Chapter

5

Sending the Right Message: Strategy, Words, and Actions

“Everyone thinks in terms of tactics … no one thinks in terms of message,” lamented the CEO of a company I was consulting with recently. He was in the midst of a crisis where everyone on his team was thinking about social media presence, cable news appearances, full-page newspaper ads, and posting a video message, but no one was thinking about what the hell to say.

Thus far in Chief Crisis Officer, we’ve examined the structure, systems, and leadership an organization needs for effective crisis communications response. Let us assume that you now have all of that in place. What’s your message?

In this chapter, we take a look at why the message itself is important when responding to various audiences during a crisis. We’ll show how a company’s ability to effectively minimize the negative reputational impacts of a crisis can be greatly affected by its ability to create a message that is compelling, straightforward, and—above all—succinct. Do it right, you will survive the crisis and perhaps even improve your reputation when the issue subsides. Do it wrong, you’ll bury your point, muddy the perception you want to create, and risk long-term reputational damage to your organization.

“What do you think of our statement?” I was asked.

“I think if your goal was to create something that ensures that no one will ever understand your company’s point of view … you’ve succeeded.”

Our prior chapters have been about structure, systems, and leadership. This is a chapter is about message—sending the right message to the right audience at the right time during a crisis or other high-profile, sensitive situation that threatens negative reputational consequences. We examine why, in the so-called information age, it’s sometimes hard to do well, particularly in the organizational context.

In the example above, it was clear that someone in the organization—probably a lawyer—drafted a statement quickly and without much thought as to its intended audience. It was dense, layered with legalese and industry jargon, and otherwise indecipherable. I had to read it three times to understand what the company was talking about … and I was deeply involved in the crisis already! Not a good sign if you are trying to put the public’s mind at ease regarding your company’s response.

Yet these were smart people, very smart. And they were all over this crisis early—the company had a plan in place, a strong leader in charge, and already established the proper structure for action. Why didn’t they make an effort to create a message that would be heard?

In this chapter, we’re going to look more closely at the roadblocks to creating effective messages in this information age and the preparation, tools, and perspective your Chief Crisis Officer and his or her team need in order to create messages during a crisis that change the game.

Can You Hear Me Now?

The goal of communicating is to be heard, but in a society built on knowledge, information, and technology, sometimes the complexity of the task at hand can become so stifling that we lose sight of … well, the task at hand. When asked to explain, we fall back on jargon, legalese, and other confusing rhetorical tripe—usually because we don’t have a clear idea of what we’re trying to say. As Albert Einstein is said to have remarked: “If you cannot explain an idea to a six-year-old, you probably don’t understand it well enough.”

Here’s just one example: Several years ago, I consulted on a project with a close colleague of mine from Washington. John is a fantastic public affairs professional—advising a wide range of companies and nonprofits on all manner of communications and public policy issues. In a few short years, his company has become one of the most respected in his region. But even though he’s in the communication business, at times his language is so laden with industry jargon that it prevents others from understanding him, undermining the impact of his excellent work.

Our client was one of the world’s largest companies, and John and I decided to discuss the project over coffee at a Starbucks near my office. I knew little about the project or what we were trying to achieve—only that it had something to do with media in the nation’s capital—so John was going to explain it to me. Unfortunately, after 15 minutes of conversation over latte and crumb cake, I was even more confused than when I’d arrived.

“John,” I finally interrupted, “What is the assignment?”

He thought for a moment, looking down at his notes. “The sense I get,” he said, carefully measuring his words, “is that we need to do an environmental scan, then blue-sky some recommendations on DC-functionality.”

I said, “John, I have no idea what you just said to me. I mean, I recognize all the words, but they just don’t mean anything in the order you’ve arranged them.”

The two of us just stared at each other in silence for a moment. Finally, I asked again: “What, John, exactly, are we supposed to be doing here?”

John looked dejected. He sank into his overstuffed easy chair, took a sip of coffee, and smiled at me. “That’s the problem,” he admitted. “I don’t know!”

Eventually we figured it out, of course, and John went on to create exactly the kind of research presentation the client was looking for. Yet it is a remarkable fact in this complex, knowledge-driven world that even the most expert communicators can get bogged-down in the type of bureaucratic, jargon-laden language that makes effective delivery of a message all but impossible.

These days we are all experts, hip-deep in the details of the various aspects of our jobs. Thus, when it comes time to communicate what is important about what we are doing, we often falter—primarily due to our inability to explain our work to those who aren’t as intimately acquainted with it.

In a business memoir written a number of years ago called Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance?,1 former IBM Chairman Louis Gerstner gave an excellent example of the way experts can “complexify” their messages. Gerstner was a brilliant communicator who credited much of his success at reviving IBM in the mid-1990s to his ability to cut through the corporate chatter that paralyzed one of the world’s premier companies. Indeed, much of his book describes his efforts to change the ingrained culture of an organization that was the expert in its field but had enormous difficulties communicating that expertise to its many audiences. The key, Gerstner found, was creating smart, sensible messages—statements that would convince IBM’s employees and customers, the financial markets, and others that IBM was still relevant in an era of web startups and open-source computing.

He accomplished this after discovering that complicated, bureaucratic language had tied IBM in knots. The jargon had become part of the culture (and beauracracy, it seems was rampant—the company’s organizational chart at that point was apparently five pages long!) Moreover, IBM managers struggled with communicating even the most basic messages. Soon after being appointed chairman of the struggling technology giant, Gerstner discovered that his managers relied on overhead transparencies called “foils” at every business meeting—the precursor to the ubiquitous PowerPoint deck so prevalent in corporate America today. Rather than discuss what needed to be done, executives instead dimmed the lights and worked through the stifling detail of a stack of complex foils.

Finally, Gerstner had enough. As one of his executives began shuffling his foils for a presentation, Gerstner switched off the overhead projector, telling the startled underling: “Let’s just talk about your business.”

So they did, and as Gerstner reports in his book, the executive turned out to be “the godfather of the technology that would end up saving the IBM mainframe” computer.

“We had a great meeting,” Gerstner wrote, adding that there was a “straight line” between that newly liberated presentation and this breakthrough for his company. If Gerstner hadn’t turned off the overhead projector that day, the critical decision to cut the price of one of IBM’s major products might have gotten buried beneath a pile of overhead slides.

The Message Paradox in the Information Age

I actually think this inability to create a succinct, compelling message—free of jargon, free of confusion—is one of the great paradoxes of our time: We live in a world awash in communication technology, where the ability to send messages across the street or around the world lies at our fingertips. Yet, in business, nonprofits, government, and our everyday lives, we have enormous difficulties being heard. Surveys have shown that the average American receives thousands of messages each day through a variety of mobile, email, computer, and other technologies. If you add in waves of mass media advertising and other messages, it’s easy to understand why, even as communication has become as easy as breathing, we’re all drowning beneath a sea of competing, yet often indistinguishable, messages.

This begs the question: With so many conflicting messages competing for our audiences’ attention, is it still possible to get your voice heard? This chapter will show you how to avoid common mistakes and create messages that resonate with your audience during a crisis and, how the Chief Crisis Officer and his or her team can overcome the inherent obstacles of modern communication to deliver effective, convincing, and winning messages that will make people listen and understand.

We’ll examine simple tools that can be utilized to create messages that rise above the clutter, complexity, and conflicting signals of the information age. Across a spectrum of business, professional, and even social situations, we’ll examine concrete examples of effective message creation that serve as the core of great communication.

A Modern Problem for the Modern Age

We all send messages virtually all of the time—whenever we pick up a pen; hold a conversation; type an email message; give a speech; post to Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or Snapchat; address our employees or colleagues; answer questions from the media; or set out to market our products and services. Yet, most of us are far better at generating messages than we are at crafting them. I see the results of this imbalance every day in crisis communications. In an age rife with technology, specialization, and expertise, we forget the basic elements that lie at the heart of communication—the words and images that form the foundation of an effective message.

Indeed, an amazing byproduct of the ease with which we can send messages in this modern era is the following: Everyone pays lip service to the fact that the right message is vitally important to the overall success of the communication objective they are trying to achieve, but no one wants to work to get it done. In my view, it is the simplicity of modern communication itself that has fostered this laziness.

Yet some professionals and organizations are getting it right in highly charged, stressful, bet-the-company-style situations. They are the true leaders in responding to difficult situations—whether it be in business, politics and government, nonprofits, or the professions. If you look behind the success of these crisis responders, inevitably you’ll find considerable attention to the creation of effective messages—usually well in advance of the onset of the actual crisis event. They know it matters.

Even in this era of limited attention spans and a multitude of media and social media exposures, the problem is not just that there are too many messages. Based on our research and experience, we’ve uncovered four basic reasons why we are losing our ability to communicate effectively in a crisis to those we wish to inform, instruct, and influence, and why this is such an intrinsically modern problem:

- In a world of vast technological advances, we have become so enamored with the logistics of communication (i.e., the Facebook page and Twitter post, the YouTube video, the “dark” webpage, or direct communications via text message or other means) that we’ve forgotten about substance—the message that forms the foundation of proper communication.

- In a world where words are cheap and easy to create, they’ve lost all value as a currency of communication.

- As we’ve seen, in a world of information, we are all experts, knee-deep in the complexities of our particular discipline and unable to effectively communicate our message to those who don’t wade in similar streams.

- In a world that is stunning for its complexity and nuance, there is constant pressure on all of us to equivocate, to footnote, to qualify, rather than just stating what we mean, clearly and succinctly, to the appropriate audience in a manner they can truly understand.

Throughout this chapter, we’ll look at companies that have fallen into these traps during a corporate crisis and consider ways to overcome the obstacles to give you a true understanding of what’s preventing your message from being heard. In the midst of a crisis or other negative reputational event, this will allow you to rise above the competing voices and information static of our modern business and social lives, so that you can deliver a message to all audiences and stakeholders during your crisis that resonates—whether through media, social media, or direct or electronic communication with customers, vendors, investors, employees, or other stakeholders in your organization’s success.

Saving the Words for Last

Too often, like the Target executives we met in Chapter 4, we focus on every element except the proper message when attempting to communicate with the outside world. We exquisitely plan the medium of message delivery while leaving the actual message behind. The result is a message that is muddled, vague, or just plain uninteresting to the audiences we are trying to reach.

Marshall McLuhan famously declared: “The medium is the message.” For me, though, during a crisis, the message is the message, first and foremost. Hit the right tone, you are effectively managing the message; hit the wrong tone, your crisis will start spinning out of control.

This is why, in prior chapters of this book, I’ve harped on the necessity to have a “core” message prepared early, which can then be “tailored” to whatever audience and medium you are using to communicate. Ideally, as you are preparing your company’s crisis plan (as we discussed in Chapter 3), you are also carefully laying out the various scenarios that may confront your company and creating templates that can be used as the starting point for creating effective messages. Further along in this chapter, we will examine exactly how this is done, using actual templates from my firm’s crisis communications software portal.

Why It’s Important

No matter who you are, communicating your message effectively can mean the difference between success and failure. A bad message can take a situation that is just beginning to brew, a crisis-in-the-making that is not yet a full-blown crisis event, and turn it into one quickly and completely.

For example, we were involved in communications counseling with a client many years ago. Our strategy was thus: don’t mince words, state your case clearly, back it up with a few simple facts, and believe in what you say. We also counseled the client to avoid falling into “ostrich syndrome,” where we pretend a crisis isn’t gaining steam and hope it all goes away.

This client in question, a large multi-national based on the West Coast, knew our approach, our advice, and our skills. Despite this knowledge, as the crisis grew, the chairman of the company decided our approach wouldn’t work in the current situation, that sharp message should be avoided, and that the company was better off “gumming up the works” (as their PR director put it). The company hoped that by being obtuse the issue would seem less interesting to the media, then maybe the whole crisis would go away.

Just after rendering our advice, I received an email back from the PR director:

Hi Jim,

Just want to let you know that the Chairman and the CEO have decided that they’ll be handling this one personally going forward.

“… personally going forward?” What the hell did that mean? They didn’t have a deep PR staff for this type of work, and they sure didn’t have the skills needed to make the right kind of statements in this particular situation.

I asked exactly these questions, figuring my powers of persuasion would convince the organization that they were making a mistake. I must have been having a bad day, because I received this response:

Yeah, the thing is the Chairman and the CEO feel that the lower the profile they take in this, the better the result is going to be. So they’re going to keep their response pretty bland for now. They’d like you to stand down at the moment. They’ll activate you as an asset should the time come.

Part of me was flattered, I suppose, to be considered an “asset” that could be activated if need be, like a CIA agent from Showtime’s Homeland. But “bland” was going to win the day? Based on nearly a quarter century of doing this work, I can tell you that “bland” rarely works when confronting a negative reputational situation.

To flesh out the whole picture, let me tell you more about this particular crisis. This wasn’t the type of crisis that would go away quickly. It was a burgeoning scandal involving insider trading. Not only that, the insider trading involved two very prominent figures—among the best known in their particular field.

Needless to say, bland didn’t work. The company’s response to the first Bloomberg News inquiry regarding the insider trading issue was so full of holes that it left more questions than it answered. This led to a second inquiry from the Los Angeles Times, which led to a third inquiry from a major newsweekly, and so on.

Finally, two weeks later, I got another email from the head of PR for the client:

Hi Jim,

Just to keep this interesting I want to pose a question: If we were to tell our story in a more robust manner, what would that story be? If we wanted to present our side of the story to put us in a positive light and correct all the wrong information, what would that look like?

I asked the CEO this morning and he said, “Write it up”. Can we draft what this could look like, where we would place it, how we could execute, etc.”

Thanks,

Wow. I guess “bland” didn’t work. In response, I explained to the PR head that they’d dug themselves such a hole trying to fly below the radar that a simple “story” would not work; they needed an all-out, full-court press to turn this thing around. After two weeks of negative media coverage, it was going to take time to begin cementing a new set of messages in the public’s mind.

Message versus “On Message”

A disclaimer: You’ll often hear PR consultants talk about the importance of repetition, of “message discipline,” and of choosing the proper message and sticking with it. This is important, of course, but this chapter is not about “Staying on Message”—that contemporary cliché of the political and intellectual elite, often expressed as follows:

Q: How’d the meeting [conversation, sales call, media interview] go?

A: Very well! I really was “on message”!

Congratulations, I say. What was the message? Did it resonate with your audience? Was it concise, compelling, and substantive? Or was it obtuse, qualified, and filled with industrial jargon and bureaucratic doubletalk? Did it only provide half the information needed for a response, leaving the media and the public with a slew of follow-up questions?

In other words, it doesn’t matter how “on-message” you are if your message is crap.

To effectively communicate your desired message to your target audience, these questions regarding the content of your message are as important as being “on message.” In other words, content over delivery.

So heed this rule:

The right message delivered once is always more effective than the wrong message delivered over and over again.

This is true regardless of your skills in “message discipline” and your ability to stay on message, and it in large part runs contra to much of the conventional thinking—particularly for those who come out of a political arena.

Indeed, the clichéd, conventional wisdom regarding staying “on message” can spell doom for almost anyone dealing with a crisis unless they have the right message behind them. More often than not, a communicator forcing “on message” responses with a bad message comes off as a blow-dried, robotic parrot rather than a compelling, caring individual with a story to tell.

In a way, politics has ruined this understanding—we are exposed to “staying on message” in its worst forms. Consider presidential debates (putting aside the most recent presidential debates in the 2016 election, which—with their vitriol and name-calling were—it is hoped—an anomaly): The moderator asks a question about healthcare, and they get an answer about education or national defense. The audience groans ever so perceptibly, and we all wonder why the moderator doesn’t hop in and say: “Well, wait a minute, I didn’t ask you about education, I asked you about healthcare!”

This is not what we’re talking about; for some reason, we accept this contrived silliness from our political candidates. Rest assured, if you try it this way in a “real life” crisis, you’ll fail.

Relentless adherence to the “on message” Kool-Aid is the best way to damage your credibility and the effectiveness of your communication. You come off as shallow, forced and rehearsed. In other words, the message is all style and no substance; all sizzle, no steak. This message will ultimately fail—and with it (usually, anyway) the leader trying to communicate the message.

Infamy

Now I’m going to give you a history lesson.

Specifically, I want to contrast the ideas above with famous messages from a bygone era, spoken during times of crisis, which demonstrate the different ways we construct messages in this modern age, and the point where, perhaps, the battle for resonance is lost.

First, let’s consider what might be the most effective communication of the 20th century: President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s speech to Congress and the American people in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

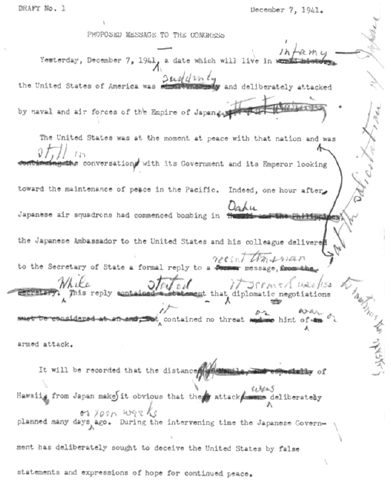

Even those whose knowledge of American history is weak are likely familiar with the opening of Roosevelt’s speech: “Yesterday, December 7, 1941—a date which will live in infamy—the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.”

In Roosevelt’s speech, the word infamy anchors the entire first sentence. Academic researchers have told me that the word “infamy” is so connected with that famous line that it rarely is used in other contexts today. To give you an idea of exactly how strong the word “infamy” was in that context, consider this: Although Roosevelt’s speech is likely the most famous made by an American in the 20th century, many don’t remember the second half of the sentence—everything that comes after that pivotal word “infamy.”

Even more interesting is the fact that the word “infamy” almost wasn’t used in that famous utterance.

A remarkable document exists in the FDR Museum in Hyde Park, New York—the original, typed first draft of Roosevelt’s Day of Infamy speech. It has Roosevelt’s handwritten notes. As Figure 5.1 shows, the original draft of the opening sentence to his famous speech, which read as follows: “Today, December 7, 1941, a date which will live in world history, the United States of America was simultaneously attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.”

Roosevelt had the foresight to alter two key words. He replaced “world history” with “infamy” and “simultaneously” with “suddenly and deliberately.” This is more than mere wordsmithing. These are the edits of a man with a keen instinct for language that resonates with his audience and carries weight.

“Infamy” is a word with substance and baggage that brings forth all kinds of emotional responses. It makes us think of treachery, deceit, and the ignoble nature of the attack.

“World history,” by contrast, is a dry pair of words, an academic phrase. It makes no value judgment. It is a “just-the-facts-ma’am” construction.

Similarly, “simultaneously” might have been accurate, but like “world history,” the word is dry. It merely describes the coordinated nature of the attack. By contrast, “suddenly and deliberately” are action words—words that give voice to the unexpected nature of the attack, the intentionality, and the sneakiness.

Figure 5.1: A draft of Roosevelt’s Day of Infamy speech

Suddenly! Deliberately! Infamy! These were no reckless substitutions—they were clearly designed to create a message that more fully resonated with outrage, shock, and disgust. They did just that.

If Roosevelt had not made those fateful edits that afternoon, we might not even remember his speech—any more than we remember Woodrow Wilson’s speech after the sinking of the Lusitania, an event that helped lead the United States into World War I. Although more than 2,400 Americans died on December 7, 1941, the date (not the event itself) might have faded from memory. Instead, we just commemorated the 75th anniversary of that event, and December 7, 1941, has become far more than just another day in world history. And Roosevelt is remembered as one of the greatest orators of his day.

Roosevelt clearly understood the value of choosing the perfect words for the right message; he knew that this was the foundation of effectively communicating with his target audience. How did he know? Why did Roosevelt value words so highly in a way our current political leaders rarely do? Was he a more gifted writer? There’s nothing in the record to indicate that Roosevelt was more or less gifted than politicians today. But clearly he had a way with words: He also coined the famous phrase, “We have nothing to fear but fear itself,” to inspire a nation suffering through the early years of the Great Depression. But his skill in crafting speeches doesn’t explain the power his words still hold for modern readers, which begs the question: What other factors served him as he created such memorable messages?

Here’s my theory: In the past, the process of creating messages was hard. Words were scarce; therefore, they had value. Take another look at the draft of Roosevelt’s “Day of Infamy” speech. Note the typewritten paper with handwritten edits scrawled in pencil—even the process of getting these words on paper was hard.

To get his speech into the form you see in Figure 5.1, Roosevelt had to dictate the message to his assistant, Missy LeHand. He then sat at his desk for more than an hour working at other things, but also pondering the important message he just dictated and putting critical distance between himself and his words. His assistant then brought back the typewritten text. Roosevelt looked at his words again, considered them closely, and made the fateful changes that turned that draft into a history-changing message. The draft went back to his assistant, who made the changes, and the president considered it again before putting it in final form. This hard work led to an appreciation of the content of the message itself and the individual words that were the foundation of that message. In other words, it was the studied nature of the process itself that made this message what it was.

Compare this to the way we create messages today: Type, type, type, type, type, type, type, type … send!

The message is then sent immediately via email, Facebook post, Twitter, website, or other media commonplace to our modern existence. From the time the message leaves our minds and becomes words on our computer screen to the time it arrives at its final destination, we never think about that message again. We never reflect on it, asking ourselves:

- Is this communication accomplishing what it set out to achieve?

- Am I capturing the attention of my audience in the proper manner? In a way that considers who the audience is and exactly how much time I have to get my message across?

- Are the words I chose—in each sentence, on each line—exactly the words that will effectively communicate the message to the target audience?

As such, it is no surprise that our message, orphaned from moment of conception, falls flat or gets ignored entirely when it arrives at its destination—an inbox or social media feed that already contains hundreds of other messages, be they words, memes, emoticons, or gifs. This problem has nothing to do with your intelligence, and probably little to do with your ability as a communicator. The problem is the process by which the words are put together.

Even 20 or 30 years ago, communication was harder than it is today, and words were more valuable. Consider another critical crisis communication of the 20th century: Ronald Reagan’s speech to the American people on the night of the Challenger disaster in 1986. Addressing the families of the Challenger astronauts, Reagan said:

Your loved ones were daring and brave and they had that special grace, that special spirit that says, “Give me a challenge and I’ll meet it with joy.” The future doesn’t belong to the fainthearted. It belongs to the brave. The Challenger crew was pulling us into the future, and we will continue to follow them.

He ended with the now famous line, quoting from a sonnet by John Gillespie Magee, a young airman who was killed in World War II: “We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them this morning as they prepared for their journey and waved goodbye and ‘slipped the surly bonds of earth’ to ‘touch the face of God.’”

Thirty years later, I can still remember those words, still hear Reagan’s voice, and still see the president delivering that speech and, in television footage, the astronauts waving goodbye as they entered the Space Shuttle’s cockpit.

Here’s my point: These communications were effective not because they were easy but specifically because they were hard. The words were labored over; the process of creating them was more difficult than it is today, when anyone with a smartphone can broadcast a message over Twitter or Facebook. It is the difference between a handcrafted Sam Maloof rocker and one you might pick up outside of Cracker Barrel. When the ability to communicate was scarce, more value was placed on words as a commodity. Words were crafted with care, and the result was messages that resonate more effectively with target audiences.

I’ll give you two more examples to further make this point. The first involves one of the greatest orators of the 20th century, Winston Churchill. Surely, there was no one more natural than he?

Remarkably, although Churchill often seemed extemporaneous and unrehearsed, this façade was the product of extensive preparation. “In Parliament,” Churchill biographer William Manchester wrote, “his wit will flash and sting, but members who know him are aware that he has honed these barbs in advance, and only visitors in the Stranger’s Gallery are under the impression that his great perorations are extemporaneous.”2 On average, for a 40-minute Parliamentary speech, Churchill spent six to eight hours in preparation.

Churchill was so interested in giving the impression of spontaneity that he prepared exhaustively for it. During a speech to Parliament, he would hold in his hand not notes but the entire text of what he was going to say, including stage direction (“pause; grope for word” or “stammer; correct self”).3

Fast-forward a half century later and consider the example of Steve Jobs. He was also considered a great orator, a man who many claimed could create a “reality distortion field” that convinced himself and others around him, with mix of charm, charisma, bravado, hyperbole, and persistence, that almost anything was possible.

A true natural, right? Surely he didn’t have to work hard to achieve his messaging goals?

Consider this passage from the 2015 book Becoming Steve Jobs, by Brent Schlender & Rick Tetzeli:

Working with a team of marketers and PR execs, Steve would rehearse endlessly and fastidiously. Bill Gates made appearances at a couple of these events, and remembers being backstage with Steve. “I was never in his league,” he remembers, talking about Steve’s presentations. “I mean, it was just amazing to see how precisely he would rehearse. And if he’s about to go onstage, and his support people don’t have the things right, you know, he is really, really tough on them. He’s even a bit nervous because it’s a big performance. But then he’s on, and it’s quite an amazing thing.

“I mean, his whole thing of knowing exactly what he’s going to say, but up on stage saying it in such a way that he is trying to make you think he’s thinking it up right then …” Gates just laughs.4

Churchillian, right? Here’s my point: Those who are creating great messages, be it for a crisis situation or any other critical communications situation, are working damn hard to make sure they get the message right.

This is not a mere history lesson or philosophical debate. I want everyone to understand the real issue we have in this modern world, one that comes up time and time again when responding during a crisis. Leaders from the past weren’t born better at communication. They worked hard at this part of their professional lives to communicate effectively.

Working equally as hard when planning and responding in a crisis or other sensitive situation is just as important.

What Crisis Communications Messages Should Do

“But Jim,” you ask, “you’ve already stated that, in the heat of a crisis, time is the most critical factor in ensuring proper response. That’s why we’re appointing a Chief Crisis Officer and a core crisis communications team, after all—so that they can move quickly in the initial stages of a crisis to ensure the event is managed properly. Now you’re telling me to take a deep breath, pull out the manual typewriter or Dictaphone, like FDR or Winston Churchill, and carefully hew every message. That’s impractical!”

Indeed, it is, but this is exactly why you have a Chief Crisis Officer and team dedicated to crisis communications response in the first place, and why you created a crisis plan that anticipates a variety of potential crises. As we learned in Chapter 3, you want the playbook down and your messages largely written before you get into a crisis. Ideally, like Churchill, you’ve chosen these words carefully—you just laid the framework for those words before you needed them. The effect is the same.

The alternative, as we learned in the previous chapter, is to have nothing ready, have no plan, and start “making it up as you go along.” As we’ve seen with BP and Target, this tends to result in messages that are weak and confusing, doing little to express an understanding of:

- The gravity of the problem;

- What the public is going through;

- How this could have happened;

- What the company is doing to respond; and

- How the company is going to take steps to make sure this doesn’t happen again.

In the BP case, you’ll recall, it took three days to express any of these sentiments at all. As we learned in our last chapter, the statements were all designed to shift the blame to Transocean—the operator of the well. Indeed, contrast the message issued just after the event:

BP today offered its full support to drilling contractor Transocean Ltd. and its employees after fire caused Transocean’s semisubmersible drilling rig Deepwater Horizon to be evacuated overnight, saying it stood ready to assist in any way in responding to the incident.

Group Chief Executive Tony Hayward said: “Our concern and thoughts are with the rig personnel and their families. We are also very focused on providing every possible assistance in the effort to deal with the consequences of the incident.”

with the statement issued two days later, after the public frenzy over the incident had already reached critical mass:

BP today offered its deepest sympathy and condolences to the families, friends and colleagues of those who have been lost following the fire on the Deepwater Horizon oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico this week.

Group Chief Executive Tony Hayward said: “We owe a lot to everyone who works on offshore facilities around the world and no words can express the sorrow and pain when such a tragic incident happens.

Note the clichéd, detached language in the first statement (“… our concerns and thoughts are with …”) and contrast that with the statement made several days later (“… no words can express the sorrow and pain when such a tragic incident happens …”).

As we discussed, this is not the only reason why BP had such trouble responding in the initial phases of the crisis, but it certainly didn’t help. If they had thought fully and carefully prepared some language for this type of incident before it happened (since it was clearly foreseeable), they might not have fallen back on initial statements that clearly did little to reassure the public that BP cared about what was happening.

Volkswagen’s Weak Statements in the Initial Phases of Its Emission Scandal

Consider another one of the largest crises to erupt over the past several years: The Volkswagen AG vehicle emissions scandal, which leapt onto the front pages in 2015. Volkswagen’s handling of reports of falsified emissions data over the course of half a decade quickly became one of the biggest crisis communications stories in recent years.

The background: On Friday, Sept. 18, 2015, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) accused Volkswagen of cheating by installing software in 500,000 diesel cars that allowed the vehicles to show low emissions of nitrogen oxides when tested. When these cars were actually on the road, they spewed as much as 40 times the U.S. legal limit.5

The software was installed in cars starting in 2009, and the company knew about potential issues for three years before the news broke. Volkswagen, in discussions with regulators, apparently chalked up the disparity between laboratory and road to technical glitches.6

Indeed, a fascinating element of the Volkswagen story is often overlooked: Researchers at the University West Virginia started testing Volkswagen vehicles in 2012. West Virginia regulators and the federal EPA knew about these tests (which were public knowledge) in 2013, and began their own investigations shortly thereafter. Yet, the company was completely flat-footed when it came to crisis communications response.7

In response to the EPA’s announcement, Volkswagen issued a statement that is another prime example of weakness in messaging:

VOLKSWAGEN STATEMENT REGARDING EPA INVESTIGATION

September 19, 2015—Volkswagen Group of America, Inc., Volkswagen AG and Audi AG received today notice from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Department of Justice and the California Air Resources Board of an investigation related to certain emissions compliance matters. As environmental protection and sustainability are among Volkswagen’s strategic corporate objectives, the company takes this matter very seriously and is cooperating with the investigation.

Volkswagen is committed to fixing this issue as soon as possible. We want to assure customers and owners of these models that their automobiles are safe to drive, and we are working to develop a remedy that meets emissions standards and satisfies our loyal and valued customers. Owners of these vehicles do not need to take any action at this time.8

Volkswagen’s response is a masterwork of cold, confusing, detached corporate speak. It is no wonder the story only began to grow as the crisis took off.

Indeed, you see this “bad statement/better statement” dynamic over and over again in each one of the crisis communications examples we cover. Like BP and Target before it, Volkswagen issued a new statement several days later, taking a more “human” approach to the crisis. This time, the statement came directly from Volkswagen’s CEO, Dr. Martin Winterkorn, and addressed some of the key elements of an appropriate crisis communications message that we outlined above:

I personally am deeply sorry that we have broken the trust of our customers and the public. We will cooperate fully with the responsible agencies, with transparency and urgency, to clearly, openly, and completely establish all of the facts of this case. Volkswagen has ordered an external investigation of this matter. We do not and will not tolerate violations of any kind of our internal rules or of the law.

The trust of our customers and the public is and continues to be our most important asset. We at Volkswagen will do everything that must be done in order to re-establish the trust that so many people have placed in us, and we will do everything necessary in order to reverse the damage this has caused. This matter has first priority for me, personally, and for our entire Board of Management.9

Five days later, Winterkorn resigned.

In fact, Volkswagen’s crisis communications miscues throughout its emissions scandal (which is still ongoing as of this writing) are almost too numerous to mention. One prime example revolved around the December 2015 release of the preliminary findings of an internal inquiry by the chairman of the company, which stated without equivocation that the cheating scandal was not a one-time error, that it was deliberate, and that the decision by employees to cheat on emissions tests and lie about the results was made more than a decade ago. However, just a month later, during an interview with National Public Radio (NPR) at the North American International Auto Show in Detroit, the Volkswagen’s new CEO, Matthias Müller, stated that the company “didn’t lie” to American regulators before the scandal came to light, instead chalking up the failed tests to a technical problem. After the segment aired, Mr. Müller called NPR to do another interview and retract this comment.

Again, Volkswagen knew this scandal was coming for two years—plenty of time to get your ducks in a row, message-wise. Yet, as is the case with so many major corporations, they did nothing and wound up with bland, cold corporate emissions (if you’ll pardon the pun) that did little to reassure a questioning public, and in fact, raised as many questions as they answered.

Wal-Mart in Mexico

Or consider a different crisis response, one that—while full of tactics (and words)—was missing a coherent message and strategy as well: Wal-Mart’s slow and ineffective reaction to 2012 Mexican bribery allegations against the company.

Indeed this case has a twist at the end that reinforces everything we’ve been learning about in Chief Crisis Officer.

In April 2012, published reports alleged that Wal-Mart was involved in a brazen pattern of bribery in Mexico, with the goal of reaching “market dominance” in that country. The first news report, detailed in a page one story in The New York Times, stated that when confronted with evidence of this bribery campaign and a recommendation to expand an internal investigation, “Wal-Mart’s leaders shut it down.”10 The initial Times story dominated legal and business news for more than a week, with each day bringing new allegations, information, and analysis. This reporting eventually won the Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting.

After the story broke, Wal-Mart began feeling pain not only to their reputation but financially as well, in ways that far outstripped the actual potential liability. The company’s shares were hammered: At one point, Wal-Mart stock was down more than 8 percent in two days. To put this drop in context: According to Reuters, those two days of losses wiped out more than $10 billion in market value. In the meantime, there was a 12 percent loss in shares of “Wal-Mart de Mexico,” a separate company stock that trades on Mexico’s IPC index.11

Indeed, the damage to their reputation and finances appears to have been far greater than any punishment contemplated under the worst cases of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), which bars U.S. companies from paying bribes overseas. Consider this analysis from The Wall Street Journal:

“In the U.S., legal experts said Wal-Mart could face years of stepped-up regulatory scrutiny, hundreds of millions of dollars in fines, and the appointment of an outside monitor to oversee compliance with foreign bribery laws, if the Department of Justice determines the bribery allegations are true.”12

This is tough stuff, but by no means in the $10 billion range, which highlights the importance of a crisis communications response. As in the examples of BP, Target, Volkswagen, and other companies, an effective response just wasn’t there.

In the wake of the initial revelations, Wal-Mart issued a long and incredibly defensive statement:

We take compliance with the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) very seriously and are committed to having a strong and effective global anti-corruption program in every country in which we operate.

We will not tolerate noncompliance with FCPA anywhere or at any level of the company.

Many of the alleged activities in The New York Times article are more than six years old. If these allegations are true, it is not a reflection of who we are or what we stand for. We are deeply concerned by these allegations and are working aggressively to determine what happened.

In the fall of last year, the Company, through the Audit Committee of the Board of Directors, began an extensive investigation related to compliance with the FCPA. That investigation is being conducted by outside legal counsel and forensic accountants, who are experts in FCPA compliance, and they are reporting regularly to the Audit Committee.

We have met voluntarily with the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to self-disclose the ongoing investigation on this matter. We also filed a 10-Q in December to inform our shareholders of the investigation. The Company’s outside advisors have and will continue to meet with the DOJ and SEC to report on the progress of the investigation.

We are committed to getting to the bottom of this matter. The audit committee and the outside advisors have at their disposal all the resources they may need to pursue a comprehensive and thorough investigation.

We have taken a number of actions in Mexico to establish stronger FCPA compliance.

We have implemented enhanced FCPA compliance measures including:

- Robust policies and procedures;

- Internal controls;

- Training;

- Enhanced auditing procedures; and

- Issue escalation and remediation protocols.

In addition, we have established a dedicated FCPA compliance director in Mexico that reports directly to our Home Office in Bentonville.

The investigation is ongoing and we don’t have a full explanation of what happened. It would be inappropriate for us to comment further on the specific allegations until we have finished the investigation.

We are working hard to understand what occurred in Bentonville more than six years ago and are committed to conducting a complete investigation before forming conclusions.

We don’t want to speculate or weave stories from incomplete inquiries and limited recollections, as others might do.

Unfortunately, we realize that, at this point, there are some unanswered questions. We wish we could say more but we will not jeopardize the integrity of the investigation.

We are confident we are conducting a comprehensive investigation and if violations of our policies occurred here, we will take appropriate action.

Over the last several years, Walmart has focused diligently on FCPA compliance and implemented a series of changes to our FCPA compliance program to further strengthen them. This work is ongoing and continues today.

As part of that effort, in the spring of 2011, we initiated a worldwide review of our anti-corruption program. We are taking a deep look at our policies and procedures in every country in which we operate. This includes developing and implementing recommendations for FCPA training, anti-corruption safeguards, and internal controls.

Acting with integrity is the essence of our corporate culture. We have the same high standards of integrity for every associate—regardless of his or her position—and everyone is held accountable for those standards.

In a large global enterprise such as Walmart, sometimes issues arise despite our best efforts and intentions. When they do, we take them seriously and act as quickly as possible to understand what happened. We take action and work to implement changes so the issue doesn’t happen again. That’s what we’re doing today.

Walmart is committed to doing the right thing and we are working hard every day to become an even better company.13

Wow—this statement is 630 words long. Wal-Mart also posted a video on their corporate website that refuted the charges and announced the creation of a new global compliance officer position that will oversee five regional compliance directors. The company said it would add “new protocols” to make sure FCPA investigations are managed “consistently and independently.”

As you already know, the number one rule in responding to a crisis such as this one is: Be Prepared. In the message context, preparation is important when putting together statements, press releases, message points, and other documents that will help you convey proper information to the public in a timely manner, explain your company’s position, or express the appropriate compassion or concern over injuries or other negative consequences. As we’ve seen, a tendency exists among corporations to respond in a muted manner to these crises in the hopes of downplaying the media coverage and minimizing its impact. Perhaps this works sometimes, but in Wal-Mart’s case, the original reporting by The New York Times had obviously been under way for quite some time; Wal-Mart knew about it, and it was clearly going to be big news. This is especially the case considering the executives who were implicated (including the company’s current and former CEO), as well as the detail and depth of the evidence presented (indeed, the article included actual links to memos and emails concerning the alleged bribery.) There was no way this crisis was going to go quietly.

And although I have no direct link into the minds and hearts of the Wal-Mart executives handling the matter at the time, I suspect “ignore and hope it goes away” was central to the initial game plan (followed, it would seem, by “panic and issue a long, ineffective statement”). In any case, the parallels to the other major crises we’ve discussed in this book is stunning. Consider this: After issuing a statement when the article was posted on The New York Times website on Saturday night, Wal-Mart felt the need to issue an “Updated Wal-Mart Statement” Tuesday morning, detailing the actions it was taking in more concrete terms. As we’ve seen, whenever a company has to issue a second press release a day later—not to update the public on latest developments but rather to explain the first—it’s a pretty clear sign they weren’t ready.

A second piece of evidence highlighting the slap-dash nature of the response: Although (as noted above) a senior corporate compliance position was created, no one was appointed to the post. Yet, according to the Times article, Wal-Mart knew about the investigation for at least six months. Again, I am speculating, but it is not unreasonable to suspect that this corporate compliance idea was hatched after the company and its advisors realized the crisis wasn’t going to blow over.

What could Wal-Mart have done differently? Well, they had months to get their story straight and prepare proper messages to respond when the story inevitably hit the pages of The New York Times. If properly prepared, these messages wouldn’t have read like a lawyer’s screed (as above) and would have succinctly and compellingly communicated what is buried in that 630-word tome—that these are complicated matters, Wal-Mart is investigating the issue thoroughly (working closely with authorities), and the company doesn’t tolerate bribery of any kind.

Personally—and now I’m getting very tactical—I wouldn’t have let The New York Times get the first bite of the apple if I saw a negative story about my company’s businesses’ practices in the works. I might have considered getting the story out on the right terms, in the right context, and in a “friendlier” media outlet—acknowledging mistakes where appropriate and providing a complete description of the steps being taken to ensure a zero-tolerance policy for such practices—long before The New York Times could sink their teeth into the story. From my experience working on these sorts of stories, Wal-Mart should have known that the Times story was headed in a negative direction—the company (according to their statement) had been working with regulators on investigating these issues for months. I’d have advised Wal-Mart to get ahead of the story to frame it properly in the public’s mind long before the Times piece went to press.

In addition, I would have had the right person in mind for that corporate compliance post: a “new sheriff in town” with a reputation that reassures the public, the financial community, and the media that there is a real commitment to change. I may have advised Wal-Mart to use this opportunity to start a real debate over the FCPA, its many “gray” areas, and whether the statute handcuffs corporations trying to compete globally. Although no one condones bribery, real issues exist that should be aired publicly as the United States rebuilds its economic muscle. Engendering such a debate in advance of the Times story might have put the allegations into the proper context.

I am Monday-morning quarterbacking, I know, but I think these very simple strategic and messaging practices are sometimes lost unless a company has prepared for them.

An interesting postscript exists to this Wal-Mart story. In October 2015, The Wall Street Journal published a story that indicated that more than three years after the initial allegations surfaced in The New York Times, “a high-level federal probe” of the allegations found “little in the way of major offenses, and is likely to result in a much smaller case than investigators first expected, according to people familiar with the probe.”14 While the investigation wasn’t over, The Wall Street Journal story revealed that it was likely that the case might be resolved with just a fine and no criminal charges against any Wal-Mart executives. So, the initial stunning revelations in the pages of The New York Times may have had far less truth to them than had been realized at the time.

So—in another bout of Monday-morning quarterbacking—this suggests that the lack of crisis communications preparation, including getting the right messages together to combat what may have been a grossly exaggerated story, cost the nation’s largest retailer more than $10 billion in market value, despite the apparent lack of fire to accompany the initial smoke.

Formulating Template Messages in the Crisis Plan

Hopefully, I’ve convinced you that if you have a strategy and the proper crisis communications plan in place (using the procedures we outlined in Chapter 3), you can avoid some of the pitfalls that we’ve looked at in this chapter and ensure you are creating messages that resonate with the proper public audiences in a manner that doesn’t allow your crisis to spin out of control. But can you realistically anticipate every possible crisis scenario that might possibly face your company, and create template messages beforehand to respond?

Of course not. You cannot anticipate everything, but you don’t have to. You only have to prepare scenarios for the most common crises your organization might face. It’s really not that hard either—10, 20, 30, or whatever the number might be for your particular size, industry, and risk profile. If you’re Wal-Mart, you might have more; a small Mom-and-Pop retailer with less than a dozen locations will have less. My point is that the Chief Crisis Officer and his or her team should have thought long and hard about these crisis scenarios and the messages that would work under a variety of circumstances well before the accident occurs, the data breach is discovered, or The New York Times investigative reporter calls.

Moreover, if your crisis plan is a “living document,” you are constantly updating your templates for various crisis scenarios based on what works and what doesn’t, as well as new potential crises that weren’t on your radar when the crisis plan was first created.

I know there are skeptics out there: “Sorry, no, there’s no way. Our business is just too big, too complex, the issues we face too often sui generis. It wouldn’t work for us.”

Respectfully, you are wrong. Just as BP could have anticipated an oil leak in the Gulf of Mexico, Target a credit card data breach, and Volkswagen rigged test data given to regulators, your organization’s crisis communications team can sit down and anticipate the top crisis scenarios that might confront your company. After all, Wal-Mart, for example, surely could have anticipated potential FCPA investigations and media interest. They operate in 28 countries on five continents: Issues involving potential bribery in one of those countries is clearly within Wal-Mart’s risk profile.

Technology can play a role here as well. Effective crisis communications software, which can bring the crisis team together virtually and provide tools and a collaborative platform for effective crisis response, can host a range of templates, talking points, employee emails, and other messages for your Chief Crisis Officer to use as a starting point for a range of crisis situations, everything from anonymous social media posts disparaging a product, to investigations and litigation or the sudden death of a key employee (the software my company created, in fact, even has a catalog of Tweets that can be employed in various scenarios when a crisis breaks.) The point is: A basic template that contains sample language and messaging serves as a starting point for the crisis communications team and will lead to the creation of better public messages (even if, in many cases, the final statement issued barely resembles the initial template).

We took a brief look at a “Sample Media ‘Holding’ Statement” in Chapter 3, as part of the Crisis Flash Sheet we created in our crisis communications plan. A more detailed template for a crisis scenario might look like this:

Accident: Facility Fire (Detailed)15

STATEMENT OF [Spokesperson]

[Company]

[LOCATION] (DATE)—On [DATE], at approximately [TIME], a fire was reported in [location of facility and area of fire]. Our personnel promptly notified [AUTHORITIES], while other employees [STEPS TAKEN, IF ANY, TO CONTROL FIRE IN INITIAL STAGES].

Fire crews arrived at approximately [TIME]. The fire was contained and controlled by [TIME].

[DESCRIBE INJURIES AND/OR PROPERTY DAMAGE AND EVACUATION MEASURES]. Local authorities tested [ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES, IF ANY, THAT HAVE BEEN DISCOVERED].

The cause of the fire is under investigation and is not yet known [ALTERNATE: DESCRIBE WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE CAUSE].

We want to assure everyone in our local community that our company takes this incident, and all issues related to fire safety, very seriously. We work closely with fire officials and other authorities to provide the most effective fire response system possible. Our facility is regularly inspected by authorities, and we quickly responds to recommended corrective measures. We also engage in regular fire prevention training and inspect our facilities on an ongoing basis and implement corrective measures resulting from those inspections [CONFIRM ACCURACY].

We want to thank local fire crews and officials and [OTHER OFFICIALS] for their quick response and hard work. We will continue to take every possible measure to ensure that incidents of this type are infrequent, and handled with the highest level of professionalism when they do occur.

![]()

This is a basic “core” message that we will use to communicate to various audiences about this particular crisis, containing the necessary information, using a heartfelt tone, and short on legalese or jargon. Moreover, the message above can be adapted below as talking points for those communicating via telephone or in person to key stakeholders:

TALKING POINTS16

- At approximately [TIME], a fire was reported in [location of facility and area of fire]. Our personnel promptly notified [AUTHORITIES], while other employees [STEPS TAKEN, IF ANY, TO CONTROL FIRE IN INITIAL STAGES].

- Fire crews arrived at approximately [TIME]. The fire was contained and controlled by [TIME]. [DESCRIBE INJURIES AND/OR PROPERTY DAMAGE AND EVACUATION MEASURES]. The cause of the fire is under investigation and is not yet known [ALTERNATE: DESCRIBE WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE CAUSE].

- We want to thank local fire crews and officials and [OTHER OFFICIALS] for their quick response and hard work. We want to assure everyone in our local community that our company takes this incident, and all issues related to fire safety, very seriously. We will continue to take every possible measure to ensure that incidents of this type are infrequent, and handled with the highest level of professionalism when they do occur.

MESSAGE TO EMPLOYEES

This text can also be adapted as a message to employees:

To [COMPANY] Employees,

At approximately [TIME], a fire was reported in [location of facility and area of fire]. Our personnel promptly notified [AUTHORITIES], while other employees [STEPS TAKEN, IF ANY, TO CONTROL FIRE IN INITIAL STAGES].

Fire crews arrived at approximately [TIME]. The fire was contained and controlled by [TIME]. The cause of the fire is under investigation and is not yet known [ALTERNATE: DESCRIBE WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE CAUSE].

We have assured the community, and want to assure you, that our company takes this incident, and all issues related to fire safety, very seriously. We work closely with fire officials and other authorities to provide the most effective fire response system possible.

As many of you know, our facility is regularly inspected by authorities, and we quickly respond to recommended corrective measures. We will continue to take every possible measure to ensure that incidents of this type are infrequent, and handled with the highest level of professionalism when they do occur.

It is critically important to remember that if you are contacted by media or any other outside parties to discuss this incident, you refer such inquiries to [CRISIS RESPONSE CONTACT]. If you have any questions, please contact [EMPLOYEE CONTACT].17

TWITTER TEMPLATE

This information can even be given in a Tweet, linking to a more detailed statement:

There is a fire at #[COMPANY HASHTAG] facility at [LOCATION]. Fire crews are on the scene. More information: [LINK TO STATEMENT ON WEBSITE OR FACEBOOK].18

![]()

You get the point. The immediacy of crisis communications response means we don’t have much time to compose messages after the crisis has begun. If you already have detailed templates, you are more prepared to deliver messages during a crisis that—while perhaps not Churchillian in their effect—fulfill their mission to help stop the crisis from spinning out of control.

Action Points

- Companies facing a crisis too often focus on the tool of message delivery—social media, YouTube videos, advertisements, or media appearances—and too little on the messages an organization is trying to convey to its stakeholders and other key target audiences.

- Complexity is often the greatest impediment to effective messaging. Since we are all experts, we create messages with the assumption that our audience will be experts too.

- Modern communications technology have created a world where messages are commoditized. For some of history’s greatest communicators—Roosevelt, Reagan, Churchill—messages were to be labored over. They worked hard, and the results showed.

- Give the immediacy of modern crisis communications, creating messages that resonate after a negative event has occurred is nearly impossible. The pitfalls encountered by such “name-brand” companies as BP, Target, Volkswagen, and Wal-Mart have shown this, which is why organizations must create effective messages for a range of potential crisis scenarios as part of their overall crisis communications effort.