Lecture 9

15 DECEMBER 1933

SUBMITTED QUESTIONS

The first correspondent, a lady blessed with steady good fortune, is indignant that my lectures are so popular! 261

There are quite a number of reactions from younger members of the audience that have confirmed my worst fears. I would have spoken over the top of their heads, and they could not imagine for which reasons I have discussed at length such a curious case as that of the Seeress, which evidently dates from the last century! 262

I chose this case with a secret intention in mind. In so doing, I have espoused standard clinical methodology by selecting a classic example of an illness, offering a general description, and thereafter discussing the entire symptomatology and pathology of the illness based on the example. The case of the Seeress is an indisputably classic empirical example, and therefore allows us to consider certain basic facts. I have gone to some lengths to set out the details of the case to help you attain a clearer sense of the various phenomena involved.

Should the case strike you as unfamiliar or strange, then you would do so on account of your lack of knowledge. You are simply unaware that your own case exhibits all these basic facts, too, only they lie concealed in the dark background of your psyche. You have no knowledge of them, that is all. We must become better acquainted with some of the general features of the human psyche. This human psyche is nothing well-known, indeed it constitutes a great unknown. The ideas that I have set forth in my lectures on the basis of this case have already been published, and I am not to blame if these are not more widely known! For the moment, I shall not further discuss this. Bear with me as I proceed with my discussion of this case to a satisfactory conclusion, in order to alleviate for you some of the burden of misapprehension.

***

In the previous lecture, I highlighted the three characteristic phenomena:

1. extrasensory perceptions;

2. ghosts and specters;

3. the peculiar “sun-sphere.”

With regard to these extrasensory perceptions, let us just assume that some of these curious facts about clairvoyance really apply. We must not let ourselves be deterred by superstition and fraudulent trickery. We can no longer ascertain the facts in the preceding case, but I have observed countless times that dreams and premonitions presaging the future do exist. We all know that, after all. One can even experiment with these matters, even in company, as I have done on countless occasions. They always happen whenever a person, like the Seeress, directs their entire attention inward, instead of outward. Then such dreams, premonitions, and perceptions occur that border on extrasensory perception. This is simply a fact, a quite uncomfortable fact, it is true, but nevertheless we must put up with it. It is my pleasure to admit as much. Unlike others who, for the sake of a theory, simply deny a whole bothersome part of a science and leave its treatment to the poets, I for one cannot allow myself that! If you so wish, I can give you my word of honor that such matters exist, and we can thus incorporate them in our conception. I am relating the case of the Seeress for precisely this reason. We thus face a most unpleasant and uncanny matter.

As a consequence, we must also defy the concepts of space and time. Of course, this relativization of time and space is unbearable for some mediocre brains, and is therefore simply denied. Such matters, however, do occur, wicked though this seems, and it is up to us to engage with them!

Already before our time, many of the brightest minds have found that, regarding time and space, things are not quite as they seem, that it is at least admissible to doubt the absoluteness of these dimensions. Kant, for instance, had serious doubts about these dimensions. He maintained:

Space is a necessary representation, a priori, that is the ground of all outer intuitions. One can never represent that there is no space, though one can very well think that there are no objects to be encountered in it.

Space, he further asserts, is “a pure intuition,” that is, “an a priori intuition” 263 that “grounds all concepts of it.” 264 It has empirical reality; is the shape that all outer experience assumes.

Time, according to Kant, “is the a priori formal condition of all appearances in general.” 265 In contrast to space as an external sense, time, as an internal sense, possesses “subjective reality.” 266 Time in itself does not exist, because “time is nothing other than the form of inner sense, that is, of the intuition of our self and our inner state.” 267 Sustaining a fundamental objection against this view will prove to be very difficult. Modern physics, as you are aware, has also come into conflict with these a priori concepts.

If time and space are relative dimensions, they cannot have absolute validity. Consequently, we must assume that an absolute reality has different properties from our spatial-temporal reality: in other words, there exists a space that is unlike our space, and a time that is unlike our time. That is, it is possible for phenomena to occur that are not subject to the conditions of time and space.

Please bear in mind that psychic matters are neither thick nor thin, neither big nor small, neither round nor squared, neither heavy nor light, and so on, but exquisitely non-spatial; and secondly, that it is forbiddingly difficult to determine a time of the psyche. You will find it almost impossible to establish any time in which a psychic process occurs. You can measure response times, but what prevails is an enormously complex magnitude that consists of a whole array of quite unknown figures. In contrast, we have all had the strangest experience that under certain circumstances psychic processes require incredibly little time, for instance in so-called arousal dreams.

An example: a lengthy dream begins in times of peace; thereafter, we hear reports that war is imminent; heated debates for and against an armed conflict ensue, and the likelihood of hostilities intensifies. Newspapers report that deeds of war have been committed. Military personnel gathers, cannons are wheeled into position, suddenly heavy artillery guns begin to fire at rhythmic intervals, and eventually one awakes at someone knocking on the door. 268 Later, the dream can be described at length and in great detail, but in reality it lasted only for a very short time. Did this endless dream happen between the first knock and the last, then, or did it start earlier and lead up to the moment of the knocking from an anticipatory knowledge of the very second in which the knock at the door would occur? Of course, what the dreamer associates to such a dream is important, and the physician must pay attention to it. It is not necessarily the case that the contents of the dream were contingent upon the knocking on the door. One can also analyze such a dream, and discover that it springs from quite specific psychic conflicts.

Likewise, the fate of a poor soul being beheaded in a dream, whereby the decapitation was in actual fact a part of the four-poster bed crashing down and striking the dreamer on the neck under the chin. It seems as if the dreamer had anticipated this event. 269 Or the well-known fact that people review their whole lives while falling down a mountain or while drowning, often reported by those who were saved. For instance, the admiral who took a false step. 270 Another case is Professor Heim, who once fell down a mountain and revisited his entire life during the fall. 271 Such cases seem to suggest that in certain circumstances the psyche needs only an unimaginably small amount of time.

We may now cite the positive evidence for the existence of nonspatiality, namely, when I can see through thick walls. In any event, we are touching upon a mode of existence that fails to coincide with empirically perceptible reality.

This point is most important with regard to the psychic being. I discussed the example of the “Seeress of Prevorst” for this very purpose—in order to show you how such great introversion results in the manifestation of the characteristic features of the psychic background, to the extent that the characteristics of consciousness completely vanish. These matters are by no means extraordinary, by the way. In theory, at least, each of you can have premonitory dreams. Generally, however, these are so insignificant that they are not noticed, but this is due to the ignorance of people. I myself was also so totally ignorant, but in the meantime I have known such cases for thirty years, and have published them, and if people don’t know this it’s certainly not my fault!

Another example is Dunne’s An Experiment with Time (1927). 272 He was based in South Africa at a place where he received a mail delivery only every two months. On the eve of one particular delivery, he dreamt that he was reading a report about the disaster of St. Pelée in the Daily Mail or Telegraph, and was struck by a headline in bold print: “Disaster in Martinique destroys entire city, leaving 4,000 dead.” The paper arrived the next day; he opened it eagerly and obviously it contained the report. But now to the most interesting aspect: Firstly, Dunne did not have his dream when the volcano erupted, and secondly he anticipated not the event but effectively a misprint. The next edition of the newspaper included the correction: 40,000 killed. 273 To Dunne, time is like a filmstrip, and the present is an observation slit; by mistake, it can happen that we merely look past the slit and see something which does not yet exist, that is to say, although it exists already as such, we cannot see it yet. Past events, too, can be seen in this way by looking past the time slit. 274 The actual soul, the objectively psychic, thus possesses qualities that border on nonspatiality and atemporality.

The second peculiarity is that the psychic background projects so-called ghosts. Naturally, we have no means at all of proving that ghosts exist. Like clairvoyance, this is a very complicated matter. At first, ghosts are no more than heterologous images of persons—with completely different faces and figures—quite often of persons who are no longer alive, whom one did not know, and whom the Romans called imagines et lares. 275 The Romans used the term imago to express the subjective nature of these images. The Seeress had to have all the souls of her ancestors within her in order to feel well. These are inner images, so-called autonomous contents; they are autonomous, because these contents do not obey conscious intentions, but instead come and go as they please.

Now obviously you are bound to say: One does not have such things! Often, however, you yourself will say: “It has suddenly occurred to me,” or such and such a thing has “just come into my mind.” If you were Mrs. Hauffe, it would be a ghost addressing you. If you are slightly psychotic, then it is a voice that speaks behind you. “These thoughts have all been stolen from me, and now someone else is voicing them!” One man, for instance, used to hear a voice as loud and clear as a trumpet at nine o’clock in the evening; the voice would give an account of all his activities on that day. In another case, the voices read aloud all the company nameplates on this person’s way home in London. When something fails to work in our psychology, all these matters surface—matters that one does not believe one has perceived.

Once a patient was brought to me in a highly neurotic state, an eighteen-year-old girl who had enjoyed the best education, and led an extremely sheltered life. To the shock of her parents, when she was agitated she would utter a flood of the most incredible expletives, on which even a wagoner could have prided himself. “Could you please explain how on earth this child knows such foul-mouthed language!” Now I couldn’t tell them where exactly the girl had picked up those expressions, but the fact is that she had actually heard them, be it from a cabman on the street, be it from other kids, etc. We have a very high threshold of consciousness. Our consciousness can be aroused only by phenomena that possess sufficient energy; everything else does not become conscious, although it is perceived. It is like sound vibrations. Do you believe that sound ceases when you no longer hear it? If the light were suddenly to go out and you could no longer see me, you would not be likely to think that I had ceased to exist, yet it would be no more foolish to think so than to assume that the contents of the psychic background only exist when we can see them.

These phenomena point to the actual quality of the psyche. We learn from them that autonomous contents are one of the essential facts of the soul; that is, they are independent contents that abide by their own laws, and that come and go and produce characteristic moods. This is well expressed in our language. We say, for instance: “What has got into him again?” Or that someone is “possessed”—by a spirit, that is, or that he is “beside himself.” We also talk of “jumping out of one’s skin” or that someone is “bedeviled” by something.

The ancients understood this far better than we do; they did not speak, therefore, of being in love, but of being possessed or hit by a God. We not only experience these psychic contents as a state of possession, but also as a sense of loss, for the unconscious can steal away fragments of our conscious psyche and rob us of our energy. This is what happens when we say that we would not be “in the mood” for something or other. The primitive would say that a spirit—possibly one of the ancestral souls whose presence he must sense to feel at ease—“has gone forth” and left him. The souls of the ancestors—these are autonomous contents, hereditary contents, of which your soul consists. Is it not true that you have your grandmother’s nose, and so forth? It happens that one will suddenly hear a terrible din in a native village. A Negro is lying on the ground, beating himself. It is clear to everybody that a spirit has left him, a spirit he cannot do without, however, and that he tries to call back. “His soul has gone astray.” It is as if he were seeking to remember himself, thereby causing him to inflict pain upon himself. Quite like when one grows restless in a boring lecture.

We cannot escape being influenced by psychic contents, it is our natural condition. Therefore I always feel very suspicious when somebody assures me that he is completely normal. It is well established, however, that very “normal” people are compensated madmen. Normality is always slightly suspicious. I’m not just joking, but this has been the bitterest experience of my life. 276 Generally, it suddenly becomes evident that some madness lies concealed beneath their cursed normality. The truly normal person has no need to be always correct, or to stress his normality. He is full of mistakes, commits follies, lacks modesty, and does not hold normal views.

When someone runs around strangely among primitives, eating only grass and so forth, he is said to be “possessed,” that is, by the devil. “Here we go again,” is the response, or one would like to “jump out of one’s skin,” if only one could. It is a like a soul jumping out of the skin. We are “possessed” when a soul enters, and “jump out of our skin” when a soul leaves us. It is these autonomous contents that lead to so-called possession. Even the most normal person can be possessed, by an idea, for instance, or a conviction, or an affect.

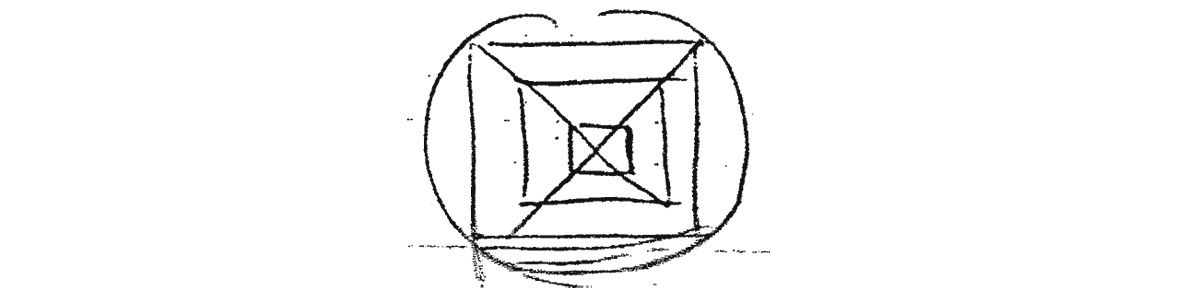

Now to the third phenomenon, the peculiar circle. This is the most curious phenomenon of all. Unfortunately, this fact is completely unknown. I fear, however, that you have to grow accustomed to these matters, even to those you know nothing about yet. I exercise caution in these matters, and have therefore chosen a case in which I was not involved in the least; otherwise, one would say again: “Well, of course, he simply influenced the patient’s mind!” This is about a basic fact, one which has received merely scant attention to date. It is nothing other than an absolutely basic fact about the human soul; it is known all over the world and, if we do not know it, then we are the morons! 277

I myself have witnessed a case where this phenomenon occurred. This was a girl aged sixteen who exhibited this phenomenon whom I observed almost thirty-seven years ago, in the final semesters of my university studies. I was completely ignorant of such matters at the time. She had drawn a circle on the basis of information that she had received from spirits. . . . 278

These reflections bring us to an instance of primitive psychology that is still apparent today—although perhaps not so much in this auditorium, but by all means with local councilors of various Swiss municipalities.

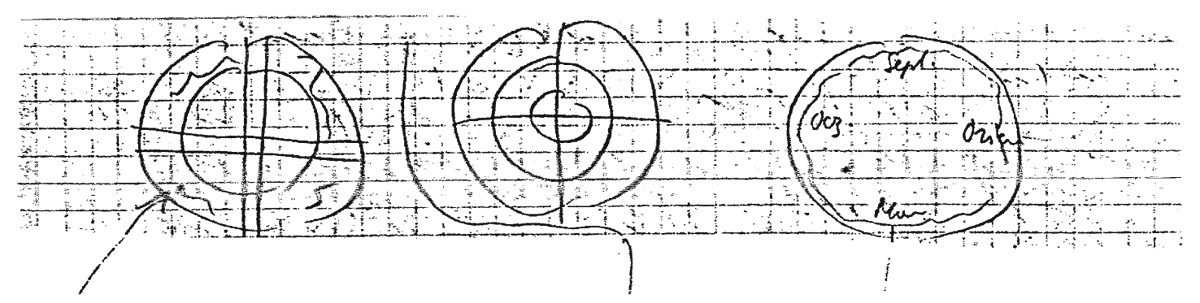

The next analogue of this circle is the so-called magic circle: Doctor Faust’s Coercion of Hell, 279 for instance, contains recipes for the invocation of ghosts. We have lost all knowledge pertaining to these matters. There are three circles that serve to ward off evil spirits rather than evil persons.

The first circle exhibits strict correspondence with the form of a cross; it bears inscriptions of names, as a rule the names of Hebrew Gods. In the second circle, the names of the Gods serve as a protective barrier against evil spirits. The third one also contains the names of Gods, arranged in circular fashion. Another popular form is the following:

Usually, the invocation of a ghost proceeds from the center, involving the recitation of the names of all Gods, of both the conscious and secret ones, of the four winds, and of the [sic]. Ordinarily, furthermore, the invocation is spoken at all four points of the compass rose: “I (my name) herewith bless and consecrate this circle in the names of the highest God. Ego . . . [sic] 280 who stand in this circle, so that the Almightiest God may bestow upon me and all others a shield and a defense against all evil spirits and their powers, in the name of God the Father ┼, the Son ┼, and the Holy Ghost ┼.” This simple onomastic formula is used to afford the circle magic potency.

This circle sprang from ancient customs, which are still practiced. For example, circumambulation: the ritualistic practice of circling on foot, clockwise and three times, whatever is to be banished or protected. When the Romans founded a city, they encircled the sulcus primigenius [original furrow]. A pit, known as the fundus, was excavated at the center; the temple, in which all kinds of objects were deposited, was built there. 281

The oldest depictions of circles, so-called sun wheels, date to the Paleolithic period. 282 Please note that wheels did not yet exist at the time; the first wheels appeared in the “Wooden Age.” 283 The oldest “sun wheel” is an octagonal cross, to which Frobenius already refers. 284 Also at the Swiss National Museum [Landesmuseum] in Zürich.

Encircling a municipality or property on horseback is an old magic custom serving its protection against evil spirits. 285 Sometimes, (chickens?) [sic] are (tended?) [sic] behind the so-called blocking chain [Sperrkette] about once a year: that is, a magic circle is drawn behind the chain beyond which the animals are not allowed to roam. Evidence from all over the world attests that the central cultic notions are furnished with this symbol.

There is a Chinese manala, in which cosmological forces emanate from the four ends of the cross.

In Egypt we find the same idea. The sun is positioned in the center, and around it are the four sons of Horus in quadratic order. Only one of these four figures has a human head, the other three have animal heads. This corresponds to the Christian symbol of the tetramorph—the cross with the four Evangelists, of whom only one has a human head. 286

The Mayan “Temple of the Warriors” was excavated a few years ago. Beneath the altar a mandala, consisting entirely of cut turquoises, was found encased in a limestone cylinder. It was bedecked with 3,000 turquoises. It is kept at the Museum of Mexico City. 287 In the four main points comes the feathered serpent 288 and opens its mouth inward. This serpent adorns the robes worn by priests to this day, and it has a spellbinding effect in that whoever looks at it is enchanted. [It is] The object of concentration. Whoever succeeds in placing themselves in this circle is protected against evil spirits.

In India: 289

In Tibet:

right inside: a precious object, a symbol of—or the image of the highest Goddess.

Circle: a pagoda with four entrances

Paramahansa, see Paul Deussen p. 703, Zentralbibliothek [main library]. A conversation found in the Para[mahansa] Upanishads: 290

The Pupil asks: At whose wish does the mind sent forth proceed on its errand? At whose command does the first breath go forth? At whose wish do we utter this speech? What God directs the eye, or the ear?

The Teacher: It is the ear of the ear, the mind of the mind, the speech of speech, the breath of breath, and the eye of the eye.

[sic] is not expressed by speech and by which speech is expressed, that alone know as Brahman, not that which people here adore.

The Kena Upanishad of Sâmaveda (its older name is Talavâkara Upanishad, since it originally belonged to either the Brâhmana estate of the Talavakâra or Saiminêya). 291

First Khanda

1. The Pupil asks: “At whose wish does the mind sent forth proceed on its errand? At whose command does the first breath go forth? At whose wish do we utter this speech? What God directs the eye, or the ear?”

2. The Teacher replies: “It is the ear of the ear, the mind of the mind, the speech of speech, the breath of breath, and the eye of the eye. When freed (from the senses) the wise, on departing from this world, become immortal.

3. The eye does not go thither, nor speech, nor mind. We do not know, we do not understand, how any one can teach it.

4. It is different from the known, it is also above the unknown, thus we have heard from those of old, who taught us this.

5. That which is not expressed by speech and by which speech is expressed, that alone know as Brahman, not that which people here adore.

6. That which does not think by mind, and by which, they say, mind is thought, that alone know as Brahman, not that which people here adore.

7. That which does not see by the eye, and by which one sees (the work of) the eyes, that alone know as Brahman, not that which people here adore.

8. That which does not hear by the ear, and by which the ear is heard, that alone know as Brahman, not that which people here adore.

9. That which does not breathe by breath, and by which breath is drawn, that alone know as Brahman, not that which people here adore.”

Second Khanda

1. The Teacher says: “If thou thinkest I know it well, then thou knowest surely but little, what is that form of Brahman known, it may be, to thee?”

2. The Pupil says: “I do not think I know it well, nor do I know that I do not know it. He among us who knows this, he knows it, nor does he know that he does not know it.

3. He by whom it (Brahman) is not thought, by him it is thought; he by whom it is thought, knows it not. It is not understood by those who understand it, it is understood by those who do not understand it.

4. It is thought to be known (as if) by awakening, and (then) we obtain immortality indeed. By the Self we obtain strength, by knowledge we obtain immortality.

5. If a man know this here, that is the true (end of life); if he does not know this here, then there is great destruction (new births). The wise who have thought on all things (and recognized the Self in them) become immortal, when they have departed from this world.” 292

261. I.e., intelligible to the general public, in layman’s terms. This refers to the following letter: “Zurich, 10 Dec. 1933. Dear Doctor, At our short encounter after your lecture about a fortnight ago you asked if your explanations would be popular enough. In the meantime, I have now heard from a number of people, students and people who have their feet on the ground, how they find your lectures. Surely you will be interested in learning what a small part of your large audience thinks. All of them find that the lectures are too popular. Not all of these people are specifically knowledgeable in psychology. Surely you will be relieved to know, since you are used to talking before a highly educated audience, that your very interested and attentive listeners can still follow you even if the basic concepts are explained at somewhat less length. In hoping that I could render you, dear Doctor, a small service with these lines, I remain, yours, Doris Schlumpf” (ETH Archives).

262. This could refer to some reactions of students, gathered and summarized by a participant named Otto (ETH Archives; undated). They concur that the lectures did not meet their expectations, specifically, that the topics were too far-fetched and historical, and that Jung would not talk about contemporary problems and his own psychological theory. Jung also mentions similar complaints at the beginning of the thirteenth lecture; see pp. 106–107.

263. Original: Anschauung. The editors and translators of the authoritative English edition, Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood, translate this by “intuition,” based on the fact that, in his (Latin) inaugural dissertation, “Kant uses the Latin word intuitus to signify the immediate and singular representations offered by the senses. . . . In the Critique of Pure Reason, he will employ the analogously formed German word Anschauung for the same purpose” (Kant, 1781/1787 [1998], p. 709).

264. Ibid., A24, A25. Kant’s book is usually quoted according to the so-called A/B system, “A” standing for the first, “B” for the second, revised and enlarged edition, followed, also in English texts, by the pagination in the standard German edition of Kant’s works, the so-called Akademie edition.

265. Ibid., A34.

266. Ibid., A37.

267. Ibid., A33.

268. In October 1938, Jung used this and the following examples also in his keynote lecture on the method of dream interpretation during his seminar on children’s dreams. There he revealed that his first example is in fact a dream he had had himself, and gave more details: “As a university student I had to get up at half past five in the morning, because the botany lecture started at seven o’clock. This was very tough for me. I always had to be awakened; the maid had to pound at the door until I finally woke up. So, once I had a very detailed dream. I was reading the newspaper. It said that a certain tension between Switzerland and foreign countries had arisen. Then many people came and discussed the political situation; then there came another newspaper, and again it contained new telegrams and new articles. Many people got excited. Again there were discussions and scenes in the streets, and eventually mobilization: soldiers, artillery. Cannons were fired—now the war had broken out—but it was the knocking on the door. I had the clear impression that the dream had lasted for a very long time and come to a climax with the knocking” (Jung, 1987 [2008], pp. 8–9).

269. This is “an example from the French literature: Someone is dreaming: He is in the French Revolution. He is persecuted and finally guillotined. He awakes when the blade is sliding down. This is when a part of the frame of the canopy fell on his neck. So he must have dreamed the whole dream at the moment when the frame went down” (ibid., p. 8). Maury describes this dream of his and the incident in detail in the sixth chapter of his book on Sleep and Dreams (1861).

270. “The same is told in the story of a French admiral. He fell into the water and nearly drowned. In this short moment, the images of his whole life passed before his eyes” (Jung, 1987 [2008], p. 9).

271. Albert Heim (1849–1937), Swiss geologist, known for his studies of the Swiss Alps, professor of geology at the ETH (1873). “During the few seconds of his fall,” he “saw his whole life in review” (ibid., p. 9).

272. Dunne, 1927. John William Dunne (1875–1949) was an Anglo-Irish aeronautical engineer who pioneered the development of early military aircraft. After experiencing an anticipatory dream, he became strongly interested in parapsychology and the nature of time.

273. See ibid., pp. 34–38. Jung here gives, in fact, a garbled rendition of Dunne’s account. Dunne did not dream of reading a newspaper report, but of actually being on a volcanic mountain that was about to erupt and destroy the whole island on which it was standing, and with it its 4,000 unsuspecting inhabitants: “All through the dream the number of the people in danger obsessed my mind. I repeated it to every one I met, and, at the moment of waking, I was shouting to the ‘Maire,’ ‘Listen! Four thousand people will be killed unless—’ ”. When Dunne received the newspaper with the news of the catastrophe some time later (in his book he did not remember how long afterwards), the headline was: “Probable Loss of Over 40 000 [sic] Lives.” He, however, read the number as 4,000, which number he also always quoted when telling his story later. Only when he copied out the paragraph fifteen years later did he realize that it was actually 40,000. It turned out, in addition, that the actual number of casualties, as found out later, did not coincide with that number. In his 1952 paper on synchronicity, Jung referred again to this episode, this time giving a correct version (§§ 852–853).

274. This analogy with the filmstrip and the observation slit is Jung’s, not Dunne’s. The latter wrote, for instance, that “one had merely to arrest all obvious thinking of the past, and the future would become apparent in disconnected flashes,” or that dreams in particular enjoy “a degree of temporal freedom” (1927, pp. 87, 164).

275. Jung’s own concept of the imago (what he later termed archetypal image) “has close parallels in . . . the ancient religious idea of the ‘imagines et lares,’” that is, cult statues/images and tutelary Deities of home and hearth (Transformations, orig. Germ. ed. p. 164, also in CW 5, § 62 and note 5).

276. Sidler made a note: “Meaning: When Jung thinks to have finally found a ‘normal’ follower or pupil it turns out that some kind of madness lurks behind his cursed normality.”

277. Here all extant lecture notes, with the exception of Sidler’s, break off. As we know from a letter of a participant, Arthur Curti, Jung overran his allotted time past 7 p.m., and the majority of the audience left or had to leave at this point (letter of 19 January 1934; ETH Archives; see the beginning of lecture 11 and note 297). Sidler’s notes on the rest of the lecture are very sketchy, however, sometimes to the point of unintelligibility.

278. At the time (that is, around 1895/1896), Jung experimented with his cousin Helene Preiswerk, the person he is referring to here, and who was the subject of his doctoral dissertation (1902). Sidler’s notes on Jung’s presentation of these circles are so fragmentary and obscure that they have been omitted here. The reader will find a reproduction as well as a detailed description and discussion of these circles in ibid., §§ 65 sqq.

279. Dr. Johann Georg Faust (ca. 1480–ca. 1540), itinerant alchemist, astrologer, and magician, a legendary figure about whose life hardly any facts are known with certainty. He became the model for various literary works on the Faust theme, among them Goethe’s play. Various so-called Höllenzwänge (e.g., Faust, 1501) are ascribed to him. A Höllenzwang (“Coercion of Hell,” or “Hell-Master”) is the designation or the title of grimoires, or spellbooks, that describe rites or incantations with which the demons of Hell can be forced to obey the commands of the magician.

280. The notetaker did not catch all of this phrase.

281. Jung alluded briefly to this tradition in his commentary on The Secret of the Golden Flower (1929, § 36), but gave the most detailed description in his seminar on Dream Interpretation Ancient & Modern (2014, p. 213): “Jung: What was done when the [ancient Roman] city was founded? Participant: One walked around the temenos [a protective piece of land set apart as a sacred domain, a sacred precinct or temple enclosure, set off and dedicated to a God]. Jung: How was that done? Participant: By circumambulations. Jung: Yes, and with what? Participant: With a plow. Jung: Yes, it was used to plow the sulcus primigenius [a magical furrow around the center of the temple temenos]. This was a mandala; and what was done in the middle of this plowed up area? Participant: Fruits and sacrifices were buried. Jung: At first a hole, the fundus, was made, and then sacrifices to the chthonic Gods were put into it; in other words, the center was accentuated.” Jung seems to allude to the older Roman method of surveying field boundaries and building sites described by Pliny in the Natural History (Book III). Cf. Rykwert, 1988.

282. I.e., the earliest period of the Stone Age, lasting until circa 8,000 BCE.

283. Jung’s neologism.

284. Leo Viktor Frobenius (1873–1938), German ethnologist, archaeologist, and explorer, and a leading expert on prehistoric art and culture. He organized twelve expeditions to Africa between 1904 and 1935. In 1920, he founded the Institute for Cultural Morphology in Munich. Frobenius, and in particular his book, Das Zeitalter des Sonnengottes [The Age of the Sun-God] (1904), was a major source of reference for Jung, above all in Transformations.

285. Jung may also have had in mind the so-called Bannumritt, a tradition to this day in rural areas around his hometown Basel. In circling their communities, the inhabitants fire from old muskets.

286. Jung repeatedly pointed out the connections between Horus and Christ, and the depictions of the sons of Horus and the Christian tetramorph; see in particular Jung, 1945a, §§ 360 sqq.; 1951, §§ 187 sqq.

287. In his seminar on dream analysis, in the session of 13 February 1929, Jung gave a more detailed description of this discovery (actually not an excavation) at Chichén Itzá, closely following the account published in the Illustrated London News of 26 January 1929, which he had evidently read: “An American explorer has broken through the outer wall of the pyramid and discovered it was not the original temple; a much older, smaller one was inside it. The space between the two was filled with rubbish, and when he cleared this out he came to the walls of the older temple. Because he knew that it had been the custom to bury ritual treasure under the floor as a sort of a charm, he dug up the floor of the terrace and found a cylindrical limestone jar about a foot high. When he lifted the lid he found inside a wooden plate on which was fixed a mosaic design. It was a mandala based on the principle of eight, a circle inside of green and turquoise-blue fields. These fields were filled with reptile heads, lizard claws, etc.” (Jung, 1984, p. 115). The inner temple is called the Temple of the Chac Mool. The archeological expedition and restoration of this building were carried out by the Carnegie Institute of Washington from 1925–1928. A key member of this restoration was Earl H. Morris who also published the work from this expedition (1931).

288. The feathered serpent was a major deity of the ancient Mexican pantheon.

289. The following section is incomplete in the notes.

290. Deussen’s translation: Sechzig Upanishad’s des Veda (1897; 2nd ed. 1905, 3rd ed. 1921).—The Paramahansa Upanishad describes the conversation between Sage Narada and Lord Brahma about the characteristics of a Paramahansa. The latter is a Sanskrit religio-theological title of honor applied to Hindu spiritual teachers of high status who are regarded as having attained enlightenment. The following fragmentary notes, however, do not refer to the Paramahansa Upanishad, but to the Kena Upanishad, which Sidler then probably copied in full from the Deussen translation only after the lecture and attached it to his notes.

291. This explanation was obviously added by Sidler.

292. There are many different translations of the Kena Upanishad into English. I have chosen the one at http://www.tititudorancea.org/z/kenaupanishad_talavakara_1.htm.