1456 Recovery Strategies

THE FOUR PHASES OF STROKE RECOVERY—AND WHAT TO DO DURING EACH

_______________

There are four phases after stroke:

• Hyperacute → Acute → Subacute → Chronic

There are two ways of describing the four phases.

1. The “one size fits all” timeline.

2. The “unique” timeline. This timeline reflects the recovery of individual survivors.

Both definitions are useful.

The “One Size Fits All” Timeline

This timeline is an average of the stroke recovery process. It provides a generalized perspective on where the survivor is in recovery. If a survivor says, “My stroke was seven months ago” doctors and therapists can make certain assumptions about where the survivor is in recovery. The “one size fits all” timeline is also useful in research. It can be used to define a group of survivors on which a treatment is used. For instance, the research may involve “survivors that are three to five months post (after) stroke.”

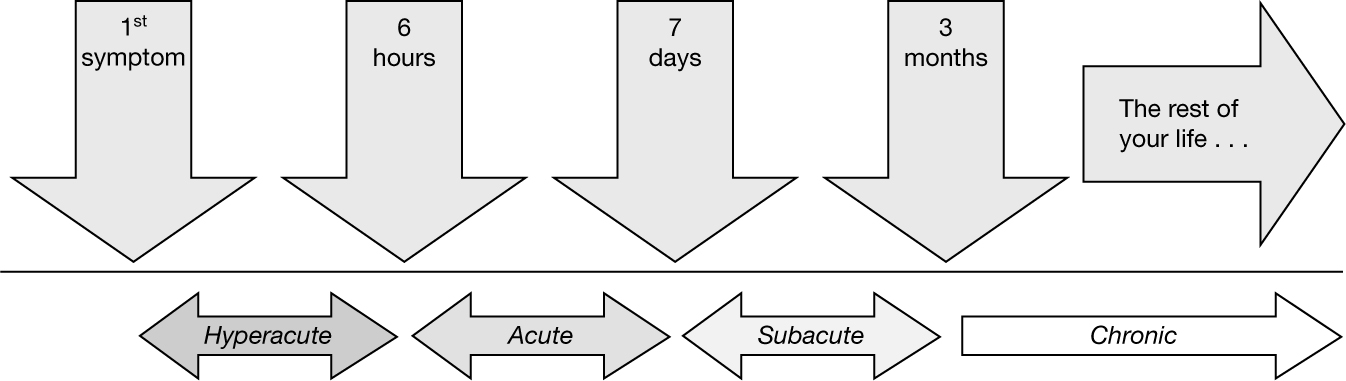

The four stages of stroke according to the one-size-fits-all timeline:

1. Hyperacute: From the first symptom to the first six hours

2. Acute: The first seven days

3. Subacute: The first seven days to three months

4. Chronic: From the first three months to the end of life

The phases of stroke recovery as a “one-size-fits-all” timeline.

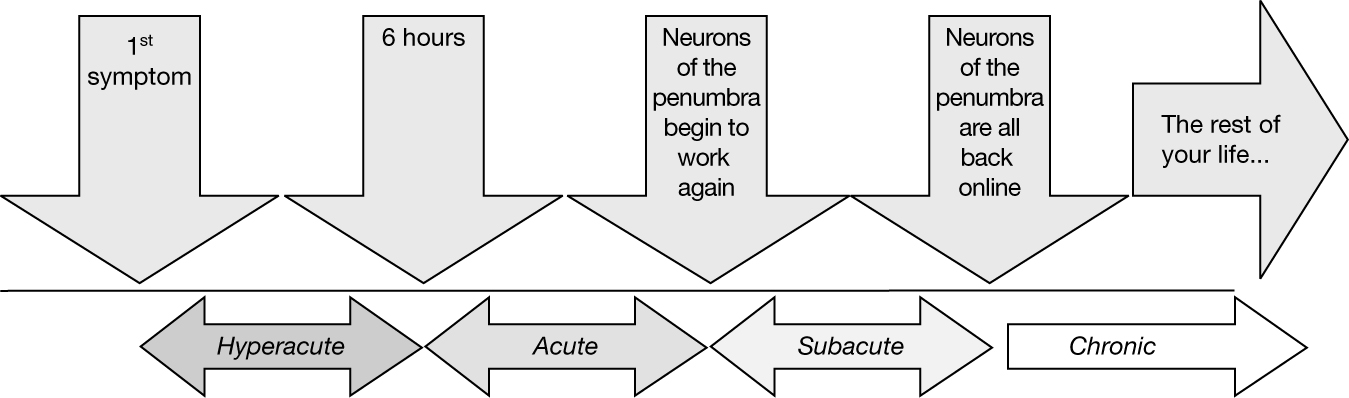

The “Unique” Timeline

The “unique” timeline comes from studies of brain scans of stroke survivors. These studies reveal that the course of every stroke is different. Every stroke survivor enters and exits the phases of recovery at different times.

Choosing the best available strategy option partially depends on where the survivor is in recovery. Different strategies work during different phases. Also, certain treatment options can be detrimental during certain phases, so it’s important to know what phase the survivor is in.

Determining the phase a survivor is in is often a matter of simple observation. The way the body moves provides insight into what is going on in the brain. The survivor and everyone around the survivor can help determine which phase the survivor is in.

The phases of stroke recovery as a unique timeline.

147Hyperacute Phase

BEGINS |

ENDS |

The first symptom of stroke |

Six hours after the first symptom |

In both forms of the timeline, the hyperacute stage is the same:

• From the first symptom to six hours after the first symptom

Once the first symptom is recognized, the clock is ticking! Some survivors do not receive emergency care during the hyperacute period. This is unfortunate because this the only period in which an aggressive “clot-busting” drug can be given. This drug, called tPA (tissue plasminogen activator), is a thrombolytic (thrombo: clot; lytic: breaking down). (Note: This does not apply to hemorrhagic “bleed” strokes. tPA is contraindicated in bleed strokes.) The recovery for survivors who receive tPA is usually both better and faster. This is why recognizing a stroke, and getting to emergency services, is vital. The faster the survivor can receive emergency care, the better chance they have of getting tPA. Receiving tPA can even happen before you get to the hospital. There are now “mobile stroke units.” These ambulances have equipment and personnel that can diagnose and treat with tPA before the survivor reaches the hospital. Literally: Time Is Brain. This phase is also critical to providing other medical interventions that can save the brain. Getting immediate care is not only essential to saving as much brain as possible, it is often essential to saving the survivor’s life.

What Is the Best Recovery Strategy During the Hyperacute Phase?

The most important thing a survivor and caregivers can do to aid recovery is to seek emergency medical care as soon as possible. Call 911. Time lost is brain lost. There is no rehabilitation during this period. If the patient is conscious, there may be tests of movement by medical staff. These tests provide information about the amount of damage that the stroke is causing over time. However, the focus of this stage is:

1. Saving the patient’s life

2. Saving as much brain as possible

148Acute Phase

BEGINS |

ENDS |

The sixth hour after stroke |

1. When the blood supply has been restored 2. There is no further damage is caused by the stroke 3. The survivor is “medically stable” 4. The first neurons of the penumbra begin to come back on line |

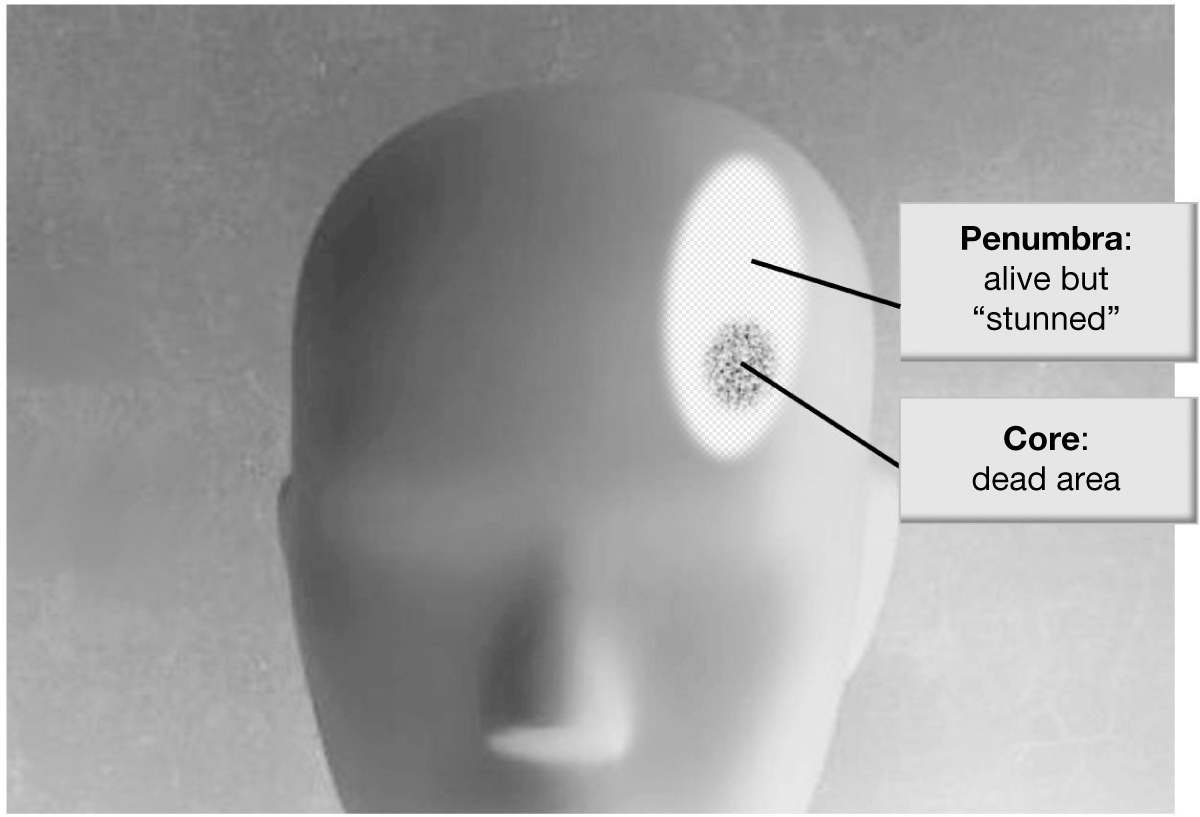

During the acute phase, two distinct areas emerge in the brain: the core and the penumbra.

1. The core . . .

• Was killed by the stroke

• Has all its neurons (nerve cells) die

• Has no chance of brain rewiring (neuroplasticity)

• Forms a cavity in the brain that fills with fluid

2. During the acute phase, the penumbra:

• Is much larger than the core (the area killed by the stroke)

• Represents billions and billions of neurons

• Is alive, but just barely

• Will end up being useful, or useless, depending on what is done during rehabilitation

The stroke causes interruption of blood supply to the core and penumbra. The blood supply is interrupted because the blood vessels are either blocked (in a “block” stroke) or bursts (in a bleed stroke).

The interruption of the blood supply causes the core to die. The penumbra stays alive, but just barely. Because the main blood vessel is (at least temporarily) not working, the penumbra relies on smaller blood vessels to stay alive. The neurons in the penumbra get enough blood to stay alive during the acute phase. But those neurons get less blood than they need. Because of the diminished blood supply, the neurons in the penumbra are not able to do their job.

But there is another problem for the billions of neurons in the penumbra.

An injury to any part of the body will cause many body systems to come to the aid of the injured area. Think of the swelling caused by a twisted ankle or a bruised arm. The same happens to the penumbra after stroke. During the early phases after stroke there is swelling in the area. This is caused by many chemicals dispensed in the penumbra. Calcium, destructive enzymes, free radicals, nitric oxide, and other chemicals are delivered to the area. The area is awash in a “metabolic soup” designed to aid healing, but that causes swelling. While the mix of chemicals aids in healing, it provides a poor environment for neurons to work.

So the penumbra is dealing with two issues caused by the stroke:

1. Lack of adequate blood supply

2. A mix of chemicals that interfere with neuron function

These two factors leave a large swath of the brain (the penumbra) unable to operate. Neurons in this area are alive, but they are “stunned.” The technical term that is used is “cortical shock” or “cerebral shock.” This leaves many survivors with paralysis. But paralysis during the acute phase is 150not necessarily permanent. For some survivors, the neurons of the penumbra do start working again. Recovery of the penumbra happens in the next phase; the subacute phase.

What Is the Recovery Strategy During the Acute Phase?

Intensive therapy is a bad idea during the acute phase.

The brain remains in a very delicate state during the acute phase. The neurons of penumbra are especially vulnerable. Consider the studies of animals that have been given a stroke. Animals forced to do too much too soon increase the damage to their brains. In human studies, the results of intensive rehab (too much, too soon) have been mixed at best. Science will continue to add clarity to the question, “How much is too much during the acute phase?” Until then, the rules are simple:

• Follow doctors’ orders

• Listen to the therapists and nurses

• Don’t push it

Intensive efforts to recover during the acute phase will hurt recovery. But that does not mean that there is no therapy. Doctors place many survivors on bed rest for the first two to three days after stroke. However, even during bed rest, therapy will begin. Therapists will often do passive (without any patient effort) movements of the survivor. The survivor’s limbs will be moved through their range of motion. These movements, called “passive ranging,” will help retain muscle length and keep joints healthy.

Once the doctor gives the okay to come off bed rest, therapists will use their clinical judgment to gently and safely get the survivor moving. During the acute phase, most therapy is done “bedside” (in the patient’s room). Therapists will gently get the survivor moving. Therapists who work with acute survivors often sum up their treatment philosophy with a simple phrase: “We do whatever the patient can do safely.”

Before providing therapy in the acute phase, therapists will test . . .

• Judgment and safety awareness

• The ability to follow commands

• Orientation (i.e., “Where are you? Who am I? What is the time of day, season, etc.? Many patients may feel insulted by the simplicity of these questions. These questions are, however, essential to establishing safety.)

• Memory

• Problem solving

• Vision

• Ability to actively move the limbs (active range of motion, or AROM)

• Strength

• Fine motor coordination

• Sensation

Once evaluated, therapy starts with very simple movements and activities. For instance, if it is safe, therapists will help survivors . . .

• Reach, touch, or grasp objects with the “bad” side arm/hand

• Sit on the edge of the bed

• Go from sitting to standing

• Walk

During the acute phase, listen closely to therapists. Therapists as well as doctors and nurses will provide guidance about what recovery strategies should be done. Caregivers can also help by doing therapists-suggested activities during the time when the survivor is the most alert. Activities might include anything from having a conversation with the survivor to encouraging basic movements (e.g., opening and closing the hand).

There is another way caregivers can be vital to recovery during the acute phase. Because they are often with the survivor many hours a day, caregivers can alert therapists to changes in the ability to move. For instance, let’s say the survivor cannot bend his or her elbow at all on Monday. Then—without any practice at all—on Wednesday, they can bend the elbow a few degrees. This is known as spontaneous recovery. Spontaneous recovery is vital to recognize for two reasons:

1. It is the harkening of the subacute phase (discussed next)

2. It is the harkening of when really hard and productive work can begin

If the caregiver observes spontaneous recovery, report it to the therapist! The most important phase of recovery (subacute phase) has begun!

152Subacute Phase

BEGINS |

ENDS |

The first neurons of the penumbra come “on line” |

All the neurons in the penumbra are “on line” |

The subacute phase is a time of great hope for many stroke survivors. There is a huge influx of neurons that allow the survivor to recover at a rapid pace. Much of the recovery is considered spontaneous recovery (lots of recovery with little effort). The reason for this rapid spontaneous recovery is that neurons that were “off line” are coming back “on line.” Some survivors make a near full recovery during the subacute phase. Other survivors are not so lucky. They take longer to reengage the neurons of the penumbra. For these survivors there is a problem with the penumbra.

The Problem With the Penumbra

The brain is very “use it or lose it.” If the neurons of the penumbra are not challenged to work again, they stop working. This process (unused neurons losing function) is known as learned nonuse. (For a full explanation of learned nonuse, please see the section Constraint-Induced Therapy for the Arm and Hand in Chapter 4.)

But why would the neurons of the penumbra not be used? Certainly the survivor will be encouraged to move. And that movement will reengage neurons, right? For the minority of survivors this is exactly true. For these “lucky” survivors, functional (usable, “real world”) movement is quickly gained, and learned nonuse never takes place.

For many survivors learned nonuse is, well, learned. Much of the reason learned nonuse takes root is the “meet ‘em, greet ‘em, treat ‘em, and street ‘em” mentality forced on therapists by managed care. Therapists are sensitive to Rule No. 1: Get them safe, functional, and out the door. Being functional is the end goal. But for survivors who don’t yet have function, there is only one way to “get out the door”: Compensation (using only the “good side” limbs to get things done). Using the “good” side to do everything means neurons in the penumbra lack the challenge needed to come back “on line.” As the neurons of the penumbra become useable, nothing is asked of them, and learned nonuse sets in.

153What Is the Best Recovery Strategy During the Subacute Phase?

The subacute phase is the most important phase in the process of recovery. The intensity and quality of effort during the subacute phase will help determine the amount of recovery. A successful subacute phase ensures the highest level of recovery.

During the subacute phase, the billions of neurons that have survived the stroke become available to go back to work. The point at which each and every neuron is available is the beginning of the chronic phase (discussed next).

Much of recovery during the subacute phase comes from neurons that were “off line” coming “online.” This is the essence of spontaneous recovery: Neurons that were not available for work become, during subacute phase, available for work. During the subacute phase, many survivors have an opportunity to “ride the wave of spontaneous recovery.” Everyone is willing to take credit for the recovery. The survivor may say something like, “I’m getting a lot of recovery because I’m working really hard,” and the therapist may think that the survivor is recovering because of the great therapy. But much of the recovery during the subacute phase is because billions and billions of neurons are rushing back to become usable again. Just as is true when swelling goes down after you injure a muscle, as the swelling goes down after stroke, neurons become available to go back to work.

Because rehab during the subacute phase is so important, it gets its own section! Please see section titled The Subacute Phase: Recovery’s Sweet Spot (later in this chapter) for suggestions on how to use the subacute period to achieve the highest possible level of recovery.

Chronic Phase

BEGINS |

ENDS |

All the neurons in the penumbra are “on line” |

The end of the survivor’s life |

At some point, all the neurons of the penumbra are back online, so there is no “wave” to ride. This is the harkening of the chronic phase.

As the subacute phase ends and the chronic phase begins, the survivor is left with two kinds of neurons. Let’s call them “working neurons” and “lazy neurons.”

154Working Neurons

Some neurons do just fine and go right back (during the subacute phase) to what they were doing before the stroke.

For instance, neurons might go back to . . .

• Straightening the elbow

• Lifting the foot during walking

• Controlling the mouth during speech

• Opening the hand

• And so on

Working neurons resume their pre-stroke responsibilities. These are the neurons that, as they rush back on line during the subacute phase, propel spontaneous recovery.

“Lazy” Neurons

These neurons are never asked to do anything after the stroke. Through the process known as learned nonuse, they “lie fallow.” This is usually the case when, during the subacute phase, the survivor is taught to compensate with the “good” side to become “functional.” But there is a downside to this rush toward functional. As is true with the rest of the brain, each and every neuron is “use it or lose it.” What “lazy” neurons lose are connections between themselves and other neurons. These connections are called “synaptic connections.”

Normally, neurons use connections to communicate with other neurons. Because those connections are used, they remain working. When a neuron does not communicate with other neurons, connections are lost. This is the essence of the “use it or lose it” aspect of the brain. What is lost are connections between neurons, but not just the connections are lost. Within each of these nonworking neurons is a loss of dendrites. Dendrites are the branching arms that provide the connections between neurons. And “branch” is the perfect word. In fact, the technical term used for the shortening of these branches is pruning—just like pruning the branches of a bush or tree. The phrases scientists use are “pruning of the dendritic arbor” or, simply, “dendritic pruning.” This is what happens to “lazy” neurons affected by learned nonuse. They prune connections.

155Losing More Than What the Stroke Took

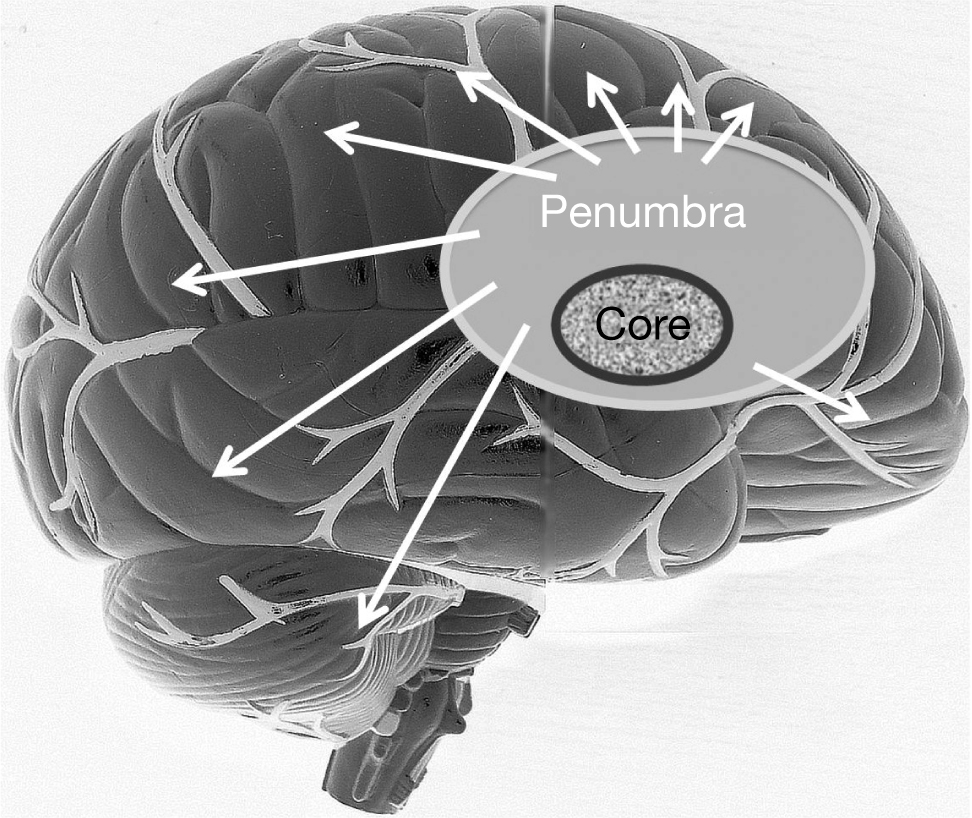

Learned nonuse expands the influence of the stroke to beyond what is killed by the stroke. Learned nonuse drags the penumbra down with it, radically increasing the effects of the stroke. And that would be bad enough. But it gets worse. The brain also has to deal with diaschisis.

Diaschisis: Expanding the Stroke Footprint

Meet Dave, an avid tennis player. Dave had a stroke. For a while after the stroke, Dave is unable to attempt to play tennis.

Dave has not only lost his ability to play tennis. Many other tennis-related skills are also lost because Dave is no longer playing tennis. All the functions the brain has to do to play tennis are lost as well. For example, tennis players have to—very rapidly—process a lot of visual information. Included are speed and spin of the ball, the momentum of the opposing player, racket angle, court lines, the net, and so on. Tennis involves a lot of visual processing by the brain. Again, because of the stroke, Dave is not playing tennis anymore. You can guess what happens to the vision area of Dave’s brain; it too goes through a “pruning of the dendritic arbor.” This process is known as diaschisis.

Not only does the core die, but through learned nonuse the penumbra and many other parts of the brain (diaschisis) suffer as well.

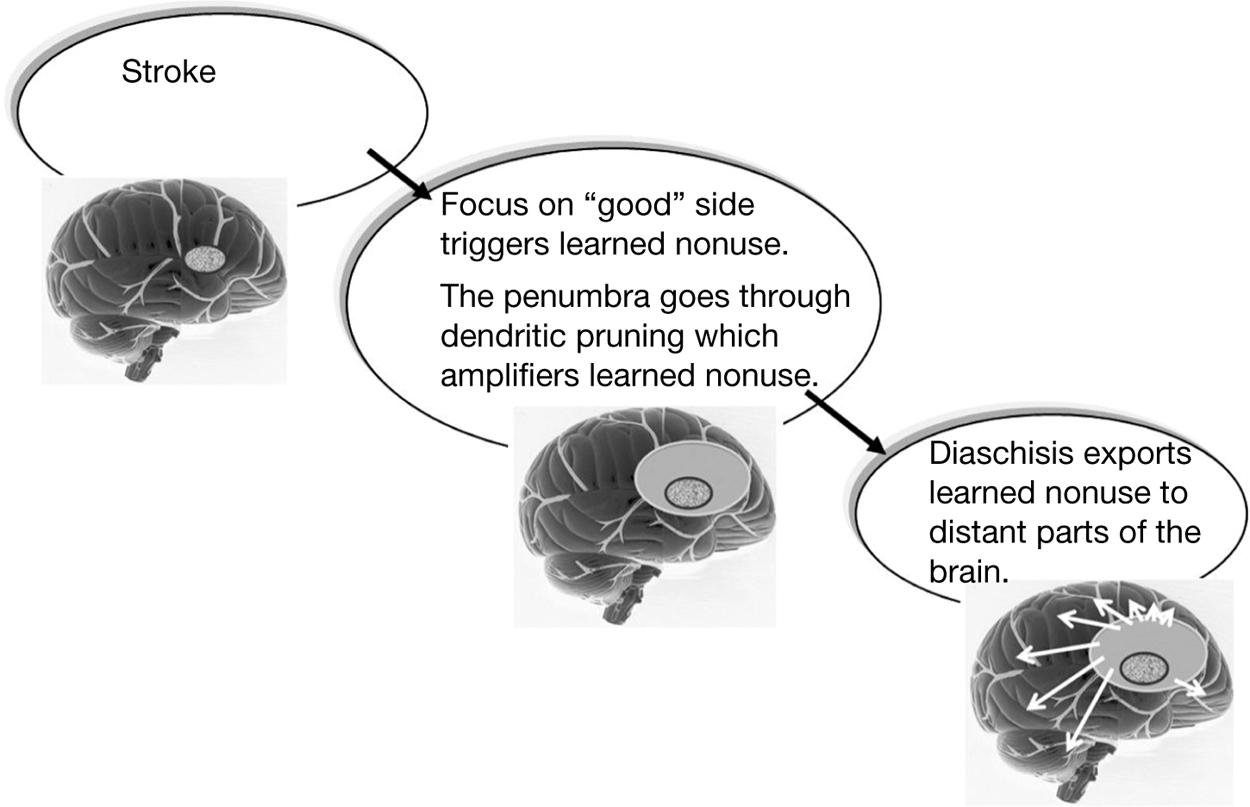

156The cascade of learned nonuse looks like this:

Simply:

• Stroke: The survivor has a stroke. A small portion of the brain (core) dies and is forever gone.

• Learned nonuse: The penumbra that surrounds the core is not used and lies fallow for the rest of the survivor’s life.

• Diaschisis: The negative effect of the stroke and learned nonuse is exported to distant parts of the brain

As you can see, the key to recovery is to not drag the entire brain down with the stroke. The best strategy to keep as much brain as possible is to not let learned nonuse be … learned. And the best way to do this is to engage the penumbra as it comes back “on line” (during the subacute phase).

As the subacute phase ends, the chronic phase begins. The chronic period starts when all the neurons of the penumbra are either “working” or “lazy.” At this point, the survivor has no more spontaneous recovery. Therapists recognize this point in recovery—it’s relatively easy to see. The survivor is no longer recovering. Clinicians call this a plateau. Because of the pressures of managed care (insurance), therapists are required to discharge (end therapy with) survivors who have plateaued. The thinking is “This patient is not making any progress. Why are we paying for more therapy?”

157For many stroke survivors, the plateau may not be permanent. Researchers have found two specific ways of breaking through a plateau during the chronic phase.

1. Getting the lazy neurons to work again

2. Recruiting other neurons in the brain to take over what is lost during the stroke.

Getting Lazy Neurons to Work Again

Reactivating lazy neurons is known as “reversing learned nonuse.” The idea is to challenge the lazy neurons so that they are forced to grow new connections to neighboring neurons—“forced” is the operative word here. In fact, one of the ways to force neurons to develop connections is called “forced use.” Forced use is a part of constraint-induced therapy in which the “good” limb is not allowed to do anything. This forces the “bad” limb to do a lot of difficult and uncomfortable work. But difficult and uncomfortable work is how and why the brain rewires. Brain rewiring (also known as learning) is difficult, from learning a foreign language to learning how to play the violin. The key to learning, including learning after stroke, is challenge. Challenging “lazy” neurons to reach out to other neurons forms new connections between neurons. Getting “lazy” neurons to build connections is one way the stroke survivor has the potential to recover during the chronic phase.

Recruiting Other Neurons in the Brain to Take Over What Is Lost During the Stroke

The brain is “plastic,” and just like plastic you find in everything from car parts to plastic bottles, the brain can change itself physically. For plastic bottles to change form, they need to be heated. For the brain to change it needs challenge. Here is an example of plasticity in play after stroke.

Prior to her stroke, Janice was a florist. Since her stroke she has been unable to move her left hand. Researchers scanned her brain. Sure enough, when she tries to move her left hand, no part of the brain “lights up.” But because of her work she is forced again and again to try to use the “bad” hand. Eventually she gets a small but important amount of movement back. Researchers scan her brain again . . . but what lights up is not what you’d expect.

The brain is backward. The left side of the body is controlled by the right side of the brain, and vice versa. When Janice moves her left hand in the brain scanner, 158the right side of the brain should light up. But it doesn’t. What lights up is the left (“wrong”) side of her brain. In other words, Janice is “borrowing” neurons from her left hand to move her right hand.

Neurons can be recruited from different parts of the brain to do a task they were never asked to do before. That is the power of plasticity and it is a power that survivors can use well into the chronic phase. Challenge recruits unrelated neurons in the brain to take over what is lost during the stroke.

What Is the Best Recovery Strategy During the Chronic Phase?

The following are general rules for recovering during the chronic phase. Note that there are strategies throughout this book that will help survivors make progress during the chronic phase.

• Recovery requires a do-it-yourself focus.

There is a point at which therapists are no longer available to the survivor. Therapists can be helpful at different intervals during the chronic phase (e.g.. every 6 months, every year). Therapists can look at what the survivor is doing and offer suggestions to continue recovery. But therapists are not necessary during the chronic phase. Once therapy has ended, stroke survivors are, and should be, in control of their own recovery. This phase of recovery is based on a lot of self-directed hard work. In order to take charge, stroke survivors need the tools to initiate and follow an “upward spiral of recovery.” The “upward spiral of recovery” is driven by real-life demands for everything from coordination to cardiovascular strength. These real-life demands can be aided by the suggestions given throughout this book. From working on muscle strength to incorporating mental practice, there are many recovery options to choose from during the chronic phase.

• Forget the plateau: It doesn’t happen.

Plateau means “flattening out.” The term is used to describe when it is perceived that a survivor is not making progress. Traditionally, the arc of recovery was believed to have one plateau, at the end of the subacute phase. Research in the last couple of decades has proven that, for some survivors, plateaus can be overcome. During the chronic phase, recovery is made up of multiple plateaus that happen for many years to come. For a full explanation of the plateau and how to bust through it, please see the section Say No to Plateau in Chapter 1.

• Stay in good shape.

Everyone is getting older. As we age, staying in shape is vital to everything, from overall health to allowing us continue to do the activities we love. But survivors have an added energy-burning burden. Basic daily activities (e.g., walking, dressing) take twice as much energy after stroke, and survivors need even more energy because recovery requires effort and effort requires energy. For a full explanation of the importance of and how to maintain heart, lung, and muscle strength after stroke, please see two sections in Chapter 5: Weight Up! and Bank Energy and Watch Your Investment Grow.

• Don’t let soft tissue shorten.

If tissue shortening (i.e., muscle tightness) happens, recovery of movement can be compromised and/or entirely halted. You can do a ton of hard work, but if the muscle length is not there, that’s as far as you’ll go—it’s that simple. This is particularly true of the tendency toward the shortening of soft tissue in the elbow, wrist, and finger flexors in the arm and hand. In the leg and foot, the main concern is the calf muscle. Spasticity in the calf keeps the foot pointed down. If held long enough, the calf muscle will shorten. But many other muscles are at risk as well. For a full explanation of the importance of and how to maintain soft tissue (muscle, etc.) length, please see the section Don’t Shorten in Chapter 3.

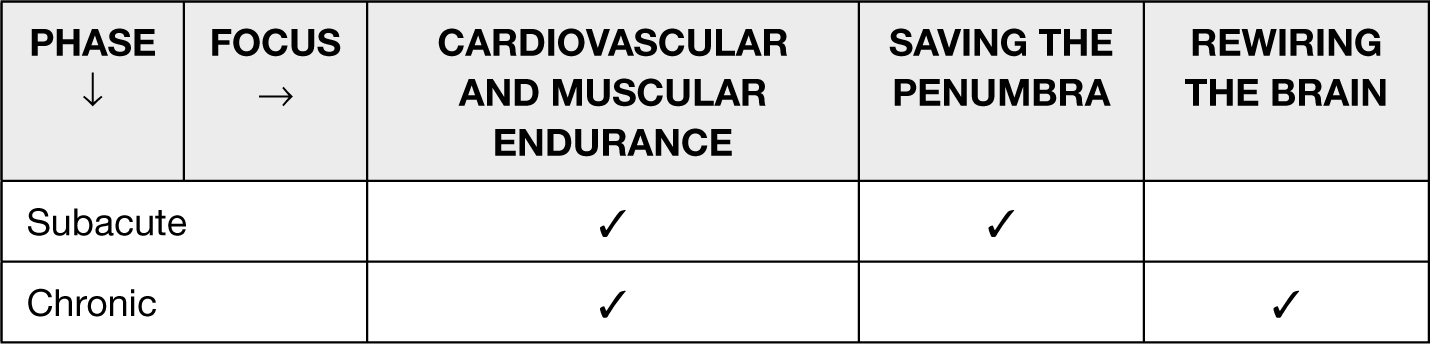

Phase-Focused Recovery

There are three ways that recovery can happen.

Strength is increased: You develop increased muscle strength, and cardiovascular (heart and lung) strength.

• Strengthening should be encouraged during the subacute and chronic phases of stroke.

• Strengthening during the hyperacute and acute phases will hurt recovery.

The penumbra is saved: During the subacute phase the neurons of the penumbra are brought back on line.

The brain is rewired: During the chronic phase brain plasticity allows for a completely new and different area of the brain to take over for lost function.

160Here is a “cheat sheet” for phase-focused recovery:

When Does Recovery End?

“How do I know when I’m done recovering?” This is a legitimate question. It’s a tough one, too. I asked this question of Kathy Spencer, a friend and one of the most motivated survivors I’ve ever met. She puts it this way . . .

I don’t think recovery ever ends. I tell stroke survivors that with the plasticity of the brain—we are never done recovering unless we quit working or die. I still work on things, just not as intensely. I think for me, after working over two years every single day, I felt like I needed and wanted to get on with life—and I have SO much recovery that I’m okay with it. I do fine with motor stuff—type, write, piano, etc., but I could benefit if I did more. I just bought one of those hand grip things to carry in my car to strengthen my fingers while driving, but now I can do so much with my fingers. I can even put in pierced earrings, hook my necklaces, jog, jump, etc.—I just don’t focus on it nearly as much as I used to. So to answer your question—at what point are the efforts toward recovery no longer worth the time—it’s always worth the time, but when you can do so much after not being able to do it for two years—you reach a point of satisfaction but still work—just not as hard! I would never tell a person that working on recovery ends or is a waste of time.

THE SUBACUTE PHASE: RECOVERY’S SWEET SPOT

_______________

Terms you will need to know to understand this section . . .

Penumbra: A viable area of the brain next to the area killed by the stroke. The penumbra is much larger than the area killed by the stroke and represents billions of neurons. These are neurons that survive stroke, but their usefulness remains the question. The subacute phase will decide that question.

Neurons: The nerve cells in the brain that allow you to think and move.

161Neurons “on line” and “off line”:

• On line: Neurons alive and working

• Off line: Neurons alive but not working

Subacute: The point at which the neurons of the penumbra come back on line.

Spontaneous recovery: Recovery that comes with little or no work.

Intensity: The amount of energy, strength, concentration and time put into rehabilitation.

The subacute phase is the most important to recovery after stroke—so much can go right and so much can go wrong.

• What can go right:

— The neurons that survive the stroke are used and so become useful.

• What can go wrong:

— The neurons that survive the stroke are not used and so become useless.

The area in play is called the penumbra. During the subacute phase, neurons of the penumbra can either be used or not used.

• Prior to the stroke, these neurons may have been involved in anything from opening the hand to controlling the muscles of the mouth during speech. Neurons that are used (and therefore useful) respond to that use by accepting these pre-stroke responsibilities.

• Neurons that are not used lose their connections to other neurons (and are therefore useless). They are still alive, but they are isolated. Neurons work together in large groups to help you move, speak, think, and so on. Neurons that are isolated can do very little to help those tasks.

The penumbra can either be “turned on” or “turned off.” The subacute phase is the best time to turn the penumbra on. Turning on the penumbra will help achieve the highest level of possible recovery.

Of all the phases of stroke, the subacute phase involves the hardest work, and the biggest payoff. Think of the subacute phase as recovery’s “sweet spot.” Taking it easy during this phase will expand the impact of your stroke and will 162decrease overall recovery. Working hard during the subacute phase is critical to having the brain reach every last bit of its potential.

There are two keys to getting the most from the neurons of the penumbra:

1. Using the neurons of the penumbra

2. Timing the use of the neurons of the penumbra

As the neurons of the penumbra come back on line, using those neurons is key to optimal recovery. The other key is the timing of the use. Neurons of the penumbra stressed into use too early (during hyperacute and acute phases) can limit recovery. If stressed into use too late (during the chronic phase), the impact on recovery will be limited.

How Is It Done?

Let’s say Mr. Smith has had a stroke. He has gone through the acute phase and is medically stable. He, his therapists, and his wife all notice that he seems to be getting movement back every day, and the movements seem to be coming back without much work. This is a clear message: The neurons of the penumbra are coming back on line. This sort of recovery (movement coming back with little or no effort) is called spontaneous recovery. Spontaneous recovery alerts you that the subacute phase has begun.

When you begin to see spontaneous recovery, it’s time to “put the pedal to the metal.” The problem is, you may not be considered “subacute” when spontaneous recovery arrives. Every stroke is different, every stroke survivor is different, and every recovery is different, so you may be in “acute care” when you’re in the subacute phase. It is important for survivors, caregivers, and healthcare professionals to recognize the signs of spontaneous recovery. Spontaneous recovery indicates the subacute phase, and is an indication that serious efforts toward rehabilitation should begin.

Unfortunately, the subacute phase has a couple of forces working against it:

1. Therapists are under very strict orders by neurologists and physiatrists during the acute phase. Therapists are limited in how much and how intensive therapy can be. And this is a good thing. Too much too soon can hurt recovery; this much seems clear in both human and animal studies. The problem arises when the survivor is considered “acute” when he or she is actually in the subacute phase. In other words, there are two distinct phases with two contradictory rules:

• Acute: Don’t do too much or be too intensive.

• Subacute: Turn up the amount and intensity.

Again, this is why recognizing the subacute phase by recognizing spontaneous recovery is so important; it will alert you to what phase you are really in.

2. Therapists are restricted as to the amount of therapy that is paid for by insurance (managed care, Medicare, etc.). This perspective is often referred to as “meet ‘em, greet ‘em, treat ‘em, and street ‘em.” That is, managed care (insurance) requires that therapists get survivors . . .

• Safe

• Functional

• Out the door

All three (safe, functional, and out the door) are important, of course. But many of the efforts to satisfy “safe, functional, and out the door” involve compensatory strategies (or, simply, compensation). Compensation is using the “good” side to “get on with your life.” This can lead to learned nonuse, which describes what happens in the brain when the undamaged side is used and the damaged is not used. Briefly, the less you move the “bad” side of the body, the less of the damaged side of the brain is used. And the parts of the brain that are not used, much like muscle that is not used, get weaker. With compensation, the undamaged side of the brain gets stronger, and the damaged side of the brain gets weaker. This is the opposite of what you want to have happen. You want the damaged part of the brain to be challenged and grow stronger. But you have less time to work on the damaged side when the emphasis is on getting the undamaged side to do almost everything (compensation). There are not enough hours spent in rehab to work on “function” while also working on recovery. Getting the most out of the subacute phase typically involves more—more focus on the affected side, more intensity, and more hours per day focused on recovery. But there is a bit of good news . . . Much of recovery is done when the therapist is not there. Repetitive practice of the movement that you have, mental practice, engaging in conversations and social interactions (enriching your environment), as well as many other techniques, can be used to aid recovery even when therapists are not around. 164This will help the damaged part of the brain grow stronger, which will make movement easier and better.

How do you recognize when spontaneous recovery begins? How much intensity should there be during the subacute phase? Here are some questions and answers to help you understand this critical phase of recovery.

Q: When does the subacute phase begin?

A: When there is spontaneous recovery.

Q: What is spontaneous recovery?

A: Recovery with no work.

Q: How can you recover with no work?

A: Neurons of the penumbra rush back and become usable.

Q: What does spontaneous recovery look like?

A: Movement and sensation that were not available one day become available the next.

Q: Can spontaneous recovery be anything other than movement or sensation?

A: It may be anything from regaining speech to remembering your phone number for the first time in days.

Q: Provide a specific example of spontaneous recovery of movement.

A: You can’t move your foot at the ankle on Monday, but on Tuesday you can move it up and down noticeably.

Q: Who is most likely to see spontaneous recovery?

A: The survivor or a caregiver, but it could be a physical therapist, occupational therapist, speech therapist, a doctor, or a nurse.

Q: Why do you mention the survivor and caregivers before the health professionals?

A: Survivors are the most aware about what is going on with their body. Caregivers spend the most time with survivors.

Q: Who do I tell if I observe spontaneous recovery?

A: Everyone, but especially therapists.

Q: Is spontaneous recovery ever too subtle to be observed?

A: Yes, but if you suspect something is changing, tell the therapists. They have tools to measure even the slightest amount of movement or increase in strength.

Q: Once I recognize the subacute phase, what should be done?

A: Ease yourself into more intensive stroke recovery options, and slowly increase the number of hours per day spent on recovery.

Q: Why is it important to “ease into” more intensity and more time?

A: There are two reasons: (1) The brain is still somewhat vulnerable during this period. Easing into increases in intensity will help the brain adjust accordingly. (2) Because of the stroke and all the things that come from stroke (more medications, difficulty with movement and communication, etc.), the amount of energy the survivor has to recover is limited. Therefore, it is wise to incrementally increase the amount and intensity of efforts toward recovery. As more energy becomes available, more time can be put into recovery efforts.

Q: What can stand in the way of the neurons of the penumbra completely coming back on line?

A: Not enough energy, strength, concentration, and time put into rehabilitation during the subacute phase.

Q: If time with the therapist is limited, how can I ensure that the neurons of the penumbra are challenged?

A: Accept that the person in the best position to reengage the penumbra is the person who has ownership of the brain in question: the survivor.

Q: If the responsibility of the penumbra is up to the survivor, what are some specific strategies that will help keep the neurons of the penumbra engaged?

A: Please see the next section entitled Expanding the Therapeutic Footprint.

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

Hard work is important to capture the potential of the penumbra. But the brain—as well as other body systems—can be vulnerable during this period. Healthcare workers, including doctors, nurses, and therapists, can provide insight into what is safe and what is not.

166EXPANDING THE THERAPEUTIC FOOTPRINT

_______________

Recovery requires a lot of time. It is unrealistic to think that healthcare workers will be there during all of that time. Consider the entire time recovering as the “arc of recovery.” The arc of recovery extends from the first symptom of stroke to the highest level of recovery achieved. During the arc of recovery, you will spend a lot more time without professional guidance than you will with it. Physical and occupational therapists, for instance, will be there a small percentage of the total time it takes to recover. The amount of time spent with therapists will be limited in two ways:

1. When you are in therapy you will see therapists for a few hours a day, at most. (What should you do when the therapist leaves the room?)

2. Therapy typically lasts until the beginning of the chronic phase. (What can be done to recover “for the rest of your life?”)

Therapists don’t need to be there most of the time. What you do on your own will define the extent of your recovery. Survivors have control over their own nervous system, and that nervous system will respond to their hard work. Therapists can’t do it for you. Therapists are coaches; they provide guidance. Such guidance can be used to inform efforts toward self-driven recovery.

How Is It Done?

Question: What can you do when the therapist is not there? Answer: A lot. I call this idea “expanding the therapeutic footprint.” This is a fancy way of saying “use what therapists suggest, even when they’re not around.” The concept of recovery is relatively simple. Putting into play relatively simple concepts will go a long way toward helping your overall recovery, and therapists will love it too. Most therapists get into the business because they want to help people recover. The more hard work you put in, the more rewarding the experience for both of you.

Here are some suggestions to expand the therapeutic footprint . . .

Use Electrical Stimulation (e-stim)

For most survivors, e-stim can be an easy “do-it-yourself” tool for recovery. E-stim can be used to:

• Temporarily reduce spasticity and provide a stretch to spastic muscles

• Help regain sensation on the “bad” side

• Maintain muscle size (bulk) by forcing muscles weakened by the stroke to flex

• Reduce the chance of blood clots (deep vein thrombosis—DVT) in the calf muscle

Reduce shoulder dislocation (called subluxation). Shoulder muscles can become so weak after stroke that the shoulder joint can no longer hold the weight of the arm. This causes the shoulder to dislocate. (See the section Shocking Subluxation in Chapter 4. Also in Chapter 4 is the section Electrical Stimulation for Frugal Dummies, which provides information about how to use e-stim to help “jumpstart” recovery.)

Physical, occupational, and even speech therapists have been using electrical stimulation (e-stim) for decades. There are many uses for e-stim after stroke, from pain relief to muscle building. But the most important use of e-stim for stroke survivors is this: E-stim changes the brain. Brain-scanning studies have shown that e-stim affects the brain after stroke even before the survivor has any muscle control. E-stim can be used to “re-engage” the brain to begin the process of regaining control of muscles. Because it changes the brain before the survivor has control over muscles, e-stim is a great bridge between no movement and some movement. There’s a huge difference between “no movement” and “some movement.” Small amounts of movement are vital, giving you a fighting chance to regain even more movement. See how in the next section.

Use “Non-Functional” Movement (NFM)

“Non-functional” movement (NFM) is movement that does not help any real-world task. For instance, if a survivor can open and close his or her hand a little bit, but not enough to pick anything up, that movement is considered NFM. NFM can be movement that is too small, weak, or uncoordinated to do any real-world task. While NFM may not help any task, it is vital to recovery. There is a tendency for both healthcare workers and survivors to assume that NFM is not important. The attitude is, “It does not help you do anything, so why do that movement?” This is a mistake. The brain regains control over muscles when those muscles are moved, but if “non-functional” muscles are never moved, how will the brain ever learn to move them better? This is why, when you are not in therapy, it helps to use any NFM you have. 168The movements should be repetitive, and challenging. For instance, let’s say you have a small amount of movement toward opening your hand. That small amount of movement can be expanded by repetitively using that movement. Focus on challenge by “nipping at the edges” of your current ability. For instance, if you can open your fingers wide enough to pick up a marble, work on opening them wide enough to pick up a ping pong ball. The “off-line” time that you are not in therapy is the perfect time to work on the difficult task of regaining brain control over muscles. And if you do this work when you are not in therapy, it is a win-win-win-win!

• WIN: You save yourself money by not burning through valuable therapy time to do the “grunt work” needed to increase small amounts of movement.

• WIN: Therapists can use the gains you have made on your own to expand the options they can use during actual therapy time.

• WIN: Therapists can use the gains you have made on your own to justify more therapy.

• WIN: You learn recovery from “the inside out.” What you learn while you’re with the therapists will help you recover once therapists are no longer around.

Make the Home Exercise Program (HEP) Immediate and Ongoing

Most of the time the home exercise program (HEP) is an afterthought. It is usually a series of exercises that is given to the survivor once it is believed that recovery has ended. The HEP can be a very powerful tool for recovery. Here are two problems with the typical HEP and two suggestions to make the HEP a more potent tool for recovery.

Problem 1: The HEP is given at the very end of therapy. It’s usually one of the last things that’s addressed just before the survivor is discharged (the point at which therapy ends).

Solution: Instead of making the HEP something that’s dealt with at the end of therapy, it should be initiated at the beginning of therapy. That is, the survivor would benefit from a structured set of responsibilities even during the early phase after stroke (acute). It may be worthwhile to look at the HEP as something other than simply an “exercise program.” It can be a set of suggestions that can benefit recovery, even if the therapist is not in the room. For instance, the HEP may include the suggestions 169made in this section (using mental practice, reinforcing the importance of sleep, engaging in conversations, etc.).

Problem 2: The HEP is usually designed to help the survivor maintain any gains achieved in therapy. The HEP is not typically designed to help the survivor achieve new gains.

Solution: In the section entitled Get a Home Exercise Program in Chapter 5 are suggestions for the HEP that will help you to continue to make gains, not simply maintain a plateau. (See Chapter 5 more suggestions for the HEP).

Listen to Music

Survivors that listen to their favorite music do better, in many ways, than those who don’t listen to music. The benefits of listening to music after stroke are numerous and include . . .

• Better verbal memory (important for survivors who are aphasic)

• More focused attention (important to every aspect of recovery from stroke)

• Improved mood (50 percent of survivors suffer from depression after stroke)

For the best results, start listening to music within the first ten days after stroke. Listen to music that you choose (your favorite music). In research, survivors listened to music at least one hour per day for two months. Study participants started listening to music between five and eight days after their stroke.

Encourage Sleep

Adequate sleep benefits every aspect of recovery. This has been shown to be true in both human and animal studies. Please see the section entitled Horizontal Rehab: Good Sleep = Good Recovery in Chapter 5 for strategies to promote sleep.

Enrich the Environment (EE)

There are many animal studies that show that an “enriched environment” (EE) benefits all aspects of recovery from stroke. There are also an emerging number of human studies that show the same.

170So what makes up an EE? Here’s the good news: What is considered an EE tends to be fun. Activities that promote an EE include . . .

• Physical activity

• Emotional stimulation

• Conversations

• Social interaction

• Playing games

What does an EE do for stroke survivor? An EE . . .

• Aids in the recovery of movement

• Improves thinking

• Drives helpful neuroplastic (brain rewiring) in the brain

• Reduces for everyone, including stroke survivors, the natural shrinking of the brain that comes with age

Use Mental Practice (MP)

Movements and skills you’re trying to relearn after stroke benefit from practice. The practice you do with therapists and on your own is actual practice. You can increase the strength of actual practice with mental practice (MP). MP involves imagining whatever skill you’re doing during actual practice. MP, its setup and usage is fully described in the section Imagine It! in Chapter 4.

MP is simple. Imagine doing a skill you’re trying to recover the way you did it before the stroke. MP is done on your own, in a quiet environment. It takes no physical energy, and is done without a therapist, so it is a perfect way of expanding the therapeutic footprint.

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

The precautions for expanding the therapeutic footprint are treatment-option specific. That is, the precaution would depend on what it is that you’re trying to do. It is always wise to ask the appropriate healthcare professional for guidance. These professionals will not only help you make these techniques safer, but they can provide valuable suggestions in making these techniques stronger.

171THERAPY SOUP—MIX AND MATCH

_______________

Some things are just better together: wine and cheese, baseball and beer, good friends. One option at a time can work well, but sometimes adding a second (or third, or fourth . . .) option can magnify and complement both. The same is true of recovery options. These recovery options include:

• Treatment techniques

• Interventions

• Modalities

• Therapies

• Exercises

• Technologies used for recovery

• Any other effort made toward recovery

How Is It Done?

Mixing and matching (recovery) options is a little like cooking soup. When you cook soup, you taste as you cook. As you add and subtract things to your recovery mix, “taste” the effectiveness of your mix of options.

Adding new options can keep things exciting and, if done correctly, can amplify the efficiency of your recovery routine. The trick is adding a new element and then accurately evaluating if the new element provides a benefit. Finding the correct mix is part science, part art, part intuition, and part experience. There are no rules or flowcharts to direct you through the process of deciding if, what, and when a set of recovery options works.

Some variables that you need to consider when mixing and matching therapies include:

• Dosage: Most people think of dosage as something that relates to drugs, but recovery options have dosages as well. Dosage is simply the “how much” of the option you’ve chosen. Dosage is defined by:

— Amount of time. This would include the amount of time and the number of times per week you spend doing the option. For instance, if you and your doctor have decided that electrical stimulation helps reduce your spasticity, then the amount of time that you have the stimulation on would help determine the dosage.

— Intensity: Again, using electrical stimulation as the example, the level of stimulation (usually measured in milliamps) would help determine the dosage.

• Type of stroke:

— For example, an option may be safe and effective for someone who had a “block” stroke (ischemic, where the blood vessel was blocked). The same option may not be safe for someone who has had a “bleed” stroke (hemorrhagic, where a blood vessel has burst).

• Side (left or right side of brain) of damage and if the stroke affected the dominant side:

— For example, trying to use repetitive practice during writing when it is your nonwriting hand that is affected, would not be helpful to recovery.

• How long after the stroke it has been:

— Some options work well right after the stroke. Other options are best tried once you are in the chronic (several months to one year after stroke) stage of recovery.

• The amount of spasticity you have:

— If spasticity is strong, it is sometimes wise to focus on options that reduce spasticity before starting other options.

• The type and number of conditions related to the stroke:

— For example, eyesight problems, loss of feeling, spasticity, aphasia, and so forth.

• The type and number of health issues that are unrelated to the stroke:

— For example, diabetes, heart problems, depression, and so on.

• Your motivation level:

— Some options take a tremendous amount of focused effort. You may not be willing to make that effort, sometimes for understandable reasons (“I have grandchildren to take care of; I don’t have time!”). Even if an option is something you do not want to consider, that does not mean that your efforts should end. It simply means that different options should be explored.

• The amount of movement you have:

— For instance, options that are effective for someone who has near-perfect movement may not be appropriate for someone who is completely limp on the affected side.

The list of variables continues extensively. There are so many considerations in stroke recovery that it is impossible to develop a perfect system to guide you through the process, and even if there were, new research, technologies, and techniques are developed every day. This makes the situation so fluid that the best advice is to always consider new options and accurately and regularly assess progress.

• Always include options that challenge you: No progress comes from simply doing what you can. Recovery comes from continually striving for what you are not yet able to do.

• Consider technology: The future of rehabilitation is technology. Why? Because there are 50 million stroke survivors worldwide, and the profit motive is too great for inventors to overlook. Fortunately, this means that inventors spend an enormous amount of money on stroke-recovery research. Keep your eye out for emerging technologies to add to your options.

• As much as you can, choose options with a direct impact on what you love to do: The part of your life that you most want to get back is a powerful motivator.

• Always include aerobic (heart and lung) exercises into your mix of options.

• Look for options that do well in clinical research: See the Resources section for easy ways to find out what researchers reject and support.

• Emphasize options that you can do safely by yourself, at home.

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

If you take two or more perfectly safe therapies and add them together, they can become dangerous. For instance, imagine if you decide to follow aqua (pool) therapy during the same arc of time that you are doing treadmill training. The two forms of exercises may work well together, but in the short term, they represent a large increase in the amount of stress on your muscles. If you neglect to take into account the increased fatigue that the aqua therapy adds, 174these two therapies can be dangerous. For example, imagine getting out of the pool, getting dressed, climbing on the treadmill, and then falling because of fatigued arms and legs.

Keep your doctor informed about changes in your recovery options.

LIFESTYLE AS THERAPY

_______________

There are not enough hours in a day to accomplish what you need to do while working the full-time job of recovering from a stroke. However, there are errands, chores, and everyday tasks that can be done in a way that promotes recovery. Sure, daily tasks will take a bit longer, but think of the time and money saved if recovery efforts and everyday chores are combined!

Incorporate recovery efforts into the natural rhythm of your life. For instance, within the boundaries of safety, take the stairs, walk to the store, and use the affected hand to do everything from turning the pages of the newspaper to playing catch with grandchildren. Folding clothes is an excellent way to incorporate bilateral training (see the section The Good Trains the Bad—Bilateral Training in Chapter 4). Putting away silverware is a good way to work on repetitive practice of grasp and release of the hand. Accomplishing simple tasks while focusing on the affected extremities will help improve overall coordination, skill, strength, and functional ability. It is important to understand how valuable everyday tasks are to your recovery. Research has three buzzword concepts that form the foundation of all recovery:

• Repetitive: Doing the movements that you want to relearn over and over

• Task specific: Having recovery efforts center on specific, real-world tasks

• Challenging: Work on tasks that are challenging—as challenging as you can tolerate within the limits of safety

You can see how using everyday tasks as therapy has the potential to incorporate all three of these concepts.

How Is It Done?

Clearly, the best way to improve walking after stroke is to walk a lot (see the section Walking Your Way to Better Walking in Chapter 8). What if you walk to the store, library, or school? For instance, books have to be returned to the 175library, which is five blocks away. Certainly it would be faster to take the car, but the walk has inherent therapeutic value. Walking is a great exercise and can be naturally incorporated into your lifestyle.

A task like putting away groceries is a great way to do everything from challenging balance to practicing hand grasp and release. Forgoing the elevator for the stairs challenges you by asking for a large amount of lift at the ankle. Painting helps movements at the wrist, elbow, and shoulder, even if you need to place the brush in your “bad” hand with help from your “good” hand. For someone who loves to paint, painting is an example of a meaningful activity. Research has shown that the more meaningful the activity is to you, the more recovery that activity will promote. Some activities are meaningful to everyone, such as walking, eating, and bathing. Other activities have a special meaning to people with special passions, such as playing a musical instrument, playing golf, or painting.

The trick, of course, is taking the extra time needed to fully incorporate the affected arm and leg into whichever task you choose. Taking extra time for these tasks will also help you stay safe. Rushing will hurt everything from coordination to balance, so take your time for the sake of quality of movement and your own safety.

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

Stroke survivors should challenge themselves with everyday tasks. However, it would be wise to always question the safety of attempting even the simplest of tasks. For instance, even a walk to the end of the block can be dangerous if you fatigue easily or you’re prone to falling. Reaching up to put a cup in a cupboard may help activate grasp and release, challenge balance, and improve coordination, but this same task can be dangerous if you lose your balance. Stroke survivors should be aware of the dangers of pushing themselves into new and challenging tasks, including inherent dangers from loss of balance, falls, spikes in blood pressure, and so forth.

YOUR WORK SCHEDULE

_______________

Studies have shown that, in hospitals, stroke survivors spend just over an hour per day involved in recovery efforts. In skilled nursing clinics, where many stroke survivors end up after their hospital stay, the situation is not 176much better. The amount of time paid for by Medicare for all therapies, combined, is just over two hours per day, but in order for the brain to rewire, much more time is needed for recovery of movement. For instance, traditional constraint-induced therapy, which is proven to promote recovery, has patients do six to eight hours a day of therapy! Recovery efforts are more effective when they are done many hours a day. The brain rewiring needed to recover can happen during short bursts of time, measured in number of weeks (one to ten weeks), but the number of hours per day should be as high as you can tolerate.

How Is It Done?

You can tell how much time per day to spend on recovery with a simple test: How much time does it take to get really good at any skill you’ve ever acquired? Many of the skills and abilities that we’ve acquired throughout our lives take years of dedicated practice, and we are happy to do it because we are acquiring a new skill. Stroke recovery has the disadvantage of not involving any movement or skill that is new. You are simply relearning what you once knew how to do well. Still, the challenge of recovery can be exhilarating, but only if you are willing to put in the work and the time needed to show results.

The optimal amount of time that should be spent on any given treatment, exercise, or modality is one of the hot topics of stroke recovery research. Deciding the exact amount of time to spend on recovery efforts can be tricky. It is, however, safe to say that dedicating enough time to recovery can be summarized with the phrase: Recovery is a full-time job.

Of course, doing eight hours of work may sound exhausting. Your recovery plan should include options that mix hard physical work with restful work, like mental practice (see Imagine It! in Chapter 4). Always balance between work and rest and between maintaining challenge and safety. Often you will not have to do a particular therapy for a long duration of time, as measured in weeks, months, or years. You might instead have an intense experience with a recovery tool for relatively short bursts (two to three weeks) of time. Of course, if a recovery option works for longer than that, keep doing it. On the other hand, if a therapy loses its effectiveness or does not work in a relatively short amount of time, then pitch it. Worthwhile therapies tend to show pretty immediate results. Results have to be measured to determine effectiveness. For suggestions on measurements, see the section Measuring Progress in Chapter 1.

177Many stroke survivors are reluctant to put considerable amounts of time into recovery without the guarantee of gains, and there are no guarantees. You may work very hard and recover very little. Efforts toward recovery are a leap of faith. Much of what we do involves leaps of faith, from raising children to getting an education. A full life is full of leaps of faith. Stroke recovery is another leap. Keeping the faith is essential to recovery.

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

The exact amount of effort toward recovery is a decision to be made by the stroke survivor and his or her doctor. Doctors are experts at determining how much work is safe. A balance should be reached between effectively challenging the stroke survivor without pushing him or her to the point of exhaustion. Overexertion will lead to diminished recovery and, finally, to discouragement and quitting.

LIVING RECOVERY

_______________

What do you remember from your childhood? Usually it’s one of two types of experiences: something good or something bad. Your first kiss and a broken wrist are examples of memories that come back as crystal clear as a photograph. These experiences tend to “hard-wire” into the brain because of their intensity. They have a deep impact that makes you remember the sights, sounds, and emotions of the experience. Intense memories are actually physical in form. They are the connection of particular brain nerve cells firing in a particular order. Think of rehabilitation in much the same way.

When the act of recovery becomes as intense an experience as possible, recovery from stroke can shift into high gear.

How Is It Done?

The more of the whole person, heart and soul, is committed to the movement, the more that movement will be learned. Intensity of emotion and depth of experience can promote recovery by “hard-wiring” the experience. Doctors on the cutting edge of stroke recovery research talk about patients “driving their nervous system” toward recovery. How can a stroke survivor drive their nervous system, in this case, the nerve cells in the brain, toward recovery?

• The effort should be essential, meaningful, and passionate. Think of recovery as a challenging vision quest.

• With each instance of committed effort, the brain is slightly altered toward recovery.

• The effort has to be strong enough, focused enough, and personally powerful enough to drive change.

• Any athlete or musician will tell you the same thing: You have to live it.

• When working toward recovery, effort has to be as intensely experienced as you can make it within the limits of safety.

There are many ways that people use depth of experience to change their lives. The experiences at retreats and camps, for example, can change you in profound ways in relatively short periods of time. Consider these two experiences:

• Joe plays two hours of basketball, every Saturday, for a year. That’s a total of 104 hours of playing time.

• Jim goes to basketball camp for two weeks and plays for seven hours a day. That’s seven hours a day for 14 days, for 98 hours of total playing time.

So Joe, the “weekend warrior,” plays for a total of 104 hours and Jim, the “camper,” plays 98 hours. Most researchers now believe that Jim the camper would get better at basketball because he would be much more immersed in the experience than Joe. Jim’s camp would make him a better basketball player because of the rich emotional experience, which is, quite literally, imprinted on his brain.

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

Any time one considers any difficult physical endeavor, whether it’s running a marathon or dedicating fully to recovery from stroke, the precautions are the same: Keep your practice within safe boundaries. There is an old Clint Eastwood line, “A man’s got to know his limitations.” This is true for anyone trying to recover from stroke. It’s a recurring theme in this book: intense, strong, serious, and, most importantly, safe. Consult your doctor about any effort in your recovery that you are unsure about.

179KEEP THE CORE VALUES CLOSE

_______________

This book, like any book, can be a reference because it is permanent. Read it, and then put it on the shelf to refer to when you need it. The fundamental recovery principles should be memorized and more than memorized; they should become an intrinsic part of the recovery process. Much of recovery you should “feel in your bones.” You already do feel it, although recovery may not seem natural. If you’ve ever challenged yourself to learn a new skill, you already know the process of recovery. Whether you’ve had a stroke or not, you have the ability to profoundly change your brain. If you are a survivor, you can use the same drive you had all your life to propel brain change. Survivors will benefit from a particular set of core values as they continue on their neuroplastic journey. Keep this book close by on a shelf. Keep the core values in this book closer.

How Is It Done?

The basic elements of successful recovery from stroke are remarkably simple. Here is a quick core values cheat sheet of stroke rehabilitation:

• Develop a plan.

• Don’t accept that there will be no more significant recovery.

• Continually research new recovery alternatives.

• Incorporate tasks that are meaningful to you into your recovery efforts.

• Use affected “bad” extremities as much as possible.

• Exercise is good.

• Strengthen your muscles.

• Strengthen your cardiovascular system.

• Stretch often.

• Control your weight.

• Treat efforts toward recovery like a full-time job.

• If you can, walk a lot.

• Take every precaution not to fall.

• Within the boundaries of safety, always challenge yourself.

• Measure progress often.

• Fall in love with the process of recovery.

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

Common sense and your doctor should be your guides.

HARD BUT SAFE

_______________

Efforts toward recovery should extend you beyond your current ability while remaining safe. This balance is not difficult to achieve, but does require some planning and consultation with your doctor and other healthcare providers.

When developing a strategy for recovery from stroke, ask yourself two basic questions:

• Is it safe?

• Is it challenging?

If it is safe but not challenging, it will not produce results. If it is challenging but not safe, there is a risk of injury. Pick recovery options that are physically challenging but have little risk.

How Is It Done?

Some inherently dangerous therapies can be modified to make them safe. An example of this is cardiovascular (heart and lungs) training. You could try to swim, attempt to walk briskly, or ride a bicycle. All of these are healthy for your heart and lungs, but they are all dangerous for some folks who have had a stroke. On the other hand, you can modify any recovery option to be safe. For instance, you can change swimming to aqua therapy (therapy done against the resistance of water), and you can use a stationary recumbent bicycle instead of a regular bicycle. Consider walking. Walking is one of the best, if not the best, cardiovascular workouts. If there is a risk of falls or if you are unable to walk, develop a cardiovascular workout that is done in the sitting position. Suggestions for cardio training in the seated position include “ergometers” 181(stationary cycles for the arms or legs) and recumbent steppers. See Chapter 9 for further examples of machines that help with a cardiovascular workout and that use the legs but do not involve walking. Once you are able to stand, walking can be done with your weight supported or on a treadmill with bars to hold. The worst thing to do, of course, is to assume that walking safely is a lost cause. Giving up on any skill (like walking) may well guarantee more than just losing that skill. It may also provide an opportunity for a downward spiral. Lowered expectations lead to less activity, which leads to less strength and stamina, which, in turn, lead to even lower expectations. Workouts designed to increase heart and lung stamina as well as strengthen muscles will help build the foundation needed to walk safely again. There are other “preambulation” techniques that can be used to foster walking, like partial weight supported walking, the NeuroGym® Bungee Walker, and the Biodex Unweighing System.

The “hard but safe” idea is a cornerstone of rehabilitation therapy and rehabilitation research:

• Hard (challenging): All recovery comes from challenge. In many ways, all recovery is “forced.” You put yourself in situations where you can barely achieve the goal, and the challenge itself drives recovery. The irony of stroke is that the deficits left by the stroke provide the perfect challenges needed to come back from the stroke. Stroke survivors and well-meaning clinicians often spend much of their effort trying to eliminate the challenge. The saddest situation is when stroke survivors cannot challenge themselves because they don’t understand the importance of the challenge. In other cases, survivors are so flaccid (limp) on the affected side that they can’t even begin to attempt to meet the challenge. Sometimes stroke survivors who are asked to move their fingers (or wrist or foot, etc.) deny that they have any movement. A concerned doctor might say, “Humor me, and give it a try,” and sure enough, there is movement. Not much movement, but enough to apply repetitive practice, rewire the brain, and begin an upward spiral of recovery. Challenge feeds recovery. Recovery feeds on challenge.

• Safe: There are two reasons to stress safety:

— Injuries are bad; everyone knows this, and everyone knows why. A simple slip and fall can lead to a broken bone, a hospital stay, a pressure sore, and even death.

— Injuries stop recovery. The threshold for an injury that stops recovery is much lower than anything that involves a hospital stay. A torn muscle, a sore back, or a bruise can slow or stop recovery efforts.

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

Inherent in designing an effective rehabilitation program is a commitment to new and challenging areas of physical experience. This is as true with stroke survivors as it is with athletes, musicians, dancers, and other individuals who use their bodies to express themselves, pursue their passions, and make their living. The trick for survivors is to make the rehabilitation efforts both challenging and effective while remaining safe. Consulting your doctor and involving physical, occupational, and other healthcare providers will go a long way in maintaining the safety/challenge dynamic.

EAT TO RECOVER

_______________

Diet has huge implications on so many levels for everyone. Diets impacts . . .

• The development and recovery from diseases like diabetes, heart disease, and diseases of the blood vessels

• The immune system

• Mental acuity

• Quality of life

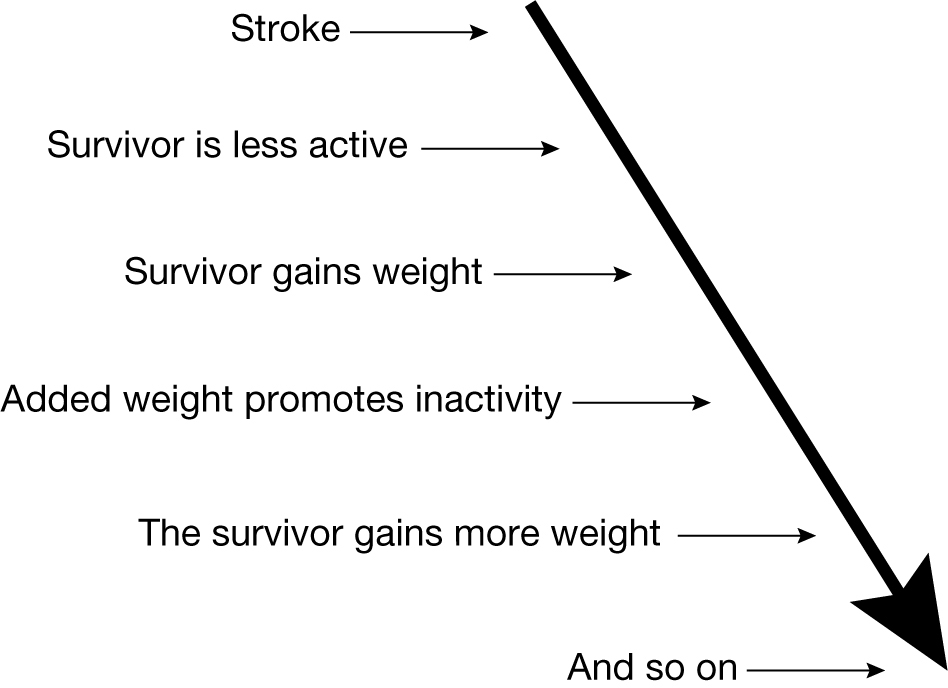

The impact of diet on survivors is even larger than on the general population, because diet affects so many aspects of recovery. For instance, diet affects energy levels, physical performance, mood, cardiovascular health (stroke is a cardiovascular disease), and muscle strength. And, of course, diet affects weight. The less you weigh, the easier it is to move. The opposite is true, as well; the heavier you are, the harder it is to move. Weight gained is weight that has to be lifted during movement. The heavier a stroke survivor is over optimum weight, the more difficult the path to recovery. Stroke survivors tend to cascade toward weight gain. In some folks, stroke initiates a downward spiral that might look like this:

183

Downward pattern of weight gain in stroke survivors.

How Is It Done?

So what exactly is the correct diet for someone rehabbing from stroke? Lots of useful information in libraries, on the web, and from health professionals will provide all the specific diet suggestions you’ll ever need. Here are a few basic dietary guidelines for anyone trying to improve physical performance:

• Try to remain within your optimum weight. It’s a lot easier to lift your arm if it weighs 20 pounds than if it weighs 30 pounds. Your doctor can tell you your optimum weight. Weight beyond your optimum makes training after stroke difficult because extra weight is weight that has to be lifted, shifted, and held whenever you move. Also, unnecessary fat needs to be vascularized (blood vessels need to be manufactured by your body to feed the extra cells). This extra vascularization makes the heart have to work that much harder to pump that much more blood to these new vessels.

• Choose quality carbohydrates. Carbohydrates can be bad (processed) or good (unprocessed).

— Processed (also known as refined or simple) carbohydrates like white rice, potato chips, pretzels, white bread, white sugar, candy, sodas, and so on, are digested and absorbed into the blood rapidly, which causes a rapid spike in blood sugar. The quick release of sugars puts stress on the system to quickly reduce blood sugar. The organ responsible for controlling blood sugar is the pancreas. The chemical it uses to decrease blood sugar levels is insulin. The pancreas and insulin do their job well. They do it so well that high blood sugar becomes low blood sugar after eating simple carbs. Folks eat again, often craving simple carbs, in an attempt to offset the loss of energy (caused by low blood sugar). Enough of these roller coaster rides of sugar levels and the pancreas becomes overwhelmed and cannot produce enough insulin. If that happens, diabetes can develop.

— Unprocessed (also known as unrefined or complex) carbohydrates like whole grain bread, brown rice, and whole fruits (apples, oranges, etc.) provide a much more gradual digestion of the carbohydrate, resulting in a much more gradual release of sugar. The slower the release of sugar, the better, because a gradual release can be better absorbed, stored, and used by the body.

• Stay away from bad fats. Bad fats include hydrogenated and partially hydrogenated fats. Hydrogenated fats are oils that are heated, and once they cool, stay solid at room temperature. Partially hydrogenated fats are oils that are heated, and are somewhere between solid and liquid at room temperature. Hydrogenated and partially hydrogenated oils are found in fried foods and are ingredients in pastries, chips, cookies, crackers, muffins, donuts, candy, and much of fast food. These bad fats are written in the ingredients list on a food package as hydrogenated vegetable oil, partially hydrogenated vegetable oil, or shortening.

• Use good fats. The flipside to the oil equation is increasing good fats in your diet. Good fats include extra virgin olive oil, cod liver oil, nut oil, flaxseed oil, and canola oil. Another important fat is fish oil. Fish oil has a near perfect ratio of the three important fatty acids: eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). Fish oil may help stroke survivors in two ways:

1. DHA and EPA may help to reduce swelling in the brain after stroke.

2. Fish oil helps overall function of the nervous system and is considered “neuroprotective” (a substance that protects the nervous system).

• Good fats will actually lower the level of bad fats. These good fats can have health-boosting qualities. High levels of good fats before a stroke decrease memory loss and disability after a stroke.

• Eat a lot of fresh fruits and vegetables. Fruits and vegetables have important vitamins, minerals, and amino acids (the building blocks of proteins). Fruits and veggies should be eaten in a state that is as unprocessed as possible. Processed means cooked and/or combined with other ingredients. For instance, simply slicing a fruit or vegetable will reduce the amount of vitamins and minerals it has because some of the nutrient-rich juice is lost. Fruits and vegetables that are unprocessed and fresh will provide the greatest nutritional value. Fruits and vegetables help satiate your hunger, which keeps you from eating less healthy foods.

One habit that is essential to a healthy diet is simply reading the ingredients of what it is you eat. Reading the ingredients will lead to simple but profound questions like:

• “What is that ingredient?”

• “Why is that chemical in this food?”

• “How does this food compare to its whole (unprocessed) version?”

These questions inevitably lead to better dietary choices because they provide information about what you are eating, and help you to question why you eat what you do.

Buildup in the walls of arteries, the blood vessels that carry blood from the heart to all the cells in the body, is the cause of many strokes. This buildup is called plaque. High levels of a chemical called homocysteine can cause plaque buildup. People who have had a stroke have a tendency toward high blood levels of homocysteine. This may be a problem that is easily solved. Ask your doctor about the use of vitamin B12 to reduce levels of homocysteine. It is worth noting that high levels of homocysteine also increase your chance of disability after stroke.

Stroke can affect your ability to taste. Stroke can make foods taste weird, bad, or it can reduce your ability to taste at all. There is even a word for this change in the ability to taste after brain injury: dysgeusia. There may be a tendency to overcome the lack of taste by adding taste enhancers like salt, extra sauces and spices, or by frying foods. Be prudent and healthy with your choices as you attempt to make food palatable.