Don’t you sometimes find that Christmas is just a bit too much? We all get on each other’s nerves cooped up at home during the holiday period. That bloated feeling with all the Christmas pudding and turkey. The endless watching of sports on TV. The hangovers and stuffy atmosphere. The unwanted presents that you know you’ll have to recycle back for someone else’s birthday. The hopelessness of those New Year’s resolutions you cannot possibly keep. Yes, we all know how “merry” Christmas can be. In those moments, we can really empathize with Ebenezer Scrooge.

Herbert Weinstein, a sixty-five-year-old advertising executive, was no exception. As soon as the twelve days of Christmas were over, on the evening of January 7, 1991, he and his wife, Barbara, had a major argument in their twelfth-floor Manhattan apartment. This was the second marriage for each, and you may know what that can be like. Disrespectful comments over the other partner’s progeny were flying. Herbert’s response was to disengage from the arguing and withdraw from the battleground. So far, so good. But disengagement can have an uncanny way of winding up one’s partner. After all, everyone likes a good fight once in a while—it lets the steam out. So, not being one to bow out of a fight that easily, Barbara let fly, coming after Herbert and scratching at his face.

Something snapped inside Herbert. He grabbed his wife by the throat and throttled the life out of her. There she was, dead on the floor. That did not look too good, so Herbert opened the window, picked his wife’s dead body up, and threw her out. She did a free fall twelve floors down onto East Seventy-second Street, landing on the sidewalk below. Herbert thought it would look like an accident, but on reflection he realized it still didn’t look very good. So he crept out of the building, only to be nabbed by the police. They charged him with second-degree murder.

Things were looking bad for Weinstein, but he was a wealthy man and had a good defense team. And his lawyers suspected something unusual in the case. He did not have any prior history of crime or violence. They referred Herbert for a structural brain scan using MRI.1 They followed this up with a PET scan, which maps brain functioning. If you could see the images you wouldn’t have to be the world’s leading neurologist to notice that his brain is broken. It was incredibly striking—there was a big chunk missing from the prefrontal cortex. What exactly was happening here? Unknown to anyone—including Weinstein himself—a subarachnoid cyst was growing in his left frontal lobe. This cyst displaced brain tissue in both frontal and temporal cortices.

The neurologist Antonio Damasio was consulted during a pretrial hearing to render his opinion on Weinstein’s ability to think rationally and control his emotions. Skin-conductance data were admitted alongside the brain-imaging data to argue that Weinstein had an impaired ability to regulate his emotions and make rational decisions. The defense team went with an insanity defense, and Judge Richard Carruthers was favorably impressed by Damasio’s arguments and the testimony of the imaging experts. In a novel pretrial bargain, the prosecution and defense agreed to a plea of manslaughter.2 This carried a seven-year sentence in contrast to the twenty-five-year sentence Weinstein would have served if he had been convicted of second-degree murder.

It was a monumental decision. No court had ever used PET in this way in a criminal trial.3 For the first time, brain-imaging data had been used in a capital case prior to the trial itself to bargain down both the crime and the ensuing punishment.4

The case of Herbert Weinstein highlights yet again the importance of the brain in predisposing someone to violence. More specifically, the case suggests that a structural brain deficit in the left prefrontal cortex results in a functional brain abnormality that in turn results in violence. Cysts such as Weinstein’s have an unknown cause and can grow for a long time. They can also be benign, but experts in the case testified that the cyst resulted in brain dysfunction that substantially impaired Weinstein’s ability for rational thinking. That bolstered the credibility of his insanity defense.

Recall from chapter 3 that impairment to the frontal cortex is particularly associated with reactive aggression. Revisiting the events from that night we can see that Weinstein’s violence was reactive in nature. Arguments had preceded the attack, and his wife had attempted to scratch his face. These are the aggressive verbal and physical stimuli that provoked Weinstein’s violent response. Recall our earlier argument that spousal abuse can be caused by a lack of prefrontal regulatory control over the limbic regions of the brain, resulting in reactive aggression in the face of emotionally provocative stimuli. Factor in to the equation that Weinstein had no prior history in any shape or form of aggressive or antisocial behavior. In terms of timing, it seems reasonable to suppose that the onset of this medical condition was a direct cause of Weinstein’s extreme reactionary violence.

In this chapter we’ll build on Weinstein’s case in four different ways. We will burrow further into the anatomy of violence by arguing that the brains of some offenders are physically different from those of the rest of us.

First, for Herbert Weinstein the structural brain abnormality is so striking that we can all see it. But I’ll argue that many violent offenders have structural abnormalities. They may be so subtle that even highly experienced neuroradiologists cannot detect the abnormality, yet they can in practice be detected using brain imaging and state-of-the-art analytic tools.

Second, while Weinstein’s brain abnormality likely had its onset in adulthood, I’ll suggest that for most other offenders, something has gone wrong with their brain development very early in life. I’ll advance a “neurodevelopmental” theory of crime and violence—the idea that the seeds of sin are sown very early on in life.

Third, we’ll shift gears a bit in terms of causation. Weinstein’s case illustrates how a medical illness late in life can cause brain impairment—but what about younger offenders? We saw in chapters 3 and 4—where we touched on brain imaging and psychophysiology—that violent offenders have functional brain impairments. Rather like your car when it misfires or your computer when it runs slowly, there is something just not working right with offenders’ brains. So far, we have viewed this as a software problem. Maybe a bad birth messed up the program for normal development, or maybe poor nutrition was the culprit. But now what I’m suggesting is the possibility of hardware failure. The idea is that criminals have broken brains—brains anatomically different from those of the rest of us.

Taking a leaf out of Lombroso’s nineteenth-century book Criminal Man, I’ll argue that the world’s first criminologist was absolutely correct in espousing structural brain abnormalities as a predisposition to violence. He may have been wrong on the precise location in the vermis of the cerebellum, or the ethnic hereditability of these traits, but he was right on the mark in arguing for a structural mark of Cain. This may sound like we’re back to the “born criminal” and the destiny of genetics. While I have insisted so far that there is indeed in good part a genetic basis to violence, I’ll also highlight here the critical importance of the environment in helping to cause the structural brain deformations that we find in offenders.

Fourth, and finally, Weinstein’s case deals with severe violence, but are structural brain deformations restricted only to aggressive behavior? I’ll argue that they are not, and that their influence runs the gamut of antisocial behaviors and extends into nonviolent crimes—including even deception and white-collar crime. We’ll start this part of our journey with a trip back to those temporary-employment agencies in Los Angeles.

As you’ll recall from our earlier discussion of Randy Kraft and Antonio Bustamante, back in 1994 Monte Buchsbaum and I, along with my colleague Lori LaCasse, had shown from our PET functional imaging work that murderers have poor functioning in the prefrontal cortex as well as the amygdala and hippocampus. We had clearly demonstrated for the first time a functional brain abnormality in these homicidal offenders.5 At that time we were quite ecstatic.

Yet that exhilaration was tempered by a dose of skepticism. For one thing, this was a forensic sample—they were all referred by their defense teams, who suspected that something might be wrong. Would our findings apply to the general population? For another thing, they were all murderers—would our results apply to those who showed a broad range of antisocial behavior? Furthermore, we had shown the presence of functional abnormalities, but we had not really tested Lombroso’s hypothesis of physical brain anomalies. How could we overcome these methodological challenges?

The answers all came from temporary-employment agencies. You’ll recall from chapter 4 that while prospecting in California I struck gold at temp agencies. There we were able to recruit psychopaths and individuals with antisocial personality disorder. These individuals are free-range violent offenders who are running around right now in the community committing rape, robbery, and murder while you read this book. Robert Schug, one of my gifted PhD students with unusual forensic skills, conducted painstaking in-depth clinical interviews with our participants to assess which ones were psychopaths. We then set to work scanning our sample using anatomical magnetic resonance imaging—aMRI. Unlike functional imaging, aMRI gives a high-resolution image of the anatomy of the brain—just what we need for prying into the structure of the criminal brain.

After just four minutes with a subject we are able to acquire many images of the brain’s structure. Then the hard work begins. After brain scanning, we use sophisticated computer software combined with our detailed knowledge of brain anatomy. We identify landmarks in the brain scans that pinpoint exactly where the orbitofrontal cortex and amygdala are. As with a bacon-slicer, we dissect the brain into slices as thin as one millimeter. There are over a hundred of these slices as we move in a coronal direction—from the forehead to the very back of the head. Having a thin slice of a brain results in good spatial resolution—we can visualize tissue as tiny as one cubic millimeter. Just as for your digital camera or TV, the higher the number of pixels within a given area, the better the resolution, and the clearer and sharper the picture.

Then, on each slice, using our neuroanatomical landmarks—the sulci, or grooves, in the brain—we painstakingly trace the area of the brain structure in question. You can see one slice from the prefrontal cortex on the left side of Figure 5.1, in the color-plate section. On the right side you can also see a three-dimensional rendering of a quadrant cut out of the skull to reveal below it the underlying brain tissue in one of our subjects. Just like a slice of bacon that has both red meat and white fat, our brain slices have two tissue types. We first have to trace around the “gray” matter in each slice—the meat, colored green here. This separates the neural tissue from the fat—the white matter—so that we can compute the area of neurons. Add up all these gray neuronal areas across all slices, and we have the number we want—the cortical volume of the brain region of interest.

So what do we find in the prefrontal cortex? Those with a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder—lifelong persistent antisocial behavior—had an 11 percent reduction in the volume of gray matter in the prefrontal cortex.6 White matter volume was normal. Antisocial bacon has plenty of fat—just not enough meat, not enough neurons. As we saw in chapter 3, the prefrontal cortex is centrally involved in many cognitive, emotional, and behavioral functions, and when it is impaired, the risk of antisocial and violent behavior increases.

Our antisocial individuals did not differ from controls in whole-brain volume, so the deficit was relatively specific to that critical prefrontal cortical region. But perhaps the brain deficit is not causing antisocial behavior. After all, antisocial individuals often abuse alcohol and drugs, and this could account for the prefrontal gray matter reduction. We therefore created a control group who did not have antisocial personality disorder, but who did abuse drugs and alcohol. We then compared the two groups. The result? The antisocial group had a 14 percent reduction in prefrontal gray volume compared with the drug-abuse control group, a slightly bigger group difference than that between normal controls and antisocials.

So drugs are not the cause of the structural brain deficit, but questions still remain. Prefrontal structural deficits have been found in other psychiatric disorders. We also know that those with antisocial personality disorder have higher rates of other mental illnesses, including schizotypal personality, narcissism, and depression.7 Could the brain impairment have nothing to do with antisocial personality disorder but instead be linked to a different clinical disorder that our antisocials also happened to have?

To deal with this, we created a psychiatric control group that was not antisocial but that was matched with the antisocial group on all the clinical disorders that the antisocial group had. Yet again, we found that the antisocial group had a 14 percent prefrontal volume reduction compared with this psychiatric control group. Our findings cannot be explained away by a psychiatric third factor.

Could the answer instead be family factors? In this case, we think not. We controlled for a whole host of social risk factors for crime, including social class, divorce, and child abuse, but found that the prefrontal cortex–antisocial relationship held firm. And unlike the case of Herbert Weinstein, there were no visible lesions in our antisocial subjects that could account for the volume reduction.

We are left with the possibility that this structural impairment has a subtle early origin. For whatever reason—be it environmental or genetic—the brain is not developing normally throughout infancy, childhood, and adolescence. We’ll come back to this “neurodevelopmental” idea later.

The MRI brain scan of Herbert Weinstein showed enormous structural impairment that was very visible. But if you were to compare the MRI scan of an antisocial individual with that of a normal person, you would not see the 11 percent reduction in gray-matter volume. That reduction corresponds to just half a millimeter in thickness of the thin outer cortical ribbon that is colored green in Figure 5.1.8 The difference is visually imperceptible not just to your eye but also to the eye of the world’s best-trained neuroradiologist. Indeed, an expert neuroradiologist would actually judge the brain scan of the antisocial individual to be quite normal. And yet it’s not.

We know it’s not normal only because we are not making a clinical judgment such as medical practitioners make who are looking for visible tumors. We are not taking a brief, global look at this slice to discern outright signs of pathology, as is common neuroradiological practice. We are not looking for a big hole in our slice of bacon. Instead, we are spending hours painstakingly computing the precise volume of gray matter in the prefrontal cortex using brain-imaging software. Doing that, we can identify small differences that have important clinical significance. Herbert Weinstein is just the tallest tree in a forest of brain-impaired offenders. Below such visibly striking cases are a host of violent offenders with more subtle but equally significant prefrontal impairments. Yet in clinical practice such sharks will slip away entirely unnoticed.

Let’s face it, findings come and go. Our study was the first to demonstrate a structural brain abnormality in any antisocial group. But perhaps it was just a fluke. We therefore conducted a meta-analysis that pooled together the findings of all anatomical brain-imaging studies conducted on offender populations—twelve in all—and found that this specific area of the brain is indeed structurally impaired in offenders.9 Since this meta-analysis, yet more studies have observed prefrontal structural abnormalities in offenders.10 The findings are not a fluke.

To make better sense of what we found, and to understand more fully the implications of this specific structural brain abnormality, we need to take a quick trip to a neurologist’s clinic in Iowa. As it happens, it is the clinic of the neurologist who consulted in the pretrial hearing of Herbert Weinstein—Antonio Damasio.

I have briefly mentioned earlier how Damasio, then at the University of Iowa and now at the University of Southern California, made truly groundbreaking contributions to our knowledge of how the brain works. A lot of this knowledge has come from the study of unfortunate individuals who, for one reason or another, have suffered a head injury resulting in brain damage. The silver lining to these clouds, from a scientific standpoint, is that by taking together all the clinical patients with damage to one specific brain region, and by comparing them to patients with lesions in different areas, we can draw conclusions on the critical functions of that brain region. Together with his equally brilliant wife, Hanna Damasio, and other colleagues, Antonio has made fascinating deductions from these patients about the functions of some areas of the prefrontal cortex and related regions, including the amygdala.

One group of patients had lesions localized to the ventral prefrontal cortex, the lower region of frontal cortex. It includes the orbitofrontal cortex, which sits right above your eyes, and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which is in line with your nose. The patients showed a striking pattern of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral features that set them apart not just from normal controls, but also from patients with lesions outside of this brain area.11

First, at an emotional level, while their electrodermal response system is otherwise intact and responsive, patients with ventral prefrontal damage do not give skin-conductance responses to socially meaningful pictures such as disasters and mutilations. The ventral prefrontal cortex is involved in coding social-emotional events. It connects to the limbic system and other brain areas to generate appropriate emotional responses within a social context, measured here by a sweat response. Without that neural system in place, the individual is emotionally blunted—and we saw earlier that psychopaths and those with antisocial personality disorder are similarly emotionally blunted and lacking in empathy.

Second, at a cognitive level, such neurological patients make bad decisions. In a psychological test called the Iowa gambling task, which was developed by the neurologist Antoine Bechara, subjects have to sort cards into one of four piles. Depending on which pile they place their card in they get monetary rewards or punishments. Unbeknownst to the subject, the decks are loaded. If they pick decks A or B, they might initially get large rewards, but eventually they are hit by even larger losses. Decks C and D give smaller rewards but they also yield much smaller punishments. Over the course of one hundred card plays, normal subjects learn about halfway through to avoid the high-reward/high-loss decks A and B. They instead persist in picking decks C and D, which ultimately give them the best payoff. They show good decision-making in the face of competing rewards and punishments. Patients with ventral prefrontal lesions don’t. They instead keep making bad decisions by picking the bad decks.12

Even more interesting is what normal individuals show in terms of their sweat responses during the task. About halfway through the task they become cognitively aware of which decks are bad, and which are good. Just prior to that, when they are consciously unaware of the good and bad decks, they contemplate picking from a bad deck. What Antoine Bechara saw on the polygraph was a skin-conductance response (a somatic marker), a bodily alarm bell warning them that they were about to embark on a risky move. Subconsciously, their body knows that bad news is just around the corner, and that they should hold back on their response—but consciously their brain does not. Very soon after this somatic alarm bell rings, normal individuals change their strategy and switch to the good decks—and they become cognitively aware of what’s going on. The ventromedial lesion patients? No alarm bell. So they continue to pick cards from the bad decks.

It’s not surprising, then, that psychopaths make bad decisions and mess up their own lives as well as those unfortunate enough to be within their social circle. As we saw in chapter 4, the lack of autonomic, emotional responsivity results in an inability to reason and decide advantageously in risky situations. This in turn is very likely to contribute to the impulsivity, rule-breaking, and reckless, irresponsible behavior that make up four of the seven traits of antisocial personality disorder. So we can understand how structural abnormalities to the prefrontal cortex could later result in antisocial personality—they could be the cause of the functional autonomic abnormalities we documented in the last chapter.

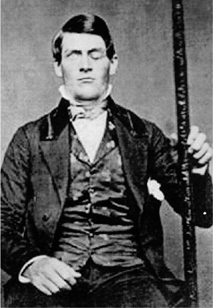

The third striking characteristic of these patients, at a behavioral level, is that they exhibit psychopathic-like behavior. A classic example of this, which took place more than 150 years ago and highlights the intricate link between brain and personality, is the case of Phineas Gage. It’s an unusual story that has been told before in neuroscience circles, but it is well worth retelling here.

Gage was a well-respected, well-liked, industrious, and responsible foreman working for the Great Western Railway. The fateful day was September 13, 1848. He was organizing the destruction of a large boulder lying in the path of the projected railway track. The work team had chiseled a hole into the boulder for the gunpowder and sand. The gunpowder was then poured into the hole. It was four-thirty in the afternoon.13

The next step should have been an apprentice pouring sand on top of the gunpowder. Gage was standing by with a metal tamping rod that was three feet seven inches long and one and a quarter inches in diameter. He was on the verge of using the rod to tamp down and compress the sand on top of the gunpowder to potentiate the explosion. At that critical moment, Gage was distracted by a conversation with his co-workers. After a few seconds he turned back to the boulder, believing that sand had been placed on top of the gunpowder. It had not. He tamped down with the rod right on top of the exposed gunpowder. The metal rod rubbed against the rock and created a spark that ignited the gunpowder. It transformed the tamping rod into a lethal spear that blasted its way right through the head of Phineas Gage.

Gage had been stooped over the hole as he tamped down with his hand. The rod entered his lower left cheek and exited from the top-middle part of his head, creating an open flap of bone on the top of his skull. You can see this flap in Figure 5.2 and the bone-shattering damage the rod created. The deadly missile flew through the air, landing eighty feet away, while Gage was hurled to the ground.

Understandably, all the railway workers thought Gage was as dead as a doornail. But after a couple of minutes he began to twitch and groan, and they realized that he was still alive. They put him into an oxcart and took him to the nearest town. He was carried upstairs into a hotel room and a doctor was summoned. What was the treatment in the nineteenth century when you had a tamping rod blown through your brain? Rhubarb and castor oil.

Figure 5.2 Skull of Phineas Gage

You would not think Gage stood a snowball’s chance in hell of surviving. But what a miraculous remedy rhubarb and castor oil turned out to be! Gage lost his left eye, but in no less than three weeks, he was out of bed and back on his feet. Within a month Gage was walking around town creating a new life for himself. And it truly was a new life. For in the words of his friends, acquaintances, and employers, he was “no longer Gage”:

He is fitful, irreverent, indulging at times in the grossest profanity (which was not previously his custom), manifesting but little deference for his fellows, impatient of restraint or advice when it conflicts with his desires, at times pertinaciously obstinate, yet capricious and vacillating, devising many plans of future operations, which are no sooner arranged than they are abandoned in turn for others appearing more feasible. A child in his intellectual capacity and manifestations, he has the animal passions of a strong man. Previous to his injury, although untrained in the schools, he possessed a well-balanced mind, and was looked upon by those who knew him as a shrewd, smart businessman, very energetic and persistent in executing all his plans of operation. In this regard his mind was radically changed, so decidedly that his friends and acquaintances said he was “no longer Gage.”14

We see here, very clearly, that Gage had been transformed from a well-controlled, well-respected railway worker into a pseudo-psychopath—an individual with psychopathic traits. Like many patients with frontal-lobe damage, he was impulsive, irresponsible, and was reputed to have been sexually promiscuous and a drunkard.15 He was fired by his employer because he was unreliable. He took on a series of jobs and moved around, switching from one job to another. Eventually he went on tour with the tamping rod and appeared in Barnum’s American Museum in New York and other public shows (see Figure 5.3). Among his many jobs he worked at an inn in Hanover, New Hampshire, in 1851, looking after horses. A spirited, risk-taking adventurer, he even spent several years in Chile as a stagecoach driver before traveling to California, where he worked on a series of farms until his premature death on May 21, 1860, after a series of epileptic seizures. Despite a most remarkable recovery from what should have been a mortal wound, that tamping rod he carried with him for the remainder of his life eventually got the better of him.

The case was such a remarkable one that medical doctors at the time scoffed at the idea that anyone could survive such an injury, and viewed it as a hoax. It could not possibly be true. While it was indeed a true case, could it nevertheless be unique? Can accidental damage to the prefrontal cortex really transform an otherwise normal, law-abiding individual into a capricious, psychopathic–like, antisocial individual?

Figure 5.3 Phineas Gage at Barnum’s American Museum holding the tamping rod that destroyed his prefrontal cortex

The answer can be found back in Antonio Damasio’s and others’ laboratories. A large body of evidence has now convincingly shown that adults suffering head injuries that damage the prefrontal cortex—especially the lower, ventral region—do indeed show disinhibited, impulsive, antisocial behavior that does not conform to the norms of society.16

But you could counter that adults have brains that are relatively fixed. What about children, whose developing brains show much greater plasticity? Does damage to the prefrontal cortex in youngsters also lead to antisocial behavior? Overwhelmingly, studies of the behavioral changes that follow head injuries in children find that conduct disorder and externalizing behavior problems are common.17, 18 While some other children develop internalizing behavior problems like anxiety and depression,19 there is little doubt overall that head injuries in children predispose them to impulsive, dysregulated behavior.20

But what if the damage to the prefrontal cortex occurs really early during infancy? Surely there is enormous plasticity of the brain at this developmental stage, allowing it to recover lost functions and to resume normality. Clinical cases of such selective prefrontal damage are rare, but they confirm that prefrontal lesions very early in life can directly lead to antisocial and aggressive behavior. A study from Damasio’s laboratory reported on two cases—one female, one male—who suffered selective lesions to the prefrontal cortex in the first sixteen months of life.21 Both showed early antisocial behavior that progressed into delinquency in adolescence and criminal behavior in adulthood, and included impulsive aggressive and nonaggressive forms of antisocial behavior. Both also had autonomic deficits, poor decision-making skills, and deficits on learning from feedback. Yet again we see that triad of traits that Antoine Bechara and Antonio Damasio clearly documented in those suffering prefrontal damage in adulthood—psychopathic behavior, autonomic impairments, and reduced somatic markers.

I know what you’re thinking. The clear limitation is that we are dealing with only two cases—one case more than the one presented by Phineas Gage. However, another laboratory reported on nine cases of children who suffered frontal lesions in the first ten years of life.22 All nine suffered behavioral problems after the injuries, with seven of the nine developing conduct disorder. Even in the case of the remaining two, they both exhibited either impulsive, labile behavior or uncontrollable behavior.

These cases, when taken together, strongly suggest that damage to the prefrontal cortex can directly lead to antisocial and aggressive behavior. It’s an important point. Brain-imaging research showing that murderers and those with antisocial personalities have prefrontal abnormalities demonstrate that a relationship exists. But do prefrontal structural and functional impairments cause crime and violence—or does violence cause the brain impairment? Violent offenders get into fights, and so can acquire “closed” head injuries: the skull is not broken but there is internal damage to the brain. It’s certainly possible, yet neurological case studies showing that prefrontal impairments in infancy, adolescence, and adulthood are later followed by antisocial, aggressive, and psychopathic-like behavior are telling. They provide striking support for a causal explanation flowing from prefrontal impairments to a disinhibited personality to violence.

We have seen from MRI studies that antisocial individuals in the community have structural brain impairments. We have also seen from the clinic that patients with head injuries causing prefrontal structural damage develop antisocial behavior and a loss of somatic markers, resulting in poor decision-making and maladaptive social behavior. We were therefore finding interesting similarities between our antisocial temp workers and the neurological clinical cases of Antonio Damasio and his colleagues. We were excited by these initial findings and wanted to dig deeper into these parallel findings from community to clinic. Two specific issues came to the fore.

First, the autonomic, emotional impairments in the head-injured patients of Damasio and Bechara raised the question of whether or not our antisocial temp workers also showed somatic marker impairments. This was a hypothesis that we tested out. As you may recall from chapter 4 we put our subjects through a stress task in which they had to talk about their worst faults. As pointed out by Damasio, this is a very appropriate task in the context of the somatic-marker hypothesis because it elicits secondary emotions—embarrassment, shame, guilt—that are the province of the ventral prefrontal cortex.23

We found that our antisocial, psychopathic subjects not only had a significant volume reduction in prefrontal gray matter, but also showed reduced skin conductance and heart-rate reactivity during the social stressor task. Sure enough, they did lack somatic markers, just as Damasio’s prefrontal patients did. Furthermore, when we divided our antisocial group into those with particularly low prefrontal gray volumes and those with near-normal volumes, we found that it was the former group—those with the structural prefrontal impairment—who particularly showed somatic-marker deficits.24 We were finding an interesting convergence of somatic-marker impairments, prefrontal structural deficits, and antisocial behavior that bore a striking resemblance to the findings on Damasio and Bechara’s patients.

The second issue concerned the localization of the structural impairment. Where exactly within the prefrontal cortex did our antisocial, psychopathic individuals have reduced gray-matter volume? Damasio had written an editorial on our original findings, posing the question of whether in future work the deficit may be localized in orbital and medial sectors of the prefrontal cortex.25 Recall that the tamping rod entered underneath Phineas Gage’s eye and traveled straight up his prefrontal cortex. Hanna Damasio had demonstrated from her careful and rigorous reconstruction of the tamping-rod accident that the damage to Gage’s brain was localized to the ventral and orbitofrontal part—the lower region—and also the medial or middle part of the prefrontal cortex.26 What would we find if we made a more detailed analysis of the precise location of the prefrontal volume reduction in our antisocials?

Dividing up the sectors of the prefrontal cortex involved much more complex sulcal landmark identification and tracing of slices; it took us literally years to complete, but eventually we got there. You can see in Figure 5.4, in the color-plate section, what we did. You are looking head-on at one of our antisocial subjects, and we are taking a slice through the frontal cortex. From top to bottom, moving from twelve o’clock to six o’clock, these regions consist of the superior frontal gyrus, middle frontal gyrus, inferior frontal gyrus, orbitofrontal gyrus, and the ventromedial area.27 In which sector did we see a significant volume reduction in those with antisocial personality disorder?

Three of the five sectors turned up trumps. As Antonio Damasio would have predicted, antisocial individuals showed a 9 percent bilateral reduction in the orbitofrontal gyrus, together with a 16 percent reduction in the volume of the right ventromedial prefrontal cortex. It is structural impairment to the ventral region of the prefrontal cortex that seems to be particularly implicated in antisocial, psychopathic behavior—the same brain region devastated by the tamping rod on that fateful day for Phineas Gage in 1848.

The third sector provided us with a different but complementary perspective to consider. Our antisocial subjects had a 20 percent volume reduction in the right middle frontal gyrus. In chapter 4 we discussed how neuropsychological research had demonstrated poorer “executive functioning” in antisocial and psychopathic individuals—reduced ability to plan ahead, regulate behavior, and make appropriate decisions. The brain areas classically associated with these executive functions lie in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. “Dorso” refers to top and “lateral” refers to side—so “dorsolateral” is the upper, side part of the prefrontal cortex. If you look at Figure 5.4, that’s exactly where the middle frontal gyrus is located. And if we look further into the functioning of this brain area, impairment in antisocial offenders makes quite a lot of sense.

Let us consider some of the normal functions of the middle frontal region that have been gleaned from functional-imaging and brain-lesion studies—functions that could well be impaired in offenders. First, the middle frontal gyrus, which makes up Brodmann areas 9, 10, and 46, is part of the neural circuitry that subserves fear conditioning.28 We saw earlier that criminals and psychopaths have poor fear conditioning. Second, it plays a role in inhibiting behavioral responses,29 and we know that offenders frequently show disinhibited, impulsive behavior.30 The middle frontal gyrus is also involved in moral decision-making,31 and offenders have impaired moral judgment and break moral boundaries.32 It is further involved in choosing delayed rewards as opposed to immediate rewards,33 and it is well documented that offenders are less able to delay gratification.34, 35 It is activated by empathy to pain stimuli,36 and antisocial individuals lack empathy.37 This prefrontal subregion is also activated when we look inward and evaluate our own thoughts and feelings.38 Offenders are characterized by a lack of insight into the harm they perpetrate on people around them.39

Clearly the middle frontal gyrus, which is significantly compromised in those with antisocial personality disorder, is heavily involved in cognitive, affective, and behavioral characteristics that antisocial individuals are deficient in. These deficiencies in turn contribute to their antisocial tendencies. We can complete the circle from brain structure to functional deficiencies to antisociality.

In a similar vein, there is more to the ventral region of the prefrontal cortex than effective decision-making. We know that it is involved in controlling and correcting punishment-related behavior,40 and in what neuropsychologists call “response perseveration.”41 And yes, recidivistic offenders are revolving-door guests in prisons. They seem unable to learn from their mistakes. They keep on making the same behavioral responses that resulted before in punishment and prison—what psychologists call perseveration.42 Fear conditioning is another process governed by the ventral prefrontal cortex, and we have seen that offenders have deficits in this area.43 The ventral area has also been implicated in compassion and care for others,44 as well as sensitivity to others’ emotional states.45 Let’s face it, we all know that criminals and psychopaths are not the most caring people in the world.46 As with the middle frontal gyrus, insight47 and behavioral disinhibition48 are also subserved by this ventromedial region. Offenders are disinhibited and psychopaths lack self-insight. Interestingly, the ventral prefrontal cortex also helps to reduce negative emotions during parent-child interactions,49 and offenders were likely as children to have thrown temper-tantrums with their parents. Emotion regulation is another ventral prefrontal function,50 and emotional dysregulation characterizes impulsively aggressive individuals.51

Taking both dorsal and ventral structures together, there are quite compelling reasons to believe that structural impairments to these regions can give rise to a constellation of social, cognitive, and emotional risk factors that predispose someone to antisocial behavior and an antisocial personality. The fact that both ventral and middle frontal brain regions contribute to some of the same functional risk factors for antisocial behavior—poor fear conditioning, lack of insight, disinhibition—highlights the salience of these well-replicated neurocognitive risk factors. It also tells us that an outcome of antisocial behavior may be especially likely when both of these regions are structurally compromised.

So far we have dug deeper into the prefrontal cortex and discovered that the ventral and middle frontal gyrus are the key culprits when it comes to crime. But these brain areas are guilty not only of their crimes as charged. Our next level of probing of the prefrontal cortex will implicate these same subregions in a different but equally fundamental societal question—why are men more violent than women?

There’s no escaping the fact. Men are meaner than women. But why? Sex differences in crime and violence have traditionally been put down to sex differences in socialization. If you have a little girl, you give her a doll to look after. If you have a little boy, you give him a toy gun to shoot other kids with. We socialize boys and girls differently, and that’s why boys bully more than girls. It’s seemingly that simple. But have the social scientists really got it right?

An answer can be found by exploring the geography of the prefrontal cortex. What I never told you about in our temp study is that we started off testing women as well as men. But we soon gave up trying to recruit female felons. You women out there are the wonderful angels that make the world go round. It’s we men that maketh mayhem. We had recruited just seventeen women in our sample and we were finding that they were not giving us a lot in terms of crime and violence. Plus, our money for the study was tight. So when the going got tough, we dumped the dames and recruited the tough guys. That was a mistake in retrospect, but we still had just enough women in our sample to test a controversial counterhypothesis to differential socialization as a cause of sex differences in crime. Could it be that there are fundamental brain differences between men and women that explain why men commit more crime?

We compared men with women on prefrontal brain volumes. Men had a 12.6 percent volume reduction in the orbitofrontal gray compared with women.52 That’s the underneath part of the prefrontal cortex. Men with reduced ventral gray were more antisocial than men with normal ventral gray volumes. We’ve seen that already, but what was new in our analyses was that women with reduced ventral gray volumes were more antisocial than women with normal gray volumes. We get the same brain effect in antisocial women that we find in antisocial men. Hold these findings in your prefrontal cortex’s working memory for a minute.

Men, of course, were found to be more antisocial and criminal than women, replicating a worldwide finding. No big deal. But what if we look again at this sex difference in crime, this time controlling for the sex difference in ventral gray volume? If we make men and women statistically the same in terms of their ventral volume, we cut the sex difference in crime by 77 percent.53 So more than half of the reason men and women differ in crime seems to be because their brains are physically different.

I’m not saying that all the difference in crime between men and women can be put down to the brain. And I’m certainly not saying that we should ignore differences in socialization and other social and parenting influences. But what I am arguing is that there are fundamental neurobiological differences between men and women that can help explain the gender difference in crime. It’s also striking that we find sex differences in the very same frontal sectors that are linked to antisocial behavior—men and women did not differ in prefrontal sectors that are not related to crime.

These findings do not come out of the blue. Sex differences in prefrontal gray have been documented in several other MRI studies. One imaging study found a 16.7 percent reduction in orbitofrontal volumes in men compared with women.54 Three other studies have found this same sex difference,55 including one large study of 465 normal adults.56 Men have also been reported to show lower activation of the orbitofrontal cortex compared with women when performing a wide variety of cognitive and emotional tasks, including verbal fluency,57 working memory,58 processing threat stimuli,59 and working memory during a negative emotional context.60 Men simply have different brains from women, and it’s pointless to cover up and ignore these fundamental sex differences.

The position so far looks like this: We’ve seen that offenders have structural impairment to the prefrontal cortex. We’ve also seen that they have poor functioning of this same brain region. We documented in a meta-analysis of forty-three brain-imaging studies of offenders involving 1,262 subjects that these structural and functional prefrontal deficits are replicable findings.61 The structural prefrontal impairment partly explains the sex difference in crime. It’s hard to escape from the conclusion that impairment to this brain region—through either environmental or genetic causes or both—predisposes some to an antisocial, disinhibited, impulsive lifestyle.

But before moving on, let’s underscore an important fact: no proposed cause of offending—whether it be social or neurobiological—inevitably results in crime and violence. While the dramatic case of Phineas Gage from Vermont in 1848 originally set up the prefrontal dysfunction theory of psychopathic and antisocial behavior, three more clinical cases strike a chord of caution lest we take this theory too far.

The first is the remarkable case of an individual known as the Spanish Phineas Gage—referred to here as SPG—a twenty-one-year-old university student living in Barcelona. It was 1937, the Spanish Civil War was raging, and nobody was safe. One fateful day he found himself upstairs in a house being pursued by the opposition in this civil struggle. Almost cornered, he threw open the window, climbed out onto the windowsill, and made a bold attempt to escape by shinnying down the drainpipe on the outside wall.

Unfortunately for SPG, the pipe was old, and it broke away from the wall. SPG clung on to it for dear life, falling down onto a spiked metal gate. His head was impaled on the gate, with a spiked point entering the left side of his forehead, injuring his left eyeball, and coming out through the right side of his forehead. It selectively damaged his prefrontal cortex, just as the metal tamping rod had blasted a discrete hole through Phineas Gage’s brain.

People came to the rescue. They were able to cut through the bar, with SPG conscious all the time throughout the ordeal. He even helped his rescuers to get him off the gate. As with Gage they quickly got him to medical care, delivering him to the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau in Barcelona.62 The damage to his prefrontal cortex was quite extensive, and, just like Gage, he lost vision in his left eye. Again like Gage he survived the horrific accident, and it was not long before he was back on his feet, creating a new life for himself. And yet again it truly was a new life. Just like Gage, he was impatient, restless, impulsive, and would move from one thing to another, unable to properly finish any single task.

Yet here the striking parallel ends between the American and the Spanish Phineas Gages. Despite having the usual executive dysfunction that one expects from such a head injury, and despite his impulsivity, SPG did not develop the antisocial, psychopathic personality that characterized Gage. Why not?

The answer once again lies at least in part in the environment. At the time of the accident, he was engaged to his childhood sweetheart. As they once said in Rome, amore vincit omnia—love conquers all. And over in Barcelona love helped conquer the antisocial sequelae that we might normally have expected from this dreadful prefrontal damage. SPG’s sweetheart stood by him, and three years after the horrific accident, they were married. Unlike Gage, SPG had spousal support, and his support system did not end there. For the rest of his life he was able to hold down a steady job in one location, unlike Gage, who drifted around for a significant period of his life.

How could this be possible, you may say. You are by now becoming an adroit neuropsychologist, and you know that prefrontal damage invariably leads to the inability to sustain attention, to complete a task, to shift strategies in tackling problems, and to plan ahead. This was indeed true of SPG, who showed significant impairments on frontal-lobe executive tasks. But the environment is again the answer. His parents were wealthy and owned a family firm where SPG was employed for the rest of his life. His poor executive functioning meant that he was never a particularly good worker. He could do only basic manual tasks and always had to be closely supervised and checked. Yet a job it was, and with it came security and occupational functioning.

Lady Luck was not finished with SPG. He not only had a devoted wife and caring, affluent parents to support him, but he also went on to have two loving children who were destined to play a role in his psychosocial rehabilitation. In the words of his daughter:

As a child, I realized that my father was a “protected” person. When I was young I soon saw what the “problem” was, although I had always suspected it. At 17, I became part of this protection, and I still am.63

SPG could hold his broken head high throughout his life. He was always able to bring home the bacon after his hard day’s work. He had occupational functioning. He had family functioning. He had love in his life from all quarters. As many of you likely know if you reflect on episodes in your own lives, love truly can overcome enormous adversity. For me this case highlights the critical importance of psychosocial protective factors that can guard against a life of crime in the face of horrendous prefrontal damage.

As with Gage, we see in SPG a man who was not antisocial before the accident that caused the prefrontal damage. Let’s now turn to our second chord of caution, but here our case was antisocial before the head injury.

This second case study dates from approximately 2000 and concerns a thirteen-year-old-boy from Utah who by all accounts was a bit of a Johnny-gone-rotten.64 For most of his short life, he had been rotten to the core, with a well-documented history of conduct disorder, risk-taking, hyperactivity, and attention-deficit disorder. Sadly, his parents had long since lost their parental rights, and he lived in a foster home. He was a bad kid, but bear in mind that genes and an early negative home environment likely worked against him to make him what he was.

One day the lonely lad was playing Russian roulette by himself with a .22-caliber pistol. After all, despite the natural beauty of the state, what else is there for a hyperactive, stimulation-seeking, conduct-disordered boy to do in Utah? With the pistol perched underneath his chin and the barrel pointing straight up, he pulled the trigger. The loaded chamber turned, the wheel of fortune spun, and the pistol went off. He succeeded in punching a hole right through his prefrontal cortex.

Again our case was rushed to the hospital. Yet again he miraculously survived his deadly game. The CT scan taken soon after he arrived at the hospital showed that the bullet had punched a neat hole through his brain, selectively damaging the very middle part of his prefrontal cortex in much the same way that Phineas Gage’s medial prefrontal cortex was damaged by the tamping rod. If he had wanted to selectively take out this very midline part of the medial prefrontal cortex, frankly, the poor youngster could not have done a better job.

The really unusual aspect of this case is, well, nothing. I mean, nothing really unusual happened afterward. Despite losing at Russian roulette, the boy did not have such a bad ending. His social workers, foster parents, psychologist, and all legal authorities who had been managing his case agreed that he was completely unchanged by the brain damage. He was the same unruly, conduct-disordered urchin that he always had been. But he was not worse. He did not even show any additional cognitive deficits.

As the Americans say, “What gives?” The neuropsychologist Erin Bigler, who reported this case, reasoned that the young teenager had succeeded in knocking out only the piece of his medial prefrontal cortex that was already dysfunctional, the part that had been causing the conduct disorder in the first place. This second case study highlights a truism—that prefrontal damage does not by any means always result in behavioral change in the antisocial direction, particularly if, unlike the American and Spanish Phineas Gage cases, the individual was not normal to begin with.

Our third case takes this principle to another level. It underscores the point that there can be marked differences in outcome when prefrontal damage strikes. It is yet another Gage-like accident, and, as with the Utah Russian-roulette case, we are dealing with an individual with a deeply entrenched preexisting antisocial condition. But on this occasion there is an astonishing change in behavior after the accident.

This chord of caution deals with a thirty-three-year-old man from Philadelphia who had a history replete with antisocial and aggressive behavior throughout his life—a life-course persistent offender who was pathologically aggressive. He was also depressed. In fact, he was very depressed. He decided to end his life—but in an unusual way. He took a crossbow and—in a manner remarkably reminiscent of the Russian-roulette case—he placed the bow underneath his chin, with the arrow bolt pointing straight up, and he released the trigger.

Like a tamping rod, the bolt shot right up into his prefrontal cortex, and as was the case with the Spanish Phineas Gage, the deadly projectile lodged firmly in his brain. Like the other victims we have witnessed, he was rapidly rushed to medical care. Yet again it’s a strange survival story. This unhappy and deeply troubled man was taken to my university hospital—the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania—to have the bolt extracted from his brain. It selectively damaged the medial prefrontal cortex, just as it had been with Gage and our Russian-roulette case. The missiles in all three cases had essentially the same trajectory, entering from the lower part of the head and exiting from the top of the front part of the skull.

There was a new twist in this case. As with Gage, the Philadelphian Crossbow Man was radically changed by the prefrontal damage—but in the opposite direction. Gage had been transformed from a normal man into a psychopathic-like individual. The Philadelphia Crossbow Man was instead transformed from an aggressive, irritable, emotionally labile antisocial into a quiet, docile, and content man.

The pathological aggression was eradicated overnight. The depression disappeared in a jiffy. It was a miracle cure. Indeed, the only neuropsychiatric symptom that resulted from the damage to a man who had been seriously depressed was that, in the words of his clinician, he became “inappropriately cheerful.”65 He simply cheered up.

This third case study again reveals the complexity of the relationship between brain and behavior, and highlights the striking differences in outcome that can occur as a function of damage to the prefrontal cortex. In the crossbow case, the fact that this disturbed and depressed individual became jolly after the accident is not entirely surprising. Puerile jocularity is one neurological symptom of damage to the prefrontal cortex, and this is what we see here. Indeed, puerile jocularity also characterized the Spanish Phineas Gage. Apparently, he spent a lot of time telling the same old lame jokes and being overly cheerful.66 So when at your next work party you meet that disinhibited, loquacious extravert who tells bad jokes and laughs at them like there is no tomorrow, make a neurological note to yourself and suspect either a spiked bar, a crossbow bolt—or perhaps just plain old frontal-lobe dysfunction.

Clearly we must be cautious with our prefrontal cortical explanation of crime. Prefrontal damage doesn’t always produce antisocial behavior. But let us not forget that overall there is a link between prefrontal structure and violence based on MRI and neurological studies, so we have to be equally cautious not to discount the hypothesis that prefrontal brain damage causes violence.

Let’s take this idea a step further from a developmental standpoint. Neurological studies have shown us that brain damage in childhood and adulthood can raise the odds of violence. Now we’ll use structural MRI to delineate more precisely that moment in time when something goes badly amiss in brain development—and here we must go back even beyond birth.

We saw in the Introduction that Cesare Lombroso was fascinated with the idea of a physical brain difference that marked out the born criminal. While no criminal is really “born bad,” I believe there is a “neurodevelopmental” brain abnormality in some offenders—a brain that does not grow in quite the way it should.

One indication of brain maldevelopment very early on is a neurological condition called cavum septum pellucidum. Normally everyone has two leaflets of gray and white matter fused together called the “septum pellucidum” that separate the lateral ventricles—fluid-filled spaces in the middle of the brain. You can see that black space in the normal brain in the left image of Figure 5.5, together with the white septum pellucidum line that divides the black ventricles. During fetal development there is in addition a smaller fluid-filled, cave-like gap—or “cavum”—right in between these two leaflets. You can see this black gap separating the two white leaflets of the septum pellucidum in the brain depicted in the right image of Figure 5.5. As the brain rapidly grows during the second trimester of pregnancy, the growth of your limbic and midline structures—the hippocampus, amygdala, septum, and corpus callosum—effectively press the two leaflets together until they fuse. This fusion is completed between three and six months after you are born.67 But when limbic structures do not develop normally, the cavum between the two leaflets remains—hence the term cavum septum pellucidum.

When we scanned the brains of our subjects from the temp agencies, we found that nineteen of them had cavum septum pellucidum—just like the one shown in the right image of Figure 5.5. We called these the cavum group—those with a visible marker of very early brain maldevelopment. We compared them to individuals with normal brains. Those with cavum septum pellucidum had significantly higher scores on measures of both psychopathy and antisocial personality disorder compared with controls. They also had more charges and convictions for criminal offenses.68

Figure 5.5

This research design is the “biological high risk” design. You don’t see it too often. We are taking those with the neurobiological abnormality and comparing them with those without the abnormality. But we can also slice this particular pie another way. Let’s instead start off by taking those with psychopathy, and compare them to non-antisocial controls on the degree to which they have cavum septum pellucidum. Fusion of the septi pellucidi from back to front during fetal development is partly on a continuum. It’s a bit like when you zip up your jeans—the zip might not close all the way and there is a gap left. So we can measure the extent to which the septum pellucidum is “zipped up,” so to speak.

What we find is that psychopaths have a greater degree of incomplete closure of the septum pellucidum, reflecting some amount of disruption to brain development. But it’s not just psychopathy. This is also true of those with antisocial personality disorder as well as those with criminal charges and convictions. It cuts across the whole spectrum of antisocial behaviors.

We see here in the classic clinical design—where we compare those with and without a clinical disorder—a convergence of findings that match those from the biological high-risk design. Different research designs converge on the same conclusion—there is an early neurodevelopmental basis to crime occurring even before the child is born. The evidence for a neurodevelopmental basis to criminal and psychopathic behavior is mounting.69 As much as traditional criminologists and sociologists would hate to admit it, Lombroso was partly right.

We don’t know what specific factors can account for the limbic maldevelopment that gives rise to cavum septum pellucidum. We do know, however, that maternal alcohol abuse during pregnancy plays a role.70 So while talk of a neurodevelopment abnormality sounds like genetic destiny, environmental influences like maternal alcohol abuse may be just as important.

There is an interesting twist to the link between cavum septum pellucidum and crime. In our study we found that brain maldevelopment was especially linked to features of antisocial personality related to lifelong antisocial behavior—things like a reckless disregarded for self and others, lack of remorse, and aggression. Interestingly, boxers are more likely to have cavum septum pellucidum than controls. Is that because the brain damage is caused by being biffed about in the boxing ring rather than the other way around?

Researchers think not, and instead have touted the provocative idea that those with cavum septum pellucidum are “born to box.”71 Their idea is that cavum septum pellucidum nudges the individual into developing an aggressive personality. Those with aggressive tendencies are more likely to take up boxing, making good use of their natural aggression. But could trauma and head injury in our temp workers result in cavum septum pellucidum? We controlled for these factors, as well as many psychiatric confounds, and results remained unchanged. Cavum septum pellucidum by itself predisposes people to antisocial, psychopathic, and aggressive behavior.

For some, therefore, it’s an early neurodevelopment disorder that puts their limbic system out of kilter and places them on a path to crime. Add in a degree of frontal-lobe dysfunction, and they lose full control of their basic instincts—whether it’s sex or aggression or both.

It’s worth repeating that the complexity of the brain matches the complexity of the causes of crime. When we learn more about our neurobiology in forthcoming decades, we’ll see that multiple brain systems are complicit. We have dug down from the surface of the prefrontal cortex into the very deepest chasms of the brain—the cavum septum pellucidum. To mine more knowledge on violence, let’s now move away from the very center of the brain into that dysfunctional limbic system that seems not to be developing properly in psychopaths. The key culprit dwelling in this neural neighborhood? We think it’s the amygdala.

The amygdala is an almond-shaped structure lying in a deep cortical fold inside the brain—an area called the medial surface of the temporal lobe. There is one in each hemisphere of the brain, about three-quarters of the way down from the top of the brain depicted in Figure 5.6. This part of the brain is critically involved in the generation of emotion. No brain area is more important in the minds of neuroscientists for emotion than the amygdala. Recall that one of the striking features of the psychopath is a lack of affect and emotional depth. Juxtapose this obvious clinical observation with the equally obvious role of the amygdala in the generation of fear, and you come up with a surprisingly simple hypothesis—that the amygdala is structurally abnormal in psychopaths.

Figure 5.6 Coronal slice of the brain showing the left and right amygdala toward the base of the brain

Despite its seeming simplicity, nobody had ever tested this hypothesis until my team and I scanned psychopaths and conducted a fine-grained analysis of their left and right amygdalae. In collaboration with our colleagues Art Toga and Katherine Narr at UCLA, we used state-of-the-art mapping techniques to assess the morphology of this brain area in both psychopaths and controls. Art Toga and his laboratory had developed the ability to map group differences on a pixel-by-pixel basis throughout the amygdala. Almost all functional-imaging research findings talk about the amygdala as a unitary structure—largely because the activation patterns seen are quite broad and not localized to any specific subregion. But my astute graduate student from Taiwan, Yaling Yang, reasoned that the amygdala is in reality made up of thirteen different substructures or nuclei, each with different functions. Is the amygdala deformed in psychopaths? And if so, which specific nuclei within the amygdala are compromised?

Yang found that both the right and left amygdalae are impaired in psychopaths—although the deficits are greatest on the right. Overall, there was an 18 percent reduction in the volume of the amygdala in psychopaths.72 But what specific subareas of the amygdala are structurally compromised? Yang brilliantly mapped out the corresponding amygdala nuclei. Three of the thirteen nuclei were found to be particularly deformed in psychopaths—the central, basolateral, and cortical nuclei. The specific areas of the amygdala that were deformed in psychopaths are darkly shaded in Figure 5.6. What do these three subregions of the amygdala do?

The central nucleus is strongly involved in the control of autonomic nervous system functions and is also involved in attention and vigilance.73 Not surprisingly, it plays a particularly important role in classical conditioning, and we saw earlier that fear conditioning is the key to conscience, with psychopaths and criminals having fear-conditioning deficits as well as attentional deficits. The basolateral nucleus is important in avoidance learning—learning not to do things that result in punishment.74 In this respect, recidivistic offenders just cannot learn when to give up on criminal behaviors that get them punished with imprisonment. The cortical nucleus has been shown to be involved in positive parenting behaviors, and we know what lousy parents psychopaths make. Sum up the functions of the three nuclei of the amygdala that are structurally impaired, and it’s not too surprising that psychopaths are functionally compromised in areas important for prosocial behavior.

We think that these structural impairments to the amygdala are likely to be a product of fetal neural maldevelopment. That is, we suspect that something is going very wrong with how this brain structure develops throughout early life in psychopaths. It could be the type of early “health insults” that we will discuss later—like nicotine and alcohol exposure—or some other teratogen that interferes with normal limbic development just as we have seen in cavum septum pellucidum. So it could have an environmental cause.

But it could also be genetic. Unlike the ventral prefrontal cortex and the frontal pole (the very front of the brain), which are quite susceptible to damage resulting from environmental head injuries, the amygdala, with its location deep in the brain, is not generally affected by environmental insults. We simply cannot ignore the possible role of genes in the structural deformations that we observe in psychopaths.

Could the cause of the amygdala deformations be crime and psychopathy itself? Could being cold, callous, and unemotional somehow shrink the amygdala? After all, brain imaging in adults is correlational and does not demonstrate causality. What would help us here are longitudinal brain-imaging studies scanning young children early in life and following them up into adulthood to find out if the amygdala impairment precedes the onset of antisocial behavior in late childhood.

Don’t hold your breath. These studies have not been conducted. Young children don’t sit still in scanners, and it will be a long time before imaging studies of tiny tots are able to demonstrate whether an abnormal amygdala predicts adult violence and crime. Yet the amygdala analysis in adult psychopaths sets the stage for the idea that amygdala impairments predispose people to later antisocial and psychopathic behaviors—and not the other way around.

Poor fear conditioning is a solid marker for poor amygdala functioning. As we saw in chapter 4, poor fear conditioning as early as age three predisposes someone to crime twenty years later. Yu Gao strikingly demonstrated a link between amygdala functioning in early childhood and adult crime. Causation still cannot be claimed, but the temporal ordering of this relationship has been teased out. Poor conditioning precedes crime by a long chalk. It’s about as good as it gets to demonstrating causality, and Yu Gao’s results suggested that Yaling Yang’s finding of structural amygdala deformations in psychopaths is quite likely a causal predisposition to callous, cold-hearted conduct. Students from China and Taiwan had teamed up to wage war on violence and make new scientific inroads into understanding the brain basis to crime.

Moving from the frontal control region of the brain to the deeper limbic emotional areas, we are seeing signs that something is fundamentally wrong with the brain’s anatomy in offenders. Their anatomical anomalies are not restricted to these brain regions. If we move just a bit further behind the amygdala, we come to the hippocampus, a critical region shaped like a sea horse that’s involved in a variety of functions ranging from memory to spatial ability. Here too we find a structural abnormality in psychopaths, but of an unusual kind.

We saw earlier how hippocampal functioning was impaired in offenders. That functional abnormality is likely caused by structural abnormalities that have been observed in a wide number of studies. In one group of psychopaths that we studied we found that the right hippocampus was significantly bigger than the left.75 This structural asymmetry is true in normal people too, but it is much stronger in psychopaths. Interestingly, we found this very same asymmetry in our sample of murderers, this time in terms of function.76

What causes this abnormality is not known for certain, although there are some interesting clues. If rat pups are moved around early in life into different “homes,” they develop an exaggerated hippocampal asymmetry: the right hippocampus grows to be bigger than the left.77 We found in our interviews with psychopaths that they had been bounced around from home to home much more often than controls in their first eleven years of life—more than seven different homes in psychopaths compared with three in controls.

Another factor is fetal alcohol exposure. When the brains of children suffering from fetal alcohol syndrome are scanned, it is found that the right-greater-than-left hippocampal volume that is found in normal controls is exaggerated by 80 percent.78 If you have read casebooks on killers, these two clues will be familiar to you. The early lives of violent offenders are invariably characterized by broken homes, substance-abusing and neglectful mothers, and instability. These factors taken together could be the environmental cause of the hippocampal abnormality we see in psychopaths.

Other researchers have similarly observed overall smaller hippocampal volumes in violent alcoholics.79 In psychopaths, structural depressions have been found in areas of the hippocampus that play a role in autonomic responses and fear conditioning,80 while we have similarly observed volume reductions in the hippocampus in murderers from China.81

What does the hippocampus do apart from helping you remember your boyfriend’s birthday and how to get to Walmart from the freeway exit? The hippocampus patrols the dangerous waters of emotion. For one thing, it is critically important in associating a specific place with punishment—something that helps fear conditioning.82 Just think back to where you were when a bad thing happened—that’s your hippocampus helping you remember. So, like the amygdala, it plays a key role in fear conditioning and other forms of learning that partly constitute our conscience—the guardian angel of behavior. Criminals have clear deficits in these areas. The hippocampus is also a key structure in the limbic circuit that regulates emotional behavior.83 From animal research we know that the hippocampus regulates aggression through projections to the midbrain periaqueductal gray and the perifornical lateral hypothalamus. These are deep subcortical structures that are highly important in regulating both defensive and reactive aggression as well as predatory attack.84 For example, rats with hippocampal lesions at birth show increased aggressive behavior in adulthood.85 These hippocampal abnormalities could be linked to the cavum septum pellucidum abnormality we just discussed, because the septum pellucidum forms part of the septo-hippocampal system, a brain circuit that researcher Joe Newman has argued plays a role in psychopathy.86

The hippocampus and amygdala are located in the inner side of your temporal cortex. But that’s not right in the middle of your brain. What is in the middle is the corpus callosum—a colossal body of over 200 million nerve fibers that connect your two cerebral hemispheres. These fibers—the corona radiata—radiate out from the very center of your brain to the outer areas of your cerebral hemispheres, interconnecting many different brain regions. We measured the volume of the corpus callosum and its corona radiata and found that this volume is much bigger in psychopaths with antisocial personality disorder. It was also longer. And thinner too. A long, thin body of white matter. It’s as if there is too much connectivity in the brains of psychopaths—too much cross talk between the two hemispheres.

What do we make of this? Although we often think of psychopaths as antisocial villains with a lot of negative characteristics, they’re actually a lot of fun. They have a lot of positive features, especially on the surface. In particular, many psychopaths have the gift of gab. They are very glib, very charming, very good con artists who can convince you of almost anything. Robert Hare—regarded by many as one of the world’s leading researchers on psychopathy—has demonstrated, using something called the dichotic listening task,87 that psychopaths are less “lateralized” for language.88 We found the same thing in juvenile psychopaths.89 What does this mean? In many of us, the left hemisphere is largely responsible for language processing—language is strongly lateralized to the left hemisphere. But in psychopaths it’s more of a mix of both left and right hemispheres. This might be why they seem to be so adept in their verbal skills. They have two hemispheres—not one—that they can utilize for language processing. This in turn could be due to a larger, better communicating corpus callosum.

We have to remember that psychopaths are a special group of criminal offenders and that we cannot say the same thing about run-of-the-mill violent offenders. But whichever way you look at it, psychopaths appear to be literally “wired” differently from the rest of us.

We have moved anatomically from the surface of the brain—the cortex—into the deeper brain regions—the subcortex. Now let’s continue our subterranean tour to another deep-brain region—the striatum. In evolutionary terms, this is an old brain structure involved in one basic function common across all species—reward-seeking behavior. For a long time in our laboratory we have felt that psychopathic individuals may be characterized by an oversensitivity to rewards. When there is a chance of getting the goods, they seem to go all out—even at the risk of negative consequences.

The first new study I conducted when I moved from Nottingham to Los Angeles sought to test out this idea.90 I was an assistant professor. As for all assistant professors when I started out, academic life was not that easy. I was involved in studies in England and Mauritius, but the expectation was that you should also be setting up your own laboratory and conducting work independent from other investigators in order to establish your independence. You have to show that you have what it takes to go it alone.

Easier said than done. I felt lost in L.A. I didn’t have a penny for research funds, so whatever research I did would have to be done on the cheap. One piece of luck was that I had two students who wanted to work with me during their summer alongside with Mary O’Brien, a senior professor’s graduate student who was interested in child antisocial behavior.

The next bit of luck was that there were a bunch of juvenile delinquents living just down the road from me in the Eagle Rock neighborhood of Los Angeles. I got permission from the Superior Court of California to work with them. They lived in a home as an alternative to being sentenced to a closed institution, and for these teenage boys participating in experiments with young female undergraduates from USC was not unappealing. Forty out of the forty-three kids we approached were keen to be involved in the study.

The third bit of luck was that while I had given up orange juice to save for a down payment on a home, I did have a deck of cards and some plastic poker chips. Taken together, this would be enough for my first study in L.A.

We had the mischief-makers play a game of cards that went something like this. Each card had a number on it. For half of the numbers, selecting them would result in the gain of a poker chip—so this was a reward card. Half of the cards, though, would result in a loss—a punishment card. Touching the card was a response. The subject could touch it to select it, or not touch it to pass. Over the course of sixty-four card plays, the subject had to make as much money as he could—to learn which cards were the winners. We assessed which of the delinquents were psychopaths based on staff ratings of their behavior and personality, and then we compared them to delinquents who were not psychopaths.

The results? My graduate student Angela Scarpa showed that our young psychopaths showed much greater response to the reward cards than the non-psychopaths. They were hooked on rewards, confirming previous studies showing the same in adult psychopaths.91 Our budding psychopaths actually showed better learning throughout the task too. This suggests that psychopaths can learn—as long as you use rewards to shape their behavior. It was the first time that a reputable journal had published a study on “juvenile psychopaths.”92 Until then, nobody liked the idea that adolescents might actually be psychopaths in the making.

Twenty years went by and we were still mulling over the findings. Could this behavioral difference translate to brain differences in psychopaths? My graduate student Andrea Glenn tested the idea out on our psychopaths from temp agencies.93 The striatum is a key brain region that is associated with reward-seeking and impulsive behavior. Studies have also showed that it is involved in stimulation-seeking behavior, persistently repeating actions that are related to rewards, and enhanced learning from reward stimuli.94, 95 Sounds like psychopathic behavior, doesn’t it? We found that our psychopathic individuals showed a 10 percent increase in the volume of the striatum compared with controls. Results could not be explained by group differences in age, sex, ethnicity, substance or alcohol abuse, whole brain volumes, or even socioeconomic status. They seemed pretty solid.