The public is definitely color-conscious. Automobiles used to be sold on their mechanical perfection, but today the color of their bodies is an important factor. Fountain pens are colored, glassware is colored, there is color everywhere, and why shouldn’t people coming to your theatre to release themselves temporarily from a drab existence, also enjoy color?

—Edwin Sedgwick Chittenden Coppock, Motion Picture Herald (1934)

In the 1920s, the full impact of developments in synthetic coal-tar chemistry began to find chromatic expression in a range of artistic and commercial forms, particularly advertising, fashion, film, print culture, theater, architecture, and design. Widespread interest in color across these fields was shared through ideas about the unity of art forms—of synthesizing media to create effects that transcended the capabilities of discrete forms, as epitomized by Wagner’s notion of the total work of art, or Gesamtkunstwerk. Connections among hitherto disparate modes of experimentation were forged in the 1920s as a number of practitioners and theorists saw color as a revelatory force. The word “synthetic” is therefore doubly appropriate, referring not just to the application of vibrant synthetic colors produced chemically but also to the utopian synthesis of medial forms. The latter found expression in manifestations of what came to be known as “color music”—also called “visual music” or “mobile color,” terms used increasingly from the 1920s on—which referred to cross-medial artistic practices that combined colors, light, and/or music in a range of abstract patterns that were exhibited in a variety of venues. As cinema was developing as a classical institution characterized most visibly by the picture palaces that flourished in the 1920s as purpose-built structures for film exhibition, these glamorous venues were nonexclusive sites for a host of media practices exhibited in conjunction with feature films. Beyond narrative films, newsreels, and other short programs, picture palaces of the twenties also showcased chromatic light displays, color-music experiments, and resplendent stage prologues for films. These variety programs around feature films is where abstract, experimental practices were often integrated with more vernacular forms of cinematic entertainment, similar to what was later referred to as “expanded cinema,” in which mixed or multimedia exhibition events widened the synthetic field of vision “so far that they dissolve cinema itself as a separate entity.”1 In the 1920s, an immersive exhibition environment and culture extended beyond the projected image. A combination of high and low, avant-garde and vernacular forms exhibited at the same time and in the same space invited spectators to experience a synthesis of effects. The emphasis was—literally and metaphorically—on widening the field of vision in order to craft holistic experiences of art and entertainment that were uplifting, sensuous, and aurally and chromatically rich.

In Pierre Bourdieu’s conceptualization, avant-garde and vernacular art are usually seen as divergent, even competing, traditions within the field of cultural production, involving distinctive aesthetic forms and requiring acquired “aesthetic competence” from critics or spectators to appreciate their artistic value.2 While avant-garde experiments of the 1920s often represented the shock of the new, this chapter proposes that the simultaneous expansion of mass entertainment and instances of intermedial performance in popular venues promoted interrelationships between experimental and vernacular forms, constituting a chromatic version of what Miriam Hansen has described as the “vernacular modernism” of classical cinema.3 Even as there are crucial distinctions between avant-garde and vernacular forms of modernist expression, there were also dynamic exchanges occurring across these modes of production during the decade. Mobile-color and color-music practitioners did not rely on audiences’ having prior aesthetic competence about related artistic conventions. Much as avant-garde artists working in Germany, such as Walter Ruttmann, saw public advertisements as legitimate platforms for their work, the appeal of color music and mobile color was not confined to a narrow cultural elite. Commercial cinemas were appropriate places to showcase experimental innovations in lighting technology and electrical devices that manipulated color and music to accompany screenings of art and popular films. While the motivations for showcasing such developments ranged from commercial competition to claims that they provided the basis for new art forms that promoted a revitalized color consciousness amongst the audience, there is no doubt that the decade saw many examples of cross-fertilization between media. The explosion of color in conjunction with new forms of mass entertainment in the 1920s promoted a reinvigoration of older traditions such as color-organ technology, as well as inciting correspondences between diverse cultural spheres. Experts in lighting technology turned to practitioners of color music, and vice versa, as the collision between modernist experiment and a rapidly expanding classical cinema produced a fusion of cross-media activities.

A crucial emphasis of this chapter is on how the variety of experiments with color, music, and lighting can be related both to the utopian desire for a synthesis of medial forms and to discourses on educational uplift and the inculcation of a color consciousness in a mass audience. The decade saw an advance of intertwined cultural, industrial, aesthetic, and educational approaches to color, which shaped how sound, music, and mood were thought of and deployed in film, particularly with Technicolor. Both Loyd Jones’s and Natalie Kalmus’s ideas about color consciousness (in 1929 at Kodak and in 1935 at Technicolor, respectively) were clearly rooted in earlier color discourses.4 The phrase “color conscious” had appeared with increasing frequency in a range of contexts from the late nineteenth century on, in engineering manuals and art curricula, in discussions of advertising psychology, and in the popular press as the phrase entered popular parlance. People were urged to be more widely conscious of color choices in the home and garden, in personal attire, and in schools, civic buildings, and entertainment venues. In theaters, in anticipation of the color films screened in the 1920s, ambient mood lighting was often used to induce a receptive state of color consciousness in the spectator. These lighting systems exploited new technical developments, especially the ability to vary hue, tint, and illumination intensity, as a growing belief in the efficacy of influencing mood and ambience through colored lighting gathered momentum. As we shall see, there were many diverse topographical locations for color experimentation, on occasion challenging expectations about typical venues, class of patronage, and audience response. Prevailing trends toward a total intermedial experience of cinema encouraged avant-garde practices and vernacular entertainment to comingle in venues not typically associated with modernist experimentation. The accumulating rhetoric about color consciousness and its incursion into homes, theaters, streets, stores, fashion, and public buildings enabled synthetic forms of color music to traverse these various boundaries.

One such space was the combined restaurant, cinema, and dance hall at the Café Aubette in Strasbourg, a large multipurpose structure built in the late eighteenth century. It had fallen into disuse after a fire in 1870 but was redecorated in 1928 by Dutch artist and theorist Theo van Doesburg, with the assistance of German-French poet and abstract artist Hans Arp and Swiss painter and sculptor Sophie Taeuber-Arp. An interior arcade connected the various spaces: on the ground floor, a café, restaurants, shops, and bars; and upstairs, the cinema-dance hall. The spaces were not designed to be discrete: visitors walking through them experienced them as interconnected parts of a singular design. The Café Aubette’s revolutionary interior featured walls and a ceiling with mounted, largely rectangular, geometric shapes in green, red, blue, black, cream, yellow, and gray (color plate 3.1). As van Doesburg explains, the complex contours of the space allowed for its structural animation through color:

I did not have any unbroken surface at my disposal. The front wall was interrupted by the screen and the emergency exit, the rear wall by the entrance door, by the door of the small banqueting hall and by the openings for the cinematic projectors, as well as by the reflector. The left-hand wall was broken up by the windows extending almost to the ceiling, and the right-hand wall by the door to the kitchen offices. Now, since the architectural elements were based upon orthogonal relationships, this room had to accommodate itself to a diagonal arrangement of colors, to a counter-composition which, by its nature, was to resist all the tension of the architecture. Consequently, the gallery, which crosses the composition obliquely from the right-hand side, was an advantage rather than a disadvantage to the whole effect. It accentuates the rhythm of the painting.5

This was in keeping with the influential De Stijl movement’s geometric primary colors that dominated their nonrepresentational “new plastic art.” The Café Aubette’s façade was lit by neon, and the building represented a high point of ultramodern design for urban leisure, with cinema as a central activity.

Cinema spaces such as the Café Aubette were thus sites of experimentation within a culture that was going through an exciting, chromatic period of intermedial exchange. The fundamental principles behind the site’s design represented the spirit of the decade to synthesize media forms and produce total effects through tone, mood, hue, and illumination. As we shall see, this synthetic approach subsequently informed the sound era of film, when color, in combination with music, dialogue, lighting, and other elements of mise-en-scène, was conceived as an orchestrated element of a film’s complete design.

A Color-Conscious Decade

With a greater understanding of color’s synthetic uses in entertainment and in the broader public sphere, a variety of artists, designers, and architects looked to color as a means of negotiating the modern world. Colour, a magazine produced in the UK from 1914 to 1932, for example, featured a series of articles on “Colour—The Townscape Campaign.” The aim was “to extend the influence of colour towards improving the amenities of our cities,” while advocating: “There is a very close reaction between colour and the business of to-day, and the stress and strain of modern life demands every psychological aid. Congenial, artistic colour in our townscapes would add immeasurably to the feeling of well-being.”6 Multipurpose entertainment venues such as the Café Aubette epitomized this kind of expansive approach to color design in urban life.

As artificial lighting technologies developed, an awareness of color consciousness became marked across cultural, scientific, and industrial fields. Connections between hitherto disparate modes of experimentation were forged, as a number of practitioners and theorists saw color as a revelatory force. Cities increasingly converted to artificial lighting for advertising and civic displays, and moviegoers experienced a similar barrage of light and color in theaters. The increasing ubiquity of neon lighting in major cities increased the incidence of exterior electric signage used for cinemas, and the colorful experience of entering into these spaces was aimed at creating a heightened sense of anticipation for the movie presentation. The Warners’ Theatre on Broadway, New York, for example, applied a “color absorption” technique above the marquee at the entrance that manipulated overlapping and contrasting colored lights to enhance or absorb one another in alternating intervals. A sign painted with yellow and pink images of John Barrymore in Don Juan (Alan Crosland, U.S., 1926) and one of his female costars was illuminated at night by alternating red and blue-green colored lights to give the impression of animation. A report described how the effect worked:

The principle of this type of display lies in the scientific discovery that colors of equal light intensities reflected against one another produce a white, or “colorless” effect. In other words, when two reds are reflected against one another, there is a “fade out,” leaving only the blue background visible to the eye. In this manner, only certain of the postures are seen when either of the lights flashing alternately, strike the surface of the painting.7

Other displays designed to bring color into lobbies included the “Crystal Sign,” in which pieces of crystal were bonded into shapes, mounted on a background of red and purple glass, and then adjusted to a flash box. Intermittent flashes of light made the crystals appear like diamonds. Color was also added to lobby displays and posters.8 Such illuminations shared with visual music the linking of colored lighting with mood, tone, space, and rhythm.

Foyer spaces were particularly important for refocusing the spectator’s consciousness from everyday reality to “the make-believe world of the screen and screen conventions.”9 Some German architects, such as Friedrich Lipp, thought the change should be abrupt “in order that a violent, dramatic contrast may be produced”; he applied this idea in his designs for the Atrium Theatre in Berlin, which had a foyer with “bizarre overhead lighting” to create “a profusion of light to dazzle the spectator.”10 The foyer of the Atrium, opened in 1926 and demolished in the mid-1950s, was illuminated by ceiling fixtures arranged in consecutive rectangular shapes that appeared stark because they were the only form of artificial light within a generally dark ambience. By contrast, the Kammer Lichtspiele in Chemnitz, designed by Erich Basarke, displayed a more gradual approach, with the foyer featuring subtle decorative inflections and soft lighting. An intermediary approach was to have cornice lighting in foyers shifting from a suffused glow of indirect lighting in different colors to “a blaze of brilliance before the principal doors giving access to the auditorium.”11 Such examples were underpinned by theories about the specific affective and physiological influences of artificial lighting, usually connected with large corporations interested in exploiting these effects for commercial purposes. At the same time, atmospheric colored light became a central element of the debate pertaining to its aesthetic as well as distracting potentials, acting as a fascinating vector of possibility that transcended purely technical details.

A key figure in colored lighting during the 1920s was Matthew Luckiesh, who directed applied science at the Nela Park research laboratory of General Electric in the United States and became its overall director in 1924. In 1916, he wrote about how colored lights could be used for their “psycho-physiological effects,” an important scientific field of the time that derived from German research that related physical stimuli to sensations and perceptions, as discussed in chapter 1.12 These ideas challenged a purely optical understanding of color analysis as enshrined in turn-of-the-century color science. Proposing that psychological and physiological processes, in addition to the optical properties of color, were vital to color analysis resulted in a more nuanced, variable model. This highlighted the impact of different color effects and “modes of appearance,” which included those dependent on time, or even memory.13 Luckiesh’s ideas were based on a general conception of warm and cold colors (a notion popular from the nineteenth century on, and famously later adopted by Natalie Kalmus of Technicolor), the former being reds and oranges and the latter blue, with green seen as neutral. Greater or lesser saturation was a means of intensifying a mood or lessening it. As Luckiesh put it: “The lighting specialist may accomplish much of his own accord by utilizing the coldness, warmth, and neutrality of colors which may be obtained in any degree by a proper selection of hue, tint, and illumination intensity. He may study the symbolic uses of color and gradually extend these to lighting. There is no reason why we should not paint with light; in fact, this is an excellent description of an artistic lighting effect.”14 There were variations on these ideas, but in general an understanding of color consciousness was developing that depended on using color’s impact in a variety of contexts and media. Color and lighting expert Beatrice Irwin lectured to city planners in Los Angeles on restricting colors and combinations according to area. She advocated that city illuminations should be guided by “the minimum amount of red, blue and violet, the moderate use of orange and indigo, and the maximum of green and yellow and white,” and that some streets should be demarked for advertising which “might call forth new ideas in architecture and illumination.”15 As detailed below, a number of color theorists, including British advocate of color music Adrian Klein and Kodak scientist Loyd Jones, were similarly enthusiastic about the aesthetic possibilities of controlling colored illumination. This opened the door to a plethora of mobile effects that modulated hue and intensity to create artistic color designs in keeping with Luckiesh’s analogy with painting.

During the 1920s, the growing fascination with color psychology and closely related ideas about color consciousness influenced thinking around color, cinema, and the interconnected avant-garde and vernacular forms that underpinned visual music. Disparate individuals were connected through their advocacy of these ideas, albeit from different professional fields. Some were interested in improving public taste, while others used color to advertise new products and fashions. As psychologist and psychophysicist Leonard Troland—an assistant professor at Harvard who also worked for Technicolor from 1918 on—observed:

What a remarkable medium for the production of novelty we possess in color, with its infinitude of tones, saturations, shades and contrasts! It may not be the function of illuminating engineering to light our streets with green in order to inhibit robbers and gun-men, or to flood our dining rooms with red to stimulate digestion. On the other hand, to provide us with an infinite fancy of the hour, may be a real service not only for the pleasure of the instant, but indirectly for our mental and moral efficiency, as it is governed by our satisfaction in living.16

Troland’s interest in applied psychology and color reflects many of the broad interests of Harvard’s psychological laboratory, and he overlapped briefly with Hugo Münsterberg at the lab in fall 1916. As discussed in chapter 1, Münsterberg even gave Troland an inscribed copy of The Photoplay: A Psychological Study (1916). Perhaps informed by Münsterberg’s fascination with cinema, and given its growing ubiquity at the time, it is not surprising that Troland saw the medium as a primary outlet for chromatic expression. At Technicolor, he worked on all manner of color innovations, such as exploring how the process could best enhance image depth and precision: “When color is used…a new medium becomes available in terms of which the details of the picture can be rendered and color contrast can take the place to a large degree of brightness contrast. At the same time the truthfulness of the representation is greatly improved.”17 Toward this end, he worked tirelessly to perfect the company’s imbibition printing process.18 He was also involved in broader areas of public debate about color and was instrumental in helping establish new standards for colorimetry during the 1920s.

Both Luckiesh and Troland contributed to the Exhibition on the Art and Science of Color held in New York in 1931, which brought together industrialists, scientists, educators, artists, and technicians in what was described as “the first comprehensive effort yet made to indicate the use and future possibilities of color in virtually all departments of modern life and will bring to the public a better understanding of both the scientific and artistic aspects of color.”19 It is clear that advocates of color consciousness promoted it as a means of conferring cultural capital on those whose competences could be sufficiently developed about color codes.20 In this sense, Luckiesh, Troland, and others were educators with a mission to enlighten people, regardless of wealth, about color choices.

Notable chromatic experiments during the 1920s were influenced by such views. These grew out of ideas and practices that had been developing over many years through experimentation with color music. In the 1920s, artists became interested in film’s potential as a platform to “put paintings in motion.”21 As noted earlier, a variety of terms were used to describe interactions among light, color, and music, including “mobile color,” “color music,” and “visual music.” Mobile color was generally associated with projections of colored light onto moving forms, as with stage performances, and also with the ability to change the colors of shafts of projected light, giving the impression of movement and dynamism. Those interested in color music, as detailed below, typically combined music with colored light to intensify depths of emotive power, with an interest in sensorial transference and synesthesia. Direct correlations between musical notes and colors were not always sought, however, as artists experimented with the total interactions between media designed to transcend the impacts of discrete forms. Visual music was a synonymous term for exploring the fluidity and nuance associated with auditory music but in visual forms, as in abstract films, which again were not tied to convention or code.22

Experts in color research were affected by these ideas as they engaged in a broad spectrum of related enterprises. For example, even though Luckiesh is most associated with his lighting work throughout the 1920s, he also experimented with color-organ technology. He invented a “Byzantine jewel box” that was demonstrated publicly at the Exhibition of the Science and Art of Color in New York in 1931. This was described as “a constantly changing panorama of color designs projected on a screen. Beginning with ordinary geometric patterns in black and while, the designs gradually assume more and more color, rising to a climax in a series of gorgeously patterned stained glass windows.”23 Leonard Troland was similarly interested in the efficacy of experiments in color music in relation to electrical engineering, advocating that these fields should be closely connected: “The illuminating engineer should lend his assistance to this new artistic enterprise, as to the world of artistic endeavor in general.”24 At Kodak, Loyd Jones experimented with kaleidoscope forms of color music, both through the orchestration of projected light and through abstract film experiments shot on two-color Kodachrome, much of which he demonstrated at the Eastman Theatre in Rochester, New York (color plate 3.2).25 In addition, in his writings with reference to Luckiesh, Jones explicitly advocated for the development of the motion picture public’s “color consciousness” through chromatic experimentation.26 This advocacy of the benefits of color consciousness was evident in Luckiesh’s utopian claims that it would make “the world a happier place to live in.”27 The desire to link different colors with particular attributes or moods could, however, be in tension with the knowledge that it was culturally and aesthetically problematic to tie colors to specific universal meanings. Most forms of color experimentation during the 1920s negotiated this issue, with something of a consensus emerging around the desirability of color consciousness among artists and the general public.

As the concept of color consciousness became more frequently cited, particularly in the U.S. press after 1925, its applicability extended internationally across media, as exemplified in the writings of Adrian Bernard Klein. An influential British writer, filmmaker, and color theorist, Klein (who later went by Adrian Cornwell-Clyne) was also fascinated by color music. His classic text, Colour-Music: The Art of Light (1926, revised in 1930), surveyed the field and its future possibilities. He was skeptical of seeking to attribute universal effects to particular colors, preferring instead to stress the importance of context:

It is insufficient to assert that red and red-orange will be exciting. The luminosity of a hypothetical red might be less than that of a blue-green preceding it, and less than, say, a light-violet succeeding it. In which case, the effect of the red might be momentarily restful; an effect due to its luminosity context. The attention will be held, and the highest exciting influence, physiological and psychological, exerted by the bright blue-green following a sequence of very “hot” colours, such as low oranges, crimson, and salmon. The effect will be in relation to the whole, and dependent upon the logic of the entire “movement.”28

The freeing-up of color and image to motion and mutability was an important conceptual move that permitted greater experimental variability: color became dynamic. This produced debates between enthusiasts from various backgrounds. For example, British lighting engineer Fred Bentham, who in the 1930s installed a color-music light console at the King Street Strand Electric Theatre, London, read and indeed critiqued some of the positions outlined in Klein’s book, particularly those parts that sought visual equivalents to musical notes.29 No single constituency, class, economic, or creative group owned color or its experimental applications.

Color music was experimented with widely in 1920s in ways frequently overlapping with cinema. For instance, prevalent ideas about color consciousness influenced not only color cinema but also a new phase of color-organ technology. Relatedly, the emergence of the avant-garde and notions of Absolute Film in Germany dynamized color music’s relation to popular forms of screen entertainment. Drawing further on Bourdieu’s analysis of the field of cultural production, these examples illustrate that the 1920s was a classic period of “continued rupture.” As Bourdieu explains, such ruptures occur when “a new art of inventing is invented, in which a new generative grammar of forms is engendered, out of joint with the aesthetic traditions of a time or an environment.”30 As we have seen, profound changes in the synthetic-dye industry, shifts in commercial production, and rapidly expanding film industries across Europe and the United States enabled a dynamic range of artistic possibilities, all jostling for attention within the broad field of cultural production. Although cinema was becoming more institutionalized, its codes were not fixed; in Bourdieu’s terms, a stable habitus (the acquired norms that guide behavior) for aesthetic practice was not yet in place. This created a space for engagement between practitioners who wanted to develop new codes (significantly, many of the experiments discussed below were pitched at developing new art forms) while drawing on technical and ideological trends encountered outside of their usual habitus, such as advertising. In part, this offers an explanation for why the decade is typified in many ways by the lure of standardization. Those interested in color consciousness were reaching toward the institution of new codes. Although Bourdieu argues that innovative work can only be fully appreciated as such when one is cognizant of prevailing or established codes that appear to be challenged, in the 1920s conventions were far from established or stable. The themes discussed in the following sections demonstrate how continued rupture was conducive to works that both revitalized older traditions of color music and claimed new artistic approaches, as well as new spaces and material locations. While the lure of standardization promised to quell the anarchy of continued rupture, this very condition promoted—and necessitated—new alliances.

Color-Film-Music

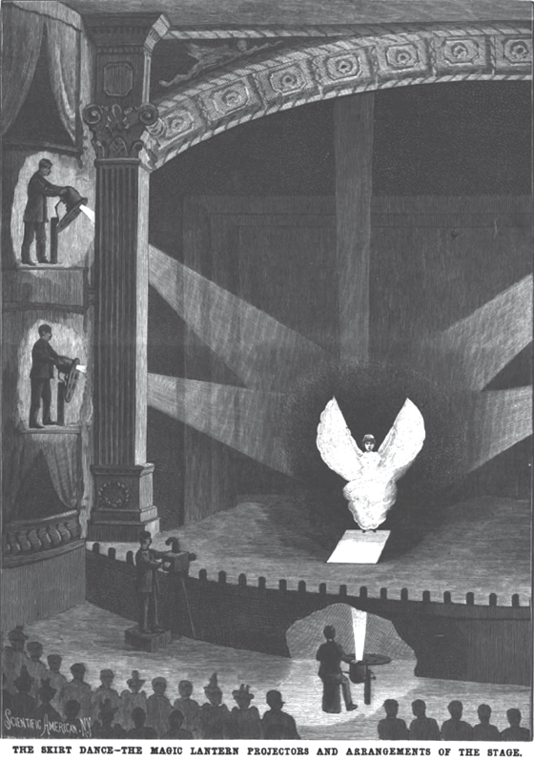

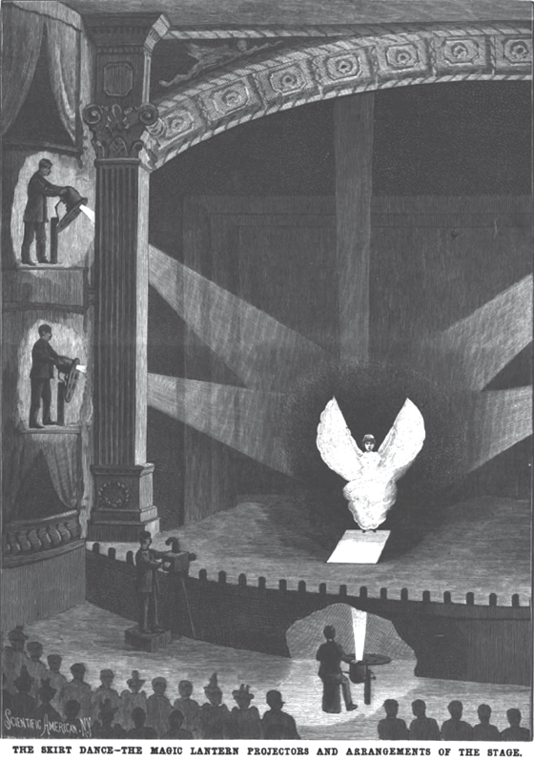

To understand the surge in experiments with color music in and around film in the 1920s, it is useful to examine the practice’s aesthetic roots. Associations between color and music have a long history, dating back to Plato, Pythagoras, Aristotle, and Newton—philosophers intrigued by affinities between the two. Various technical devices were developed to demonstrate correspondences between color and music, such as Alexander Wallace Rimington’s color organ, introduced in the late nineteenth century.31 This consisted of two keyboards, one to play music and the other to play colors, aided by electricity that illuminated arc lamps that radiated through colored filters. The performer decided which colors matched the musical notes best rather than adhering to a strict correlation between music and colors, although of course many working in the tradition were keen to create links based on color psychology. A similar device called the Chromola, apparently based in part on Rimington’s innovations, accompanied Russian composer Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus: A Poem of Fire in 1915 at its New York premiere, and the colors were indicated on Scriabin’s score.32 The development of artificial lighting, particularly incandescent lamps, was profoundly important in advancing research into color, often originating in the scientific field but with broader applicability in the arts. This gave new impetus to those who dreamed of uniting art forms, with color providing the essential connecting force. Loïe Fuller, a Chicago-born skirt or “serpentine” dancer who became famous at the Folies Bergère in Paris, experimented with lighting effects that proved influential on those later interested in mobile color. Klein notes: “She began by using vertical shafts of light projected upwards from beneath the stage. In these narrow cones of light the dancers whirled, twisting shreds of gauzy fabric, whilst the beam was rapidly altered in colour; and the effect was like that of a figure enshrouded in an iridescent column of flame.”33 The skirt dance was incorporated into early hand-colored films, such as Edison’s various films with Annabelle Whitford and the Lumières’ serpentine dance films (most early film companies distributed some version of the serpentine dance).34

These earlier trends entered into a new phase of experimentation in the 1920s as incandescent lighting technologies developed and awareness of color consciousness became marked across several fields. The general shift during the decade toward mass spectatorship also had an impact on the heterogeneity of exhibition venues and the intermedial nature of public presentation. The emphasis on dynamic color through variable illumination in particular attracted those interested in exploring relationships between music and color, often departing from the idea that exact or fixed correspondences could be achieved. Practitioners in the 1920s were more interested in experimenting with mood and psychology and in creating empathetic correspondences between color and music for public performances in a range of different venues. These initiatives were less embedded within scientific discourse, nor did they seek a formula that linked colors to specific musical notes. Mobile color was premised instead on variable effects on the senses as a pleasurable form of synesthesia, referring not exactly to the medical condition in which the sensory nerves literally becoming mixed (for example, hearing colors or tasting sounds) but to a more generalized sense in which mobile colors were thought to induce a range of resonant sensations and stimuli that people responded to in diverse ways. As the following examples demonstrate, a number of mixed-media presentations were designed to transport spectators into other realms—sensorial, color-conscious, mystical, and multidimensional. In their exploration of new codes and mobilization of diverse sensual experiences, these experiments appealed to a range of viewers with different aesthetic competencies, including a growing familiarity with the norms of classical cinema.

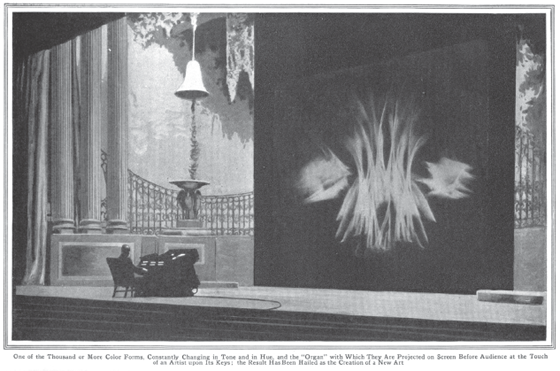

Danish-born singer Thomas Wilfred was interested in movement, color, and form in a series of experiments based on the Clavilux, a color organ he developed and first introduced in 1922 in New York for “lumia” (art created by light) performances that were capable of showing a “continual metamorphoses of color.”35 In his practice, “the visual rhythm of the moving forms of his lumia dictated how they were thematically characterized more than the selection of colors used.”36 Rather than assuming that a direct correlation between colors and meaning could be produced or understood, this left room for metamorphoses—“music for the eye,” as he described it. The description is apt because, much as music’s aural impact can transpose listeners to imaginative realms, Wilfred’s lumia combined motion and color to produce a variety of perceptual sensations that did not depend on the presence of music to achieve their complete, almost mystical impact, so that “viewers could commune with the hidden spiritual force surrounding and inside objects in the world.”37 Wilfred described lumia as an aesthetic concept, “an independent art-medium through the silent visual treatment of form, color and motion in dark space with the object of conveying an aesthetic experience to a spectator.” The physical means through which this was achieved was “the composition, recording and performance of a silent visual sequence in form, color and motion, projected on a flat white screen by means of a light-generating instrument controlled from a keyboard.”38 Music did not accompany the demonstrations, but was included only for the orchestra’s opening program. George Vail described the experience:

By almost imperceptible changes the hitherto invisible screen becomes a stage for the play of vague, groping, half-defined shapes. Two gossamer-like curtains appear, their silken folds agitated by a breeze whose breath we do not feel. They are drawn to the sides of the frame leaving a central space free for the entrance of the theme. The latter emerges from below—some simple adaptation of a motif drawn from nature, but lacking the stiffness of most conventionalized forms. It proceeds upward, slowly, majestically, as though floating in a transparent fluid, and pauses at the center of the picture. Here the transformations begin.39

The same viewer went on to describe a series of “subtle metamorphoses which at times suggest the unfolding of a symphony, a sonata, a series of variations […]. Most of Mr. Wilfred’s color recitals consist of four distinct but related compositions, differing in rhythm, treatment, and thematic material, and separated by brief intervals of darkness.”40 The images were suggestive of shapes and forms that were constantly in flux. Responding to them did not rely on spectators’ deploying acquired cultural competences, thus extending the potential reach of Wilfred’s performances.

The Clavilux was presented in a number of venues in downtown New York in 1922 and also on Broadway at the Rivoli Theatre. The entertainment was described in a report that conveys the effect of the multiple mutations of form, color, and light created by Wilfred’s invention:

Projected upon the regular screen, which was suffused with a mellow shade of lavender, two white columns of light arose. They were window-shaped at the top, and had a green tapering base. As these forms neared the top of the screen they gradually faded, and as the background changed to a lovely, delicate shade of green, there arose right in the centre of the screen a cluster of crimson buds. These were replaced by a revolving sheaf of half a dozen white columns which held the centre of the screen while multihued and variformed beams of light played on the sides.41

Other recorded demonstrations included one at Vassar College in April 1923, when Wilfred also gave a lecture on his lumia experiments over the years and spoke of his hopes for color schools and colleges, “leading to an immense theater for color organ recitals.”42

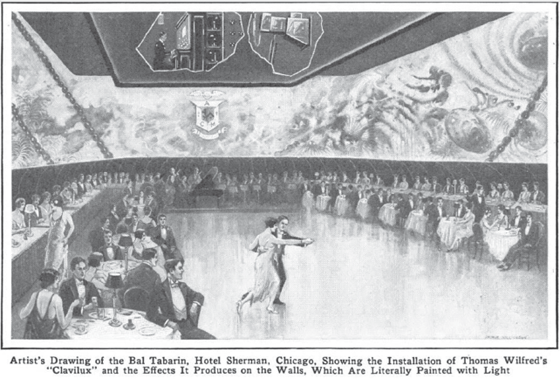

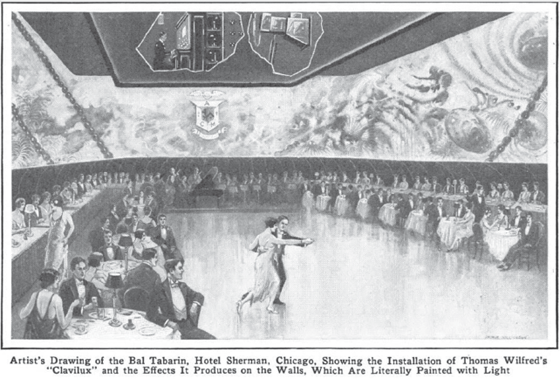

Wilfred realized this last ambition when he coordinated lighting in the Bal Tabarin Room, a dance-band venue, in the Sherman Hotel, Chicago, with the effect of “making a display that holds the patrons spell-bound throughout the evening.”43 This practical application of the Clavilux transformed the Bal Tabarin’s blank walls into decorated surfaces. As noted in a contemporary report, light projections from the ceiling created effects such as the appearance of Grecian pillars with “changing colors against what appears to be a sky of infinite depth. A sea opens up behind the columns, ships loom out of the dim horizon, then disappear. The entire scene dissolves and gives place to a performance of slowly whirling light masses that suggest the nebulae of the heavens.”44 The electrical display was described as “a sort of mechanical séance” controlled from a projection room and operated by an electrical engineer “playing” at a light keyboard.45 In addition to installations like the one at the Bal Tabarin Room, Wilfred also envisioned smaller versions, such as the Clavilux Junior series from 1930 that was meant for home viewing, and also much larger, unrealized projections from the top of skyscrapers, for which he painted plans in 1928 (color plates 3.3 and 3.4). The aim of all of his mobile-light performances was to produce in the spectator a state of transcendence, of four-dimensional space: “His abstractions served as gateways of sorts, perceptual phenomena that began in one world, but launched spectators into another.”46 Wilfred’s color-music abstractions were associated with artistic explorations of the “fourth dimension” of space beyond immediate perception that influenced contemporaries in the New York art world, particularly Claude Bragdon (discussed below).47 The response to these demonstrations was positive, as reported by Vail: “After witnessing a performance on the Clavilux, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that here we may have a new art form—that of mobile color—as pure and unconditioned, as limitless in its possibilities, as the medium of Bach and Beethoven.”48 The analogy with music is particularly interesting because the proposition—based on a general notion of synesthesia—is that mobile color can evoke similar sensations without music actually being present.

Mary Elizabeth Hallock Greenewalt papers [Coll. 867], courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

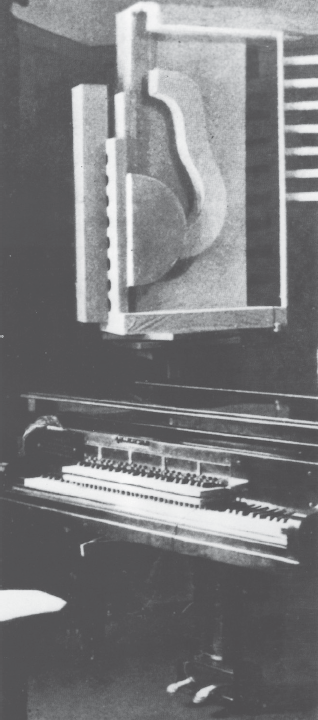

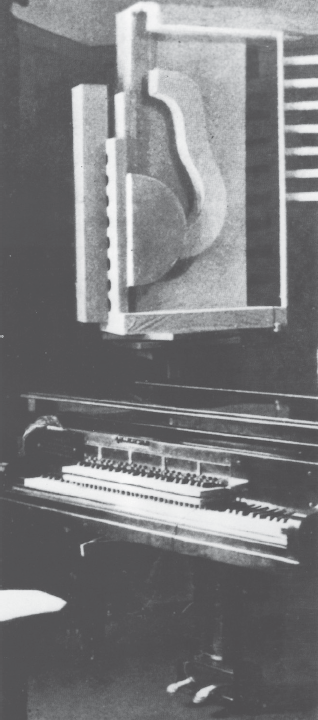

In contrast, another proponent, Mary Hallock Greenewalt, saw light displays as a means of enhancing musical appreciation and understanding and, in so doing, producing a new art form. Greenewalt, a Syria-born Philadelphia pianist, invented and patented color organs designed to project a sequence of colored-light projections to go with specific musical programs.49 Her first experiments date from 1905, but she is best known for inventing a keyboard in 1919 called the “Sarabet” (named after her mother Sarah Tabet) that operated a light show alongside a piano.50 Claiming her patents heralded a new art form, Greenewalt persuaded General Electric to manufacture a color console, on which she gave public performances. She invented a rheostat to create modulated fade-ins and fade-outs of light to enhance the ambience of a concert performance, particularly of Chopin and Debussy (color plate 3.5). She thought performers should decide on the relationship between colors, musical notes, and chords as they found appropriate to convey the mood of a particular piece. This disregard for the notion of a static code around music and color broadened the potential reach of her work—something she was clearly interested in doing, in view of the venues where the Sarabet was demonstrated. Besides music concerts, Greenewalt’s color organs were installed in cinemas, such as the Strand Theatre, New York, and dimmers were used to create color effects to support musical performances.51 She was in frequent dispute with those whom she considered guilty of infringing her patents, as light shows were introduced in cinema chains in Philadelphia, New York, and Washington.52 Correspondence with the Paramount Famous Lasky Corporation regarding this issue, for example, demonstrates how dimmers were adapted “to afford illumination of different colors, to smoothly and gradually vary the intensity of the light and to merge one color to another. The operator uses a cue sheet which he follows to give the proper lighting effects in timed relationship with the music. These lighting effects involve variations and graduations in light intensity, change and merging of colors, etc., all in sympathy with the music.”53 Although there was no lawsuit against Paramount Famous Lasky, Greenewalt’s frequent recourse to defending her patents attests to incidents of similarly conceived presentations in a number of public venues.54 It also demonstrates the disadvantages of new art forms in the making. Their very openness to creative agency and spectator response left them relatively unprotected by the strictures of robust patent descriptors required to distinguish them clearly from more general lighting effects.

As with Thomas Wilfred, there was a utopian, almost messianic aim behind Hallock Greenewalt’s experiments and her claims of heightened emotional sensation. She referred to mobile color as a “sixth art,” which she termed “Nourathar” (a combination of the Arabic words nour and athar, forming “the essence of light”). She claimed this new art went beyond painting, poetry, music, architecture, and sculpture by forming a sympathetic union of the arts appealing to “the emotions through color with the same delicacy and keenness of sensation that music makes its appeal through sound.”55 The use of dimmers to convey color variation was key to her idea of augmenting emotion in this way, as a contemporary report of demonstrations in New York described: “Mrs. Hallock Greenewalt’s experiments have already resulted in a production of 267 color tints by a 1,500-Watt light.”56 She also experimented with hand painting rolls of film that most likely performed the function of scores. Bruce Elder notes: “They would not have been visible to anyone but the performer—and even the performer would only have seen them as narrow strips passing over an illuminating bar. Their roll film function was to mark time and to indicate something about the mood of the piece.”57 The markings appear to have been similar to those more commonly associated with artists such as Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling.

A number of other experiments with color music were notable but not commercially exploited. In the United States, Claude Bragdon was an architect, theater designer, and theorist and practitioner of the fourth dimension. He expressed this in several ways, including drafting axonometric technical drawings and, less concretely, through his interest in Theosophy, a metaphysic movement inspired by Eastern and Western esotericism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and by Spiritualism. Bragdon was involved in a “Festival of Song and Light” held in Central Park, New York, in 1916, which featured multicolored lanterns and screens “designed according to the principles of four-dimensional projective ornament.”58 The following year, these were carried beside the lake and put on boats to add “a dynamic element of motion.”59 Bragdon was a member of the Promethians, an artists’ society devoted to exploring abstract patterns of light that he cofounded with Thomas Wilfred and the painter Van Dearing Perrine. After internal differences, the Promethians split up, but Bragdon made several solo attempts to build instruments for the purpose of seeing how colors influenced spectators’ emotions.60 The Luxorgan, first built in 1917 and subsequently developed in the 1920s, featured a screen illuminated from behind by electric lightbulbs that were controlled by switches on a keyboard. Massey explains: “Projective ornament patterns separated colors from one another…and each key corresponded to a bulb behind the projective ornament screen, so that when Bragdon played a musical composition, its chromatic analogue lit up within the ornamental design.”61 Building on these experiments, Bragdon believed that animated film was the perfect medium with which to test ideas about “the symbolical significance and characteristic ‘mood’ of each of the spectrum hues at different degrees of intensity.”62 He aimed to produce film animations of color-music compositions in which colors “should meet, wax and wane, and undergo transformations not unlike those retinal images one sees with the eyes closed. Superimposed upon this changing, rhythmically pulsating color-background, like an air upon its accompaniment, would next appear forms suggesting the crystalline and the floral, but imitative of nothing, developing, moving, mingling, expanding, and contracting in synchronization with the music, and in harmony with its mood.”63 Bragdon failed to interest producers in an idea for dramatizing an episode in Beethoven’s life that caused him to compose “The Moonlight Sonata,” followed by a related color-music interlude that exemplified Bragdon’s attempt to fuse dramatic action, choreography, music, mise-en-scène, music, light, and mobility “in such a way as to induce emotional reactions more powerful than any of these could compass separately.”64 In 1922, however, Prizmacolor filmed the same creative episode in Beethoven’s life for one of its color-music demonstration films. The advertisement boasted: “With the film can be secured a synchronized music ‘key’ for an orchestra or single piano accompaniment.”65 Even if such attempts were ultimately unsuccessful, they demonstrate how, in their quest for discovering new methods of synthesis between art forms, color-music artists sought to make strategic connections with commercial media by choosing popular classical pieces. The transition from Bragdon’s work to Prizma’s aspirations for color music demonstrates the evident fluidity between experimental practices and broader commercial market forces. Even if an experimental approach was limited in its immediate exposure, its capacity to resurface via another route is testament to how the “continued rupture” within cultural production during the 1920s resulted in diverse temporal, thematic, and artistic connections.

Designing an instrument could often lead to new discoveries in different phases of its life. In Czechoslovakia, for example, light-kinetic artist Zdenĕk Pešánek made three versions of his Spectrophone between 1924 and 1930. The first experiments involved a color piano that connected a light keyboard to a four-octave music keyboard; a three-color (red, green, blue) register was developed so that a color lit up when a key was played. He demonstrated his instrument in Prague in 1928 using compositions by Scriabin, but in keeping with the move away from this approach, the instrument was criticized for crudely combining color and music as a common scale. This led to refinements whereby color harmonies matched melodies, and vice versa. A final version of Pešánek’s instrument was presented in 1930 at the Second Congress for Color-Tone Research in Hamburg, accompanying Wagner’s “Siegfried Idyll.” In spite of enthusiastic reviews, Pešánek could not obtain manufacturing contracts for his instrument. As Adrian Klein noted about color music more generally, it was often the case that the complexity of instruments deterred commercial sponsors. He argued that practitioners should take inspiration from the potential of spectacular urban civic displays of light and color to prepare the public for color music and to involve themselves in that enterprise.66 It is no surprise, therefore, that Pešánek went on to create the world’s first kinetic public sculpture in Prague, which operated from 1930 to 1937. With interests in lighting public spaces and street advertisements, Pešánek is another example of a practitioner whose activities were not confined to a single field. His work highlights the acute interest of the 1920s in exploiting forms that fused media with new knowledge about color’s diversity, gradations, and multiple hues, informing inquiries that looked afresh at long-held ambitions to create instruments that related color to music. Beyond color-organ technology, this was also evident in broader avant-garde interests in combining color, light, and music, so much so that the boundaries between them became increasingly porous as the decade progressed.

Absolute Art and the European Avant-Garde

One of the prime examples of color music through film in an avant-garde context is Walter Ruttmann’s Lichtspiele Opus No. 1 (1921, color plate 3.6), an abstract film that, as William Moritz explains, was prepared “with single-framed painting on glass and animated cutouts. The film was colored by three methods—toning, hand-tinting, and tinting of whole strips—so there was no single negative, and each print had to be assembled scene by scene after the complex coloring had been done.”67 The music—intended to go with the film—was composed by Max Butting, and Ruttmann played the cello in the string quartet that performed live with each screening at several German cities in the spring of 1921. To be sure of the exact correspondence between film, color, and music, Ruttmann drew color images on the musical score so all could be synchronized exactly: “Ruttmann limited the imagery to a confrontation between hard-edged geometric shapes and softer pliant forms, and allowed the colors not only to characterize certain figures, but also to establish mood.”68 Michael Cowan has pointed out that, far from being an isolated aesthetic practice, much of German Absolute Film in the 1920s, particularly Ruttmann’s work, was tightly integrated with discourses around advertising psychology, demonstrating an interrelation of high modernism with the systems of mass production in ways that resonate with Hansen’s concept of vernacular modernism.69 Contemporary experiments in memory and perception theory used mathematical shapes that resonate with those in Ruttmann’s films. Playing with color contrasts for maximum impact in the same way, these correspondences encouraged avant-garde artists to make advertising films in Germany. Contemporary critic Rudolf Kurtz noted in 1926: “The strong appeal of Ruttmann’s films lies in the psychological stimuli which make them continually effective. His compositions are dramatic, employing as actors geometric shapes which reverberate with a wealth of organic echoes […] the viewer is pulled into a whirlwind of motion and integrated into an atmospheric blend of colours that never leave him for an instant.”70 Ruttmann’s awareness of the affective power of color can also be tracked through similarities between his animated advertising films and the recommendations of contemporary advertising theorist Theodor König that color contrasts of green and red or yellow and blue created maximum impact on consumers.71

Theorized in relation to the notion of Absolute Music, Absolute Film refers to the film movement Ruttmann was part of with Hans Richter, Viking Eggeling, and Oskar Fischinger—a practice of nonrepresentational “pure” cinema, divorced from the distractions of conventional narrative, that aimed to engage the spectator “more as an embodied object of psycho-physical testing than as a hermeneutic interpreter.”72 According to William Moritz, central to the movement was the idea that “the most unique thing that cinema could do is present a visual spectacle comparable to auditory music, with fluid, dynamic imagery rhythmically paced by editing, dissolving, superimposition, segmented screen, contrasts of positive and negative, color ambiance and other cinematic devices.”73 Visual rhythm was key to these works, so that scripts were like musical scores that drew attention to film’s basic mobile elements of light, the material frame, and time.74 Although there had been attempts to create films according to these principles before the First World War, Ruttmann’s Lichtspiele Opus 1 (1921) was the first Absolute Film that was available for commercial distribution.

Ruttmann’s experiments influenced others, including German filmmaker Oskar Fischinger and Hungarian composer Alexander László, the latter known for Farblichtmusik performances using his color organ piano and projected colored lights in 1925–1927. Fischinger and László collaborated in 1926, presenting Farblichtmusik in Munch and elsewhere. Subsequently, between May and October 1926, László gave approximately 1,200 performances to more than forty thousand people at the GeSoLei trade fair and exhibition of Health (Ge), Social Welfare (So), and Body Culture (Lei) held in Düsseldorf.75 Ruttmann’s film Der Aufsteig (The Ascent, 1926), shown at the same event, advertised the festival’s broader educational aim of promoting postwar regeneration of the Rhineland and of Weimar Germany. Ruttmann’s abstract color film shows an “everyman” figure at first seen as thin, ravaged by the war, and attacked by a green snake. Attending the GeSoLei fair signals a return of his vitality, as he performs gymnastics and ascends stairs toward a red circle symbolizing new energy. Color music and experimental forms were thus utilized for a broader public purpose, attracting new audiences. Fischinger went on to devise his own independent multiple 35mm projector performances, which included color filters and slides. He later adopted the term Raumlichtkunst (space light art) for these events, which he described as “an intoxication by light from a thousand sources” (color plate 3.7).76

The Absolute Film pioneers’ work came together at a historic screening in Berlin in 1925 (see chapter 4). The program included a live performance by Bauhaus artist Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack of Dreiteilige Farbensonantine (Three Color Sonatinas), using a special color-music apparatus; Eggeling’s Symphonie Diagonale (Germany, 1924); Ruttmann’s Opus 2, 3, and 4 (Germany, 1923, 1924, 1925); René Clair’s Entr’acte (France, 1924); Dudley Murphy and Fernand Leger’s Ballet mécanique (France, 1924); and Hans Film ist Rhythmus (Germany, ca. 1925). This influential program, which later screened at the Bauhaus in 1926, has tended to locate avant-garde moving-image experimentation with color in the 1920s primarily in Germany, although its influence spread far beyond.77

At the Bauhaus, Kurt Schwerdtfeger’s Reflektorische Farbenspiele experiments of color-light play and Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack’s Farbenlichtspiele aimed to appeal to a broad audience in an attempt to democratize art. In 1922, they collaborated for a brief period before developing their individual color-light projections. These German demonstrations, developed alongside a color seminar at the Bauhaus initiated by Hirschfeld-Mack, brought abstract forms and colors into movement on a screen through the superimposition of transparent colored panels in front of floodlights.78 The intention was to promote emotional engagement with projected, nonrepresentational moving colored shapes as a means of broadening the appeal of abstract painting.79 A sense of visual dynamism was created through “the two-dimensional movements of color-form and the three-dimensional depth created by the overlapping color-forms. The constant vertical and horizontal and forward and backward movements of the color-forms cause the Farbenlichtspiel image to shift unceasingly.”80 Hirschfeld-Mack was particularly interested in perfecting the device and making it commercially available, whereas Schwerdtfeger’s concerns were with exploring colored moving shapes as artworks with educational potential.81 Their works were performed on several occasions, including at the 1925 Absolute Art screenings, as mentioned, and at the Farbe-Ton-Forschung (Congress for Color Tone Research) hosted by Georg Anschütz in Hamburg in 1927.82 Such gesturing toward democratization and education is indicative of the ambition evident in the 1920s to extend experimental color devices, forms, and practices to people not conventionally associated with aesthete culture. The decade of continued rupture thus produced a plethora of cross-media practices that challenged categorizations of color in terms of both its form and its address.

Vernacular Forms

It is clear from an examination of a variety of examples and sources that experimentation with light, color, and music was evident in several forms and with different emphases from those associated with the avant-garde. There were significant attempts to inculcate some of the aspirations of color music through film in the broader realm of vernacular entertainment. All were premised on the idea that appreciation of color in particular could be cultivated, to enhance cultural capital and add to the continuing artistry of cinema. The term “color consciousness” again becomes highly relevant, cutting across aesthete and popular forms.

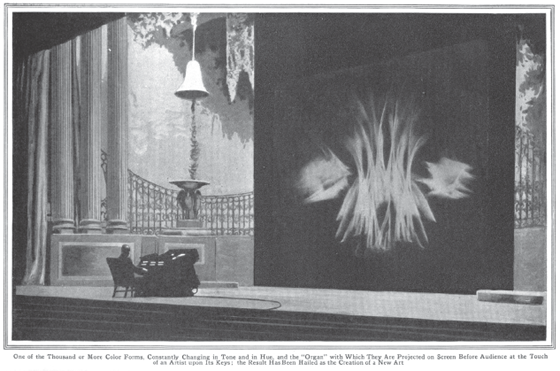

Loyd Jones, an American scientist who worked for Eastman Kodak (discussed briefly in chapter 1) was convinced that color enhanced screen drama through its ability to appeal to and develop an audience’s color consciousness: “If there is in the human mind, or, more specifically, in the collective mind of the motion picture public, a color consciousness, even though it be at present latent or but slightly developed, is it not worth considerable effort in thought and experimentation to develop a technique such that color can be applied to the screen in such a way as to enhance the emotional and dramatic values of the motion picture of the future?”83 Jones experimented with mobile color projections at the Eastman Theatre in Rochester, New York, where various devices were developed to show a range of changing color hues, using pattern and design plates to project forms and other effects “as a means of artistic or emotional expression entirely independent of the art of music.”84 Based on the kaleidoscope, Jones invented a cinematic lens attachment for film projectors that was patented in 1924. The resulting effects could be projected on their own or recorded on color film stock to create abstract effects, as in Mobile Color, a short film shown regularly at the Eastman Theatre in the mid-1920s, accompanied by Debussy’s Arabesque (color plate 3.2).85 Although Jones was interested in how his device might be used to underscore emotional emphases in narrative films, there are no known applications of its being used in this way.86 His views on linking color with mood were reaffirmed at the end of the 1920s when he helped to develop Sonochrome, a pretinted film stock designed for films with soundtracks (see chapters 1 and 4).

The effectiveness of color music through film therefore depended not only on practitioners interested in experimenting but also on audiences being receptive to color as an essential part of the synthetic triad. The general enthusiasm for the idea that colors related to moods and emotions was evident in avant-garde practice as well as in more popular forms, in narrative films and broadly within commodity production marketing. As notions of hue and saturation led to colors’ being seen as multifarious, complex, and subject to great variation, it was possible to apply this in a wide range of contexts that promoted technical ingenuity and creativity. At the same time, the desire to standardize color was also present as industrial and commercial applications involved branding exercises that sought to capitalize on the color revolution. While tinting and toning were the most common forms of color in popular film entertainment, the interest in how a film could be supported by appropriate music and colored lighting extended to the entire experience of going to the cinema. The mood established in a cinema theater was a key part of this process.

Beyond the Screen

Cinema architect Ben Schlanger expressed his views on the use of color in 1931:

In the motion picture theater, color is employed to create a mood in the patron. It is my feeling that color in the film should be used for the same purpose—to create a mood for the particular action on the screen rather than to show detail of color of the objects depicted. It is a delicate question as to what color will arouse the proper mood in the person viewing the film.

Color will be tremendously important in the future for the reason that theaters will become simpler in design and will not rely upon colored decorations on the walls, ceilings, domes, etc., for creating mood, as is at present done. The color on the screen might be utilized to take the place of colored decorations, the color being chosen so as to arouse the particular mood desired, and its reflection onto the simple decorations of the theater would provide the color projection which has before been suggested for the interior walls of a theater.87

The members of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers were discussing how colored decorations in motion picture theaters were integral to establishing an ambient, chromatic mood for film presentations. Cinema exhibition culture of the 1920s was imbued with a desire to move spectators with a totalized, ambient chromatic experience that began as soon as they entered the theater. In addition to avant-garde films, color organs, and theoretical writings about the melding of media into new forms, theaters and cinemas were locations for colored light displays that were often intended to interact with or complement film screenings. In both North America and Europe, cinemas sought to incorporate new lighting devices to accompany film presentations. As the fascination with color spread, a rhetoric of color consciousness recurred. According to one contemporary survey of “the architecture of pleasure” in Europe and the United States, modernism was the perfect style to ensure that “we think less of splendor and more of light, air and color.”88 From the late nineteenth century, electrification transformed cities with electric trolleys, street lighting, and the rapid growth of amusement parks, particularly in the United States.89 The key developments in the 1920s, however, were the spread of neon lighting displays and the greater incursion of electricity into homes. For some time electrical advertising signs had assaulted spectators with awe and wonder at “the technological sublime,” as Kirsten Moana Thompson has described, but “a major transformation of the urban skyline was the emergence of neon as a new colour technology.”90

Following the rare-gas experiments in 1898 pioneered in the UK by William Ramsay and Morris Travers, neon colors were first developed for commercial advertisement in France by electrical engineer Georges Claude to promote the “Palais Coiffeur,” a Parisian barber shop, in 1912 and then exported to the United States. Neon signs began to appear in New York in the early 1920s, but it was not until 1925 that the iconic red- and blue-rimmed Packard sign in Los Angeles, often taken to be the first neon sign in the United States, was publicly erected.91 The popularity of neon spread to other major cities and reached its height in the 1930s.92 Exhibitors in the UK were advised to install neon signs because “scintillating signs are most effective in announcing current or forthcoming features.”93 The visual clarity of neon—with its brilliant reds, greens, purples, yellows, orange, and blues—was perfect for advertising. Besides being more easily seen in daylight, darkness, and poor weather conditions than incandescent lighting, neon signage had the advantage of requiring less electrical current. As Thompson has noted, the color aesthetics of electrical advertising related strongly to trends in the graphic arts, including posters “in which the eye was arrested in surprise at a pleasing or startling colour design.”94

Advertising World, a contemporary British journal, published articles on numerous aspects of color design for advertisements, including input from American graphic artist E. McKnight Kauffer, who worked mainly in the UK and designed intertitles for Hitchcock’s The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1926). He commented that color is “an interesting problem with surprises” in terms of strategic application of bold colors, or red in addition to black and white, as a standard for basic poster design.95 Awareness of and contributions to debates surrounding the psychological impact of color are evident in a special issue of the journal’s “Outdoor Publicity Supplement,” which advocated studying color’s “emotional values” along with science because of the “dual power of color to express physically, by its hue, tone and contrast, some fact about the product, and at the same moment by the same colour to impress the observer physically with its importance.”96 Similar attractions are evidenced by the plethora of neon signs, with their clear, graphically designed colored lines of text, figures, and objects creating spectacular optical effects to stimulate spectators. These developments expanded the notion of cinematic experience to encompass the full barrage of chromatic visual effects emanating from posters, animated advertisements, pulsating neon signs, shop window displays, and movie theater interiors and exteriors.

There were also strong associations in France between advertising theory, visual display, color, and creative experimentation. American theories about the psychology of advertising were popularized by Pierre Clerget, a professor at the Ecole Supérieure de Commerce in Lyon, focusing on the impact of attention-arresting sensations to force passersby glancing at an advertisement to stop.97 Color was central to this impact, even if used sparingly, as in many poster designs, to create stark but striking contrasts with forms outlined in black and white. This compositional approach was evident in both Europe and the United States; spectators were addressed by using “cinematic techniques to achieve motor and sensory stimulation” with the aim of achieving a kinetic perception that was “in line with the spectatorship shaped by advertising theory.”98 Indeed, the visual cultures associated with modernity, from advertising posters reused in experimental films to Léon Gimpel’s autochrome plates that captured the vibrant colors of neon illuminations in Paris, provided artists with iconic commercial imagery to draw upon.

German theaters and Kinos were considered very advanced, leading in modernist design, electric signage, decoration, and internal lighting schemes. The “gaze-capturing” façades of Berlin movie theaters decorated by Rudi Feld, for example, “brought an unabashed celebration of the cinematic viewing experience out onto the street.”99 Feld’s designs were arresting celebrations of light, “an intoxication of color” that often connected thematically with the films being shown.100 To Siegfried Kracauer, however, city dwellers were aesthetically numbed by the “cult of distraction” as the “glassy columns of light, as tall as houses, the bright overlit surfaces of cinema posters, a confusion of gleaming neon tubes behind mirror panes” in Berlin represented an “uninhibited spark, which does not only serve advertising, but is also self-serving.”101 Struck with the irony that the Kaiser Wilhelm church in Berlin was bathed in light from neon advertisements “in a glow that replaces any divine type of spark or illumination,” Kracauer was not impressed by the “cathedrals” of mass entertainment.102 He further described the Gesamtkunstwerk of spectacles in Berlin’s movie palaces:

This total artwork of effects assaults all the senses using every possible means. Spotlights shower their beams into the auditorium, sprinkling across festive drapes or rippling through colorful, organic-looking glass fixtures. The orchestra asserts itself as an independent power, its acoustic production buttressed by the responsory of the lighting. Every motion is accorded its own acoustic expression and its color value in the spectrum—a visual and acoustic kaleidoscope that provides the setting for the physical activity on stage: pantomime and ballet. Until finally the white surface descends and the events of the three-dimensional stage blend imperceptibly into two-dimensional illusions.103

For Kracauer these “total artwork” spaces were not expressions of higher art forms but rather “picture-palaces of distraction,” with their overwhelming appeal to the senses acting as a palliative to the spiritual emptiness of urban living.104

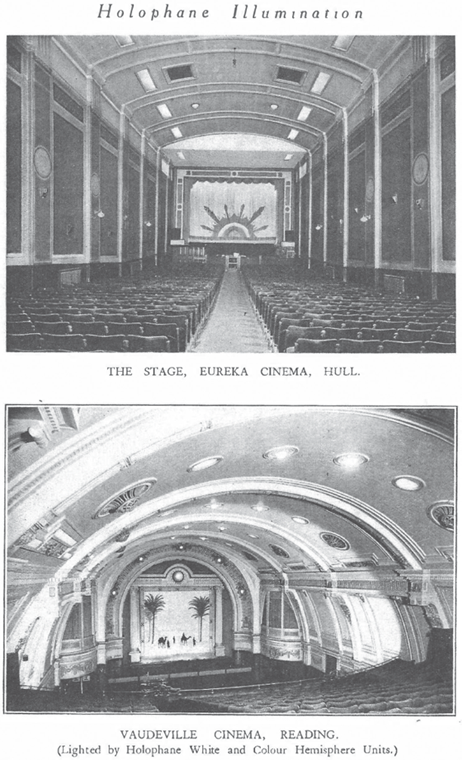

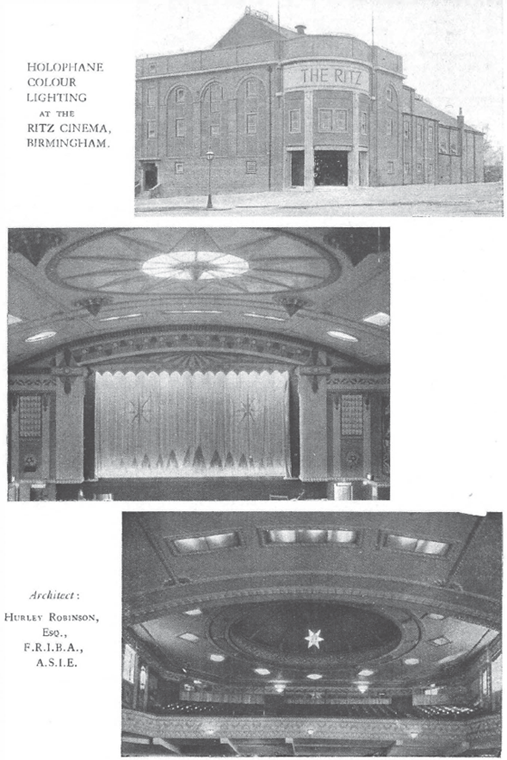

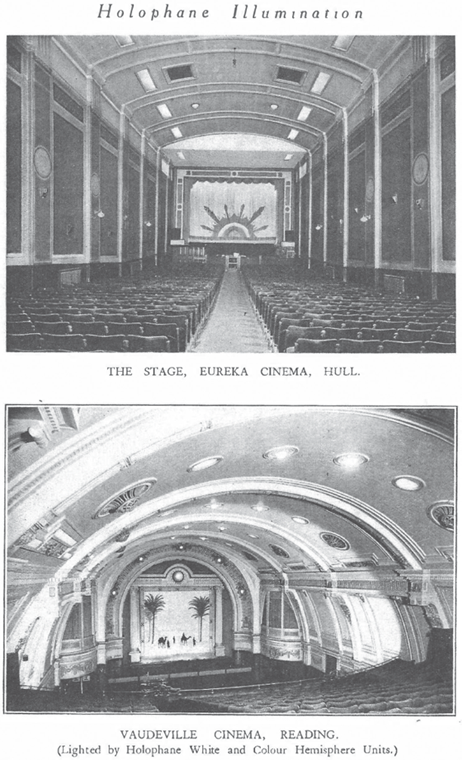

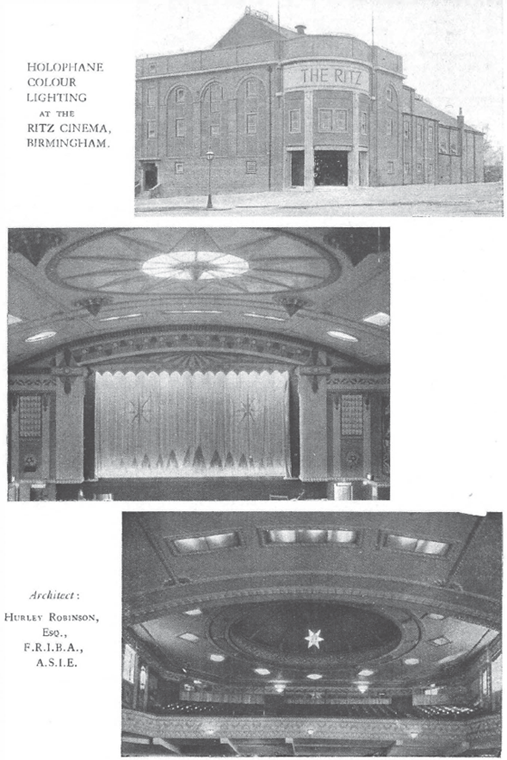

Despite Britain’s reputation for being not as advanced as Germany in introducing modernist architecture and appropriate décor for theaters, innovative experimentation with colored lighting did occur. Holophane, a British manufacturer of lighting-related products founded in 1896, pioneered in promoting its mobile-color lighting equipment. Its name derives from Greek holos, meaning wholly, and phainian, meaning luminous. Based on the inventions of French and Greek scientists André Blondel and Spiridion Psaroudaki, international affiliates were established in the United States, France, and the UK. The British company supplied equipment to cinemas, and the products were marketed with great enthusiasm by Rollo Gillespie Williams, Holophane’s chief color engineer and consultant. The Holophane Theatre Lighting Division was “dominated entirely by a passion for mixing coloured light,” and this led to inventions designed to illuminate auditoriums and decorative light fittings capable of changing color.105 The system employed three or four colors (red, blue, and green, or red, blue, green, and white), and by combining two or more of these in different proportions, any desired third color could be obtained by the use of dimmers in circuit with lamps. The ability to produce color mixing—to change color combinations—was at the heart of Holophane’s marketing pitch for “painting with light.” In 1923, thanks to its reputation for quality and innovation, the company was entrusted with lighting St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. In the 1920s, both cinemas and places of worship were subject to increasingly elaborate lighting effects. Kracauer’s judgment that artificial lighting represented spiritual poverty fails to acknowledge that mobile color was also seen as a means of enhancing religious enlightenment. “Cathedrals of the Movies” were somewhat ironically connected to broader ideas about displays of light and color affecting the spirit, senses, and emotions. Taking full advantage of developments in electrical engineering in the 1920s, Holophane was thus poised to corner the market in lighting public entertainment venues. Lamps, colored filters, prismatic reflectors, footlights, spotlights, wing floods, dimmers, and switchboards were used to create displays that were shown before and even during a film performance. Holophane battens were designed so the reflectors lit vertical planes, giving a powerful intensity of light in multiple directions. It was claimed in 1929, “Many Picture Palaces to-day utilize a mobile colour-lighting equipment frequently superior to that used in the theatres. Colour-effects tend to be used more and more as a supplement to the display of the film, to create the desired atmosphere and to emphasize the story.”106

Examples of Holophane applications ranged across the UK, but one interesting report referred to a “music, colour and dancing” show being staged in November 1928 as part of the Electrical Exhibition in Swansea, South Wales. The show was intended to demonstrate what could be done with colored lighting; it lasted one and a half hours and used local dancers for a musical-color revue. The show began with the front curtains illuminated by colors changing to a musical accompaniment. Twelve performances followed, including a shadow dance in which the backcloth and dancers were illuminated with white light, but “the shadows of the dancers were sharply outlined in all the colours of the rainbow.”107 The show was so popular that people had to be turned away, and repeat demonstrations were organized. It was noted that “exhibitors in small towns sometimes raise the objection that while colour-lighting may appeal to city audiences, they do not feel that small towns will understand or appreciate colour-lighting artistically applied.”108 These assumptions about urban sophistication and modernism produced surprise at the success of the displays in an area badly hit by unemployment and with audiences “of no higher level of education than the public in other towns.”109 The experience at Swansea proved that the attractions of mobile color and lighting spread across locations, classes, and tastes.

Holophane’s “Duo-Phantom” color lighting system appeared to change a cinema’s decoration by lighting it in different colors, often changing as combinations of colors produced varying effects.110 The first UK cinema to install a complete Holophane Duo-Phantom system was the Ritz Cinema in Birmingham. The modern décor was planned in conjunction with Holophane so that “one moment the interior of this theater may appear in beautiful shades of refined and delicately blended tones, and immediately the scheme can be changed, and the auditorium flooded with rich and glowing colours, the whole atmosphere of the hall and the colouring of the decorations being different.”111 Advertising implied that colored lighting effects were intended to support the film drama, enabling films to “float in a mist of color”—it seems that prologues were common for films and that this was an intended use, as well as coloring curtains framing the screen.112 Preparing the audience for a particular film involved lighting performers in appropriate colors to match the main film’s theme and even characters. Holophane claimed to have championed the benefits of film prologues featuring colored lighting “long before they were really tried out” in the UK. The role of color in cueing an audience to appreciate a film can be related more broadly to silent cinema aesthetics, in which devices such as an opening emblematic shot (a shot that encapsulated the essence of a film drama) served a similar function.

These practices of lighting were integrally connected to color music, as explained by Rollo Gillespie Williams in a lecture given to exhibitors in 1927. The report on his lecture noted:

For orchestral interludes it was demonstrated that the use of color on some simple lines, producing a sunset on a desert scene, the colors gradually changing all the time, materially increased the effect of the orchestra and held the audience far more than the music alone would. A film was then projected and was made to float in a surround of color, this color changing as the film went on. The film picture could be tinted with color if desired by means of the control gear of the equipment. The lecturer contended that the color bordering should be changed to suit the emotional change of various scenes just a little in advance, so that in conjunction with the music it would tend to suggest to the audience what was shortly coming in the story. When the title came on the screen, the wording stood out in a colored instead of the ordinary black background.113

It seems that the colored lighting was an enhancement to the screen entertainment, preparing audiences for it and intensifying its impact throughout. In addition, Holophane produced “atmospheric stage curtains” made of a fine white gauze specifically designed to display colored lighting with musical accompaniment. The curtains were “specially festooned, draped or tucked in such a way that the manipulation of the colours produced at any moment by the Holophane batten and footlight will create on the gauze a series of beautiful colour-contrasts, broken by intermediate splashes of pastel tints.”114 The emphasis was on creating different atmospheres “to emphasize the psychological appeal of the programme.”115

Alvin Leslie Powell, an authority on theater illumination, wrote about the situation in the United States, where experiments with colored lighting were also widespread. He noted: “Most of the larger motion picture houses have color lighting installations which they use during the playing of the overture or musical interlude. Some have cove or cornice lighting in which colored lamps are concealed, and light from these is directed on the ceiling and walls; other houses employ large ornamental fixtures fitted with several circuits of colored lamps, and still others are able to flood a neutral tinted curtain with colored light from above, below, and the sides.”116 As for the future, Powell predicted that musicians would be very prominent in the control of color lighting, more so than electricians, and that musical scores would “contain a schedule of color changes prepared jointly by a musician and psychologist.”117 The commentary included observations about public taste in music being improved by the combination of music and lighting, echoing the views of Mary Hallock Greenewalt and many others. In turn, the reputation of the motion picture house would be improved, and its prestige enhanced immeasurably. In this vein, Loyd Jones’s kaleidoscopic effects were used as preludes to film shows in Rochester, New York, as discussed earlier.118 Belief in the efficacy of color consciousness thus created links between avant-garde and popular forms in numerous ways while it pushed discussion of and concern about color from the screen into the auditorium and beyond.

Adrian Klein similarly advocated using cinemas as venues for color music and illumination experiments, citing the Capitol Theatre in New York:

The usual practice of this theatre is to interpose between two films an orchestral performance (the theater possesses a magnificent symphony orchestra) sometimes with ballet. The orchestra plays upon the stage below the screen. The background is a vast semicircle of diaphanous drapery upon which the battery of projectors plays a continuous, perhaps somewhat disordered, but nevertheless remarkably beautiful series of lighting schemes. Perhaps the American cinema will witness the first ordered displays of coloured light, and so assist the development of the technical equipment for which the light composer longs.119