to grammar is 157 and to language, 215. By contrast, in Lewis Chambaud’s Grammar of the French Tongue (1758), the grammar section takes up 306 pages and the language section 55, and in V. J. Peyton’s The True Principles of the French Language (1757), the grammar section spreads over 392 pages and the language section over 156 pages.40 The ‘Art of Grammar’, wrote Peyton, was ‘the golden Key to unlock all other liberal Arts and Sciences’. To learn it meant becoming one of the initiates, an invitation directed particularly at females.41 There was also a practical reason why a grammar-based method was attractive. Learning large amounts of vocabulary and dialogues by rote was very time-consuming, and the claims made for grammar made it appear like a short cut to proflciency. But there were other reasons as well.

It is the way Lewis Chambaud defined grammar that best reveals the tenor of the shift. In the introduction to the Grammar of the French Tongue, he defined ‘grammar’, conventionally, as ‘the art of speaking a language’ but in addition, he defined an ‘art’ as ‘a set of Rules digested into a methodical order, for the teaching and learning of something.’42 The key word here is ‘rule’. Like Cheneau and Boyer, Chambaud’s aim was to enable students to converse on all occasions, but his method for achieving fluency was diametrically opposed to theirs. For them and other authors in the first part of the century, rules were a sort of mode d’emploi, a set of practical instructions to help composition, conversation and correctness. This is precisely what Chambaud criticized: masters make students ‘get by heart words and common loose-sentences, but without shewing them what grammatical dependance [sic] each word has upon another’. When pupils translate French authors, he advised, they must ‘minutely’ take notice of the order of the construction, and then, and not before, turn English into French.43 Chambaud stressed rules and syntax not merely to achieve correctness, but because The right placing and using of words … require a constant and steady application of mind, and cannot be acquired but by much meditating upon the language’.44 Grammar, unlike rote, involved the mind.

Chambaud’s work is crucial to the history of French language teaching in England, because it represents the emergence of modern methods. The conceptual basis for his method became the rationale for French instruction in the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth. For instance, one central feature of Chambaud’s work was the concept of grading for difficulty, a feature which became commonplace but which earlier texts lacked. Grading is at the heart of Chambaud’s complex re-structuring (or deconstruction) of grammar. The section on pronunciation in The Art of Speaking French is an interesting illustration of his methodology. It is not that previous grammars lacked sections on pronunciation, but that they lacked the careful incremental steps that were at the heart of Chambaud’s method. The pronunciation section, which spreads over seven pages, begins with tables on the pronunciation of all the vowels. The next set is a table of mostly nonsense syllables to be learned by heart.

ou | u | an | in | on | un |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

hou | hu | han | hin | hon | hun |

mou | mu | man | min | mon | mun |

bou | bu | ban | bain | bon | bun |

pou | vu | ven | vin |

|

|

This table is followed by lists of monosyllabic words, aout, beau, bee, mai, mou [August, handsome, beak, May, soft], two more tables of words ending in ‘consonants that ought not to be pronounced’, and one table of combination of sounds. Each step had to be fully mastered before the next was attempted. ‘When [the student] has learnt all those combinations, go through them over again after the same manner … ‘till the Master is convinced by his pupil’s reading that he has them thoroughly, and they have made a lasting impression on his mind.’45

After the pupil had mastered the pronunciation, he was set to learn the grammar, syntax and vocabulary. Chambaud rejected the usual order of presentation starting with articles and began instead with adverbs, prepositions and conjunctions, which he argued were easier because they were invariable. When the pupil had gone through the grammar, ‘make him parse, that is, account for the construction of every word of his lesson, and shew how each governs or is governed of another in the sentence.’ Nothing could be left unexplained because the sooner the student learned these exercises, the sooner he would be able to practise the language.46

Despite the much greater importance he gave to grammar, Chambaud did not completely abandon functional elements of language like the earlier ‘Familiar Phrases’, however the space devoted to these was much reduced.47 His ‘common forms of speech’ include exchanges like the following:

AL’école | At school |

Qu’est-ce que vous avez | What is the matter |

Il se moque de moi | He is making fun of me |

Il me dit des sottises | He says silly things to me |

Venez ça vous deux | Come here both of you |

Monsieur ce n ‘est pas moi | Sir it is not me |

Vous allez avoir le fouet | You will be whipped |

Culotte bas | Down with your trousers |

Monsieur je vous en prie … | Sir I beg you |

Je ne le ferai plus | I will never do it again |

jamais de ma vie.48 | Never in my whole life |

Nor did he oppose ‘Dialogues’ as such, though as early as 1751, he was contemptuous of the ‘Dialogues’ written by French masters – full, as he put it, of ‘oui Monsieur and non Madame … inserted for want of better material’. His own ‘Dialogues’ consisted instead of selected extracts from Moliere’s comedies, because, as he put it with unusual modesty, they were better than any he could have written.49

The preface to The Att of Speaking French (1772), which is a treatise upon method as well as a manual for language teachers, represents the culmination and refinement of Chambaud’s ideas since the early 1750s. In this preface, we can see that the controversy about rote learning and practice versus grammar was still ongoing. ‘Some people’, Chambaud writes, ‘urge that the best way to learn language is … by practice; that it is impossible to make … rules upon a living language, which is entirely grounded upon use; … [and] that ‘tis too tedious and painful for children to get such a Grammar by heart’. But, he argued, there was no other way of attaining ‘exactness and propriety in the writing and speaking of a language … than studying methodically the principles and rules of it, after the manner I propose’. Above all, the aim of language learning was not ‘to pratde something of French’. This was a direct criticism, not just of the methods by which masters ‘labour hard to beat into [the pupilsj heads as many common sentences as they can’, like parrots, but more importandy, of the social role of French in the polite society of the time.50 Like many educationalists and moralists of his day, Chambaud condemned parents’ desire for their children to display in ‘an assembly that they can speak some French words and phrases’.51 While ignorant parents were satisfied, the pupils learned nothing of method or principles, and knew nothing ‘thoroughly’ – a term which was to become a byword of French teaching by the grammatical method. It was precisely because pupils were forced to speak French all the time, Chambaud explained, that they merely acquired ‘the knack of talking a glittering Gibberish, which no-body can make anything of. He even opposed the practice of sending boys to France to live with French families, at least until they were ‘grounded’ in the principles of the language.52 This may seem extreme, but it became the rationale upon which French was taught in the nineteenth century.

As the eighteenth century came to a close, however, increasing numbers of authors noted that learning grammar was ‘disagreeable’ and that the study of language was ‘dry, tedious and tiresome’ or ‘disgustful’ to young people. It was even claimed that ‘many grammars protract the improvement of youth’.53 Grammar had not fulfilled its promise; it was not a panacea. This may account, at least in part, for the proliferation of texts that claimed to avoid the shortcomings of rule-based methods by devising ‘new and original’ plans.54 What these might entail can only be conveyed by providing some illustrations. The ‘originality’ of John Murdoch’s plan, in The Pronunciation and Orthography of the French Lmguage Rendered Perfectly Easy on a Plan Quite Original (1788), consists of introducing sounds in lists of monosyllabic words and nonsense syllables so as not to ‘distract’ the attention from the ‘single focus’ of the sound to be learned. Thus the vowel A is exemplified by a list of words including

a | a |

ça | that |

pat | nonsense syllable |

bac | nonsense syllable |

fac | nonsense syllable |

carnaval | carnival |

caftan | caftan |

plantat | planted |

amassant | gathering |

campagnard | rural |

the vowel O is exemplified by

o | o |

os | bone |

coq | rooster |

bloc | block |

fond | bottom (of container) |

pont | bridge |

porc | pig |

jonc | reed |

By using words containing only the vowel to be exemplified, Murdoch claimed, pupils would avoid the confusions they usually face. He seems however to have overlooked the confusion that was bound to arise when pupils encountered the nasalized ã (in caftan, plantat, amassant and campagnard) and õ (in fond, pont, jonc) in his examples, for which he provides no explanation. Another ‘originality’ is his organization of the vocabulary phonetically, to illustrate sound distinctions. This includes homophone groupings such as cinq, sein, sain, seint [five, breast, healthy, nonsense syllable]; words that differ from each other by one gradation in sound such as somme, sommet [sum, summit]; and finally, ‘those French words where the same letters differ in sound, or signification and sometimes both, according to the accentuation or connection with other words.’ For example, est varies both in sound and in meaning depending on where it is placed in a sentence: il est vrai, est-il vrai, and l’Est est un point cardinal [it is true, is it true, the east is a cardinal point).55

Bridel Arleville’s plan, in Practical Accidence of the French Tongue upon a more Extensive and Easy Plan than any Extant (1798), promised to be an improvement on other grammars because it

join[ed] practice to theory, and of course must facilitate the progress of learners, without constraining them to the tedious task of getting by heart 100, and, as in some Grammars, 160 pages of elementary rules, the dryness and insignificancy of which, when not exemplified, are sufficient to dishearten the most willing scholars.56

Arleville’s ‘easy’ plan produced instead a verb section which spread over one hundred and sixty three pages, about two thirds of his text. The following is an excerpt of his ‘System of Verbs’ that he grouped according to their alphabetical and phonetic terminations. So

Verbs in -aindre

plaindre | to pity |

craindre | to fear |

contraindre | to constrain |

form their singular of the present of the Indicative by changing -dre final of the present of the infinitive into s, s, t, and their perfect like those in -aincre.

Verbs in -eindre

ceindre | to inclose or gird |

feindre | to feign |

peindre | to paint |

enfreindre | to infringe |

empreindre | to imprint |

are conjugated like the verbs in aindre. Verbs with the next termination, oindre, are also said to be conjugated like the verbs in aindre and so on. Each set of terminations was followed by ‘promiscuous exercises’, sentences to translate into French. The exercise following verbs in -aindre, -eindre and -oindre. included sentences such as ‘I besprinkled puss [pussy cat] so finely as to put out all at once the fervour of his friendship; You would openly violate the laws if you were not afraid of punishment; in pretending to go a hunting, he took flight’.57 Though Arleville expected his plan to lessen ‘the labour and fatigue of Teachers’ by contributing to ‘the quicker improvement of their Pupils’, it is not immediately obvious to a modern reader how it facilitated the learning of verbs. Ultimately, one cannot fail to wonder about the efficacy of a system which provides a separate termination for verbs in -euvoir of which pleuvoir is the sole member.58

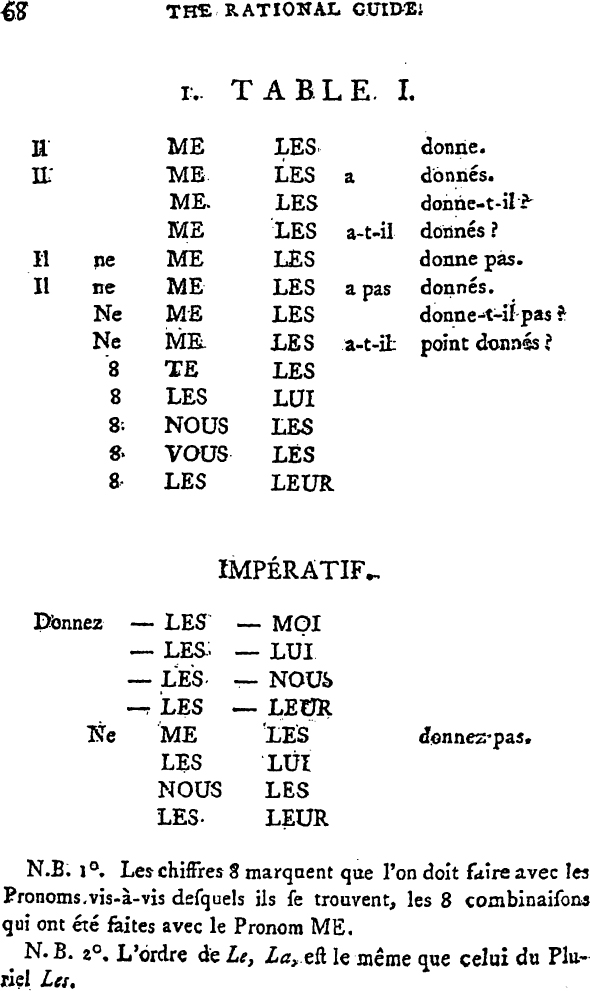

Not all of the new plans and innovations were as ill thought-out as Murdoch’s or as laborious as Arleville’s. Bernard Calbris, for example, designed an elegant set of tables mapping the place of pronouns where the layout on the page clearly illustrates the structural ordering of the pronouns in simple sentences (Plate 6.2). Table 2 and 3 illustrate the same process with Y and En, and Table 4 all the pronouns at once.59

Overall, the most striking characteristic of the grammars and practical plans devised in the latter part of the century is that whatever the organizing principle, it entailed the sacrifice of meaning. From Huguenin Du Mitand’s pronunciation exercises including monosyllabic phrases of the type:

Plate 6.2 Table of the order of pronouns in the passe compose, in Bernard Calbris, The Rational Guide to the French Tongue (London, 1797), p. 68. British Library shelfmark 1212.e.15, reproduced by permission of the British Library.

un bain froid | a cold bath |

un beau jeu | a good game |

deux à deux | two by two |

des oeufs frais | fresh eggs |

je vous ai vu | I saw you |

faire attention | to be careful |

foire banqueroute | to be bankrupt |

faire envie | to make envious |

faire bonne chère | to eat well |

foire semblant | to pretend.63 |

Earlier in the eighteenth century, grammar may have been a way of avoiding memorizing large chunks of language such as those in ‘Dialogues’ or ‘Familiar Phrases’ sections. By the end of the century, learners were still required to memorize large chunks of language, but now these were grammar rules, interminable lists of verbal constructions or nonsense syllables. Pronunciation was practised by reciting rules, and dialogues between teacher and pupil consisted of exchanges about points of grammar.64 The most telling example is Bernard Calbris’ ‘A French Plaidoyer Between Five Young Ladies’. Five young noblewomen are engaged in a contest, organized and arbitrated by their learned aunt the Marquise de _, which consists in explaining clearly and elegantly the rules of French syntax. There is no other conversation between them. The Marquise asks the questions:

Melle Antonine, ne pourriez-vous point dans une seule regie nous expliquer la concordance de L’Adjectif avec le Substantif?’

Melle Antonine replies: L’Adjectif s’accorde avec son substantif (ou ses substantifs) en genre et en nombre; et s’ils sont de different genre, il s’accorde toujours avec le Masculin, excepte le cas ou il n’y auroit que deux substantifs et que l’Adjectif viendroit immediatement apres ce dernier.

[Miss Antonine, could you explain the agreement of the adjective with the noun with one single rule?

Miss Antonine replies: the adjective accords with the noun (or nouns) in gender and number; if they are of different genders, it always accords with the masculine, except when there are only two nouns and the adjective follows the latter].

The Marquise praises the brevity of Melle Antonine’s explication and asks Melle Julie to explain the ordering of adjectives with the same conciseness.65 The contest goes on for 160 pages, providing a thorough exposition of French grammar rules. Calbris may have aimed to enliven the tedious study of dry rules by personalizing it, but the difference between his text and the dialogues in Boyer, Cheneau and even early editions of his own books could not be more dramatic. Although it was still maintained that being able to hold a conversation in French was of the utmost difficulty, ‘Quiconque a l’expérience avouera qu’il a été capable de traduire toute espèce de livres François surtout en prose, avant de pouvoir ou entendre ou tenir une conversation’66 [Anyone who has tried it will admit that he will have been capable of translating all sorts of French books especially in prose before being able to understand or hold a conversation], the very meaning of ‘conversation’ was changing. No longer about the ‘trifling topics of familiar discourse’ and ‘common compliments’ that constituted the knowledge of those taught French conversationally, it could mean just reading aloud.

Throughout the eighteenth century, the ability to converse had been the main aim of French instruction for both sexes, and the possession of a good French accent one of the most desirable of accomplishments. By the second decade of the nineteenth century, the study of French had become gendered. As method was increasingly associated with rationality, and grammar with forming and training the mind, the aim of language teaching to boys became the training and ‘opening’ of the understanding through rules of grammar, and speaking held very much second place in their French language classes. In the best schools, ‘it is usually required that the pupils converse exclusively in French, at least during the hours allotted to the study of that language’.67 These might add up to two or three hours a week. The opposite was true for girls, for whom the fashion for speaking French had been increasing, especially since the French Revolution, with the influx of aristocratic emigres who could teach the best French, spoken at Court.68 And as boys were taught French as if it were Latin, French conversation became the social acquirement without which no young lady would be considered accomplished.69 Indeed, did not Fanny Price’s cousins ‘hold her cheap on finding out that she had but two sashes, and had never learnt French’?70

I am grateful to Carol Percy for judicious comments and useful suggestions on an earlier version of this chapter.

1 Girls usually outnumber boys by about a third in French classrooms, a situation that has long worried the modern language establishment. Among the reasons adduced to explain the gender imbalance, one recurs: boys perceive French to be a ‘girls’ subject’, a ‘female’ language. See Michele Cohen, Fashioning Masculinity: National Identity and Language in the Eighteenth Century (London, 1996). This was exploited in1998 in a television advertisement for a BBC ‘football survival French course’ (as England was preparing to play in France for the World Cup) showing that even men behaving badly – that is, ‘real’ men – could learn to speak French. In the eighteenth century just as today, French was the main foreign language studied. Italian was next most popular, though far fewer people learned it.

3 John Brewer, The Pleasures of the Imagination: English Culture in the Eighteenth Century (London, 1997), p. 111; Lawrence E. Klein, Shriftesbury and the Culture of Politeness: Moral Discourses and Cultural Politics in Easy Eighteenth-Century England (Cambridge, 1994).

6 I am using the term ‘grammars’ loosely, to refer to a variety of texts designed to teach French. Charles P. Bouton, Les Grammaires Françaises de Claude Mauger a IV sage des Anglais (Paris, 1972), suggests that most of these grammars were written by French masters who had become grammarians by necessity. The texts I discuss were selected from R. C. Alston, A Bibliography of the English Language (12 vols, llkley, 1985), xii: I (The French Language Grammars: Miscellaneous Treatises, Dictionaries).

7 The Schools Inquiry Commission (23 vols, London, 1867-8) particularly commended Newcastle Grammar School because it taught French ‘precisely in the same way as the ancient languages … grammar, not vocabulary, being the first consideration’ (viii, p. 401).

8 Claude Amoux complained that ‘as soon as a Frenchman lands in England, if he has not profession or talent, he becomes a French master and publishes a grammar’ (translated by this author from the original French): New and Familiar Phrases and Dialogues in French and English (’4th edition’, London, 1761), ‘Discours critique sur les Grammaires’, sig. A4r.

9 Guy : Miège is another exception. He published The Present State of Great Britain (London, 1708), as well as The Grounds of the French Tongue (London, 1687).

10 Kathleen Lambley, The Teaching and Cultivation of the French Language (Manchester, 1920), p. 300.

12 J. S. Spink, ‘The teaching of French pronunciation in England in the eighteenth century, with particular reference to the diphthong ol, Modern Language Review, 16 (1946), 155-63, p. 155. These figures should be placed in the broader context of the expanding print culture of the period, in particular, that of English grammars. See Carey Mcintosh, The Evolution of English Prose, 1700-1800 (Cambridge, 1998).

13 At Eton, however, French could be taught as an extra, if parents wished to pay for it, a practice that continued well into the nineteenth century and led Mr Tarver, sole French master in the 1860s, to remark that he was a mere ‘objet de luxe’: Clarendon Commission (4 vols, London, 1864), iii, QQ. 3740, 7025.

14 John Roach, A History of Secondary Education in England, 1800-1870 (London, 1986); Nicholas Hans, New Trends in Education in the Eighteenth Century (London, 1951).

15 For young gentlemen, these might include Greek, Latin, bookkeeping, dancing, fencing and fishing; for young ladies, dancing, music, needlework pastrymaking, pickling, drawing and writing.

16 Daniel Lysons, Collectanea; or a collection of advertisements and paragraphs from the newspapers, relating to various subjects (2 vols, London, n.d.), i, p. 17.

17 See P.J. Miller, ‘Women’s education, ‘self-improvement’ and social mobility-a late eighteenth century debate’, British Journal q[Educational Studies, 20 (1972), 302-14; l\fichele Cohen, ‘Gender and the public/private debate on education in the eighteenth century’ (forthcoming).

18 Michèle Cohen, The Grand Tour: constructing the English gendeman in eighteenth-century France’, History q[Education, 21 (1992), 241-57.

21 Thus ‘Mademoiselle Panache’, in Maria Edgeworth, The Good Governess (London, c. 1800) is a lower-class Frenchwoman who poses as middle-class to work as a French governess in an aristocratic family. It is her language that finally exposes her imposture.

25 Modern translation by this author: Claude Mauger, Claudius Mauger’s French Grammar (‘16th edn’, London, 1694), p. 45.

27 In the nineteenth century, the meaning of ‘grammar’ changed, encompassing not just rules and parsing but etymology. See Michael Stubbs, Knowledge about Language: Grammar, Ignorance and Society (London, 1990), for a discussion of the changing meanings of grammar.

28 In these early texts, ‘Familiar Phrases’, ‘Dialogues’, expressions and vocabulary were all laid out in the same manner: each page with French in one column and the corresponding English translation in the other column.

29 Lewis Chambaud, Dialogues French and English Upon The Most Entertaining and Humorous Subjects (London, 1751), p. iii.

32 Abel Boyer, The Compleat French Master for Ladies and Gentlemen (10th edn, London, 1729), pp. 274-6. See also Cheneau, True French Master, pp. 160-1, for a dialogue on the same topic.

40 However, in the latter half of the century, a nwnber of authors published the grammar and the ‘language’ separately.

47 Twelve out of a total of 152 pages in Lewis Chambaud, The Elements of the French Language (London, 1762).

51 Cham baud, A Grammar, p. xix; Art of Speaking, p. xvii. See also Henri Gratte, Nouvelle Grammaire Françoise à l’Usage de la Jeunesse Angloise (London, 1791).

53 George Picard, The English Guide to the French Tongue (London, 1778), ‘Preface’, p. iii; George Picard, A Grammatical Dictionary (London, 1790), Preface; Bernard Calbris, The Rational Guide to the French Tongue (London, 1797), Preface; Marc Antoine Pomy, The Practical French Grammar (this edn, London, 1812; 1st edn, 1763), ‘Preface’, p. ii.

55 John Murdoch, The Pronunciation and Orthography of the French Language Rendered Peifectly Easy on a Plan Quite Original (London, 1788), pp. 4, 8-9, 11.

56 Bridel Arleville, Practical Accidence of the French Tongue upon a more Extensive and Easy Plan than any Extant (London, 1798), p. iii.

57 In this context ‘promiscuous’ means ‘mixed, of various kinds’ (OED); Arleville, Practical Accidence, pp. 7 4-6.

60 Huguenin Du Mitand, A New French Spelling Book (London, 1784); Rev. Jean Baptiste Antoine Gerardot, Elements of French Grammar (London, 1815), p. 25.

62 Gratte, Nouvelle Grammaire, p. viii. This was also the principle upon which Latin was taught: see Knox, Liberal Education.