Henry Lee Lucas never really had a chance in life. Right from the beginning he was damaged goods. His father, an alcoholic hobo named Anderson Lucas, who lost both of his legs after falling off a freight train, whiled away his time drinking, selling pencils, and making illegal liquor. Henry himself became addicted to alcohol by the tender age of ten. Drunk most hours of the day, Anderson had no time for Henry—or anyone else, for that matter.

Henry’s mother, Viola, was an even worse parent. An alcoholic as well as a prostitute, she gave birth to Henry when she was forty, after she had already abandoned four children to foster homes. Henry; his elder brother, Andrew; his parents; and Viola’s pimp all shared the same bedroom in a dirt-floor, ramshackle cabin near Blacksburg, Virginia, without electricity or plumbing. From the time he was a small boy, Henry had to watch his mother having sex with her clients.

Chronically malnourished, Henry was forced to scavenge for food in garbage bins to stay alive. His mother would cook only for her pimp, and the children ate their scavenged food off the floor, as Viola wouldn’t wash plates. His first hot meal as a child was when he started attending school and a teacher took pity on him. That same teacher also gave him his first pair of shoes.

His mother psychologically and physically abused him. Once, when he was seven years old, he was too slow to fetch wood for the stove, so his mother hit him hard on the head with a wooden board. Such was the level of neglect that he lay where he had fallen for three full days in a semiconscious state, totally ignored by the rest of his family. Ironically, it was Bernie the pimp who eventually thought something was seriously wrong and took Henry to the hospital, telling doctors he had fallen off a ladder.1

This was likely only a fraction of the physical abuse and head trauma Henry endured. For the rest of his life he experienced blackouts, spells of dizziness, and at times felt he was floating on air. Neurological examinations and brain scans later in life revealed evidence of extensive brain pathology, very likely a result of the early maternal abuse and deprivation he had suffered.2

Henry was also subjected to sustained psychological cruelty by his mother. When he was seven she pointed out a stranger to him in town, telling him, “He’s your natural pa,” a fact later confirmed by Anderson, Henry’s supposed father.3 To have such a basic fact of life shattered like that would pull the psychological rug out from under most children’s feet, and not surprisingly Henry was devastated and in tears when hearing this news. His sister documents that his mother dressed him as a girl from the time he was a toddler up to his first day at school. His teacher, horrified by his treatment, cut his hair and got him a pair of trousers to wear.

The cruelty of his mother seemed to know no bounds. Viola once saw him enjoying playing with a pet mule. She asked him if he liked his pet mule. He said he did. So she fetched a shotgun and killed the mule in front of his eyes. As if this psychological cruelty was not sufficient to satisfy her, she proceeded to whip and beat the child because it would cost money to have the mule’s carcass carted away.4

At school Henry was continuously tormented by other children because he was very dirty and smelled terrible. His abject misery was compounded when his brother Andrew accidentally stuck a knife in his face when they were making a swing from a maple tree, puncturing his eye and impairing his peripheral vision. Bad luck morphed into extremely bad luck when a teacher at school swung her hand to hit another child in class, missed, and accidentally caught Henry in the same left eye. The accidental blow reopened the wound, resulting in the loss of his eye.5

Henry would go on to become one of the most prolific serial killers in history. He was eventually convicted of eleven homicides committed over a twenty-three-year period, from 1960 to 1983, but he was implicated in a massive 189 altogether. All his victims were female—but we’ll return to that issue later. For now his case is particularly salutary in illustrating how a toxic mix of biological and social factors can conspire to create a serial killer.6

That mix of biological and social deprivation created a surprisingly efficient killing machine, given the disadvantages Lucas was dealt in life. On the biological side there are three very important risk factors for violence that have been highlighted in previous chapters—head injury, poor nutrition, and genetic heritage from his antisocial parents. These are abetted by a host of social risk factors, including abuse, neglect, humiliation, maternal rejection, abject poverty, overcrowding, being in a bad neighborhood, induction into alcoholism, and complete absence of care and sense of belonging. It was this bitter brew—this very cruel concoction—that turned Lucas into an alcoholic killer.

Lucas’s case, while extreme, is not exactly unusual. We’ll review in this chapter the scientific evidence showing that when even mild social and biological risk factors coalesce, we can especially expect later trouble. So far we have been identifying the biological factors that go to make up the anatomy of violence. But these are just the bare bones. This chapter aims to flesh out the skeleton by outlining research showing how social factors combine—or interact—with biological risk factors to shape the violent offender.

Criminals like Lucas are a biosocial jigsaw puzzle, consisting of many different and scattered pieces. Even after identification of the biological pieces, it is a challenge to understand how they fit together with the social and psychological processes that decades of prior research have tied to violence.

From this vantage point, we will first turn our attention to understanding how social risk factors come together with biological risk factors to create violence—how they interact in a multiplicative fashion. I’ll then show you how the social environment moderates—or changes—the way that biological factors work. I call this the “social-push” hypothesis. We’ll see how genes shape the brain to promote violent behavior and yet, at the same time, how the social environment beats up the brain and reshapes gene expression. Finally, we’ll piece together the parts of the brain that we have implicated so far and map out more precisely how they collectively give rise to violence.

Henry Lucas was ten when he allegedly became addicted to alcohol. I was eleven when I became addicted to making it. I made wine out of anything I could lay my hands on—potatoes, strawberries, raspberries. Like Lucas I was a scavenger. I even made wine from the blossoms of our goldenrod plant. I bootlegged my brew to visitors and relatives. I used the profits to back horses, running the bet—supposedly from my mother—down to the corner shop, whose owner was a bookie. At fourteen I turned to making lager and I was pretty good at it, except I made the alcohol content too high and people got drunk too quickly, cutting my sales.

When I later began to study adolescent antisocial behavior instead of practicing it, what stayed with me from that extensive experience in brewing was a simple lesson: it takes a complex mix of factors to create the end product. You think of wine and you think of grapes, but of course it is much more. The fermentation of the yeast in the sun with a little bit of sugar. Squishing the fruit to make the must. Adding potassium metabisulfite to kill bacteria and wild yeast. Getting the fermentation process going. Having the acid level just right. Using a hydrometer to measure the specific gravity of the liquid to ensure that there is enough sugar for the yeast to convert it into carbon dioxide and alcohol. There’s the racking of the wine by siphoning it off the sedimentary lees at the bottom of the gallon demijohn. Most important, it’s not just the mix of ingredients but the right environment. You need precisely the right temperature for the yeast and fermentation process.

My rule-breaking behavior had no one specific cause. It had to be a biosocial brew. Like my own hooch, the offender propping up the bar constitutes a merry mix of ingredients. Yet despite enormous knowledge of social factors and some beginning knowledge of the biology of psychopathy by Robert Hare in Vancouver,7 criminologists and other scientists in the 1970s had not woken up to the idea that these two sets of risk factors interact. While I was a neophyte when I started my research career in 1977, and while I felt certain that biology was one component, I was equally convinced that the key chain needed to unlock crime held a lot of different keys—social as well as biological ones.

Unlocking crime would require understanding a complex recipe. Very little in life is simple, and wine, lager, and violence are no exceptions. So the ultimate answer had to be more than the one many sociologists were touting. Add the fact that I have always been a bit contrarian—my first research papers focused on biosocial interactions in explaining antisocial behavior,8 something radically different from the prevailing perspective in the 1970s, which was dominated by radical criminology espousing Marxist viewpoints.9

We saw earlier that birth complications—a biological factor—can predispose someone to later adult violence. The seeds of sin strike early in life with anoxia and preeclampsia damaging the developing brain. But we also discussed how this biological risk factor particularly predisposes someone to adult violence when combined with a social risk factor—maternal rejection of the child.10 We saw that these findings from Denmark were replicated in the United States, Canada, and Sweden. This was the first convincing scientific demonstration of a biological factor interacting with a social factor early in life to predispose someone to violence in adulthood. But it was not the last.

In 2002 I reviewed all research that had examined biosocial interaction effects in relation to any form of antisocial or criminal behavior. I found no fewer than thirty-nine clear, empirical examples of biosocial interactions.11 They covered the areas of genetics, psychophysiology, obstetrics, brain imaging, neuropsychology, neurology, hormones, neurotransmitters, and environmental toxins. But before we delve into examples, let me highlight one of two important themes that emerged.

The first theme is that when biological and social factors form the groups in the statistical analysis and when antisocial behavior is the outcome measure, then the presence of both risk factors exponentially increases the rates of antisocial behavior. We’ll call this the interaction hypothesis. We’ve just seen an example of this in birth complications and maternal rejection as risk factors raising the rate of violence in adulthood—the outcome measure.

Here’s another example, from the work of Sarnoff Mednick, the pioneering and brilliant researcher who was instrumental in bringing me to the United States in 1987. Mednick conducted a study of minor physical anomalies, family stability, and violence. As you may recall from chapter 6, these minor physical anomalies are markers of fetal neural maldevelopment. He found that twelve-year-old boys with more minor physical anomalies committed more violent offending in adulthood. However, when subjects from unstable, non-intact homes were compared with those from stable homes, Sarnoff found a biosocial interaction. The combination of minor physical anomalies and being raised in an unstable home environment exponentially increases the rate of convictions for adult violence at age twenty-one.12 As you can see in Figure 8.1, if you were just brought up in an unstable home environment you have a 20 percent chance of committing violence. But when minor physical anomalies are added into the mix, that rate jumps to 70 percent—a threefold increase, just as we witnessed when birth complications interact with maternal rejection. Danny Pine and David Shaffer at Columbia University observed a very similar biosocial interaction, with the combination of social adversity and minor physical anomalies tripling the rate of conduct disorder in seventeen-year-olds.13

Let’s put this piece of the jigsaw puzzle into practice in the case of a significantly violent offender. Carlton Gary, nicknamed “the Stocking Strangler,” raped and killed at least seven women aged fifty-five to ninety. His modus operandi was to break into their homes in Columbus, Georgia, beat them up, rape them, and then strangle them with a stocking or a scarf. They were all white. What turned him into a killer?

Gary was a series of contradictions. At one level, he was a handsome man who worked as a model on local television. Yet he was also a pimp and a drug pusher. While he was a caregiver for his elderly aunt by day, he also perplexingly raped and murdered equally elderly white women by night. At the same time as he was committing these murders, he was dating a female deputy sheriff.14 He was also a bit of a Houdini, a talented escape artist who sawed through the bars of his cell and broke out of a prison in Onondaga County, New York, in August 1977.15 Even though he broke his ankle in the twenty-foot fall, he made good his escape by jumping on a nearby bicycle. He eventually got a Rochester physician to put a cast on his leg, and for a while was reported to be hopping around like a duck.16 He also escaped from a South Carolina prison in 1984. He was a persistent offender who had been in trouble since he was a kid—and yet he was a creative man with a reputedly high IQ17 who often managed to escape the dragnet thrown around him. He successfully talked his way out of an early end to his killing career by accusing another man. All told, he was a bit of a conundrum. Why would a bright, creative, attractive man resort to crime as a way of life? We can discern pieces of that puzzle in his complex biosocial makeup. Here’s something of that shuffle.

Figure 8.1 Interaction between minor physical anomalies and home background in predisposing to adult violence at age twenty-one

Gary never really knew his father, having met him only once, when he was twelve. He was all but abandoned by his mother, who could not—or would not—care for him. He was bounced around from relatives to acquaintances fifteen times before his first arrest as a juvenile, and we see a clear breakage of the mother-infant bonding process that can predispose a child to become Bowlby’s affectionless psychopath.18 He was also a scrawny young street urchin who, like Henry Lucas, was so malnourished he was forced to rummage around for food in garbage bins. You now know that early malnutrition is an important risk factor for antisocial behavior. Again like Lucas, Gary was allegedly abused by both his mother and the men she lived with. At school during recess one time he was knocked unconscious and was diagnosed with minimal brain dysfunction. Again, we see parallels with Henry Lucas’s head injury. Adding to his social deprivation, he had no fewer than five minor physical anomalies, including adherent ear lobes and webbing of his fingers.19

We see in Carlton Gary several of the biosocial warning signs we’ve been discussing. Salient among these are the maternal deprivation we witnessed in the birth-complication study, the unstable home environment we saw in Mednick’s study, and the multiple minor physical anomalies that Danny Pine and others have documented.

Head injury and neurological markers of brain dysfunction are further all-too-common risk factors for violence that interact with social risk factors. My postdoctoral student Patty Brennan, now at Emory University, and I documented this in a sample of 397 twenty-three-year-olds, for which early neurological, obstetric, and neuromotor measures had been collected in the first year of life—together with family and social data collected at ages seventeen to nineteen and crime outcome data collected at ages twenty to twenty-two.20

Neurological deficits were assessed from an examination conducted in the first five days of life. The pediatrician looked for things like cyanosis (where the skin, gums, and fingernails have a bluish tint to them). When oxygenated, the blood contains a red protein—hemoglobin. When it is blue, it lacks oxygen—and low oxygen impairs brain functioning. At one year of age the babies were also assessed for signs of poor neuromotor development—such as not being able to sit up without support, not reaching for objects until eleven or twelve months, or not holding the head up until after nine months. On the social side, a psychiatric social worker interviewed the mother for measures of family instability, maternal rejection of the child, family conflict, and poverty.

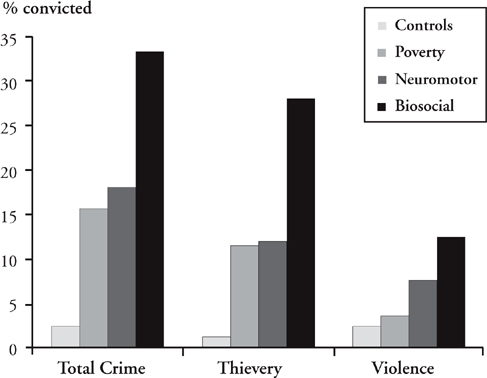

We put all these risk factors into a cluster analysis—a statistical procedure that looks objectively to see if discrete, naturally occurring groups fall out.21 They did. One group only had poverty. Another only had neuromotor dysfunction and birth complications. The third group had both biological and social risk factors.22 We also created a normal control group lacking any risk factor. We computed rates of total crime, property offending, and, more important, violent offending.

You can see the results in Figure 8.2. The rate of violence in early adulthood in the poverty-only group was 3.5 percent, compared with 12.5 percent for the biosocial group. As before, we see here more than a threefold increase. The biosocial group also had more than fourteen times the rate of total crime of the normal controls. Even though all three groups were of approximately equal size, the biosocial group accounted for 70.2 percent of all the crimes perpetrated by the entire sample.23 We clearly see here the potency of adding early neurological risk into the equation. These babies were brought into life without sin, and yet they were ushered into the vestibule of violence before they could even sit up on their own.

What we find for adult violence holds for aggressive teenagers. Patty Brennan divided adolescents from Australia into four groups. One had early social risk factors—poverty, low education, lack of parental warmth, maternal hostility and negative attitude toward the infant, lack of monitoring, and multiple changes in parents’ marital status. Another group had early biological risk factors—birth complications and neurocognitive deficits. A third group had both sets of risk factors, while a fourth group was low on all risk factors. As you can clearly see in Figure 8.3, 65 percent of the biosocial group who had both sets of risk factors had serious aggressive outcomes starting early in life compared to 25 percent of those with just the social risk, 17 percent with just the biological risk, and 12 percent of the controls.24 Again in Australia the combination of birth complications and lack of nurturance is crucial, as in other countries.

Figure 8.2 Increased criminal offending in those with both biological and social risk factors

We see the same for another very early risk factor—maternal smoking during pregnancy. Pirkko Räsänen in Finland found that prenatal smoking doubled the rate of violence in adulthood in an enormous sample of 5,636 men.25 Yet if this biological risk factor was combined with teenage pregnancy, unwanted pregnancy, and slow neuromotor development, that baby was a staggering fourteen times as likely to become a persistent adult offender.

Figure 8.3 Interaction between early biological risk factors and bad home environment in predisposing to teenage aggression in Australia

We again see the seeds of sin conspiring during infancy to create a deadly weapon in later years. Patty Brennan found a fivefold increase in adult violence when nicotine exposure was combined with exposure to delivery complications—but no increase in violence in those who were nicotine-exposed but lacking delivery complications.26 Maternal smoking also interacts with parental absence in predicting early onset of offending in the United States.27

We hear across all these studies a compelling chorus. Social factors interact with biological factors in predisposing someone to violence. As we discussed earlier, Caspi and Moffitt amazed the world in 2002 by establishing that a gene resulting in low levels of MAOA combined with severe early child abuse results in adult antisocial behavior.28 David Farrington, a world-leading criminologist at Cambridge University, found that low resting heart rate combined with parental separation before age ten resulted in voracious violent offending in adulthood.29 In the first-ever functional MRI study of any antisocial group, I found that violent offenders who suffered severe child abuse showed the greatest reduction in right temporal cortical functioning.30 Another study found that if you have high testosterone levels and a deviant peer group you may become conduct disordered—yet if you have that same high testosterone and circulate in a non-deviant peer group you are instead led to become a leader.31 Genes also combine with ghastly parenting to shape adolescent aggressive behavior.32 However you look at it, studies are showing that when biological and social factors interact, they can be far more malignant than any one factor on its own.

I mentioned earlier that there are two ways of looking at biosocial effects. One is the “interaction” perspective. I’ve given several examples above. The second approach that I describe here I call the “social-push” perspective.

Back in 1977 it was unpopular to posit a biological basis to antisocial behavior in schoolchildren. Even less accepted was the belief that biological factors combined with social factors. So when my first research publication as a young student focused on this biosocial perspective, it was a virtual no-go area. Hans Eysenck, Britain’s best-known and most controversial psychologist, had already lit a fuse with his controversial book Crime and Personality,33 in which he had the audacity to suggest that crime had a biological basis. Despite the controversy, I believed the book contained a fascinating concept that was related but different—an “antisocialization process.” This concept profoundly influenced my work.

The idea was all but lost amid the acerbic criticisms others made of the book. It appears in a section that really resonated with me. Eysenck considered a child whose mother was a prostitute and whose father was a thief—a child in “Fagin’s kitchen.” He suggested that if that child “conditioned” well or learned quickly from his antisocial home role models he would become a good pickpocket—just like the Artful Dodger in Oliver Twist. In contrast, children who do not condition well will paradoxically not be socialized so easily into an antisocial way of life.34

I had my chance to examine this idea when I first learned psychophysiological techniques in the laboratory of my PhD supervisor, Peter Venables. That was at York University in 1977. I learned the fundamentals of the eccrine sweat-gland system. I scoured the classical-conditioning literature to design a fear-conditioning experiment. I studied what types of electrodes should be used, and the chemical content required of the gel that helped the silver/silver chloride electrode to make contact with the fingers. I learned to measure bias potentials on the electrodes and to rechloride them when the bias potential was unacceptable. I worked with our technician Don Spaven on generating the auditory stimuli to play over headphones in the conditioning experiment. I tested out the decibel levels with an artificial ear and a really expensive audiometer, snapping the connector between the two and making Don very upset. But soon after that setback, I was ready to get going on recruitment.

I interviewed school headmasters, met with the teachers, and put up recruitment flyers in schools. I went knocking on the doors of parents to get permission and recruited kids into the study. I chased up those who had not responded to my recruitment letter. I then went to the schools and gave the schoolkids questionnaires to fill out to assess their antisocial personality, and to get home background information. The teachers rated their antisocial behavior. I walked to school to pick up the kids, brought them over to the lab, and walked them back again when we had finished. It was a heck of a grind. But it was my first research study, and I was enormously excited—even in the autumn rain and the winter snow. The kids felt pretty good too because they got fifty pence for taking part in the study, about a week’s pocket money back in 1978.

We discussed fear conditioning earlier, so you’ll recall that it measures anticipatory fear. The task assesses how much a kid sweats when hearing a soft tone that predicts a loud, unpleasant tone. Can they learn—like Pavlov’s dogs—to form an association between two events in time? Can they learn that certain events are followed by punishment? Do they have a “conscience”—a set of classically conditioned emotional responses—that makes them feel uncomfortable even at the thought of doing something antisocial?

I found that the environment mattered. If the schoolkids came from a good home, then those who conditioned poorly were antisocial.35 Yet if they came from a bad home, the reverse was true—those who conditioned well were the antisocial ones, Dickens’s Artful Dodgers. I was really excited because I got these same findings no matter if it was the teachers rating the antisocial behavior or if it was the child self-reporting on his or her own antisocial personality. Findings were replicating across raters who often disagreed with each other, which suggested that the results were robust. The criminologist and historian Nicole Rafter very generously attributes my first finding as a classic study that got biosocial research in criminology under way,36 but the reality is that, like many scientists, I was standing on the shoulders of giants.37

Where does this lead us? I now want to introduce you to the second biosocial theme that I developed in that review in 2002.38 So far we’ve seen that when a biological risk factor interacts with a social risk factor, the outcome is an exponential increase in violence. But “moderation” is another way that social and biological factors can influence each other. A social process can “moderate”—or change—the relationship between biology and violence. That is exactly what the conditioning experiment had demonstrated—that home background moderates the relationship between fear conditioning and antisocial behavior.

Let’s take another example, this time from the PET-scan research on murderers that we discussed earlier. I had shown that murderers in general have poor prefrontal glucose metabolism.39 In another analysis, however, I divided the murderers into those from bad homes and those from relatively normal homes. We assessed eight different forms of home deprivation—factors like child abuse, severe family conflict, and extreme poverty. To get these data we scoured criminal transcript histories, medical reports, newspaper reports, and reports from psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers. We even interviewed some of the defense attorneys. We then assigned murderers into either a “deprived” home background group or a “non-deprived” group. The question we then asked was, “Which group has the poor prefrontal functioning that predisposes them to violence?”

You can see the answer in Figure 8.4, in the color-plate section. We have here an example of a normal control on the left, who shows good prefrontal functioning—the red and yellow colors at the top. In the middle we have a murderer from a bad home background. And on the right we have a murderer from a good home. You can see that it’s the murderer from the relatively good home background who shows reduced frontal functioning—the cool colors at the top of the image. And that is the result we observed for the groups as a whole.40

The social environment moderates—or alters—the link between poor frontal functioning and murder. The bad brain–bad behavior relationship holds true for murderers from one type of home background—but not for those from a different home.

But how do we explain this? One way to think of it is like this: If you are a murderer, and you come from a bad home, what explains why you are violent? Perhaps here we don’t have to look any further than the bad home, which is a well-known social predisposition to violence.

But what if you are a murderer and you come from a good home? What causes violence here? It’s certainly not the home, because in this case it’s pretty good. Instead it has to be something else—a bad brain, perhaps. And that is indeed what we see in Figure 8.4 (in the color-plate section). Murderers from good homes had a 14.2 percent reduction in right orbitofrontal functioning—a brain area of particular relevance to violence. Accidental damage to this brain area in previously well-controlled adults is followed by personality and emotional changes that parallel criminal psychopathic behavior, or what Antonio Damasio has termed “acquired sociopathy.”41

Let’s think back to the case of Jeffrey Landrigan, which we discussed in chapter 2. He had a fabulous home background, with a loving mother, a father who was a geologist, and a sister who was as well educated and straitlaced as her parents. He had all the advantages of life. And yet Jeffrey swiftly spiraled out of control, beginning at age eleven with burglary, and eventually ending in homicide. What was the cause? Here we should suspect genetics and brain dysfunction, given that his biological father—whom he had never seen—was himself on death row for homicide. Great home—yet awful outcome. Gerald Stano was similarly adopted into a loving home six months after birth, but went on to confess to forty-one murders before facing the electric chair. Landrigan and Stano are just two among a number of serial killers reported on by Dr. Michael Stone, a forensic psychiatrist at Columbia University, who were adopted into warm, loving, and supportive home environments.42 Here we should suspect their genetic heritage, rather than bad homes, as a cause of their violence.

This social perspective on biology-violence relationships is not common in research. As we have seen, the “additive” effect of biological plus environmental risk is the prevailing outlook. And yet the alternative social-push perspective makes some sense, and I feel it can help some parents come to terms with the wayward behavior of their children.

Think about it yourself. Think about people who have a bit of the bad seed about them—a friend, a neighbor, or perhaps a family member who went off the deep end even though his or her siblings stayed on the straight and narrow. Sure, some of them come from classic chaotic homes filled with domestic violence and poverty. But don’t some of them have near-normal home backgrounds? Surprisingly loving parents? Two siblings can come from the same family—the same environment, the same upbringing—yet have different outcomes. Here I suggest that you should suspect subtle biological risk factors in nudging your acquaintance into crime, just as we have seen for murderers from good homes.

I often get e-mails from concerned parents desperately trying to help their wayward children. In one such message, a mother described how her seven-year-old son killed a household pet, struck out violently at her, and confessed to his therapist that he enjoyed choking his younger brother. When the mother became pregnant, the child began punching her in the belly and saying that he wanted the baby dead. He showed little remorse and his treatments, including counseling, medication, and hospital stays, did little to help.

Clearly this child is a serious problem, and equally clearly the mother really cares a great deal. Unlike the all-too-common scenario of parental neglect, she is desperately reaching out for help. Yet here it is the son who is callous, uncaring, and lacking remorse. Loving home—unloving child. What can account for such a tragic mismatch?

In this case it might be heritable process. Why? Because what I did not tell you earlier is that this child was adopted.

When children are adopted, it is often because the biological parents do not want their child, or their behavior is such that the child must be taken away from them. We saw earlier how maternal rejection of the child—especially in combination with biological risk factors like birth complications—is a risk factor for later violence. There is a break in the mother-infant bonding process at a critical period in the time before adoption, and it is not easy for a later loving home to mend that break. So here genetic processes may be accounting for the dangerous behavior shown in this child from a good home.

The emergence of genetic and biological factors for antisocial behavior in the midst of a benign home background is something I have termed the “social-push” hypothesis.43 Where an antisocial child lacks social factors that “push,” or predispose him to antisocial behavior, then biological factors may be the more likely explanation.44 In contrast, social causes of criminal behavior may be more important explanations of antisociality in those exposed to adverse early home conditions.45

This is not to say that antisocial children from adverse home backgrounds will never have biological risk factors for antisocial and violent behavior—they clearly will. Instead, the argument is that in such situations the link between antisocial behavior and biology is watered down because the social causes of crime can camouflage the biological contribution. Social causation will be more salient in children from adverse homes. In contrast, when the home is normal, but the child is not, then a bad brain may be the culprit. Here the social spotlight on violence is dimmed—and what now shines through is biology.46

So far I’ve illustrated the social-push hypothesis with respect to poorer frontal functioning in murderers from benign home backgrounds, and low fear conditioning in antisocial kids from poor homes. Yet this pattern of results has been found for a whole host of biological risk factors. As a graduate student I observed the social-moderation effect again soon after seeing the conditioning effect, finding that low resting heart rates particularly predispose schoolchildren from higher social class homes to antisocial behavior.47

More important, a number of other scientists have seen the same thing. Antisocial children from privileged middle-class backgrounds attending private schools in England have low resting heart rates.48 Antisocial English children from intact but not broken homes have lower heart rates.49 Low resting heart rate also characterized English criminals without a childhood history broken by parental absence and disharmony.50 In the Netherlands, Dutch “privileged” offenders—those from high-social-class homes who commit crimes of evasion—show blunted skin-conductance reactivity.51 In Mauritian children, reduced skin conductance responding to neutral tones at age three—a measure of “orienting,” or poor attention—is related to aggressive behavior at age eleven, but only in those from high-social-class backgrounds.52 Similarly in adults, English prisoners who are emotionally blunted and who come from intact homes—but not broken homes—show reduced skin-conductance orienting.53 Catherine Tuvblad, in Sweden, found that the environment moderates the link between genes and environment. As we might expect from what we learned about genetics in chapter 2, she found a genetic contribution to antisocial behavior in boys, but only those from a good home background.54

This same moderation effect has been observed at a molecular genetic level where abnormalities in genes related to the neurotransmitter dopamine55 are associated with early arrests, but only in adolescents from low-risk family environments—those who are socially better off. Again, genetic factors shine forth more in explaining antisocial behavior when social risk factors are less in evidence.

My student graduate Yu Gao also documented a moderating effect with the Iowa gambling task—a neurocognitive indicator of orbitofrontal functioning. Our colleagues Antoine Bechara and Antonio Damasio had demonstrated that patients with lesions to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex did poorly on this task and also showed psychopathic behavior.56 You’ll recall from chapter 5 that the orbitofrontal cortex is critical for generating somatic markers that inform good decision-making and that it also facilitates good fear conditioning. This task was given to schoolchildren alongside assessments of psychopathic-like behavior.57 Gao found that kids who did poorly on the orbitofrontal gambling task were more likely to be psychopaths—but only when they came from normal home backgrounds.58 Just as I’d previously shown that poor fear conditioning predisposes children from good homes to antisocial behavior, so Gao took a measure of this same orbitofrontal cortex and showed the same moderating result.59

Moving from the lab to the real world, we can see the social-push hypothesis in cases of killers. Randy Kraft, the Scorecard Killer, had a very supportive and stable home background. Similarly, Jeffrey Landrigan had the best of home environments, yet went on to become a death-row inmate. Kip Kinkel, a teenager who killed his parents as well as two children at his high school, had a caring home environment in rural Oregon. His parents were devoted professionals, and he had a loving sister. We’ll see later the orbitofrontal dysfunction that contributed to his violence. You cannot pin the blame on poverty, bad neighborhoods, or child abuse all the time—certainly not in these cases. Nor is social deprivation so obvious in many more murderers who, while not exactly having heavenly homes as kids, did have homes not much different from yours and mine.

Social factors interact with biological factors to increase a propensity for violence. They also moderate the relationship between biology and violence. There’s a third way to view the influence of the environment on biology, but before we peek into that window on the violent soul we need to step back briefly to genes, the brain, and behavior.

Figure 8.5 Genes give rise to brain abnormalities that in turn predispose to violence

We’ve already discussed brain mechanisms and the violent mind. We’ve seen how specific genes link to violence. Now we’ll survey the building site where genes provide the scaffolding to structural and functional brain abnormalities supporting the foundations of violent behavior.

You can view my blueprint in Figure 8.5. We start at the top left with genes. They link to both brain structure and influence neurotransmitter functioning (such as MAOA). Below that we have brain structure. The two bottom-up structures thought to support violence are down below in the limbic system and up top in the frontal cortex. Within each of these two broad brain regions, specific structures are identified—including the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex—that contribute to the emotional and cognitive characteristics of offenders. We then have adult violence and two important variants that predispose someone to it—antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy. Each of these two variants has different behavioral and emotional elements. Limbic structures give rise to the more affective, emotional components of violence, while frontal impairments result in the cognitive and behavioral dysfunction seen in offenders.60

How exactly do these genes produce aberrant brain conditions that predispose someone to violence? Recall the low MAOA–antisocial link. Males with this genetic makeup have an 8 percent reduction in the volume of the amygdala, the anterior cingulate, and the orbitofrontal cortex.61 We know that these brain structures are involved in emotion and are compromised in criminals. From genes to brain to offending.

Let’s take the BDNF gene as another example. BDNF—brain-derived neurotrophic factor—is a protein that promotes the survival and structure of neurons and influences dendrite growth.62 Because mutant mice bred to have reduced BDNF have a thinner cortex due to neuronal shrinkage, we know that BDNF maintains neural size and dendritic structure.63 BDNF promotes the growth and size of the hippocampus, which regulates aggression.64 BDNF also promotes cognitive functions,65 as well as fear conditioning and anxiety.66 Given that offenders have poor fear conditioning, blunted emotions, and reduced volume of prefrontal gray matter, there is no surprise that the genotype conferring low BDNF is associated with increased impulsive aggression in humans.67 Mice made deficient in BDNF become highly aggressive and prone to risk-taking, just like their human counterparts.68

Again, we go from genes to brain to aggressive behavior. While this particular subfield of neurocriminology has a very long way to go, we are starting to connect the dots—beginning with malignant genes, moving into brain impairment, and culminating in crime. Nevertheless, it’s going to be more complicated. I’m going to argue that the social environment, far from taking a backseat in this genetic and biological voyage to violence, is driving this Wild West stagecoach.

You now know that the social environment is a causal agent in the brain changes that shape violence. After all, head injury is caused by what happens to you in your social world. You fall down and your head takes a hit. You have a car crash resulting in a whiplash injury. You were shaken as a baby. Whether it is what people deliberately do to you, or life’s luckless accidents, your brain gets damaged. And it is that damage that can unleash the devil within you—the unbridled, disinhibited influences that we saw in Henry Lee Lucas, Phineas Gage, and many others.

But the environment is even more powerful in influencing the brain than you might imagine. Let me take you back to your childhood, but perhaps change things around a little. Suppose that now you are living in a neighborhood where violence is more commonplace than normal. You’re an eleven-year-old girl or boy, and coming up soon you are going to have a standardized school test on vocabulary and reading. Then, out of the blue, someone living in your immediate neighborhood is shot dead. Compared with other kids in your class who have the same smarts as you but who did not have a dead body dumped on their doorstep, you do more poorly on the test.

This is what Patrick Sharkey, a sociologist at New York University and past student of the leading criminologist Robert Sampson, observed in an innovative data analysis of more than a thousand children in the Chicago Project on Human Development.69 If a homicide took place in the child’s block four days before testing, it reduced reading scores by almost ten points—or two-thirds of a standard deviation. Similarly, it reduced vocabulary scores by half a standard deviation.70

How big are these effects? Placing them into context, the relationship between homicide exposure and reading scores is as strong as the relationship between distance above sea level and average daily temperature. It’s as strong as the effectiveness of a mammogram in detecting breast cancer.71 Similarly, the relationship found between homicide exposure and vocabulary scores matches the relationship between IQ scores and job performance.72 Put still another way, Sharkey estimated that about 15 percent of African-American children spend at least one month a year doing poorly at school purely due to homicides in their neighborhoods.73 These effects are really not trivial.

We see here that it’s not just direct social experiences like physical child abuse that can change a child’s cognitive functioning. Even in the dark shadow of social experience, something indirect in society can affect your brain. An insidious effect of social experience can profoundly change neurocognitive functioning.

What precisely is going on here in the neighborhoods of Chicago and other cities with a twinning of high homicide rates and poor school performance? Sharkey did not have any neurobiological data on the children he studied, but if he did I would expect to see subtle but meaningful changes in brain functioning in children exposed to neighborhood homicide. We know that excessive release of cortisol in response to stress is neurotoxic to pyramidal cells in the hippocampus—a brain region critical for learning and memory.74 It kills them off. It seems reasonable to hypothesize that children who hear about a homicide around the corner get scared out of their wits. Is this going to happen to their family? Can they walk to the store safely? Are they going to be next? That fear and stress can translate into temporarily impairing brain functioning and cognitive performance.

If this mechanism is meaningful, you might expect a temporal relationship between the occurrence of the homicide and the reduction in cognitive performance. Suppose you are a child who has heard that someone was killed a few blocks away from you. Would you be more stressed at school if you received that news just a few days ago—or several weeks ago? Likely you would be most affected in the first few days. That’s exactly what Pat Sharkey found. The cognitive decline was present when the homicide took place four days before the test, but not when it took place four weeks before.

What about the proximity of the homicide and your level of fear? If it took place in the block you lived in—as opposed to a more distant area of your neighborhood—wouldn’t that be a lot scarier? Might it not create a greater cognitive decline? It did. For both reading and vocabulary, homicides in the nearby block had a stronger effect on the child’s performance than homicides taking place further away in the neighborhood.

There was a further tantalizing aspect of Sharkey’s results. The cognitive decline occurred for African-American children—but not Hispanic children. Why exactly that should be is unclear, but we can hypothesize. It could be that Hispanics feel less threatened by homicides than African-Americans do. Sharkey points out that in communities where African-Americans lived, 87 percent of the victims of the homicides were African-American, whereas in the murders that affected Hispanics, only 54 percent of the victims were Hispanic.75 Therefore, a nearby homicide may weigh more heavily on the minds of African-American children, and consequently pull down their test performance more.

I would add another cultural explanation. Because Hispanic homes tend to have a more nuclear family structure and operate under higher levels of social support, there might be a greater social-buffering effect operating in Hispanic homes compared with African-American homes.76 This would attenuate the effects of the local homicide on cognitive performance. Hispanic families might protect their children from the news of homicide, or may discuss it together more as a family, emphasizing that their children are protected and safe.

Sharkey’s results are intriguing because low verbal IQ is an extremely long-standing and well-replicated correlate of crime.77 It has also been documented that African-Americans have lower verbal IQs than Caucasians,78 as well as higher homicide rates.79 Sharkey and Sampson have argued that over time, living in a disadvantaged neighborhood reduces the verbal ability of African-American children by about 4 points.80 Because a year of schooling is thought to result in IQ improvements of between 2 and 4 points,81 the 4-point drop resulting from a neighborhood homicide is the equivalent of missing a year or more of schooling. Mess up schooling, and you mess up employment prospects, and we know that after that, adult crime and violence are not far down the road.

Take this even further. If the brains of African-American children are compromised by high rates of homicide that they experience in their neighborhoods, could this result in a vicious circle of increased violence and shootings in African-American neighborhoods, in turn giving rise to further neighborhood stressors and further cognitive decline?

I know this is controversial, but it is also critically important to recognize that the social environment is far more important than many have ever imagined, and complicated in ways we’re still trying to understand.82 Jonathan Kellerman as a clinical psychologist and scientist in Los Angeles was decades ahead of his time when he published a paper in 1977 documenting how environmental manipulations can reduce oppositional and destructive behavior in a seven-year-old boy with XYY syndrome.83 The environment can overcome genetics. Believe me, this book has changed your brain structure forever. New synaptic connections have been formed throughout your brain in the amygdala, hippocampus, and frontal cortex by what I have just said. Whether you like it or not, those changes will last some time and be hard to eradicate. Social experiences change the brain, likely in all ethnic and gender groups.

We’ve seen that there is a substantial genetic component to crime and violence. Despite arguments I’ve made for a direct causal pathway from genes to brain to antisocial behavior, social processes are also critical. One such process is the lack of motherly love—and the fascinating mechanism of epigenetics.

Epigenetics refers to changes in gene expression—how genes function. We often conceive of genes as fixed and static, but they are much more changeable than commonly believed. True, the underlying structure of the DNA—the nucleotide sequence—remains relatively fixed. But the chromatin proteins that DNA wraps itself around84 may be altered by the amino acids that make up these proteins. Proteins can be turned on—or turned off—by the environment. That alters how the DNA is transcribed and how the genetic material is activated. Methylation—the chemical addition of a methyl group to cytosine, which is one of the four bases of DNA—can also increase or decrease gene expression.

How does all this occur? Through the environment—and triggered in animals by as little as a mother’s lick. The neuroscientist Michael Meaney first demonstrated that rat pups whose mothers licked and groomed them more in their first ten days of life showed changes in gene expression in the hippocampus. They also dealt better with environmental stressors.85 Indeed, the functioning of more than 900 genes is regulated by maternal licking and grooming in rats.86 Maternal separation at birth has very similar effects.87 Gene expression is thought to be especially affected during prenatal and early postnatal periods,88 and we know that these early periods are critical not just for the brain but for disruptive childhood behavior, which is a prelude to adult violence.89 Take away maternal care, and there can be profound biological and genetic effects on behavior.

Strikingly, changes in gene expression caused by the early environment appear to transfer to the next generation.90 Protein malnutrition during pregnancy doesn’t just alter gene expression in the offspring; the offspring’s offspring—the grandchildren—develop abnormal metabolism even when their own parents were fed quite normally.91 So the environment not only changes gene expression in the individual—it also has permanent effects that transmit to the next generation. The exciting concept here is that although 50 percent of the variation in antisocial behavior is genetic in origin, these genes are not fixed. Social influences result in modifications to DNA that have truly profound influences on future neuronal functioning—and hence on the future of violence.

We can place these alterations in gene expression into a much broader social context of how abuse and deprivation have foundational, long-lasting effects on the brain—over and above any epigenetic effects. Early social, emotional, and nutritional deprivation in humans has been shown to result in reduced functioning of the orbitofrontal cortex, the infralimbic prefrontal cortex, the hippocampus, the amygdala, and the lateral temporal cortex.92 It also disrupts white-matter connectivity in the brain—particularly the uncinate fasciculus, a fan-like white-matter tract that connects frontal brain regions to the amygdala and temporal brain areas to the limbic areas.93 Prolonged and chronic stress, including disrupted or poor mothering, disrupts the brain’s stress-response system. That results in excessive glucocorticoid release, a reduction in glucocorticoid receptors, an imbalance in the brain’s stress-defense mechanisms, and ultimately brain degeneration.94 Deprivation makes a big dent on the brain.

There are also vulnerable periods when stress can take a greater toll on different parts of the brain. If sexual abuse occurs early, at around ages three to five, for example, hippocampal volumes are reduced. Yet if sex abuse occurs at age fourteen to sixteen, prefrontal cortical volume is reduced instead.95 This is broadly consistent with the fact that the hippocampus reaches full maturity early in life96 and is very much affected by excessive release of cortisol in response to stress. In contrast, the prefrontal cortex develops very slowly in childhood, but grows more rapidly during the teenage years.97 All told, it’s not just that stressful rearing environments affect gene expression and neurochemical functioning—they also affect growth and connectivity of the brain.

There is, of course, much more to violence than maternal neglect. Sex abuse is almost always perpetrated by men. As we have discussed earlier, even the best of mothering sometimes cannot override a biological predisposition to violence. Fathers and friends play a role in fostering juvenile delinquency and adult violence as well. Yet it is undeniable that compassionate caregiving is critical for normative child development. When a mother’s love is morphed into spiteful hate—as it was with Henry Lucas and others like him—her kids can end up killing. In this context, mothering—and the lack of it—is giving us fascinating insights not just into the pathway to violence, but also into understanding the precise mechanisms by which maternal neglect might operate.

Let’s put these pieces into place. We’ve seen that the lives of violent offenders are replete with maternal deprivation, physical and sexual abuse, other trauma, poverty, and poor nutrition. We’ve also seen how these social impairments have their hit on specific brain areas—the orbitofrontal cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, amygdala, hippocampus, and temporal cortex—brain areas that are linked to violence. We can conclude that such social deprivation results in long-term wear and tear of the developing brain to produce adolescent angst and aggression—and, ultimately, adult violence. This truly occurs, and it’s never too late for the damage to be done. Adults who lived close to the World Trade Center buildings on September 11, 2001—and thus were exposed to very significant environmental stress—showed a reduction in hippocampal gray-matter volumes when brain-scanned three years later.98 From environment to brain—and, at least in some—to ultimate destructive violence.

In this chapter we have been piecing together social and biological processes to explain violence. But what about piecing together just the bits of the brain itself? It’s an enormously multifaceted, complex organ. We saw earlier, in chapter 5, that multiple brain regions are implicated in white-collar crime, and we know crime and violence come in all shapes and forms. No one discrete brain region or circuit will by itself account for violence.

It is tempting to focus on the prefrontal cortex, given its complexity and the wide empirical support for its involvement in crime. It is even more appealing to invoke a single brain circuit involving two or three regions to help acknowledge this complexity—such as the prefrontal cortex combined with the limbic system, as I outlined above, or the orbitofrontal cortex and its control over the amygdala.99 Yet a limitation of the approach I have taken so far is that it is overly simplistic. Violence is an enormously complex and multilayered construct. A complete understanding of its neural basis is certainly going to involve multiple distributed brain processes that in turn give rise to broad social and psychological processes that predispose someone to violence. By beginning to recognize and model this neural complexity, I believe we can gain deeper insights into the etiology of antisocial behavior.

In response to the charge of oversimplicity, here’s a functional neuroanatomical model of violence.100 Let’s take the anatomy of the brain and first describe the functions of the individual areas concerned—outlining the functional significance of the brain abnormalities we have found so far in antisocial offenders. I’m basing it largely on prior reviews of structural and functional brain-imaging research on offenders.101

In Figure 8.6, I group brain processes under three broad headings—cognitive, affective, and motor—alongside the corresponding brain regions. Brain impairments in these areas predispose someone to more complex social and behavioral outcomes that in turn predispose an individual to antisocial behavior in general and violence in particular. No direct relationships are hypothesized from brain dysfunction to antisocial behavior. Instead, the model emphasizes the translation of disrupted brain systems into relatively abstract cognitive (thinking), affective (emotional) and motor (behavioral) processes. These in turn result in more complex social outcomes that represent the more concrete and proximal risk factors for offending in general. So these brain risk factors are not conceptualized as directly causing aggressive behavior, but instead bias thoughts, feelings, and actions in an antisocial direction that then results in violence.

Let’s start on the left, with cognitive processes. Here we can see the involvement of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, the medial-polar prefrontal regions, the angular gyrus,102 and the anterior and posterior cingulate. Impairment to these regions results in poor planning and organization, impaired attention, the inability to shift response strategies,103 poor cognitive appraisal of emotion,104 poor decision-making,105 impaired self-reflection,106 and reduced capacity to adequately process rewards and punishments.107 These cognitive impairments translate into social elements that lead to crime—poor occupational and social functioning,108 noncompliance with societal rules,109 insensitivity to punishment cues that guide behavior,110 bad life decisions,111 poor cognitive control over aggressive thoughts and feelings,112 overreaction to minor irritations,113 lack of insight, and school failure.

Figure 8.6 Functional neuroanatomical model of violence highlighting cognitive, affective, and motor processes

Turning to the affective processing deficits we see outlined in the top center of Figure 8.6, the neural structures I have highlighted are the amygdala/hippocampal complex, the insula, the anterior cingulate, and the superior temporal gyrus. Impairments to these regions can result in an inability to understand the mental states of others,114 learning and memory impairments,115 lack of disgust, impaired moral decision-making,116 lack of guilt and embarrassment,117 lack of empathy,118 poor fear conditioning,119 poor emotion regulation,120 and reduction in uncomfortable emotions associated with moral transgressions.121 These affective impairments can then result in being undeterred from perpetrating gruesome acts on others,122 callous disregard for others’ feelings,123 poor conscience development,124 and being unmotivated to avoid social transgressions.125 It’s easy to see how such a set of traits may in turn raise the likelihood of violence.

At the motor level on the right-hand side of the figure, brain areas include the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, and the inferior frontal cortex. Brain impairments here result in response perseveration,126 motor impairments involving a failure to inhibit inappropriate responses,127 impulsivity,128 the failure to shift response sets and passively avoid punishment,129 and motor excess.130 In the social context of everyday life this results in the failure to invoke alternative response strategies for conflict resolution,131 the repetition of maladaptive social behavior,132 poor impulse control,133 the failure to avoid punishment, and disruptive behavior.134

We see here a flow from basic brain processes to more complex cognitive, emotional, and motor constructs that then translate to real-world practical behaviors that we know characterize violent offenders. It’s certainly not a simple model, because violence is not a simple behavior. Yet it conveys the complexity of the problem we are dealing with when we try to put just the brain pieces of the puzzle together. You can imagine the even greater complexity involved when we come to including the macro-social and psychosocial processes that interact with these brain pieces. Furthermore, while I have included multiple frontal, temporal, and parietal regions, imaging research on violence is still a fledgling field. I’ve certainly simplified it here. There are many more brain regions involved, including the septum,135 the hypothalamus,136 and the striatum,137 among many others.

You may also wonder how violence in particular arises from these cognitive, affective, and motor forces. I view violence at a dimensional, probabilistic level. The greater the number of impaired cognitive, affective, and motor neural systems, the greater the likelihood of violence as an outcome. If, for example, you make poor decisions and you don’t feel guilt and you act impulsively, then that will exponentially increase the likelihood of violence—all other things being equal.

As I hope I have clarified so far, there is not one unique cause of violence. That is why violence is so hard to fathom—and one of the reasons it’s fascinating for scientists and the public alike. That is true for the brain too. For some social scientists it’s easy to think of the brain as a big blob—and yet in reality it’s a mesmerizing mélange of diverse regions, each with intriguing basic functions that contour criminal outcomes. We can see from the brain to basic cognitive-affective-motor processes to social behaviors that raise the risk of riotous behavior that the anatomy of violence is very complex.

Biology by itself is just not sufficient. Instead, we need social risk factors to pull the trigger on an outcome of violence. Although I have here emphasized early social deprivation in the violence jigsaw puzzle, I want to leave the brain uppermost in your mind. That’s because the brain goes to the heart of this book’s argument—the seeds of sin are brain-based. Despite decades in which scientists emphasized environmental and social processes, the brain is the cardinal transgressor.

This should not be a bitter pill for either social scientists or neuroscientists to swallow. We can get to bad brains through bad genes or bad environments—or, as I have argued in this chapter, through the combination of both. As you read this, greater appreciation for the complexity of violence combined with recent advances in neuroscience are paving the way for a much more sophisticated and integrated journey toward discovering crime causation, a journey that builds on the decades of painstaking sociological and psychological research on crime that social scientists can take credit for. What were two competing perspectives should now be more sensibly viewed as complementary in explaining the causes of crime. For traditional criminologists, what was once an old foe can become a new friend in the fight against violence.

Finally, we should return to our point of departure. Henry Lee Lucas was concocted from a horrendous home brew of head injury, malnutrition, humiliation, abuse, alcoholism, abject poverty, neglect, maternal rejection, overcrowding, a bad neighborhood, a criminal household, and a total lack of love. Violent offenders in general have a history of abuse and early deprivation,138 and with some exceptions noted earlier, this history particularly characterizes the backgrounds of serial killers.139 Lucas also had structural and functional brain impairments, as revealed by MRI and EEG examinations, with the frontal poles particularly affected, along with the temporal cortex.140 Toxicology tests also revealed particularly high cadmium and lead levels, heavy metals that we have seen impair brain structure and function.141 He can be pieced together and understood from distal structural and functional brain impairments that result in the more proximal cognitive, emotional, and behavioral risk factors for violence—bad decision-making at the cognitive level, callousness at the emotional level, and disinhibition at the behavioral level. These constitute key components of the puzzle making up this multiple murderer.

One unresolved piece remains. Why were all of his victims female? Henry Lucas’s first official murder victim was his own mother, whom he killed with a knife when he was drunk. While he believed he was only slapping her with his hand, he later realized that he held a knife when he hit her neck. He was twenty-three years old, and was sentenced to twenty years in prison for second-degree murder, as she ultimately died of a heart attack.142

Almost his last victim was Becky Powell, a twelve-year-old juvenile delinquent he had met when he was forty and developed an ambiguous relationship with. At one level he was a loving surrogate father for three years, making sure she was fed, clothed, and cared for—a better parent than he had had. At another level he educated her in stealing and burglary and became her lover. During a tiff when drunk, he stabbed the teenager through the heart, again with a knife. After having sex with her dead body he cut her up into pieces, stuffed her into two pillowcases, and buried her in a shallow grave. He would visit that grave several times, talking to Becky’s remains and weeping in remorse.143 It was the only truly loving relationship he had experienced in his whole life, bringing about a radical change in Lucas, who, surprisingly, confessed to his killings soon after being arrested on a mere weapons charge.

So at opposite ends in Lucas’s life we find two love-hate female relationships, with maternal abuse as the core cause of his many killings. Consider the dreadful deprivation of his childhood and the abuse heaped upon him by his alcoholic prostitute mother. The deprivation that she likely experienced herself as a child was passed down to Henry Lee Lucas not just environmentally, not just genetically, but likely epigenetically. We’ve noted how maternal care is one important ingredient in epigenetics—in gene expression. The complete lack of maternal care likely turned off important genes in Lucas that normally inhibit violence—and turned on genes that promote it. Genetic inheritance passed from one generation to the next. Yet the social environment was truly the factor that turned Lucas into a murderous psychopath.144 His mother had all the hallmarks of a hateful psychopath, and in killing her, Henry was virtually reliving his intergenerational genetic destiny of psychopathy. As Lucas said himself, “I hated all my life. I hated everybody.”145 He especially hated his mother, and that hatred was in all likelihood turned against other women, even those like Becky Powell whom he came closest to loving.

Recall also the puzzling picture of Carlton Gary, who similarly lacked secure parental bonds and suffered significant early deprivation and malnutrition. Among other perplexing issues in this case is why a handsome African-American man with glamorous girlfriends would resort to raping women over the age of fifty-five. Unusually, all were interracial homicides. All seven of his victims were white women—and yet only 1 in 10 homicides in the United States are interracial. Could this unusual pattern of violence stem from the fact that his mother and his aunt, who also raised him, worked as housekeepers for elderly, prosperous white women? Could complaining, cantankerous white women living at a time when overt racism was more common than it is today have led to hostilities from Gary’s caregivers that were passed down to him? Or, alternatively, could Gary’s hatred for elderly white women derive from his despising a mother who scarcely existed for him—a subtle redirection of aggression, as we saw for Henry Lee Lucas? And did epigenetics play a supporting role, with deprivation altering gene expression in Lucas for a rebound back to his mother?

What could have been done to save Henry Lee Lucas from a life of serial homicide, and, ultimately, death from heart failure in prison—to say nothing of saving his innocent victims?146 Are Lucas, Gary, and others like them a lost cause right at the beginning, in early childhood? Genes and brain predispositions to violence are not immutable. As we continue to piece together the different factors, social and biological, that play a role in predisposing individuals to violence, we become better placed to develop appropriate prevention and intervention programs. And that will be the focus of our next chapter—how we might prevent people like Henry Lee Lucas and Carlton Gary from becoming killers.