the encyclopedia

of asian

vegetables

Asia encompasses diverse climates, from northern China to tropical Thailand, so it is not surprising that Asian vegetables and herbs are an extremely varied lot. For the sake of practicality, I have concentrated here on the vegetables and herbs especially identified with the cuisines of Asia. The majority of species covered are Chinese, Japanese, and Southeast Asian, but I certainly could not discuss Asia without mentioning vegetable favorites from India, Korea, and the Philippines.

Japanese cooks long for mitsuba and green daikon. Thai gardeners, to have a taste of home, must cultivate their own coriander for its roots. Chinese cooks seek out blanched Asian chives, Shanghai flat cabbage, and an amaranth called Chinese spinach. To enjoy these vegetables and herbs, they usually need to grow their own.

An Asian harvest includes: ‘Japanese Giant Red’ mustard, ‘Joi Choi,’ tatsoi, mibuna, leek flowers, and snow and ‘Sugar Snap’ peas.

Owing to space limitations, numerous vegetables such as celtuce, taro, and cucuzzi (a type of squash) are not covered here but are well worth exploring, as are other seasonings such as turmeric, galangal, and many Japanese herbs, which are not reliably available commercially as plants.

The format of the entries calls for a few words of explanation. Each vegetable is listed under its most common English name, followed by alternate common names in parentheses, the Latin name, and the Asian name(s), where pertinent. Regarding the spelling of Chinese names there is great confusion, primarily because the English words are transliterated from Chinese characters. The result is a diversity of spellings approximating the original sounds. Pac choi, for example, might also be spelled pak choy, bok choy, bok choi, and baak choi. I have chosen to use the North American spellings.

A number of seed companies carry Asian varieties of vegetables and herbs; these are listed on page 102. The largest offerings are available from Evergreen Y. H. Enterprises and Kitazawa Seed Company, which specialize in Asian vegetables.

AMARANTH

(CHINESE SPINACH; LEAF AMARANTH) AMARANTHUS TRICOLOR

(A. gangeticus, A. mangostanus)

Hindi: chaulai; Mandarin: xian cai; Cantonese: yin choi; Japanese: hi-yu-na

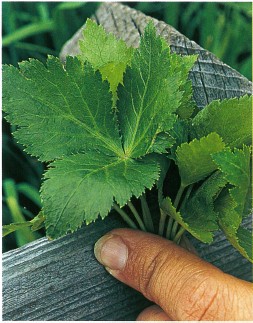

‘Merah’ amaranth

Amaranth is a New World plant that has been enjoyed for centuries in Asia, where the leaf type is preferred to the grain types. In parts of China, a variety with green and red leaves is popular; in India, cooks select the light green.

Most leaf amaranths grow to 18 inches and are best when the leaves are young and tender.

How to grow: Amaranth, a tropical annual, glories in warm weather. Start seedlings after all danger of frost has passed. Plant seeds ⅛ inch deep and 4 inches apart in full sun and rich, well-drained soil. Either grow the plants as a cut-and-come-again crop, harvested when only a few inches tall (see “The Pleasures of a Stir-fry Garden” for information on page 11) or thin the plants to 1 foot apart and grow full-sized plants. Keep amaranth fairly moist. Generally, amaranth grows with great enthusiasm. Cucumber beetles are occasionally a problem.

Harvest by hand, selecting the young, tender leaves and shoots. If growing as a cut-and-come-again crop, harvest with scissors as needed.

Varieties

Green Leaf Amaranth: 50 days; pointed, oval, dark green leaves; popular in subtropical areas

‘Merah’: 80 days; crinkled green and red leaves

‘Puteh’: 80 days, mild, light green leaves

White Leaf Amaranth: light green leaves; dwarf plants popular in Taiwan and Japan

How to prepare: Amaranth should be cooked only briefly, as it gets mushy. Popular ways to cook it are by stir-frying or adding it to soup made with pork and garlic. According to chef Ken Hom, “Westerners usually cut the stems off, but most Chinese love the texture, even though the stems are kind of stringy.” He likes amaranth simply stir-fried and flavored with fermented bean curd (also known as tempeh).

BAMBOO

Bambusa spp. (clumping bamboo) and Phyllostachys spp. (running bamboo)

Chinese: mo sun (spring shoots), jook sun (summer shoots), doeng sun (winter shoots); Japanese: takenoko; Indonesian: rebung; Malaysian: rebung; Tagalog: labong; Thai: normal; Vietnamese: mang

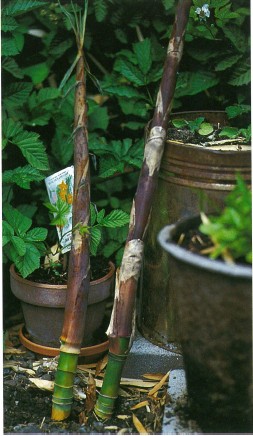

Grove of giant bamboo (below left), and narrow bamboo shoots, ready for harvest (below right)

Bamboo is one of the most useful and beloved plants in Asia. The young shoots are cooked and included in many dishes. The familiar canned product is tinny tasting and flaccid when compared to fresh shoots.

For the gardener, there are two types of bamboo: clumping and running. Running bamboo does run-it can even come up through asphalt. See the following growing instructions for how to contain running bamboo. The clumping type stays confined, sending up only basal stems.

How to grow: Bamboos are perennial grasses. Most are semihardy, but a few are hardy in the 0°F range. All species prefer well-drained, rich loam with a high organic content. In hot-summer areas, bamboo needs some shade, in cool coastal areas, full sun. During the first few years, fertilize with a balanced organic fertilizer in spring and midsummer. Thereafter, the dropped leaves and a yearly application usually suffice. Most bamboos are drought tolerant but produce the tenderest shoots when watered well. Newly established plants must not be allowed to dry out. To protect new shoots in winter, mulch well or, if bamboo is in a container, bring it into a well-lit room. Check occasionally, as bamboo litter sometimes prevents water from penetrating the root area during rain. Thin out three-year-old canes and use them for trellises, staking, and fencing. Bamboo has no major pests or diseases. To prevent bamboo itself from becoming a pest, make sure the roots of the running types are contained within a concrete or metal barrier at least 2 feet deep, or plant it in containers.

New shoots of the clumping bamboos usually appear in summer or fall, the running types in spring. Harvest the large shoots just as they emerge by freeing them from soil and, with a sturdy, sharp knife, cut off the top 6 to 8 inches. (If you make 6-inch mounds of soil around the base of the plant before the shoots emerge, they will be easier to harvest and the shoots will be longer.) The more slender species, generally referred to as summer bamboos, produce shoots 1-2 inches wide. These can be allowed to grow to a height of 12 inches before being harvested at ground level. In all cases, do not harvest all the shoots; the plants need to renew themselves.

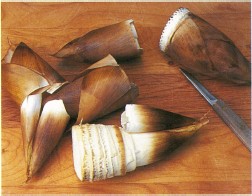

Giant bamboo shoots, peeled (above), and how to cut the small-diameter shoots (below)

Varieties

In this case, the term varieties refers to the species described in the following list. All bamboos produce shoots; a few specially recommended ones are listed below.

Upper Bank Nurseries and Bamboo Sourcery offer many types, including some of the species recommended below. Bamboos are often available locally as well.

Bambusa beecheyana (Beecheyana Bamboo): clumping type; 15 feet tall; stems 4 inches wide; hardy to USDA Zone 9; graceful form

Bambusa glaucescens (Hedge Bamboo): clumping type; 20 feet tall; 1½ inches wide; hardy to USDA Zone 8

Phyllostachys aurea (Golden Bamboo): running type; 15 feet tall; stems 2 inches wide; hardy to USDA Zone 7

P. dulce (Sweet Shoot): running type; 30 feet tall; stems 2½ inches wide; hardy to USDA Zone 8; considered the sweetest shoots

P. nuda: running type; 35 feet tall; stems 1½ inches wide; hardy to USDA Zone 5, among the hardiest types

P. heterocycla pubescens (P. edulis) (Moso): running type; 50 feet tall; stems 6 inches wide; hardy to USDA Zone 7

How to prepare: For the large, thick bamboo shoots, cut a ring around the outside of the bottom of the shoot with a knife and peel the first outer layer to expose the white flesh; repeat this procedure for a dozen or so layers until all the brown leaves are removed and the shoot is white. Then, as you would with asparagus, if the base is tough, remove that as well. Cut the shoot in very thin slices.

The small-diameter shoots must also be peeled; in this case, remove the outer layer between each joint, one joint at a time. Slice the shoots in rings and discard the woody joints.

If the shoots are sweet (which is the exception), they can be eaten raw in salads. However, most shoots are fairly tough and have a bitter taste that must be removed by parboiling for 20 minutes. Change the water after the first 10 minutes and drain the shoots when you are done parboiling. Taste the shoots and, if they are still bitter, repeat the process. After parboiling, the slices can be used in any recipe calling for bamboo shoots or frozen in plastic freezer bags.

To serve immediately, cook until tender. The most popular use of bam boo is in stir-fried dishes. Bamboo shoots are most popular in northern China, where they are used in soups, stews, dumplings, noodle and meat dishes, meat and vegetable stir-fries, and, often, with mushrooms or pickled mustard (see recipe, page 65). For example, bamboo is used in gai lon with barbecued pork (see recipe, page 72), spring rolls with Chinese chives and shredded pork, and Thai beef with bamboo shoots. In Japan, fresh bamboo shoots are occasionally grilled on skewers and glazed with soy sauce or miso, or used in braised vegetable dishes. Of course, they can be used in any recipe calling for canned shoots.

BASILS

THAI BASIL

Ocimum basilicum

Thai: bai horapa; Vietnamese: rau que

LEMON BASIL

O. citriodorum

Thai: bai manglak

HOLY BASIL

O. sanctum

Hindi: tulsi; Thai: bai gaprow

‘Siam Queen’ (above); Holy basil (left); Lemon basil (right)

Three Asian basils are prominent ingredients in the cuisines of Southeast Asia. Red-stemmed Thai basil is relatively similar in taste and appearance to Italian sweet basil, but with an anise flavor. Small-leafed lemon basil has a delicate citrus scent and taste. Purple-tinged holy basil, with slightly serrated leaves, has a strong scent of cloves and a musky taste. Holy basil is so named because it is sacred to the Hindu gods and is found planted near temples and homes in India.

How to grow: Basils are annuals that glory in hot weather and wither in the frost. Gardeners in cool-summer areas struggle to keep them going. Choose a well-drained area of the garden in full sun or light shade, and with fertile organic soil.

You can start basil seeds inside a month before planting them out, or purchase them as transplants from specialty nurseries in the spring. Basil put out in the garden before the weather is warm suffers badly. Space seedlings 1 foot apart. Keep the plants fairly moist during the growing season. Feed basil with fish emulsion every 6 weeks and after a large harvest.

Harvest basil leaves about 80 days from sowing by picking or cutting. Keep the flower heads continually cut back or the plant will go to seed.

Varieties

Seeds of Thai, lemon, and holy basil can be purchased from the herb catalogs listed in Resources. ‘Siam Queen’ is a new variety of Thai basil that is compact and tasty.

How to prepare: Thai basil is excellent in Southeast Asian curries of vegetables, chicken, and game (see recipe, page 86). Both Thai basil and lemon basil are excellent for flavoring soups and added fresh to salads. The seeds of lemon basil are used in sweet drinks and mixed with coconut milk to make a dessert. Soaked in drinks, these seeds become slippery, yet crunchy. In Vietnam and Thailand, lemon and Thai basils are combined on a platter with fresh mints, Vietnamese coriander or cilantro, and lettuce to put in spring rolls, which are served with a spicy dip (see recipe, page 78.)

Holy basil is almost always used in noodle dishes paired with chicken or shellfish. Use this basil according to taste, for its flavor intensifies in cooking.

BEANS

ADZUKI (RED BEAN)

Vigna angularis

Mandarin: hong xiao dou, chi dou; Japanese: azuki

MUNG (GREEN BEAN)

V. radiata

Chinese: look dow

SOY (SOYA BEAN, SOYBEAN)

Glycine max

Mandarin: da dou; Cantonese: tai tau, wong tau, hak tau; Japanese: daizu, eda mame

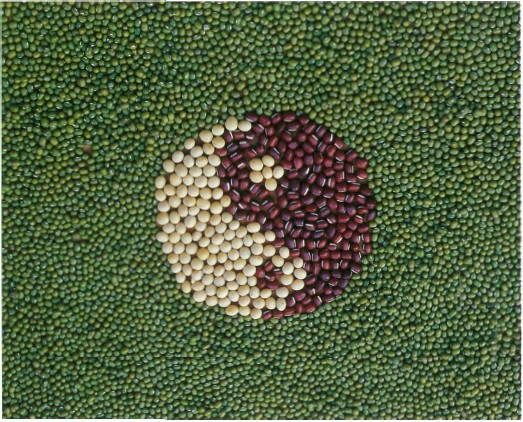

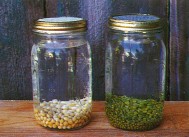

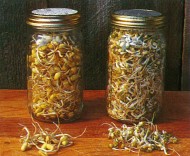

A layout of green mung, white soy, and red adzuki beans.

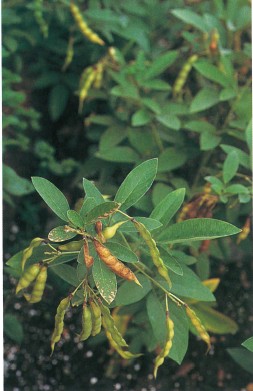

Adzuki beans are popular in Japan. The pods, which grow to about 4 inches, contain reddish seeds; the flowers are rose colored. Mung beans have purplish yellow flowers, hairy pods that grow to about 4 inches, and green seeds. Both are bushy plants that reach about 3 feet tall. Soybeans are a powerhouse of nutrition and the major source of protein for many Asians. The white- and black-seeded ones are generally used as dry beans, the green-seeded ones for fresh eating. Soybean plants have fuzzy leaves, stems, and pods and grow to about 2 feet. The tiny flowers are white or lilac.

How to grow: Soy, adzuki, and mung beans are all annuals, grown much as you would regular bush beans. Plant after all danger of frost is past and the soil has warmed to at least 60°F. Plant in full sun in a well-drained garden loam. Sow seeds 1 inch deep in rows 24 inches apart. Thin seedlings to 4 inches apart. (Wider spacing is needed for soybeans in southern areas.) Once established, water deeply and infrequently. If the plants look pale at midseason, fertilize with fish emulsion.

The Mexican bean beetle can be a pest in certain areas. Phytophthora can be a problem for soybeans, especially in overly moist soil.

You can eat the immature pods of both adzuki and mung beans or let them mature and use the beans fresh shelled or dried. Harvest soybeans for fresh shelling when the pods are plump but still green or let them dry before harvesting. If letting the beans dry on the plant, harvest after the plant turns brown. Pull up the whole plant and hang to dry completely in a warm, dry place. Shell the beans and store them in airtight containers in a cool, dry place.

Varieties

Mung and Adzuki Varieties

Mung and adzuki beans are usually not available as named varieties. Vermont Bean Seed Company and Evergreen Y. H. Enterprises carry them.

Adzuki: 60 days pods, 90 days mature seeds; high yields; pods contain 7-10 beans

Mung: 90 days mature; pods contain 7-9 beans; use for plants or sprouting if not treated with fungicides

Soybean Varieties

Johnny’s Select Seeds, Evergreen Y. H. Enterprises, and Kitazawa Seed Company carry a few varieties.

‘Butterbeans’: 90 days, fresh; green beans, buttery flavor; high yields, good fresh

‘Envy’: 75 days, fresh; very early, short-season favorite; green beans good fresh or dried

Soy, Verde: 98 days; not for northern climates; very nutty flavor; 3-foot bushes with pea-sized green beans

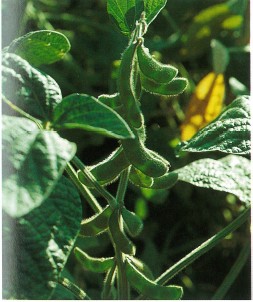

Soybean plants (above); soybeans (below)

[How to Sprout Mung and Soybeans]

It is amazingly easy to sprout bean seeds, which can be a fun project for children. Purchase seeds in bulk from an Asian grocery or a health-food store, or order sprouting seeds from a mail-order nursery. When obtaining them from a nursery, make sure the seeds have not been treated with a fungicide that is applied to aid sprouting in cold soils.

Of the several ways to sprout beans, the easiest is to put ½ cup of seeds in a clean 1-quart widemouthed mason jar and cover the top of the jar with cheesecloth tied with string. Soak the bean seeds in water overnight and drain them the next morning. Put the jar in a cool, dark place, like a closet, to sprout. Rinse the seeds with cold water 2 to 3 times a day to cool the growing sprouts and provide moisture (more often in warm weather). Drain them well each time. Repeat the process for 4 or 5 days or until the seeds have sprouted and are about 1½ inches long. Once the sprouts are ready, rinse them well to remove most of the hulls and refrigerate them. The sprouts deteriorate quickly and are best used within a day. Your mung and soy sprouts will be curlier and a little smaller than those grown commercially, but they taste the same. One word of caution: Soybean sprouts need to be cooked before they are eaten.

How to prepare: Green soybeans can be cooked in numerous ways when fresh or allowed to mature and used as dry beans. Add raw fresh beans to raw rice and cook them together, as they cook up at the same rate.

The great majority of white soybeans in Asia are made into soy products or consumed as sprouts. The latter use is particularly prevalent in Cantonese dishes, where they are stir-fried or used in soups. In Korea, the sprouts are used for salads (see recipe, page 78), and in a stew with pork.

(Caution: Soy sprouts are not edible in their raw state and are always eaten cooked.) The Japanese enjoy the fresh green soybeans in a traditional fall snack (edamame) consumed with beer. The beans, pod and all (sometimes still on the stalk), are boiled in salted water and drained; then snackers shell their own, as we do peanuts in the shell (see recipe, page 82). In Japan, the beans are sometimes shelled and added raw to rice before it is cooked (see recipe, page 66).

Adzuki are widely used in Asia for soups, but especially in desserts, and in a sweet paste for dumplings. The young pods are eaten like snow peas.

Mung bean sprouts are one of the most widely used vegetables in stir-fries in general, in various classic Asian stir-fries with pork, and in sweet-and-sour soup.

BEANS, FAVA

(BROAD BEANS)

Vicia faba

Chinese: tsaam dou; Hindi: bakla; Japanese: sora mame

BEANS, YARD-LONG (ASPARAGUS BEAN; CHINESE PEA)

Vigna unguiculata spp. Sesquipedalis

Cantonese: cheung kong tau; Mandarin: chang dou; Japanese: sasage

PIGEON PEAS (RED GRAM, DAHL)

Cajanus cajan

Fava bean flowers (above), fava bean pods (below)

Favas are cool-season beans, good for cool climates. On the other hand, yard-long beans and pigeon peas are best grown in warm climates.

Yard-long beans produce very long, thin pods. These vining plants, which are related to black-eyed peas, grow to 10 feet. The young pods, seeds, and leaves are edible. The pod and foliage flavor is mild and sweet. There are three types of yard-long beans: the dark, thin pods with black seeds; the larger, light green one with spongy pods and red seeds; and a white-seeded type.

Pigeon peas are shrubby perennials from Asia and Africa that are popular in east Indian cuisine. The quick-growing plants can be 9 feet tall and 6 feet wide.

How to grow: In areas where winters don’t dip below the teens, plant fava beans in the fall. They need about 90 days of cool weather and tolerate repeated frosts. In cold-winter areas, plant favas when you plant peas. To plant, prepare the soil well and plant seeds 2 inches deep and about 3 inches apart. The plants grow quickly to 5 feet in height. Support the tall plants with stakes and strings surrounding the outsides of the beds. Black aphids sometimes infest fava beans; control them with sprays of water. Slugs can destroy seedling beds. For young, tender fava beans whose skins do not need to be removed, harvest them when they first start to fill out the pods. Alternately, let the fava beans mature and use them fresh or dried.

Yard-long beans are hot-weather annuals that produce poorly in cool-summer areas. Plant them in full sun at least 2 weeks after your last expected frost, sowing the seeds 1 inch deep and 4 inches apart. Thin the seedlings to 8 inches. Make successive plantings 3 weeks apart. Yard-long beans need trellising and produce best if kept fairly moist. Fertilize sparingly—too much nitrogen results in few beans. Pest and disease problems are minimal. Harvest when pods reach 12 to 18 inches, before the seeds fill out the pods.

Pigeon peas are tender tropical shrubs that need a very long, warm growing season. They tolerate poor soils. Plant ½ inch deep and 5 feet apart. The plants may need support. In Florida, the plants produce for up to 5 years if there are no freezes. Harvest pods while young or let them mature and harvest the seeds for drying.

Varieties

Fava Beans

‘Nintoku Giant’: three large green seeds per pod; grows well in warmer climates

‘Windsor’: 80 days; bush; grows to 4 feet with green pods to 10 inches; large, light green beans

Yard-Long Beans

Redwood City Seed and Evergreen Y. H. Enterprises both carry yard-long beans.

Red Seeded: 75 days; heirloom; light green pods; maroon brown seeds; trouble-free variety

Black Seeded: the most widely grown yard-long; dark green pods

Black Stripe Seed: new variety from Taiwan; high yields; pods are crisp

‘Kaohsiung’: dark green, thick, meaty pods and black seeds

‘Sabah Snake’: 80 days; very long pods; pods are light green and wrinkled; white seeds; heirloom; popular in Malaysia

Pigeon Peas

ECHO and The Banana Tree carry pigeon pea seeds.

Yard-long beans (above), pigeon peas (below)

How to prepare: Young fava beans have a special sweetness. These tasty beans are shelled when the seeds start to fill out the pods. Then the bean skins must be peeled before preparation—double peeling—a real labor of love. In northern China, the beans are paired with ham or sprouted and cooked. In parts of China and Japan, mature fresh fava beans are parboiled, then stir-fried in a little oil and garlic. Diners eat them as a snack, peeling the skins off themselves.

Caution: Some males of Mediterranean descent are allergic to favas and should be wary when trying them for the first time; persons taking antidepressants with monoamine inhibitors should avoid them at all costs.

Yard-long beans are actually tastiest when 12-18 inches long. In a popular Szechwan dish called dry-fried beans, the red-seeded yard-long beans are deep-fried, drained, and then put in a wok and stir-fried with spicy seasonings. The dark green variety is best in a simple stir-fry with a bit of ginger. Try them in rolls of marinated beef or pork (see recipe, page 81) or add them to soups. These beans are pencil-thin and a bit like French haricots verts; they can be used in place of string beans in most recipes.

The young pods of pigeon peas are eaten cooked, or the fresh or dried seed is cooked and eaten, often with rice. In the Philippines, pigeon peas are often used in soups (see recipe, page 74.)

BITTER MELON

(BITTER GOURD; BITTER CUCUMBER; BALSAM PEAR)

Momordica charantia

Cantonese: fu kwa; Mandarin:ku gwa; Japanese: niga uri; Hindi: Karela

Bitter melon

Bitter melons are warty vegetables that somewhat resemble their cousins the cucumber and have a distinctive, quininelike taste. They are popular in Asia where bitter tastes are appreciated. In the Philippines, the juice from a bitter melon is sometimes rubbed on babies’ lips to accustom children to bitter tastes. The immature leaves and shoots are edible, too.

Bitter melon plants are handsome vines that bear yellow flowers and may climb more than 12 feet. The unique fruits may be light or dark green, or white when young; they mature to red orange.

How to grow: Bitter melons are grown as annuals. They need long, warm growing conditions. Soak the seeds for 24 hours before planting to help germination. Start bitter melons inside at a minimum soil temperature of 64°F. Once in the garden, they need full sun and a fertile, organic soil.

Space or thin plants to 2 feet apart. Put a trellis in place for them to grow on when you plant them. Bitter melons require ample water.

If the vines are pale at midseason, apply fish emulsion. If the plants are not setting fruit, you need to hand pollinate the flowers. Slugs and snails can be a problem for young plants.

Harvest bitter melons while they are young and still firm, in the white or green stage. They grow more bitter as they mature. Harvest regularly and do not let them ripen on the vine; they will continue to ripen after harvesting. Harvest leaves and shoots for cooking while they are young.

Varieties

In some sources, bitter melons are listed only by the common or species names rather than by variety names.

‘High Moon’: 90 days; pale green to white; to 10 inches long. Available from Territorial Seed Company

‘Hong Kong’: dark green, rather smooth skin; spindle shaped; more bitter and flavorful than most; Cantonese use this for stuffing

‘Karela’: 55 days; dark green, to 7½ inches long; very productive; from India; carried by Willhite Seed Company

‘Taiwan Large’: large, high-quality fruits, green skin and white flesh; disease resistant; popular in Taiwan

‘Thailand’: small fruits with blistered deep green skin; productive; popular in tropics

How to prepare: In much of Asia, bitter melon is considered to have coming or medicinal properties, and the young tendrils are considered a delica and are prepared by quick frying. Alternately, they are incorporated at the last minute into simple egg dishes The tendrils have some bitterness bu possess a distinctive, quite pleasant vegetable taste. The taste of the fruit varies in flavor and bitterness depend ing on maturity. Most fruits begin de green and mild and grow increasing yellow and bitter with age. Try young melons in soups and mature ones in stir-fries (see the recipe on page 70) or stuffed with meat. In China, bitter melon is usually cooked in a soup wi pork and black beans or added to stir fries. In India, bitter melon is often cooked with potatoes and numerous spices or pickled with garlic; it is also fried, stuffed, and used in curries. Before cooking with bitter melon, to remove much of the water and some the bitterness, slice, salt, and then squeeze the juice out.

BUNCHING ONIONS

(GREEN ONIONS, SCALLIONS, MULTIPLIER ONIONS, WELSH ONIONS)

Allium fistulosum

Cantonese: ts’ung fa; Mandarin: cong (onion), quing cong; Japanese: negi

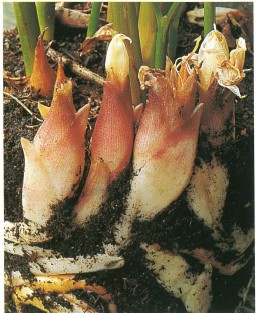

Multistemmed bunching onions

Bunching onions are bulbless onions widely used throughout Asia. They are hardy perennials and are cultivated for their long, white stems and green leaves. There are two basic types: those that grow as single-stemmed onions and those that are multistemmed and grow in clusters. The single-stemmed types are grown as annuals and can be planted quite close together. The clustering types continue to spread from year to year.

How to grow: As with other alliums, bunching onions prefer cool weather and soil rich in organic matter and phosphorous. Plant bunching onions from seed in the spring for summer use or in the fall to overwinter. Sow ¼ inch apart and ½ inch deep. Keep weeded. Give consistent moisture. The clustering types should reach a good size the first year, with some division at the base; they can be divided the second summer. To produce whiter stalks, mound the soil to blanch the stems. The long, single-stalked types are particularly well-suited for blanching and are sometimes called Chinese leeks. Bunching onions are fairly resistant to pests and disease.

Harvest the leaves when young, as you would chives. Once the plants are established, harvest the individual scallions or separate from the cluster as needed.

Varieties

‘Evergreen Hardy’ (‘Evergreen’): 65 days; very popular; grows in clusters; most cold hardy of the bunching onions

‘Kujo’ (‘Kujo Green Multistalk’): a multiplier onion; grows in clusters of 3 or 4 stalks; tender white stalks are about 10 inches long; light green leaves to 18 inches

‘Ishikura No. 2’: a popular single-stalked variety; very uniform

‘White Lisbon’: 60 days; an Allium cepa developed for use as a scallion; tender green tops and long white stems; does well in a variety of soils

How to prepare: Bunching onions can become bitter if overcooked, so they are generally chopped and added to cooked dishes toward the end of cooking. In China, these green onions are used as garnishes or added to rice, noodle, and fish dishes as well as soups and stir-fries. Historically, the nomadic tribes of Mongolia gathered the wild green onions that grew profusely in that region. They then quickly fried thin strips of beef and added handfuls of the onions at the last minute, the object being to cook the green onions lightly while still keeping the life in them. In Japanese cooking, these onion-family vegetables are widely used for pickling, in soups and garnishes, and are popular in sukiyaki.

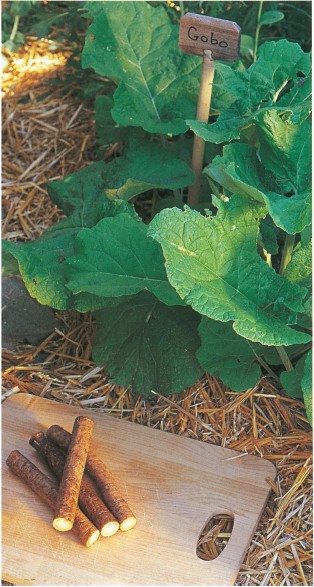

BURDOCK

Arctium lappa

Cantonese: ngao pong; Mandarin: niu pang; Japanese: gobo

Burdock

This plant’s roots, which can grow to 4 feet long and 1 inch wide, and its young shoots are prized in Japan. The roots are usually brown-skinned with white flesh. The plant grows to about 3 feet tall.

How to grow: Burdock is a biennial but is usually grown as an annual sown in early spring. It can also be sown in the fall and harvested in early spring. Soak the seeds overnight in warm water and then plant in extremely soft, deep, rich soil in full sun. Work in bone meal before planting. Thin seedlings to 8 inches apart. Keep mulched for vigorous growth throughout the season. Harvest the roots in approximately 4 months. The roots are tenderest when harvested while young, at 12 to 18 inches long. The best way to harvest is to use a post-hole digger next to the plant to expose the majority of the root before you pull it out; otherwise the root breaks off easily.

Varieties

‘Takinogawa’: 120 days; the standard Japanese variety; has well-formed roots with a mild, bittersweet flavor

How to prepare: The primary edible part of burdock is the root, but young, tender shoots are sometimes used too. The roots are sometimes used in stir-fries and soups in China. In Japan, they are pickled or cooked in soups, tempura, and stir-fries with slivered carrots. Try them rolled in thin strips of beef or pork mixed with other vegetables (see recipe, page 81). Roots are harvested and scraped before cooking; stronger-tasting roots are thinly sliced and soaked in water for several hours to remove bitterness. Keep cut roots in water to prevent darkening.

CARROTS

Daucus carota var. sativus

Hindi: gajar

Japanese carrots

Carrots are popular in India, but plant breeders in Japan and Taiwan have developed many great modern varieties we use in the West. A number of the Asian carrots are high in anthocyanins, which gives them a reddish cast.

How to grow: Plant carrots in early spring, as soon as your soil has warmed, or plant them as a fall crop. Cultivate and loosen the soil 1 foot deep to make room for the roots. Light soils are best—gardeners with heavy soils need stubby varieties. Sow seeds ½ inch apart in rows or wide beds and keep the seed bed evenly moist. Thin to 2 inches. In most parts of the country, once sprouted, carrots are easy to grow. When the plants are about 3 inches tall, mulch with compost and side dress with fish emulsion.

Once the seedlings are up, protect them from snails and slugs. In the upper Midwest, the carrot rust fly maggot tunnels its way through carrots. Floating row covers and crop rotation help. Alternaria blight and cercospora blight are possible diseases.

Carrot varieties are ready for harvesting when they are at least ½ inch across and start to color. The optimal time to harvest carrots is within a month after they mature, less in very warm weather. Harvest when the soil is moist. To prolong the fall harvest in cold climates, mulch plants well with 1 foot of dry straw and cover with plastic that’s weighted down with something heavy.

Varieties

‘Carrot Suko’(Baby Carrot): 70 days; very sweet; bred for growing as baby carrots 3 to 4 inches long

‘Dragon’: 75 days; red to purplish exterior, yellow to orange interior; sweet, spicy flavor.; the purplish exterior is high in anthocyanin; available from Garden City

‘Kinko’: 52 days; very early; 4 to 6 inches long, sweet Japanese carrot; best harvested young

‘Kuroda’: 90 days; heat tolerant; tender and sweet; 6 to 8 inches long; stores well

‘Tokita’s Scarlet’: 100 days; very sweet; heat resistant, 7 inches long; Japanese

How to prepare: Carrots find their way into numerous dishes in India, including many curries, and they are made into pickles and sweetmeats. The red varieties are more favored in China and are consumed most heavily around the Chinese New Year. Grated carrots are added to a popular Vietnamese salad dressing that includes lemon juice and fish sauce. Koreans add them to kim chee and, traditionally, daikon pickles (see recipe, page 63). In much of Southeast Asia, carrots are carved and used for a garnish.

CHINESE BROCCOLI

(CHINESE KALE)

Brassica oleracea var. alboglabra

Cantonese: kaai laan tsoi; Mandarin: gai lan

Chinese broccoli

Considered by many to be one of the choicest cabbage-family greens, Chinese broccoli, also sold as gai lon, grows rapidly to 18 inches and has blue green leaves, thick stems, and white flowers. While not really a broccoli (it’s a kale), the plant is allowed to form buds before it’s eaten, so cooks treat it as a broccoli.

How to grow: Chinese broccoli is easier to grow than most of the cabbage family. Sow seed outside in full sun in spring and again in late summer. In cool summer areas, it will produce over the summer. In mild-winter areas, it grows well as a winter crop if frosts are light. The season can be extended by starting some seeds inside in early spring and by protecting late crops from hard frost. Plant seeds ¼ inch deep in an organic, fertile soil. Thin to about 8 inches apart and keep well watered. The plants need to grow quickly to be tender and mild. Chinese broccoli is fairly pest and disease free, though it can be affected by common cabbage-family problems.

Harvest the flowering stalks just before the buds start to open. Cut the stalks 6 to 8 inches from the top of the plant to force new side growth.

Varieties

‘Blue Star’: popular in U.S. Chinatowns; the large stems and flower buds are crisp and tender

‘Green Delight’: slightly smaller than ‘Blue Star’; grows well in mild or warm climates

‘Green Lance’: 50 days; disease resistant

How to prepare: To prepare the stalks for cooking, first peel the stems as you would asparagus, removing any tough skin. Large leaves are tough also; remove these, leaving succulent stems with a small flowering top. Cut these into pieces about 2 to 3 inches long, ready for cooking. While Chinese broccoli is enjoyed in soups with noodles, mushrooms, and pork, squid, or chicken, stir-frying is the most popular way to prepare it. Try it with barbecued pork (see recipe, page 72).

CHINESE CABBAGE

Brassica rapa var. pekinensis

Mandarin: da bai cai; Cantonese: bok choi; Japanese: nappa

‘Michihili’ Chinese cabbage

Chinese cabbages have milder flavor and tenderer leaves than their cousins, the Western cabbages (which are sometimes grown in the Orient). There are three major types of Chinese cabbages: one is barrel-shaped, light green, and often referred to as napa cabbage; another is tall and cylindrical, with lacy Savoy-type leaves, sometimes referred to as Michihili cabbage; the third is an attractive, loose-headed cabbage.

How to grow: Chinese cabbages can be fussy. They don’t transplant well and tend to bolt if disturbed or if subjected to cold temperatures while young. Growing them for fall harvest reduces disease and insect problems and decreases the tendency to bolt. Start them from seeds planted directly in the garden about midsummer (2½ to 3 months before your first fall frost) so they mature in the cool weather. A few varieties, designated as spring or slow bolting, can be planted in the spring and harvested in early summer.

Young Chinese cabbage with pine needle mulch

Cabbages need a fertile, loamy soil filled with organic matter. They prefer full sun, or light shade in hot climates. Sow the seeds ½ inch deep; thin to 12 inches apart. Cabbages are heavy feeders, so add a balanced organic fertilizer: 1 cup worked into the soil around each plant at planting time. Chinese cabbages are shallow rooted and need regular and even watering and a substantial mulch to retain moisture.

Chinese cabbages are susceptible to many pests and diseases. I find the napa types and the pale-leafed varieties seem to get more than their share. Flea beetles, imported cabbageworm, and cutworms may be problems. The maggot of the cabbage root fly and aphids are other possible pests. Clubroot is one of the most serious fungus diseases of the cabbage family. Good garden hygiene is imperative. Rotate members of the cabbage family with other vegetable families. Select varieties that are resistant to cabbage diseases. Use floating row covers to protect cabbages from pests.

Harvest Chinese cabbages once the heads feel firm. In the fall, they can tolerate light frost; if a hard freeze is expected, harvest the heading cabbages and store them in a cool place.

Varieties

If direct seeding, as advised, add 2 weeks to the following days-to-maturity numbers.

‘Jade Pagoda’: 72 days; hybrid; popular Michihili type; 16 inches tall by 6 inches wide; medium green; vigorous; slow bolting

‘Lettucy Type’: 45 days; tall, open top, 12 inches tall; tender, ruffly leaves; sow late spring through late summer; bolts in cold spring weather

‘Michihili’: 78 days; open pollinated; cylindrical head 16 inches tall by inches wide; green leaves; for mild climates

‘Spring A-1’ (Takii’s Spring A-1’): 73 days; a bolt resistant, mild, sweet, light green cabbage with 3-pound heads; for spring sowing

‘Wong Bok’: 90 days; napa type; heads 10 inches tall, 6 inches across; tender; sow in early summer for fall harvest

How to prepare: Cabbage is a staple in much of Asia. In China, these cabbages are most commonly prepared with meat in soups and stir-fries. They absorb flavors well and are often combined with oyster sauce and black bean sauce, garlic, and seafood to be used as a stuffing for potstickers and spring rolls. As for preserving cabbages, there are many techniques. In China, the cabbages are often dried in the sun and used in soups in the winter. Most types are also pickled in brine, brine vinegar, or salt and hot peppers in some areas and served as a condiment or added to meat or tofu stir-fries. See the pickled mustard recipe on page 65 for pickling methods. In Korea, pickled cabbages are the basis for most kim chee, a vegetable pickle seasoned with garlic, lots of red peppers, and ginger; it is the national dish. Japanese cooks use Chinese cabbage in soups; in sukiyaki, where it is braised with meat; in shabu-shabu, a one-pot meal cooked at the table; and pickled.

CHINESE CELERY

Apium graveolens

Mandarin: quing cai; Cantonese: k’an tsoi; Japanese: seri-na; Thai: kin chai

‘Chinese Golden’ celery

Chinese celery is a close relative of the celery commonly enjoyed in the West. It has thin, hollow stems and is a smaller, hardier plant than the more familiar variety.

How to grow: Like its Western relative, Chinese celery is a biennial grown as a cool-season annual. Chinese celery grows best as a spring or fall crop. It needs full sun (or partial shade in hot areas) and a highly organic, fertile soil that retains moisture well. Start seeds indoors 8 weeks before planting outdoors. After the weather has warmed, move seedlings into the garden and place them 1 foot apart. Seeds can also be started outside in the seed bed. Fertilize the plants with liquid fish emulsion every month and keep the soil continually moist.

As a rule, Chinese celery is subject to few pests and diseases, though leaf miners can cause problems.

Some gardeners elect to garden blanch their celery. This produces stalks with a more delicate flavor. To blanch: After the plants start to mature, exclude light for about 3 weeks by wrapping the stalks with burlap or straw; surround the bundles with black plastic and tie them with string.

Harvest stems when they are about 10 inches high. New stalks will continue to form. Alternately, harvest the whole head by cutting the plant off at the ground with a sharp knife.

Varieties

In some sources, this plant is listed simply as Chinese celery.

‘Chinese Golden’: yellowish green stems and leaves; small leaves; resistant to cold temperatures

‘Green Queen’: deep green stems and leaves; tender and flavorful

How to prepare: Chinese celery is a staple in many Asian soups and stews. It is stronger in flavor than American celery types and is used in lesser amounts. Both stems and leaves keep their flavor well when dried.

CORIANDER

CILANTRO (CHINESE PARSLEY)

Coriandrum sativum

Cantonese: yuen sai; Hindi: dhania; Thai: pak chee; Vietnamese: ngo

CULANTRO (SAW-LEAF HERB)

Eryngium foetidum

Thai: pak chee farang; Vietnamese: ngo gai

RAU RAM (VIETNAMESE CORIANDER, LAKSA LEAF)

Polygonum odoratum

Thai: phak phai

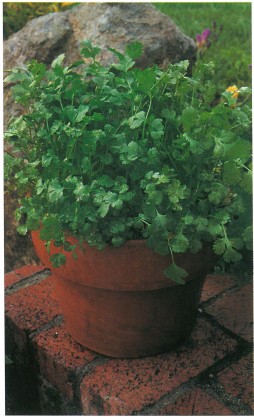

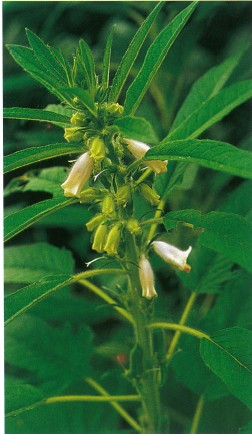

Coriander is a utilitarian herb, for all parts of the plant are used. The common names are rather confusing. Its brown seeds are called coriander. In most of the world, including Asia, its fresh leaves are known as fresh coriander, but in America, it is commonly called cilantro or Chinese parsley. No matter what you call it, this herb is among the most popular on the planet. Its aroma and rather soapy taste cause people to either relish it or dislike it intensely.

Two coriander mimics are also used in Asian cuisines: rau ram (most often known in the nursery trade by this name, but also called Vietnamese coriander), and culantro, also known in Asian markets as saw-leaf herb, which perfectly describes the shape of its long, incised leaves.

How to grow: The standard coriander is an easily grown cool-weather annual herb. It bolts to seed readily when the days start to lengthen and in warm weather. Therefore, it is best planted in the fall. In cold-winter areas, the seeds sprout the next spring after the ground thaws, and in mild-winter areas, the plants grow lush and tall. (Coriander tolerates light frosts.) In short-spring areas, early plantings are more successful than late. One guaranteed way to grow under these conditions is to treat the plant as a cut-and-come-again crop; plant seeds an inch apart and snip seedlings at ground level when they’re 3 inches tall, then replant every 2 weeks until the weather gets too warm.

When possible, start coriander from seeds in place, as it withstands transplanting poorly. Plant seeds ¼ inch deep in rich, light soil and in full sun. Thin the seedlings to 6 inches and keep moist. The varieties most commonly available in nurseries, while adequate, are bred to quickly bolt and produce seeds for the world seed trade. If you choose varieties bred for leaf production instead, such as ‘Long Standing’ and ‘Slo-Bolt,’ available from mail-order seed companies, you’ll harvest leaves for a longer time. Fertilize if plants get pale. Except for slugs, coriander has few pests and diseases.

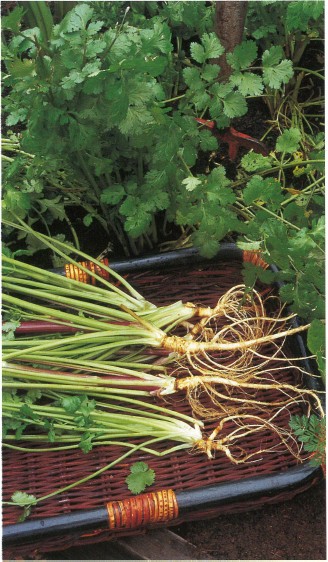

Harvest sprigs once plants are 6 inches tall. When the roots are needed for a recipe, harvest whole, vigorous plants using a spading fork. (Plants that have started to bolt are not suitable, as they are fibrous.) Before digging them up, loosen the soil well around the roots so they won’t break.

Rau Ram, Vietnamese coriander (above); ‘Slo-Bolt’ coriander (below)

Coriander root

The coriander mimics, rau ram and culantro, are tender perennials available from a few specialty herb nurseries. Rau ram is offered in plant form from herb specialists but will root in water from bunches available in Asian markets. Rau ram is a spreading plant about 1½ feet tall, grown in filtered sun. It likes fertile, moist soil. It is considered invasive in areas where it thrives, but its shallow roots makes it easy to control. It tolerates no frost and, in cold-winter zones, is grown as an annual.

Culantro is available from specialty nurseries as seeds or plants and is an excellent cilantro substitute. It is treated as a short-lived perennial in warm-climate zones. Below Zone 9, culantro is grown as an annual. Sow seeds indoors in early winter and set seedlings out when the soil has warmed. (Seeds are slow to germinate). Grow culantro in moderately fertile, fast-draining, moist soil in full sun. In warm climates, grow it in filtered sun. It may also be grown in containers and wintered over inside. Culantro grows to 2 feet tall with a rosette of sharply toothed oblong basal leaves (growing from the crown at the base of the plant) about 4 inches long and 1 inch wide. Flowering stems grow to about 18 inches. Keep flowering stems cut back in order for a continual harvest of the basal leaves. Control slugs and snails.

Varieties

When choosing coriander (cilantro) varieties for leaf production, chose those designated as slow-bolting, available from Shepherds, Nichols, and Johnny’s. See the specialty herb catalogs listed in the Resources section for culantro and Vietnamese coriander.

How to prepare: Coriander leaves are used fresh, as the flavor fades quickly when they are cooked. Generally, they are chopped and sprinkled on a dish or mixed in after cooking to give a distinct flavor. In many Asian dishes, coriander is among the most important flavorings. There is no successful way to preserve the flavor of coriander, as it fades quickly once the essential oils are exposed to air. Culantro, on the other hand, retains good flavor and color when dried, but for the best flavor it still needs to be added at the end of cooking. Culantro is most often used in dishes with beef.

Coriander seeds are used to season curries and rice dishes. The seeds are more flavorful if you toast them in a dry frying pan for a few minutes before grinding them in a spice grinder.

Coriander roots are a favored seasoning in Thai cookery. The roots are pounded together with garlic as a savory mixture in curries, particularly in red and green curry pastes (see recipe, page 86.) In recipes that call for coriander root, you can substitute coriander stems.

Rau ram is used fresh in soups, green and chicken salads, and as a fresh garnish. See the recipe for salad rolls on page 78 and for Henry’s salad on page 77. In Singapore and Malaysia, the Chinese population adds rau ram to a spicy noodle dish. Rau ram is generally used fresh, for it is quite odiferous when cooked. For this reason, it is best added just before serving it in hot foods and soups.

CORN, BABY

Zea mays

Close-up of baby corn (above); Corn plant (below)

Growing baby corn is a fun project to do with kids and the resulting cobs are sweet and crunchy, not tinny tasting like the canned ones.

How to grow: Baby corn is a different experience than sweet corn but equally rewarding. Because ears full of kernels are not the goal, plants can be crowded together and pollination and corn borers are not an issue.

All corn plants require summer heat and full sun and are best planted from seeds sown directly into the garden in organic, fertile soil. Choose from the varieties listed below. Plant seeds 1 inch deep and 3 inches apart. Thin to 6 inches. Side dress with a high-nitrogen fertilizer when plants are about 6 inches tall. Mulch with an organic mulch to control weeds and conserve moisture. Birds steal the seeds out of the ground, so cover the beds. Fertilize again when about 2 feet tall. Water regularly. Keep an eye on your plants, as baby corn is ready early in the season. The object is to harvest the cobs when they are young and tender, before they start to develop, usually within 4 days of the appearance of silks.

Varieties

Choose varieties that tend to produce multiple shoots per plant, as they give more ears.

‘Baby Corn’: about 65 days for immature ears; a variety especially cultivated for baby corn, not sweet corn; offered by Nichols Garden Nursery and Evergreen Y. H. Enterprises.

‘Japanese Hulless’: 100 days to popcorn, much less for baby corn; plants short, to 5 feet

‘Jubilee’: 85 days to mature corn; a midseason hybrid; if allowed to mature, produces sweet yellow kernels

How to prepare: Remove the husks and silks and trim the stem. Fresh baby corn needs a few more minutes of cooking then the conventional canned product.

Baby corn is most associated with China and, to a lesser degree, Japan. Sometimes it is added to sweet-and-sour recipes and stir-fries; in parts of China, it is braised in a broth with whole baby bak choy and mushrooms and glazed. It is also used as a garnish for fancy presentations, sometimes with baby pac choi and a gravy.

CUCUMBERS

Cucumis sativus

Chinese: huang-kwa; Hindi: khira; Japanese: kyuuri; Thai: taeng-kwa

‘Suyo Cross’ cucumber

Cucumbers are enjoyed in much of Asia, especially as pickles.

How to grow: Cucumbers are warm-season annuals and tolerate no frost. They need full sun, rich, humus-filled soil, and ample water during the growing season. Work bone and blood meal into the soil before planting. When soil and weather are warm, plant the seeds about 1 inch deep and 6 inches apart. Thin later to 2 feet apart. Put a trellis in place at the time of planting. Succession planting in long-summer areas provides cucumbers into the fall. If plants are pale, apply fish emulsion.

Young cucumber plants are susceptible to cutworms, snails, and striped and spotted cucumber beetles. The adult beetles can destroy young cucumber vines and carry diseases. Floating row covers keep beetles away but need to be removed when the plants flower so bees can pollinate the flowers.

Powdery mildew is a common problem, particularly late in the season. More serious diseases affect cucumbers as well—mosaic virus, scab, and anthracnose. Scab attacks the fruits and is characterized by dry, corky patches with a velvety olive green growth. Anthracnose shows up as moldy fruit and brown patches on the leaves. Pull up affected plants, as no cure is known for any of these conditions. When possible, plant resistant varieties and rotate your crops.

Harvest cucumbers when they are young and firm but filled out. Harvest regularly or plants stop production.

Varieties

The Japanese have developed many of today’s hybrid sweet cucumbers; these are carried by most seed companies and often classified as “burpless.”

‘Japanese Long Pickling’: 60 days; dark green, crisp fruits to 1 foot

‘Orient Express’: 60 days; hybrid; slim, dark green fruits; disease tolerant

‘Suyo Cross’: 61 days; hybrid with northern China origins; large vines; fruits ribbed, dark green to 1 foot; disease resistant

‘Sweet Success’: 58 days; hybrid; foot-long fruits with sweet flavor; good disease resistance; can be grown outside or in greenhouse

How to prepare: Cucumbers are pickled in most of Asia and used as a condiment. Asian cooks often sprinkle sliced cucumbers with salt to draw out some of the liquid before using them in a dish. In Thailand, cucumbers are grated with onions and dressed with chiles, lemon juice, and fish sauce for a salad. In India, cucumbers are considered healthful and are popular when grated and combined with yogurt and mint, as a salad, and as a cooked vegetable. In Sri Lanka, cucumbers are combined with coconut milk and chiles to accompany a curry; in Korea, cucumber slices are sometimes stir-fried with beef. Japanese cooks make a soup with chicken, ginger, and cucumber wedges.

DAIKON

Raphanus sativus

Cantonese: lo bok; Mandarin: lao bo; Japanese: daikon; Hindi: muli

‘Mino Early’ and ‘Red Meat’ radishes

Two types of radishes are used in Asia: the small spring European-style radishes and the very large radishes generally called Chinese radishes or by their Japanese name, daikon. The large Asian radishes are the subject They vary in size and shape from round globes about 6 inches in diameter to long roots of up to 2 feet. Japanese daikons are usually white, while the Chinese radishes may be white, red, or green.

Asian radishes are juicy and flavorful, ranging in taste from mild and sweet Chinese to the strong and pungent. Radish roots are served either raw or cooked. With some varieties, the leaves, seed pods, and seeds are also used. Certain varieties store well and are used as a winter staple. Varieties of strong-flavored Korean radishes are used in kim chee. High-quality daikons are fine-textured, nonfibrous radishes with juicy flesh.

Radish seeds are easily sprouted, producing highly nutritious seedlings.

How to grow: Most varieties of Asian radishes are planted in fall and mature in cool weather, but a few can be planted in the spring. Sow radish seeds directly in the garden. Plant seeds ½ inch deep; thin to 4 inches apart for smaller varieties and up to 16 inches apart for the largest. They can be planted in rows or wide beds. The soil should be light and well drained, with a generous amount of compost. Radishes are light feeders, however, so they need little fertilizer. Keep radishes consistently moist to avoid cracking and too hot a taste, though you should take care not to overwater. Keep beds weeded.

In some areas of the country, radishes are bothered by root maggots that are best controlled by rotating crops. Radishes belong to the same family as cabbages and other brassicas, so they should not follow each other. Flea beetles can also be a problem. Alternaria, clubroot, and certain viruses are potential diseases. When possible, purchase resistant varieties.

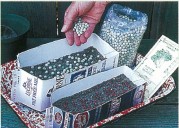

[How to Sprout Peas and Daikon]

You can sprout daikon and peas in a jar to produce curly white sprouts in the same way you do mung and soybeans are sprouted (see page 25). Or, for tastier sprouts, you can produce little green plants in a shallow container such as a paper milk carton, one side removed, laid horizontally. For drainage, punch 6 or 8 holes in the bottom. Add an inch or so of damp sand, sprinkle a few tablespoons of untreated daikon or pea seeds over it, and add a thin layer of sand on top. Water the seeds and put the container on a tray to catch the drips, then put the container in a dark closet. Keep the seeds moist but not wet. They will germinate in 3 to 5 days and grow into white, thin seedlings. When they are about 2 inches tall, bring them out into a well-lit but not sunny area to turn green. In a day or so, the young plants will be green, have a few leaves, and be ready for harvesting. To harvest, cut across the plants above the soil line with scissors.

Generally speaking, these large, long-season radishes can be harvested at any stage. After reaching maturity, they can be left in the ground for 1 to 2 months but may become tough if left much longer. They keep well if stored in a cool place. In Japan, they are sometimes left in the garden, covered with snow. For radish leaves, harvest the tender young leaves of varieties being grown for roots, or grow special varieties bred just for the leaves and harvest at any stage as needed.

Varieties

‘Mino Early’: 40 days; long white roots to 24 inches; crisp, mild; Japanese type; vigorous plants for spring and fall

‘Misato Green’: 60 days; long roots; Chinese radish with high-quality green, juicy, sweet flesh

‘Misato Rose’: 60 days; rose-colored flesh, light green and white skin; turnip-shaped roots about 4 inches across; tender and sweet; used fresh and pickled; not for spring planting

‘Miyashige’: 60 days; a white-fleshed, green-necked fall radish with crisp flesh; popular for pickling

‘Shinrimei’ (‘Red Meat’): Chinese “beauty heart” radish with white skin, green shoulders, and red flesh; good raw or cooked

How to prepare: Throughout Asia, the young, tender green tops of Asian radishes are braised or added to soups, and radish roots are washed, scraped, and cut up or grated for addition to soups and other dishes.

The Chinese use cooked radishes in many ways but rarely use the root raw. They often stir-fry radishes after salting and draining them. The stir-fries include pork, shrimp, or shellfish. Also, radishes are made into hearty winter soups and stews. Chinese sauces sometimes contain grated radishes.

According to Elizabeth Andoh, author of Japanese cookbooks, in Japan, daikon is “the all-impressive, all-purpose, absolutely everything kind of vegetable. When it’s in season, it would be hard to find anybody in Japan who hadn’t eaten a daikon within three days.” Daikon is usually finely grated and often mixed with soy sauce to make a dipping sauce served with tempura and other dishes. Chunks of daikon can be steamed and sauced with miso. A traditional New Year dish is julienned strips of daikon, carrots, and dried apricots served with a sweet-and-sour sauce. Daikons are pickled in rice vinegar or rice wine and soy sauce or prepared as salt pickles, which are used as an accompaniment to the meal or added to dishes as a flavoring. They are also braised or used in fish stew, soups, and salads.

EGGPLANTS

Solanum melongena

Chinese: ngai gwa; India: brinjal; Japanese: nasubi; Thai: makhua terung

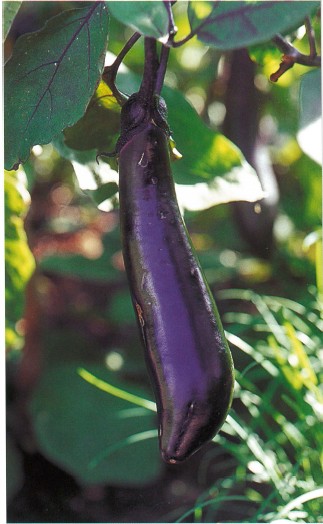

Japanese eggplant

The most common eggplant in Asia is long, thin, and purple.

How to grow: Eggplants are tender perennials, usually grown as annuals. Eggplants tolerate no cold; start seeds indoors 6 weeks before the average date of your last frost. The seeds germinate best at 80°F. Plant the seeds ¼ inch deep, in flats or peat pots. When all danger of frost is past and the soil is warm, mulch with organic matter and transplant the seedlings into the garden 2 feet apart; water well. Grow eggplants in full sun in rich, well-drained, fertile garden loam. Work a balanced organic fertilizer for vegetables into the soil before planting at the rate recommended on the package. Stake the plants to prevent them from falling over with a heavy harvest. To increase yield and to keep the plants healthy, feed them with fish emulsion twice during the summer. If you are growing eggplants in a cool climate, cover the soil with black or red plastic to retain heat. Eggplants need moderate watering and should never be allowed to dry out.

Flea beetles, spider mites, and whiteflies can be a problem. Spider mites can be a nuisance in warm, dry weather. Nematodes are sometimes a problem in the South. Verticillium wilt and phomopsis blight are common disease problems in humid climates.

Eggplant is ready to harvest when it is full colored but has not yet begun to lose any of its sheen. Press down on the eggplant with your finger; if the flesh presses in and bounces back, it is ripe.

Varieties

‘Asian Bride’: 70 days; white skins streaked with lavender; 6 inches long, 1½ inches in diameter

‘Bharta’: 60 days to flower; East Indian variety; large, round purple-black fruits with few seeds; productive

‘Green Tiger’: 75 days; Thai variety with pale green fruits with dark green stripes; 1 to 2 inches round; plants 3 feet tall, productive

‘Harabegan’: 60 days to flowering; elongated (to 10 inches), shiny green fruits with few seeds; East Indian variety

‘Ichiban Hybrid’: 61 days; long, slender, high-quality purple fruits; high-yielding plants

‘Ping Tung’: 75 days; slender, lavender to purple fruits to 18 inches long; prolific; heat and humidity tolerant; traditional Taiwanese variety

How to prepare: The standard Asian eggplants have tender skin and little bitterness, and therefore needn’t be peeled or salted. Chinese cooking methods for eggplants include braising and frying. In Shantung, cooked eggplant is served cold with a sesame sauce and, in Szechwan, eggplants are fried and served in a spicy sauce. In Japan, eggplant is used in tempura, baked and served with a variety of sauces, including a dipping sauce of grated ginger and soy sauce, braised in sesame and bean sauce, and pickled. In Thailand, eggplants are usually used in sweet-and-sour dishes or in curries. In India, eggplants are often stuffed and cooked in a savory sauce or baked and the flesh mixed with spices (see recipe, page 85).

GARLIC

Allium sativum

Cantonese: suen tau/to Mandarin: suan;Japanese: nin-niku

Young garlic plants

Garlic is popular in all of Asia, with two notable exceptions. The Japanese avoid it because of its lingering odor and the Brahmans in India do because they believe it stirs the baser passions. On the other hand, in much of Asia, people value its medicinal properties.

How to grow: Garlic plants are grown from cloves that can be purchased as heads in the nurseries. Although easily grown, garlic performs best in mild, dry climates. It’s best planted in the fall or early spring. Garlic prefers full sun and a well-drained, loose soil rich in organic matter and phosphorus.

Divide the heads into individual cloves and plant them about 1½ inches deep and 4 inches apart. In cold-winter areas, mulch with straw to protect fall-started plants. Consistent moisture is needed for the first 4 months. Fertilize in early spring, when the leaves are growing, with an organic source of nitrogen. Plants with healthy, leafy growth produce the best bulbs. Decrease your watering once the leaves fill out.

In Asia, whole young garlic plants are sometimes harvested, as are the flowering stalks. Garlic greens are also sometimes lightly harvested and used in cooking as you would scallions, providing the plants are not depleted. Garlic is ready for harvest when the plant tops turn brown (the ideal moment is when about half of the leaves are still green). Dig the heads and allow them to dry on a screen in the shade, protected from sunburn. To prevent rotting and to allow braiding, retain several inches of dried stalk on each head. Store garlic in a cool, dry area with good air circulation.

Varieties

‘Georgian Crystal’: large white bulbs; very mild flavor, good raw; stores well

‘Gilroy California Late’: good flavor, juicy cloves, long keeping; ideal for braiding

‘German Extra-Hardy’: very winter-hardy, good for northern gardens, good flavor, keeps well

‘Romanian Red’: cloves streaked with red; hot and pungent; stores very well

How to prepare: In China, garlic cloves are used in almost all meat, poultry, and vegetable stir-fries; in stews, and in marinades for grilling. In northern China, whole young garlic plants are sometimes stir-fried with smoked pork, and a traditional dish of steamed prawns calls for great amounts of minced garlic. Garlic is a favorite in Korea where, along with chiles, it is an integral to the national dish, kim chee, and popular in many cooked dishes. In India and Southeast Asia, garlic is often included in curries of all sorts. In fact, author Charmaine Solomon describes a dish of southern India where whole garlic is treated as a vegetable and cooked in a curry sauce. In addition, whole garlic cloves are pickled and enjoyed in most of Asia.

GARLIC CHIVES

(CHINESE CHIVES)

Allium tuberosum

Cantonese: gau tsoi; Japanese: nira; Mandarin: jiu cai; Thai: kui chaai; Vietnamese: he

CHINESE LEEK

(CHINESE LEEK FLOWER)

Allium ramosum (A. odorum)

Cantonese: gau choi fa

Chinese chives, blanched

Garlic chives are a fairly common herb in the West. In contrast, Chinese leek is rarely available and is a variety grown primarily for its young, tender flower stems and buds. Both of these Asian alliums are related to common chives (A. schoenoprasum) and have an onion-garlic flavor, narrow, flat leaves to 2 feet tall, and flat sprays of white, star-shaped flowers. Both are perennial plants hardy to USDA Zone 3 and native to Asia.

How to grow: These alliums are best planted in spring. They need at least 6 hours of sun daily and average to rich, well-drained, moist soil. Seedlings grow slowly and, in short climates, usually take the entire season to mature from seeds, so they are not harvested the first year.

Once established, garlic chives bloom but once, in early fall. Chinese leeks, on the other hand, bloom at least twice throughout the spring and summer and produce multiple stems with fat flower buds. These alliums grow best and are most tender and succulent if fertilized in spring and later, too, if the leaves turn pale. In rainy areas, supplemental water is seldom needed, and pests (except for occasional black aphids) and diseases are few.

Harvest the leaves a few at a time or cut the entire plant down to the crown when the leaves are tender and lush. If you have not harvested them heavily, cut them back after they flower to tidy and renew the plants. Remove the seed heads on garlic chives, as they reseed readily and can become a nuisance. Divide all plants every 3 or 4 years.

In Asia, mature chive plants are sometimes blanched in the garden to produce yellow, tender leaves and stalks. This is done by completely excluding light. Plants at least a year old are first cut to the ground and a solid container 10 or so inches deep is inverted over the crowns to exclude the light. Within 10 days to 3 weeks, long, pale leaves are ready for harvest. To prevent weakening the plant, blanching is usually done but once a year.

Varieties

Garlic chives can be obtained as divisions, transplants, and seeds. Chinese leeks are seldom available, and then only from seeds. Seeds of both are available from Evergreen Y. H. Enterprises.

How to prepare: These Asian alliums have a strong taste, more like garlic than onion, and tend to get stringy and tasteless when overcooked. The green leaves of Chinese chives are often cut in sections 1 or 2 inches long and used in stir-fries with meat and oyster sauce, pork, chicken, and bean curd; in soups; simmered in broth; and braised and served alone as a vegetable. In much of northern China, chopped chives are used in steamed and fried breads and in dumplings. Chinese leek flower stems and buds are often used in the same manner. Prepare them as you would asparagus, by removing any tough lower parts of the stem.

Yellow chives are the blanched leaves of garlic chives. Blanching renders them softer, with a sweet and mellow onion flavor. They require only brief cooking and are usually added to a dish at the last minute. They are stir-fried with noodles, pork, and poultry as well as used in soups and steamed dishes. See the pea shoots with crab sauce recipe on page 71.

In Japan, chive leaves are cut in lengths and added to soups and sukiyaki or used whole as a garnish.

GINGER

(TRUE GINGER)

Zingiber officinale

Chinese: saa jiang

MIOGA GINGER

Z. mioga

Hindi: chandramala; Thai: proh hom

Ginger sprouts (above); ginger plant (center); and Mioga ginger flower buds, ready for harvest (below)

True ginger can grow to 4 feet. The leaves are narrow and a light, bright green. Both the shoots and rhizomes are edible. Mioga ginger is grown for its flower buds and leaves. The rhizomes are not edible.

How to grow: Gingers are tender, deciduous perennials needing long, warm, humid summers. They are worth trying in cooler or drier climates but tend to be temperamental and should be considered an experiment. Gingers prefer bright light to hot sun, so plant in a warm, fairly shady spot. They also need rich, moist soil with good drainage, as they will rot in cold, wet soil. Keep well watered. In tropical regions, true ginger is planted in early spring and the rhizomes harvested 9 months later, in late fall. In cold-winter areas, start ginger in the house, planting outside when the weather warms up. Ginger can also be grown as a houseplant. Move up to larger pots as it grows.

True ginger can be harvested after 5 months when it has plenty of full-grown leaves, but for the biggest harvest, wait for 8 or 9 months. If the weather becomes too cold, either harvest the rhizomes or bring the entire plant into the house for the fall and let it grow in a well-lit room until fully mature. When harvesting, save a rhizome to replant, thus maintaining your own source of this delightful flavoring.

Mioga ginger is a Japanese ginger that is more tolerant of colder climates. The flowers and leaves are harvested while young. The leaves are usually blanched before harvesting by covering so that light cannot reach them. The flowers buds are harvested just before they emerge from the soil and before they are open by breaking them off the parent rhizome.

Varieties

Fresh rhizomes of true ginger, called ginger root, are available at produce stands or in Asian markets. Choose rhizomes that show good growth buds (like eyes on a potato). True ginger is also offered by Richters Herbs and The Banana Tree. Mioga ginger is rare but sometimes available from nurseries that cater to a Japanese clientele. I purchased mine from a vendor at my local farmers’ market.

How to prepare: Mature ginger is stronger in flavor than freshly dug, thin-skinned young ginger. Ginger root is peeled and sliced in a dish then removed, or very finely minced and left in the cooked dish. Ginger is used in all of Asia to add a lovely spicy flavor to soups, stews, dressings, and stir-fries. See the many stir-fries in the recipe section to get a feel for how to use ginger. Mioga ginger flowers and leaves are used for flavoring in stir-fries (see recipe, page 68) and soups.

LEMON GRASS

(CITRONELLA GRASS)

Cymbopogon citratus

Hindi: herva chaha; Indonesian: sereh; Thai: ta krai; Vietnamese: xa

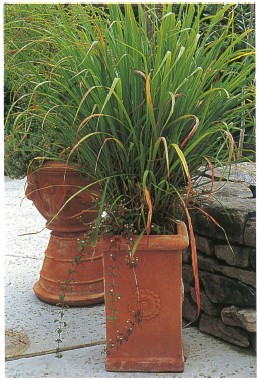

Lemon grass plant (above), and how to mince (below)

A citrus-scented grass-family herb, lemon grass is prized in Southeast Asia. This tropical perennial is a large, clump-forming herb that grows to 3 feet in temperate climates. The lemon-scented oils are in the stems.

How to grow: Lemon grass can be grown outdoors in climates where the temperature stays above the mid-twenties and in containers in cold climates, if brought inside in winter. Plant divisions in good, fast-draining soil in partial shade. Fertilize the plants a few times during the growing season and keep the soil moist. Lemon grass has few disease and pest problems.

Varieties

Purchase divisions from specialty seed companies. If a few roots are attached, sometimes a stalk from the market will root.

How to prepare: Harvest the white leafstalks by cutting them at the base of the plant once it’s established. Use them to flavor chicken stock-based soups, with or without coconut milk, and fish stock-based soups. Lemon grass is also used in salad dressings and to make a fragrant cup of tea (see recipe, page 65). Depending on the recipe, the stalks are cut into 2-inch lengths, sliced thinly crosswise, or coarsely chopped. Usually the stalks are removed from a dish before serving, but they are also minced and added to stir-fries and curries or pounded together with other herbs to form a paste for adding to a dish (see the Thai curry recipe on page 88). To preserve lemon grass, either dry it or freeze the fleshy stalks.

LIME LEAF

(KAFFIR LIME, FRAGRANT LIME)

Citrus hystrix

Indonesian: jeruk perut; Thai: bai magrood; Vietnamese: la chanh

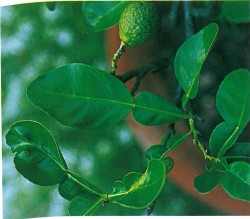

Lime leaf plant

Lime leaf is an evergreen citrus—a small tree with rounded leaves indented on either side, and with knobby fruit. Its fragrant leaves and thick green rind are used in cooking. The juice from the fruit is sour and seldom utilized.

How to grow: Lime leaf is grown outside where there is no frost; in other regions, grow it in containers and bring it indoors in winter. Plant the tree in a large pot in fast-draining soil. Maintain a regular watering schedule; through the summer, fertilize once a month with citrus fertilizer.

Lime leaf with fruit

Outside, grow lime leaf in well-drained organic soil. Add a citrus fertilize according to the directions on the package. Grow lime leaf in full sun. Beginning in the spring, feed with citrus fertilizer, tapering off in late summer to discourage new growth susceptible to frost.

Varieties

Pacific Tree Farms ships lime leaf.

How to prepare: Kaffir lime leaves may be harvested when the tree is established and its leaves are at least 3 inches long. The fragrant leaves function in cooking like bay leaves, slowly releasing their citrus flavor in long-simmered dishes, soups, and curries. They are excellent in fish dishes and can be minced and ground to a paste with Other herbs and spices such as coriander root, lemon grass, and garlic to add to curries (see recipe, page 88), chicken, and other meat dishes. The fresh leaves may be wrapped tightly in plastic wrap and frozen for future use. Finely shredded, the rind may be sprinkled over salads and added to currie during the last few moments of cooking.

LUFFA, ANGLED

(CHINESE OKRA, RIDGED SKIN LUFFA)

Luffa acutangula

Hindi: kali tori; Mandarin: si gua; Cantonese: sze kwa

LUFFA, SMOOTH

(SPONGE GOURD)

L. cylindrica

Hindi: ghiya tori; Mandarin: si gua; Cantonese: see kwa; Japanese: hechima

Luffa sponge gourd (top) and luff flower (above)

The two types of luffa are both annual vining plants in the cucumber family. Their fruits, associated with Chinese cooking, are eaten as a vegetable when young. Luffa acutangula has long, narrow fruits with ridged skin and large, fragrant yellow flowers. L. cylindrica has more cylindrical fruits with smoother skin.

How to grow: The cultivation of both luffas is the same. They need a long, warm growing season. Grow and maintain them as you would cucumbers (see the entry for Cucumbers). Harvest the fruits when they are still immature and about 6 inches long.

Varieties

Many catalogs list luffa simply under the common names. While unstated in the catalog, some varieties are short-day plants and don’t flower in northern latitudes.

‘Edible Ace’: smooth, green fruits; 8 to 15 inches long, 3 inches across; use the immature fruits for a vegetable, good matured for bath sponges

Chinese Okra: 90 days; the immature flesh is very tender and sweet; no peeling necessary

How to prepare: Luffa fruits are edible only when immature. Cook them much as you would zucchini. The flower buds, young shoots, and young leaves are edible and may be added to stir-fries. The whole fruits can be stuffed with ground pork and braised. A traditional Chinese soup is made with pork or chicken broth and bean curd cubes. Just before serving the soup, thinly sliced luffa is added and briefly cooked.

Do not eat the mature fruits; they are extremely bitter and are a strong laxative.

MITSUBA

(JAPANESE PARSLEY; TREFOIL)

Cryptotaenia japonica

Cantonese: san ip; Mandarin: san ye qin

Mitsuba

The word mitsuba means “three leaves” in Japanese. Mitsuba looks and tastes a bit like Italian parsley, with dark green, trifoliate leaves and long, pale stems. In Japanese cuisine, every part of the herb is used—leaves, leafstalks, roots, and seeds.

How to grow: Mitsuba grows to 3 feet tall and is usually treated as an annual, although it’s a perennial. Start mitsuba from seed, sow ¼ inch deep, and thin to 1 foot apart. Mitsuba is a woodland plant. Grow it in moist soil in partial shade and keep plants moist.

Harvest a few leaves once the plant is established and the young stems as you need them once they are a foot tall. When the older stems become tough, they can be used in longer-cooking dishes. Let a few plants go to seed for the next year’s planting.

In Japan, mitsuba is sometimes garden blanched in the same manner as celery.

Varieties

Unnamed mitsuba is carried by Kitazawa Seed Company and Evergreen Y. H. Enterprises.

How to prepare: Mitsuba leaves and stems are boiled for a minute or two and eaten as a green, raw in salads, pickled in vinegar, fried in tempura batter, added to soups, including eggdrop soup, and used for flavoring and as a garnish. When used in soups or as a garnish, the leaves and stems are generally chopped and added in the last minute of cooking.

According to herb maven Holly Shimizu, often, on important occasions—a wedding or the finalizing of a business contract—several stalks of mitsuba are tied together in a knot and added to a dish for decoration. In Japan, the knot is considered an auspicious symbol.

MIBUNA

(MIBU GREENS)

Brassica spp.

MIZUNA

(POT-HERB MUSTARD)

B. rapa var. japonica

Mandarin: shui cai; Japanese: kyona, mizuna

MUSTARD

HEADED (WRAPPED HEART)

Brassica juncea

Mandarin: bao xin da jie cai; Cantonese: yeh choi; Japanese: kekkyu takana

MUSTARD

JAPANESE RED

Brassica juncea var. rugosa

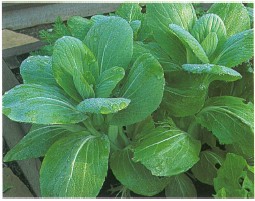

Mizuna

In general, Asian mustards are mild to pungent loose-leafed vegetables that grow from one to several feet in height. Most prefer cool growing conditions. Headed mustards form heads of pale green, thin-textured leaves that curl inward and are grown mainly for pickling. Japanese red mustards have bronze red leaves that are quite peppery. Mizuna is a strikingly beautiful cut-leafed vegetable that is popular in Japan. Mibuna is a mild-flavored Japanese green with a pleasant mustardy taste. Mibuna plants, which can grow up to 2 feet, have multiple stems with slender, smooth leaves at the end of each.

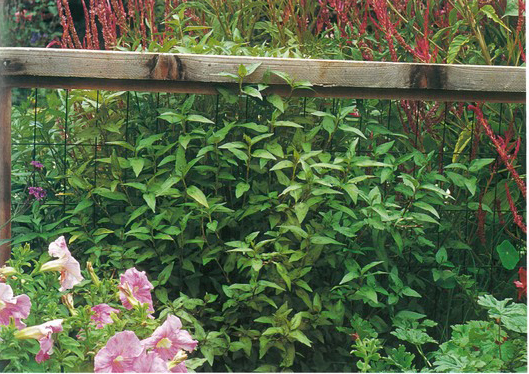

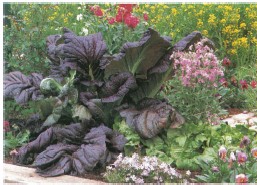

‘Giant Red Mustard’ cut-and-come-again (above); ‘Giant Red Mustard’ with mizuna in bloom in back; ‘Osaka Purple’ with peas; Shirona mustard showing slug and army worm damage

How to grow: Mustards are fast-growing cool-season crops. They do best in a fertile organic soil with good drainage. Plant seeds in full sun, ¼ inch deep and 3 inches apart, in early spring or fall. Thin to 1 foot apart if growing to maturity. Alternately, broadcast the seeds of Japanese mustard or mizuna and grow as baby greens in a cut-and-come-again method by themselves or mixed. For mature heads of headed mustard, sow in midsummer or early fall for fall or early winter harvest.

Mustards need sufficient moisture while growing or they may become too spicy to eat. Mustards are relatively disease free, although, as members of the cabbage family, they are occasionally plagued by pests that bother that group (see the entry for Chinese Cabbage).

Harvest a few leaves at a time as they are needed. For Japanese red mustard, the younger the leaf, the milder. Mizuna tends to tolerate both heat and cold, so it can be harvested over a long time. Harvest headed mustards mature heads as you would cabbage.

Varieties

Pickling Mustards

‘Nan-fong’: Chinese mustard; heat tolerant; can be planted spring through fall; large leaves and thick stems

‘Green-in-the-Snow’: very hardy; vigorous

Japanese Red Mustard

‘Osaka Purple’: 40 days; milder and more compact than ‘Giant Red’; leaves purple with white ve ins; great for baby greens

‘Red Giant Mustard’: 45 days; deep purple red savoyed leaves; tangy leaves; great for baby greens

Mibuna and Mizuna

Named varieties of mibuna and mizuna may not be listed. Mizuna is quick-growing and days to maturity start at 45 days.