593 Safeguarding the Recovery Investment

REDUCE PAIN TO INCREASE RECOVERY

_______________

Long-term pain after stroke is common. Up to 70 percent of stroke survivors experience some sort of pain every day. Pain after stroke can reduce recovery. Survivors with pain have more mental decline, more fatigue, more depression, a lower quality of life, and a general decline in function. There are a variety of treatments for pain after stroke, including medications, things that therapists can do, and things survivors and caregivers can do.

How Is It Done?

The biggest problem with pain after stroke is: The pain often goes unreported to clinicians. There is a variety of reasons for this lack of reporting of pain, including:

• Unilateral neglect

• Aphasia

• An inability to express the pain. For instance, clinicians often use some sort of pain rating scale. You may have seen these as a series of drawings of faces showing various levels of pain. Or perhaps the scale is a 1 to 10 scale. Survivors sometimes have difficulty completing these rating scales.

Stroke survivors should tell physicians and therapists about any and all pain they are experiencing. Caregivers can be helpful in relaying the pain the survivor is experiencing to doctors, nurses, and therapists.

60Clinicians sometimes make the mistake of thinking that the pain is related to the stroke because of the musculoskeletal (muscles, bones, and joints) changes caused by the stroke. Of course, musculoskeletal pain after stroke is common. But pain after stroke may be caused by something else. So explain it to clinicians in detail so they can make an assessment as to the cause, and treatment, of pain.

The following types of pain are common after stroke:

Shoulder Pain

Here are some interesting “quick hits” about shoulder pain after stroke . . .

• Up to one half of survivors have shoulder pain

• After stroke, shoulder pain shows up within three weeks

• Survivors have a higher chance of having shoulder pain if they also have hemiparesis (arm weakness), sensory problems (proprioception, tactile, temperature sense), and spasticity.

• Shoulder pain is more prevalent in survivors who have left-sided weakness than right- sided weakness.

Shoulder pain after stroke can be caused by a number of factors. Included are . . .

• Subluxation (dislocation). Find information in the section entitled Shoulder Care 101 later in this chapter

• Impingement (structures in the joint are squeezing or rubbing other structures and cause pain)

• Tears in the muscles and tendons that keep the top of your upper arm bone in the shoulder socket (the rotator cuff)

• Bicipital tendinitis (swelling of the tendon of the biceps muscle near where it meets the shoulder)

• Regional pain syndrome, discussed later in this section.

• Spasticity

61Treatments for shoulder pain include . . .

• Percutaneous (through the skin) electrical stimulation: An example of this is Bioness’s StimRouter. A fine wire—about the diameter of a hair—is surgically implanted either as an outpatient procedure or in a hospital surgical center (it’s minimally invasive and performed under local anesthesia). The survivor uses a hand-held unit to control the amount and type of stimulation to treat their pain.

• Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS): Low-level electrical stimulation done through the skin with electrodes. No muscles contract with TENS.

• Neuromuscular electrical nerve stimulation (NMES): Higher level electrical stimulation where muscles move and joint movement may take place. (See the section Shocking Subluxation in Chapter 4 for information on using TENS and NMES to reduce shoulder pain.)

• Shoulder slings, lap boards, arm troughs, shoulder strapping and shoulder taping: These may help with pain by supporting the shoulder.

• If spasticity is the cause of shoulder pain, the treatments discussed in Chapter 7: Spasticity Control and Elimination will be helpful.

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a highly painful condition affecting the limbs. In stroke, CRPS can be caused by the weakness of muscles that no longer support joints the way they should. Typically, this is seen in the shoulder joint due to the subluxation (dislocation) of the shoulder after stroke. Often, this syndrome in stroke is referred to as shoulder-hand syndrome (SHS). Although the mechanism (pathophysiology) of CRPS remains poorly understood, the symptoms are clear:

• An arm that is highly sensitive and painful to move and/or touch: Survivors with CRPS that affect the arm often complain that even their clothing hurts where it touches their skin.

• Pain in the leg and foot: CRPS can also affect the leg and foot. The symptoms and treatments for CPRS in the leg are the same as for the arm.

• Signs of CRPS in the arm include any or all of the following:

— Highly painful

— Swelling

— Limb is warm to the touch

— Changes in skin color

— Changes in hair growth

— Muscle weakness

— Reduced active and passive range of motion

A good way to test if CRPS/SHS is to observe the “good” and “bad” arm side-by-side and note the differences. If any if the above symptoms are evident, bring it to your doctor’s attention.

Treatment options for CPRS/SHS include:

• Mirror therapy (see this section in Chapter 4).

• TENS: Low-level electrical stimulation to the affected area. TENS can be used to desensitize the painful area.

• Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS): This is an emerging treatment for CRPS/SHS. This nonpainful treatment sends pulses of electromagnetism through the skull to the portion of the brain that represents the painful area.

• Imagery/mental practice: See the section Imagine It! in Chapter 4.

• Immobilization: Before anything else is tried, not allowing the limb to move, either voluntarily or with a splint, may help ease the pain.

• Mobilization: Joint mobilization is a gentle passive movement performed to the survivor, with the survivor always able to stop the movement.

• Elevation: Elevating the limb may reduce the swelling and pain.

• Massage: Massage may reduce swelling and decrease pain.

• Gentle range of motion.

• Alternating hot and cold baths.

• Surgery: Discuss this with your doctor.

63What Precautions Should Be Taken?

Survivors express pain—40 percent of survivors who initially deny pain express pain once a physical exam is done. Survivors should report pain and clinicians should test for pain. So, the first plan of action for the survivor in pain is not medication or some sort of treatment. It is to be proactive in reporting the pain to clinicians. Pain should be reported and tested for no other reason than this: Pain halts recovery.

STAY OFF THE KILLING FLOOR

_______________

Falls are a serious health threat to everyone, but falls are especially dangerous to stroke survivors. Here are some scary statistics:

• Up to 70 percent of survivors have a fall in the first six months after their stroke.

• A stroke survivor is up to four times more likely to break a hip than people of the same age who have not had a stroke.

• Stroke survivors are two times as likely to fall, and three times as likely to be injured in a fall, than those who have not had a stroke.

• If anyone over 65 has a fall that results in a hospital stay, they have a 50 percent chance of dying in the next year.

Stroke survivors tend to fall because:

• They have weakness on the affected side of the body. Weakness can cause loss of balance. Stroke survivors tend to lose balance toward the affected side, which can increase the chances of a fall toward the “bad” side.

• They have loss of sensation on the affected side. Loss of sensation in stroke survivors takes any or all of the following forms:

— Loss of feeling on the skin, like light touch and temperature

— Numbness in the affected limbs

— Loss of proprioception, which makes it impossible for the stroke survivor to know what position his leg is in. That is, if a stroke survivor’s eyes are closed, he cannot “feel” where the leg is.

64Weakness and poor balance control often cause the stroke survivor’s weight to be thrown toward that “bad” side during a loss of balance. Once balance is lost, the stroke survivor tends to fall toward the weak side and is unable to brace for the fall with the paretic (weak) arm and hand. During the fall, there is a tendency to land on a particularly vulnerable part of the hip, the part that sticks out on the side of the leg, called the greater trochanter. Falling on this part of the leg can lead to a fracture (break) of the upper leg bone or any bony part of the hip joint. Repairing a broken hip is major surgery. To repair a broken hip, either the femur (the bone that forms the top of the leg and forms part of the hip joint) is fastened together with screws and plates, or the entire hip joint is replaced.

These sorts of surgeries are not without complications. You can develop:

• Pressure sores or blisters

• Lung infections

• Urinary infections

• Surgical complications (e.g., tissue infections)

• Orthopedic complications

• Gait deviations (limp)

• Thromboses or embolisms, which are types of blood clots that can cause another stroke

To top it all off, if you break a hip, you have a greater chance of having another hip fracture.

Hip fracture is only one of the devastating injuries that can be caused by a fall after stroke. Other broken bones in other parts of the body and/or other types of injuries can occur. In many ways falls can be devastating for stroke survivors. Falls can:

• Halt progress toward physical recovery

• Kill (either from the fall itself or from complications arising from the fall)

• Break any number of a wide variety of bones

• Forever end the ability to walk

• Increase the fear of walking

• Reduce the amount and quality of walking

• Lead to wheelchair confinement

• Forever make walking painful

• Lead to a hip replacement or surgery that reattaches the bone

Convalescence from a fall can lead to:

• Clot formation

• Bed sores

• Loss of strength in both muscles and bones, even those not injured in the fall

• Reduced cardiovascular stamina

Physical injury is not the only damaging result of a fall. Once someone has had an incident, the fear of falling again often causes people to restrict cherished activities like shopping, eating out, and attending church. Because of reduced involvement in the community, falls can result in social isolation and depression. Falls also make stroke survivors fearful to work on recovery, especially recovery efforts that involve standing, stair climbing, or walking.

How Is It Done?

Here are some suggestions for reducing falls:

• Exercise regularly. Strong muscles help reduce falls.

• Wear sturdy shoes outside and inside. Do not walk in slippers, flip flops, socks, or barefoot.

• Overall, allow for more lighting in your home.

• Clear away all items that you can trip over. Make sure pets are kept out of the walking area.

• Do not use throw rugs that can slide or move.

• Place often-used items within easy reach to eliminate the need for a step stool.

• Make sure there are handrails on stairs.

• Have your doctor review your medications regarding their potential influence on falling. There is a direct relationship between the number of medications taken (no matter what kind) and the risk of falling.

• There are tests that can be done in the clinic to predict if you are at risk for falls. These tests include:

— Five-Times-Sit-to-Stand Test

— Timed Up and Go

— Functional Reach Test

— Berg Balance Scale

— Falls Efficacy Scale

These tests are usually done by physical or occupational therapists.As well:

• Have your vision checked yearly.

• Have a physical or occupational therapist visit your home to make sure your home is as fall proof as possible.

• Consider protective padding. There are discreet hip pads that can be worn inside undergarments to protect hips during a fall. There are many manufacturers producing hip pads of this sort.

• The bathroom is a uniquely hazardous room. Many hard surfaces within a small area combined with wet and slippery floors make bathrooms potentially dangerous. The need to transfer from bath/shower and toilet make bathrooms a challenge to fall proof.

Here are suggestions for keeping your bathroom safe:

• Install grab-bars in the tub and shower.

• Install grab-bars next to the toilet.

• Place nonslip mats in the bathtub and shower.

• Make tiles nonslip with chemical treatments that etch the surface.

• Have adequate lighting on the path to and in the bathroom so that it’s easy to see during night-time trips.

• Don’t lock the bathroom door in case you need help.

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

The main precaution is do not ignore this chapter. This may be the most important chapter in this book. Falls kill. When told of these facts, many people 67think that clinicians are just trying to scare them. In this case, it is a healthy fear. Take precautions.

REDUCE THE RISK OF ANOTHER STROKE

_______________

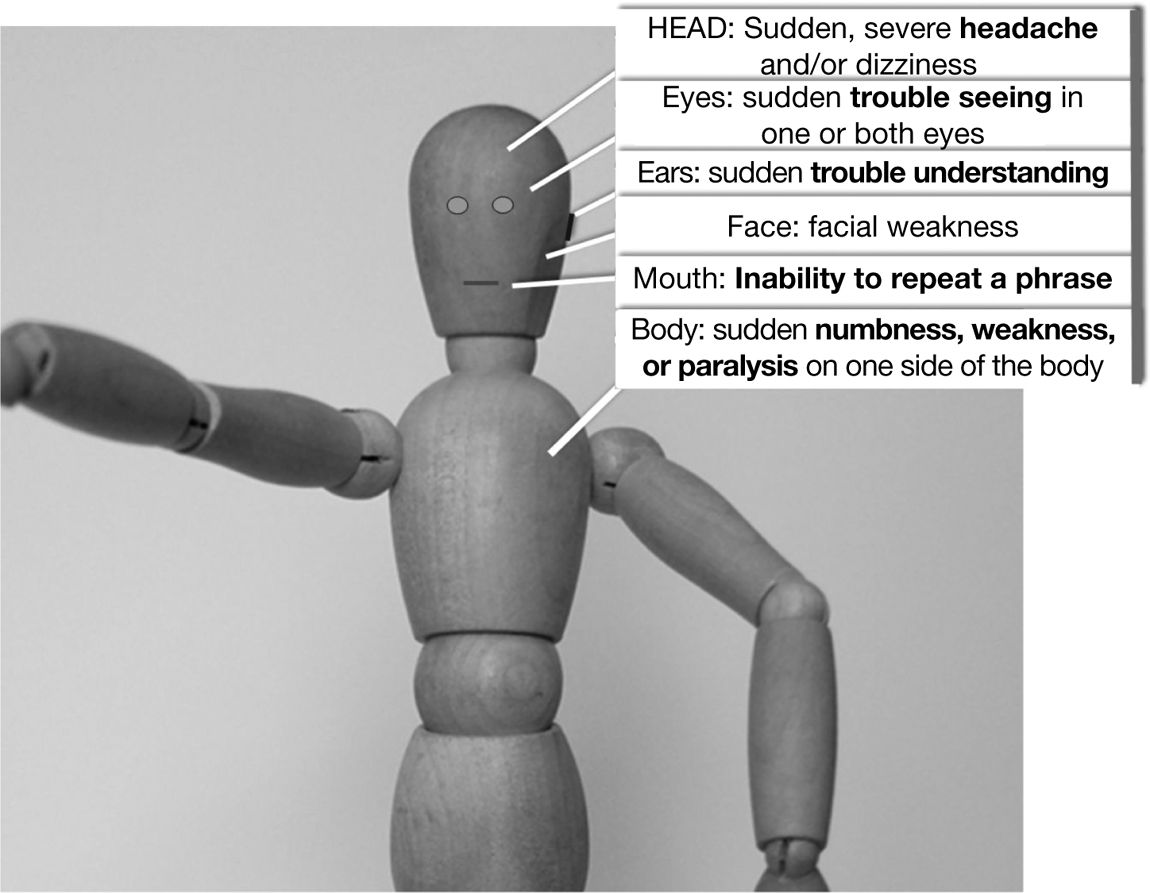

Many stroke survivors and their caregivers do not know the complete list of possible stroke symptoms. If you’ve already had a stroke, you have a pretty good chance of having another one. 26 percent of survivors will have another stroke within 5 years of their first stroke. Almost 40 percent of survivors will have another stroke within 10 years of their first stroke. It is essential that you know all the symptoms of stroke, not just the symptoms that were experienced during your previous stroke.

How Is It Done?

Learn the symptoms of stroke. The easiest way is to start at the top of the head and move downward.

• Skull: Sudden, severe headache and/or dizziness, with no known cause

• Eyes: Sudden trouble seeing in one or both eyes

• Ears: Sudden trouble understanding

• Mouth: Inability to repeat a phrase

• Face: Facial weakness

• Body: Sudden numbness, weakness, or paralysis on one side of the body

There is a quick, easy, and effective way of determining if someone is having a stroke. Developed by researchers at the University of Cincinnati, the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale helps people recognize a stroke by asking the individual to do three things:

1. Ask the individual to smile.

• Are both sides of the face equal? Is one side of the face drooping?

2. Ask the person to speak a simple sentence clearly, such as: “The sky is blue in Cincinnati.”

• Listen carefully to the quality of speech. Are words being slurred?

3. Ask him or her to raise both arms.

• Does one arm drift? Are both arms held at the same height?

If the individual has difficulty with any of these tasks, call 9-1-1 immediately, and describe the symptoms to the dispatcher.

React quickly! Some of the newer medications for reducing the impact of a stroke have to be administered within the first 2 or 3 hours after stroke, so recognizing stroke quickly is essential to surviving and recovering from a stroke. A stroke is the process of brain cells dying. Every minute of a stroke destroys almost two million nerve cells in the brain. Time saved is brain saved.

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

Know the symptoms of stroke. Remember: From the top down—skull, eyes, ears, face, mouth, and body.

69PROTECT YOUR BONES

_______________

Stroke survivors are at a much higher risk for breaking bones than the general population. Stroke survivors have up to four times the risk for breaking bones. There are two main reasons for this:

• People who have had a stroke have a tendency toward high blood levels of an amino acid, homocysteine. Homocysteine can weaken bones.

• The lack of weight-bearing activities such as walking and other load-bearing activities puts less pressure on bones. The decrease in pressure may reduce the thickness of bones, leading to osteoporosis (a process known as Wolf’s law).

It is essential that you have a plan for maintaining bone health and bone strength. This plan might include any or all of the following:

• Diagnostic tests (bone density tests can be done by your doctor to determine if bones are at risk for fracture)

• Assessment of risk for falls

• Addition of bone-building medications or supplements

• Performance of any of a variety of forms of physical activity, including resistive exercises and a daily routine of walking

How Is It Done?

There are many techniques to increase bone strength and reduce the risk of damage to bones, such as the following:

• As discussed in the section Weight Up! in Chapter 6, resistance training (and or weight training) will build bone thickness (Wolf’s law).

• Fall prevention steps will decrease fractures (see the section Stay Off the Killing Floor earlier in this chapter).

• Walking, as part of a daily routine, can reduce bone loss after stroke.

• A variety of medications can decrease or prevent bone loss and have the possibility of increasing bone strength. Ask your doctor about these medications.

• Nutritional steps can be taken to help bone health. These include supplementation with calcium, folic acid, and vitamin B12, plus adequate protein intake. All of these can potentially build bone strength. There is some scientific evidence that vitamins K and D reduce osteoporosis in stroke survivors. Sunlight may help build bones as well.

• There are many techniques that physical therapists can provide, which can improve balance and reduce falls. Have a physical therapist develop a balance training exercise program that you can do safely at home. This should be part of your comprehensive home exercise program (see the section Get a Home Exercise Program in Chapter 5).

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

All of the steps you take to reduce fractures should be discussed with your doctor. Supplementation with vitamins, minerals, amino acids, and so forth may interfere with medications, so talk to your doctor before taking vitamin, minerals, amino acids, or herbal supplements.

DON’T SHORTEN

_______________

Some stroke survivors have difficulty straightening their affected elbow because of muscle tightness (spasticity). The elbow is constantly bent, and it continues to stay bent, most hours of the day, every day. After a while, the structures around the elbow joint, including skin, nerves, blood vessels, and other soft tissue, shorten. Most importantly, muscles shorten. Once shortened, the tissue will remain shortened forever. Straightening the elbow becomes impossible. The elbow can’t even be straightened with the help of the unaffected hand, or with the help of someone else. This inability to straighten a joint is called contracture. Contracture eliminates any possibility of the joint recovering its original arc of movement. Once there is contracture, surgery to lengthen the shortened soft tissue is necessary. Another treatment that is sometimes successful is called serial casting (explained later in this section). Contracture is a serious condition with serious consequences: If the best possible treatment for you becomes available, contracture will eliminate any possible benefit.

As stroke survivors progress beyond being flaccid (limp), muscles tend to become spastic (tight). This tightness can lead to contracture. Safely and effectively stretching the muscles on the “bad” side should be done constantly 71and faithfully so contracture does not develop. Constant stretching of muscles will help retain the full length of those muscles (and other soft tissue). This will allow you to retain the greatest possible range of motion. Stretching may conserve soft tissue length and protect joint range of motion, both of which are essential to any further recovery. Soft tissue length that is maintained will provide the perfect template for recovery techniques as they become available. Other reasons that stretching is so important:

1. Stretching may provide a short-term reduction in spasticity. It is common for therapists and other clinicians to believe that stretching reduces spasticity. But because spasticity is a brain problem and not a muscle problem, copious stretching will not reduce spasticity permanently. However, there is some research showing that stretching provides some short-term reduction in spasticity.

2. Stretching reduces the soreness sometimes associated with recovery efforts. Much of the recovery from stroke involves repetitive practice, which can work muscles in ways they are not used to. This can lead to something called delayed-onset muscle soreness, or DOMS. This phenomenon usually develops one to several days after the actual practice. Stretching can reduce or eliminate DOMS.

3. Stretching is good for you. Stretching is of benefit to muscle and other soft tissue, whether affected by the stroke or not. Retaining flexibility keeps your body young. Stretching will benefit muscles on the unaffected side, the trunk, and in other areas of the body. Bringing a joint through its entire range of motion (which stretching does) also helps to keep the joint itself healthy.

4. Stretching keeps joints and muscles healthy. One of the problems after stroke is that the limbs are not moved through their normal range of motion (ROM). ROM refers to the complete arc of available, nonpainful movement of a joint. For example, at the elbow, the ROM would be from the elbow fully bent to the elbow fully straight. In folks who have not had a stroke muscles and joints are taken through their full ROM many times a day. Stroke often impedes joints on the “bad” side going to their natural ROM. Muscles and joints are designed to move. Stroke tends to keep muscles and joints static. The more joints and muscles are moved after stroke, the healthier they remain.

5. Stretching makes every movement easier. Muscle uses spasticity to protect itself from being torn. Spasticity limits the amount of movement a muscle can do. The tightness of spasticity stabilizes the extremity. The good news is that muscle is much less likely to get torn since it is stabilized. The bad news is, the limb is hard to move. Both the flexors (muscles that “close” a joint) and extensors (muscles that “open” a joint) may have spasticity after stroke. But the muscles that flex joints tend to be bigger and more powerful than the muscles that extend joints. The upshot of all these muscles firing is what’s known as a “hemiparetic posture.”

The typical hemiparetic posture in the upper extremity is with the arm across the front of the body with the elbow, wrist, and fingers bent. This posture is simply the flexor muscles “beating” the extensor muscles every time. There is relatively more spastic pull on the muscles that bend joints than straighten joints. This posture is a defense mechanism for the arm and hand. Consider the alternative. If the arm were limp, it would flail by your side in constant danger of tearing muscle, damaging joints, and bumping into nearby objects. Basic protection comes from some of the spastic muscles pulling the arm and hand near the body.

The same is true in the leg and foot. The calf muscles are big and bulky and are actually comprised of two powerful muscles that lift the entire weight of the body while walking. These muscles point the foot downward at the ankle. 73The muscle lifting the foot (tibialis anterior) is tiny by comparison. Its only job is to lift the foot at the ankle. This small muscle is in a “spastic war” with the huge calf muscles. If both muscles are in a spastic battle, guess which muscles wins? The “winning” muscles lose by remaining in a shortened position. Over time, the muscles left in a shortened position shorten permanently.This is one of the reasons lifting the foot after stroke is so hard, and why ankle-foot orthoses (AFO) are often prescribed.

Note that in both the arm and the leg, there is a “neuroplastic model of spasticity reduction.” This radical option that does not require any medications is outlined in the section Neuroplastic Beats Spastic in Chapter 7.

How Is It Done?

To reduce the risk of contractures, perform stretching on yourself, or have a trained caregiver perform these exercises. The joint should be brought through its complete nonpainful range of motion several times a day. Generally, stretching is something that stroke survivors can do for themselves.

The best advice available for stretching comes from a plan set up by your occupational and physical therapists. Typically, an occupational therapist would develop a stretching program for the arm and hand, and a physical therapist would do the same for the leg and foot. Ask your therapists for specific stretches that, while remaining safe, are as aggressive as possible and can be done at home. See the precaution section prior to attempting any stretching. Focus stretching on the following muscle groups (it is never a single muscle, but a group that works together, that needs stretching).

Muscles that most need stretching in the arm and hand include:

• The finger flexors (the muscles that make a fist)

• The wrist flexors (the muscles that bend the wrist in toward the arm)

• The elbow flexors (the muscles that bend the elbow)

• The shoulder adductors (the muscles that bring the upper arm close to the body)

• The shoulder internal rotators (the muscles that bring the forearm across the front of the trunk)

74Muscles that most need stretching in the leg and foot include:

• The hip adductors (the muscles that bring one leg toward the other at the hip)

• The hip flexors (the muscles that bend the hip toward the chest)

• The knee flexors (the muscles that bend the knee)

• The ankle plantar flexors (the muscles that push the foot down; when standing, this would be a “heel-up” position)

• Toe flexors (the muscles that bend the toes down)

Remember, these are the muscles that need to be stretched, so the stretch would go in the direction opposite of the movement described previously. For example, if you want to stretch the elbow flexors that bend the elbow, then you would stretch by moving the elbow in the opposite direction—that is, straightening the elbow.

A note about stretching the wrist and fingers: If the fingers are stretched without also extending the wrist, some of the muscles will not get stretched. This is because the same muscles that cross the wrist also cross all the joints in the fingers. Effective stretching involves extending the wrist at the same time as the fingers are stretched (prayer position). Conversely, if the wrist is being stretched, then the fingers should be extended.

This is just one of many examples of how stretching may have a bit more complexity than you might imagine. Therapists are experts at taking the guesswork out of stretching. If a high-quality stretching program is developed, it will be effective for the rest of your life. Therapists will be able to develop a stretching program for you in one to three sessions.

Stroke survivors often ask, “How often should I stretch?” Ideally, you would stretch the “bad” side muscles as much as the “good” muscles are naturally stretched. Consider the muscles that bend the elbow. How many times a day is your “good” elbow straightened? This gives us a window on what muscles require to stay healthy. Providing the same amount of stretching as the “good” side may not be feasible due to time constraints. Still, we can assume that an effective self-stretching program needs to be done more often than it usually is.

Another effective treatment to encourage the lengthening of muscles on their way to contracture is a long, slow stretch over an extended period of time. The only treatment that holds a stretch long enough in order for muscle to lengthen is called “serial casting.” Serial casting . . .

• Involves having the joint casted in a lengthened position, which helps the muscle permanently lengthen.

• Stretches soft tissue by using a series of casts over time. Each of the casts stretches the soft tissue a little more.

• Is usually done by specially trained physical or occupational therapists. Serial casting is done in cases where spasticity is very high and regular stretching programs are ineffective.

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

Sometimes spasticity is so strong that muscle turns into a rope-like connective tissue that no longer acts like muscle. This new tissue keeps the joint in a constantly flexed position. This is called contracture. If you are unable to take any joint through its range of motion, even with the help of your unaffected side or with the help of a caregiver, consult either a physiatrist or neurologist. There is a window of opportunity when the muscle is spastic (but is still muscle) and when the muscle changes into something else and becomes a contracture. There are a variety of treatments that might decrease the spasticity that is leading you toward contracture. There are two ways to administer medications for spasticity: orally and injected straight into the muscle. Oral spasticity medications often leave patients tired because they are muscle relaxants that affect all the muscles of the body, not just the spastic ones. New developments in the delivery of spasticity medication now allow doctors to target only the muscle groups that are spastic (see the section Give Spasticity the One–Two Punch in Chapter 7). Once contracture has set in, there is still hope—serial casting, discussed earlier in this section.

When stretching muscles, carefully follow the instructions of the healthcare professional who has taught the stretches. Pain always means, “Stop the stretch!” Even something as simple as passive range of motion (having the joint moved without the power of the muscles surrounding the joint), whether done by yourself or by someone else, can be dangerous. Muscles, ligaments, and joints can be torn and veins, arteries, and nerves can be damaged.

There are recent research reviews that question the effectiveness of stretching for the reduction of spasticity. These reviews further question the effects of stretching on muscle length, joint mobility, pain, quality of life, and the treatment and prevention of contractures. But there are still good reasons to stretch. For example, the number one cause of post-stroke shoulder 76pain is not subluxation (shoulder separation due to weakness of the shoulder muscles). The number one cause of post-stroke shoulder pain are adhesions that build up in the shoulder joint (see the next section Shoulder Care 101 for a full explanation of shoulder adhesions). What keeps these adhesions at bay? Stretching. Or at least “ranging.” Ranging is a term that therapists use to mean taking the joint through its full range of motion. Ranging is done passively, as is stretching. That is, a stroke survivors limb is moved through its available painless range of motion, but some outside force does it. It might be a clinician, a caregiver, or the survivor themselves ranging the joint. Also, stretching provides an immediate—if short-term—reduction in spasticity. This short-term reduction may help your recovery. Stretching feels good, too. The bottom line is, once your therapists and your doctor develop a safe stretching program, the biggest precaution is not stretching enough!

SHOULDER CARE 101

_______________

Many stroke survivors have shoulder pain. Even when someone has not had a stroke, the human shoulder joint is vulnerable. This is because the shoulder joint is designed for movement, not strength. After stroke, the muscles that normally keep the shoulder stable are often too weak to hold the joint in place. This can lead to subluxation (dislocation) of the shoulder. Subluxation can lead to painful and limited movement, as well as joint damage.

Because of the weakness of the muscles that surround the shoulder joint, the shoulder should be cared for. This care should begin as soon as the survivor is medically stable and should include passive range of motion (PROM) where the arm is gently and safely moved for the survivor. Also helpful to protect the subluxed shoulder is positioning and supporting the arm both at rest and during any attempted movement. Caregivers and clinicians should take care not to use the affected arm during transfers (e.g., sitting to standing). It is not uncommon for a well-meaning helper to do damage to the vulnerable subluxed shoulder because they use the affected side arm for leverage during transfers.

Even if no dislocation has occurred, the shoulder can be a problem after stroke. Many shoulder problems after stroke are caused by the reduction in overall shoulder movement. In healthy individuals the shoulder is moved in many different ways throughout the day. After stroke the shoulder is often postured in one way for much of the day. The typical way the arm is held after 77stroke is across, and close to, the chest. The shoulder joint is usually held like this because of:

• Limited strength of the muscles that move the arm away from the body

• Spasticity that makes the joint difficult to move

• Stiffness and pain that limit movement

Often after stroke the shoulder joint is no longer being moved through its normal range of motion.

• Limited movement in the shoulder joint allows adhesions to build up. All your joints need to be moved to stay healthy. After stroke, limited movement allows for a build-up of tissue (called adhesions) in the joint. In fact, the main cause of shoulder pain after stroke is adhesions that build up in the joint due to lack of normal movement. Moving the joint through its entire arc of potential movement is important to reduce adhesions. This sort of movement is called “passive ranging.” Passive ranging involves the survivor moving the “bad” arm with the “good” arm, or by having someone else move the bad arm for them.

• Limited movement in the shoulder joint causes tightness in the shoulder joint. Soft tissue (muscle, nerves, blood vessels, etc.) around the joint shortens over time, which makes movement even more difficult. Because movement is difficult, the shoulder is moved less. Because the shoulder is moved less, the soft tissue becomes even shorter and muscle strength declines.

These factors can make movement uncomfortable, painful, and difficult. In some cases, the soft tissue shortens and adhesions build up so much that movement at the shoulder is impossible. When shoulder movement is limited because of adhesions the shoulder is said to have a contracture. Other terms that are used for this limited shoulder movement are “adhesive capsulitis” and “frozen shoulder.” The loss of normal shoulder movement and other negative aspects brought to bear on the shoulder by stroke (e.g., reduced blood flow, muscle atrophy) can magnify shoulder pain after stroke. Also, the shoulder joint can be at risk because people will attempt to help you move by grabbing the “bad” arm, which can injure the shoulder joint.

Probably the worst stressor on the shoulder joint is delivered with pulleys. Pulleys are handles attached to ropes. The ropes are attached to a wheel so that 78if you pull downward on one handle, the other handle (with the other arm and hand holding it) goes upward. Pulleys are available in most rehabilitation gyms. Therapists often use them to help patients with different disorders (not just stroke) “range” themselves (self-stretch). Pulleys can be dangerous for the weak-side shoulder of stroke survivors. Unless a doctor specifically suggests pulleys, decline their use. Other forms of aggressive “ranging” (putting the joint through, and beyond, its range of motion) with the aid of your “good” side, or with the aid of another person or machine, should be considered cautiously. Aggressive ranging of the shoulder joint can damage the joint. Keep in mind, however, that proper, nonpainful stretching of the shoulder joint is necessary after stroke. The shoulder should be part of a comprehensive stretching program. Your stretching program should take all the joints on the affected side through their full, safe, and nonpainful passive range of motion.

How Is It Done?

It is important to focus attention on the affected shoulder to prevent injury, increase coordination, and keep muscles strong. This attention will allow for the largest possible potential recovery of shoulder movement. Here are strategies that can help to protect the shoulder:

• Kenisiotaping (also known as physiotaping or simply taping or strapping): This may protect the shoulder and allow for correct movement. Note that there is very little research indicating that shoulder taping after stroke helps shoulder movement or shoulder function. However, while it’s worn, tape may help reduce pain. Many therapists view taping as a promising treatment option for shoulder pain after stroke.

• Positioning techniques: Positioning the shoulder when the arm is at rest in order to protect the joint.

• Shoulder slings: There is limited evidence that shoulder slings can help shoulder function and protect the shoulder.

• Strengthening surrounding muscles: The best way to protect the shoulder joint is to strengthen the muscles around it and adequately and gently stretch the joint. Occupational and physical therapists are experts in exercises that aid the shoulder joint. Exercises that build muscle to support the shoulder are essential. Rehabilitation specialists can provide exercises appropriate for stroke survivors. Consult your doctor and rehabilitation healthcare worker and ask them to provide an exercise plan that will help shoulder recovery.

• Many researchers believe that the best thing you can do for your shoulder is increase movement in the hand. The shoulder is, after all, there to get the hand where it needs to go. The shoulder will develop strength and coordination naturally if it is moving the hand in real-world ways. The work of getting the hand functional can have a significant effect on the muscles that control the shoulder. Some therapists and researchers believe that a useable hand will actually resolve subluxation (dislocation) of the shoulder. As the hand is used more, the shoulder muscles are used more. As the shoulder muscles are used, they strengthen, which pulls the shoulder joint together. Ideas to get the hand “back in the game” are discussed in the section in Chapter 4 titled Get Your Hand Back.

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

Consult your doctor regarding any pain that affects function of the shoulder. Don’t make the mistake of not consulting a doctor for pain that limits movement. Reduced movement can lead to a downward spiral, causing shortening of the soft tissue that surrounds the joint, which leads to less movement and, in turn, can lead to more shortening of soft tissue. Limited movement can also increase the incidence of adhesions in the shoulder joint. Periodically consult your occupational or physical therapist for proper exercises and other treatments and modalities to help support the weak-side shoulder.

FIVE TESTS YOU SHOULD DO

_______________

You will often hear about how important cardiovascular health is. For stroke survivors, the impact of damaged and clogged arteries has already been felt. You might think that having a stroke is an isolated incident. But the truth is that stroke survivors have their stroke to thank for alerting them that all is not well with their blood vessels. Vascular disease is not isolated; it is a disease that usually shows up in the walls of many arteries at once. Arteries are the blood vessels (plumbing, if you will) that take blood from your heart and delivers it to every one of the trillions of cells in your body. There are an estimated 30 thousand miles of arterial blood vessels in the human body. Arterial disease can happen in any number of vessels. The fact that some arteries are diseased may not make much difference in your life. But in some organs, like the heart and brain, this disease process can kill you. Stroke survivors know what can 80happen in the brain when an artery clogs or bursts: stroke. Most people know the impact of this disease in the heart, too: a heart attack. Arterial disease is 80 percent preventable. Here are a few basic steps that you can take to keep your arteries healthy:

• Stop smoking

• Control your diet/weight, blood pressure, and cholesterol

• Control diabetes

• Exercise

All of these will benefit the health of your arteries. Once you put these efforts into practice, follow up by doing some simple tests. These tests will help you determine if your efforts are successful.

One other thing you can do to help keep your arteries healthy: control stress. Stress can cause a stroke. Actress Debbie Reynolds recently died just one day after the death of her daughter, actress Carrie Fisher. The press says she died of a “broken heart” and that is probably true. There is now science that shows that stress can cause stroke and other cardiovascular diseases. But the connection between stroke and stress is indirect. Here’s the story: The amygdalae (plural; there are two of them. Singular is amygdala) are small, marble-sized structures in the brain responsible for emotions. In folks who have cardiovascular disease (like stroke) there is more activity in the amygdalae. This increased activity causes more C-reactive protein, a ring-shaped protein found in blood. C-reactive protein clots blood. Blood clot in the brain = stroke. Bottom line: Stress = Increased blood clotting = Stroke.

How Is It Done?

A series of tests that can reveal arterial health follows. Two of them, pulse and blood pressure (BP), should be done during the entire recovery process. They should also be done during each recovery workout or session. Pulse and BP will provide essential information that will keep you safe as you continue to recover. Pulse and BP can also provide information about overall, long-term cardiovascular health and strength. Generally, the lower the numbers for both pulse and BP, the better. Your doctor can provide specific guidelines. Pulse and blood pressure should also be taken during periods of activity and rest. Resting pulse and resting BP are key indicators of cardiovascular health (again, generally, the lower the better). Keep an ongoing record of these two measures. Your self-testing results will provide valuable information for your 81doctor and therapists, so bring the results with you when visiting health professionals. Knowing, by heart, your average pulse and BP will help you know if you are remaining safe.

Here are a few basic tests that stroke survivors can do to keep track of the health of their arteries:

• Take your blood pressure. Digital blood pressure machines are inexpensive and easy to use. Bring your machine into your doctor’s office to judge the machine’s accuracy. Compare the doctor’s reading against what your machine says. Your doctor will tell you what normal blood pressure is for you; normal varies from person to person depending on a number of factors, including the effects of certain medications.

• Take your pulse. (Many digital blood pressure monitors take pulse as well.) Here is how to take pulse: Look at a clock with a second hand. Place the tips of your “good-side” index and long fingers on the palm side of your other wrist, below the base of the thumb. Press lightly with your fingers, feeling the pulsing with your fingertips. Count the number of beats for 15 seconds. Multiply the number of beats by four. The number you come up with is your pulse per minute.

• Ask your doctor what a “good” pulse rate should be under two conditions:

— The highest pulse you can safely maintain during exercise. Much of what is suggested in this book is aerobic exercise (exercise involving the heart and lungs) and aerobic exercise increases heart (pulse) rate. Knowing the safe range of pulse rate will not only keep you safe, but can be used as a training tool. The key to maintaining an optimal pulse rate during exercise is challenging but safe. You want to challenge the heart (so it will get stronger) but keep your pulse rate in a safe range.

— Your average pulse when you are resting. Resting pulse rate is best done before you get out of bed in the morning. Resting heart rate is an important indicator of overall cardiovascular (heart and lung) health.

• Have your cholesterol checked by a doctor. It is a blood test. There are at-home blood tests, but their accuracy may be questionable.

• Monitor blood sugar. You can do this even if you are not diabetic but suspect something may be wrong with your blood sugar. There are inexpensive, over-the-counter blood sugar tests at your drug store.

• Take your waist-to-hip ratio. Waist-to-hip ratio is the best predictor of cardiovascular death. Central obesity (carrying fat around the middle, or an apple-shape, where the waist is larger than the hips) increases the risk of stroke, heart disease, high blood pressure, and diabetes. Carrying fat in the hips and thighs, or having a pear shape, is not as harmful to your health. You can calculate your waist-to-hip ratio by dividing your waist measurement by your hip measurement.

— Waist: Relaxed, measured around at belly button.

— Hips: Measure around the widest part of the hip-bones.

— For instance:

— Measurement at the waist = 34

— Measurement at the hips = 37

— 34 ÷ 37 = 0.92

— Ratios above 0.80 for women and 0.95 for men increases the risk of stroke, heart disease, high blood pressure, and diabetes.

What Precautions Should Be Taken?

Home tests are great. They are convenient, and they tell you what you need to know. But these tests are done most accurately when skilled healthcare professionals do them. Lack of accuracy of machines, as well as poor collection techniques, can provide false readings. If you suspect that a reading (pulse rate, blood pressure, etc.) is cause for concern, contact your doctor or call emergency services (911).