HOWARD W. BUFFETT

This chapter presents the author’s personal narrative to describe the history and development of the social value investing framework.

The federal government’s role in building and shaping public policy and infrastructure through partnerships with the private and philanthropic sectors has evolved significantly over the past few centuries. So, too, has the scope, scale, and approach of philanthropy itself in the United States.

The so-called Gilded Age philanthropists, or scions of industrial wealth—Rockefeller, Carnegie, Eastman, and others—made unprecedented charitable gifts during their lifetimes.1 These gifts launched an era of modern, otherwise known as professional, philanthropy that continues to influence giving today. In the past thirty-five years, successful businesspeople and entrepreneurs, including Paul Newman, Ted Turner, and Mark Zuckerberg and Pricilla Chan, have committed vast portions of their private wealth to philanthropy.2

A particularly notable event took place on June 26, 2006, at the New York Public Library. My grandfather, Warren Buffett, made a seminal announcement that he would leave almost his entire fortune, valued then at approximately $44 billion, to the benefit of humankind.3 Not only did this announcement shock the world of philanthropy—news outlets heralded it as the beginning of a new era of mega-foundations4—it also stunned the world of finance. My grandfather represents the pinnacle of success in the field of investing; his is an achievement built in a capitalist economy that measures success by how much wealth you accumulate—not by how much you give away. In taking this step, he set an example for others that will continue to have unforeseen ripple effects for years to come.

In a well-known story, my grandfather built his fortune through the business operations of Berkshire Hathaway Inc., utilizing the principles of value investing. Value investing was originally developed in the 1920s by Professors Benjamin Graham and David Dodd of Columbia University.5 In the fall of 1950, my grandfather attended a course titled Investment Management and Security Analysis, taught by Dodd, and the following semester he attended a small seminar taught by Graham.6 These courses, and books by Dodd and Graham—Security Analysis (1934) and The Intelligent Investor (1950)7—provided the necessary framework for engaging in what became one of the most enduring and successful investment paradigms of all time.

Although the approach is based on a complex and rigorous securities analysis framework, many of the main tenets of the value investing methodology are straightforward. For example, when allocating capital, look for investments that are “on sale”—investments that have an intrinsic value beyond what appears on their balance sheets. Assume that the market’s supply and demand curves are often misinformed for investments; investors must establish a minimum size discount, or margin of safety, before they consider making a purchase. Furthermore, investors must resist the temptation to react to media hype or market hysteria. Finally, and perhaps most important, the approach relies on a long-term investment strategy.8

Following these and other principles, my grandfather built one of history’s most successful investment holding companies and amassed what was at one time the largest fortune in the world.9 With his decision in 2006, that fortune became one of history’s largest gifts.10 Traditionally such a donation would go to a namesake foundation under the donor’s close and personal control. However, my grandfather chose a different approach, announcing that he would make annual distributions of Berkshire Hathaway stock to five separate charitable foundations. The bulk of the contributions go to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and other significant commitments go to the Susan T. Buffett Foundation and foundations for each of my grandfather’s children.

My grandfather’s gift caused each of these foundations to face a new and important challenge: given significant resources to accomplish something great in this world, what should be done? The 2006 gift did not come with strict guidelines or overly burdensome stipulations, but my grandfather provided a set of strategic suggestions for the foundations in a letter accompanying each gift.11

The letters encouraged the foundations to focus their new funds and energy on relatively few activities and to take a broad view when evaluating where they could make an important difference in the world. The letters also suggested a concentration of resources on needs that would not be met without the foundation’s specific efforts, which acknowledged the unique and flexible role that philanthropic capital can play in addressing pressing challenges. In light of that flexibility, these letters also encouraged making mistakes, stating that nothing important in life is accomplished with only “safe” decisions. Finally, the recipients were encouraged to focus on the impact they could make while alive and actively involved in the operations of their foundations, so that they could learn from their mistakes, adapt, and carry the lessons forward.12

These suggestions served as informal guidance for the foundations, including my father’s, the Howard G. Buffett Foundation (HGBF). The ideas my grandfather conveyed were important, especially the last one, which encouraged a sense of purpose and urgency in the foundation’s work. In line with this suggestion, and almost unheard of among foundations, my father had instituted a sunset clause to put his foundation out of business roughly forty years after the 2006 announcement.13 Knowing his foundation will not operate in perpetuity has encouraged my father to take smart risks, to learn as quickly as possible, and to operate in a way that seems to maximize the impact of every dollar the foundation distributes.

I have been very fortunate that my father involved me so closely in his foundation’s work. Over the course of twenty years, I traveled to more than seventy countries—almost all with my father for the work of the foundation—to learn directly from people and communities we visited. I have observed many of the world’s challenges firsthand, and I have witnessed my father’s dedication to being the best steward he can be of the resources his father gave to him. I also have observed that he is as strongly driven by this sense of duty—the effective stewardship of philanthropy—as my grandfather is by his duty to Berkshire’s shareholders. I know of few individuals who exhibit a stronger commitment to their self-described missions, and I have gathered many lifelong insights as a witness to their somewhat parallel approaches in the worlds of finance and philanthropy.

Until 2006, the business operations of the foundation were somewhat limited. HGBF had a relatively small team equivalent to roughly two full-time staff; it distributed about $6 million in grants in 2005.14 Grant making increased almost tenfold by the year following my grandfather’s announcement, to nearly $60 million.15 The influx of funding and increased activity prompted some significant and immediate organizational changes. Almost overnight the foundation’s annual distributions rose dramatically. It added staff capacity to meet an immediate increase in grant making, diligence, operations, and program supervision. It needed additional office space and began exploring new management processes to handle quickening work flows. Most important, it needed to identify additional grantees, high-reward opportunities, and long-term challenges to address, encouraged by the suggestions my grandfather had provided in his gift letter.

A number of programmatic shifts took place between 2005 and 2007 as well. In its early years, a portion of the foundation’s grant making had been funding programs to protect against environmental degradation and to save threatened wildlife species. Many grants were in the form of individual gifts to single organizations, and they were small in scale and in their ability to solve widespread problems due to the limited size of the foundation’s annual grant making budget.

In 2006, my father developed detailed internal position papers on each of the foundation’s main programmatic areas, supported by research, lessons learned from past activities, and input from previous and existing grantees. He also explored a deep analysis of the web of underlying causal relationships, where he saw ways that one problem made another worse. The foundation’s increased giving enabled my father to take a more comprehensive perspective, and new funds focused almost entirely on humanitarian efforts, water conservation, and global food security programs. Perhaps most significant, this widening view led to three main shifts in the organization’s overall operational approach.

First, the foundation began deepening its view of grantees as partners in its overall philanthropic mission, with roles going beyond that of contractors or the recipients of gifts.

Second, to have lasting impact my father decided the foundation needed to work collaboratively with partners and to encourage them to incorporate and prioritize local community ownership of the projects the foundation supported.

Third, the foundation began looking at opportunities to fund larger initiatives or groups of organizations working toward common goals rather than one-off or isolated projects. This allowed the foundation to develop a more robust strategy over time, refocusing its mission and activities on the individuals whose lives it hoped to improve. It also enabled the foundation to better define its target issue areas and look at mitigating root causes of challenges, such as causality between conflict, poverty, and hunger.

Many of the organizational shifts following the increased funding in 2006 subtly mirrored particular operational values that had made Berkshire Hathaway incredibly successful. For instance, in 2007 the foundation launched a $150 million, multiorganization effort called the Global Water Initiative (GWI).16 The goal was to improve water management policies, research, investment, and knowledge resources for sustainable agricultural production and improved food security—mainly in Africa and Latin America.

At the foundation’s invitation, senior managers from leading water nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and other funders came together from around the world to jointly develop a strategy that aimed to be both comprehensive and flexible.17 The organizations the foundation eventually worked with were selected based on their competencies and track record and on their complementary skills and assets for solving the web of problems involved in improving water quality while conserving it as a limited resource. The group found ways for the comparative strengths or experiences of one organization to offset risks created by gaps or shortcomings in another and vice versa.18 The foundation established a portfolio of NGO partners, hoping to unlock value through a belief that their coordinated efforts would be worth more than the sum of their isolated activities.19

Because of HGBF’s increased funding, it was able to develop and finance multiyear implementation plans such as GWI. In doing so, HGBF could take a relatively long-term investment focus, which was in contrast to typical nonprofit sector time horizons that can be as brief as the next round of fund-raising. These new strategies, which were developed in tandem with a variety of stakeholders, prioritized the inclusion of local communities in the design and development of solutions so that they could better assume co-ownership over the philanthropic investments.20 Furthermore, the foundation instilled a great deal of trust and autonomy in the leadership at these organizations. By recognizing that these managers would be the stewards of the philanthropic capital, HGBF sought ways to incentivize them to work together to accomplish everyone’s shared goals rather than to approach fund-raising with a zero-sum mentality.

Although this may not initially seem analogous to Berkshire’s value investing style, my father was following a playbook similar to that of his father. The key ingredients were there but were applied to philanthropy rather than business, using an investment approach focused on the long-term that attempted to unlock hidden or intrinsic value through its allocation strategy. More important is how HGBF’s methodology mirrored a broad application of many of the management principles that made Berkshire Hathaway so successful through its operating strategy.

Consider the following key elements of Berkshire’s operational paradigm that have led to such successes.

1. Berkshire is a partnership of diverse yet complementary businesses that collectively contribute to its creation of long-term value.21

In other words, Berkshire’s operating process expands and aligns its subsidiaries’ efforts in a mutually collaborative manner, often drawing on comparative strengths.

2. Berkshire’s team is a network of decentralized managers who operate its independent subsidiaries—they comprise a range of varied strengths but are aligned toward shared goals.22

In this way, Berkshire invests in and empowers one of its most important assets—its people, the managers operating its businesses—and supports their collective ability to lead and succeed.23

3. Berkshire incorporates shareholders as owner-partners of the company—not just investors—by building their trust and prioritizing their best interests.24

The company’s operating manual invites investors to stay with it forever, just as if they “owned a farm or…house in partnership with members of [their] family.” This concept of permanent community, or place-based co-ownership, is apparent in the unique relationship between the company and its shareholders.25

4. Berkshire draws from a combined set of financial tools, assets, and liabilities that diversifies risk and increases its balance sheet over time.26

In other words, Berkshire blends different types of financial capital—including equity, cash on hand, deferred taxes, insurance float, debt, and so on—spanning a versatile and coordinated portfolio of investments.

5. Berkshire identifies and invests in opportunities with comparatively high intrinsic value (especially in comparison to book value) that are in line with the company’s principles.27

Through this approach, the company predicts the relative future performance of a given set of investments and allocates capital based on its priorities and goals.

This outline provides a basic description of Berkshire’s value investing approach through five aspects of its management methodology. These five elements—process, people, place, portfolio, and performance—are also the basis for the framework I call social value investing.

In the coming chapters, we explore ways in which this framework combines the principles of value investing with the intentions and goals of philanthropy and the public sector to create partnerships that provide a meaningful and positive impact for society. In the remainder of this chapter, I briefly explore how the social value investing framework evolved over the course of a number of distinct phases.

The five elements of social value investing.

THE ORIGINS OF SOCIAL VALUE INVESTING

My early thinking about social value investing began while attending Columbia University’s master’s program in Public Policy and Administration, studying under the tutelage of my coauthor, Bill Eimicke. Bill and I spent many hours outside of class discussing management theory, interesting cases such as Central Park, and ways that successful management practices from one type of organization could be modified and adapted to other organizations. Although we did not know it at the time, these conversations informed the early development of the social value investing framework.

I arrived at Columbia more than fifty years after my grandfather had attended and almost immediately after his 2006 announcement. Around this time, philanthropies and NGOs alike were grappling with the challenges of how to increase the scale of their impact and how to measure that impact and determine, in quantifiable terms, how effectively donor’s dollars were being used.28 During my master’s program, I worked on a customized, flexible, and expandable analytical framework for defining and comparing the potential social impact of philanthropic grants. Much has changed since its first iteration as I have refined the tool into what is now the Impact Balance Sheet.

The Impact Balance Sheet provides a uniform way to analyze and compare the expected quality of impact that a project or program may deliver, based on a customized set of constraints and preferences. In one sense, the framework provides insights into the potential intrinsic social value of a program, defined by one’s intended goals. In addition, the underlying principles and analytical structure of this tool helps partners define success in a common language using similar methods of measurement. This enables partners with diverse goals to better plan activities, allocate resources, and improve their impact-related performance. This tool is part of the social value investing measurement methodology and is incorporated into a new formula I call Impact Rate of Return (see chapter 8).29

Living in New York City while pursuing my degree provided me with an opportunity to work with and learn about a wide range of organizations spanning the public, private, and philanthropic sectors. Many of the leaders I worked with seemed to be asking a common question, “How can we combine our resources with other organizations to better accomplish shared goals?”

One individual I worked with was Amir Dossal, then the executive director of the United Nations Office for Partnerships (UNOP).30 Dossal and I had connected through a somewhat chance meeting, and he invited me to join his office as a partnership advisor. The UN Secretary General established the UNOP to serve as a gateway for partnerships and to leverage external resources in support of the UN’s global agenda.31 Among other programs, it oversaw the United Nations Fund for International Partnerships and facilitated cross-sector collaboration in support of the $1 billion gift Ted Turner announced in 1997.32 Dossal and his team looked for ways to combine private sector programs, philanthropic capital, the assets of the UN family, and other government donors toward coordinated and aligned objectives. This type of blending of assets from different organizations and sectors resulted in a coordinated portfolio approach.33 (We discuss this aspect of social value investing in chapter 7.)

DESIGNING A PARTNERSHIP BUILDING PROCESS

Many aspects of the process component of social value investing were expanded and formalized during my work in the federal government following the 2008 presidential election. This may seem oxymoronic because the U.S. federal government is usually regarded as an ineffective collaborator—frequently mired down in rules or regulations preventing it from successfully working across organizations and sectors. However, the financial crisis of 2008 sent a clear message to the incoming presidential administration: be prepared to do more with less and involve a broad spectrum of stakeholders. From the outset of his election, President Barack Obama made it a priority for his administration to find new ways for the government to collaborate with public and private organizations alike in solving the country’s challenges.34

This collaborative mind-set started in the very early days of the Obama administration. Following the 2008 presidential campaign, I joined the presidential transition team’s efforts to help prepare for the government’s turnover and develop the president’s 100-day agenda. The transition team was also charged with authoring innovative and inclusive strategies to respond quickly to the Great Recession, even as it was still unfolding. This ultimately contributed to the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, known as “the Stimulus,” which was signed into law less than one month after President Obama took office.35 Woven throughout these policies was a common thread: the importance of engaging in meaningful cross-sector partnerships across the administration and across the country.

Also during this time, the transition team’s Technology, Innovation, and Government Reform Policy Working Group (TIGR) was charged with developing specific ways in which the White House and its executive departments could better partner with nonprofits, foundations, philanthropists, corporations, and social enterprises of all kinds and sizes.36 To advance the president’s Innovation Agenda, this group established a set of objectives that would eventually make up the priorities for the only newly created office in the White House—the Office of Social Innovation and Civic Participation (SICP)—where I served as a policy advisor under Sonal Shah, its inaugural director.37

During the first eighteen months of the administration, SICP developed a variety of programs and government-wide initiatives prioritizing and relying on meaningful partnerships for success. For example, SICP established the government’s first Social Innovation Fund, created to finance partnerships in support of the administration’s key domestic policy priority areas.38 The office also hosted a series of Energy Innovation Conferences, bringing together dozens of organizations and agencies, where the Department of Energy announced $60 million in new funding for Small Business Clean Energy Innovation projects.39 Further, SICP launched a Next Generation Leadership initiative focused on fostering collaborative partnerships between millennial leaders all across the country.40 Internal to the Executive Office of the President, SICP advanced the president’s partnership agenda by establishing an interagency working group on the subject, titled Partnerships for Innovation. This group shared information across fifteen executive branch agencies to develop new cross-sector partnerships and innovation strategies to enhance collaboration between the White House, federal departments, agencies, for-profits, nonprofits, and foundations. Through my role in these initiatives, I assembled relevant knowledge and guidance from a variety of perspectives and gathered lessons learned regarding the development of effective cross-sector partnerships.

With key input from agencies such as the State Department and the Small Business Administration, the SICP team codified these new practices and lessons into the president’s internal policy framework for engaging the executive branch in a coordinated, cross-sector partnership strategy. This effort and the work it led to inspired many of the principles, definitions, and models related to partnership development that are reflected in my social value investing framework. We explore some of these principles in chapter 4, which outlines the process by which partners create a comprehensive strategy for addressing complex challenges.

DEVELOPING PLACE-BASED OWNERSHIP STRATEGIES

Following my work in the White House, I joined a unique economic development team based in the Office of the Secretary at the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD). Much of DoD’s efforts at the time focused on the conflict areas of Afghanistan and Iraq, and this team’s mission was to promote diverse economic stability operations in regions across both countries.41

As the head of the team’s agricultural development program, I further refined the principles of the social value investing framework. One focus area was creation of community-led economic development strategies in Afghanistan’s western Herat region. Following the food price crisis of 2007–2008, the government prioritized investment in Afghanistan’s agricultural systems as a direct way to alleviate unemployment and hunger and promote security and stability in the region.42

The agricultural development team worked hand in hand with each of the local communities engaged in the initiative and with their shuras (which are similar to community councils). We established or supported creation of women-owned local enterprises linked to new farmer cooperatives developed in the region. We engaged the local city and provincial governments to garner their support and to develop policies and resources needed for the initiatives over the long term.43 Ultimately, every program dollar expended, capital project constructed, and piece of equipment procured was in consultation with and led by local guidance. Herat University, farmer cooperatives, and local NGOs and associations took legal ownership over our investments, with the goal of transforming “beneficiaries” into true shareholders of the program’s outcomes. The cross-sector partnerships we developed among the DoD, external funders, local communities and NGOs, and universities also put in place a permanent training infrastructure and knowledge base required for the long-term success of the program.44 This led to important capacity development and infrastructure for the agricultural sector across the region.

The third element of the social value investing framework—supporting local community ownership in the places where partners are working and investing—is discussed in detail in chapter 8. We dive into this subject by establishing cooperative principles for developing place-based strategies so that organizations and communities can coinvest their resources toward an intended outcome. A set of best practices for sharing success across organizations is outlined in the chapter, as well as ways to balance decision-making authority between funders, implementers, and local communities. Furthermore, we discuss how partners can plan and sequence activities strategically and build collaborative evaluation models for allocating shared resources.

DEPLOYING NEW INVESTMENT IN PEOPLE

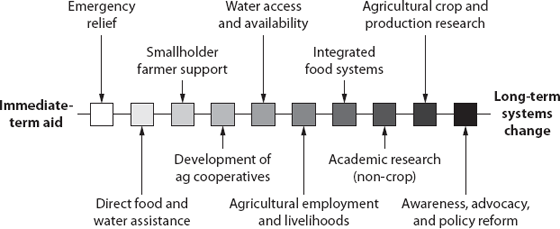

After my time at the Defense Department, I began serving a two-year term as the Executive Director of HGBF. During this time, the organization went through a brief strategic planning process as I worked to incorporate principles of social value investing into its programming and operations. The foundation’s team discussed ways it could restructure objectives into a more comprehensive approach and developed what we called our Global Food Security Spectrum to provide thematic guidance for programs (figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 The Howard G. Buffett Foundation’s Global Food Security Spectrum illustrates a range of interconnected activities and programs falling within the organization’s mission.

The left end of this range represented immediate-term relief and aid, and the right end represented long-term systems change. Various types of activities or initiatives filled the spaces in between, such as water resource management or the development of integrated food systems. The team ordered these activities based on longevity of program impact, complexity, and the foundation’s experience with the given type of work.

At the far right end of the range we listed activities such as awareness and advocacy, topics the foundation had been exploring with increasing frequency. We observed that large-scale impact requires the coordinated efforts of numerous funders, the government, influencers, and support from the general public. In addition, we considered ways to elevate the visibility of issues the foundation had prioritized.45

Also during this period, we spent a great deal of time reflecting on the foundation’s work from the past decade and the experiences we had learned from the most. We eventually decided that these experiences could serve to drive public awareness on global hunger challenges, and the foundation began working on a book to chronicle insights and lessons learned about the complex problems our world was facing.

My father and I wrote 40 Chances: Finding Hope in a Hungry World to create a conversation on what was and was not working, particularly in the development and aid community. This was an opportunity to share our observations and our failures over the past decade, but we also hoped it would inspire increased public engagement in local and global issues that could encourage important policy changes in the United States and abroad. Also, this presented an opportunity for me to discuss some aspects of the social value investing approach.46

As we organized the book’s chapters, it became clear that we were telling the stories of people from around the world where the foundation had made major investments. These people were the real heroes. Throughout the years, we had built a network of successful “managers” who were dedicated to achieving goals shared by the foundation and who put their missions and their altruistic hopes ahead of themselves.

One standout example is Kofi Boa, a Ghanaian farmer and environmental conservationist who has dedicated his life to advancing Africa’s sustainable agricultural practices. Boa is a soft-spoken but tireless advocate for improved production techniques, and the foundation recently partnered with him to launch Africa’s first Center for No-Till Agriculture. Because of our trust in Boa, we structured a unique cross-sector partnership designed to improve the productivity and sustainability of smallholder farmers through conservation-based techniques—first in Ghana, and later, we hoped, across much of Africa.47

The objectives of the partnership with Boa are complex because the agricultural issues it addresses are multifaceted and tough to solve. For example, the World Bank estimates that nearly 80 percent of the world’s poor live in areas where agriculture is the primary economic activity—areas that often need investment throughout the agricultural value chain.48 However, if done well, these investments can be very fruitful. The World Bank approximates that agricultural sector development is up to 4 times more effective at lifting the income of poor individuals than investments in any other sector.49 Moreover, this effectiveness jumps to as much as 11 times more effective for sub-Saharan Africa.50

Working closely with Boa and the smallholder farmers in his community, HGBF orchestrated partners to develop a suite of context appropriate tools (such as a new model of small-scale, conservation-based planters manufactured by John Deere), resources (such as customized seed and cover crop recommendations based on soil types and topography), and agriculture-sector-related infrastructure improvements. The program has taken work that goes beyond what many traditional development projects require, but it has endured because of HGBF’s partners, the collective group’s commitment, and especially Boa, who understands that the success and scalability of this partnership could have far-reaching implications.51

Boa and his team lead all aspects of the program’s design and the center’s programs and operations, only seeking input from the foundation as needed. Another central aspect of this partnership is to reach and influence farmer behavior in meaningful but everyday ways to encourage them to adopt conservation-based practices through in-person workshops and radio broadcasts. Because of Boa’s reputation with farmers throughout Ghana, he is uniquely positioned to capture their attention and speak with authority on the subject. Boa’s work and his personal story is told in chapter 35 of 40 Chances: Finding Hope in a Hungry World.

In 2012, halfway through my time at the foundation, there was yet another announcement—the funding provided from my grandfather’s 2006 gift to his children would be doubled.52 My father began looking for opportunities to further increase his investments and expand his impact, and for new partners to help deploy the capital. The foundation’s reliance on its managers became more important than ever. By 2014, the foundation’s total giving increased to more than $150 million per year, and its capacity to take on new and exciting challenges increased as well.53

This example illustrates the importance of human capital and how leaders can invest in and empower the people both on their staff and in a partnership. In chapter 6 we discuss a leader’s role in working effectively across decentralized partners and teams. We also discuss the importance of diverse leadership qualities and of understanding the underlying emotional and intellectual influences that motivate teams. Finally, we discuss ways that leaders can inspire their team’s energy and momentum throughout the life cycle of a partnership.

THE SOCIAL VALUE INVESTING FRAMEWORK

The coming chapters further illustrate the social value investing framework, and how it reflects principles from the value investing approach. This adaptation is apparent at the most basic level of the framework, as outlined in the process / people / place / portfolio / performance paradigm. At the same time, many of the parallels vary significantly due to the obvious nature of the adaptation—it is a translation of principles from a purely financial construct for building monetary value to one providing guidance on effective ways to collaborate for the creation of social value.

The framework sets out a series of preconditions for planning and building effective partnerships between organizations of all types. However, it is not a comprehensive list, nor will all aspects of the approach apply to every partnership. This is a generalized framework on purpose, and the principles outlined are broad so that they are widely applicable. The cases discussed and their accompanying course companions and video documentaries demonstrate how these lessons apply, but the principles and observations are not the end result.54 Instead, we hope they provide a starting point for others to expand and improve on our ideas, to establish sets of common goals, to create a more inclusive and community-driven vision for the future, and to begin exploring new and more effective ways for investing in social value.