HOWARD W. BUFFETT AND WILLIAM B. EIMICKE

Cross-sector partnerships are based on the idea that more is accomplished when organizations collaborate and share in their success. These partnerships are not only important but will be necessary if society is to overcome its most complex challenges.1 Some of these partnerships are already taking place, and we looked at a number of them in this book—Digital India, place-based development in Afghanistan, and emergency response in New York City, to name a few.

We wrote this book because we believe the world can be much improved from where it is today. Not only can we do better—we must do better. We must set aside individualistic and short-term thinking and work together to realize a world that is more equitable, inclusive, and responsible to the needs of all. Leaders of organizations who think and act in isolation are constrained in what they can accomplish over the long term and ultimately, may end up doing more harm to society than good.

We must also rethink our assumptions about the role of organizations in society. We generally expect too much from government, do not hold the private sector accountable enough for its negative externalities, and rely too heavily on the social sector to close the gap.2 We know there are opportunities to improve how society approaches collective problem solving in the world.3 We also know that partnerships between public, private, and philanthropic organizations are better equipped to act upon society’s interests than any organization can on its own.4

As we have detailed in the preceding chapters, we envision a strategy for cross-sector partnerships based on a framework called social value investing. This framework is inspired by one of history’s most successful investment paradigms—value investing—developed by Columbia University professors Benjamin Graham and David Dodd in the 1920s.5 As Columbia University professors ourselves, we find special meaning in building from these and other past successes.

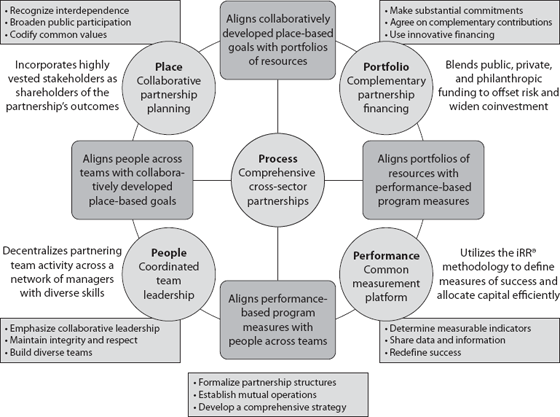

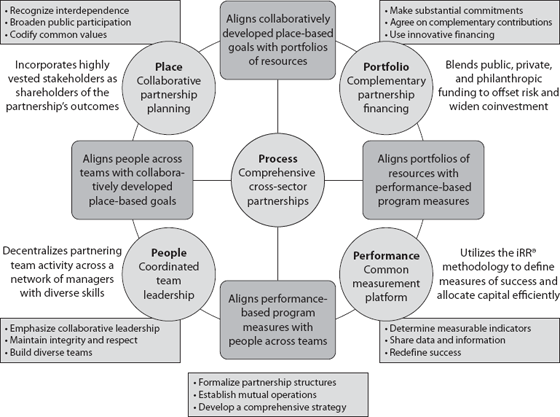

Similar to value investing, social value investing focuses on a long-term time horizon. It presents a strategy for unlocking intrinsic social value for individuals, communities, and organizations, with a framework spanning five elements: process, people, place, portfolio, and performance. We have provided case studies illustrating how partnerships with similar approaches—most developed independent of our framework—are improving conditions around the world. Our hope is that future partnerships will benefit from our analysis of these successful collaborations and improve on the framework. Although the work has just begun, our experience tells us there is good reason to be optimistic.

Digital India, for example, is already a positive force in the lives of millions of Indians. Its implementation rests on a process that starts with the national government, works through the nation’s leading for-profit technology companies, and is driven by local entrepreneurs.6 These entrepreneurs operate access points to a system of services providing government benefits, medical care, banking, and insurance. Citizens also can access secure electronic records of important documents such as driver’s licenses and birth certificates. Led by a strong prime minister, the process has evolved to deal with legal, bureaucratic, political, and technological challenges. Digital India continues because it delivers valuable benefits to the country’s citizens, whether they are rich or poor, urban or rural, and therefore it retains popular support.

Our Central Park and High Line cases illustrate how, with the right focus on people, social sector organizations can take the lead in partnering with government to transform public spaces. Betsy Rogers, Doug Blonsky, and Ira Millstein provided critical leadership for the Central Park Conservancy.7 City Parks Department leaders, particularly Gordon Davis, Adrian Benepe, and Mitchell Silver, as well as five strongly supportive mayors (Koch, Dinkins, Giuliani, Bloomberg, and de Blasio), illustrated the important enabling role of the public sector. And an army of dedicated and generous donors, including John A. Paulson and Richard Gilder, saved Central Park’s budget, leading to a model for twenty-first-century urban spaces.8 Collaborative experts who can navigate across the organizational boundaries of all three sectors are critical to establishing effective partnerships.

The public sector was key in rebuilding parts of Afghanistan, but so were universities and private companies. Without a strong government peace-keeping presence, it would have been impossible to do much at all. In our view, the essential ingredient to the measured success in these projects was a place-based strategy, created in close collaboration with farming communities such as the Rabāţ-e Pīrzādah village. Local entrepreneurs including Zainab Sufizada helped design facilities and operating processes so that the resources and expertise from the other partners could make a significant, positive, and lasting impact on the ground.9

In Brazil, a consortium of many of the most successful corporate leaders in the nation came together to establish Comunitas, a nonprofit dedicated to restoring the public’s faith in the efficacy and honesty of local government. Under the leadership of its board and Comunitas director and president Regina Siqueira, Juntos used a portfolio approach, blending public, private, and philanthropic investment into programs to improve municipal services.10 This allowed local governments to acquire the best financial, technology, architecture, and engineering consultants in the country, and at no cost to taxpayers. The program also created a platform that illuminated the activities of local government to citizens and gave those citizens significant influence on the priorities of their locality.

We saw how New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg based his administration on performance management. This data-driven approach helped New York City’s emergency response system, and by 2016 it had the fewest fire-related deaths in its history.11 Key indicators of public health, environmental quality, and economic development also improved significantly during Bloomberg’s twelve years in office. Similar performance measures led the city to experiment with new methods of preventing recidivism among recently released inmates from Rikers Island. Overall, this case illustrated the positive effects of orienting programs in a cross-sector partnership around performance-based measurements.

Finally, our case study profiling the development of partnerships for the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro outlines some risks and consequences of not planning collaboratively. Among other problems were leadership challenges and a lack of transparency and stakeholder inclusion. This fueled an environment ripe for corruption and led to anger on the part of local residents.12 Although the games themselves succeeded, we believe the partnership process would have benefited significantly from following many of the key elements of the social value investing framework, including the partnership checklist outlined in the next section.

THE SOCIAL VALUE INVESTING PARTNERSHIP CHECKLIST

It is too soon to tell how successful some of these high-risk but potentially high-reward partnership initiatives will be, but we can analyze them all through the social value investing framework. We recognize that partnerships are not the easiest organizational structure to accomplish critical social objectives. It can be hard enough to get things done within one organization, let alone two or more. Succeeding by coordinating across multiple parties, often from different sectors, is complicated.13 Therefore, as organizations develop new cross-sector partnerships, we recommend that partners consider the following checklist.14 Here we categorize important lessons and takeaways from each of the five elements of the social value investing framework.

Process: Successful cross-sector partnerships comprise diverse yet complementary organizations that collectively contribute to the creation of long-term value. Through a well-structured operating process, partners expand and align their efforts and draw on comparative strengths.

1. Formalize Partnership Structures

The management compatibility challenges of cross-sector partnerships can be diminished through a formal partnership structure.15 Organizations must work from common definitions and use formal agreements such as letters of intent or memorandums of understanding (as discussed in chapter 4). Still there may be downsides or difficulties in formalizing a partnership, which we saw in the Central Park case (chapter 5). New York City Parks Commissioner Gordon Davis and Central Park Conservancy CEO and Central Park Administrator Betsy Rogers recognized early on that they were operating a virtual cross-sector partnership. But they also believed that a formal partnership for a large public park was an idea ahead of its time in the late 1970s. They moved slowly but methodically toward that objective and, in 1998, the time was right. They signed a formal eight-year partnership agreement. The partnership contract was renewed in 2006 for a second eight years, and again in 2013 for what will be at least twenty-four years of partnership operation under a formal contract.

2. Establish Mutual Operations

Successful partnerships typically establish and synchronize mutual operations to guide collaborative programs. For example, partners may create a project charter, develop a work plan, or follow a coordinated communications strategy.16 In the case of Digital India (chapter 3), cooperative yet distributed program delivery allowed the government, Apollo Telemedicine, the common service centers, and village-level entrepreneurs to execute joint work efficiently. In the case of preventing fires (chapter 11), the IBM team colocated at FDNY headquarters with the FDNY project team.17 They spent significant time in firehouses throughout the city and rode with firefighter inspection teams so they could fully understand fire inspection procedures before the partners jointly designed a new, more effective set of them. Through understanding and the establishment of new procedures, FDNY, IBM, and others were better equipped to develop the partnership’s long-term strategy.

3. Develop a Comprehensive Strategy

Addressing a complex challenge requires a comprehensive strategy that enables and benefits from the cooperative and coordinated activities of a group of partners.18 This was evident in many of our partnership examples, and especially in Afghanistan (chapter 7). In this case, partners invested considerable time researching and analyzing their program strategy’s complete value chain throughout the Herat area. Alongside community stakeholders, they developed a thorough logic model for the resources and activities required to address economic and social gaps and to support the outcomes all partners desired. The funders relied on formal agreements with locally focused NGOs and with Herat University and put operating procedures in place for coordinating program development and resource deployment between the communities.

People: Cross-sector partnerships thrive through a network of decentralized leaders and managers who operate independent programs and organizations. These leaders and their teams comprise a range of varied strengths but are aligned toward shared goals. By focusing on and empowering the people involved, partnering organizations can support their teams’ collective ability to lead and succeed.

4. Emphasize Collaborative Leadership

To achieve success, partnerships must emphasize collaborative leadership between teams.19 Experience tells us that management by committee seldom works. At the same time, it is virtually impossible to sustain success by ordering people around, many of whom may not even work for you. In 1999, New York City was ready to tear down the elevated train tracks of the High Line (chapter 5) when the local community, led by residents Joshua David and Robert Hammond, came together with a better idea.20 Partnering with nationally known real estate expert John Alschuler (who later became the organization’s board chair), Friends of the High Line reached out and learned from Betsy Rogers’s success at Central Park. They also built a strong partnership with key members of the Bloomberg administration, particularly with the city planning commissioner, the parks commissioner, the deputy mayor, and Mayor Bloomberg himself. Early on they were able to engage major philanthropists to support the effort, and they worked collaboratively with many others to build the High Line. It is now one of the most visited and admired urban parks in the world, freely accessible to anyone, and primarily operated with private funds.21

In a starkly different example, we learned that the absence of collaborative leadership can have seriously detrimental effects on the results of a partnership. In the 2016 Olympics case (chapter 13), the failure of government officials to collaboratively engage partners and the community was a contributing factor to the significant problems and corruption that surfaced after the games concluded.22

5. Maintain Integrity and Respect

Partners may come from different sectors, and may be from different parts of the world, with different histories and cultures. They may be small or new organizations, or ones that are well known, large, and powerful. We see excellent examples of partners overcoming these differences in the High Line case, in which a new community-based organization (Friends of the High Line) partnered with the very large and powerful Bloomberg administration (chapter 5). This was also reflected in how participants interacted between local communities, NGOs, and the international partners in the Afghanistan case (chapter 7). Partners must act with integrity and treat each other with respect according to widely accepted social norms, no matter with whom they are partnered.23 In the case of the Rio Olympics, however, it appears that the mayor’s administration failed to do this. They did not engage community-level partners adequately enough in the planning phases of development. The mayor also dismissed critics and public opponents in the face of sometimes violent street protests, which took place as the implementation process moved forward.24

6. Build Diverse Teams

Successful partnerships rely on varying sets of leadership skills and experiences across organizations and the people running them.25 Leaders must build diverse teams that account for the skills-based capital necessary for achieving the partnership’s goals. In the Juntos case in Brazil (chapter 9), the Comunitas partnership did more than bring together a portfolio of financial capital. It also built a network of accomplished and capable leaders from organizations across sectors to meet its objectives. Only through this inclusive approach could the partnership draw on the combined knowledge and expertise of its participants for the broad array of necessary programs. This way, partnering teams improved local government programs, reformed financial practices, increased public outreach, conducted economic development, and expanded critical community services.

Place: By employing a place-based strategy, cross-sector partnerships incorporate stakeholders as true shareholders rather than just beneficiaries of a partnership’s investment. This typically requires time and effort to build trust and requires intentionality around prioritizing stakeholders’ best interests. Working collaboratively with a sense of permanent community, what we call place-based co-ownership, reinforces important long-term relationships between partners.

7. Recognize Interdependence

Partnership strategies that are effectively place-based bring together many different participants comprehensively, with goals that rely on unique partner strengths, attributes, and contributions.26 To support often difficult and lengthy partnership engagements, partners benefit from mutual reliance established by a commitment to work together. Before agreeing to formalize a partnership, partners should decide individually and agree collectively that they are interdependent—they need each other to achieve the partnership’s shared goals.27 This recognition of and reliance on interdependence was clearly true in the Afghanistan case (chapter 7). Partners depended on the actions of one another—from the philanthropic and NGO investments, to the commitments by local entrepreneurs, to the academic and private sector expertise, and even to the security provided by the coalition forces—all of which were essential for the projects to be feasible and successful.

8. Broaden Public Participation

By definition, comprehensive, place-based partnership strategies require broad public participation to succeed. More and more frequently, partnerships are using technology and communication platforms to enable civic engagement, as we saw in the Juntos case.28 The Comunitas initiatives were transformative in large part because they invited citizens to participate in setting the Campinas budget priorities and in Curitiba’s strategic planning process (chapter 9). Public participation was similarly important for Digital India and the Telemedicine program (chapter 3). In some cases, participation platforms can serve multiple purposes, as we saw in New York City’s partnerships to transform public safety through cutting edge technology and open data (chapter 11). In contrast, being unwilling to give local communities enough voice in planning and implementation can be damaging. This was the case with the Rio Olympics projects; lack of public engagement contributed to increasing opposition and protests throughout project development. From an implementation standpoint alone, such public opposition can delay project construction, increase costs, or even result in a partnership’s cancellation.29

9. Codify Common Values

Cross-sector partnerships typically involve a range of organizations and stakeholders, all of whom must align their missions, program time lines, and priorities in collaboration. Discovering and codifying common values between partners is necessary if they are to understand organizational norms and establish operational expectations.30 Partners may choose to establish a set of cooperative principles and measures for mutual accountability that guide the partnership’s ongoing collaboration. Participants will also benefit from a common framework to analyze program options and support coordinated decision making. This was evident in many of our cases, including New York City’s parks. In developing the High Line collaboration, for example (chapter 5), common values helped partners work past the cumbersome process of five separate sign-offs for decisions of all sizes. As a result of their mutual trust, they broke ground and began construction for the project at the same time they were finalizing the official partnership agreement.

Portfolio: Cross-sector partnerships can draw from and combine various financial tools and investments. This enables partners to diversify risk and expand the pool of capital available to carry out the partnership’s programs and deliver its outcomes. By blending financial capital from different sources, including philanthropic capital (which can take significant risks),31 programs can be funded by a versatile and coordinated portfolio of investments.

10. Make Substantial Commitments

Organizations must make substantial commitments to the partnership, not just at the beginning of the effort but throughout its duration.32 We saw this in the economic development projects in Herat Province, Afghanistan (chapter 7). The U.S. government made significant up-front investments in research, data discovery, and construction. The Afghan provincial government invested in electricity infrastructure to better enable new agricultural processing capacity, and a philanthropic partner financed irrigation equipment. Such up-front investments by partners typically reflect broad consensus that the projects are important and worthwhile. We also saw this in the Juntos case in Brazil (chapter 9), where the Comunitas group provided up-front investments for financial, architectural, and technology consultants. Local governments provided human capital and infrastructure, the federal government supplied annual intergovernmental revenue sharing, and the technological advancements gave residents a voice in city decisions.

11. Agree on Complementary Contributions

As partners consider options for program financing, it is essential that they develop a coinvestment strategy agreed to and based on complementary contributions, not an effort to disguise or mitigate individual weaknesses or a lack of funding.33 This allows partners to share both risk and potential reward, and to leverage their assets, financial or otherwise. As we discussed in chapter 4, such collaborations go beyond typical fee-for-service or product procurement between the partnering groups, with contributed assets that may have both tangible and intrinsic value. We saw this in the performance case (chapter 11), where FDNY and IBM each invested organizational resources and time, and provided access to their unique systems, operations, and capabilities. This was also the case with Comunitas (chapter 9) and the cities of Campinas, Pelotas, and Curitiba, where the partners combined financial capital, including private and philanthropic funding, to open program opportunities not otherwise possible.

12. Use Innovative Financing

Innovative financing can be the cornerstone of a cross-sector partnership. This is especially true for partnerships that develop and deploy new, untested, or creative methods for addressing challenging problems.34 In such cases, partners can access and leverage private-sector financing and direct it toward public good. We see this with the relatively new financial structure called a social impact bond (SIB), which brings together and takes advantage of the respective strengths and flexibility of public, private, and philanthropic sector partners. Partnerships can benefit from risk offsetting through program-related investments (PRIs), which are well-established but underused opportunities for incentivizing inventive collaboration (SIBs and PRIs are both outlined in chapter 10). In many respects, combining a broad suite of financial tools can result in an expanded network of organizations working toward common goals, and with better alignment of financial and social outcomes.

Performance: Partners must work together to identify and select collaborative programs with comparatively high intrinsic values—programs that are in line with partners’ principles and the partnership’s overall objectives. By predicting the relative performance of a given set of program options using the Impact Rate of Return formula, partners can allocate capital based on specific priorities and goals.

13. Determine Measurable Indicators

Without clearly defined and mutually accepted measurable indicators, partners cannot know whether they have succeeded, much less determine whether programs are on track or performing well.35 Former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg led the recovery of New York City after September 11, 2001, anchored on a consensus of the most accurate metrics of success, a relentless quest for more and better data, and the development and refinement of operational strategies around those factors. In public safety and emergency response, as discussed in chapter 11, Bloomberg-era partnerships (and previously existing programs) relied heavily on transparent, well-defined, and generally accepted performance measures that were agreed to by all partners. As we learned with the Impact Rate of Return formula (chapter 12), one of the first steps in customizing the iRR measurement platform is determining the partnership’s Key Impact Indicators. Equally important is determining the formula’s specific metrics that define the partnership’s quality of impact (see the Impact Balance Sheet tool outlined in chapter 8).

14. Share Data and Information

To measure progress against established indicators, partners must share data and information across organizational boundaries.36 This is not natural for competitive organizations, particularly because for-profit businesses are accustomed to aggressively hiding trade secrets, strategy, and proprietary data. But such sources of protected information may not be required for a partnership’s performance measurement and monitoring. In some cases, information-sharing is a main purpose of the partnership, as it was in the case of Digital India (chapter 3). In other situations, it is simply a matter of making otherwise public data more readily accessible or searchable. In New York City, Mayor Bloomberg put virtually all of the important information and performance measures for their partnerships on the city’s open data page,37 allowing others to leverage the value of that data freely (see chapter 11).38

15. Redefine Success

The hallmark of the Impact Rate of Return formula is that it provides a measurement framework for translating a partnership’s diverse objectives into a common language (see chapter 12). Simply stated, it allows many different partners to come together and redefine success around their mutually shared goals. The formula predicts the social impact performance of a given project and combines important measureable indicators with program-related data into a platform for partners to make more informed decisions about capital allocation. All partners, including individual and community stakeholders, should participate in determining what aspects or qualities of impact will guide program evaluation (as discussed in chapter 8). As a result, the partnership’s measures of success will be more inclusive and allow for solutions that are more effective over the long term.

This fifteen-point checklist covers many of the most important aspects of cross-sector partnership development and management as discussed throughout the book. These points represent lessons and observations from the successful cases we present and analyze. Furthermore, we believe this list will be useful to organizations as they prepare and implement new partnerships—especially when combined with a sense of optimism that the goals are achievable and will result in better outcomes for stakeholders and society.

WHY WE ARE OPTIMISTIC

Chapter 1 documents the long and evolving history of collaboration between sectors, including the expansive role of large-scale public-private partnerships during the twentieth century. A World Bank study of recent public-private partnerships found that they have been on the rise for decades, exist in more than 130 countries, and account for more than 15 percent of overall infrastructure development.39 The report indicates that over two-thirds of the projects studied (more than a hundred) achieved their development outcomes. The evaluators of these projects identified the need for, and the significant potential benefit of, more public works partnerships in the future to improve infrastructure and promote economic growth.40

Using partnerships to develop and implement new solutions to complex social, economic, and environmental policy problems is different and more difficult, however, particularly because we are only beginning to establish accurate and reliable measures of social impact.41 As Peter Drucker often said, you cannot manage effectively unless you are clear on what you are trying to accomplish and can measure your progress toward achieving your goals.42 We have made great progress in measuring the financial impact of improved management practices, but we can and should judge the success of all organizations, no matter the sector, beyond their mission statement and financial performance.43 We should also evaluate whether they harm or improve their local communities, as well as society as a whole.44 We are already seeing shifts to this effect, and we believe new management and measurement standards may eventually lead to marked improvements in how financial assets are directed.45 For example, imagine unlocking the value of many trillions of dollars held in endowments, retirement accounts, sovereign wealth funds, and private investments by deploying them not just for financial return but also for measurably improving our society.46

BUILDING ON MOMENTUM

We mentioned the work of economist Steven Radelet in the introduction. Radelet argues that we are in the midst of the greatest improvement in the lives of the world’s poor, measured by reduced poverty, increased incomes, improvement in health care, fewer wars and conflicts, and the spread of democracy.47 Although economic conditions for the poor have improved substantially, society continues to grapple with growing global inequality.48 Fortunately, we can take steps to address this while also accelerating economic growth. As Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz writes, “policies are available that would simultaneously increase growth and equality—creating a shared prosperity.”49 Stiglitz recommends a set of policies, including ones to reach full employment, at least in part by increasing public investments in infrastructure, education, innovation, and the environment. He writes that such government “investments will expand the economy and make private investments even more attractive.”50 Historically, he notes, periods of high productivity growth are strongly related to public-sector investment.51 As we argue throughout this book, partnerships can be an extremely effective vehicle for implementing this type of inequality-reducing and pro-growth strategy.

A TIME FOR MORE EFFECTIVE PARTNERSHIPS

Cross-sector partnerships—especially those that share the principles of social value investing—are not just a good idea, they are essential for overcoming society’s most critical challenges.52 To succeed, we need groups of all kinds to come together, share their learning, and promote best practices for a partnership management and delivery system that maximizes positive social impact. Peter Drucker was right when he observed that leadership and management contribute as much or more to progress as technological innovation does.53

Such management, though, must be both effective and strategic, and it must focus on goals that improve society—goals that promote a safe, healthy, prosperous, and thriving world for everyone. Idealistic as this sounds, partnerships based on these principles can lead to more equitable, inclusive, and responsible solutions. But society must be willing to account for the negative externalities of our actions and stop exploitation by certain industries and economic practices.54 By doing so, organizations of all types will be better positioned to serve the important needs of communities everywhere.

We make clear how important measurement is to good management throughout this book. Even more important than how we measure success is how we define success to begin with, because that dramatically affects our intentions, our actions, and our results.

Society is in the process of rediscovering what it means to succeed.55 As that discovery evolves we remain incredibly optimistic, and we ask you to take the observations, frameworks, and lessons in this book, use them for social good, and also improve upon them. We hope this brings together organizations, individuals, and local communities in an inclusive and collective problem solving process to overcome our most intractable challenges. Finally, we hope this work supports transformational change in the way we all collaborate—so that everyone can participate in making the world a far better place.