332 Recovery Hints and Tricks

CHALLENGE EQUALS RECOVERY

_______________

Stroke makes movement difficult. Overcoming the difficulty creates a productive struggle that propels recovery. Recovery begins at the end of your comfort zone. If you eliminate the difficulty, you will not progress toward recovery. This is true with any growth in any aspect of your life:

Challenge = growth.

There is a tendency for some stroke survivors to halt their own progress by only working on what they can. For instance, with their doctor’s blessing, they may go to the gym and do weight training — an action with positive intentions. Once at the gym, however, they work with the muscles that they can control with ease, while ignoring the muscles that pose more of a challenge. All muscles should be strengthened, including the ones that are cooperating. But emphasis should be placed on muscles that are not easy to flex and on movements that provide the most challenge. Challenge is the essence of recovery.

There is a tendency for clinicians and some survivors to focus on what works. What works after stroke? The “good” side! This approach makes sense if you want to get survivors safe, functional, and out the door. Focus on the “good” side may help you become more functional; a good thing to be sure. But focus on the good side will not help you recover. If you want to recover, the stroke makes obvious what to work on: deficits. Stroke survivors will benefit if they concentrate on what they find difficult, not what they find easy. For instance, if you can make a fist but find it hard to open the fisted hand, then work on opening it. The ability to make a fist needs little encouragement. 34But the ability to open the hand is just as important. And, since it is more of a challenge, opening the hand requires more attention. You may say, “If I can’t open my hand, then what’s the use of trying? It won’t open!” If a hand is fisted and hard to open, there are suggestions throughout this book that clinical research has shown to increase movement and improve coordination. See the section The Neuroplastic Model of Spasticity Reduction in Chapter 7, which discusses electrical stimulation, mental practice, mirror therapy, bilateral movement, repetitive practice, and so on.

There are options that give you a fighting chance to regain movements that are difficult and challenging. Embrace them. Ironically, overcoming the challenges left in the wake of a stroke is the best way to recover from stroke! If you eliminate the difficulty and only do what you are now able, you would never relearn how to move better. Challenge drives neuroplasticity. Neuroplasticity drives recovery.

How Is It Done?

Make an honest and accurate account of your strengths and weaknesses. Recovery from stroke involves making an honest assessment and a constant reassessment of what needs work. List the things that need work, and make that list one of the tools for navigating toward recovery. Focus recovery on movements that you find difficult rather than focusing on what is near perfect. It’s a matter of priorities. Activities that are hard provide greater potential for improvement and recovery. Athletes know this. Athletes launch themselves headlong into any challenge that stands between them and winning. Your recovery will accelerate if you honor the challenges that make up the recovery process.

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

Recovery from stroke is hard work. Devoting effort to movements and tasks that are difficult and challenging takes a lot of energy, concentration, and focus. Sometimes the challenge is so difficult that it takes many attempts before the movement or task is accomplished. While this may be safe for some tasks (e.g., attempting to open the hand), it may be dangerous for other tasks (e.g., attempting to walk). Every challenge needs to be undertaken with safety in mind.

Nothing stops recovery like an injury.

35USE WHAT YOU HAVE

_______________

After stroke, survivors typically move in predictable ways. This predictable movement is called “synergistic movement.” Synergistic movement does not allow the joints of the limbs on the “bad” side to move independently. For instance, if a stroke survivor tries to bring their hand forward, their elbow comes up and bends, and the shoulder comes away from the body and elevates. All these movements are linked, and the survivor is unable to isolate any individual movement. This is the way stroke survivors naturally move, and there is nothing wrong with it.

If recovery goes well, synergistic movements will become “unlinked” and individual joints will begin to move more normally. Unfortunately, there is a belief on the part of many therapists that synergistic movement is “bad” movement and should never be done. Therapists believe that using this type of movement will somehow be learned so well that it can’t be unlearned . . . like a bad habit. The notion that the movement available to stroke survivors is harmful has an ironic (and inaccurate) subtext: “The more you move, the worse you’ll get.” This thinking is as misguided as believing that, because babies fall a lot as they learn to walk, they will only learn how to fall and never learn to walk! If you have synergistic movement, use it. This will be a common theme in this book: Movement is good, including synergistic. Movement . . .

• Builds strength

• Reduces spasticity

• Is good for joints

• Increases blood flow to the brain, which then makes learning movement easier

• Bathes the brain in a protein (BDNF) that helps the brain learn faster

How Is It Done?

Many therapists feel the need to intervene, often with a hands-on approach, to make sure stroke survivors are moving “correctly.” But there are several problems with this approach.

1. Recovery should be patient driven. This means that you are responsible for your own recovery. And neuroscience agrees: Only the survivor can drive their own nervous system (brain) toward recovery. No one can do it for them. If a clinician is required to ensure “correct movement,” then the recovery process is taken out of the hands of the stroke survivor. There is simply not enough time (or money!) to have clinicians by your side during the entire recovery process. Clinicians are absolutely essential at different times during the recovery process. But much of your recovery is going to happen between periods of clinical therapy. After the stroke, therapy is paid for by insurance for a few months. Once therapy ends, it is not the beginning of the end of your recovery, just the end of the beginning. There is still much work to do. And you will have to do that work without the luxury of having anyone there to remind you of the “right way” to move.

2. Relearning to move after stroke is like learning any new skill you’ve learned in your life. Trial and error is essential to learning how to move correctly. Mistakes allow for corrections and correcting mistakes is motor learning. Celebrate the movement you have.

3. There is little scientific evidence to support the idea that having clinicians move the survivors promotes recovery.

Many therapists see synergies as unwanted and to be discouraged. Ironically, using synergistic movement is the only way to eliminate synergies! Research has shown that repeated practice, known as repetitive massed practice, can overcome synergies. If done in a way that is both repetitive and demanding, practice of movements allows synergistic movements to melt away. In other words: You need the “bad” movement to get to the good movement.

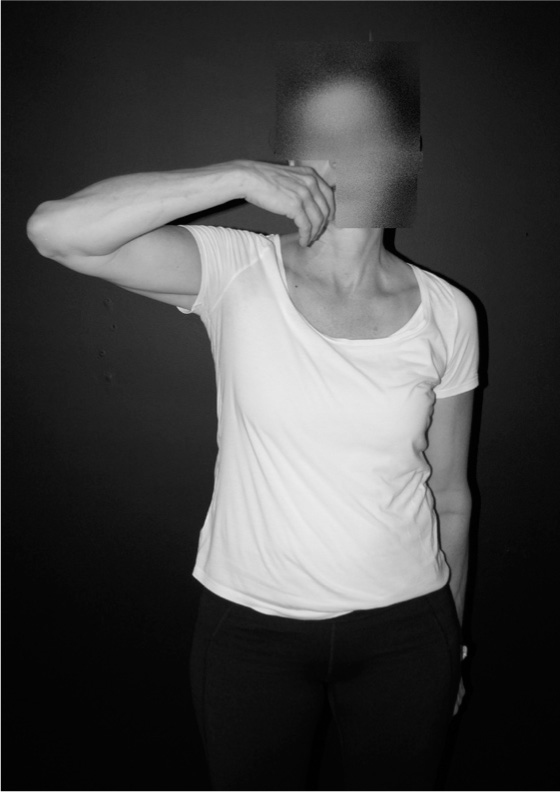

Both the arm and the leg have two kinds of synergies: flexor and extensor synergies. It may be that there is logic to synergistic movement after stroke. Have a look at the following images of the flexor and extensor synergies in the arm. What does the movement look like? (Hint: The brain uses about 20 percent of the total calories we consume!)

37

Extensor Synergy

Flexor Synergy

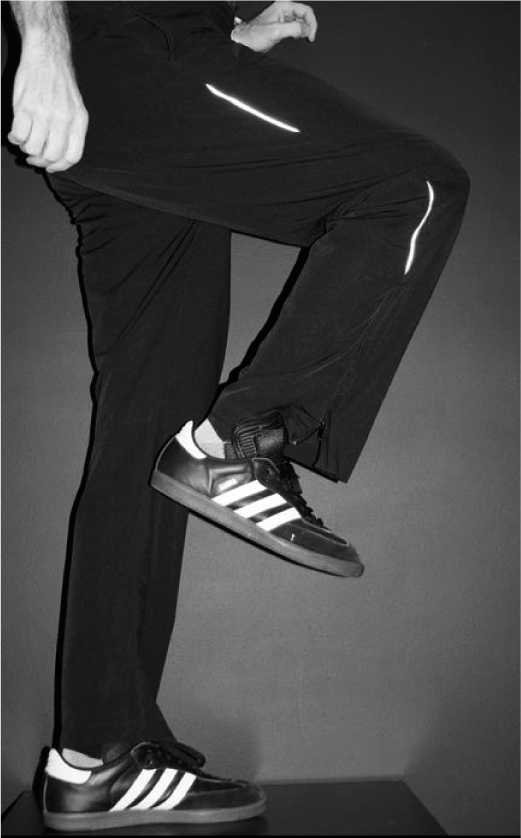

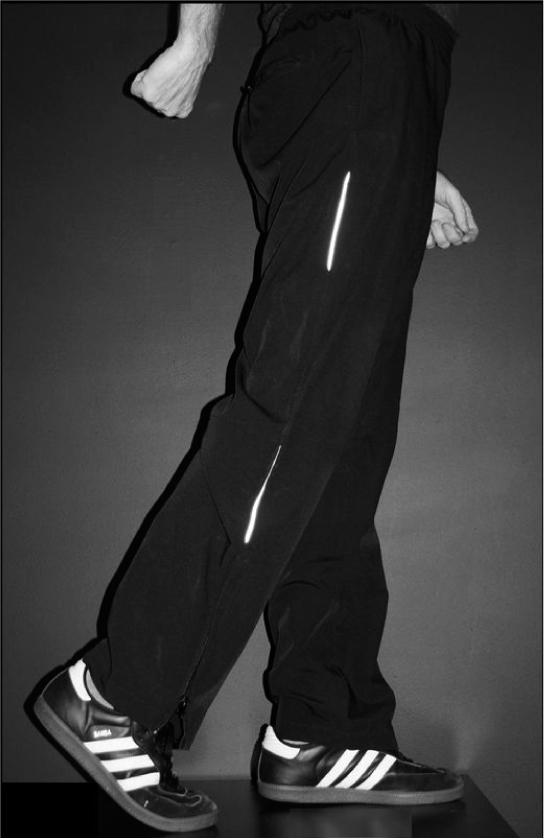

Here are the flexor and extensor synergies for the leg. What does that motion look like? (Hint: You don’t need a hint!)

Flexor Synergy

Extensor Synergy

38Synergistic movement is not bad movement. It is the movement that survivors often have, and they should use it. And what’s the alternative? No movement at all. No movement happens in two cases after stroke: (1) The survivor is flaccid (muscles do not work and the limb is limp), and (2) the survivor has spastic paralysis (the limb is frozen with spasticity). In these two scenarios there is typically little recovery because there is no movement to begin the process of gaining more movement.

So, if you have movement, even if it is “ugly” or synergistic—consider yourself lucky! Synergies are a portal to recovery.

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

Use of synergistic movement (the awkward movement after stroke) is not dangerous and will not ingrain those movements. Use the movement you have!

TRAIN WELL ON A TREADMILL

_______________

A treadmill is an effective recovery tool for folks who have had a stroke, as long as it is safe. Researchers have found that treadmill training can improve walking quality and increase walking speed. Treadmill training can also boost confidence in everyday walking around the house and around the community by increasing . . .

• Cardiovascular fitness (important in reducing risk of another stroke)

• Muscle strength (important for overall fitness and maintaining optimal weight)

• Balance (important in reducing the risk of falls)

• Coordination (important in reducing the amount of energy it takes to walk, which gives you the ability to walk faster and for longer distances)

Treadmills have the advantage of:

• Providing a safe, straight, flat, and never-ending path on which to walk

• Providing handles that offer endless parallel bars (the bars that stroke survivors hold onto while taking their first steps after stroke)

• Allowing long-distance walking in comfortable indoor settings

• Providing gradation of speed and incline (steepness)

• Allowing for detailed measurement of progress (usually provided as a digital readout about distance and speed on the treadmill’s dashboard)

How Is It Done?

First and foremost, consider the safety issues involved in treadmill training given your level of walking ability. Safety issues can be addressed by a physical harpist in one visit. The therapist will review how to safely step on and off a treadmill, as well as evaluate what speed is safe and challenging, given your fitness level. This therapy session should also include information on how to make treadmill training challenging as your walking improves. The physical therapist will review how and when to increase speed, distance, and incline as time goes on.

The next step is buying a treadmill. There are several advantages to having the treadmill in your home:

• The visual reminder of having the piece of equipment in your home

• The convenience: no travel, no traffic, no time lost

• You control the environment, including the music

• You can exercise whenever you are in the mood

A few hundred dollars can provide all the features you’ll need. Look for a treadmill that has:

• A motorized walking surface with at least 1.5 horsepower

• The ability to provide an incline (the ability for the walking surface to lift, as if you’re walking uphill). Stroke survivors often have “drop foot,” which is an inability to lift the foot at the ankle. Increasing the incline of the walking surface increases the challenge to the foot to lift at the ankle. This will develop coordination and strength in the muscles that lift the foot

• Handrails that are comfortable and that you can grasp quickly if needed

• An auto shut-off button that allows you to shut off the treadmill quickly. Look for treadmills that have a tethered cord that you attach to your clothes, which automatically shuts off the treadmill if you lose your balance

• Easy-to-read digital numbers

Always try out the treadmill before you buy it. Wear the same clothes and shoes you would normally use on the treadmill.

The question of where to place a treadmill requires some thought. There are the considerations of space and where in your home is appropriate to do the hard work of improving your walking. Before you buy a treadmill, measure the length, width, and height of the space where you expect to place it. There is also the question of distractions. If you put a treadmill in an area where there is a TV, radio, or other distractions, is this a good thing or a bad thing? Some therapists believe that stroke survivors should focus only on their walking. Other therapists believe that, since real-world walking involves a variety of distractions (e.g., TV, conversations, phone, traffic noise), the training should involve similar distractions. Alternatively, consider joining a gym (see the section Space to Focus—The Community Gym in Chapter 5) that has treadmills. The money you save on the treadmill purchase can be put toward a gym membership.

If your stroke caused a limp, treadmill walking will not necessarily decrease it if you do not try to look at and attempt to correct the quality of gait. During walking you have limited visual feedback because you see your walking from above, looking down toward your feet. You can better evaluate your walking by having a mirror at the end of a treadmill and walking “toward” the mirror.

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

Treadmills are relatively safe for some stroke survivors, but even for stroke survivors who walk well, treadmills have the potential to injure. The best way to determine the safety of treadmill walking for a particular stroke survivor is to have a quick visit with a physical therapist and let their expertise guide you. Precautions should be taken to ensure the proper use of the machine and that the treadmill is used within appropriate cardiovascular limits. Those who use assistive devices such as canes and walkers need to take special care. Treadmills are like moving sidewalks that have an electrical motor, which moves the floor belt in the direction opposite of the direction walked. This mechanism provides inherent risks. For instance, if you stop walking, the treadmill will keep moving backward. This is why it is important for treadmills 41to have a tethering system, so that if the person walking is carried backward by the machine, the treadmill will stop.

Before you get on any treadmill, make sure you know how to slow it down and speed it up, as well as the location of the emergency off button. Understanding how to safely and appropriately operate the treadmill that you use will allow for a safe, productive, and enjoyable experience.

MIRRORS REFLECT RECOVERY

_______________

This section is about using mirrors as an “instant feedback” mechanism to self-correct movement. Mirror Therapy (MT), a separate recovery tool, is discussed in Chapter 4.

Rehabilitation from stroke involves relearning movements that, prior to the stroke, were done perfectly. Memory (and observing the “good” side of your body) provides a clear image of what the movement looked and felt like. But many stroke survivors have problems accurately feeling where their limbs are in space (proprioception). They may also have decreased sense of touch, pressure, and temperature. The question becomes, how can you relearn how to move when you can’t feel how you’re moving?

One way to determine if movement is being accomplished correctly is to use a mirror. If you walk toward a mirror, you allow yourself instant feedback about the symmetry (evenness) of the two lower limbs during gait. Walking on a treadmill “toward” a mirror allows you to evaluate your gait for long periods of time. It also allows small, real-time corrections of gait. Mirrors can also provide constant feedback when you’re not walking; they can be used to evaluate the coordination, potential strength, and health of the entire affected side, including upper and lower extremities and the trunk.

Some stroke survivors are reluctant to look at the stroke-affected arm and hand. This phenomenon is called unilateral spatial neglect (or hemi-inattention). Even after they are reminded to look at the hand, they often will only glance at it as if it holds little interest to them. Another phenomenon caused by stroke is called apraxia. People who have apraxia move really well but they have little control over that movement. Mirrors can help survivors with both unilateral neglect and/or apraxia. Once a mirror is introduced, there is often a fascination by survivors with movement on the “bad” side. This fascination can provide a renewed focus on their quality of movement.

42How Is It Done?

Mirrors let you be the therapist and evaluate progress in real time. You may be reluctant to look at yourself in a mirror because you don’t like to see your impaired movement. But remember, it’s only you that’s judging.

Mirrors help survivors compare the “good” and “bad” side. As you look at yourself move, ask:

• Do both arms and hands have the same quality of movement?

• Do both sides accomplish the movement in the same way?

• If they are moving differently, what can be done to make the movements more alike?

Look closely at the quality of movement on the affected arm and hand. Try to have the “bad” side copy how the “good” side moves.

Many survivors find it hard to judge where their limbs are in space if they are not looking directly at the limbs. Again, the feel of where the limb is in space, even with the eyes closed, is called proprioception. Proprioception is often lost on the affected side after a stroke. Mirrors can help you tell if proprioception is intact. Try this experiment:

• Face a mirror so you can see your arms and hands.

• Close your eyes.

• Have someone move the “bad” arm and hand into a position and hold you in that position.

• Keeping your eyes closed, move the “good” arm and hand to match the position of the “bad” limb.

Now open your eyes and look at yourself. When the limb is seen in the mirror, does it feel like where it actually is? Are both limbs in the same position? The process of relearning proprioception is done using the same principles of neuroplasticity that are used to relearn movement: a whole lot of practice. Constant visual feedback can help to retrain the brain to remember how movements feel.

Mirrors can also be used to judge symmetry in the arms and legs. This perspective can help you assess the health of the “bad” side. These observations can best be made with clothing that reveals as much skin surface area as possible.

43As you look at your reflection, ask yourself:

• Is the “bad” arm or leg the same size as the “good” limb?

• Is the skin the same color?

• Do they have the same amount of hair?

• Do the joints look equal?

• Does one look swollen compared to the other?

• Are the shapes of the muscles the same on both sides?

All of these observations can provide insight into the way your body is recovering. Note: When looking at your “bad” side and you notice that it has . . .

• Change in skin color, including redness or paleness

• Shiny skin

• Swelling

• A change in hair growth

• A change in nail growth

. . . and these are accompanied with pain, you may have complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS). This group of symptoms, also known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD), or shoulder-hand syndrome (SHS), can hinder recovery efforts. (See the Glossary for a full explanation of SHS.)

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

Inform your doctor about any changes you observe that seem out of the ordinary. Decreased muscle bulk on the affected side is to be expected. Swelling, loss of hair, or change in skin color, however, may indicate something more serious.

THE MIND, THE BRAIN, AND STICKING TO THE TASK

_______________

What is the difference between the mind and the brain?

Mind: You. Your free will. Who you are. Your intentions. Who and what you love, and what you love to do.

Brain: 100 billion neurons inside your skull.

44Profoundly, your mind decides what your brain becomes. To recover from stroke, your mind is asking your brain to do a lot. Your mind is asking your brain to rewire massively. But rewiring for recovery is no fun. You’re not learning anything new; you’re just relearning what you used to do perfectly well. And this is a problem because the brain will not rewire unless the mind is motivated.

A great neuroscientist, Michael Merzenich, puts it this way: “If it’s not important to you, it won’t be important for your brain (and no positive change will occur).” Another great neuroscientist, Jeffrey Schwartz, simplifies the idea that the brain changes according to where you put your attention. As Schwartz puts it: “The power is in the focus.” Put together, these statements provide profound insight into the brain. You will focus on what is important to you. What you focus on helps determine how your brain is wired. Your brain will work incredibly hard to turn into whatever tool you want. But you have to want it. Focusing on things you really want to do will help you recover. Don’t just recover to do things you enjoy; use what you enjoy to recover.

So what’s the motivation? What do you care about?

Tennis, calligraphy, painting, writing, gardening . . . anything! By the way, it doesn’t have to be something athletic like golf, or artistic like making stained glass windows. The motivations can be much more basic and just as profound. Consider these scenarios:

Scenario I: An occupational therapist walks in to Mr. Smith’s room. She says to him, “Good morning, Mr. Smith! Today we’re going to work on toileting. Would you like to work on toileting today? Today’s task is toileting, yay!” What does Mr. Smith say? “Well, I guess I have to toilet. So . . . okay.” Everybody has to toilet, but let’s face it, it’s not very exciting.

Scenario II: The occupational therapist walks in and says “Aren’t you sick and tired of your wife transferring you to the toilet?”

Which perspective provides more motivation? It’s not about toileting; it’s about independence. Beyond what we love to do, what motivates us is everything from fear to friendship, and from money to childcare.

Focusing on what truly motivates is one of the many ways that stroke survivors are like athletes, musicians, and other people who use their bodies in incredible ways. Athletes and musicians tend to excel at what they do because they love what they do. And because they love what they do they’re 45willing to practice—a lot. What movements do athletes and musicians practice? They practice the exact movements, or parts of the movements, that they will perform during the game or concert. This is called task-specific training. Athletes and musicians are great role models for stroke survivors because they demonstrate the value of dedicated practice.

Imagine two stroke survivors that are exactly the same. They have the same deficits, the same age, everything about them is the same.

Passionate Paul is a drummer. His life as a drummer defines him. It is his work but it is also the fabric of his social life. With every rehabilitation effort he makes, he keeps one thing in mind: Get back to drumming.

Go-Along Gary works hard in rehab. He does everything his therapists ask him to do.

Every bit of rehabilitation research and neuroscience seems to point to the same thing: Passionate Paul will recover more. Of course, Passionate Paul has a much harder road ahead of him. Because he was an excellent drummer, his sights are set very high. For the first few weeks after stroke he can barely hold a drumstick. It requires a leap of faith for him to continue on.

You may wonder why you should try doing things that you know you can’t do. Research has shown that task-specific training is the best way to improve upon a given task. Therapists are experts at developing the “baby steps” that you need on the way to your lofty goals. You may not attempt the entire task any time soon. Instead, focus on small parts of the task. The therapist may have Paul just picking up and releasing the drumstick, repetitively. Later she may have him tapping his knee to the beat of music. Both of these—repeatedly grasping a drumstick and knee tapping—are important component parts of drumming. Practice component parts of what you love to do. Once you develop the ability to do the component parts, practice the entire task. This sort of practice is known as “part-whole practice.” Parts of a task are practiced, individually. Once those parts are mastered, they are put together for a more unified whole.

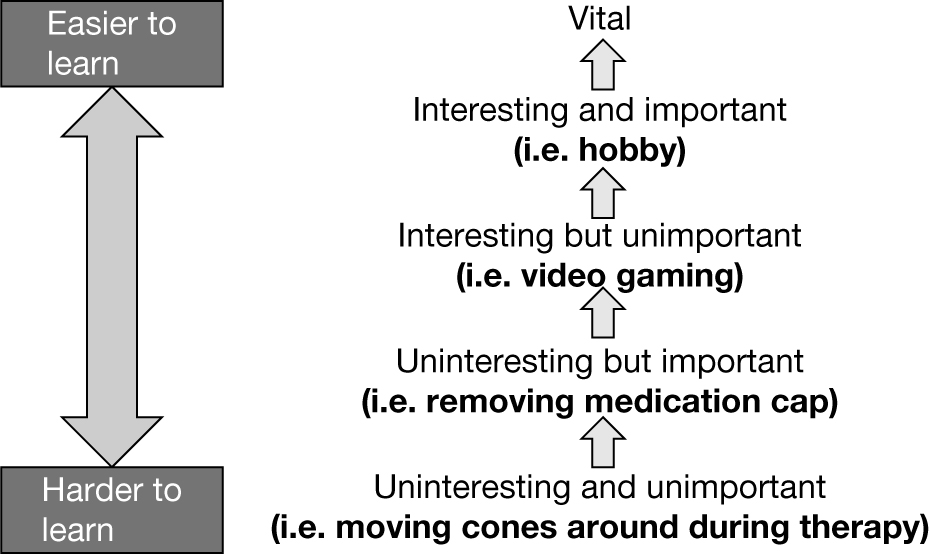

How Is It Done?

When doing task-specific training, it is essential to try activities that you really care about. The more cherished the task, the more focus will be brought to the 46training and the more brain rewiring will occur. A task’s level of importance can be expressed as this continuum:

For example, consider George, a stroke survivor who wants to get back to playing golf, which he loves. He knows he’ll never play golf again, so he does not think to mention it to his therapist. George is unable to turn his forearm so his palm faces up. His therapist has him hold a small barbell in his hand and let the weight flip until it forces the hand palm up. George could care less and feels like he’s spending too much time flipping the barbell. The therapist then has him play a video game where he has to manipulate a joystick by turning his hand palm up and palm down. He finds the game interesting for a while, and then gets bored. The therapist has George pretend to shave with a razor handle with no blade. George finds the task important. He does have to shave, but then again, he could do it with his “good” hand. Then the therapist suggests he start putting a golf ball. At first George refuses. “I’d rather remember my game the way it was.” The therapist is surprised to hear that George is a golfer, and encourages him to try. George is told to try to putt one-handed with his affected hand, trying to turn his forearm so he can put the ball straight. George goes home with his forearm aching. “That was fun!” he says. He doesn’t even wait for the next therapy session. He goes to a sporting goods shop that evening and buys an electric ball return. (He starts to imagine returning to golf!)

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

Task-specific practice is tiring because the motivation to perform the activity is high. Fatigue can lead to accidents. Ask your doctor and/or therapist if the chosen task is safe and appropriate to perform during your recovery.

47LET RECOVERY FLOW

_______________

Everybody is most motivated by the activities they love. There is a natural tendency to focus on, practice, and pursue activities you love to do. When stroke survivors work on things they are passionate about, it is no longer work, rehabilitation, or exercise. Recovery becomes play. Athletes talk about being “in flow.” Being in flow is when you are so immersed in an activity that you lose track of time. When an athlete is in flow, all the problems in life melt away and all that is left is the sport. You can use flow in recovery. Being in the flow of recovery:

• Eliminates self-doubt and self-consciousness

• Allows you to focus on recovery on an instinctive level

• Allows you to focus on nothing but recovery

• Makes recovery enjoyable

• Makes time seem to stand still

• Reduces any aches and pains associated with recovery

• Makes recovery addictive because the feeling of being in flow is addictive

How Is It Done?

One of the most important concepts in stroke recovery is this: necessity drives recovery. Define what is essential to your:

• Identity (work, family)

• Passions (hobbies, your art, sports)

• Happiness (playing with grandchildren, attending church)

• Life (cooking, cleaning, grooming)

• Independence (walking)

Walking is a great example of “necessity drives recovery.” Everyone knows the importance of walking. Work to recover everything the same way you relearned walking. Identify what is most important to you, and use those things to drive your recovery. If you are working toward goals that you really care about, your effort toward recovery is magnified. Research studies have shown that when stroke survivors focus on meaningful activities they get 48better, faster. “Meaningful” suggests an emotional connection to what is being practiced. If there is no emotional attachment to what you’re attempting to recover, you won’t see the practice as meaningful.

Therapy in a clinic may be effective but not necessarily motivating. Consider playing catch as an example. Therapists often play games of catch with stroke survivors in order to challenge balance, arm movement, and reaction time. This sort of exercise may be fun, and it may indeed help recovery, but playing catch may not hold any importance to the stroke survivor. Therapists use treatments to help make you safer and more functional. But once you return home, motivation may be lost if you are not working on a meaningful goal. The more important the activity is to you, the more motivated you will be. The more motivated you are, the more recovery you’ll get. Necessity drives recovery. Practicing what you really care about can provide motivation for other tasks that you may find boring. For instance, you may find treadmill walking boring and tedious. But if you are a golfer and treadmill walking follows the yardage of a favorite golf course (a typical golf course involves about five miles of walking!), then you will be more motivated to train on a treadmill.

Sometimes doing the activity is impossible because you just don’t have enough strength and coordination, so you take the small steps necessary toward building strength and coordination. Even when you are taking the small steps toward the meaningful activity, the activity should always be in view. This may involve having the tools of that activity visible. Even if you are unable to achieve any part of the activity right now, the meaningful goal should be the guiding light as you move toward that goal.

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

Incorporating activities that you find meaningful into the process of rehabilitation is a positive move, as long as those activities are safe. If you loved to mountain climb prior to the stroke, then pursuit of that particular passion probably won’t be safe—in the short run at least! Attempt cherished activities with common sense. The stroke survivor should stay within his or her skill level and make safety the number one priority.

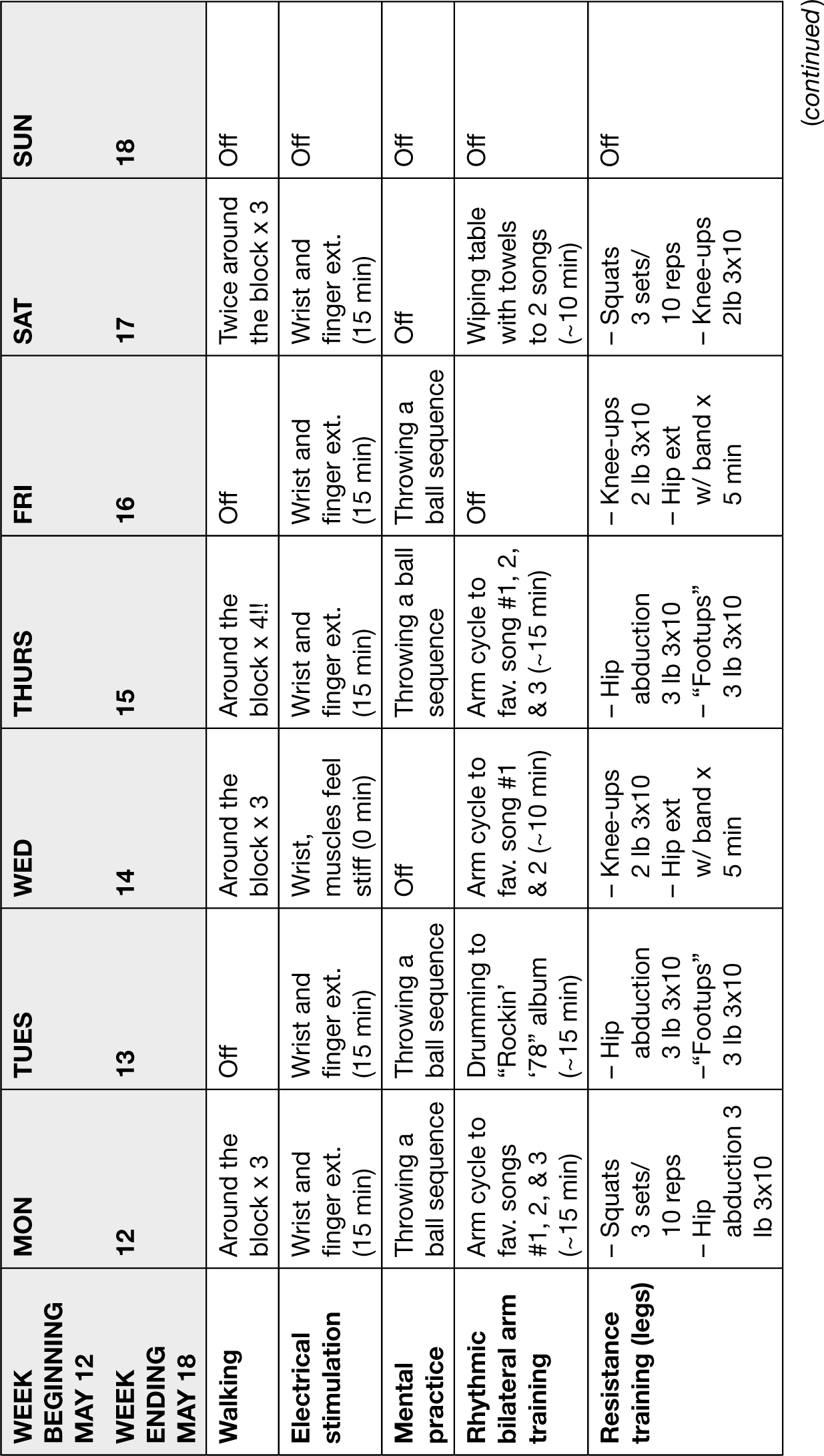

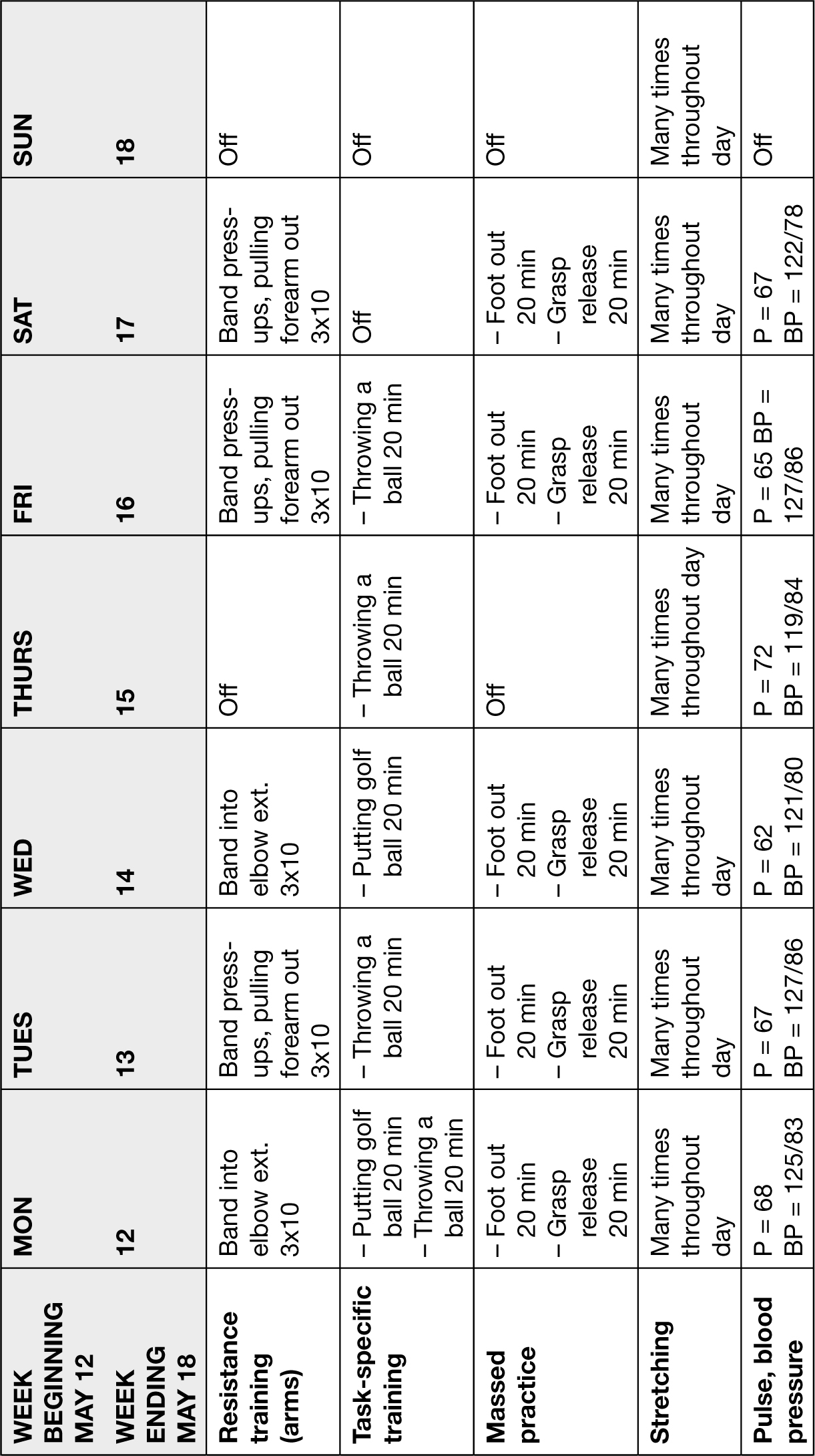

49THE RECOVERY CALENDAR

_______________

Appointment calendars keep people organized and on schedule. Important appointments, including doctors’ appointments, business appointments, and meetings, are all noted. Your recovery efforts deserve a calendar, too. The recovery calendar will help you stay on schedule, and the act of crossing off the items will be partial reward for all the hard work you’ve done. Keeping a recovery calendar is an easy way to stay motivated and focused. The calendar itself is a reminder to work toward recovery. Also, a calendar helps you evaluate the effectiveness of your recovery effort, the progress you’ve made, and the goals you wish to achieve. A workout calendar is an essential part of the overall recovery plan.

A calendar dedicated to recovery will:

• Keep track of successes and failures

• Help establish what works and what does not

• Help spot positive and negative trends in the quest toward recovery

• Help separate effective therapies from lemons

• Help measure progress by providing an accessible and detailed account of the arc of recovery. For instance, you may see that the longest walk last month was 20 yards and the longest walk this week was twice that amount.

• Record progress, which is essential to defining and achieving goals

• Help increase adherence to goals

• Add to the sense of accomplishment as goals are met

• Provide an accurate record on which to look back

• Provide valuable information to doctors and therapists as they help you plan your recovery

Calendars allow you to look back and see what you’ve accomplished. A calendar can also be used to predict new goals. For instance, if in April you walked 100 yards in a single walk, you might be able to project that you can walk 150 yards by June 15th. You can then anticipate and train toward specific projected goals.

50

51

52How Is It Done?

Workout calendars are commercially available in bookstores, as downloads from the Internet, or one can be made using personal computer word-processing programs. A recovery calendar only needs three elements:

1. A row for dates

2. A column for the interventions, exercises, or modalities

3. Columns and rows of boxes to input appropriate statistics

An example of a recovery calendar follows. Do not consider this example as a suggested course of interventions.

Use a pencil when filling out your calendar. This will give you the ability to correct mistakes and change future goals.

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

There are no specific precautions that should be taken for the actual calendar. Discuss daily recovery activities with your doctor. Please note that the calendar example provided is not a representation of any existing calendar. Do not consider the example as a suggested course of interventions.

ROADMAP TO RECOVERY

_______________

Hypocrites (460–370 BC), the “father of medicine,” was the first to describe stroke, transient ischemic attacks (TIAs or mini-strokes), and aphasia. His word for stroke was plesso, which has been variously translated as a stroke of God’s hands, to be thunderstruck, and to inflict with calamity. You can imagine how much the ancient Greeks were frightened and confused about stroke. Stroke has no obvious wound, bleeding, or infection, and is often not painful. But despite the lack of outward signs, stroke was often devastating.

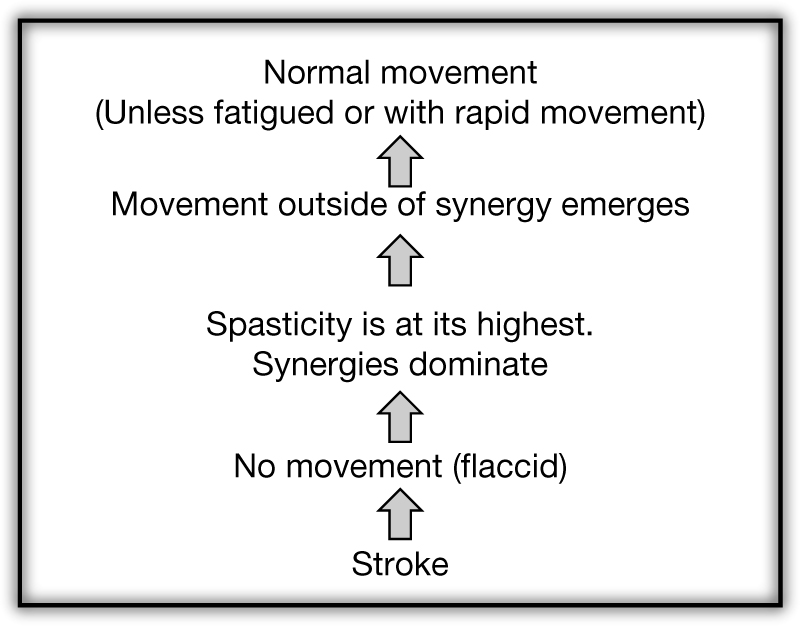

As centuries passed, the understanding of stroke and its treatment increased, while understanding of recovery remained limited. It was not until 2,400 years after Hypocrites that someone recognized the predictable pattern of recovery after stroke. Her name was Singe Brunnström. Brunnström, a Swedish Fulbright Scholar and pioneer physical therapist, wrote a seminal stroke treatment book, Movement Therapy in Hemiplegia (1970). In her “six stages 53of recovery” she describes the predictable arc of recovery. This arc goes from total paralysis to total recovery. The amazing aspect of this roadmap to recovery is that it holds up against today’s scientific measures. For instance, brain scanning technology reveals that Brunnström’s stages of recovery can be used to predict the amount of damage in the brain. Brunnström’s professional career ended in the mid-1970s. Brain scanning technology was first seen in hospitals in approximately 1980. (How did she do it?)

Synergy

After stroke, the limbs tend to move in unusual ways. Sometimes the limb cannot make any one movement without making a whole series of unnecessary movements. Typical movement after stroke, where everything in the limb moves at once—even though you don’t want it to—is called synergistic movement or, simply, synergy. Synergies were fully explained in the section Use What You Have, earlier in this chapter.

Briefly, synergistic movement after stroke involves patterns of movements that cannot be isolated. For instance, a survivor cannot only bend only her elbow without a whole bunch of other movements appearing. Understanding synergy and synergistic movement will help you understand the wealth of wisdom within Brunnström’s stages of recovery.

Synergistic movement is not bad. Synergies are evident in all animals and all humans—even humans who have not had a stroke. Synergies are caused by “motor modules,” pathways of neurons controlling several muscles simultaneously. Although mostly tested in gait (walking), it is theorized that synergies help us do many other tasks as well. Synergies are used to bundle movement so we have to think less about our movements. Synergies make movement automatic. The problem after stroke is that some of the more coordinated synergies are destroyed by the brain injury. What are left are more “primitive” synergies. These more basic synergies are expressed in the movement patterns commonly seen after stroke. As recovery from stroke progresses, these less coordinated synergies become less apparent. What emerges is better, more coordinated movement controlled more and more by the brain.

How Is It Done?

Until Brunnström described the arc of recovery, there was no agreed-upon roadmap to recovery. Brunnström’s six stages of recovery provide that roadmap. 54These six stages also answer many of the questions that you’ll have about your recovery, including:

• Where you are in the recovery process

• What new skills appear as progress is made

• What challenges are in the existing stage (spastic, synergistic, limp, etc.)

• What you are striving for, and how you’ll recognize it when you achieve it

Researchers use tests based on the six stages as an accurate measurement of progress. You can, too! As you look back at how far you’ve come, you’ll remember the stages you’ve overcome. As you continue your progress, you will notice that you are moving through the stages, one by one.

In the first stage, the whole hemiparetic (“bad”) side of the body is flaccid, and the sixth stage is total recovery. Here are the six stages.

Stage 1

During the first stage, the whole “bad” side is completely limp. The arm, the leg, the torso, the face (including the mouth and tongue) are limp.

Stage 2

Spasticity (muscle tightness) starts to creep into the “bad” side of the body. Spasticity is generally considered a good thing (at this point) because the affected side is no longer limp. Spasticity signals the beginning of messages getting from the nervous system to the limbs. Stage 2 is also when a basic form of synergies appears. There may be some small amount of voluntary movement available, but only within synergy.

Stage 3

During Stage 3, spasticity is at its strongest. Spasticity may become severe during this stage. That is the unfortunate part of Stage 3. The bright side is that you begin to control the synergies. This means that the limbs can be moved voluntarily as long as the movements are within synergies.

Stage 4

During Stage 4, spasticity begins to decline. In this stage, some movements outside of synergy appear. So, two positive things 55occur during Stage 4: Spasticity and synergistic movements begin to decline.

Stage 5

Synergies continue to decline. Folks in Stage 5 enjoy more voluntary control out of synergy. Spasticity continues to decline as well. Some movements appear normal.

Stage 6

This is the final stage. If this stage is achieved, movements look normal. Spasticity is absent except when fatigued or performing rapid movements. Individual joint movements become possible, and coordination approaches normal.

Here is a visual representation of Brunnström’s stages of recovery from stroke:

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

Here are some more ideas that relate to the six stages:

• Recovery always moves through the six stages in order. Stages may be brief, but you will go through all of the stages in order. For instance, if you are in Stage 2, you will go through Stage 3 on your way to Stage 4. And you have to go through Stage 4 to get to Stage 5, and so on. A survivor will never go from Stage 5, back to Stage 3.

• Even if you do no work and have no therapy, you still might see progress.

• The process of recovery may be quick or slow and may end. This ending of recovery is what is called a plateau. (If stroke survivors work hard, plateaus in recovery tend to be temporary periods. These periods can be used to change what you are doing in order to have progress continue. However, stroke survivors sometimes do not, for a variety of reasons, continue to progress.)

• You will see recovery in the joints close to the body (e.g., the shoulder and hip). Recovery will then spread away from the body (e.g., the fingers and toes).

• No two stroke survivors recover in the same way.

• Recovery of the hand is the hardest to predict. The intricate movement of the fingers and the many different motions of the thumb make any predictions almost impossible. The hand is also usually the last part of the body to regain movement.

• Ability to close the hand will come back before the ability to open the hand.

TIPS FOR THE CAREGIVER

_______________

If you’ve read this far, you know that the message of this book to the stroke survivor is simple: The highest level of recovery is only possible with relentless hard work. Caregivers have an equally simple reminder: Your job is to help that hard work.

From the shock of first learning that a loved one has had a stroke, and often for decades to come, caring for a stroke survivor can be overwhelming. The sprint of activity in the acute stage gives way to the full marathon of recovery. The stroke survivor has to do all of the work of recovering, but the caregiver provides support, resources, energy, and time. All of these elements are essential to the recovery effort.

Stroke is different from other forms of diseases of the nervous system. Most diseases of the nervous system are progressive (i.e., the symptoms get worse over time, such as with Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and multiple sclerosis). Stroke is not progressive, and stroke survivors have the chance of recovering what the stroke took—with a lot of hard work. The possibility of recovery 57puts extra stress on caregivers because it is often difficult to know when to push and when to back off. Further stress is added when caregivers believe that the success or failure of the stroke survivor is dependent on their care, encouragement, and support.

How Is It Done?

Next to the stroke survivor, caregivers have the most to gain from the survivor’s fullest possible recovery. Aiding in the recovery effort has the caregiver fighting on two fronts:

• Helping the stroke survivor recover

• Maintaining their own sanity

It’s a tricky balance and, much like recovery from stroke itself, full of ups and downs. Here are some suggestions for the caregiver

• What caregivers should do for themselves:

— Contact your rehabilitation doctor (physiatrist) and other rehabilitation personnel to educate you in the proper transfer techniques (e.g., from bed to standing or from chair to couch), fall recovery (when and how to help), tricks to facilitate activities of daily living, and so on. A solid foundation in these basics will help the caregiver help the stroke survivor.

— Keep records of progress made, and note any other pertinent information (lists of medications, important phone numbers, etc.).

— Keep in mind that many caregivers believe that working with their stroke survivor is an enriching and fulfilling experience.

— The recovery of a stroke survivor calls for a coach, mentor, teacher, friend, and confidant. Having all these roles assumed by a spouse or any other single individual is a recipe for burnout. Caregivers who wear themselves down are less effective in helping to manage the recovery process. Friends, children, professional caregivers, therapists, and doctors can share in the effort.

• What caregivers should do for the stroke survivor:

— Provide the infrastructure for the stroke survivor to succeed. This may involve anything from ordering exercise equipment to doing research.

— Allow the stroke survivor to challenge themselves. For example, allow the stroke survivor the time to get the sentence out, rather than finishing the sentence for him, or time to cut his own food, despite the difficulty.

• The caregiver can do three things, every day, that will help keep recovery on track.

— Be a cheerleader. Provide praise. Point out progress. Encourage. Allow mistakes, but also catch the survivor doing things right.

— Be a teacher. Help facilitate proper technique and quality of movement.

— Modify whatever skill is worked on to be challenging. There are many physical challenges that are part of life after stroke. These challenges are, ironically, the best tools for recovery from stroke. Many of these challenges can push the stroke survivor into uncomfortable but productive territory. Resisting the urge to make life easier for a stroke survivor helps lead to gains. There are unmarried stroke survivors who claim that they have recovered because they had to recover. There was no one around to “do for them.”

After a stroke, survivors are given a tough message. To someone who has not had a stroke, it might sound a bit like this: “You now have to learn to play piano, learn gymnastics, and learn French. And you have to do it all at the same time. Oh yeah, and you’ve lost your job.” Understanding the depth of the challenge of recovery will help the caregiver appreciate the spiritual turning point that recovery becomes.

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

Caregivers who are stressed have a higher rate of depression, illness, and even death than caregivers who effectively deal with the stress and take care of themselves.

An essential resource is provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). It is a website that provides a portal to hundreds of pages of caregiver support, suggestions, and organizations. You can find it at www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/caregivers.html