The industry is rapidly becoming color conscious. With the major problems of sound successfully solved, the studios and color processes are now bending their efforts to the further development of color cinematography […]. Color is in the ascendency as sound was last year, and 1930 will be marked with outstanding achievements in this field.

—Jack Alicoate, ed., Film Daily Yearbook (1930)

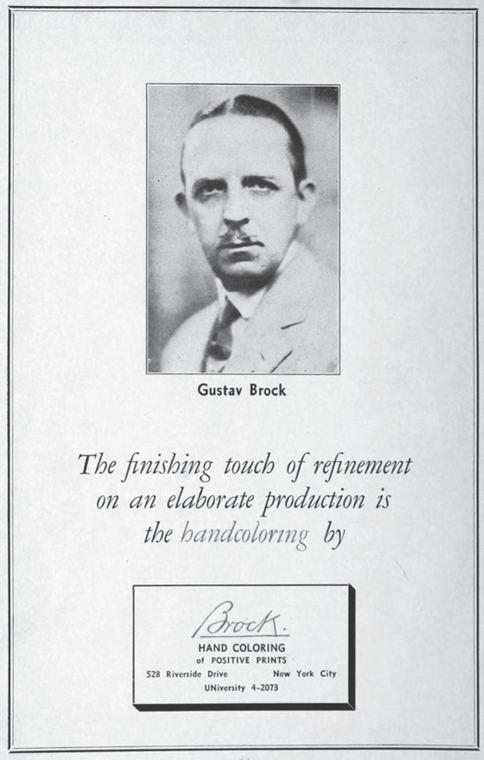

In May 1931, at the spring meeting of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, the organization held a series of one-day symposia, the first being a Symposium on Color and the second a Symposium on Sound Recording.1 At the turn of the decade, these two arenas were at the forefront of technical and aesthetic innovation in cinema, and particularly at the Symposium on Color, the delivered papers provide seminal perspectives not only on what was to come but also retrospectively on the achievements of the prior decade. The event was chaired by Kenneth Mees, director of the Research Laboratory at Eastman Kodak, and papers were delivered by Harold Franklin on color style, Joseph Ball on Technicolor, Russell Otis and Bruce Burns on Multicolor, William Kelley on Handschiegl, and Gustav Brock on hand coloring. Most of these papers were published afterward in the Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, and they have since become crucial texts for subsequent histories of color cinema. Collectively, they attest to the radical changes that occurred at the end of the 1920s: the adoption of synchronized sound systems along with the technical strides made by photographic color systems and the transformation of applied color processes. The papers presented at the Symposium on Color provide a striking case study of how technical developments could transform the structure of possibilities within the cinematic field at a time when many in the film industry optimistically predicted that black-and-white film would soon be a thing of the past. For Pierre Bourdieu, such changes are indicative of the ways in which technical revolutions transform what is aesthetically possible as new technical agents enter the field, shifting power relations and stylistic norms to form a new mode of color consciousness.2

Among the many transformations that sound technology brought to cinema are the ways in which it affected the technical and stylistic application of color in the moving image. Indeed, the sound transition in cinema occurred during a parallel transformation of color culture—what the Saturday Evening Post referred to in 1928 as a “chromatic revolution” in mass society.3 As similarly noted in the first issue of Fortune in 1930, “In this post-war period of broken precedents, of weakened traditions, it is not surprising that the old chromatic inhibitions should be shaken off and that the American people should gratify its instinct for color by bathing itself in a torrent of brilliant hues.”4 Such predictions about an increasingly chromatic future were overly optimistic, as the effects of the developing Depression in fact weakened color’s dominance in the 1930s. The iconic black-and-white documentary photographs from the era by photographers such as Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans exemplify this monochromatic dominance. Thus, the Depression in the economic field stifled, to a degree, chromatic innovation in the cultural field. However, this was also the era of Whoopee! (1930), Becky Sharp (1935), The Wizard of Oz (1939), and Gone with the Wind (1939), as well as the wondrous advertising experiments by experimental filmmakers such as Oskar Fischinger and Len Lye in Gasparcolor and Dufaycolor. Such fantastically chromatic worlds serve as opposite, escapist refractions of the decade that gave new life to the prismatic aura associated with the preceding Jazz Age.

As we have shown, the chromatic modernity of the 1920s was evident internationally in fashion, interior design, commodity and artistic production, and most certainly in the cinema. The Color Committee of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers noted in 1930, “The demand for motion pictures in color which began in the summer of 1929 continues without abatement. It is reported that some of the larger producers would willingly change back to the black and white pictures but say that the demand for color pictures by the public is so insistent that they do not dare to change.”5 In light of the subsequent history of color film—it was not until the 1950s and 1960s that color usage actually exceeded and then dominated film production—the Color Committee’s predictions were overly optimistic, fueled in no small part by the success of the transition to sound. As John Belton has theorized regarding the relation of sound and color during the era, histories of different technologies take inherently dissimilar shapes, even if it is nearly impossible not to assume synchronicities—as in the assumption that the transition to color would occur with the same speed as the sound transition.6

A remarkably incisive article in the Observer of London in 1929 posited this parallel between sound and color innovation: “It is only the advent of the talking film that has made the advent of colour film inevitable. America is seriously concerned, for the first time, with the production of something better in colour than cheap picture-postcard painting, and the elimination of black-and-white photography, like the elimination of silent photography, is now little more than a matter of time.”7 Indeed, such comparisons come easily because of the long entwined history of color and sound, originating in antiquity through notions of synesthesia, as discussed in chapter 3. The combination of color and sound in film occurred in numerous configurations after the emergence of the medium at the end of the nineteenth century. The earliest cases involved sound accompaniment paired with screenings of some of the first hand-colored films—for instance, at Koster and Bial’s music hall in April 1896, where two hand-colored films were presented with musical accompaniment, the Leigh Sisters’ Umbrella Dance and a serpentine dance.8 Other early examples include the hand-colored Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre works of the early 1900s that were synchronized with wax cylinder soundtracks, and the stencil-colored sound films of Gaumont’s Phonoscene productions in the 1910s.9 While attention has been paid to these early color and sound films recently by Lobster Films, by the Cinematheque française, and at Pordenone, there has been less focus on the interrelated changes that occurred between sound and color at the end of the 1920s. In particular, we are interested in how many of the applied coloring techniques of silent cinema—that is, hand coloring, stenciling, tinting, and toning—were orphaned to an extent at the end of the 1920s, both because of the coming of sound and because of developments in photochemical and dye-transfer photographic processes such as Technicolor. However, obsolescence is not the only trajectory, for as we will see, many of these techniques and technologies were adopted anew by the developing sound cinema.

A majority of what follows focuses on chromatic innovation in Hollywood and draws primarily from the U.S. trade press. Such an account of the era inevitably must deal with the rising ascendency of Technicolor, from its two-color phase into the three-strip era. Our aim is not to dismiss this trajectory, but rather to contextualize it within the international transformation, surge, and decline of various color technologies at the end of the 1920s. Thus, we also stretch beyond the U.S. market to think about the global flows of technical and aesthetic innovation across the cinematic field at the turn of the decade when sound technologies were disrupting established distribution routes across linguistic borders. This contextual emphasis is in part because of the state of the film industry at the time: after the end of the First World War, Hollywood consolidated its hegemony throughout most of Europe and, as a result, was able to support much of the research and development into color that was occurring at U.S. firms such as Technicolor and Eastman Kodak. In contrast, studios such as Pathé Frères in France that had dominated color production before the war fell into financial hardship in the 1920s and were less able to fund extensive technical innovation, particularly as sound technology introduced a host of expensive technical issues for color application—for example, shooting with motorized rather than hand-cranked cameras and silencing them for sound—just as the worldwide Depression began.

If much, but certainly not all, of the technical development of color cinema was occurring in the United States by the end of the decade, another crucial factor was the cultural hegemony of American modernity in the global imaginary—the discourse of “Americanism” specifically in relation to how Hollywood came to exemplify it.10 It is for these reasons that the previously cited article in the Observer of London looks specifically to America for a solution to the color question at the end of the 1920s, citing primarily U.S.-produced films in its account of recent chromatic innovation—specifically, the Technicolor films The Toll of the Sea (Chester M. Franklin, 1922), Wanderer of the Wasteland (Irvin Willat, 1924), The Virgin Queen (Roy William Neill, 1928), and Broadway Melody (Harry Beaumont, 1929). The article does note the strengths of the Prizmacolor British film The Glorious Adventure (J. Stuart Blackton, 1922) and the French-Italian stenciled film Cirano di Bergerac (Augusto Genina, 1923), but overall the focus is on U.S. invention.11 Color innovation was certainly taking place in Britain, France, Germany, and elsewhere at the end of the 1920s, as detailed below, but the ascendency of U.S. technologies at the time cannot be overlooked. Still, to place U.S. color development in a global context, ascendency was not a given: Technicolor barely survived a slump in business in the early 1930s, because of its own failed technical performance in the late 1920s as well as the shifting taste cultures of the Depression. To trace these various currents, we begin with a discussion of photographic color and then turn to applied coloring techniques in the sound era. As we will show, the intermedial legacies of the period cast a prismatic afterglow not only on the 1930s but also on the decades to follow.

Photographic Color and Sound

An article in the International Photographer in 1929, John W. Des Chenes asks:

Sound—or color? Or both?

Will one survive the present era in which producers are fighting frantically to supply Mr. John Public and family with a cinema “kick”? Will the other fade into the inglorious background of oblivion? Or can the two be successfully synchronized…. Whatever the answer—this much is evident: Producers are beginning to display a healthy interest in color cinematography.12

Inherent in Des Chenes’s account is that, in trade-press discourse at the time, color cinematography, as combined with sound, meant primarily photographic color rather than applied color. As we will see, applied coloring techniques were also used with sound, on their own as well as integrated into photographic color systems—they just received less critical attention. Still, the conceptual change regarding how the technical base of color was understood was significant and firmly grounded in the industrial transformation of the cinematic field in the 1920s.

Numerous photographic color technologies were being developed around the world at the end of the 1920s, and Des Chenes goes on to elaborate specifically in the U.S. context on the strengths of the Vitacolor system, along with Multicolor and Technicolor. Technicolor proved to have a long and successful technical and corporate life, while Vitacolor and Multicolor did not and are little remembered today. However, it is crucial to focus not just on industrial successes, for often the technologies, techniques, and styles that disappeared tell us more about an era than its official victors. This was as true for the 1920s as it was for early cinema and also for our own contemporary media culture.

Multicolor and Technicolor were two-color subtractive processes that were increasingly in competition with one another. Herbert Kalmus, for instance, explained in a 1929 letter to Leonard Troland: “The thorn in our side with respect to getting business from Fox and Metro is that they are fooling around with a color process called Multicolor.”13 To counter this, Kalmus stressed that Technicolor needed to move as quickly as possible into three-strip production, the fourth Technicolor process. Three months later, as a backup measure, Troland noted in his research diary, in an entry on Multicolor, that Technicolor “should try to acquire some patents that will circumvent them.”14 Technicolor was better established and funded, with strong Wall Street backing, and as of 1928 had rolled out its dye-transfer process that was successfully deployed in films such as The Viking (1928) and Redskin (1929). Because a light-splitting prism was required to expose a Technicolor negative—splitting the light passing through the camera lens to expose two successive frames at once that were filtered as separate red and green records—special Technicolor cameras and camera operators needed to be deployed for filming. Not only were these cameras more expensive to shoot with, but it was relatively difficult to schedule them for filming in the late 1920s because Technicolor had a very limited number of cameras and crews available. Print processing was even more elaborate, and unfortunately erratic, as business ramped up with what was now Technicolor process #3. The negative was developed and the alternating color records printed separately onto positive prints, which were then used as dye matrixes to transfer ink onto a new filmstrip through the imbibition process, thus building the color image in successive dye-transfer layers. Illustrative of the ways in which applied coloring processes were adapted into photographic color, Technicolor’s method of imbibition was informed by the applied-color process of Handschiegl, which was itself developed intermedially from chromolithography.15

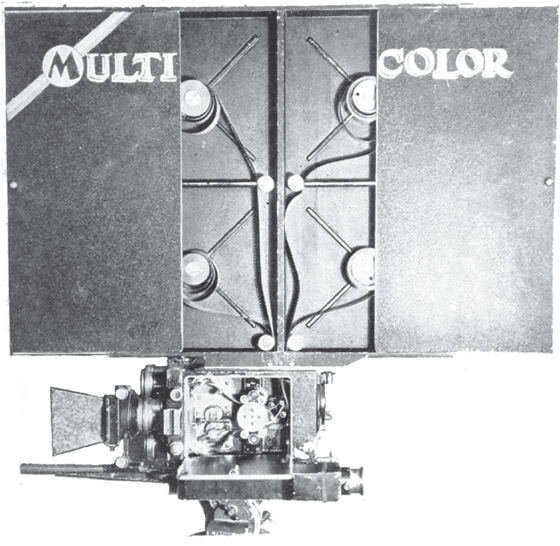

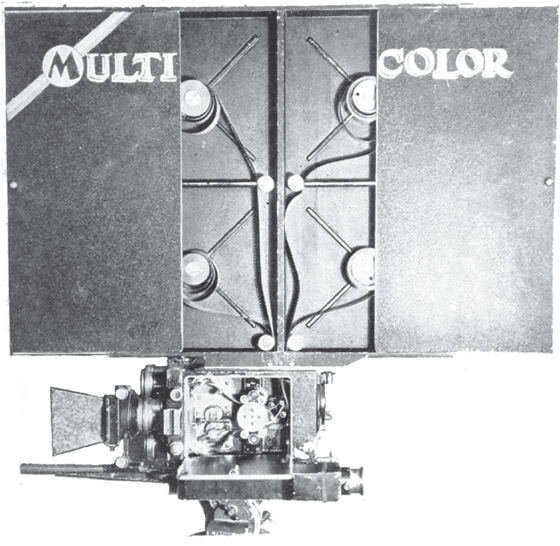

Multicolor was a newer system that William Crespinel helped develop after his work with Prizmacolor.16 It was a bipack system that combined two negatives, one orthochromatic nearest to the lens and one panchromatic beneath it, that ran simultaneously through a standard camera with modified film magazines, which any operator could handle. The orthochromatic stock recorded blue and green light waves (as orange and red are invisible to orthochromatic emulsion) and was treated with a tint dye to filter light passing through to the panchromatic stock beneath it so that only yellow, orange, and red light waves would be exposed on the second negative. The two exposed negatives would then be developed and printed on a double-sided positive, which was dye-toned on opposite sides in complementary colors (iron blue and uranium red) to produce the two-color positive image. Again, with this method, an applied coloring technique (dye toning) was adapted for the process. As Multicolor was meant to be deployed on normal cameras, as opposed to Technicolor’s special beam-splitting cameras, it was a more affordable mode of production; however, its optics were softer. Though a number of shorts were produced with this process, and a variety of color inserts were used in feature films, the process never took off for feature filmmaking, and the company folded in 1932.

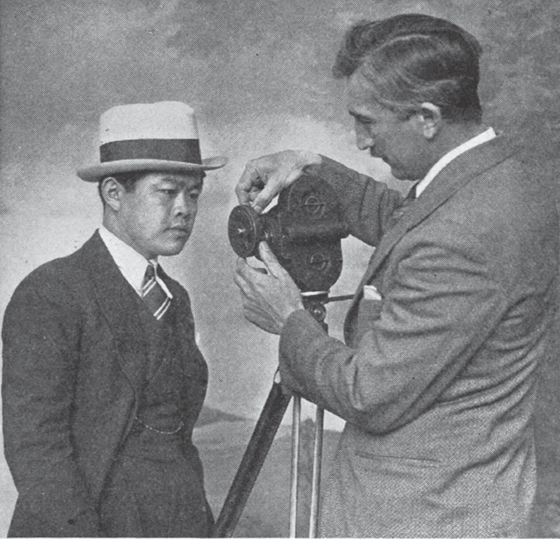

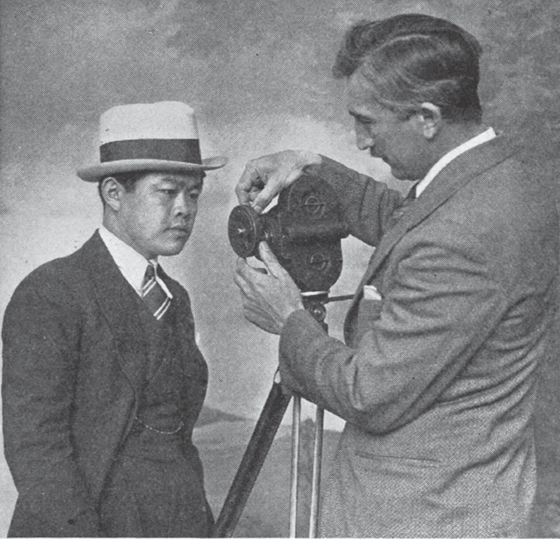

In contrast to Technicolor and Multicolor, Vitacolor was launched in 1928 as an additive system similar to Kinemacolor, in that it captured successive filtered frames on a black-and-white negative as red and green records. When developed and printed, the film could be projected back out through the same rotating colored filters to produce a two-color image. The filters were a simple lens attachment that could be used on standard cameras and projectors. Similar modifications had proved unsustainable for Kinemacolor in the 1910s, but Vitacolor purportedly took advantage of more advanced filters and panchromatic stock during filming and projection to produce a fuller two-color image that required less intervention than Kinemacolor.17 The process was developed by Max DuPont, a Hollywood cameraman originally from France. According to at least one biographical account, he was the son of Leon B. DuPont, “one of the foremost scenic painters of France and an officier d’académie,” from whom he learned “the science of color combination and harmony.”18 Despite the shared name, Max DuPont and Vitacolor were not affiliated with E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, the U.S. chemical conglomerate that was also producing color and black-and-white filmstock at the time through the DuPont-Pathé Film Manufacturing Company.19 Vitacolor could be used for 35mm filming and projection, but its larger appeal was in the amateur market, where it also functioned well on 16mm to much fanfare during the years it was in operation; its chief competition was Kodacolor.20 Vitacolor expanded rapidly at the end of the 1920s and made international inroads in the UK, Japan, and Shanghai, with Chinese American (later Oscar-winning) cameraman James Wong Howe showcasing the technology in East Asia.21 The company bought up many of the existing Prizmacolor patents and proceeded to file lawsuits against a number of its competitors for patent infringement—in a way foreshadowing high-tech patent litigation of today. With the company’s portfolio thus bolstered, Max DuPont sold his stock in 1930 to Consolidated Film Industries, which was not successful in developing Vitacolor further, and it soon largely disappeared from the public eye.22 However, Vitacolor continued its patent lawsuits—for instance, in 1936 against Cinecolor, which had taken over from Multicolor.23

Integrating these various color processes with new sound technologies was clearly a pressing issue at the end of the 1920s. James Layton and David Pierce, in their history of early Technicolor, describe a strong push to combine sound and color, particularly going into 1928 with the novelty of sound. They explain: “Sound also brought a new sense of reality to films, and this led to an appetite for the widespread adoption of color. Producers who had gambled on sound had little fear committing to a program of color musicals, before knowing whether audiences would respond at the box office.”24 Synchronized sound disrupted established codes of cinematic realism at the time, expanding the audiovisual relation of cinema, as sound theorists such as Michel Chion have theorized.25 This, in turn, proved lucrative for color companies such as Technicolor that were heavily marketing their processes in Hollywood, while also looking to expand globally. Herbert Kalmus explains:

By early 1929 all the important studios in Hollywood had become thoroughly sound conscious. This was a great help to us in introducing color. Prior to that, studio executives were loath to permit any change whatsoever in their established method of photography and production. But with the adoption of sound, many radical changes became necessary…. The studios were beginning to be color conscious.26

In other words, one disruption to the structure of cinema begat another during the sound transition, when established audiovisual norms were open to revision on multiple fronts. What had previously been dominant within the cinematic field—the silent-film style of applied coloring—got “pushed into the status either of outmoded or of classic works,” to apply Bourdieu’s theory of literary innovation.27 These dynamics around the transformation of the cinematic field reverberated in the trade press of the time, making the silent era seem like the uncanny shadow of Maxim Gorky’s early film criticism.28 As an article in American Cinematographer explained, “now that talking pictures are a reality, color helps carry out the illusion and makes one forget that he is watching a shadow. What the future holds in the way of color is a question no one can answer, but the wind is blowing colorwise.”29

Even with such changes to the cinematic field, color still coded a specific, generically, culturally, and often racially defined mode of realism that was deeply rooted in intermedial practices and cultural fields. Indeed, it is at moments of technical transition that medial and cultural connections often come to the fore to situate change. With regard to realism, as argued throughout this book, photographic color was not inherently aligned with the aesthetics of naturalism. Instead, in the late 1920s, color was used to code historical narratives like The Viking, to enhance indigenous and racialized locales in films such as Redskin, and to amplify the visual pleasure of female display; and of course it was most vibrant in the exemplar of the new audiovisual paradigm of cinema, the musical, which often combined all of these semantic elements. Simultaneously, there were narrative pressures placed on chromatic style. Harold Franklin at the Symposium on Color argued that color should merge with the background of a film: “When motion pictures can capture the blending hues of the spectrum so that they dissolve into the scene, so to speak—and not dominate the picture as has been the case in some instances in the past—then color will enhance the pictorial as well as the dramatic values in motion pictures.”30 Such emphasis on well-blended coloring has roots in cinema that date to the end of the first decade of the 1900s, when filmmakers began to subdue bright colors to work in harmony with narrative legibility; it is also in line with later Technicolor three-strip aesthetics, which coded color design to avoid visual distractions, particularly from the mid-1930s on. Such stylistic prerogatives, though, have always been fluid, depending on the context of the work.

Generically and sonically, Vitacolor was an outlier when compared to Technicolor and Multicolor, but it provides a useful example of the coded realism of photographic color at the time. Only a few fragments of Vitacolor material survive in the Earl Theisen Film Frame Collection at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, but as early announcements of the process suggested, it was certainly feasible to synchronize the process with recorded sound.31 The Exhibitors Daily Review explained in 1928, for example, that Vitacolor was “a new process of film manufacture embodying possibly sound and color photography”32 In accounts of Vitacolor screenings, though, synchronized sound is not mentioned. Instead, the films displayed were largely nonfiction: scientific and surgical films, as well as scenes of bathing women.33 Apparently, one of the first films that DuPont debuted to industry technicians was footage from the Santa Monica beach; according to a reviewer’s description, it relied heavily on the color process to amplify the visual pleasure of female swimmers:

At last, a hushed quiet came over the long room. The lights were extinguished and the projection machine set up a whine, which settled down to a low, rhythmic purr. A few fitting titles flashed onto the screen. Then a group of bathing girls appeared in one of the most amazing motion picture reviews I have ever witnessed. Every color of the spectrum was represented in the combined shades of their swimming suits. Not all glaring colors, mind you, but exactly as they would appear to the eye in reality—some “noisy,” others subdued. But the fact which impressed me most was that while one of the girls had red hair and wore a green suit and another along the line had on a red suit, yet neither of these brilliant colors persisted in the eye of the observer to draw his attention away from the other girls, any more than if he were peering at a row of “sunkist” specimens along Santa Monica’s ocean front. The flesh tints were exact, ranging from a carefully nurtured “peach and cream” complexion down to a deeply tanned skin.34

Even as the Vitacolor system opened new inroads for color in the amateur market, it still recapitulated long-standing tropes of chromatic culture—the association of color with female spectacle, which dominated the earliest color films of the 1890s, when hand coloring was often used to add glamor to the image of dancing women, as in Annabelle Whitford’s serpentine films for Edison. Vitacolor even promoted the young actor Mary Mabery as the “Vitacolor Girl,” recapitulating the promotion of the “Biograph Girl” of early fandom in the 1910s. In one photograph of Mabery, she stands opposite DuPont against a painted landscape, both wielding cameras with Vitacolor filters focused on the other, he with a 35mm, she with a 16mm—a plucky Vitacolor romance of dueling formats.35

Beyond female spectacle, DuPont promoted Vitacolor in line with his own artistic training, emphasizing connections between painterly practice, color theory, and physiological discourse: “color composition in color photography is as important as in oil painting.”36 He explained elsewhere that “the Vitacolor method impresses upon the emulsion of panchromatic film the various colors of the scene being photographed in substantially the same manner as the artist blends his colors in painting a picture…. So, knowing that to create color sensation is just a matter of proper vibration irritating the nerves of the eye, it is easy to understand that a certain vibration transmitted by a mechanical means and in synchronization with the receptive optical nervous system will create natural color sensation.”37 Such references to gender, aesthetic theory and practice, and science remediated the new color technology in the guise of the old, as Vitacolor took part in the transformation of the cinematic field of the day.

If the place of sound in the Vitacolor system was underdeveloped (even as it expanded the potential of color into the amateur market), this was not the case with Multicolor and Technicolor. A discussion of Multicolor in International Photographer in 1929 noted that a key feature of the process was its adaptability for sound cinema:

And a most important point to consider is the fact that with the Multicolor process sound can be recorded from the film itself. With the voice, or music or sound effects the result on the screen is identical with black and white. The sound track is an integral part of the film itself, is colored and is protected with a transparent coating which prevents abrasions and scratches to the sound track as well as to the picture itself.38

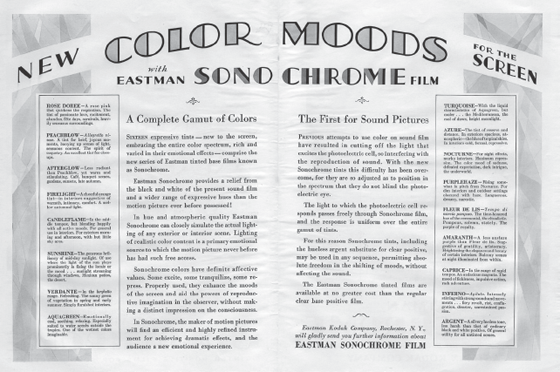

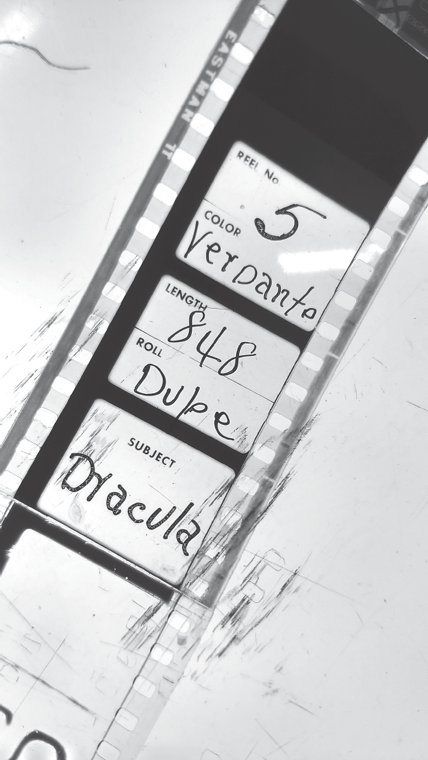

Similarly, in an advertisement in Cinematographic Annual in 1930, Multicolor promoted its ability to combine “color and sound-on-film in one process,” and stressed that its process would appeal to the growing “color-conscious” public.39 As we have discussed previously, color consciousness was a central aesthetic concept during the era across a wide range of fields, from scientific discourse to fashion manuals and educational curricula of the early twentieth century. At the end of the 1920s, it was invoked increasingly within the film industry, by Loyd Jones at Kodak and, most famously, by Herbert and Natalie Kalmus at Technicolor. In the same issue of Cinematographic Annual, the volume’s introduction references the notion in a long section on color (quoted in the epigraph to chapter 2), noting how color cinematography will affect intermedial taste cultures for fashion and home décor, helping establish a new color consciousness of color harmony among the public.40 Bringing color consciousness to bear on Multicolor’s approach to sound, the company was clearly attempting to promote itself in the context of the intermedial color boom of the time, noting in the same Cinematographic Annual advertisement that its color process was useful for “educational, industrial or regular dramatic films,” thus applicable cross-genre and cross-field, in keeping with the expansive understanding of color consciousness at the time. The educational emphasis makes sense also in the context of Multicolor’s first sound production, the 1929 Max Sennett short comedy Jazz Mamas, distributed through Earle Hammons’s Educational Film Exchanges—a company that, as the name indicates, had its roots in the educational market even though it quickly expanded into comedies in the 1920s.

As Hilde D’Haeyere has examined in detail regarding Max Sennett’s color-comedy work, Educational Film Exchanges promoted Jazz Mamas as the “first all-color, all-talking comedy,” and it proved to be mutually beneficial for both Sennett and Multicolor.41 The film is lost, but from reviews and advertising, it is clear that it was a series of musical sketch comedies, including Sennett’s famous “bathing beauties” and an “international detective” spoof featuring a variety of colorful national costumes. Sennett had already worked with Technicolor in producing two-color sequences for silent comedies, and he had also produced sound comedies in black and white. Multicolor offered a more flexible color technology than Technicolor, with its proprietary cameras and company-assigned cameramen; Sennett benefited from the flexibility, using Crespinel, the chief developer of Multicolor, in an advisory fashion. In return, as D’Haeyere, explains, “Sennett provided Crespinel with a practical test-case and studio facilities to complete the Multicolor process with sound-on-film.”42 Without the extant film, it is difficult to judge the success of the collaboration, though according to Russell Otis’s technical analysis of the process in 1932, Multicolor did have issues with adapting its process for sound because the soundtracks had to be printed and toned in either blue or red—on one side or the other of the positive print—because trying to print both sides would result in registration issues for the soundtrack.43 The photoelectric cells that read soundtracks were calibrated for black-and-white tracks, and this caused issues with volume and sound quality, though Multicolor found that placing the soundtrack on the blue-toned side worked better than on the red-toned one. Likely because of the poor sound, as well as general dissatisfaction with the color quality itself, only a handful of films were subsequently produced with Multicolor, including Married in Hollywood (Marcel Silver, U.S., 1929), The Great Gabbo (James Cruze, U.S., 1929), and Hell’s Angels (Howard Hughes, U.S., 1930). The company folded in 1932, and Cinecolor subsequently purchased its plant and patents and recruited William Crespinel to oversee its technical facilities.44 Cinecolor, as opposed to Multicolor, did much better in the 1930s by not competing with Technicolor head-on in terms of quality, instead providing an acknowledged lesser but more affordable alternative for lower-budget productions.

In contrast, the Technicolor Corporation moved into a position of relative ascendency at the end of the 1920s, as it successfully adapted its new two-color dye-transfer process to all major forms of soundtrack technology at the time—Western Electric sound-on-disc as well as Movietone’s and RCA Photophone’s sound-on-film processes. By 1928, Herbert Kalmus saw this as a crucial priority for the company, arguing in corporate correspondence:

If we do not get aboard the band wagon, we will soon be left behind…. It is only that we should arrange to have the existing synchronizing methods applied to color as well as to black and white; in other words, it is only the specific problems of our color method in connection with tone that I am advocating that we spend any money on. After a while everybody will have sound and the company who has color and sound will again be out in front.45

Technicolor was able to surmount the various issues that sound raised. However, the more pressing problem the company faced turned out to be a problem that it helped create. The surge in color productions in the late twenties overwhelmed Technicolor camera crews and printing labs, which could not keep up with the demand, and the quality of output suffered immensely, as Layton and Pierce have documented thoroughly.46 Kalmus explained:

During this boom period of 1929 and 1930, more work was undertaken than could be handled satisfactorily. The producers pressed us to the degree that cameras operated day and night. Laboratory crews worked three eight-hour shifts. Hundreds of new men were hastily trained to do work which properly required years of training.47

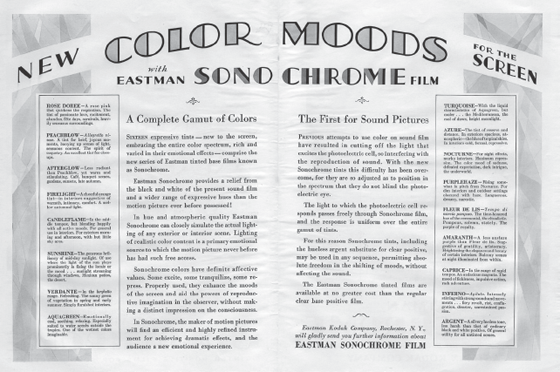

This, in turn, created openings for competitors such as Multicolor and also Eastman Kodak’s Kodachrome process, which Fox Film Corporation licensed in 1929 and rebranded as Fox Color—though all of these processes faced similar if not worse issues of scale and quality control than Technicolor did. Over the next few years, because of these problems as well as the added cost of color production at the onset of the Depression, the high demand for color passed. Meanwhile, the generic conventions of color for musicals, fantasy, and exotic locales persisted from the silent era into the three-strip period of Technicolor production, setting up the aesthetic and stylistic parameters that defined the classical era of color-sound design.

Because of the overcommitted nature of Technicolor’s position in the domestic market, its efforts were primarily U.S. focused at the time. In 1929, Kalmus did try to expand the company with new plants in London and Berlin, to make foreign-release prints cheaper and stimulate overseas color production.48 These plans fell through, though, as Technicolor’s resources were overcommitted. As Kalmus explained in a cable to his British collaborators at the end of 1930, “just now entire industry in slump and every would be competitor of Technicolor much worse off than Technicolor so what chances have they in London now.”49 It was not until 1935 that Technicolor was able to establish a coloring lab in Great Britain as Technicolor Ltd.50 In the context of these international developments, Technicolor’s genre-focused work in Hollywood in the late 1920s took on particular cultural and racial emphases that were both inward looking, with regard to the color-coding U.S. racial representation, and outward oriented in the context of Hollywood’s and Technicolor’s growing global sway. In other words, the confluence of racial and generic conventions in Technicolor productions served both domestic and cosmopolitan audiences, and this dual appeal is vital for understanding the company’s practices at the time.

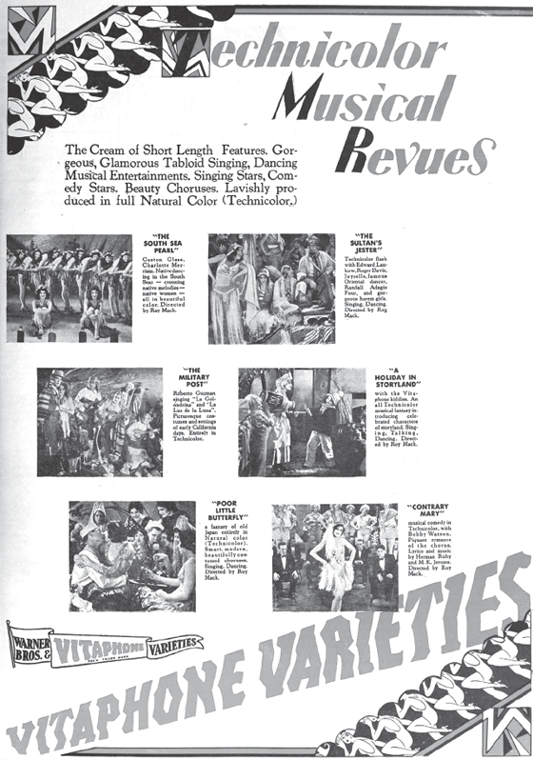

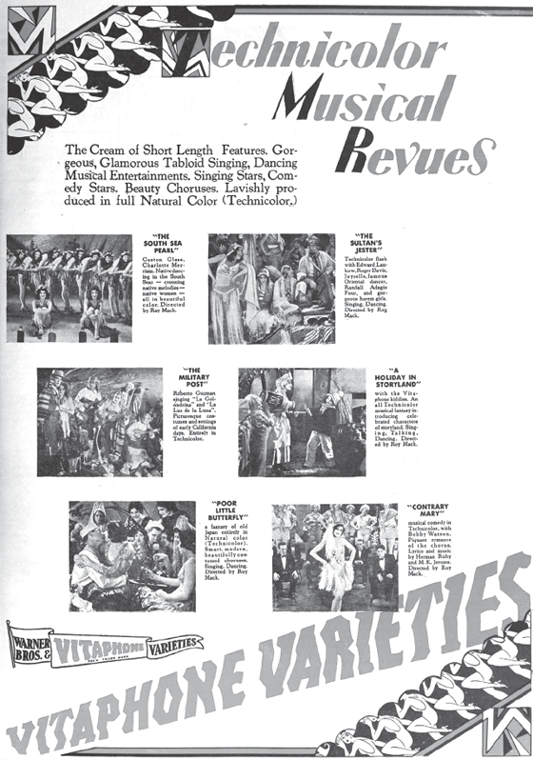

This dominance of generic and racial conventions can be seen in the Technicolor productions at the turn of the decade. In a 1930 Art Deco–style ad for Technicolor Musical Reviews by Vitaphone, for instance, four of the six promoted Roy Mack–directed shorts emphasize their exotic and Orientalist settings in Polynesia (The South Sea Pearl), the Middle East (The Sultan’s Jester), California under Spanish rule (The Military Post), and Japan (Poor Little Butterfly).51 As noted earlier, feature films such as The Viking and Redskin similarly deployed Technicolor to emphasize historical and exotic locales in conjunction with their soundtracks of music and effects. The Viking was Technicolor’s first all-color feature printed with a Movietone sound-on-film track; it was meant to demonstrate the company’s compatibility with sound through its newly unveiled dye-transfer process.52 With Technicolor producing and MGM distributing, Herbert Kalmus served as executive producer, while Natalie Kalmus, for the first time on a feature film, served as color art director through the company’s newly formed Color Control Department.53 Technicolor wanted to return to the success of Douglas Fairbanks’s The Black Pirate (1926) and showcase its dye-transfer process through another historical seafaring adventure. Given the technical and industrial importance of the production for Technicolor, it is significant that the film was staged mythically and racially as a national origins story of North America by Nordic-Anglo explorers. Set ca. A.D. 1000, it stages Leif Erikson’s voyage to North America and founding of the Viking settlement of Vinland, today known to have stretched from Newfoundland to northern New Brunswick in Canada. The film, however, erroneously centers Vinland further south in Rhode Island by making a temporal leap in the film’s ending coda to the 1920s where a Viking tower supposedly still stood while the “Star-Spangled Banner” plays on the soundtrack. (“Newport Tower” was in fact built in the mid-seventeenth century.) Leif Erikson was played by Donald Crisp, who also had a key role in The Black Pirate; Anders Randolf also appeared in both films. Additionally, Kalmus hired the screenwriter Jack Cunningham and painter and art director Carl Oscar Borg from The Black Pirate. Borg in particular was vital in both films, developing their color designs and imbuing them with a cosmopolitan flair; he famously helped Fairbanks replicate the look of Howard Pyle’s illustrations in the earlier film.

For The Viking, Borg also took an intermedial approach, drawing from the look of nineteenth-century Nordic Romanticism for the set and costume design, which the soundtrack also picks up. The color in the film was praised as a “work of art,” even as its plot was generally found lacking.54 In particular, as Arne Lunde argues, the film’s invocation of Romanticism can be seen in the introduction of the character Helga Nilsson, the female protagonist played by Pauline Starke with dyed red hair.55 A Viking princess who later becomes the wife of the kidnapped, turned Viking, Anglo-Saxon Lord Alwin, she is introduced unceremoniously as she is thrown from a horse. Nonetheless, she embodies the film’s attempted Wagnerian aura: her costuming in early scenes is anachronistically adorned with a winged Valkyrie helmet and copper breastplate, and when she flies off the horse in her first scene, the score alludes to “The Ride of the Valkyries” from Wagner’s Ring cycle. The coloring also works to bring out these operatic and Romantic elements through bold clashing colors: Helga’s red hair matches her short red skirt and copper skin, and together these contrast sharply with her blue-green cape. The coordinated clash of color pairs with the operatic swells of the score, which also amplifies the visual spectacle of the close medium shots of Helga to emphasize her heaving and barren upper chest.

Numerous other elements of set design and landscape in the film also rehearse a Nordic Romantic aesthetic, exemplified, for instance, in a later scene’s depiction of rocky Greenland: a snowy and mountainous painted backdrop in green-blues and whites sets off the scene’s reddish-brown Viking fort. A battle that shortly breaks out in the fort could be a scene from the conclusion of the German-Norse Nibelungen-Niflung, in line with (if not as bleak as) Fritz Lang’s adaptation in Kriemheld’s Revenge (Germany, 1924). Through these various generic references, the Technicolor hues work in the film to illuminate a mythic and racialized past, the Nordic and Anglo discovery and settlement of the Americas. Helga and Alwin ultimately stay behind to found the new world of Vinland, while Leif Erikson departs for home. Thus, as a racialized origin story that still resonates with white nationalist delusions today, the film imagines the European settlement of what would become the United States at the turn of the last millennium, deepening a sense of old world cosmopolitanism that was meant cinematically to play well both domestically and in Europe.

Color and race also factor prominently in Technicolor’s Redskin, which, like The Viking, was produced with music and sound effects but no dialogue—though song vocals performed by Helen Clark were used on three of the reels, synchronized through the Vitaphone sound-on-disc method. Filmed in both Technicolor and black and white, the film was an ambitious undertaking, with extensive location shooting in the picturesque Canyon de Chelly in Arizona and the Valley of the Enchanted Mesa in New Mexico. Given the ambitious filming schedule, Technicolor set up a mobile lab to support the three-month production.56 The black-and-white footage was used for foreign-release prints to cut down on costs, and presumably also because the narrative itself was U.S. centric and may not have had as much appeal for foreign distribution. Thus, it was only the U.S. domestic version that was released primarily in Technicolor, except for portions set in an Indian boarding school and subsequently at an eastern U.S. college that were filmed in black and white and tinted brown, likely with Sonochrome filmstock. In the U.S. version, this split between tinted and Technicolor sequences thematically matches a narrative split in the film between the subdued Anglo-American-dominated spaces and more colorful indigenous ones. Such a division affirms a generic and racialized convention for color design in which supposedly primitive spaces, bodies, and subjectivities are more closely aligned with saturated colors, whereas modern spaces are desaturated, ethnically white, and associated with Western European rationality. Technicolor’s earlier Toll of the Sea (Chester M. Franklin, 1922) is a parallel exemplar of such a racialized chromatic logic, as detailed in chapter 2. Such chromophobic divides were also combined in the film with the use of redface by the film’s nonnative star, Richard Dix, who was darkened up with brown makeup to play the part of Wing Foot, the Navajo protagonist of the film.

Despite these problematic racial ideologies and practices of color, the film itself is in fact surprisingly sensitive about issues of race, racism, and the politics of Native American assimilation. Redskin was produced in the wake of the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, which granted citizenship to Native Americans, and especially of the Meriam Report of 1928 (officially titled “The Problem of Indian Administration”), which was highly critical of the U.S. Department of Interior’s horrid oversite of Native Americans reservations. Specifically, Redskin picked up on the report’s trenchant critique of Indian boarding schools, which since the late nineteenth century had forcibly removed children from reservations to segregated, and often poorly managed, boarding schools that attempted to assimilate the children into mainstream American culture. As the film shows through the plight of Wing Foot (named for his speed), who is taken from his Navajo village as a child and only returns after abandoning college, such practices left many Native Americans lost between worlds, never accepted in mainstream society yet too alienated from their indigenous heritage to be easily at home again on the reservation. The film is particularly critical of the brown-tinted Indian school that Wing Foot is taken to, where, after leaving the Technicolor world of his village, he is stripped of his bright native clothing and redressed in denim jeans and a button-up shirt, and his long hair is cropped short. Finally, he is cruelly whipped into submission for refusing to salute the U.S. flag.

After a quick passing of years, the film subsequently shows Wing Foot’s successful entry into college somewhere in the eastern United States on a running scholarship. Still tinted brown, the sequence continues the critique of education with a striking portrayal of Jazz Age racism. Wing Foot is invited to a college dance after he has won a prestigious race for the school. The setting is an Art Deco night club with big-band jazz playing on the soundtrack, and Wing Foot arrives appropriately dressed in a tuxedo. A young blonde woman, who had earlier invited him to the club, pulls him onto the dance floor in an attempt to get him to perform an Indian war dance, which she demonstrates stereotypically by whooping and hopping around. The other dancers and the band join in, with a shift in the score to an Orientalized, klezmer-driven version of a war dance. Wing Foot uncomfortably, if politely, watches the racist parody unfold until the woman’s boyfriend, who has become jealous of her attention to Wing Foot, intervenes to pick a fight. The man’s colleagues grab Wing Foot from behind as the man punches him in the face, telling him he bet on him at the race just as he would on a racehorse, while another man explains that if they did not need Wing Foot for the running team, he would not be tolerated at the school. Through this vicious confrontation, Wing Foot realizes he was mistaken to think he could ever fit into the supposedly tasteful and restrained white world, so he returns to the Technicolor lands of the Navajo reservation.

Wing Foot’s return, though, is anything but smooth. He has become modernized, wearing a Western brown suit, and his father rejects him for not coming back looking like an Indian. However, even after changing into native garb, with a bright red headband and black shirt, he still cannot fully assimilate into Navajo culture. He rejects the tribe’s medicine-man rituals as old-fashioned, insisting that they should also incorporate modern medicine into their ways. For this profession of cultural hybridity, he is formally kicked out of the tribe, thus fitting racially into neither the monochromatic nor the Technicolor world of the film. The film resolves itself in color, or rather through a certain rejection of color and an embrace of blackness, for in a deus ex machina moment, Wing Foot discovers oil on reservation lands and is able to stake a claim to it, which resolves all of the narrative’s conflicts. As he dips his hand into the petroleum seep, the color of the oil corresponds tactilely to the blackness of his shirt (color plate 6.1). Of the impending oil income, half will legally go to his tribe, who happily accept Wing Foot back as a member; the other half he promises as a dowry to a nearby Pueblo tribe where his fiancée Corn Blossom resides, in Romeo-and-Juliet fashion, thus settling cross-tribal conflicts. In retrospect, the resolution of the film through the black oil of global capital is not necessarily a happy conclusion, but what is productive is the film’s critical stance vis-à-vis Native American modernity. Critiquing both the inherent hypocrisy of Jazz Age racial divides and an unwavering and Romantic embrace of indigenous tradition, the film is forward looking and grounded firmly in Native American identity, yet open to the modern, globalized world. The film’s final scene shows the Navajo and Pueblo tribes, made rich by the abundance of oil, meeting in the rocky desert among covered wagons as they set off to found a new, tolerant, intertribal Native society, with Wing Foot and Corn Blossom as their new royal family now dressed in the Technicolor reds of Native patterns. In its depiction of this new Edenic desert society, the film appropriates and rewrites Anglo-American myths of manifest destiny, imagining what an indigenous utopia might look like. By routing this through the generic and racialized conventions of color at the time, the film opens productive, if unsettling, dialogue about cultural hybridity in ways that resonate ambivalently with the saturated designs of the Arab Gulf states of today.

Parallel racial issues are also central to King of Jazz (1930), Technicolor’s and Universal’s ambitious all-talking and -singing musical revue of the year, directed by John Murray Anderson, which we discussed briefly in chapter 3. The film has recently been meticulously restored, and James Layton and David Pierce have also published an in-depth book on the film, examining in detail its production, reception, and recent restoration.57 We do not aim to replicate the detail of their analysis here, but the film does bring into focus the ways in which color and race coalesced at the end of the decade in the context of both the U.S. and global markets that the film was distributed in as a multilingual production. One of Carl Laemmle Jr.’s prestige pictures at Universal (along with All Quiet on the Western Front), the film was meant as a platform to showcase the musical prowess of Paul Whiteman, the renowned “king of jazz” of his day. Banking on Whiteman’s fame, Universal signed a lavish contract with him, offering 40 percent of the profits with a guaranteed $200,000 payout.58 Running over budget to more than two million dollars, it was Universal’s most expensive film to date, exceeding even All Quiet on the Western Front. Unlike the latter film, which was profitable, King of Jazz ultimately lost approximately $1.3 million for the studio.

The budget problem largely grew out Universal’s struggle to find the right narrative framework for the production. As part of his contract, Whiteman had final say on the script, and Universal went through numerous drafts that failed to gain his approval. The film also saw the exit of one eminently skilled director, Paul Fejos, in favor of Broadway stage director John Murray Anderson. Whiteman also insisted that the film use primarily prerecorded sound played back during filming, to improve the quality of the sound recordings. In the end, the film moved forward with a near bottomless budget as a loosely connected revue structured as a “scrapbook” of acts to showcase Whiteman and his band without interweaving narrative threads. However, by the time of release, such musical revues had saturated the market, and particularly coming in the wake of the stock market crash, the film failed to catch with U.S. audiences in particular. Despite its weakness at the box office, the film is worth examining both for its remarkable color design and for its problematic racial narrative about the origins of jazz.

Jazz in the 1920s had many connotations. At its core, it grew out of the African American ragtime and blues music of New Orleans and circulated in speakeasies and nightclubs around the world from Harlem to Paris. If the origins of jazz are associated with African American musicians such as Louis Armstrong, King Oliver, and Duke Ellington, white musicians such as Paul Whiteman also became popular with white audiences in the 1920s for adapting and domesticating jazz syncopation to European symphonic form.59 George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue is an exemplar of this transformation. Commissioned by Whiteman in 1924 for his orchestral performances and prominently featured in King of Jazz, it is an extraordinary exploration of jazz through classical orchestration, borrowing tempos from ragtime and the Charleston, with a modulating harmonic structure across numerous key changes. Universal paid Gershwin $50,000—an unheard-of fee—to license the work for the film.

The prologue in the film to Rhapsody in Blue provides one of the film’s few, though highly problematic, acknowledgments of the African American roots of jazz, and the color coding of the music is significant. It presents Whiteman standing in front of his giant scrapbook announcing to the camera that “the most primitive and the most modern musical elements are combined in this rhapsody, for jazz was born in the African jungle to the beating of the voodoo drum.” Whiteman’s introduction cues the sonic beginning of off-screen drums as the image cuts to a nearly nude white dancer Jacques Cartier painted entirely in onyx black and highlighted with scarlet red lighting while performing a modernist witch-doctor dance upon a giant voodoo drum. Cartier’s artificially black skin thus becomes the epidermal embodiment of the primitivism of Whiteman’s remarks.60 In ethnographic-surrealist style, Cartier performs in long shot against a turquoise background that makes his blackened body shimmer in front of a larger projected shadow of himself (color plate 6.2).

The negative space of Cartier’s glistening body and primitive shadow form a counterpoint to the beginning of Rhapsody in Blue, as the film and drumming sharply cut to two matching women’s bobbed heads—the German-Jewish Karla and Eleanor Gutöhrlein, aka the “Sisters G,” who were internationally renowned flappers of the time. In medium framing among a multitude of turquoise feathers, their white faces contrast to the onyx of Cartier’s flesh, while also forming an erotic connection between racialized primitivism and subversive flapper sexuality. The sound accompaniment also cuts from the African drumming to the sound of a Jewish klezmer clarinet, sounding the opening refrain of Gershwin’s composition and shifting the score into big-band mode. The camera cranes over the flapper’s faces, and the decadent feathers are pulled back to reveal an Art Deco extravaganza of female performers in evening gowns surrounding the male clarinetist, amazingly played by Cartier again, but now swapping blackface for white skin and tuxedo (color plate 6.3). The epidermal primitivism of the prologue is thus replaced by modern Jazz Age glamor, focalized through Cartier and the visual pleasure of the Sisters G. As the shot unfolds, the orchestration begins, and the scene’s iconic colossal turquoise grand piano comes into view, set off against a silvery palm tree and gray curtains. The enormous piano opens to reveal the orchestra sitting inside. A series of Deco-styled performances and kaleidoscopic abstractions accompany the song through its various modulations and hybridizations of jazz and orchestral music, thus making the sound, rhythm, and visual pleasures palatable to a middlebrow audience. From its prologue through the end, the scene illustrates Whiteman’s claim of sonic as well as visual fusion of the supposed primitive and modern, sublimating Cartier’s black body to his later klezmer-style, dapper version, presented in tandem with the German-Jewish flapper erotics of the Sisters G. Race and female sexuality are thus complexly entwined in the scene’s color coding: the dangerous and primitive voodoo roots of jazz are made quasi-acceptable, though still charged with Jewish alterity, when filtered through Whiteman’s rhapsodic orchestration.

If the hybridity of Rhapsody in Blue acknowledges at least some roots for jazz in African American culture, the film’s opening and closing sketches are far more troubling in terms of color coding. At the film’s beginning, actor Charles Irwin provides a general, master-of-ceremonies introduction, explaining the film’s scrapbook structure. Cutting from Irwin’s monologue to the first skit, the film shifts from live action to animation, providing an origin story of how Whiteman became the so-called “king of jazz.” The scene was Technicolor’s first foray into animation. Produced by Walter Lantz and Bill Nolan (of “Oswald the Lucky Rabbit” fame), it has a dominant color pattern of reds and green-blues. The setting is “darkest Africa,” according to Irwin, and Whiteman is on safari. He runs into trouble on a lion hunt, and, abandoning his useless rifle, he turns to song and fiddle to perform the jazz tune “Music Has Charms,” thereby taming the savage beasts and African natives, who dance and swing along. The scene concludes when a monkey lobs a coconut toward Whiteman, hitting him in the head and causing a crown-shaped protrusion to emerge.61 The skit thus provides a buffoonish colonial fantasy of Whiteman conquering a supposed savage Africa through his improvised music, taking a few bruises along the way, which in turn become the royal mark of his victory.

If the opening skit presents a racist origin story for Whiteman, the film’s closing “Melting Pot of Music” number avoids any mention of the African American roots of Whiteman’s music. Instead, Irwin returns to introduce the skit, explaining that “America is a melting pot of music wherein the melodies of all nations are fused into one great new rhythm, jazz.” In this context, “all nations” is in fact exclusive to European ethnicities, embodied in performances of various British, Austrian, Spanish, French, Russian, and Scottish songs and dances, all in colorful regional costumes. In his theatrical work, John Murray Anderson was best known in the 1920s on the Publix circuit of the United States for stage versions of this “Melting Pot” skit; as in those prior performances, the King of Jazz’s version culminates with all of the European ethnic performers being lowered into a giant melting pot. Whiteman then appears as a master conductor turned chef who stirs the pot while a series of neon turquoise and red circles float up in the air in whiffs of smoke. An overhead shot reveals the mixing of the various performers in abstract, kaleidoscopic fashion, with color-music streaks of turquoise and red swirling about. With grand mass-ornamental pomp, the bottom of the melting pot then swings open and dozens of performers dressed in shimmering gold rush march out performing a jazzed-up symphonic fusion of the previous song styles. Amid ostentatious classical columns mounted with eagles, the absurdity of the scene foreshadows what Guy Maddin would later parody in The Saddest Music in the World (2003), or as J. Hoberman describes it, “This Eurocentric origin story is sung and danced on a set that, with its Doric columns and smoking caldron, suggests a cross between Albert Speer’s design for the Nazi Party Nuremberg rally and Maria Montez’s altar in the later Universal movie Cobra Woman.”62 In such a mix of the ominous and absurd, it is no surprise that the actual African American roots are problematically effaced in Whiteman’s idealized version of orchestral jazz, aglow as it is in Technicolor turquoises, reds, and golds.

Even as King of Jazz presented a largely whitewashed history of jazz that was particular to the U.S. racial and cultural politics of its day, the film did surprisingly well on the global market. It took in approximately $1.2 million from the overseas box office, as opposed to an anemic $549,000 on the domestic market.63 This was due in part to Whiteman’s international fame, and also to the international market’s not yet being fully saturated by staged musicals as the U.S. market was by 1930. Further, as Layton and Pierce richly document, Universal approached the film from the outset as a hybrid, multilingual early sound production. Like many U.S. companies in the 1920s, Universal was highly dependent on foreign sales—approximately 35 percent of its revenues—and the coming of sound threatened the bottom line of many studios because of the potential disruption of foreign sales across language barriers.64 Multilingual productions—films produced simultaneously in multiple languages, typically on the same sets but with different actors and lower budgets—helped companies navigate the transition with minimal disruption. However, with the revue structure and international appeal of Whiteman, Universal undertook a hybrid approach to the multilingual production. It kept many of the Whiteman orchestral scenes while inserting new foreign-language skits and replacing the master of ceremonies, Charles Irwin, with native language speakers—for instance, with Bela Lugosi for the Hungarian version. Universal initially planned sixteen different multilingual versions of the film, but in the end only produced nine of them—in Hungarian, French, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Czech, Swedish, and Japanese.

In terms of color, however, Universal’s multilingual approach raised problems for the company and for Technicolor. As mentioned earlier, Technicolor was not able to expand its factories internationally until the mid-1930s, when it set up Technicolor Ltd in Great Britain. Before then all foreign-release color prints had to be printed at Technicolor’s U.S. labs, which increased shipping charges; for black-and-white prints, the negatives could be shipped internationally to be printed and distributed locally. In part to avoid the extra shipping expenses, Universal produced some of the new sequences in black and white, which could be printed overseas. Further, in an attempt to make the soundtrack as flexible as possible in foreign markets, Universal shifted the sound method from Movietone sound-on-film in the U.S. version to sound-on-disc for the foreign prints.65 The company thus produced an incredibly wide variety of international variations of the film, and this tailored approach proved successful in foreign markets, if not at home.

As these examples reveal, Technicolor and the Hollywood studios negotiated technical issues as well as the racial coding of color as they navigated the problems that sound and color raised for an international market at the beginning of a global Depression. Technicolor’s difficulties with expansion in the United States to meet domestic demands created sustained opportunities for technical innovation abroad, even when other firms were less capitalized. Even as it moved into its renowned three-strip phase from 1932 on, Technicolor still struggled for much of the 1930s to find the right balance of style and cultural import as well as the technical capabilities to achieve it, as Scott Higgins has shown.66 As the decade progressed, the company refined its color designs in relation to classical narration, particularly through the systematizing work of Natalie Kalmus and the Color Control Department, and with its stylistic standards locking in place, Technicolor began to expand more forcefully in the global market.

Technicolor’s international moves did not take place in a vacuum, as various companies in Europe were also innovating color processes at the end of the 1920s. In Great Britain, systems such as Cinecolor, Raycol, Talkicolor, and Dufaycolor were developed in tandem with the transition to sound, with varying success. Many of these processes preceded the sound transition, as Britain had made substantial innovations in photographic color systems throughout the silent era, often with extensive international collaboration, as we have discussed. For example, the Austrian chemist Anton Bernardi developed Raycol and relocated to Great Britain in 1926 in an attempt to acquire financial backing for the process, which eventually resulted in the formation of Raycol Ltd in collaboration with filmmaker Maurice Elvey and others. A complicated two-color additive system, Raycol did not make a large impact. The company attempted to recruit the famous novelist Elinor Glyn to adapt one of her novels, Knowing Men, as a color and sound film using the process. These plans broke down, but Glyn ended up working with Bernardi through another color process he was involved with, Talkicolor, a two-color subtractive bipack system, and United Artists signed on to distribute the film internationally.67 However, even as it was filmed in color, the transfer from the Talkicolor negative to a positive print proved problematic, and it could only be shown in black and white. Coupled with harsh reviews, the film flopped, and Talkicolor dissolved.68

Another process that illustrates the international development of color is the Keller-Dorian system, which was licensed in 1928 in Great Britain as the Blattner Keller-Dorian process and promoted as Moviecolor by Ludwig Blattner, a German-born inventor, director, and studio owner based in London. As François Ede has detailed, Keller-Dorian was a lenticular process developed in France beginning in 1908 by Rodolphe Berthon with the support of the industrialist Albert Keller-Dorian.69 It was not until 1922 that a functioning prototype was in operation for filmmaking, and during the 1920s it was experimented with by Able Gance for Napoléon and by Robert and Sonia Delaunay, among others, as discussed in chapter 5. Berthon and Keller-Dorian established the Société du film en couleurs Keller-Dorian to exploit the process in the 1920s. However, by the end of the decade, the company was in financial disorder and began selling off patents and distribution rights. Eastman Kodak acquired some of the Keller-Dorian patents in the United States (with rights also in Canada and Australia) and used them to develop Kodacolor for the amateur 16mm market. Blattner acquired the distribution rights for Great Britain and the rest of the world except for Kodak’s regions of distribution.70 Blattner debuted several short color films, with positive reviews:

The programme on Sunday also included a demonstration of the Keller-Dorian colour film process known as Moviecolor, of which Mr. Blattner owns the British rights. In certain technical aspects this process is probably the best yet seen in this country. There is no chromatic flicker, and the colours—particularly towards the red end of the spectrum—are not unpleasant.71

Karl Freund, who was contracted with Blattner, was involved with the color process; it was announced that he was working on a feature sound and color film called Refuge, but apparently it was not completed.72 Seemingly for technical and financial reasons, Blattner ended up selling his rights in the Keller-Dorian process to Technicolor in 1930, just as Technicolor was considering expansion into Great Britain:

Technicolor has entered into an agreement with Keller-Dorian, it is announced by the Ludwig Blattner Pictures Corps., Ltd., which controls the latter color process. The statement reads in part: “The exploitation and manufacturing interests in connection with the Keller-Dorian color-processes, as contained in the license granted by Moviecolor, Ltd., to the Blattner Corp., are now solely controlled by the Technicolor Co.”73

According to Troland’s Technicolor diaries, he had been experimenting since 1929 with adapting Keller-Dorian negatives for imbibition printing.74 However, as Layton and Pierce note, Technicolor was overall unimpressed with the process. Still, it continued into the 1940s, eventually being adapted as Thomsoncolor in France, where it was deployed unsuccessfully for Jacques Tati’s Jour de fête in 1947.75

As Keller-Dorian exemplifies, the transnational circulation of color processes, inventors, and patents defined this era of color innovation. However, these developments occurred in fits and starts, as technical and financial as well as cultural issues strongly shaped the renovation of color in the cinematic field. As a final note illustrating the complexities of such transnational negotiations, Moviecolor, following its failure to exploit the Keller-Dorian process, resurfaced to sue Technicolor and Kodak in the United States in 1959, claiming that the defendants had, in 1930, violated antitrust laws by colluding to suppress the process, causing Moviecolor to become insolvent.76 The case made it to the federal appeals level, but found no traction in the courts. Still, such struggles illustrate the complexities, shifting power relations, and long durées of technical change within the cultural field. If photographic color systems struggled through this period of transition to sound, the effects on applied color systems were even more strongly felt.

Applied Color and Sound

The end of the 1920s has been seen as the end of applied coloring in cinema, but this is inaccurate: these earlier processes were not made obsolete with the coming of sound and the rise of Technicolor. However, they did lose their position of dominance in the industry. As already discussed, many photographic color systems adapted applied coloring techniques into their processes during the 1920s: Technicolor’s imbibition printing was informed by the Handschiegl lithographic process, and tinting and toning methods were used in Multicolor’s process to filter light and create two-color images. In these ways, the techniques of applied coloring had a long life after the 1920s, even if in relatively invisible ways. Beyond technical repurposing, however, one can examine applied coloring methods in their own right and trace their continued use at the end of the decade and beyond. The coming of sound as well as the influx of new photographic coloring processes reduced the practice of adding color manually to films, yet these techniques did not disappear. Even as the excitement over photographic color, and Technicolor in particular, surged in the late 1920s, it was far from clear that photographic color would in fact take over the industry, particularly in light of the downturn in international markets and variations in aesthetic preferences and technical developments around the world.

The trade press documents key examples of hand coloring, stenciling, tinting, and toning continuing into the 1930s and beyond. For instance, Gustav Brock explained his ongoing work as a hand colorist for feature films at the 1931 SMPE Symposium of Color, and he subsequently published his account, arguing for the vitality of hand coloring in an era of increased color consciousness.77 His coloring studio was in New York City, and much of his work was for premiere screenings in the city. As examined in chapter 5, he promoted the use of color only for brief film sequences that were meant to enhance the diegetic meaning already inherent to a scene, rather than adding a new layer of meaning. The hand coloring of fire was his specialty. In 1925, he noted: “Where fire is shown on the screen, hand coloring is indispensable. To look at fire without coloring is like looking at a man playing a violin without hearing the tune. Fire makes every other thing look colorless in comparison.”78 Again, in 1931, he claimed that colored flames “always impress themselves so dominatingly on our sense of sight that all other surrounding colors are reduced to half-lights and shadows.”79 Brock’s invocation of color consciousness was also related to fire: “At this time when motion picture audiences wherever films are shown are becoming ‘color conscious’ they are keenly disappointed if they are viewing a picture in which there are fire scenes and these scenes are not made to represent the actually [sic] coloring of flames.”80 It is as if Brock took to heart the old idea that color’s Latin root was calor, fire, a heavenly property of light.

As exemplified in his comparison of color to the harmony of a violin, Brock frequently invoked a musical analogy to theorize color’s function in film. Taking not just a musical but also a linguistic angle, he explained at the end of his 1931 SMPE article that “when intelligently used, there will be just enough coloring to permit the color to ‘talk,’ ‘explain,’ emphasize, and enhance the illusion which the picture is intended to create.”81 Beyond the analogy, he was also adept at hand coloring both silent and sound films, estimating that he could color on average approximately fifteen feet per hour.82 With the coming of sound, he noted that, because sound films were now predominantly edited as negatives and printed to spliceless positive reels to avoid unnecessary pops on soundtracks (as opposed to positive-edited prints that made it easier to insert short color sequences, as discussed in chapter 4), colorists had to spend more time winding through films:

Since the advent of the talking picture each color job contained in each reel of a picture has been delivered for coloring in a thousand-foot reel. In order to color a scene twenty feet long in a picture of a release of 200 prints, the hand-color man will have to wind and rewind 200,000 feet of film and carry responsibility for the proper handling of all that film, in addition to having to color it.83

In terms of sound films, Brock largely collaborated with S. L. “Roxy” Rothafel, coloring sound prints for Rothafel-managed cinemas in New York City, such as the Sound Picture Theatre of Rockefeller Center.84 Based on summaries in the Film Daily, some of the U.S. films that Brock colored in the 1930s were Pickanniny Blues (Mannie Davis and John Foster, 1932), a short animation based on Aesop fables; The Death Kiss (Edwin L. Marin, 1932); The Next War (1933); Captured! (Roy Del Ruth, 1933); Moonlight and Pretzels (Karl Freund, 1933); Little Women (George Cukor, 1933), with work “on colored fireplaces and lighted candles which help tremendously in heightening the cozy atmosphere in contrast to the icy blasts outside and getting over the spirit of the Yuletide”; The Vampire Bat (Frank Strayer, 1933); Sisters Under the Skin (David Burton, 1934); Here Comes the Navy (Lloyd Bacon, 1934), including “a booming gun, a fire in the gun turret of a boat approaching a battleship at night, a self-illuminating lifesaving buoy, and the American flag”; and “the fire scene which climaxes the action” in Adventure Girl (Herman Raymaker, 1934).85 As the details from the Film Daily indicate, Brock indeed continued selective hand coloring in the sound era, particularly focusing on fire elements for U.S. releases.

Both The Vampire Bat and The Death Kiss are extant and worth further analysis. Color sequences in The Vampire Bat have been recreated by UCLA Film Archives; those in The Death Kiss have been preserved and restored by the Library of Congress. As Scott MacQueen of UCLA recounts, he discovered advertising by Brock indicating that The Vampire Bat had been colored during the film’s “man hunt” scene, and the archive drew from the LOC material to model a reconstruction of the hand coloring.86 The film was a poverty-row horror production by Majestic Pictures, starring Fay Wray and Lionel Atwill. The setting is an Eastern European village, where the townspeople mistakenly suspect that a mentally disabled man, Herman Glieb, is a vampire responsible for recent corpses that have turned up drained of their blood. In the hand-colored sequence set at night, townspeople chase Glieb with torches into a cave, where he sadly jumps to his death to escape. Unfortunately for the townspeople, they have the wrong man—a mad scientist being the real murderer. Knowing Brock’s predilection for coloring fire effects, UCLA digitally rotoscoped and colored the torchlights in vibrant yellow-orange for a remarkable effect, as the saturated hues light up the night among the diegetic screams of Glieb pursued by the torch-wielding men and their howling hound dogs.

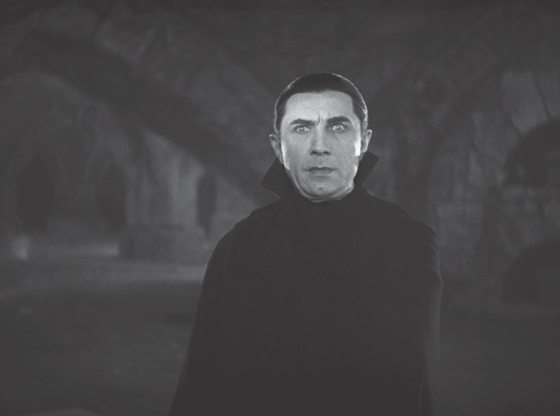

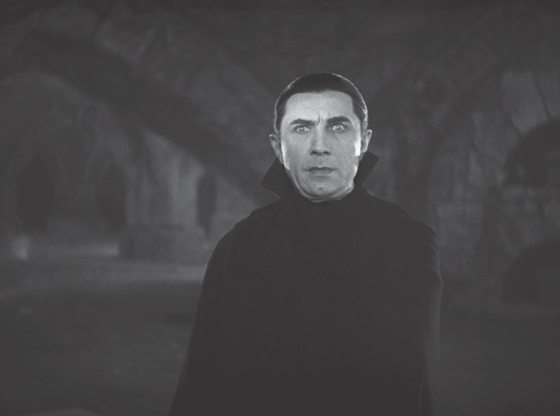

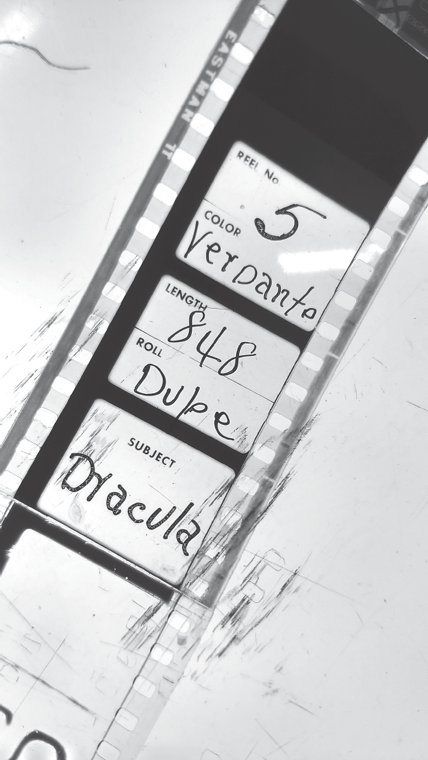

The Death Kiss is also spectacular in its use of hand coloring and sound, even as it too uses limited coloring effects. A Tiffany Pictures poverty-row production, the film presents a murder mystery reflexively set in a film studio; it reunites actors David Manners (playing a screenwriter), Bela Lugosi (a studio manager), and Edward Van Sloan (a director), all of whom were previously in Dracula (Tod Browning, U.S., 1931). Tiffany had specialized in color productions in the late 1920s, producing a series of short Color Symphony productions using two-color, dye-transfer Technicolor as well as the successful and much costlier dramatic feature Mamba (Albert S. Rogell, U.S., 1930), which was marketed as the first dramatic feature entirely in Technicolor and had a production budget running close to $500,000, in contrast to the $50,000 budget for The Death Kiss.

The murder in The Death Kiss takes place in the first scene, which turns out to be a film within a film (also titled The Death Kiss). A beautiful woman approaches a well-dressed man, Myles Brent, outside an Art Deco café, marks him with a kiss, and shortly afterward he is gunned down by unknown assailants. After his death, a dramatic pan to the right reveals that the killing was in fact part of a scene being shot in a studio—a “terrible” take, according to the director, Tom Avery (Van Sloan), in which Brent was overly “gymnastic” in his death. Brent does not react to the critique, as he has in fact been murdered: one of the prop guns has been replaced with a loaded one. After the police arrive and begin their investigation, they decide to watch the footage to see what clues might be gleaned from the shoot, which leads to the first of two hand-colored sequences in the film. As the police, studio execs, and actors file into a studio theater to watch the dailies, a single light sconce on the left of the screen is colored light yellow, and as the projector begins to cast light through the projection window, it too is colored yellow. The film cuts to the screen, and the scene that began the film is now replayed, though from a different angle (forty-five degrees to the right) and with the on-set directions now audible (the clapper, “rolling,” “action”). The woman approaches and kisses Brent again, but just as he is about to be shot, the screen dramatically erupts in orange hand-colored flames and white noise fills the soundtrack (color plate 6.4). As the police quickly discover, the murderer, already disappeared, has slipped into the projection booth, knocked out the projectionist, and lit the nitrate print on fire with a cigarette. The second hand-colored sequence is at the film’s climax, when the killer—who turns out to be Avery, the director, who is out for revenge on Brent for having an affair with his wife—is finally revealed and pursued by police among the catwalks above the soundstage. Avery has cut the lights, so the police resort to flashlights, colored yellow, and in the ensuing dramatic gunfight the bullet flashes are colored bright orange, amplifying the pop of the gunshots. All of these lighting effects were colored by Brock.

Purportedly at a preview screening, Brock’s coloring created such a stir—presumably the shot of the burning film—that the producers decided to color all three hundred copies of the film for distribution, as opposed only to some of the premier prints.87 The large number of colored prints is probably the reason the Library of Congress has been able to preserve and restore a print of the film with Brock’s coloring, whereas most of Brock’s work from the 1920s and 1930s, which generally featured in much smaller premiere print runs, has now been lost—much as the fictional fire engulfs the scene of The Death Kiss. Color, like nitrate film, glows beautifully but too often without an archival shelf life.

Brock continued to color films into the 1940s, though his work appears to have tapered off after 1934, even though he adapted his methods in 1941 to incorporate 16mm Kodachrome stock to produce reduction copies of his 35mm hand-colored prints.88 He even unsuccessfully propositioned Alfred Hitchcock about hand coloring the opening fire (of course) in Saboteur for twenty-five cents a foot, “which will startle the audience and which will make your fire scenes live and be remembered.”89 Hitchcock did not reply, but he would use a similar hand-tinting effect a few years later at the end of Spellbound (1945), though it functions differently from Brock’s more diegetic-oriented work, adding an Expressionist red death tint to the film’s final first-person-point-of-view suicide.