Chapter

3

Preparing a Crisis Communications Plan That Actually Works

We now have a basic understanding of the need for effective crisis communications in companies and other organizations, and the critical interplay of legal, business, and perception issues when organizations face unexpected situations that threaten to have negative reputational ramifications. We’ve also looked at the role of the Chief Crisis Officer and the need for leadership and structure in the creation of your core crisis communications team.

But how do you actually translate these new skills and resources into practice? You create a crisis communications plan—an action plan that ensures the machinery works well when a crisis hits. Beware, though: As you’ll learn in this chapter, true crisis communications planning is often absent in even the most forward-thinking organizations. When crisis communications planning does exist, it is often inadequate to address real needs. In this chapter, we’ll discuss why that is and what you can do about it.

In other words: How you can create a “living” action plan for responding to crisis events, one that—perish the thought!—actually works.

“Indeed, many businesses are able to secure lower insurance premiums if they have written crisis management procedures in place …”

—Crisis Management: Master the Skills to Prevent Disasters, 20091

We’ve got a crisis communications plan, alright. It’s a piece of crap …

—PR director of a Fortune 500 manufacturer

I am in the offices of a major global retailer in Texas. The subject at hand is crisis communications planning. The Senior VP of Public Affairs for the company is lamenting the poor state of his crisis communications plan, his assistant nodding in agreement.

He points to the bookshelf in the corner of his office.

“There’s our crisis plan right there,” he says. He gets up from the conference table, pulls a thick binder off the shelf with a grunt, and slams it down on the table with a resounding thud. For a moment, I fear the table might collapse under its weight.

The binder has a well-designed, custom-made cover with the company logo emblazoned in white on the front. But from the dust now floating in a stream of light through his office window, I have a hunch what he’s going to say next.

“$50,000 … three hundred pages … and nobody uses it,” he says, sitting back down.

He flips a few pages. The assistant adds: “Half of these contacts aren’t even here anymore.”

A few more pages, then:

“This all also exists somewhere on our company’s servers, but I have no idea where.”

He looks across at the assistant: “The K drive?”

“N drive.”

“N drive. Whatever. The point is: I wish we had a tool we actually used.”

He stops talking and stares at me for a moment. I ask: “Well, what do you do when a crisis occurs?”

He laughs.

“I search my email to see what we did last time. Find some examples of statements, call a handful of people I consider ‘go-tos’ when a crisis occurs … see who’s around.”

A final pause.

“… basically, we just wing it.”

How to Create a Plan Nobody Uses

I’d like to say the exchange above is unusual, but it’s not. I’ve been to companies of all sizes over the years and I’ve had the same exchange time and time again.

The dirty little secret of crisis communications is this: Most crisis communications plans are thick, bloated tomes that no one ever uses—if they are created at all. In reality, most companies, including large companies that you think would know better, sometimes don’t even bother to have a crisis communications plan. Those that do tend to create final documents that are not user-friendly; therefore, the communications plan is not used when the eventual crisis occurs.

At a Fortune 100 technology firm, I asked whether the resources in the crisis communications plan were ready and accessible.

“Well, sort of … we have same statements, templates, that sort of thing, both in the hard copy plan and somewhere on SharePoint* … but I’ve never quite learned how to use that system,” the communications director told me.

“So when I need a statement, I just pull the binder down, flip the pages, and retype it by hand.”

And this was a technology company. Clearly, across all industries, Corporate America has a real problem with crisis communications planning.

Research backs up this statement: According to a 2011 survey by the global PR firm Burson Marsteller, 46 percent of global business leaders say they do not have a crisis communications plan in place. A full one-half of those who do have a plan in place say that although it may assist in the handling of a crisis to some extent, it is inadequate for their needs.2

Why create a crisis communications plan at all if everyone hates them, and no one uses them? Like much of what happens in the corporate environment, crisis communications plans are created for reasons that sometimes have little to do with their actual utility during a crisis. In my experience, these reasons can include:

- We heard we should have one. It’s PR 101. Every public relations trade publication I’ve read—and many business and insurance trade publications as well—say that you should have one. Besides, our agency of record recommended it (and then they sold it to us!).

- The Board of Directors told us to create one. The board is charged with being the strategic mind of our corporation, after all—they are all about mitigating risk and maximizing opportunity. If they tell the CEO to create a crisis communications plan, we’re going to create a plan.

- Our insurer likes to see things like this. Insurance companies are the ultimate risk managers, and as part of their regular review of policies and practices, they recommended we create a crisis communications plan. I know it’s reducing our overall insurance rates … or I’ve been told it is reducing our rates, anyway.

- We had extra money in our budget line that we needed to spend before year-end. If I don’t use that budgeted money this year, I may lose it in next year’s budget. (This happens more often that you’d think in the corporate environment.)

You’ll notice that none of these reasons have anything to do with the actual improvement of the crisis communications response itself. Rather, it is about satisfying board or operational imperatives. And while it is entirely possible that, in the service of satisfying these imperatives, a company will create a useable plan, it tends to not be their goal. In other words, organizations create something they can show, not use.

To be fair, some might argue in favor of a larger crisis plan—particularly the PR firms that are selling it to you. They tell you that all of your relevant information must be in a single location—forms, templates, checklists, media lists, a list of organizational contacts, a statement of the company’s approach to crises, its belief in being transparent to all of its stakeholders, and so forth. In my own cynical view, the reason for this is: The outside PR firm believes they must produce a big document to justify the cost of the project.

In other words, your PR firm needs “a deliverable” (usually a big one) to justify the cost of the product they just sold you. If a 30-page plan is worth $5,000, surely a 300-page plan is worth $50,000.

This is the reason why most organizations wind up with a “table-breaker” of a crisis communications plan—a weighty tome filled with position statements, philosophy, forms, and contact information (both internal and external). This information tends to be outdated before it even lands on your public affairs director’s shelf; it is rarely used by anyone on the team when a crisis erupts.*

There must be a better way.

What Should Be in a Crisis Plan … Really

A better way exists. Crisis communications teams must keep the focus on what they need, rather than what they think they should have. Strip away all items that are tangential to the task at hand—you can always add them selectively at the end of the process if necessary (perhaps in a separate resource or as appendices to your main plan). Start with the express goal of beating the bloat, and stick to it. Every decision on what to put into your crisis plan and what to leave out should begin with the premise that bigger is bad.

Put another way: As in most things—and all communications-related areas—think “digestibility.” Work backward from the following goal: creating a crisis communications plan that can be digested easily in the heat of the battle. Keep your eyes on this prize and success will follow.

Technology can be a facilitator of this effort. In Chapter 7, we’ll review technological solutions that can help streamline the process of both crisis communications planning and execution when a crisis or other sensitive communications matter occurs. Be warned though: Technology can also be the great enabler. In other words, if you can create a 500-page document thanks to the ease of content creation in this modern age, you will. And if your IT department can create a complexity-laden technological solution that’s exciting to computer science folks but useless when a crisis erupts … well, you get the point.

As such, there needs to be cognizance at each step of the process of the fact that you are not creating a binder or a complicated set of folders on your company’s intranet. You are creating an action plan. A roadmap.

In fact, let us stretch the map analogy even further. Ideally, in this technological age, you will create not just a map, but rather a Google Maps of crisis response. Not a static document, but a living document. One that can be changed as that new Interstate connector is added between Raleigh and Durham, or a new airport is added in Dubai.

And, like Google Maps, it should be simple. If you use simplicity and flexibility as your North Star, you won’t go wrong.

You’d be surprised how heretical this approach can be in the hallways of many companies: Anyone who has been trained in crisis communications, in public relations, in general MBA-style courses in crisis management—not to mention as lawyers—likely feel that you need the “book,” whether in hard copy or electronic form, to respond correctly during a crisis. But, as we have seen above, a thick binder is more likely to be the weight you use to prop the door open as you run from the building during a crisis than the tool you use to respond. Forget about what you’ve been told you should have and focus on what you need. Work backward from the goal.

The Essential Tool

Based on my experience in the crisis communications field, here are the elements of a crisis communications plan in its most basic form:

- You need a roadmap for action for when a crisis occurs;

- You need a way to bring the crisis communications team together quickly and efficiently in the early stages of a crisis; and

- You need pre-prepared tools and resources at your fingertips and the proper methodology for distributing this communication to your various publics and stakeholders after the crisis occurs.

That’s it. All else, as the rabbis say, is commentary. Crisis plan creation involves identifying potential future problems, which could range from technical glitches, product recalls, cyber-attacks, or facility fires to activist investor troubles or litigation. From there, assign clear responsibilities to each member of your crisis communications team and make sure each person can jump into action when the crisis hits. You also need templates for press releases, employee emails, and social media updates at-the-ready.

Finally, once you have all this together, you need to make sure the plan works. That’s where training comes in. You must work the team through the crisis process, putting the plan into action in various scenarios based on the most likely crisis situations your organization might face. This is the only way to truly know whether the plan is effective and accessible.

If used well, technology can be key to this accessibility. We live in a world where technology is disrupting every industry. If your organization still has its crisis plan sitting in a binder on a shelf or buried somewhere on your server, it’s never going to be used. Again, be forewarned: Technology is only helpful if it facilitates the process, frees the crisis plan from the static pages of a binder, and breathes life into the entire crisis communications response.

And this is key: a crisis plan should be a “living document”—without getting all TED Talk on you, it should be a verb, not a noun. Action, not prose, is what your crisis plan is all about.

How to Create a Crisis Plan That Actually Works? Just A.C.T.

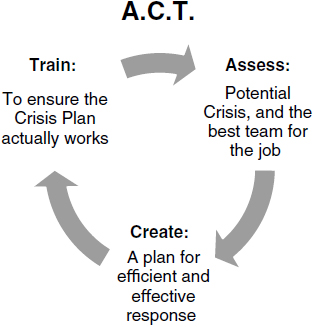

I usually shy away from acronyms that spell out cutesy words when labeling the various communications processes I espouse, but in this case, I’m going to use one, as it fits so well with the action philosophy needed in crisis communications planning. When creating a crisis communications plan, my advice to companies of all sizes is to use the acronym A.C.T., which stands for Assess, Create, and Train:

- Assess potential crises and the team(s) who will handle them;

- Create a plan of action that includes the checklists, templates, and other resources you will need in the event of a crisis; and

- Train the core team, as well as the broader team where applicable, in tabletop or other virtual scenarios to ensure the plan is executed properly in a variety of situations.

Moreover, it’s best to think of A.C.T. not as a one-time project, but as a cycle.

Without getting too cute about it, you should constantly be in ACTion. Crisis communications planning becomes a continual business process through which you develop the type of “living” approach to crisis response that will provide you with the highest level of value as you confront the inevitable. In other words, you are in a constant cycle of assessing the potential matters your organization may confront and the personnel best suited to handling such issues, creating the structure and resources needed to effectively respond, and training to ensure the plan works in the heat of a real-time crisis.

After training or in the wake of response in an actual crisis situation, you assess what worked and what didn’t to help better create and execute your plan when a crisis occurs.

Figure 3.1 provides an illustration of the “living” A.C.T. system:

Figure 3.1: The continuous A.C.T. process during crisis communications planning

Without unduly burdening your organization, if you follow the A.C.T. cycle, a Chief Crisis Officer and his or her team will have a crisis plan that is accessible, actionable, and alive.

To further understand the A.C.T. system, let’s look at each these elements and how they come into play during the creation of a crisis plan.

Assess

Simple but elemental, this is the first step of the process. The core crisis communications planning team—led by the Chief Crisis Officer—must identify the many potential crisis scenarios the company could face and come up with the teams, tools, and systems that will help them respond. These distinctive crisis events could be related to accidents, data breaches and other technological issues, product recalls, physical attacks on offices or employees, facility fires, and other matters.

I provide a more comprehensive list below, but here is an important point to remember: Keep the list manageable. Refine your scenarios to a select number of core situations that represent the types of events that are most likely to occur. For example, don’t include every possible variation of a facility fire or cyber-attack (i.e., a fire in the materials intake facility versus a truck fire in your the loading dock). Although the situations are different in some ways, they likely have the same basic elements. You will drive yourself and everyone around you crazy if you think of every possible variation for every crisis scenario—so resist the temptation.

It does happen. Recently, I was at a meeting with a client and asked about scenario planning for a single product issue where the company was facing a potential crisis. The head of public relations proudly announced that with the assistance of the legal department, they prepared a list of potential scenarios the company might face in relation to the matter. She then pulled out a four-page spreadsheet with no less than 45 different potential crisis events and scenarios related to the product and 16 different columns of activities related to each potential scenario.

This spreadsheet was comprehensive, but ultimately unusable in the event of a real crisis. It contained too much information to digest and sort.

Based on my experience, a limited universe of actions and events can befall an organization with the potential for negative reputational ramifications. I often break these potential scenarios into the following general categories:

- An accident or physical event;

- A product or service issue (which might include anything from a product recall to a service complaint);

- A cyber or IT issue, including data breaches and the like;

- An employment-related issue, such as a firing, a labor action, or a discrimination claim;

- A financial issue with negative impacts on the company’s reputation (as opposed to just the company’s financial performance or some other non-reputational aspect of business operations);

- A governmental or political issue;

- A legal matter, including litigation, investigations, or adverse regulatory action; or

- A general reputational attack on your organization, its products or services, or personnel.

Each of these categories may have a few subcategories that could be added—these subcategories will depend on many factors, including the industry you are in and the size of your organization or number of locations. The key takeaway is as follows: You must review your company’s business operations and come up with a manageable number of issues and events that your organization might confront. How many scenarios are right for your organizations is up to you, but keep in mind: Simplicity is the key to success.

One other note on assessment: As you assess the types of crises with which your company may be involved, you should also assess:

(a) Your personnel, that is, the crisis communications team ready to spring into action when a crisis occurs, along with a broader team that will be included in the process depending on the actual type of crisis or issue you are facing; and

(b) The logistical and technological tools that can be brought into service to facilitate the process of both preparing for crisis situations and responding when the inevitable crisis occurs.

We took a closer look at personnel in Chapter 2 when we examined the role of the Chief Crisis Officer in your organization and the core crisis communications team. Similarly, we’ll examine logistics and technology more closely in Chapter 7.

Create

Okay. So you’ve done your assessment, and you know the types of crises and issues your organization might face and the team that will execute your crisis response protocol. Now you need to create. This is where we get to the nuts and bolts of your crisis communications plan.

Earlier in this chapter, we discussed the three basic items you need when creating a crisis plan: a roadmap for action for when a crisis occurs; a way to bring the crisis communications team together, quickly and efficiently, in the early stages of a crisis; and pre-prepared tools and resources at your fingertips. So let’s look a bit more at these elements.

A Roadmap for Action

The word “roadmap,” I suppose, is self-explanatory: It is a mixture of graphics and words that shows you where to go. The map should be as detailed as necessary for the audience and the mission at hand. A simple roadmap to get from my house to the Macy’s in the mall might only show a few roads and have a few labels. A detailed Rand McNally of New York City is much more complex and detailed, with in-depth information and descriptions, but still (hopefully) instructive at a glance when trying to figure out how to get from Battery Park to the Macy’s flagship store on 34th Street (although the extra detail, in some cases, might become a hindrance). Here lies the inherent tension there between information and simplicity. Done right, however, a proper roadmap should be perfectly designed to get you where you want to go.

So, too, with your crisis communications plan: Like a roadmap, it should be exactly as complex as needed to get the job done. It should clearly and simply tell you what to do and where to go when confronted by a crisis or other sensitive reputational situation. Your plan should guide you to your destination in an intuitive, user-friendly way.

In practice, your plan will require a series of guides and checklists to lead you through the response protocol for the various scenarios you identified during the assessment phase of the A.C.T. planning process.

For example:

- For an accident, fire, or other physical incident at one of your facilities, the crisis plan should immediately identify what type of communication response is needed, who should be notified as part of the core crisis communications team, who needs to be added to this team (e.g., a facilities manager, a director of security or fire safety, etc.), and what steps are recommended in the process for responding.

- For a data breach at one of your IT processing facilities, you will look for a different set of crisis responders, including an immediate meeting with IT staff and data security experts and the involvement of the company’s legal department to determine the notification requirements in the various states in which you operate.

- For an employment discrimination complaint, the first step could be a request for relevant documentation (obviously with confidentiality laws in mind), a conversation with your company’s outside employment lawyer, and a meeting with your director of Human Resources.

This roadmap can be in the form of a bulleted narrative, a graphic workflow chart with arrows and boxes, or a checklist (or series of checklists), depending on what will work best for your organization.

As an example, we often use the following checklist when confronting an accident or physical event at a company facility:

SAMPLE CHECKLIST

ACCIDENT OF PHYSICAL EVENT

In the event of an accident or other physical event at one of our facilities that will require a communications response, the crisis communications team should take the following steps to begin coordination of response:

![]() Identify the crisis site or location and nature of the incident.

Identify the crisis site or location and nature of the incident.

![]() Identify the appropriate on-site manager who will serve as liaison to the crisis communications team.

Identify the appropriate on-site manager who will serve as liaison to the crisis communications team.

![]() Speak to security about securing the facility, including procedures for restricting media access to the site.

Speak to security about securing the facility, including procedures for restricting media access to the site.

![]() Open a Virtual WorkRoom on CrisisResponsePro.com and gather the core crisis communications team, including legal counsel and, if appropriate, outside crisis communications consultant.

Open a Virtual WorkRoom on CrisisResponsePro.com and gather the core crisis communications team, including legal counsel and, if appropriate, outside crisis communications consultant.

![]() Decide whether to set up a media center onsite if needed.

Decide whether to set up a media center onsite if needed.

![]() Coordinate with legal departments regarding preservation of the crisis scene and legal/regulatory restrictions

Coordinate with legal departments regarding preservation of the crisis scene and legal/regulatory restrictions

![]() Determine whether company’s online crisis media center should go “live.”

Determine whether company’s online crisis media center should go “live.”

![]() Notify insurance carrier(s) and other third-party insurers/indemnitors as to accident.

Notify insurance carrier(s) and other third-party insurers/indemnitors as to accident.

![]() Beginning gathering information from managers and incident response personnel on-scene and formulate initial strategy regarding communications by the company.

Beginning gathering information from managers and incident response personnel on-scene and formulate initial strategy regarding communications by the company.

![]() Crisis communication team should take the lead in drafting the initial statement regarding what is known. This includes a statement for the media, talking points, and email or other communications for employees. NOTE: StatementReady templates should be accessed and edited carefully. Limit statement to facts presently known.

Crisis communication team should take the lead in drafting the initial statement regarding what is known. This includes a statement for the media, talking points, and email or other communications for employees. NOTE: StatementReady templates should be accessed and edited carefully. Limit statement to facts presently known.

![]() Spokesperson(s) should be identified and appropriately briefed.

Spokesperson(s) should be identified and appropriately briefed.

External Communication

![]() Short standby statement and talking points for spokesperson(s) finalized.

Short standby statement and talking points for spokesperson(s) finalized.

![]() Twitter guidelines should be followed to compose initial Tweet.

Twitter guidelines should be followed to compose initial Tweet.

![]() Online media center should go live (if appropriate), and a copy of standby statement should be posted to Facebook

Online media center should go live (if appropriate), and a copy of standby statement should be posted to Facebook

![]() Key media identified, including the “lead steers” who will drive coverage.

Key media identified, including the “lead steers” who will drive coverage.

![]() Crisis communications team should work closely with internal IR resources to determine how to continually update key members of the financial community as the crisis unfolds.

Crisis communications team should work closely with internal IR resources to determine how to continually update key members of the financial community as the crisis unfolds.

Internal Communication

![]() Email or other communication to employees finalized and disseminated.

Email or other communication to employees finalized and disseminated.

![]() Talking points for managers and sales staff finalized and disseminated.

Talking points for managers and sales staff finalized and disseminated.

![]() “Public-facing” internal staff, including security guards, receptionists, and others, should be briefed, provided talking points, and reminded that no one should speak to the media.

“Public-facing” internal staff, including security guards, receptionists, and others, should be briefed, provided talking points, and reminded that no one should speak to the media.

![]() All questions should be forwarded to the crisis communications contact.

All questions should be forwarded to the crisis communications contact.

![]()

Again, the actual content and structure of this roadmap for the various crises you may face are up to you, but it is important to remember that the roadmap must be accessible and intuitive. In all elements of crisis communications planning, the thinking should have been done well before the crisis hits. As a crisis unfolds, it is time for doing.

Bringing the Team Together

My wife was a social worker for many years at school for the physically and mentally impaired. When a snow day or other issue arose, the principal had a phone tree in place: She called the three top members of the team; they each called three more, who then called three teachers and so on.

Although rudimentary, the phone tree was nonetheless an effective way to alert the school’s entire team that an unexpected event had occurred that would impact the schedule.

When preparing your crisis communications plan, ask yourself: What’s your version of the phone tree?

At many organizations, even the notification process itself is ad hoc: Whomever learns about the issue calls their superior and so on as the news works its way up to the level deemed appropriate for the type of crisis the organization is facing (perhaps all the way to the CEO, COO, or General Counsel level). One of the individuals who has been called (sometimes the CEO’s assistant) then attempts to convene an initial conference call to figure out the situation. Along the way, hopefully, someone remembers that the company already has a crisis communications plan in place for just such a situation, and this plan has already identified a team delegated with coordinating response. Hope springs eternal, but in reality, the crisis communications plan is often forgotten about entirely.

My point is this: If my wife’s school can do it, so can you. Ensure that proper notification is baked into your crisis communications plan, including notification of the Chief Crisis Officer and members of the core crisis communications team. As discussed in the preceding chapter, every senior manager in the company should know who the Chief Crisis Officer for the organization is and have that person’s name front-and-center on his or her Rolodex (or, in modern parlance, their Contacts). Make them post it on their wall; set it as the homepage on company smartphones; tattoo it on their foreheads if you have to. This initial notification of the Chief Crisis Officer and his or her team is where it all begins.

Technology can be a key driver of this process—particularly crisis communications software with a simple notification process that can be set in motion with a few clicks from the portal’s homepage from any smartphone, tablet, desktop, or laptop. The core team can be supplemented depending on the exact nature of the crisis at hand.

Whatever technology you use—phone, text, email, 20th century, or 21st—make the protocol for notification a central part of your crisis communications plan to ensure that the team you worked so hard to identify, bring together, and train is immediately activated when a crisis erupts.

Tools and Resources

Finally, every crisis plan should contain tools and resources that the team can access in the event of a crisis to guide the process of communications response. In most cases, this will be a set of templates tailored to the various scenarios you identified as likely to occur.

Templates are amazingly effective—and not because you are going to use them word-for-word. Far from it, in fact: In most crises, the team will edit the initial template considerably before it is posted on the company website, Tweeted, emailed to employees, or sent out to media.

But the value is this: the proper templates give everyone on the crisis team a starting point for preparing the messages that will be distributed to various public audiences in the event of a crisis. So in providing such a starting point, you are mechanizing the process. There is no need for discussion or back and forth. The team, with buy-in from senior management, has already agreed on a set of messages and their application to the various crisis scenarios you developed.

Without preapproved templates, the entire process can be gummed up by that well-meaning wordsmith in the communications department who believes he or she has a better way of writing the statement or that traditional-bound lawyer who believes the company should say nothing at all lest they subject themselves to some miniscule risk of potential liability. These concerns were already considered and dispensed with when the plan was approved. The process is streamlined, and you can get your message into the hands of audiences that need it quick.

We’ll examine the actual content of our templates in Chapter 5, which discusses proper messaging in crisis situations. In the meantime, I’ll leave you with one last thought: If you’re going to create a comprehensive set of communications messages for various crisis scenarios, you must be able to find them. As in all things crisis communications, accessibility is key. Too many times I’ve seen crisis communications managers look for the approved template somewhere in the crisis plan on the company server or in their email trail, fail to find it, give up, and start typing something new. Throughout your crisis plan, you need easy identifiers and visual clues to ensure this information is at your fingertips exactly when you need it.

The Use of Visual Elements

This brings me to the use of visual indicators like tabs, side-borders and color in crisis communications planning. As you know, one of the things I emphasize in this process is that a crisis plan should be simple and easy to use. To reiterate, it is a roadmap, and there are reasons roadmaps are in color, with visual indicators like symbols and keys.

Color, for example, can help lead the eye to the right places: on most maps, interstate highways are red, turnpikes and other toll roads are often green (as in you’ll be shedding some green to use the road), bodies of water are blue, and so forth. The mind registers color more quickly and effectively than words. Thus, if you can create a tool using color, you will naturally encourage quicker and more efficient use of that tool.

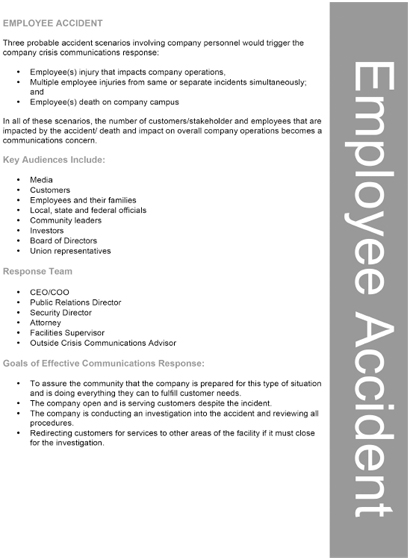

Hence, when my firm has assisted in the creation of crisis plans using the traditional binder system, we have been very big on margin columns, borders, and color-coding sections and pages for easy use. After experimenting, we came to the conclusion that a right-margin color-coded bar works best to catch the eye as you page through the binder (in addition to the usual assortment of tabs and other section dividers you routinely find in any corporate binder). Figure 3.2 provides an example.*

Point to be made: like a roadmap, find ways to use colors, symbols, and other visual clues to get your crisis communications team where they need to go. In other words: If you have to use a binder, us it well.

Figure 3.2: The use of visual indicators to attract the eye’s attention to specific information in a crisis communications plan

The Crisis Flash Sheet

My company has experimented over and over with various tools and shortcuts that could help a crisis plan become more useable in the event of an actual crisis. In other words, we looked for ways to avoid relying solely on a traditional binder when preparing the plan.

We created a 10-page, spiral-bound hanging plan that could be kept on a hook on the factory floor and in administrative offices. We used color-coded sheets that identified the particular category of crisis along the outside edge of the page for easy reference. We even created tri-fold wallet cards that could be carried by key executives and be pulled out in the event of a crisis.

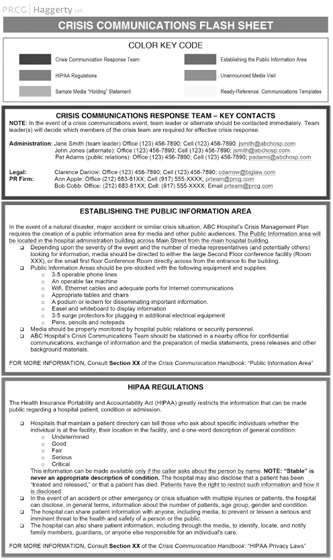

My favorite, however, was what we called the “Crisis Flash Sheet”—an 8½-×-14-inch, laminated, two-page document similar to what is used by National Football League (NFL) coaches for play calling. The Crisis Flash Sheet is supported by a traditional binder that contains appropriate background and factual information—the templates and checklists, contact sheets and media lists, and all other material necessary to make crisis communications effective. It remains a staple of our crisis communications planning. Recently, we have combined this tool with a user-friendly, cloud-based “virtual war room” technology to allow companies to effectively call the types of plays that will help ensure a crisis response that reassures the public that your company is ready and able to meet the challenges at hand.

The Crisis Flash Sheet allows the executives in question to have the most basic information needed for crisis response at their fingertips, which is especially useful in the wake of “explosive” crises, such as events related to accidents, violent acts, natural disasters, and other workplace incidents.

For those of you who are not familiar with the NFL’s system, a brief description is in order. More than a decade ago, NFL coaches started to use laminated sheets of various sizes that contained every play the coach might call in various situations, a list of calls by referees and whether they can be challenged, and even a formula for when to call a field goal or two-point conversion. The placards, which look like a food menu, serve as useful “cheat sheets” for football coaches, who could be considered the ultimate crisis managers. In the heat of unpredictable events, the coaching team must make a series of high-pressure, real-time decisions with enormous ramifications for the organization. Some cards contain descriptions of more than 100 plays a coach might call in various situations, sorted by situation, strategy, and staffing.

Although all NFL teams have full playbooks, usually totaling hundreds of pages, it wouldn’t be easy for a NFL coach to tote one of these suckers on the sideline during a game.

Sound familiar? We had this idea in mind when we created our Crisis Flash Sheet. Why 8½ × 14 inches? Simple, because you can see it. The Crisis Flash Sheet can sit on a bookshelf with other key corporate documents, but it is 3 inches taller than your typical 8½-×-11-inch corporate document, book, or magazine. Thus, it is easy to pluck off your shelf when the first news of a crisis reaches your desk.*

When we create these Flash Sheets, they are highly tailored to each particular client, with the exact information they need for their industry, size of company, number of facilities, and other criteria. In Figures 3.3 and 3.4, you see a generic version of an actual Crisis Flash Sheet that we created for a small hospital system client.

The Crisis Flash Sheet given in these figures is just one example—what you include on your Crisis Flash Sheet will vary based on the particulars of your business. That said, I think it is instructive to review the Crisis Flash Sheet in detail to give you the full flavor of what we created.

First, you’ll notice that the Crisis Flash Sheet is color-coded for easy reference, with a quick key at the top front to direct you to the right section. All of this is by design, of course, and comes from our aforementioned experience in streamlining the crisis response system during the first critical minutes after notification. Color directs you to the right section of the flash card far quicker than a Table of Contents.†

In this case, we looked at the overall range of issues the hospital faced. Working with the CEO, public affairs executives, and the legal department, we determined exactly the information that would be needed in the event of a sudden, public-facing crisis. Again, it is critical to understand that this is not a cookie-cutter process. The team tasked with creating the crisis plan, as well as the Crisis Flash Sheet, should deeply understand exactly what information needs to be at the team’s fingertips during the front end of a crisis to respond most effectively and efficiently when a crisis does, indeed, occur.

First, the hospital needed a listing of who was on the core team, with ready contact information. In this case, we identified the hospital’s “Chief Crisis Officer” and an alternate, along with the institution’s internal PR executive. We then identified a lawyer for the team and two outside crisis communications specialists (in this case, from my firm).

Figure 3.3: Crisis Flash Sheet, Front

Figure 3.4: Crisis Flash Sheet, Back

That’s it. The core team can and would be supplemented by others depending on the particulars of the crisis situation in question, but this was the immediate group—the SWAT team (as you saw in Chapter 2) trained and ready to be engaged in the early stages of a crisis to put the plan into action.

Next, we thought about the types of crisis events that were most likely to befall a healthcare institution like a hospital. For example, many events—like an accident, fire, police emergency, outbreak, or patient issue—send media directly to the hospital for information. After all, if a multi-fatality accident, terrorist incident, or disease outbreak occurs in your city, media don’t just lob polite calls to the PR department of the institution. They show up. As such, you need an area to put them—a room or rooms to provide them with the support they need to report on the crisis event.

With that in mind, the second section of this Crisis Flash Sheet contained an “Establishing the Public Information Area” to bring the media together and provide them with the information they need to report accurately and fairly on what was happening. This section provided the building and room number for the media to use, their phone line and Wi-Fi information, and all the other logistical support needed to ensure the room allowed journalists to work and report as a crisis unfolds.

The third section of the Crisis Flash Sheet contained information particular to healthcare institutions. One of the first concerns brought up whenever a health-related organization faces a crisis issue is what can and cannot be said under the restrictions of what are commonly known as HIPAA laws.* This knowledge is critical for hospitals and other healthcare facilities. Often, in the opening stages of a crisis, there just won’t be time to remind front-line public relations and other executives as to the nuances of what information can be shared. This has two implications. First, during a time of crisis, the institution might say too much and run afoul of HIPAA guidelines. Secondly—and this is just as important—they may say too little and create more controversy, unanswered questions, rumors, or skepticism, because they assumed they were unable to say anything due to the HIPAA laws. Thus, we created a simple description that could be prominently displayed on the front of the Crisis Flash Sheet that immediately told the institution’s crisis team what they needed to know about HIPAA when distributing information in the initial stages of a crisis.

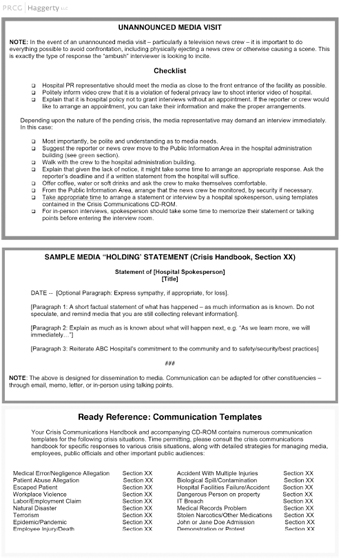

On the other side of the Flash Sheet, we prepared a section for the “Unannounced Media Visit.” In our discussion with this particular client, one of the problems they faced on a regular basis was reporters and news crews showing up at the medical center unannounced for one investigative report or another. It was a real issue for this hospital.

We used this section of the Crisis Flash Sheet (which used a fair amount of the sheet’s “real estate”) to detail, step-by-step, what to do if media showed up unannounced at their door. This section helped the hospital avoid scenes like the hand-over-the-camera-lens response that is sure to generate a media story or escorting media out of the reception area where they might cause a scene in front of your employees, customers, or other important parties (which is usually what reporters want). This section also recommended using a written statement to avoid an on-camera interview and using security only as a last resort. All of these items are critically important and exactly the information needed for this institution.

The next section was also critically important to this hospital, as it could be to a variety companies in different industries. This section contained a sample statement template that could be used to respond to a physical event, such as an accident, or an unintended event that causes casualties. The client needed a simple a template that could be used as a starting point to write a statement to the media in the first moments after a crisis occurs.

On this particular Crisis Flash Sheet, we provided a statement template that encompassed the following:

- The optional opening is designed to express sympathy for any loss, where appropriate;

- The first full paragraph is a short factual statement about what happened, providing as much information as is known at that moment (as we’ll discuss in Chapter 5, when preparing a public statement, it is vitally important not to speculate or assume facts but rather, where appropriate, remind audiences that you are in the process of gathering relevant facts);

- The second paragraph explains as much as is known about what happens next; and

- The third paragraph reiterates the institution’s commitment to safety, health, and the community (it never hurts to remind your audience of this fact).

Again, our goal with this generic statement on the Crisis Flash Sheet was to provide the basic structure for an initial statement, specifically tailored to the scenario the hospital felt they needed if it was necessary to come up with a statement quickly. In other words, it gave them a place to start.

Simple, you say. Yes, but here’s the underlying truth: To respond effectively, you must have certain information at your fingertips even as a crisis is unfolding in front of you. Not buried in a binder or deep within a computer server somewhere, but right in front of you. Or, in the alternative, a signpost to take you there immediately.

In that vein, the final section (in yellow) was critical and served as an extension of the sample media holding statement in the section above. Here we listed 18 additional template statements for various situations that the hospital could face and where such information could be found in the crisis handbook, on the computer server, and, in days gone by, on CD-ROM. These statements were specific to the particular types of crises this hospital faced, including (to name a few):

- An escaped patient;

- Stolen narcotics or other medications;

- Medical errors or an allegation of negligence; and

- A “John or Jane Doe” admission—that is, the admission of a patient without identification who has not been identified at the time of the media inquiry.

As in the Sample Holding Statement, the goal was to make the right template easy to find as the crisis is unfolding, which is the next best thing to having the full text of the template on the Crisis Flash Sheet. Again, our goal was to take the guessing, questioning, arguing, and thinking out of the process as much as possible, so that when a crisis event hits, everyone knows exactly where to go, exactly what to do, and in what order to minimize the potential for negative reputational impact, even as a difficult, sensitive situation is occurring. So we took what was most important to this client in this situation and made sure it was available in a format that could be used at a moment’s notice.

But That Wouldn’t Work for Me! My Company Is Too Big/Not Big Enough/in Another Industry

If you’re thinking now: “Yeah, Jim, that’s great, but that wouldn’t work for my company …” Well, you’re wrong.

Let me explain why.

You may think: “We’re way too big for a tool like this; I’ve got a dozen divisions and 20 locations around the globe. This ain’t no dinky hospital, Jim, this is a multinational. That Crisis Flash Sheet isn’t going to work for me!”

And you’re right: That Crisis Flash Sheet isn’t going to work for you, but a Crisis Flash Sheet (or similar tool that puts critical information before your eyes) tailored to your particular company and its needs probably will.

Here is my point: The description above is not an attempt to persuade you to use this particular tool but rather to get you to look for ways to streamline the content and materials you use to respond to crises by developing your own version of a Crisis Flash Sheet—for your company, its divisions, and its locations. Just as Bill Belichick (coach of the New England Patriots) has a different NFL play-calling sheet than Rex Ryan (most recently with the Buffalo Bills), General Motors will have a different tool than Apple, Apple will have a different tool than a three-location manufacturing company in the Southwest, and this company will have a slightly different tool than a hospital in a mid-sized U.S. city. I’ve work with companies of all sizes—from the Fortune 500 to small firms, across an array of industries. They all do some things well; they all do a lot of things poorly. Big, complex organizations tend to think they need big, complex solutions in the event of a crisis. They don’t.

The Role of Technology

When you think about it, the Crisis Flash Sheet is just another way we use technology in its broadest sense to provide the Chief Crisis Officer and his or her team with a solution. This is the way crisis communications has developed and should continue to develop: with a mixture of complex technology and simple signs to make it all more intuitive. Look at it this way: Even in this age of technology, of Google Maps, we still use street signs. Why? Because they catch your attention and are still pretty good at pointing you in the right direction. In the same way, simple, intuitive tools like the Crisis Flash Sheet uses brevity, size, and color to point you in the right direction as a crisis hits.

Historically, crisis communications started with the crisis plan in a binder or book—the most low-tech of all communications vehicles. Over the years, we introduced new iterations, including the Crisis Flash Sheet, CD-ROMs with templates, and sections of servers cordoned off for communications response. We then moved on to SharePoint and similar portals within the servers of companies.

What is the next frontier? I believe it is cloud-based technology that allows the crisis plan and materials to be available from any computer, tablet, smartphone, or other device. We’ll discuss this topic with more detail in Chapter 7, when we look at technology’s role in crisis response and specific tools that are intuitive and efficient in helping the crisis team come together and provide the right response to the right audiences at the right time.

Train

The final element of our A.C.T. system is training, the importance of which should be obvious. As in most things worth doing in life, if you haven’t practiced, you probably won’t execute well. Or put another way: if you haven’t cracked the books before being tested, don’t expect an “A” performance. And this is especially true in a crisis environment, where the action is fast and furious, and there’s a little time to learn as you go.

Now in truth, I could fill a whole book with the proper elements of designing training programs for crisis communications response, but for the purposes of Chief Crisis Officer, let’s just lay out some basic elements to consider as you look to train your core crisis communications team for effective implementation of the plan.

Most importantly, it is imperative that your crisis communications response training be a simulation, not simply classroom instruction. Too often in the corporate environment, crisis communications training becomes a seminar—perhaps with some case studies woven in, but a seminar nonetheless. As you look to plan and execute crisis simulation training, avoiding the “seminarization” of the exercise is key. Sure, there will be a review and an instructional component at the outset of any training, but keeping your simulations as close as possible to a real-life crisis experience can mean the difference between a training simulation that’s succeeds, and one that is, well … just another corporate meeting.

A few other points worth considering:

- Don’t be too clever by half. Yes, you want your crisis simulations to be as realistic as possible, but don’t sacrifice learning and then effort to simply put on a good show. I’ve heard of workplace violence simulations, for example, where during a presentation an armed gunman explodes into the seminar room and begin shooting at the presentee. Dramatic, yes; but I’m not sure how much at the end of the day that teaches the audience (and you’d better hope, I suppose, that no one in the audience is packing!).

- Get out of the conference room. Meetings are ubiquitous in Corporate America, of course, but there’s nothing that says you have to hold your crisis simulation in a conference room. In my experience, most crises don’t occur when you are sitting around in a room together. A simulation might take place in several locations, with some of your crisis team members at your offices, and others on the road. Anything to help simulate an actual crisis as it unfolds. Indeed, if you have incorporated crisis communications technology into your overall crisis response process, training programs can be created to manage simulated crises virtually—just as they would be handled in real life.

- Create a schedule of crisis training you can keep. Quarterly? Twice-yearly? Annually? It all depends on your organization. But I can give you two bits of advice: first, it must be often enough so that skills are developed and maintained, lessons learned and actionable results obtained on a continuing basis. In other words, if you have to spend the first half of the program reminding everyone why the hell you are there, you are probably not scheduling trainings often enough. Second, and this is, perhaps, contra to my first point: you should endeavor to create a training schedule you can keep. Nothing kills a training regimen more quickly than a schedule that, quite obviously, will never be kept.

In the end, the goal of any training program for crisis communications response is two-fold: first, if you want to get ready; and second, you want to learn—what works, what doesn’t, and why, so that you can fine-tune your crisis plan and the activity of the Chief Crisis Officer and his of her team for maximum efficiency and effectiveness.

After-Action Review and Crisis Communications Measurement

Finally, a key element of any crisis communications response plan is measuring the results of your efforts and preparing an after-action report to better understand what worked well and what didn’t in the heat of the battle. Indeed, this after-action assessment is one of the more important tasks to accomplish when a crisis abates (in addition to correctly maintaining all documents used for future reference), or in the wake of a training exercise. Your goal should be to gauge the success of your crisis communications plan, which allows you to make changes as needed to make the plan better and more effective going forward—which brings us full-circle, back to the assessment part of the A.C.T. system we learned about earlier in this chapter.

The key to this assessment is an understanding of what to measure during “after-action” analysis. The subject of measurement will differ depending on your organization, including how big you are, whether you are a for-profit business, nonprofit, or governmental agency and whether you are consumer-facing or operate in a business-to-business environment. Regardless, one rule applies: Measure the results and not the work product. For companies, this premise can be stated often as follows: Business goals are more important than communications goals. Let me explain.

Often in the public relations context, we look at things like the number of articles written on a topic or the number of media and social media impressions we’ve garnered as a means of measuring success. This is not to say the “hits” (as we say in the business) themselves aren’t important, just that they are the tool through which you achieve success in crisis communications (or in any communications endeavor) and not an end in themselves. If you are only measuring “press-by-the-pound” (or, in modern parlance, by the pixel), you are not getting a full view as to whether your crisis communications response had (or is having) the requisite impact.

To put it more practically, a single story in The New York Times on a particularly thorny regulatory crisis, with the right tone and message, one that influences key stakeholders in Washington, DC, may have more impact than 20 different pieces in Business Insider or the Huffington Post. If you only measure media impressions rather than their impact, in the case of The New York Times, you only have one story. If you focus on the tools you use to manage public perception during a crisis rather than the results of your management efforts, you will skew your measurement and as a result your entire after-action assessment.

For the same reason, it’s best to avoid what is known as “Advertising Value Equivalents” or A.V.E., which is the concept of using the value of advertising to determine the value of news stories that have been generated as a result of an organization’s communications efforts. PR companies usually love to throw these statistics at clients when putting together media clipping reports as a way to justify the value of the public relations retainer you are paying them—that is, “That story on CNN would have cost you $24,000 if you had paid for advertising during that time slot.”

Such comparisons tend to be wrong-headed in any circumstance,* but they are particularly bad during a crisis event. In a crisis, most of the stories written about the event and your organization’s response will be bad. Quite frankly, your concern should be how bad the coverage is and how much of the right message is getting in there to ensure that the crisis is eased rather than accelerated. This is nearly impossible to measure using an advertising equivalent. For example, consider how much airtime BP received in the wake of its 2010 oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico—that was billions in free advertising to be sure, just not the type of advertising any organization would want!

As such, focus on results, rather than tools. In this regard, I am reminded of this old aphorism: In home improvement, no one ever buys a drill bit because they want a drill bit. They buy a drill bit because they want a hole.

So what are these business goals? If you are a public company, you may decide that one week (or one month or one year) after a crisis, your stock price should be down by only a certain percentage (or, ideally, have recovered entirely). You may decide net sales staying flat rather than plummeting is an acceptable goal. If the crisis is severe enough, this could be considered a job well done.

As a reference, review the “Barcelona Declaration of Measurement Principles,” which was originally adopted by the public relations industry in 2010 and updated in September 2015.3 These principles start with the notion that, in all PR measurement practices, “the effect on organizational performance can and should be measured where possible.” Another key principle from that report: “Measuring communication outcomes is recommended, versus only measuring outputs.” In other words, it’s better to focus on areas like purchases, donations, membership loss, corporate reputation, and/or brand equity (both of which can be measured by appropriate surveys or other methods), rather than the work product of your public relations effort, such as news clips, social media mentions, and public utterances in response to a crisis.

Your organization may also have its own set of goals for different types of crises. For example, the goals for a facility fire may focus on revenue, whereas those for a product issue may concern brand equity. Your approach may also differ by region location and product line. The point is this: Find a business-related metric through which to measure success, identify it before a crisis occurs, then measure it after the crisis passes.

Now let me add that this focus on results rather than work product does not eliminate the measurement of direct communication goals where appropriate. For example, you may want a certain percentage of stories generated to include your message points, or you may decide to evaluate the tone of the stories as the crisis unfolds to assess the accuracy of facts over time or whether your message is, in fact, changing the media and social media coverage during a crisis. In addition, a post-crisis survey could ask the public what it understands about the crisis’ facts to see if your side of the story got through. However, you must ensure that all data is properly related to business goals.

To repeat, business goals should predominate your after-action assessment. After all, that’s why you have a crisis plan and engage in crisis communications in the first place. This plan does not serve as an end in itself, but rather ensures that the reputational damage inflicted by a crisis doesn’t permanently impact profits, practices, and organizational goals.

Action Points

- Many existing crisis communications plans are thick, bloated tomes that were created for reasons other than serving as effective tools for responding to crisis and other negative events that threaten the reputation, business, or goals of an organizations.

- Many large companies don’t have a crisis communications plan; of those companies that do have a plan, most find them inadequate.

- For effective crisis communications planning, you must “beat the bloat,” stripping away anything that is not absolutely essential in the crisis communications process.

- To create a crisis plan that is actually used, just A.C.T.: Assess, Create, and Train.

- The best crisis communications plans provide a roadmap for action, a way to bring the team together, and the tools and resources to give the entire team a starting point for effective communications response.

- The use of color and other visual identifiers can greatly enhance a crisis communications plan.

- Use tools like a Crisis Flash Sheet to ensure that basic crisis communications information is at your fingertips.

- The proper “after-action” assessment measures business goals rather than media impressions.

* SharePoint is a web application platform in the Microsoft Office server suite and has been a popular, if complicated, part of the corporate landscape for more than a decade. Launched in 2001, it combines various functions which are traditionally separate applications: intranet, extranet, content management, document management, enterprise social networking, enterprise search, business intelligence, workflow management, web content management, and an enterprise application store (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SharePoint). You’ll learn more about these sorts of software applications in Chapter 7.

* It’s not just PR firms that have a problem with bulk. Corporate executives suffer from this problem as well. They also must justify the cost of the tool they’re creating—what better way to justify such a cost than with a binder of a size that fits the price, especially when the higher-ups in the organization, who will approve the budget expenditure, will likely never have to use it.

* While e-book readers will see the Figures in this chapter in color, readers of the print edition of Chief Crisis Officer have to make due with black-and-white images. For full-color versions, visit www.prcg.com/chief-crisis-officer-color-images/.

* In this “mobile” age, corporate executives aren’t chained to their desk, cubicle, or office the way they used to be, and as such (as you’ll see in Chapter 7), we have been moving recently to cloud- and mobile-based systems that serve the same purpose. The reality of the current business world, though, is this: Most executives at corporations above a certain size still spend most of their time in their office, at their cubicle, or in front of their desktop PC—and when on the road, with laptop in tow.

† Again, print edition readers should visit www.prcg.com/chief-crisis-officer-color-images/ for the full experience.

* HIPAA is the acronym for the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act passed by Congress in 1996. The purpose of HIPAA includes providing for the ability to transfer and continue health insurance coverage when individuals change or lose their jobs, reducing healthcare fraud and abuse, and mandating standards for healthcare information. For the purpose of this discussion, HIPAA also requires certain protections and confidential handling of health information (see http://www.dhcs.ca.gov/formsandpubs/laws/hipaa/Pages/1.00WhatisHIPAA.aspx).

* Three quick reasons they don’t make sense in any form of PR measurement: (1) They don’t take into account the tone of the coverage, whether any competitive products are mentioned in the coverage, or whether the entire story dealt with the company or product in question; (2) they don’t take into account negotiated discounts on advertising—if you are buying that time on CNN, you’re likely not buying a single ad but have negotiated discounts for multiple placements; and (3) they don’t consider the impact of social media and the sharing of key stories.