INTRODUCTION

The Audubon Ethic

LIKE MANY ANOTHER GENIUS, John James Audubon was “the right man in the right place at the right time” He came to America with a fresh eye when it was still possible to document some of our unspoiled wilderness. He was also, during his lifetime, witness to the rapid changes that were taking place. Audubon’s real contribution was not the conservation ethic but awareness. That in itself is enough; awareness inevitably leads to concern.

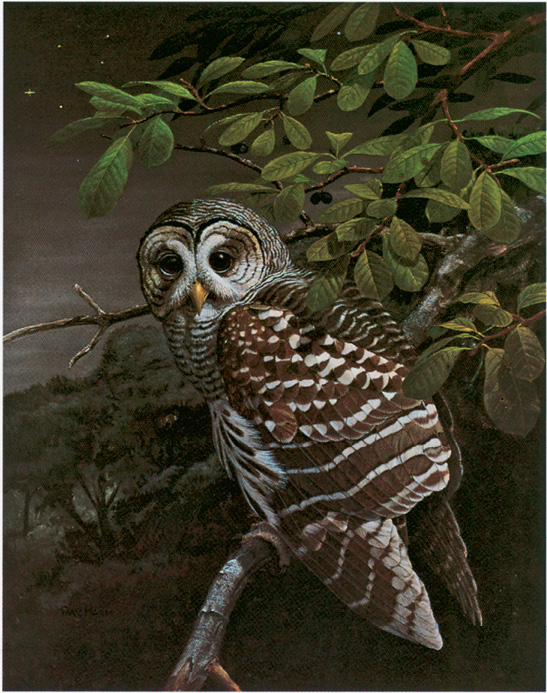

Audubon’s frequent references to the palatability of birds and their availability in the market make us realize how far we have come in bird protection, if not in our epicurean tastes. He wrote that “the Barred Owl was very often exposed for sale in the New Orleans market; the Creoles make Gumbo of it, and pronounce the flesh palatable.” Not only does he speak with a gourmet’s authority about the edibility of owls, loons, cormorants, and crows, but also the gustatory delights of juncos, white-throated sparrows, and robins.

It may seem paradoxical that this prototype of the woodsman-huntsman should have become the father figure of the conservation movement in North America. Like most other pioneer ornithologists, he was literally “in blood up to his elbows.” He seemed obsessed with shooting; far more birds fell to his gun than he needed for drawing or research or for food. He once said that it was not a really good day unless he shot a hundred birds. But in his later writings, when recounting old shooting forays, there is a note of regret, as though his conscience were bothering him about the excesses of his trigger-happy days. He deplored the slaughter, especially when perpetrated by others—a double standard, if you will. But only once did he ask forgiveness for his acts. After describing the carnage that took place in the Florida Keys when he and his party landed in a colony of cormorants, “committing frightful havoc among them,” he wrote: “You must try to excuse these murders, which in truth might not have been so numerous had I not thought of you [the reader] quite as often while on the Florida Keys, with the burning sun over my head and my body oozing at every pore, as I do now while peaceably scratching my paper with an iron pen, in one of the comfortable and quite cool houses of Old Scotland.”

Repeatedly in his writings he reveals this dual nature, or inner conflict. After finding the nest of a pair of least sandpipers he wrote, “I was truly sorry to rob them of their eggs, although impelled to do so by the love of science, which offers a convenient excuse for even worse acts.” Again, when he first met the arctic tern in the Magdalene Islands: “As I admired its easy and graceful motions, I felt agitated with a desire to possess it. Our guns were accordingly charged with mustard-seed shot, and one after another you might have seen the gentle birds come whirling down upon the waters. . . . Alas, poor things! How well do I remember the pain it gave me, to be thus obliged to pass and execute sentence upon them. At that very moment I thought of those long past times when individuals of my own species were similarly treated; but I excused myself with plea of necessity, as I recharged my double gun.” Another example of Audubon’s compulsion to shoot.

In light of his record it would seem inappropriate that one of the foremost conservation organizations in the United States should adopt Audubon’s name, but not so. He was ahead of his time. Like so many thoughtful sportsmen since, he eventually developed a conservation conscience. In an era when there were no game laws, no national parks or refuges, when there was no environmental ethic, when vulnerable nature gave way to human pressures and often sheer stupidity, he was a witness who sounded the alarm. He became more and more concerned during his later travels when, with the perspective of his years, he could see the trend. He noticed that prairie chickens, wild turkeys, Carolina parakeets, and many other birds were no longer as numerous as he once knew them. He wrote vividly and passionately about what he saw. He pondered the future, and some of the passages in his writing were prophetic.

Audubon could not have known that because of his artistry and his writing his name would become a household word, synonymous with birds, wildlife, and conservation. The National Audubon Society, formerly known as the National Association of Audubon Societies, was launched in 1905, when no one spoke of “ecology” or “environment.” It was primarily a bird organization at first. Over the years the Society has gone through a philosophical metamorphosis. Bird-watching was the precursor of ecological awareness, and “Audubon” has become a symbol of the environmental movement.

John James Audubon received high honors during the two decades prior to his death in 1851, but his greatest fame came in the century that followed. He had sparked a latent nationwide interest in the natural world, especially its birds, and his name became enshrined in hundreds of streets, towns, and parks across the land. Even a mountain peak in the Rockies is named in his honor. In the section of New York City where he lived there is an Audubon Avenue, an Audubon Theatre, and, now translated into digits, an Audubon telephone exchange. There was even a group that called themselves the “Audubon Artists,” although they did not draw birds. But the greatest monument to his name is the National Audubon Society, which, unlike the “Audubon gun clubs” before the turn of the century, reflects the other side of John James Audubon, the passionate concern for the survival of wildlife and wild America that he developed as he grew older.

The Audubon Saga

THE SAGA OF AUDUBON has been told many times, with variations. It is not exactly a Horatio Alger tale of rags to riches, because the fledging Audubon, born out of wedlock, was given a young gentleman’s tutoring and was all but spoiled by an indulgent stepmother.

Jean Jacques Fougère Audubon was born in 1785 on the island of Santo Domingo, now Haiti, in the West Indies. He was the son of an enterprising French sea captain who, after reverses in Les Cayes, where he owned property, returned to France with the boy. His mother was a young lady, Mademoiselle Rabin, originally from Nantes, who died before the captain returned to his home and legal wife in France. How he explained his transgressions to Madame Audubon is not known, but she took the four-year-old boy to her heart as her own as she did his sister, also born out of wedlock.

Perhaps to enable his son to escape conscription in Napoleon’s army, or perhaps to help him avoid the stigma of illegitimacy, Captain Audubon sent Jean Jacques at the age of eighteen to Mill Grove near Philadelphia where he owned property. The birds of America fascinated young Audubon, and drawing them became an obsession from which he never freed himself.

Audubon performed an experiment at Mill Grove that marked a “first” in the history of ornithology. He was fascinated by the phoebes that lived along the creek near his home. By placing silver threads about the legs of a brood of young phoebes to see whether they would return the following year, he became the first bird bander (or “ringer,” to use the British term).

At Mill Grove Audubon married Lucy Bakewell, the daughter of a neighbor. Shortly thereafter the young couple moved westward to Louisville, Kentucky, where Jean Jacques’s father had set him up in business. But business was not in his blood, or so it seemed. It must be admitted that times were uncertain and investment risky on the frontier in those days. Moving farther west to the Mississippi and then down to New Orleans, Audubon met successive reverses until he was almost reduced to penury. Some called him impractical.

In reviewing this difficult period Audubon wrote, “Birds were then as now. . . . I drew, I looked on nature only; my days were happy beyond human conception.” He had conceived a grandiose plan of painting all the birds of North America—at least all then known—and at no time did he lose sight of this goal. He may have harbored the idea of eventual publication from the start, but it seems that the unheralded visit by pioneer ornithologist Alexander Wilson stirred his competitive spirit to action.

Audubon was often away from his family for months, exploring the wilderness, painting, and pursuing his dream. His devoted Lucy, who had borne him two sons, Victor and John, kept home and hearth together by teaching. He himself eked out a living as an itinerant portrait painter and as a dancing and fencing instructor.

As his portfolio bulged he began to look for a patron or a publisher, but he could find none in New York or Philadelphia. No one would risk the capital in those difficult days. Audubon decided that there might be a better chance of success in England, so with Lucy’s savings as a teacher and some money he had managed to acquire by painting portraits of well-to-do people, he set sail in 1826.

Abroad he was acclaimed immediately. Although he had been a nobody on his home turf, the rough, colorful man from the American frontier was a sensation abroad. He fascinated the genteel patrons of the art salons in London, Edinburgh, and Paris. Madison Avenue would have admired his public relations techniques. Long ahead of his time in the art of showmanship, he played his part well. To fit the image of the American woodsman, he wore buckskin and allowed his hair to grow long over his shoulders. The former bankrupt businessman became a supersalesman, traveling from city to city to secure subscriptions. Meanwhile, as a sort of production manager, he monitored with infinite care the work of the engravers and a corps of colorists. He was not only artist, author, and scientist but also publisher, business manager, treasurer, and bill collector.

How could he have been “irresponsible” or “impractical” if he could do all this?

William Lizars of Edinburgh agreed to engrave and publish his work, but when only ten plates had been finished the colorists went on strike and Audubon was forced to find another engraver. This was Robert Havell, Jr., of London. Audubon was fortunate to be in the hands of such a skilled craftsman and artist. Havell’s accomplishment in etching the copper plates was as much a tour de force as the original paintings. It is instructive to compare the watercolors that hang in the galleries of the New-York Historical Society to the Havell prints with which most of us are familiar.

In his 435 colorplates, Audubon depicted the birds exactly the size they were in life. Even the oversize format, 29½ by 39½ inches (known as “double-elephant folio”), the largest ever attempted up to then in the history of book publishing, was insufficient to accommodate the largest birds comfortably. Tall birds, such as the flamingo and the great blue heron, were fitted in by drooping their long necks toward their feet. On the other hand, tiny birds, such as kinglets and hummingbirds, are all but lost on the page.

Among the last few plates in the Elephant Folio and the 65 additional ones in the smaller octavo edition, Audubon included a number of birds from the western part of the country. These were his least successful efforts, probably because he had not seen these species in life.

Audubon as an Artist

AUDUBON IMPLIED THAT AS A YOUTH he had studied under the French master Jacques Louis David, and in doing so laid the foundation of his ability to draw. However, recent research has disputed this. Perhaps it was a good thing that his art was truly his own; like many another innovative genius he was not a clone of his professor. Nor were his paintings like the dull, documentary drawings of Alexander Wilson and his other contemporaries.

The thing that separated Audubon from his predecessors was that he was the first to give his birds the simulation of life. The others portrayed them stiffly and archaically as though they were on museum pedestals. To invest his birds with vitality and movement, Audubon worked from freshly killed specimens, wiring them into lifelike positions. In his youth he had tried hundreds of outline sketches but found it difficult to finish them. He fashioned a wooden model, “a tolerable-looking Dodo. . . . I gave it a kick, broke it to atoms, walked off, and thought again.” It was then that he conceived the procedure he was to follow for many years. He wrote: “One morning I leapt out of bed . . . went to the river, took a bath and returning to town inquired for wire of different sizes, bought some and was soon again at Mill Grove. I shot the first Kingfisher I met, pierced the body with wire, fixed it to the board, another wire held the head, smaller ones fixed the feet. . . . There stood before me the real Kingfisher. I outlined the bird, colored it. This was my first drawing actually from nature.”

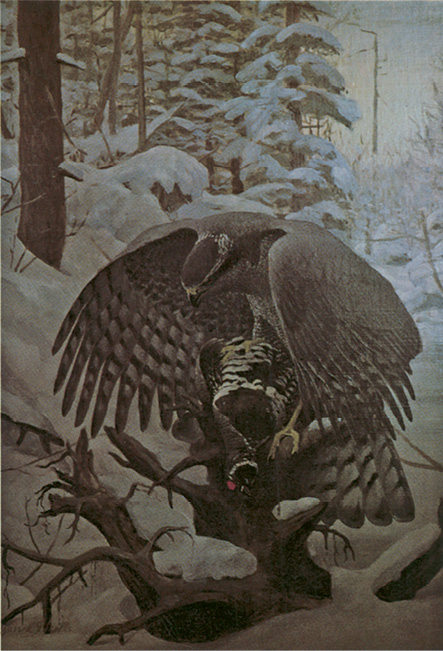

It has been remarked that a Fuertes bird in repose has more the essence of the living bird than an Audubon bird vividly animated. This is understandable when one keeps in mind that Audubon wired up his specimens, and they sometimes looked it. In most cases this method worked fairly well, but the wild turkey cock, wired with its head looking over its back so as to fit the sheet, is almost a caricature. So are Audubon’s barred owl with the grinning squirrel, and his two red-tailed hawks quarreling in mid-air for possession of a rabbit. His golden eagle frozen in flight with a hare, his two barn owls at night, and his squabbling caracaras are all too contrived. His two blue-winged teals look as though they were thrown through the air like footballs. Inasmuch as Audubon did not know some of the pelagic birds—the fulmar, greater shearwater, and tropic-bird—on their nesting ground, he showed them standing on their toes rather than resting on their bellies with their tarsi flat on the ground.

We can, if we choose, be critical of these errors, but the wildlife artist of today is able to step on the shoulders of those who have gone before. In fairness, Audubon made the great leap forward at a time when most birds were drawn as though “stuffed” and fastened to wooden perches in museum cases. He took birds out of the glass case for all time and gave them a semblance of life. His paintings have a dramatic impact seldom equaled by those of his successors.

Fuertes, in a remarkable letter to his young protégé George Miksch Sutton, extolled Audubon’s strengths and defended his shortcomings, unaware that his “training under David” was apparently a myth:

Say what you will of Audubon, he was the first and only man whose bird drawings showed the faintest hint of anatomical study, or that the fresh bird was in hand when the work was done, and is so immeasurably ahead of anything, up to his time or since, until the modern idea of drawing endlessly from life began to bear fruit, that its strength deserves all praise and honor, and its many weaknesses condonement, as they were the fruit of his training; stilted, tight, and unimaginative old [Jacques Louis] David sticks out in the stiff landscape, the hard outline, and the dull, lifeless shading, while the overpowering virility of Audubon is shown in the snappy, instantaneous attitudes, and dashing motion of his subjects. While there’s much to criticize there is also much to learn, and much to admire, in studying the monumental classic that he left behind him. He made many errors, but he also left a living record that has been of inestimable value and stimulus to students, and made an everlasting mark in American ornithology. It is indeed hard to imagine what the science would be like in this country—and what the state of our bird world—had he not lived and wrought, and become a demigod to the ardent youth of the land.

(From Bird Study, an Autobiography, by George Miksch Sutton, Austin: University of Texas Press, 1980.)

Sutton, who himself later became a distinguished bird artist, wrote: “It was Audubon’s instinctive urge to dramatize which led him to represent so many of his birds in violent action. As several admirers of the great artist have pointed out, he was so surfeited with the conventional and lifeless poses used by the bird artists before him that he swung away from the traditional in a sort of furious huff. . . . This was Audubon, lover of beauty, lover of the dramatic, avowed opponent of the prosy.” If his art had been less startling and dramatic, it probably would not have survived and we would have heard little about Audubon, for relatively few people read his extensive writings.

In the beginning, Audubon vowed he would paint only from fresh specimens of birds he had collected after observing them in life. Halfway through his project, this resolve broke down. While he was involved in reproducing his paintings in London, many new species were being discovered in the American West. Since he had no immediate hope of reaching the Rockies or the Pacific himself, he was forced to draw them from specimens furnished by Dr. Thomas Nuttall, a New England botanist, and Dr. John Kirk Townsend, an experienced ornithologist, who set out together in 1834 on an exploratory journey to the mouth of the Columbia River. Captain Ross of the Royal Navy furnished additional seabirds that had been taken during his explorations in the Arctic. Other specimens were borrowed from the British Museum. Few of Audubon’s later drawings were as inspired as his earlier efforts, because he had never seen these species in life. Many single drawings showed three, four, or five species.

Apprentices

MUCH HAS BEEN SAID of the fine sense of pattern and composition in some of Audubon’s plates. However, it should be pointed out that, like many another artist of an earlier day, he had apprentices. Many of the backgrounds, leaves, flowers, and other botanical accessories were painted by others, but the birds in almost every instance were the work of the master himself. Some compositions remind us of Chinese prints, but we are quite sure Audubon’s work was in no way imitative.

The elaborate composition of black-billed cuckoos (plate 233) was probably a cooperative effort. Although Audubon did not give him credit, it is quite certain that Joseph Mason painted the magnolia blossoms and leaves. Audubon wrote to Lucy, “He now draws flowers better than any man probably in America.”

Joseph Mason, who as a remarkable boy of thirteen had been one of Audubon’s pupils in Cincinnati when he was giving art lessons to raise funds, showed such promise as a botanical artist that Audubon took him on his 1820 trip down the Mississippi. Mason was his assistant for about two years, and most of the leaves and flowers in those plates painted in Louisiana during 1821 and 1822 are his work. He was incredibly skillful for a youngster of that age. At least 57 backgrounds are credited to this young genius. He seems to have disappeared into limbo after leaving Audubon’s employ, but he is immortalized in Audubon’s bird prints.

During the next several years Audubon may have painted his own backgrounds, but in 1829 he met George Lehman, who was to assist him for the next four years, accompanying him on his trips to the shore and to Florida. Although Lehman was an experienced landscape painter, his leaves and other accessories are a bit more labored and cluttered than those of Mason, who had an innate sense of abstraction and pattern. Lehman’s landscapes give a different look to many of the paintings that were made during that productive period; they were more environmental, but less decorative. Lehman is known to have painted the backgrounds for about forty plates, but he probably did more. He even painted an occasional bird; the lesser yellowlegs in plate 163 is credited to him.

Time was important once the great work was fully under way. Flowers and leaves took as long to paint as the birds, so Audubon was pleased to enlist a third helper, whom he met in Charleston, a maiden lady by the name of Maria Martin, who later became Reverend John Bachman’s second wife. She had a well-tended garden, painted flowers and butterflies quite well, and is credited with drawing the flowers and leaves in about twenty of the paintings. They are not the equal of Joseph Mason’s work; her twigs and stems lack his structural strength. The butterflies and moths that appear in six of the plates are presumably hers.

Audubon’s two sons were also drawn into the project. His younger son, John Woodhouse Audubon, who became an accomplished artist, helped with some of the work while in London and actually drew a few of the birds, notably the American bitterns in plate 40. The elder son, Victor Gifford Audubon, painted some of the backgrounds in the later western subjects, but they are more stilted than those of Lehman. It is believed that even Lucy Audubon may have painted at least one bird, the swamp sparrow (plate 426). Add to these efforts the skill and expedient innovation of Robert Havell, Jr., the engraver, who improvised branches and twigs where needed, or even full backgrounds where none existed, and we have, in effect, paintings by committee.

Twelve years after Audubon’s death in 1851, his widow Lucy sold the original paintings to the New-York Historical Society, where they can be seen today. Reproductions of Audubon’s work invariably were made from the Havell prints until 1966, when the American Heritage Publishing Company of New York and the Houghton Mifflin Company of Boston went directly to the original watercolors. It is instructive to compare the originals with the prints, because Havell was in a sense no less a genius than Audubon and left his own artistic stamp on the plates, sometimes even improving them. Some are literally scissors-and-paste jobs. A pastel made in 1820 might be copied in watercolor ten or twelve years later or simply cut out and pasted onto another drawing. Audubon did not hesitate to mix mediums. Pencil, ink, pastel, watercolor, and even oil were combined in some compositions.

America was reawakened to the splendor of Audubon’s work in 1937, when the Macmillan Company of New York reproduced, in smaller size, 435 prints from the Elephant Folio and an additional 65 prints from the octavo edition. Although the reproductions left much to be desired, they were a breakthrough. Audubon’s prints have been reproduced a number of times since in various forms, and they reached their greatest audience when they graced the calendars of the Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company of Milwaukee. Over a period of twenty years more than ten million well-reproduced and framable Audubon prints were distributed in these calendars.

The Double Elephant Folio

AUDUBON’S REPUTATION SKYROCKETED upon publication of his great work. Baron Cuvier, the French naturalist, rated it the “most magnificent monument which has ever been raised to ornithology.” But every genius has his or her critics. One subscriber discontinued her subscription after she received the first lot of prints, numbers 1 to 9. She pronounced them so very bad that she could not think of giving “house room” to any more such “trash.”

Not counting his own living costs and those of his family, Audubon spent $115,640 to complete his project. Approximately 200 sets of the Double Elephant Folio were bound and distributed. They were priced at $1,000 each. It was thought that more than half these sets had been broken up by 1970 and sold by dealers as individual prints. However, through the extraordinary investigation of Waldeman H. Fries, we find this was far from true. When he documented the sets in his scholarly work The Double Elephant Folio: The Story of Audubon’s Birds of America (Chicago: American Library Association, 1973), about 134 complete sets survived. Of these, 94 were in the United States, 17 in England, and the remainder in twelve other countries. It attests to the fortitude of Fries (and his wife) that he was able to examine all but six of these sets. In addition, 14 incomplete sets survived, 28 sets were broken up, 11 were destroyed by fire or war, and 14 had disappeared. It was rumored that one unanticipated spinoff of the Fries book was that thieves, finding the locations of existing sets pinpointed, made off with three of them. All three were eventually recovered.

Nearly a century elapsed before the original investment of $1,000 per set really began to pay off in the collector’s market, in direct proportion to the vastly increased interest in birds that had begun to accelerate with the publication of modern field guides. In the 1920s, a collector or speculator could have acquired a set of Audubon at auction for about $2,500. By the mid or late thirties it would have been closer to $12,000 or $14,000; by the mid-forties, $18,000; in 1960, $60,000 was paid for a set; and in 1969, $216,000. In 1977 a set was sold at auction for $400,000, and the price continued to climb. On June 23, 1989, at an auction at Sotheby’s, the total realized from a set that had been broken up was $3,960,000!

Individual prints that could have been purchased at Goodspeeds in Boston for $7.50 to $25.00 in 1905 went for $500 to $4,000 or more in the late 1970s. The wild turkey—“The Great American Cock”—rose from $200 in 1905 to $20,000 in 1980 for one in mint condition. At an auction at Sotheby’s in 1989 a print of the mallard that fetched $45,100 was bettered by four prints: the trumpeter swan ($49,500), the white pelican ($58,300), the great blue heron ($66,000), and the flamingo ($66,550), much more than presale estimates. Whether this says more about Audubon or about the inflated art market is debatable.

It is plain that not all of Audubon’s prints are of equal appeal or merit, nor do they command equal prices. The very lowest price for any print would be not much less than $700. Waterfowl bring higher prices than songbirds. Whereas a duck or a heron might cost thousands, a wren might be had for less than $700. Similarly, in Audubon’s Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, published later, a deer would bring more than $1,000, but a mole or a shrew might go for as little as $300.*

The excellent little Handbook of Audubon Prints by Taylor Clark and Lois Elmer Bannon (Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing Company, 1980) gives in concise form not only the prices (at that time) of Havell and Bien prints in good condition but also the locality where each bird was painted, the date, and, when known, the artist who worked on the background.

* As of 2012, most Audubon prints sell for a minimum of $2,500. The relationship of value between waterfowl and songbirds still stands today, though a wren might sell for $1,000 at the lowest. A deer would still be worth more than a mole or shrew, the deer going for about $1,500 and the latter two for as little as $350 each. —Ed.

The Ornithological Biography

ONCE THE ENGRAVING and coloring of the first hundred of his bird portraits was in progress, Audubon began work on a text to accompany them. It had been British law since 1709 that any published work with letterpress accompanying the illustrations was a proper book. Therefore, if Audubon were to combine text and illustrations within the same covers, he would have to deposit a copy of the work in each of nine libraries in the United Kingdom. To get around this ruling, his Ornithological Biography, or an Account of the Habits of the Birds of the United States was printed separately in five volumes. The texts were in the order in which the birds appeared in the colorplates.

Fully aware of his own shortcomings as a man of letters, Audubon had the help of his wife in spelling, punctuation, and grammatical structure. He then asked William Swainson if he would take on the role of general editor. Swainson requested a fee of 250 pounds sterling per volume. This was plainly more than Audubon could afford, so he finally made an arrangement with William MacGillivray, of the University of Edinburgh, who agreed to do the job for 50 to 60 pounds per volume. MacGillivray not only edited Audubon’s text but contributed lengthy descriptions of the anatomy of many species. These were usually accompanied by his own line drawings. Audubon himself became a fair anatomist through this working association with a very devoted friend. MacGillivray suggested the inclusion of a series of essays, “Delineations of American Scenery and Character.” The argument for interspersing an essay here and there was to keep the reader from being bored by a steady diet of birds.

Although Audubon’s immortality rests largely on his work as an artist, he was no less important as an ornithologist. The wealth of observation detailed in the 3500 pages of his Ornithological Biography remains the guide for comparing the status of birds then and now. Also important as a historical record are his “delineations” of places, people, and customs.

Judging by his descriptions of bird voices, Audubon had a very poor ear, particularly when describing some of the high-pitched warblers, which he flatly stated had no song. Obviously, he had been banging away with his fowling piece so much since his youth that his eardrums were as insensitive as those of some modern rock musicians.

After three intensely active years in England, Scotland, and France, Audubon returned to America in 1829 to paint additional birds, to try for more subscriptions, and to travel extensively and fill in the gaps. Eventually his journeys took him from the Gulf Coast and the Florida Keys to Labrador and westward to the foothills of the Rockies. It took twelve years to complete the publication of the plates and their accompanying texts in the Ornithological Biography.

The Octavo Edition

EVEN BEFORE the Elephant Folio and the Ornithological Biography were completed, Audubon began to plan an octavo version that he hoped would reach an audience far larger than the few libraries and very rich people fortunate enough to own the big work. The octavo Birds of America appeared in seven volumes from 1840 to 1844. It met with immediate success, and the first edition of 1200 copies was quickly sold. This was followed by seven more editions (not counting recent reprints).

Because several years had elapsed since the Ornithological Biography was written, many new facts about birds were known, and accordingly changes were made in nomenclature and in the text. Stability in bird names had not yet been achieved, so Audubon included a synonymy that brought things up to date. The plates, this time bound with the text, were miniaturized by black and white lithography and then hand-tinted by a corps of as many as 70 colorists. In the octavo, related birds were grouped together, not presented in the haphazard order in which they appeared in the Elephant Folio. Sixty-five new plates were added, bringing the total to 500. A few represented newly discovered birds from the West. Other plates were individual repeats of species that had been lumped in some of the composite plates. The “Delineations of American Scenery and Character” were omitted on the advice of his friend the Reverend Bachman, who said it was all “humbug.”

The Quadrupeds

AS HE ADVANCED IN YEARS, Audubon had changed from the “impractical dreamer” to a “workaholic” in every sense of the word. A driven man, he had scarcely brought to completion his herculean task on the Elephant Folio and gotten started on his octavo edition of Birds of America before he laid plans for his two-volume Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, in collaboration with his two sons and the Reverend Bachman of Charleston, who had become a devoted friend. Toward this end Audubon tried to get government support in 1842 for a research expedition to the Rockies, but without success. The following year, however, the American Fur Company offered him transportation up the Missouri River as far as the Yellowstone River. This enabled him to draw many of the western mammals in the field. But about three years later, before the plates were half completed, his eyes and his mind began to fail, possibly from a stroke, and he was forced to lay down his brushes forever. On January 27, 1851, Jean Jacques Fougère Audubon died, “as gently as a child composing himself for his beautiful sleep.” He had not reached his sixty-seventh year. Meanwhile, the remaining mammals were painted, mostly in oil, by his son John, while his son Victor filled in most of the backgrounds. Reverend Bachman finished the manuscript and brought the Quadrupeds to completion in 1852. It was truly a cooperative family effort, as Bachman’s two daughters had married Audubon’s sons.

Before Audubon

ALTHOUGH JOHN JAMES AUDUBON is the best known of America’s ornithological pioneers, he was by no means the first. Alexander Wilson, the transplanted Scot, is usually accorded the distinction of being the father of American ornithology, having published his trailblazing American Ornithology about twenty years before Audubon produced his Birds of America and its accompanying Ornithological Biography.

Alexander Wilson Herons and Bitterns c. 1814

Actually, Mark Catesby, an Englishman, preceded them both by a century. His two-volume Natural History of the Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, published between 1731 and 1743, depicted one hundred thirteen birds and established him as the first ornithologist working on American birds. If, as Dr. Elsa Allen of Cornell suggested in her History of American Ornithology, Catesby is the founder of American ornithology, and if Wilson is its father, then Audubon is its patron saint.

Catesby’s drawings are typical of most of those being done in Europe at that time. They are meticulously executed, but archaic and crude with little semblance of sound structural drawing. They do not for a moment give us the impression of living birds. Their antique captions give these quaint drawings a historical interest, but little more.

Mark Catesby The Blew-Bird 1720s

Alexander Wilson was a poet and a rebel who was once jailed for writing a scathing poem about a local mill owner in his home town of Paisley. He had also written two or three slender volumes of verse that were more favorably received, including a poem that Robert Burns admired so much that he said he would have been proud to have written it. As a youth, Wilson had learned something about birds while poaching on Scottish estates, but he did not become a serious student of ornithology until, after ten years as a weaver and an itinerant peddler, he left Scotland for America. In Philadelphia the great botanist William Bartram encouraged Wilson to try his hand at drawing birds. No one at that time was doing this, and new birds were still to be discovered in America, so it occurred to Wilson that he had found his life’s mission.

In April, 1807, he issued an elaborate prospectus of his American Ornithology. It was to be in nine volumes and would be illustrated by plates engraved and colored by hand. The first volume appeared in 1808, the second in early January, 1810. Later that month, Wilson packed the two quarto-size red-backed volumes in his luggage and started from Philadelphia on a two-thousand-mile journey west to the Mississippi and south to New Orleans, hoping to keep his expenses down to a dollar a day. He would combine field work and business, collecting birds while collecting subscriptions at $120 each for his masterwork, which would take nearly seven years—until 1814—to complete.

When Wilson passed through Louisville he met Audubon, who was 19 years his junior and not yet launched on his own monumental venture into ornithological publication. Audubon describes the historic meeting of the two men, who eventually became bitter rivals:

One fair morning, I was surprised by the sudden entrance into our counting-room [at Louisville] of Mr. Alexander Wilson, the celebrated author of the “American Ornithology,” of whose existence I had never until that moment been apprised. This happened in March, 1810. How well do I remember him, as he then walked up to me! His long, rather hooked nose, the keenness of his eyes, and his prominent cheek-bones, stamped his countenance with a peculiar character. . . . He had two volumes under his arm, and as he approached the table at which I was working . . . he immediately proceeded to disclose the object of his visit, which was to procure subscriptions for his work. He opened his books, explained the nature of his occupations, and requested my patronage.

I felt surprised and gratified at the sight of the volumes, turned over a few of the plates, and had already taken a pen to write my name in his favour when my partner rather abruptly said to me in French, “My dear Audubon, what induces you to subscribe to this work? Your drawings are certainly far better, and again you must know as much of the habits of American birds as this gentleman.” Whether Mr. Wilson understood French or not, or if the suddenness with which I paused, disappointed him, I cannot tell; but I clearly perceived that he was not pleased. Vanity and the encomiums of my friend prevented me from subscribing. . . . I rose, took down a large portfolio, laid it on the table, and shewed him, as I would shew you, kind reader, or any other person fond of such subjects, the whole of the contents, with the same patience with which he had shewn me his own engravings.

His surprise appeared great, as he told me he never had the most distant idea that any other individual than himself had been engaged in forming such a collection. He asked me if it was my intention to publish, and when I answered in the negative his surprise seemed to increase.

Audubon implied that vanity prevented him from subscribing. More likely it was near-poverty. He was at the point of failure in business. After five days in Louisville, during which Audubon gave him lodging and took him afield, Wilson proceeded on his way. It must have been a crushing experience for Wilson to find on the frontier an unknown man whose paintings were superior to his own.

When Wilson’s American Ornithology was completed it covered more than two hundred fifty species and was illustrated by seventy-six plates. The engravings by Alexander Lawson and his associates were no match for the more sophisticated work of Havell, who was to engrave Audubon’s plates in England.

In 1813, at the untimely age of forty-seven, Wilson died of exposure and fever after a field trip. Seven volumes were already in print, but there were two more to go. George Ord, a wealthy Philadelphia dilettante, brought the last two volumes to completion and later spared no pains to downgrade Audubon, who was beginning to appear on the scene.

It is quite likely that Wilson had been jealous of his potential rival, but Audubon had no hint of this until some years later when, after Wilson’s death, he read in the ninth and last volume of American Ornithology, in a biographical sketch by George Ord, the following paragraph from Wilson’s journal: “March 23, 1810—I bade adieu to Louisville, to which place I had four letters of recommendation, and was taught to expect much of everything there; but neither received one act of civility from those to whom I was recommended, one subscriber, nor one new bird; though I delivered my letters, ransacked the woods repeatedly, and visited all the characters likely to subscribe. Science or literature has not one friend in this place.” From then on there was a one-sided vendetta. Although Wilson was no longer living to defend himself, Audubon, writing about birds in his Ornithological Biography, delighted in pointing out Wilson’s “errors.”

Audubon’s plate of the Mississippi kite has long been a subject of controversy, because the lower bird appears to be a copy of Wilson’s earlier portrait. It has merely been flopped—reversed—a device that many a modern commercial artist has used so that it will not be readily apparent that he has copied. In fairness to Audubon, the figure might have been inserted by Havell, the engraver, who often added his own touches to Audubon’s arrangements so as to complete a plate.

The other side of the coin is that Audubon accused Wilson of copying his drawing of a bird that he called the “Small-headed Flycatcher.” He wrote: “When Alexander Wilson visited me at Louisville, he found in my already large collection of drawings, a figure of the present species, which being at that time unknown to him, he copied and afterwards published in his great work, but without acknowledging the privilege that had thus been granted to him.” Actually, Wilson’s figure and Audubon’s are in quite different positions, but the mystery is, what bird could it have been? A pine warbler, perhaps? No one seems to know. It is another of Audubon’s unknowns; his specimen was collected in Kentucky, Wilson’s purportedly in New Jersey.

In a sense Audubon was a relative latecomer. Linnaeus, the creator of the Systema Naturae, and his successor Gmelin, as well as a number of other workers, had already named and described a large percentage of the birds of eastern North America. Of the 38 species of wood-warblers normally occurring in eastern North America, 25 had been named even before Wilson published his work. Wilson described another ten but by the time Audubon came on the scene he was able to add only two new ones; Swainson’s warbler and the nearly extinct Bachman’s warbler, both furtive southerners. However, Audubon named ten warblers as new that proved to be only variants or obscure plumages of already well-known species. Only one species, Kirtland’s warbler, remained undescribed after Audubon. In all, Audubon described 23 valid new species of birds and 12 additional subspecies.

We owe a debt of gratitude not only to Wilson and Audubon but also to lesser-known artists of the day, such as Titian Peale, Alexander Rider, George White, and John William Hill, whose drawings helped our young nation recognize some of the birds that were then so little known.

The Fuertes Era

AS DR. ROBERT MENGEL COMMENTED in Scientific American, “The eulogists betray themselves when they say that Audubon’s birds were vastly superior to any that had gone before; they imply that nothing has happened since. Audubon has painted the birds, they seem to say, and that takes care of that.”

Hundreds of men and a few women have painted birds since Audubon’s day. In fact, we can even make quite a list of those whose drawings were published in the half century prior to 1900—Ada Apgar, J. Carter Beard, Daniel Girard Elliot, Richard Farlay, Theodore Jasper, Charles Maynard, Edwin Sheppard, and William Werner, to name a few. Better known were Robert Ridgeway, one of the greatest taxonomists of all time; Ernest Thompson Seton, who decorated his many nature books with marginal drawings and who drew birds rather well; and Abbott Thayer, who propounded the theory of countershading in nature. But it was at the meeting of the American Ornithologists’ Union, a scientific organization, in 1895 that the work of a new young artist, Louis Agassiz Fuertes, caused a furor.

Fuertes dominated bird art in the first quarter of the twentieth century, just as Audubon had reigned supreme nearly a century earlier. There is no doubt he was born under a lucky star, for at a very youthful age Fuertes was befriended and sponsored by two men of powerful influence: Abbott Thayer, who shaped his thinking as an artist, and Elliott Coues, who promoted him in scientific circles. Thayer and his son Gerald wrote the controversial tome Concealing Coloration in the Animal Kingdom, an exposition of the “laws of disguise through color and pattern.” Young Fuertes understood this principle instinctively and was one of Thayer’s greatest defenders. His later letters to his protégé, George Sutton, were full of this dogma. Yet he seldom observed it in his work, for if an artist were really to succeed at this kind of painting, one would not be able to separate the bird from the background. During his mid-thirties his correspondence reveals the spot he was in: Old Abbott Thayer berated him for painting birds that stood out from their surroundings, while Gilbert Grosvenor of the National Geographic and Frank Chapman of Bird Lore sent back drawing after drawing, demanding that the birds be made to stand out more clearly on the page, preferably in straight profile. In the end, and with some anguish, no doubt, Fuertes gave in to Grosvenor’s and Chapman’s wishes and usually ignored the three-dimensional play of light and shade in favor of local color—a concession that most bird portraitists make to the demands of ornithological illustration.

Louis Agassiz Fuertes Toucanet

One of the most difficult things for a bird artist to master is pterylography, the arrangement and patterns of feather tracts as they cover the bird’s body. Fuertes had an almost intuitive knowledge of this, and he was never discouraged even when attempting a bird in a difficult or foreshortened position. His touches of foliage and branchwork were always convincing. He obviously worked from living vegetation and studied its structure as carefully as he did that of his birds; he did not improvise his botanical accessories as did other artists of his generation. Audubon also used living plant material, but, as often as not, it was painted in by Mason, Lehman, or Martin. No bird artist since Audubon has used an apprentice in his own work.

Like Audubon, Fuertes was primarily a bird portraitist, and somehow he could not handle landscapes with equal skill. His perspective often seemed off; the bird and the background did not always jell unless he was painting the branch on which the bird was perched, or other immediate accessories. These were handled sensitively and skillfully.

Louis Agassiz Fuertes Goshawk

Although his passion for drawing birds was sparked by Audubon, Fuertes’s development can be traced, partly at least, to the influence of Archibald Thorburn and George Lodge of England, who in turn were admirers of Joseph Wolff. Wolff may be said to have initiated the new direction in bird portraiture after Audubon; Fuertes brought it to its highest degree of excellence, and most American bird portraitists are still influenced by him. As George Sutton pointed out, there was even a “Fuertes school of thinking,” which extended down to the tyro who went out on Sunday with binoculars. He saw the bird through his glasses, perhaps not too well, and his mind immediately went to a Fuertes drawing of that bird. The mental image filled the gap. He saw the bird as Fuertes drew it—the “Fuertes look”—not as it actually looked in the brief moment it perched before him. Today the beginning birder may not be familiar with the Fuertes colorplates. His mental image of the bird may have the “Eckelberry look,” the “Singer look,” or the “Peterson look,” depending on which bird guide he uses.

For some unaccountable reason, Fuertes never wrote a book, although he illustrated many. Among his few articles is a very well written series of six, “Impressions of the Voices of Tropical Birds,” in Bird Lore (1913–14). He seemed to mistrust his writing ability. Actually his letters make far better reading than those of most other literate men, partly because there is no pretense about them—they are all bounce, vigor, and life, and animated by his uninhibited sketches.

In later years Fuertes expressed a desire to get away from painting those composite illustrations of birds for which he was so much in demand. He wanted to paint canvases that had nothing to do with functional book illustration. At the show of bird art in New York’s American Museum of Natural History in 1925 he exhibited a large oil of a great horned owl in a trap against a background of dead leaves. “This is the way I really like to paint,” he said. “I’m going to do more of this from now on.” He never did. He was still working on some of the plates for the third volume of Forbush’s The Birds of Massachusetts when, on August 22, 1927, at the age of fifty-three, he was struck by a train while driving his car. He had just returned from Ethiopia (then Abyssinia) with some of the finest watercolors of his career.

Fuertes was a hard act to follow, and his several gifted contemporaries were overshadowed, much as Audubon overshadowed Wilson. Major Allan Brooks of Canada, a retired army officer, was considered Fuertes’s logical successor. He finished the plates in Forbush and during the next several years inherited many of the commissions that would probably have gone to Fuertes.

Brooks painted in watercolor and gouache on toned papers—grays, browns, and dull blues—a technique probably derived from his British mentors, Thorburn and Lodge. Parts of the drawings were handled in transparent watercolor, while the highlights and lighter tones were put on with tempera or with watercolor mixed with opaque white or gouache. During Fuertes’s later years, Brooks had won him over to this technique, and many of Fuertes’s later illustrations, such as his portraits in Forbush, were done in this manner.

Allan Brooks Passenger Pigeon

On the whole, paintings by Brooks are more lush than those by Fuertes, but his birds are not as sensitively understood. His backgrounds are somewhat stylized or contrived. One of his tricks was to use several quick brushstrokes to make leaves that could not be identified as from any specific kind of tree. At times his handling of backgrounds was very successful, especially when portraying the coniferous forests and the mountains of the Northwest he knew so well. His southeastern swamps are not as convincing.

Brooks often gave small birds an unnatural fullness at the nape of the neck, and frequently made them too large-headed and short-tailed. When presenting a frontal or quartering view of a bird’s head, he often gave it an owl-like aspect; even his small warblers sometimes have the look of little owls. He tended to draw “by the numbers,” starting with the beak and carrying his line to the tail. On the whole, however, his work has an attractive quality, even if there is a sameness to it, as though he were using the same bag of tricks.

Theodore Jasper painted 119 plates that were reproduced as chromolithographs in Studer’s Birds of North America (1897), but they cannot be regarded as a step forward, because two years earlier, at a meeting of the American Ornithologists’ Union, the work of the young Louis Fuertes had already created a sensation.

During the first quarter of the twentieth century, concurrent with Fuertes and Brooks, an increasing number of illustrators were making names for themselves by painting birds. Chester Reed illustrated his own pocket bird guides, which were the predecessors of the modern field guides. They were shaped rather like checkbooks, and the birds were arranged one on a page.

Schuyler Mathews, in his Field Book of Wild Birds and Their Music (1904), painted a number of songbirds, but most of them had the look of his pet canary, which he confessed he used as his basic model.

Two popular magazine illustrators, Charles Livingston Bull and Paul Bransom, had a decorative style, employing charcoal or a combination of charcoal and line. Each handled their medium in a similar manner.

Charles R. Knight was one of the more sophisticated painters of this period, but his specialty was murals and restorations of prehistoric animals; it is a pity he did not paint more birds. We must also mention in passing Courtenay Brandeth, Karl Plath, Emerson Tuttle, Robert J. Sim, Earl Poole, Olaus Murie, Edward Von Siebold Dingle, Walter Denslow, and Conrad Roland, among others. All had their distinctive styles.

Bruce Horsfall was another well-known figure in the world of ornithological illustration during the Fuertes-Brooks era. Equipped with a good background as an artist, having been trained in the academies of Europe, he knew how to handle paint better than most of his contemporaries, but he was far from the equal of Fuertes or Brooks in his understanding of his subject matter. He once admitted that he had painted every North American warbler at least four times but still could not tell one from another in the field. He painted numerous illustrations for Nature magazine and various Audubon publications. His brushwork was a bit too loose for some tastes, but the best of his work was very good, especially when painted from life.

R. Bruce Horsfall Least Bittern 1918

Edmund Sawyer, a contemporary of Horsfall’s, produced some creditable bird portraits for the Audubon junior leaflets. Notable was his excellent portrait of a robin, which was distributed by the millions, perhaps in greater quantity than any other bird portrait up to that time. His work was more studied and meticulous than Horsfall’s, lacking the freedom of the trained artist.

Rex Brasher, much publicized about sixty years ago, attempted to out-Audubon Audubon by producing a set of very large books that endeavored to portray all American birds (Audubon painted only 440 of the 750 or more species). The original Brashers were formerly on display at the Harkness Memorial near New London, Connecticut, but now are housed in the Connecticut State Museum of Natural History of Storrs, Connecticut. His output was prodigious, but in spite of a great deal of publicity at the time the work was published, it has not stood the test of time. The standards are much higher today.

Since Fuertes

OF THE MANY ARTISTS who in the past have painted North American birds, we can be most certain that two, Audubon and Fuertes, will be remembered far into the future. However, it is too early to assess the viability of the work of some of our living bird painters, several of whom are superb, reaching new standards of excellence. It remains for future critics to evaluate their durability in the evolution of bird art, in these changing times.

Fuertes’s birds are more accurate ornithologically than Audubon’s and almost invariably show more of the real life and essence of the species; but it must be remembered that Fuertes had predecessors to build on, while Audubon started from scratch. Audubon’s ideas were not influenced by the stilted or uninspired efforts of those men who had worked before him. The art of photography, newly born while Audubon was publishing his elephant folio, had not yet schooled the eyes or influenced the mind, as it has universally since then. We must realize that even though an artist has never used a photograph, he is subconsciously influenced by the visual discipline imposed by this modern medium. He either responds positively, if he is of the “academic” school, or negatively, if he is a “modern.” One thing is certain: Although Fuertes’s birds are more truthfully like the birds they depict, they usually do not make as effective wall decorations as the Audubon prints. However, had Fuertes not been so saddled with routine commissions for book and magazine illustrations, he might have produced more paintings that could be framed. Whereas Audubon reflected Audubon in everything he painted, Fuertes reflected more of the character of the bird, less of himself.

Shortly before Fuertes’s death in 1927, Dr. Frank Chapman of the American Museum of Natural History hired a young artist, Francis Lee Jaques, to paint backgrounds for the new-style habitat groups Chapman had conceived. “Lee,” as he was known to his friends, was perhaps the only artist of his generation not strongly influenced by Fuertes. He insisted he was not a painter of feathers and that he was more concerned with the bird in the landscape. The bird might perhaps be the focal point of an environmental display, but it should move in space, bathed in light and air. Having grown up on the Kansas prairie with a gun and a sketchbook, Jaques was particularly knowledgeable about waterfowl, and no one painted them better. Songbirds interested him less; he once commented, “The difference between warblers and no warblers—is very slight.” Actually he painted a goodly number of songbirds—for such publications as Florida Bird Life—but they were not up to the Fuertes standard. Several other young bird artists were beginning to make names for themselves as illustrators of bird books, but Jaques did not worry about competition. He once remarked to Sigurd Olson, “I’m not worried, because none of those artists know exactly how I feel. They might portray a bird, a rock, or a wind-blown pine better than I; but none of them can catch my particular feeling for these subjects, or my sense of at-homeness, belonging, and having lived there.” He was true to himself. Jaques brought the art of the museum diorama to its highest level. He is memorialized not only in many of the habitat exhibits in the American Museum of Natural History but also in the Peabody Museum at Yale, the Bell Museum in Minneapolis, the Boston Museum of Science, the museum at the Welder Wildlife Refuge in Texas, and elsewhere. He was also noted for the brilliant design of his scratchboard drawings and the decorative quality of his canvases.

Francis Lee Jaques Golden Twilight: Baldpates c. 1930

The late Walter Weber was inspired by both Fuertes and Allan Brooks. When his colorplates of Carolina parakeets and thick-billed parrots appeared as frontispieces in Frank Chapman’s Bird Love during the early 1930s, he was still so young that Jaques commented admiringly, “He paints birds so well that one would think he’s been at it for at least thirty or forty years.” Weber worked as a freelance first in Chicago and then in Washington, where he was soon put under contract by the National Geographic Society. This gave him security for the rest of his life, and he produced many excellent illustrations of birds and mammals for the Society’s magazine; but his commitment to the Geographic and its needs probably kept him from trying more experimental approaches to his art.

Walter Alois Weber Carolina Paroquet 1931

Walter Breckenridge, formerly director of the Bell Museum in Minneapolis, is another professional ornithologist whose painting was influenced by Fuertes. His earlier works were limited to illustrations in publications such as Birds of Minnesota, by T. S. Roberts, where several species were shown on a plate. Only since retirement has Breckenridge been free to paint birds for the fun of painting them, resulting in some of his best work.

In the 1940s, Athos Menaboni, an accomplished Italian mural painter who took up residence in Atlanta, Georgia, burst on the art scene with his Audubon-like compositions. Although he first exhibited in New York, his patrons in Atlanta soon snapped up his paintings before the paint was dry. His bird portraits were unique in that they were executed in thin oil on sized illustration board. At first glance they give the impression of being in watercolor, but they have a lucid transparency and smooth control made possible by the modified oil technique. An outstanding quality of Menaboni’s bird portraits was his handling of feather textures.

George Miksch Sutton Peregrine 1930s

The late George Sutton was often called the “dean of American bird artists,” a title that made him cringe because it suggested his age (past eighty). He had also been called a “Gentleman, Scholar, Author, Artist, Scientist, Explorer, Raconteur, Teacher, Philanthropist, and Connoisseur of Whale Blubber and Sundry Other Rare Culinary Delicacies.” But even this would not encompass all the accomplishments of this man, who was singled out by Fuertes as his favorite protégé. Sutton acted as the bridge between Fuertes and the succeeding generation of bird painters.

Although Sutton gave his life to academia—Cornell, the University of Michigan, and the University of Oklahoma—he had so many talents as author, artist, teacher, and lecturer that he always faced an inner struggle over the best use of his time. There are only 24 hours a day, and they pass too quickly for a creative man. He could have devoted his entire life to his art.

Sutton’s paintings spanned the gamut from field sketches and standard ornithological illustrations to sensitive and evocative watercolors of Arctic and Mexican birds. His watercolors are suggestive of Audubon, but with a difference: Sutton’s models were not wired up but were literally from life (although fresh specimens were used), more in the manner of his mentor, Fuertes. Whereas one of Audubon’s weaknesses was the artificial, rather glassy eyes of his birds, Sutton always started with the eye. Once he had given it the gleam of life, he proceeded from there and built the bird around it.

Sutton’s most rewarding accomplishment, he felt, was his work with young people. “As I watch them, considering what they have done, and see them achieving, I sense what immortality must be.” During the course of his teaching in three universities, he helped or influenced Dilger, Gilbert, Grossenheider, Malick, Mengel, and O’Neill, among others (see below).

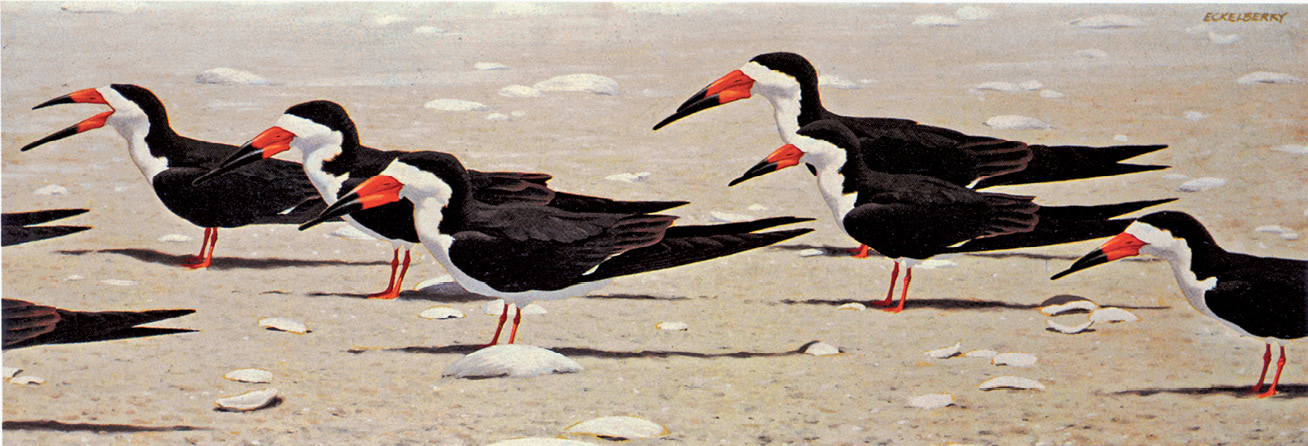

Don Eckelberry, whose work evolved from Fuertes-like bird portraiture to painterly environmental canvases, perhaps had the best mastery of pterylography and bird structure of any of his peers. His early discipline was acquired while painting all the birds of North America (about 1,250 figures of more than 750 species) for the three volumes of the Audubon Bird Guides by Richard H. Pough, published by Doubleday during the 1940s and ’50s. Later, like George Sutton, Eckelberry became enamored of the neotropical birds and painted from life many of the birds of Trinidad and Central America.

Don Eckelberry Black Skimmers 1958

Eckelberry draws a distinction between “bird illustration,” such as one does for bird books where the artist is told what to do, and “bird art,” which springs from the untrammeled impulses of the artist. Few artists are as articulate as Eckelberry, and like Sutton he selflessly instructed younger artists, especially at the Asa Wright Center in Trinidad, where he conducted seminars and classes. His later work has gone more toward canvases where the birds are subordinate to the landscape or are used as accents to the environment. He explained, “For me, art is self-realization. By combining descriptions and feelings of what I see and externalizing them, I comprehend reality—my own life. It is for others to make of that what they will.” Eckelberry is one of the very few bird artists to be elected a fellow of the American Ornithologists’ Union.

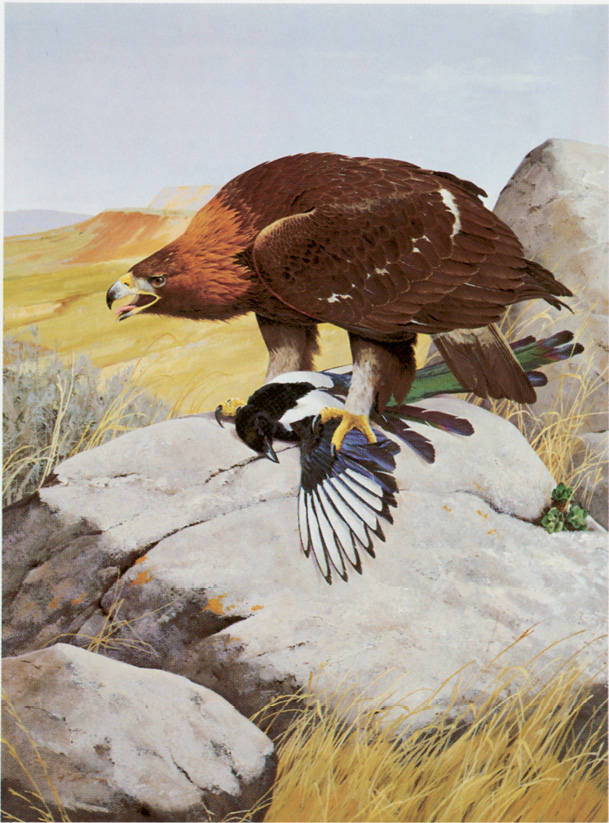

Guy Coheleach (pronounced Ko-le-ak) did not climb the ladder of success at the same speed as most other artists—he ran up. Trained at the Cooper Union Art School, he came to wildlife art not by the academic or museum route but by way of the jungle of Madison Avenue’s advertising-art world. He had always been deeply interested in wildlife, especially birds, and Eckelberry talked him into making the switch to bird and wildlife painting. Bringing his commercial expertise to bear on bird art, Coheleach met with immediate success.

Guy Coheleach Golden Eagle 1979

He is concerned about the future of wildlife and the environment and has donated many original paintings and the profits of many prints to save endangered species and to work for a better natural environment. Because of his earlier training he is one of the most professional wildlife artists and is not locked into any single approach or technique. If asked to do so, he can paint a near-Fuertes, a creditable Jaques, or a simulated Liljefors. Although able to paint in any style, he has finally settled down to the real Coheleach. Meanwhile he has helped other competent wildlife artists to make a good living by raising the level of prices they can ask for their work.

His gift for painting character, motion, and life into his birds is as deep as his thirst for adventure. A world traveler, Coheleach has climbed mountains; caught rattlesnakes and pythons; tracked eagles, lions, and rhinos; and been chased by elephants (even knocked down by one). He lives every day for what it is worth (in this way reminiscent of Audubon). Although he may draw dozens of study sketches before he touches brush to canvas, he paints rapidly—“The fastest brush in the East,” quips Eckelberry. “Not so,” Coheleach adamantly retorts. “I sweat blood.”

Manhattan may seem an unlikely birthplace for one of America’s finest and most prolific bird portraitists, but the late Arthur Singer found advantages there. The American Museum of Natural History was nearby on the west side of Central Park, and the Bronx Zoo was only a subway ride away. He became imprinted by the zoo at the age of three and by the time Singer was in high school, he was already selling his sketches. He trained at Cooper Union Art School, where he later taught layout and design. Singer was one of the few professionals who always met his deadlines. This dependability made him very popular with publishers. He gained a large following both in the United States and abroad through his illustrations in his bird guides as well as his limited-edition prints. Amongst other honors he received the Master Wildlife Artists’ Medal of the Leigh Yawkee Woodson Art Museum in Wausau, Wisconsin.

Arthur Singer Bald Eagles 1980

Singer’s approach was basically that of a skilled delineator in the Audubon and Fuertes tradition. He had no fear of typecasting, which kept him busy with commercial illustration, but more and more he painted for the galleries and to please himself. He scheduled at least one vacation trip a year into some area he had not seen or birded before. Like Audubon’s sons, Paul and Alan Singer are following in their father’s footsteps as wildlife artists.

Robert Verity Clem was one of the first contemporary bird artists to try a new direction. When he was very young his bird portraits were much like those of Fuertes. On one of his visits to the Peabody Museum at Yale, the late Rudolph Freund said to him, “You can draw a bird on a stick, but can you put it into a landscape?” This was a challenge, and Clem soon proved that he could. Most people know his work through the 32 magnificent colorplates in Shorebirds of North America (New York: Viking Press, 1967), but he now refuses to paint for reproduction, contending that even the best limited-edition prints cannot match the subtleties of an original. A true artist and a perfectionist, he paints as he pleases, and his clients do not dictate the subject matter. Shorebirds are his favorites. His birds, which once dominated the landscape, are now subordinate to it. He emphasizes the environment and its moods. Clem lives and paints on Cape Cod, where he has the sea and the shore at his doorstep.

Albert Earl Gilbert is an artist of whom Fuertes would have approved; his style when painting bird portraits in watercolor is sure and direct. He does not overwork his detail, yet everything essential is there. His concepts are nonderivative and always original. He seems to produce his orchestrations unself-consciously; his paintings read easily.

Albert Earl Gilbert Harpy Eagle 1980

Gilbert wanted to be an artist ever since his boyhood in Chicago, where he spent much of his time at the Brookfield Zoo. By the age of twelve he was sketching at the zoo under the tutelage of curator-artist Karl Plath. Later he received advice and criticism from George Sutton.

Gilbert has to his credit many fine paintings in standard ornithological monographs, notably the sumptuous Currassows and Related Birds, by Amadon and Delacour, and Eagles, Hawks and Falcons of the World, by Amadon and Brown. His paintings may be found in the American Museum of Natural History in New York, the Field Museum of Chicago, and many private collections.

For years Gilbert’s art has received wide exposure in the stamp program of the National Wildlife Federation, and in 1979 he won the Federal Duck Stamp competition. Using his windfall from the duck stamp, Gilbert launched his own publishing company, Steep Rock Wildlife Art, which featured his limited-edition prints. He was president of the Society of Wildlife Artists.

Kenneth Carlson, whose work is much admired by his fellow artists, studied at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts and began his career as a commercial illustrator. In 1970 he gave up the security of his commercial work to devote full time to wildlife painting. Although influenced by Bob Kuhn and the late Walter Wilwerding, much of his published work, such as his superb portraiture in Birds of Western North America (New York: Macmillan, 1974), has more the look of Fenwick Lansdowne. Lately he has been going the Bob Kuhn route. He says, “Birds have always been a challenge, but after painting them very detailed for many years, I am now trying to capture their essence in my painting, which is much harder to do than painting every feather.”

Kenneth Carlson Golden Eagle and Magpie 1978

Like Sutton, with whom he studied informally, Robert Mengel prefers his watercolor paints pure and transparent, without opaque colors or gouache. Also like Sutton, he is highly articulate about bird art and artists. He takes the view that if one can paint perceptively, one should be able to write perceptively about painting. We are left with the feeling that Mengel would have preferred an art career to an academic one. He has stated that his ultimate ambition is to be a good watercolorist, a good landscapist, and a sensitive interpreter of wild birds. His major ornithological work, Birds of Kentucky, includes several of his earlier watercolors, as does the Handbook of North American Birds.

Don Malick, who lived in Denver, was born in Olean, New York. He discovered the Macmillan edition of Audubon’s Birds of America when he was a young boy. He recalled “I would sit copying those marvelous compositions ’til past midnight, letting my school work slip badly.” George Sutton, however, was his greatest influence. Malick was a stronger draftsman than most of his contemporaries and painted directly, with less tickling of detail. Later on he shifted from straight bird portraits, such as those he painted for The Birds of Colorado while at the Denver Museum, to a more expansive kind of painting, such as we saw in his superb African canvases before his untimely death.

Donald Leo Malick Martial Eagle and Ground Hornbill 1978

Fenwick Lansdowne, of Victoria, British Columbia, was able to start making a full-time living from bird art before he reached the age of twenty. Born in Hong Kong of English parents in 1937, he came at an early age to Canada, where he contracted polio. This immobilized him for a long period, during which he started to draw under the guidance of his mother, herself an accomplished artist. By the time he was eighteen he held his first one-man show at the Royal Ontario Museum, where he received immediate acclaim for his precocious talent. He credits his inspiration to Allan Brooks, William Rowan, and Frank Beebe (western Canadians like himself), but his technique is quite dissimilar. Although his work is extremely detailed, it has a delicacy and deftness of touch that avoids the frozen or stiff quality so often inherent in highly meticulous work. His living portraits have appeared in several coffee-table art books as well as in the lavish Rails of the World, by Dillon Ripley, formerly secretary of the Smithsonian Institution.

Fenwick Lansdowne Anna’s Hummingbird 1977

Canada has an extraordinary number of wildlife artists, ranging in style from the late Terry Shortt, the dean of Canadian bird portraitists, to Lansdowne, who paints in the deft, detailed tradition of Audubon, to Robert Bateman, who paints more in the manner of Wyeth, tapping the underlying rhythms of life that have moved him deeply.

Terence (Terry) M. Shortt was born in Winnipeg and joined the staff of the Royal Ontario Museum in 1930, when he was only nineteen. After nearly half a century at the museum, he retired as chief artist of the art department. As in the case of Jaques, Gromme, and several other museum artists, retirement freed him to paint “for fun and for real.” His watercolor field sketches, painted in many countries, are a superb blend of artistic sensitivity and scientific observation. Many have been reproduced in several books. Some of the most exciting studies are in Shortt’s autobiography, Not as the Crow Flies—“being an account in essay form of experiences with critters, people and places on field expeditions for the Royal Ontario Museum.”

Terence M. Shortt Bald Eagle 1976

Another artist of Shortt’s vintage and background is Clarence Tillenius, one of Canada’s best-known wildlife painters. Born in Manitoba’s interlake country in 1913, he is a dedicated environmentalist who painted many of the dioramas in major museums across Canada and then devoted himself almost solely to easel painting. Right-handed by nature, he lost his right arm at the shoulder in a railway accident and then mastered the problem of painting with his left hand. Tillenius said, “Art that is to endure must always draw its strength from nature—that is, an artist must have a profound understanding of, and a feeling for, the elemental sources of things, the rhythms of existence that are not affected by passing fashions.”

Robert Bateman, one of the most inventive and successful of the new breed of wildlife painters, has been likened to Andrew Wyeth, except that Bateman favors acrylics rather than egg tempera. Like Wyeth, he establishes bold patterns, then works things over with glazes and scumbling until his finished painting is highly detailed. Yet no life is lost in the process; rather, he is able to gain life by digging into the subtleties—“more real than real.” Although he remains an abstractionist at heart because of his early training, Bateman overlays well thought out forms and patterns with meticulous detail, but not the detail of the delineator; rather, it is that of the skilled painter, which never loses the vitality of the subject. His paintings have a three-dimensional activity, a movement in space, that other wildlife artists envy, and there is usually an element of suprise.

Robert Bateman Vantage Point: American Eagle 1980

Bateman always depicts the bird with its uniqueness in mind, not the bias of the human observer. As he puts it, “I try to portray an animal living its own life independent of man.” There is biological or behavioral comment in most of Bateman’s paintings; they are not simply portraits or decorative arrangements. And they are invariably environmental.

A restless wanderer in search of subjects, Bateman has not only explored Canada’s wilder frontiers but has also sailed Australia’s Barrier Reef, paddled up the Amazon, landed in rubber Zodiacs in a dozen penguin colonies in the Antarctic, climbed the Himalayas in Nepal, and returned again and again to the game parks of East Africa. His limited-edition prints are published by Mill Pond Press in Venice, Florida.

George McLean is another star in Canada’s galaxy of fine bird artists. Born in Toronto, where he received his art training, he lives and paints near Owen Sound, Ontario. Birds of prey are his favorites, which he paints from life and from specimens. Like many another wildlife artist, he acknowledges a debt to Audubon, admiring his vignetted compositions that are so reminiscent of the masterful Japanese printmakers. More typical of his own style are his corner to corner landscapes embracing the bird or mammal. He has been deeply influenced by Bruno Liljefors and Bob Kuhn, and was given professional encouragement by Budd Feheley of Toronto. Like Bateman, whom he also admires, McLean uses large shapes in an abstract manner, to elevate the bird above a particular time and place.

George McLean Snowy Owl Above Walter’s Creek 1975

Barry Kent MacKay specializes in the Canadian avifauna he knows so well, especially birds of the shore; but he has also painted every species found in the Galapagos Islands, the first bird painter to do so. A multi-talented artist, MacKay writes about birds as well as he paints them.

Barry Kent MacKay Ternstones 1981

Glen Loates is another top-flight Canadian artist who received his early direction by stalking the exhibit halls of the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. His guiding influences can be traced through the Audubon-Fuertes line to Terry Shortt and particularly Fenwick Lansdowne, whose textural delicacy of feathers and leaves is reflected in Loates’s own deft technique. Loates, however, does not restrict himself to birds. He is equally at ease with mammals, fish, reptiles, insects, and plants. The detail and subtleties of the living animal or plant, rather than the overall landscape, fascinate him. Like Lansdowne, he is an extremely meticulous delineator rather than a painterly painter; but inevitably he has broken away from his mentor and has created his own distinctive style. A survey of his work can be found in The Art of Glen Loates, a large book published in 1977 by Cerebrus and Prentice-Hall of Ontario. Like George Sutton, Loates starts each picture by painting the eye of a subject and ends with the background detail. The plant and background material are painted on the spot, then taken back to the studio for reference. Some paintings take only a week, while others may take several months to execute.

Glen Loates Blue Jays

John Crosby, senior artist of the National Museum of Canada, produced a complete set of excellent bird portraits for the definitive Birds of Canada, by Earl Godfrey. He also painted a number of plates in another museum-sponsored publication, Birds of Colorado, by Bailey and Niedrach. His watercolor portraits, especially of warblers and other small birds, are fresh and accurate.

Ray Harm is primarily a delineator in the Audubon tradition. A mountain boy from West Virginia, he was already well grounded in wilderness lore when he went to Cleveland to study at the Cooper School of Art. His work came to the attention of Wood Hannah, founder of Frame House Gallery in Louisville, who commissioned him to paint a number of eastern birds for limited-edition prints that immediately found a large audience. Harm soon became the anchor man at Frame House. After being appointed artist-in-residence at the University of Kentucky he continued his association with Frame House, flying his own plane to all corners of the country to expand his files of field sketches. He is especially admired for the fine detail in his work.

Ray Harm Barred Owl

Charles Fracé elicits an immediate response from his fans by means of the backlighting of his subjects. A golden eagle is shown with a burst of light coming through murky clouds, touching the eagle’s crown, nape, and shoulders with gold; a gull is silhouetted against the water by a similar flash of light over the waves. Fracé does not always use this device, but his work is the antithesis of the frontally lit portrait. Because of his sensuous quality of mood and light he became one of the more popular artists represented by Frame House.

Charles Fracé Goshawk 1975