The strong appeal of Ruttmann’s films lies in the psychological stimuli which make them continually effective…. the viewer is pulled into a whirlwind of motion and integrated into an atmospheric blend of colours that never leave him for an instant. Squares and rectangles shoot forward, multiply, disappear, turn up in unexpected points in space, and exchange energies with one another in the most astonishing fashion. A resonance with the soul is generated, as in an internal combustion fashion. Then wavy motions, now gentle, now violent, overrun the image; they tear off into shapes and join together harmoniously. The colour shading, graded into the tiniest detail, trickles grace and sweetness, passion and agitation, into the viewer’s heart.

—Rudolf Kurtz, Expressionism and Film

In The Glass Architecture (1914), the German science fiction writer and journalist Paul Scheerbart explores the utopian possibilities of color for transforming the material dynamics of the lived environment. The work is a novelistic fantasy made up of 111 aphorisms describing how, in the near future, steel and colored glass would replace wood and brick structures to create an empathetic and technologically infused world around us. Not only would glowing hues illuminate homes and work spaces, but even the skies and waterways would radiate color: boats and aircraft would be equipped to project prismatic lights across landscapes, forming a second nature transformed by technology. In a curious digression in this utopian fiction, Scheerbart reflects upon the occult movement of Theosophy and its approach to color: “I am convinced that every constructive idea will appear in many heads at the same time and quite irrationally; one should therefore not speak carelessly about the seemingly confused and crazy; it generally contains the germ of reason.”1 It is this “germ of reason” pertaining to color that is of interest in this chapter, for what it reflects about how scientific and aesthetic as well as occult knowledge of color circulated in the 1920s through various modernist and avant-garde movements in and around cinema.

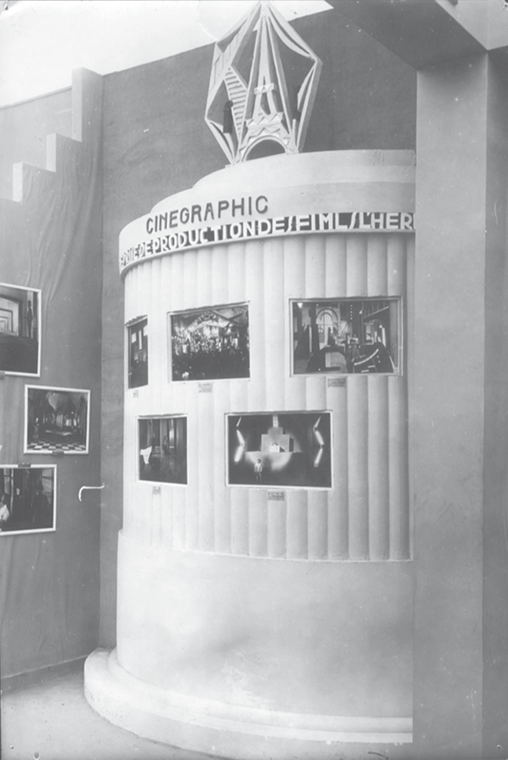

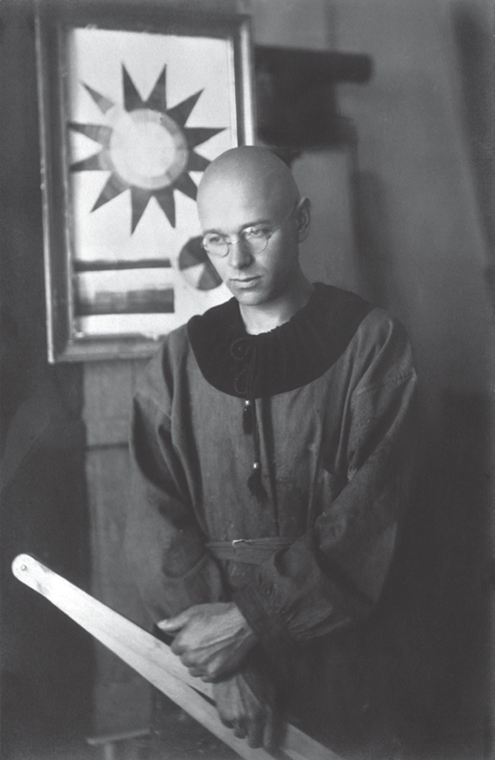

Photograph by Armin Herrmann, courtesy of Collection Werkbundarchiv—Museum der Dinge Berlin.

In tracking modernist approaches to color, Scheerbart’s reflections serve as a leitmotif, marking the ways in which color functions as a trope of cosmopolitan visual style.2 Though he died in 1915, his work was posthumously influential both through his writings and through his collaboration with the architect Bruno Taut on the Glashaus (Glass Pavilion), an elaborately colored, glass-dome structure at the Cologne Deutscher Werkbund Exhibition in 1914.3 An architectural work of prismatic splendor, the pavilion used Luxfer Prism glass tiles to cast colored light throughout the space. In addition, it contained a small room in which a projecting kaleidoscope was installed to rear-project abstract color images onto a specially designed four-foot glass screen at the back of the house.4 An expanded form of cinema was thus integrated into the chromatic wonder of the space, creating hybrid medial engagements with projected color, parallel to those we tracked in chapter 3.

Taut, a colorist extraordinaire, would go on to interact with Walter Gropius during the early years of the Bauhaus through the Crystal Chain Letters group, an Expressionist consortium of utopian-minded architects, many of whom were also influenced by the occult—for instance, Gropius’s wife at the time, Alma Mahler, was a well-known Theosophist.5 Across such creative networks, Scheerbart’s ideas about glass and color have been traced at the margins of modernist design through figures such as Taut and Gropius as well as Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier. The International Style associated with these architects is by and large monochromatic, yet recovering the syncretic place of color in modernist design, art, and cinema is vital for assessing the technical and aesthetic ideals that proliferated within modernism. Scheerbart’s utopian vision, as Walter Benjamin notes in a perceptive essay, “was of a humanity which had deployed the full range of its technology and put it to humane use”—a counterpoint to what Benjamin described elsewhere as humanity’s “bungled reception of technology.”6

From Scheerbart to Gropius and his collaborators at the Bauhaus and on to various other artists working in the 1920s such as Walter Ruttmann, Fernand Léger, and Sonia Delaunay, what is significant is how, through their innovative uses of color, they outline a new media ecology. Faced with a rapidly expanding chromatic culture that aimed to codify and instrumentalize color’s affective and sensorial role in advertising and mass production in order to sell products more effectively, these artists were often part of this process even as they experimented with more humane forms of color practice: to transform bungled receptions into media architectures worth living in.

Color was integral in these exchanges. It was as important to the international formation of modernism as it was to industrial modernity. The synthetic revolution of colorant production in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was quickly adapted for painting. New artist-grade pigments—such as cerulean blue, alizarin crimson, and viridian green—emerged with increasing frequency, enabling chromatic experiments on the modern canvas by Impressionists, Pointillists, Postimpressionists, Fauvists, and beyond.7 The development by the American painter John Goffe Rand in 1841 of premixed pigments, available in portable, tin paint tubes, enabled painting en plein air; Sherwin Williams’s refinement of linseed-oil paints in the 1880s was also groundbreaking for painting. In conjunction with such technical changes, the artistic palette of the nineteenth century produced a standardized and technically refined color image that spurred the chromatic revolution of the twentieth century, particularly in the 1920s. Color became a type of ready-made that no longer required expert preparation before application.

If one topic traced here is the influence of industrial innovation on creative practice, another focus is the circulation of cultural knowledge about color within cosmopolitan networks. Taking a cue from Scheerbart, the best-known instance of this involves Theosophy, with its elaborate theory of color, which sought to standardize occult meaning. In Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater’s syncretic, Eastern-influenced work Thought Forms, mental states, emotions, and their auratic emanations are color coded. For example, in their richly illustrated system, variations of red “indicate anger” and “animal passion,” while blues “indicate religious feeling”—meanings that pulse across the spiritual plane as chromatic auras.8 Corresponding to the color guidebooks of the aniline industry discussed in chapter 1, Besant and Leadbeater’s works were lushly illustrated with a standardized color chart that allowed users to identify with ease the occult codes they elaborated. By knowing a color’s standard meanings, one could defend against spiritual and emotional attack and, conversely, project harmonious auras toward others. Even if one might today dismiss such esoteric claims for color, historically they profoundly shaped how color was systemized and deployed in abstract art of the early twentieth century.9 Though idealist in nature, these various artists were also materially oriented and aimed to use color to uplift the spiritual awareness and color consciousness of their audiences through sensory experience, providing a coded way of entering “the spiritual realm through earthly sensations.”10 As Bernard Smith has pointed out regarding early abstraction, “grounded in the hope for and belief in a universal religion, [the occult] provided innovatory content to an art that might have otherwise been dismissed as ‘decorative.’”11 Long denigrated against the rationality of form in Western aesthetic theory, color was a central aspect of this transformation in abstract art—reversing the polarity by giving radical meaning to what had previously been thought of as surface-level ornamentation.

The occult was not the only source of color knowledge among modern artists in the 1920s. Color science, too, was prominent. Chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul’s ideas about color contrast from the nineteenth century remained in currency, as did Albert Munsell and Wilhelm Ostwald’s more contemporary studies that were influential on artists such as Paul Klee, Piet Mondrian, Sonia Delaunay, and Claude Fayette Bragdon, as well as on filmmakers and visual musicians such as Walter Ruttmann, Thomas Wilfred, and Oskar Fischinger. Physiological and psychophysical variants of color science influenced much of the experimental work being carried out by the avant-garde in the twenties and underpinned their engagement with aesthetic theories such as Einfühlung (empathy) and abstraction. Indicative of this, for example, is the emphasis placed on color in László Moholy-Nagy’s influential Malerei, Photographie, Film (Painting, Photography, Film): “The biological functions of colour, its psycho-physical effects, have as yet scarcely been examined. One thing, however, is certain: it is an elementary biological necessity for human beings to absorb colour, to extract colour.”12

The expansive, cross-field, and intermedial nature of these influences was not by chance but was grounded in artistic exchange during the period, which operated in parallel ways to the industrial forms of knowledge transfer discussed in chapter 1. Through the ever-expanding networks of cosmopolitan collaboration and exhibition in the 1920s, color styles, theories, and artistic practices flowed globally in the form of avant-garde polemics, utopian visions, and the emerging International Style. What happened in Germany influenced French, Dutch, British, and U.S. artistic practices, and vice versa, creating transnational circuits of color knowledge and practice across artistic media. This provided the outlines of a new cosmopolitan habitus of modern color, in Bourdieu’s sense—connecting restricted and large-scale modes of cultural production that wove through both the avant-garde and the culture industry.13 Through such connections, ideas about color, as Scheerbart noted, appeared seemingly irrationally in the heads of various artists at the same time. Tracking the exchanges that color fostered allows us to reconsider many of the canonical avant-garde works and movements of the decade. Just as color generated new approaches to painting in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was also integral to modernist engagement with the moving image, often with Arts and Crafts influences, ranging from the Bauhaus and Expressionism to the French avant-garde and Pictorialist experiments in and on the fringes of Hollywood. As an emerging mass art, cinema’s chromatic palette became increasingly appealing to artists—particularly for the avant-garde, who were by and large fascinated by the vulgar and sensorial attractions of cinematic technology. Focusing on the modernist attraction to color allows us to reassess why and how the 1920s was the decade in which artistic engagement with cinema flourished.

Useful Abstraction at the Bauhaus

Following from Scheerbart, we turn first to the German context of color in the 1920s. Given Germany’s rich industrial history of colorant production, as well as its Romantic traditions of color theory and practice, color provided fertile ground for artistic experimentation throughout Weimar Germany. During the 1920s, this was most readily apparent in the curricular experiments of the Bauhaus, which we use here as context for thinking through the useful, pedagogical functions of color, abstraction, and empathy as they intersected with industrial prerogatives, art education, and the Absolute Film movement. “Usefulness” has recently been theorized in relation to the moving image by Charles Acland and Haidee Wasson, as a category for thinking through the ways in which various nontheatrical institutions have used the moving image as a functional medium for ends other than art and entertainment.14 In examining the practical uses of the moving image, they aim to trace the diverse forms of cultural capital that accrue within various fields of production. Accordingly, we are interested in how color and abstraction in film intersected and functioned within the parameters of the Bauhaus for aesthetic goals particular to the field of art education at the time, related both to the occult and to the notion of Einfühlung as taken up at the school.

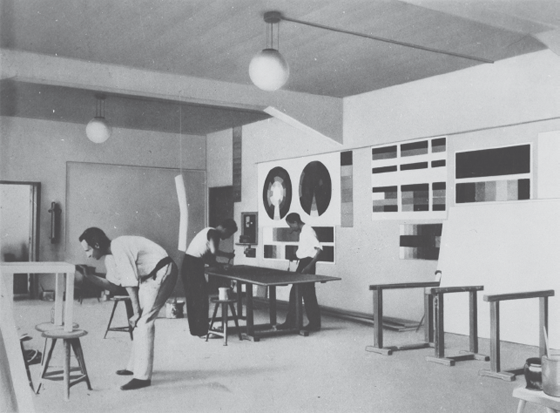

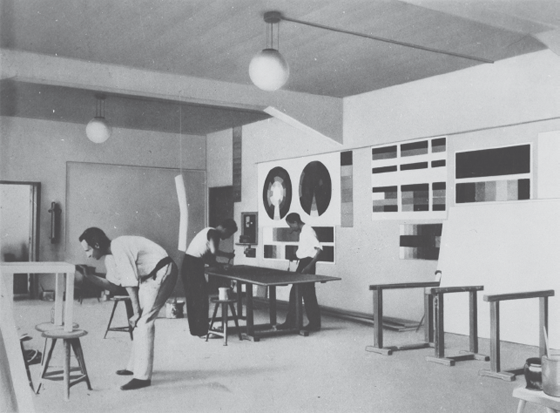

Courtesy of Bauhaus-Universität Weimar, Archiv der Moderne.

As has been well established, cinema was an interest, though one not fully realized, at the Bauhaus.15 By contrast, color was fundamental to its curriculum and legacy, and in the limited examples of cinematic experimentation at the school, there are important intersections between the two. A fitting example is Herbert Bayer’s design for a cinema, “Kinogestaltung” (1924–1925, color plate 4.1), which he produced at the end of his time as a student of the Bauhaus in Weimar under the tutelage of Johannes Itten and Wassily Kandinsky, just before he was hired in 1925 as the director of the printing and advertising workshop when the school moved to Dessau.16 Comprising four sketches, Bayer’s imagined cinema is functional and minimalist—a striking counterpoint to the ornate movie palaces that dominated the decade. The theater’s façade is a flat and functional square meant to be plastered with posters—magazine images of Harold Lloyd and Calvin Coolidge are the examples—and the entrance is a modern revolving door, much like the one in Murnau’s The Last Laugh, also from 1924. Passing through the brief foyer into the cinema hall, one is faced with a near op-art design, as the upper left image of Bayer’s plan reveals. Centered in the rear of the theater, one sees a virtual, multistable pyramid (as if viewed from above, or conversely from below) of receding hues stratified in space. Seating perhaps two hundred, the theater is in fact rectangular, with three color-coded sections of flooring and seating that shift, back to front, from light to medium to dark gray, paired with matching colored sections on the walls progressing from yellow to orange to red. On the back wall is the tip of the pyramid reaching into space, which is the white cinema screen surrounded by a black and red proscenium. Though minimal in design, there is an essential dynamism to this cinema space, elaborated through the optical movement of the color pattern and schematically by the illustrated film beams vectoring from projection booth to screen. These still illustrations optically project movement, a key trope of the period among avant-garde artists, and one with which both cinema and color were closely aligned.

The chromatic dynamism of Bayer’s cinema is significant: its colors are ordered as the warm hues of Johannes Itten’s color sphere, a pattern that Itten himself had experimented with in the same flowing order—yellow, orange, red—in the center of his abstract painting Horizontal Vertical (1915). These same three colors were also interconnected and projective in Kandinsky’s color theory: “Warm red, intensified by yellow, produces orange. Through this admixture, the movement of the red becomes the nucleus of the impulse, spreading out towards the spectator.”17 In juxtaposition, the gray flooring of Bayer’s plan recalls the studies carried out in in the 1910s on color value by the German chemist and color theorist Wilhelm Ostwald. Ostwald aimed to quantify and standardize color theory and practice, and he drew from the emerging fields of colorimetry as well as psychophysics to theorize new optical and physiological standards for color harmony. Innovatively, Ostwald argued that harmony is based upon the variation of color values—a hue’s shifting tonality from lightness to darkness as in Bayer’s design—rather than through the balancing of color contrasts, which was the dominant view held since Michel Eugène Chevreul’s delineation in the nineteenth century of simultaneous and successive contrast. Ostwald did not just theorize color harmony, but contentiously, he insisted that artistic practice should be based upon his system and urged that it be incorporated into educational curricula. His color theory was of interest throughout the 1920s to Kandinsky and others at the Bauhaus, yet its prescriptiveness was also scorned by Itten and Klee.18 Ostwald became affiliated officially with the Bauhaus at the end of the 1920s as a member of the school’s board of trustees, and Bayer, along with Gropius and Moholy-Nagy, corresponded with him in 1926, which led to a week of lectures at the Bauhaus in June 1927.19 Later, when Bayer had immigrated to the United States, he worked closely at the Container Corporation of America with Egbert Jacobson, the chief proponent and publisher of Ostwald’s work in the United States.20 In other words, Bayer had a lengthy interaction with Ostwald’s theories, and he brought these various influences together in his three-dimensional sketch for a movie house, a cinema conceived as a geometric color space that dynamically enveloped the spectator as much in its architectural hues as in the filmic space of the screen. Reimagined by Bayer as an immersive color space, cinema functioned as a modern, industrial medium that was conducive to the new abstract language of color, light, and movement being articulated at the Bauhaus and beyond.

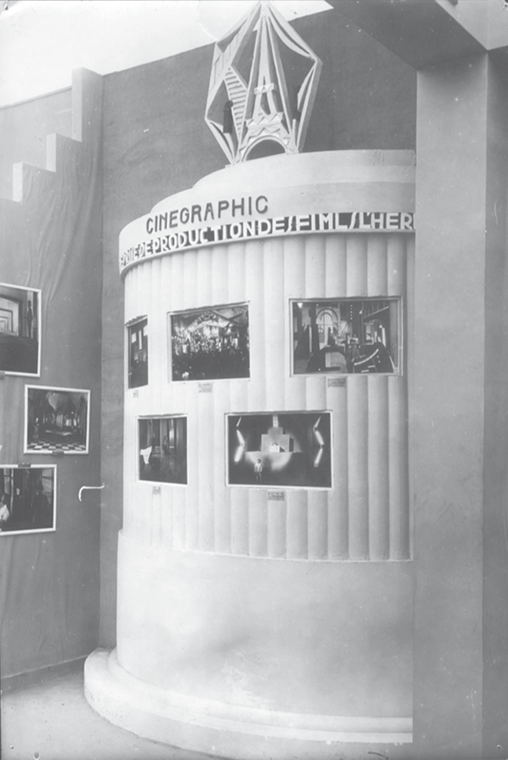

Following Bayer’s cinema design, it is worth elaborating further the central role that color played at the Bauhaus and its multivalent associations with science, the occult, aesthetic theory, and moving-image practice.21 Established in 1919 by Walter Gropius, the Bauhaus developed in part out of the Arts and Crafts movement in Germany, in particular from the Deutscher Werkbund—the German Association of Craftsmen that aimed to raise the standard of German labor and humanize industrial craft for the emergent mass society.22 The Werkbund was a crucial meeting point for a number of the figures discussed here. Its first public exhibition in Cologne in 1914 was also the site of Scheerbart and Taut’s Glass Pavilion, alongside a model factory and office building designed by Gropius and Adolf Meyer. Ostwald also made an appearance in Cologne in 1914, as the Werkbund allowed him to arrange a show of German paints and dyes at the exhibition.23 Across this network of relations, Gropius shared the Werkbund’s and Scheerbart’s utopian perspective, which is reflected in the Bauhaus’s aim to rethink art education for an industrial age, particularly as the school developed in the 1920s.

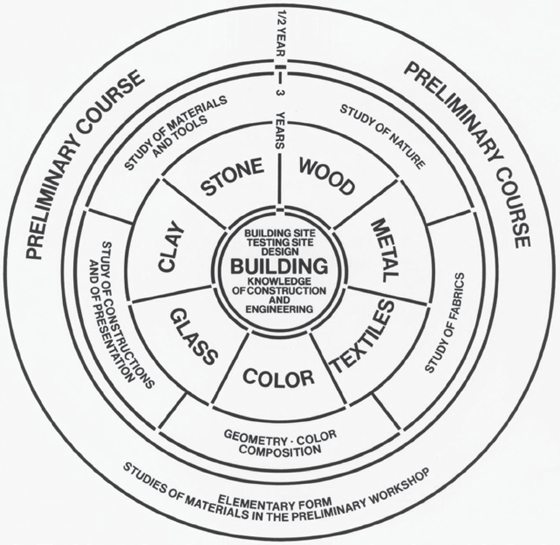

From the beginning, color was crucial for negotiating the relation between art and industry in the curriculum of the Bauhaus, and it helped foster the school’s unique approach to the aesthetics of technology. In Gropius’s initial outline of the curricula of the school in 1919, the “physical and chemical theory of color” is listed as being part of the study of “science and theory.”24 Of the initial instructors hired at the Bauhaus, it fell to Johannes Itten to develop the study of color within the school’s “preliminary course,” which Itten designed as a trial semester for students to help guide them into apprenticeships in more advanced, specialized workshops for the rest of their studies.25

Courtesy of © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

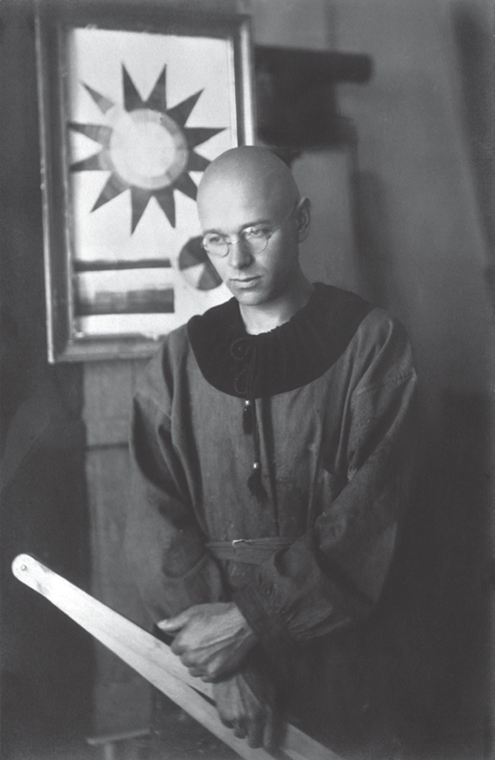

Besides Gropius, Itten was the most experienced pedagogue at the school. In tandem with color studies, he developed a holistic approach that paired theoretical with practical training, alongside physical exercise. His method was steeped in the occult—in part under the influence of Theosophist Alma Mahler, who earlier had encouraged his interest in mysticism while also introducing him to her then husband Gropius in 1918, just as the school was being established.26 Occult influences such as these were relatively common in art education at the time, particularly in relation to color and how it was taken up aesthetically in school curricula as a means of developing the color consciousness of students, as discussed briefly in chapter 1. The expansive nature of the notion of color consciousness allowed it to be interpreted as both a sensory-perceptual capability and a spiritual one, depending on context. Rudolf Steiner, for instance, in his lectures on color and pedagogy, wrote of the ways in which color could expand the spiritual consciousness of students, and this is a crucial component of his Waldorf system, founded in 1919 in Germany and Austria, and rooted in Goethe’s Color Theory as much as it was in the occult. For instance, Steiner notes that the purpose of color instruction is to “awaken in children the feelings that can arise only from a spiritual scientific perspective of the world of color.”27 He aimed to educate students’ spirits as well as their practical skills, and color played a vital, experientially based role in cultivating their sensory abilities. At the Bauhaus, Itten similarly pursued a holistic approach to color pedagogy. He was an adept teacher in the Mazdaznan religion, a form of neo-Zoroastrianism that emphasized the attunement of the body for spiritual enlightenment. As a gifted teacher, he was incredibly influential, converting many to his beliefs, and he famously embodied the role of a mystic, wearing priestly scarlet robes he designed himself and shaving his head. This ultimately led to rifts within the school, and after growing conflicts with Gropius, Itten left the Bauhaus in 1923, marking a relative break from the occult and Expressionist phase of the school. Nonetheless, it is worth dwelling in brief on Itten’s approach to color, as it opens ways for thinking through the Bauhaus’s ongoing engagement with sensory education after his departure in ways that connect to abstract film.

Some of Itten’s earliest lessons guided students to find their own subjective color harmonies through experimentation with color materials—paints and colored sheets of paper. Itten describes one of his opening lessons at the Bauhaus: “I had long chromatic rows of real materials made for the tactile judging of different textures. The students had to feel these textures with their fingertips, their eyes closed. After a short time the sense of touch improved to an amazing degree. I then had the students make texture montages of contrasting materials.”28 In his integration of color with sensory education, Itten’s lessons were broadly synesthetic in nature, mixing the senses—of visual with haptic perception, color with touch—so that the study of color allowed one to feel into chromatic objects and architectural spaces through their textures, an approach he developed in part with musician Gertrude Grunow, who taught influential courses at the school on harmonization.29 Itten’s emphasis was also drawn from German aesthetic theory of the time, specifically the notion of Einfühlung—literally, feeling into (sich einfühlen) something—which is a forerunner to the aesthetic concept of empathy.30 The German philosopher and psychologist Theodore Lipps and art historian Wilhelm Worringer were two of the key theorists of Einfühlung at the turn of the last century, and Itten and others at the Bauhaus were familiar with their analyses of the ways in which humans empathize with inanimate objects as well as with living beings.31 One feels into them, mimicking their physical states, as when a spectator unconsciously sways to the rhythms of a dance performance or taps a foot along with the montage sequence of a film. These types of aesthetic responses provide useful, embodied knowledge. For Itten, color was one of the key entry points to his occult-inflected version of Einfühlung—a synesthetic nexus that allows one to feel into the aura of things.

Courtesy of © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ProLitteris, Zurich.

Significantly, the concept of Einfühlung was also used to analyze film in the 1920s. In Rudolf Kurtz’s seminal Expressionism and Film from 1926, he draws on psychophysics to describe the embodied and empathetic nature of Absolute Film, in line with Lipps’s understanding of Einfühlung:

The viewer empathizes with [fühlt sich] the mathematical shapes and calls forth corresponding sensations. The procedure takes place unavoidably, subconsciously: the elementary lines and relationships between shapes, together with their movement, direct the emotion along its courses, through their gradations of light, so that an emotional counter-image arises which correlates to the struggle, the harmony, and the reconciliation of those relationships between shapes. Thus, the abstract work of art is unequivocally ranged into the conventional psychological proprieties of the masses. These elemental procedures get even richer colourations from the accompanying feelings that grasp the viewer as a result of memories and associations he has experienced in his concrete life.32

Kurtz exemplifies the ways in which pedagogical notions of color and aesthetic experience were being deployed in film criticism to describe the sensuous nature of spectatorship. Kurtz brings together both psychophysics and Einfühlung in this passage, fühlt sich being the conjugated verb form (sich einfühlen) of Einfühlung—to feel one’s way, or to project into or empathize with an object.33

Such theories of color were central for the moving-image work carried out and viewed at the Bauhaus, particularly following Itten’s departure in 1923. This transition also marked an industrial change in the school’s direction that reshaped its approach to color: away from occult and Expressionist influences toward Gropius’s new unity of “Kunst und Technik” (“art and technology”), his famous motto for the school, as articulated at the Werkbund’s annual conference in 1923. Moholy-Nagy’s work in particular reflects this change toward a more technical and scientific approach to color, and it is from this matrix that educational experiments with moving-image technology were also carried out at the school. Moholy-Nagy was the chief, but by no means the only, proponent of film at the Bauhaus. Though he carried out little actual film work during his time at the school, his interest in the medium is the best known of the Bauhaus, in part because of his later films and also because he engaged extensively with the moving image in his influential writings—even proposing an “experimental film center” (“Versuchsstelle für Filmkunst”) in his 1925 script outline for “Dynamics of a Metropolis,” which could not be realized at the school because of the lack of funding.34 Moholy-Nagy’s critical engagement with film frequently dovetailed with his long-standing interest in color. In fact, the nexus of ideas that Moholy-Nagy developed regarding film and color illustrates their entwined importance at the Bauhaus. For Moholy-Nagy, the moving image as an industrial art was interwoven with the renovations the school was making to its curriculum in painting, sculpture, performance, and architecture, as the faculty and students attempted to synthesize a new unity among them. Across this intermedial engagement with the moving image, color continued as a key device for binding the school’s pedagogical experiments: it was one of the unifying threads that interconnected across disparate media, theories, and creative practices.

Active in Constructivist, Dada, and De Stijl circles, Moholy-Nagy was recruited by Gropius in 1923 specifically to take over the preliminary course after Itten and to direct the metal workshop. He carried out the preliminary-course assignment in collaboration with Josef Albers, who had been promoted from student to teacher, and together they helped institute Gropius’s merger of art and technology within the curriculum.35 As Moholy-Nagy recalls in his “Abstract of an Artist” (1944), discovering color’s nonrepresentational power in 1919 marked “a turning point” in his early aesthetic development: “Color, which I had so far considered mainly for its illustrative possibilities, was transformed into a force loaded with potential space articulation and full of emotional qualities. I started to clarify how different colors behave when organized in relation with each other.”36 Suggesting a confluence with Scheerbart, his work then progressed to incorporating “machine technology” that drew on light, glass, scrap-metal parts, and color to produce new modes of “glass architecture” that would use transparency to recalibrate the viewer’s sense of modern space.37 These dual emphases for color—on systematizing harmony and on engaging humanely with new chromatic technologies—are in part what made Moholy-Nagy such an ideal candidate for the Bauhaus. After Itten, Gropius needed collaborators more open to the new industrial direction of the school, as he sought to prove the practical value of the Bauhaus for manufacturing, ideally to attract corporate sponsorship.

Moholy-Nagy approached color as a Constructivist, thinking scientifically and technically about creative production.38 He was also well acquainted with Ostwald’s scientific work and engaged with it throughout his time at the school. For instance, in 1924, he wrote about the usefulness of “Ostwald color charts” for creating his Construction in Enamel series (aka Telephone Pictures, 1923) in that they allowed one to designate over the phone the exact, standardized colors to be used by a factory printer.39 He was also involved, with Bayer and Gropius, in arranging Ostwald’s visit to the school in 1927, during which he learned of Ostwald’s color organs, which were twofold. On the one hand, as Ostwald had explained in an article in De Stijl in 1920, he constructed his “Farborgel” (color organ) as a cabinet for organizing the harmonies of color powders.40 This was not a color-music device, but rather drew from the musical analogy with color to create an elaborate, three-dimensional boxlike device for charting color harmony. According to Ise Gropius’s diary, he donated a version of the Farborgel to the Bauhaus during his visit.41 In addition, however, she describes a color-music device that Ostwald also developed and offered to the school:

He told us also about a new invention of his, an apparatus for color-light-music which is supposed to become very superior to the one by Laszlo. He only hasn’t the time and inclination to concern himself with the realization of this thing and offered it to G[ropius] who, of course, had to decline since we have neither the people nor the money to successfully get it going.42

In these comments, Ise Gropius provides a remarkable confluence of color standardization with color music through Ostwald’s connection to the Bauhaus. Like Newton, who proposed a harmonic connection between color and the diatonic scale, Ostwald attempted to extend the color-music analogy inherent in his Farborgel into actual practice through a new apparatus for color and light projection.

This was certainly of interest to Moholy-Nagy, for as Ise Gropius indicates, by 1927 he had been engaging with color-light-music in conjunction with cinema for a number of years, as is evident from his dazzling and polemical Painting, Photography, Film. First published in 1925 and revised in 1927, the book brings together color-music, science, and film at the Bauhaus. Assembled, written, and designed in the summer of 1924 at the end of his first year at the school, the book famously called for, and embodied in its layout and imagery, a new mode of seeing and sensing through machine technology, including film and color music. Delving into debates about photography and art, the book was at the forefront of modernist interest in film and photography, and it would prove influential on aesthetic developments in Weimar Germany. It was, for instance, an exemplar of the New Typography movement of the decade and was also taken up extensively by theorists such as Walter Benjamin, from One-Way Street through his seminal writings on photography and film.43

Courtesy of © 2018 Estate of László Moholy-Nagy / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The first forty-five pages of Painting, Photography, Film are brief essays—some new, some drawn from Moholy-Nagy’s earlier publications. Its second part comprises illustrations, primarily photographs collected from illustrated magazines (and a few by Moholy-Nagy, particularly in the second, 1927, edition of the book) along with filmstrips, with a section in the middle on the score for the Bauhaus color-music experiment Farben Licht-Spiele (Color Light Display) developed by Ludwig Hirschfield-Mack and Kurt Schwerdtfeger. The book concludes with Moholy-Nagy’s unfilmed scenario, “Dynamic of the Metropolis,” which he worked on between 1921 and 1924.

Recent analyses of Painting, Photography, Film have called attention to how its visual design plays a pivotal role in the book’s overall theoretical arguments about photographic and cinematic perception.44 For Moholy-Nagy, new technologies of production and reproduction expanded human perception: the photographic camera could “make visible existences which cannot be perceived or taken in by our optical instrument, the eye; i.e. the photographic camera can either complete or supplement our optical instrument, the eye.”45 Situated firmly within Bauhaus pedagogy, Painting, Photography, Film was meant to educate the viewer into this new mode of perception, not only with its text but fundamentally through its design and visual composition. For Moholy-Nagy, new technologies transformed the style of modern design in tandem with developments in the human sensorium; aesthetically, these are reciprocal changes in his theory and practice.46 The technical abstraction of modernist practice thus served a useful function in the educational reform tradition that Moholy-Nagy, and more broadly the Bauhaus, worked within. He noted of photography (which Benjamin cited several times): “The limits of photography cannot be determined. Everything is so new here that even the search leads to creative results. Technology is, of course the pathbreaker here. It is not the person ignorant of writing but the one ignorant of photography who will be the illiterate of the future.”47 Photography and film were thus useful forms for the production of a basic visual literacy.

Further, the design and organization of Painting, Photography, Film aims reflexively to educate the reader and viewer of the book about the dynamics of the modern pictorial environment—to inculcate a new mode of visual literacy. However, in considering the photographic and pictorial significance of the book, it is also important to recognize what it leaves out: color—an element central to its theoretical work but unrepresented visually, given the technical and financial confines of color reproduction at the time. Moholy-Nagy also positioned photography with the chiaroscuro effects of light, which, along with the technical reproduction of newspapers, had led to a growth of “colourlessness and grey” in the rapidly moving modern world, which Painting, Photography, Film visually replicates.48 This did not diminish the importance of color but amplified its necessity in artistic creation to protect against a diminishing of the color sense through the “atrophying of our optical organs” in a black-and-white medial environment.49 Color, largely beyond the mass reproduction of photography of the time, remained firmly within the domain of painting, as in the abstractions of “absolute painting,” and in an expanded way “kinetic compositions,” “color music,” and Absolute Film. In these ways, the moving image for Moholy-Nagy was surprisingly more aligned with painting, even as it surpassed it, than with photography. While the visual element of the book is rooted in black-and-white photography, color lies visually beyond its static nature within the domain of painting and its successor, the moving image.50

In making these arguments, Moholy-Nagy delineates how photography has transformed image production and reception, and he presents an important and often repeated argument about modern painting: rather than being invalidated by photography, the technology has liberated painting from the confines of realistic representation “to concern itself with pure color composition.”51 Focusing on color thus allows painting to leave the tradition of representational composition behind and focus instead on “the pure inter-relationships of colours and light-values, similar to what we know in music as composition in acoustical relationships; that is, the composition of universal systems, independent of climate, race, temperament, education, rooted in biological laws.”52 It is significant that in Moholy-Nagy’s account of the movement of painting into the nonrepresentational, he draws both on the parallel between color and music and also on science. As examined in the previous chapter, the correspondence between color and music has a long history dating back to the Greeks, but it also takes on particular valences in the 1920s. Before that decade, the notion of color music was predominantly connected to the occult and synesthesia. In line with what Itten developed through the preliminary course, such occult traditions of color continued through the decade and beyond. However, particularly for education, this approach to color was increasingly balanced by science and reconfigured for sensory uplift as a primary means of engaging and training the senses empathically to deal with the modern environment. As Moholy-Nagy delineates, moving images, or “kinetic composition so to speak enables the observer’s desire to participate to seize instantly upon new moments of vital insight” through images that are attuned to “the rhythm which governs our manner of living.”53 Abstract color in this configuration enables the viewer to feel into the rhythms of such kinetic art and realign sensory perception in ways in keeping with the notion of Einfühlung. This approach epitomizes what we have termed useful abstraction, or the practical ways in which nonfigurative color harmony could be used to educate the viewer’s senses, making them more color conscious.

Moholy-Nagy’s secular emphasis on the “biological laws of science” and the “psycho-physical” elements of color furthers such useful claims for abstraction and is indicative of the ongoing transformation of educational approaches to color at the Bauhaus.54 In addition to the liberation from representation brought by photography, such renovations of color allowed for the rise of Absolute painting: “Biologically conditioned expressions of these relationships or tensions—be it conscious or unconscious—results in the concept of absolute painting. In fact these conditions have at all times been the true content of colour composition.”55

In relation to this chromatic mode of education, it is helpful to return to the place of moving-image technology in Painting, Photography, Film. Progressing from a section on color and easel painting, Moholy-Nagy takes up static and kinetic optical works and provides a remarkably contemporary account of color music and Absolute Film. Contextualizing the moving image in relation to painting, he notes the technical basis of recent changes in aesthetic practice:

The development of new technical means has resulted in the emergence of new fields of creativity; and thus it is that contemporary technical productions, optical apparatus: the spotlight, the reflector, the electric sign, have created new forms and fields not only of representation but also of colour composition […] The moving, coloured figures (continuous light displays), however, which are today deliberately screened with a reflector or projector open up new expressional possibilities and therefore new laws.56

Later accounts of filmic abstraction in the 1920s typically begin with color organs and color music, particularly when emphasizing the spiritual roots of these movements. Writing about Fischinger, for instance, William Moritz notes that “having studied Pythagoras, alchemy, and Buddhism, he was fascinated by the notion that every element and object contained an essential personality that could be revealed by the visionary artist who found a technical formula through which the material could speak for itself.”57 These are important connections, and indeed, Moholy-Nagy turns shortly to color music—to Isaac Newton’s, Louis Bertrand Castel’s, and Alexander Scriabin’s use of color organs. However, before doing so, he begins his account with electrical signs and spotlights—with popular culture and advertising technologies—rather than the occult, in keeping with the industrial bent of the Bauhaus that he helped usher in.58 Unlike Itten, Moholy-Nagy’s approach to color pedagogy is related instead to the technical emphasis of the book—that medial innovation transforms sensory-aesthetic practice. This line of argument illustrates the ways in which the historical avant-garde was fundamentally engaged with vernacular practices of the time, interrogating their potentials to transform creative practice and its relation to the public. In fact, the modernist turn to film was part of this vernacular engagement, specifically with a new medium that was becoming one of the most pronounced emblems of interwar mass culture.

It is within this vernacular context that Moholy-Nagy lays out a brief but cogent account of recent experiments with the moving image, drawing connections from Absolute painting and popular light displays through, among others, Scriabin, Ruttmann, Viking Eggeling, and Hans Richter. Even as their work with color emerges from painting, they transform it by incorporating time and motion into their dynamics. As Moholy-Nagy notes of Richter, he “has thus come near to creating a light-space-time continuity in the synthesis of motion.”59 Through this configuration, the stakes of his interest in electric signs and spotlights become clear for his account of moving images: in building from the work of painting, these works expand the place of artistic practice into everyday life, along with the sensory capacity to perceive and empathetically experience it.

Courtesy of © 2018 Estate of László Moholy-Nagy / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Moholy-Nagy further develops his argument through his discussion of Farbenlichtspiele, the Bauhaus color-music experiments carried out separately by Kurt Schwerdtfeger and Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack. He notes that Hirschfeld-Mack’s version:

worked with reflected light and shadow plays which in the overlapping and movement of coloured planes represent the most successful practical moving colour-composition yet. Hirschfield-Mack’s intensive work has produced equipment specifically designed for shooting continuous film. He was the first to reveal the profusion of the most delicate transitions and unexpected variations of coloured planes in motion. A movement of planes, prismatically controllable, which dissolves, conglomerates. His latest experiments go far beyond this point, which resembles the colour-organ in character. The establishment of a new space-time dimension of radiating light and controlled movement becomes ever clearer in his spinning and plunging bands of light.60

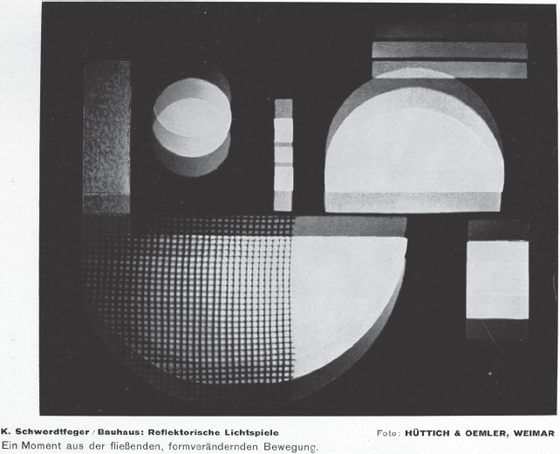

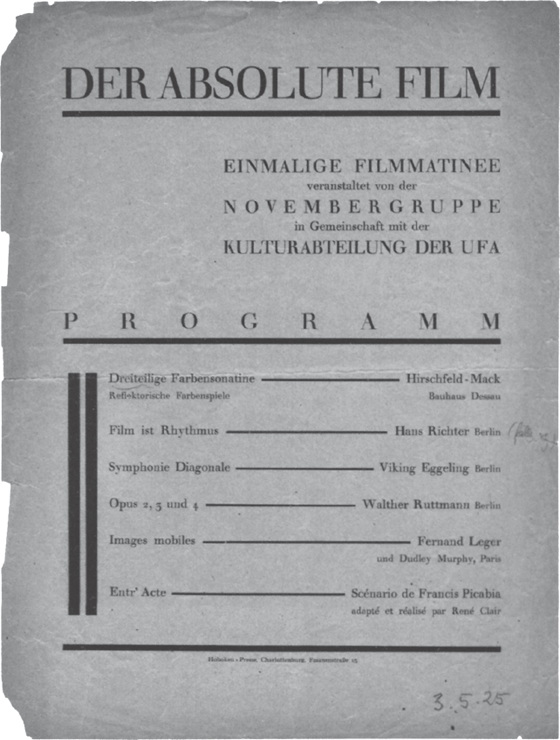

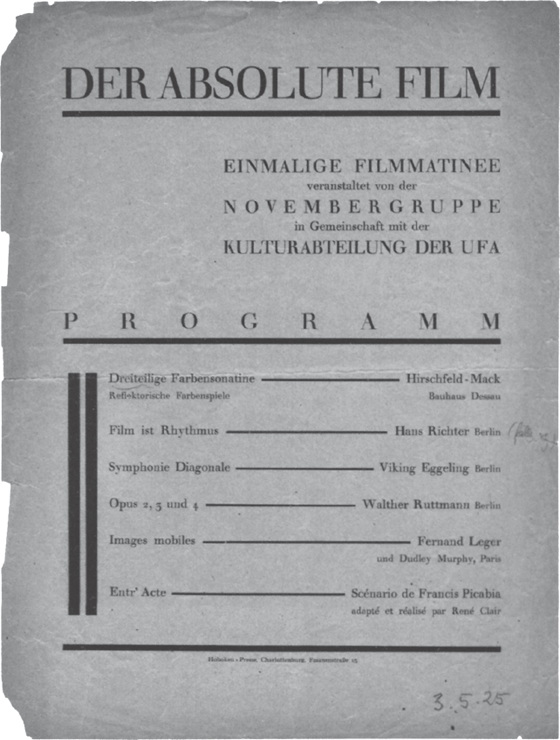

Hirschfield-Mack has received more attention for these light displays, but it was Schwerdtfeger who initially experimented with colored projection at the school in collaboration with Josef Hartman (color plate 4.2).61 Schwerdtfeger, a student specializing in sculpture developed Reflektorische Farblichtspiele (“Reflecting Colour-Light-Play”), which was first displayed at Kandinsky’s home on June 21, 1922, as part of the Bauhaus Lantern Festival. Schwerdtfeger’s work was conceived as an abstract play in which an operator would manually adjust a cardboard stencil system in front of a light source that would rear-project moving colored shapes onto a screen. Hirschfeld-Mack was a student of the printing workshop who had previously studied color with Adolf Hölzel and concurrently led a color seminar at the Bauhaus. Over the next year, he adapted Schwerdtfeger’s idea, adding additional operators to the projection device. He premiered it in 1923 at the Bauhaus and continued to exhibit versions throughout the 1920s. The most renowned example is Dreiteilige Farbensonantine: Reflektorische Farbenspiele, which was performed at the famous Absolute Film matinee screenings at the sold-out, 900-seat Ufa Palast in Berlin on May 3 and 10, 1925, alongside Eggeling’s Symphonie Diagonale (1924), Ruttmann’s Opus 2, 3, and 4 (1923, 1924, 1925), Richter’s Film Ist Rhythmus (a likely mixture of his Rhythm 21 and Rhythm 23, 1921 and 1923, that was only ready to be screened at the second showing), and curiously shifting to French material as we will discuss later, Fernand Leger and Dudley Murphy’s Ballet mécanique (1924) and René Clair’s Entr’acte (1924). The screening, with variations, was repeated in Hannover on May 22, and yet again at the Bauhaus, in Dessau on March 21, 1926.62

Image courtesy of Deutsche Kinemathek—Museum für Film und Fernsehen, Berlin, Schriftgutarchiv.

Published in the same year as the Berlin screenings, Painting, Photography, Film brings together Schwerdtfeger’s and Hirschfield-Mack’s Bauhaus experiments in color music with Absolute Film and underscores key aesthetic traits shared by these various works. All were invested in the abstract potential of light and movement, though certainly in differing ways, particularly with Entr’acte. Most of the works also brought color into the mix, as with Dreiteilige Farbensonantine: Reflektorische Farbenspiele, the Opus films, Rhythmus 25, and likely Ballet mécanique. These were not viewed as autonomous works of l’art pour l’art, divorced from utilitarian and industrial aims. Indeed, just as the Bauhaus was seeking industrial support at the time, the Berlin screening was cosponsored by the socialist, avant-garde Novembergruppe (with which Gropius, Moholy-Nagy, and Bruno Taut were affiliated) and the educational division of Universum-Film AG (Ufa), the largest and most renowned German studio of the day.63 They are thus cinematic exemplars of the cross-field and intermedial networks around color that we track throughout this book.

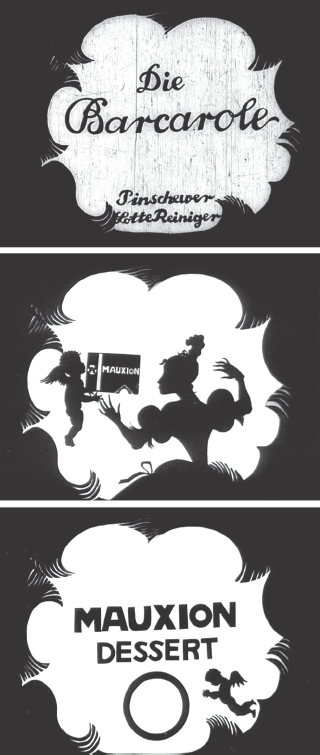

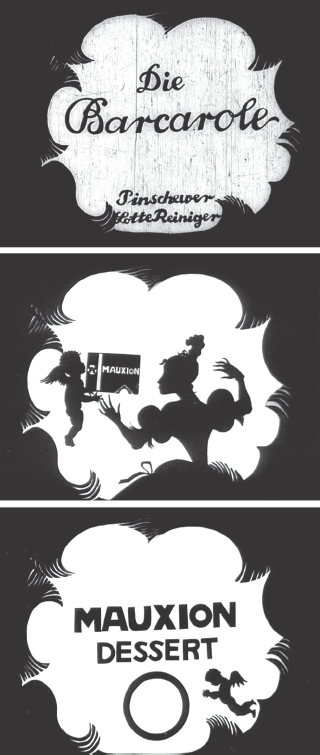

The Berlin screening and the moving-image works that Moholy-Nagy traces in Painting, Photography, Film, are also chromatic exemplars of useful abstraction in the 1920s. These works have significant ties to the aesthetic culture of their time, as well as to industrial production and especially educational pedagogy. The moving image was central to the visual transformation of the urban world of Weimar Germany, as film was a thriving aspect of its intermedial display culture, not only through the feature films produced but also with its incorporation into advertising.64 Filmmakers such as Ruttmann and Lotte Reiniger were important not only for their artistic productions but also for the sponsored filmmaking they engaged in, particularly in collaboration with Julius Pinschewer, who was the most prominent producer and distributor of advertising films in Germany during that era.65 Indeed, as Michael Cowan has examined in detail, rather than being isolated activities, the imbrication of artistic and sponsored filmmaking was key in Germany for the circulation of aesthetic knowledge and practice. Advertising theory turned to educational, aesthetic, and psychophysical research into Einfühlung to pioneer new modes of visual display, and this in turn was appropriated back not only into advertising films but also into Absolute Film and Bauhaus practice.66 Kurtz also noted these confluences in reference to the color in Ruttmann’s works (color plate 4.3):

The colour is particularly exciting. Ruttmann uses an unusually rich palette, with a new mellow hue for every nuance of movement. Sentimental, sharp, happy, and cheerful gradations of colour change with the progression of curves, the lurching forward and the twitching back of his squares and rectangles. One feels that these organically swelling shapes eat each other, devour each other, charge at each other in combat, embrace each other lovingly: it’s a drama of colourful shapes that automatically compels an emotional reaction. Ruttmann has attained considerable success with an industrial advertising film of this sort, which clearly demonstrates how expressive these colourfully-moving shapes are.67

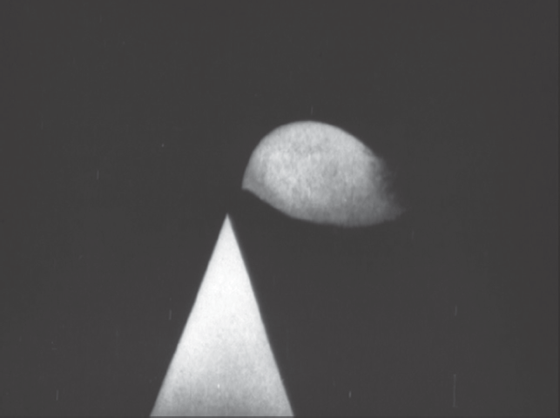

Framing color in Absolute Film in relation to technology, science, and industry illustrates how knowledge transfer, as discussed in chapter 1, was also being adapted for aesthetic and pedagogic ends. Filmmakers and artists such as Ruttmann, Richter, and Moholy-Nagy believed that in order to release the moving image’s power, they had to purify its form, reducing it to the basic, essential technical properties of the medium—light and moving colour—as opposed to espousing an iconic, photographic ontology. Richter argued for the revelatory function of abstract form: “It is obvious that to get to the spirit, the idea, the inherent principle and essence one has to destroy the appearance. Not in a physical way as much as in one’s own eye. To forget about the leaf and to study the oval; to forget about its colour and to experience its sensation.”68 He worked toward realizing this ideal through his experiments with color in Rhythmus 23 (1922)—originally titled Fuge in Rot und Grün (Fugue in Red and Green)—but because of the amount of labor involved in hand coloring, he was unable to complete the film in color. However, he continued to experiment with color in his vertical-roll works on canvas, such as Orchestration der Farbe (Orchestration of Colour, 1923), and in his nonextant film Rhythmus 25 (1925), a work that he meticulously colored frame by frame.69 In these experiments, the pictorial base of the image gives way to the contrapuntal play of contrasting colors and shapes embedded in the emulsion of the films. When experiencing color’s orchestrated movements and transformations in these abstract works, Theo van Doesburg argues:

The spectator will look into a completely new world, he will be able to follow the whole process of this dynamic light-sculpture rather like the orchestral work of Schonberg, Stravinsky, or Antheil. From this it follows that the spectator space will become part of the film space. The separation of “projection surface” is abolished. The spectator will no longer observe the film, like a theatrical presentation, but will participate in it optically and acoustically.70

Doesburg’s relationship with the Bauhaus was critical and tempestuous, even more so than Itten’s, but he was also influential on many of its members, and he and Moholy-Nagy were well acquainted before Moholy-Nagy even came to the school.71 The idea of optical and acoustic participation in the moving image runs through Moholy-Nagy’s work and his theories of color and light projection, and indeed gets to the pedagogical center of the interest in color and the moving image at the Bauhaus. Bayer’s sketch for a cinema in 1924–1925 provides another version of this chromatic space, as does the kaleidoscopic projector in the Glass House of Scheerbart and Taut. Combining the industrial art of film with chromatic abstraction, these utopian works of pedagogy aimed to craft a useful and empathetic forms of aesthetic experience, in which, as Moholy-Nagy puts it, “eyes and ears have been opened and are filled at every moment with a wealth of optical and phonetic wonder.”72 Framed in institutional relation to art education at the Bauhaus, color and the moving image function in this abstract register to produce a sensuous mode of visual literacy—an avant-garde version of color consciousness. Aligned initially with pedagogies rooted in the occult, such as the Waldorf system, and subsequently with more scientific and standardizing approaches of the 1920s such as Ostwald’s, this hybrid avant-garde mode of useful abstraction aimed to train the senses, making them more capable of navigating the chromatic landscapes of the 1920s.

The Saturated Screen of German Expressionism

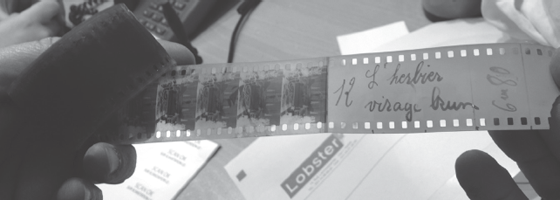

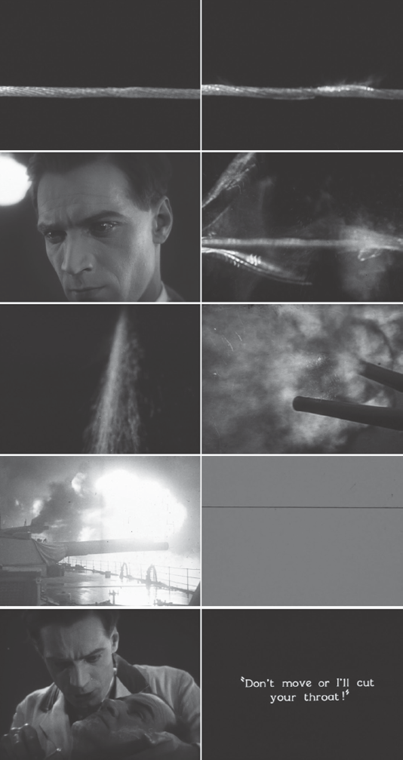

Alongside the avant-garde works of Absolute Film and the Bauhaus, there was also a range of chromatic experimentation in German narrative cinema of the decade that forms a crucial context for the more abstract work simultaneously being produced. More than simply a background for the avant-garde, it is also worth delineating the aesthetic parallels between such restricted and large-scale forms of chromatic production, particularly in light of Kurtz’s expansive account in Expressionism and Film. To trace these relations, our analysis shifts emphasis formally and technically to take into account the archival legacy of color in German cinema. Given the years of archival disregard for applied forms of color in silent cinema, it is only now, in light of recent restorations such as Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (Robert Wiene, 1920), Der müde Tod (Fritz Lang, 1921), Nosferatu (F. W. Murnau, 1922), and Die Nibelungen (Fritz Lang, 1924), that the tinted and toned hues of the iconic works of German Expressionism can finally be assessed in terms of their saturated palettes.

Expressionist cinema is of course a contested category of the Weimar era, as Thomas Elsaesser and others have detailed, and we recognize the various cultural, stylistic, and economic currents at play in these films of the early 1920s that Expressionism does not fully encompass.73 Indeed, for our purposes, it is their hybridized mode that makes these works exemplars of the intermedial style of the decade, for it is through those hybridized junctures that color comes to the fore. The films work across various fields of aesthetic production, and their use of tinting and toning reflects chromatic adaptations of theatrical and painterly Expressionist style, German Romanticism, and modernist design. For instance, as we discuss in more detail below, there are direct continuities between these works and Absolute Film through Ufa’s employment of Walter Ruttmann on Fritz Lang’s Die Nibelungen: Siegfried (1924) to animate the “Dream of the Hawks” sequence—a foreboding dream that Kriemhild has about the tragic fate of her future (yet unknown) husband Siegfried, in which a white/lavender hawk is killed by two black eagles.

In terms of cultural prestige, Ufa producer Erich Pommer’s famous explanation of the Expressionist phase of production was that it was primarily a marketing gambit following the economic hardships of the war: “The German film industry made ‘stylized films’ to make money…. Germany was defeated: how could she make films that would compete with the others? It would have been impossible to try and so we tried something new; the Expressionist or stylized films.”74 In many ways, this was the inverse of Gropius’s charge and Moholy-Nagy’s implementation of the merger of art education and the avant-garde with industrial and scientific practice: Pommer moved in the opposite direction, from the industrial to the avant-garde, yet with similar vernacular modernist results. Economic and industrial pressures certainly shaped artistic style during the decade, and Expressionism served as a useful marketing label of cultural distinction for Ufa, yet at the same time the aesthetic innovations of many of these works were substantial.75 This was not only the case in Germany, for in many ways such economic and industrial pressures on stylistic form parallel what Richard Abel has characterized as the “narrative avant-garde” in France during the same decade, in which modernist techniques were also adapted for narrative cinema, including dynamic color design.76 Such modernist adaptations in Weimar film were relatively more Romantic in nature, invoking Expressionist as well as Vienna Secessionist Arts and Crafts traditions that were more in line with the Bauhaus’s Weimar phase than with its forward-looking Constructivist-scientific approach in Dessau. In practice, though, such distinctions are not always clear-cut, as analyses by critics such as Kurtz and Lotte Eisner demonstrate through their invocation of Romanticism, psychology, and psychophysics to explain both Expressionism and Absolute Film.

In the popular imagination, the works of Expressionist film were long thought to have been in black and white, in part because of their rich chiaroscuro effects, such as the iconic shadow of Count Orlok climbing the stairs in Nosferatu. Production designer Hermann Warm famously suggested that “the filmed image must become graphic art [Graphik]”—translated as a “drawing brought to life” by Siegfried Kracauer and “engraving” by Eisner, emphasizing the films’ distinctive uses of light and shade.77 Later, in The Haunted Screen, Eisner discusses the black-and-white style of Murnau’s Nosferatu: “the grisaille of the arid hills around the vampire’s castle”—grisaille being a gray, textural style of painting.78 Her influential book and Kracauer’s From Caligari to Hitler were richly illustrated with black-and-white production stills, which coincided with the circulation of black-and-white reduction prints, and eventually video copies, that were the main means through which Expressionist films were accessed and canonized after the 1920s. As a result, the provenance of these works, as of so many silent films, has been stripped of color for much of the past century. Yet, as recent restorations illustrate, these films were intricately colored through tinting and toning effects when they were originally released. In Eisner’s defense, she was one of the first critics to note this, specifically regarding Caligari: “modern prints of this film (originally tinted in green, steely-blue and brown) give no idea of the unity of composition afforded in the original by the images and their titles.”79 In line with her suggestion regarding the unity of chromatic design found originally in Caligari, it is worth examining how the tinting and toning patterns in Expressionist film resonated more broadly with the aesthetic culture of Weimar Germany.

Throughout silent cinema, there were a variety of reasons for tinting and toning films. The monotone or duotone (when tinting and toning were combined) color schemes that dominated the era in part helped distinguish denotatively scenes and settings from one another. A green tint might indicate a shift to a wooded scene, whereas an amber tint could illuminate an interior scene under artificial light, and of course red would often be used for fire and blue for night scenes. This blue tinting was particularly useful, given the amount of day-for-night filming that occurred during an era when the insensitivity of film stocks precluded actual night shooting—hence the use of blue to provide a clear indication of the hour. Beyond such denotative schemes, tinting and toning were also used connotatively, to convey the mood and atmosphere of scenes: pink might indicate a romantic scene, light blue a calm one. In Theory of Film (1960), Kracauer reflects back upon these uses of color in silent cinema, noting that tints were meant to “canali[ze] the spectator’s emotions”: “Shades of red helped amplify a conflagration or the outbreak of elemental passions, while blue tints were considered a natural for nocturnal scenes involving the secret activities of criminals and lovers. The different hues plainly served to establish audience moods in keeping with the subject and the action.”80

Such ideas about the interrelation of color and emotion are ancient, running back at least to the Greeks. However, the proximate connections for Kracauer and Weimar color theory run through psychophysics and Einfühlung, as discussed earlier. The emotive and physiological aspects of color were thought to canalize, shape, and direct spectator reception across the domains of film, advertising, architecture, and art. Such aesthetic approaches to tinting and toning can be seen in various exemplars of Expressionist film. At times these hues function denotatively, at others connotatively, and both of these approaches could be harnessed for narrative legibility. However, given the variability of the coloring patterns in the print records of many of these films, in which competing tinting and toning patterns often exist for the same film across multiple prints, definitive narrative readings of the hues are difficult. It is often impossible to determine what the narrative colors might have been originally when the patterns varied from print to print, particularly between domestic and foreign release versions. Intermedial analysis, though, does bring out much in these films, for even if the specific hues often varied, their saturations and generalized color palettes resonate strongly with their contextual referents and aesthetic paradigms.

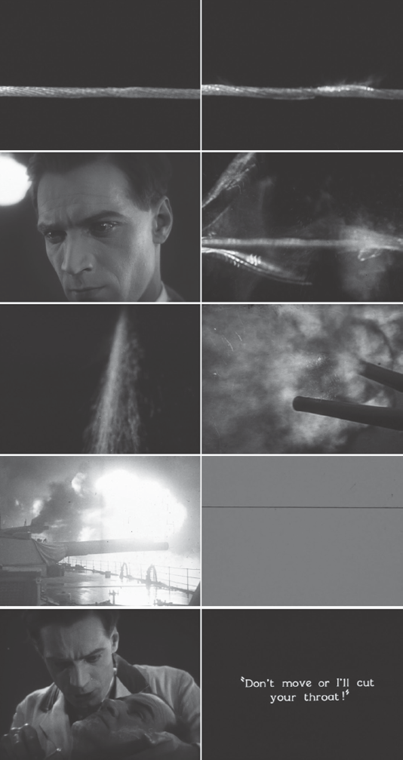

Take, for instance, Fritz Lang’s two-part epic Die Nibelungen: Siegfried and Kriemhild’s Rache, which at first seems to be an outlier in terms of its tinting scheme. The film is an adaptation of a thirteenth-century epic poem about the exploits and subsequent murder of Siegfried and the ensuing revenge wrought by his widow Kriemhild. Lang’s two-part adaptation is nearly five hours long, and curiously most (though not all) surviving prints and negatives of the film suggest that it was tinted almost entirely in a golden-orange hue when released.81 The only major alternation found in most of the extant prints is Ruttmann’s brief “Dream of the Hawks” sequence foretelling Siegfried’s death, which was tinted lavender. Considering both parts together, a film of this length that is almost entirely colored in a single tint seems strange, as the standard was to use multiple, alternating tints and tones with black-and-white sequences to create spatial and emotional distinctions. However, Anke Wilkening, who restored the film for the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung, has noted examples of other German features tinted in similar ways at the time: a U.S. export print of Herr Tartuffe (F. W. Murnau, 1925), for instance, was also tinted in a golden-orange hue, as were export prints of Faust (F. W. Murnau, 1926). A technical explanation might be that the hue may have made it difficult for foreign exhibitors to dupe the prints illegally, as orthochromatic stocks would not have easily distinguished the tinted hue from the grayscale image because orthochromatic stocks, unlike panchromatic ones, cannot register the reddish-orange color spectrum.82

Such uniform approaches to tinting may have also resulted from technical changes in print processing during the decade. With the predominate move from shorts to feature films in the 1910s as the international film industry was solidifying, there was a growing need to reduce the number of physical splices in positive film prints. By the mid-1920s, internegative stocks became available that allowed for the duplication of a camera negative, which allowed for easier printing with less wear and tear on the original negative.83 This coincided with various laboratory changes in print production. Negative cutting, print timing, and continuous-contact printing became more refined during the era. Negative cutting—editing a negative into final narrative order—allowed laboratories to produce spliceless positive prints that held up better, with fewer breaks during projection. Companies such as Bell & Howell developed high-precision negative-splicing machines to facilitate this process.84 The timing of internegatives for positive printing—to ensure that each shot of a finished film print was properly exposed—also became much more elaborate and automated. As Kodak technician J. I. Crabtree explains, before the process became increasingly systematized in the 1920s, printing-machine operators carried out print timing by judging the exposure of the image by eye and adjusting the exposure light manually shot by shot.85 Beginning in the 1920s, light sensitometers were deployed to analyze shots in advance for printing, leading to the integration of timing cards (containing exposure information for each shot) with continuous-contact printers that allowed for the mechanical adjustment of light exposure during printing, thus automatically compensating for variations in exposure across shots on the negative.86 Before the development of this relatively automatic printing system in the mid-1920s, negatives were assembled in exposure and tinting order for easier processing, as tinting continuities tended to follow exposure changes—for example, interior versus exterior scenes or day versus night. After duplication, release prints would then have to be spliced individually into continuity, with the shots properly ordered. With the shift to more automated modes of duplication, negatives could be cut into continuity, which simplified the printing and editing process, as the processed positive prints required less editing. However, tinted and toned sequences would still need to be color processed after printing and spliced back in for continuity, along with intertitles. Colored sequences continued to be grouped together in tinting order during printing, but there is evidence that with the move toward automatic duplication and internegatives, tinting and toning patterns became less complex and more uniform to avoid unnecessary splices, as in the examples of Die Nibelungen and Herr Tartuffe and, as will also be discussed, of Caligari and Nosferatu.

For these various technical reasons, single-tinting practices may have been relatively widespread in Germany, though it is difficult to ascertain from surviving print records, as this style of tinting was not seen as being important to preserve. Later copies were typically made in black and white (with panchromatic stock that could register the tinted image into grayscale effectively). In archival practice after the silent era, there was a general disregard for preserving tinting and toning in nitrate prints, as this type of color was by and large believed to be an inessential addition to silent film—the black-and-white shapes and lines were primary, as opposed to the ornamentation of color. Uniform tinting likely exacerbated the archival bias, as it functions largely outside of the denotative or connotative modes that were dominant during the era.

As Wilkening suggests, there may have been additional reasons for the uniform coloring—specifically, the reduction of contrast in the image.87 Lang, with his cameraman Carl Hoffman, had been experimenting for some time with elaborate lighting effects that allowed them to shoot night scenes at night, thus avoiding the predominant mode of day-for-night filming that subsequently required blue tinting to code the scenes as night. As Lang later explained in a letter to Lotte Eisner in 1968, “I never liked the blue paint which was used in those times to ‘tint’ day-for-night scenes so that they became ‘night scenes.’”88 Such an emphasis on dynamic lighting effects and night filming is in keeping with the trend of late silent cinema that Erwin Panofsky identified as a “dynamization of space,” in which the mise-en-scène becomes increasingly expressive through lighting and unchained camera effects.89 In the context of color, such expressive effects would make tinting relatively redundant for a formally innovative filmmaker such as Lang. However, given the nature of orthochromatic stock in the 1920s, night scenes filmed in low light would have suffered from high contrast, and the dominant golden tint may have been used to mute the chiaroscuro effects and reintroduce a level of relative grayscale within the image. In addition, during the silent era, some people believed that exposing viewers to too much contrasting black-and-white imagery for a prolonged period of time might damage their eyesight, much in the way that snow blindness occurs.90 Thus, this technical use of tinting may have been thought to serve specific physiological purposes.

Beyond technical explanations, there is also an intermedial case to be made for the uniform coloring of Die Nibelungen as being in keeping with the “total design” look of the film in which, as Tom Gunning has noted, “Nothing…is natural.”91 In the set and costume designs for the film, Lang famously drew from Carl Otto Czeschka’s eight double-paged, relief-printed illustrations for a children’s edition of the epic poem from 1909.92 Czeschka was part of the Vienna Secession, an Austrian Arts and Crafts movement established in 1897 under the leadership of Gustav Klimt. Like the Bauhaus two decades later, the movement was immersed in a variety of modern styles—including Romanticism, Postimpressionism, Expressionism, and Jugendstil—and aimed for a unity of aesthetic expression across the arts, from painting to architecture to graphic design and folk art. Lang, who was born and educated in Vienna, began his professional career there in the 1910s as a graphic artist, influenced by Viennese modernism.93 His borrowings from Czeschka are readily apparent: the illustrations of Kriemhild’s and her sister-in-law Brunhild’s costumes, with their Jugendstil surface designs, are systematically replicated in the film’s costumes, as are various other architectural and design motifs.

In this sense, Lang’s Die Nibelungen embodies Hermann Warm’s Expressionist dictum that film “should become graphic art.” However, Lang’s intermedial adaption went beyond the formal line art of Czeschka’s illustrations. As the book prints reveal, color too was a vibrant element of Czeschka’s graphic art. Blues and reds are present, but gold is the hue that dominates these illustrations—the color most associated with the Vienna Secession, as in Gustav Klimt’s “golden phase” of paintings that were made with actual gold leaf marking their opulent and critically successful style. Gold is everywhere in Czeschka’s images: in Kriemhild’s hair and necklace, across shields, lances, and boat sails. As with Klimt’s layering of materials to produce a heavily textured and haptic quality across the surface of his paintings—as in his famous Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907)—Czeschka’s golds, while uniform in their relief-printed application, also shimmer on the page because of the ink used, which was likely produced by trapping golden-hued bronzing powder in printed varnish. It is this type of textural density that the golden-orange tint brings to the grayscale of Lang’s Die Nibelungen, making apparent the film’s chromatic affinity with the prestige of Czeschka and the Vienna Secession.

One must be judicious in such a reading, though, given the apparent usage of uniform tinting in Germany at the time, as the matching colors could simply be coincidental. There is, however, other contextual evidence in the film’s promotional material that its golden aura was designed in reference to the illustrations. One of the iconic posters for Siegfried illustrates a scene from the film in which the hero, astride a horse along with his twelve kingly vassals, crosses a drawbridge over the moat into the castle of Worms. Siegfried is positioned in the upper right of the poster, nearest the castle entrance, and also nearest the sun, against which he is silhouetted. Picking up on the film’s tint and Viennese influence, radiant and dappled golden-orange light flows out from Siegfried across the poster. The scene is also illustrated by Czeschka, but at an earlier moment than the poster: just as the drawbridge is being lowered to welcome Siegfried and his vassals, all clad in gold. Similarly, even in certain editions of Thea von Harbou’s tie-in novel Das Nibelungenbuch (1923), the illustrations, derived from film and production stills, are toned in orange-brown hues, likely through the photogravure or rotogravure printing processes.94

Given the intermedial emphasis on color in and around the film, its golden-orange tints appear to be more than a technical afterthought. Deployed not only to mute the contrast of the image, the color provides a resplendent and shimmering aura grounded in the Viennese decorative aesthetic to illuminate the mythic world of the film. For instance, in an ill-fated scene outside the cathedral of Worms, Brunhild ignores Kriemhild’s and Siegfried’s royal courtly ranks and insists that, as the queen of Burgundy, she should enter before Kriemhild. The confrontation that emerges sets in motion the fated tragedy that climaxes in Siegfried’s murder. This pivotal scene was also illustrated by Czeschka in a double-page illustration, showing Brunhild and her maids-in-waiting on the left page robed in black and Kriemhild on the right page in blue, with her maids in white. With their eyes locked on one another across the double-page layout, Brunhild raises her hand, barring Kriemhild’s way forward. Textured gold paint sparkles across their elaborately designed geometric costumes, triangular jewelry, and crowns, and over the shields and armor of soldiers behind Brunhild (color plate 4.4). In Lang’s version, he both emulates and expands Czeschka’s illustration (color plate 4.5). In a series of shots, the two women confront each other repeatedly, raising their arms in succession to block the other’s way into the cathedral as the confrontation escalates. As in Czeschka, Brunhild is dressed in a black dress, while Kriemhild is in white rather than blue, and their maids are robed similarly. The two women’s triangular jewelry and crowns pick up the golden-orange tints of the film, making the designs shimmer across the shots. These graphic elements are further drawn out in the scene, as in much of the film, through the slow staging of the performance that sculpts the characters into the total composition of the mise-en-scène. In their drawn-out confrontation, the golden aura Romantically illuminates—and allows the viewer empathetically to feel into—a mythic past beyond the natural world yet positioned at its fated point of dissolution: the golden aura of the image is destined to end in the apocalypse that follows in Kriemhild’s Revenge.

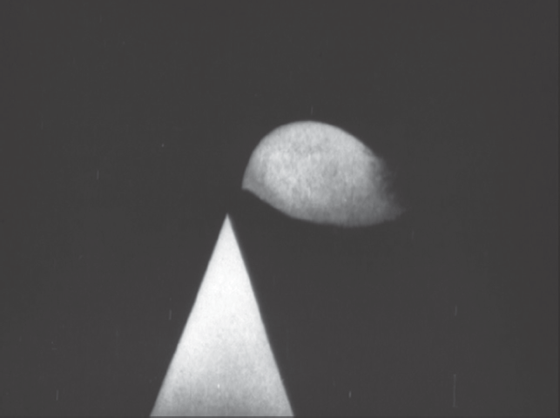

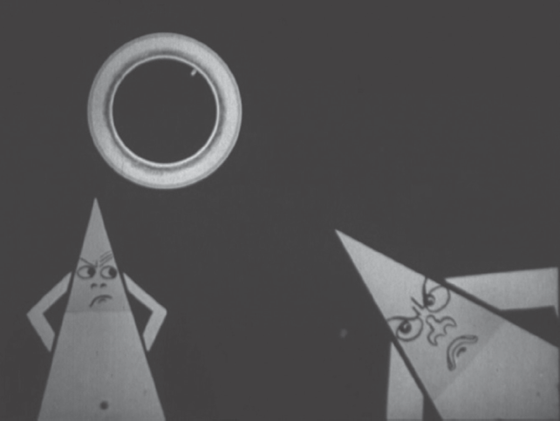

As Kurtz describes the film, specifically referring to Ruttmann’s animated contribution, “Decorative space is created through nuance of colour, through rhythmically ordered movement—without a search for counterpart in the organic world.”95 This fits the film’s overall, total design, both in its golden application of the Viennese design aesthetic and in its major digression from it, into the Absolute Film style of Ruttmann’s “Dream of the Hawks.” The shift in tinting, from golden-orange to lavender, marks both the diegetic movement into Kriemhild’s retelling of her dream and the relative change in film style. Lavender was a color that Ruttmann had worked with before—some of the swooping shapes in Opus 1 (1921, color plate 3.6) were momentarily hand colored in the hue—yet it never dominated any of his films as it does in the Siegfried insert, and it is doubtful that the precise tint would have been selected with Ruttmann’s previous films in mind.

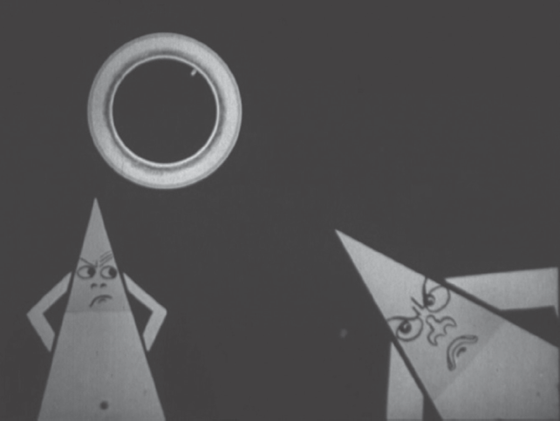

Rather than working from Czeschka’s elaborate illustration of the dream, Ruttmann’s sequence picks up visual motifs from the film itself, merging them with the Romantic tendencies of his Absolute style of the time. The preface to the dream sequence entails Kriemhild’s recounting the vision to her mother; the film cuts from an irised-in medium close-up in golden-orange of Kriemhild to the lavender animated sequence. Within Ruttmann’s body of work, the sequence closely aligns with his Opus I (1921) and his parallel, sponsored advertising film Der Sieger: Ein Film in Farben (1922), which he produced for Julius Pinschewer for Hannover Gummiwerke Excelsior.96 The dream begins abstractly against a black background with a rounded, irislike movement upward that reveals a roughly textured, chalk-drawn background, tinted lavender, against which a series of four black pillars with rounded tops pulses upward in the right corner of the frame. Opus 1 similarly opens with a sequential series of rounded, towerlike shapes pulsing upward, though in alternating blues, greens, and eventually reds and against a relatively smoother background. In the dream, the black pillars are then covered by black waves cresting over them, from the left and the right, eventually leaving the frame divided between a black bottom right corner and the left upper corner in lavender. A light lavender circle shape then appears, swirling around the upper left of the frame, moving much like the abstract shapes in Opus I, but as in Der Sieger, it then shifts into a figural object: a lavender hawk flitting through what now reads as the sky, in the upper left, until it rests upon the blackened ground in the bottom right. Two abstract, swirling shapes then begin to flit across the sky, until they stir the hawk from its perch and chase it across the frame. The blackened shapes transform into eagles that attack the hawk, culminating in the finale in which they go in for the kill, driving their beaks into the hawk at the center of the frame, as the frame itself collapses in abstract, triangular shards (similarly found in Opus 1 and Der Sieger) that also stab into the hawk, blackening the image as the dream ends.

The anthropomorphic nature of Ruttmann’s sequence calls attention to the Romanticism of his abstraction. As Gunning argues, the light shading of the hawk reflects the light-colored robes that Siegfried wears throughout the film, whereas the black eagles correspond to the dark robes and winged helmets of Brunhild and Hagan, who conspire against him.97 What unifies the sequence with the broader film, across the shifting tints and aesthetic styles, is the abstract surge toward total design in both line and color, exemplified by the back-and-forth merger of figural and abstract design elements in Ruttmann’s sequence, as well as in the film. These textured images craft empathetic spaces that are meant to resonate and emote through their elaborately constructed material effects. As detailed earlier, Ruttmann’s other works of Absolute Film are much more polychromatic, yet Die Nibelungen still works formally through the materiality of color, line, and shape to evoke emotional and empathetic resonances—even through the relatively monotonous yet auratic color design. Embedded in industrial as well as aesthetic codes, the systematic and technical nature of the film’s color effects makes them resonate with the modernist impulses delineated through the Bauhaus. Further, these intermedial and cross-field contexts provide the logic for the film’s color, much more so than narrative concerns.