![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

What happens if you find a lump in your breast or if a mammogram or another test shows an abnormality? Although this may suggest the possibility of cancer, it doesn’t automatically mean that you have cancer. It does indicate, though, the need for further tests to determine what the lump or abnormality is. This is called the diagnostic process.

The evaluation of a new breast lump often involves a number of steps, including asking about your signs and symptoms, if you have any; examining your breasts; reviewing the results of imaging tests; and, ultimately, the removal and examination of a sample of cells from the abnormal area (biopsy). If cancer is present, other tests are typically performed. These tests can help determine if the cancer has spread to other parts of your body, and they can identify certain characteristics of the tumor that may help you and your doctor decide on the type of treatment you should receive.

The diagnostic process may take several days. This is often a time of great uncertainty and emotional stress. Not knowing whether you have cancer can sometimes be worse than knowing that you do. Knowledge allows for action. Uncertainty hinders your ability to plan and move forward, causing anxiety.

This is precisely why diagnosis is so important. An accurate diagnosis is key to your plan of action, and getting the diagnosis right often takes more than one test. Waiting for the results can be difficult. It might help to use this time to learn more about breast cancer and how it’s treated. This way, if the tests reveal cancer, you’re more prepared for what comes next. At the same time, remember that noncancerous (benign) breast conditions are far more common than cancerous (malignant) ones.

The most common sign of breast cancer is a lump (mass) or thickening in one breast that can be felt (palpated). Often, the lump is painless, but occasionally it may be associated with pain or tenderness. A lump that’s cancerous is usually firm to hard and it may have irregular borders, although some cancerous lumps are more soft and rounded. Most tumors develop in the upper outer portion of your breast, close to your armpit.

A tumor that can be felt (a palpable mass) is most often discovered by a woman herself, either by accident or through breast self-examination. Sometimes a feeling of discomfort or a bump to a breast may draw attention to a lump. Less often, a lump is discovered by a partner during lovemaking or by a doctor during a routine physical exam.

Even an experienced doctor can’t reliably distinguish between a noncancerous (benign) lump and a cancerous one based on a physical exam alone. That’s why all lumps and physical changes to the breast need to be evaluated with imaging tests.

In addition to a lump, other signs and symptoms may include:

In the earliest stages of breast cancer, and even in some of the later stages, there are no signs or symptoms. This is where screening mammography becomes helpful. A mammogram may reveal a lump or abnormality that can’t otherwise be visually or palpably detected.

If there’s any suspicion of breast cancer, one of the first things your doctor likely will do is get your complete medical history, if he or she doesn’t already have it. Most women who develop breast cancer don’t have risk factors for the disease, but information about your health may help your doctor assess your situation.

Your doctor may wish to gather information regarding:

Your doctor may use the Gail model risk assessment described in Chapter 4 or another method for evaluating your risk. He or she may also want to see previous mammograms and ultrasound examinations of your breasts. This may help provide a frame of reference for the current evaluation.

After gathering as much information as possible about your personal and family medical history, an examination of both of your breasts usually follows. This is known as a clinical breast examination. While you’re seated facing your doctor, he or she may visually inspect your breasts, making note of any differences between the two, any scars, skin redness or signs of skin dimpling or nipple inversion. Some lumps aren’t immediately apparent in a normal seated position, so you may be asked to place your hands on your hips and then raise your arms above your head so that your doctor can see your breasts from different angles. Your doctor may also feel your armpits and the area around your collarbone to check for enlarged lymph nodes.

Next, you may be asked to lie down while your doctor examines your breasts, using a similar technique to that used for breast self-examination (see How to do a breast self-exam). This way, your doctor can evaluate the size, shape and firmness of any noticeable lumps or masses. Your nipples may also be examined for asymmetry, inversion, irritation and discharge.

If your signs and symptoms are suggestive of cancer — even if prior mammograms have been normal — it’s likely your doctor will recommend additional tests. For women age 30 and older, this may be a diagnostic mammogram.

Further testing is often based on the results of the mammogram. If you’re under age 30, your doctor may recommend an ultrasound because at a young age dense breast tissue may prevent a mass from being seen on a mammogram. An ultrasound helps determine whether a mass is solid or fluid-filled (cystic). If the mass is solid, a biopsy procedure — usually a core needle biopsy — may be performed.

If you don’t have any signs or symptoms but your screening mammogram suggests a suspicious abnormality, further testing is typically recommended, usually in the form of a diagnostic mammogram, an ultrasound or a biopsy.

The benefit of imaging tests is that they may be able to locate tumors deep within breast tissue that can’t be felt. They can also show whether there’s more than one suspicious area. Imaging tests may also be used to guide a needle biopsy procedure.

The most common imaging tests used in the diagnosis of breast cancer are diagnostic mammography and ultrasound. Other tests, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and molecular breast imaging (MBI), sometimes are used. Positron emission tomography (PET) is rarely used to diagnose breast cancer, but it may be used once a diagnosis is made.

Diagnostic mammography

Diagnostic mammography may be used for several purposes — to assess signs and symptoms of breast cancer, to precisely locate or further evaluate an abnormality visible on a screening mammogram, and to follow up on women who’ve had lumpectomies for previous breast cancer.

Like screening mammography, diagnostic mammography consists of X-raying your breast. Diagnostic mammograms include more views than the standard two done during routine screening. For example, during a diagnostic mammogram, a spot compression view can focus pressure on the breast at the site of the abnormal tissue area (lump). This spreads out the breast tissue and allows for a better view of the lump or area of concern. A magnification view may zoom in on an area to bring out the details of a small mass or clusters of tiny, irregular calcium deposits (microcalcifications).

Before you’re scheduled for a diagnostic mammogram, your doctor may mark the site of the lesion on your breast so that the radiologist will know where to focus attention. Your radiologist may also ask you to point out where you’ve experienced any signs or symptoms. Often, both breasts are X-rayed so that they can be compared for symmetry. Ideally, current mammograms are compared with previous images to look for small changes in breast tissue.

Signs of cancer on a mammogram include dense masses with irregular borders, suspicious microcalcifications, tissue distortions and asymmetrical breasts. Typically, when a finding falls into Category 4 or 5 (see table below), a biopsy is done.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

INTERPRETING MAMMOGRAPHY RESULTS

The American College of Radiology has developed a system for interpreting mammograms that standardizes the results and provides doctors with consistent terminology with which to write their reports and make uniform recommendations to women. This reduces differences in interpretation and decreases the margin of error. The system is called the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) and is widely used. The BI-RADS system divides results into the categories listed below:

Category 0: Needs additional imaging evaluation

Category 0 is usually used to describe a screening mammogram in which a possible abnormality has been found. The evaluation is considered incomplete, and more testing is necessary to arrive at a definitive category (1, 2, 3, 4 or 5). Additional testing might include mammography with spot compression, magnification or special mammographic views, or ultrasound.

Category 1: Negative

There is nothing to comment on. The breasts are symmetrical, and no masses, architectural distortions or suspicious calcifications are present.

Category 2: Noncancerous (benign) finding

This also is a negative mammogram in that no cancer has been found, but the radiologist may wish to describe a benign finding present in the breast, such as a cyst, fibroadenoma, lipoma or other characteristic.

Category 3: Probably benign finding; short interval follow-up suggested

A finding in this category generally has a high probability of being benign. However, your radiologist may feel it’s better to be safe than sorry and recommend a follow-up mammography exam after a specified period of time, generally about six months.

Category 4: Suspicious abnormality; biopsy should be considered

A finding in this category doesn’t have the exact characteristics of cancer but it has a definite probability of being cancerous. A biopsy is often recommended.

Category 5: Highly suggestive of being cancerous (malignant); appropriate action should be taken

Findings in this category have a high probability of being cancerous, and they should be biopsied.

Category 6: Known biopsy; proven malignancy; appropriate action should be taken

This category is reserved for findings on imaging tests in which malignancy was proved by way of a biopsy before the test.

Adapted from the American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS), fourth edition, 2003.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Ultrasound

Ultrasound imaging is often used to further evaluate a finding, such as a mass, and to determine its characteristics. Benign masses, such as cysts and fibroadenomas, often have a characteristic appearance with ultrasound, and therefore a biopsy may not be needed.

Ultrasound technology, also referred to as ultrasonography or sonography, uses sound waves to create images of unseen areas within the body. A breast ultrasound works by directing very high-pitched (high-frequency) sound waves at the tissues in your breast. These sound waves bounce off the curves and variations of breast tissue and are visually translated into a pattern of light and dark areas on a screen. The patterns form a visual image of the tissue inside your breast.

During an ultrasound exam, a gel-like substance is applied to the skin over your breast. The gel acts as a conductor for sound waves, and it helps to eliminate air bubbles between your skin and the transducer. A transducer is a small hand-held probe that sends out the sound waves and records them as they bounce back. The person performing the exam (ultrasonographer) moves the transducer back and forth over your breast, directing the sound waves into the tissue and capturing the waves’ echoes. The returning echoes are digitally converted into black-and-white images on a screen.

A disadvantage of ultrasound is that it can’t reliably detect microcalcifications, which commonly accompany cancer. This is one of the main reasons this procedure isn’t used for screening. But ultrasound has several important uses in the diagnosis of breast cancer. They include:

A biopsy involves removal of a small sample of tissue for analysis in the laboratory. It’s generally the only way of knowing for certain that a suspicious lesion is cancer. It’s most often recommended after a physical examination and an imaging test have raised the possibility of cancer. Besides identifying cancerous cells, a biopsy can provide important information about the type of cancer you may have and whether it might respond to a special form of treatment, such as anti-estrogen therapy or therapy directed at HER2 receptors.

The three common types of biopsy procedures are fine-needle aspiration biopsy, core needle biopsy and surgical biopsy. Each has its own advantages and disadvantages, and in a given situation, one may be more appropriate than another.

The pages that follow describe each of the biopsy procedures. If you don’t understand why you’re having one type of biopsy instead of another, ask your doctor to explain his or her recommendation in greater detail.

Fine-needle aspiration biopsy

This is the simplest type of biopsy, and it’s most often used for lumps that can be felt. For the procedure, you lie on a table. A local anesthetic might be used. Sometimes an anesthetic isn’t used because it may cause more discomfort than the procedure. While steadying the lump with one hand, a doctor uses the other hand to direct a very fine needle — one more slender than that used to obtain a blood sample — into the lump. The needle is attached to a hollow syringe. Once in place, a sample of cells is collected in the syringe and the needle removed.

Your doctor may use this type of biopsy as a quick-and-easy method to distinguish between a cyst and a solid mass, avoiding a more invasive biopsy.

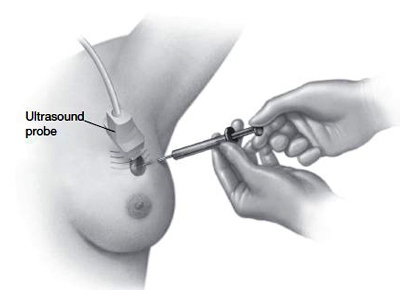

Image guidance

If the mass is hard to feel, your doctor may use ultrasound or mammography imaging to help guide the needle to the correct site. With ultrasound, your doctor can watch movement of the needle on the ultrasound monitor. When mammography is used, the procedure is called stereotactic biopsy.

Stereotactic methods are typically done with a larger needle (core needle biopsy), but on occasion they’re done by fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Two mammograms are taken from different angles, and the mass is mapped out by a computer, which guides the needle to the precise location. This procedure is described in more detail later in this chapter.

During fine-needle aspiration and core needle biopsies, a needle is inserted into the suspicious mass and tissue is removed for examination. A larger needle is used in core needle biopsy than in fine-needle aspiration. In both procedures, ultrasound may be used to guide the needle to the correct location.

Pros and cons

The advantages of fine-needle aspiration biopsy are that it’s quick, relatively inexpensive and fairly painless. It can be done in your doctor’s office, and often the results can be determined within the same day.

The accuracy of this procedure depends on the experience of the person performing the procedure. Studies have shown that experienced staff can produce very accurate results. Fine-needle aspiration biopsies performed by inexperienced staff, though, aren’t as reliable. Interpretation of the sample also requires special expertise.

A disadvantage of the procedure is that because only cells are obtained and not tissue, it may be more difficult to distinguish between noninvasive (in situ) and invasive cancer. As a result, many medical facilities in the United States prefer to use a core needle biopsy, which often can provide more definitive results.

Core needle biopsy

A core needle biopsy may be used on a mass that’s visible on a mammogram or ultrasound or that can be felt by your doctor or a surgeon. A core needle biopsy uses a larger needle than does a fine-needle aspiration. With this procedure, a small cylinder of tissue (core) is withdrawn from the mass rather than just cells, giving the pathologist more tissue to examine. In most cases, the procedure is performed under the guidance of a radiologist and with imaging equipment.

A core needle biopsy can provide a definitive diagnosis in most cases. It’s often the first procedure used to assess a new lump or an area of concern on a mammogram. A surgical biopsy is a more invasive procedure, so being able to perform a core biopsy may eliminate the need for a surgical biopsy. Any core needle biopsy carries a small risk of infection and bleeding.

Preparation

Before the procedure, tell your doctor if you’ve been taking aspirin or any blood-thinning medications. These can keep your blood from clotting properly during the procedure and may cause more bleeding. You may be asked to temporarily stop taking the medication. In addition, don’t wear deodorant, talcum powder, lotion or perfume the day of the test because they may interfere with imaging used during the procedure. You may also be asked not to eat for a certain amount of time before the test. Some facilities may request that you insert an ice pack in your bra after the procedure to reduce pain and swelling.

During the procedure

With all core needle biopsies, the site of the needle puncture is usually numbed with a local anesthetic. A small incision, approximately 1/8 inch to 1/4 inch, may be made to allow the biopsy needle to be inserted more easily. Depending on the type of biopsy, you might hear a quick popping sound as the device removes a tissue sample. Several samples of tissue are usually taken to ensure an adequate sampling. Generally, women don’t experience too much discomfort during the procedure. The tissue that’s removed is then sent to a pathologist for examination.

Although it takes only about 15 minutes to remove the tissue samples, the whole biopsy process, including all of the preparation, may take up to 90 minutes.

The process will vary some depending on the procedure you have.

Stereotactic core needle biopsy

With this procedure, you generally lie facedown on a padded biopsy table with one of your breasts positioned through a hole in the table. The table is usually raised several feet, and the radiologist sits below the table. Some facilities use a standing procedure similar to a screening mammogram. Your breast is then firmly compressed between two plates while mammograms are taken to determine the exact location of the lesion for the biopsy. It’s very important to keep still once your breast has been positioned so that the correct spot is biopsied.

Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy

During this procedure, you lie on your back on an ultrasound table. You may be asked to raise your arm over your head on the side of the breast to be biopsied. This allows stretching of the soft tissue so that the radiologist can get a better image of the abnormality. The radiologist then locates the mass with an ultrasound probe. Ultrasound guidance may be used if the abnormality can be clearly seen on an ultrasound image.

MRI-guided core needle biopsy

This type of core needle biopsy is done under the guidance of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) — an imaging technique that captures multiple cross-sectional images of your breast and combines them using a computer, to generate detailed 2-D pictures. During this procedure you lie facedown on a padded scanning table. Your breasts fit into a hollow depression in the table. The MRI machine provides images that help determine the exact location for the biopsy.

Pros and cons

The advantages of core needle biopsy over fine-needle aspiration biopsy include obtaining a larger sample for examination, the ability to distinguish noninvasive (in situ) cancer from invasive cancer, greater accuracy in diagnosis and better identification of breast calcifications in the tissue removed. Occasionally, a core needle biopsy may miss a cancer (false-negative result) or, very rarely, lead to a false diagnosis of cancer when, in fact, no cancer is present (false-positive result). The procedure is more expensive than is fine-needle aspiration. Nonetheless, core needle biopsy has become relatively standard. Individuals — both women and their doctors — like to know if cancer is present before surgery because it allows for better surgical planning.

Often, a tiny, stainless steel or titanium clip is inserted in the biopsy site within the breast to mark the spot of the biopsy, in case the area needs to be checked again later. The clip can only be removed surgically and is only visible with special equipment. It can’t be felt, and it doesn’t set off alarms at the airport.

Surgical biopsy

In some instances, the amount of tissue obtained with a needle biopsy isn’t enough, and a surgical biopsy must be performed. Or the suspicious mass is small and palpable, and your doctor may recommend both diagnosing and removing the mass in one procedure. In other situations, it may be determined that a relatively prominent lesion needs to be surgically removed, regardless of the needle biopsy results. Surgical biopsy may also be used if the location of the abnormality makes it difficult to use other procedures.

As its name implies, surgical biopsy involves minor surgery. You likely will be able to leave the hospital on the same day.

The two types of surgical biopsies are incisional and excisional:

Preparation

The procedure is usually performed in an operating room with sedation and a local anesthetic or, in some cases, under general anesthesia. Tell your doctor if you’re taking blood-thinning medications, including aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or any other medicines or herbal products that affect blood clotting. You may also be asked to not eat for a certain amount of time before the procedure. You’ll also want to arrange for someone to drive you home.

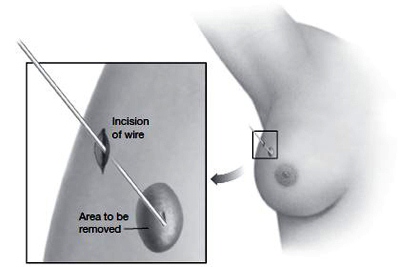

Wire localization

After a core needle biopsy, your radiologist may use a technique called wire localization to map the route to the mass for the surgeon. This is usually done immediately before surgery. For the procedure, you’re positioned for a mammogram, and the mass in question is located on a grid. Then a needle with an attached wire is inserted into your breast at a depth corresponding to the coordinates on the grid. You may be given a local anesthetic before the procedure, but sometimes the anesthetic can be more uncomfortable than insertion of the needle.

The tip of the wire is positioned within the mass or just through it. Two more mammographic views are taken to check the position of the wire. If necessary, the wire can be adjusted. After the correct positioning is obtained, the needle is removed and the wire is left in place. A hook at the tip of the wire keeps its position secure. A mammogram view of the wire is sent to the operating room.

Some medical facilities use radioactive seeds instead of wires. The surgeon is able to locate the area by using a probe that detects the radioactivity.

Sometimes, if ultrasound can provide a better view, a radiologist will use ultrasound instead of mammography to guide insertion of the wire.

Wire localization

In case of a lesion that can’t be felt, a tiny wire may be inserted in the breast through a small incision in the skin. With the aid of mammography, the wire is guided through breast tissue until its tip reaches the area in question. The surgeon then has good guidance as to where to remove tissue.

The biopsy

Once all of the preliminary steps are complete, your surgeon carefully examines the diagnostic images to decide on the best surgical approach. During surgery, he or she will attempt to remove the entire mass, along with the wire. The surgeon may mark the edges (margins) of the removed tissue (specimen) with sutures to orient the specimen for the pathologist. The specimen’s margins may also be marked with ink so that when cut open, the pathologist may determine whether cancer cells are at the margins.

The surgeon may have the tissue X-rayed before it goes to the pathologist to help determine if all of the calcifications are included in the sample. If the margins have cancerous cells (positive margins), this means that some cancer may still be in the breast and more tissue needs to be removed. If the margins are clear (negative margins), it’s more likely that all the cancer has been removed.

Occasionally, only by removing the breast (mastectomy) can the entire area of abnormal tissue be removed.

Risks and aftercare

The risks of surgical biopsy are similar to those of any minor surgery, including bleeding, infection and bruising around the site. You may find it best to take the rest of the day off and relax. For the next five to six days, avoid activities that may cause you discomfort.

You may shower or take a bath after the dressing is removed. The dressing is usually removed during a return appointment, or your surgeon may instruct you how to remove it a day or two after surgery. Minimal drainage is expected the first few days. A small gauze pad inside your bra may help absorb the drainage. A bra also provides support to the incision. Call your doctor if you develop symptoms of infection, such as foul-smelling drainage, increased swelling, redness or tenderness at the incision, or a fever.

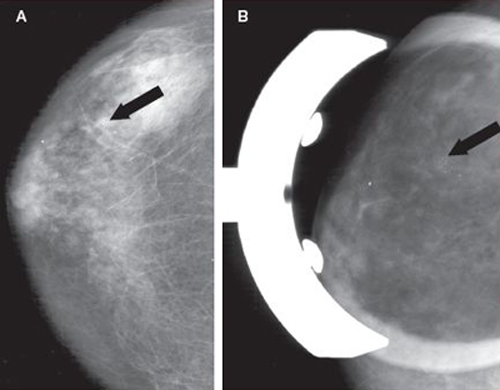

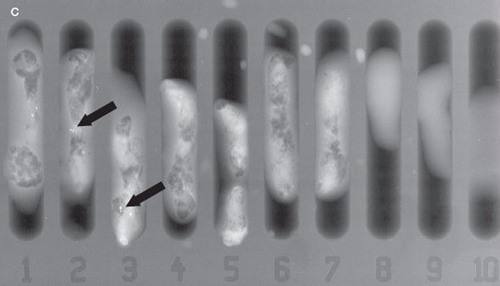

From Identification to Removal

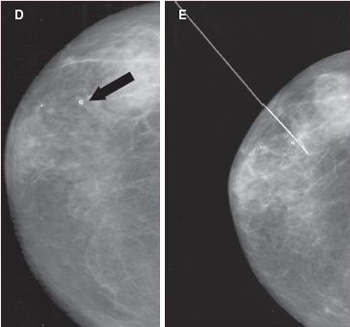

Image A is a screening mammogram indicating possible tiny, irregular deposits, called microcalcifications. Because the microcalcifications aren’t easily identified, a magnification view of the area is taken, as illustrated in image B. Here the microcalcifications can be seen more easily. A needle biopsy is then performed (see the illustration). Tissue samples taken from the area in question may be X-rayed to see if microcalcifications are present in the samples, as shown in image C. During the biopsy procedure, a small clip is placed in the location where the samples were taken, as shown in image D. Using the clip as a guide, a wire is then placed in the area to direct the surgeon where to remove additional tissue to help make sure all of the microcalcifications have been removed. This is shown in image E.

After a pathologist has studied the tissue that was removed, he or she writes up a detailed pathology report describing the specimen. The report may also list relevant parts of your medical history and any special requests to medical personnel.

It explains the site from where the specimen was taken and gives a description of what the specimen looks like to the naked eye. Its size, color and consistency may be noted. The pathologist should indicate whether cancer cells were present at the edges of the specimen (positive or negative margins) and what the noncancerous tissue looks like. He or she may also detail how many tissue sections of the specimen were taken for examination.

If cancer is present, a pathologist will outline a number of details about the cancer to help you and your doctor decide on the best type of treatment. These details include the type of cancer present (invasive or noninvasive), histologic type (ductal, lobular or special type), how abnormal the cancer cells appear (tumor grade), whether the tumor cells contain certain proteins called hormone receptors (estrogen and progesterone receptor status), and whether the tumor cells have a surface protein receptor called HER2.

![]()

QUESTION & ANSWER

Q: Why do I have to have the same test twice?

A: Findings from different diagnostic tests, such as your physical exam, mammogram and biopsy, may at times disagree. In some of these situations, one or more of the tests may need to be done again, or additional tests may be needed.

For example, if your physical exam reveals a mass that can be felt but a mammogram shows nothing, the mammogram may need to be repeated or another imaging test may be selected. Or if a mammogram indicates suspicious microcalcifications but your biopsy shows no abnormalities, your doctor may recommend a second biopsy to make sure the tissue area in question was actually sampled.

Type of cancer

By looking at the distribution of cancer cells in the specimen, a pathologist is able to tell if the cancer is invasive (infiltrating) or noninvasive (in situ). Invasive cancer spreads beyond the membrane that lines a breast duct or lobule, into surrounding connective tissue (see illustration). From there it’s able to travel (metastasize) to other parts of the body. Noninvasive cancer usually stays in one location, although it can become invasive. Noninvasive cancer has a much better projected outcome (prognosis) than does invasive cancer.

Invasive

The most common type of invasive cancer, which accounts for about 80 percent of all invasive breast cancers, is invasive ductal carcinoma. Invasive lobular carcinoma makes up about 10 percent of invasive breast cancers. The remaining 10 percent of invasive cancers are rare or special types.

Invasive lobular cancers can be particularly hard to detect with mammograms, and they may not be identified until they’re larger and can be felt.

Some of the special types of invasive breast cancer include medullary, tubular and mucinous breast cancers. These invasive cancers tend to have a better prognosis than does invasive ductal or lobular carcinoma and may be treated differently from the more common invasive cancers. Metaplastic cancer is a rare type of cancer, and it can behave more aggressively than does invasive ductal cancer.

Noninvasive

Noninvasive cancer (carcinoma in situ) is less common than is invasive breast cancer. Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), the most common type of noninvasive breast cancer, appears to be confined to the breast’s duct system, and it doesn’t invade the breast’s connective tissue (see Chapter 10).

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) begins in the lobules instead of the ducts. Most breast cancer specialists don’t consider LCIS to be a true breast cancer. But women with this diagnosis have an increased risk of developing future invasive cancer in either breast, not just the breast containing the LCIS (see Chapter 9).

With appropriate treatment and follow-up, both of these noninvasive conditions carry an excellent prognosis.

Tumor grade

In addition to determining what type of cancer is present, a pathologist also assigns a grade to the cancer. The grade is based on how normal or abnormal the cells appear when examined under a microscope. The lower the grade, the better the prognosis.

Pathologists generally use a grading system called the Scarff-Bloom-Richardson system, or some variation of this system, for grading invasive breast cancers.

In medical terms, the grade refers to the appearance of the cancer. It’s based on three features of the tumor: tubule formation, nuclear grade and mitotic activity. Each of these features is given a score of 1 to 3.

The scores of each of the three measurements are then added together to obtain an overall tumor grade — a total score of 3 to 9 points is possible:

Grade 1 implies the cells still look fairly normal, and the mass appears to be growing slowly. If the specimen is a grade 3, it means the cells have lost their proper structure and function, or they’re dividing rapidly, or both. Grade 2 cancers are in the middle — they aren’t as normal in appearance as grade 1, but they aren’t as abnormal as grade 3.

Hormone receptor status

Scientists have discovered that two female hormones, estrogen and progesterone, affect the growth of most breast cancers. One of the tests that’s often performed on a biopsy specimen is a hormone receptor test. A receptor is a cell protein that binds to specific chemicals, drugs or hormones traveling through the bloodstream.

Normal breast cells have receptors that bind with estrogen and progesterone. When bound to the receptors, the hormones interact with appropriate genes, helping to promote breast development during puberty and prepare breasts during pregnancy. Most breast cancer cells also have these hormone receptors.

If a pathologist detects estrogen receptors (ER) or progesterone receptors (PR) on the cancer cells, he or she will report the tumor cells as ER positive or PR positive, respectively, or both. If no ER or PR receptors are detected, the tumor is reported as ER negative or PR negative, respectively, or both.

In addition to determining if a cancer has estrogen or progesterone receptors, the pathologist will report on the percentage of tumor cells with receptors and the degree of receptor positivity. This information is helpful to doctors in determining which cancer medications may be most effective.

The good news about being ER positive or PR positive is that you may benefit from hormone therapy, which consists of medications designed to interfere with the hormone stimulation of these cancers. Hormone receptor positive cancers typically grow more slowly than do hormone receptor negative cancers.

HER2 status

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) is a protein receptor that’s produced by the HER2 gene. Normally, substances that attach to this receptor stimulate cell division. When too many of these receptors are present, they can cause increased cell growth. About 20 to 25 percent of breast cancers have an excess of the HER2 protein.

There are two ways to test for HER2 receptors: One is by a technique called immunohistochemistry (protein overexpression) and the other is by a method called fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), also known as gene amplification.

Knowing that your cancer cells contain too much HER2 can be important information that can help determine the treatment you receive. The drug trastuzumab (Herceptin), for example, is a specific antibody that binds to HER2 shutting it down and, thereby, reducing the growth rate of the cancer (see Chapters 3 and 11).

Once a doctor knows that cancer is present, he or she wants to know if the cancer is confined to the breast or if it has spread to other areas. This knowledge is obtained through what’s called staging. Staging is another aspect of the diagnostic process that’s essential to determining the best form of treatment. It’s also a very significant factor in predicting your prognosis.

Staging tests

Several additional tests may be needed as your doctor determines the stage of your cancer. These include blood tests, a chest X-ray, bone scan, magnetic resonance image (MRI), computerized tomography (CT) scan and positron emission tomography (PET) scan. It’s important to note, though, that most women don’t need all of these tests. This is partly because the tests have limited usefulness and partly because the chances that the cancer has spread beyond the breast and lymph nodes are low.

Blood tests

A complete blood count (CBC) can help your doctor assess your general health. A CBC measures:

A blood chemistry test measures the level of substances that indicate whether your organs, such as your kidneys and liver, are functioning correctly.

Abnormal levels of certain substances in your blood, called tumor markers, might suggest the presence of cancer. But unless other evidence suggests your cancer has spread to distant parts of your body — which occurs in only 5 to 10 percent of women when they’re initially diagnosed — tests for these markers generally aren’t used because they don’t provide much useful information at this point. In addition, no one tumor marker is specific for breast cancer.

Chest X-ray

Your doctor may recommend a chest X-ray to check for any evidence that the cancer has spread to your lungs. If your tumor is very small and the cancer cells haven’t spread to your lymph nodes, a chest X-ray may not be necessary.

Bone scan

A bone scan is used to check for spread of the cancer to your bones. The test usually isn’t done unless other evidence indicates possible spread, such as pain in your bones or abnormal blood tests.

During the test, you receive an injection containing a tiny amount of a radioactive tracer. The tracer is drawn to cells involved in bone remodeling. Throughout a person’s lifetime, bone tissue is continuously removed and replaced by new bone tissue, a process called remodeling. When cancer cells spread to bone, remodeling typically increases. A special camera scans your body and records whether the tracer has accumulated in certain areas (hot spots). A hot spot may indicate that cancer has spread to your bones, but it could also indicate infection or arthritis, another cause of increased bone remodeling.

Computerized tomography scan

Computerized tomography (CT) is an X-ray technique that produces more-detailed images of your internal organs than do conventional X-ray studies.

The procedure involves an X-ray tube that rotates around your body and a large computer to create cross-sectional, 2-D images (slices) of the inside of your body. When these images are combined, a doctor may be able to see tumors, measure them and later biopsy them if necessary. This test is generally only used if your doctor suspects the cancer has spread.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Like computerized tomography, a magnetic resonance image (MRI) also views the inside of your body in cross-sectional slices, but it uses an extremely strong magnet instead of X-rays. The magnet manipulates water molecules in your body so that they tumble, which produces a faint signal. A sensitive receiver — similar to a radio antenna — picks up those signals. A computer used to generate the pictures manipulates the resulting signal.

Depending on their chemical makeup, different tissues produce stronger or weaker signals. This allows a doctor to differentiate a tumor from normal tissue. In some cases, MRI can be a more sensitive test than can a CT scan. Typically, though, this test isn’t necessary to stage breast cancer.

Positron emission tomography scan

Positron emission tomography (PET) is different from an MRI or CT scan in that it records tissue activity rather than tissue structure. As opposed to normal cells, cancer cells often exhibit increased metabolic activity. During a PET scan, you will receive a small amount of a radioactive tracer — typically a form of blood sugar (glucose) — into your body. Most tissues in your body absorb some of this tracer, but tissues that are using more energy — exhibiting increased metabolic activity — absorb greater amounts. Tumors are usually more metabolically active and tend to absorb more of the sugar tracer, which allows the tumors to light up on the scan.

PET scans are typically performed with CT scans to help localize the abnormal areas. Your doctor may recommend a PET scan if he or she suspects the cancer has spread but is uncertain of the location to which it has spread.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Most women with a new diagnosis of breast cancer don’t need to undergo all the diagnostic tests available. The following examinations and tests — in addition to a biopsy of the tumor or suspicious area — are often all that’s necessary to determine the stage of the cancer:

Staging classification

After your surgery your doctor may order additional tests. Once the surgery is complete and the results of these tests are known, your doctor will have the information needed to let you know the stage or your cancer.

Ideally, staging is done after examination of tissue specimens (pathologic material) obtained during surgery. This is called pathologic staging. Staging can be attempted before pathologic examination. This method, termed clinical staging, is less accurate.

The most commonly used method of doing this is the TNM staging system created by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. It addresses three key issues:

Numbers are assigned to each of these categories, indicating the degree to which the tumor has grown or spread. T receives a number from 0 to 4, indicating the size of the tumor and if it has spread to the skin or chest wall. N receives a number from 0 to 3, indicating the degree of spread to the lymph nodes and how many lymph nodes are involved. M is rated either 0 or 1, indicating no spread or spread, respectively, to distant parts of the body.

A higher number indicates a larger tumor or more advanced spread of the cancer. More detailed notations also may be assigned to certain categories, such as to indicate whether the cancer is in situ (vs. invasive), or a lowercase letter to signify a subcategory. For example, a T1, N0, M0 classification means that the tumor is less than 20 millimeters (mm), it hasn’t spread to the lymph nodes, and it hasn’t metastasized. These classifications may be modified after surgery when the pathologic data are complete.

Once the TNM classification is made, your doctor can determine the stage of your cancer, which usually is labeled as a Roman numeral. A lower number indicates an early stage, and a higher number means a more advanced, serious cancer. The T1, N0, M0 tumor described above would be a stage I tumor.

Stages 0 to IV

Breast cancer staging is complicated and constantly changing as doctors learn more about breast cancer, its spread and prognosis. The chart on the opposite page lists the latest stage groupings for breast cancer. Your doctor can identify for you which designation describes your cancer. Following is some general information about the stages of breast cancer.

Stage 0

This is very early (in situ) breast cancer that hasn’t spread within the breast or to other parts of the body.

Stage I

Stage IA cancer refers to breast cancer that’s 20 mm or less in size — smaller than an inch — with no lymph node involvement. Lymph nodes containing cells that look like they came from the breast but are less than 0.2 mm are considered negative lymph nodes because there’s no good evidence these are established cancers. This is a stage IB cancer.

Stage II

Stage II is subdivided into IIA and IIB. Stage II cancer is more extensive than stage I, but not as extensive as stage III. A tumor is stage IIA if it is 20.1 to 50 mm in size, has spread to up to three lymph nodes under the arm or to lymph nodes under the sternum, or both. A tumor greater than 50 mm in size with no spread to the lymph nodes is stage IIB.

Stage III

Stage III breast cancers are subdivided into three classifications: IIIA, IIIB and IIIC. Stage III cancers include a number of criteria that make this a broad category. Stage III cancers are sometimes referred to as local-regionally advanced cancers. One of the main criteria with stage III cancers is there’s no evidence the cancer has spread (metastasized) to distant sites.

Some examples of stage III cancers are as follows:

Stage IV

In stage IV, the cancer has spread beyond the breast and adjacent lymph nodes to distant parts of the body, such as the lungs, liver, bones or brain.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Primary tumor status

T0: No evidence of primary tumor

Tis: Carcinoma in situ

T1: ≤ 20 millimeter (mm) of invasive cancer

T2: 20.1-50 mm of invasive cancer

T3: 50 mm of invasive cancer

T4: Direct extension to the chest wall, or skin ulceration, or skin nodules, or inflammatory breast cancer

Regional lymph node/pathologic status

N0: None involved, or node with < 0.2 mm area of tumor cells

N1: 1-3 involved axillary nodes, or microscopically involved internal mammary node detected by sentinel node biopsy procedure

N2: 4-9 involved axillary nodes or clinically apparent internal mammary nodes

N3: ≥ 10 involved axillary nodes, or infraclavicular node, or supraclavicular node, or axillary nodes and internal mammary nodes

Metastasis

M0: No distant metastasis

M1: Distant metastasis

Based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer’s AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th edition, 2010; published by Springer Science and Business Media LLC. Used with permission.

≈≈≈≈≈≈≈

Estimating survival

Based on statistics assembled from women diagnosed with breast cancer in the past, scientists are able to estimate how many women with varying tumor features might survive for at least five years after a breast cancer diagnosis. This is commonly known as the five-year survival rate. Specifically, it refers to the percentage of women who are still alive five years after their cancers were diagnosed.

This doesn’t mean that survivors live for only five years after being diagnosed with cancer. In fact, most cancer survivors live much longer. It also doesn’t mean that a woman still living five years after her initial treatment is cured. Of all women who experience a breast cancer recurrence, less than half of the time it’s within the first five years. More often, it comes later than five years.

Clearly, advances in early detection and treatment have increased survival time. Today, women diagnosed with breast cancer are living longer than did women diagnosed 20 or 30 years ago.

But remember that statistics don’t tell the whole story. They only serve to give a general picture and a standard format for doctors to discuss prognosis. Every woman’s situation is unique. If you have questions about your own prognosis, discuss them with your doctor or your cancer care team. These individuals can help you find out how these statistics relate, or don’t relate, to you.

More information on breast cancer prognosis is provided in later chapters.

| Breast cancer stage grouping |

|||

| Stage | T | N | M |

| Stage 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| Stage IA | T1 | N0 | M0 |

| Stage IB | T0 T1 |

N1mi N1mi |

M0 M0 |

| Stage IIA | T0 T1 T2 |

N1 N1 N0 |

M0 M0 M0 |

| Stage IIB | T2 T3 |

N1 N0 |

M0 M0 |

| Stage IIIA | T0 T1 T2 T3 T3 |

N2 N2 N2 N1 N2 |

M0 M0 M0 M0 M0 |

| Stage IIIB | T4 T4 T4 |

N0 N1 N2 |

M0 M0 M0 |

| Stage IIIC | Any T | N3 | M0 |

| Stage IV | Any T | Any N | M1 |

From the American Joint Committee on Cancer’s AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th edition, 2010; published by Springer Science and Business Media LLC. Used with permission.

Tis: Indicates noninvasive (in situ) cancer

mi: Indicates the cancer is <0.2 mm and can only be seen by a microscope

T 0-4: Refers to tumor size and spread

N 0-3: Indicates degree of spread to the lymph nodes

M 0-1: Indicates spread to distant parts of the body