Color cinematography will play a great role in the future, in influencing public taste in the choice of dress, household furnishings, wall and floor coverings; will make the public color conscious, teach them something of color harmony, of the effect of complementaries, altogether have an influence which we who are too close to our subject generally overlook.

—John Seitz, Cinematographic Annual (1930)

As a modern ready-made, color’s impact on the consumer was increasingly harnessed in the 1920s. Inherent in the drive for industrial standardization in design and production, manufacturers appealed to consumers by drawing on a range of chromatic methods and media through various advertising tie-up campaigns that targeted cinema audiences. In addition to print, film became increasingly important for the promotion of products and fashions, particularly as advertising consultants advocated the advantages of using color in mass marketing campaigns. This chapter illustrates the decade’s many examples of film’s vitality within a chromatically rich, transnational advertising and fashion culture that was responsive to the growth of mass consumption within the field of cultural production. A network of different groups pioneered new media approaches for advertising color products, entertainments, and artistic expressions, in which fashion in film played a pivotal role. Fashion refers here to more than dress. As cinematographer John Seitz noted, it also includes home décor, commodity culture, and design, as well as the dynamic commercial environment that was increasingly informed by ideas about psychology and what was at the time termed “color consciousness.”

For Pierre Bourdieu, the field of cultural production encompasses both high and vernacular art, what he terms “restricted” and “large-scale” production, each with its own internal economies and audiences.1 In terms of fashion, the former is characterized by expensive, haute couture designs with restricted circulation, and the latter refers to the widely available, off-the-shelf fashions of mass production and consumption. Within each area, competitive forces jockey for dominance, and although distinctions can be drawn between their separate economic drives, both haute couture and mass-produced fashions are reducible and interrelatable at a certain level to economies of prestige.2 As we have seen, Bourdieu offers a general model that is useful for thinking through color’s varied impact on the media comprising the field of cultural production in the 1920s. In its demonstration of how color accelerated the reach of fashionable trends associated with haute couture, this chapter examines the complexity around the actual operations of fashion as it negotiated between the highs and lows of cultural production. Rather than maintaining a rigid separation between high fashion and mass production during the 1920s, the boundaries between the two were increasingly blurred, and cinema played a crucial role in this development. Advertising media such as film were instrumental in disseminating images of high fashion to a wider audience, inculcating a culture in which luxury design was not exclusive to the upper classes. The marketing of knowledge about color, fashionable clothes, and décor worked to bring the worlds of high fashion and mass consumption closer together, even if at times that relationship could appear strained and unequal. In this sense, Bourdieu’s theories of economic and cultural capital can be productively extended to understand how the transmission of taste cultures through film and media is not a static but a dynamic and reciprocal process.

The newly formed mass medium of cinema did much to democratize taste cultures during the 1920s, broadening spectators’ horizons to encompass new, fashionable ways of living, dressing, and thinking about color’s impact on the physical environment. Miriam Hansen’s theory of “vernacular modernism” captures cinema’s interrelationship with both high and vernacular forms, arguing that “modernism encompasses a whole range of cultural and artistic practices that register, respond to, and reflect upon processes of modernization and the experience of modernity.”3 Color was central to this mediating process among cultural practices that hitherto had been hierarchically organized, including clothing, architecture, and décor. Although standardization was driven in part by economic and corporate concerns, at the same time it enabled individuals to negotiate modernity through the acquisition of chromatic competences. As argued by New York art lecturer and self-proclaimed color consultant Louis Weinberg, knowing about color was a marker of taste that gave individuals power in making choices for clothes and décor. He even went so far as to suggest that “democracy in color expression” enabled people to critique designers who might be carried away by aberrant fashion trends using colors that were not harmonious.4 An emphasis on creating “tasteful” color compositions in everyday clothing, home décor, and lighting designs, as well as on-screen, resonated widely, involving a large number of professionals and consumers with different motivations for negotiating their way through the color revolution of the day.

The 1929 Pathé-Cinéma film Le home moderne (France) provides a useful illustration of these symbiotic connections and will serve as a thematic guide to the areas explored further in the rest of the chapter. Le home moderne, a short nonfiction film from the Pathé-Revue cine-magazine series, is colored using the Pathéchrome system, a stencil process discussed further in chapter 6. The film advertises Leroy paints and wallpapers by presenting five examples of domestic interior décors to illustrate, according to an intertitle, “a perfect harmony of style and color between furniture and wallpaper.” The rooms—a dining room, bedroom, living room, home office, and living room/boudoir—are displayed to suggest connections and contrasts between furniture and wallpaper in a well-to-do French household. As an applied technique, film stenciling was an excellent means of highlighting detail and color for images that required the addition of a rich, sumptuous textural style. This was particularly appropriate for highlighting the intricacy of Leroy wallpapers, which were also colored by pochoir, a traditional, stencil-based printing technique dating to antiquity that was adapted for film by Pathé in the early 1900s.5 Pochoir was revived in Paris in the 1920s as part of Art Deco design to embellish the modern interior as a tasteful, integrated ensemble. The crafted, textured, graphic look of pochoir inspired fashion designers, including Paul Poiret, as well as architects and designers—a notable example being French architect and film set designer Robert Mallet-Stevens, whose influential illustrated design album A Modern City featured pochoir colored plates of civic and municipal buildings in an “ideal town.”6 Poiret’s pochoir prints were widely reproduced, and interior designers were encouraged by Poiret’s example to “think of their work as part of a fashion system.”7 In Le home moderne, the geometric, streamlined look of Art Deco furniture was thus softened by wallpaper patterned by pochoir with organic shapes such as floral motifs. The modern home in this instance was a unification of shapes, colors, textures, and intermedial forms, both living and nonliving. The Art Deco font used for the intertitles, with its striking resemblance to Poiret’s visual style, makes the film appear as an illustration come to life, exemplifying its strong connections with decorative art, print media, and fashion.

Le home moderne’s aim is to showcase its various products. After an establishing shot of each room, there is a shot of a fashionably dressed person occupying the space, adding a crucial human dimension to the film’s depiction of décor, chromatic harmony, and modern living. The bedroom, for example, has Art Deco furniture, its geometric lines contrasting with blue wallpaper patterned with swirling designs of bows and floral motifs. The creation of a relaxing atmosphere is further emphasized when a woman is shown primping her hair in a long mirror, her dark, plain-cut dress contrasting with the decorative pochoir effect of the walls. This approach is also evident in the living room, with its Chinese-themed wallpaper embellished with gold temple and floral motifs highlighted against a Chinese cabinet, upon which a large vase of flowers is being arranged by a woman with bobbed hair wearing a drop-waist, “garçonne style” day dress.8 The strategy of fitting the room to its function, with color and décor establishing mood, continues in the home office, where the wallpaper has reddish colors with yellow detail that resonates with a yellow lampshade on an Art Deco occasional table. A man, presumably the bourgeois owner of the house, is seen making a telephone call and writing in this room, which is described in the intertitle as “warm and bright.” In the last room, the salon-boudoir, brown-orange wallpaper with a large, floral pattern contrasts with furniture colored in pale shades of blue (as the colors are described in the preceding intertitle); a woman sits reading on the Deco sofa before standing to smoke a cigarette (color plate 2.1), once again creating a sense of a total composition in which colors are showcased through strategies of contrast, complement, associative mood, and ambient sensation.

The film serves as a telling example of how by 1929 ideas about color, taste, and psychology were widespread, indicative of the types of knowledge transfer occurring across media and industrial and cultural fields of the time, as discussed in chapter 1. The connection between colors and moods was clearly evident, as was the notion that rooms inspired certain behaviors and fashions for clothes as well as décor and furniture. That the occupant was part of an entire composition resonates with ideas evident in other areas of 1920s culture, as demonstrated in chapter 3’s discussion of synthesizing color music and the aspiration toward total art. In keeping with this philosophy of fashion, the body and the physical environment were seen as parts of a single ensemble—a composition to be refined, embellished, and above all experienced. The impact of Art Deco was emphasized when placed in spaces that also contained styles from earlier periods that were compatible with a “moderne” look. Although the parts of the whole may be different, together they create the overall impression of an interdependent, creative enterprise. Film was the ideal medium to animate these connections, its visual dynamism capturing the multilayered, collaborative nature of contemporary 1920s design.

This total-art aesthetic was evident in a range of other intermedial contexts. According to 1920s fashion theorist Emily Burbank, stage designers including Léon Bakst, Max Reinhardt, and Granville Barker “taught us the new colour vocabulary” of this expansive mode.9 She refers to “the dependence of every decorative object upon background” and how their designs demonstrate clearly “how fraught with meaning can be an uncompromising outline, and the suggestiveness of really significant detail.”10 Burbank was inspired by the ideas behind English theater designer Edward Gordon Craig’s innovative lighting effects for the stage.11 These highlighted key details while eliminating unnecessary objects that might detract from the overall desired theatrical atmosphere. Burbank argued that nonnaturalistic effects were important because “by the judicious selection of harmonics, the imagination is stimulated to its utmost creative capacity.”12 She found that styles of home decoration and women’s costume were similarly influenced by the judicious selection of harmonious and contrasting colors; clothes highlighted décor and vice-versa “as part of the composition.”13 As an example, she explained how delicate-shaded gowns were best shown against a dark chintz, silk damask sofa in one or several tones, or a solid color. She also referenced how color was “portable”—how in drama the strategic placement of a scarf or a cushion could alter the chromatic dynamics, contrasts, and harmonies of a setting, allowing for changes within a space that could underscore shifting narrative concerns. Other examples of contemporary reportage similarly noted correspondences between décor and feminine fashions as a kind of symbiotic artistic arrangement, as when Gabrielle Amati interviewed Lillian Gish in Florence in 1924 in the studio of Italian textile and fashion designer Maria Gallenga. Even though the interview was with a major Hollywood star, Amanti spent considerable time describing the chromatic impact of velvet dresses, furniture, and even the color of Gish’s eyes.14

These examples illustrate the collapsing of boundaries between design, fashion, and art. They point to the conscious agency of individuals in arranging spaces and personal attire in strategic ways and demonstrate how color worked as a catalyst for holistic design. The competences required to produce satisfying ensembles depended upon knowledge about the effects of light on specific colors, how colors related to each other, and how the textures of fabrics and solid materials affected color when applied in different contexts. The spread of electric lighting in domestic homes in the 1920s accentuated color’s role as part of a planned scheme—a development that represented a departure from the darker interiors of dwellings in the late nineteenth century.15 This cohesive approach was also at the heart of the highly influential Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes held in Paris in 1925, to which we now turn to examine the transnational reach of color consciousness.

The Exposition des Arts Décoratifs and Transnational Exchange

Initially scheduled for 1915, but postponed because of the war, the exposition grew out of the French decorative arts tradition and was meant to showcase and revivify France’s preeminent design traditions.16 Many designs and products that used color in dynamic, innovative ways were on display at the exposition. The Pavilion de l’Elégance was devoted to the work of more than sixty couturiers, with displays organized by designers Paul Poiret and Sonia Delaunay. Delaunay’s “Simultané Boutique” replicated the Paris studio she opened in 1924 with her husband Robert Delaunay. The display showcased her embroidered and geometrically patterned coats, bags, scarves, and jackets, all of which demonstrated her fascination with color, texture, and contrast. “Simultanism” was the term the Delaunays used for their Chevreul-inspired exploration of the rhythms of contrasting colors in various forms from painting to textile design. This also extended to “color-poems” and the use of colored letters and text in paintings and even to clothes, through which Sonia Delaunay sought to suggest “a transnational language of chromatism” that was conceived as musical (“l’audition colorée”) rather than linguistic.17 The philosophy behind this idea is also indebted to Wassily Kandinsky’s theorizing that when different media are comingled, new sensibilities result that transcend their discrete forms and meanings: “The methods of the different arts appear from the outside to be perfectly different from each other. Tone, colour, word! […] But at the deepest level, these methods are perfectly similar: the ultimate aim eliminates their external differences and unveils their intimate identity.”18 Delaunay’s fashion designs and connections with film will be considered in more detail later, but it is worth noting here that her involvement in the Exposition des arts décoratifs reflected the event’s innovative celebration of color in a number of contexts that were underpinned by similar synthesizing philosophies. The mid-1920s were clearly an appropriate time to take stock of the latest developments in color technology and tastes.

In this spirit, Léon Deshairs, 1920s conservator and art historian, felt compelled to publish a book in 1926 of paintings illustrating the relationship between colors and interiors at the exposition so that future generations might be inspired by its demonstration of how French designers in particular thought about color.19 He charted their shift from late-nineteenth-century tastes for “insipid…exhausted shades” toward more confident chromatic choices selected according to prevailing notions of harmony, gradation, and contrast. As an apposite example, he referenced the room designed by Louis Sognot, who collaborated with the Atelier Primavera, which was founded in 1912 by the department store Printemps. The bedroom shown at the exposition’s Primavera Pavilion displayed two screens in antique red lacquer; a carpet with an abstract design in brown, gray, and white; a Makassar ebony bed with a brown fur bedcover; and a cabinet and standard lamp in Art Deco style. An office interior designed by Paul Foliot was dominated by orange-red soft furniture with brown accents achieved with an Art Deco desk, small tables, surrounding bookshelves, and a wall frieze patterned with classical bronze figures and symbols that were a typical feature of Art Deco décor—which, as Lucy Fischer has noted, combined modernist design with a fascination for “Ancient” forms and motifs.20 A dining room with cement-colored walls featured a red-brown-bordered central rug with a black-and-yellow geometric Greek design. To create further dramatic contrast, Jules Leleu and Da Silva Bruhns dressed the room with Makassar ebony furniture. Deshairs commented: “This simple range goes well with a recent innovation: some ceilings colored silver or aluminium have replaced, as reflectors, the white ceilings. Aluminium gray, another color of the day—but that will perhaps stay a color to be put on display—is pale and dull in natural light. It can, as shown by Auguste Perret in his theater, come to life by the pleasant shimmering of electric light.”21 This last remark can be related to the growing perception of color and light as relational, mutually reinforcing yet potentially transformative (“coming to life”) elements, whether in a painting, in a dress, or as part of a décor ensemble.

The publication in 1930 of a book featuring subsequent French designs enabled Deshairs to reflect on developments in interior design since the mid-1920s, particularly the increased use of steel, metal, and wood in conjunction with electric and neon lighting effects: “Light, glistening rustless steel furniture, and soft and mysterious lighting effects—obtained by refraction or diffusion—which entail a minimum of visible fittings and cumbersome supports, typify the taste of 1930 in the domain of interior decoration.”22 Orange once again featured as the dominant color for an Art Deco office by French designer Etienne Kohlmann that emphasized angular furniture, mirrors, and motifs associated with streamlining and industry (color plate 2.2).

While French designs dominated, the exposition was highly influential in the United States and throughout Europe. Inherent in its celebration of Art Deco was a distinct commercial dimension, with major manufacturers and department stores displaying their products, including bathroom accessories, innovative kitchen designs, luxury merchandise, Art Deco furniture, glassware, ceramics, fabrics, and costumes. At the exposition, Sonia Delaunay met Joseph de Leeuw, owner of Metz & Co, a small luxury department store in Amsterdam. He bought scarves, fabrics, and accessories that Delaunay subsequently had branded “Sonia” for sale in the store, initiating a long business relationship that lasted into the 1960s.23 Many designers showcased their work in adjacent Parisian boutiques, transforming the event into a celebration of modern consumerism. This influenced the American delegates who visited Paris for the exposition, inspiring subsequent events, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 1926 traveling exhibition of selected pieces imported from Paris and the Met’s collaboration in 1927 with Macy’s for an “Art in Trade” exhibition in New York. As Regina Blaszczyk has noted, the impact of the exposition extended from couture to industrial products, “pushing some American manufacturers at the upper end of the market to create designs that could rival those of French manufacturers in originality.”24

The exposition’s emphasis on color also reverberated in Britain, as reflected in subsequent Ideal Home exhibitions at Olympia, London, an annual event initiated in 1908 by a daily newspaper to showcase the latest fashions in manufactures and designs for the modern home.25 An enhanced focus on color is striking in the 1927 catalog, which listed products ranging from “Rowlian Coloured Lacquer Furniture” for sale in a Kensington Gallery in London to a special exhibit by Story & Co., London, celebrating “colour in all its splendor” for carpets, hand-painted curtains, and loose-cover fabrics.26 The catalog featured a special article that declared that “colour is the keynote of present-day decoration…. To-day no colour is regarded as too bright, provided that it is used discriminately and harmonises with its surroundings.”27 It remarked upon the vast range of newly available colored paints, wallpapers, wood inlays, tinted glass, silks, fabrics, and painted linens, all with arresting chromatic features. Anticipating Pathé’s Le home moderne, these were contextualized within discourses of color consciousness that connected color with psychology, mood, and taste education:

It is now generally realized that cheerful surroundings have a psychological value. A sympathetic room is a tonic or a rest, as the case may be, and wisely chosen will help to ease the worries of life. Then, too, personality can be definitely expressed in rooms by the use of colour, so that one’s home need not be a replica of somebody else’s, but an expression of individual outlook. An Exhibition such as this is of inestimable value to those who need help in their choice, for it is not everybody who can visualize what a certain colour scheme will look like when it is presented to them in rolls of material. Here they may see schemes actually worked out, can study them at ease, see where they synchronize with their own ideas, and definitely decide what appeals to them most.28

In this way, the influence of the exposition in Paris was widespread and transnational. While much of what was showcased there was far from affordable, the celebration of new furniture designs, décors, and clothing established a kind of cultural register for merchandising that informed public taste, resonating across cultures and classes.

Advertising and Merchandising Trends

Advertising theorists increasingly emphasized color’s importance as an aid to merchandizing in the 1920s. Matthew Luckiesh of the General Electric Company in the United States made a persuasive case:

Color may attract attention by being applied to the depicted product or package, to the trademark, to the text, to any selling point, or to its use. It may lend realism to the advertisement but also upon human figures or appropriate surroundings. It may attract attention by use in the border, background, printed matter, illustration or in other ways. Even a single note of concentrated color is emphatic. Doubtless the chief advantage of color is generally the faithful representation of the product or package but even for merchandise which cannot be illustrated in prominent colors, advertisements in color are effective. Color may be used to suggest or impress various qualities of a product such as attractiveness, refinement, dignity, smartness, delicacy, coldness, warmth, purity, cleanliness, solidity and ruggedness.29

These associative terms, connecting color with moods and sensations, signal a growing recognition of the commercial potential of color-conscious advertising, as Sally Stein has shown.30 They also reinforce the idea that personal preference is an important consideration, especially for female clothing. Paul Nystrom, a U.S. retail theorist in the 1920s, studied the market and suggested thinking about fashion and color in terms of classifications, such as those devised by Bullock’s department store in Los Angeles. Women were categorized into six personality types, including “artistic,” referring to “a type that may accept vivid colors, bizarre embroideries, eccentric jewelry…welcomes the revivals of Egyptian, Russian and Chinese motifs or colorings”; and the “picturesque…essentially feminine” woman, who preferred “soft, unassertive fabrics…no eccentric color combinations.”31 This approach was also evident in a number of fashion manuals designed to inform consumers about appropriate choices. Manufacturers were advised on product styling, such as in the 1929 campaign for Lady Pepperell, a linens manufacturer in Boston, for “Personality Bedrooms.” Lupe Vélez, a Mexican actress who became a successful film star in Hollywood beginning in the late 1920s, was used to advertise the range. Described as a “vivid personality” with “rich coloring,” her bedroom features green sheets and outer drapes contrasting with the red/orange bedspread and inner drapes (color plate 2.3). Customers were urged to send for a leaflet that would similarly help them match their personality to appropriate colors from a range consisting of peach, rose, blue, orchid, Nile green, shell pink, maize, and white.32 Photoplay, the magazine in which the advertisement appeared, published an article in the same issue titled “How the Stars Make Their Homes Attractive,” which detailed the domestic interiors of various film stars, including Doris Kenyon, Corrine Griffith, and Bebe Daniels.33 Doris Kenyon, described as a “real blond with golden hair and blue eyes,” had different bedroom colors and tones from Lupe Vélez. Rather than vivid red/orange and greens, Kenyon’s bedroom was “all feminine charm…pale green and pale rose…the walls are cream colored and the sheets a blush pink.”34 This reflects assumptions of ethnic stereotyping collapsed into the general category of “personality,” a theme we will return to later in this chapter. The consumer was advised to follow these examples by choosing colors selectively in the bedroom, using “Lady Pepperell sheets of a becoming color that best expresses you—precisely as you express yourself in choosing clothes.”35 The collapsing of divisions between intimate, interior domestic spaces and dressing up for the outside world is a striking feature of contemporary discourses. Using stars to advertise fashions was a shrewd move; they became intermediaries who conferred credibility on the products, much as Bourdieu observes regarding the legitimizing function of catwalk models in more recent times.36

Being conscious and knowledgeable about color was advocated as a must, particularly for the modern woman, across a range of publications relating to the home, dress, and advertising. Their democratizing rhetoric advocated that color expertise should be available to all, as one contemporary American manual advised: “In order to develop the expression of your character, of your personality in your dress, develop your taste. Continually study colors and designs, textures and effects, with your practical color and figure needs in mind. You do not have to be an artist to pick out a sketch from a fashion magazine, and change its lines and color scheme to suit your own complexion needs and type of figure.”37 Advertisers unlocked the mysteries of color harmony, selling the “aesthetic of the ensemble” so that one new purchase promoted another in a cascading effect: a new item of furniture, carpet, or even clothing depended on its coordination with an existing or new color scheme.38

These initiatives were encouraged in the United States by high-profile commercial institutions such as the Textile Color Card Association (TCCA), founded in 1915. As detailed in chapter 1, the disruptions to international trade caused by the First World War opened up space for the American synthetic chemical industry to prosper. The TCCA developed two key strategies to assist the business community in the exploitation of new chromatic initiatives: forecasting color trends and providing color consultancy services. The TCCA’s professionalization of color consciousness aimed “to record the colors of everyday fashion and to distribute this information widely, in line with the Taylorist belief that experts had a moral obligation to devise cost-effective practices that would benefit the common good.”39 The rhetoric of color consciousness was highly invested with a sense of national mission, as Margaret Hayden Rorke, the TCCA’s color expert and public advocate, articulated in a speech to the New York Editorial Conference in 1928: “The temperament of a nation is reflected in its color sense…. The more we train and develop our color sense applying it to our everyday life in our dress, our home, our industries as well as our arts and crafts the greater we shall become as a nation and centre of culture.”40 The language used by the TCCA was steeped in contemporary discourses around color. As early as 1922, the TCCA was pronouncing: “What we need is really to have a ‘color consciousness’ developed in our culture; this will then open up the unexplored fields of color expression and appreciation. Color can then become another medium of expression through which we can relate our own minds with those of others, and by which we can gain a much wider knowledge of the world around us, as well as extending our conception of its meaning and purpose.”41 Hayden Rorke’s annual report in 1926 made an interesting musical analogy to how the fashionable ensemble demonstrated “color rhythm” from hats, clothes, and accessories.42 Appreciation for variation in color accents, harmony, the role of pastel shades, color complements, and their impact on consumer psychology underpinned the organization’s activities throughout the 1920s.

The TCCA’s major contribution was the introduction in 1915 of its Standard Color Card of 110 basic shades.43 Swatch examples of colors were produced to advise manufacturers of appropriate colors for hosiery, shoes and leather, woolens, crayons, and other goods. In addition, forecast cards, designed to anticipate new seasonal accents in a small group of colors, offered greater variation than the Standard Card. The card for fall 1922, for example, featured a red named “salvia” that looks very similar to one named “spark” on the fall 1923 card.44 Some color names were fairly obvious in their object associations, such as a “strawberry” red; others were more obscure, such as “ophelia” for a pink shade and “titania” for a reddish pink, colors that have no obvious chromatic link to the Shakespearean characters they are presumably named after.45 This approach of naming colors after fictional and nonfictional characters was questioned in the press: “We have no reason to suppose that Ophelia was particularly partial to that shade. Then there is the Cleopatra blue, very near a royal blue, and the Rameses blue a shade darker. Why Cleopatra and Rameses any more than Salome and Herod, and why not any other color in the spectrum?”46 A rose named Ophelia, however, demonstrated a similar shade, so it is possible that the TCCA had this in mind.47 Hayden Rorke explained the rationale behind the naming of colors:

With its method of color names, and system of numbering, which give identity and personality to every tint and shade, the silk buyer is offered a fund of reliable color information as well as a helpful and simple way of matching and ordering colors. How attractive, descriptive, and interesting are these names! With them, one can wander in imagination through the realms of romance, history, and art, or dip into the story of jewels, flowers, or mythical lore. In spite of Avon’s Bard, there is much in a name, and the Association gives careful thought in baptizing its chromatic children. The merchandising value of a name is given first consideration for the name that tells a story, appeals to the imagination, or helps to visualize the color, is the one which helps to sell the fabric.48

This openness to flexibility within a system designed to simplify and stabilize choice demonstrates how, in competitive markets, fashion products were nevertheless subject to the fluctuating demands of novelty. This somewhat paradoxical situation required the TCCA to always appear to be one step ahead of trends, so that by changing color terms for textiles and materials for the products available in the market, it could make colors appear to be different from season to season even if they actually looked similar. This strategy required understanding and even, as one report argued, education, particularly for men asked to purchase particular shades by their wives.49

Aloys Maerz and Morris Rea Paul in 1930 published a Dictionary of Color “to serve as a common ground for the proper appreciation of all existing terms.”50 This comprehensive manual arranged 7,056 different colors into seven hue groups using names compiled from sources including the TCCA and various manufacturers. The lack of consistency in color nomenclature for clothing frustrated their desire for standardization:

The tendency in the change of styles in clothing has from very early days been largely responsible for the introduction of definite styles in color for coming seasons, and with them always appeared new names. The names apparently need not necessarily describe the colors but must only possess sufficient oddness to impress themselves on the mind of the layman, for therein lies the sales value. Of the various names so conceived, few are remembered by the following season, but some unfortunately continue to persist. Careful study, however, by the writers has failed to reveal, save in a few instances, any indication of the common continuance of a name unless that name possesses some enlightening term that will be instrumental in conveying to the mind of another some suggestion of the color’s identity.51

This rather dismissive opinion of fashion as an unscientific, disruptive force in the quest toward color standardization links the Dictionary of Color to contemporaneous trends identified in chapter 1. In their advocacy for the “proper use” of color, Maerz and Paul were inclined toward tracking color terms that were used consistently, giving the impression of progress toward “serious color recording.”52 Like later examples of racialized and politicized color terms—including the British Colour Council’s standardization in 1934 of “nigger black,” which subsequently became “nigger brown” and was listed into the 1950s—the Dictionary of Color also reveals prevalent assumptions around naming that demonstrate how color is “a discourse of race, skin tone.”53 The TCCA’s spring season for 1923, for example, named a very dark brown-black “Congo,” and in 1926 “plantation” was dark brown, even though neither the geographical area (Congo) nor the location (plantation) was necessarily associated with the color, other than the racial overtones that the pairings imply. “African brown” appeared the following year.54 This theme was evident earlier with “Negro” listed in the Dictionary as being named a color in 1915.55 Inventing terms to refer to colors was clearly far more than a descriptive activity, exposing the ideological predispositions of those in a position to pronounce, codify, and disseminate information about color. The idea that understanding color required education opened up a space for naming practices that were in many respects prejudiced. Consumers were nevertheless addressed with discourses of empowerment: to know about color enabled you to make more confident choices about how you dressed, decorated your home, and made sense of the ever-increasing number of commercially available colors.

Professional services were established in a similar spirit of unlocking the mysteries of color, so that manufacturers and consumers could be confident about their choices in a rapidly developing and chromatically rich commercial market. Many manufacturers and retailers joined the TCCA and took advantage of independent specialist advisory services such as that established in New York in 1927 by Tobe Collier Davis, reputedly the first professional fashion stylist in the United States.56 She was representative of the 1920s trend for women to occupy senior positions in a range of institutions involving color expertise. Margaret Hayden Rorke’s key role at the TCCA is another example, as is the work of Hazel H. Adler, who established a consulting business based on the Taylor System of Color Harmony to advise manufacturers from the motor industry to suppliers of kitchens.57 In the UK and elsewhere, women were also assumed to have advanced skills of color acuity, including Grace Cope, “a great authority on the psychology of colour,” who covered international developments in civic color for the “Townscape Campaign” launched by Colour, a London-based magazine that advocated greater consciousness in color design in cities.58 Beatrice Irwin was a British engineering expert in color lighting with interests in theater. Her work was known in the United States, where reports recorded her views on color’s profound effects on health, clothes, and houses.59 Dorothy Nickerson was a color scientist who joined the Munsell Color Company in 1921 and in 1927 went on to work for the Department of Agriculture, where for many years she held a top, highly specialized position as a key scientist working on fields including colorimetry and standardization of light sources.60 She was a founding member of the Inter-Society Color Council (ISCC) in 1931. The ISCC’s purpose was to coordinate the activities of leading technical societies relating to “the description, specification, and standardization of color and promoting the practical application of this knowledge in science, art, and industry.”61 While Irwin and Nickerson were less typical in their roles as women involved in color science rather than culture or psychology, they were nevertheless also a product of the world of opportunity created for women by color developments in the twentieth century. The rise of Technicolor’s Color Advisory Service, headed by Natalie Kalmus, toward the end of the 1920s was thus part of a wider trend of employing women as color experts in a range of contexts.62 These appointments somewhat challenged essentialist conceptions of color science as being primarily a “masculine” domain, as the breadth of expertise extended to accommodate the drive toward product differentiation in a number of fields, from agriculture to fashion.

The work of the TCCA and ISCC represented a desire to be less dependent on German and French expertise in synthetic chemistry and fashion design. The historic reputation of Paris as the center of haute couture persisted, however, influencing ready-to-wear garments across Europe and America.63 As we have already noted, the Exposition des arts décoratifs signaled the centrality of Paris to contemporary design, manufacturing, and fashion. Margaret Hayden Rorke toured Europe in the summer of 1925, visiting France, Britain, Switzerland, and Italy. She reported that her trip had three major objectives:

First and primarily, to establish special contacts in Paris, through various sources, that would supply us with information pertinent to our needs, and enable us eventually to build up a more extensive color fashion service for the benefit of our members. Secondly, to meet as many of our foreign members as was possible in so short a time; to make a general survey of the color trend, and its adaptation by the leading textile producers, and fashion creators, as well as the interpretation and application of color at the Exposition of Decorative arts and other art influences. And, last but not least, to meet and establish contacts with trade associations, Chambers of Commerce, and other important industrial factors, so that we could open new channels and create interest in our promotion of color standardization and the American cards.64

Rorke’s visit was highly influential in Britain, where her seasonal color forecasts and trend reports were consulted by businesses and manufacturers. In 1928, the Bradford Dyers’ Association proposed the formation of a TCCA-style committee “to consider and prepare ranges of shades for general use.” The result was the incorporation, in August 1930, of the British Colour Council Ltd, modeled on Rorke’s aim to influence the textile and fashion industries as well as public taste.65 As well as influencing European initiatives, Rorke learned much from her overseas travels. As discussed later in this chapter, after seeing The Phantom of the Opera (Rupert Julian, U.S., 1925) in Paris, Rorke was inspired to name a specific color “Phantom red,” and in 1928 the fall season color card was dedicated to France in celebration of the anniversary of Romanticism. This theme indicates respect for European culture and design in spite of rhetoric that emphasized American commercial independence.66 Sixteen “evening hues” were inspired by nineteenth-century French painting.67 A TCCA leaflet paired Romanticism with femininity as “the synonyms of fashion,” associating both with emotion, passion, and individualism.68 The use of such gendered language, however, implies more than admiration for French creativity. In her report, Rorke conversely aligns America with the serious “masculine” business of dominating international commerce through color standardization. In this case, her knowledge of dominant rhetorical positions on color was used to strategic advantage.

The Fashion Film

Film played an important role in the dissemination of Parisian fashions, as well as in advertising the latest designs, products, and color trends of the 1920s. A report on the activities of the T. Eaton Company, Canada’s largest department store chain, for example, details how the company’s buyers in Paris selected garments by designers including Paul Poiret, Bernard Madeline & Madeline, Worth, Jeanne Lanvin, and Jenny and Lina Mouton, and then filmed them on Parisian models. The films were shown in Canadian stores several times a day for a week to audiences that exceeded five hundred. The report notes: “The general consensus of opinion among American houses is that this is the best method of showing the season’s fashions in an authoritative manner…. They state that when French garments and hats are shown on American and Canadian women the Parisian touch is sometimes lost and that our women want to see models as they are worn in Paris even though they do not imitate them.”69 Although no further information is given other than that “a direct lumiere process of film photography” was used, some of the films were in color.70

Clothing and fashion were striking subjects for film color and spectacle in the silent era. Marketa Uhlirova has remarked how “the two quintessentially modern industries of fashion and cinema courted each other, resulting in a variety of direct, and regular, interactions that were sustained throughout the twentieth century and continue today.”71 Fashion’s visual sumptuousness provided a theatrical sense of spectacle in early actuality films and then in newsreels and cinemagazines. Colored films further enhanced the appeal of new designs for consumers while drawing attention to the quality of particular coloring methods, as with the Pathé-Revue stencil-colored newsreels that were produced throughout the 1920s. As Hanssen has pointed out, these films advertised clothes but are also fascinating for their display of décor, design, and social milieu more generally.72 Stenciling was an appropriate color process to celebrate the chromatic vibrancy of clothes, wallpaper, furniture, flowers, accessories, and settings. This exemplifies the integrative trend referenced earlier in this chapter toward the creation of a total artistic composition, with color occupying a central role. At the same time, the newsreels also deployed cinematic form astutely to emphasize, through close-ups and angled shots, particular details of the garments, shoes, hats, and accessories as well as the models. Hanssen observes: “The display of clothes and of women wearing them is represented in these films through a dynamic use of distance and framing, from long shots of models placed within specific surroundings to close-ups and extreme close-ups fragmenting the body and giving visual access to (often multi-colored) details of the garments: embroidery, textures, etc.”73 With an emphasis on depicting the upper classes and celebrities, the newsreels also advertised aspirant lifestyles and social mobility. Color and fashion consciousness were themselves linked both to economic capital—as the clothes being advertised were often expensive, even if their styles could be adapted for cheaper, ready-to-wear manufacture—and to the cultural capital their acquisition and imitation conferred on the purchaser and wearer.

The Pathé-Review fashion films were included as featured items in Eve and Everybody’s Film Review, the cinemagazine launched in 1921 that ran in the UK until 1933. The popular Fashion Fun and Fancy series was primarily aimed at women patrons, although men would also have seen them as part of the supporting film program for a feature film.74 An examination of the films shows how, in the fashion items, stenciling accentuates different fabrics, highlighting details such as shimmering, sequined gowns, the contrasting hues of silken textures, and examples of luxury footwear. The movement of the models ensures that gowns are showcased from multiple perspectives. Color differences are highlighted through contrast, as in one film in which each of the models walks toward the camera and off-screen, enabling a closer view of each gown to be achieved without cutting to a close-up. This choreographed effect was enhanced by a pale, pleated curtain in the background that the models stood out against. In the final shots, they assembled to show how the dresses benefited from the addition of silk capes and flowing outer garments.75

Another film, Belles of the Bath, showcased swimwear, including bathing hats. Filmed at Chiswick Baths, London, the close-fitting cloche-like hats in particular were exquisitely stenciled, with four women modeling their respective chromatic contrasts of white, red/maroon, pale green, and gold/yellow. Each hat was embellished with motifs, as shown by close-ups, and the detail on the bathing suits was displayed by shots of the women climbing down stairs to the pool.76 The suits resemble the bathing costumes by French designer Patou, rejecting older, more cumbersome swimwear in favour of minimal, androgynous styles. Outdoor activities were increasingly popular in the 1920s, and it was important for sportswear to be practical while aiming for a streamlined, athletic look. The sportif style promoted by Chanel crossed over to casual clothing worn by both sexes.77 One woman in Belles of the Bath is shown in a peaked “jockey cap,” and an intertitle advises viewers to go for an imitative approach to explain a bird emblem on one of the swimming costumes: “If your best boy is a flyer—wear a corresponding motif.” Chanel’s launch of the “little black evening dress” in 1926 popularized black as a flattering color that made bodies appear leaner and more athletic while connoting sophistication and elegance. In a further move toward standardizing women’s fashion, American Vogue’s advertising compared Chanel’s modernist designs to the streamlined forms of Ford automobiles.78 The nonconstricting, mass-produced versions of Chanel’s clothes indeed gave women the physical freedom symbolized by sleek, black enamel automobiles and “epitomized the practical modernity of the New Woman.”79

Gaumont Graphic newsreels also feature numerous fashion items. The ingenuity behind the staging of fashion on-screen is demonstrated in one case in which a model sitting at a dressing-table and looking into a mirror examines a hat with a decorative feather. To ensure that the hat is the focus of the image, the camera’s angle avoids showing the mirror’s reflection. Instead, the exquisitely stenciled hat is in the center of the frame and the audience is encouraged to admire it, as does the woman shot in medium close-up. We finally see her trying on the hat, shown in greater detail from an angle that reveals more of the back and how the material of her dress matches the hat in coloring (pale green) and similarity of lace embellishment. The ensemble is completed with the addition of a shawl with a decorative flower fastened on the front. Thus, in a very short film, the essential details of the hat, dress, and accessories are fully displayed, without the distractions of a mirror image that the staging nevertheless included as part of the performance.80 An Eve’s Review film, Fashions in Hairdressing, includes a more realistic mirror effect to demonstrate the full dimensions of various hairstyles but still uses close-ups and focus to accentuate the model rather than her reflection.81 Full-length mirrors are used in many fashion films so that both back and front of a dress are visible.

Other films similarly exploited particular shots to enhance the desired fashion address. The Shoe Show, a film informing viewers about which shoes are most appropriate to be worn at different times of the day, is largely made up of close-ups.82 On occasion, however, the women modeling the shoes are shown in long shot, again demonstrating the ideal of “matching” clothes and accessories, before a close-up followed by an intertitle that includes quite detailed information about “attractive combinations,” such as for “Manon” evening shoes with sequins, brocade, satin, beads and diamanté. The emphasis on textural detail is important in this example, because an understanding of colors, fabrics, and materials was all part of the desire to present products as constituent parts of an artistic creation, involving expertise and tips that consumers could pick up from the films. The use of close-ups for shoes and more intimate items such as undergarments provide an additional titillating function because, as news films, Eve’s Review films did not have to be submitted to the British Board of Film Censors. The shots thus provided both sartorial and sexual spectacle, a fact that the films took full advantage of in witty intertitles that on occasion addressed “Adams” accompanying their “Eves” to the cinema.83

As with the choreographing of movement, with models moving toward the camera and appearing to walk out of the frame, the use of perspective was an important element of the screen performance and staging of fashion. When the presentation took place in a grand house, furniture and wallpaper would generally be on display as well as clothing. On occasion, it was not entirely clear which took precedence, and within a film this could change from scene to scene. In Fashions in Colour (1925), for example, a model in a drop-waist flapper dress, with its sleeveless top colored ruby and a ruched golden skirt, stands in the foreground at the right of the frame so that an open doorway in center-frame reveals a plush sofa, almost as if this is as important as the gown being displayed. The deep perspective is emphasized because in a previous shot several women were visible through a doorway lounging on the same sofa, implying that this is an inhabited space.84 The impression of fashion as a “lived” experience was thus evident in the films, as women were photographed in different situations—having tea, talking, arranging flowers, and modeling clothes for each other.

Since most of what is shown was “high fashion,” in Eve’s Review films featuring the work of haute couture designers, including Jeanne Lanvin, Lucile Ltd, Lucien Lelong, Maison Worth, Maison Redfern, Joseph Paquin, and Revile Ltd, direct marketing is not always present. Instead, the women simply model the latest fashions to communicate a sense of new styles, pleasing color combinations, textures, fabrics, and how to match accessories such as hats, bags, shoes, and gloves with garments. Far from being wooden clotheshorses, the models often appear with animated expressions, clearly enjoying the experience and thus giving the films an air of familiarity, even though the fashions on display were far from affordable. As Emily Crosby has noted, women viewed the films in a spirit of “copy culture,” so that the examples of glamorous high fashion might be adapted to some extent: “Plenty of anecdotal evidence exists to suggest that cinema audiences did copy their favourite styles from films.”85 Fashions seen on-screen were therefore not inaccessible. Rather than aim to produce exact replicas, however, adaptations were often designed to suit women’s everyday requirements, a point made by Hollywood designer Gilbert Adrian when advising women how to adapt dresses seen in films.86 Women’s magazines provided tips on how to copy the latest fashions at home. One film trade paper suggested that expertise in fashion design could be communicated to audiences eager to learn tips: “Fashions in hats, handbags, sunshades, footwear and other feminine vanities will flicker across the screen, and we may yet see the arrival of the period when women will descend on kinemas equipped with notebooks in which to record the ideas they glean from these animated fashions.”87

Advertisements relating to clothing, however, were aimed more at the everyday consumer. One such example is Changing Hues (1922), a humorous film produced in the UK by the London Press Exchange. The film used stencil, hand-painted, and tinting effects in a spectacular way to advertise Twink Dyes, manufactured by Lever Brothers, who sponsored the film. The title is hand painted in vivid colors of literally changing hues of red, yellow, blue, and green (color plate 2.4). The film begins, however, in black and white with an artist (described as “an artist/lover,” played by Albert Jackson) painting a picture of a young woman (Jean Millar), telling her that while he likes her wearing gray or white clothes, “in pink you’d be adorable!” A scene follows using a stencil effect of her looking into a mirror and seeing what her gray dress would look like in pink. Approving of the imaginary color change, she despairs that all her dresses are gray. An intertitle tells us that her housekeeping money is earmarked for the children’s clothes, referring to the younger siblings she cares for along with her father (Burton Craig). Her desire for color is intensified when her father asks why she does not wear “pretty colors” like her mother used to. An intertitle then informs us that a shopping expedition intended “for the children only, results in something unexpected for herself.” Looking into a shop window advertising Twink Dyes, the woman peeks inside to spot brightly colored clothes, the film now using stenciling to show them in pink/mauve, green, orange/beige, and blue (color plate 2.5). The sales assistant demonstrates swatches of different colored dyes until the desired pink shade is found and presumably purchased. A hand-painted intertitle follows, “Goin’ thro’ the dye,” and we see her begin the dyeing process at home, the film once again reverting to black and white.88 The laborious task is shown, including pink (“the pink of perfection”) added by stenciling to show the fabric changing color in the bowl before the final garment is revealed and then paraded for her father to appreciate. The next frames are of sheet music with lyrics based on a popular song, “Gin a bod-y meet a bod-y Goin’ thro’ the Dye,” first seen painted orange and then with streaks of green and blue. The film’s final shots are of the woman dancing in her pink dress, presumably to the song, with her younger brother in a blue sailor suit and her sister wearing a yellow dress, clothes that have also been dyed with Twink, shown for us to admire from both front and back (color plate 2.6). Finally, the artist/lover joins their joyful celebration of the chromatic transformation of the clothes.

This film is remarkable for its wit and charming engagement with the increasing range of color products available to the consumer. Color’s transformational potential is also vividly present, as the woman is able to adapt her entire look as well as that of her siblings by using the dye. The narrative hints that color is also good psychologically, implying that the gray worn after her mother’s presumed death is associated with grieving and that purchasing the dye can restore the colors worn by her mother once again to the household that has become sad and drab. Also, at the start of the film, the artist in his enthusiasm for color states that in pink she would be more attractive. In addition, the fact that all of the clothes have been dyed with the housekeeping money advertises that the dye is not too expensive and that existing garments can be transformed. In all these ways, the film conveys clearly that life, and reflexively cinema, is enhanced by color. The hybridized forms are applied strategically, featuring the visually arresting, chromatic aberration of several intertitles with their hand-painted colors appearing to seep into each other almost like an abstract painting, as well as the stenciled pink dress shown at first as a figment of the woman’s imagination and then for real once she has dyed the clothes. This astute progression adds to the film’s advertising prowess, making the point that color of the imagination can indeed be realized through the wonder of synthetic dyes.

The display of fashions was not confined to stenciling techniques. In 1926, Sonia Delaunay made L’Elegance, a color fashion film using a French lenticular additive process known as Keller-Dorian that was coinvented by Rodolphe Berthon, whose son was a friend of Robert and Sonia Delaunay.89 The film demonstrates a selection of Delaunay’s designs and at first appears to be a typical fashion short, featuring a woman pulling scarves one by one out of a box, but it becomes increasingly abstract as it progresses, in line with French Cinéma pur aesthetics of the time. The scarves are variously patterned, but with Delaunay’s characteristic penchant for zig-zag, harlequin, and striped geometric patterns. As the woman decorously removes the scarves, their silken fabrics create a swirling sensation as they cascade into her lap. Orchestrated in this way, the geometric shapes do not seem static; within the frame, they are moving spectacles of color and form. The film’s emphasis on vibrant simultaneous contrast is also of particular note. In one shot, a woman robed in a black and light orange contrasting-square dress stands in front of a tall gradated blue disc, rotating it. In another, a woman in orange garments stands in a long shot against a contrasting light blue background; she strips the orange skirt and top off, revealing a layer of blue garments beneath, and as she does, she moves to screen left to stand against an orange backdrop, again playing on the abstract potentials of simultaneous contrast to heighten color effects in fashion and the lived environment. At the end of the film, two fashion models and a man in a dark suit stand in front of vertical blocks of draped fabrics, which show more of Delaunay’s designs. One of the models takes off her fur-lapelled coat to reveal a black-and-white dress with the hard-lined, geometric hallmark style of Art Deco.

Another of Delaunay’s fashion films, Mademoiselle Y (1920), similarly uses models to show off her fashions in front of draped fabrics that reveal the entirety of the design before it has been cut to make dresses. In a single shot, this provides a graphic illustration of the interrelationship between designs, fabrics, and their creative adaptation for fashion. The film opens, in a striking variation of this technique, with a woman standing sideways in front of a large color wheel showing shades of blue. As the wheel gradually turns, she stretches out her arms to follow its movement, rotating in one direction and then the opposite. Her black-and-white patterned dress contrasts with the wheel, yet the image communicates an idea of how color theory is integral to design; the movement of both wheel and figure suggest a work of fashion in progress. Beyond these fashion films, Delaunay was also famous for incorporating her chromatic innovations into the Dadaist costumes she did for Tristan Tzara’s plays, as well as for collaborating on feature films with Marcel L’Herbier, who used her fashion designs in his film Le vertige (The Living Image, France, 1926), and with René Le Somptier in Le p’tit parigot (The Small Parisian One, France, 1926).

Whereas Delaunay and the Pathé-Revue films rarely featured celebrities, in 1925 an American company, the Educational Film Exchanges, publicized McCall Fashion News, a new series shot in two-color Kodachrome. Kodak had been experimenting since 1912 with applying Kodachrome to motion pictures. In 1922, test shots were taken in Fort Lee, New Jersey, and in Hollywood of stars including Mae Murray, Hope Hampton, Guy Bates Post, and Gloria Swanson. Their cooperation had been secured largely through Jules Brulatour, an influential film executive and sales director at Kodak who had extensive connections throughout Broadway and Hollywood. The reels were exhibited to mark the grand opening in 1922 of the new Eastman Theatre in Rochester, New York, and a color demonstration reel toured selected venues in the United States. Hampton, who married Brulatour in 1923, was singled out in particular as a popular star with “exceptional coloring”—red hair, a pale complexion, and blue eyes—for Kodachrome. As Natalie Snoyman notes, this accorded very much with prevailing conceptions of beauty that privileged Caucasian skin tones.90 Building on this success, Brulatour persuaded the McCall Publishing Company and the Educational Film Exchanges to produce and distribute the McCall Fashion News films from January 1925. The first of these films featured Hampton modeling clothes designed by Paul Poiret, Jeanne Lanvin, and Jacques Doucet in Paris Creations and Paris Creations in Color. Hampton often traveled to Paris and was instrumental in selecting the clothes she demonstrated in the films, which were distributed widely and greeted enthusiastically by the press. The McCall company was best known for publishing McCall’s, a popular women’s pattern magazine, and was proud of bringing Parisian fashions within the reach of women who it hoped would use the patterns to make dresses that would otherwise be too expensive for them to buy. Designers whose patterns were made available in this way included Chanel, Vionnet, Patou, Moyneux, and Lanvin. McCall’s also published patterns based on the fashions worn by Hampton in the Fashion News films. The patterns were printed in color to “guide the dressmaker in the finishing details accurately.”91 In 1926, Hampton went to Europe to purchase the latest Parisian gowns, which she wore for the next installments of the McCall Fashion News series, which this time featured “ornate” settings. The trend for advertising clothes as part of an appropriately opulent ensemble that extended to décor and furnishings was clearly evident here. The series was produced until the end of 1927, and the films were screened regularly in American cities, often in anticipation of the sale of spring styles and as the accompanying short before feature films targeted at female audiences, including The Dressmaker from Paris (Paul Bern, 1925), That Royal Girl (D. W. Griffith, 1925), and Mademoiselle Modiste (Robert Z. Leonard, 1926).92 There was a productive commercial and educative symbiosis between the films, the sale of McCall’s patterns, department stores, and local newspapers. Above all, the series was an interesting experiment in demonstrating how films could “cascade” the advertisement of both color and fashions.

Although the development of two-color Kodachrome was frustrated by technical and financial problems and competition from Technicolor, the McCall Fashion News films influenced Fashion News, a biweekly series produced from 1928 to 1931 by Fashion Feature Studios, Inc., and filmed in two-color Technicolor.93 Film actresses—“virtually every star in the film capital”—modeled clothes that were described very precisely in the intertitles.94 Corliss Palmer is seen wearing, according to an intertitle, “a striking feminine chapeau in wavecrest green with Pascecan ecru lace trim, in large flare style.” The TCCA’s spring card for 1929 includes “wavecrest,” confirming that the films directly referenced the latest trends. Technicolor was cognizant of the TCCA’s astute commercial strategy of seasonal color forecasting and skilled in exploiting color’s dual role in advertising the process as well as clothes. As Snoyman observes, the company was careful to ensure that the clothes featured in its films emphasized the greens and reds that most suitably showed off the narrow range of the two-color process.95 The intertitle’s use of “chapeau” further accentuated the U.S. absorption of French couture while promoting up-to-the-minute designs. In another film in the series, actress and pioneer aviator Ruth Elder models an “ensemble pour le sport,” a red coat with an embroidered lining and collar over a straight white dress with red trimming. Elder’s reputation as a “new woman” clearly influenced the clothing choices made for her, the red contrasting with white to resemble sportswear but with additional visual interest provided by the exquisite embroidery seen as she turns around to display the coat’s lining. The film also features Raquel Torres, showing her driving an automobile before getting out to show off a two-piece felt set, hat and bag designed to match with appliquéd felt flowers “for early spring wear.” Once again, the fashions on display are identified as appropriate for the modern, mobile woman (color plate 2.7). The films were widely distributed; in 1930, for example, the Hollywood Filmograph reported that Fashion News was releasing three hundred first-run prints in leading theater circuits throughout the United States.96 George W. Gibson, president of Fashion News, promoted the films assertively, adding sound commentaries by fashion experts by July 1929 and signing a long-term contract in March 1930 with Fox West Coast theaters for exclusive releases.97 One report implied that the fashions were designed in Hollywood, referring to it as the “fashion center of the world,” while other reports stressed the availability of the clothes shown in the films for purchase in local stores.98

In 1926, Colorart Pictures, a prolific producer of Technicolor shorts, released Clothes Make the Woman, a one-reel fashion film.99 Starring Sigfrid Homquist, a Swedish actress working in Hollywood, the film tapped into the idea of clothes as a passport to social mobility via a transformation narrative in which a poorly dressed young woman ends up modeling the latest Parisian fashions.100 Distributed quite widely through the Tiffany exchanges, contemporary reports noted the film’s novelty: “Heretofore fashion pictures just paraded models in front of the camera, but in this latest Colorart production there is a human interest story in it which will appeal to those of both sexes.”101 Although the reproduction of color on-screen was by no means stable at the end of the 1920s, Technicolor’s confidence in fashion advertising is indicative of the company’s ambitions to dominate the market into the sound era.

Fashion and the Fiction Film

While the short and promotional film market was clearly much utilized for showcasing fashions in clothes, furniture, décor, etc., fiction films presented further opportunities, both directly and indirectly. A striking example of an item of clothing playing a central narrative role is Der karierte Regenmantel (The Checkered Raincoat, Max Mack, Germany, 1917), a German comedy about mistaken identity (color plate 2.8). A husband suspects his wife of being unfaithful when he sees her walking out with an unknown man. The woman he sees in the distance is in fact his wife’s friend who has borrowed her distinctive checkered coat to meet her fiancé; the assumption of adultery is based purely on seeing the coat. The coat’s centrality to the plot required it to be visually distinctive in a tinted and toned film. Its graphic, geometric design of pale squares highlighted against darker, heavy fabric, is shown against two different tints and tones: orange/reddish brown for interior shots when the coat is being tried on and admired, and yellow when worn outside. The comic situation exploits how the coat practically conceals the identity of its wearer, an impression accentuated by its voluptuousness and high fur collar, especially when worn with a hat. It stands out more prominently than any other object, its striking appearance paradoxically working as a disguise and leading to erroneous judgments.

It is unusual to find an item of clothing playing such a dominant role in a fiction film, yet clothes were made to stand out in other ways that connected them with contemporary advertising cultures. As Louise Wallenberg notes, cinema acted as a “seductive shopping window,” not only “displaying fashion and fashionable goods to its spectators and would-be consumers” but also “as a fashion show or fashion spread in which its stars are involved in displaying fashionable costumes.”102 Color could only intensify this impact. This was the case in Love (1920), an American film directed by Wesley Ruggles that reviewers criticized on first release in the UK as “a thin and unconvincing story, redeemed, only by the sympathetic acting of the star, Louise Glaum.”103 Pathécolor was added to prints for a subsequent rerelease, and the trade press enthused about the addition of color as a welcome experiment: “Exhibitors who number a good proportion of women among their patrons have got something here on which they can make a special appeal. The colouring and texture of the various dresses are unusually fine, and from the point of view of women patrons the film is an animated fashion book, for Louise Glaum wears numerous exquisite creations.”104 Thus, what was at first more or less written off as a poor box-office attraction was given a second life through the addition of color, even if in the opinion of the trade press, the story was still lacking in narrative value.

As we have already seen, film stars were often used in advertising campaigns, and designers dressed stars such as Jeanne Lanvin, who was working with Mary Pickford.105 Cecil B. DeMille was one of the first U.S. directors to surround himself with experts from the fields of costume, interior décor, and set design for “modern photoplays” such as For Better, For Worse (1919), Why Change Your Wife? (1920), and The Affairs of Anatol (1921)—comedies that “perfected a display aimed at the fashion-conscious.”106 His use of color in many of these films was also innovative. As Sumiko Higashi has noted, “for advertisers, the streamlined Art Deco design that DeMille used so inventively with the Handschiegl color process in The Affairs of Anatol in 1921 became a signifier of modernity.”107 The Affairs of Anatol was an extravaganza of modern design, Orientalist-inspired décor, ornate fashions, and color. Adapted from Arthur Schnitzler’s 1893 play Anatol, it follows the quests of Anatol de Witt Spencer (Wallace Reid), a wealthy newlywed, to reform women he thinks need rescuing. This tries the patience of his wife Vivian (Gloria Swanson), who becomes jealous of the time he spends on various adventures. These involve women being tempted, for various reasons based on necessity that Anton at first does not comprehend, by jewels and money. A showcase for consumerist desires, three episodes, particularly the first and last, involve the conspicuous display of jewels, clothes, and other goods.

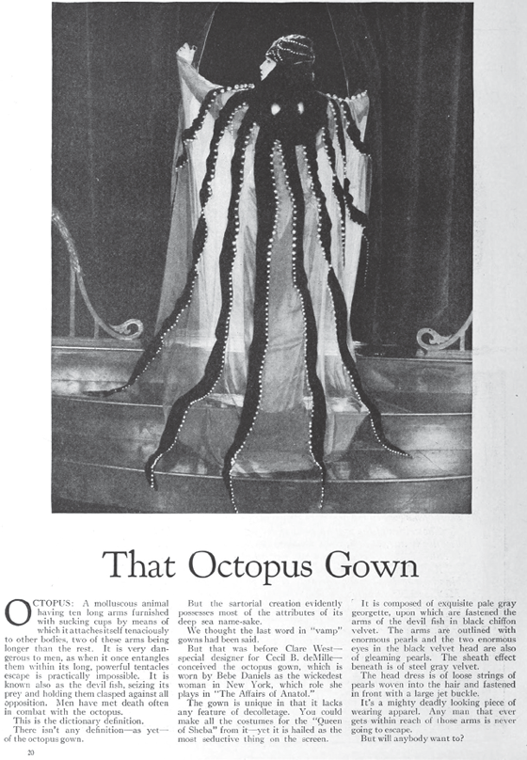

In one scene, Bebe Daniels wears an “octopus gown” by Clare West, a designer whose work with DeMille represented a significant move toward greater professionalism and sophistication in Hollywood film costuming.108 The visually striking gown was composed of “exquisite pale gray georgette, upon which are fastened the arms of the devil fish in black chiffon velvet. The arms are outlined with enormous pearls and the two enormous eyes in the black velvet head are also of gleaming pearls. The sheath effect below is of steel gray velvet.”109 The very specific referencing in a fan magazine of fabrics such as georgette, a thin, semitransparent and dull-finished crêpe fabric named after French dressmaker Georgette de la Plante, demonstrated precision in costume description and implied that readers would both appreciate and understand a high level of sartorial expertise. The film’s costumes were clearly inspired by the style of Erté, the Russian-born stage designer and illustrator who emigrated to France in 1912 and subsequently worked with Paul Poiret. Although Erté did not go to Hollywood in an official capacity until 1925, when he designed for a number of MGM films including Ben Hur (1925), The Mystic (1925), and Paris (1926), West’s gowns were similar to Erté’s illustrations at the time that The Affairs of Anatol was in production, particularly his use of black velvet, pearls, and theatrically inspired cape designs.110 In the film’s final section, Gloria Swanson wears a dress with a distinctive zigzag pattern that was used by Erté. Even accessories that feature in the film—most strikingly, an umbrella made of translucent fabric, thus showing the women gathering underneath it—is reminiscent of a contemporary Erté design. In this instance, “copy culture” appears to apply to film costumers like Clare West, even though she claimed that Hollywood led Paris in fashion.111

The octopus gown was celebrated as one of the film’s attractions. It was worn by Daniels as Satan Synne, a seductive cabaret artiste referred to as “the most talked of woman in New York.” She becomes the focus of attention for Anatol when, estranged from his wife, he visits a risqué rooftop establishment where Synne is performing. We learn before he does that she is desperate for money to pay for an operation for her invalid husband, wounded in the war. As his condition becomes critical, Synne is forced to present herself to Anatol as a vamp, a ruthless seductress who invites him to the Devil’s Cloister. This decadent locale is coded as a brothel with “outlandish art direction, where the hedonistic drives of consumerist excess are mocked through the details of Synne’s orientalist boudoir.”112 Inside her boudoir, the octopus design of her attire is fully shown from behind when she rises to embrace Anatol. The impression of an octopus enveloping him is created by a cape with floor-length, tentacle-like strands of black fabric adorned with giant, iridescent pearl-effect beads and connected by a diaphanous, translucent fabric. Her headdress, also black and with giant beads arranged in an octopus-like shape, completes the spectacular impact of the ensemble. As Fischer has noted, such visually excessive imagery resembled sea-creature motifs in Art Nouveau jewelry while in this context conveying “morose overtones of strangulation.”113 The scene is toned in deep orange, and color accents while not being necessary to show off the black cape with its distinctive beading. Color is used more boldly, however, for a close-up a few moments later, through the Handschiegl method on a pink monogrammed cigarette (color plate 2.9)—or something stronger, as indicated by Anatol’s surprised expression when he inhales it. This is the first of three items of temptation Synne offers Anatol, the others being perfume (“Le Secret du Diable”) and the spirit d’abstinthe. The last is not highlighted in green, an effect one might have expected, but its corruptive reputation is indicated when, after drinking it, Anatol catches sight of his reflection in a mirror and is shocked to see a skeleton.

Art direction is credited to Paul Iribe, a Parisian designer who had previously collaborated with Jacques Doucet and Paul Poiret. Emboldened with resultant touches of continental flair, the film represented the epitome of DeMille’s Jazz Age texts, featuring, as Lucy Fischer has noted, “ostentatious levels of consumption both as spectacle for visual appropriation and as a showcase that set fashion trends in apparel and interior decorating.”114 Many of the clothes and commodities seen in the films became readily available from manufacturers in the late 1920s, furthering the symbiotic relationship between cinema and merchandising. The opulent bathrooms seen in DeMille’s cycle of comedies, for example, tapped into the transformation that domestic bathrooms were undergoing in the United States during the decade as new ranges of standardized materials, fixtures, and fittings became available.115 The Affairs of Anatol combined elaborate décors to display Art Nouveau touches in the Spencers’ apartment, including a floral-patterned Japanese screen leading to Vivian’s bedroom and elaborate floral motifs on lampshades and stained-glass windows, as well as modernist-influenced reflective surfaces such as an electrically operated sliding mirrored door.116